User login

Anti-infective update addresses SSSI choices

ORLANDO – What’s new in infectious disease therapeutics for dermatologists? He ran through an array of updates at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

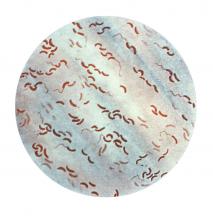

While naturally occurring smallpox was globally eradicated in 1980, small research stores are held in the United States and Russia, and effective antivirals are part of a strategy to combat bioweapons. Tecovirimat (TPOXX) is an antiviral that inhibits a major envelope protein that poxviruses need to produce extracellular virus. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in mid-2018, it is currently the only antiviral for treating variola virus infection approved in the United States, noted Dr. Finch of the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He added that 2 million doses are currently held in the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile.

Another anti-infective agent that won’t be used by those practicing in the United States, but which promises to alleviate a significant source of suffering in the developing world, is moxidectin. The anthelmintic had previously been approved for veterinary uses, but in June 2018, the FDA approved moxidectin to treat onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness. The drug defeats the parasitic worm by binding to glutamate-gated chloride ion channels; it is licensed by the nonprofit Medicines Development for Global Health.

Another antiparasitic drug, benznidazole, was approved to treat children aged 2-12 years with Chagas disease in 2017, Dr. Finch said.

Also in 2017, a topical quinolone, ozenoxacin (Xepi) was approved to treat impetigo in adults and children aged at least 2 months. Formulated as a 1% cream, ozenoxacin is applied twice daily for 5 days. In clinical trials, ozenoxacin was shown to be noninferior to retapamulin, he said.

A new topical choice is important as mupirocin resistance climbs, Dr. Finch added. A recent Greek study showed that 20% (437) of 2,137 staph infections studied were mupirocin resistant. Of the 20%, all but one were skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs), with 88% of these being impetigo.

In the United States, mupirocin resistance has been seen in one in three outpatients in a Florida study and in 31% of patients in a New York City sample. Other studies have shown mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates with resistance in the 10%-15% range among children with SSSIs, Dr. Finch said.

Two other new antibiotics to fight SSSIs can each be administered orally or intravenously. One, omadacycline (Nuzyra), is a novel tetracycline that maintains efficacy against bacteria that express tetracycline resistance through efflux and ribosomal protection. Approved in late 2018 for acute bacterial SSSIs, omadacycline treats not just methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus, but also Streptococcus species and gram-negative rods such as Enterobacter and Klebsiella pneumoniae, Dr. Finch noted.

Another new fluorinated quinolone, approved in 2017, delafloxacin (Baxdela) has broad spectrum activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.

Dr. Finch reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – What’s new in infectious disease therapeutics for dermatologists? He ran through an array of updates at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

While naturally occurring smallpox was globally eradicated in 1980, small research stores are held in the United States and Russia, and effective antivirals are part of a strategy to combat bioweapons. Tecovirimat (TPOXX) is an antiviral that inhibits a major envelope protein that poxviruses need to produce extracellular virus. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in mid-2018, it is currently the only antiviral for treating variola virus infection approved in the United States, noted Dr. Finch of the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He added that 2 million doses are currently held in the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile.

Another anti-infective agent that won’t be used by those practicing in the United States, but which promises to alleviate a significant source of suffering in the developing world, is moxidectin. The anthelmintic had previously been approved for veterinary uses, but in June 2018, the FDA approved moxidectin to treat onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness. The drug defeats the parasitic worm by binding to glutamate-gated chloride ion channels; it is licensed by the nonprofit Medicines Development for Global Health.

Another antiparasitic drug, benznidazole, was approved to treat children aged 2-12 years with Chagas disease in 2017, Dr. Finch said.

Also in 2017, a topical quinolone, ozenoxacin (Xepi) was approved to treat impetigo in adults and children aged at least 2 months. Formulated as a 1% cream, ozenoxacin is applied twice daily for 5 days. In clinical trials, ozenoxacin was shown to be noninferior to retapamulin, he said.

A new topical choice is important as mupirocin resistance climbs, Dr. Finch added. A recent Greek study showed that 20% (437) of 2,137 staph infections studied were mupirocin resistant. Of the 20%, all but one were skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs), with 88% of these being impetigo.

In the United States, mupirocin resistance has been seen in one in three outpatients in a Florida study and in 31% of patients in a New York City sample. Other studies have shown mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates with resistance in the 10%-15% range among children with SSSIs, Dr. Finch said.

Two other new antibiotics to fight SSSIs can each be administered orally or intravenously. One, omadacycline (Nuzyra), is a novel tetracycline that maintains efficacy against bacteria that express tetracycline resistance through efflux and ribosomal protection. Approved in late 2018 for acute bacterial SSSIs, omadacycline treats not just methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus, but also Streptococcus species and gram-negative rods such as Enterobacter and Klebsiella pneumoniae, Dr. Finch noted.

Another new fluorinated quinolone, approved in 2017, delafloxacin (Baxdela) has broad spectrum activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.

Dr. Finch reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – What’s new in infectious disease therapeutics for dermatologists? He ran through an array of updates at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

While naturally occurring smallpox was globally eradicated in 1980, small research stores are held in the United States and Russia, and effective antivirals are part of a strategy to combat bioweapons. Tecovirimat (TPOXX) is an antiviral that inhibits a major envelope protein that poxviruses need to produce extracellular virus. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in mid-2018, it is currently the only antiviral for treating variola virus infection approved in the United States, noted Dr. Finch of the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He added that 2 million doses are currently held in the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile.

Another anti-infective agent that won’t be used by those practicing in the United States, but which promises to alleviate a significant source of suffering in the developing world, is moxidectin. The anthelmintic had previously been approved for veterinary uses, but in June 2018, the FDA approved moxidectin to treat onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness. The drug defeats the parasitic worm by binding to glutamate-gated chloride ion channels; it is licensed by the nonprofit Medicines Development for Global Health.

Another antiparasitic drug, benznidazole, was approved to treat children aged 2-12 years with Chagas disease in 2017, Dr. Finch said.

Also in 2017, a topical quinolone, ozenoxacin (Xepi) was approved to treat impetigo in adults and children aged at least 2 months. Formulated as a 1% cream, ozenoxacin is applied twice daily for 5 days. In clinical trials, ozenoxacin was shown to be noninferior to retapamulin, he said.

A new topical choice is important as mupirocin resistance climbs, Dr. Finch added. A recent Greek study showed that 20% (437) of 2,137 staph infections studied were mupirocin resistant. Of the 20%, all but one were skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs), with 88% of these being impetigo.

In the United States, mupirocin resistance has been seen in one in three outpatients in a Florida study and in 31% of patients in a New York City sample. Other studies have shown mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates with resistance in the 10%-15% range among children with SSSIs, Dr. Finch said.

Two other new antibiotics to fight SSSIs can each be administered orally or intravenously. One, omadacycline (Nuzyra), is a novel tetracycline that maintains efficacy against bacteria that express tetracycline resistance through efflux and ribosomal protection. Approved in late 2018 for acute bacterial SSSIs, omadacycline treats not just methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus, but also Streptococcus species and gram-negative rods such as Enterobacter and Klebsiella pneumoniae, Dr. Finch noted.

Another new fluorinated quinolone, approved in 2017, delafloxacin (Baxdela) has broad spectrum activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.

Dr. Finch reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ODAC 2019

Artesunate to become first-line malaria treatment in U.S.

Starting April 1, 2019, intravenous artesunate will become the first-line treatment for malaria in the United States, following the discontinuation of quinidine, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved intravenous drug for severe malaria treatment.

Although artesunate is not approved or commercially available in the United States, it is recommended by the World Health Organization. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have made the drug available through an expanded use investigational new drug protocol, an FDA regulatory mechanism. Clinicians can obtain the medication through the CDC’s Malaria Hotline (770-488-7788); artesunate will be stocked at 10 quarantine stations and will be released to hospitals free of charge, according to a CDC announcement.

Clinical trials have illustrated that intravenous artesunate is safe, well tolerated, and can be administered even to infants, children, and pregnant women in the second and third trimester.

About 1,700 cases of malaria are reported in the United States per year, 300 of which are classified as severe. The CDC believes the supply of artesunate obtained will be sufficient to treat all cases of severe malaria in the country, according to a CDC press release.

Starting April 1, 2019, intravenous artesunate will become the first-line treatment for malaria in the United States, following the discontinuation of quinidine, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved intravenous drug for severe malaria treatment.

Although artesunate is not approved or commercially available in the United States, it is recommended by the World Health Organization. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have made the drug available through an expanded use investigational new drug protocol, an FDA regulatory mechanism. Clinicians can obtain the medication through the CDC’s Malaria Hotline (770-488-7788); artesunate will be stocked at 10 quarantine stations and will be released to hospitals free of charge, according to a CDC announcement.

Clinical trials have illustrated that intravenous artesunate is safe, well tolerated, and can be administered even to infants, children, and pregnant women in the second and third trimester.

About 1,700 cases of malaria are reported in the United States per year, 300 of which are classified as severe. The CDC believes the supply of artesunate obtained will be sufficient to treat all cases of severe malaria in the country, according to a CDC press release.

Starting April 1, 2019, intravenous artesunate will become the first-line treatment for malaria in the United States, following the discontinuation of quinidine, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved intravenous drug for severe malaria treatment.

Although artesunate is not approved or commercially available in the United States, it is recommended by the World Health Organization. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have made the drug available through an expanded use investigational new drug protocol, an FDA regulatory mechanism. Clinicians can obtain the medication through the CDC’s Malaria Hotline (770-488-7788); artesunate will be stocked at 10 quarantine stations and will be released to hospitals free of charge, according to a CDC announcement.

Clinical trials have illustrated that intravenous artesunate is safe, well tolerated, and can be administered even to infants, children, and pregnant women in the second and third trimester.

About 1,700 cases of malaria are reported in the United States per year, 300 of which are classified as severe. The CDC believes the supply of artesunate obtained will be sufficient to treat all cases of severe malaria in the country, according to a CDC press release.

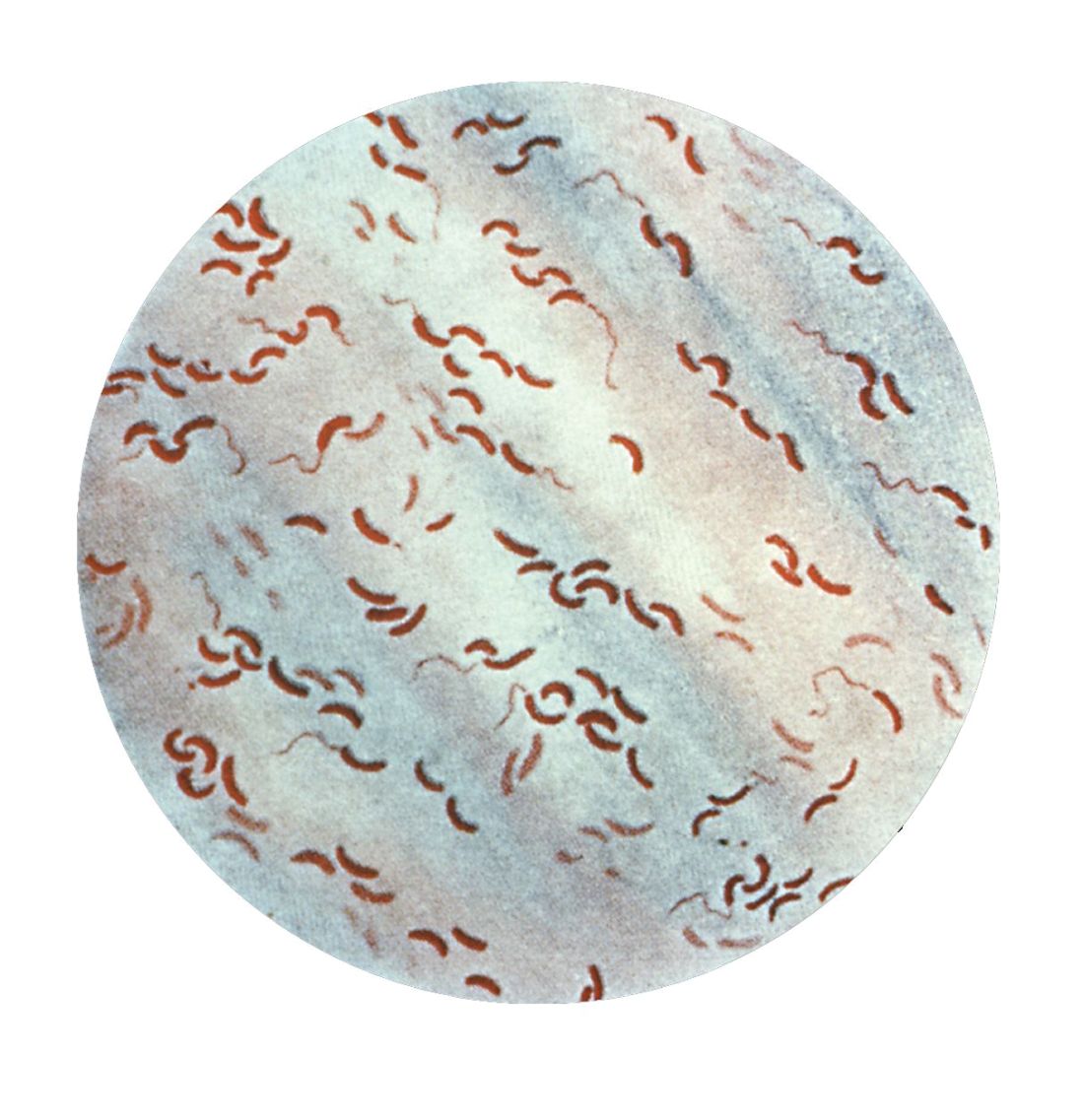

Tropical travelers’ top dermatologic infestations

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the female sand flea, Tunga penetrans, which burrows into the skin, where it lays hundreds of eggs within a matter of a few days. The sand flea is harbored by dogs, cats, pigs, cows, and rats. It’s rare to encounter tungiasis in travelers who’ve spent their time in fancy resorts, ecolodges, or yoga retreats, even if they’ve been parading around with lots of exposed skin. This is a disease of impoverished neighborhoods; hence, affected Americans often have been doing mission work abroad. In tropical areas, tungiasis is a debilitating, mutilating disorder marked by repeated infections, persistent inflammation, fissures, and ulcers.

Treatment involves a topical antiparasitic agent such as ivermectin, metrifonate, or thiabendazole and removal of the flea with sterile forceps or needles. But there is a promising new treatment concept: topical dimethicone, or polydimethylsiloxane. Studies have shown that following application of dimethicone, roughly 80%-90% of sand fleas are dead within 7 days.

“It’s nontoxic and has a purely physical mechanism of action, so resistance is unlikely ... I think it’s going to change the way this condition gets controlled,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Myiasis

The differential diagnosis of myiasis includes impetigo, a furuncle, an infected cyst, or a retained foreign body. Myiasis is a cutaneous infestation of the larva of certain flies, among the most notorious of which are the botfly, blowfly, and screwfly. The female fly lays her eggs in hot, humid, shady areas in soil contaminated by feces or urine. The larva can invade unbroken skin instantaneously and painlessly. Then it begins burrowing in. An air hole is always present in the skin so the organism can breathe. Ophthalmomyiasis is common, as are nasal and aural infections, the latter often accompanied by complaints of a crawling sensation inside the ear along with a buzzing noise. To avoid infection, in endemic areas it’s important not to go barefoot or to dry clothes on bushes or on the ground. Treatment entails elimination of the larva. Covering the air hole with petroleum jelly will force it to the surface. There is just one larva per furuncle, so no need for further extensive exploration once that critter has been extracted.

Leishmaniasis

The vector for this protozoan infection is the sandfly, which feeds from dusk to dawn noiselessly and painlessly. Because cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are understudied orphan diseases for which current treatments are less than satisfactory, prevention is the watchword. In endemic areas it’s important to close the windows and make use of air conditioning and ceiling fans when available. When in doubt, it’s advisable to sleep using a bed net treated with permethrin.

Cutaneous larva migrans

This skin eruption is caused by parasitic hookworms, the most common of which in the Americas is Ancylostoma braziliense. The eggs are transmitted through dog and cat feces deposited on soil or sand.

“Avoid laying or sitting on dry sand, even on a towel. And wear shoes,” Dr. Mesinkovska advised.

Among the CDC’s treatment recommendations for cutaneous larva migrans are several agents with poor efficacy and/or considerable side effects. But there is one standout therapy.

“Really, I would say nowadays the easiest thing is one 12-mg oral dose of ivermectin. It’s almost 100% effective,” she said.

Dr. Mesinkovska reported having no financial interests relevant to her talk.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the female sand flea, Tunga penetrans, which burrows into the skin, where it lays hundreds of eggs within a matter of a few days. The sand flea is harbored by dogs, cats, pigs, cows, and rats. It’s rare to encounter tungiasis in travelers who’ve spent their time in fancy resorts, ecolodges, or yoga retreats, even if they’ve been parading around with lots of exposed skin. This is a disease of impoverished neighborhoods; hence, affected Americans often have been doing mission work abroad. In tropical areas, tungiasis is a debilitating, mutilating disorder marked by repeated infections, persistent inflammation, fissures, and ulcers.

Treatment involves a topical antiparasitic agent such as ivermectin, metrifonate, or thiabendazole and removal of the flea with sterile forceps or needles. But there is a promising new treatment concept: topical dimethicone, or polydimethylsiloxane. Studies have shown that following application of dimethicone, roughly 80%-90% of sand fleas are dead within 7 days.

“It’s nontoxic and has a purely physical mechanism of action, so resistance is unlikely ... I think it’s going to change the way this condition gets controlled,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Myiasis

The differential diagnosis of myiasis includes impetigo, a furuncle, an infected cyst, or a retained foreign body. Myiasis is a cutaneous infestation of the larva of certain flies, among the most notorious of which are the botfly, blowfly, and screwfly. The female fly lays her eggs in hot, humid, shady areas in soil contaminated by feces or urine. The larva can invade unbroken skin instantaneously and painlessly. Then it begins burrowing in. An air hole is always present in the skin so the organism can breathe. Ophthalmomyiasis is common, as are nasal and aural infections, the latter often accompanied by complaints of a crawling sensation inside the ear along with a buzzing noise. To avoid infection, in endemic areas it’s important not to go barefoot or to dry clothes on bushes or on the ground. Treatment entails elimination of the larva. Covering the air hole with petroleum jelly will force it to the surface. There is just one larva per furuncle, so no need for further extensive exploration once that critter has been extracted.

Leishmaniasis

The vector for this protozoan infection is the sandfly, which feeds from dusk to dawn noiselessly and painlessly. Because cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are understudied orphan diseases for which current treatments are less than satisfactory, prevention is the watchword. In endemic areas it’s important to close the windows and make use of air conditioning and ceiling fans when available. When in doubt, it’s advisable to sleep using a bed net treated with permethrin.

Cutaneous larva migrans

This skin eruption is caused by parasitic hookworms, the most common of which in the Americas is Ancylostoma braziliense. The eggs are transmitted through dog and cat feces deposited on soil or sand.

“Avoid laying or sitting on dry sand, even on a towel. And wear shoes,” Dr. Mesinkovska advised.

Among the CDC’s treatment recommendations for cutaneous larva migrans are several agents with poor efficacy and/or considerable side effects. But there is one standout therapy.

“Really, I would say nowadays the easiest thing is one 12-mg oral dose of ivermectin. It’s almost 100% effective,” she said.

Dr. Mesinkovska reported having no financial interests relevant to her talk.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the female sand flea, Tunga penetrans, which burrows into the skin, where it lays hundreds of eggs within a matter of a few days. The sand flea is harbored by dogs, cats, pigs, cows, and rats. It’s rare to encounter tungiasis in travelers who’ve spent their time in fancy resorts, ecolodges, or yoga retreats, even if they’ve been parading around with lots of exposed skin. This is a disease of impoverished neighborhoods; hence, affected Americans often have been doing mission work abroad. In tropical areas, tungiasis is a debilitating, mutilating disorder marked by repeated infections, persistent inflammation, fissures, and ulcers.

Treatment involves a topical antiparasitic agent such as ivermectin, metrifonate, or thiabendazole and removal of the flea with sterile forceps or needles. But there is a promising new treatment concept: topical dimethicone, or polydimethylsiloxane. Studies have shown that following application of dimethicone, roughly 80%-90% of sand fleas are dead within 7 days.

“It’s nontoxic and has a purely physical mechanism of action, so resistance is unlikely ... I think it’s going to change the way this condition gets controlled,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Myiasis

The differential diagnosis of myiasis includes impetigo, a furuncle, an infected cyst, or a retained foreign body. Myiasis is a cutaneous infestation of the larva of certain flies, among the most notorious of which are the botfly, blowfly, and screwfly. The female fly lays her eggs in hot, humid, shady areas in soil contaminated by feces or urine. The larva can invade unbroken skin instantaneously and painlessly. Then it begins burrowing in. An air hole is always present in the skin so the organism can breathe. Ophthalmomyiasis is common, as are nasal and aural infections, the latter often accompanied by complaints of a crawling sensation inside the ear along with a buzzing noise. To avoid infection, in endemic areas it’s important not to go barefoot or to dry clothes on bushes or on the ground. Treatment entails elimination of the larva. Covering the air hole with petroleum jelly will force it to the surface. There is just one larva per furuncle, so no need for further extensive exploration once that critter has been extracted.

Leishmaniasis

The vector for this protozoan infection is the sandfly, which feeds from dusk to dawn noiselessly and painlessly. Because cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are understudied orphan diseases for which current treatments are less than satisfactory, prevention is the watchword. In endemic areas it’s important to close the windows and make use of air conditioning and ceiling fans when available. When in doubt, it’s advisable to sleep using a bed net treated with permethrin.

Cutaneous larva migrans

This skin eruption is caused by parasitic hookworms, the most common of which in the Americas is Ancylostoma braziliense. The eggs are transmitted through dog and cat feces deposited on soil or sand.

“Avoid laying or sitting on dry sand, even on a towel. And wear shoes,” Dr. Mesinkovska advised.

Among the CDC’s treatment recommendations for cutaneous larva migrans are several agents with poor efficacy and/or considerable side effects. But there is one standout therapy.

“Really, I would say nowadays the easiest thing is one 12-mg oral dose of ivermectin. It’s almost 100% effective,” she said.

Dr. Mesinkovska reported having no financial interests relevant to her talk.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM THE SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

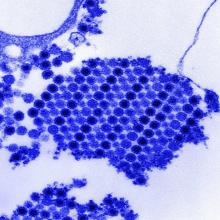

Dengue antibodies may reduce Zika infection risk

Previous dengue exposure may confer a protective effect against Zika virus infection, according to a paper published in Science.

In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,453 urban residents in Salvador, Brazil, to assess the impact of the 2015 Zika virus outbreak in the region. Data on dengue immunity was available for 642 of these individuals.

Overall, 73% of the cohort were seropositive for Zika virus. However, the frequency of seropositivity varied significantly by location, from 29% in a valley in the northeastern sector of the study area to 83% in the southeast corner; the authors wrote that this was consistent with some form of acquired immunity “blunting the efficiency of transmission.”

When researchers looked at the relationship between prior immunity to the dengue virus and the risk of Zika infection, they found that each doubling of total IgG titers against dengue NS1 was associated with a 9% reduction in the risk of Zika virus infection.

Individuals in the highest tertile of dengue IgG titers showed a 44% reduction in the odds of Zika seropositivity, compared with individuals with no or low dengue IgG titers, while those in the middle tertile of dengue IgG titer had a 38% reduction.

“These findings provide empirical support for the hypothesis that accumulated immunity drove ZIKV [Zika virus] to local extinction by reducing the efficiency of transmission,” wrote Isabel Rodriguez-Barraquer, MD, PhD, from the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

Individuals who were infected with the Zika virus but had high dengue IgG titers were significantly less likely to exhibit fever with viral infection, but had the same risk of developing rash as those with low or no IgG titers.

Researchers also examined the link between a subclass of IgG antibodies that are associated with more recent exposure to dengue virus – within the prior 6 months – and the risk of Zika virus infection. In contrast, they found that the levels of this subclass of antibodies, known as IgG3, were positively associated with an increased risk of Zika virus infection. Each doubling in IgG3 levels was associated with a 23% increase in the odds of being positive for Zika.

“This positive association might reflect an immune profile, in individuals who have experienced a recent DENV [dengue virus] infection, that is associated with having a greater risk of a subsequent ZIKV infection,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, it is also possible that higher levels of IgG3 are a proxy for frequent DENV exposure and thus greater risk of infection by Aedes aegypti–transmitted viruses.”

The study was supported by Yale University, a number of Brazilian research organizations, the Research Support Foundation for the State of São Paulo, CuraZika Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the National Institutes of Health. Three authors are listed on a patent application related to the work, and one reported an honoraria from Sanofi-Pasteur.

SOURCE: Rodriguez-Barraquer I et al. Science. 2019;36:607-10.

Previous dengue exposure may confer a protective effect against Zika virus infection, according to a paper published in Science.

In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,453 urban residents in Salvador, Brazil, to assess the impact of the 2015 Zika virus outbreak in the region. Data on dengue immunity was available for 642 of these individuals.

Overall, 73% of the cohort were seropositive for Zika virus. However, the frequency of seropositivity varied significantly by location, from 29% in a valley in the northeastern sector of the study area to 83% in the southeast corner; the authors wrote that this was consistent with some form of acquired immunity “blunting the efficiency of transmission.”

When researchers looked at the relationship between prior immunity to the dengue virus and the risk of Zika infection, they found that each doubling of total IgG titers against dengue NS1 was associated with a 9% reduction in the risk of Zika virus infection.

Individuals in the highest tertile of dengue IgG titers showed a 44% reduction in the odds of Zika seropositivity, compared with individuals with no or low dengue IgG titers, while those in the middle tertile of dengue IgG titer had a 38% reduction.

“These findings provide empirical support for the hypothesis that accumulated immunity drove ZIKV [Zika virus] to local extinction by reducing the efficiency of transmission,” wrote Isabel Rodriguez-Barraquer, MD, PhD, from the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

Individuals who were infected with the Zika virus but had high dengue IgG titers were significantly less likely to exhibit fever with viral infection, but had the same risk of developing rash as those with low or no IgG titers.

Researchers also examined the link between a subclass of IgG antibodies that are associated with more recent exposure to dengue virus – within the prior 6 months – and the risk of Zika virus infection. In contrast, they found that the levels of this subclass of antibodies, known as IgG3, were positively associated with an increased risk of Zika virus infection. Each doubling in IgG3 levels was associated with a 23% increase in the odds of being positive for Zika.

“This positive association might reflect an immune profile, in individuals who have experienced a recent DENV [dengue virus] infection, that is associated with having a greater risk of a subsequent ZIKV infection,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, it is also possible that higher levels of IgG3 are a proxy for frequent DENV exposure and thus greater risk of infection by Aedes aegypti–transmitted viruses.”

The study was supported by Yale University, a number of Brazilian research organizations, the Research Support Foundation for the State of São Paulo, CuraZika Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the National Institutes of Health. Three authors are listed on a patent application related to the work, and one reported an honoraria from Sanofi-Pasteur.

SOURCE: Rodriguez-Barraquer I et al. Science. 2019;36:607-10.

Previous dengue exposure may confer a protective effect against Zika virus infection, according to a paper published in Science.

In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,453 urban residents in Salvador, Brazil, to assess the impact of the 2015 Zika virus outbreak in the region. Data on dengue immunity was available for 642 of these individuals.

Overall, 73% of the cohort were seropositive for Zika virus. However, the frequency of seropositivity varied significantly by location, from 29% in a valley in the northeastern sector of the study area to 83% in the southeast corner; the authors wrote that this was consistent with some form of acquired immunity “blunting the efficiency of transmission.”

When researchers looked at the relationship between prior immunity to the dengue virus and the risk of Zika infection, they found that each doubling of total IgG titers against dengue NS1 was associated with a 9% reduction in the risk of Zika virus infection.

Individuals in the highest tertile of dengue IgG titers showed a 44% reduction in the odds of Zika seropositivity, compared with individuals with no or low dengue IgG titers, while those in the middle tertile of dengue IgG titer had a 38% reduction.

“These findings provide empirical support for the hypothesis that accumulated immunity drove ZIKV [Zika virus] to local extinction by reducing the efficiency of transmission,” wrote Isabel Rodriguez-Barraquer, MD, PhD, from the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

Individuals who were infected with the Zika virus but had high dengue IgG titers were significantly less likely to exhibit fever with viral infection, but had the same risk of developing rash as those with low or no IgG titers.

Researchers also examined the link between a subclass of IgG antibodies that are associated with more recent exposure to dengue virus – within the prior 6 months – and the risk of Zika virus infection. In contrast, they found that the levels of this subclass of antibodies, known as IgG3, were positively associated with an increased risk of Zika virus infection. Each doubling in IgG3 levels was associated with a 23% increase in the odds of being positive for Zika.

“This positive association might reflect an immune profile, in individuals who have experienced a recent DENV [dengue virus] infection, that is associated with having a greater risk of a subsequent ZIKV infection,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, it is also possible that higher levels of IgG3 are a proxy for frequent DENV exposure and thus greater risk of infection by Aedes aegypti–transmitted viruses.”

The study was supported by Yale University, a number of Brazilian research organizations, the Research Support Foundation for the State of São Paulo, CuraZika Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the National Institutes of Health. Three authors are listed on a patent application related to the work, and one reported an honoraria from Sanofi-Pasteur.

SOURCE: Rodriguez-Barraquer I et al. Science. 2019;36:607-10.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: Higher dengue antibody titers are associated with a lower risk of Zika virus infection.

Major finding: The highest tertile of dengue antibody titers was associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of Zika seropositivity.

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 1,453 residents in Salvador, Brazil.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Yale University, a number of Brazilian research organizations, the Research Support Foundation for the State of São Paulo, CuraZika Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the National Institutes of Health. Three authors are listed on a patent application related to the work, and one reported an honoraria from Sanofi-Pasteur.

Source: Rodriguez-Barraquer I et al. Science. 2019;36:607-10.

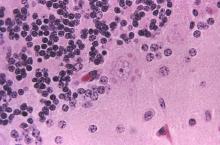

Single-dose tafenoquine appears to prevent malaria relapse

Single-dose tafenoquine therapy safely reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax relapse in patients with normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, according to the results of two phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials.

Findings from both studies were published in two separate reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the first study, the Dose and Efficacy Trial Evaluating Chloroquine and Tafenoquine in Vivax Elimination (DETECTIVE), the risk of P. vivax recurrence was approximately 70% lower with tafenoquine versus placebo, wrote Marcus V.G. Lacerda, MD, of Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado in Manaus, Brazil, and his colleagues.

The study included 522 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Patients received 3 days of chloroquine therapy (600 mg on days 1 and 2, and 300 mg on day 3) and were randomly assigned on a 2:1:1 basis to receive a single 300-mg dose of tafenoquine on day 1 or 2, primaquine once daily for 14 days, or placebo.

Since primaquine and tafenoquine can cause clinically significant hemolysis in individuals with G6PD deficiency, the study included only patients with normal G6PD activity.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 62% of tafenoquine recipients were free from P. vivax recurrence (95% confidence interval [CI], 55%-69%) at 6 months, as were 70% of primaquine recipients (95% CI, 60%-77%) and 28% of placebo recipients (95% CI, 20%-37%). Compared with placebo, the reduction in risk of recurrence was 70% with tafenoquine (hazard ratio [HR], 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22-0.40; P less than .001) and 74% with primaquine.

Declines in hemoglobin levels were greatest in the tafenoquine group but were not associated with symptomatic anemia and resolved without intervention, the investigators wrote.

In addition to the quantitative G6PD test, the investigators also evaluated a qualitative test, which “failed to identify 16 patients most at risk for hemolysis,” they reported. “If tafenoquine use is expanded, adoption of reliable quantitative point-of-care G6PD tests will be needed; such tests are not currently available but are in development.”

In the second study, Global Assessment of Tafenoquine Hemolytic Risk (GATHER), Alejandro Llanos-Cuentas, MD, of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, and his colleagues enrolled 251 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Columbia, Vietnam, and Thailand. They attempted to recruit women with moderate G6PD levels, but only one participant met this criterion – all others had normal G6PD activity.

Patients received 3-day course of chloroquine and were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to either tafenoquine or primaquine at the same doses as in the DETECTIVE trial.

At 6 months, 2% (95% CI, 1%-6%) of tafenoquine recipients and 1% (95% CI, 0.2%-6%) of primaquine recipients had decreased hemoglobin levels, but none consequently needed treatment. The medications also caused a similar degree and time course of hemoglobin decrease, the investigators noted.

A meta-analysis of GATHER and DETECTIVE confirmed that tafenoquine more often led to a decreased hemoglobin level (4% versus 1.5% with primaquine). Tafenoquine also did not meet prespecified criteria for noninferiority compared with primaquine, with respective 6-month recurrence rates of 67% versus 73%.

However, GATHER deployed “extensive” support to help patients adhere to the 15-day primaquine course, Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and his colleagues wrote. “Without such interventions, adherence to primaquine has been reported to be as low as 24% in Southeast Asia, with a corresponding attenuation of efficacy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Medicines for Malaria Venture funded both studies, and GSK funded and conducted the meta-analysis. Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and several coinvestigators reported ties to GSK, Medicines for Malaria Venture, the Gambia, and LSTMH. Dr. Lacerda reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Lacerda MVG et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:215-28, and Llanos-Cuentas A et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:229-41.

The studies show that tafenoquine reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax recurrence in patients with quantitatively confirmed normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, Nicholas J. White, FRS, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But the need for this test and current prescribing restrictions will “limit the potential deployment of tafenoquine, at least in the immediate future,” he said. He praised the developers of tafenoquine “for persevering with this potentially valuable antimalarial drug, despite the difficulties,” but cautioned that it’s too soon to conclude that tafenoquine can be used safely and routinely on a large scale “and thus fulfill its promise as a radical improvement in the treatment of malaria.”

Currently, tafenoquine may not be used during pregnancy, lactation, or in patients younger than 16 years, Dr. White noted. Tafenoquine, like primaquine, causes dose-dependent hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency, but unlike primaquine, it is given as a single large dose. Hence, pretreatment quantitative G6PD testing is necessary. Point-of-care quantitative G6PD tests have been developed but await extensive field testing, Dr. White said.

Dr. White is with Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, and University of Oxford, England. He reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are from his accompanying editorial ( N Engl J Med. 2019;380:285-6 ).

The studies show that tafenoquine reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax recurrence in patients with quantitatively confirmed normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, Nicholas J. White, FRS, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But the need for this test and current prescribing restrictions will “limit the potential deployment of tafenoquine, at least in the immediate future,” he said. He praised the developers of tafenoquine “for persevering with this potentially valuable antimalarial drug, despite the difficulties,” but cautioned that it’s too soon to conclude that tafenoquine can be used safely and routinely on a large scale “and thus fulfill its promise as a radical improvement in the treatment of malaria.”

Currently, tafenoquine may not be used during pregnancy, lactation, or in patients younger than 16 years, Dr. White noted. Tafenoquine, like primaquine, causes dose-dependent hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency, but unlike primaquine, it is given as a single large dose. Hence, pretreatment quantitative G6PD testing is necessary. Point-of-care quantitative G6PD tests have been developed but await extensive field testing, Dr. White said.

Dr. White is with Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, and University of Oxford, England. He reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are from his accompanying editorial ( N Engl J Med. 2019;380:285-6 ).

The studies show that tafenoquine reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax recurrence in patients with quantitatively confirmed normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, Nicholas J. White, FRS, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But the need for this test and current prescribing restrictions will “limit the potential deployment of tafenoquine, at least in the immediate future,” he said. He praised the developers of tafenoquine “for persevering with this potentially valuable antimalarial drug, despite the difficulties,” but cautioned that it’s too soon to conclude that tafenoquine can be used safely and routinely on a large scale “and thus fulfill its promise as a radical improvement in the treatment of malaria.”

Currently, tafenoquine may not be used during pregnancy, lactation, or in patients younger than 16 years, Dr. White noted. Tafenoquine, like primaquine, causes dose-dependent hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency, but unlike primaquine, it is given as a single large dose. Hence, pretreatment quantitative G6PD testing is necessary. Point-of-care quantitative G6PD tests have been developed but await extensive field testing, Dr. White said.

Dr. White is with Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, and University of Oxford, England. He reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are from his accompanying editorial ( N Engl J Med. 2019;380:285-6 ).

Single-dose tafenoquine therapy safely reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax relapse in patients with normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, according to the results of two phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials.

Findings from both studies were published in two separate reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the first study, the Dose and Efficacy Trial Evaluating Chloroquine and Tafenoquine in Vivax Elimination (DETECTIVE), the risk of P. vivax recurrence was approximately 70% lower with tafenoquine versus placebo, wrote Marcus V.G. Lacerda, MD, of Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado in Manaus, Brazil, and his colleagues.

The study included 522 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Patients received 3 days of chloroquine therapy (600 mg on days 1 and 2, and 300 mg on day 3) and were randomly assigned on a 2:1:1 basis to receive a single 300-mg dose of tafenoquine on day 1 or 2, primaquine once daily for 14 days, or placebo.

Since primaquine and tafenoquine can cause clinically significant hemolysis in individuals with G6PD deficiency, the study included only patients with normal G6PD activity.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 62% of tafenoquine recipients were free from P. vivax recurrence (95% confidence interval [CI], 55%-69%) at 6 months, as were 70% of primaquine recipients (95% CI, 60%-77%) and 28% of placebo recipients (95% CI, 20%-37%). Compared with placebo, the reduction in risk of recurrence was 70% with tafenoquine (hazard ratio [HR], 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22-0.40; P less than .001) and 74% with primaquine.

Declines in hemoglobin levels were greatest in the tafenoquine group but were not associated with symptomatic anemia and resolved without intervention, the investigators wrote.

In addition to the quantitative G6PD test, the investigators also evaluated a qualitative test, which “failed to identify 16 patients most at risk for hemolysis,” they reported. “If tafenoquine use is expanded, adoption of reliable quantitative point-of-care G6PD tests will be needed; such tests are not currently available but are in development.”

In the second study, Global Assessment of Tafenoquine Hemolytic Risk (GATHER), Alejandro Llanos-Cuentas, MD, of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, and his colleagues enrolled 251 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Columbia, Vietnam, and Thailand. They attempted to recruit women with moderate G6PD levels, but only one participant met this criterion – all others had normal G6PD activity.

Patients received 3-day course of chloroquine and were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to either tafenoquine or primaquine at the same doses as in the DETECTIVE trial.

At 6 months, 2% (95% CI, 1%-6%) of tafenoquine recipients and 1% (95% CI, 0.2%-6%) of primaquine recipients had decreased hemoglobin levels, but none consequently needed treatment. The medications also caused a similar degree and time course of hemoglobin decrease, the investigators noted.

A meta-analysis of GATHER and DETECTIVE confirmed that tafenoquine more often led to a decreased hemoglobin level (4% versus 1.5% with primaquine). Tafenoquine also did not meet prespecified criteria for noninferiority compared with primaquine, with respective 6-month recurrence rates of 67% versus 73%.

However, GATHER deployed “extensive” support to help patients adhere to the 15-day primaquine course, Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and his colleagues wrote. “Without such interventions, adherence to primaquine has been reported to be as low as 24% in Southeast Asia, with a corresponding attenuation of efficacy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Medicines for Malaria Venture funded both studies, and GSK funded and conducted the meta-analysis. Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and several coinvestigators reported ties to GSK, Medicines for Malaria Venture, the Gambia, and LSTMH. Dr. Lacerda reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Lacerda MVG et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:215-28, and Llanos-Cuentas A et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:229-41.

Single-dose tafenoquine therapy safely reduces the risk of Plasmodium vivax relapse in patients with normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity, according to the results of two phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials.

Findings from both studies were published in two separate reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the first study, the Dose and Efficacy Trial Evaluating Chloroquine and Tafenoquine in Vivax Elimination (DETECTIVE), the risk of P. vivax recurrence was approximately 70% lower with tafenoquine versus placebo, wrote Marcus V.G. Lacerda, MD, of Fundação de Medicina Tropical Doutor Heitor Vieira Dourado in Manaus, Brazil, and his colleagues.

The study included 522 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Patients received 3 days of chloroquine therapy (600 mg on days 1 and 2, and 300 mg on day 3) and were randomly assigned on a 2:1:1 basis to receive a single 300-mg dose of tafenoquine on day 1 or 2, primaquine once daily for 14 days, or placebo.

Since primaquine and tafenoquine can cause clinically significant hemolysis in individuals with G6PD deficiency, the study included only patients with normal G6PD activity.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 62% of tafenoquine recipients were free from P. vivax recurrence (95% confidence interval [CI], 55%-69%) at 6 months, as were 70% of primaquine recipients (95% CI, 60%-77%) and 28% of placebo recipients (95% CI, 20%-37%). Compared with placebo, the reduction in risk of recurrence was 70% with tafenoquine (hazard ratio [HR], 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22-0.40; P less than .001) and 74% with primaquine.

Declines in hemoglobin levels were greatest in the tafenoquine group but were not associated with symptomatic anemia and resolved without intervention, the investigators wrote.

In addition to the quantitative G6PD test, the investigators also evaluated a qualitative test, which “failed to identify 16 patients most at risk for hemolysis,” they reported. “If tafenoquine use is expanded, adoption of reliable quantitative point-of-care G6PD tests will be needed; such tests are not currently available but are in development.”

In the second study, Global Assessment of Tafenoquine Hemolytic Risk (GATHER), Alejandro Llanos-Cuentas, MD, of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, and his colleagues enrolled 251 patients with confirmed P. vivax infection from Peru, Brazil, Columbia, Vietnam, and Thailand. They attempted to recruit women with moderate G6PD levels, but only one participant met this criterion – all others had normal G6PD activity.

Patients received 3-day course of chloroquine and were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to either tafenoquine or primaquine at the same doses as in the DETECTIVE trial.

At 6 months, 2% (95% CI, 1%-6%) of tafenoquine recipients and 1% (95% CI, 0.2%-6%) of primaquine recipients had decreased hemoglobin levels, but none consequently needed treatment. The medications also caused a similar degree and time course of hemoglobin decrease, the investigators noted.

A meta-analysis of GATHER and DETECTIVE confirmed that tafenoquine more often led to a decreased hemoglobin level (4% versus 1.5% with primaquine). Tafenoquine also did not meet prespecified criteria for noninferiority compared with primaquine, with respective 6-month recurrence rates of 67% versus 73%.

However, GATHER deployed “extensive” support to help patients adhere to the 15-day primaquine course, Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and his colleagues wrote. “Without such interventions, adherence to primaquine has been reported to be as low as 24% in Southeast Asia, with a corresponding attenuation of efficacy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Medicines for Malaria Venture funded both studies, and GSK funded and conducted the meta-analysis. Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and several coinvestigators reported ties to GSK, Medicines for Malaria Venture, the Gambia, and LSTMH. Dr. Lacerda reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Lacerda MVG et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:215-28, and Llanos-Cuentas A et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:229-41.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In DETECTIVE, 6-month rates of freedom from recurrence from Plasmodium vivax infection were 62% with tafenoquine, 70% with primaquine, and 28% with placebo.

Study details: Two randomized, phase 3, double-blind controlled trials of patients with confirmed P. vivax infection (DETECTIVE and GATHER) and without deficient G6PD activity.

Disclosures: GlaxoSmithKline and Medicines for Malaria Venture funded both studies, and GSK funded and conducted the meta-analysis. Dr. Llanos-Cuentas and several coinvestigators reported ties to GSK, Medicines for Malaria Venture, the Gambia, and LSTMH. Dr. Lacerda reported having financial disclosures.

Source: Lacerda MVG et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:215-28, and Llanos-Cuentas A et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:229-41.

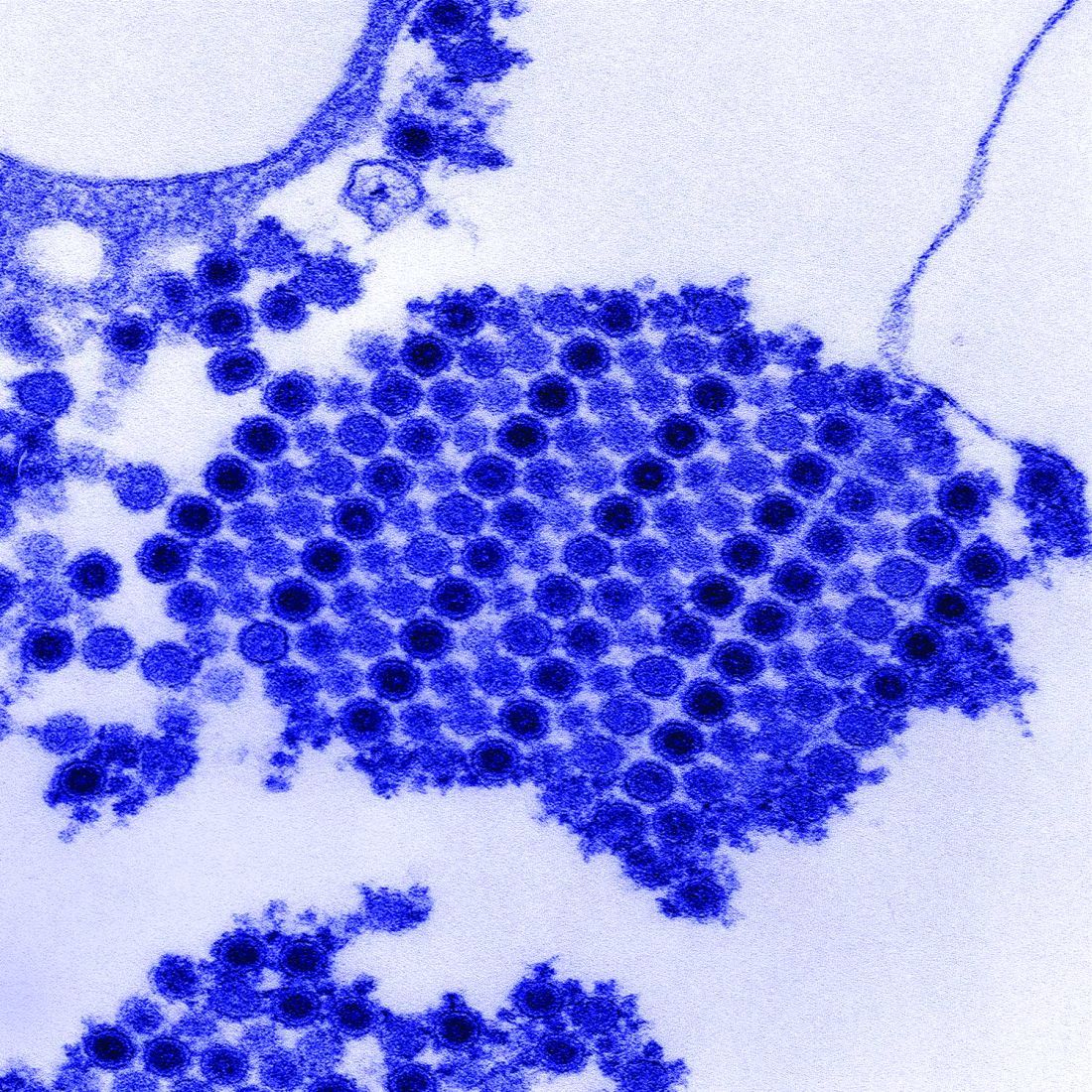

Puppy bite at yoga retreat leads to rabies death: Prompts health warning

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point: depending on length of trip, location, and activities involved.

Major finding: A Virginia woman died after sustaining a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Study details: Case report including details of the 65-year-old woman’s trip, rabies exposure, symptoms, diagnosis, and eventual death.

Disclosures: Authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

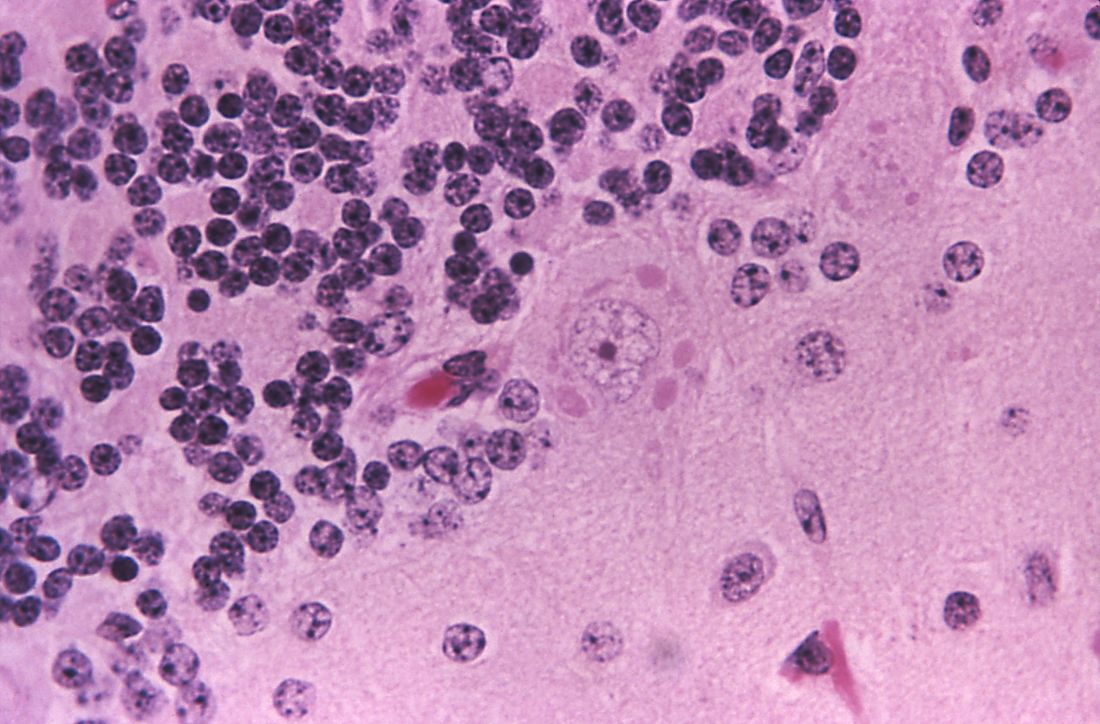

Methotrexate relieves pain of Chikungunya-associated arthritis

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

Methotrexate is effective for the control of pain produced by arthritis associated with Chikungunya virus infection, according to a retrospective review of outcomes in a series of 50 patients.

Joint pain and joint inflammation are commonly seen in the approximately 60% of patients who progress to the chronic phase of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, but there is no current consensus about how best to manage this complication, according to first author J. Kennedy Amaral, MD, of the department of infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the University of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and his colleagues, who published their experience in 50 patients in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.

In this study, the primary measure of efficacy was pain control because not all CHIKV infection patients with rheumatic symptoms demonstrate synovitis on radiological examination. The 50 patients included in this series all had joint symptoms persisting more than 12 weeks after onset of CHIKV infection.

All but four of the patients in this series were women. The mean age was 61.9 years. At baseline, 28 had a musculoskeletal disorder defined by presence of arthralgia, 11 had rheumatoid arthritis, seven had fibromyalgia, and four had undifferentiated polyarthritis.

On a 0-10 visual analog scale (VAS), the mean pain score at baseline was 7.7. All patients were initiated on a 4-week course of 7.5 mg of methotrexate administered with folic acid.

Four patients not examined after 4 weeks of treatment were excluded from analysis. Of those evaluated, 80% had achieved at least a 2-point reduction in VAS score, which is considered clinically meaningful. The mean reduction in VAS pain score at 4 weeks was 4.3 points (P less than .0001 vs. baseline). In 12 patients, symptoms were resolved, and they were not further evaluated.

Those with inadequate pain control at 4 weeks were permitted to begin a higher dose of methotrexate and to receive additional therapies. At 8 weeks, the reduction in VAS pain score was only modestly increased, reaching a mean 4.5-point reduction from baseline on a mean methotrexate dose of 9.2 mg/week. A substantial proportion of patients had added other medications, such as prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Only 20 patients had joint swelling and frank arthritis at baseline. In these, the mean swollen joint count decreased from 7.15 to 2.89 (P less than .0001). There was no further reduction at 8 weeks.

Over the course of the study, there was no evidence that methotrexate exacerbated CHIKV infection.

The data were collected retrospectively, and there was no control group, but the findings inform practitioners of the “possible benefit of low-dose methotrexate to treat both arthralgia and arthritis” in chronic CHIK-associated arthritis, according to Dr. Amaral and his coinvestigators.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On a 10-point visual analog scale, the pain reduction from baseline on methotrexate at 8 weeks was 4.5 (P less than .0001).

Study details: Retrospective observational study.

Disclosures: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Amaral JK et al. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000943

FDA approves rifamycin for treatment of traveler’s diarrhea

The Food and Drug Administration has approved rifamycin (Aemcolo) for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea caused by noninvasive strains of Escherichia coli.

FDA approval was based on results of three clinical trials. The efficacy of rifamycin was shown in a trial of 264 adults with traveler’s diarrhea in Guatemala and Mexico. Compared with placebo, rifamycin significantly reduced symptoms of the condition. The safety of rifamycin was illustrated in a pair of studies including 619 adults with traveler’s diarrhea who took rifamycin orally for 3-4 days. The most common adverse events were headache and constipation.

Traveler’s diarrhea is the most common travel-related illness, affecting 10%-40% of travelers. It can be caused by a multitude of pathogens, but bacteria from food or water is the most common source. High-risk areas include much of Asia, the Middle East, Mexico, Central and South America, and Africa.

Rifamycin was not effective in patients with diarrhea complicated by fever and/or bloody stool or in diarrhea caused by a pathogen other than E. coli.

“Travelers’ diarrhea affects millions of people each year, and having treatment options for this condition can help reduce symptoms of the condition,” Edward Cox, MD, MPH, director of the Office of Antimicrobial Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved rifamycin (Aemcolo) for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea caused by noninvasive strains of Escherichia coli.

FDA approval was based on results of three clinical trials. The efficacy of rifamycin was shown in a trial of 264 adults with traveler’s diarrhea in Guatemala and Mexico. Compared with placebo, rifamycin significantly reduced symptoms of the condition. The safety of rifamycin was illustrated in a pair of studies including 619 adults with traveler’s diarrhea who took rifamycin orally for 3-4 days. The most common adverse events were headache and constipation.