User login

Spitz Nevus and Atypical Spitzoid Neoplasm

Maria Miteva, MD, and Rossitza Lazova, MD

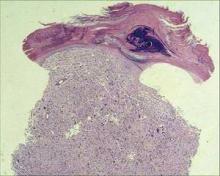

Spitz nevus (SN) and Spitzoid malignant melanoma (SMM) represent benign and malignant counterparts at both ends of the spectrum of Spitzoid lesions. Atypical Spitzoid neoplasm (ASN) is a poorly defined and characterized category of melanocytic tumors with histologic features of both benign Spitz nevi and malignant melanomas. The group of ASN represents a mixture of Spitz nevi with atypical features and Spitzoid melanomas. However, at the current moment in time, histopathologists are not capable of differentiating between the 2 in some cases and are forced to place them in this ambiguous category, where the behavior of these lesions cannot be predicted with certainty. Because this group encompasses both benign and malignant lesions, and perhaps also a separate category of melanocytic tumors that behave better than conventional melanomas, some of these neoplasms can metastasize and kill patients, whereas others have no metastatic potential, and yet others might only metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Although diagnostic accuracy has improved over the years, many of these lesions remain controversial, and there is still poor interobserver agreement in classifying problematic Spitzoid lesions among experienced dermatopathologists. The objective of this review article is to summarize the most relevant information about SN and ASNs. At this time histologic examination remains the golden standard for diagnosing these melanocytic neoplasms. We therefore concentrate on the histopathologic, clinical, and dermoscopic aspects of these lesions. We also review the most recent advances in immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostics as well as discuss the controversies and dilemma regarding whether to consider sentinel lymph node biopsy for diagnostically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Maria Miteva, MD, and Rossitza Lazova, MD

Spitz nevus (SN) and Spitzoid malignant melanoma (SMM) represent benign and malignant counterparts at both ends of the spectrum of Spitzoid lesions. Atypical Spitzoid neoplasm (ASN) is a poorly defined and characterized category of melanocytic tumors with histologic features of both benign Spitz nevi and malignant melanomas. The group of ASN represents a mixture of Spitz nevi with atypical features and Spitzoid melanomas. However, at the current moment in time, histopathologists are not capable of differentiating between the 2 in some cases and are forced to place them in this ambiguous category, where the behavior of these lesions cannot be predicted with certainty. Because this group encompasses both benign and malignant lesions, and perhaps also a separate category of melanocytic tumors that behave better than conventional melanomas, some of these neoplasms can metastasize and kill patients, whereas others have no metastatic potential, and yet others might only metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Although diagnostic accuracy has improved over the years, many of these lesions remain controversial, and there is still poor interobserver agreement in classifying problematic Spitzoid lesions among experienced dermatopathologists. The objective of this review article is to summarize the most relevant information about SN and ASNs. At this time histologic examination remains the golden standard for diagnosing these melanocytic neoplasms. We therefore concentrate on the histopathologic, clinical, and dermoscopic aspects of these lesions. We also review the most recent advances in immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostics as well as discuss the controversies and dilemma regarding whether to consider sentinel lymph node biopsy for diagnostically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Maria Miteva, MD, and Rossitza Lazova, MD

Spitz nevus (SN) and Spitzoid malignant melanoma (SMM) represent benign and malignant counterparts at both ends of the spectrum of Spitzoid lesions. Atypical Spitzoid neoplasm (ASN) is a poorly defined and characterized category of melanocytic tumors with histologic features of both benign Spitz nevi and malignant melanomas. The group of ASN represents a mixture of Spitz nevi with atypical features and Spitzoid melanomas. However, at the current moment in time, histopathologists are not capable of differentiating between the 2 in some cases and are forced to place them in this ambiguous category, where the behavior of these lesions cannot be predicted with certainty. Because this group encompasses both benign and malignant lesions, and perhaps also a separate category of melanocytic tumors that behave better than conventional melanomas, some of these neoplasms can metastasize and kill patients, whereas others have no metastatic potential, and yet others might only metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Although diagnostic accuracy has improved over the years, many of these lesions remain controversial, and there is still poor interobserver agreement in classifying problematic Spitzoid lesions among experienced dermatopathologists. The objective of this review article is to summarize the most relevant information about SN and ASNs. At this time histologic examination remains the golden standard for diagnosing these melanocytic neoplasms. We therefore concentrate on the histopathologic, clinical, and dermoscopic aspects of these lesions. We also review the most recent advances in immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostics as well as discuss the controversies and dilemma regarding whether to consider sentinel lymph node biopsy for diagnostically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Today, more than half a century after the first description of Spitz nevus (SN) and despite the presence of more refined criteria and molecular diagnostic tools, the distinction between SN with atypical features and Spitzoid malignant melanoma (SMM) remains difficult at times, and prediction of the biological behavior of these lesions is often utterly impossible.

Noninvasive Imaging Technologies in the Diagnosis of Melanoma

Steven Q. Wang, MD, and Pantea Hashemi, MD

The incidence of melanoma has increased during the last few years. Melanoma care and survival can be improved by early diagnosis, which can be facilitated by the use of noninvasive imaging modalities. Here we review 5 modalities available in clinical practice. Total body photography is used to follow patients at high risk for melanoma by detecting new lesions or subtle changes in existing lesions. Dermoscopy is an effective noninvasive technique for the early recognition of melanoma by allowing clinicians to visualize subsurface structures. Computer-assisted diagnostic devices are fully automated analysis systems with the capacity to classify lesions as benign or malignant with limited involvement from clinicians. Confocal scanning laser microscopy is an in vivo and noninvasive technology that examines the skin at a resolution comparable to that of histology. High-resolution ultrasound is an adjunct diagnostic aid mainly for the early detection of lymph node metastasis. Applications and limitations of each technology are discussed.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Steven Q. Wang, MD, and Pantea Hashemi, MD

The incidence of melanoma has increased during the last few years. Melanoma care and survival can be improved by early diagnosis, which can be facilitated by the use of noninvasive imaging modalities. Here we review 5 modalities available in clinical practice. Total body photography is used to follow patients at high risk for melanoma by detecting new lesions or subtle changes in existing lesions. Dermoscopy is an effective noninvasive technique for the early recognition of melanoma by allowing clinicians to visualize subsurface structures. Computer-assisted diagnostic devices are fully automated analysis systems with the capacity to classify lesions as benign or malignant with limited involvement from clinicians. Confocal scanning laser microscopy is an in vivo and noninvasive technology that examines the skin at a resolution comparable to that of histology. High-resolution ultrasound is an adjunct diagnostic aid mainly for the early detection of lymph node metastasis. Applications and limitations of each technology are discussed.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Steven Q. Wang, MD, and Pantea Hashemi, MD

The incidence of melanoma has increased during the last few years. Melanoma care and survival can be improved by early diagnosis, which can be facilitated by the use of noninvasive imaging modalities. Here we review 5 modalities available in clinical practice. Total body photography is used to follow patients at high risk for melanoma by detecting new lesions or subtle changes in existing lesions. Dermoscopy is an effective noninvasive technique for the early recognition of melanoma by allowing clinicians to visualize subsurface structures. Computer-assisted diagnostic devices are fully automated analysis systems with the capacity to classify lesions as benign or malignant with limited involvement from clinicians. Confocal scanning laser microscopy is an in vivo and noninvasive technology that examines the skin at a resolution comparable to that of histology. High-resolution ultrasound is an adjunct diagnostic aid mainly for the early detection of lymph node metastasis. Applications and limitations of each technology are discussed.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Vitamin D Levels, Dietary Intake, and Photoprotective Behaviors Among Patients With Skin Cancer

Laura K. DeLong, MD, MPH, Sarah Wetherington, BS, Nikki Hill, MD, Meena Kumari, MD, Bryan Gammon, MD, Scott Dunbar, MD, Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, and Suephy C. Chen, MD, MS

Photoprotection against ultraviolet light is an important part of our armamentarium against actinically derived skin cancers. However, there has been concern that adherence to photoprotection may lead to low vitamin D status, leading to negative effects on patients’ health. In this work we discuss previous findings in this area, which do not give a clear picture as to the relationship between vitamin D levels and photoprotection measures, as well as research performed by the authors, who did not detect a relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and adherence to photoprotection measures in subjects with skin cancer, as assessed by the use of sunscreen, clothing, hats, sunglasses, and umbrellas/shade through the Sun Protection Habits Index. Subjects who took vitamin D oral supplementation had greater serum 25(OH)D levels than those who did not, whereas dietary intake through foods did not predict 25(OH)D levels in the authors’ study. However, there was a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in the authors’ study population, highlighting the importance of assessing vitamin D status and recommending oral vitamin D supplementation when indicated.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Laura K. DeLong, MD, MPH, Sarah Wetherington, BS, Nikki Hill, MD, Meena Kumari, MD, Bryan Gammon, MD, Scott Dunbar, MD, Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, and Suephy C. Chen, MD, MS

Photoprotection against ultraviolet light is an important part of our armamentarium against actinically derived skin cancers. However, there has been concern that adherence to photoprotection may lead to low vitamin D status, leading to negative effects on patients’ health. In this work we discuss previous findings in this area, which do not give a clear picture as to the relationship between vitamin D levels and photoprotection measures, as well as research performed by the authors, who did not detect a relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and adherence to photoprotection measures in subjects with skin cancer, as assessed by the use of sunscreen, clothing, hats, sunglasses, and umbrellas/shade through the Sun Protection Habits Index. Subjects who took vitamin D oral supplementation had greater serum 25(OH)D levels than those who did not, whereas dietary intake through foods did not predict 25(OH)D levels in the authors’ study. However, there was a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in the authors’ study population, highlighting the importance of assessing vitamin D status and recommending oral vitamin D supplementation when indicated.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Laura K. DeLong, MD, MPH, Sarah Wetherington, BS, Nikki Hill, MD, Meena Kumari, MD, Bryan Gammon, MD, Scott Dunbar, MD, Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, and Suephy C. Chen, MD, MS

Photoprotection against ultraviolet light is an important part of our armamentarium against actinically derived skin cancers. However, there has been concern that adherence to photoprotection may lead to low vitamin D status, leading to negative effects on patients’ health. In this work we discuss previous findings in this area, which do not give a clear picture as to the relationship between vitamin D levels and photoprotection measures, as well as research performed by the authors, who did not detect a relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and adherence to photoprotection measures in subjects with skin cancer, as assessed by the use of sunscreen, clothing, hats, sunglasses, and umbrellas/shade through the Sun Protection Habits Index. Subjects who took vitamin D oral supplementation had greater serum 25(OH)D levels than those who did not, whereas dietary intake through foods did not predict 25(OH)D levels in the authors’ study. However, there was a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in the authors’ study population, highlighting the importance of assessing vitamin D status and recommending oral vitamin D supplementation when indicated.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

In this work we will briefly review the issues raised by these previous papers but will focus on photoprotective behaviors, particularly in skin cancer populations, because these patients are likely the most motivated to comply with photoprotection after their diagnosis.

Genetic Determinants of Cutaneous Melanoma Predisposition

Durga Udayakumar, PhD; Bisundev Mahato, Michele Gabree, MGC and

Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD

In the last 2 decades, advances in genomic technologies and molecular biology have accelerated the identification of multiple genetic loci that confer risk for cutaneous melanoma. The risk alleles range from rarely occurring, high-risk variants with a strong familial predisposition to low-risk to moderate-risk variants with modest melanoma association. Although the high-risk alleles are limited to the CDKN2A and CDK4 loci, the authors of recent genome-wide association studies have uncovered a set of variants in pigmentation loci that contribute to low risk. A biological validation of these new findings would provide greater understanding of the disease. In this review we describe some of the important risk loci and their association to risk of developing cutaneous melanoma and also address the current clinical challenges in CDKN2A genetic testing.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Durga Udayakumar, PhD; Bisundev Mahato, Michele Gabree, MGC and

Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD

In the last 2 decades, advances in genomic technologies and molecular biology have accelerated the identification of multiple genetic loci that confer risk for cutaneous melanoma. The risk alleles range from rarely occurring, high-risk variants with a strong familial predisposition to low-risk to moderate-risk variants with modest melanoma association. Although the high-risk alleles are limited to the CDKN2A and CDK4 loci, the authors of recent genome-wide association studies have uncovered a set of variants in pigmentation loci that contribute to low risk. A biological validation of these new findings would provide greater understanding of the disease. In this review we describe some of the important risk loci and their association to risk of developing cutaneous melanoma and also address the current clinical challenges in CDKN2A genetic testing.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Durga Udayakumar, PhD; Bisundev Mahato, Michele Gabree, MGC and

Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD

In the last 2 decades, advances in genomic technologies and molecular biology have accelerated the identification of multiple genetic loci that confer risk for cutaneous melanoma. The risk alleles range from rarely occurring, high-risk variants with a strong familial predisposition to low-risk to moderate-risk variants with modest melanoma association. Although the high-risk alleles are limited to the CDKN2A and CDK4 loci, the authors of recent genome-wide association studies have uncovered a set of variants in pigmentation loci that contribute to low risk. A biological validation of these new findings would provide greater understanding of the disease. In this review we describe some of the important risk loci and their association to risk of developing cutaneous melanoma and also address the current clinical challenges in CDKN2A genetic testing.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Targeted Molecular Therapy in Melanoma

Igor Puzanov, MD, MSCI, and Keith T. Flaherty, MD

Immunotherapy and chemotherapy benefit few patients with metastatic melanoma, and even fewer experience durable survival benefit. These poor results may come from treating all melanomas as though they are biologically homogeneous. Recently, it has been shown that targeting specific activated tyrosine kinases (oncogenes) can have striking clinical benefits in patients with melanoma. In 2002, a V600E mutation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase was described as present in more than 50% of all melanomas. The mutation appeared to confer a dependency by the melanoma cancer cell on activated signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. The frequency and focality of this mutation (>95% of all BRAF mutations being at V600 position) suggested its importance in melanoma pathophysiology and potential as a target for therapy. The recent results of a phase 1 study with PLX4032/RG7204, a small molecule RAF inhibitor, confirm this hypothesis. Mucosal and acral-lentiginous melanomas, comprising 3% of all melanomas, frequently harbor activating mutations of c-kit and drugs targeting this mutation seem to confer similar benefits for these types of tumors. Here we provide an overview of the targeted therapy development in melanoma with emphasis on BRAF inhibition because of its prevalence and possibility of transforming the care of many melanoma patients.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Igor Puzanov, MD, MSCI, and Keith T. Flaherty, MD

Immunotherapy and chemotherapy benefit few patients with metastatic melanoma, and even fewer experience durable survival benefit. These poor results may come from treating all melanomas as though they are biologically homogeneous. Recently, it has been shown that targeting specific activated tyrosine kinases (oncogenes) can have striking clinical benefits in patients with melanoma. In 2002, a V600E mutation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase was described as present in more than 50% of all melanomas. The mutation appeared to confer a dependency by the melanoma cancer cell on activated signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. The frequency and focality of this mutation (>95% of all BRAF mutations being at V600 position) suggested its importance in melanoma pathophysiology and potential as a target for therapy. The recent results of a phase 1 study with PLX4032/RG7204, a small molecule RAF inhibitor, confirm this hypothesis. Mucosal and acral-lentiginous melanomas, comprising 3% of all melanomas, frequently harbor activating mutations of c-kit and drugs targeting this mutation seem to confer similar benefits for these types of tumors. Here we provide an overview of the targeted therapy development in melanoma with emphasis on BRAF inhibition because of its prevalence and possibility of transforming the care of many melanoma patients.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Igor Puzanov, MD, MSCI, and Keith T. Flaherty, MD

Immunotherapy and chemotherapy benefit few patients with metastatic melanoma, and even fewer experience durable survival benefit. These poor results may come from treating all melanomas as though they are biologically homogeneous. Recently, it has been shown that targeting specific activated tyrosine kinases (oncogenes) can have striking clinical benefits in patients with melanoma. In 2002, a V600E mutation of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase was described as present in more than 50% of all melanomas. The mutation appeared to confer a dependency by the melanoma cancer cell on activated signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. The frequency and focality of this mutation (>95% of all BRAF mutations being at V600 position) suggested its importance in melanoma pathophysiology and potential as a target for therapy. The recent results of a phase 1 study with PLX4032/RG7204, a small molecule RAF inhibitor, confirm this hypothesis. Mucosal and acral-lentiginous melanomas, comprising 3% of all melanomas, frequently harbor activating mutations of c-kit and drugs targeting this mutation seem to confer similar benefits for these types of tumors. Here we provide an overview of the targeted therapy development in melanoma with emphasis on BRAF inhibition because of its prevalence and possibility of transforming the care of many melanoma patients.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Skin of Color: What Every Dark Skinned Patient Should Know

Many blogs, articles, and tip sheets offer suggestions for keeping skin youthful and breakout free. But often the advice doesn’t apply to all skin types. Below are nine skin care tips modified for darker skin that you can share with your patients.

1. Don’t over wash.

Washing the face once a day to remove makeup, dirt, and bacteria can be helpful to avoid breakouts, especially in acne prone skin. However, it is important to remind patients to avoid over washing, as this may dry out the skin causing increased irritation, and may even cause wrinkles to look more prominent.

Sebum production decreases with age, especially after menopause in women. It may also be decreased in black patients, compared with white patients, as shown in a recent study (Cutis 2004;73:392-396), although the data were not statistically significant.

Patients should exercise caution when applying antiaging products after washing because washing allows antiagers to penetrate deeper, leading to faster results in most skin types, but may also lead to increased irritation and then postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in darker skin.

Gentle cleansers are best, unless the skin is especially acne prone. In this case, anti-acne cleansers with ingredients like salicylic acid, benzoyl peroxide, or glycolic acid may be useful. To refresh skin, a splash of lukewarm water should do.

2. Apply products with a lower pH.

Studies have shown pH to be lower in darker skin, compared with lighter skin. For darker skin, products that are slightly acidic, such as those that contain mild glycolic acid, can help maintain the skin’s pH balance and maintain homeostasis and barrier integrity.

3. Be UV obsessed.

While the epidermis of darker skin contains more melanin content and has increased melanosomal dispersion than lighter skin—providing increased protection against UV-induced skin cancers and photoaging—UV damage can still occur.

Many patients with darker skin feel they are immune to skin cancer. Patients with darker skin, while diagnosed less frequently with melanoma, die at an increased frequency from the disease because of later diagnosis. Using a sunscreen that is SPF 30 or higher that blocks both UVA and UVB wavelengths is essential.

Patients should be reminded that nothing is more important than wearing sunscreen every day to promote younger-looking skin and prevent skin cancer.

Sunscreens, especially those with a higher SPF, often do not rub in well on darker skin. Using a sunscreen with chemical blockers, or micronized physical blockers (zinc and titanium dioxide), may go on less chalky and rub in more smoothly.

Sun exposure in darker skin also leads to prolonged postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after any skin insult. Even 10 minutes of daily exposure to UVA can cause changes that lead to wrinkles and sunspots in as few as 12 weeks.

Also, advise patients to eat foods that are rich in vitamin D to avoid deficiency.

4. Manage stress.

Emotional upheavals can make a patient’s skin look 5 years older than his or her chronological age. Constant anxiety increases the stress hormone cortisol, which causes inflammation that breaks down collagen. It also triggers a chain of responses that can lead to facial redness and acne flare-ups. To quell inflammation, advise patients to eat antioxidant-rich foods such as berries, oranges, and asparagus.

5. Use a retinoid.

Vitamin A derivatives, such as topical retinoids, speed cell turnover and collagen growth to smooth fine lines and wrinkles and fade brown spots. Prescription-strength retinoids provide the fastest results—your patient should start to see changes in about a month.

To help skin adjust to any redness or peeling, advise patients to apply a pea-size drop to the face every third night, building up to nightly use. Milder over-the-counter versions are gentler, although it can take up to 3 months for users to see noticeable results.

Redness and peeling should absolutely be avoided in darker skin to avoid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, so retinoids, while helpful, should be used cautiously.

6. Update your routine.

Advising patients to alter just one thing in their regimen every 6-12 months jump starts more impressive improvements in tone and texture. When products are applied consistently, skin slides into maintenance mode after about a year. To keep skin primed for rejuvenation, tell patients to substitute a cream that contains alpha hydroxy acids in place of a retinoid twice a week to boost benefits. Or, you can bump up the patient’s OTC retinoid to a prescription product.

7. Eat omega-3 fats.

These “good fats,” found in foods such as salmon, flaxseed, and almonds, boost hydration, which keeps skin supple and firm. The same is not true, however, of the saturated fat in dairy products and meats, which increase free-radical damage that makes skin more susceptible to aging. Advise patients to limit their intake of saturated fat to about 17 g per day.

8. Exercise regularly.

Studies find that women who work out regularly have firmer skin than non-exercisers. The reason: Exercise infuses skin with oxygen and nutrients needed for collagen production. Patients who aim to keep skin toned should make time for at least three, 30-minute, heart-pumping workouts per week.

9. Wash your hair.

Curly hair cannot be washed as often as straight hair because it dries out more readily. However, decreased hair washing leads to increased scalp sebum production, which can lead to increased breakouts.

If hair cannot be washed, patients should wrap their hair at night so it does not touch the face, and they should change their pillow cases frequently. In addition, many persons of African descent apply oils and pomades to their hair to keep it soft and manageable. Here, hair wrapping or increased washing is also essential to avoid “pomade acne.”

Many blogs, articles, and tip sheets offer suggestions for keeping skin youthful and breakout free. But often the advice doesn’t apply to all skin types. Below are nine skin care tips modified for darker skin that you can share with your patients.

1. Don’t over wash.

Washing the face once a day to remove makeup, dirt, and bacteria can be helpful to avoid breakouts, especially in acne prone skin. However, it is important to remind patients to avoid over washing, as this may dry out the skin causing increased irritation, and may even cause wrinkles to look more prominent.

Sebum production decreases with age, especially after menopause in women. It may also be decreased in black patients, compared with white patients, as shown in a recent study (Cutis 2004;73:392-396), although the data were not statistically significant.

Patients should exercise caution when applying antiaging products after washing because washing allows antiagers to penetrate deeper, leading to faster results in most skin types, but may also lead to increased irritation and then postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in darker skin.

Gentle cleansers are best, unless the skin is especially acne prone. In this case, anti-acne cleansers with ingredients like salicylic acid, benzoyl peroxide, or glycolic acid may be useful. To refresh skin, a splash of lukewarm water should do.

2. Apply products with a lower pH.

Studies have shown pH to be lower in darker skin, compared with lighter skin. For darker skin, products that are slightly acidic, such as those that contain mild glycolic acid, can help maintain the skin’s pH balance and maintain homeostasis and barrier integrity.

3. Be UV obsessed.

While the epidermis of darker skin contains more melanin content and has increased melanosomal dispersion than lighter skin—providing increased protection against UV-induced skin cancers and photoaging—UV damage can still occur.

Many patients with darker skin feel they are immune to skin cancer. Patients with darker skin, while diagnosed less frequently with melanoma, die at an increased frequency from the disease because of later diagnosis. Using a sunscreen that is SPF 30 or higher that blocks both UVA and UVB wavelengths is essential.

Patients should be reminded that nothing is more important than wearing sunscreen every day to promote younger-looking skin and prevent skin cancer.

Sunscreens, especially those with a higher SPF, often do not rub in well on darker skin. Using a sunscreen with chemical blockers, or micronized physical blockers (zinc and titanium dioxide), may go on less chalky and rub in more smoothly.

Sun exposure in darker skin also leads to prolonged postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after any skin insult. Even 10 minutes of daily exposure to UVA can cause changes that lead to wrinkles and sunspots in as few as 12 weeks.

Also, advise patients to eat foods that are rich in vitamin D to avoid deficiency.

4. Manage stress.

Emotional upheavals can make a patient’s skin look 5 years older than his or her chronological age. Constant anxiety increases the stress hormone cortisol, which causes inflammation that breaks down collagen. It also triggers a chain of responses that can lead to facial redness and acne flare-ups. To quell inflammation, advise patients to eat antioxidant-rich foods such as berries, oranges, and asparagus.

5. Use a retinoid.

Vitamin A derivatives, such as topical retinoids, speed cell turnover and collagen growth to smooth fine lines and wrinkles and fade brown spots. Prescription-strength retinoids provide the fastest results—your patient should start to see changes in about a month.

To help skin adjust to any redness or peeling, advise patients to apply a pea-size drop to the face every third night, building up to nightly use. Milder over-the-counter versions are gentler, although it can take up to 3 months for users to see noticeable results.

Redness and peeling should absolutely be avoided in darker skin to avoid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, so retinoids, while helpful, should be used cautiously.

6. Update your routine.

Advising patients to alter just one thing in their regimen every 6-12 months jump starts more impressive improvements in tone and texture. When products are applied consistently, skin slides into maintenance mode after about a year. To keep skin primed for rejuvenation, tell patients to substitute a cream that contains alpha hydroxy acids in place of a retinoid twice a week to boost benefits. Or, you can bump up the patient’s OTC retinoid to a prescription product.

7. Eat omega-3 fats.

These “good fats,” found in foods such as salmon, flaxseed, and almonds, boost hydration, which keeps skin supple and firm. The same is not true, however, of the saturated fat in dairy products and meats, which increase free-radical damage that makes skin more susceptible to aging. Advise patients to limit their intake of saturated fat to about 17 g per day.

8. Exercise regularly.

Studies find that women who work out regularly have firmer skin than non-exercisers. The reason: Exercise infuses skin with oxygen and nutrients needed for collagen production. Patients who aim to keep skin toned should make time for at least three, 30-minute, heart-pumping workouts per week.

9. Wash your hair.

Curly hair cannot be washed as often as straight hair because it dries out more readily. However, decreased hair washing leads to increased scalp sebum production, which can lead to increased breakouts.

If hair cannot be washed, patients should wrap their hair at night so it does not touch the face, and they should change their pillow cases frequently. In addition, many persons of African descent apply oils and pomades to their hair to keep it soft and manageable. Here, hair wrapping or increased washing is also essential to avoid “pomade acne.”

Many blogs, articles, and tip sheets offer suggestions for keeping skin youthful and breakout free. But often the advice doesn’t apply to all skin types. Below are nine skin care tips modified for darker skin that you can share with your patients.

1. Don’t over wash.

Washing the face once a day to remove makeup, dirt, and bacteria can be helpful to avoid breakouts, especially in acne prone skin. However, it is important to remind patients to avoid over washing, as this may dry out the skin causing increased irritation, and may even cause wrinkles to look more prominent.

Sebum production decreases with age, especially after menopause in women. It may also be decreased in black patients, compared with white patients, as shown in a recent study (Cutis 2004;73:392-396), although the data were not statistically significant.

Patients should exercise caution when applying antiaging products after washing because washing allows antiagers to penetrate deeper, leading to faster results in most skin types, but may also lead to increased irritation and then postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in darker skin.

Gentle cleansers are best, unless the skin is especially acne prone. In this case, anti-acne cleansers with ingredients like salicylic acid, benzoyl peroxide, or glycolic acid may be useful. To refresh skin, a splash of lukewarm water should do.

2. Apply products with a lower pH.

Studies have shown pH to be lower in darker skin, compared with lighter skin. For darker skin, products that are slightly acidic, such as those that contain mild glycolic acid, can help maintain the skin’s pH balance and maintain homeostasis and barrier integrity.

3. Be UV obsessed.

While the epidermis of darker skin contains more melanin content and has increased melanosomal dispersion than lighter skin—providing increased protection against UV-induced skin cancers and photoaging—UV damage can still occur.

Many patients with darker skin feel they are immune to skin cancer. Patients with darker skin, while diagnosed less frequently with melanoma, die at an increased frequency from the disease because of later diagnosis. Using a sunscreen that is SPF 30 or higher that blocks both UVA and UVB wavelengths is essential.

Patients should be reminded that nothing is more important than wearing sunscreen every day to promote younger-looking skin and prevent skin cancer.

Sunscreens, especially those with a higher SPF, often do not rub in well on darker skin. Using a sunscreen with chemical blockers, or micronized physical blockers (zinc and titanium dioxide), may go on less chalky and rub in more smoothly.

Sun exposure in darker skin also leads to prolonged postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after any skin insult. Even 10 minutes of daily exposure to UVA can cause changes that lead to wrinkles and sunspots in as few as 12 weeks.

Also, advise patients to eat foods that are rich in vitamin D to avoid deficiency.

4. Manage stress.

Emotional upheavals can make a patient’s skin look 5 years older than his or her chronological age. Constant anxiety increases the stress hormone cortisol, which causes inflammation that breaks down collagen. It also triggers a chain of responses that can lead to facial redness and acne flare-ups. To quell inflammation, advise patients to eat antioxidant-rich foods such as berries, oranges, and asparagus.

5. Use a retinoid.

Vitamin A derivatives, such as topical retinoids, speed cell turnover and collagen growth to smooth fine lines and wrinkles and fade brown spots. Prescription-strength retinoids provide the fastest results—your patient should start to see changes in about a month.

To help skin adjust to any redness or peeling, advise patients to apply a pea-size drop to the face every third night, building up to nightly use. Milder over-the-counter versions are gentler, although it can take up to 3 months for users to see noticeable results.

Redness and peeling should absolutely be avoided in darker skin to avoid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, so retinoids, while helpful, should be used cautiously.

6. Update your routine.

Advising patients to alter just one thing in their regimen every 6-12 months jump starts more impressive improvements in tone and texture. When products are applied consistently, skin slides into maintenance mode after about a year. To keep skin primed for rejuvenation, tell patients to substitute a cream that contains alpha hydroxy acids in place of a retinoid twice a week to boost benefits. Or, you can bump up the patient’s OTC retinoid to a prescription product.

7. Eat omega-3 fats.

These “good fats,” found in foods such as salmon, flaxseed, and almonds, boost hydration, which keeps skin supple and firm. The same is not true, however, of the saturated fat in dairy products and meats, which increase free-radical damage that makes skin more susceptible to aging. Advise patients to limit their intake of saturated fat to about 17 g per day.

8. Exercise regularly.

Studies find that women who work out regularly have firmer skin than non-exercisers. The reason: Exercise infuses skin with oxygen and nutrients needed for collagen production. Patients who aim to keep skin toned should make time for at least three, 30-minute, heart-pumping workouts per week.

9. Wash your hair.

Curly hair cannot be washed as often as straight hair because it dries out more readily. However, decreased hair washing leads to increased scalp sebum production, which can lead to increased breakouts.

If hair cannot be washed, patients should wrap their hair at night so it does not touch the face, and they should change their pillow cases frequently. In addition, many persons of African descent apply oils and pomades to their hair to keep it soft and manageable. Here, hair wrapping or increased washing is also essential to avoid “pomade acne.”

Alzheimer's Drug Pulled From Phase III for Lack of Efficacy

Another potential Alzheimer's disease drug failed after Eli Lilly and Co. pulled the plug Aug. 17 on its phase III study of semagacestat, a gamma secretase inhibitor designed to reduce the aggregation of beta-amyloid into brain plaques.

This latest in a long string of Alzheimer's drug flops carried an especially harsh sting, said Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, an investigator in the IDENTITY (Interrupting Alzheimer’s Dementia by Evaluating Treatment of Amyloid Pathology) and IDENTITY-2 trials.

"Unlike some of the previous failed phase III studies, IDENTITY was a well-designed, well-powered study of a drug with a very specific mechanism," he said in an interview. "IDENTITY had a lot going for it. This was a tough one to swallow."

The company announced its decision to halt semagacestat development after a planned interim analysis of both trials showed that patients who took the study drug did not experience cognitive improvement and, in fact, showed a significant worsening of cognition and the ability to perform activities of daily living, compared with those taking placebo.

In a press statement, the company also noted that semagacestat was associated with an increased risk of skin cancer. No data were available as to the risk ratio, crude incidence rate, or type of cancers observed.

"This is disappointing news for the millions of Alzheimer's patients and their families worldwide who anxiously await a successful treatment for this devastating illness," Jan M. Lundberg, Ph.D., president of Lilly Research Laboratories, said in a statement.

IDENTITY and IDENTITY-2 randomized more than 2,600 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease to either placebo or 140-mg semagacestat for 24 months. Although the trials have been halted, Lilly will continue to follow patients and analyze safety and efficacy data from both studies for at least another 6 months. The statement noted that the extended follow-up "will help to answer a number of important questions, including whether the differences between patients who received semagacestat and those who received placebo will continue after semagacestat has been discontinued."

Dr. Sabbagh, the clinical and research medical director of the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Ariz., said it is still too early to understand why those who took the study drug fared worse than the placebo group, or how it may have affected skin cancer risk. "I would be very cautious on interpreting these data until the full analysis has unfolded."

Semagacestat made a somewhat unusual leap from phase II to phase III research, Dr. Sabbagh said. "They had some very promising data going into phase III, but it was a very different approach. Their 14-week, phase II study [in 51 patients] met the safety end points, but did not look at [cognitive] efficacy." Instead, he said, Lilly moved the drug forward on the basis of significantly reduced beta-amyloid levels in blood plasma.

The drug does not decrease the existing Alzheimer's plaque burden. Instead, its aim is to prevent new plaques. It decreases the amount of plaque-forming beta-amyloid protein by changing the point at which gamma secretase cleaves the amyloid precursor protein. The resulting shorter peptide lengths do not aggregate into brain plaques like those with 40 and 42 amino acids—amyloid beta40 (Abeta40), and Abeta42.

In the phase II study, patients who took 100-mg semagacestat daily had a 58% reduction of Abeta40 in the plasma; those who took 140 mg daily had a 65% reduction. However, there were no significant reductions in CSF Abeta40 levels (Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1031-8).

Although the drug was generally well tolerated, the phase II researchers, led by Dr. Adam Fleischer of University of California, San Diego, expressed some concern about safety. All gamma secretase inhibitors interfere with Notch signaling. The Notch protein is important in programmed cell death; blocking it particularly affects organ systems with high cell turnover, such as the gut and immune system. In the phase II trial, there were more – but not significantly more – gastrointestinal side effects in the active group (27% vs. 13%). One small-bowel obstruction was considered possibly drug related.

"In addition, when combining reports of somnolence, fatigue, lethargy, and asthenia from different organ classes, we found that 40% of treatment subjects noted one or more of these symptoms, whereas only 13% in the placebo group had these symptoms (P = .18)," Dr. Fleischer and his colleagues reported.

Although the drug mobilized Abeta40 in phase II, the changes did not translate into clinical benefit during phase III, Dr. Sabbagh said. But that finding may mean that semagacestat’s failure is a case of poor timing rather than poor efficacy.

"By the time you have Alzheimer’s symptoms, you already have a critical mass of amyloid plaque, and this stays relatively constant as you progress through the disease," he said. "The question is, will any antiamyloid drug have a meaningful effect if it’s given after the plaques have already developed?"

It may be time, he said, to think of Alzheimer's as a biphasic disorder, with different drugs for each phase. Initially, amyloid plaques appear in the disease, followed by tau neurofibrillatory tangling and its associated neurotoxicity. "Maybe our amyloid-based therapies should be used in the presymptomatic phase, before the plaques build to that critical level. Other drugs might be more useful in the symptomatic stage."

Dr. Sabbagh said he wondered if some of the Alzheimer's drugs that have been abandoned after failing their phase III studies might be more successful if used earlier in the disease course. "My fear is that a drug will be shelved when in fact it might be a good choice in a presymptomatic scenario, when amyloid plaques are just beginning to develop."

With the enormous leaps now being made in amyloid imaging, researchers are pushing back the diagnostic timeline, identifying patients at the very onset of mild cognitive impairment – and perhaps even before any memory complaints appear. "A drug like semagacestat would be interesting to study in patients at that stage. Don’t chuck the product altogether; back it up into an earlier phase and see if the results are any different."

Lilly sponsored the studies. Dr. Sabbagh reported no financial ties with the company.

Another potential Alzheimer's disease drug failed after Eli Lilly and Co. pulled the plug Aug. 17 on its phase III study of semagacestat, a gamma secretase inhibitor designed to reduce the aggregation of beta-amyloid into brain plaques.

This latest in a long string of Alzheimer's drug flops carried an especially harsh sting, said Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, an investigator in the IDENTITY (Interrupting Alzheimer’s Dementia by Evaluating Treatment of Amyloid Pathology) and IDENTITY-2 trials.

"Unlike some of the previous failed phase III studies, IDENTITY was a well-designed, well-powered study of a drug with a very specific mechanism," he said in an interview. "IDENTITY had a lot going for it. This was a tough one to swallow."

The company announced its decision to halt semagacestat development after a planned interim analysis of both trials showed that patients who took the study drug did not experience cognitive improvement and, in fact, showed a significant worsening of cognition and the ability to perform activities of daily living, compared with those taking placebo.

In a press statement, the company also noted that semagacestat was associated with an increased risk of skin cancer. No data were available as to the risk ratio, crude incidence rate, or type of cancers observed.

"This is disappointing news for the millions of Alzheimer's patients and their families worldwide who anxiously await a successful treatment for this devastating illness," Jan M. Lundberg, Ph.D., president of Lilly Research Laboratories, said in a statement.

IDENTITY and IDENTITY-2 randomized more than 2,600 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease to either placebo or 140-mg semagacestat for 24 months. Although the trials have been halted, Lilly will continue to follow patients and analyze safety and efficacy data from both studies for at least another 6 months. The statement noted that the extended follow-up "will help to answer a number of important questions, including whether the differences between patients who received semagacestat and those who received placebo will continue after semagacestat has been discontinued."

Dr. Sabbagh, the clinical and research medical director of the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Ariz., said it is still too early to understand why those who took the study drug fared worse than the placebo group, or how it may have affected skin cancer risk. "I would be very cautious on interpreting these data until the full analysis has unfolded."

Semagacestat made a somewhat unusual leap from phase II to phase III research, Dr. Sabbagh said. "They had some very promising data going into phase III, but it was a very different approach. Their 14-week, phase II study [in 51 patients] met the safety end points, but did not look at [cognitive] efficacy." Instead, he said, Lilly moved the drug forward on the basis of significantly reduced beta-amyloid levels in blood plasma.

The drug does not decrease the existing Alzheimer's plaque burden. Instead, its aim is to prevent new plaques. It decreases the amount of plaque-forming beta-amyloid protein by changing the point at which gamma secretase cleaves the amyloid precursor protein. The resulting shorter peptide lengths do not aggregate into brain plaques like those with 40 and 42 amino acids—amyloid beta40 (Abeta40), and Abeta42.

In the phase II study, patients who took 100-mg semagacestat daily had a 58% reduction of Abeta40 in the plasma; those who took 140 mg daily had a 65% reduction. However, there were no significant reductions in CSF Abeta40 levels (Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1031-8).

Although the drug was generally well tolerated, the phase II researchers, led by Dr. Adam Fleischer of University of California, San Diego, expressed some concern about safety. All gamma secretase inhibitors interfere with Notch signaling. The Notch protein is important in programmed cell death; blocking it particularly affects organ systems with high cell turnover, such as the gut and immune system. In the phase II trial, there were more – but not significantly more – gastrointestinal side effects in the active group (27% vs. 13%). One small-bowel obstruction was considered possibly drug related.

"In addition, when combining reports of somnolence, fatigue, lethargy, and asthenia from different organ classes, we found that 40% of treatment subjects noted one or more of these symptoms, whereas only 13% in the placebo group had these symptoms (P = .18)," Dr. Fleischer and his colleagues reported.

Although the drug mobilized Abeta40 in phase II, the changes did not translate into clinical benefit during phase III, Dr. Sabbagh said. But that finding may mean that semagacestat’s failure is a case of poor timing rather than poor efficacy.

"By the time you have Alzheimer’s symptoms, you already have a critical mass of amyloid plaque, and this stays relatively constant as you progress through the disease," he said. "The question is, will any antiamyloid drug have a meaningful effect if it’s given after the plaques have already developed?"

It may be time, he said, to think of Alzheimer's as a biphasic disorder, with different drugs for each phase. Initially, amyloid plaques appear in the disease, followed by tau neurofibrillatory tangling and its associated neurotoxicity. "Maybe our amyloid-based therapies should be used in the presymptomatic phase, before the plaques build to that critical level. Other drugs might be more useful in the symptomatic stage."

Dr. Sabbagh said he wondered if some of the Alzheimer's drugs that have been abandoned after failing their phase III studies might be more successful if used earlier in the disease course. "My fear is that a drug will be shelved when in fact it might be a good choice in a presymptomatic scenario, when amyloid plaques are just beginning to develop."

With the enormous leaps now being made in amyloid imaging, researchers are pushing back the diagnostic timeline, identifying patients at the very onset of mild cognitive impairment – and perhaps even before any memory complaints appear. "A drug like semagacestat would be interesting to study in patients at that stage. Don’t chuck the product altogether; back it up into an earlier phase and see if the results are any different."

Lilly sponsored the studies. Dr. Sabbagh reported no financial ties with the company.

Another potential Alzheimer's disease drug failed after Eli Lilly and Co. pulled the plug Aug. 17 on its phase III study of semagacestat, a gamma secretase inhibitor designed to reduce the aggregation of beta-amyloid into brain plaques.

This latest in a long string of Alzheimer's drug flops carried an especially harsh sting, said Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, an investigator in the IDENTITY (Interrupting Alzheimer’s Dementia by Evaluating Treatment of Amyloid Pathology) and IDENTITY-2 trials.

"Unlike some of the previous failed phase III studies, IDENTITY was a well-designed, well-powered study of a drug with a very specific mechanism," he said in an interview. "IDENTITY had a lot going for it. This was a tough one to swallow."

The company announced its decision to halt semagacestat development after a planned interim analysis of both trials showed that patients who took the study drug did not experience cognitive improvement and, in fact, showed a significant worsening of cognition and the ability to perform activities of daily living, compared with those taking placebo.

In a press statement, the company also noted that semagacestat was associated with an increased risk of skin cancer. No data were available as to the risk ratio, crude incidence rate, or type of cancers observed.

"This is disappointing news for the millions of Alzheimer's patients and their families worldwide who anxiously await a successful treatment for this devastating illness," Jan M. Lundberg, Ph.D., president of Lilly Research Laboratories, said in a statement.

IDENTITY and IDENTITY-2 randomized more than 2,600 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease to either placebo or 140-mg semagacestat for 24 months. Although the trials have been halted, Lilly will continue to follow patients and analyze safety and efficacy data from both studies for at least another 6 months. The statement noted that the extended follow-up "will help to answer a number of important questions, including whether the differences between patients who received semagacestat and those who received placebo will continue after semagacestat has been discontinued."

Dr. Sabbagh, the clinical and research medical director of the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Ariz., said it is still too early to understand why those who took the study drug fared worse than the placebo group, or how it may have affected skin cancer risk. "I would be very cautious on interpreting these data until the full analysis has unfolded."

Semagacestat made a somewhat unusual leap from phase II to phase III research, Dr. Sabbagh said. "They had some very promising data going into phase III, but it was a very different approach. Their 14-week, phase II study [in 51 patients] met the safety end points, but did not look at [cognitive] efficacy." Instead, he said, Lilly moved the drug forward on the basis of significantly reduced beta-amyloid levels in blood plasma.

The drug does not decrease the existing Alzheimer's plaque burden. Instead, its aim is to prevent new plaques. It decreases the amount of plaque-forming beta-amyloid protein by changing the point at which gamma secretase cleaves the amyloid precursor protein. The resulting shorter peptide lengths do not aggregate into brain plaques like those with 40 and 42 amino acids—amyloid beta40 (Abeta40), and Abeta42.

In the phase II study, patients who took 100-mg semagacestat daily had a 58% reduction of Abeta40 in the plasma; those who took 140 mg daily had a 65% reduction. However, there were no significant reductions in CSF Abeta40 levels (Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1031-8).

Although the drug was generally well tolerated, the phase II researchers, led by Dr. Adam Fleischer of University of California, San Diego, expressed some concern about safety. All gamma secretase inhibitors interfere with Notch signaling. The Notch protein is important in programmed cell death; blocking it particularly affects organ systems with high cell turnover, such as the gut and immune system. In the phase II trial, there were more – but not significantly more – gastrointestinal side effects in the active group (27% vs. 13%). One small-bowel obstruction was considered possibly drug related.

"In addition, when combining reports of somnolence, fatigue, lethargy, and asthenia from different organ classes, we found that 40% of treatment subjects noted one or more of these symptoms, whereas only 13% in the placebo group had these symptoms (P = .18)," Dr. Fleischer and his colleagues reported.

Although the drug mobilized Abeta40 in phase II, the changes did not translate into clinical benefit during phase III, Dr. Sabbagh said. But that finding may mean that semagacestat’s failure is a case of poor timing rather than poor efficacy.

"By the time you have Alzheimer’s symptoms, you already have a critical mass of amyloid plaque, and this stays relatively constant as you progress through the disease," he said. "The question is, will any antiamyloid drug have a meaningful effect if it’s given after the plaques have already developed?"

It may be time, he said, to think of Alzheimer's as a biphasic disorder, with different drugs for each phase. Initially, amyloid plaques appear in the disease, followed by tau neurofibrillatory tangling and its associated neurotoxicity. "Maybe our amyloid-based therapies should be used in the presymptomatic phase, before the plaques build to that critical level. Other drugs might be more useful in the symptomatic stage."

Dr. Sabbagh said he wondered if some of the Alzheimer's drugs that have been abandoned after failing their phase III studies might be more successful if used earlier in the disease course. "My fear is that a drug will be shelved when in fact it might be a good choice in a presymptomatic scenario, when amyloid plaques are just beginning to develop."

With the enormous leaps now being made in amyloid imaging, researchers are pushing back the diagnostic timeline, identifying patients at the very onset of mild cognitive impairment – and perhaps even before any memory complaints appear. "A drug like semagacestat would be interesting to study in patients at that stage. Don’t chuck the product altogether; back it up into an earlier phase and see if the results are any different."

Lilly sponsored the studies. Dr. Sabbagh reported no financial ties with the company.

Could Chemoprevention Agents Be the Next Sunscreen?

CHICAGO - In the not-too distant future, dermatologists may be sending patients off to the beach with a bagful of chemoprevention tricks to outwit ultraviolet radiation and reduce the risk of sun-related skin cancers.

"In addition to sunscreen, we'll be using these chemopreventive agents not only to reduce histologic response to ultraviolet light, but to repair the DNA damage that occurs as a result of overexposure to the sun," said Dr. Craig Elmets at the American Academy of Dermatology's 2010 meeting. "Instead of sending patients to the beach covered up with long pants, long sleeves, and a hat, we can send them off to engage in their normal behavior with less worry about the long-term consequences."

Although sunscreens remain the first line of defense against cancer-inducing ultraviolet radiation, they need backup, said Dr. Elmets, professor and chair of the department of dermatology and director of the Skin Disease Research Center at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Theoretically, sunscreens work well, but in reality, their efficacy is less than ideal. "They are greasy and messy, and people don't really enjoy applying them. And most people don't use nearly enough to achieve the sun protection factor stated on the label; in fact, studies show that most people only use about 25% of the necessary amount."

Sunscreens also have limited effect, he said. "Over a 5-year period, sunscreens will reduce squamous cell carcinomas by about 35%, but they have very little effect on basal cell carcinoma."

A number of agents are being investigated for the chemoprevention of skin cancers. Some are oral, some are topical, and all have shown promising results in both animal and human studies.

Dimericine is a form of the bacterial enzyme T4 endonuclease. When encapsulated in a liposome and applied topically, the compound appears to boost the body’s DNA repair response by increasing base excision repair, Dr. Elmets said.

A 2001 study allocated 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum to either Dimericine or placebo for 1 year, in addition to sunscreen. Patients in the active group had a 68% reduction in actinic keratoses and a 30% reduction in basal cell carcinoma (Lancet 2001;24;926-9).

Dr. Elmets is the lead investigator in one of two ongoing dimericine trials. The first is a phase II study randomizing kidney transplant patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer to either the drug or placebo for 12 months, with an outcome of new nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The second study is a phase III study aiming to recruit up to 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum who will be allocated to dimericine or placebo, with the primary end point of new actinic keratoses.

"Another exciting molecule that may have good chemopreventive potential is GDC-0449," Dr. Elmets said. The compound is a systemic hedgehog pathway antagonist. "The hedgehog pathway is an important regulator of cell growth and differentiation during embryogenesis. But mutations are associated with basal cell carcinomas in both children and adults," he said. Animal research has shown that inhibiting this pathway can reduce tumor growth.

A 2009 study involved 33 patients with metastatic or locally advanced basal cell carcinoma who took the drug at different doses. Eighteen achieved a response; 2 were complete and 16 were partial. Disease stabilized in 15 patients and progressed in 4 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1164-72).

Twenty-four trials are either in progress or recruiting, studying GDC-0449’s safety and efficacy in a variety of cancers, including basal cell nevus syndrome, and pancreatic, gastrointestinal, lung, breast, and brain cancers.

DMFO (alpha-difluoromethylornithine, also known as eflornithine) irreversibly inhibits ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme unregulated in many tumors. Dr. Elmets described a recent phase III trial of 219 patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. After 4-5 years of follow-up (more than 1,200 person/years), there was no significant difference in the total numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancers between the active and placebo group. But new basal cell carcinomas were 33% less common in the active group than the placebo group (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:35-47).

There are 20 active or completed trials looking at this agent in relation to several cancers, including bladder, GI, neuroblastoma, and trypanosomosis.

The cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor celecoxib is even in the skin cancer race. "COX-2 is dramatically upregulated in actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas, and also in the interstitial space around basal carcinoma tumor islands," Dr. Elmets said. "When given orally, it inhibits COX-2 expression, reducing the prostaglandin E2 production implicated in skin cancers."

A recent study of 60 patients with basal cell nevus syndrome treated with celecoxib found that those with less severe disease had a 20% increase in the number of basal cell carcinomas over 24 months, compared with a 50% increase in those taking placebo (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:25-34). Celecoxib is also being investigated for use in GI, prostate, and lung cancers.

Finally, Dr. Elmets said, an ancient – and familiar – drink holds intriguing possibilities. The primary catechin in green tea, EGCG, (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) is a potent antioxidant that appears to reduce histologic and clinical damage from exposure to ultraviolet lights A and B. "When ECGC is applied topically or given to animals to drink in their water, they show a dramatic reduction in new skin cancers. In humans, it reduces UVA and UVB erythema," Dr. Elmets said.

Because of its broad antioxidant properties, EGCG is the subject of numerous clinical trials examining its potential in other cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, muscular dystrophy, photoaging, and weight loss.

Disclosures: Dr. Elmets has received research support from Pfizer Inc. and holds an intellectual property right on the use of EGCG as a skin cancer chemopreventive agent.

CHICAGO - In the not-too distant future, dermatologists may be sending patients off to the beach with a bagful of chemoprevention tricks to outwit ultraviolet radiation and reduce the risk of sun-related skin cancers.

"In addition to sunscreen, we'll be using these chemopreventive agents not only to reduce histologic response to ultraviolet light, but to repair the DNA damage that occurs as a result of overexposure to the sun," said Dr. Craig Elmets at the American Academy of Dermatology's 2010 meeting. "Instead of sending patients to the beach covered up with long pants, long sleeves, and a hat, we can send them off to engage in their normal behavior with less worry about the long-term consequences."

Although sunscreens remain the first line of defense against cancer-inducing ultraviolet radiation, they need backup, said Dr. Elmets, professor and chair of the department of dermatology and director of the Skin Disease Research Center at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Theoretically, sunscreens work well, but in reality, their efficacy is less than ideal. "They are greasy and messy, and people don't really enjoy applying them. And most people don't use nearly enough to achieve the sun protection factor stated on the label; in fact, studies show that most people only use about 25% of the necessary amount."

Sunscreens also have limited effect, he said. "Over a 5-year period, sunscreens will reduce squamous cell carcinomas by about 35%, but they have very little effect on basal cell carcinoma."

A number of agents are being investigated for the chemoprevention of skin cancers. Some are oral, some are topical, and all have shown promising results in both animal and human studies.

Dimericine is a form of the bacterial enzyme T4 endonuclease. When encapsulated in a liposome and applied topically, the compound appears to boost the body’s DNA repair response by increasing base excision repair, Dr. Elmets said.

A 2001 study allocated 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum to either Dimericine or placebo for 1 year, in addition to sunscreen. Patients in the active group had a 68% reduction in actinic keratoses and a 30% reduction in basal cell carcinoma (Lancet 2001;24;926-9).

Dr. Elmets is the lead investigator in one of two ongoing dimericine trials. The first is a phase II study randomizing kidney transplant patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer to either the drug or placebo for 12 months, with an outcome of new nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The second study is a phase III study aiming to recruit up to 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum who will be allocated to dimericine or placebo, with the primary end point of new actinic keratoses.

"Another exciting molecule that may have good chemopreventive potential is GDC-0449," Dr. Elmets said. The compound is a systemic hedgehog pathway antagonist. "The hedgehog pathway is an important regulator of cell growth and differentiation during embryogenesis. But mutations are associated with basal cell carcinomas in both children and adults," he said. Animal research has shown that inhibiting this pathway can reduce tumor growth.

A 2009 study involved 33 patients with metastatic or locally advanced basal cell carcinoma who took the drug at different doses. Eighteen achieved a response; 2 were complete and 16 were partial. Disease stabilized in 15 patients and progressed in 4 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1164-72).

Twenty-four trials are either in progress or recruiting, studying GDC-0449’s safety and efficacy in a variety of cancers, including basal cell nevus syndrome, and pancreatic, gastrointestinal, lung, breast, and brain cancers.

DMFO (alpha-difluoromethylornithine, also known as eflornithine) irreversibly inhibits ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme unregulated in many tumors. Dr. Elmets described a recent phase III trial of 219 patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. After 4-5 years of follow-up (more than 1,200 person/years), there was no significant difference in the total numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancers between the active and placebo group. But new basal cell carcinomas were 33% less common in the active group than the placebo group (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:35-47).

There are 20 active or completed trials looking at this agent in relation to several cancers, including bladder, GI, neuroblastoma, and trypanosomosis.

The cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor celecoxib is even in the skin cancer race. "COX-2 is dramatically upregulated in actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas, and also in the interstitial space around basal carcinoma tumor islands," Dr. Elmets said. "When given orally, it inhibits COX-2 expression, reducing the prostaglandin E2 production implicated in skin cancers."

A recent study of 60 patients with basal cell nevus syndrome treated with celecoxib found that those with less severe disease had a 20% increase in the number of basal cell carcinomas over 24 months, compared with a 50% increase in those taking placebo (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:25-34). Celecoxib is also being investigated for use in GI, prostate, and lung cancers.

Finally, Dr. Elmets said, an ancient – and familiar – drink holds intriguing possibilities. The primary catechin in green tea, EGCG, (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) is a potent antioxidant that appears to reduce histologic and clinical damage from exposure to ultraviolet lights A and B. "When ECGC is applied topically or given to animals to drink in their water, they show a dramatic reduction in new skin cancers. In humans, it reduces UVA and UVB erythema," Dr. Elmets said.

Because of its broad antioxidant properties, EGCG is the subject of numerous clinical trials examining its potential in other cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, muscular dystrophy, photoaging, and weight loss.

Disclosures: Dr. Elmets has received research support from Pfizer Inc. and holds an intellectual property right on the use of EGCG as a skin cancer chemopreventive agent.

CHICAGO - In the not-too distant future, dermatologists may be sending patients off to the beach with a bagful of chemoprevention tricks to outwit ultraviolet radiation and reduce the risk of sun-related skin cancers.

"In addition to sunscreen, we'll be using these chemopreventive agents not only to reduce histologic response to ultraviolet light, but to repair the DNA damage that occurs as a result of overexposure to the sun," said Dr. Craig Elmets at the American Academy of Dermatology's 2010 meeting. "Instead of sending patients to the beach covered up with long pants, long sleeves, and a hat, we can send them off to engage in their normal behavior with less worry about the long-term consequences."

Although sunscreens remain the first line of defense against cancer-inducing ultraviolet radiation, they need backup, said Dr. Elmets, professor and chair of the department of dermatology and director of the Skin Disease Research Center at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Theoretically, sunscreens work well, but in reality, their efficacy is less than ideal. "They are greasy and messy, and people don't really enjoy applying them. And most people don't use nearly enough to achieve the sun protection factor stated on the label; in fact, studies show that most people only use about 25% of the necessary amount."

Sunscreens also have limited effect, he said. "Over a 5-year period, sunscreens will reduce squamous cell carcinomas by about 35%, but they have very little effect on basal cell carcinoma."

A number of agents are being investigated for the chemoprevention of skin cancers. Some are oral, some are topical, and all have shown promising results in both animal and human studies.

Dimericine is a form of the bacterial enzyme T4 endonuclease. When encapsulated in a liposome and applied topically, the compound appears to boost the body’s DNA repair response by increasing base excision repair, Dr. Elmets said.

A 2001 study allocated 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum to either Dimericine or placebo for 1 year, in addition to sunscreen. Patients in the active group had a 68% reduction in actinic keratoses and a 30% reduction in basal cell carcinoma (Lancet 2001;24;926-9).

Dr. Elmets is the lead investigator in one of two ongoing dimericine trials. The first is a phase II study randomizing kidney transplant patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer to either the drug or placebo for 12 months, with an outcome of new nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The second study is a phase III study aiming to recruit up to 30 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum who will be allocated to dimericine or placebo, with the primary end point of new actinic keratoses.

"Another exciting molecule that may have good chemopreventive potential is GDC-0449," Dr. Elmets said. The compound is a systemic hedgehog pathway antagonist. "The hedgehog pathway is an important regulator of cell growth and differentiation during embryogenesis. But mutations are associated with basal cell carcinomas in both children and adults," he said. Animal research has shown that inhibiting this pathway can reduce tumor growth.

A 2009 study involved 33 patients with metastatic or locally advanced basal cell carcinoma who took the drug at different doses. Eighteen achieved a response; 2 were complete and 16 were partial. Disease stabilized in 15 patients and progressed in 4 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1164-72).

Twenty-four trials are either in progress or recruiting, studying GDC-0449’s safety and efficacy in a variety of cancers, including basal cell nevus syndrome, and pancreatic, gastrointestinal, lung, breast, and brain cancers.

DMFO (alpha-difluoromethylornithine, also known as eflornithine) irreversibly inhibits ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme unregulated in many tumors. Dr. Elmets described a recent phase III trial of 219 patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. After 4-5 years of follow-up (more than 1,200 person/years), there was no significant difference in the total numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancers between the active and placebo group. But new basal cell carcinomas were 33% less common in the active group than the placebo group (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:35-47).

There are 20 active or completed trials looking at this agent in relation to several cancers, including bladder, GI, neuroblastoma, and trypanosomosis.

The cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor celecoxib is even in the skin cancer race. "COX-2 is dramatically upregulated in actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas, and also in the interstitial space around basal carcinoma tumor islands," Dr. Elmets said. "When given orally, it inhibits COX-2 expression, reducing the prostaglandin E2 production implicated in skin cancers."

A recent study of 60 patients with basal cell nevus syndrome treated with celecoxib found that those with less severe disease had a 20% increase in the number of basal cell carcinomas over 24 months, compared with a 50% increase in those taking placebo (Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:25-34). Celecoxib is also being investigated for use in GI, prostate, and lung cancers.

Finally, Dr. Elmets said, an ancient – and familiar – drink holds intriguing possibilities. The primary catechin in green tea, EGCG, (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) is a potent antioxidant that appears to reduce histologic and clinical damage from exposure to ultraviolet lights A and B. "When ECGC is applied topically or given to animals to drink in their water, they show a dramatic reduction in new skin cancers. In humans, it reduces UVA and UVB erythema," Dr. Elmets said.

Because of its broad antioxidant properties, EGCG is the subject of numerous clinical trials examining its potential in other cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, muscular dystrophy, photoaging, and weight loss.

Disclosures: Dr. Elmets has received research support from Pfizer Inc. and holds an intellectual property right on the use of EGCG as a skin cancer chemopreventive agent.

Deadly Doppelganger for Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Monterey, Calif. - If there is a doppelganger in dermatology, malignant fibrous histiocytoma is it, according to Dr. Henry W. Randle at a meeting of the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

By immunohistochemistry, MFH is a dead ringer for atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). Compared with rare mortality from AFX, however, approximately 38% of patients with MFH die within 3.5 years, said Dr. Randle.

Histologically, we can’t tell them apart. They look the same, but they behave very differently,” and require different treatment approaches, said Dr. Randle of the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

The two main treatments for AFX are excision with a 1- to 2-cm margin that includes subcutaneous tissue or Mohs surgery.

For MFH, treatment involves tumor staging and wide excision to several centimeters, with consideration of node dissection, radiation, and chemotherapy. Mohs surgery is not the best option. “You’re brave if you do that” for MFH, he said. “This is a different animal.”

The problem lies in telling the two apart. Even the histologic diagnosis of AFX can be challenging, because no specific marker or test exists to identify AFX. Diagnosis requires excluding spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas, melanomas of the spindle cells, and other spindle cell malignancies.

The only identifiable characteristics that separate the relatively innocuous AFX from the more lethal MFH are the more superficial location of AFX and the fact that AFX typically appears on the head and neck, whereas MFH more typically occurs on the extremities and trunk, but not on the face.