User login

Post-hoc analysis offers hope for novel cholesterol drug

MILAN, Italy – The antisense oligonucleotide vupanorsen substantially reduces very-low-density-lipoprotein (VLDL) and remnant cholesterol levels in patients with raised lipids despite statin therapy, suggests a subanalysis of TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 that appears to offer more hope than the primary study findings.

Vupanorsen targets hepatic angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), which inhibits enzymes involved in triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism.

Earlier this year, headline data from TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 suggested that the drug reduced triglycerides and non–high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol to a degree that was significant but not clinically meaningful for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Moreover, as reported by this news organization, there were safety concerns over increases in liver enzymes among patients taking the drug, as well as dose-related increases in hepatic fat.

As a result, Pfizer announced that it would discontinue its clinical development program for vupanorsen and return the development rights to Ionis, following the signing of a worldwide exclusive agreement in November 2019.

Now, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, MPH, cardiovascular medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, has presented a post-hoc analysis of the phase 2b study, showing that the drug reduces VLDL and remnant cholesterol levels by up to 60%.

These were closely tied to reductions in ANGPTL3 levels, although substantial reductions in cholesterol levels were achieved even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL3, where the impact on safety outcomes was reduced.

Dr. Marston said that lower doses of vupanorsen, where the safety effects would be less, or other drugs that inhibit ANGPTL3, “may have an important role in patients with residual dyslipidemia despite current therapy.”

The results were presented at the 90th European Atherosclerosis Society Congress on May 23.

Dr. Marston told this news organization that some of the reductions they saw with the lower doses of vupanorsen were “just as good as any other therapy, and the safety profile was … much better than at the highest dose.”

They wanted to pursue the subgroup analysis, despite Pfizer’s announcement, partly to “learn something in terms of the potential efficacy of the ANGPTL3 pathway in general.”

Dr. Marston said that Ionis is now focused on ANGPTL3, and the current results suggest that it “works very well,” so if other drugs are able to achieve the same efficacy as vupanorsen “but without the effects,” then it may “get elbowed out.”

Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, PhD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who was not involved in the study, called the findings “very encouraging.”

He told this news organization that being able to reduce LDL cholesterol as well as VLDL and remnant cholesterol is “exactly what I would be dreaming about” with a drug like vupanorsen.

Dr. Nordestgaard nevertheless underlined that “one would have to look carefully” at the safety of the drug.

“If it was my money, I would certainly try to look into if this was some sort of transient thing. Even when they started talking about statins, there was also this transient increase in alanine transaminase that seems to go away after a while,” he said.

“But of course, if this was persistent and triglycerides in the liver kept accumulating, then it’s a problem,” Dr. Nordestgaard added, “and then you would need to have some sort of thinking about whether you could couple it with something that got rid of the liver fat.”

He also agreed with Dr. Marston that, even if vupanorsen does not clear all hurdles before making it to market, the approach is promising.

“The target,” Dr. Nordestgaard said, seems “fantastic, from my point of view anyway.”

Dr. Marston explained that VLDL cholesterol, remnant cholesterol, and triglycerides are “surrogates for triglyceride-rich” lipoproteins, and that they are “increasingly recognized” as cardiovascular risk factors.

He highlighted that currently available therapies achieve reductions of these compounds of between 30% and 50%.

TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 included adults on stable statin therapy who had a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL to 500 mg/dL and a non-HDL cholesterol level of 100 mg/dL or higher.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of six 2- or 4-week dosing schedules of vupanorsen or placebo and followed up over 24 weeks for a series of primary and additional endpoints, as well as safety outcomes.

The team recruited 286 individuals, who had a median age of 64 years; 44% were female. The majority (87%) were white.

The mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, 50% had diabetes, 13% had experienced a prior myocardial infarction, and 51% were receiving high-intensity statins.

As previously reported, vupanorsen was associated with a reduction in non-HDL cholesterol vs. placebo of 22%-28%, alongside a 6%-15% reduction in apolipoprotein B levels and an 8%-16% reduction in LDL cholesterol.

In contrast, Dr. Marston showed that the various dosing schedules of the drug were associated with reductions in levels of VLDL cholesterol of 52%-66% vs. placebo at 24 weeks.

Over the same period, remnant cholesterol levels were lowered by 42%-59% vs. placebo, and triglycerides were reduced by 44%-57% in patients given vupanorsen.

There were also reductions in ANGPTL3 levels of 70%-95%.

Subgroup analysis indicated that the effect of vupanorsen was seen regardless of age, sex, body mass index, presence of diabetes, baseline triglycerides, and intensity of statin therapy.

Dr. Marston highlighted that the reductions in triglycerides, VLDL cholesterol, and remnant cholesterol levels were directly related to those for ANGPTL3 levels, but that the reductions remained meaningful even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL.

For example, even when ANGPTL3 levels were reduced by 70%, there were 50% reductions in triglyceride levels, 70% reductions in VLDL cholesterol levels, and a 50% drop in remnant cholesterol levels.

This, he noted, is important given that safety signals such as increases in alanine transaminase and hepatic fat occurred in a dose-dependent manner with ANGPTL3 reductions and were “most pronounced” only at the highest level of ANGPTL3 reduction.

The TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Marston disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Amgen, Ionis, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Nordestgaard disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Ionis, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN, Italy – The antisense oligonucleotide vupanorsen substantially reduces very-low-density-lipoprotein (VLDL) and remnant cholesterol levels in patients with raised lipids despite statin therapy, suggests a subanalysis of TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 that appears to offer more hope than the primary study findings.

Vupanorsen targets hepatic angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), which inhibits enzymes involved in triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism.

Earlier this year, headline data from TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 suggested that the drug reduced triglycerides and non–high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol to a degree that was significant but not clinically meaningful for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Moreover, as reported by this news organization, there were safety concerns over increases in liver enzymes among patients taking the drug, as well as dose-related increases in hepatic fat.

As a result, Pfizer announced that it would discontinue its clinical development program for vupanorsen and return the development rights to Ionis, following the signing of a worldwide exclusive agreement in November 2019.

Now, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, MPH, cardiovascular medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, has presented a post-hoc analysis of the phase 2b study, showing that the drug reduces VLDL and remnant cholesterol levels by up to 60%.

These were closely tied to reductions in ANGPTL3 levels, although substantial reductions in cholesterol levels were achieved even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL3, where the impact on safety outcomes was reduced.

Dr. Marston said that lower doses of vupanorsen, where the safety effects would be less, or other drugs that inhibit ANGPTL3, “may have an important role in patients with residual dyslipidemia despite current therapy.”

The results were presented at the 90th European Atherosclerosis Society Congress on May 23.

Dr. Marston told this news organization that some of the reductions they saw with the lower doses of vupanorsen were “just as good as any other therapy, and the safety profile was … much better than at the highest dose.”

They wanted to pursue the subgroup analysis, despite Pfizer’s announcement, partly to “learn something in terms of the potential efficacy of the ANGPTL3 pathway in general.”

Dr. Marston said that Ionis is now focused on ANGPTL3, and the current results suggest that it “works very well,” so if other drugs are able to achieve the same efficacy as vupanorsen “but without the effects,” then it may “get elbowed out.”

Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, PhD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who was not involved in the study, called the findings “very encouraging.”

He told this news organization that being able to reduce LDL cholesterol as well as VLDL and remnant cholesterol is “exactly what I would be dreaming about” with a drug like vupanorsen.

Dr. Nordestgaard nevertheless underlined that “one would have to look carefully” at the safety of the drug.

“If it was my money, I would certainly try to look into if this was some sort of transient thing. Even when they started talking about statins, there was also this transient increase in alanine transaminase that seems to go away after a while,” he said.

“But of course, if this was persistent and triglycerides in the liver kept accumulating, then it’s a problem,” Dr. Nordestgaard added, “and then you would need to have some sort of thinking about whether you could couple it with something that got rid of the liver fat.”

He also agreed with Dr. Marston that, even if vupanorsen does not clear all hurdles before making it to market, the approach is promising.

“The target,” Dr. Nordestgaard said, seems “fantastic, from my point of view anyway.”

Dr. Marston explained that VLDL cholesterol, remnant cholesterol, and triglycerides are “surrogates for triglyceride-rich” lipoproteins, and that they are “increasingly recognized” as cardiovascular risk factors.

He highlighted that currently available therapies achieve reductions of these compounds of between 30% and 50%.

TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 included adults on stable statin therapy who had a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL to 500 mg/dL and a non-HDL cholesterol level of 100 mg/dL or higher.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of six 2- or 4-week dosing schedules of vupanorsen or placebo and followed up over 24 weeks for a series of primary and additional endpoints, as well as safety outcomes.

The team recruited 286 individuals, who had a median age of 64 years; 44% were female. The majority (87%) were white.

The mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, 50% had diabetes, 13% had experienced a prior myocardial infarction, and 51% were receiving high-intensity statins.

As previously reported, vupanorsen was associated with a reduction in non-HDL cholesterol vs. placebo of 22%-28%, alongside a 6%-15% reduction in apolipoprotein B levels and an 8%-16% reduction in LDL cholesterol.

In contrast, Dr. Marston showed that the various dosing schedules of the drug were associated with reductions in levels of VLDL cholesterol of 52%-66% vs. placebo at 24 weeks.

Over the same period, remnant cholesterol levels were lowered by 42%-59% vs. placebo, and triglycerides were reduced by 44%-57% in patients given vupanorsen.

There were also reductions in ANGPTL3 levels of 70%-95%.

Subgroup analysis indicated that the effect of vupanorsen was seen regardless of age, sex, body mass index, presence of diabetes, baseline triglycerides, and intensity of statin therapy.

Dr. Marston highlighted that the reductions in triglycerides, VLDL cholesterol, and remnant cholesterol levels were directly related to those for ANGPTL3 levels, but that the reductions remained meaningful even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL.

For example, even when ANGPTL3 levels were reduced by 70%, there were 50% reductions in triglyceride levels, 70% reductions in VLDL cholesterol levels, and a 50% drop in remnant cholesterol levels.

This, he noted, is important given that safety signals such as increases in alanine transaminase and hepatic fat occurred in a dose-dependent manner with ANGPTL3 reductions and were “most pronounced” only at the highest level of ANGPTL3 reduction.

The TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Marston disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Amgen, Ionis, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Nordestgaard disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Ionis, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN, Italy – The antisense oligonucleotide vupanorsen substantially reduces very-low-density-lipoprotein (VLDL) and remnant cholesterol levels in patients with raised lipids despite statin therapy, suggests a subanalysis of TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 that appears to offer more hope than the primary study findings.

Vupanorsen targets hepatic angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), which inhibits enzymes involved in triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism.

Earlier this year, headline data from TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 suggested that the drug reduced triglycerides and non–high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol to a degree that was significant but not clinically meaningful for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Moreover, as reported by this news organization, there were safety concerns over increases in liver enzymes among patients taking the drug, as well as dose-related increases in hepatic fat.

As a result, Pfizer announced that it would discontinue its clinical development program for vupanorsen and return the development rights to Ionis, following the signing of a worldwide exclusive agreement in November 2019.

Now, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, MPH, cardiovascular medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, has presented a post-hoc analysis of the phase 2b study, showing that the drug reduces VLDL and remnant cholesterol levels by up to 60%.

These were closely tied to reductions in ANGPTL3 levels, although substantial reductions in cholesterol levels were achieved even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL3, where the impact on safety outcomes was reduced.

Dr. Marston said that lower doses of vupanorsen, where the safety effects would be less, or other drugs that inhibit ANGPTL3, “may have an important role in patients with residual dyslipidemia despite current therapy.”

The results were presented at the 90th European Atherosclerosis Society Congress on May 23.

Dr. Marston told this news organization that some of the reductions they saw with the lower doses of vupanorsen were “just as good as any other therapy, and the safety profile was … much better than at the highest dose.”

They wanted to pursue the subgroup analysis, despite Pfizer’s announcement, partly to “learn something in terms of the potential efficacy of the ANGPTL3 pathway in general.”

Dr. Marston said that Ionis is now focused on ANGPTL3, and the current results suggest that it “works very well,” so if other drugs are able to achieve the same efficacy as vupanorsen “but without the effects,” then it may “get elbowed out.”

Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, PhD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who was not involved in the study, called the findings “very encouraging.”

He told this news organization that being able to reduce LDL cholesterol as well as VLDL and remnant cholesterol is “exactly what I would be dreaming about” with a drug like vupanorsen.

Dr. Nordestgaard nevertheless underlined that “one would have to look carefully” at the safety of the drug.

“If it was my money, I would certainly try to look into if this was some sort of transient thing. Even when they started talking about statins, there was also this transient increase in alanine transaminase that seems to go away after a while,” he said.

“But of course, if this was persistent and triglycerides in the liver kept accumulating, then it’s a problem,” Dr. Nordestgaard added, “and then you would need to have some sort of thinking about whether you could couple it with something that got rid of the liver fat.”

He also agreed with Dr. Marston that, even if vupanorsen does not clear all hurdles before making it to market, the approach is promising.

“The target,” Dr. Nordestgaard said, seems “fantastic, from my point of view anyway.”

Dr. Marston explained that VLDL cholesterol, remnant cholesterol, and triglycerides are “surrogates for triglyceride-rich” lipoproteins, and that they are “increasingly recognized” as cardiovascular risk factors.

He highlighted that currently available therapies achieve reductions of these compounds of between 30% and 50%.

TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 included adults on stable statin therapy who had a triglyceride level of 150 mg/dL to 500 mg/dL and a non-HDL cholesterol level of 100 mg/dL or higher.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of six 2- or 4-week dosing schedules of vupanorsen or placebo and followed up over 24 weeks for a series of primary and additional endpoints, as well as safety outcomes.

The team recruited 286 individuals, who had a median age of 64 years; 44% were female. The majority (87%) were white.

The mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, 50% had diabetes, 13% had experienced a prior myocardial infarction, and 51% were receiving high-intensity statins.

As previously reported, vupanorsen was associated with a reduction in non-HDL cholesterol vs. placebo of 22%-28%, alongside a 6%-15% reduction in apolipoprotein B levels and an 8%-16% reduction in LDL cholesterol.

In contrast, Dr. Marston showed that the various dosing schedules of the drug were associated with reductions in levels of VLDL cholesterol of 52%-66% vs. placebo at 24 weeks.

Over the same period, remnant cholesterol levels were lowered by 42%-59% vs. placebo, and triglycerides were reduced by 44%-57% in patients given vupanorsen.

There were also reductions in ANGPTL3 levels of 70%-95%.

Subgroup analysis indicated that the effect of vupanorsen was seen regardless of age, sex, body mass index, presence of diabetes, baseline triglycerides, and intensity of statin therapy.

Dr. Marston highlighted that the reductions in triglycerides, VLDL cholesterol, and remnant cholesterol levels were directly related to those for ANGPTL3 levels, but that the reductions remained meaningful even at less than maximal reductions in ANGPTL.

For example, even when ANGPTL3 levels were reduced by 70%, there were 50% reductions in triglyceride levels, 70% reductions in VLDL cholesterol levels, and a 50% drop in remnant cholesterol levels.

This, he noted, is important given that safety signals such as increases in alanine transaminase and hepatic fat occurred in a dose-dependent manner with ANGPTL3 reductions and were “most pronounced” only at the highest level of ANGPTL3 reduction.

The TRANSLATE-TIMI 70 study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Marston disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Amgen, Ionis, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Nordestgaard disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Ionis, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EAS 2022

ADA updates on finerenone, SGLT2 inhibitors, and race-based eGFR

As it gears up for the first in-person scientific sessions for 3 years, the American Diabetes Association has issued an addendum to its most recent annual clinical practice recommendations published in December 2021, the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, based on recent trial evidence and consensus.

The update informs clinicians about:

- The effect of the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid antagonist (Kerendia) on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

- The effect of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor on heart failure and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation to remove race in the formula for calculating estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

“This is the fifth year that we are able to update the Standards of Care after it has been published through our Living Standards of Care updates, making it possible to give diabetes care providers the most important information and the latest evidence relevant to their practice,” Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, ADA chief scientific and medical officer, said in a press release from the organization.

The addendum, entitled, “Living Standards of Care,” updates Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management” of the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.

The amendments were approved by the ADA Professional Practice Committee, which is responsible for developing the Standards of Care. The American College of Cardiology reviewed and endorsed the section on CVD and risk management.

The Living Standards Update was published online in Diabetes Care.

CVD and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “For patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease treated with maximum tolerated doses of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, addition of finerenone should be considered to improve cardiovascular outcomes and reduce the risk of chronic kidney disease progression. A”

- “Patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease should be considered for treatment with finerenone to reduce cardiovascular outcomes and the risk of chronic kidney disease progression.”

- “In patients with type 2 diabetes and established heart failure with either preserved or reduced ejection fraction, an SGLT2 inhibitor [with proven benefit in this patient population] is recommended to reduce risk of worsening heart failure, hospitalizations for heart failure, and cardiovascular death. ”

In the section “Statin Treatment,” the addendum no longer states that “a prospective trial of a newer fibrate ... is ongoing,” because that trial investigating pemafibrate (Kowa), a novel selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha modulator (or fibrate), has been discontinued.

Chronic kidney disease and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “Traditionally, eGFR is calculated from serum creatinine using a validated formula. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation is preferred. ... Historically, a correction factor for muscle mass was included in a modified equation for African Americans; however, due to various issues with inequities, it was decided to the equation such that it applies to all. Hence, a committee was convened, resulting in the recommendation for immediate implementation of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable in all laboratories in the U.S.” (This is based on an National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation.)

- “Additionally, increased use of cystatin C, especially to confirm estimated GFR in adults who are at risk for or have chronic kidney disease, because combining filtration markers (creatinine and cystatin C) is more accurate and would support better clinical decisions than either marker alone.”

Evidence from clinical trials

The update is based on findings from the following clinical trials:

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD)

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD)

- FIDELITY, a prespecified pooled analysis of FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD

- Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved)

- Effects of Dapagliflozin on Biomarkers, Symptoms and Functional Status in Patients with PRESERVED Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (PRESERVED-HF)

- Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes (PROMINENT).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As it gears up for the first in-person scientific sessions for 3 years, the American Diabetes Association has issued an addendum to its most recent annual clinical practice recommendations published in December 2021, the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, based on recent trial evidence and consensus.

The update informs clinicians about:

- The effect of the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid antagonist (Kerendia) on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

- The effect of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor on heart failure and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation to remove race in the formula for calculating estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

“This is the fifth year that we are able to update the Standards of Care after it has been published through our Living Standards of Care updates, making it possible to give diabetes care providers the most important information and the latest evidence relevant to their practice,” Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, ADA chief scientific and medical officer, said in a press release from the organization.

The addendum, entitled, “Living Standards of Care,” updates Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management” of the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.

The amendments were approved by the ADA Professional Practice Committee, which is responsible for developing the Standards of Care. The American College of Cardiology reviewed and endorsed the section on CVD and risk management.

The Living Standards Update was published online in Diabetes Care.

CVD and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “For patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease treated with maximum tolerated doses of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, addition of finerenone should be considered to improve cardiovascular outcomes and reduce the risk of chronic kidney disease progression. A”

- “Patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease should be considered for treatment with finerenone to reduce cardiovascular outcomes and the risk of chronic kidney disease progression.”

- “In patients with type 2 diabetes and established heart failure with either preserved or reduced ejection fraction, an SGLT2 inhibitor [with proven benefit in this patient population] is recommended to reduce risk of worsening heart failure, hospitalizations for heart failure, and cardiovascular death. ”

In the section “Statin Treatment,” the addendum no longer states that “a prospective trial of a newer fibrate ... is ongoing,” because that trial investigating pemafibrate (Kowa), a novel selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha modulator (or fibrate), has been discontinued.

Chronic kidney disease and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “Traditionally, eGFR is calculated from serum creatinine using a validated formula. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation is preferred. ... Historically, a correction factor for muscle mass was included in a modified equation for African Americans; however, due to various issues with inequities, it was decided to the equation such that it applies to all. Hence, a committee was convened, resulting in the recommendation for immediate implementation of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable in all laboratories in the U.S.” (This is based on an National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation.)

- “Additionally, increased use of cystatin C, especially to confirm estimated GFR in adults who are at risk for or have chronic kidney disease, because combining filtration markers (creatinine and cystatin C) is more accurate and would support better clinical decisions than either marker alone.”

Evidence from clinical trials

The update is based on findings from the following clinical trials:

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD)

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD)

- FIDELITY, a prespecified pooled analysis of FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD

- Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved)

- Effects of Dapagliflozin on Biomarkers, Symptoms and Functional Status in Patients with PRESERVED Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (PRESERVED-HF)

- Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes (PROMINENT).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As it gears up for the first in-person scientific sessions for 3 years, the American Diabetes Association has issued an addendum to its most recent annual clinical practice recommendations published in December 2021, the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, based on recent trial evidence and consensus.

The update informs clinicians about:

- The effect of the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid antagonist (Kerendia) on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

- The effect of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor on heart failure and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation to remove race in the formula for calculating estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

“This is the fifth year that we are able to update the Standards of Care after it has been published through our Living Standards of Care updates, making it possible to give diabetes care providers the most important information and the latest evidence relevant to their practice,” Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, ADA chief scientific and medical officer, said in a press release from the organization.

The addendum, entitled, “Living Standards of Care,” updates Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management” of the 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.

The amendments were approved by the ADA Professional Practice Committee, which is responsible for developing the Standards of Care. The American College of Cardiology reviewed and endorsed the section on CVD and risk management.

The Living Standards Update was published online in Diabetes Care.

CVD and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “For patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease treated with maximum tolerated doses of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, addition of finerenone should be considered to improve cardiovascular outcomes and reduce the risk of chronic kidney disease progression. A”

- “Patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease should be considered for treatment with finerenone to reduce cardiovascular outcomes and the risk of chronic kidney disease progression.”

- “In patients with type 2 diabetes and established heart failure with either preserved or reduced ejection fraction, an SGLT2 inhibitor [with proven benefit in this patient population] is recommended to reduce risk of worsening heart failure, hospitalizations for heart failure, and cardiovascular death. ”

In the section “Statin Treatment,” the addendum no longer states that “a prospective trial of a newer fibrate ... is ongoing,” because that trial investigating pemafibrate (Kowa), a novel selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha modulator (or fibrate), has been discontinued.

Chronic kidney disease and risk management

In the Addendum to Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management,” the committee writes:

- “Traditionally, eGFR is calculated from serum creatinine using a validated formula. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation is preferred. ... Historically, a correction factor for muscle mass was included in a modified equation for African Americans; however, due to various issues with inequities, it was decided to the equation such that it applies to all. Hence, a committee was convened, resulting in the recommendation for immediate implementation of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable in all laboratories in the U.S.” (This is based on an National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology Task Force recommendation.)

- “Additionally, increased use of cystatin C, especially to confirm estimated GFR in adults who are at risk for or have chronic kidney disease, because combining filtration markers (creatinine and cystatin C) is more accurate and would support better clinical decisions than either marker alone.”

Evidence from clinical trials

The update is based on findings from the following clinical trials:

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD)

- Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD)

- FIDELITY, a prespecified pooled analysis of FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD

- Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved)

- Effects of Dapagliflozin on Biomarkers, Symptoms and Functional Status in Patients with PRESERVED Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (PRESERVED-HF)

- Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes (PROMINENT).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Data concerns mount despite ISCHEMIA substudy correction

A long-standing request to clarify data irregularities in a 2021 ISCHEMIA substudy resulted in the publication of one correction, with a second correction in the works.

Further, the lone cardiac surgeon on the ISCHEMIA trial steering committee, T. Bruce Ferguson, MD, has resigned from the committee, citing a series of factors, including an inability to reconcile data in the substudy and two additional ISCHEMIA papers currently under review.

As previously reported, cardiac surgeons Faisal Bakaeen, MD, and Joseph Sabik III, MD, notified the journal Circulation in March that the Dr. Reynolds et al. substudy had inconsistencies between data in the main paper and supplemental tables detailing patients’ coronary artery disease (CAD) and ischemia severity.

The substudy found that CAD severity, classified using the modified Duke Prognostic Index score, predicted 4-year mortality and myocardial infarction in the landmark trial.

Circulation published a correction for the substudy on May 20, explaining that a “formatting error” resulted in data being incorrectly presented in two supplemental tables. It does not mention the surgeons’ letter to the editor, which can be found by clicking the “Q” icon below the paper.

Dr. Bakaeen, from the Cleveland Clinic, and Dr. Sabik, from University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, told this news organization that they submitted a second letter to editor on May 23 stating that “significant discrepancies” persist.

For example, 7.2% of participants (179/2,475) had moderate stenosis in one coronary vessel in the corrected Reynolds paper (Supplemental Tables I and II) versus 23.3% (697/2,986) in the primary ISCHEMIA manuscript published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Table S5).

The number of patients with left main ≥ 50% stenosis is, surprisingly, identical in both manuscripts, at 40, they said, despite the denominator dropping from 3,845 participants in the primary study to 2,475 participants with an evaluable modified Duke Prognostic Index score in the substudy.

The number of participants with previous coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is also hard to reconcile between manuscripts and, importantly, the substudy doesn’t distinguish between lesions bypassed with patent grafts and unbypassed grafts or those with occluded grafts.

“The fact that the authors are working on a second correction is appreciated, but with such numerous inconsistencies, at some point you reach the conclusion that an independent review of the data is the right thing to do for such a high-profile study that received over $100 million of National Institutes of Health support,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “No one should be satisfied or happy if there is any shadow of doubt here regarding the accuracy of the data.”

Speaking to this news organization prior to the first correction, lead substudy author Harmony Reynolds, MD, NYU Langone Health, detailed in depth how the formatting glitch inadvertently upgraded the number of diseased vessels and lesion severity in two supplemental tables.

She noted, as does the correction, that the data were correctly reported in the main manuscript tables and figures and in the remainder of the supplement.

Dr. Reynolds also said they’re in the process of preparing the data for “public sharing soon,” including the Duke Prognostic score at all levels. Dr. Reynolds had not responded by the time of this publication to a request for further details or a timeline.

The surgeons’ first letter to the editor was rejected because it was submitted outside the journal’s 6-week window for letters and was posted as a public comment April 18 via the research platform, Remarq.

Dr. Bakaeen said they were told their second letter was rejected because of Circulation’s “long standing policy” not to publish letters to the editor regarding manuscript corrections but that a correction is being issued.

Circulation editor-in-chief Joseph A. Hill, MD, PhD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said via email that the journal will update its online policies to more clearly state its requirements for publication and that it has been fully transparent with Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik regarding where it is in the current process.

He confirmed the surgeons were told June 1 that “after additional review, the authors have determined that whereas there are no errors, an additional minor correction is warranted to clarify the description of the study population and sample size. This correction will be published soon.”

Dr. Hill thanked Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik for bringing the matter to their attention and said, “It is also important to note that both updates to the Dr. Reynolds et al. paper are published as corrections. However, the results and conclusions of the paper remain unchanged.”

The bigger issue

Importantly, the recent AHA/ACC/SCAI coronary revascularization guidelines used ISCHEMIA data to support downgrading the CABG recommendation from class 1 to class 2B in 3-vessel CAD with normal left ventricular function and from class 1 to 2a in 3-vessel CAD with mild to moderate left ventricular dysfunction.

The trial reported no significant benefit with an initial invasive strategy over medical therapy in stable patients with moderate or severe CAD. European guidelines, however, give CABG a class I recommendation for severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (LAD) involvement.

Dr. Sabik and Dr. Bakaeen say patients with severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal LAD involvement were underrepresented in the randomized trials cited by the guidelines but are the typical CABG patients in modern-day practice.

“That is why it is important to determine the severity of CAD accurately and definitively in ISCHEMIA,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “But the more we look at the data, the more errors we encounter.”

Two U.S. surgical groups that were part of the writing process withdrew support for the revascularization guidelines, as did several international surgical societies, citing the data used to support the changes as well as the makeup of the writing committee.

Dr. Ferguson, now with the medical device manufacturer Perfusio, said he resigned from the ISCHEMIA steering committee on May 8 after being unable to accurately reconcile the ISCHEMIA surgical subset data with the Reynolds substudy and two other ISCHEMIA papers on the CABG subset. At least one of those papers, he noted, was being hurriedly pushed through the review process to counter concerns raised by surgeons regarding interpretation of ISCHEMIA.

“This is the first time in my lengthy career in medicine where a level of political agendaism was actually driving the truck,” he said. “It was appalling to me, and I would have said that if I was an interventional cardiologist looking at the results.”

ISCHEMIA results have also been touted as representing state-of-the-art care around the world, but that didn’t appear to be the case for the surgical subset where, for example, China and India performed most CABGs off pump, and globally there was considerable variation in how surgeons approached surgical revascularization strategies, Dr. Ferguson said. “Whether this variability might impact the guideline discussion and these papers coming out remains to be determined.”

He noted that the study protocol allowed for the ISCHEMIA investigators to evaluate whether the variability in the surgical subset influenced the results by comparing the data to that in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons registry, but this option was never acted upon despite being brought to their attention.

“Something political between 2020 and 2022 has crept into the ISCHEMIA trial mindset gestalt, and I don’t like it,” Dr. Ferguson said. “And this can have enormous consequences.”

Asked whether their letters to Circulation are being used to undermine confidence in the ISCHEMIA findings, Dr. Sabik replied, “It is not about undermining ISCHEMIA, but understanding how applicable ISCHEMIA is to patients having CABG today. Understanding the severity of the CAD in patients enrolled in ISCHEMIA is, therefore, necessary.”

“The authors and Circulation have admitted to errors,” he said. “We want to be sure we understand how severe the errors are.”

“This is just about accuracy in a manuscript that may affect patient treatment and therefore patient lives. We want to make sure it is correct,” Dr. Sabik added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A long-standing request to clarify data irregularities in a 2021 ISCHEMIA substudy resulted in the publication of one correction, with a second correction in the works.

Further, the lone cardiac surgeon on the ISCHEMIA trial steering committee, T. Bruce Ferguson, MD, has resigned from the committee, citing a series of factors, including an inability to reconcile data in the substudy and two additional ISCHEMIA papers currently under review.

As previously reported, cardiac surgeons Faisal Bakaeen, MD, and Joseph Sabik III, MD, notified the journal Circulation in March that the Dr. Reynolds et al. substudy had inconsistencies between data in the main paper and supplemental tables detailing patients’ coronary artery disease (CAD) and ischemia severity.

The substudy found that CAD severity, classified using the modified Duke Prognostic Index score, predicted 4-year mortality and myocardial infarction in the landmark trial.

Circulation published a correction for the substudy on May 20, explaining that a “formatting error” resulted in data being incorrectly presented in two supplemental tables. It does not mention the surgeons’ letter to the editor, which can be found by clicking the “Q” icon below the paper.

Dr. Bakaeen, from the Cleveland Clinic, and Dr. Sabik, from University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, told this news organization that they submitted a second letter to editor on May 23 stating that “significant discrepancies” persist.

For example, 7.2% of participants (179/2,475) had moderate stenosis in one coronary vessel in the corrected Reynolds paper (Supplemental Tables I and II) versus 23.3% (697/2,986) in the primary ISCHEMIA manuscript published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Table S5).

The number of patients with left main ≥ 50% stenosis is, surprisingly, identical in both manuscripts, at 40, they said, despite the denominator dropping from 3,845 participants in the primary study to 2,475 participants with an evaluable modified Duke Prognostic Index score in the substudy.

The number of participants with previous coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is also hard to reconcile between manuscripts and, importantly, the substudy doesn’t distinguish between lesions bypassed with patent grafts and unbypassed grafts or those with occluded grafts.

“The fact that the authors are working on a second correction is appreciated, but with such numerous inconsistencies, at some point you reach the conclusion that an independent review of the data is the right thing to do for such a high-profile study that received over $100 million of National Institutes of Health support,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “No one should be satisfied or happy if there is any shadow of doubt here regarding the accuracy of the data.”

Speaking to this news organization prior to the first correction, lead substudy author Harmony Reynolds, MD, NYU Langone Health, detailed in depth how the formatting glitch inadvertently upgraded the number of diseased vessels and lesion severity in two supplemental tables.

She noted, as does the correction, that the data were correctly reported in the main manuscript tables and figures and in the remainder of the supplement.

Dr. Reynolds also said they’re in the process of preparing the data for “public sharing soon,” including the Duke Prognostic score at all levels. Dr. Reynolds had not responded by the time of this publication to a request for further details or a timeline.

The surgeons’ first letter to the editor was rejected because it was submitted outside the journal’s 6-week window for letters and was posted as a public comment April 18 via the research platform, Remarq.

Dr. Bakaeen said they were told their second letter was rejected because of Circulation’s “long standing policy” not to publish letters to the editor regarding manuscript corrections but that a correction is being issued.

Circulation editor-in-chief Joseph A. Hill, MD, PhD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said via email that the journal will update its online policies to more clearly state its requirements for publication and that it has been fully transparent with Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik regarding where it is in the current process.

He confirmed the surgeons were told June 1 that “after additional review, the authors have determined that whereas there are no errors, an additional minor correction is warranted to clarify the description of the study population and sample size. This correction will be published soon.”

Dr. Hill thanked Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik for bringing the matter to their attention and said, “It is also important to note that both updates to the Dr. Reynolds et al. paper are published as corrections. However, the results and conclusions of the paper remain unchanged.”

The bigger issue

Importantly, the recent AHA/ACC/SCAI coronary revascularization guidelines used ISCHEMIA data to support downgrading the CABG recommendation from class 1 to class 2B in 3-vessel CAD with normal left ventricular function and from class 1 to 2a in 3-vessel CAD with mild to moderate left ventricular dysfunction.

The trial reported no significant benefit with an initial invasive strategy over medical therapy in stable patients with moderate or severe CAD. European guidelines, however, give CABG a class I recommendation for severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (LAD) involvement.

Dr. Sabik and Dr. Bakaeen say patients with severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal LAD involvement were underrepresented in the randomized trials cited by the guidelines but are the typical CABG patients in modern-day practice.

“That is why it is important to determine the severity of CAD accurately and definitively in ISCHEMIA,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “But the more we look at the data, the more errors we encounter.”

Two U.S. surgical groups that were part of the writing process withdrew support for the revascularization guidelines, as did several international surgical societies, citing the data used to support the changes as well as the makeup of the writing committee.

Dr. Ferguson, now with the medical device manufacturer Perfusio, said he resigned from the ISCHEMIA steering committee on May 8 after being unable to accurately reconcile the ISCHEMIA surgical subset data with the Reynolds substudy and two other ISCHEMIA papers on the CABG subset. At least one of those papers, he noted, was being hurriedly pushed through the review process to counter concerns raised by surgeons regarding interpretation of ISCHEMIA.

“This is the first time in my lengthy career in medicine where a level of political agendaism was actually driving the truck,” he said. “It was appalling to me, and I would have said that if I was an interventional cardiologist looking at the results.”

ISCHEMIA results have also been touted as representing state-of-the-art care around the world, but that didn’t appear to be the case for the surgical subset where, for example, China and India performed most CABGs off pump, and globally there was considerable variation in how surgeons approached surgical revascularization strategies, Dr. Ferguson said. “Whether this variability might impact the guideline discussion and these papers coming out remains to be determined.”

He noted that the study protocol allowed for the ISCHEMIA investigators to evaluate whether the variability in the surgical subset influenced the results by comparing the data to that in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons registry, but this option was never acted upon despite being brought to their attention.

“Something political between 2020 and 2022 has crept into the ISCHEMIA trial mindset gestalt, and I don’t like it,” Dr. Ferguson said. “And this can have enormous consequences.”

Asked whether their letters to Circulation are being used to undermine confidence in the ISCHEMIA findings, Dr. Sabik replied, “It is not about undermining ISCHEMIA, but understanding how applicable ISCHEMIA is to patients having CABG today. Understanding the severity of the CAD in patients enrolled in ISCHEMIA is, therefore, necessary.”

“The authors and Circulation have admitted to errors,” he said. “We want to be sure we understand how severe the errors are.”

“This is just about accuracy in a manuscript that may affect patient treatment and therefore patient lives. We want to make sure it is correct,” Dr. Sabik added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A long-standing request to clarify data irregularities in a 2021 ISCHEMIA substudy resulted in the publication of one correction, with a second correction in the works.

Further, the lone cardiac surgeon on the ISCHEMIA trial steering committee, T. Bruce Ferguson, MD, has resigned from the committee, citing a series of factors, including an inability to reconcile data in the substudy and two additional ISCHEMIA papers currently under review.

As previously reported, cardiac surgeons Faisal Bakaeen, MD, and Joseph Sabik III, MD, notified the journal Circulation in March that the Dr. Reynolds et al. substudy had inconsistencies between data in the main paper and supplemental tables detailing patients’ coronary artery disease (CAD) and ischemia severity.

The substudy found that CAD severity, classified using the modified Duke Prognostic Index score, predicted 4-year mortality and myocardial infarction in the landmark trial.

Circulation published a correction for the substudy on May 20, explaining that a “formatting error” resulted in data being incorrectly presented in two supplemental tables. It does not mention the surgeons’ letter to the editor, which can be found by clicking the “Q” icon below the paper.

Dr. Bakaeen, from the Cleveland Clinic, and Dr. Sabik, from University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, told this news organization that they submitted a second letter to editor on May 23 stating that “significant discrepancies” persist.

For example, 7.2% of participants (179/2,475) had moderate stenosis in one coronary vessel in the corrected Reynolds paper (Supplemental Tables I and II) versus 23.3% (697/2,986) in the primary ISCHEMIA manuscript published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Table S5).

The number of patients with left main ≥ 50% stenosis is, surprisingly, identical in both manuscripts, at 40, they said, despite the denominator dropping from 3,845 participants in the primary study to 2,475 participants with an evaluable modified Duke Prognostic Index score in the substudy.

The number of participants with previous coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is also hard to reconcile between manuscripts and, importantly, the substudy doesn’t distinguish between lesions bypassed with patent grafts and unbypassed grafts or those with occluded grafts.

“The fact that the authors are working on a second correction is appreciated, but with such numerous inconsistencies, at some point you reach the conclusion that an independent review of the data is the right thing to do for such a high-profile study that received over $100 million of National Institutes of Health support,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “No one should be satisfied or happy if there is any shadow of doubt here regarding the accuracy of the data.”

Speaking to this news organization prior to the first correction, lead substudy author Harmony Reynolds, MD, NYU Langone Health, detailed in depth how the formatting glitch inadvertently upgraded the number of diseased vessels and lesion severity in two supplemental tables.

She noted, as does the correction, that the data were correctly reported in the main manuscript tables and figures and in the remainder of the supplement.

Dr. Reynolds also said they’re in the process of preparing the data for “public sharing soon,” including the Duke Prognostic score at all levels. Dr. Reynolds had not responded by the time of this publication to a request for further details or a timeline.

The surgeons’ first letter to the editor was rejected because it was submitted outside the journal’s 6-week window for letters and was posted as a public comment April 18 via the research platform, Remarq.

Dr. Bakaeen said they were told their second letter was rejected because of Circulation’s “long standing policy” not to publish letters to the editor regarding manuscript corrections but that a correction is being issued.

Circulation editor-in-chief Joseph A. Hill, MD, PhD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said via email that the journal will update its online policies to more clearly state its requirements for publication and that it has been fully transparent with Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik regarding where it is in the current process.

He confirmed the surgeons were told June 1 that “after additional review, the authors have determined that whereas there are no errors, an additional minor correction is warranted to clarify the description of the study population and sample size. This correction will be published soon.”

Dr. Hill thanked Dr. Bakaeen and Dr. Sabik for bringing the matter to their attention and said, “It is also important to note that both updates to the Dr. Reynolds et al. paper are published as corrections. However, the results and conclusions of the paper remain unchanged.”

The bigger issue

Importantly, the recent AHA/ACC/SCAI coronary revascularization guidelines used ISCHEMIA data to support downgrading the CABG recommendation from class 1 to class 2B in 3-vessel CAD with normal left ventricular function and from class 1 to 2a in 3-vessel CAD with mild to moderate left ventricular dysfunction.

The trial reported no significant benefit with an initial invasive strategy over medical therapy in stable patients with moderate or severe CAD. European guidelines, however, give CABG a class I recommendation for severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (LAD) involvement.

Dr. Sabik and Dr. Bakaeen say patients with severe three- or two-vessel disease with proximal LAD involvement were underrepresented in the randomized trials cited by the guidelines but are the typical CABG patients in modern-day practice.

“That is why it is important to determine the severity of CAD accurately and definitively in ISCHEMIA,” Dr. Bakaeen said. “But the more we look at the data, the more errors we encounter.”

Two U.S. surgical groups that were part of the writing process withdrew support for the revascularization guidelines, as did several international surgical societies, citing the data used to support the changes as well as the makeup of the writing committee.

Dr. Ferguson, now with the medical device manufacturer Perfusio, said he resigned from the ISCHEMIA steering committee on May 8 after being unable to accurately reconcile the ISCHEMIA surgical subset data with the Reynolds substudy and two other ISCHEMIA papers on the CABG subset. At least one of those papers, he noted, was being hurriedly pushed through the review process to counter concerns raised by surgeons regarding interpretation of ISCHEMIA.

“This is the first time in my lengthy career in medicine where a level of political agendaism was actually driving the truck,” he said. “It was appalling to me, and I would have said that if I was an interventional cardiologist looking at the results.”

ISCHEMIA results have also been touted as representing state-of-the-art care around the world, but that didn’t appear to be the case for the surgical subset where, for example, China and India performed most CABGs off pump, and globally there was considerable variation in how surgeons approached surgical revascularization strategies, Dr. Ferguson said. “Whether this variability might impact the guideline discussion and these papers coming out remains to be determined.”

He noted that the study protocol allowed for the ISCHEMIA investigators to evaluate whether the variability in the surgical subset influenced the results by comparing the data to that in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons registry, but this option was never acted upon despite being brought to their attention.

“Something political between 2020 and 2022 has crept into the ISCHEMIA trial mindset gestalt, and I don’t like it,” Dr. Ferguson said. “And this can have enormous consequences.”

Asked whether their letters to Circulation are being used to undermine confidence in the ISCHEMIA findings, Dr. Sabik replied, “It is not about undermining ISCHEMIA, but understanding how applicable ISCHEMIA is to patients having CABG today. Understanding the severity of the CAD in patients enrolled in ISCHEMIA is, therefore, necessary.”

“The authors and Circulation have admitted to errors,” he said. “We want to be sure we understand how severe the errors are.”

“This is just about accuracy in a manuscript that may affect patient treatment and therefore patient lives. We want to make sure it is correct,” Dr. Sabik added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CTO PCI success rates rising, with blip during COVID-19, registry shows

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

FROM SCAI 2022

Antipsychotic tied to dose-related weight gain, higher cholesterol

new research suggests.

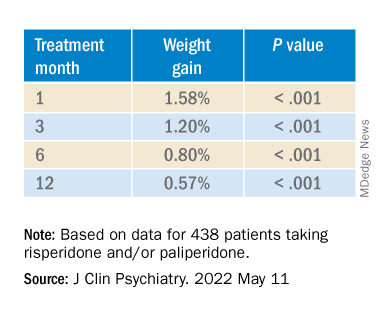

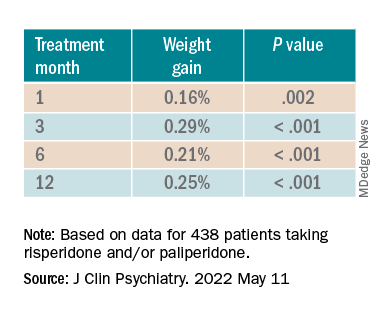

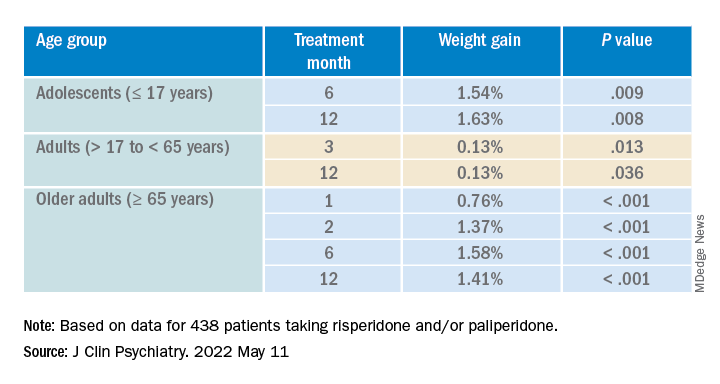

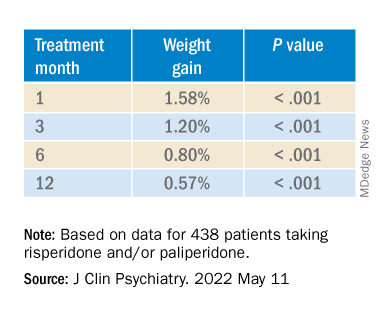

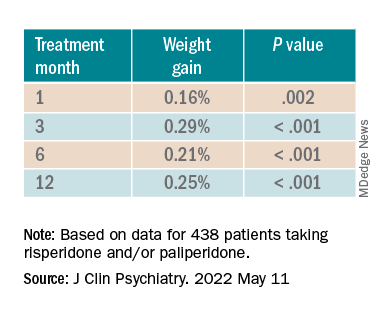

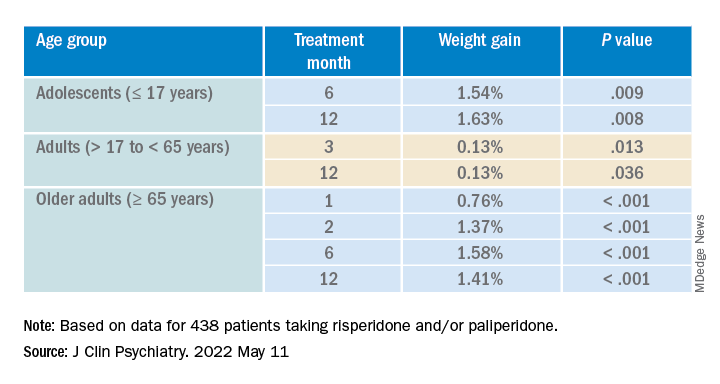

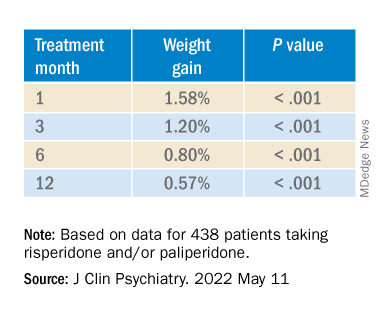

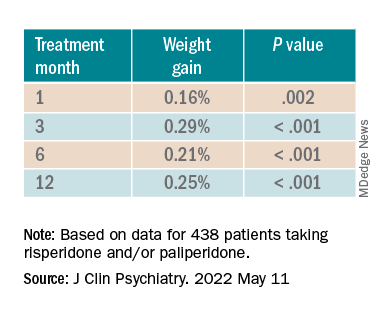

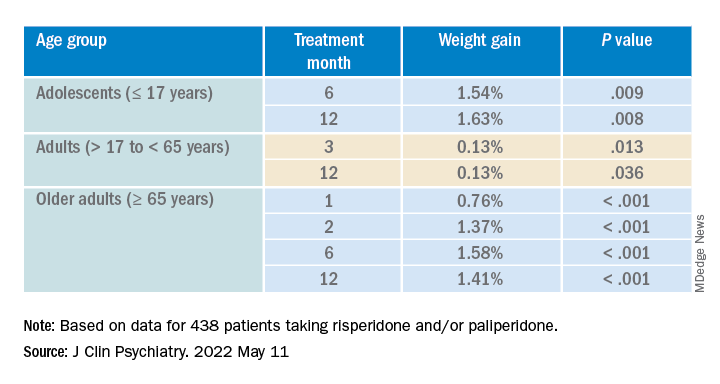

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”