User login

ISCHEMIA-CKD: No benefit for coronary revascularization in advanced CKD with stable angina

PHILADELPHIA – Coronary revascularization in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) and stable ischemic heart disease accomplishes nothing constructive, according to clear-cut results of the landmark ISCHEMIA-CKD trial.

In this multinational randomized trial including 777 stable patients with advanced CKD and moderate or severe myocardial ischemia on noninvasive testing, an early invasive strategy didn’t reduce the risks of death or ischemic events, didn’t provide any significant improvement in quality of life metrics, and resulted in an increased risk of stroke, Sripal Bangalore, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“ said Dr. Bangalore, professor of medicine and director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

This was easily the largest-ever trial of an invasive versus conservative coronary artery disease management strategy in this challenging population. For example, in the COURAGE trial of optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary disease (N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356[15]:1503-16), only 16 of the 2,287 participants had an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

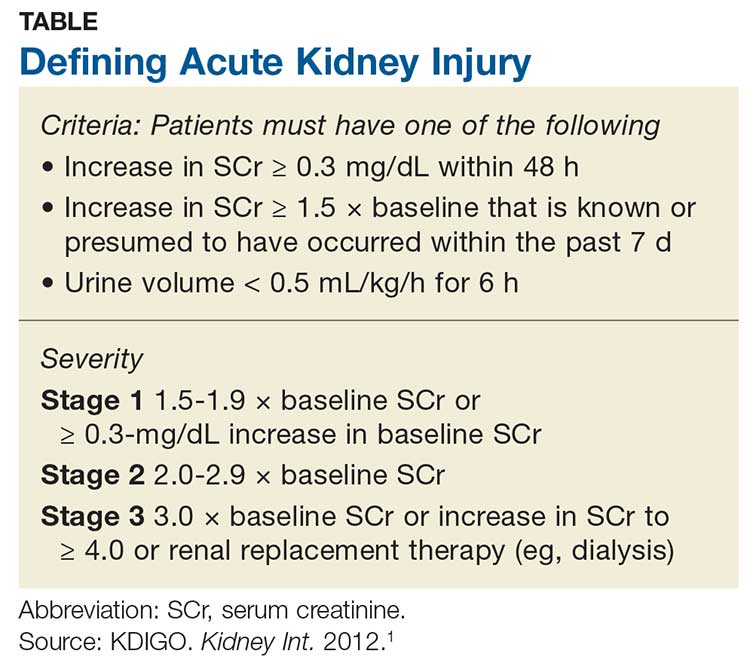

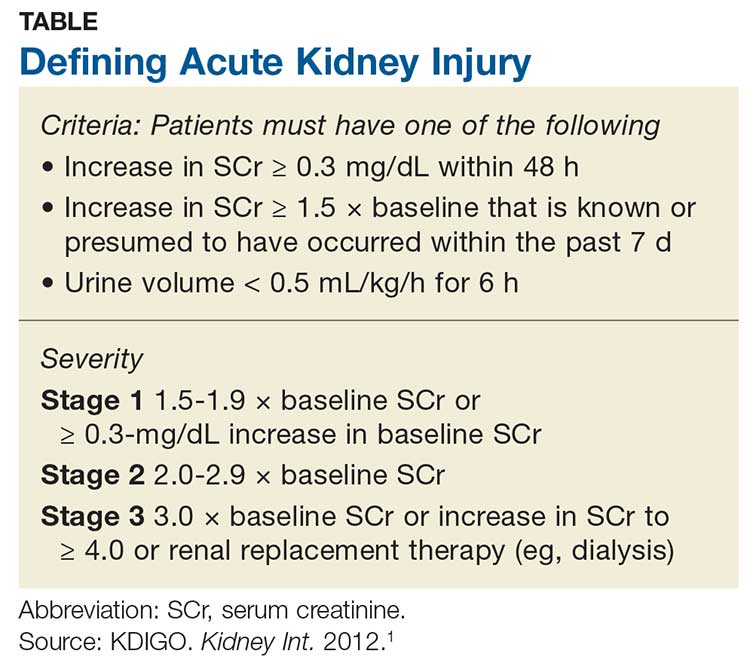

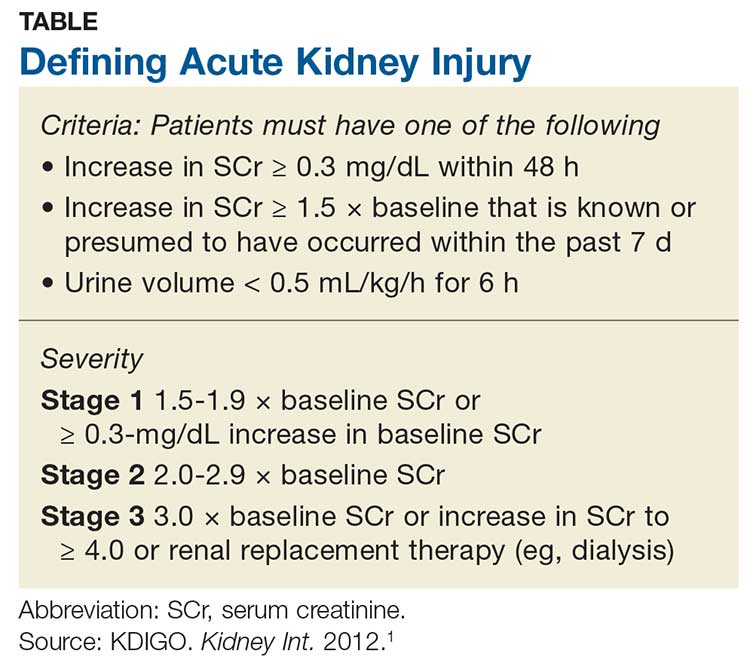

Of note, the participating study sites received special training aimed at minimizing the risk of acute kidney injury after cardiac catheterization in this at-risk population. The training included utilization of a customized left ventricular end diastolic volume–based hydration protocol, guidance on how to perform percutaneous coronary intervention with little or no contrast material, and encouragement of a heart/kidney team approach involving a cardiologist, nephrologist, and cardiovascular surgeon. This training really paid off, with roughly a 7% incidence of acute kidney injury after catheterization.

“The expected rate in such patients would be 30%-60%,” according to Dr. Bangalore.

The primary endpoint in ISCHEMIA-CKD was the rates of death or MI during 3 years of prospective follow-up. This occurred in 36.7% of patients randomized to optimal medical therapy alone and 36.4% of those randomized to an early invasive strategy. Similarly, the major secondary endpoint, comprising death, MI, and hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest, was also a virtual dead heat, occurring in about 39% of subjects. More than 27% of study participants had died by the 3-year mark regardless of how their coronary disease was managed.

The adjusted risk of stroke was 3.76-fold higher in the invasive strategy group; however, the most strokes were not procedurally related, and the explanation for the significantly increased risk in the invasively managed group remains unknown, the cardiologist said.

John A. Spertus, MD, who led the quality of life assessment in ISCHEMIA-CKD and in the 5,129-patient parent ISCHEMIA (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches), also presented at the AHA scientific sessions. He reported that, unlike in the parent study, there was no hint of a meaningful long-term quality of life benefit for revascularization plus optimal medical therapy, compared with that of optimal medical therapy alone, in ISCHEMIA-CKD.

“We have greater than 93% confidence that there is more of a quality of life effect in patients without advanced CKD than in patients with advanced CKD,” said Dr. Spertus, director of health outcomes research at the Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Discussant Glenn L. Levine, MD, hailed ISCHEMIA-CKD as “a monumental achievement,” an ambitious, well-powered study with essentially no loss of follow-up during up to 4 years. It helps fill an utter void in the AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines, which to date offer no recommendations at all regarding revascularization in patients with CKD because of a lack of evidence. And he considers ISCHEMIA-CKD to be unequivocally practice changing and guideline changing.

“Based on the results of ISCHEMIA-CKD, I will generally not go searching for ischemia and [coronary artery disease] in most severe and end-stage CKD patients, absent marked or unacceptable angina, and will treat them with medical therapy alone,” declared Dr. Levine, professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the cardiac care unit at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, both in Houston.

He offered a few caveats. Excluded from participation in ISCHEMIA-CKD were patients with acute coronary syndrome, significant heart failure, or unacceptable angina despite optimal medical therapy at baseline, so the study results don’t apply to them. Also, the acute kidney injury rate after intervention was eye-catchingly low.

Dr. Bangalore discussed the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial and outcomes in a video interview with Medscape’s Tricia Ward.

“It seems unlikely that all centers routinely do and will exactly follow the very careful measures to limit contrast and minimize contrast nephropathy used in this study,” Dr. Levine commented.

ISCHEMIA-CKD, like its parent ISCHEMIA trial, was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Bangalore reported having no relevant financial interests. Dr. Spertus holds the copyright for the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, which was used for quality of life measurement in the trials. Dr. Levine disclosed that he has no relations with industry or conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Coronary revascularization in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) and stable ischemic heart disease accomplishes nothing constructive, according to clear-cut results of the landmark ISCHEMIA-CKD trial.

In this multinational randomized trial including 777 stable patients with advanced CKD and moderate or severe myocardial ischemia on noninvasive testing, an early invasive strategy didn’t reduce the risks of death or ischemic events, didn’t provide any significant improvement in quality of life metrics, and resulted in an increased risk of stroke, Sripal Bangalore, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“ said Dr. Bangalore, professor of medicine and director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

This was easily the largest-ever trial of an invasive versus conservative coronary artery disease management strategy in this challenging population. For example, in the COURAGE trial of optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary disease (N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356[15]:1503-16), only 16 of the 2,287 participants had an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Of note, the participating study sites received special training aimed at minimizing the risk of acute kidney injury after cardiac catheterization in this at-risk population. The training included utilization of a customized left ventricular end diastolic volume–based hydration protocol, guidance on how to perform percutaneous coronary intervention with little or no contrast material, and encouragement of a heart/kidney team approach involving a cardiologist, nephrologist, and cardiovascular surgeon. This training really paid off, with roughly a 7% incidence of acute kidney injury after catheterization.

“The expected rate in such patients would be 30%-60%,” according to Dr. Bangalore.

The primary endpoint in ISCHEMIA-CKD was the rates of death or MI during 3 years of prospective follow-up. This occurred in 36.7% of patients randomized to optimal medical therapy alone and 36.4% of those randomized to an early invasive strategy. Similarly, the major secondary endpoint, comprising death, MI, and hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest, was also a virtual dead heat, occurring in about 39% of subjects. More than 27% of study participants had died by the 3-year mark regardless of how their coronary disease was managed.

The adjusted risk of stroke was 3.76-fold higher in the invasive strategy group; however, the most strokes were not procedurally related, and the explanation for the significantly increased risk in the invasively managed group remains unknown, the cardiologist said.

John A. Spertus, MD, who led the quality of life assessment in ISCHEMIA-CKD and in the 5,129-patient parent ISCHEMIA (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches), also presented at the AHA scientific sessions. He reported that, unlike in the parent study, there was no hint of a meaningful long-term quality of life benefit for revascularization plus optimal medical therapy, compared with that of optimal medical therapy alone, in ISCHEMIA-CKD.

“We have greater than 93% confidence that there is more of a quality of life effect in patients without advanced CKD than in patients with advanced CKD,” said Dr. Spertus, director of health outcomes research at the Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Discussant Glenn L. Levine, MD, hailed ISCHEMIA-CKD as “a monumental achievement,” an ambitious, well-powered study with essentially no loss of follow-up during up to 4 years. It helps fill an utter void in the AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines, which to date offer no recommendations at all regarding revascularization in patients with CKD because of a lack of evidence. And he considers ISCHEMIA-CKD to be unequivocally practice changing and guideline changing.

“Based on the results of ISCHEMIA-CKD, I will generally not go searching for ischemia and [coronary artery disease] in most severe and end-stage CKD patients, absent marked or unacceptable angina, and will treat them with medical therapy alone,” declared Dr. Levine, professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the cardiac care unit at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, both in Houston.

He offered a few caveats. Excluded from participation in ISCHEMIA-CKD were patients with acute coronary syndrome, significant heart failure, or unacceptable angina despite optimal medical therapy at baseline, so the study results don’t apply to them. Also, the acute kidney injury rate after intervention was eye-catchingly low.

Dr. Bangalore discussed the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial and outcomes in a video interview with Medscape’s Tricia Ward.

“It seems unlikely that all centers routinely do and will exactly follow the very careful measures to limit contrast and minimize contrast nephropathy used in this study,” Dr. Levine commented.

ISCHEMIA-CKD, like its parent ISCHEMIA trial, was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Bangalore reported having no relevant financial interests. Dr. Spertus holds the copyright for the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, which was used for quality of life measurement in the trials. Dr. Levine disclosed that he has no relations with industry or conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Coronary revascularization in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) and stable ischemic heart disease accomplishes nothing constructive, according to clear-cut results of the landmark ISCHEMIA-CKD trial.

In this multinational randomized trial including 777 stable patients with advanced CKD and moderate or severe myocardial ischemia on noninvasive testing, an early invasive strategy didn’t reduce the risks of death or ischemic events, didn’t provide any significant improvement in quality of life metrics, and resulted in an increased risk of stroke, Sripal Bangalore, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“ said Dr. Bangalore, professor of medicine and director of complex coronary intervention at New York University.

This was easily the largest-ever trial of an invasive versus conservative coronary artery disease management strategy in this challenging population. For example, in the COURAGE trial of optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary disease (N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356[15]:1503-16), only 16 of the 2,287 participants had an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Of note, the participating study sites received special training aimed at minimizing the risk of acute kidney injury after cardiac catheterization in this at-risk population. The training included utilization of a customized left ventricular end diastolic volume–based hydration protocol, guidance on how to perform percutaneous coronary intervention with little or no contrast material, and encouragement of a heart/kidney team approach involving a cardiologist, nephrologist, and cardiovascular surgeon. This training really paid off, with roughly a 7% incidence of acute kidney injury after catheterization.

“The expected rate in such patients would be 30%-60%,” according to Dr. Bangalore.

The primary endpoint in ISCHEMIA-CKD was the rates of death or MI during 3 years of prospective follow-up. This occurred in 36.7% of patients randomized to optimal medical therapy alone and 36.4% of those randomized to an early invasive strategy. Similarly, the major secondary endpoint, comprising death, MI, and hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest, was also a virtual dead heat, occurring in about 39% of subjects. More than 27% of study participants had died by the 3-year mark regardless of how their coronary disease was managed.

The adjusted risk of stroke was 3.76-fold higher in the invasive strategy group; however, the most strokes were not procedurally related, and the explanation for the significantly increased risk in the invasively managed group remains unknown, the cardiologist said.

John A. Spertus, MD, who led the quality of life assessment in ISCHEMIA-CKD and in the 5,129-patient parent ISCHEMIA (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches), also presented at the AHA scientific sessions. He reported that, unlike in the parent study, there was no hint of a meaningful long-term quality of life benefit for revascularization plus optimal medical therapy, compared with that of optimal medical therapy alone, in ISCHEMIA-CKD.

“We have greater than 93% confidence that there is more of a quality of life effect in patients without advanced CKD than in patients with advanced CKD,” said Dr. Spertus, director of health outcomes research at the Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Discussant Glenn L. Levine, MD, hailed ISCHEMIA-CKD as “a monumental achievement,” an ambitious, well-powered study with essentially no loss of follow-up during up to 4 years. It helps fill an utter void in the AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines, which to date offer no recommendations at all regarding revascularization in patients with CKD because of a lack of evidence. And he considers ISCHEMIA-CKD to be unequivocally practice changing and guideline changing.

“Based on the results of ISCHEMIA-CKD, I will generally not go searching for ischemia and [coronary artery disease] in most severe and end-stage CKD patients, absent marked or unacceptable angina, and will treat them with medical therapy alone,” declared Dr. Levine, professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the cardiac care unit at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, both in Houston.

He offered a few caveats. Excluded from participation in ISCHEMIA-CKD were patients with acute coronary syndrome, significant heart failure, or unacceptable angina despite optimal medical therapy at baseline, so the study results don’t apply to them. Also, the acute kidney injury rate after intervention was eye-catchingly low.

Dr. Bangalore discussed the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial and outcomes in a video interview with Medscape’s Tricia Ward.

“It seems unlikely that all centers routinely do and will exactly follow the very careful measures to limit contrast and minimize contrast nephropathy used in this study,” Dr. Levine commented.

ISCHEMIA-CKD, like its parent ISCHEMIA trial, was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Bangalore reported having no relevant financial interests. Dr. Spertus holds the copyright for the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, which was used for quality of life measurement in the trials. Dr. Levine disclosed that he has no relations with industry or conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Novel antibody looks promising in lupus nephritis

WASHINGTON – A novel antibody, obinutuzumab, enhances renal responses in patients with lupus nephritis, through more complete B-cell depletion, compared with standard immunotherapy, and is well tolerated, according to results from the phase 2 NOBILITY trial.

“We know from our previous trials with anti–B-cell antibodies that results were mixed and we felt that these variable results were possibly due to variability in B-cell depletion with a type 1 anti-CD20 antibody such as rituximab,” Brad Rovin, MD, director, division of nephrology, Ohio State University in Columbus, told a press briefing here at Kidney Week 2019: American Society of Nephrology annual meeting.

“So we hypothesized that if we could deplete B cells more efficiently and completely, we would achieve better results. At week 52, 35% of patients in the obinutuzumab-treated group achieved a complete renal response, compared to 23% in the standard-of-care arm.”

And by week 76, the difference between obinutuzumab and the standard of care was actually larger at 40% vs. 18%, respectively, “and this was statistically significant at a P value of .01,” added Dr. Rovin, who presented the full findings of the study at the conference.

Obinutuzumab, a highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody, is already approved under the brand name Gazyva for use in certain leukemias and lymphomas. The NOBILITY study was funded by Genentech-Roche, and Dr. Rovin reported being a consultant for the company.

Asked by Medscape Medical News to comment on the study, Duvuru Geetha, MBBS, noted that with standard-of-care mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus corticosteroids, “the remissions rates we achieve [for lupus nephritis] are still not great,” ranging from 30% to 50%, depending on the patient population.

“This is why there is a need for alternative agents,” added Dr. Geetha, who is an associate professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

With obinutuzumab, “the data look very promising because there is a much more profound and sustained effect on B-cell depletion and the renal response rate is much higher [than with MMF and corticosteroids],” she noted.

Dr. Geetha added, however, that she presumes patients were all premedicated with prophylactic agents to prevent infectious events, as they are when treated with rituximab.

“I think what is definitely different about this drug is that it induces direct cell death more efficiently than rituximab and that is probably what’s accounting for the higher efficacy seen with it,” said Dr. Geetha, who disclosed having received honoraria from Genentech a number of years ago.

“So yes, I believe the results are clinically meaningful,” she concluded.

NOBILITY study design

The NOBILITY trial randomized 125 patients with Class III or IV lupus nephritis to either obinutuzumab plus MMF and corticosteroids, or to MMF plus corticosteroids alone, for a treatment interval of 104 weeks.

Patients in the obinutuzumab group received two infusions of the highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody at week 0 and week 2 and another two infusions at 6 months.

“The primary endpoint was complete renal response at week 52,” the authors wrote, “while key secondary endpoints included overall renal response and modified complete renal response.”

Both at week 52 and week 76, more patients in the obinutuzumab group achieved an overall renal response as well as a modified complete renal response, compared with those treated with immunosuppression alone.

“If you look at the complete renal response over time, you can see that the curves separate after about 6 months but the placebo group starts to decline as you go further out, whereas the obinutuzumab group continues to separate, so my prediction is that we are going to see this trend continue because of the mechanism of action of obinutuzumab,” Dr. Rovin explained.

Phase 3 trials to start early 2020

All of the serologies relevant to lupus and lupus nephritis “including C3 and C4 improved while antidoubled stranded DNA levels declined, as did the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, although the decline was more rapid and more profound in the obinutuzumab-treated patients,” Dr. Rovin said.

Importantly as well, despite the profound B-cell depletion produced by obinutuzumab, “the adverse event profile of this drug was very similar to the placebo group,” he stressed.

As expected, rates of infusion reactions were slightly higher in the experimental group than the immunosuppression alone group, but rates of serious adverse events were the same between groups, as were adverse infectious events, he noted.

Investigators have now initiated a global phase 3 trial, scheduled to start in early 2020, to evaluate the same treatment protocol in a larger group of patients.

Kidney Week 2019. Abstract #FR-OR136. Presented Nov. 8, 2019.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON – A novel antibody, obinutuzumab, enhances renal responses in patients with lupus nephritis, through more complete B-cell depletion, compared with standard immunotherapy, and is well tolerated, according to results from the phase 2 NOBILITY trial.

“We know from our previous trials with anti–B-cell antibodies that results were mixed and we felt that these variable results were possibly due to variability in B-cell depletion with a type 1 anti-CD20 antibody such as rituximab,” Brad Rovin, MD, director, division of nephrology, Ohio State University in Columbus, told a press briefing here at Kidney Week 2019: American Society of Nephrology annual meeting.

“So we hypothesized that if we could deplete B cells more efficiently and completely, we would achieve better results. At week 52, 35% of patients in the obinutuzumab-treated group achieved a complete renal response, compared to 23% in the standard-of-care arm.”

And by week 76, the difference between obinutuzumab and the standard of care was actually larger at 40% vs. 18%, respectively, “and this was statistically significant at a P value of .01,” added Dr. Rovin, who presented the full findings of the study at the conference.

Obinutuzumab, a highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody, is already approved under the brand name Gazyva for use in certain leukemias and lymphomas. The NOBILITY study was funded by Genentech-Roche, and Dr. Rovin reported being a consultant for the company.

Asked by Medscape Medical News to comment on the study, Duvuru Geetha, MBBS, noted that with standard-of-care mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus corticosteroids, “the remissions rates we achieve [for lupus nephritis] are still not great,” ranging from 30% to 50%, depending on the patient population.

“This is why there is a need for alternative agents,” added Dr. Geetha, who is an associate professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

With obinutuzumab, “the data look very promising because there is a much more profound and sustained effect on B-cell depletion and the renal response rate is much higher [than with MMF and corticosteroids],” she noted.

Dr. Geetha added, however, that she presumes patients were all premedicated with prophylactic agents to prevent infectious events, as they are when treated with rituximab.

“I think what is definitely different about this drug is that it induces direct cell death more efficiently than rituximab and that is probably what’s accounting for the higher efficacy seen with it,” said Dr. Geetha, who disclosed having received honoraria from Genentech a number of years ago.

“So yes, I believe the results are clinically meaningful,” she concluded.

NOBILITY study design

The NOBILITY trial randomized 125 patients with Class III or IV lupus nephritis to either obinutuzumab plus MMF and corticosteroids, or to MMF plus corticosteroids alone, for a treatment interval of 104 weeks.

Patients in the obinutuzumab group received two infusions of the highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody at week 0 and week 2 and another two infusions at 6 months.

“The primary endpoint was complete renal response at week 52,” the authors wrote, “while key secondary endpoints included overall renal response and modified complete renal response.”

Both at week 52 and week 76, more patients in the obinutuzumab group achieved an overall renal response as well as a modified complete renal response, compared with those treated with immunosuppression alone.

“If you look at the complete renal response over time, you can see that the curves separate after about 6 months but the placebo group starts to decline as you go further out, whereas the obinutuzumab group continues to separate, so my prediction is that we are going to see this trend continue because of the mechanism of action of obinutuzumab,” Dr. Rovin explained.

Phase 3 trials to start early 2020

All of the serologies relevant to lupus and lupus nephritis “including C3 and C4 improved while antidoubled stranded DNA levels declined, as did the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, although the decline was more rapid and more profound in the obinutuzumab-treated patients,” Dr. Rovin said.

Importantly as well, despite the profound B-cell depletion produced by obinutuzumab, “the adverse event profile of this drug was very similar to the placebo group,” he stressed.

As expected, rates of infusion reactions were slightly higher in the experimental group than the immunosuppression alone group, but rates of serious adverse events were the same between groups, as were adverse infectious events, he noted.

Investigators have now initiated a global phase 3 trial, scheduled to start in early 2020, to evaluate the same treatment protocol in a larger group of patients.

Kidney Week 2019. Abstract #FR-OR136. Presented Nov. 8, 2019.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON – A novel antibody, obinutuzumab, enhances renal responses in patients with lupus nephritis, through more complete B-cell depletion, compared with standard immunotherapy, and is well tolerated, according to results from the phase 2 NOBILITY trial.

“We know from our previous trials with anti–B-cell antibodies that results were mixed and we felt that these variable results were possibly due to variability in B-cell depletion with a type 1 anti-CD20 antibody such as rituximab,” Brad Rovin, MD, director, division of nephrology, Ohio State University in Columbus, told a press briefing here at Kidney Week 2019: American Society of Nephrology annual meeting.

“So we hypothesized that if we could deplete B cells more efficiently and completely, we would achieve better results. At week 52, 35% of patients in the obinutuzumab-treated group achieved a complete renal response, compared to 23% in the standard-of-care arm.”

And by week 76, the difference between obinutuzumab and the standard of care was actually larger at 40% vs. 18%, respectively, “and this was statistically significant at a P value of .01,” added Dr. Rovin, who presented the full findings of the study at the conference.

Obinutuzumab, a highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody, is already approved under the brand name Gazyva for use in certain leukemias and lymphomas. The NOBILITY study was funded by Genentech-Roche, and Dr. Rovin reported being a consultant for the company.

Asked by Medscape Medical News to comment on the study, Duvuru Geetha, MBBS, noted that with standard-of-care mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus corticosteroids, “the remissions rates we achieve [for lupus nephritis] are still not great,” ranging from 30% to 50%, depending on the patient population.

“This is why there is a need for alternative agents,” added Dr. Geetha, who is an associate professor of medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

With obinutuzumab, “the data look very promising because there is a much more profound and sustained effect on B-cell depletion and the renal response rate is much higher [than with MMF and corticosteroids],” she noted.

Dr. Geetha added, however, that she presumes patients were all premedicated with prophylactic agents to prevent infectious events, as they are when treated with rituximab.

“I think what is definitely different about this drug is that it induces direct cell death more efficiently than rituximab and that is probably what’s accounting for the higher efficacy seen with it,” said Dr. Geetha, who disclosed having received honoraria from Genentech a number of years ago.

“So yes, I believe the results are clinically meaningful,” she concluded.

NOBILITY study design

The NOBILITY trial randomized 125 patients with Class III or IV lupus nephritis to either obinutuzumab plus MMF and corticosteroids, or to MMF plus corticosteroids alone, for a treatment interval of 104 weeks.

Patients in the obinutuzumab group received two infusions of the highly engineered anti-CD20 antibody at week 0 and week 2 and another two infusions at 6 months.

“The primary endpoint was complete renal response at week 52,” the authors wrote, “while key secondary endpoints included overall renal response and modified complete renal response.”

Both at week 52 and week 76, more patients in the obinutuzumab group achieved an overall renal response as well as a modified complete renal response, compared with those treated with immunosuppression alone.

“If you look at the complete renal response over time, you can see that the curves separate after about 6 months but the placebo group starts to decline as you go further out, whereas the obinutuzumab group continues to separate, so my prediction is that we are going to see this trend continue because of the mechanism of action of obinutuzumab,” Dr. Rovin explained.

Phase 3 trials to start early 2020

All of the serologies relevant to lupus and lupus nephritis “including C3 and C4 improved while antidoubled stranded DNA levels declined, as did the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, although the decline was more rapid and more profound in the obinutuzumab-treated patients,” Dr. Rovin said.

Importantly as well, despite the profound B-cell depletion produced by obinutuzumab, “the adverse event profile of this drug was very similar to the placebo group,” he stressed.

As expected, rates of infusion reactions were slightly higher in the experimental group than the immunosuppression alone group, but rates of serious adverse events were the same between groups, as were adverse infectious events, he noted.

Investigators have now initiated a global phase 3 trial, scheduled to start in early 2020, to evaluate the same treatment protocol in a larger group of patients.

Kidney Week 2019. Abstract #FR-OR136. Presented Nov. 8, 2019.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves cefiderocol for multidrug-resistant, complicated urinary tract infections

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

FROM THE FDA

New model for CKD risk draws on clinical, demographic factors

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

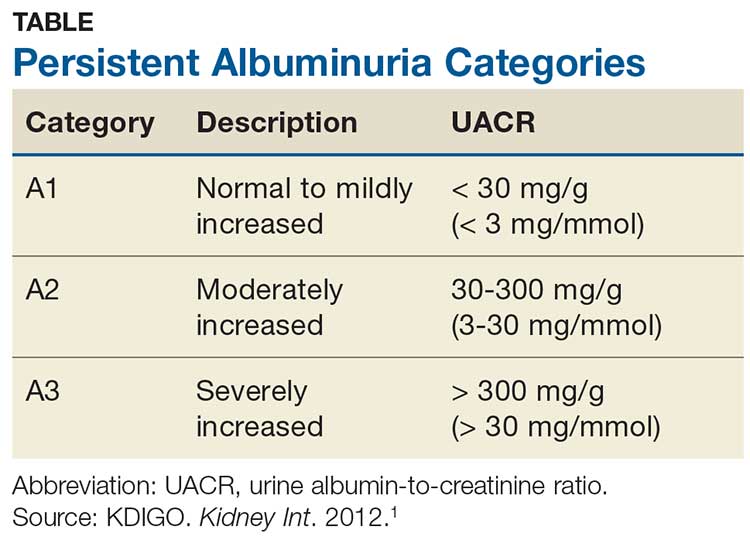

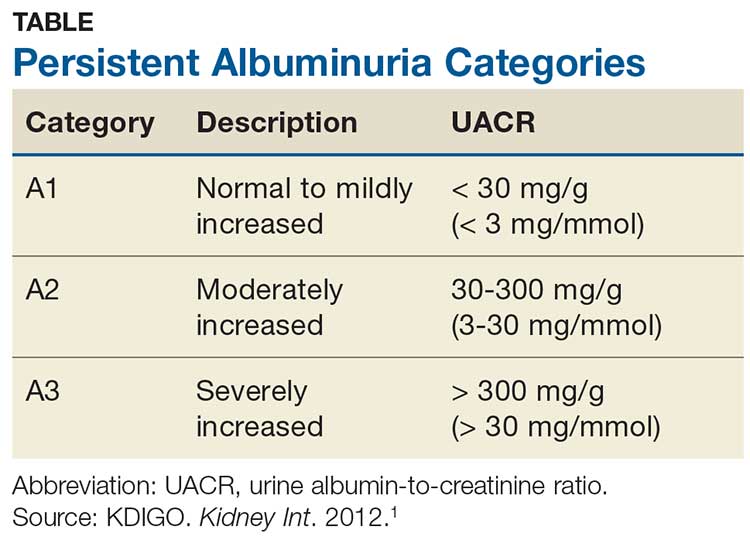

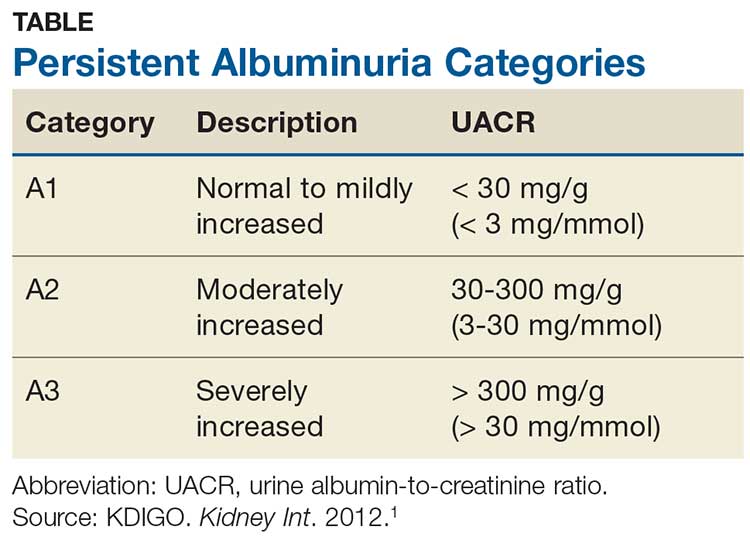

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Data from more than 5 million individuals has been used to develop an equation for predicting the risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with or without diabetes, according to a presentation at Kidney Week 2019, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

In a paper published simultaneously online in JAMA, researchers reported the outcome of an individual-level data analysis of 34 multinational cohorts involving 5,222,711 individuals – including 781,627 with diabetes – from 28 countries as part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium.

“An equation for kidney failure risk may help improve care for patients with established CKD, but relatively little work has been performed to develop predictive tools to identify those at increased risk of developing CKD – defined by reduced eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate], despite the high lifetime risk of CKD – which is estimated to be 59.1% in the United States,” wrote Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Phoenix and colleagues.

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, 15% of individuals without diabetes and 40% of individuals with diabetes developed incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73m2.

The key risk factors were older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lower eGFR values, and higher urine albumin to creatinine ratio. Smoking was also significantly associated with reduced eGFR but only in cohorts without diabetes. In cohorts with diabetes, elevated hemoglobin A1c and the presence and type of diabetes medication were also significantly associated with reduced eGFR.

Using this information, the researchers developed a prediction model built from weighted-average hazard ratios and validated it in nine external validation cohorts of 18 study populations involving a total of 2,253,540 individuals. They found that in 16 of the 18 study populations, the slope of observed to predicted risk ranged from 0.80 to 1.25.

Moreover, in the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890) and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes, the investigators reported.

“Several models have been developed for estimating the risk of prevalent and incident CKD and end-stage kidney disease, but even those with good discriminative performance have not always performed well for cohorts of people outside the original derivation cohort,” the authors wrote. They argued that their model “demonstrated high discrimination and variable calibration in diverse populations.”

However, they stressed that further study was needed to determine if use of the equations would actually lead to improvements in clinical care and patient outcomes. In an accompanying editorial, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, MD, and Michelle M. Estrella, MD, of the Kidney Health Research Collaborative at the University of California, San Francisco, said the study and its focus on primary, rather than secondary, prevention of kidney disease is a critical step toward reducing the burden of that disease, especially given that an estimated 37 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease.

It is also important, they added, that primary prevention of kidney disease is tailored to the individual patient’s risk because risk prediction and screening strategies are unlikely to improve outcomes if they are not paired with effective individualized interventions, such as lifestyle modification or management of blood pressure.

These risk equations could be more holistic by integrating the prediction of both elevated albuminuria and reduced eGFR because more than 40% of individuals with chronic kidney disease have increased albuminuria without reduced eGFR, they noted (JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17378).

The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In the cohorts without diabetes, the risk equations had a median C-statistic for the 5-year predicted probability of 0.845 (interquartile range, 0.789-0.890), and of 0.801 (IQR, 0.750-0.819) in the cohorts with diabetes,

Study details: Analysis of cohort data from 5,222,711 individuals, including 781,627 with diabetes.

Disclosures: The study and CKD Prognosis Consortium were supported by the U.S. National Kidney Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation. Nine authors declared grants, consultancies, and other support from the private sector and research organizations. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Tummalapalli and Dr. Estrella reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nelson R et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17379.

Severe hypercalcemia in a 54-year-old woman

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)

- Vitamin B12 194 pg/mL (239–931)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.21 mIU/ L (0.47–4.68

- Free thyroxine 1.27 ng/dL (0.78–2.19)

- Iron 103 µg/dL (37–170)

- Total iron-binding capacity 335 µg/dL (265–497)

- Transferrin 248 mg/dL (206–381)

- Ferritin 66 ng/mL (11.1–264)

- Urine protein (random) 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- Urine microalbumin (random) 5.9 mg/dL (0–1.6)

- Urine creatinine clearance 88.5 mL/min (88–128)

- Urine albumin-creatinine ratio 66.66 mg/g (< 30).

Imaging reports

A nuclear bone scan showed increased bone uptake in the hip and both shoulders, consistent with arthritis, and increased activity in 2 of the lower left ribs, associated with rib fractures secondary to lytic lesions. A skeletal survey at a later date showed multiple well-circumscribed “punched-out” lytic lesions in both forearms and both femurs.

2. What should be the next step in this patient’s management?

- Intravenous (IV) fluids

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonate treatment

- Denosumab

- Hemodialysis

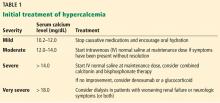

Initial treatment of severe hypercalcemia includes the following:

Start IV isotonic fluids at a rate of 150 mL/h (if the patient is making urine) to maintain urine output at more than 100 mL/h. Closely monitor urine output.

Give calcitonin 4 IU/kg in combination with IV fluids to reduce calcium levels within the first 12 to 48 hours of treatment.

Give a bisphosphonate, eg, zoledronic acid 4 mg over 15 minutes, or pamidronate 60 to 90 mg over 2 hours. Zoledronic acid is preferred in malignancy-induced hypercalcemia because it is more potent. Doses should be adjusted in patients with renal failure.

Give denosumab if hypercalcemia is refractory to bisphosphonates, or when bisphosphonates cannot be used in renal failure.9

Hemodialysis is performed in patients who have significant neurologic symptoms irrespective of acute renal insufficiency.

Our patient was started on 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 150 mL/h for severe hypercalcemia. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV was given once. These measures lowered her calcium level and lessened her acute kidney injury.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Urine testing was positive for Bence Jones protein. Immune electrophoresis, performed because of suspicion of multiple myeloma, showed an elevated level of kappa light chains at 806.7 mg/dL (0.33–1.94) and normal lambda light chains at 0.62 mg/dL (0.57–2.63). The immunoglobulin G level was low at 496 mg/dL (610–1,660). In patients with severe hypercalcemia, these results point to a diagnosis of malignancy. Bone marrow aspiration study showed greater than 10% plasma cells, confirming multiple myeloma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based in part on the presence of 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cells10 and of specific end-organ damage (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or bone lesions).9

Bone marrow clonality can be shown by the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains as detected with immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry.11 The normal ratio is 0.26 to 1.65 for a patient with normal kidney function. In this patient, however, the ratio was 1,301.08 (806.67 kappa to 0.62 lambda), which was extremely out of range. The patient’s bone marrow biopsy results revealed the presence of 15% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

Multiple myeloma causes osteolytic lesions through increased activation of osteoclast activating factor that stimulates the growth of osteoclast precursors. At the same time, it inhibits osteoblast formation via multiple pathways, including the action of sclerostin.11 Our patient had lytic lesions in 2 left lower ribs and in both forearms and femurs.

Hypercalcemia in multiple myeloma is attributed to 2 main factors: bone breakdown and macrophage overactivation. Multiple myeloma cells increase the release of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, which are inflammatory proteins that cause an increase in macrophages, which cause an increase in calcitriol.11 As noted, our patient’s calcium level at presentation was 18.4 mg/dL uncorrected and 18.96 mg/dL corrected.

Cast nephropathy can occur in the distal tubules from the increased free light chains circulating and combining with Tamm-Horsfall protein, which in turn causes obstruction and local inflammation,12 leading to a rise in creatinine levels and resulting in acute kidney injury,12 as in our patient.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Our patient was referred to an oncologist for management.

In the management of multiple myeloma, the patient’s quality of life needs to be considered. With the development of new agents to combat the damages of the osteolytic effects, there is hope for improving quality of life.13,14 New agents under study include anabolic agents such as antisclerostin and anti-Dickkopf-1, which promote osteoblastogenesis, leading to bone formation, with the possibility of repairing existing damage.15

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- If hypercalcemia is mild to moderate, consider primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Identify patients with severe symptoms of hypercalcemia such as volume depletion, acute kidney injury, arrhythmia, or seizures.

- Confirm severe cases of hypercalcemia and treat severe cases effectively.

- Severe hypercalcemia may need further investigation into a potential underlying malignancy.

- Sternlicht H, Glezerman IG. Hypercalcemia of malignancy and new treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11:1779–1788. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S83681

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11(6):395–400. doi:10.1002/clc.4960110607

- Bilezikian JP, Cusano NE, Khan AA, Liu JM, Marcocci C, Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.33

- Kuchay MS, Kaur P, Mishra SK, Mithal A. The changing profile of hypercalcemia in a tertiary care setting in North India: an 18-month retrospective study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14(2):131–135. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.131

- Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10):1722–1729. doi:10.2215/CJN.02470312

- Ai L, Mu S, Hu Y. Prognostic role of RDW in hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 2018; 18:61. doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0558-3

- Baz R, Alemany C, Green R, Hussein MA. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias: a retrospective review. Cancer 2004; 101(4):790–795. doi:10.1002/cncr.20441

- Elmore JG, Carney PA, Abraham LA, et al. The association between obesity and screening mammography accuracy. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(10):1140–1147. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1140

- Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(27–28):470–476. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2016; 91(7):719–734. doi:10.1002/ajh.24402

- Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol 2013; 2(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.001

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW; American Society of Nephrology Onco-Nephrology Forum. Paraprotein-related kidney disease: kidney injury from paraproteins—what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11(12):2288–2294. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560316

- Reece D. Update on the initial therapy of multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e307

- Nishida H. Bone-targeted agents in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep 2018; 10(1):7401. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7401

- Ring ES, Lawson MA, Snowden JA, Jolley I, Chantry AD. New agents in the treatment of myeloma bone disease. Calcif Tissue Int 2018; 102(2):196–209. doi:10.1007/s00223-017-0351-7

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)