User login

Functional Knee Outcomes in Infrapatellar and Suprapatellar Tibial Nailing: Does Approach Matter?

With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

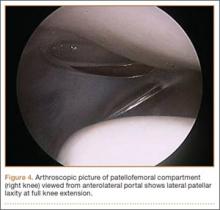

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results

We identified 176 patients who had the CPT code for intramedullary fixation of a tibial shaft fracture between January 2009 and February 2013. After analysis of radiographs and medical records, 82 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-six (45%) of the original 82 patients were lost to follow-up after attempts to contact them by telephone. One patient refused to participate in the study. Twenty-four patients underwent traditional infrapatellar nailing, and 21 patients had a suprapatellar nail placed with approach-specific instrumentation. Nine patients had an open fracture. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, mechanism of injury, or operative time (Table 1). There was also no difference (P = .210) in fracture location between groups (0 proximal-third, 14 midshaft, 10 distal-third vs 3 proximal-third, 10 midshaft, 8 distal-third). Mean age was 37.6 years (range, 20-65 years) for the infrapatellar group and 38.5 years (range, 18-68 years) for the suprapatellar group (P = .839). Mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) shorter for the suprapatellar group (12 mo; range, 3-33 mo) than for the infrapatellar group (25 mo; range, 4-43 mo).

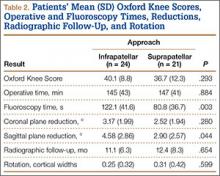

Mean OKS (maximum, 48 points) was 40.1 (range, 11-48) for the infrapatellar group and 36.7 (range, 2-48) for the suprapatellar group (P = .293). Table 2 summarizes the data. Radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane was improved (P = .044) in the suprapatellar group (2.90°) compared with the infrapatellar group (4.58°). There was no difference in rotational malreduction (0.31 vs 0.25 cortical width; P = .599) or in reduction in the coronal plane (2.52° vs 3.17°; P = .280). All patients in both groups maintained radiographic reduction within 5° in any plane throughout follow-up. There was no difference (P = .654) in radiographic follow-up between the infrapatellar group (11 mo) and the suprapatellar group (12 mo). The 1 nonunion in the suprapatellar group required return to the operating room for exchange intramedullary nailing. The suprapatellar approach required less (P = .003) operative fluoroscopy time (80.8 s; range, 46-180 s) than the standard infrapatellar approach (122.1 s; range, 71-240 s). Two patients in the suprapatellar group and 8 in the infrapatellar group did not have their fluoroscopy time recorded in the operative report.

Discussion

We have described the first retrospective cohort-comparison study of functional knee scores associated with traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing. Although much has been written about the incidence of anterior knee pain with use of a patellar splitting or parapatellar approach, the clinical effects of knee pain after use of suprapatellar nails are yet to be addressed. In a cadaveric study, Gelbke and colleagues14 found higher mean patellofemoral pressures and higher peak contact pressures with a suprapatellar approach. These numbers, however, were still far below the threshold for chondrocyte damage, and that study is yet to be clinically validated. Our data showed no difference in OKS between the 2 groups. Despite being intra-articular, approach-specific instrumentation may protect the trochlea and patellar cartilage.

Although the OKS questionnaire was originally developed and widely validated to describe clinical outcomes of total knee arthroplasty,15,16 it has also been evaluated for other interventions, including viscosupplementation injections17 and high tibial osteotomy.18 We used the OKS questionnaire in our study because it is simple to administer by telephone and is not as cumbersome as the Knee Society Score or the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. It is also more specific to the knee than generalized outcome measures used in trauma, such as the Short Form 36 (SF-36). Sanders and colleagues19 reported excellent tibial alignment, radiographic union, and knee range of motion using semi-extended tibial nailing with a suprapatellar approach. For outcome measures, they used the Lysholm Knee Score and the SF-36. Our clinical and radiographic results confirmed their finding—that the semi-extended suprapatellar approach is an option for tibial nailing.

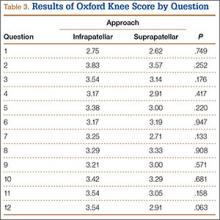

OKS results by question (Table 3) showed that the infrapatellar group had less pain walking down stairs. This result approached statistical significance (P = .063). As surgeons at our institution began using the suprapatellar approach only during the final 2 years of the study period, mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) less than for the infrapatellar group (12 vs 25 mo). Although there was no statistically significant difference in reduction quality on anteroposterior radiographs, the suprapatellar approach had improved (P = .044) reduction on lateral radiographs (2.90° vs 4.58°).

Although operative time did not differ between our 2 groups, significantly (P = .003) less fluoroscopy time was required for suprapatellar nails (80.8 s) than for infrapatellar nails (122.1 s). Positioning the knee in the semi-extended position offers easier access for fluoroscopy and less radiation exposure for the patient. Placing the nail in extension also helps eliminate the deforming forces that cause malreduction of proximal tibial shaft or segmental fractures. However, our study was limited in that only 2 surgeons at our institution used the suprapatellar approach, and both were fellowship-trained in orthopedic traumatology. This situation could have introduced bias into the interpretation of fluoroscopy data, as these surgeons may have been more comfortable with the procedure and less likely to use fluoroscopy. Both surgeons also performed infrapatellar nailing during the study period, and there was no statistical difference in fracture patterns between the groups, thus minimizing bias.

This study was retrospective but had several strengths. Sample size met the prestudy power analysis to determine a minimally clinically important difference in OKS results. The investigator who administered the telephone survey was blinded to surgical approach. This study was also the first clinical study to compare outcomes of infrapatellar and suprapatellar nailing. However, the study’s follow-up rate was a weakness. The patient population at our academic, urban, level I trauma center is transient. We lost 36 patients (45%) to follow-up; their telephone numbers in the hospital records likely changed since surgery, and we could not contact these patients.

Conclusion

Our retrospective cohort study found no difference in OKS between traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing for diaphyseal tibia fractures. Suprapatellar nails require less fluoroscopy time and may show improved radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane. Although further study is needed, the suprapatellar entry portal appears to be a safe alternative for tibial nailing with use of appropriate instrumentation.

1. Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1992.

2. Bone LB, Sucato D, Stegemann PM, Rohrbacher BJ. Displaced isolated fractures of the tibial shaft treated with either a cast or intramedullary nailing. An outcome analysis of matched pairs of patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(9):1336-1341.

3. Hooper GJ, Keddell RG, Penny ID. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(1):83-85.

4. Alho A, Benterud JG, Høgevold HE, Ekeland A, Strømsøe K. Comparison of functional bracing and locked intramedullary nailing in the treatment of displaced tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(277):243-250.

5. Ricci WM, O’Boyle M, Borrelli J, Bellabarba C, Sanders R. Fractures of the proximal third of the tibial shaft treated with intramedullary nails and blocking screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(4):264-270.

6. Tornetta P 3rd, Collins E. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(328):185-189.

7. Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(2):103-105.

8. Toivanen JA, Väistö O, Kannus P, Latvala K, Honkonen SE, Järvinen MJ. Anterior knee pain after intramedullary nailing of fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study comparing two different nail-insertion techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(4):580-585.

9. Morandi M, Banka T, Gairarsa GP, et al. Intramedullary nailing of tibial fractures: review of surgical techniques and description of a percutaneous lateral suprapatellar approach. Orthopaedics. 2010;33(3):172-179.

10. Bohm ER, Loucks L, Tan QE, et al. Determining minimum clinically important difference and targeted clinical improvement values for the Oxford 12. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2012; San Francisco, CA.

11. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11(2):116-128.

12. Streit MR, Walker T, Bruckner T, et al. Mobile-bearing lateral unicompartmental knee replacement with the Oxford domed tibial component: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(10):1356-1361.

13. Jenny JY, Diesinger Y. The Oxford Knee Score: compared performance before and after knee replacement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4):409-412.

14. Gelbke MK, Coombs D, Powell S, et al. Suprapatellar versus infra-patellar intramedullary nail insertion of the tibia: a cadaveric model for comparison of patellofemoral contact pressures and forces. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(11):665-671.

15. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63-69.

16. Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L. Translation and validation of the Oxford-12 item knee score for use in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):268-274.

17. Clarke S, Lock V, Duddy J, Sharif M, Newman JH, Kirwan JR. Intra-articular hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) in the management of patellofemoral osteoarthritis of the knee (POAK). Knee. 2005;12(1):57-62.

18. Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(382):154-167.

19. Sanders RW, DiPasquale TG, Jordan CJ, Arrington JA, Sagi HC. Semiextended intramedullary nailing of the tibia using a suprapatellar approach: radiographic results and clinical outcomes at a minimum of 12 months follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(suppl 8):S29-S39.

With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results

We identified 176 patients who had the CPT code for intramedullary fixation of a tibial shaft fracture between January 2009 and February 2013. After analysis of radiographs and medical records, 82 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-six (45%) of the original 82 patients were lost to follow-up after attempts to contact them by telephone. One patient refused to participate in the study. Twenty-four patients underwent traditional infrapatellar nailing, and 21 patients had a suprapatellar nail placed with approach-specific instrumentation. Nine patients had an open fracture. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, mechanism of injury, or operative time (Table 1). There was also no difference (P = .210) in fracture location between groups (0 proximal-third, 14 midshaft, 10 distal-third vs 3 proximal-third, 10 midshaft, 8 distal-third). Mean age was 37.6 years (range, 20-65 years) for the infrapatellar group and 38.5 years (range, 18-68 years) for the suprapatellar group (P = .839). Mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) shorter for the suprapatellar group (12 mo; range, 3-33 mo) than for the infrapatellar group (25 mo; range, 4-43 mo).

Mean OKS (maximum, 48 points) was 40.1 (range, 11-48) for the infrapatellar group and 36.7 (range, 2-48) for the suprapatellar group (P = .293). Table 2 summarizes the data. Radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane was improved (P = .044) in the suprapatellar group (2.90°) compared with the infrapatellar group (4.58°). There was no difference in rotational malreduction (0.31 vs 0.25 cortical width; P = .599) or in reduction in the coronal plane (2.52° vs 3.17°; P = .280). All patients in both groups maintained radiographic reduction within 5° in any plane throughout follow-up. There was no difference (P = .654) in radiographic follow-up between the infrapatellar group (11 mo) and the suprapatellar group (12 mo). The 1 nonunion in the suprapatellar group required return to the operating room for exchange intramedullary nailing. The suprapatellar approach required less (P = .003) operative fluoroscopy time (80.8 s; range, 46-180 s) than the standard infrapatellar approach (122.1 s; range, 71-240 s). Two patients in the suprapatellar group and 8 in the infrapatellar group did not have their fluoroscopy time recorded in the operative report.

Discussion

We have described the first retrospective cohort-comparison study of functional knee scores associated with traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing. Although much has been written about the incidence of anterior knee pain with use of a patellar splitting or parapatellar approach, the clinical effects of knee pain after use of suprapatellar nails are yet to be addressed. In a cadaveric study, Gelbke and colleagues14 found higher mean patellofemoral pressures and higher peak contact pressures with a suprapatellar approach. These numbers, however, were still far below the threshold for chondrocyte damage, and that study is yet to be clinically validated. Our data showed no difference in OKS between the 2 groups. Despite being intra-articular, approach-specific instrumentation may protect the trochlea and patellar cartilage.

Although the OKS questionnaire was originally developed and widely validated to describe clinical outcomes of total knee arthroplasty,15,16 it has also been evaluated for other interventions, including viscosupplementation injections17 and high tibial osteotomy.18 We used the OKS questionnaire in our study because it is simple to administer by telephone and is not as cumbersome as the Knee Society Score or the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. It is also more specific to the knee than generalized outcome measures used in trauma, such as the Short Form 36 (SF-36). Sanders and colleagues19 reported excellent tibial alignment, radiographic union, and knee range of motion using semi-extended tibial nailing with a suprapatellar approach. For outcome measures, they used the Lysholm Knee Score and the SF-36. Our clinical and radiographic results confirmed their finding—that the semi-extended suprapatellar approach is an option for tibial nailing.

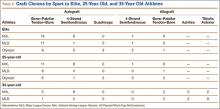

OKS results by question (Table 3) showed that the infrapatellar group had less pain walking down stairs. This result approached statistical significance (P = .063). As surgeons at our institution began using the suprapatellar approach only during the final 2 years of the study period, mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) less than for the infrapatellar group (12 vs 25 mo). Although there was no statistically significant difference in reduction quality on anteroposterior radiographs, the suprapatellar approach had improved (P = .044) reduction on lateral radiographs (2.90° vs 4.58°).

Although operative time did not differ between our 2 groups, significantly (P = .003) less fluoroscopy time was required for suprapatellar nails (80.8 s) than for infrapatellar nails (122.1 s). Positioning the knee in the semi-extended position offers easier access for fluoroscopy and less radiation exposure for the patient. Placing the nail in extension also helps eliminate the deforming forces that cause malreduction of proximal tibial shaft or segmental fractures. However, our study was limited in that only 2 surgeons at our institution used the suprapatellar approach, and both were fellowship-trained in orthopedic traumatology. This situation could have introduced bias into the interpretation of fluoroscopy data, as these surgeons may have been more comfortable with the procedure and less likely to use fluoroscopy. Both surgeons also performed infrapatellar nailing during the study period, and there was no statistical difference in fracture patterns between the groups, thus minimizing bias.

This study was retrospective but had several strengths. Sample size met the prestudy power analysis to determine a minimally clinically important difference in OKS results. The investigator who administered the telephone survey was blinded to surgical approach. This study was also the first clinical study to compare outcomes of infrapatellar and suprapatellar nailing. However, the study’s follow-up rate was a weakness. The patient population at our academic, urban, level I trauma center is transient. We lost 36 patients (45%) to follow-up; their telephone numbers in the hospital records likely changed since surgery, and we could not contact these patients.

Conclusion

Our retrospective cohort study found no difference in OKS between traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing for diaphyseal tibia fractures. Suprapatellar nails require less fluoroscopy time and may show improved radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane. Although further study is needed, the suprapatellar entry portal appears to be a safe alternative for tibial nailing with use of appropriate instrumentation.

With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results

We identified 176 patients who had the CPT code for intramedullary fixation of a tibial shaft fracture between January 2009 and February 2013. After analysis of radiographs and medical records, 82 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-six (45%) of the original 82 patients were lost to follow-up after attempts to contact them by telephone. One patient refused to participate in the study. Twenty-four patients underwent traditional infrapatellar nailing, and 21 patients had a suprapatellar nail placed with approach-specific instrumentation. Nine patients had an open fracture. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, mechanism of injury, or operative time (Table 1). There was also no difference (P = .210) in fracture location between groups (0 proximal-third, 14 midshaft, 10 distal-third vs 3 proximal-third, 10 midshaft, 8 distal-third). Mean age was 37.6 years (range, 20-65 years) for the infrapatellar group and 38.5 years (range, 18-68 years) for the suprapatellar group (P = .839). Mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) shorter for the suprapatellar group (12 mo; range, 3-33 mo) than for the infrapatellar group (25 mo; range, 4-43 mo).

Mean OKS (maximum, 48 points) was 40.1 (range, 11-48) for the infrapatellar group and 36.7 (range, 2-48) for the suprapatellar group (P = .293). Table 2 summarizes the data. Radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane was improved (P = .044) in the suprapatellar group (2.90°) compared with the infrapatellar group (4.58°). There was no difference in rotational malreduction (0.31 vs 0.25 cortical width; P = .599) or in reduction in the coronal plane (2.52° vs 3.17°; P = .280). All patients in both groups maintained radiographic reduction within 5° in any plane throughout follow-up. There was no difference (P = .654) in radiographic follow-up between the infrapatellar group (11 mo) and the suprapatellar group (12 mo). The 1 nonunion in the suprapatellar group required return to the operating room for exchange intramedullary nailing. The suprapatellar approach required less (P = .003) operative fluoroscopy time (80.8 s; range, 46-180 s) than the standard infrapatellar approach (122.1 s; range, 71-240 s). Two patients in the suprapatellar group and 8 in the infrapatellar group did not have their fluoroscopy time recorded in the operative report.

Discussion

We have described the first retrospective cohort-comparison study of functional knee scores associated with traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing. Although much has been written about the incidence of anterior knee pain with use of a patellar splitting or parapatellar approach, the clinical effects of knee pain after use of suprapatellar nails are yet to be addressed. In a cadaveric study, Gelbke and colleagues14 found higher mean patellofemoral pressures and higher peak contact pressures with a suprapatellar approach. These numbers, however, were still far below the threshold for chondrocyte damage, and that study is yet to be clinically validated. Our data showed no difference in OKS between the 2 groups. Despite being intra-articular, approach-specific instrumentation may protect the trochlea and patellar cartilage.

Although the OKS questionnaire was originally developed and widely validated to describe clinical outcomes of total knee arthroplasty,15,16 it has also been evaluated for other interventions, including viscosupplementation injections17 and high tibial osteotomy.18 We used the OKS questionnaire in our study because it is simple to administer by telephone and is not as cumbersome as the Knee Society Score or the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. It is also more specific to the knee than generalized outcome measures used in trauma, such as the Short Form 36 (SF-36). Sanders and colleagues19 reported excellent tibial alignment, radiographic union, and knee range of motion using semi-extended tibial nailing with a suprapatellar approach. For outcome measures, they used the Lysholm Knee Score and the SF-36. Our clinical and radiographic results confirmed their finding—that the semi-extended suprapatellar approach is an option for tibial nailing.

OKS results by question (Table 3) showed that the infrapatellar group had less pain walking down stairs. This result approached statistical significance (P = .063). As surgeons at our institution began using the suprapatellar approach only during the final 2 years of the study period, mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) less than for the infrapatellar group (12 vs 25 mo). Although there was no statistically significant difference in reduction quality on anteroposterior radiographs, the suprapatellar approach had improved (P = .044) reduction on lateral radiographs (2.90° vs 4.58°).

Although operative time did not differ between our 2 groups, significantly (P = .003) less fluoroscopy time was required for suprapatellar nails (80.8 s) than for infrapatellar nails (122.1 s). Positioning the knee in the semi-extended position offers easier access for fluoroscopy and less radiation exposure for the patient. Placing the nail in extension also helps eliminate the deforming forces that cause malreduction of proximal tibial shaft or segmental fractures. However, our study was limited in that only 2 surgeons at our institution used the suprapatellar approach, and both were fellowship-trained in orthopedic traumatology. This situation could have introduced bias into the interpretation of fluoroscopy data, as these surgeons may have been more comfortable with the procedure and less likely to use fluoroscopy. Both surgeons also performed infrapatellar nailing during the study period, and there was no statistical difference in fracture patterns between the groups, thus minimizing bias.

This study was retrospective but had several strengths. Sample size met the prestudy power analysis to determine a minimally clinically important difference in OKS results. The investigator who administered the telephone survey was blinded to surgical approach. This study was also the first clinical study to compare outcomes of infrapatellar and suprapatellar nailing. However, the study’s follow-up rate was a weakness. The patient population at our academic, urban, level I trauma center is transient. We lost 36 patients (45%) to follow-up; their telephone numbers in the hospital records likely changed since surgery, and we could not contact these patients.

Conclusion

Our retrospective cohort study found no difference in OKS between traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing for diaphyseal tibia fractures. Suprapatellar nails require less fluoroscopy time and may show improved radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane. Although further study is needed, the suprapatellar entry portal appears to be a safe alternative for tibial nailing with use of appropriate instrumentation.

1. Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1992.

2. Bone LB, Sucato D, Stegemann PM, Rohrbacher BJ. Displaced isolated fractures of the tibial shaft treated with either a cast or intramedullary nailing. An outcome analysis of matched pairs of patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(9):1336-1341.

3. Hooper GJ, Keddell RG, Penny ID. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(1):83-85.

4. Alho A, Benterud JG, Høgevold HE, Ekeland A, Strømsøe K. Comparison of functional bracing and locked intramedullary nailing in the treatment of displaced tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(277):243-250.

5. Ricci WM, O’Boyle M, Borrelli J, Bellabarba C, Sanders R. Fractures of the proximal third of the tibial shaft treated with intramedullary nails and blocking screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(4):264-270.

6. Tornetta P 3rd, Collins E. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(328):185-189.

7. Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(2):103-105.

8. Toivanen JA, Väistö O, Kannus P, Latvala K, Honkonen SE, Järvinen MJ. Anterior knee pain after intramedullary nailing of fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study comparing two different nail-insertion techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(4):580-585.

9. Morandi M, Banka T, Gairarsa GP, et al. Intramedullary nailing of tibial fractures: review of surgical techniques and description of a percutaneous lateral suprapatellar approach. Orthopaedics. 2010;33(3):172-179.

10. Bohm ER, Loucks L, Tan QE, et al. Determining minimum clinically important difference and targeted clinical improvement values for the Oxford 12. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2012; San Francisco, CA.

11. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11(2):116-128.

12. Streit MR, Walker T, Bruckner T, et al. Mobile-bearing lateral unicompartmental knee replacement with the Oxford domed tibial component: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(10):1356-1361.

13. Jenny JY, Diesinger Y. The Oxford Knee Score: compared performance before and after knee replacement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4):409-412.

14. Gelbke MK, Coombs D, Powell S, et al. Suprapatellar versus infra-patellar intramedullary nail insertion of the tibia: a cadaveric model for comparison of patellofemoral contact pressures and forces. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(11):665-671.

15. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63-69.

16. Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L. Translation and validation of the Oxford-12 item knee score for use in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):268-274.

17. Clarke S, Lock V, Duddy J, Sharif M, Newman JH, Kirwan JR. Intra-articular hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) in the management of patellofemoral osteoarthritis of the knee (POAK). Knee. 2005;12(1):57-62.

18. Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(382):154-167.

19. Sanders RW, DiPasquale TG, Jordan CJ, Arrington JA, Sagi HC. Semiextended intramedullary nailing of the tibia using a suprapatellar approach: radiographic results and clinical outcomes at a minimum of 12 months follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(suppl 8):S29-S39.

1. Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1992.

2. Bone LB, Sucato D, Stegemann PM, Rohrbacher BJ. Displaced isolated fractures of the tibial shaft treated with either a cast or intramedullary nailing. An outcome analysis of matched pairs of patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(9):1336-1341.

3. Hooper GJ, Keddell RG, Penny ID. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(1):83-85.

4. Alho A, Benterud JG, Høgevold HE, Ekeland A, Strømsøe K. Comparison of functional bracing and locked intramedullary nailing in the treatment of displaced tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(277):243-250.

5. Ricci WM, O’Boyle M, Borrelli J, Bellabarba C, Sanders R. Fractures of the proximal third of the tibial shaft treated with intramedullary nails and blocking screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(4):264-270.

6. Tornetta P 3rd, Collins E. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(328):185-189.

7. Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(2):103-105.

8. Toivanen JA, Väistö O, Kannus P, Latvala K, Honkonen SE, Järvinen MJ. Anterior knee pain after intramedullary nailing of fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study comparing two different nail-insertion techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(4):580-585.

9. Morandi M, Banka T, Gairarsa GP, et al. Intramedullary nailing of tibial fractures: review of surgical techniques and description of a percutaneous lateral suprapatellar approach. Orthopaedics. 2010;33(3):172-179.

10. Bohm ER, Loucks L, Tan QE, et al. Determining minimum clinically important difference and targeted clinical improvement values for the Oxford 12. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2012; San Francisco, CA.

11. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11(2):116-128.

12. Streit MR, Walker T, Bruckner T, et al. Mobile-bearing lateral unicompartmental knee replacement with the Oxford domed tibial component: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(10):1356-1361.

13. Jenny JY, Diesinger Y. The Oxford Knee Score: compared performance before and after knee replacement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4):409-412.

14. Gelbke MK, Coombs D, Powell S, et al. Suprapatellar versus infra-patellar intramedullary nail insertion of the tibia: a cadaveric model for comparison of patellofemoral contact pressures and forces. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(11):665-671.

15. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63-69.

16. Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L. Translation and validation of the Oxford-12 item knee score for use in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):268-274.

17. Clarke S, Lock V, Duddy J, Sharif M, Newman JH, Kirwan JR. Intra-articular hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) in the management of patellofemoral osteoarthritis of the knee (POAK). Knee. 2005;12(1):57-62.

18. Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(382):154-167.

19. Sanders RW, DiPasquale TG, Jordan CJ, Arrington JA, Sagi HC. Semiextended intramedullary nailing of the tibia using a suprapatellar approach: radiographic results and clinical outcomes at a minimum of 12 months follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(suppl 8):S29-S39.

Total Knee Arthroplasty in Hemophilic Arthropathy

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

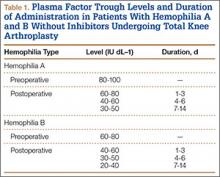

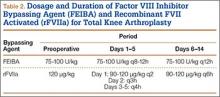

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

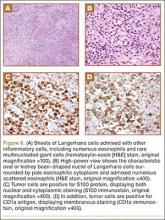

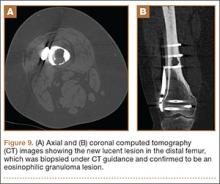

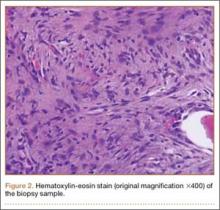

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Prosthetic survival rates with implant removal for any reason regarded as final endpoint was 92%. Causes of failure were prosthetic infection (6 cases, 6.8%) and loosening (2 cases, 2.2%). Of the 6 prosthetic infections, 5 were regarded as late and 1 as early. Late infections were successfully sorted by performing 2-stage revision TKA with the Constrained Condylar Knee (Zimmer). Acute infections were managed by open joint débridement and polyethylene exchange. Both cases of aseptic loosening of the TKA were successfully managed with 1-stage revision TKA using the same implant model (Figures 2A–2D).

Mean KSS Knee score improved from 79 before surgery to 36 after surgery, and mean KSS Function score improved from 63 to 33. KSS Pain score, which is included in the Knee score, 0 (no pain) to 50 (most severe pain), improved from 47 to 8. Patients receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-positive did not have poorer outcomes relative to those of patients not receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-negative. Patients with liver cirrhosis had a lower prosthetic survival rate and lower Knee scores.

Discussion

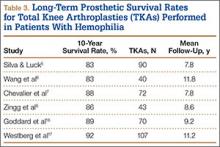

The prosthetic survival rate found in this study compares well with other reported rates for patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. However, evidence regarding long-term prosthesis survival in TKAs performed for patients with hemophilia is limited. Table 3 summarizes the main reported series of patients with hemophilia with 10-year prosthetic survival rates, number of TKAs performed, and mean follow-up period; in all these series, implant removal for any reason was regarded as the final endpoint.5-8,16,17 Mean follow-up in our study was 8 years. Clinical outcomes of TKA in patients with severe hemophilia and related disorders are expected to be inferior to those achieved in patients without a bleeding condition. The overall 10-year prosthetic survival rate for cemented TKA implants, as reported by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, was on the order of 93%.18 Mean age of our patients at time of surgery was only 38.2 years. TKAs performed in younger patients without a bleeding disorder have been associated with shorter implant survival times relative to those of elderly patients.19 Thus, Diduch and colleagues20 reported a prosthetic survival rate of 87% at 18 years in 108 TKAs performed on patients under age 55 years. Lonner and colleagues21 reported a better implant survival rate (90% at 8 years) in a series of patients under age 40 years (32 TKAs). In a study by Duffy and colleagues,22 the implant survival rate was 85% at 15 years in patients under age 55 years (74 TKAs). The results from our retrospective case assessment are quite similar to the overall prosthetic survival rates reported for TKAs performed on patients without hemophilia.

Rates of periprosthetic infection after primary TKA in patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions are much higher (up to 11%), with a mean infection rate of 6.2% (range, 1% to 11%), consistent with the rate found in our series of patients (6.8%)7,16,17,23,24 (Table 4). This rate is much higher than that reported after primary TKA in patients without hemophilia but is similar to some rates reported for patients with hemophilia. In our experience, most periprosthetic infections (5/6) were sorted as late.

Late infection is a major concern after TKA in patients with hemophilia, and various factors have been hypothesized as contributing to the high prevalence. An important factor is the high rate of HIV-positive patients among patients with hemophilia—which acts as a strong predisposing factor because of the often low CD4 counts and associated immune deficiency,25 but different reports have provided conflicting results in this respect.5,6,12 We found no relationship between HIV status and risk for periprosthetic infection, but conclusions are limited by the low number of HIV-positive patients in our series (14/74, 18.9%). Our patients’ late periprosthetic infections were diagnosed several years after TKA, suggesting hematogenous spread of infection. Most of these patients either were on regular prophylactic factor infusions or were being treated on demand, which might entail a risk for contamination of infusions by skin bacteria from the puncture site. Therefore, having an aseptic technique for administering coagulation factor concentrates is of paramount importance for patients with hemophilia and a knee implant.

Another important complication of TKA surgery is aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Aseptic loosening occurred in 2.2% of our patients, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere.11,26 Rates of this complication increase over follow-up, and some authors have linked this complication to TKA polyethylene wear.27 Development of a reactive and destructive bone–cement interface and microhemorrhages into such interface might be implicated in the higher rate of loosening observed among patients with hemophilia.28

In the present study, preoperative and postoperative functional outcomes differed significantly. A modest postoperative total ROM of 69º to 79º has been reported by several authors.5,6 Postoperative ROM may vary—may be slightly increased, remain unchanged, or may even be reduced.4,23,26 Even though little improvement in total ROM is achieved after TKA, many authors have reported reduced flexion contracture and hence an easier gait. However, along with functional improvement, dramatic pain relief after TKA is perhaps the most remarkable aspect, and it has a strong effect on patient satisfaction after surgery.5,7,8,18,23

Our study had 2 main limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series evaluation with the usual issues of potential inaccuracy of medical records and information bias. Second, the study did not include a control group.

Conclusion

The primary TKAs performed in our patients with hemophilia have had a good prosthetic survival rate. Even though such a result is slightly inferior to results in patients without hemophilia, our prosthetic survival rate is not significantly different from the rates reported in other, younger patient subsets. Late periprosthetic infections are a major concern, and taking precautions to avoid hematogenous spread of infections during factor concentrate infusions is strongly encouraged.

1. Arnold WD, Hilgartner MW. Hemophilic arthropathy. Current concepts of pathogenesis and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(3):287-305.

2. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Common orthopaedic problems in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 1999;5(suppl 1):53-60.

3. Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Glomstein A, et al. On-demand vs. prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia in Norway and Sweden: differences in treatment characteristics and outcome. Haemophilia. 2003;9(5):555-566.

4. Teigland JC, Tjønnfjord GE, Evensen SA, Charania B. Knee arthroplasty in hemophilia. 5-12 year follow-up of 15 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(2):153-156.

5. Silva M, Luck JV Jr. Long-term results of primary total knee replacement in patients with hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):85-91.

6. Wang K, Street A, Dowrick A, Liew S. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction following total joint replacement in haemophilia—23-year experience in knees, hips and elbows. Haemophilia. 2012;18(1):86-93.

7. Chevalier Y, Dargaud Y, Lienhart A, Chamouard V, Negrier C. Seventy-two total knee arthroplasties performed in patients with haemophilia using continuous infusion. Vox Sang. 2013;104(2):135-143.

8. Zingg PO, Fucentese SF, Lutz W, Brand B, Mamisch N, Koch PP. Haemophilic knee arthropathy: long-term outcome after total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(12):2465-2470.

9. Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Christiansen SE, Ingerslev J, Sneppen O. Total knee arthroplasty in classic hemophilia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(256):137-146.

10. Cohen I, Heim M, Martinowitz U, Chechick A. Orthopaedic outcome of total knee replacement in haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2000;6(2):104-109.

11. Fehily M, Fleming P, O’Shea E, Smith O, Smyth H. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with severe haemophilia. Int Orthop. 2002;26(2):89-91.

12. Legroux-Gérot I, Strouk G, Parquet A, Goodemand J, Gougeon F, Duquesnoy B. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(1):22-32.

13. Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):56-60.

14. Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):13-14.

15. Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(10):1434-1445.

16. Goddard NJ, Mann HA, Lee CA. Total knee replacement in patients with end-stage haemophilic arthropathy. 25-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(8):1085-1089.

17. Westberg M, Paus AC, Holme PA, Tjønnfjord GE. Haemophilic arthropathy: long-term outcomes in 107 primary total knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2014;21(1):147-150.

18. Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Failure of total knee arthroplasty with or without patella resurfacing. A study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register with 0-15 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):282-292.

19. Post M, Telfer MC. Surgery in hemophilic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(8):1136-1145.

20. Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients. Long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(4):575-582.

21. Lonner JH, Hershman S, Mont M, Lotke PA. Total knee arthroplasty in patients 40 years of age and younger with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(380):85-90.

22. Duffy GP, Crowder AR, Trousdale RR, Berry DJ. Cemented total knee arthroplasty using a modern prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):67-70.

23. Chiang CC, Chen PQ, Shen MC, Tsai W. Total knee arthroplasty for severe haemophilic arthropathy: long-term experience in Taiwan. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):828-834.

24. Solimeno LP, Mancuso ME, Pasta G, Santagostino E, Perfetto S, Mannucci PM. Factors influencing the long-term outcome of primary total knee replacement in haemophiliacs: a review of 116 procedures at a single institution. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(2):227-234.

25. Jämsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):87-92.

26. Ragni MV, Crossett LS, Herndon JH. Postoperative infection following orthopaedic surgery in human immunodeficiency virus–infected hemophiliacs with CD4 counts < or = 200/mm3. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):716-721.

27. Hicks JL, Ribbans WJ, Buzzard B, et al. Infected joint replacements in HIV-positive patients with haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1050-1054.

28. Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Heiple KG, Sobel M. Total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):98-107.

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Prosthetic survival rates with implant removal for any reason regarded as final endpoint was 92%. Causes of failure were prosthetic infection (6 cases, 6.8%) and loosening (2 cases, 2.2%). Of the 6 prosthetic infections, 5 were regarded as late and 1 as early. Late infections were successfully sorted by performing 2-stage revision TKA with the Constrained Condylar Knee (Zimmer). Acute infections were managed by open joint débridement and polyethylene exchange. Both cases of aseptic loosening of the TKA were successfully managed with 1-stage revision TKA using the same implant model (Figures 2A–2D).

Mean KSS Knee score improved from 79 before surgery to 36 after surgery, and mean KSS Function score improved from 63 to 33. KSS Pain score, which is included in the Knee score, 0 (no pain) to 50 (most severe pain), improved from 47 to 8. Patients receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-positive did not have poorer outcomes relative to those of patients not receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-negative. Patients with liver cirrhosis had a lower prosthetic survival rate and lower Knee scores.

Discussion

The prosthetic survival rate found in this study compares well with other reported rates for patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. However, evidence regarding long-term prosthesis survival in TKAs performed for patients with hemophilia is limited. Table 3 summarizes the main reported series of patients with hemophilia with 10-year prosthetic survival rates, number of TKAs performed, and mean follow-up period; in all these series, implant removal for any reason was regarded as the final endpoint.5-8,16,17 Mean follow-up in our study was 8 years. Clinical outcomes of TKA in patients with severe hemophilia and related disorders are expected to be inferior to those achieved in patients without a bleeding condition. The overall 10-year prosthetic survival rate for cemented TKA implants, as reported by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, was on the order of 93%.18 Mean age of our patients at time of surgery was only 38.2 years. TKAs performed in younger patients without a bleeding disorder have been associated with shorter implant survival times relative to those of elderly patients.19 Thus, Diduch and colleagues20 reported a prosthetic survival rate of 87% at 18 years in 108 TKAs performed on patients under age 55 years. Lonner and colleagues21 reported a better implant survival rate (90% at 8 years) in a series of patients under age 40 years (32 TKAs). In a study by Duffy and colleagues,22 the implant survival rate was 85% at 15 years in patients under age 55 years (74 TKAs). The results from our retrospective case assessment are quite similar to the overall prosthetic survival rates reported for TKAs performed on patients without hemophilia.

Rates of periprosthetic infection after primary TKA in patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions are much higher (up to 11%), with a mean infection rate of 6.2% (range, 1% to 11%), consistent with the rate found in our series of patients (6.8%)7,16,17,23,24 (Table 4). This rate is much higher than that reported after primary TKA in patients without hemophilia but is similar to some rates reported for patients with hemophilia. In our experience, most periprosthetic infections (5/6) were sorted as late.

Late infection is a major concern after TKA in patients with hemophilia, and various factors have been hypothesized as contributing to the high prevalence. An important factor is the high rate of HIV-positive patients among patients with hemophilia—which acts as a strong predisposing factor because of the often low CD4 counts and associated immune deficiency,25 but different reports have provided conflicting results in this respect.5,6,12 We found no relationship between HIV status and risk for periprosthetic infection, but conclusions are limited by the low number of HIV-positive patients in our series (14/74, 18.9%). Our patients’ late periprosthetic infections were diagnosed several years after TKA, suggesting hematogenous spread of infection. Most of these patients either were on regular prophylactic factor infusions or were being treated on demand, which might entail a risk for contamination of infusions by skin bacteria from the puncture site. Therefore, having an aseptic technique for administering coagulation factor concentrates is of paramount importance for patients with hemophilia and a knee implant.

Another important complication of TKA surgery is aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Aseptic loosening occurred in 2.2% of our patients, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere.11,26 Rates of this complication increase over follow-up, and some authors have linked this complication to TKA polyethylene wear.27 Development of a reactive and destructive bone–cement interface and microhemorrhages into such interface might be implicated in the higher rate of loosening observed among patients with hemophilia.28

In the present study, preoperative and postoperative functional outcomes differed significantly. A modest postoperative total ROM of 69º to 79º has been reported by several authors.5,6 Postoperative ROM may vary—may be slightly increased, remain unchanged, or may even be reduced.4,23,26 Even though little improvement in total ROM is achieved after TKA, many authors have reported reduced flexion contracture and hence an easier gait. However, along with functional improvement, dramatic pain relief after TKA is perhaps the most remarkable aspect, and it has a strong effect on patient satisfaction after surgery.5,7,8,18,23

Our study had 2 main limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series evaluation with the usual issues of potential inaccuracy of medical records and information bias. Second, the study did not include a control group.

Conclusion

The primary TKAs performed in our patients with hemophilia have had a good prosthetic survival rate. Even though such a result is slightly inferior to results in patients without hemophilia, our prosthetic survival rate is not significantly different from the rates reported in other, younger patient subsets. Late periprosthetic infections are a major concern, and taking precautions to avoid hematogenous spread of infections during factor concentrate infusions is strongly encouraged.

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results