User login

Antimicrobial resistance linked to 1.2 million global deaths in 2019

More than HIV, more than malaria.

In terms of preventable deaths, 1.27 million people could have been saved if drug-resistant infections were replaced with infections susceptible to current antibiotics. Furthermore, 4.95 million fewer people would have died if drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infections, researchers estimated.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took some focus off the AMR burden worldwide over the past 2 years, the urgency to address risk to public health did not ebb. In fact, based on the findings, the researchers noted that AMR is now a leading cause of death worldwide.

“If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today,” the researchers noted in the study, published online Jan. 20, 2022, in The Lancet.

“These findings are a warning signal that antibiotic resistance is placing pressure on health care systems and leading to significant health loss,” study author Kevin Ikuta, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We need to continue to adhere to and support infection prevention and control programs, be thoughtful about our antibiotic use, and advocate for increased funding to vaccine discovery and the antibiotic development pipeline,” added Dr. Ikuta, health sciences assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

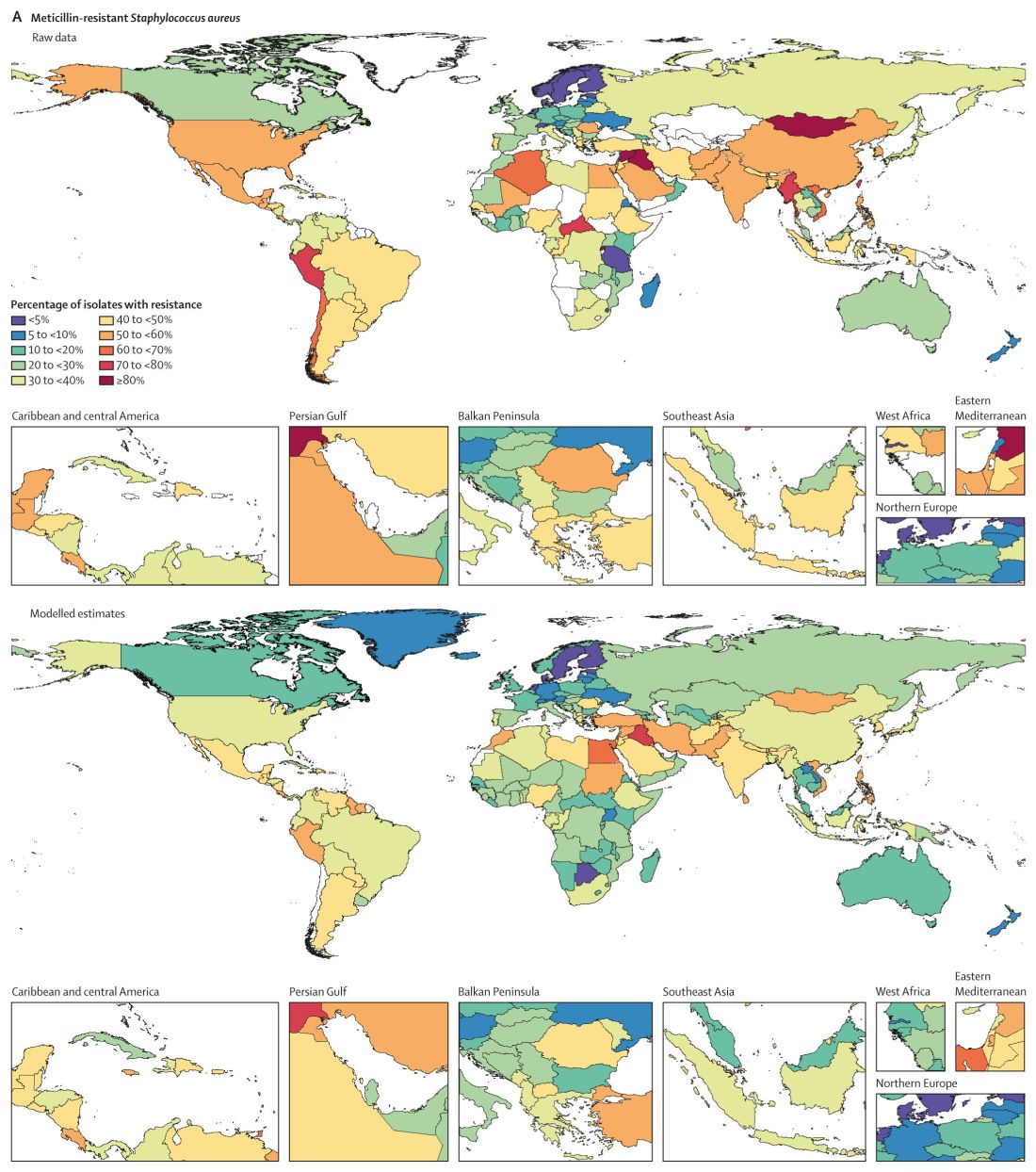

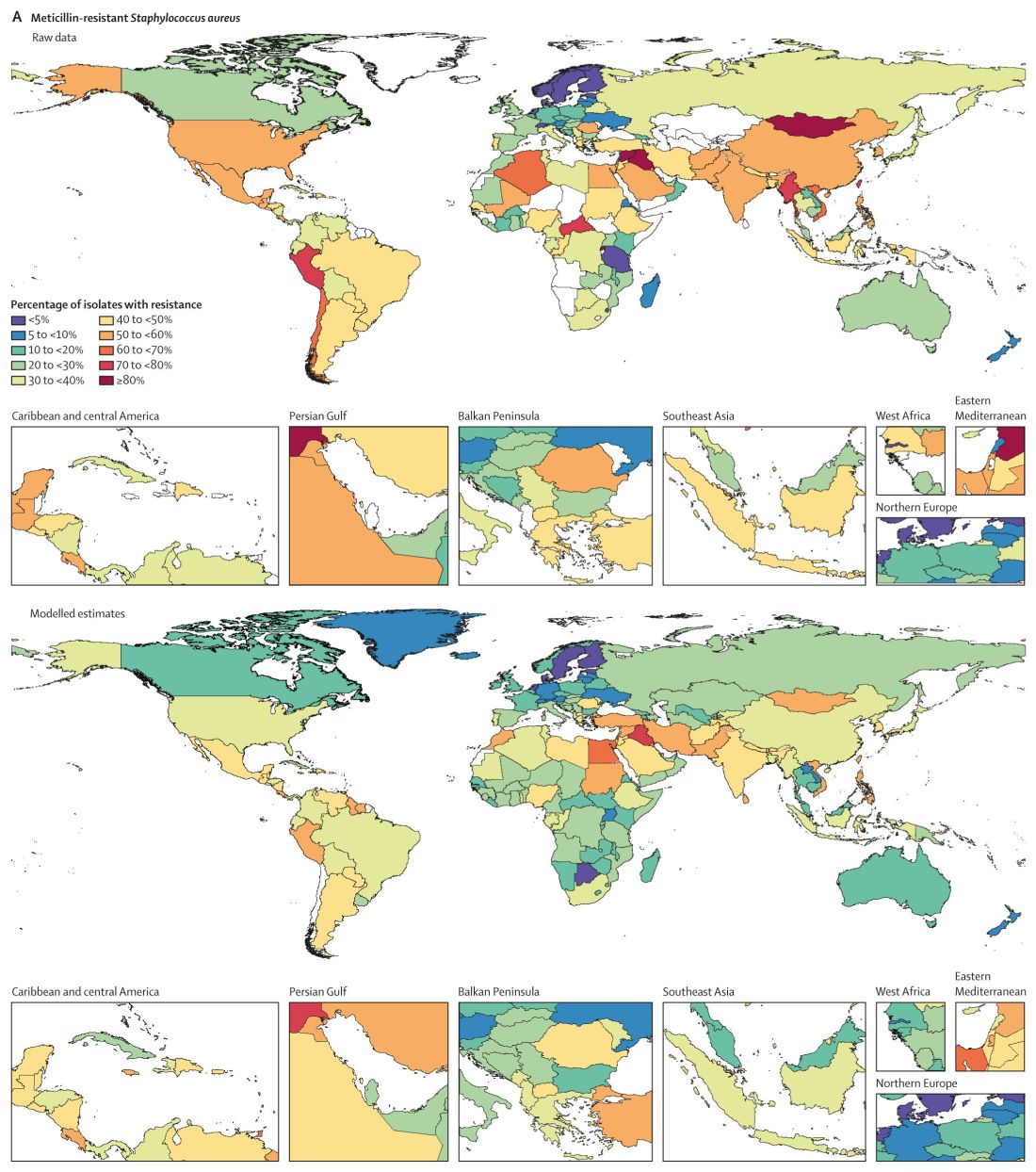

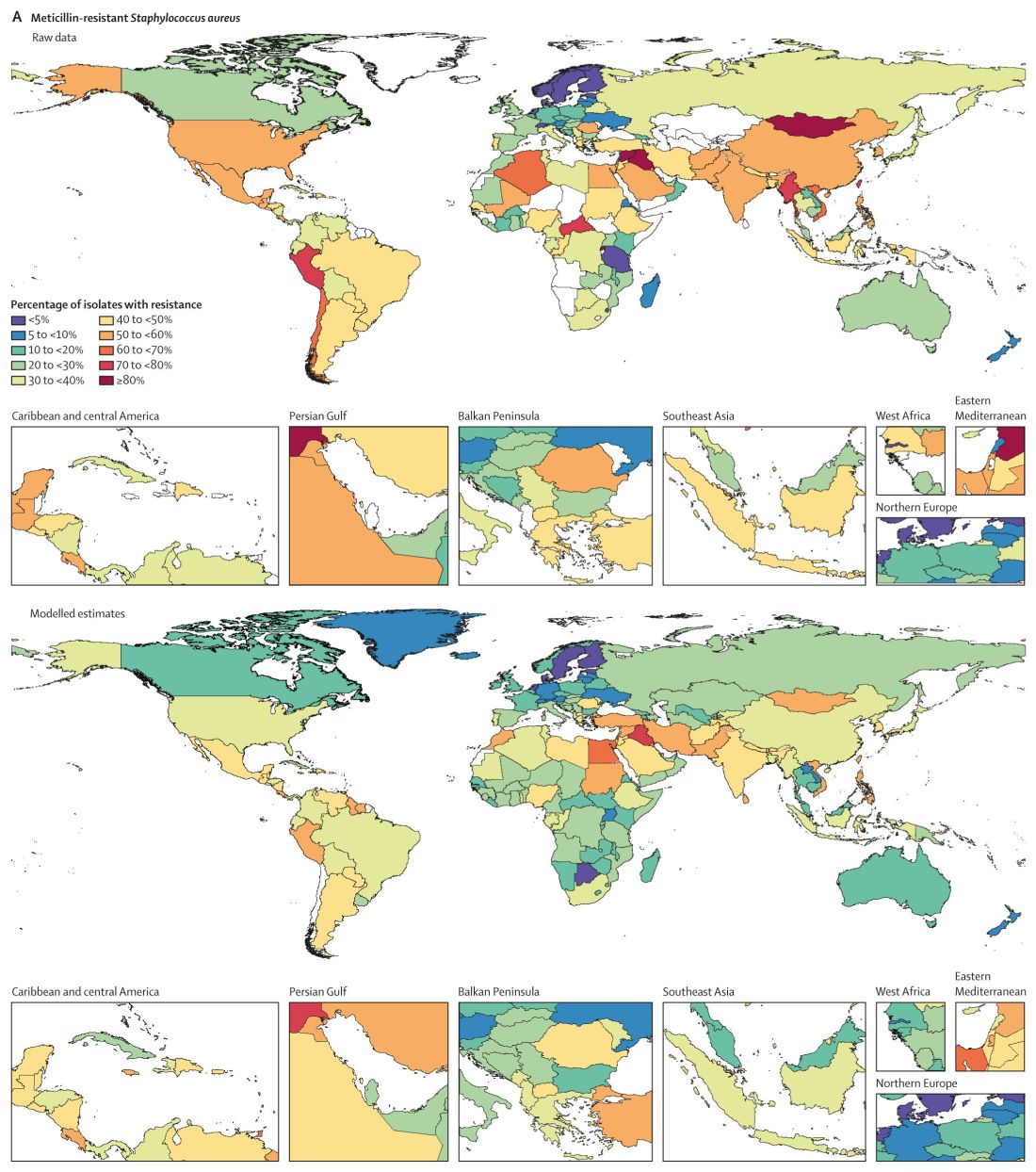

Although many investigators have studied AMR, this study is the largest in scope, covering 204 countries and territories and incorporating data on a comprehensive range of pathogens and pathogen-drug combinations.

Dr. Ikuta, lead author Christopher J.L. Murray, DPhil, and colleagues estimated the global burden of AMR using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019. They specifically looked at rates of death directly attributed to and separately those associated with resistance.

Regional differences

Broken down by 21 regions, Australasia had 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people attributable to AMR, the lowest rate reported. This region also had 28 deaths per 100,000 associated with AMR.

Researchers found the highest rates in western sub-Saharan Africa. Deaths attributable to AMR were 27.3 per 100,000 and associated death rate was 114.8 per 100,000.

Lower- and middle-income regions had the highest AMR death rates, although resistance remains a high-priority issue for high-income countries as well.

“It’s important to take a global perspective on resistant infections because we can learn about regions and countries that are experiencing the greatest burden, information that was previously unknown,” Dr. Ikuta said. “With these estimates policy makers can prioritize regions that are hotspots and would most benefit from additional interventions.”

Furthermore, the study emphasized the global nature of AMR. “We’ve seen over the last 2 years with COVID-19 that this sort of problem doesn’t respect country borders, and high rates of resistance in one location can spread across a region or spread globally pretty quickly,” Dr. Ikuta said.

Leading resistant infections

Lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections together accounted for almost 79% of such deaths linked to AMR.

The six leading pathogens are likely household names among infectious disease specialists. The researchers found Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, each responsible for more than 250,000 AMR-associated deaths.

The study also revealed that resistance to several first-line antibiotic agents often used empirically to treat infections accounted for more than 70% of the AMR-attributable deaths. These included fluoroquinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, cephalosporins, and penicillins.

Consistent with previous studies, MRSA stood out as a major cause of mortality. Of 88 different pathogen-drug combinations evaluated, MRSA was responsible for the most mortality: more than 100,000 deaths and 3·5 million disability-adjusted life-years.

The current study findings on MRSA “being a particularly nasty culprit” in AMR infections validates previous work that reported similar results, Vance Fowler, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment on the research. “That is reassuring.”

Potential solutions offered

Dr. Murray and colleagues outlined five strategies to address the challenge of bacterial AMR:

- Infection prevention and control remain paramount in minimizing infections in general and AMR infections in particular.

- More vaccines are needed to reduce the need for antibiotics. “Vaccines are available for only one of the six leading pathogens (S. pneumoniae), although new vaccine programs are underway for S. aureus, E. coli, and others,” the researchers wrote.

- Reduce antibiotic use unrelated to treatment of human disease.

- Avoid using antibiotics for viral infections and other unnecessary indications.

- Invest in new antibiotic development and ensure access to second-line agents in areas without widespread access.

“Identifying strategies that can work to reduce the burden of bacterial AMR – either across a wide range of settings or those that are specifically tailored to the resources available and leading pathogen-drug combinations in a particular setting – is an urgent priority,” the researchers noted.

Admirable AMR research

The results of the study are “startling, but not surprising,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The authors did a “nice job” of addressing both deaths attributable and associated with AMR, Dr. Fowler added. “Those two categories unlock applications, not just in terms of how you interpret it but also what you do about it.”

The deaths attributable to AMR show that there is more work to be done regarding infection control and prevention, Dr. Fowler said, including in areas of the world like lower- and middle-income countries where infection resistance is most pronounced.

The deaths associated with AMR can be more challenging to calculate – people with infections can die for multiple reasons. However, Dr. Fowler applauded the researchers for doing “as good a job as you can” in estimating the extent of associated mortality.

‘The overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance’

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Ramanan Laxminarayan, PhD, MPH, wrote: “As COVID-19 rages on, the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance continues in the shadows. The toll taken by AMR on patients and their families is largely invisible but is reflected in prolonged bacterial infections that extend hospital stays and cause needless deaths.”

Dr. Laxminarayan pointed out an irony with AMR in different regions. Some of the AMR burden in sub-Saharan Africa is “probably due to inadequate access to antibiotics and high infection levels, albeit at low levels of resistance, whereas in south Asia and Latin America, it is because of high resistance even with good access to antibiotics.”

More funding to address AMR is needed, Dr. Laxminarayan noted. “Even the lower end of 911,000 deaths estimated by Murray and colleagues is higher than the number of deaths from HIV, which attracts close to U.S. $50 billion each year. However, global spending on addressing AMR is probably much lower than that.” Dr. Laxminarayan is an economist and epidemiologist affiliated with the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, D.C., and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership in Geneva.

An overlap with COVID-19

The Lancet report is likely “to bring more attention to AMR, especially since so many people have been distracted by COVID, and rightly so,” Dr. Fowler predicted. “The world has had its hands full with COVID.”

The two infections interact in direct ways, Dr. Fowler added. For example, some people hospitalized for COVID-19 for an extended time could develop progressively drug-resistant bacteria – leading to a superinfection.

The overlap could be illustrated by a Venn diagram, he said. A yellow circle could illustrate people with COVID-19 who are asymptomatic or who remain outpatients. Next to that would be a blue circle showing people who develop AMR infections. Where the two circles overlap would be green for those hospitalized who – because of receiving steroids, being on a ventilator, or getting a central line – develop a superinfection.

Official guidance continues

The study comes in the context of recent guidance and federal action on AMR. For example, the Infectious Diseases Society of America released new guidelines for AMR in November 2021 as part of ongoing advice on prevention and treatment of this “ongoing crisis.”

This most recent IDSA guidance addresses three pathogens in particular: AmpC beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Also in November, the World Health Organization released an updated fact sheet on antimicrobial resistance. The WHO declared AMR one of the world’s top 10 global public health threats. The agency emphasized that misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens. The WHO also pointed out that lack of clean water and sanitation in many areas of the world contribute to spread of microbes, including those resistant to current treatment options.

In September 2021, the Biden administration acknowledged the threat of AMR with allocation of more than $2 billion of the American Rescue Plan money for prevention and treatment of these infections.

Asked if there are any reasons for hope or optimism at this point, Dr. Ikuta said: “Definitely. We know what needs to be done to combat the spread of resistance. COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of global commitment to infection control measures, such as hand washing and surveillance, and rapid investments in treatments, which can all be applied to antimicrobial resistance.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care using U.K. aid funding managed by the Fleming Fund and other organizations provided funding for the study. Dr. Ikuta and Dr. Laxminarayan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fowler reported receiving grants or honoraria, as well as serving as a consultant, for numerous sources. He also reported a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics and serving as chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than HIV, more than malaria.

In terms of preventable deaths, 1.27 million people could have been saved if drug-resistant infections were replaced with infections susceptible to current antibiotics. Furthermore, 4.95 million fewer people would have died if drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infections, researchers estimated.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took some focus off the AMR burden worldwide over the past 2 years, the urgency to address risk to public health did not ebb. In fact, based on the findings, the researchers noted that AMR is now a leading cause of death worldwide.

“If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today,” the researchers noted in the study, published online Jan. 20, 2022, in The Lancet.

“These findings are a warning signal that antibiotic resistance is placing pressure on health care systems and leading to significant health loss,” study author Kevin Ikuta, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We need to continue to adhere to and support infection prevention and control programs, be thoughtful about our antibiotic use, and advocate for increased funding to vaccine discovery and the antibiotic development pipeline,” added Dr. Ikuta, health sciences assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Although many investigators have studied AMR, this study is the largest in scope, covering 204 countries and territories and incorporating data on a comprehensive range of pathogens and pathogen-drug combinations.

Dr. Ikuta, lead author Christopher J.L. Murray, DPhil, and colleagues estimated the global burden of AMR using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019. They specifically looked at rates of death directly attributed to and separately those associated with resistance.

Regional differences

Broken down by 21 regions, Australasia had 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people attributable to AMR, the lowest rate reported. This region also had 28 deaths per 100,000 associated with AMR.

Researchers found the highest rates in western sub-Saharan Africa. Deaths attributable to AMR were 27.3 per 100,000 and associated death rate was 114.8 per 100,000.

Lower- and middle-income regions had the highest AMR death rates, although resistance remains a high-priority issue for high-income countries as well.

“It’s important to take a global perspective on resistant infections because we can learn about regions and countries that are experiencing the greatest burden, information that was previously unknown,” Dr. Ikuta said. “With these estimates policy makers can prioritize regions that are hotspots and would most benefit from additional interventions.”

Furthermore, the study emphasized the global nature of AMR. “We’ve seen over the last 2 years with COVID-19 that this sort of problem doesn’t respect country borders, and high rates of resistance in one location can spread across a region or spread globally pretty quickly,” Dr. Ikuta said.

Leading resistant infections

Lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections together accounted for almost 79% of such deaths linked to AMR.

The six leading pathogens are likely household names among infectious disease specialists. The researchers found Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, each responsible for more than 250,000 AMR-associated deaths.

The study also revealed that resistance to several first-line antibiotic agents often used empirically to treat infections accounted for more than 70% of the AMR-attributable deaths. These included fluoroquinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, cephalosporins, and penicillins.

Consistent with previous studies, MRSA stood out as a major cause of mortality. Of 88 different pathogen-drug combinations evaluated, MRSA was responsible for the most mortality: more than 100,000 deaths and 3·5 million disability-adjusted life-years.

The current study findings on MRSA “being a particularly nasty culprit” in AMR infections validates previous work that reported similar results, Vance Fowler, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment on the research. “That is reassuring.”

Potential solutions offered

Dr. Murray and colleagues outlined five strategies to address the challenge of bacterial AMR:

- Infection prevention and control remain paramount in minimizing infections in general and AMR infections in particular.

- More vaccines are needed to reduce the need for antibiotics. “Vaccines are available for only one of the six leading pathogens (S. pneumoniae), although new vaccine programs are underway for S. aureus, E. coli, and others,” the researchers wrote.

- Reduce antibiotic use unrelated to treatment of human disease.

- Avoid using antibiotics for viral infections and other unnecessary indications.

- Invest in new antibiotic development and ensure access to second-line agents in areas without widespread access.

“Identifying strategies that can work to reduce the burden of bacterial AMR – either across a wide range of settings or those that are specifically tailored to the resources available and leading pathogen-drug combinations in a particular setting – is an urgent priority,” the researchers noted.

Admirable AMR research

The results of the study are “startling, but not surprising,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The authors did a “nice job” of addressing both deaths attributable and associated with AMR, Dr. Fowler added. “Those two categories unlock applications, not just in terms of how you interpret it but also what you do about it.”

The deaths attributable to AMR show that there is more work to be done regarding infection control and prevention, Dr. Fowler said, including in areas of the world like lower- and middle-income countries where infection resistance is most pronounced.

The deaths associated with AMR can be more challenging to calculate – people with infections can die for multiple reasons. However, Dr. Fowler applauded the researchers for doing “as good a job as you can” in estimating the extent of associated mortality.

‘The overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance’

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Ramanan Laxminarayan, PhD, MPH, wrote: “As COVID-19 rages on, the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance continues in the shadows. The toll taken by AMR on patients and their families is largely invisible but is reflected in prolonged bacterial infections that extend hospital stays and cause needless deaths.”

Dr. Laxminarayan pointed out an irony with AMR in different regions. Some of the AMR burden in sub-Saharan Africa is “probably due to inadequate access to antibiotics and high infection levels, albeit at low levels of resistance, whereas in south Asia and Latin America, it is because of high resistance even with good access to antibiotics.”

More funding to address AMR is needed, Dr. Laxminarayan noted. “Even the lower end of 911,000 deaths estimated by Murray and colleagues is higher than the number of deaths from HIV, which attracts close to U.S. $50 billion each year. However, global spending on addressing AMR is probably much lower than that.” Dr. Laxminarayan is an economist and epidemiologist affiliated with the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, D.C., and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership in Geneva.

An overlap with COVID-19

The Lancet report is likely “to bring more attention to AMR, especially since so many people have been distracted by COVID, and rightly so,” Dr. Fowler predicted. “The world has had its hands full with COVID.”

The two infections interact in direct ways, Dr. Fowler added. For example, some people hospitalized for COVID-19 for an extended time could develop progressively drug-resistant bacteria – leading to a superinfection.

The overlap could be illustrated by a Venn diagram, he said. A yellow circle could illustrate people with COVID-19 who are asymptomatic or who remain outpatients. Next to that would be a blue circle showing people who develop AMR infections. Where the two circles overlap would be green for those hospitalized who – because of receiving steroids, being on a ventilator, or getting a central line – develop a superinfection.

Official guidance continues

The study comes in the context of recent guidance and federal action on AMR. For example, the Infectious Diseases Society of America released new guidelines for AMR in November 2021 as part of ongoing advice on prevention and treatment of this “ongoing crisis.”

This most recent IDSA guidance addresses three pathogens in particular: AmpC beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Also in November, the World Health Organization released an updated fact sheet on antimicrobial resistance. The WHO declared AMR one of the world’s top 10 global public health threats. The agency emphasized that misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens. The WHO also pointed out that lack of clean water and sanitation in many areas of the world contribute to spread of microbes, including those resistant to current treatment options.

In September 2021, the Biden administration acknowledged the threat of AMR with allocation of more than $2 billion of the American Rescue Plan money for prevention and treatment of these infections.

Asked if there are any reasons for hope or optimism at this point, Dr. Ikuta said: “Definitely. We know what needs to be done to combat the spread of resistance. COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of global commitment to infection control measures, such as hand washing and surveillance, and rapid investments in treatments, which can all be applied to antimicrobial resistance.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care using U.K. aid funding managed by the Fleming Fund and other organizations provided funding for the study. Dr. Ikuta and Dr. Laxminarayan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fowler reported receiving grants or honoraria, as well as serving as a consultant, for numerous sources. He also reported a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics and serving as chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than HIV, more than malaria.

In terms of preventable deaths, 1.27 million people could have been saved if drug-resistant infections were replaced with infections susceptible to current antibiotics. Furthermore, 4.95 million fewer people would have died if drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infections, researchers estimated.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took some focus off the AMR burden worldwide over the past 2 years, the urgency to address risk to public health did not ebb. In fact, based on the findings, the researchers noted that AMR is now a leading cause of death worldwide.

“If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today,” the researchers noted in the study, published online Jan. 20, 2022, in The Lancet.

“These findings are a warning signal that antibiotic resistance is placing pressure on health care systems and leading to significant health loss,” study author Kevin Ikuta, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We need to continue to adhere to and support infection prevention and control programs, be thoughtful about our antibiotic use, and advocate for increased funding to vaccine discovery and the antibiotic development pipeline,” added Dr. Ikuta, health sciences assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Although many investigators have studied AMR, this study is the largest in scope, covering 204 countries and territories and incorporating data on a comprehensive range of pathogens and pathogen-drug combinations.

Dr. Ikuta, lead author Christopher J.L. Murray, DPhil, and colleagues estimated the global burden of AMR using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019. They specifically looked at rates of death directly attributed to and separately those associated with resistance.

Regional differences

Broken down by 21 regions, Australasia had 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people attributable to AMR, the lowest rate reported. This region also had 28 deaths per 100,000 associated with AMR.

Researchers found the highest rates in western sub-Saharan Africa. Deaths attributable to AMR were 27.3 per 100,000 and associated death rate was 114.8 per 100,000.

Lower- and middle-income regions had the highest AMR death rates, although resistance remains a high-priority issue for high-income countries as well.

“It’s important to take a global perspective on resistant infections because we can learn about regions and countries that are experiencing the greatest burden, information that was previously unknown,” Dr. Ikuta said. “With these estimates policy makers can prioritize regions that are hotspots and would most benefit from additional interventions.”

Furthermore, the study emphasized the global nature of AMR. “We’ve seen over the last 2 years with COVID-19 that this sort of problem doesn’t respect country borders, and high rates of resistance in one location can spread across a region or spread globally pretty quickly,” Dr. Ikuta said.

Leading resistant infections

Lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections together accounted for almost 79% of such deaths linked to AMR.

The six leading pathogens are likely household names among infectious disease specialists. The researchers found Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, each responsible for more than 250,000 AMR-associated deaths.

The study also revealed that resistance to several first-line antibiotic agents often used empirically to treat infections accounted for more than 70% of the AMR-attributable deaths. These included fluoroquinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, cephalosporins, and penicillins.

Consistent with previous studies, MRSA stood out as a major cause of mortality. Of 88 different pathogen-drug combinations evaluated, MRSA was responsible for the most mortality: more than 100,000 deaths and 3·5 million disability-adjusted life-years.

The current study findings on MRSA “being a particularly nasty culprit” in AMR infections validates previous work that reported similar results, Vance Fowler, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment on the research. “That is reassuring.”

Potential solutions offered

Dr. Murray and colleagues outlined five strategies to address the challenge of bacterial AMR:

- Infection prevention and control remain paramount in minimizing infections in general and AMR infections in particular.

- More vaccines are needed to reduce the need for antibiotics. “Vaccines are available for only one of the six leading pathogens (S. pneumoniae), although new vaccine programs are underway for S. aureus, E. coli, and others,” the researchers wrote.

- Reduce antibiotic use unrelated to treatment of human disease.

- Avoid using antibiotics for viral infections and other unnecessary indications.

- Invest in new antibiotic development and ensure access to second-line agents in areas without widespread access.

“Identifying strategies that can work to reduce the burden of bacterial AMR – either across a wide range of settings or those that are specifically tailored to the resources available and leading pathogen-drug combinations in a particular setting – is an urgent priority,” the researchers noted.

Admirable AMR research

The results of the study are “startling, but not surprising,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The authors did a “nice job” of addressing both deaths attributable and associated with AMR, Dr. Fowler added. “Those two categories unlock applications, not just in terms of how you interpret it but also what you do about it.”

The deaths attributable to AMR show that there is more work to be done regarding infection control and prevention, Dr. Fowler said, including in areas of the world like lower- and middle-income countries where infection resistance is most pronounced.

The deaths associated with AMR can be more challenging to calculate – people with infections can die for multiple reasons. However, Dr. Fowler applauded the researchers for doing “as good a job as you can” in estimating the extent of associated mortality.

‘The overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance’

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Ramanan Laxminarayan, PhD, MPH, wrote: “As COVID-19 rages on, the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance continues in the shadows. The toll taken by AMR on patients and their families is largely invisible but is reflected in prolonged bacterial infections that extend hospital stays and cause needless deaths.”

Dr. Laxminarayan pointed out an irony with AMR in different regions. Some of the AMR burden in sub-Saharan Africa is “probably due to inadequate access to antibiotics and high infection levels, albeit at low levels of resistance, whereas in south Asia and Latin America, it is because of high resistance even with good access to antibiotics.”

More funding to address AMR is needed, Dr. Laxminarayan noted. “Even the lower end of 911,000 deaths estimated by Murray and colleagues is higher than the number of deaths from HIV, which attracts close to U.S. $50 billion each year. However, global spending on addressing AMR is probably much lower than that.” Dr. Laxminarayan is an economist and epidemiologist affiliated with the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, D.C., and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership in Geneva.

An overlap with COVID-19

The Lancet report is likely “to bring more attention to AMR, especially since so many people have been distracted by COVID, and rightly so,” Dr. Fowler predicted. “The world has had its hands full with COVID.”

The two infections interact in direct ways, Dr. Fowler added. For example, some people hospitalized for COVID-19 for an extended time could develop progressively drug-resistant bacteria – leading to a superinfection.

The overlap could be illustrated by a Venn diagram, he said. A yellow circle could illustrate people with COVID-19 who are asymptomatic or who remain outpatients. Next to that would be a blue circle showing people who develop AMR infections. Where the two circles overlap would be green for those hospitalized who – because of receiving steroids, being on a ventilator, or getting a central line – develop a superinfection.

Official guidance continues

The study comes in the context of recent guidance and federal action on AMR. For example, the Infectious Diseases Society of America released new guidelines for AMR in November 2021 as part of ongoing advice on prevention and treatment of this “ongoing crisis.”

This most recent IDSA guidance addresses three pathogens in particular: AmpC beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Also in November, the World Health Organization released an updated fact sheet on antimicrobial resistance. The WHO declared AMR one of the world’s top 10 global public health threats. The agency emphasized that misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens. The WHO also pointed out that lack of clean water and sanitation in many areas of the world contribute to spread of microbes, including those resistant to current treatment options.

In September 2021, the Biden administration acknowledged the threat of AMR with allocation of more than $2 billion of the American Rescue Plan money for prevention and treatment of these infections.

Asked if there are any reasons for hope or optimism at this point, Dr. Ikuta said: “Definitely. We know what needs to be done to combat the spread of resistance. COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of global commitment to infection control measures, such as hand washing and surveillance, and rapid investments in treatments, which can all be applied to antimicrobial resistance.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care using U.K. aid funding managed by the Fleming Fund and other organizations provided funding for the study. Dr. Ikuta and Dr. Laxminarayan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fowler reported receiving grants or honoraria, as well as serving as a consultant, for numerous sources. He also reported a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics and serving as chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antibiotic choices for inpatients with SSTIs vary by race

– in a national cross-sectional study involving over 1,000 patients in 91 hospitals.

The potential racial disparity in management of SSTI was detected after data were adjusted for penicillin allergy history and for MRSA colonization/infection. The data were also adjusted for hospital day (since admission) in order to control for the administration of more empiric therapy early on.

Clindamycin, a beta-lactam alternative, is not recommended as an SSTI treatment given its frequent dosing requirements and high potential for adverse events including Clostridioides difficile infection (DCI). “Clindamycin is an option but it’s considered inferior. ... It covers MRSA but it shouldn’t be a go-to for skin and soft-tissue infections,” said senior author Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University, and an allergist, immunologist, and drug allergy and epidemiology researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Cefazolin, on the other hand, does not cover MRSA but is “a guideline-recommended first-line antibiotic for cellulitis SSTI in the hospital,” she said in an interview.

The findings, recently published in JAMA Network Open, offer a valuable portrait of the antibiotics being prescribed in the inpatient setting for SSTIs. Vancomycin, which typically is reserved for MRSA, was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic, regardless of race. Piperacillin-tazobactam, a beta-lactam, was the second most commonly prescribed antibiotic, again regardless of race.

Intravenously administered cefazolin was used in 13% of White inpatients versus 5% of Black inpatients. After controlling for kidney disease, diabetes, and ICU location (in addition to hospital day, penicillin allergy history, and MRSA), White inpatients had an increased likelihood of being prescribed cefazolin (adjusted odds ratio, 2.82; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-5.63) and a decreased likelihood of clindamycin use (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.96), compared with Black inpatients.

The investigators utilized the Acute Care Hospital Groups network within Vizient, a member-driven health care performance improvement company, to collect data for the study. Most of the hospitals (91%) that submitted data on adult inpatients with cellulitis or SSTIs (without other infections) were in urban settings and 9% were in rural settings; 60% were community hospitals and 40% were academic medical centers. The researchers accounted for “clustering by hospital” – such as the use of internal guidelines – in their methodology.

Differential management and prescribing practices associated with race and ethnicity have been demonstrated for cardiovascular disease and other chronic problems, but “to see such racial differences play out in acute care is striking,” Utibe R. Essien, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and a core investigator with the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, said in an interview.

“In acute care, we tend to practice pretty similarly across the board ... so the findings give me pause,” said Dr. Essien, an internist and a coauthor of the study, who also works with the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing.

Also notable was the prevalence of historical penicillin allergy documented in the dataset: 23% in Black inpatients and 18% in White inpatients with SSTI. It’s a surprisingly high prevalence overall, Dr. Blumenthal said, and the racial difference was surprising because penicillin allergy has been commonly described in the literature as being more common in the White population.

Even though penicillin allergy was controlled for in the study, “given that historical penicillin allergies are associated with increased clindamycin use and risk of CDI, but are often disproved with formal testing, racial disparities in penicillin allergy documentation and assessment require additional study,” she and her coauthors wrote.

Ideally, Dr. Blumenthal said, all inpatients would have access to allergy consultations or testing or some sort of infrastructure for assessing a history of penicillin allergy. At Mass General, allergy consults and challenge doses of beta-lactams (also called graded challenges) are frequently employed.

The study did not collect data on income, educational level, and other structural vulnerability factors. More research is needed to better understand “what’s going on in acute care settings and what the potential drivers of disparities may be,” said Dr. Essien, who co-authored a recent JAMA editorial on “achieving pharmacoequity” to reduce health disparities.

“If guidelines suggest that medication A is the ideal and optimal treatment, we really have to do our best to ensure that every patient, regardless of race or ethnicity, can get that treatment,” he said.

In the study, race was extracted from the medical record and may not have been correctly assigned, the authors noted. “Other race” was not specified in the dataset, and Hispanic ethnicity was not captured. The number of individuals identified as Asian and other races was small, prompting the researchers to focus on antibiotic use in Black and White patients (224 and 854 patients, respectively).

Dr. Blumenthal and Dr. Essien both reported that they had no relevant disclosures. The study was supported with National Institutes of Health grants and the Massachusetts General Hospital department of medicine transformative scholar program.

– in a national cross-sectional study involving over 1,000 patients in 91 hospitals.

The potential racial disparity in management of SSTI was detected after data were adjusted for penicillin allergy history and for MRSA colonization/infection. The data were also adjusted for hospital day (since admission) in order to control for the administration of more empiric therapy early on.

Clindamycin, a beta-lactam alternative, is not recommended as an SSTI treatment given its frequent dosing requirements and high potential for adverse events including Clostridioides difficile infection (DCI). “Clindamycin is an option but it’s considered inferior. ... It covers MRSA but it shouldn’t be a go-to for skin and soft-tissue infections,” said senior author Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University, and an allergist, immunologist, and drug allergy and epidemiology researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Cefazolin, on the other hand, does not cover MRSA but is “a guideline-recommended first-line antibiotic for cellulitis SSTI in the hospital,” she said in an interview.

The findings, recently published in JAMA Network Open, offer a valuable portrait of the antibiotics being prescribed in the inpatient setting for SSTIs. Vancomycin, which typically is reserved for MRSA, was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic, regardless of race. Piperacillin-tazobactam, a beta-lactam, was the second most commonly prescribed antibiotic, again regardless of race.

Intravenously administered cefazolin was used in 13% of White inpatients versus 5% of Black inpatients. After controlling for kidney disease, diabetes, and ICU location (in addition to hospital day, penicillin allergy history, and MRSA), White inpatients had an increased likelihood of being prescribed cefazolin (adjusted odds ratio, 2.82; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-5.63) and a decreased likelihood of clindamycin use (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.96), compared with Black inpatients.

The investigators utilized the Acute Care Hospital Groups network within Vizient, a member-driven health care performance improvement company, to collect data for the study. Most of the hospitals (91%) that submitted data on adult inpatients with cellulitis or SSTIs (without other infections) were in urban settings and 9% were in rural settings; 60% were community hospitals and 40% were academic medical centers. The researchers accounted for “clustering by hospital” – such as the use of internal guidelines – in their methodology.

Differential management and prescribing practices associated with race and ethnicity have been demonstrated for cardiovascular disease and other chronic problems, but “to see such racial differences play out in acute care is striking,” Utibe R. Essien, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and a core investigator with the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, said in an interview.

“In acute care, we tend to practice pretty similarly across the board ... so the findings give me pause,” said Dr. Essien, an internist and a coauthor of the study, who also works with the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing.

Also notable was the prevalence of historical penicillin allergy documented in the dataset: 23% in Black inpatients and 18% in White inpatients with SSTI. It’s a surprisingly high prevalence overall, Dr. Blumenthal said, and the racial difference was surprising because penicillin allergy has been commonly described in the literature as being more common in the White population.

Even though penicillin allergy was controlled for in the study, “given that historical penicillin allergies are associated with increased clindamycin use and risk of CDI, but are often disproved with formal testing, racial disparities in penicillin allergy documentation and assessment require additional study,” she and her coauthors wrote.

Ideally, Dr. Blumenthal said, all inpatients would have access to allergy consultations or testing or some sort of infrastructure for assessing a history of penicillin allergy. At Mass General, allergy consults and challenge doses of beta-lactams (also called graded challenges) are frequently employed.

The study did not collect data on income, educational level, and other structural vulnerability factors. More research is needed to better understand “what’s going on in acute care settings and what the potential drivers of disparities may be,” said Dr. Essien, who co-authored a recent JAMA editorial on “achieving pharmacoequity” to reduce health disparities.

“If guidelines suggest that medication A is the ideal and optimal treatment, we really have to do our best to ensure that every patient, regardless of race or ethnicity, can get that treatment,” he said.

In the study, race was extracted from the medical record and may not have been correctly assigned, the authors noted. “Other race” was not specified in the dataset, and Hispanic ethnicity was not captured. The number of individuals identified as Asian and other races was small, prompting the researchers to focus on antibiotic use in Black and White patients (224 and 854 patients, respectively).

Dr. Blumenthal and Dr. Essien both reported that they had no relevant disclosures. The study was supported with National Institutes of Health grants and the Massachusetts General Hospital department of medicine transformative scholar program.

– in a national cross-sectional study involving over 1,000 patients in 91 hospitals.

The potential racial disparity in management of SSTI was detected after data were adjusted for penicillin allergy history and for MRSA colonization/infection. The data were also adjusted for hospital day (since admission) in order to control for the administration of more empiric therapy early on.

Clindamycin, a beta-lactam alternative, is not recommended as an SSTI treatment given its frequent dosing requirements and high potential for adverse events including Clostridioides difficile infection (DCI). “Clindamycin is an option but it’s considered inferior. ... It covers MRSA but it shouldn’t be a go-to for skin and soft-tissue infections,” said senior author Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University, and an allergist, immunologist, and drug allergy and epidemiology researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Cefazolin, on the other hand, does not cover MRSA but is “a guideline-recommended first-line antibiotic for cellulitis SSTI in the hospital,” she said in an interview.

The findings, recently published in JAMA Network Open, offer a valuable portrait of the antibiotics being prescribed in the inpatient setting for SSTIs. Vancomycin, which typically is reserved for MRSA, was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic, regardless of race. Piperacillin-tazobactam, a beta-lactam, was the second most commonly prescribed antibiotic, again regardless of race.

Intravenously administered cefazolin was used in 13% of White inpatients versus 5% of Black inpatients. After controlling for kidney disease, diabetes, and ICU location (in addition to hospital day, penicillin allergy history, and MRSA), White inpatients had an increased likelihood of being prescribed cefazolin (adjusted odds ratio, 2.82; 95% confidence interval, 1.41-5.63) and a decreased likelihood of clindamycin use (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.96), compared with Black inpatients.

The investigators utilized the Acute Care Hospital Groups network within Vizient, a member-driven health care performance improvement company, to collect data for the study. Most of the hospitals (91%) that submitted data on adult inpatients with cellulitis or SSTIs (without other infections) were in urban settings and 9% were in rural settings; 60% were community hospitals and 40% were academic medical centers. The researchers accounted for “clustering by hospital” – such as the use of internal guidelines – in their methodology.

Differential management and prescribing practices associated with race and ethnicity have been demonstrated for cardiovascular disease and other chronic problems, but “to see such racial differences play out in acute care is striking,” Utibe R. Essien, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and a core investigator with the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, said in an interview.

“In acute care, we tend to practice pretty similarly across the board ... so the findings give me pause,” said Dr. Essien, an internist and a coauthor of the study, who also works with the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing.

Also notable was the prevalence of historical penicillin allergy documented in the dataset: 23% in Black inpatients and 18% in White inpatients with SSTI. It’s a surprisingly high prevalence overall, Dr. Blumenthal said, and the racial difference was surprising because penicillin allergy has been commonly described in the literature as being more common in the White population.

Even though penicillin allergy was controlled for in the study, “given that historical penicillin allergies are associated with increased clindamycin use and risk of CDI, but are often disproved with formal testing, racial disparities in penicillin allergy documentation and assessment require additional study,” she and her coauthors wrote.

Ideally, Dr. Blumenthal said, all inpatients would have access to allergy consultations or testing or some sort of infrastructure for assessing a history of penicillin allergy. At Mass General, allergy consults and challenge doses of beta-lactams (also called graded challenges) are frequently employed.

The study did not collect data on income, educational level, and other structural vulnerability factors. More research is needed to better understand “what’s going on in acute care settings and what the potential drivers of disparities may be,” said Dr. Essien, who co-authored a recent JAMA editorial on “achieving pharmacoequity” to reduce health disparities.

“If guidelines suggest that medication A is the ideal and optimal treatment, we really have to do our best to ensure that every patient, regardless of race or ethnicity, can get that treatment,” he said.

In the study, race was extracted from the medical record and may not have been correctly assigned, the authors noted. “Other race” was not specified in the dataset, and Hispanic ethnicity was not captured. The number of individuals identified as Asian and other races was small, prompting the researchers to focus on antibiotic use in Black and White patients (224 and 854 patients, respectively).

Dr. Blumenthal and Dr. Essien both reported that they had no relevant disclosures. The study was supported with National Institutes of Health grants and the Massachusetts General Hospital department of medicine transformative scholar program.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

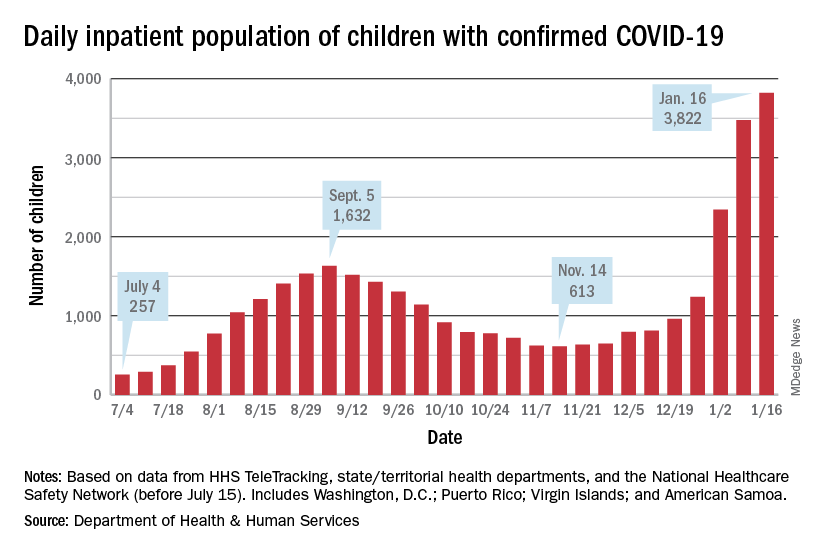

Severe outcomes increased in youth hospitalized after positive COVID-19 test

Approximately 3% of youth who tested positive for COVID-19 in an emergency department setting had severe outcomes after 2 weeks, but this risk was 0.5% among those not admitted to the hospital, based on data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 and younger.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, youth younger than 18 years accounted for fewer than 5% of reported cases, but now account for approximately 25% of positive cases, wrote Anna L. Funk, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and colleagues.

However, the risk of severe outcomes of youth with COVID-19 remains poorly understood and data from large studies are lacking, they noted.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 3,221 children and adolescents who were tested for COVID-19 at one of 41 emergency departments in 10 countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, New Zealand, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain, and the United States between March 2020 and June 2021. Positive infections were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. At 14 days’ follow-up after a positive test, 735 patients (22.8%), were hospitalized, 107 (3.3%) had severe outcomes, and 4 (0.12%) had died. Severe outcomes were significantly more likely in children aged 5-10 years and 10-18 years vs. less than 1 year (odds ratios, 1.60 and 2.39, respectively), and in children with a self-reported chronic illness (OR, 2.34) or a prior episode of pneumonia (OR, 3.15).

Severe outcomes were more likely in patients who presented with symptoms that started 4-7 days before seeking care, compared with those whose symptoms started 0-3 days before seeking care (OR, 2.22).

The researchers also reviewed data from a subgroup of 2,510 individuals who were discharged home from the ED after initial testing. At 14 days’ follow-up, 50 of these patients (2.0%) were hospitalized and 12 (0.5%) had severe outcomes. In addition, the researchers found that the risk of severe outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19–positive youth was nearly four times higher, compared with hospitalized youth who tested negative for COVID-19 (risk difference, 3.9%).

Previous retrospective studies of severe outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 have yielded varying results, in part because of the variation in study populations, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Our study population provides a risk estimate for youths brought for ED care.” Therefore, “Our lower estimate of severe disease likely reflects our stringent definition, which required the occurrence of complications or specific invasive interventions,” they said.

The study limitations included the potential overestimation of the risk of severe outcomes because patients were recruited in the ED, the researchers noted. Other limitations included variation in regional case definitions, screening criteria, and testing capacity among different sites and time periods. “Thus, 5% of our SARS-CoV-2–positive participants were asymptomatic – most of whom were tested as they were positive contacts of known cases or as part of routine screening procedures,” they said. The findings also are not generalizable to all community EDs and did not account for variants, they added.

However, the results were strengthened by the ability to compare outcomes for children with positive tests to similar children with negative tests, and add to the literature showing an increased risk of severe outcomes for those hospitalized with positive tests, the researchers concluded.

Data may inform clinical decisions

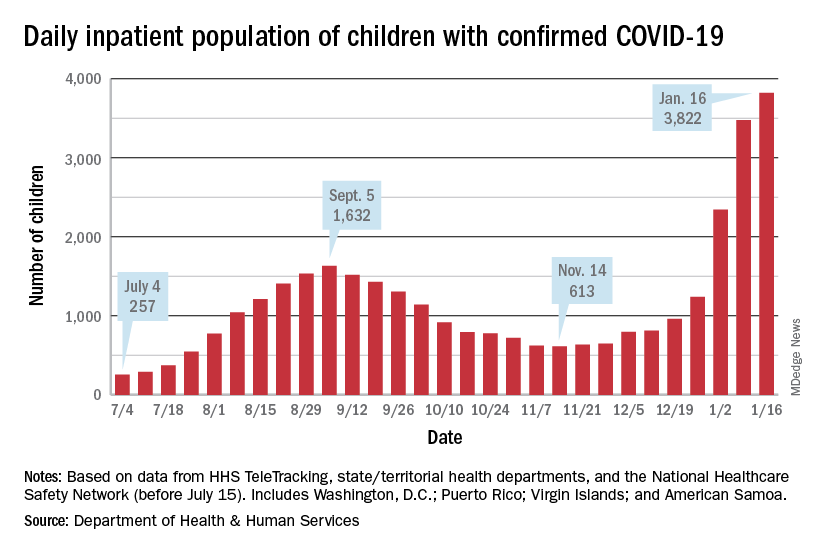

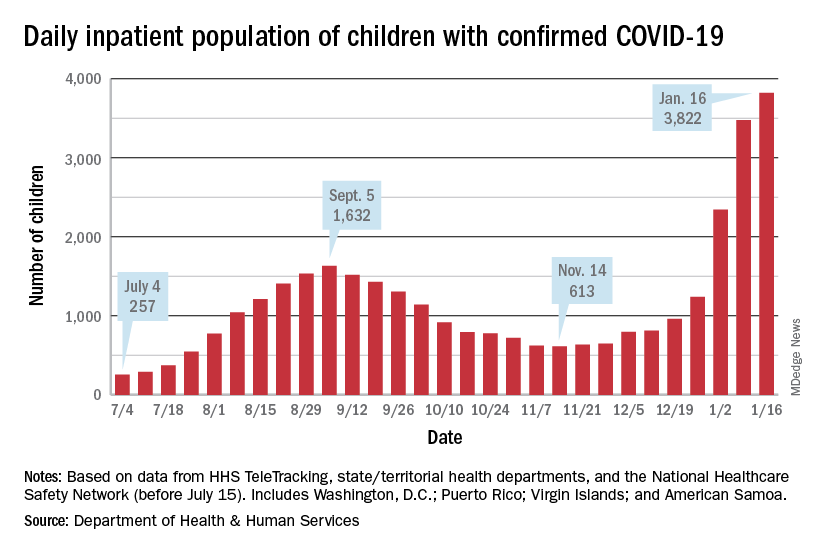

“The data [in the current study] are concerning for severe outcomes for children even prior to the Omicron strain,” said Margaret Thew, DNP, FP-BC, of Children’s Wisconsin-Milwaukee Hospital, in an interview. “Presently, the number of children infected with the Omicron strain is much higher and hospitalizations among children are at their highest since COVID-19 began,” she said. “For medical providers caring for this population, the study sheds light on pediatric patients who may be at higher risk of severe illness when they become infected with COVID-19,” she added.

“I was surprised by how high the number of pediatric patients hospitalized (22%) and the percentage (3%) with severe disease were during this time,” given that the timeline for these data preceded the spread of the Omicron strain, said Ms. Thew. “The risk of prior pneumonia was quite surprising. I do not recall seeing prior pneumonia as a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 with children or adults,” she added.

The take-home messaging for clinicians caring for children and adolescents is the added knowledge of the risk factors for severe outcomes from COVID-19, including the 10-18 age range, chronic illness, prior pneumonia, and longer symptom duration before seeking care in the ED, Ms. Thew emphasized.

However, additional research is needed on the impact of the new strains of COVID-19 on pediatric and adolescent hospitalizations, Ms. Thew said. Research also is needed on the other illnesses that have resulted from COVID-19, including illness requiring antibiotic use or medical interventions or treatments, and on the risk of combined COVID-19 and influenza viruses, she noted.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, the Alberta Health Services University of Calgary Clinical Research Fund, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the COVID-19 Research Accelerator Funding Track (CRAFT) Program at the University of California, Davis, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Division of Emergency Medicine Small Grants Program. Lead author Dr. Funk was supported by the University of Calgary Eyes-High Post-Doctoral Research Fund, but had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

Approximately 3% of youth who tested positive for COVID-19 in an emergency department setting had severe outcomes after 2 weeks, but this risk was 0.5% among those not admitted to the hospital, based on data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 and younger.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, youth younger than 18 years accounted for fewer than 5% of reported cases, but now account for approximately 25% of positive cases, wrote Anna L. Funk, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and colleagues.

However, the risk of severe outcomes of youth with COVID-19 remains poorly understood and data from large studies are lacking, they noted.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 3,221 children and adolescents who were tested for COVID-19 at one of 41 emergency departments in 10 countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, New Zealand, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain, and the United States between March 2020 and June 2021. Positive infections were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. At 14 days’ follow-up after a positive test, 735 patients (22.8%), were hospitalized, 107 (3.3%) had severe outcomes, and 4 (0.12%) had died. Severe outcomes were significantly more likely in children aged 5-10 years and 10-18 years vs. less than 1 year (odds ratios, 1.60 and 2.39, respectively), and in children with a self-reported chronic illness (OR, 2.34) or a prior episode of pneumonia (OR, 3.15).

Severe outcomes were more likely in patients who presented with symptoms that started 4-7 days before seeking care, compared with those whose symptoms started 0-3 days before seeking care (OR, 2.22).

The researchers also reviewed data from a subgroup of 2,510 individuals who were discharged home from the ED after initial testing. At 14 days’ follow-up, 50 of these patients (2.0%) were hospitalized and 12 (0.5%) had severe outcomes. In addition, the researchers found that the risk of severe outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19–positive youth was nearly four times higher, compared with hospitalized youth who tested negative for COVID-19 (risk difference, 3.9%).

Previous retrospective studies of severe outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 have yielded varying results, in part because of the variation in study populations, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Our study population provides a risk estimate for youths brought for ED care.” Therefore, “Our lower estimate of severe disease likely reflects our stringent definition, which required the occurrence of complications or specific invasive interventions,” they said.

The study limitations included the potential overestimation of the risk of severe outcomes because patients were recruited in the ED, the researchers noted. Other limitations included variation in regional case definitions, screening criteria, and testing capacity among different sites and time periods. “Thus, 5% of our SARS-CoV-2–positive participants were asymptomatic – most of whom were tested as they were positive contacts of known cases or as part of routine screening procedures,” they said. The findings also are not generalizable to all community EDs and did not account for variants, they added.

However, the results were strengthened by the ability to compare outcomes for children with positive tests to similar children with negative tests, and add to the literature showing an increased risk of severe outcomes for those hospitalized with positive tests, the researchers concluded.

Data may inform clinical decisions

“The data [in the current study] are concerning for severe outcomes for children even prior to the Omicron strain,” said Margaret Thew, DNP, FP-BC, of Children’s Wisconsin-Milwaukee Hospital, in an interview. “Presently, the number of children infected with the Omicron strain is much higher and hospitalizations among children are at their highest since COVID-19 began,” she said. “For medical providers caring for this population, the study sheds light on pediatric patients who may be at higher risk of severe illness when they become infected with COVID-19,” she added.

“I was surprised by how high the number of pediatric patients hospitalized (22%) and the percentage (3%) with severe disease were during this time,” given that the timeline for these data preceded the spread of the Omicron strain, said Ms. Thew. “The risk of prior pneumonia was quite surprising. I do not recall seeing prior pneumonia as a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 with children or adults,” she added.

The take-home messaging for clinicians caring for children and adolescents is the added knowledge of the risk factors for severe outcomes from COVID-19, including the 10-18 age range, chronic illness, prior pneumonia, and longer symptom duration before seeking care in the ED, Ms. Thew emphasized.

However, additional research is needed on the impact of the new strains of COVID-19 on pediatric and adolescent hospitalizations, Ms. Thew said. Research also is needed on the other illnesses that have resulted from COVID-19, including illness requiring antibiotic use or medical interventions or treatments, and on the risk of combined COVID-19 and influenza viruses, she noted.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, the Alberta Health Services University of Calgary Clinical Research Fund, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the COVID-19 Research Accelerator Funding Track (CRAFT) Program at the University of California, Davis, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Division of Emergency Medicine Small Grants Program. Lead author Dr. Funk was supported by the University of Calgary Eyes-High Post-Doctoral Research Fund, but had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

Approximately 3% of youth who tested positive for COVID-19 in an emergency department setting had severe outcomes after 2 weeks, but this risk was 0.5% among those not admitted to the hospital, based on data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 and younger.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, youth younger than 18 years accounted for fewer than 5% of reported cases, but now account for approximately 25% of positive cases, wrote Anna L. Funk, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and colleagues.

However, the risk of severe outcomes of youth with COVID-19 remains poorly understood and data from large studies are lacking, they noted.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 3,221 children and adolescents who were tested for COVID-19 at one of 41 emergency departments in 10 countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, New Zealand, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain, and the United States between March 2020 and June 2021. Positive infections were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. At 14 days’ follow-up after a positive test, 735 patients (22.8%), were hospitalized, 107 (3.3%) had severe outcomes, and 4 (0.12%) had died. Severe outcomes were significantly more likely in children aged 5-10 years and 10-18 years vs. less than 1 year (odds ratios, 1.60 and 2.39, respectively), and in children with a self-reported chronic illness (OR, 2.34) or a prior episode of pneumonia (OR, 3.15).

Severe outcomes were more likely in patients who presented with symptoms that started 4-7 days before seeking care, compared with those whose symptoms started 0-3 days before seeking care (OR, 2.22).

The researchers also reviewed data from a subgroup of 2,510 individuals who were discharged home from the ED after initial testing. At 14 days’ follow-up, 50 of these patients (2.0%) were hospitalized and 12 (0.5%) had severe outcomes. In addition, the researchers found that the risk of severe outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19–positive youth was nearly four times higher, compared with hospitalized youth who tested negative for COVID-19 (risk difference, 3.9%).

Previous retrospective studies of severe outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 have yielded varying results, in part because of the variation in study populations, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Our study population provides a risk estimate for youths brought for ED care.” Therefore, “Our lower estimate of severe disease likely reflects our stringent definition, which required the occurrence of complications or specific invasive interventions,” they said.

The study limitations included the potential overestimation of the risk of severe outcomes because patients were recruited in the ED, the researchers noted. Other limitations included variation in regional case definitions, screening criteria, and testing capacity among different sites and time periods. “Thus, 5% of our SARS-CoV-2–positive participants were asymptomatic – most of whom were tested as they were positive contacts of known cases or as part of routine screening procedures,” they said. The findings also are not generalizable to all community EDs and did not account for variants, they added.

However, the results were strengthened by the ability to compare outcomes for children with positive tests to similar children with negative tests, and add to the literature showing an increased risk of severe outcomes for those hospitalized with positive tests, the researchers concluded.

Data may inform clinical decisions

“The data [in the current study] are concerning for severe outcomes for children even prior to the Omicron strain,” said Margaret Thew, DNP, FP-BC, of Children’s Wisconsin-Milwaukee Hospital, in an interview. “Presently, the number of children infected with the Omicron strain is much higher and hospitalizations among children are at their highest since COVID-19 began,” she said. “For medical providers caring for this population, the study sheds light on pediatric patients who may be at higher risk of severe illness when they become infected with COVID-19,” she added.

“I was surprised by how high the number of pediatric patients hospitalized (22%) and the percentage (3%) with severe disease were during this time,” given that the timeline for these data preceded the spread of the Omicron strain, said Ms. Thew. “The risk of prior pneumonia was quite surprising. I do not recall seeing prior pneumonia as a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 with children or adults,” she added.

The take-home messaging for clinicians caring for children and adolescents is the added knowledge of the risk factors for severe outcomes from COVID-19, including the 10-18 age range, chronic illness, prior pneumonia, and longer symptom duration before seeking care in the ED, Ms. Thew emphasized.

However, additional research is needed on the impact of the new strains of COVID-19 on pediatric and adolescent hospitalizations, Ms. Thew said. Research also is needed on the other illnesses that have resulted from COVID-19, including illness requiring antibiotic use or medical interventions or treatments, and on the risk of combined COVID-19 and influenza viruses, she noted.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, the Alberta Health Services University of Calgary Clinical Research Fund, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the COVID-19 Research Accelerator Funding Track (CRAFT) Program at the University of California, Davis, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Division of Emergency Medicine Small Grants Program. Lead author Dr. Funk was supported by the University of Calgary Eyes-High Post-Doctoral Research Fund, but had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: 5 days of antibiotics better than 10 days

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.