User login

CD123 may be a marker for residual disease and response evaluation in AML and B-ALL

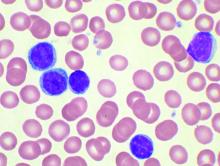

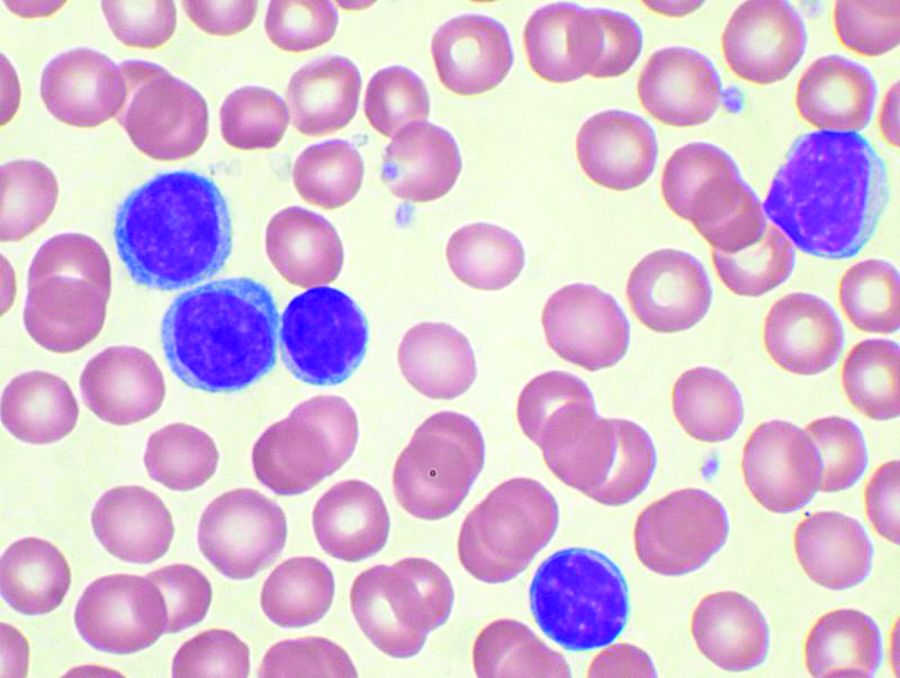

CD123, a membrane-bound interleukin-3 receptor, is overexpressed in many hematological malignancies, and it has been found useful in characterizing both acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). CD123 expression also appears positively correlated with the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) after treatment, and may be useful as a marker of treatment success, according to a report presented online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

Nupur Das, MD, and colleagues from the Dr B.R. Ambedkar Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, New Delhi, India, evaluated the pattern of CD123 expression across different subtypes of acute leukemia to assess its utility as a diagnostic marker, and to assess its impact on MRD assessment and early treatment outcome.

The evaluated the expression of CD123 in 757 samples of acute leukemia (479 treatment-naive and 278 follow-up samples) and compared the results with post-induction morphological remission (CR) and measurable residual disease (MRD) status.

The researchers used cut-offs of 5%, 10%, and 20% CD123-expression positive results to define a case as CD123 positive. On this basis, expression of CD123 was observed in 75.6%, 66.2%. and 50% of AML samples and 88.6%, 81.8%, and 75% of B-ALL samples respectively. They also found that none of the 12 T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cases expressed CD123.

In addition, they found that CD123 expression was associated with MRD-positive status in both B-ALL (P < .001) and AML (P = .001).

“MRD is already an established post-treatment prognostication tool in acute leukemia and hence, the positive correlation of CD123 expression with MRD positivity in AML signifies its utility as an important marker to assess early response to therapy,” the researchers stated.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Das N et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 10; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.004.

CD123, a membrane-bound interleukin-3 receptor, is overexpressed in many hematological malignancies, and it has been found useful in characterizing both acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). CD123 expression also appears positively correlated with the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) after treatment, and may be useful as a marker of treatment success, according to a report presented online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

Nupur Das, MD, and colleagues from the Dr B.R. Ambedkar Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, New Delhi, India, evaluated the pattern of CD123 expression across different subtypes of acute leukemia to assess its utility as a diagnostic marker, and to assess its impact on MRD assessment and early treatment outcome.

The evaluated the expression of CD123 in 757 samples of acute leukemia (479 treatment-naive and 278 follow-up samples) and compared the results with post-induction morphological remission (CR) and measurable residual disease (MRD) status.

The researchers used cut-offs of 5%, 10%, and 20% CD123-expression positive results to define a case as CD123 positive. On this basis, expression of CD123 was observed in 75.6%, 66.2%. and 50% of AML samples and 88.6%, 81.8%, and 75% of B-ALL samples respectively. They also found that none of the 12 T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cases expressed CD123.

In addition, they found that CD123 expression was associated with MRD-positive status in both B-ALL (P < .001) and AML (P = .001).

“MRD is already an established post-treatment prognostication tool in acute leukemia and hence, the positive correlation of CD123 expression with MRD positivity in AML signifies its utility as an important marker to assess early response to therapy,” the researchers stated.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Das N et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 10; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.004.

CD123, a membrane-bound interleukin-3 receptor, is overexpressed in many hematological malignancies, and it has been found useful in characterizing both acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). CD123 expression also appears positively correlated with the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) after treatment, and may be useful as a marker of treatment success, according to a report presented online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

Nupur Das, MD, and colleagues from the Dr B.R. Ambedkar Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, New Delhi, India, evaluated the pattern of CD123 expression across different subtypes of acute leukemia to assess its utility as a diagnostic marker, and to assess its impact on MRD assessment and early treatment outcome.

The evaluated the expression of CD123 in 757 samples of acute leukemia (479 treatment-naive and 278 follow-up samples) and compared the results with post-induction morphological remission (CR) and measurable residual disease (MRD) status.

The researchers used cut-offs of 5%, 10%, and 20% CD123-expression positive results to define a case as CD123 positive. On this basis, expression of CD123 was observed in 75.6%, 66.2%. and 50% of AML samples and 88.6%, 81.8%, and 75% of B-ALL samples respectively. They also found that none of the 12 T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cases expressed CD123.

In addition, they found that CD123 expression was associated with MRD-positive status in both B-ALL (P < .001) and AML (P = .001).

“MRD is already an established post-treatment prognostication tool in acute leukemia and hence, the positive correlation of CD123 expression with MRD positivity in AML signifies its utility as an important marker to assess early response to therapy,” the researchers stated.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Das N et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 10; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.004.

FROM Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia

Video coaching may relieve anxiety and distress for long-distance cancer caregivers

Anxiety and distress related to caring for a cancer patient who lives far away may be alleviated through an intervention that includes video-based coaching sessions with a nurse practitioner or social worker, a randomized study suggests.

About 20% of long-distance caregivers had a significant reduction in anxiety and 25% had a significant reduction in distress when they received video coaching sessions, attended oncologist visits via video, and had access to a website specifically designed for their needs.

Adding the caregiver to oncologist office visits made the patients feel better supported and didn’t add a significant amount of time to the encounter, said Sara L. Douglas, PhD, RN, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Taken together, these results suggest that fairly simple technologies can be leveraged to help caregivers cope with psychological strains related to supporting a patient who doesn’t live nearby, Dr. Douglas said.

Distance caregivers, defined as those who live an hour or more away from the patient, can experience high rates of distress and anxiety because they lack first-hand information or may have uncertainty about the patient’s current condition, according to Dr. Douglas and colleagues.

“Caregivers’ high rates of anxiety and distress have been found to have a negative impact not only upon their own health but upon their ability to provide high quality care to the patient,” Dr. Douglas said.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues conducted a 4-month study of distance caregivers. Dr. Douglas presented results from the study at the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program during a press briefing in advance of the meeting. This year, ASCO’s annual meeting is split into two parts. The virtual scientific program will be presented online on May 29-31, and the virtual education program will be available Aug. 8-10.

Study details

The study enrolled 441 distance caregivers of cancer patients, and Dr. Douglas presented results in 311 of those caregivers. (Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.) The caregivers were, on average, 47 years of age. Most were female (72%), white (67%), the child of the patient (63%), currently employed (81%), and new to the distance caregiver role (89%).

The caregivers were randomized to one of three study arms.

One arm received the full intervention, which consisted of four video-coaching sessions with an advanced practice nurse or social worker, videoconference office visits with the physician and patient, and access to a website with information for cancer distance caregivers. A second arm received no video coaching but had access to the website and participated in video visits with the physician and patient. The third arm, which only received access to the website, served as the study’s control group.

Results

Dr. Douglas said that the full intervention had the biggest impact on caregivers’ distress and anxiety.

Among distance caregivers who received the full intervention, 19.2% had a significant reduction in anxiety (P = .03), as measured in online surveys before and after the intervention using the PROMIS Anxiety instrument. Furthermore, 24.8% of these caregivers had a significant reduction in distress (P = .02) from preintervention to post intervention, as measured by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer. Overall, distress and anxiety scores decreased in this arm.

Distance caregivers who only had physician-patient video visits and website access had a “moderate” reduction in distress and anxiety, Dr. Douglas said. Among these caregivers, 17.3% had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 19.8% had an improvement in distress. Overall, distress scores decreased, but anxiety scores increased slightly in this arm.

In the control arm, 13.1% of caregivers had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 18% had an improvement in distress. Overall, both anxiety and distress scores increased in this arm.

“While the full intervention yielded the best results for distance caregivers, we recognize that not all health care systems have the resources to provide individualized coaching sessions to distance caregivers,” Dr. Douglas said. “Therefore, it is worth noting that videoconference office visits alone are found to be of some benefit in improving distress and anxiety in this group of cancer caregivers.”

The study results suggest videoconferencing interventions can improve the emotional well-being of remote caregivers who provide “critical support” for cancer patients, said ASCO President Howard A. “Skip” Burris III, MD.

“As COVID-19 forces separation from loved ones and increases anxiety for people with cancer and their caregivers, providing emotional support virtually is more important than ever,” Dr. Burris said in a news release highlighting the study.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Douglas reported having no disclosures. Other researchers involved in the study disclosed relationships with BridgeBio Pharma, Cardinal Health, Apexigen, Roche/Genentech, Seattle Genetics, Tesaro, Array BioPharma, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene. A full list of Dr. Burris’s financial disclosures is available on the ASCO website.

SOURCE: Douglas SL et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 12123.

Anxiety and distress related to caring for a cancer patient who lives far away may be alleviated through an intervention that includes video-based coaching sessions with a nurse practitioner or social worker, a randomized study suggests.

About 20% of long-distance caregivers had a significant reduction in anxiety and 25% had a significant reduction in distress when they received video coaching sessions, attended oncologist visits via video, and had access to a website specifically designed for their needs.

Adding the caregiver to oncologist office visits made the patients feel better supported and didn’t add a significant amount of time to the encounter, said Sara L. Douglas, PhD, RN, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Taken together, these results suggest that fairly simple technologies can be leveraged to help caregivers cope with psychological strains related to supporting a patient who doesn’t live nearby, Dr. Douglas said.

Distance caregivers, defined as those who live an hour or more away from the patient, can experience high rates of distress and anxiety because they lack first-hand information or may have uncertainty about the patient’s current condition, according to Dr. Douglas and colleagues.

“Caregivers’ high rates of anxiety and distress have been found to have a negative impact not only upon their own health but upon their ability to provide high quality care to the patient,” Dr. Douglas said.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues conducted a 4-month study of distance caregivers. Dr. Douglas presented results from the study at the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program during a press briefing in advance of the meeting. This year, ASCO’s annual meeting is split into two parts. The virtual scientific program will be presented online on May 29-31, and the virtual education program will be available Aug. 8-10.

Study details

The study enrolled 441 distance caregivers of cancer patients, and Dr. Douglas presented results in 311 of those caregivers. (Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.) The caregivers were, on average, 47 years of age. Most were female (72%), white (67%), the child of the patient (63%), currently employed (81%), and new to the distance caregiver role (89%).

The caregivers were randomized to one of three study arms.

One arm received the full intervention, which consisted of four video-coaching sessions with an advanced practice nurse or social worker, videoconference office visits with the physician and patient, and access to a website with information for cancer distance caregivers. A second arm received no video coaching but had access to the website and participated in video visits with the physician and patient. The third arm, which only received access to the website, served as the study’s control group.

Results

Dr. Douglas said that the full intervention had the biggest impact on caregivers’ distress and anxiety.

Among distance caregivers who received the full intervention, 19.2% had a significant reduction in anxiety (P = .03), as measured in online surveys before and after the intervention using the PROMIS Anxiety instrument. Furthermore, 24.8% of these caregivers had a significant reduction in distress (P = .02) from preintervention to post intervention, as measured by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer. Overall, distress and anxiety scores decreased in this arm.

Distance caregivers who only had physician-patient video visits and website access had a “moderate” reduction in distress and anxiety, Dr. Douglas said. Among these caregivers, 17.3% had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 19.8% had an improvement in distress. Overall, distress scores decreased, but anxiety scores increased slightly in this arm.

In the control arm, 13.1% of caregivers had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 18% had an improvement in distress. Overall, both anxiety and distress scores increased in this arm.

“While the full intervention yielded the best results for distance caregivers, we recognize that not all health care systems have the resources to provide individualized coaching sessions to distance caregivers,” Dr. Douglas said. “Therefore, it is worth noting that videoconference office visits alone are found to be of some benefit in improving distress and anxiety in this group of cancer caregivers.”

The study results suggest videoconferencing interventions can improve the emotional well-being of remote caregivers who provide “critical support” for cancer patients, said ASCO President Howard A. “Skip” Burris III, MD.

“As COVID-19 forces separation from loved ones and increases anxiety for people with cancer and their caregivers, providing emotional support virtually is more important than ever,” Dr. Burris said in a news release highlighting the study.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Douglas reported having no disclosures. Other researchers involved in the study disclosed relationships with BridgeBio Pharma, Cardinal Health, Apexigen, Roche/Genentech, Seattle Genetics, Tesaro, Array BioPharma, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene. A full list of Dr. Burris’s financial disclosures is available on the ASCO website.

SOURCE: Douglas SL et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 12123.

Anxiety and distress related to caring for a cancer patient who lives far away may be alleviated through an intervention that includes video-based coaching sessions with a nurse practitioner or social worker, a randomized study suggests.

About 20% of long-distance caregivers had a significant reduction in anxiety and 25% had a significant reduction in distress when they received video coaching sessions, attended oncologist visits via video, and had access to a website specifically designed for their needs.

Adding the caregiver to oncologist office visits made the patients feel better supported and didn’t add a significant amount of time to the encounter, said Sara L. Douglas, PhD, RN, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Taken together, these results suggest that fairly simple technologies can be leveraged to help caregivers cope with psychological strains related to supporting a patient who doesn’t live nearby, Dr. Douglas said.

Distance caregivers, defined as those who live an hour or more away from the patient, can experience high rates of distress and anxiety because they lack first-hand information or may have uncertainty about the patient’s current condition, according to Dr. Douglas and colleagues.

“Caregivers’ high rates of anxiety and distress have been found to have a negative impact not only upon their own health but upon their ability to provide high quality care to the patient,” Dr. Douglas said.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues conducted a 4-month study of distance caregivers. Dr. Douglas presented results from the study at the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program during a press briefing in advance of the meeting. This year, ASCO’s annual meeting is split into two parts. The virtual scientific program will be presented online on May 29-31, and the virtual education program will be available Aug. 8-10.

Study details

The study enrolled 441 distance caregivers of cancer patients, and Dr. Douglas presented results in 311 of those caregivers. (Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.) The caregivers were, on average, 47 years of age. Most were female (72%), white (67%), the child of the patient (63%), currently employed (81%), and new to the distance caregiver role (89%).

The caregivers were randomized to one of three study arms.

One arm received the full intervention, which consisted of four video-coaching sessions with an advanced practice nurse or social worker, videoconference office visits with the physician and patient, and access to a website with information for cancer distance caregivers. A second arm received no video coaching but had access to the website and participated in video visits with the physician and patient. The third arm, which only received access to the website, served as the study’s control group.

Results

Dr. Douglas said that the full intervention had the biggest impact on caregivers’ distress and anxiety.

Among distance caregivers who received the full intervention, 19.2% had a significant reduction in anxiety (P = .03), as measured in online surveys before and after the intervention using the PROMIS Anxiety instrument. Furthermore, 24.8% of these caregivers had a significant reduction in distress (P = .02) from preintervention to post intervention, as measured by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer. Overall, distress and anxiety scores decreased in this arm.

Distance caregivers who only had physician-patient video visits and website access had a “moderate” reduction in distress and anxiety, Dr. Douglas said. Among these caregivers, 17.3% had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 19.8% had an improvement in distress. Overall, distress scores decreased, but anxiety scores increased slightly in this arm.

In the control arm, 13.1% of caregivers had an improvement in anxiety from baseline, and 18% had an improvement in distress. Overall, both anxiety and distress scores increased in this arm.

“While the full intervention yielded the best results for distance caregivers, we recognize that not all health care systems have the resources to provide individualized coaching sessions to distance caregivers,” Dr. Douglas said. “Therefore, it is worth noting that videoconference office visits alone are found to be of some benefit in improving distress and anxiety in this group of cancer caregivers.”

The study results suggest videoconferencing interventions can improve the emotional well-being of remote caregivers who provide “critical support” for cancer patients, said ASCO President Howard A. “Skip” Burris III, MD.

“As COVID-19 forces separation from loved ones and increases anxiety for people with cancer and their caregivers, providing emotional support virtually is more important than ever,” Dr. Burris said in a news release highlighting the study.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Douglas reported having no disclosures. Other researchers involved in the study disclosed relationships with BridgeBio Pharma, Cardinal Health, Apexigen, Roche/Genentech, Seattle Genetics, Tesaro, Array BioPharma, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene. A full list of Dr. Burris’s financial disclosures is available on the ASCO website.

SOURCE: Douglas SL et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 12123.

FROM ASCO 2020

Secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia more lethal than de novo

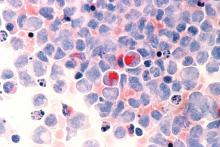

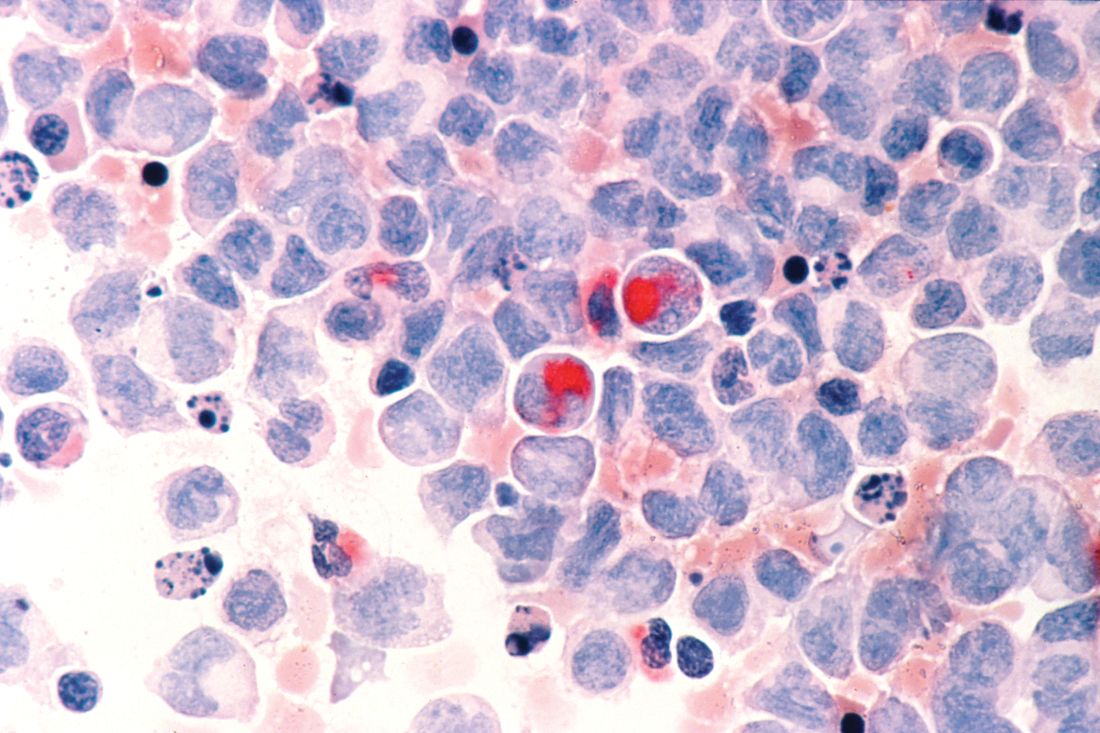

The application of improved chemotherapy regimens and novel chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has increased the complete remission rate to 85%-90%, however, secondary ALL is common, and the prolonged long-term survival rate is only 30%-50% among ALL patients.

Favorable outcomes decrease with increasing age, and overall survival is greater for adult patients with de novo ALL, compared with patients with secondary ALL, according to the Jiansheng Zhong of the department of hematology, Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and colleagues in a new study published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the results of 8,305 ALL patients undergoing chemotherapy from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database during 1975 to 2015, of which 7,454 (80.1%) cases were in the de novo ALL group, and 851 (19.9%) cases were in the secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia (sALL) group. They used propensity matching before assessing overall survival between the two groups.

Demographically, the results showed that women ALL patients had a lower risk of death than men [hazard ratio (HR) = .93, P < .01], and that the mortality in blacks was higher than that of whites (HR = 1.29, P < .001).

For both ALL groups, patients aged 45-75 years and patients 75 years and older had a higher risk of death than younger patients (HR = 1.82, P < .001 and HR = 3.85, P < .001, respectively).

Although the mean age of de novo ALL group was significantly less than that of the sALL group (51.1 vs. 60.3 years, P < .001), after the propensity matching, the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year overall survival of the de novo ALL group was higher than that of the sALL group at all ages (18-75 years, P < .001).

The authors speculated that one reason for the across-the-board increased mortality in sALL, compared with de novo ALL, might be the fact that sALL patients have been reported to have more MLL gene rearrangements and chromosomal aberrations than are found in de novo ALL. This has previously been suggested as the reason for poor prognosis in secondary ALL patients.

One limitation of the study mentioned by the authors was the lack of individualized chemotherapy data available for analysis. “Considering that the features of sALL and chemotherapeutic modalities or therapy protocols may affect the mortality of sALL, more work is needed to be done in the future to demonstrate the association between chemotherapy and the prognosis of ALL patients, and the influence of cytogenetic lesions and molecular characteristics on sALL,” they concluded.

The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhong J et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 30; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.013.

The application of improved chemotherapy regimens and novel chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has increased the complete remission rate to 85%-90%, however, secondary ALL is common, and the prolonged long-term survival rate is only 30%-50% among ALL patients.

Favorable outcomes decrease with increasing age, and overall survival is greater for adult patients with de novo ALL, compared with patients with secondary ALL, according to the Jiansheng Zhong of the department of hematology, Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and colleagues in a new study published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the results of 8,305 ALL patients undergoing chemotherapy from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database during 1975 to 2015, of which 7,454 (80.1%) cases were in the de novo ALL group, and 851 (19.9%) cases were in the secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia (sALL) group. They used propensity matching before assessing overall survival between the two groups.

Demographically, the results showed that women ALL patients had a lower risk of death than men [hazard ratio (HR) = .93, P < .01], and that the mortality in blacks was higher than that of whites (HR = 1.29, P < .001).

For both ALL groups, patients aged 45-75 years and patients 75 years and older had a higher risk of death than younger patients (HR = 1.82, P < .001 and HR = 3.85, P < .001, respectively).

Although the mean age of de novo ALL group was significantly less than that of the sALL group (51.1 vs. 60.3 years, P < .001), after the propensity matching, the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year overall survival of the de novo ALL group was higher than that of the sALL group at all ages (18-75 years, P < .001).

The authors speculated that one reason for the across-the-board increased mortality in sALL, compared with de novo ALL, might be the fact that sALL patients have been reported to have more MLL gene rearrangements and chromosomal aberrations than are found in de novo ALL. This has previously been suggested as the reason for poor prognosis in secondary ALL patients.

One limitation of the study mentioned by the authors was the lack of individualized chemotherapy data available for analysis. “Considering that the features of sALL and chemotherapeutic modalities or therapy protocols may affect the mortality of sALL, more work is needed to be done in the future to demonstrate the association between chemotherapy and the prognosis of ALL patients, and the influence of cytogenetic lesions and molecular characteristics on sALL,” they concluded.

The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhong J et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 30; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.013.

The application of improved chemotherapy regimens and novel chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has increased the complete remission rate to 85%-90%, however, secondary ALL is common, and the prolonged long-term survival rate is only 30%-50% among ALL patients.

Favorable outcomes decrease with increasing age, and overall survival is greater for adult patients with de novo ALL, compared with patients with secondary ALL, according to the Jiansheng Zhong of the department of hematology, Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, and colleagues in a new study published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the results of 8,305 ALL patients undergoing chemotherapy from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database during 1975 to 2015, of which 7,454 (80.1%) cases were in the de novo ALL group, and 851 (19.9%) cases were in the secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia (sALL) group. They used propensity matching before assessing overall survival between the two groups.

Demographically, the results showed that women ALL patients had a lower risk of death than men [hazard ratio (HR) = .93, P < .01], and that the mortality in blacks was higher than that of whites (HR = 1.29, P < .001).

For both ALL groups, patients aged 45-75 years and patients 75 years and older had a higher risk of death than younger patients (HR = 1.82, P < .001 and HR = 3.85, P < .001, respectively).

Although the mean age of de novo ALL group was significantly less than that of the sALL group (51.1 vs. 60.3 years, P < .001), after the propensity matching, the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year overall survival of the de novo ALL group was higher than that of the sALL group at all ages (18-75 years, P < .001).

The authors speculated that one reason for the across-the-board increased mortality in sALL, compared with de novo ALL, might be the fact that sALL patients have been reported to have more MLL gene rearrangements and chromosomal aberrations than are found in de novo ALL. This has previously been suggested as the reason for poor prognosis in secondary ALL patients.

One limitation of the study mentioned by the authors was the lack of individualized chemotherapy data available for analysis. “Considering that the features of sALL and chemotherapeutic modalities or therapy protocols may affect the mortality of sALL, more work is needed to be done in the future to demonstrate the association between chemotherapy and the prognosis of ALL patients, and the influence of cytogenetic lesions and molecular characteristics on sALL,” they concluded.

The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhong J et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 30; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.013.

FROM Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia

ASCO goes ahead online, as conference center is used as hospital

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Interleukin-27 increased cytotoxic effects of bone marrow NK cells in CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is characterized by significant immune perturbation, including significant impairment of natural killer (NK) cells, which leads to disease complications and reduced effectiveness of treatment.

However, the use of , according to an in vitro study conducted by Maral Hemati, a student researcher at the Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Ms. Hemati and her colleagues obtained bone marrow aspirates (BM) and peripheral blood samples (PB) were from 12 untreated CLL patients (9 men and 3 women) with a median age of 61 years. The cells were cultured in vitro, according to their report in International Immunopharmacology.

The researchers found that the use of recombinant human interleukin-27 (IL-27) stimulated NK cells in the cultured BM and PB cells of CLL patients, based upon assessment using cell surface flow cytometry and a cytotoxicity assay.

Treatment with IL-27 also increased CD69 (a marker for NK cell activity) on NK cells both in BM and PB. In addition, , whereas it did not improve NK cell activity of PB, according to the researchers.

The research was supported by Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hemati M et al. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;82:doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106350.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is characterized by significant immune perturbation, including significant impairment of natural killer (NK) cells, which leads to disease complications and reduced effectiveness of treatment.

However, the use of , according to an in vitro study conducted by Maral Hemati, a student researcher at the Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Ms. Hemati and her colleagues obtained bone marrow aspirates (BM) and peripheral blood samples (PB) were from 12 untreated CLL patients (9 men and 3 women) with a median age of 61 years. The cells were cultured in vitro, according to their report in International Immunopharmacology.

The researchers found that the use of recombinant human interleukin-27 (IL-27) stimulated NK cells in the cultured BM and PB cells of CLL patients, based upon assessment using cell surface flow cytometry and a cytotoxicity assay.

Treatment with IL-27 also increased CD69 (a marker for NK cell activity) on NK cells both in BM and PB. In addition, , whereas it did not improve NK cell activity of PB, according to the researchers.

The research was supported by Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hemati M et al. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;82:doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106350.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is characterized by significant immune perturbation, including significant impairment of natural killer (NK) cells, which leads to disease complications and reduced effectiveness of treatment.

However, the use of , according to an in vitro study conducted by Maral Hemati, a student researcher at the Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Ms. Hemati and her colleagues obtained bone marrow aspirates (BM) and peripheral blood samples (PB) were from 12 untreated CLL patients (9 men and 3 women) with a median age of 61 years. The cells were cultured in vitro, according to their report in International Immunopharmacology.

The researchers found that the use of recombinant human interleukin-27 (IL-27) stimulated NK cells in the cultured BM and PB cells of CLL patients, based upon assessment using cell surface flow cytometry and a cytotoxicity assay.

Treatment with IL-27 also increased CD69 (a marker for NK cell activity) on NK cells both in BM and PB. In addition, , whereas it did not improve NK cell activity of PB, according to the researchers.

The research was supported by Semnan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hemati M et al. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;82:doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106350.

FROM INTERNATIONAL IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

Excess cancer deaths predicted as care is disrupted by COVID-19

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.