User login

COVID-19 Is a Very Weird Virus

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

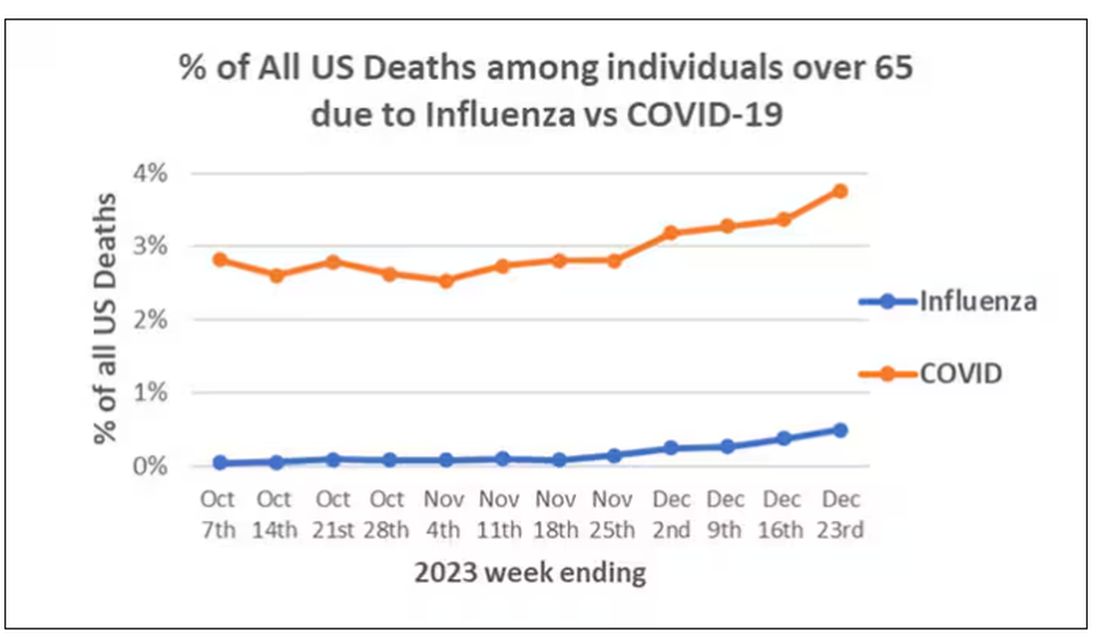

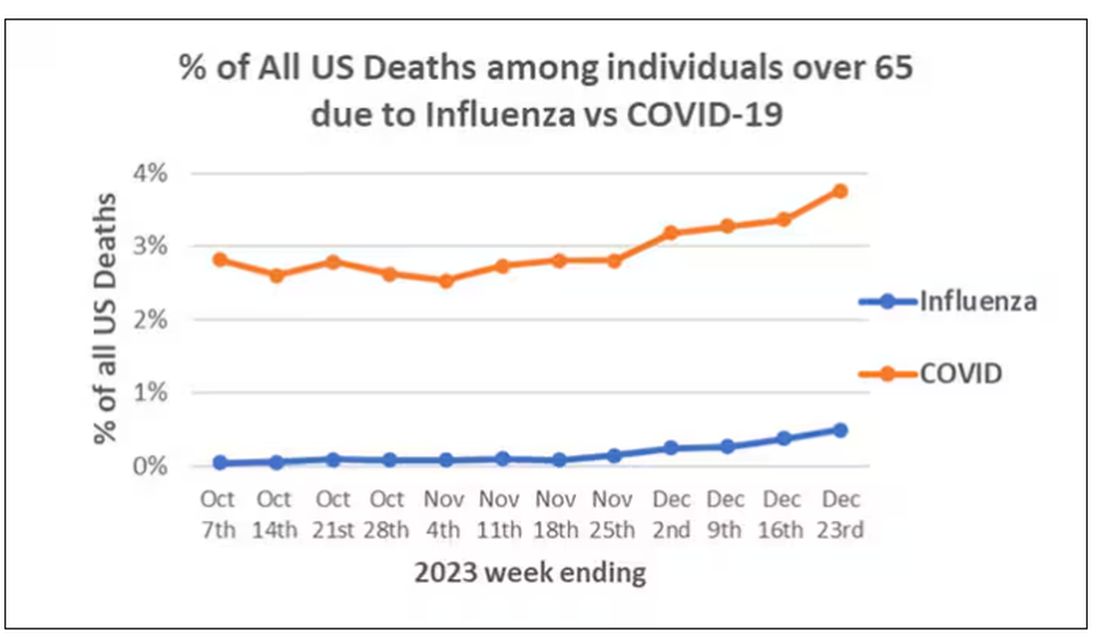

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

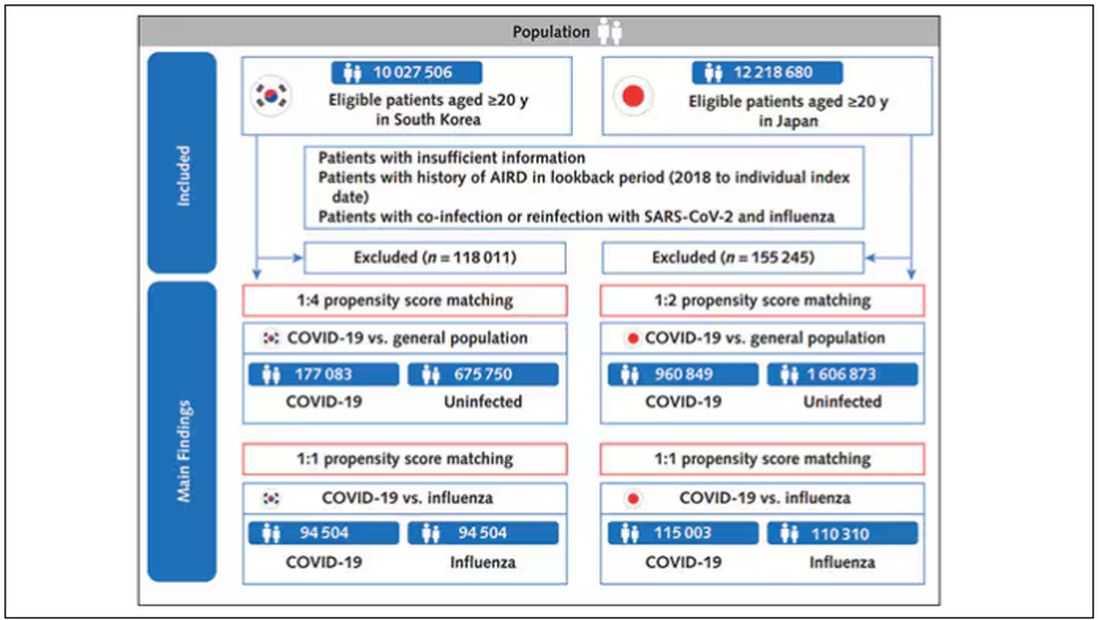

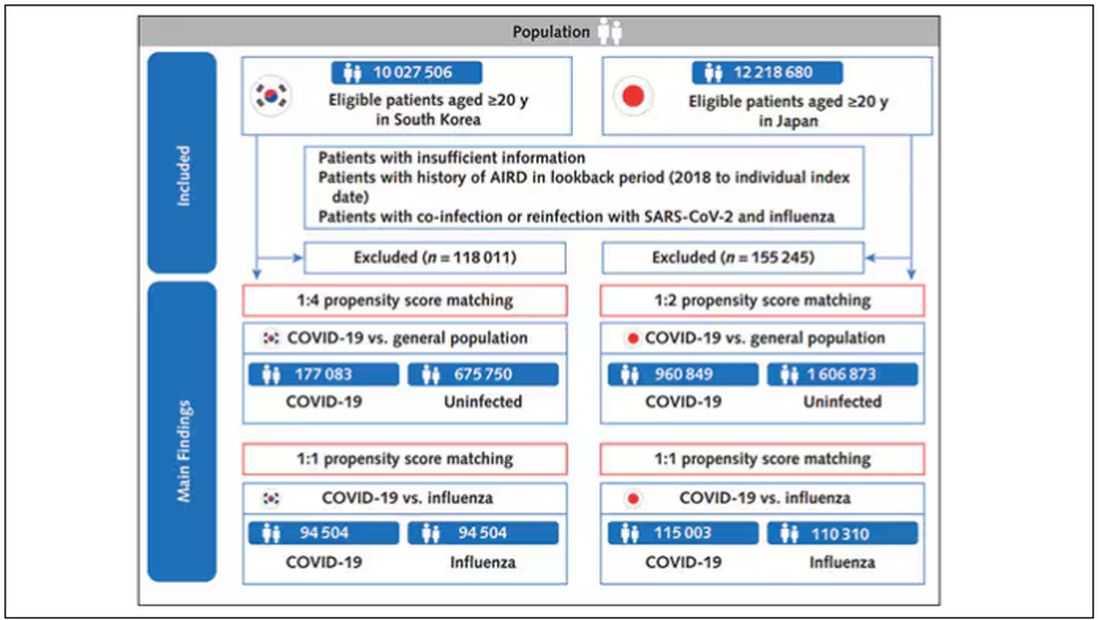

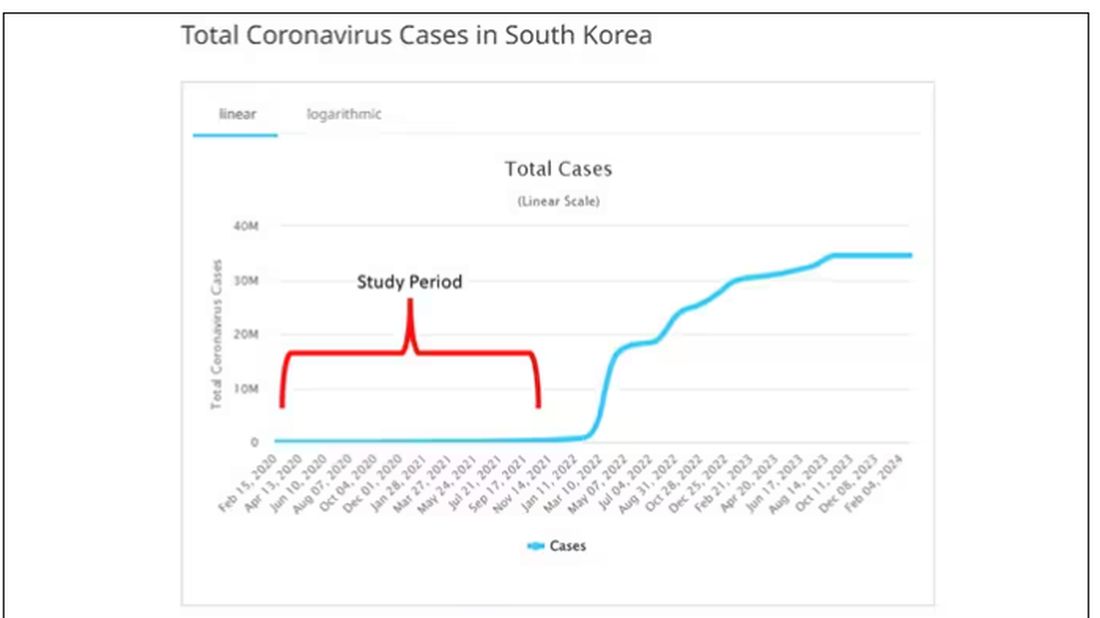

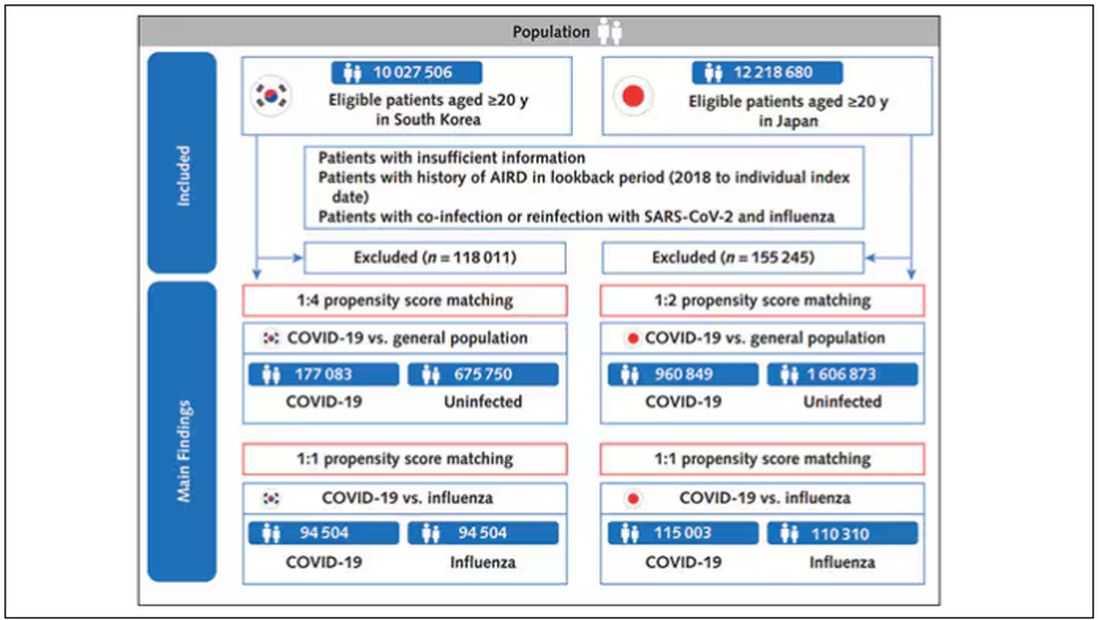

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

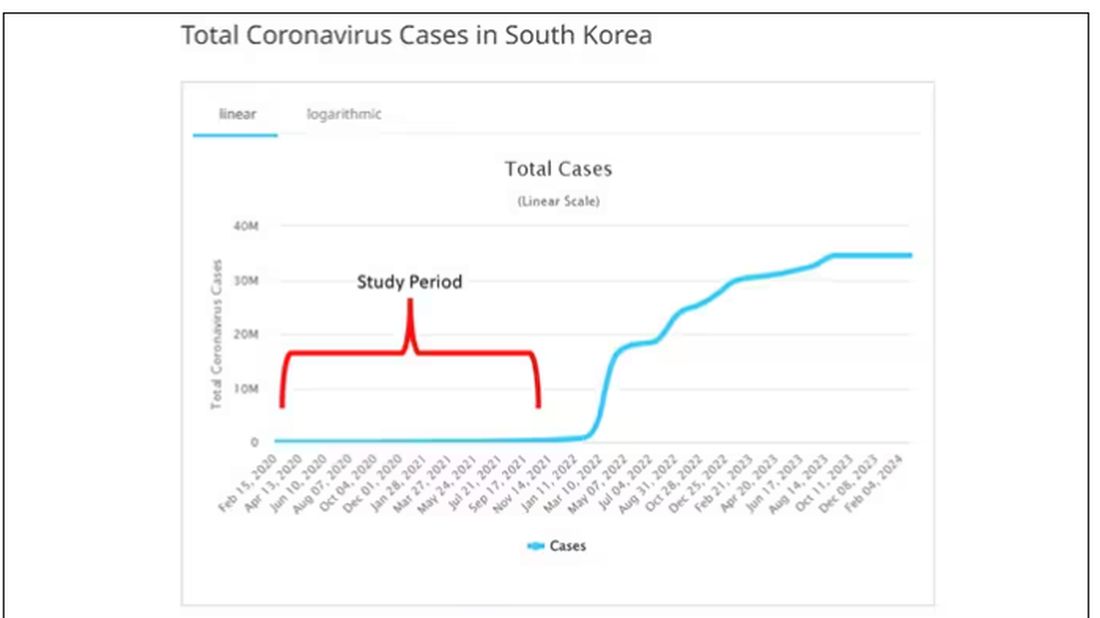

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

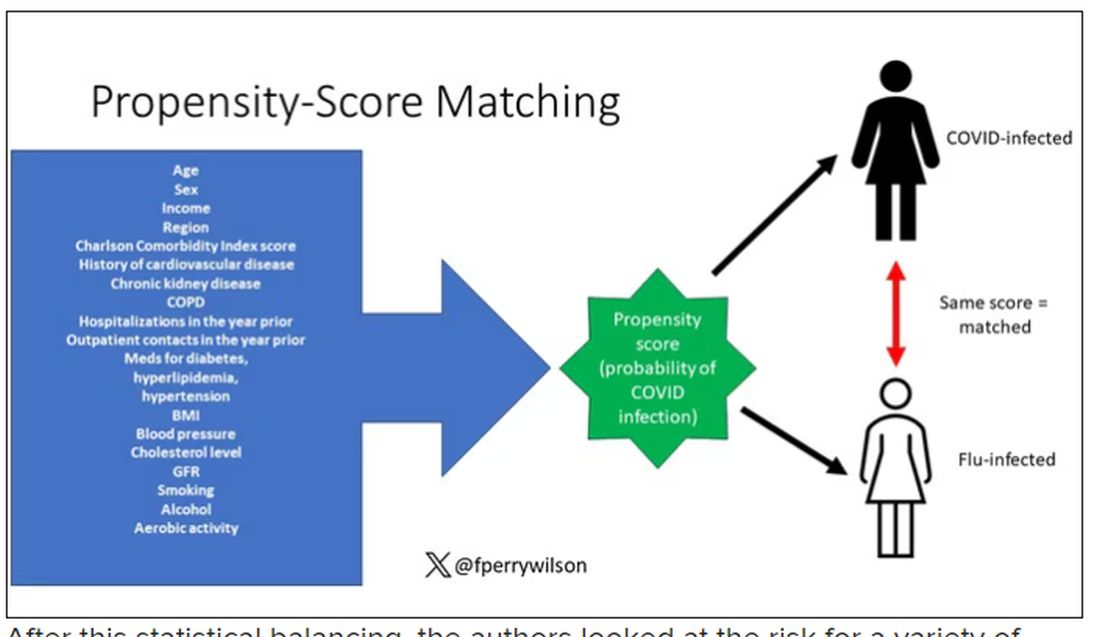

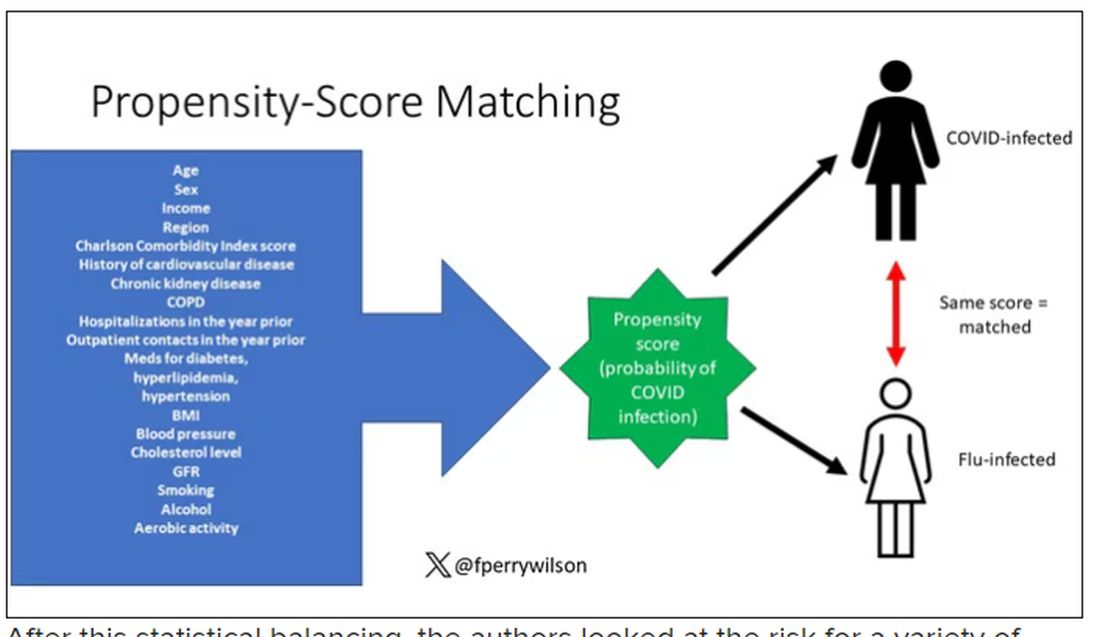

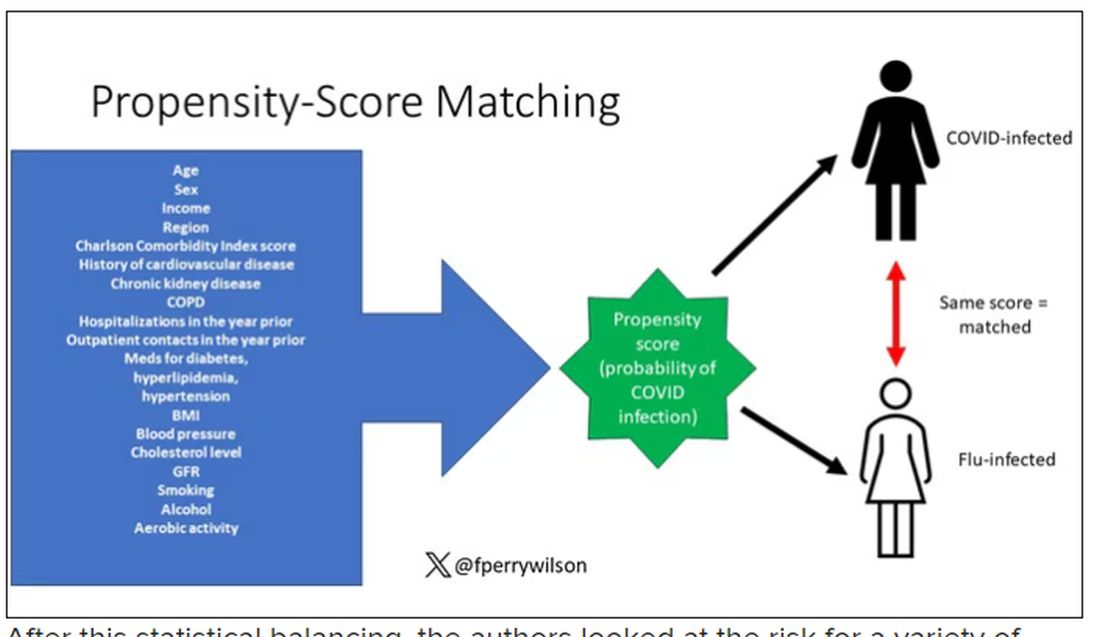

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

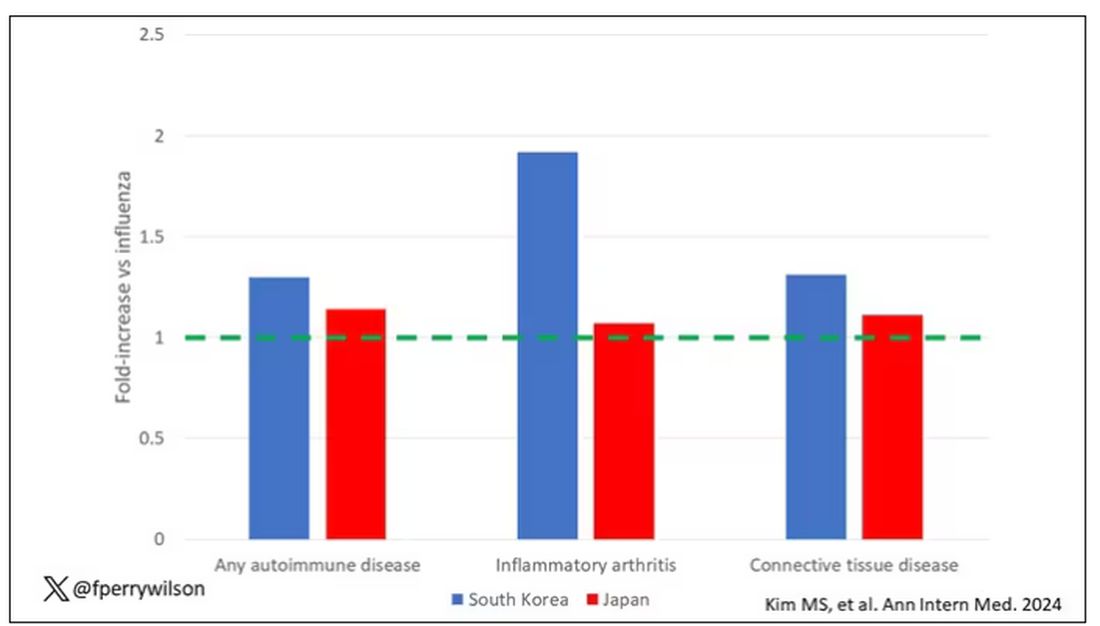

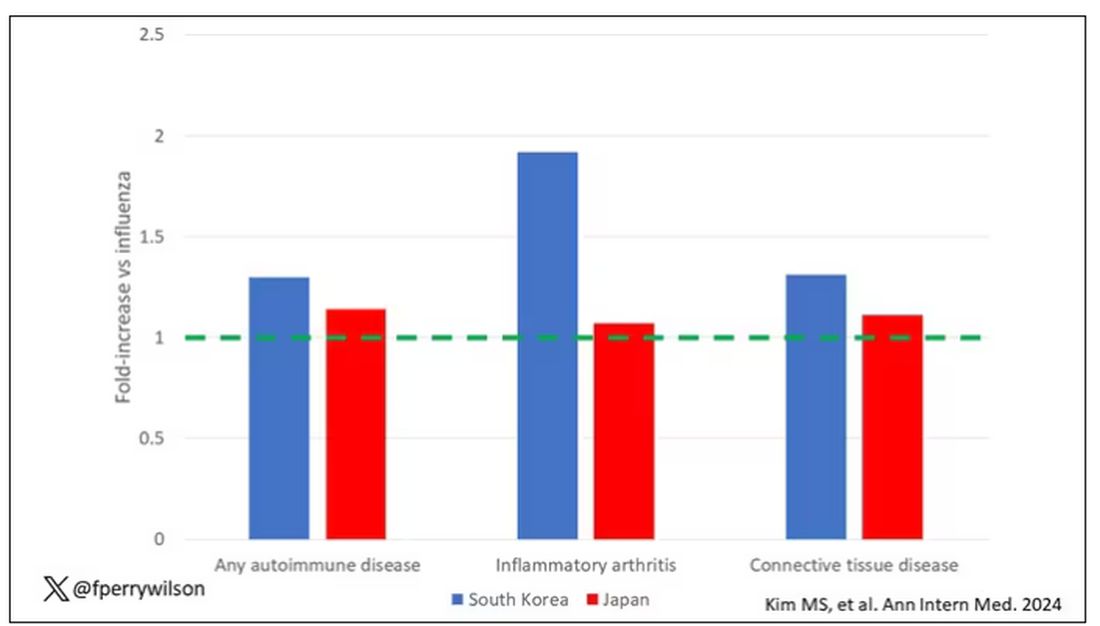

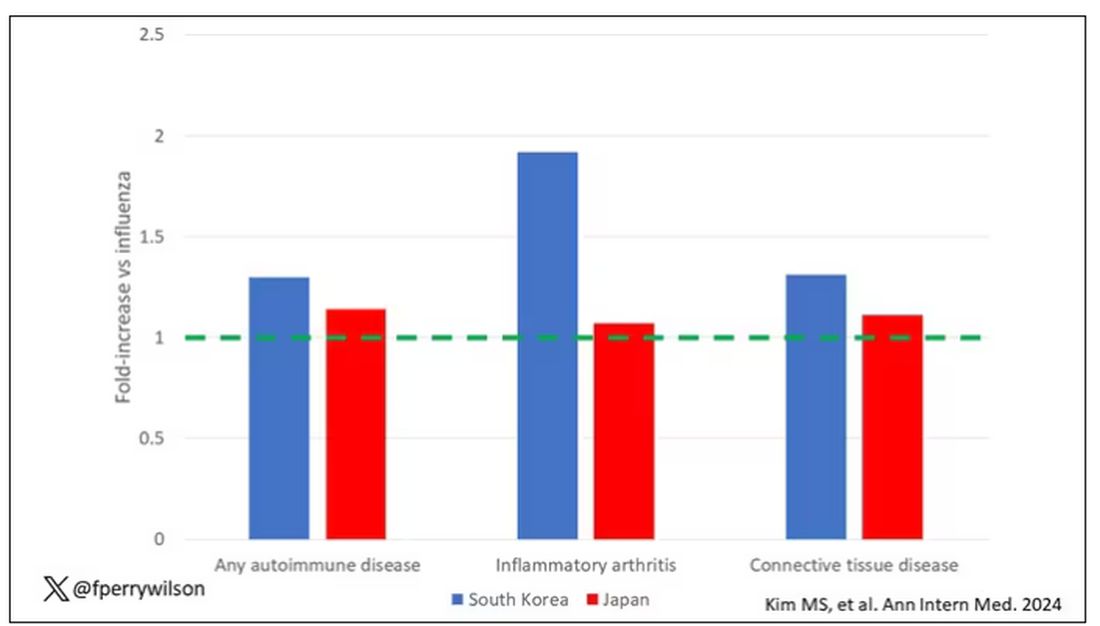

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

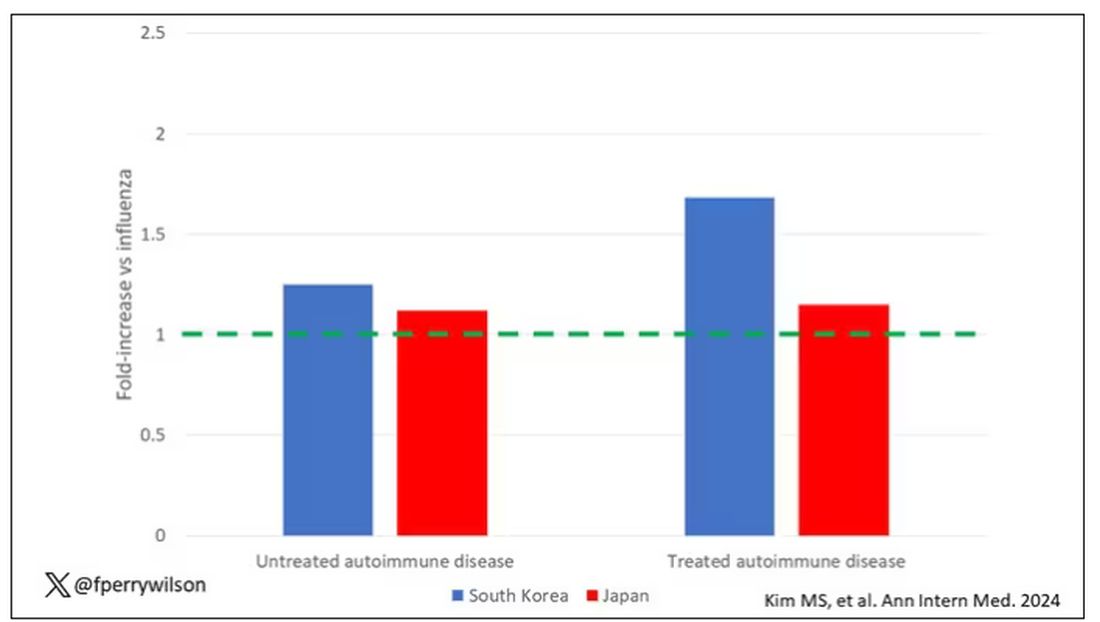

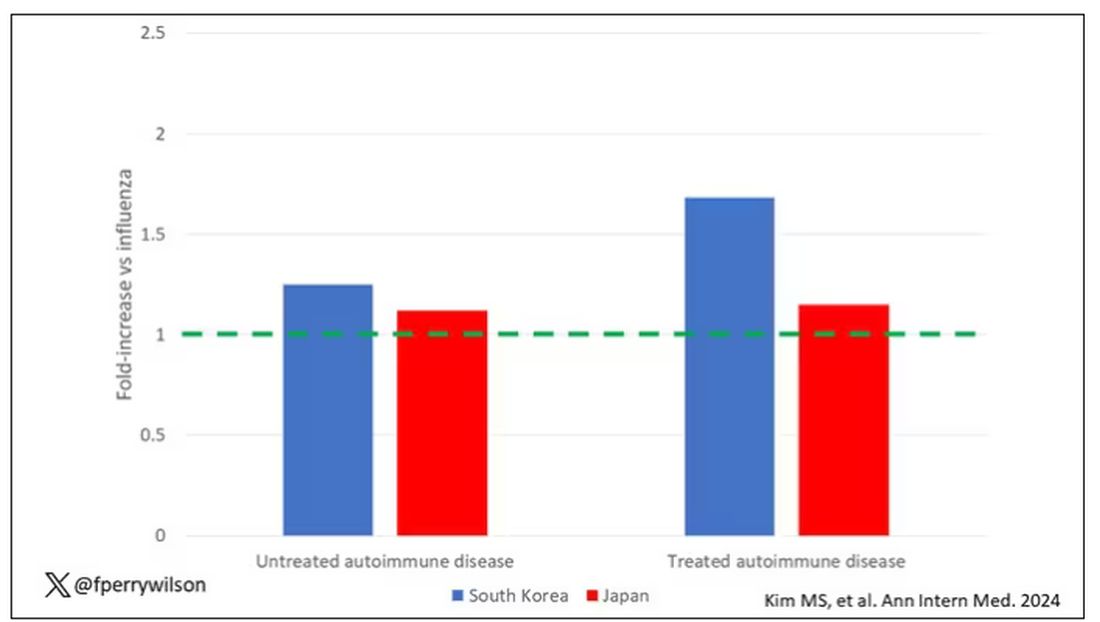

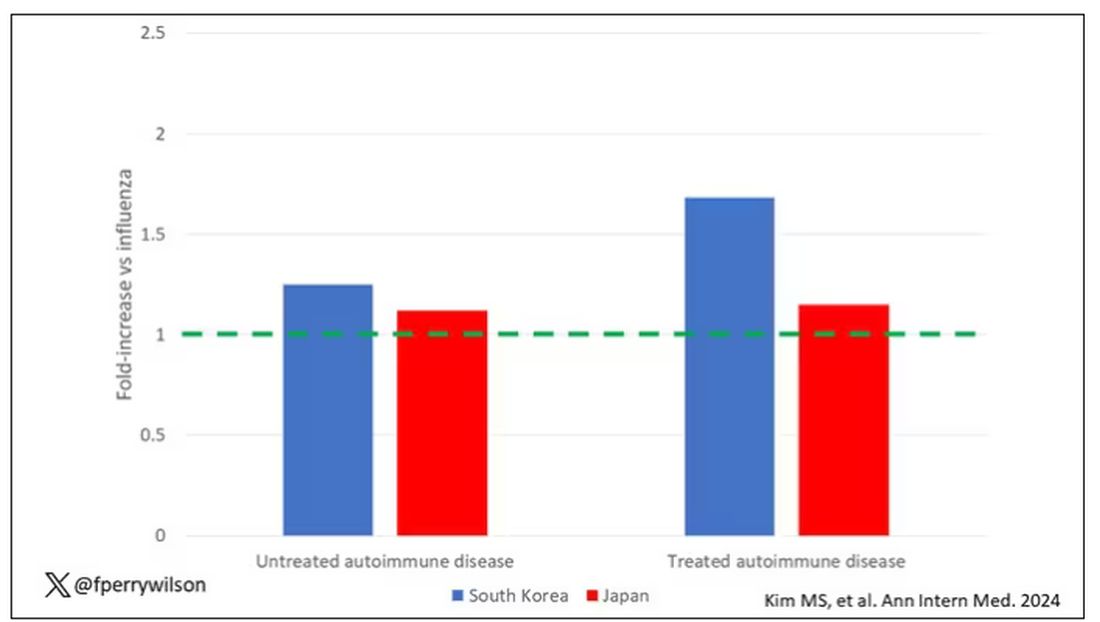

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

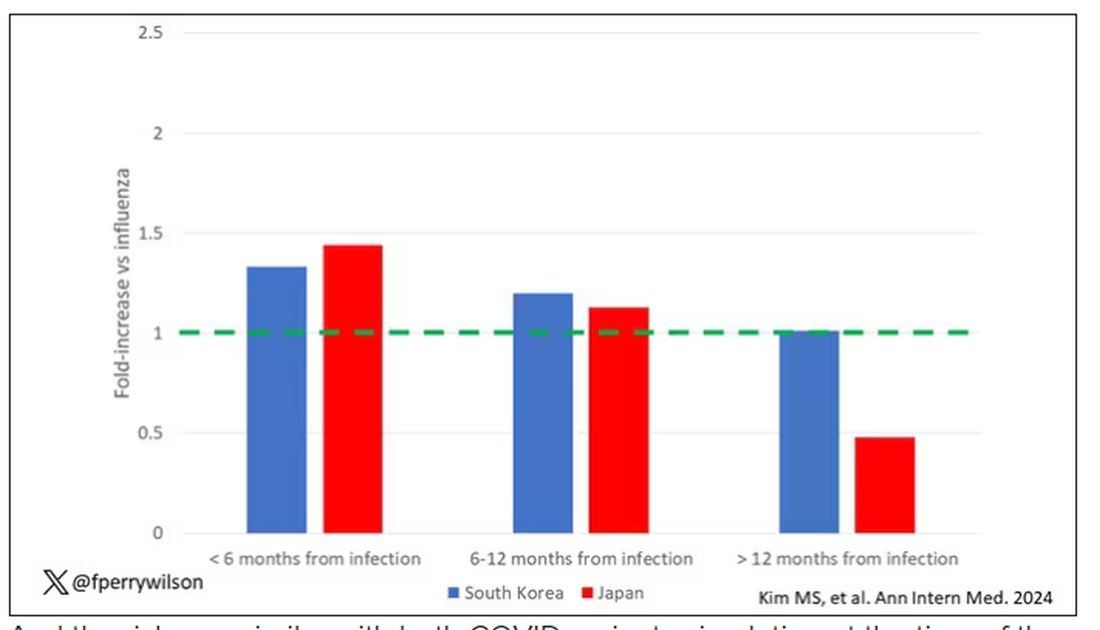

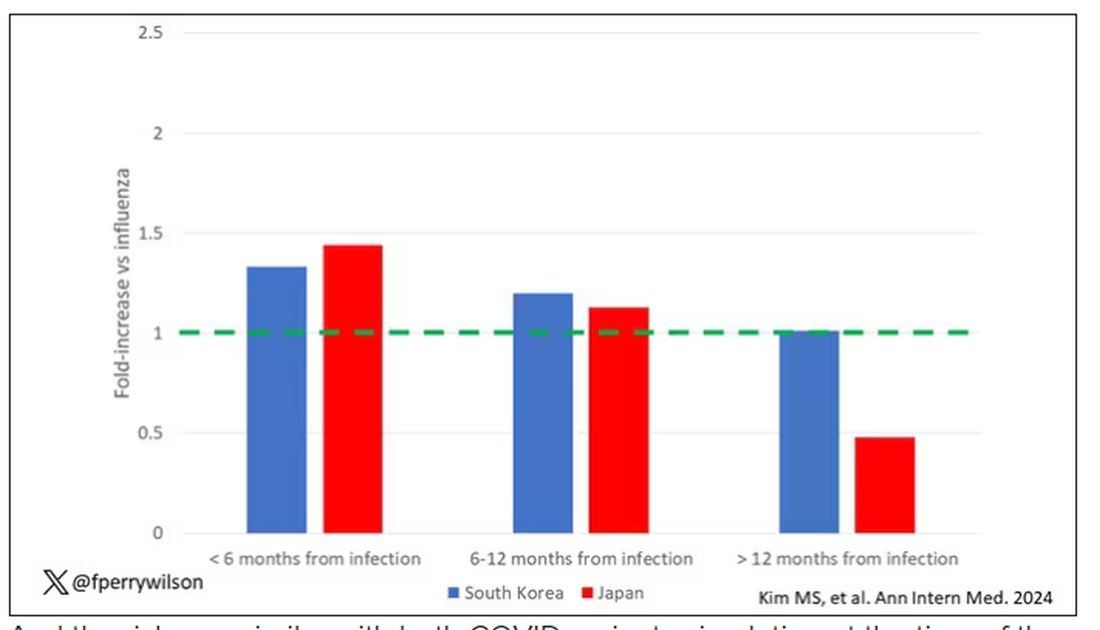

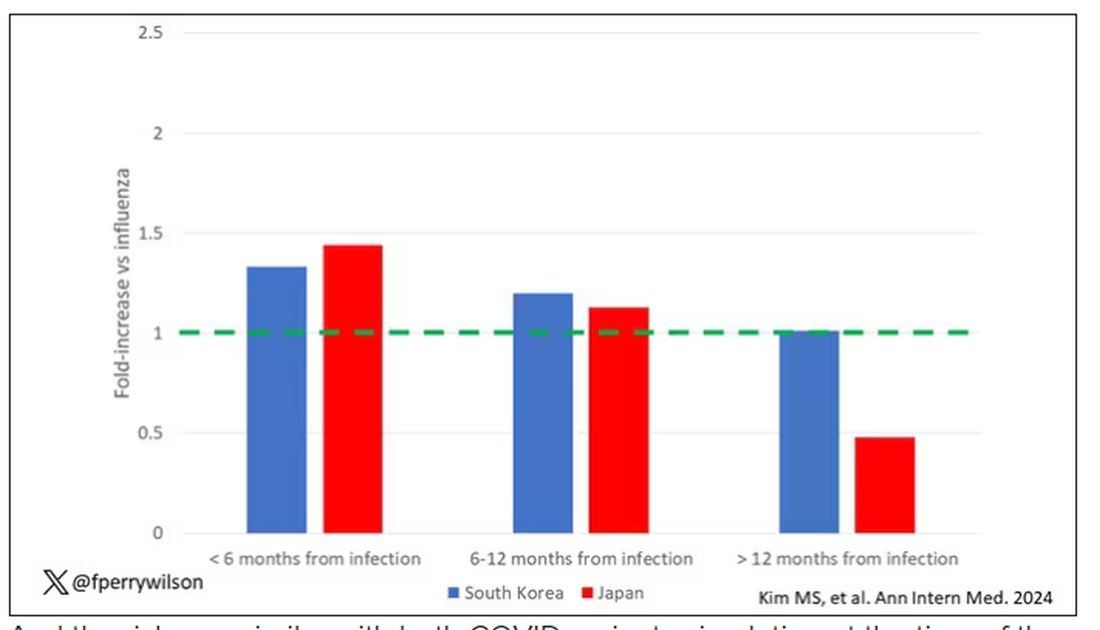

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

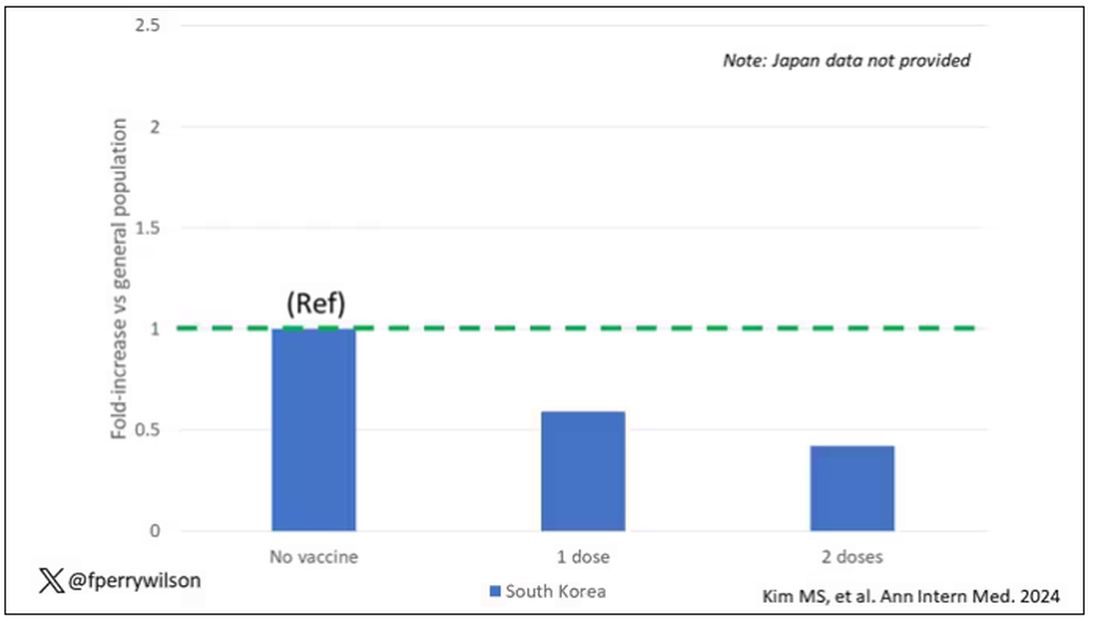

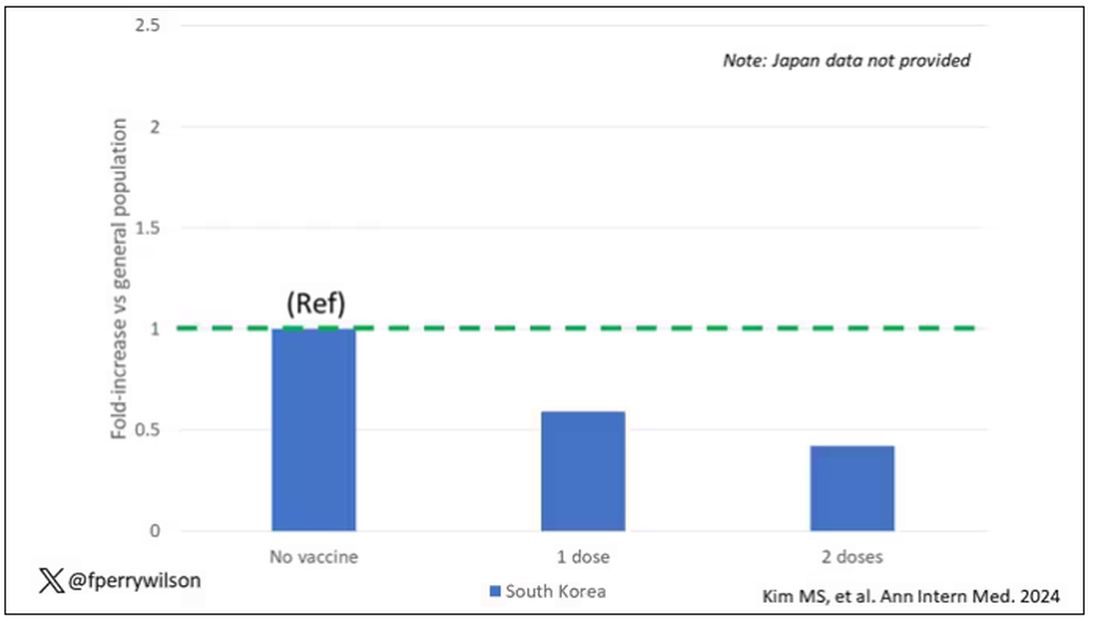

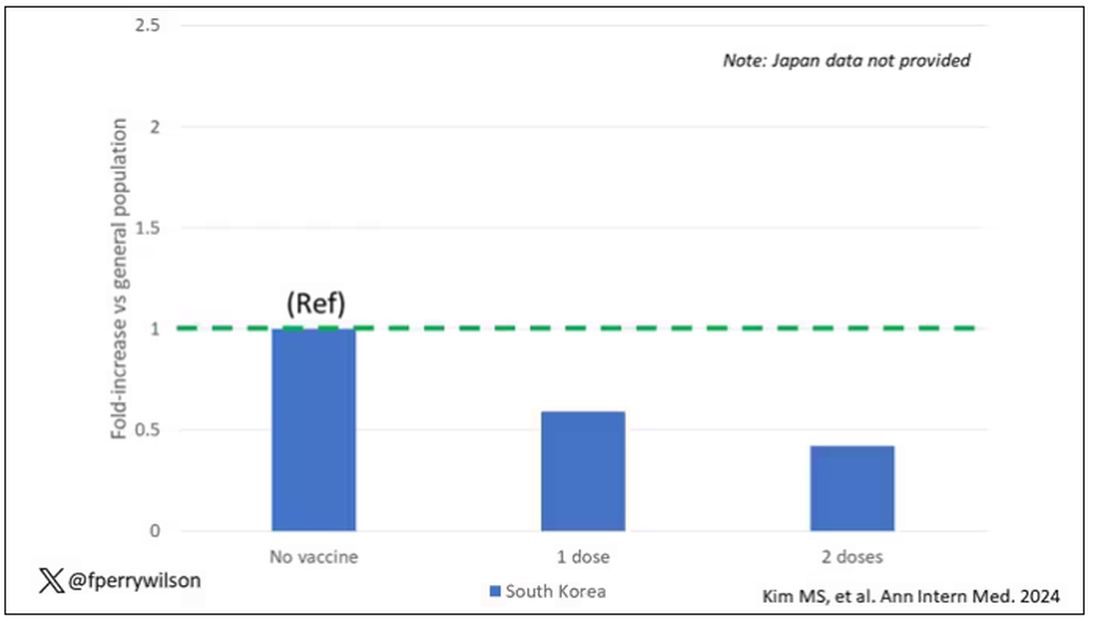

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s Next for the World’s First HIV Vaccine?

When the world needed a COVID vaccine, leading HIV investigators answered the call to intervene in the coronavirus pandemic. Now, efforts to discover the world’s first HIV vaccine are revitalized.

“The body is capable of making antibodies to protect us from HIV,” says Yunda Huang, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, who sat down with me before her talk today at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Huang spoke about the path forward for neutralizing antibody protection after the last attempt in a generation of HIV vaccine development ended in disappointment.

The past two decades marked the rise in HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies, with vaccine strategies to induce them. Promising advances include germline approaches, mRNA, and nanoparticle technologies.

The PrEP vaccine trial testing two experimental prevention regimens in Africa was stopped after investigators reported there is “little to no chance” the trial will show the vaccines are effective.

A Shape-Shifting Virus

HIV has been called the shape-shifting virus because it disguises itself so that even when people are able to make antibodies to it, the virus changes to escape.

But Dr. Huang and others are optimistic that an effective vaccine is still possible.

“We cannot and will not lose hope that the world will have an effective HIV vaccine that is accessible by all who need it, anywhere,” International AIDS Society (IAS) Executive Director Birgit Poniatowski said in a statement in December, when the trial was stopped.

HIV is a still persistent problem in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that reports it has affected an estimated 1.2 million people.

With new people infected every day around the globe, Dr. Huang says she feels a sense of urgency to help. “I think about all the people around the globe and the large number of young girls being hurt and I know our big pool of talent can intervene to change what we see happening.”

Dr. Huang says the clinical trial failures we’ve seen so far will help guide next steps in HIV research as much as successes typically do.

Advances in the Field

With significant advances in protein nanoparticle science, mRNA technology, adjuvant development, and B-cell and antibody analyses, a new wave of clinical trials are on the way.

And with so many new approaches in the works, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network is retooling how it operates to navigate a burgeoning field and identify the most promising regimens.

A new Discovery Medicine Program will help the network assess new vaccine candidates. It will also aim to rule out others earlier on.

For COVID-19 and the flu, multimeric nanoparticles are an important alternative under investigation that could also be adapted for HIV.

Dr. Huang says she is particularly excited to watch the progress in cocktails of combination monoclonals. “I’ve been working in this field for 20 years now and there is a misconception that with pre-exposure prophylaxis, our job is done, but HIV is so far from away from being solved.”

But you just never know, Dr. Huang says. With new research, “we could bump on something at any point that changes everything.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When the world needed a COVID vaccine, leading HIV investigators answered the call to intervene in the coronavirus pandemic. Now, efforts to discover the world’s first HIV vaccine are revitalized.

“The body is capable of making antibodies to protect us from HIV,” says Yunda Huang, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, who sat down with me before her talk today at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Huang spoke about the path forward for neutralizing antibody protection after the last attempt in a generation of HIV vaccine development ended in disappointment.

The past two decades marked the rise in HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies, with vaccine strategies to induce them. Promising advances include germline approaches, mRNA, and nanoparticle technologies.

The PrEP vaccine trial testing two experimental prevention regimens in Africa was stopped after investigators reported there is “little to no chance” the trial will show the vaccines are effective.

A Shape-Shifting Virus

HIV has been called the shape-shifting virus because it disguises itself so that even when people are able to make antibodies to it, the virus changes to escape.

But Dr. Huang and others are optimistic that an effective vaccine is still possible.

“We cannot and will not lose hope that the world will have an effective HIV vaccine that is accessible by all who need it, anywhere,” International AIDS Society (IAS) Executive Director Birgit Poniatowski said in a statement in December, when the trial was stopped.

HIV is a still persistent problem in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that reports it has affected an estimated 1.2 million people.

With new people infected every day around the globe, Dr. Huang says she feels a sense of urgency to help. “I think about all the people around the globe and the large number of young girls being hurt and I know our big pool of talent can intervene to change what we see happening.”

Dr. Huang says the clinical trial failures we’ve seen so far will help guide next steps in HIV research as much as successes typically do.

Advances in the Field

With significant advances in protein nanoparticle science, mRNA technology, adjuvant development, and B-cell and antibody analyses, a new wave of clinical trials are on the way.

And with so many new approaches in the works, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network is retooling how it operates to navigate a burgeoning field and identify the most promising regimens.

A new Discovery Medicine Program will help the network assess new vaccine candidates. It will also aim to rule out others earlier on.

For COVID-19 and the flu, multimeric nanoparticles are an important alternative under investigation that could also be adapted for HIV.

Dr. Huang says she is particularly excited to watch the progress in cocktails of combination monoclonals. “I’ve been working in this field for 20 years now and there is a misconception that with pre-exposure prophylaxis, our job is done, but HIV is so far from away from being solved.”

But you just never know, Dr. Huang says. With new research, “we could bump on something at any point that changes everything.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When the world needed a COVID vaccine, leading HIV investigators answered the call to intervene in the coronavirus pandemic. Now, efforts to discover the world’s first HIV vaccine are revitalized.

“The body is capable of making antibodies to protect us from HIV,” says Yunda Huang, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, who sat down with me before her talk today at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Huang spoke about the path forward for neutralizing antibody protection after the last attempt in a generation of HIV vaccine development ended in disappointment.

The past two decades marked the rise in HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies, with vaccine strategies to induce them. Promising advances include germline approaches, mRNA, and nanoparticle technologies.

The PrEP vaccine trial testing two experimental prevention regimens in Africa was stopped after investigators reported there is “little to no chance” the trial will show the vaccines are effective.

A Shape-Shifting Virus

HIV has been called the shape-shifting virus because it disguises itself so that even when people are able to make antibodies to it, the virus changes to escape.

But Dr. Huang and others are optimistic that an effective vaccine is still possible.

“We cannot and will not lose hope that the world will have an effective HIV vaccine that is accessible by all who need it, anywhere,” International AIDS Society (IAS) Executive Director Birgit Poniatowski said in a statement in December, when the trial was stopped.

HIV is a still persistent problem in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that reports it has affected an estimated 1.2 million people.

With new people infected every day around the globe, Dr. Huang says she feels a sense of urgency to help. “I think about all the people around the globe and the large number of young girls being hurt and I know our big pool of talent can intervene to change what we see happening.”

Dr. Huang says the clinical trial failures we’ve seen so far will help guide next steps in HIV research as much as successes typically do.

Advances in the Field

With significant advances in protein nanoparticle science, mRNA technology, adjuvant development, and B-cell and antibody analyses, a new wave of clinical trials are on the way.

And with so many new approaches in the works, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network is retooling how it operates to navigate a burgeoning field and identify the most promising regimens.

A new Discovery Medicine Program will help the network assess new vaccine candidates. It will also aim to rule out others earlier on.

For COVID-19 and the flu, multimeric nanoparticles are an important alternative under investigation that could also be adapted for HIV.

Dr. Huang says she is particularly excited to watch the progress in cocktails of combination monoclonals. “I’ve been working in this field for 20 years now and there is a misconception that with pre-exposure prophylaxis, our job is done, but HIV is so far from away from being solved.”

But you just never know, Dr. Huang says. With new research, “we could bump on something at any point that changes everything.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CROI 2024

Doxy-PEP Cut STIs in San Francisco in Half

Syphilis and chlamydia infections were reduced by half among men who have sex with men and transgender women 1 year after San Francisco rolled out doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP), according to data presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) this week.

After a clinical trial showed that doxy-PEP taken after sex reduced the chance of acquiring syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia by about two-thirds, the San Francisco Department of Public Health released the first guidelines in the country in October 2022.

So far, more than 3700 people in San Francisco have been prescribed doxy-PEP, reports Stephanie Cohen, MD, director of HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention in the Disease Prevention and Control Branch of Public Health.

Dr. Cohen and her colleagues spent a year monitoring the uptake of doxy-PEP and used a computer model to predict what the rates of sexually transmitted infection would have been without doxy-PEP.

In November 2023, 13 months after the guidelines were introduced, they found that monthly chlamydia and early syphilis infections were 50% and 51% lower, respectively, than what was predicted by the model.

Fewer Infections

The drop in infections is having a tangible effect on patients in San Francisco, and many clinicians are noting that they are seeing far fewer positive tests. “The results that we’re seeing on a city-wide level are absolutely being experienced by individual providers and patients,” Dr. Cohen said.

However, the analysis showed no effect on rates of gonorrhea. It’s not clear why, although Dr. Cohen points out that doxy-PEP was less effective against gonorrhea in the clinical trial. And “there could be other factors in play,” she added. “Adherence might matter more, or it could be affected by the prevalence of tetracycline resistance in the community.”

With rates of STIs, particularly syphilis, quickly rising in recent years, healthcare providers have been scrambling to find effective interventions. So far, doxy-PEP has shown the most promise. “We’ve known for a while that all of the strategies we’ve been employing don’t seem to be working,” noted Chase Cannon, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “That’s why doxy-PEP is important. We haven’t had anything that can deflect the curve in a long time.”

What About the Side Effects?

Some concerns remain, however, about the widespread prophylactic use of antibiotics. There are no long-term safety data on the potential side effects of doxy-PEP, and there is still a lot of stigma around interventions that allow people to have sex the way they want, said Dr. Cannon.

But perhaps, the biggest concern is that doxy-PEP could contribute to antibiotic resistance. Those fears are not misplaced, Dr. Cannon added. The results of one study, presented in a poster at CROI, showed that stool samples from people prescribed doxy-PEP had elevated levels of bacterial genes that can confer resistance to tetracyclines, the class of antibiotics to which doxycycline belongs. There was no change in resistance to other classes of antibiotics and no difference in bacterial diversity over the 6 months of the study.

Dr. Cannon cautioned, however, that we can’t extrapolate these results to clinical outcomes. “We can look for signals [of resistance], but we don’t know if this means someone will fail therapy for chlamydia or syphilis,” he said.

There are still many challenges to overcome before doxy-PEP can be rolled out widely, Dr. Cohen explained. There is a lack of consensus among healthcare professionals about who should be offered doxy-PEP. The clinical trial results and the San Fransisco guidelines only apply to men who have sex with men and to transgender women.

Some clinicians argue that the intervention should be provided to a broader population, whereas others want to see more research to ensure that unnecessary antibiotic use is minimized.

So far just one study has tested doxy-PEP in another population — in women in Kenya — and it was found to not be effective. But the data suggest that adherence to the protocol was poor in that study, so the results may not be reliable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We need effective prevention tools for all genders, especially cis women who bear most of the morbidity,” she said. “It stands to reason that this should work for them, but without high-quality evidence, there is insufficient information to make a recommendation for cis women.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently reviewing public and expert comments and refining final guidelines for release in the coming months, which should alleviate some of the uncertainty. “Many providers are waiting for that guidance before they will feel confident moving forward,” Dr. Cohen noted.

But despite the risks and uncertainty, doxy-PEP looks set to be a major part of the fight against STIs going forward. “Doxy-PEP is essential for us as a nation to be dealing with the syphilis epidemic,” Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said in a video introduction to CROI.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Syphilis and chlamydia infections were reduced by half among men who have sex with men and transgender women 1 year after San Francisco rolled out doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP), according to data presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) this week.

After a clinical trial showed that doxy-PEP taken after sex reduced the chance of acquiring syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia by about two-thirds, the San Francisco Department of Public Health released the first guidelines in the country in October 2022.

So far, more than 3700 people in San Francisco have been prescribed doxy-PEP, reports Stephanie Cohen, MD, director of HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention in the Disease Prevention and Control Branch of Public Health.

Dr. Cohen and her colleagues spent a year monitoring the uptake of doxy-PEP and used a computer model to predict what the rates of sexually transmitted infection would have been without doxy-PEP.

In November 2023, 13 months after the guidelines were introduced, they found that monthly chlamydia and early syphilis infections were 50% and 51% lower, respectively, than what was predicted by the model.

Fewer Infections

The drop in infections is having a tangible effect on patients in San Francisco, and many clinicians are noting that they are seeing far fewer positive tests. “The results that we’re seeing on a city-wide level are absolutely being experienced by individual providers and patients,” Dr. Cohen said.

However, the analysis showed no effect on rates of gonorrhea. It’s not clear why, although Dr. Cohen points out that doxy-PEP was less effective against gonorrhea in the clinical trial. And “there could be other factors in play,” she added. “Adherence might matter more, or it could be affected by the prevalence of tetracycline resistance in the community.”

With rates of STIs, particularly syphilis, quickly rising in recent years, healthcare providers have been scrambling to find effective interventions. So far, doxy-PEP has shown the most promise. “We’ve known for a while that all of the strategies we’ve been employing don’t seem to be working,” noted Chase Cannon, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “That’s why doxy-PEP is important. We haven’t had anything that can deflect the curve in a long time.”

What About the Side Effects?

Some concerns remain, however, about the widespread prophylactic use of antibiotics. There are no long-term safety data on the potential side effects of doxy-PEP, and there is still a lot of stigma around interventions that allow people to have sex the way they want, said Dr. Cannon.

But perhaps, the biggest concern is that doxy-PEP could contribute to antibiotic resistance. Those fears are not misplaced, Dr. Cannon added. The results of one study, presented in a poster at CROI, showed that stool samples from people prescribed doxy-PEP had elevated levels of bacterial genes that can confer resistance to tetracyclines, the class of antibiotics to which doxycycline belongs. There was no change in resistance to other classes of antibiotics and no difference in bacterial diversity over the 6 months of the study.

Dr. Cannon cautioned, however, that we can’t extrapolate these results to clinical outcomes. “We can look for signals [of resistance], but we don’t know if this means someone will fail therapy for chlamydia or syphilis,” he said.

There are still many challenges to overcome before doxy-PEP can be rolled out widely, Dr. Cohen explained. There is a lack of consensus among healthcare professionals about who should be offered doxy-PEP. The clinical trial results and the San Fransisco guidelines only apply to men who have sex with men and to transgender women.

Some clinicians argue that the intervention should be provided to a broader population, whereas others want to see more research to ensure that unnecessary antibiotic use is minimized.

So far just one study has tested doxy-PEP in another population — in women in Kenya — and it was found to not be effective. But the data suggest that adherence to the protocol was poor in that study, so the results may not be reliable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We need effective prevention tools for all genders, especially cis women who bear most of the morbidity,” she said. “It stands to reason that this should work for them, but without high-quality evidence, there is insufficient information to make a recommendation for cis women.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently reviewing public and expert comments and refining final guidelines for release in the coming months, which should alleviate some of the uncertainty. “Many providers are waiting for that guidance before they will feel confident moving forward,” Dr. Cohen noted.

But despite the risks and uncertainty, doxy-PEP looks set to be a major part of the fight against STIs going forward. “Doxy-PEP is essential for us as a nation to be dealing with the syphilis epidemic,” Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said in a video introduction to CROI.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Syphilis and chlamydia infections were reduced by half among men who have sex with men and transgender women 1 year after San Francisco rolled out doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP), according to data presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) this week.

After a clinical trial showed that doxy-PEP taken after sex reduced the chance of acquiring syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia by about two-thirds, the San Francisco Department of Public Health released the first guidelines in the country in October 2022.

So far, more than 3700 people in San Francisco have been prescribed doxy-PEP, reports Stephanie Cohen, MD, director of HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention in the Disease Prevention and Control Branch of Public Health.

Dr. Cohen and her colleagues spent a year monitoring the uptake of doxy-PEP and used a computer model to predict what the rates of sexually transmitted infection would have been without doxy-PEP.

In November 2023, 13 months after the guidelines were introduced, they found that monthly chlamydia and early syphilis infections were 50% and 51% lower, respectively, than what was predicted by the model.

Fewer Infections

The drop in infections is having a tangible effect on patients in San Francisco, and many clinicians are noting that they are seeing far fewer positive tests. “The results that we’re seeing on a city-wide level are absolutely being experienced by individual providers and patients,” Dr. Cohen said.

However, the analysis showed no effect on rates of gonorrhea. It’s not clear why, although Dr. Cohen points out that doxy-PEP was less effective against gonorrhea in the clinical trial. And “there could be other factors in play,” she added. “Adherence might matter more, or it could be affected by the prevalence of tetracycline resistance in the community.”

With rates of STIs, particularly syphilis, quickly rising in recent years, healthcare providers have been scrambling to find effective interventions. So far, doxy-PEP has shown the most promise. “We’ve known for a while that all of the strategies we’ve been employing don’t seem to be working,” noted Chase Cannon, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “That’s why doxy-PEP is important. We haven’t had anything that can deflect the curve in a long time.”

What About the Side Effects?

Some concerns remain, however, about the widespread prophylactic use of antibiotics. There are no long-term safety data on the potential side effects of doxy-PEP, and there is still a lot of stigma around interventions that allow people to have sex the way they want, said Dr. Cannon.

But perhaps, the biggest concern is that doxy-PEP could contribute to antibiotic resistance. Those fears are not misplaced, Dr. Cannon added. The results of one study, presented in a poster at CROI, showed that stool samples from people prescribed doxy-PEP had elevated levels of bacterial genes that can confer resistance to tetracyclines, the class of antibiotics to which doxycycline belongs. There was no change in resistance to other classes of antibiotics and no difference in bacterial diversity over the 6 months of the study.

Dr. Cannon cautioned, however, that we can’t extrapolate these results to clinical outcomes. “We can look for signals [of resistance], but we don’t know if this means someone will fail therapy for chlamydia or syphilis,” he said.

There are still many challenges to overcome before doxy-PEP can be rolled out widely, Dr. Cohen explained. There is a lack of consensus among healthcare professionals about who should be offered doxy-PEP. The clinical trial results and the San Fransisco guidelines only apply to men who have sex with men and to transgender women.

Some clinicians argue that the intervention should be provided to a broader population, whereas others want to see more research to ensure that unnecessary antibiotic use is minimized.

So far just one study has tested doxy-PEP in another population — in women in Kenya — and it was found to not be effective. But the data suggest that adherence to the protocol was poor in that study, so the results may not be reliable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We need effective prevention tools for all genders, especially cis women who bear most of the morbidity,” she said. “It stands to reason that this should work for them, but without high-quality evidence, there is insufficient information to make a recommendation for cis women.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently reviewing public and expert comments and refining final guidelines for release in the coming months, which should alleviate some of the uncertainty. “Many providers are waiting for that guidance before they will feel confident moving forward,” Dr. Cohen noted.

But despite the risks and uncertainty, doxy-PEP looks set to be a major part of the fight against STIs going forward. “Doxy-PEP is essential for us as a nation to be dealing with the syphilis epidemic,” Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said in a video introduction to CROI.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Bartonella henselae Infection May Occasionally Distract Immune Control of Latent Human Herpesviruses

To the Editor:

We read with interest the September 2023 Cutis article by Swink et al,1 “Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl.” The authors documented the possibility of Bartonella henselae infection as another causative agent for pityriasis rosea (PR) even though the association of PR with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV-7 infection is based on several consistent observations and not on occasional findings. The association of PR with endogenous systemic reactivation of HHV-6 and HHV-7 has been identified with different investigations and laboratory techniques. Using polymerase chain reaction, real-time calibrated quantitative polymerase chain reaction, in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy, HHV-6 and HHV-7 have been detected in plasma (a marker of active viral replication), peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and skin lesions from patients with PR.2 In addition, HHV-6 and HHV-7 messenger RNA expression and their specific antigens have been detected in PR skin lesions and herpesvirus virions in various stages of morphogenesis as well as in the supernatant of co-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with PR.2,3 Lastly, the increased levels of several particular cytokines and chemokinesin the sera of patients with PR support a viral role in its pathogenesis.4

Bartonella henselae is a gram-negative intracellular facultative bacterium that is commonly implicated in causing zoonotic infections worldwide. The incidence of cat-scratch disease (CSD) was reported to be 6.4 cases per 100,000 population in adults and 9.4 cases per 100,000 population in children aged 5 to 9 years globally.5 Approximately 24,000 cases of CSD are reported in the United States every year.6 Therefore, considering these data, if B henselae was a causative agent for PR, the eruption would be observed frequently in many patients with CSD, which is not the case. On the contrary, it is possible that B henselae infection may have reactivated HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 infection. It is well established that B henselae causes a robust cell-mediated immune response by activating natural killer and helper T cells (TH1) and enhancement of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.7 It could be assumed that by strongly stimulating the immune response and polarizing it to a specific antigen cell response, B henselae infection may temporarily distract the T cell-mediated control of the latent infections, such as HHV-6 and HHV-7, which may reactivate and cause PR.

It is important to point out that a case of concomitant B henselae and Epstein-Barr virus infection has been described.8 Even in that case, the B henselae infection may have reactivated Epstein-Barr virus as well as HHV-6 and HHV-7 in the case described by Swink et al.1 Epstein-Barr virus reactivation has been detected in one case8 through serologic testing—IgM, IgG, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG, and heterophile antibodies—as there were no dermatologic manifestations that may be related to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation from latency.9

In conclusion, a viral or bacterial infection such as Epstein-Barr virus or B henselae may have a transactivating function allowing another (latent) virus such as HHV-6 or HHV-7 to reactivate. Indeed, it has been described that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a transactivator agent triggering HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation, thereby indirectly causing PR clinical manifestation.10

- Swink SM, Rhodes LP, Levin J. Cat scratch disease presenting with concurrent pityriasis rosea in a 10-year-old girl. Cutis. 2023;112:E24-E26. doi:10.12788/cutis.0861

- Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234-1240.

- Rebora A, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Pityriasis rosea and other infectious eruptions during pregnancy: possible life-threatening health conditions for the fetus. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:105-112.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Broccolo F, et al. The role of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the pathogenesis of pityriasis rosea. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:438963. doi:10.1155/2015/438963

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Ackson LA, Perkins BA, Wenger JD. Cat scratch disease in the United States: an analysis of three national databases. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1707-1711.

- Resto-Ruiz S, Burgess A, Anderson BE. The role of the host immune response in pathogenesis of Bartonella henselae. DNA Cell Biol. 2003; 22:431-440.

- Aparicio-Casares H, Puente-Rico MH, Tomé-Nestal C, et al. A pediatric case of Bartonella henselae and Epstein Barr virus disease with bone and hepatosplenic involvement. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2021;78:467-473.

- Ciccarese G, Trave I, Herzum A, et al. Dermatological manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus systemic infection: a case report and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1202-1209.

- Drago F, Broccolo F, Ciccarese G. Pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, and herpes zoster in the setting of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:586-590.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the September 2023 Cutis article by Swink et al,1 “Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl.” The authors documented the possibility of Bartonella henselae infection as another causative agent for pityriasis rosea (PR) even though the association of PR with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV-7 infection is based on several consistent observations and not on occasional findings. The association of PR with endogenous systemic reactivation of HHV-6 and HHV-7 has been identified with different investigations and laboratory techniques. Using polymerase chain reaction, real-time calibrated quantitative polymerase chain reaction, in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy, HHV-6 and HHV-7 have been detected in plasma (a marker of active viral replication), peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and skin lesions from patients with PR.2 In addition, HHV-6 and HHV-7 messenger RNA expression and their specific antigens have been detected in PR skin lesions and herpesvirus virions in various stages of morphogenesis as well as in the supernatant of co-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with PR.2,3 Lastly, the increased levels of several particular cytokines and chemokinesin the sera of patients with PR support a viral role in its pathogenesis.4

Bartonella henselae is a gram-negative intracellular facultative bacterium that is commonly implicated in causing zoonotic infections worldwide. The incidence of cat-scratch disease (CSD) was reported to be 6.4 cases per 100,000 population in adults and 9.4 cases per 100,000 population in children aged 5 to 9 years globally.5 Approximately 24,000 cases of CSD are reported in the United States every year.6 Therefore, considering these data, if B henselae was a causative agent for PR, the eruption would be observed frequently in many patients with CSD, which is not the case. On the contrary, it is possible that B henselae infection may have reactivated HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 infection. It is well established that B henselae causes a robust cell-mediated immune response by activating natural killer and helper T cells (TH1) and enhancement of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.7 It could be assumed that by strongly stimulating the immune response and polarizing it to a specific antigen cell response, B henselae infection may temporarily distract the T cell-mediated control of the latent infections, such as HHV-6 and HHV-7, which may reactivate and cause PR.

It is important to point out that a case of concomitant B henselae and Epstein-Barr virus infection has been described.8 Even in that case, the B henselae infection may have reactivated Epstein-Barr virus as well as HHV-6 and HHV-7 in the case described by Swink et al.1 Epstein-Barr virus reactivation has been detected in one case8 through serologic testing—IgM, IgG, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG, and heterophile antibodies—as there were no dermatologic manifestations that may be related to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation from latency.9

In conclusion, a viral or bacterial infection such as Epstein-Barr virus or B henselae may have a transactivating function allowing another (latent) virus such as HHV-6 or HHV-7 to reactivate. Indeed, it has been described that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a transactivator agent triggering HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation, thereby indirectly causing PR clinical manifestation.10

To the Editor:

We read with interest the September 2023 Cutis article by Swink et al,1 “Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl.” The authors documented the possibility of Bartonella henselae infection as another causative agent for pityriasis rosea (PR) even though the association of PR with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV-7 infection is based on several consistent observations and not on occasional findings. The association of PR with endogenous systemic reactivation of HHV-6 and HHV-7 has been identified with different investigations and laboratory techniques. Using polymerase chain reaction, real-time calibrated quantitative polymerase chain reaction, in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy, HHV-6 and HHV-7 have been detected in plasma (a marker of active viral replication), peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and skin lesions from patients with PR.2 In addition, HHV-6 and HHV-7 messenger RNA expression and their specific antigens have been detected in PR skin lesions and herpesvirus virions in various stages of morphogenesis as well as in the supernatant of co-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with PR.2,3 Lastly, the increased levels of several particular cytokines and chemokinesin the sera of patients with PR support a viral role in its pathogenesis.4

Bartonella henselae is a gram-negative intracellular facultative bacterium that is commonly implicated in causing zoonotic infections worldwide. The incidence of cat-scratch disease (CSD) was reported to be 6.4 cases per 100,000 population in adults and 9.4 cases per 100,000 population in children aged 5 to 9 years globally.5 Approximately 24,000 cases of CSD are reported in the United States every year.6 Therefore, considering these data, if B henselae was a causative agent for PR, the eruption would be observed frequently in many patients with CSD, which is not the case. On the contrary, it is possible that B henselae infection may have reactivated HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 infection. It is well established that B henselae causes a robust cell-mediated immune response by activating natural killer and helper T cells (TH1) and enhancement of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.7 It could be assumed that by strongly stimulating the immune response and polarizing it to a specific antigen cell response, B henselae infection may temporarily distract the T cell-mediated control of the latent infections, such as HHV-6 and HHV-7, which may reactivate and cause PR.

It is important to point out that a case of concomitant B henselae and Epstein-Barr virus infection has been described.8 Even in that case, the B henselae infection may have reactivated Epstein-Barr virus as well as HHV-6 and HHV-7 in the case described by Swink et al.1 Epstein-Barr virus reactivation has been detected in one case8 through serologic testing—IgM, IgG, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen IgG, and heterophile antibodies—as there were no dermatologic manifestations that may be related to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation from latency.9

In conclusion, a viral or bacterial infection such as Epstein-Barr virus or B henselae may have a transactivating function allowing another (latent) virus such as HHV-6 or HHV-7 to reactivate. Indeed, it has been described that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a transactivator agent triggering HHV-6/HHV-7 reactivation, thereby indirectly causing PR clinical manifestation.10

- Swink SM, Rhodes LP, Levin J. Cat scratch disease presenting with concurrent pityriasis rosea in a 10-year-old girl. Cutis. 2023;112:E24-E26. doi:10.12788/cutis.0861

- Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234-1240.

- Rebora A, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Pityriasis rosea and other infectious eruptions during pregnancy: possible life-threatening health conditions for the fetus. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:105-112.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Broccolo F, et al. The role of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the pathogenesis of pityriasis rosea. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:438963. doi:10.1155/2015/438963

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Ackson LA, Perkins BA, Wenger JD. Cat scratch disease in the United States: an analysis of three national databases. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1707-1711.

- Resto-Ruiz S, Burgess A, Anderson BE. The role of the host immune response in pathogenesis of Bartonella henselae. DNA Cell Biol. 2003; 22:431-440.

- Aparicio-Casares H, Puente-Rico MH, Tomé-Nestal C, et al. A pediatric case of Bartonella henselae and Epstein Barr virus disease with bone and hepatosplenic involvement. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2021;78:467-473.

- Ciccarese G, Trave I, Herzum A, et al. Dermatological manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus systemic infection: a case report and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1202-1209.

- Drago F, Broccolo F, Ciccarese G. Pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, and herpes zoster in the setting of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:586-590.

- Swink SM, Rhodes LP, Levin J. Cat scratch disease presenting with concurrent pityriasis rosea in a 10-year-old girl. Cutis. 2023;112:E24-E26. doi:10.12788/cutis.0861

- Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234-1240.

- Rebora A, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Pityriasis rosea and other infectious eruptions during pregnancy: possible life-threatening health conditions for the fetus. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:105-112.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Broccolo F, et al. The role of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the pathogenesis of pityriasis rosea. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:438963. doi:10.1155/2015/438963

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73.

- Ackson LA, Perkins BA, Wenger JD. Cat scratch disease in the United States: an analysis of three national databases. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1707-1711.

- Resto-Ruiz S, Burgess A, Anderson BE. The role of the host immune response in pathogenesis of Bartonella henselae. DNA Cell Biol. 2003; 22:431-440.

- Aparicio-Casares H, Puente-Rico MH, Tomé-Nestal C, et al. A pediatric case of Bartonella henselae and Epstein Barr virus disease with bone and hepatosplenic involvement. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2021;78:467-473.

- Ciccarese G, Trave I, Herzum A, et al. Dermatological manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus systemic infection: a case report and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1202-1209.

- Drago F, Broccolo F, Ciccarese G. Pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, and herpes zoster in the setting of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:586-590.

Midwife’s Fake Vaccinations Deserve Harsh Punishment: Ethicist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Very recently, a homeopathic midwife in New York was fined $300,000 for giving out phony injections for kids who were looking to get immunized in order to go to school. She gave pellets, which are sometimes called nosodes, I believe, with homeopathic ingredients, meaning next to nothing in them, and then basically certified that these children — and there were over 1500 of them — were compliant with New York State requirements to be vaccinated to go to school.

However, homeopathy is straight-up bunk. We have seen it again and again discredited as just something that doesn’t work. It has a tradition, but it’s basically nonsense. It certainly doesn’t work as a way to vaccinate anybody.

This midwife basically lied and gave phony certification to the parents of these kids. I’m not talking about the COVID-19 vaccine. I’m talking measles, mumps, rubella, flu, and polio — the childhood immunization schedule. For whatever reason, they put their faith in her and she went along with this fraud.

I think the fine is appropriate, but I think she should be penalized further. Why? When you send 1500 kids to school, mostly in Long Island, New York, but to schools all over the place, you are setting up conditions to bring back epidemic diseases like measles.

We’re already seeing measles outbreaks. At least five states have them. There’s a significant measles outbreak in Philadelphia. Although I can’t say for sure, I believe those outbreaks are directly linked to parents, post–COVID-19, becoming vaccine hesitant and either not vaccinating and lying or going to alternative practitioners like this midwife and claiming that they have been vaccinated.

You’re doing harm not only to the children who you allow to go to school under phony pretenses, but also you’re putting their classmates at risk. We all know that measles is very, very contagious. You’re risking the return of a disease that leads to hospitalization and sometimes even death. That is basically unconscionable.

I think her license should be taken away and she should not be practicing anymore. I believe that anyone who is involved in this kind of phony, dangerous, fraudulent practice ought to be severely punished.

Pre–COVID-19, we had just about gotten rid of measles and mumps. We didn’t see these diseases. Sometimes parents got a bit lazy in childhood vaccination basically because we had used immunization to get rid of the diseases.

Going to alternative healers and allowing people to get away with fraudulent nonsense risks bringing back disabling and deadly killers is not fair to you, me, and other people who are put at risk. It’s not fair to the kids who go to school with other kids who they think are vaccinated but aren’t.

I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thanks for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Very recently, a homeopathic midwife in New York was fined $300,000 for giving out phony injections for kids who were looking to get immunized in order to go to school. She gave pellets, which are sometimes called nosodes, I believe, with homeopathic ingredients, meaning next to nothing in them, and then basically certified that these children — and there were over 1500 of them — were compliant with New York State requirements to be vaccinated to go to school.

However, homeopathy is straight-up bunk. We have seen it again and again discredited as just something that doesn’t work. It has a tradition, but it’s basically nonsense. It certainly doesn’t work as a way to vaccinate anybody.

This midwife basically lied and gave phony certification to the parents of these kids. I’m not talking about the COVID-19 vaccine. I’m talking measles, mumps, rubella, flu, and polio — the childhood immunization schedule. For whatever reason, they put their faith in her and she went along with this fraud.

I think the fine is appropriate, but I think she should be penalized further. Why? When you send 1500 kids to school, mostly in Long Island, New York, but to schools all over the place, you are setting up conditions to bring back epidemic diseases like measles.

We’re already seeing measles outbreaks. At least five states have them. There’s a significant measles outbreak in Philadelphia. Although I can’t say for sure, I believe those outbreaks are directly linked to parents, post–COVID-19, becoming vaccine hesitant and either not vaccinating and lying or going to alternative practitioners like this midwife and claiming that they have been vaccinated.

You’re doing harm not only to the children who you allow to go to school under phony pretenses, but also you’re putting their classmates at risk. We all know that measles is very, very contagious. You’re risking the return of a disease that leads to hospitalization and sometimes even death. That is basically unconscionable.

I think her license should be taken away and she should not be practicing anymore. I believe that anyone who is involved in this kind of phony, dangerous, fraudulent practice ought to be severely punished.

Pre–COVID-19, we had just about gotten rid of measles and mumps. We didn’t see these diseases. Sometimes parents got a bit lazy in childhood vaccination basically because we had used immunization to get rid of the diseases.

Going to alternative healers and allowing people to get away with fraudulent nonsense risks bringing back disabling and deadly killers is not fair to you, me, and other people who are put at risk. It’s not fair to the kids who go to school with other kids who they think are vaccinated but aren’t.

I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thanks for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Very recently, a homeopathic midwife in New York was fined $300,000 for giving out phony injections for kids who were looking to get immunized in order to go to school. She gave pellets, which are sometimes called nosodes, I believe, with homeopathic ingredients, meaning next to nothing in them, and then basically certified that these children — and there were over 1500 of them — were compliant with New York State requirements to be vaccinated to go to school.

However, homeopathy is straight-up bunk. We have seen it again and again discredited as just something that doesn’t work. It has a tradition, but it’s basically nonsense. It certainly doesn’t work as a way to vaccinate anybody.

This midwife basically lied and gave phony certification to the parents of these kids. I’m not talking about the COVID-19 vaccine. I’m talking measles, mumps, rubella, flu, and polio — the childhood immunization schedule. For whatever reason, they put their faith in her and she went along with this fraud.

I think the fine is appropriate, but I think she should be penalized further. Why? When you send 1500 kids to school, mostly in Long Island, New York, but to schools all over the place, you are setting up conditions to bring back epidemic diseases like measles.

We’re already seeing measles outbreaks. At least five states have them. There’s a significant measles outbreak in Philadelphia. Although I can’t say for sure, I believe those outbreaks are directly linked to parents, post–COVID-19, becoming vaccine hesitant and either not vaccinating and lying or going to alternative practitioners like this midwife and claiming that they have been vaccinated.

You’re doing harm not only to the children who you allow to go to school under phony pretenses, but also you’re putting their classmates at risk. We all know that measles is very, very contagious. You’re risking the return of a disease that leads to hospitalization and sometimes even death. That is basically unconscionable.

I think her license should be taken away and she should not be practicing anymore. I believe that anyone who is involved in this kind of phony, dangerous, fraudulent practice ought to be severely punished.

Pre–COVID-19, we had just about gotten rid of measles and mumps. We didn’t see these diseases. Sometimes parents got a bit lazy in childhood vaccination basically because we had used immunization to get rid of the diseases.

Going to alternative healers and allowing people to get away with fraudulent nonsense risks bringing back disabling and deadly killers is not fair to you, me, and other people who are put at risk. It’s not fair to the kids who go to school with other kids who they think are vaccinated but aren’t.

I’m Art Caplan, at the Division of Medical Ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Thanks for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Increased Risk of New Rheumatic Disease Follows COVID-19 Infection

The risk of developing a new autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIRD) is greater following a COVID-19 infection than after an influenza infection or in the general population, according to a study published March 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. More severe COVID-19 infections were linked to a greater risk of incident rheumatic disease, but vaccination appeared protective against development of a new AIRD.

“Importantly, this study shows the value of vaccination to prevent severe disease and these types of sequelae,” Anne Davidson, MBBS, a professor in the Institute of Molecular Medicine at The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

Previous research had already identified the likelihood of an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent development of a new AIRD. This new study, however, includes much larger cohorts from two different countries and relies on more robust methodology than previous studies, experts said.

“Unique steps were taken by the study authors to make sure that what they were looking at in terms of signal was most likely true,” Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. Dr. Davidson agreed, noting that these authors “were a bit more rigorous with ascertainment of the autoimmune diagnosis, using two codes and also checking that appropriate medications were administered.”

More Robust and Rigorous Research

Past cohort studies finding an increased risk of rheumatic disease after COVID-19 “based their findings solely on comparisons between infected and uninfected groups, which could be influenced by ascertainment bias due to disparities in care, differences in health-seeking tendencies, and inherent risks among the groups,” Min Seo Kim, MD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported. Their study, however, required at least two claims with codes for rheumatic disease and compared patients with COVID-19 to those with flu “to adjust for the potentially heightened detection of AIRD in SARS-CoV-2–infected persons owing to their interactions with the health care system.”

Dr. Alfred Kim said the fact that they used at least two claims codes “gives a little more credence that the patients were actually experiencing some sort of autoimmune inflammatory condition as opposed to a very transient issue post COVID that just went away on its own.”

He acknowledged that the previous research was reasonably strong, “especially in light of the fact that there has been so much work done on a molecular level demonstrating that COVID-19 is associated with a substantial increase in autoantibodies in a significant proportion of patients, so this always opened up the possibility that this could associate with some sort of autoimmune disease downstream.”

While the study is well done with a large population, “it still has limitations that might overestimate the effect,” Kevin W. Byram, MD, associate professor of medicine in rheumatology and immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “We certainly have seen individual cases of new rheumatic disease where COVID-19 infection is likely the trigger,” but the phenomenon is not new, he added.

“Many autoimmune diseases are spurred by a loss of tolerance that might be induced by a pathogen of some sort,” Dr. Byram said. “The study is right to point out different forms of bias that might be at play. One in particular that is important to consider in a study like this is the lack of case-level adjudication regarding the diagnosis of rheumatic disease” since the study relied on available ICD-10 codes and medication prescriptions.

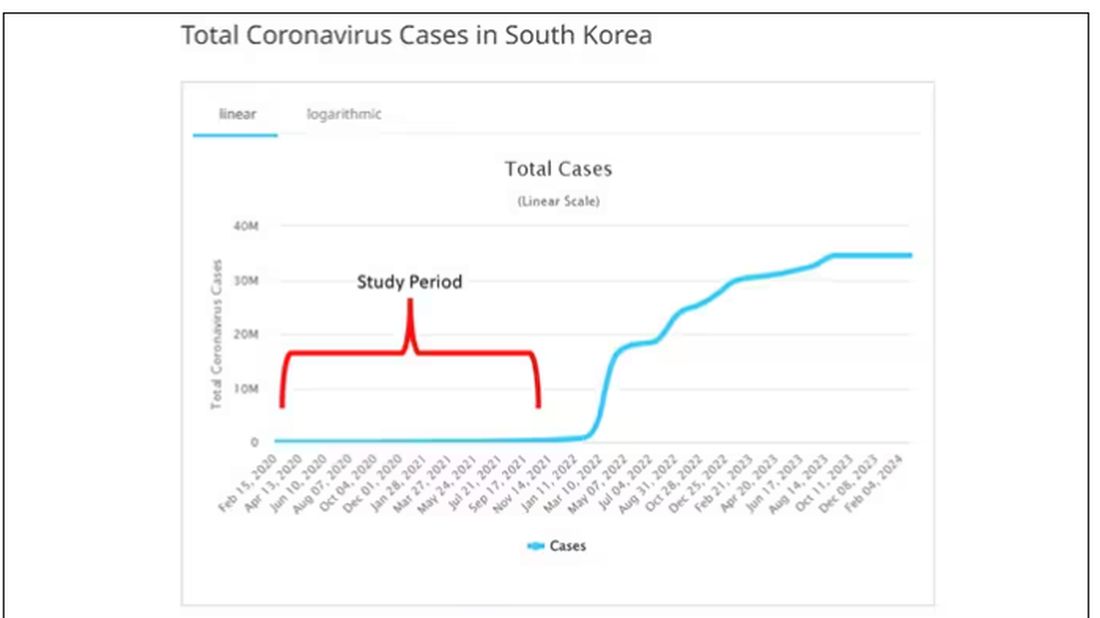

The researchers used national claims data to compare risk of incident AIRD in 10,027,506 South Korean and 12,218,680 Japanese adults, aged 20 and older, at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection, influenza infection, or a matched index date for uninfected control participants. Only patients with at least two claims for AIRD were considered to have a new diagnosis.

Patients who had COVID-19 between January 2020 and December 2021, confirmed by PCR or antigen testing, were matched 1:1 with patients who had test-confirmed influenza during that time and 1:4 with uninfected control participants, whose index date was set to the infection date of their matched COVID-19 patient.

The propensity score matching was based on age, sex, household income, urban versus rural residence, and various clinical characteristics and history: body mass index; blood pressure; fasting blood glucose; glomerular filtration rate; smoking status; alcohol consumption; weekly aerobic physical activity; comorbidity index; hospitalizations and outpatient visits in the previous year; past use of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension medication; and history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or respiratory infectious disease.

Patients with a history of AIRD or with coinfection or reinfection of COVID-19 and influenza were excluded, as were patients diagnosed with rheumatic disease within a month of COVID-19 infection.

Risk Varied With Disease Severity and Vaccination Status

Among the Korean patients, 3.9% had a COVID-19 infection and 0.98% had an influenza infection. After matching, the comparison populations included 94,504 patients with COVID-19 versus 94,504 patients with flu, and 177,083 patients with COVID-19 versus 675,750 uninfected controls.

The risk of developing an AIRD at least 1 month after infection in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was 25% higher than in uninfected control participants (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.25; 95% CI, 1.18–1.31; P < .05) and 30% higher than in influenza patients (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.02–1.59; P < .05). Specifically, risk in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was significantly increased for connective tissue disease and both treated and untreated AIRD but not for inflammatory arthritis.

Among the Japanese patients, 8.2% had COVID-19 and 0.99% had flu, resulting in matched populations of 115,003 with COVID-19 versus 110,310 with flu, and 960,849 with COVID-19 versus 1,606,873 uninfected patients. The effect size was larger in Japanese patients, with a 79% increased risk for AIRD in patients with COVID-19, compared with the general population (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.77–1.82; P < .05) and a 14% increased risk, compared with patients with influenza infection (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10–1.17; P < .05). In Japanese patients, risk was increased across all four categories, including a doubled risk for inflammatory arthritis (aHR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.96–2.07; P < .05), compared with the general population.

The researchers had data only from the South Korean cohort to calculate risk based on vaccination status, SARS-CoV-2 variant (wild type versus Delta), and COVID-19 severity. Researchers determined a COVID-19 infection to be moderate-to-severe based on billing codes for ICU admission or requiring oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement, or CPR.

Infection with both the original strain and the Delta variant were linked to similar increased risks for AIRD, but moderate to severe COVID-19 infections had greater risk of subsequent AIRD (aHR, 1.42; P < .05) than mild infections (aHR, 1.22; P < .05). Vaccination was linked to a lower risk of AIRD within the COVID-19 patient population: One dose was linked to a 41% reduced risk (HR, 0.59; P < .05) and two doses were linked to a 58% reduced risk (HR, 0.42; P < .05), regardless of the vaccine type, compared with unvaccinated patients with COVID-19. The apparent protective effect of vaccination was true only for patients with mild COVID-19, not those with moderate to severe infection.

“One has to wonder whether or not these people were at much higher risk of developing autoimmune disease that just got exposed because they got COVID, so that a fraction of these would have gotten an autoimmune disease downstream,” Dr. Alfred Kim said. Regardless, one clinical implication of the findings is the reduced risk in vaccinated patients, regardless of the vaccine type, given the fact that “mRNA vaccination in particular has not been associated with any autoantibody development,” he said.

Though the correlations in the study cannot translate to causation, several mechanisms might be at play in a viral infection contributing to autoimmune risk, Dr. Davidson said. Given that viral nucleic acids also recognize self-nucleic acids, “a large load of viral nucleic acid may break tolerance,” or “viral proteins could also mimic self-proteins,” she said. “In addition, tolerance may be broken by a highly inflammatory environment associated with the release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.”

The association between new-onset autoimmune disease and severe COVID-19 infection suggests multiple mechanisms may be involved in excess immune stimulation, Dr. Davidson said. But she added that it’s unclear how these findings, involving the original strain and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, might relate to currently circulating variants.

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships with industry. Dr. Alfred Kim has sponsored research agreements with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis; receives royalties from a patent with Kypha Inc.; and has done consulting or speaking for Amgen, ANI Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Exagen Diagnostics, GlaxoSmithKline, Kypha, Miltenyi Biotech, Pfizer, Rheumatology & Arthritis Learning Network, Synthekine, Techtonic Therapeutics, and UpToDate. Dr. Byram reported consulting for TenSixteen Bio. Dr. Davidson had no disclosures.

The risk of developing a new autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIRD) is greater following a COVID-19 infection than after an influenza infection or in the general population, according to a study published March 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. More severe COVID-19 infections were linked to a greater risk of incident rheumatic disease, but vaccination appeared protective against development of a new AIRD.

“Importantly, this study shows the value of vaccination to prevent severe disease and these types of sequelae,” Anne Davidson, MBBS, a professor in the Institute of Molecular Medicine at The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.