User login

Flesh-Colored Pinpoint Papules With Fine White Spicules on the Upper Body

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

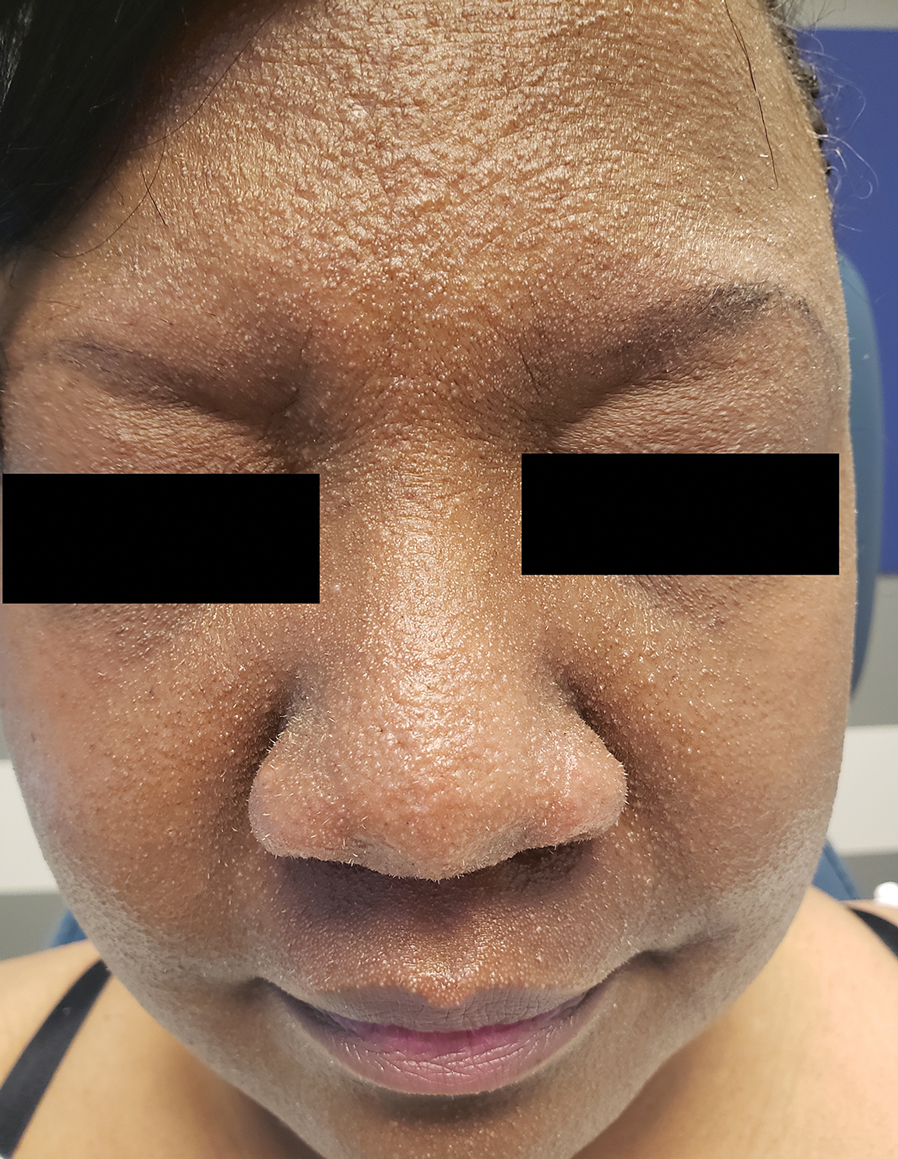

A 54-year-old Black woman presented with a rash that developed 6 months after a renal transplant due to a history of systemic lupus erythematosus with lupus nephritis. She was started on mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus after the transplant but was switched to cyclosporine because of BK viremia. The rash developed 1 week after cyclosporine was initiated and consisted of pruritic papules that started on the face and spread to the trunk and arms. Physical examination revealed innumerable follicular-based, keratotic, flesh-colored, pinpoint papules with fine white spicules on the face (top), neck, chest, arms, and back. Leonine facies was seen along the glabella with madarosis of the lateral eyebrows (top) and ears (bottom).

Predicting and Understanding Vaccine Response Determinants

In this column, I recently discussed the impact of the microbiome on childhood vaccine responses. My group has been expanding our research on the topic of childhood vaccine response and its relationship to infection proneness. Therefore, I want to share new research findings.

Immune responsiveness to vaccines varies among children, leaving some susceptible to infections. We also have evidence that the immune deficiencies that contribute to poor vaccine responsiveness also manifest in children as respiratory infection proneness.

Predicting Vaccine Response in the Neonatal Period

The first 100 days of life is an amazing transition time in early life. During that time, the immune system is highly influenced by environmental factors that generate epigenetic changes affecting vaccine responsiveness. Some publications have used the term “window of opportunity,” because it is thought that interventions to change a negative trajectory to a positive one for vaccine responsiveness have a better potential to be effective. Predicting which children will be poorly responsive to vaccines would be desirable, so those children could be specifically identified for intervention. Doing so in the neonatal age time frame using easy-to-obtain clinical samples would be a bonus.

In our most recent study, we sought to identify cytokine biosignatures in the neonatal period, measured in convenient nasopharyngeal secretions, that predict vaccine responses, measured as antibody levels to various vaccines at 1 year of life. Secondly, we assessed the effect of antibiotic exposures on vaccine responses in the study cohort. Third, we tested for induction of CD4+ T-cell vaccine-specific immune memory at infant age 1 year. Fourth, we studied antigen presenting cells (APCs) at rest and in response to an adjuvant called R848, known to stimulate toll-like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonist, to assess its effects on the immune cells of low vaccine responder children, compared with other children.1

The study population consisted of 101 infants recruited from two primary care pediatric practices in/near Rochester, New York. Children lived in suburban and rural environments. Enrollment and sampling occurred during 2017-2020. All participants received regularly scheduled childhood vaccinations according to the recommendations by US Centers for Disease Control. Nasopharyngeal swabs were used to collect nasal secretions. Antibody titers against six antigens were measured at approximately 1 year of age from all 72 available blood samples. The protective threshold of the corresponding vaccine antigen divided each vaccine-induced antibody level and the ratio considered a normalized titer. The normalized antibody titers were used to define vaccine responsiveness groups as Low Vaccine Responder (bottom 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children), as Normal Vaccine Responder (25-75th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 36 children) and as High Vaccine Responder (top 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children).

We found that specific nasal cytokine levels measured at newborn age 1 week old, 2 weeks old, and 3 weeks old were predictive of the vaccine response groupings measured at child age 1 year old, following their primary series of vaccinations. The P values varied between less than .05 to .001.

Five newborns had antibiotic exposure at/near the time of birth; 4 [80%] of the 5 were Low Vaccine Responders vs 1 [2%] of 60 Normal+High Vaccine Responder children, P = .006. Also, the cumulative days of antibiotic exposure up to 1 year was highly associated with low vaccine responders, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children (P = 2 x 10-16).

We found that Low Vaccine Responder infants had reduced vaccine-specific T-helper memory cells producing INFg and IL-2 (Th1 cytokines) and IL-4 (Th2 cytokines), compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children. In the absence of sufficient numbers of antigen-specific memory CD4+ T-cells, a child would become unprotected from the target infection that the vaccines were intended to prevent after the antibody levels wane.

We found that Low Vaccine Responder antigen-presenting cells are different from those in normal vaccine responders and they can be distinguished when at rest and when stimulated by a specific adjuvant — R848. Our previous findings suggested that Low Vaccine Responder children have a prolonged neonatal-like immune profile (PNIP).2 Therefore, stimulating the immune system of a Low Vaccine Responder could shift their cellular immune responses to behave like cells of Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

In summary, we identified cytokine biosignatures measured in nasopharyngeal secretions in the neonatal period that predicted vaccine response groups measured as antibody levels at 1 year of life. We showed that reduced vaccine responsiveness was associated with antibiotic exposure at/near birth and with cumulative exposure during the first year of life. We found that Low Vaccine Responder children at 1 year old have fewer vaccine-specific memory CD4+ Th1 and Th2-cells and that antigen-presenting cells at rest and in response to R848 antigen stimulation differ, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

Future work by our group will focus on exploring early-life risk factors that influence differences in vaccine responsiveness and interventions that might shift a child’s responsiveness from low to normal or high.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (New York) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. Variability of Vaccine Responsiveness in Young Children. J Infect Dis. 2023 Nov 22:jiad524. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiad524.

2. Pichichero ME et al. Functional Immune Cell Differences Associated with Low Vaccine Responses in Infants. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

In this column, I recently discussed the impact of the microbiome on childhood vaccine responses. My group has been expanding our research on the topic of childhood vaccine response and its relationship to infection proneness. Therefore, I want to share new research findings.

Immune responsiveness to vaccines varies among children, leaving some susceptible to infections. We also have evidence that the immune deficiencies that contribute to poor vaccine responsiveness also manifest in children as respiratory infection proneness.

Predicting Vaccine Response in the Neonatal Period

The first 100 days of life is an amazing transition time in early life. During that time, the immune system is highly influenced by environmental factors that generate epigenetic changes affecting vaccine responsiveness. Some publications have used the term “window of opportunity,” because it is thought that interventions to change a negative trajectory to a positive one for vaccine responsiveness have a better potential to be effective. Predicting which children will be poorly responsive to vaccines would be desirable, so those children could be specifically identified for intervention. Doing so in the neonatal age time frame using easy-to-obtain clinical samples would be a bonus.

In our most recent study, we sought to identify cytokine biosignatures in the neonatal period, measured in convenient nasopharyngeal secretions, that predict vaccine responses, measured as antibody levels to various vaccines at 1 year of life. Secondly, we assessed the effect of antibiotic exposures on vaccine responses in the study cohort. Third, we tested for induction of CD4+ T-cell vaccine-specific immune memory at infant age 1 year. Fourth, we studied antigen presenting cells (APCs) at rest and in response to an adjuvant called R848, known to stimulate toll-like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonist, to assess its effects on the immune cells of low vaccine responder children, compared with other children.1

The study population consisted of 101 infants recruited from two primary care pediatric practices in/near Rochester, New York. Children lived in suburban and rural environments. Enrollment and sampling occurred during 2017-2020. All participants received regularly scheduled childhood vaccinations according to the recommendations by US Centers for Disease Control. Nasopharyngeal swabs were used to collect nasal secretions. Antibody titers against six antigens were measured at approximately 1 year of age from all 72 available blood samples. The protective threshold of the corresponding vaccine antigen divided each vaccine-induced antibody level and the ratio considered a normalized titer. The normalized antibody titers were used to define vaccine responsiveness groups as Low Vaccine Responder (bottom 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children), as Normal Vaccine Responder (25-75th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 36 children) and as High Vaccine Responder (top 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children).

We found that specific nasal cytokine levels measured at newborn age 1 week old, 2 weeks old, and 3 weeks old were predictive of the vaccine response groupings measured at child age 1 year old, following their primary series of vaccinations. The P values varied between less than .05 to .001.

Five newborns had antibiotic exposure at/near the time of birth; 4 [80%] of the 5 were Low Vaccine Responders vs 1 [2%] of 60 Normal+High Vaccine Responder children, P = .006. Also, the cumulative days of antibiotic exposure up to 1 year was highly associated with low vaccine responders, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children (P = 2 x 10-16).

We found that Low Vaccine Responder infants had reduced vaccine-specific T-helper memory cells producing INFg and IL-2 (Th1 cytokines) and IL-4 (Th2 cytokines), compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children. In the absence of sufficient numbers of antigen-specific memory CD4+ T-cells, a child would become unprotected from the target infection that the vaccines were intended to prevent after the antibody levels wane.

We found that Low Vaccine Responder antigen-presenting cells are different from those in normal vaccine responders and they can be distinguished when at rest and when stimulated by a specific adjuvant — R848. Our previous findings suggested that Low Vaccine Responder children have a prolonged neonatal-like immune profile (PNIP).2 Therefore, stimulating the immune system of a Low Vaccine Responder could shift their cellular immune responses to behave like cells of Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

In summary, we identified cytokine biosignatures measured in nasopharyngeal secretions in the neonatal period that predicted vaccine response groups measured as antibody levels at 1 year of life. We showed that reduced vaccine responsiveness was associated with antibiotic exposure at/near birth and with cumulative exposure during the first year of life. We found that Low Vaccine Responder children at 1 year old have fewer vaccine-specific memory CD4+ Th1 and Th2-cells and that antigen-presenting cells at rest and in response to R848 antigen stimulation differ, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

Future work by our group will focus on exploring early-life risk factors that influence differences in vaccine responsiveness and interventions that might shift a child’s responsiveness from low to normal or high.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (New York) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. Variability of Vaccine Responsiveness in Young Children. J Infect Dis. 2023 Nov 22:jiad524. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiad524.

2. Pichichero ME et al. Functional Immune Cell Differences Associated with Low Vaccine Responses in Infants. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

In this column, I recently discussed the impact of the microbiome on childhood vaccine responses. My group has been expanding our research on the topic of childhood vaccine response and its relationship to infection proneness. Therefore, I want to share new research findings.

Immune responsiveness to vaccines varies among children, leaving some susceptible to infections. We also have evidence that the immune deficiencies that contribute to poor vaccine responsiveness also manifest in children as respiratory infection proneness.

Predicting Vaccine Response in the Neonatal Period

The first 100 days of life is an amazing transition time in early life. During that time, the immune system is highly influenced by environmental factors that generate epigenetic changes affecting vaccine responsiveness. Some publications have used the term “window of opportunity,” because it is thought that interventions to change a negative trajectory to a positive one for vaccine responsiveness have a better potential to be effective. Predicting which children will be poorly responsive to vaccines would be desirable, so those children could be specifically identified for intervention. Doing so in the neonatal age time frame using easy-to-obtain clinical samples would be a bonus.

In our most recent study, we sought to identify cytokine biosignatures in the neonatal period, measured in convenient nasopharyngeal secretions, that predict vaccine responses, measured as antibody levels to various vaccines at 1 year of life. Secondly, we assessed the effect of antibiotic exposures on vaccine responses in the study cohort. Third, we tested for induction of CD4+ T-cell vaccine-specific immune memory at infant age 1 year. Fourth, we studied antigen presenting cells (APCs) at rest and in response to an adjuvant called R848, known to stimulate toll-like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonist, to assess its effects on the immune cells of low vaccine responder children, compared with other children.1

The study population consisted of 101 infants recruited from two primary care pediatric practices in/near Rochester, New York. Children lived in suburban and rural environments. Enrollment and sampling occurred during 2017-2020. All participants received regularly scheduled childhood vaccinations according to the recommendations by US Centers for Disease Control. Nasopharyngeal swabs were used to collect nasal secretions. Antibody titers against six antigens were measured at approximately 1 year of age from all 72 available blood samples. The protective threshold of the corresponding vaccine antigen divided each vaccine-induced antibody level and the ratio considered a normalized titer. The normalized antibody titers were used to define vaccine responsiveness groups as Low Vaccine Responder (bottom 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children), as Normal Vaccine Responder (25-75th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 36 children) and as High Vaccine Responder (top 25th percentile of vaccine responders, n = 18 children).

We found that specific nasal cytokine levels measured at newborn age 1 week old, 2 weeks old, and 3 weeks old were predictive of the vaccine response groupings measured at child age 1 year old, following their primary series of vaccinations. The P values varied between less than .05 to .001.

Five newborns had antibiotic exposure at/near the time of birth; 4 [80%] of the 5 were Low Vaccine Responders vs 1 [2%] of 60 Normal+High Vaccine Responder children, P = .006. Also, the cumulative days of antibiotic exposure up to 1 year was highly associated with low vaccine responders, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children (P = 2 x 10-16).

We found that Low Vaccine Responder infants had reduced vaccine-specific T-helper memory cells producing INFg and IL-2 (Th1 cytokines) and IL-4 (Th2 cytokines), compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children. In the absence of sufficient numbers of antigen-specific memory CD4+ T-cells, a child would become unprotected from the target infection that the vaccines were intended to prevent after the antibody levels wane.

We found that Low Vaccine Responder antigen-presenting cells are different from those in normal vaccine responders and they can be distinguished when at rest and when stimulated by a specific adjuvant — R848. Our previous findings suggested that Low Vaccine Responder children have a prolonged neonatal-like immune profile (PNIP).2 Therefore, stimulating the immune system of a Low Vaccine Responder could shift their cellular immune responses to behave like cells of Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

In summary, we identified cytokine biosignatures measured in nasopharyngeal secretions in the neonatal period that predicted vaccine response groups measured as antibody levels at 1 year of life. We showed that reduced vaccine responsiveness was associated with antibiotic exposure at/near birth and with cumulative exposure during the first year of life. We found that Low Vaccine Responder children at 1 year old have fewer vaccine-specific memory CD4+ Th1 and Th2-cells and that antigen-presenting cells at rest and in response to R848 antigen stimulation differ, compared with Normal+High Vaccine Responder children.

Future work by our group will focus on exploring early-life risk factors that influence differences in vaccine responsiveness and interventions that might shift a child’s responsiveness from low to normal or high.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (New York) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. Variability of Vaccine Responsiveness in Young Children. J Infect Dis. 2023 Nov 22:jiad524. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiad524.

2. Pichichero ME et al. Functional Immune Cell Differences Associated with Low Vaccine Responses in Infants. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

Latest Breakthroughs in Molluscum Contagiosum Therapy

Molluscum contagiosum (ie, molluscum) is a ubiquitous infection caused by the poxvirus molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV). Although skin deep, molluscum shares many factors with the more virulent poxviridae. Moisture and trauma can cause viral material to be released from the pearly papules through a small opening, which also allows entry of bacteria and medications into the lesion. The MCV is transmitted by direct contact with skin or via fomites.1

Molluscum can affect children of any age, with MCV type 1 peaking in toddlers and school-aged children and MCV type 2 after the sexual debut. The prevalence of molluscum has increased since the 1980s. It is stressful for children and caregivers and poses challenges in schools as well as sports such as swimming, wrestling, and karate.1,2

For the first time, we have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products to treat MCV infections. Previously, only off-label agents were used. Therefore, we have to contemplate why treatment is important to our patients.

What type of care is required for molluscum?

Counseling is the first and only mandatory treatment, which consists of 3 parts: natural history, risk factors for spread, and options for therapy. The natural history of molluscum in children is early spread, contagion to oneself and others (as high as 60% of sibling co-bathers3), triggering of dermatitis, eventual onset of the beginning-of-the-end (BOTE) sign, and eventually clearance. The natural history in adults is poorly understood.

Early clearance is uncommon; reports have suggested 45.6% to 48.4% of affected patients are clear at 1 year and 69.5% to 72.6% at 1.5 years.4 For many children, especially those with atopic dermatitis (AD), lesions linger and often spread, with many experiencing disease for 3 to 4 years. Fomites such as towels, washcloths, and sponges can transfer the virus and spread lesions; therefore, I advise patients to gently pat their skin dry, wash towels frequently, and avoid sharing bathing equipment.1,3,5 Children and adults with immunosuppression may have a greater number of lesions and more prolonged course of disease, including those with HIV as well as DOC8 and CARD11 mutations.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) emphasizes that children should not be excluded from attending child care/school or from swimming in public pools but lesions should be covered.6 Lesions, especially those in the antecubital region, can trigger new-onset AD or AD flares.3 In response, gentle skin care including fragrance-free cleansers and periodic application of moisturizers may ward off AD. Topical corticosteroids are preferred.

Dermatitis in MCV is a great mimicker and can resemble erythema multiforme, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, impetigo, and AD.1 Superinfection recently has been reported; however, in a retrospective analysis of 56 patients with inflamed lesions secondary to molluscum infection, only 7 had positive bacterial cultures, which supports the idea of the swelling and redness of inflammation as a mimic for infection.7 When true infection does occur, tender, swollen, pus-filled lesions should be lanced and cultured.1,7,8

When should we consider therapy?

Therapy is highly dependent on the child, the caregiver, and the social circumstances.1 More than 80% of parents are anxious about molluscum, and countless children are embarrassed or ashamed.1 Ultimately, an unhappy child merits care. The AAP cites the following as reasons to treat: “(1) alleviate discomfort, including itching; (2) reduce autoinoculation; (3) limit transmission of the virus to close contacts; (4) reduce cosmetic concerns; and (5) prevent secondary infection.”6 For adults, we should consider limitations to intimacy and reduction of sexual transmission risk.6

Treatment can be based on the number of lesions. With a few lesions (<3), therapy is worthwhile if they are unsightly; appear on exposed skin causing embarrassment; and/or are itchy, uncomfortable, or large. In a report of 300 children with molluscum treated with cantharidin, most patients choosing therapy had 10 to 20 lesions, but this was over multiple visits.8 Looking at a 2018 data set of 50 patients (all-comers) with molluscum,3 the mean number of lesions was 10 (median, 7); 3 lesions were 1 SD below, while 14, 17, and 45 were 1, 2, and 3 SDs above, respectively. This data set shows that patients can develop more lesions rapidly, and most children have many visible lesions (N.B. Silverberg, MD, unpublished data).

Because each lesion contains infectious viral particles and patients scratch, more lesions are equated to greater autoinoculation and contagion. In addition to the AAP criteria, treatment can be considered for households with immunocompromised individuals, children at risk for new-onset AD, or those with AD at risk for flare. For patients with 45 lesions or more (3 SDs), clearance is harder to achieve with 2 sessions of in-office therapy, and multiple methods or the addition of immunomodulatory therapeutics should be considered.

Do we have to clear every lesion?

New molluscum lesions may arise until a patient achieves immunity, and they may appear more than a month after inoculation, making it difficult to keep up with the rapid spread. Latency between exposure and lesion development usually is 2 to 7 weeks but may be as long as 6 months, making it difficult to prevent spread.6 Therefore, when we treat, we should not promise full clearance to patients and parents. Rather, we should inform them that new lesions may develop later, and therapy is only effective on visible lesions. In a recent study, a 50% clearance of lesions was the satisfactory threshold for parents, demonstrating that satisfaction is possible with partial clearance.9

What is new in therapeutics for molluscum?

Molluscum therapies are either destructive, immunomodulatory, or antiviral. Two agents now are approved by the FDA for the treatment of molluscum infections.

Berdazimer gel 10.3% is approved for patients 1 year or older, but it is not yet available. This agent has both immunomodulatory and antiviral properties.10 It features a home therapy that is mixed on a small palette, then painted on by the patient or parent once daily for 12 weeks. Study outcomes demonstrated more than 50% lesional clearance.11,12 Complete clearance was achieved in at least 30% of patients.12A proprietary topical version of cantharidin 0.7% in flexible collodion is now FDA approved for patients 2 years and older. This vesicant-triggering iatrogenic is targeted at creating blisters overlying molluscum lesions. It is conceptually similar to older versions but with some enhanced features.5,13,14 This version was used for therapy every 3 weeks for up to 4 sessions in clinical trials. Safety is similar across all body sites treated (nonmucosal and not near the mucosal surfaces) but not for mucosa, the mid face, or eyelids.13 Complete lesion clearance was 46.3% to 54% and statistically greater than placebo (P<.001).14Both agents are well tolerated in children with AD; adverse effects include blistering with cantharidin and dermatitislike symptoms with berdazimer.15,16 These therapies have the advantage of being easy to use.

Final Thoughts

We have entered an era of high-quality molluscum therapy. Patient care involves developing a good knowledge of the agents, incorporating shared decision-making with patients and caregivers, and addressing therapy in the context of comorbid diseases such as AD.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum: an update. Cutis. 2019;104:301-305, E1-E2.

- Thompson AJ, Matinpour K, Hardin J, et al. Molluscum gladiatorum. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt0nj121n1.

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018;102:191-194.

- Basdag H, Rainer BM, Cohen BA. Molluscum contagiosum: to treat or not to treat? experience with 170 children in an outpatient clinic setting in the northeastern United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:353-357. doi:10.1111/pde.12504

- Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

- Molluscum contagiosum. In: Kimberlin DW, Lynfield R, Barnett ED, et al (eds). Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 32nd edition. American Academy of Pediatrics. May 26, 2021. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://publications.aap.org/redbook/book/347/chapter/5754264/Molluscum-Contagiosum

- Gross I, Ben Nachum N, Molho-Pessach V, et al. The molluscum contagiosum BOTE sign—infected or inflamed? Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:476-479. doi:10.1111/pde.14124

- Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:503-507. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.106370

- Maeda-Chubachi T, McLeod L, Enloe C, et al. Defining clinically meaningful improvement in molluscum contagiosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:443-445. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.033

- Guttman-Yassky E, Gallo RL, Pavel AB, et al. A nitric oxide-releasing topical medication as a potential treatment option for atopic dermatitis through antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:2531-2535.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.04.013

- Browning JC, Cartwright M, Thorla I Jr, et al. A patient-centered perspective of molluscum contagiosum as reported by B-SIMPLE4 Clinical Trial patients and caregivers: Global Impression of Change and Exit Interview substudy results. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:119-133. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00733-9

- Sugarman JL, Hebert A, Browning JC, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum: an integrated analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:299-308. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.066

- Eichenfield LF, Kwong P, Gonzalez ME, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102 (cantharidin, 0.7% w/v) in molluscum contagiosum by body region: post hoc pooled analyses from two phase III randomized trials. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:42-47.

- Eichenfield LF, McFalda W, Brabec B, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102, a proprietary, drug-device combination product containing cantharidin, 0.7% (w/v), in children and adults with molluscum contagiosum: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1315-1323. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3238

- Paller AS, Green LJ, Silverberg N, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol.Published online February 27, 2024. doi:10.1111/pde.15575

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Mancini A, et al. Therapeutic approaches and special considerations for treating molluscum contagiosum. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1185-1190. doi:10.36849/jdd.6383

Molluscum contagiosum (ie, molluscum) is a ubiquitous infection caused by the poxvirus molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV). Although skin deep, molluscum shares many factors with the more virulent poxviridae. Moisture and trauma can cause viral material to be released from the pearly papules through a small opening, which also allows entry of bacteria and medications into the lesion. The MCV is transmitted by direct contact with skin or via fomites.1

Molluscum can affect children of any age, with MCV type 1 peaking in toddlers and school-aged children and MCV type 2 after the sexual debut. The prevalence of molluscum has increased since the 1980s. It is stressful for children and caregivers and poses challenges in schools as well as sports such as swimming, wrestling, and karate.1,2

For the first time, we have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products to treat MCV infections. Previously, only off-label agents were used. Therefore, we have to contemplate why treatment is important to our patients.

What type of care is required for molluscum?

Counseling is the first and only mandatory treatment, which consists of 3 parts: natural history, risk factors for spread, and options for therapy. The natural history of molluscum in children is early spread, contagion to oneself and others (as high as 60% of sibling co-bathers3), triggering of dermatitis, eventual onset of the beginning-of-the-end (BOTE) sign, and eventually clearance. The natural history in adults is poorly understood.

Early clearance is uncommon; reports have suggested 45.6% to 48.4% of affected patients are clear at 1 year and 69.5% to 72.6% at 1.5 years.4 For many children, especially those with atopic dermatitis (AD), lesions linger and often spread, with many experiencing disease for 3 to 4 years. Fomites such as towels, washcloths, and sponges can transfer the virus and spread lesions; therefore, I advise patients to gently pat their skin dry, wash towels frequently, and avoid sharing bathing equipment.1,3,5 Children and adults with immunosuppression may have a greater number of lesions and more prolonged course of disease, including those with HIV as well as DOC8 and CARD11 mutations.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) emphasizes that children should not be excluded from attending child care/school or from swimming in public pools but lesions should be covered.6 Lesions, especially those in the antecubital region, can trigger new-onset AD or AD flares.3 In response, gentle skin care including fragrance-free cleansers and periodic application of moisturizers may ward off AD. Topical corticosteroids are preferred.

Dermatitis in MCV is a great mimicker and can resemble erythema multiforme, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, impetigo, and AD.1 Superinfection recently has been reported; however, in a retrospective analysis of 56 patients with inflamed lesions secondary to molluscum infection, only 7 had positive bacterial cultures, which supports the idea of the swelling and redness of inflammation as a mimic for infection.7 When true infection does occur, tender, swollen, pus-filled lesions should be lanced and cultured.1,7,8

When should we consider therapy?

Therapy is highly dependent on the child, the caregiver, and the social circumstances.1 More than 80% of parents are anxious about molluscum, and countless children are embarrassed or ashamed.1 Ultimately, an unhappy child merits care. The AAP cites the following as reasons to treat: “(1) alleviate discomfort, including itching; (2) reduce autoinoculation; (3) limit transmission of the virus to close contacts; (4) reduce cosmetic concerns; and (5) prevent secondary infection.”6 For adults, we should consider limitations to intimacy and reduction of sexual transmission risk.6

Treatment can be based on the number of lesions. With a few lesions (<3), therapy is worthwhile if they are unsightly; appear on exposed skin causing embarrassment; and/or are itchy, uncomfortable, or large. In a report of 300 children with molluscum treated with cantharidin, most patients choosing therapy had 10 to 20 lesions, but this was over multiple visits.8 Looking at a 2018 data set of 50 patients (all-comers) with molluscum,3 the mean number of lesions was 10 (median, 7); 3 lesions were 1 SD below, while 14, 17, and 45 were 1, 2, and 3 SDs above, respectively. This data set shows that patients can develop more lesions rapidly, and most children have many visible lesions (N.B. Silverberg, MD, unpublished data).

Because each lesion contains infectious viral particles and patients scratch, more lesions are equated to greater autoinoculation and contagion. In addition to the AAP criteria, treatment can be considered for households with immunocompromised individuals, children at risk for new-onset AD, or those with AD at risk for flare. For patients with 45 lesions or more (3 SDs), clearance is harder to achieve with 2 sessions of in-office therapy, and multiple methods or the addition of immunomodulatory therapeutics should be considered.

Do we have to clear every lesion?

New molluscum lesions may arise until a patient achieves immunity, and they may appear more than a month after inoculation, making it difficult to keep up with the rapid spread. Latency between exposure and lesion development usually is 2 to 7 weeks but may be as long as 6 months, making it difficult to prevent spread.6 Therefore, when we treat, we should not promise full clearance to patients and parents. Rather, we should inform them that new lesions may develop later, and therapy is only effective on visible lesions. In a recent study, a 50% clearance of lesions was the satisfactory threshold for parents, demonstrating that satisfaction is possible with partial clearance.9

What is new in therapeutics for molluscum?

Molluscum therapies are either destructive, immunomodulatory, or antiviral. Two agents now are approved by the FDA for the treatment of molluscum infections.

Berdazimer gel 10.3% is approved for patients 1 year or older, but it is not yet available. This agent has both immunomodulatory and antiviral properties.10 It features a home therapy that is mixed on a small palette, then painted on by the patient or parent once daily for 12 weeks. Study outcomes demonstrated more than 50% lesional clearance.11,12 Complete clearance was achieved in at least 30% of patients.12A proprietary topical version of cantharidin 0.7% in flexible collodion is now FDA approved for patients 2 years and older. This vesicant-triggering iatrogenic is targeted at creating blisters overlying molluscum lesions. It is conceptually similar to older versions but with some enhanced features.5,13,14 This version was used for therapy every 3 weeks for up to 4 sessions in clinical trials. Safety is similar across all body sites treated (nonmucosal and not near the mucosal surfaces) but not for mucosa, the mid face, or eyelids.13 Complete lesion clearance was 46.3% to 54% and statistically greater than placebo (P<.001).14Both agents are well tolerated in children with AD; adverse effects include blistering with cantharidin and dermatitislike symptoms with berdazimer.15,16 These therapies have the advantage of being easy to use.

Final Thoughts

We have entered an era of high-quality molluscum therapy. Patient care involves developing a good knowledge of the agents, incorporating shared decision-making with patients and caregivers, and addressing therapy in the context of comorbid diseases such as AD.

Molluscum contagiosum (ie, molluscum) is a ubiquitous infection caused by the poxvirus molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV). Although skin deep, molluscum shares many factors with the more virulent poxviridae. Moisture and trauma can cause viral material to be released from the pearly papules through a small opening, which also allows entry of bacteria and medications into the lesion. The MCV is transmitted by direct contact with skin or via fomites.1

Molluscum can affect children of any age, with MCV type 1 peaking in toddlers and school-aged children and MCV type 2 after the sexual debut. The prevalence of molluscum has increased since the 1980s. It is stressful for children and caregivers and poses challenges in schools as well as sports such as swimming, wrestling, and karate.1,2

For the first time, we have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products to treat MCV infections. Previously, only off-label agents were used. Therefore, we have to contemplate why treatment is important to our patients.

What type of care is required for molluscum?

Counseling is the first and only mandatory treatment, which consists of 3 parts: natural history, risk factors for spread, and options for therapy. The natural history of molluscum in children is early spread, contagion to oneself and others (as high as 60% of sibling co-bathers3), triggering of dermatitis, eventual onset of the beginning-of-the-end (BOTE) sign, and eventually clearance. The natural history in adults is poorly understood.

Early clearance is uncommon; reports have suggested 45.6% to 48.4% of affected patients are clear at 1 year and 69.5% to 72.6% at 1.5 years.4 For many children, especially those with atopic dermatitis (AD), lesions linger and often spread, with many experiencing disease for 3 to 4 years. Fomites such as towels, washcloths, and sponges can transfer the virus and spread lesions; therefore, I advise patients to gently pat their skin dry, wash towels frequently, and avoid sharing bathing equipment.1,3,5 Children and adults with immunosuppression may have a greater number of lesions and more prolonged course of disease, including those with HIV as well as DOC8 and CARD11 mutations.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) emphasizes that children should not be excluded from attending child care/school or from swimming in public pools but lesions should be covered.6 Lesions, especially those in the antecubital region, can trigger new-onset AD or AD flares.3 In response, gentle skin care including fragrance-free cleansers and periodic application of moisturizers may ward off AD. Topical corticosteroids are preferred.

Dermatitis in MCV is a great mimicker and can resemble erythema multiforme, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, impetigo, and AD.1 Superinfection recently has been reported; however, in a retrospective analysis of 56 patients with inflamed lesions secondary to molluscum infection, only 7 had positive bacterial cultures, which supports the idea of the swelling and redness of inflammation as a mimic for infection.7 When true infection does occur, tender, swollen, pus-filled lesions should be lanced and cultured.1,7,8

When should we consider therapy?

Therapy is highly dependent on the child, the caregiver, and the social circumstances.1 More than 80% of parents are anxious about molluscum, and countless children are embarrassed or ashamed.1 Ultimately, an unhappy child merits care. The AAP cites the following as reasons to treat: “(1) alleviate discomfort, including itching; (2) reduce autoinoculation; (3) limit transmission of the virus to close contacts; (4) reduce cosmetic concerns; and (5) prevent secondary infection.”6 For adults, we should consider limitations to intimacy and reduction of sexual transmission risk.6

Treatment can be based on the number of lesions. With a few lesions (<3), therapy is worthwhile if they are unsightly; appear on exposed skin causing embarrassment; and/or are itchy, uncomfortable, or large. In a report of 300 children with molluscum treated with cantharidin, most patients choosing therapy had 10 to 20 lesions, but this was over multiple visits.8 Looking at a 2018 data set of 50 patients (all-comers) with molluscum,3 the mean number of lesions was 10 (median, 7); 3 lesions were 1 SD below, while 14, 17, and 45 were 1, 2, and 3 SDs above, respectively. This data set shows that patients can develop more lesions rapidly, and most children have many visible lesions (N.B. Silverberg, MD, unpublished data).

Because each lesion contains infectious viral particles and patients scratch, more lesions are equated to greater autoinoculation and contagion. In addition to the AAP criteria, treatment can be considered for households with immunocompromised individuals, children at risk for new-onset AD, or those with AD at risk for flare. For patients with 45 lesions or more (3 SDs), clearance is harder to achieve with 2 sessions of in-office therapy, and multiple methods or the addition of immunomodulatory therapeutics should be considered.

Do we have to clear every lesion?

New molluscum lesions may arise until a patient achieves immunity, and they may appear more than a month after inoculation, making it difficult to keep up with the rapid spread. Latency between exposure and lesion development usually is 2 to 7 weeks but may be as long as 6 months, making it difficult to prevent spread.6 Therefore, when we treat, we should not promise full clearance to patients and parents. Rather, we should inform them that new lesions may develop later, and therapy is only effective on visible lesions. In a recent study, a 50% clearance of lesions was the satisfactory threshold for parents, demonstrating that satisfaction is possible with partial clearance.9

What is new in therapeutics for molluscum?

Molluscum therapies are either destructive, immunomodulatory, or antiviral. Two agents now are approved by the FDA for the treatment of molluscum infections.

Berdazimer gel 10.3% is approved for patients 1 year or older, but it is not yet available. This agent has both immunomodulatory and antiviral properties.10 It features a home therapy that is mixed on a small palette, then painted on by the patient or parent once daily for 12 weeks. Study outcomes demonstrated more than 50% lesional clearance.11,12 Complete clearance was achieved in at least 30% of patients.12A proprietary topical version of cantharidin 0.7% in flexible collodion is now FDA approved for patients 2 years and older. This vesicant-triggering iatrogenic is targeted at creating blisters overlying molluscum lesions. It is conceptually similar to older versions but with some enhanced features.5,13,14 This version was used for therapy every 3 weeks for up to 4 sessions in clinical trials. Safety is similar across all body sites treated (nonmucosal and not near the mucosal surfaces) but not for mucosa, the mid face, or eyelids.13 Complete lesion clearance was 46.3% to 54% and statistically greater than placebo (P<.001).14Both agents are well tolerated in children with AD; adverse effects include blistering with cantharidin and dermatitislike symptoms with berdazimer.15,16 These therapies have the advantage of being easy to use.

Final Thoughts

We have entered an era of high-quality molluscum therapy. Patient care involves developing a good knowledge of the agents, incorporating shared decision-making with patients and caregivers, and addressing therapy in the context of comorbid diseases such as AD.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum: an update. Cutis. 2019;104:301-305, E1-E2.

- Thompson AJ, Matinpour K, Hardin J, et al. Molluscum gladiatorum. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt0nj121n1.

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018;102:191-194.

- Basdag H, Rainer BM, Cohen BA. Molluscum contagiosum: to treat or not to treat? experience with 170 children in an outpatient clinic setting in the northeastern United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:353-357. doi:10.1111/pde.12504

- Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

- Molluscum contagiosum. In: Kimberlin DW, Lynfield R, Barnett ED, et al (eds). Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 32nd edition. American Academy of Pediatrics. May 26, 2021. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://publications.aap.org/redbook/book/347/chapter/5754264/Molluscum-Contagiosum

- Gross I, Ben Nachum N, Molho-Pessach V, et al. The molluscum contagiosum BOTE sign—infected or inflamed? Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:476-479. doi:10.1111/pde.14124

- Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:503-507. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.106370

- Maeda-Chubachi T, McLeod L, Enloe C, et al. Defining clinically meaningful improvement in molluscum contagiosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:443-445. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.033

- Guttman-Yassky E, Gallo RL, Pavel AB, et al. A nitric oxide-releasing topical medication as a potential treatment option for atopic dermatitis through antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:2531-2535.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.04.013

- Browning JC, Cartwright M, Thorla I Jr, et al. A patient-centered perspective of molluscum contagiosum as reported by B-SIMPLE4 Clinical Trial patients and caregivers: Global Impression of Change and Exit Interview substudy results. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:119-133. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00733-9

- Sugarman JL, Hebert A, Browning JC, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum: an integrated analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:299-308. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.066

- Eichenfield LF, Kwong P, Gonzalez ME, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102 (cantharidin, 0.7% w/v) in molluscum contagiosum by body region: post hoc pooled analyses from two phase III randomized trials. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:42-47.

- Eichenfield LF, McFalda W, Brabec B, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102, a proprietary, drug-device combination product containing cantharidin, 0.7% (w/v), in children and adults with molluscum contagiosum: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1315-1323. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3238

- Paller AS, Green LJ, Silverberg N, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol.Published online February 27, 2024. doi:10.1111/pde.15575

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Mancini A, et al. Therapeutic approaches and special considerations for treating molluscum contagiosum. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1185-1190. doi:10.36849/jdd.6383

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum: an update. Cutis. 2019;104:301-305, E1-E2.

- Thompson AJ, Matinpour K, Hardin J, et al. Molluscum gladiatorum. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt0nj121n1.

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018;102:191-194.

- Basdag H, Rainer BM, Cohen BA. Molluscum contagiosum: to treat or not to treat? experience with 170 children in an outpatient clinic setting in the northeastern United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:353-357. doi:10.1111/pde.12504

- Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

- Molluscum contagiosum. In: Kimberlin DW, Lynfield R, Barnett ED, et al (eds). Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 32nd edition. American Academy of Pediatrics. May 26, 2021. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://publications.aap.org/redbook/book/347/chapter/5754264/Molluscum-Contagiosum

- Gross I, Ben Nachum N, Molho-Pessach V, et al. The molluscum contagiosum BOTE sign—infected or inflamed? Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:476-479. doi:10.1111/pde.14124

- Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:503-507. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.106370

- Maeda-Chubachi T, McLeod L, Enloe C, et al. Defining clinically meaningful improvement in molluscum contagiosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:443-445. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.033

- Guttman-Yassky E, Gallo RL, Pavel AB, et al. A nitric oxide-releasing topical medication as a potential treatment option for atopic dermatitis through antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:2531-2535.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.04.013

- Browning JC, Cartwright M, Thorla I Jr, et al. A patient-centered perspective of molluscum contagiosum as reported by B-SIMPLE4 Clinical Trial patients and caregivers: Global Impression of Change and Exit Interview substudy results. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:119-133. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00733-9

- Sugarman JL, Hebert A, Browning JC, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum: an integrated analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:299-308. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.066

- Eichenfield LF, Kwong P, Gonzalez ME, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102 (cantharidin, 0.7% w/v) in molluscum contagiosum by body region: post hoc pooled analyses from two phase III randomized trials. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:42-47.

- Eichenfield LF, McFalda W, Brabec B, et al. Safety and efficacy of VP-102, a proprietary, drug-device combination product containing cantharidin, 0.7% (w/v), in children and adults with molluscum contagiosum: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1315-1323. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3238

- Paller AS, Green LJ, Silverberg N, et al. Berdazimer gel for molluscum contagiosum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol.Published online February 27, 2024. doi:10.1111/pde.15575

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Mancini A, et al. Therapeutic approaches and special considerations for treating molluscum contagiosum. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1185-1190. doi:10.36849/jdd.6383

Seniors in Households with Children Have Sixfold Higher Risk for Pneumococcal Disease

BARCELONA, SPAIN — Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacteria that causes pneumococcal disease, is sixfold more likely to colonize adults older than 60 years who have regular contact with children than those who do not, data from a community-based study showed.

However, there is “no clear evidence of adult-to-adult transmission,” and the researchers, led by Anne L. Wyllie, PhD, from the Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut, noted that the study results suggest “the main benefit of adult pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) immunization is to directly protect adults who are exposed to children, who still carry and transmit some vaccine-type pneumococci despite successful pediatric national immunization programs.”

The data show that relatively high pneumococcus carriage rates are seen in people who have regular contact with children, who have had contact in the previous 2 weeks, and who have had contact for extended periods, Dr. Wyllie explained.

Preschoolers in particular were found to be most likely to transmit pneumococcus to older adults. “It is the 24- to 59-month-olds who are most associated with pneumococcal carriage, more than 1- to 2-year-olds,” she reported. However, transmission rates from children younger than 1 year are higher than those from children aged 1-2 years, she added.

The findings were presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) 2024 global conference, formerly known as the ECCMID conference.

Originally Designed to Investigate Adult-to-Adult Transmission

The researchers wanted to understand the sources and dynamics of transmission, as well as the risk factors for pneumococcal disease in older adults, to help predict the effect of PCVs in people older than 60 years.