User login

Inexperience Diagnosing Syphilis Adding to Higher Rates

With rates of syphilis rising quickly in the United States and elsewhere, clinicians are having to up their game when it comes to diagnosing and treating an infection that they may not be paying enough attention to.

More than 200,000 cases of syphilis were reported in the United States in 2022, which is the highest number since 1950 and is a 17.3% increase over 2021, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The rate of infection has increased almost every year since a historic low in 2001.

And the trend is not limited to the United States. Last year, the infection rate in the United Kingdom hit a 50-year high, said David Mabey, BCh, DM, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections are also a major problem in low- and middle-income countries, he added, although good data are not always available.

Many of today’s healthcare professionals have little experience with the disease, shared Ina Park, MD, a sexually transmitted infections specialist at the University of California at San Francisco. “An entire generation of physicians — including myself — did not see any cases until we were well out of our training,” Dr. Park reported. “We’re really playing catch-up.”

A Centuries-Old Ailment

Dr. Park offered some advice on the challenges of diagnosing what can be an elusive infection at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2024 Annual Meeting in Denver. That advice boiled down to one simple rule: “Test, test, test.”

Because syphilis can mimic so many other conditions and can have long periods of latency, it can be easily missed or even misdiagnosed by experienced physicians, said Dr. Park. Clinicians need to keep it front of mind and have a lower threshold for testing, even if there are no obvious symptoms.

Following the CDC’s new recommendations for syphilis screening will help, she noted; every sexually active patient aged between 15 and 44 years who lives in a county with a syphilis infection rate of 4.6 per 100,000 people or higher should get the test. And clinicians should remain vigilant, even in areas with a lower prevalence. “If you can’t account for new symptoms in a sexually active patient, order a test,” said Dr. Park.

Complicated Cases

The lack of experience with syphilis affects not just diagnosis but also treatment, particularly for complex cases, said Khalil Ghanem, MD, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “When you don’t have to deal with something for a while, you forget how to deal with it,” he added.

At CROI, Dr. Ghanem offered suggestions for how to navigate complicated cases of ocular syphilis, otic syphilis, and neurosyphilis, and how to interpret test results when a patient’s antigen titers are being “unruly.”

With potential ocular or otic syphilis, you shouldn’t wait for a specialist like an ophthalmologist to weigh in but instead refer the patient directly to the emergency department because of the risk that the symptoms may become irreversible and result in permanent blindness or deafness. “You don’t want to dilly-dally with those conditions,” Dr. Ghanem said.

Closely monitoring a patient’s rapid plasma regain and venereal disease research laboratory antigen levels is the only way to manage syphilis and to determine whether the infection is responding to treatment, he noted, but sometimes those titers “don’t do what you think they should be doing” and fail to decline or even go up after treatment.

“You don’t know if they went up because the patient was re-infected, or they developed neurosyphilis, or there was a problem at the lab,” he said. “It can be challenging to interpret.”

To decipher confusing test results, Dr. Ghanem recommended getting a detailed history to understand whether a patient is at risk for reinfection, whether there are signs of neurosyphilis or other complications, whether pregnancy is possible, and so on. “Based on the answers, you can determine what the most rational approach to treatment would be,” he shared.

Drug Shortages

Efforts to get the infection under control have become more complicated. Last summer, Pfizer announced that it had run out of penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin), an injectable, long-acting drug that is one of the main treatments for syphilis and the only one that can be given to pregnant people. Supplies for children ran out at the end of June 2023, and supplies for adults were gone by the end of September.

Because Pfizer is the only company that manufactures penicillin G benzathine, there is no one to pick up the slack in the short-term, so the shortage is expected to continue until at least the middle of 2024.

In response, the US Food and Drug Administration has temporarily allowed the use of benzylpenicillin benzathine (Extencilline), a French formulation that has not been approved in the United States, until supplies of penicillin G benzathine are stabilized.

The shortage has shone a spotlight on the important issue of a lack of alternatives for the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy, which increases the risk for congenital syphilis. “Hopefully, this pushes the National Institutes of Health and others to step up their game on studies for alternative drugs for use in pregnancy,” Dr. Ghanem said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With rates of syphilis rising quickly in the United States and elsewhere, clinicians are having to up their game when it comes to diagnosing and treating an infection that they may not be paying enough attention to.

More than 200,000 cases of syphilis were reported in the United States in 2022, which is the highest number since 1950 and is a 17.3% increase over 2021, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The rate of infection has increased almost every year since a historic low in 2001.

And the trend is not limited to the United States. Last year, the infection rate in the United Kingdom hit a 50-year high, said David Mabey, BCh, DM, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections are also a major problem in low- and middle-income countries, he added, although good data are not always available.

Many of today’s healthcare professionals have little experience with the disease, shared Ina Park, MD, a sexually transmitted infections specialist at the University of California at San Francisco. “An entire generation of physicians — including myself — did not see any cases until we were well out of our training,” Dr. Park reported. “We’re really playing catch-up.”

A Centuries-Old Ailment

Dr. Park offered some advice on the challenges of diagnosing what can be an elusive infection at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2024 Annual Meeting in Denver. That advice boiled down to one simple rule: “Test, test, test.”

Because syphilis can mimic so many other conditions and can have long periods of latency, it can be easily missed or even misdiagnosed by experienced physicians, said Dr. Park. Clinicians need to keep it front of mind and have a lower threshold for testing, even if there are no obvious symptoms.

Following the CDC’s new recommendations for syphilis screening will help, she noted; every sexually active patient aged between 15 and 44 years who lives in a county with a syphilis infection rate of 4.6 per 100,000 people or higher should get the test. And clinicians should remain vigilant, even in areas with a lower prevalence. “If you can’t account for new symptoms in a sexually active patient, order a test,” said Dr. Park.

Complicated Cases

The lack of experience with syphilis affects not just diagnosis but also treatment, particularly for complex cases, said Khalil Ghanem, MD, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “When you don’t have to deal with something for a while, you forget how to deal with it,” he added.

At CROI, Dr. Ghanem offered suggestions for how to navigate complicated cases of ocular syphilis, otic syphilis, and neurosyphilis, and how to interpret test results when a patient’s antigen titers are being “unruly.”

With potential ocular or otic syphilis, you shouldn’t wait for a specialist like an ophthalmologist to weigh in but instead refer the patient directly to the emergency department because of the risk that the symptoms may become irreversible and result in permanent blindness or deafness. “You don’t want to dilly-dally with those conditions,” Dr. Ghanem said.

Closely monitoring a patient’s rapid plasma regain and venereal disease research laboratory antigen levels is the only way to manage syphilis and to determine whether the infection is responding to treatment, he noted, but sometimes those titers “don’t do what you think they should be doing” and fail to decline or even go up after treatment.

“You don’t know if they went up because the patient was re-infected, or they developed neurosyphilis, or there was a problem at the lab,” he said. “It can be challenging to interpret.”

To decipher confusing test results, Dr. Ghanem recommended getting a detailed history to understand whether a patient is at risk for reinfection, whether there are signs of neurosyphilis or other complications, whether pregnancy is possible, and so on. “Based on the answers, you can determine what the most rational approach to treatment would be,” he shared.

Drug Shortages

Efforts to get the infection under control have become more complicated. Last summer, Pfizer announced that it had run out of penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin), an injectable, long-acting drug that is one of the main treatments for syphilis and the only one that can be given to pregnant people. Supplies for children ran out at the end of June 2023, and supplies for adults were gone by the end of September.

Because Pfizer is the only company that manufactures penicillin G benzathine, there is no one to pick up the slack in the short-term, so the shortage is expected to continue until at least the middle of 2024.

In response, the US Food and Drug Administration has temporarily allowed the use of benzylpenicillin benzathine (Extencilline), a French formulation that has not been approved in the United States, until supplies of penicillin G benzathine are stabilized.

The shortage has shone a spotlight on the important issue of a lack of alternatives for the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy, which increases the risk for congenital syphilis. “Hopefully, this pushes the National Institutes of Health and others to step up their game on studies for alternative drugs for use in pregnancy,” Dr. Ghanem said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With rates of syphilis rising quickly in the United States and elsewhere, clinicians are having to up their game when it comes to diagnosing and treating an infection that they may not be paying enough attention to.

More than 200,000 cases of syphilis were reported in the United States in 2022, which is the highest number since 1950 and is a 17.3% increase over 2021, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The rate of infection has increased almost every year since a historic low in 2001.

And the trend is not limited to the United States. Last year, the infection rate in the United Kingdom hit a 50-year high, said David Mabey, BCh, DM, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections are also a major problem in low- and middle-income countries, he added, although good data are not always available.

Many of today’s healthcare professionals have little experience with the disease, shared Ina Park, MD, a sexually transmitted infections specialist at the University of California at San Francisco. “An entire generation of physicians — including myself — did not see any cases until we were well out of our training,” Dr. Park reported. “We’re really playing catch-up.”

A Centuries-Old Ailment

Dr. Park offered some advice on the challenges of diagnosing what can be an elusive infection at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2024 Annual Meeting in Denver. That advice boiled down to one simple rule: “Test, test, test.”

Because syphilis can mimic so many other conditions and can have long periods of latency, it can be easily missed or even misdiagnosed by experienced physicians, said Dr. Park. Clinicians need to keep it front of mind and have a lower threshold for testing, even if there are no obvious symptoms.

Following the CDC’s new recommendations for syphilis screening will help, she noted; every sexually active patient aged between 15 and 44 years who lives in a county with a syphilis infection rate of 4.6 per 100,000 people or higher should get the test. And clinicians should remain vigilant, even in areas with a lower prevalence. “If you can’t account for new symptoms in a sexually active patient, order a test,” said Dr. Park.

Complicated Cases

The lack of experience with syphilis affects not just diagnosis but also treatment, particularly for complex cases, said Khalil Ghanem, MD, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “When you don’t have to deal with something for a while, you forget how to deal with it,” he added.

At CROI, Dr. Ghanem offered suggestions for how to navigate complicated cases of ocular syphilis, otic syphilis, and neurosyphilis, and how to interpret test results when a patient’s antigen titers are being “unruly.”

With potential ocular or otic syphilis, you shouldn’t wait for a specialist like an ophthalmologist to weigh in but instead refer the patient directly to the emergency department because of the risk that the symptoms may become irreversible and result in permanent blindness or deafness. “You don’t want to dilly-dally with those conditions,” Dr. Ghanem said.

Closely monitoring a patient’s rapid plasma regain and venereal disease research laboratory antigen levels is the only way to manage syphilis and to determine whether the infection is responding to treatment, he noted, but sometimes those titers “don’t do what you think they should be doing” and fail to decline or even go up after treatment.

“You don’t know if they went up because the patient was re-infected, or they developed neurosyphilis, or there was a problem at the lab,” he said. “It can be challenging to interpret.”

To decipher confusing test results, Dr. Ghanem recommended getting a detailed history to understand whether a patient is at risk for reinfection, whether there are signs of neurosyphilis or other complications, whether pregnancy is possible, and so on. “Based on the answers, you can determine what the most rational approach to treatment would be,” he shared.

Drug Shortages

Efforts to get the infection under control have become more complicated. Last summer, Pfizer announced that it had run out of penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin), an injectable, long-acting drug that is one of the main treatments for syphilis and the only one that can be given to pregnant people. Supplies for children ran out at the end of June 2023, and supplies for adults were gone by the end of September.

Because Pfizer is the only company that manufactures penicillin G benzathine, there is no one to pick up the slack in the short-term, so the shortage is expected to continue until at least the middle of 2024.

In response, the US Food and Drug Administration has temporarily allowed the use of benzylpenicillin benzathine (Extencilline), a French formulation that has not been approved in the United States, until supplies of penicillin G benzathine are stabilized.

The shortage has shone a spotlight on the important issue of a lack of alternatives for the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy, which increases the risk for congenital syphilis. “Hopefully, this pushes the National Institutes of Health and others to step up their game on studies for alternative drugs for use in pregnancy,” Dr. Ghanem said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New Infant RSV Antibody Treatment Shows Strong Results

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Timing the New Meningitis Shots Serogroup Top 5’s

The first pentavalent vaccine approved against all five major serogroups of meningococcal disease has clinicians evaluating the optimal timing for vaccination, according to a new analysis.

Vaccines have helped greatly reduce the rate of invasive meningococcal disease among adolescents over the past 20 years, and the new formulation that covers all main types of the bacteria could help improve vaccination coverage and drive infection rates even lower, reported the research led by senior author Gregory Zimet from the department of pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The five main serogroups — labeled A, B, C, W, and Y — cause most of the disease set off by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis. It is a rare but serious illness that mostly affects adolescents and young adults.

Meningitis often presents with nonspecific symptoms and can progress to serious illness and even death within hours.

“Clinical features of invasive meningococcal disease, coupled with its unpredictable epidemiology, suggest that vaccination is the best strategy for preventing associated adverse outcomes,” the researchers reported.

Before the introduction of vaccines in 2005, the incidence of disease in the United States ranged from 0.5 to 1.1 cases per 100,000 people, with ≥ 10% of cases being fatal.

The Quadrivalent Vaccine

In 2005, the first quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, covering serogroups A, C, W, and Y, was approved in the United States and recommended for routine use in 11- and 12-year-olds, followed by a 2010 booster recommendation at age 16 years.

Between 2006 and 2017, the estimated incidence among 11- to 15-year-olds dropped by > 26% each year.

For those aged 16-22 years, the incidence dropped even further by > 35% per year between 2011 and 2017 after the booster was introduced.

Rates also fell in other groups that had not been vaccinated, such as in infants and adults, suggesting possible herd protection after the vaccines.

With Serogroup B

By 2015, a vaccine covering serogroup B was also approved. However, it was not added to the routine vaccination schedule and was subject to shared clinical decision-making between clinicians and patients.

The B vaccine has been less successful, reported the researchers, who said this is likely because uptake was much lower due to it not being part of the routine schedule.

Today, serogroup B makes up a greater proportion of meningitis cases. Before the vaccines were introduced, it accounted for about one third of cases, and now it is the cause of about half of all cases.

Two Doses With a Boost?

In October, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first pentavalent vaccine against all five major serogroups, which the authors of the analysis said, “may help optimize the existing US adolescent meningococcal vaccination platform”.

A modeling study suggested that the current vaccination schedule of two doses each of the vaccines would prevent 165 cases of meningitis over 10 years. However, a two-dose pentavalent vaccine at age 11 years plus a booster at age 16 years would not only simplify the process and reduce the number of injections required but would also increase the number of cases prevented to 256.

“Use of pentavalent vaccines yields the potential to build on the success of the incumbent program, raising B vaccination coverage by simplifying existing recommendations and decreasing the number of injections required,” the researchers reported, thus “…reducing the clinical and economic burden of meningococcal disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The first pentavalent vaccine approved against all five major serogroups of meningococcal disease has clinicians evaluating the optimal timing for vaccination, according to a new analysis.

Vaccines have helped greatly reduce the rate of invasive meningococcal disease among adolescents over the past 20 years, and the new formulation that covers all main types of the bacteria could help improve vaccination coverage and drive infection rates even lower, reported the research led by senior author Gregory Zimet from the department of pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The five main serogroups — labeled A, B, C, W, and Y — cause most of the disease set off by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis. It is a rare but serious illness that mostly affects adolescents and young adults.

Meningitis often presents with nonspecific symptoms and can progress to serious illness and even death within hours.

“Clinical features of invasive meningococcal disease, coupled with its unpredictable epidemiology, suggest that vaccination is the best strategy for preventing associated adverse outcomes,” the researchers reported.

Before the introduction of vaccines in 2005, the incidence of disease in the United States ranged from 0.5 to 1.1 cases per 100,000 people, with ≥ 10% of cases being fatal.

The Quadrivalent Vaccine

In 2005, the first quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, covering serogroups A, C, W, and Y, was approved in the United States and recommended for routine use in 11- and 12-year-olds, followed by a 2010 booster recommendation at age 16 years.

Between 2006 and 2017, the estimated incidence among 11- to 15-year-olds dropped by > 26% each year.

For those aged 16-22 years, the incidence dropped even further by > 35% per year between 2011 and 2017 after the booster was introduced.

Rates also fell in other groups that had not been vaccinated, such as in infants and adults, suggesting possible herd protection after the vaccines.

With Serogroup B

By 2015, a vaccine covering serogroup B was also approved. However, it was not added to the routine vaccination schedule and was subject to shared clinical decision-making between clinicians and patients.

The B vaccine has been less successful, reported the researchers, who said this is likely because uptake was much lower due to it not being part of the routine schedule.

Today, serogroup B makes up a greater proportion of meningitis cases. Before the vaccines were introduced, it accounted for about one third of cases, and now it is the cause of about half of all cases.

Two Doses With a Boost?

In October, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first pentavalent vaccine against all five major serogroups, which the authors of the analysis said, “may help optimize the existing US adolescent meningococcal vaccination platform”.

A modeling study suggested that the current vaccination schedule of two doses each of the vaccines would prevent 165 cases of meningitis over 10 years. However, a two-dose pentavalent vaccine at age 11 years plus a booster at age 16 years would not only simplify the process and reduce the number of injections required but would also increase the number of cases prevented to 256.

“Use of pentavalent vaccines yields the potential to build on the success of the incumbent program, raising B vaccination coverage by simplifying existing recommendations and decreasing the number of injections required,” the researchers reported, thus “…reducing the clinical and economic burden of meningococcal disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The first pentavalent vaccine approved against all five major serogroups of meningococcal disease has clinicians evaluating the optimal timing for vaccination, according to a new analysis.

Vaccines have helped greatly reduce the rate of invasive meningococcal disease among adolescents over the past 20 years, and the new formulation that covers all main types of the bacteria could help improve vaccination coverage and drive infection rates even lower, reported the research led by senior author Gregory Zimet from the department of pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The five main serogroups — labeled A, B, C, W, and Y — cause most of the disease set off by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis. It is a rare but serious illness that mostly affects adolescents and young adults.

Meningitis often presents with nonspecific symptoms and can progress to serious illness and even death within hours.

“Clinical features of invasive meningococcal disease, coupled with its unpredictable epidemiology, suggest that vaccination is the best strategy for preventing associated adverse outcomes,” the researchers reported.

Before the introduction of vaccines in 2005, the incidence of disease in the United States ranged from 0.5 to 1.1 cases per 100,000 people, with ≥ 10% of cases being fatal.

The Quadrivalent Vaccine

In 2005, the first quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, covering serogroups A, C, W, and Y, was approved in the United States and recommended for routine use in 11- and 12-year-olds, followed by a 2010 booster recommendation at age 16 years.

Between 2006 and 2017, the estimated incidence among 11- to 15-year-olds dropped by > 26% each year.

For those aged 16-22 years, the incidence dropped even further by > 35% per year between 2011 and 2017 after the booster was introduced.

Rates also fell in other groups that had not been vaccinated, such as in infants and adults, suggesting possible herd protection after the vaccines.

With Serogroup B

By 2015, a vaccine covering serogroup B was also approved. However, it was not added to the routine vaccination schedule and was subject to shared clinical decision-making between clinicians and patients.

The B vaccine has been less successful, reported the researchers, who said this is likely because uptake was much lower due to it not being part of the routine schedule.

Today, serogroup B makes up a greater proportion of meningitis cases. Before the vaccines were introduced, it accounted for about one third of cases, and now it is the cause of about half of all cases.

Two Doses With a Boost?

In October, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first pentavalent vaccine against all five major serogroups, which the authors of the analysis said, “may help optimize the existing US adolescent meningococcal vaccination platform”.

A modeling study suggested that the current vaccination schedule of two doses each of the vaccines would prevent 165 cases of meningitis over 10 years. However, a two-dose pentavalent vaccine at age 11 years plus a booster at age 16 years would not only simplify the process and reduce the number of injections required but would also increase the number of cases prevented to 256.

“Use of pentavalent vaccines yields the potential to build on the success of the incumbent program, raising B vaccination coverage by simplifying existing recommendations and decreasing the number of injections required,” the researchers reported, thus “…reducing the clinical and economic burden of meningococcal disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk for Preterm Birth Stops Maternal RSV Vaccine Trial

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

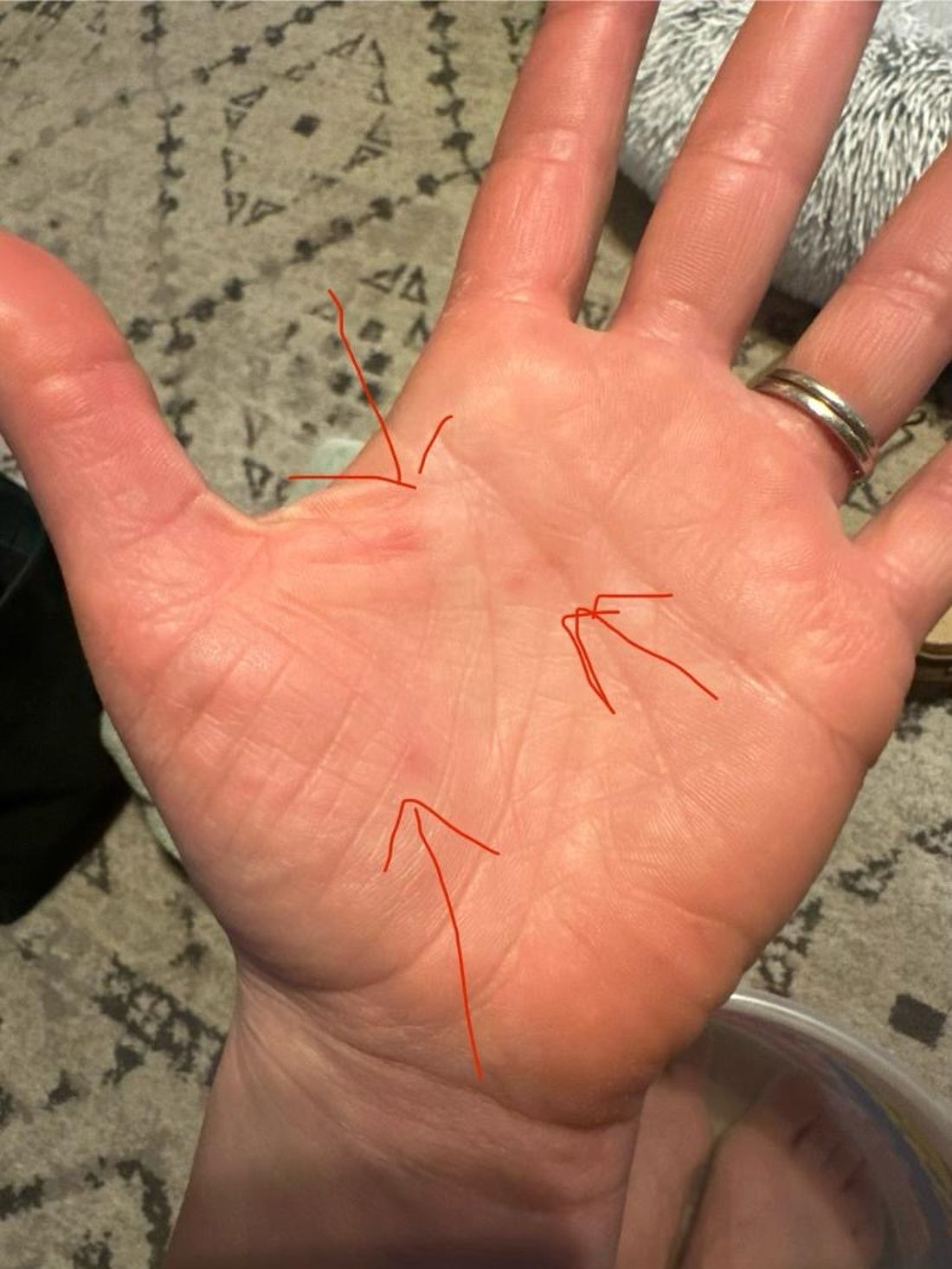

A 35-year-old female presented with a 1-day history of eroded papules and vesicles distributed periorally

.1 While it predominantly affects children, it is important to note that it can also affect adults. Although it is not a life threatening infection, it can cause a painful rash and is highly contagious. The infection is easily spread in multiple ways, including via respiratory droplets, contact with vesicular or nasal secretions, or through fecal-oral transmission. Most cases occur during the summer and fall seasons but individuals can be infected at any time of the year.

HFMD typically starts with a few days of non-specific viral symptoms, such as fever, cough, sore throat, and fatigue. It is then followed by an eruption of intraoral macules and vesicles and a widespread distribution of oval shaped macules that predominantly involve the hands and feet.1 Both children and adults can present atypically. Atypical presentations include vesicles and bullae on extensor surfaces such as the forearms, as well as eruptions on the face or buttocks.2 Other atypical morphologies include eczema herpeticum-like, Gianotti-Crosti-like, and purpuric/petechiae.3 Atypical hand, food, and mouth disease cases are often caused by coxsackievirus A6, however other strains of coxsackievirus can also cause atypical symptoms.2,3

Our 35-year-old female patient presented with eroded papules and vesicles around the mouth. A diagnosis of atypical HFMD was made clinically in the following days when the patient developed the more classic intraoral and acral macules and vesicles.

Similar to our case, HFMD is most often diagnosed clinically. PCR testing from an active vesicle or nasopharyngeal swab can be obtained. Treatment for HFMD is supportive and symptoms generally resolve over 7-10 days. Over-the-counter analgesics, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen, as well as oral analgesics that contain lidocaine or diphenhydramine are often helpful3. In this case, our patient improved over the course of seven days without needing therapy.

This case and the photos were submitted by Vanessa Ortega, BS, University of California, San Diego; Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, and Justin Gordon, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 20). Symptoms of hand, foot, and mouth disease.

2. Drago F et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug;77(2):e51-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.046.

3. Starkey SY et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Jan-Feb;41(1):23-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15461.

.1 While it predominantly affects children, it is important to note that it can also affect adults. Although it is not a life threatening infection, it can cause a painful rash and is highly contagious. The infection is easily spread in multiple ways, including via respiratory droplets, contact with vesicular or nasal secretions, or through fecal-oral transmission. Most cases occur during the summer and fall seasons but individuals can be infected at any time of the year.

HFMD typically starts with a few days of non-specific viral symptoms, such as fever, cough, sore throat, and fatigue. It is then followed by an eruption of intraoral macules and vesicles and a widespread distribution of oval shaped macules that predominantly involve the hands and feet.1 Both children and adults can present atypically. Atypical presentations include vesicles and bullae on extensor surfaces such as the forearms, as well as eruptions on the face or buttocks.2 Other atypical morphologies include eczema herpeticum-like, Gianotti-Crosti-like, and purpuric/petechiae.3 Atypical hand, food, and mouth disease cases are often caused by coxsackievirus A6, however other strains of coxsackievirus can also cause atypical symptoms.2,3

Our 35-year-old female patient presented with eroded papules and vesicles around the mouth. A diagnosis of atypical HFMD was made clinically in the following days when the patient developed the more classic intraoral and acral macules and vesicles.

Similar to our case, HFMD is most often diagnosed clinically. PCR testing from an active vesicle or nasopharyngeal swab can be obtained. Treatment for HFMD is supportive and symptoms generally resolve over 7-10 days. Over-the-counter analgesics, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen, as well as oral analgesics that contain lidocaine or diphenhydramine are often helpful3. In this case, our patient improved over the course of seven days without needing therapy.

This case and the photos were submitted by Vanessa Ortega, BS, University of California, San Diego; Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, and Justin Gordon, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 20). Symptoms of hand, foot, and mouth disease.

2. Drago F et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug;77(2):e51-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.046.

3. Starkey SY et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Jan-Feb;41(1):23-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15461.

.1 While it predominantly affects children, it is important to note that it can also affect adults. Although it is not a life threatening infection, it can cause a painful rash and is highly contagious. The infection is easily spread in multiple ways, including via respiratory droplets, contact with vesicular or nasal secretions, or through fecal-oral transmission. Most cases occur during the summer and fall seasons but individuals can be infected at any time of the year.

HFMD typically starts with a few days of non-specific viral symptoms, such as fever, cough, sore throat, and fatigue. It is then followed by an eruption of intraoral macules and vesicles and a widespread distribution of oval shaped macules that predominantly involve the hands and feet.1 Both children and adults can present atypically. Atypical presentations include vesicles and bullae on extensor surfaces such as the forearms, as well as eruptions on the face or buttocks.2 Other atypical morphologies include eczema herpeticum-like, Gianotti-Crosti-like, and purpuric/petechiae.3 Atypical hand, food, and mouth disease cases are often caused by coxsackievirus A6, however other strains of coxsackievirus can also cause atypical symptoms.2,3

Our 35-year-old female patient presented with eroded papules and vesicles around the mouth. A diagnosis of atypical HFMD was made clinically in the following days when the patient developed the more classic intraoral and acral macules and vesicles.

Similar to our case, HFMD is most often diagnosed clinically. PCR testing from an active vesicle or nasopharyngeal swab can be obtained. Treatment for HFMD is supportive and symptoms generally resolve over 7-10 days. Over-the-counter analgesics, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen, as well as oral analgesics that contain lidocaine or diphenhydramine are often helpful3. In this case, our patient improved over the course of seven days without needing therapy.

This case and the photos were submitted by Vanessa Ortega, BS, University of California, San Diego; Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, and Justin Gordon, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 20). Symptoms of hand, foot, and mouth disease.

2. Drago F et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug;77(2):e51-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.046.

3. Starkey SY et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Jan-Feb;41(1):23-7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15461.

Can AI Tool Improve Dx of Ear Infections?

TOPLINE:

Researchers have developed a tool that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to identify acute otitis media in children based on otoscopic videos. It may improve diagnosis of ear infections in primary care settings, the developers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- The developers relied on otoscopic videos of the tympanic membrane captured on smartphones connected to scopes.

- Their analysis focused on 1151 videos from 635 children, most younger than 3 years old, who were seen for sick or well visits at outpatient clinics in Pennsylvania from 2018 to 2023.

- The tool was trained to differentiate between patients who did and did not have acute otitis media.

TAKEAWAY:

- Out of an original pool of 1561 videos, 410 were excluded due to obstruction by cerumen. In the remaining videos, experts identified acute otitis media in 305 videos (26.5%) and no acute otitis media in 846 videos (73.5%).

- The tool achieved a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 93.5%, with bulging of the tympanic membrane being the most indicative feature of acute otitis media, present in 100% of diagnosed cases, according to the researchers.

- Feedback from 60 parents was largely positive, with 80% wanting the tool to be used during future visits.

IN PRACTICE:

Based on the diagnostic accuracy of clinicians in other studies, “The algorithm exhibited higher accuracy than pediatricians, primary care physicians, and advance practice clinicians and, accordingly, could reasonably be used in these settings to aid with decisions regarding treatment,” the authors of the study wrote. “More accurate diagnosis of [acute otitis media] may help reduce unnecessary prescriptions of antimicrobials in young children,” they added.

Studies directly comparing the performance of the tool vs clinicians are still needed, however, according to an editorial accompanying the journal article.

“While the data from this study show the model’s accuracy (94%) is superior to historical accuracy of clinicians in diagnosing acute otitis media (84% or less), these data come from different studies not using the same definition for accuracy,” wrote Hojjat Salmasian, MD, MPH, PhD, and Lisa Biggs, MD, with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. “If we assume the model is confirmed to be highly accurate and free from bias, this model could truly transform care for patients with suspected acute otitis media.”

SOURCE:

Alejandro Hoberman, MD, with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was the corresponding author of the study. It was published online in JAMA Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The study used convenience sampling and did not include external validation of the tool. The researchers lacked information about participant demographics and the reason for their clinic visit.

DISCLOSURES:

Three authors of the study are listed as inventors on a patent for a tool to diagnose acute otitis media. Two authors with Dcipher Analytics disclosed fees from the University of Pittsburgh for their work on an application programming interface during the study. The research was supported by the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Researchers have developed a tool that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to identify acute otitis media in children based on otoscopic videos. It may improve diagnosis of ear infections in primary care settings, the developers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- The developers relied on otoscopic videos of the tympanic membrane captured on smartphones connected to scopes.

- Their analysis focused on 1151 videos from 635 children, most younger than 3 years old, who were seen for sick or well visits at outpatient clinics in Pennsylvania from 2018 to 2023.

- The tool was trained to differentiate between patients who did and did not have acute otitis media.

TAKEAWAY:

- Out of an original pool of 1561 videos, 410 were excluded due to obstruction by cerumen. In the remaining videos, experts identified acute otitis media in 305 videos (26.5%) and no acute otitis media in 846 videos (73.5%).

- The tool achieved a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 93.5%, with bulging of the tympanic membrane being the most indicative feature of acute otitis media, present in 100% of diagnosed cases, according to the researchers.

- Feedback from 60 parents was largely positive, with 80% wanting the tool to be used during future visits.

IN PRACTICE:

Based on the diagnostic accuracy of clinicians in other studies, “The algorithm exhibited higher accuracy than pediatricians, primary care physicians, and advance practice clinicians and, accordingly, could reasonably be used in these settings to aid with decisions regarding treatment,” the authors of the study wrote. “More accurate diagnosis of [acute otitis media] may help reduce unnecessary prescriptions of antimicrobials in young children,” they added.

Studies directly comparing the performance of the tool vs clinicians are still needed, however, according to an editorial accompanying the journal article.

“While the data from this study show the model’s accuracy (94%) is superior to historical accuracy of clinicians in diagnosing acute otitis media (84% or less), these data come from different studies not using the same definition for accuracy,” wrote Hojjat Salmasian, MD, MPH, PhD, and Lisa Biggs, MD, with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. “If we assume the model is confirmed to be highly accurate and free from bias, this model could truly transform care for patients with suspected acute otitis media.”

SOURCE:

Alejandro Hoberman, MD, with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was the corresponding author of the study. It was published online in JAMA Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The study used convenience sampling and did not include external validation of the tool. The researchers lacked information about participant demographics and the reason for their clinic visit.

DISCLOSURES:

Three authors of the study are listed as inventors on a patent for a tool to diagnose acute otitis media. Two authors with Dcipher Analytics disclosed fees from the University of Pittsburgh for their work on an application programming interface during the study. The research was supported by the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Researchers have developed a tool that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to identify acute otitis media in children based on otoscopic videos. It may improve diagnosis of ear infections in primary care settings, the developers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- The developers relied on otoscopic videos of the tympanic membrane captured on smartphones connected to scopes.

- Their analysis focused on 1151 videos from 635 children, most younger than 3 years old, who were seen for sick or well visits at outpatient clinics in Pennsylvania from 2018 to 2023.

- The tool was trained to differentiate between patients who did and did not have acute otitis media.

TAKEAWAY:

- Out of an original pool of 1561 videos, 410 were excluded due to obstruction by cerumen. In the remaining videos, experts identified acute otitis media in 305 videos (26.5%) and no acute otitis media in 846 videos (73.5%).

- The tool achieved a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 93.5%, with bulging of the tympanic membrane being the most indicative feature of acute otitis media, present in 100% of diagnosed cases, according to the researchers.

- Feedback from 60 parents was largely positive, with 80% wanting the tool to be used during future visits.

IN PRACTICE:

Based on the diagnostic accuracy of clinicians in other studies, “The algorithm exhibited higher accuracy than pediatricians, primary care physicians, and advance practice clinicians and, accordingly, could reasonably be used in these settings to aid with decisions regarding treatment,” the authors of the study wrote. “More accurate diagnosis of [acute otitis media] may help reduce unnecessary prescriptions of antimicrobials in young children,” they added.

Studies directly comparing the performance of the tool vs clinicians are still needed, however, according to an editorial accompanying the journal article.

“While the data from this study show the model’s accuracy (94%) is superior to historical accuracy of clinicians in diagnosing acute otitis media (84% or less), these data come from different studies not using the same definition for accuracy,” wrote Hojjat Salmasian, MD, MPH, PhD, and Lisa Biggs, MD, with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. “If we assume the model is confirmed to be highly accurate and free from bias, this model could truly transform care for patients with suspected acute otitis media.”

SOURCE:

Alejandro Hoberman, MD, with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was the corresponding author of the study. It was published online in JAMA Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The study used convenience sampling and did not include external validation of the tool. The researchers lacked information about participant demographics and the reason for their clinic visit.

DISCLOSURES:

Three authors of the study are listed as inventors on a patent for a tool to diagnose acute otitis media. Two authors with Dcipher Analytics disclosed fees from the University of Pittsburgh for their work on an application programming interface during the study. The research was supported by the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Skin Infections in Pregnant Women: Many Drugs Safe, but Not All

SAN DIEGO — . However, several drugs should be avoided or used with caution because of potential risks during pregnancy.

When treating bacterial infections in pregnant women, there are many options, “especially for the sort of short-term antibiotic use that we tend to use for treating infections,” said Jenny Murase, MD, of the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group and the University of California San Francisco.

During a presentation on treating infections in pregnant patients, she made the following recommendations for treating pyogenic infections:

- Impetigo: First-line treatments are topical mupirocin, oral first-generation cephalosporins, and oral dicloxacillin.

- Cellulitis: Recommended treatments are oral or intravenous penicillin, oral first-generation cephalosporins, and oral dicloxacillin.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): “Clindamycin is first-line, dependent on bacteria culture and sensitivities,” and because of its safety, “it’s a really good choice for a pregnant woman.” Dr. Murase said. However, be aware of potential inducible resistance and test for the erm gene, she said.

- Abscesses: Incision and drainage are recommended. “Whenever we’re managing a patient with a condition during pregnancy, we want to try to use nonmedications when possible,” Dr. Murase said. “No antibiotic is necessary unless the abscess is greater than 5 cm or if it’s greater than 2 cm with erythema around the abscess.”

- Tuberculosis: The best strategy is rifampin, but peripartum vitamin K prophylaxis for mother and fetus should be used, she said.

General Infections

With regard to antibiotics to treat general infections — for instance, if a patient with atopic dermatitis has a secondary skin infection — Dr. Murase recommended first-line oral antibiotic therapy with penicillin, first-generation cephalosporins, or dicloxacillin. For second-line therapy, erythromycin is the preferred macrolide over azithromycin and clarithromycin, she said.

She noted that there is an increased risk for atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis associated with the use of erythromycin when used during the first trimester of pregnancy. In addition, erythromycin estolate increases the risk of liver toxicity, while erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not.

Sulfonamides are a second-line line choice up until the third trimester. If given to a patient in the first trimester, she said, “make sure that they are supplementing with folic acid efficiently, at least 0.5 mg a day.” During the peripartum period they are contraindicated, as they pose a risk for hemolytic anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and kernicterus.

The combination drug trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is a second-line choice for complicated infections because of the associated risk for low birth weight and prematurity, Dr. Murase said.

Quinolones are also a second-line option during pregnancy she said, and ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin have been studied the most. “If you have to choose a quinolone for a complicated infection in pregnancy, those would be the quinolones of choice,” Dr. Murase said.

Considering the bad reputation of tetracyclines in pregnancy, dermatologists may be surprised to learn that they are considered a second-line therapy up to 14 weeks’ gestation, she said. After that time, however, they’re contraindicated because of bone growth inhibition, teeth discoloration, and maternal hepatitis.

Fungal Infections

As for fungal infections, clotrimazole is the first choice for topical treatment of tinea corporis, followed by miconazole and then ketoconazole, according to Dr. Murase. There are limited data for topical terbinafine, naftifine, and ciclopirox during pregnancy she noted, but they are likely safe.

There is also limited data about these drugs when used for topical treatment of candidiasis during pregnancy. Nystatin is safe, but less effective than other options, Dr. Murase said. Other options include clotrimazole, miconazole, and ketoconazole, which, in animals exposed to high doses, have not been associated with defects, and topical gentian violet (0.5%-1% solution), she noted.

For topical treatment of tinea versicolor during pregnancy, limited application of clotrimazole or miconazole is considered safe, and zinc pyrithione soap or topical benzoyl peroxide soap can be used for more widespread areas.

Dr. Murase recommended caution when using selenium sulfide since poisoning has been linked to miscarriages, she said. Limited application appears to be safe, “so make sure that the patient is using it on smaller body surface areas.”

As for systemic antifungal treatments, fluconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole should be avoided in pregnancy because of the risks of craniosynostosis, congenital heart defects, and skeletal anomalies, Dr. Murase said. However, she referred to a study that found no increased risk of congenital malformations with fluconazole during the first trimester, and a patient could be reassured if, for example, she was treated for a yeast infection before she knew she was pregnant, she said.

Griseofulvin is not recommended during pregnancy, but a 2020 study suggests that terbinafine is safe, she said. In that study, oral or topical terbinafine did not appear to be associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion or major malformations. “Certainly, we can wait until after the pregnancy to treat onychomycosis. But I have had situations that even in spite of regular topical therapy, pregnant patients needed to take some kind of oral agent” because of severe itching.

Viral Infections

For herpes simplex, acyclovir is the top choice, and famciclovir and valacyclovir (Valtrex) are likely safe, but daily prophylaxis is not recommended during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said.