User login

Low blood pressure may harm rather than help patients with chronic kidney disease

In a large, national cohort study of U.S. veterans with non–dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures were associated with lower mortality rates – but only when the diastolic value was higher than about 70 mm Hg.

In addition, mortality rates were significantly increased among those patients with "ideal" blood pressure values (less than 130/80 mm Hg), "because of the inclusion of patients with low SBP and DBP," reported Dr. Csaba P. Kovesdy, chief of nephrology at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and his associates. The study was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Aug. 19 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:233-42).

The results indicate that current guidelines for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which recommend a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 130 mm Hg or lower "at the expense of lowering DBP [diastolic blood pressure] to less than approximately 70 mm Hg," may be harmful, they concluded. However, one of the limitations of the study was that it was an observational study and cannot establish a causal association, so "clinical trials are needed to inform us about the ideal BP target for antihypertensive therapy in patients with CKD," they added.

Using more than 18 million BP readings, the study evaluated the association of SBP and DBP values separately and SBP/DBP combinations on all-cause mortality in almost 652,000 U.S. veterans with CKD, who were not dependent on dialysis, between 2005 and 2012. Their mean age was 74 years, most were male (97%), 88% were white, 9% were black, 43% had coronary artery disease, and 43% had diabetes. The mean SBP values at baseline were 135 mm Hg while the mean DBP was 72 mm Hg; the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 50.4 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The study looked at 96 different SBP/DBP combinations. During the time period of the study, 238,640 patients died.

They identified a U-shaped curve when analyzing mortality with SBP and DBP separately, "with both lower and higher levels showing a substantial and statistically significant association" with mortality risk. Based on the adjusted hazard ratios for the combinations of SBP and DBP, the lowest mortality rates were associated with blood pressures of 130-139/90-99 mm Hg, and 130-159/70-89 mm Hg, adjusted for factors that included age, sex, race, diabetes, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, age and medication use).

But combinations of lower SBP and DBP values "were associated with relatively lower mortality rates only if the lower DBP component was greater than approximately 70 mm Hg," they said.

When evaluating risk based on JNC 7 (Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) categories,they found that that those with stage 1 hypertension (SBP of 140-159 mm Hg or DBP of 90-99 mm Hg) were associated with the lowest mortality rates, while those in the normal category (an SBP lower than 120 and a DBP below 80) had the highest mortality rates," results that were independent of confounding factors and were statistically significant.

The authors described an elevated SBP combined with a low DBP, which is common in CKD patients, as "an especially problematic BP pattern," they said, pointing out that 33% of the patients had an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg and a DBP less than 70 mm Hg at some point during the study period.

The study strengths included the large size and the representation of the U.S. veterans’ population, but the limitations included the mostly male population and the observational design of the study, so more studies are needed, the authors said. "Until such trials become available, low BP should be regarded as potentially deleterious in this patient population, and we suggest caution in lowering BP to less than what has been demonstrated as beneficial in randomized controlled trials," they concluded.

Dr. Kovesdy, professor of medicine at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, disclosed having received grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and nonfinancial support from the Department of Veterans Affairs while the study was conducted. Four authors had no disclosures, and one author disclosed having received NIH grants during the study. The remaining two authors disclosed having received research grants or personal fees from different pharmaceutical companies.

While the study results raise questions about the optimal BP targets in patients with CKD, "these are observational data with attendant limitations," Dr. Dena Rifkin and Dr. Mark Sarnak wrote in an accompanying editorial,

"A seemingly acceptable SBP combined with a low DBP may be a cause for concern, especially in older patients with CKD and comorbid conditions." However, "lower [systolic blood pressure] and [diastolic blood pressure] may be markers of the severity of chronic illness or vascular disease," they wrote, adding that the results "may not generalize beyond older white men with stage 3A CKD, and the fact that only a small percentage of persons had proteinuria measurements makes it difficult to draw any conclusions regarding applicability to proteinuric CKD." (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:302-3).

Dr. Rifkin is a nephrologist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, San Diego; and Dr. Sarnak is with the division of nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Rifkin had no disclosures. Dr. Sarnak disclosed having been a member of the KDIGO (Kidney disease improving global outcomes) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in CKD workgroup.

While the study results raise questions about the optimal BP targets in patients with CKD, "these are observational data with attendant limitations," Dr. Dena Rifkin and Dr. Mark Sarnak wrote in an accompanying editorial,

"A seemingly acceptable SBP combined with a low DBP may be a cause for concern, especially in older patients with CKD and comorbid conditions." However, "lower [systolic blood pressure] and [diastolic blood pressure] may be markers of the severity of chronic illness or vascular disease," they wrote, adding that the results "may not generalize beyond older white men with stage 3A CKD, and the fact that only a small percentage of persons had proteinuria measurements makes it difficult to draw any conclusions regarding applicability to proteinuric CKD." (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:302-3).

Dr. Rifkin is a nephrologist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, San Diego; and Dr. Sarnak is with the division of nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Rifkin had no disclosures. Dr. Sarnak disclosed having been a member of the KDIGO (Kidney disease improving global outcomes) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in CKD workgroup.

While the study results raise questions about the optimal BP targets in patients with CKD, "these are observational data with attendant limitations," Dr. Dena Rifkin and Dr. Mark Sarnak wrote in an accompanying editorial,

"A seemingly acceptable SBP combined with a low DBP may be a cause for concern, especially in older patients with CKD and comorbid conditions." However, "lower [systolic blood pressure] and [diastolic blood pressure] may be markers of the severity of chronic illness or vascular disease," they wrote, adding that the results "may not generalize beyond older white men with stage 3A CKD, and the fact that only a small percentage of persons had proteinuria measurements makes it difficult to draw any conclusions regarding applicability to proteinuric CKD." (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:302-3).

Dr. Rifkin is a nephrologist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, San Diego; and Dr. Sarnak is with the division of nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Rifkin had no disclosures. Dr. Sarnak disclosed having been a member of the KDIGO (Kidney disease improving global outcomes) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in CKD workgroup.

In a large, national cohort study of U.S. veterans with non–dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures were associated with lower mortality rates – but only when the diastolic value was higher than about 70 mm Hg.

In addition, mortality rates were significantly increased among those patients with "ideal" blood pressure values (less than 130/80 mm Hg), "because of the inclusion of patients with low SBP and DBP," reported Dr. Csaba P. Kovesdy, chief of nephrology at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and his associates. The study was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Aug. 19 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:233-42).

The results indicate that current guidelines for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which recommend a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 130 mm Hg or lower "at the expense of lowering DBP [diastolic blood pressure] to less than approximately 70 mm Hg," may be harmful, they concluded. However, one of the limitations of the study was that it was an observational study and cannot establish a causal association, so "clinical trials are needed to inform us about the ideal BP target for antihypertensive therapy in patients with CKD," they added.

Using more than 18 million BP readings, the study evaluated the association of SBP and DBP values separately and SBP/DBP combinations on all-cause mortality in almost 652,000 U.S. veterans with CKD, who were not dependent on dialysis, between 2005 and 2012. Their mean age was 74 years, most were male (97%), 88% were white, 9% were black, 43% had coronary artery disease, and 43% had diabetes. The mean SBP values at baseline were 135 mm Hg while the mean DBP was 72 mm Hg; the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 50.4 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The study looked at 96 different SBP/DBP combinations. During the time period of the study, 238,640 patients died.

They identified a U-shaped curve when analyzing mortality with SBP and DBP separately, "with both lower and higher levels showing a substantial and statistically significant association" with mortality risk. Based on the adjusted hazard ratios for the combinations of SBP and DBP, the lowest mortality rates were associated with blood pressures of 130-139/90-99 mm Hg, and 130-159/70-89 mm Hg, adjusted for factors that included age, sex, race, diabetes, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, age and medication use).

But combinations of lower SBP and DBP values "were associated with relatively lower mortality rates only if the lower DBP component was greater than approximately 70 mm Hg," they said.

When evaluating risk based on JNC 7 (Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) categories,they found that that those with stage 1 hypertension (SBP of 140-159 mm Hg or DBP of 90-99 mm Hg) were associated with the lowest mortality rates, while those in the normal category (an SBP lower than 120 and a DBP below 80) had the highest mortality rates," results that were independent of confounding factors and were statistically significant.

The authors described an elevated SBP combined with a low DBP, which is common in CKD patients, as "an especially problematic BP pattern," they said, pointing out that 33% of the patients had an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg and a DBP less than 70 mm Hg at some point during the study period.

The study strengths included the large size and the representation of the U.S. veterans’ population, but the limitations included the mostly male population and the observational design of the study, so more studies are needed, the authors said. "Until such trials become available, low BP should be regarded as potentially deleterious in this patient population, and we suggest caution in lowering BP to less than what has been demonstrated as beneficial in randomized controlled trials," they concluded.

Dr. Kovesdy, professor of medicine at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, disclosed having received grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and nonfinancial support from the Department of Veterans Affairs while the study was conducted. Four authors had no disclosures, and one author disclosed having received NIH grants during the study. The remaining two authors disclosed having received research grants or personal fees from different pharmaceutical companies.

In a large, national cohort study of U.S. veterans with non–dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures were associated with lower mortality rates – but only when the diastolic value was higher than about 70 mm Hg.

In addition, mortality rates were significantly increased among those patients with "ideal" blood pressure values (less than 130/80 mm Hg), "because of the inclusion of patients with low SBP and DBP," reported Dr. Csaba P. Kovesdy, chief of nephrology at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and his associates. The study was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Aug. 19 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:233-42).

The results indicate that current guidelines for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which recommend a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 130 mm Hg or lower "at the expense of lowering DBP [diastolic blood pressure] to less than approximately 70 mm Hg," may be harmful, they concluded. However, one of the limitations of the study was that it was an observational study and cannot establish a causal association, so "clinical trials are needed to inform us about the ideal BP target for antihypertensive therapy in patients with CKD," they added.

Using more than 18 million BP readings, the study evaluated the association of SBP and DBP values separately and SBP/DBP combinations on all-cause mortality in almost 652,000 U.S. veterans with CKD, who were not dependent on dialysis, between 2005 and 2012. Their mean age was 74 years, most were male (97%), 88% were white, 9% were black, 43% had coronary artery disease, and 43% had diabetes. The mean SBP values at baseline were 135 mm Hg while the mean DBP was 72 mm Hg; the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 50.4 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The study looked at 96 different SBP/DBP combinations. During the time period of the study, 238,640 patients died.

They identified a U-shaped curve when analyzing mortality with SBP and DBP separately, "with both lower and higher levels showing a substantial and statistically significant association" with mortality risk. Based on the adjusted hazard ratios for the combinations of SBP and DBP, the lowest mortality rates were associated with blood pressures of 130-139/90-99 mm Hg, and 130-159/70-89 mm Hg, adjusted for factors that included age, sex, race, diabetes, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, age and medication use).

But combinations of lower SBP and DBP values "were associated with relatively lower mortality rates only if the lower DBP component was greater than approximately 70 mm Hg," they said.

When evaluating risk based on JNC 7 (Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) categories,they found that that those with stage 1 hypertension (SBP of 140-159 mm Hg or DBP of 90-99 mm Hg) were associated with the lowest mortality rates, while those in the normal category (an SBP lower than 120 and a DBP below 80) had the highest mortality rates," results that were independent of confounding factors and were statistically significant.

The authors described an elevated SBP combined with a low DBP, which is common in CKD patients, as "an especially problematic BP pattern," they said, pointing out that 33% of the patients had an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg and a DBP less than 70 mm Hg at some point during the study period.

The study strengths included the large size and the representation of the U.S. veterans’ population, but the limitations included the mostly male population and the observational design of the study, so more studies are needed, the authors said. "Until such trials become available, low BP should be regarded as potentially deleterious in this patient population, and we suggest caution in lowering BP to less than what has been demonstrated as beneficial in randomized controlled trials," they concluded.

Dr. Kovesdy, professor of medicine at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, disclosed having received grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and nonfinancial support from the Department of Veterans Affairs while the study was conducted. Four authors had no disclosures, and one author disclosed having received NIH grants during the study. The remaining two authors disclosed having received research grants or personal fees from different pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Major finding: The results – which include the finding that a diastolic blood pressure value below 70 mm Hg was associated with higher mortality in patients with chronic kidney failure who were not on dialysis – indicate that low blood pressure could be considered possibly harmful in this population.

Data source: A national cohort study of 651,749 U.S. veterans with non–dialysis dependent CKD evaluated the association of systolic and diastolic BP values, separately and combined, on mortality risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The lead author disclosed having received grants from the NIH-NIDDK and nonfinancial support from the V.A. while the study was conducted. Four authors had no disclosures, and one author disclosed having received NIH grants during the study. The remaining two authors disclosed having received research grants or personal fees from different pharmaceutical companies.

Determining Renal Function: What Those Test Results Mean

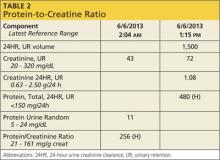

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

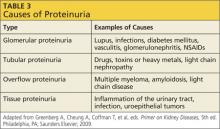

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Determining Renal Function: What’s the Best Way to Evaluate?

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

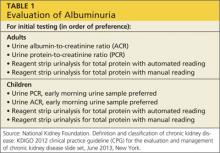

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Fracture risk varied by renal function equations

SAN FRANCISCO – Assessing renal health using a modified Cockroft-Gault equation to measure creatinine clearance was more sensitive than using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate when estimating risk for osteoporosis and fracture, an award-winning study of 400 postmenopausal Puerto Rican women showed.

The study found a high prevalence of mild renal dysfunction (stage 2 chronic kidney disease) in 54%-59% of women, depending on the equation used. With the Cockroft-Gault equation adjusted for body surface area, a determination of mild renal dysfunction was associated with significantly decreased bone mineral density and with a doubling in risk for vertebral or nonvertebral fractures. When the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was used, however, no significant associations were found between mild renal dysfunction and fracture risk, Dr. Loida A. González-Rodriguez reported.

Previous data have shown that severe renal dysfunction is associated with reduced bone mineral density and fractures, and that a creatinine clearance below 65 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is associated with a higher risk for falls and hip fractures in elderly people. Less is known about the effects of mild renal dysfunction on bone mineral density.

"We are postulating that this Cockroft-Gault equation is better to estimate bone," because it includes factors such as weight and age, and is adjusted for body surface area, Dr. González-Rodriguez said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society. She received an award at the meeting for her retrospective secondary analysis of data from the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study, the first population-based study of vertebral fractures in Latin America.

Many clinicians use the MDRD equation to estimate renal function. Dr. González-Rodriguez of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, said she has switched to using the Cockroft-Gault equation, and is trying to get colleagues at her institution to do the same. The MDRD equation will miss some patients who are at risk for osteopenia, osteoporosis, and fracture, she said.

Seventeen percent of patients in the study had normal bone mineral density, 43% had osteopenia, and 41% had osteoporosis. (Percentages were rounded and so exceed 100%.)

When the Cockroft-Gault equation was used to categorize renal function, 9% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 54% had stage 2, 35% had stage 3, and 2% had stage 4. When the MDRD equation was used, 2% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 59% had stage 2, 38% had stage 3, and 1% had stage 4.

Among patients with stage 2 chronic kidney disease as assessed by the Cockroft-Gault equation, 19% had normal bone mineral density, 49% had osteopenia, and 32% had osteoporosis. Among patients with stage 2 disease assessed using the MDRD equation, 4% had normal bone mineral density, 35% had osteopenia, and 60% had osteoporosis.

Vertebral fractures occurred in 9% and nonvertebral fractures occurred in 18% of patients with stage 2 disease assessed with the Cockroft-Gault equation. When the MDRD equation was used, 9% of patients with stage 2 disease developed vertebral fractures and 24% developed nonvertebral fractures.

Among patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease assessed using the Cockroft-Gault equation, 18% developed vertebral fractures and 31% developed nonvertebral fractures, compared with vertebral fractures in 16% and nonvertebral fractures in 22% of patients with stage 3 disease assessed using the MDRD equation.

"One of the most important risk factors for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures is osteoporosis," Dr. González-Rodriguez noted. "So, if we can identify earlier the patients that have mild renal dysfunction" using the Cockroft-Gault equation and manage the osteoporosis risk, some fractures may be prevented.

The findings are limited by the retrospective design of the study, a lack of blood pressure measurements to assess arterial hypertension, self-reported nonvertebral fractures, and a lack of measurements of intact parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and microalbuminuria.

Dr. González-Rodriguez reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities funded the study.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Assessing renal health using a modified Cockroft-Gault equation to measure creatinine clearance was more sensitive than using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate when estimating risk for osteoporosis and fracture, an award-winning study of 400 postmenopausal Puerto Rican women showed.

The study found a high prevalence of mild renal dysfunction (stage 2 chronic kidney disease) in 54%-59% of women, depending on the equation used. With the Cockroft-Gault equation adjusted for body surface area, a determination of mild renal dysfunction was associated with significantly decreased bone mineral density and with a doubling in risk for vertebral or nonvertebral fractures. When the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was used, however, no significant associations were found between mild renal dysfunction and fracture risk, Dr. Loida A. González-Rodriguez reported.

Previous data have shown that severe renal dysfunction is associated with reduced bone mineral density and fractures, and that a creatinine clearance below 65 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is associated with a higher risk for falls and hip fractures in elderly people. Less is known about the effects of mild renal dysfunction on bone mineral density.

"We are postulating that this Cockroft-Gault equation is better to estimate bone," because it includes factors such as weight and age, and is adjusted for body surface area, Dr. González-Rodriguez said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society. She received an award at the meeting for her retrospective secondary analysis of data from the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study, the first population-based study of vertebral fractures in Latin America.

Many clinicians use the MDRD equation to estimate renal function. Dr. González-Rodriguez of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, said she has switched to using the Cockroft-Gault equation, and is trying to get colleagues at her institution to do the same. The MDRD equation will miss some patients who are at risk for osteopenia, osteoporosis, and fracture, she said.

Seventeen percent of patients in the study had normal bone mineral density, 43% had osteopenia, and 41% had osteoporosis. (Percentages were rounded and so exceed 100%.)

When the Cockroft-Gault equation was used to categorize renal function, 9% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 54% had stage 2, 35% had stage 3, and 2% had stage 4. When the MDRD equation was used, 2% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 59% had stage 2, 38% had stage 3, and 1% had stage 4.

Among patients with stage 2 chronic kidney disease as assessed by the Cockroft-Gault equation, 19% had normal bone mineral density, 49% had osteopenia, and 32% had osteoporosis. Among patients with stage 2 disease assessed using the MDRD equation, 4% had normal bone mineral density, 35% had osteopenia, and 60% had osteoporosis.

Vertebral fractures occurred in 9% and nonvertebral fractures occurred in 18% of patients with stage 2 disease assessed with the Cockroft-Gault equation. When the MDRD equation was used, 9% of patients with stage 2 disease developed vertebral fractures and 24% developed nonvertebral fractures.

Among patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease assessed using the Cockroft-Gault equation, 18% developed vertebral fractures and 31% developed nonvertebral fractures, compared with vertebral fractures in 16% and nonvertebral fractures in 22% of patients with stage 3 disease assessed using the MDRD equation.

"One of the most important risk factors for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures is osteoporosis," Dr. González-Rodriguez noted. "So, if we can identify earlier the patients that have mild renal dysfunction" using the Cockroft-Gault equation and manage the osteoporosis risk, some fractures may be prevented.

The findings are limited by the retrospective design of the study, a lack of blood pressure measurements to assess arterial hypertension, self-reported nonvertebral fractures, and a lack of measurements of intact parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and microalbuminuria.

Dr. González-Rodriguez reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities funded the study.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Assessing renal health using a modified Cockroft-Gault equation to measure creatinine clearance was more sensitive than using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate when estimating risk for osteoporosis and fracture, an award-winning study of 400 postmenopausal Puerto Rican women showed.

The study found a high prevalence of mild renal dysfunction (stage 2 chronic kidney disease) in 54%-59% of women, depending on the equation used. With the Cockroft-Gault equation adjusted for body surface area, a determination of mild renal dysfunction was associated with significantly decreased bone mineral density and with a doubling in risk for vertebral or nonvertebral fractures. When the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was used, however, no significant associations were found between mild renal dysfunction and fracture risk, Dr. Loida A. González-Rodriguez reported.

Previous data have shown that severe renal dysfunction is associated with reduced bone mineral density and fractures, and that a creatinine clearance below 65 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is associated with a higher risk for falls and hip fractures in elderly people. Less is known about the effects of mild renal dysfunction on bone mineral density.

"We are postulating that this Cockroft-Gault equation is better to estimate bone," because it includes factors such as weight and age, and is adjusted for body surface area, Dr. González-Rodriguez said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society. She received an award at the meeting for her retrospective secondary analysis of data from the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study, the first population-based study of vertebral fractures in Latin America.

Many clinicians use the MDRD equation to estimate renal function. Dr. González-Rodriguez of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, said she has switched to using the Cockroft-Gault equation, and is trying to get colleagues at her institution to do the same. The MDRD equation will miss some patients who are at risk for osteopenia, osteoporosis, and fracture, she said.

Seventeen percent of patients in the study had normal bone mineral density, 43% had osteopenia, and 41% had osteoporosis. (Percentages were rounded and so exceed 100%.)

When the Cockroft-Gault equation was used to categorize renal function, 9% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 54% had stage 2, 35% had stage 3, and 2% had stage 4. When the MDRD equation was used, 2% of patients had stage 1 chronic kidney disease, 59% had stage 2, 38% had stage 3, and 1% had stage 4.

Among patients with stage 2 chronic kidney disease as assessed by the Cockroft-Gault equation, 19% had normal bone mineral density, 49% had osteopenia, and 32% had osteoporosis. Among patients with stage 2 disease assessed using the MDRD equation, 4% had normal bone mineral density, 35% had osteopenia, and 60% had osteoporosis.

Vertebral fractures occurred in 9% and nonvertebral fractures occurred in 18% of patients with stage 2 disease assessed with the Cockroft-Gault equation. When the MDRD equation was used, 9% of patients with stage 2 disease developed vertebral fractures and 24% developed nonvertebral fractures.

Among patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease assessed using the Cockroft-Gault equation, 18% developed vertebral fractures and 31% developed nonvertebral fractures, compared with vertebral fractures in 16% and nonvertebral fractures in 22% of patients with stage 3 disease assessed using the MDRD equation.

"One of the most important risk factors for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures is osteoporosis," Dr. González-Rodriguez noted. "So, if we can identify earlier the patients that have mild renal dysfunction" using the Cockroft-Gault equation and manage the osteoporosis risk, some fractures may be prevented.

The findings are limited by the retrospective design of the study, a lack of blood pressure measurements to assess arterial hypertension, self-reported nonvertebral fractures, and a lack of measurements of intact parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and microalbuminuria.

Dr. González-Rodriguez reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities funded the study.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT ENDO 2013

Major finding: Fracture risk doubled in women with mild renal dysfunction as assessed by the Cockroft-Gault equation but not when renal function was assessed using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

Data source: A retrospective secondary analysis of data on 400 postmenopausal Puerto Rican women.

Disclosures: Dr. Loida A. González-Rodriguez reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities funded the study.

Vascular testing appropriate use criteria cover 116 scenarios

Venous duplex ultrasound is rarely appropriate as a screening tool for upper or lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in the absence of pain or swelling, according to new appropriate use criteria for noninvasive vascular laboratory testing issued by the American College of Cardiology.

The clinical scenarios involving venous duplex ultrasound for DVT screening that were deemed rarely appropriate – such as screening in those with a prolonged ICU stay and those with high DVT risk – represent just a few of the 116 scenarios included in the report, which was developed in collaboration with 10 other leading professional societies to promote the most effective and most efficient use of peripheral vascular ultrasound and physiological testing in clinical practice.

The report, published online on July 19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the second in a two-part series evaluating noninvasive testing for peripheral vascular disorders. Part I, published last year (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:242-76), addressed peripheral arterial disorders, and Part II (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 July 19 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.001]) addresses venous disease and evaluation of hemodialysis access, according to Dr. Heather Gornik, chair of the Part II writing committee.

"Vascular laboratory tests really play a central role in evaluating patients with peripheral vascular disorders. They are noninvasive, they have good accuracy data, and they don’t require radiation or dye. But we want to make sure the right tests are being ordered for the right reasons," Dr. Gornik, a cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

Because these tests are low risk and easily accessible, there is concern that they are sometimes used excessively, she explained – specifically mentioning the use of duplex ultrasound for DVT screening as a commonly overused procedure.

"There is very little evidence, if any, to support broad screening for blood clots in someone who has no symptoms," she said.

The goal of the ACC Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force responsible for developing the criteria was to help clinicians minimize unnecessary testing, and maximize the most effective and efficient testing, she added.

Each of the clinical scenarios that were developed by the writing committee were rated by a technical panel as to whether they represent an "appropriate use," or whether they are "maybe appropriate" or "rarely appropriate."

The various scenarios are listed, along with their rating, in eight "at-a-glance" tables that address the following more general categories: venous duplex of the upper extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; venous duplex of the lower extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; duplex evaluation for venous incompetency; venous physiological testing with provocative maneuvers to assess for patency and/or incompetency; duplex of the inferior vena cava and iliac veins for patency and thrombosis; duplex of the hepatoportal system for patency, thrombosis, and flow direction; duplex of the renal vein for patency and thrombosis; and preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of a vascular access site.

Considering venous duplex ultrasound in a patient with acute unilateral limb swelling? Table 1 lists this as an appropriate use. How about duplex evaluation for venous incompetency in a patient with asymptomatic varicose veins? Table 3 says this may be appropriate, but notes that it is rarely appropriate in a patient with spider veins.

The report also covers indications for vascular testing prior to or after placement of hemodialysis access, because "evaluation of the superficial, deep, and central veins of the upper extremity constitutes a large component of these examinations," the report states.

In general, vascular studies were deemed appropriate in the presence of clinical signs and symptoms. The report also shows that the vascular laboratory plays a central role in the evaluation of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, and that preoperative vascular testing for preparing a dialysis access site is appropriate within three months of the procedure – but not for general surveillance of a functional dialysis fistula or graft in the absence of an indication of a problem, such as a palpable mass or swelling in the arm.

The report is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather is an attempt to address common and important clinical scenarios encountered in the patient with manifestations of peripheral vascular disease, the authors noted.

"The beauty of this report is that it spans many disciplines," Dr. Gornik said, noting that numerous parties have an interest in peripheral vascular disease, and that many specialties order vascular laboratory tests.

A number of them were represented in the development of these appropriate use criteria. Collaborating organizations included the American College of Radiology, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nephrology, Intersocietal Accreditation Commission, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Interventional Radiology, the Society for Vascular Medicine, and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

While other organizations have developed appropriate use criteria for other modalities, such as cardiac testing, few have specifically addressed vascular testing.

"I hope that these criteria will allow clinicians and vascular laboratories to really focus on doing the highest quality work, and to evaluate their use of vascular testing, maximize the use of the vascular lab, and assure that the right test is done for the right indication and that tests that are not needed are not performed just because they are readily available," she said.

Dr. Gornik disclosed financial or other relationships with Zin Medical, Summit Doppler Systems Inc., the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America, and the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. A detailed list of disclosures for all Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force Members is included with the full text of the report.

Venous duplex ultrasound is rarely appropriate as a screening tool for upper or lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in the absence of pain or swelling, according to new appropriate use criteria for noninvasive vascular laboratory testing issued by the American College of Cardiology.

The clinical scenarios involving venous duplex ultrasound for DVT screening that were deemed rarely appropriate – such as screening in those with a prolonged ICU stay and those with high DVT risk – represent just a few of the 116 scenarios included in the report, which was developed in collaboration with 10 other leading professional societies to promote the most effective and most efficient use of peripheral vascular ultrasound and physiological testing in clinical practice.

The report, published online on July 19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the second in a two-part series evaluating noninvasive testing for peripheral vascular disorders. Part I, published last year (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:242-76), addressed peripheral arterial disorders, and Part II (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 July 19 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.001]) addresses venous disease and evaluation of hemodialysis access, according to Dr. Heather Gornik, chair of the Part II writing committee.

"Vascular laboratory tests really play a central role in evaluating patients with peripheral vascular disorders. They are noninvasive, they have good accuracy data, and they don’t require radiation or dye. But we want to make sure the right tests are being ordered for the right reasons," Dr. Gornik, a cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

Because these tests are low risk and easily accessible, there is concern that they are sometimes used excessively, she explained – specifically mentioning the use of duplex ultrasound for DVT screening as a commonly overused procedure.

"There is very little evidence, if any, to support broad screening for blood clots in someone who has no symptoms," she said.

The goal of the ACC Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force responsible for developing the criteria was to help clinicians minimize unnecessary testing, and maximize the most effective and efficient testing, she added.

Each of the clinical scenarios that were developed by the writing committee were rated by a technical panel as to whether they represent an "appropriate use," or whether they are "maybe appropriate" or "rarely appropriate."

The various scenarios are listed, along with their rating, in eight "at-a-glance" tables that address the following more general categories: venous duplex of the upper extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; venous duplex of the lower extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; duplex evaluation for venous incompetency; venous physiological testing with provocative maneuvers to assess for patency and/or incompetency; duplex of the inferior vena cava and iliac veins for patency and thrombosis; duplex of the hepatoportal system for patency, thrombosis, and flow direction; duplex of the renal vein for patency and thrombosis; and preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of a vascular access site.

Considering venous duplex ultrasound in a patient with acute unilateral limb swelling? Table 1 lists this as an appropriate use. How about duplex evaluation for venous incompetency in a patient with asymptomatic varicose veins? Table 3 says this may be appropriate, but notes that it is rarely appropriate in a patient with spider veins.

The report also covers indications for vascular testing prior to or after placement of hemodialysis access, because "evaluation of the superficial, deep, and central veins of the upper extremity constitutes a large component of these examinations," the report states.

In general, vascular studies were deemed appropriate in the presence of clinical signs and symptoms. The report also shows that the vascular laboratory plays a central role in the evaluation of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, and that preoperative vascular testing for preparing a dialysis access site is appropriate within three months of the procedure – but not for general surveillance of a functional dialysis fistula or graft in the absence of an indication of a problem, such as a palpable mass or swelling in the arm.

The report is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather is an attempt to address common and important clinical scenarios encountered in the patient with manifestations of peripheral vascular disease, the authors noted.

"The beauty of this report is that it spans many disciplines," Dr. Gornik said, noting that numerous parties have an interest in peripheral vascular disease, and that many specialties order vascular laboratory tests.

A number of them were represented in the development of these appropriate use criteria. Collaborating organizations included the American College of Radiology, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nephrology, Intersocietal Accreditation Commission, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Interventional Radiology, the Society for Vascular Medicine, and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

While other organizations have developed appropriate use criteria for other modalities, such as cardiac testing, few have specifically addressed vascular testing.

"I hope that these criteria will allow clinicians and vascular laboratories to really focus on doing the highest quality work, and to evaluate their use of vascular testing, maximize the use of the vascular lab, and assure that the right test is done for the right indication and that tests that are not needed are not performed just because they are readily available," she said.

Dr. Gornik disclosed financial or other relationships with Zin Medical, Summit Doppler Systems Inc., the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America, and the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. A detailed list of disclosures for all Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force Members is included with the full text of the report.

Venous duplex ultrasound is rarely appropriate as a screening tool for upper or lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in the absence of pain or swelling, according to new appropriate use criteria for noninvasive vascular laboratory testing issued by the American College of Cardiology.

The clinical scenarios involving venous duplex ultrasound for DVT screening that were deemed rarely appropriate – such as screening in those with a prolonged ICU stay and those with high DVT risk – represent just a few of the 116 scenarios included in the report, which was developed in collaboration with 10 other leading professional societies to promote the most effective and most efficient use of peripheral vascular ultrasound and physiological testing in clinical practice.

The report, published online on July 19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the second in a two-part series evaluating noninvasive testing for peripheral vascular disorders. Part I, published last year (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:242-76), addressed peripheral arterial disorders, and Part II (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 July 19 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.001]) addresses venous disease and evaluation of hemodialysis access, according to Dr. Heather Gornik, chair of the Part II writing committee.

"Vascular laboratory tests really play a central role in evaluating patients with peripheral vascular disorders. They are noninvasive, they have good accuracy data, and they don’t require radiation or dye. But we want to make sure the right tests are being ordered for the right reasons," Dr. Gornik, a cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

Because these tests are low risk and easily accessible, there is concern that they are sometimes used excessively, she explained – specifically mentioning the use of duplex ultrasound for DVT screening as a commonly overused procedure.

"There is very little evidence, if any, to support broad screening for blood clots in someone who has no symptoms," she said.

The goal of the ACC Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force responsible for developing the criteria was to help clinicians minimize unnecessary testing, and maximize the most effective and efficient testing, she added.

Each of the clinical scenarios that were developed by the writing committee were rated by a technical panel as to whether they represent an "appropriate use," or whether they are "maybe appropriate" or "rarely appropriate."

The various scenarios are listed, along with their rating, in eight "at-a-glance" tables that address the following more general categories: venous duplex of the upper extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; venous duplex of the lower extremities for assessing patency and thrombosis; duplex evaluation for venous incompetency; venous physiological testing with provocative maneuvers to assess for patency and/or incompetency; duplex of the inferior vena cava and iliac veins for patency and thrombosis; duplex of the hepatoportal system for patency, thrombosis, and flow direction; duplex of the renal vein for patency and thrombosis; and preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of a vascular access site.

Considering venous duplex ultrasound in a patient with acute unilateral limb swelling? Table 1 lists this as an appropriate use. How about duplex evaluation for venous incompetency in a patient with asymptomatic varicose veins? Table 3 says this may be appropriate, but notes that it is rarely appropriate in a patient with spider veins.

The report also covers indications for vascular testing prior to or after placement of hemodialysis access, because "evaluation of the superficial, deep, and central veins of the upper extremity constitutes a large component of these examinations," the report states.

In general, vascular studies were deemed appropriate in the presence of clinical signs and symptoms. The report also shows that the vascular laboratory plays a central role in the evaluation of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, and that preoperative vascular testing for preparing a dialysis access site is appropriate within three months of the procedure – but not for general surveillance of a functional dialysis fistula or graft in the absence of an indication of a problem, such as a palpable mass or swelling in the arm.

The report is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather is an attempt to address common and important clinical scenarios encountered in the patient with manifestations of peripheral vascular disease, the authors noted.

"The beauty of this report is that it spans many disciplines," Dr. Gornik said, noting that numerous parties have an interest in peripheral vascular disease, and that many specialties order vascular laboratory tests.

A number of them were represented in the development of these appropriate use criteria. Collaborating organizations included the American College of Radiology, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nephrology, Intersocietal Accreditation Commission, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Interventional Radiology, the Society for Vascular Medicine, and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

While other organizations have developed appropriate use criteria for other modalities, such as cardiac testing, few have specifically addressed vascular testing.

"I hope that these criteria will allow clinicians and vascular laboratories to really focus on doing the highest quality work, and to evaluate their use of vascular testing, maximize the use of the vascular lab, and assure that the right test is done for the right indication and that tests that are not needed are not performed just because they are readily available," she said.

Dr. Gornik disclosed financial or other relationships with Zin Medical, Summit Doppler Systems Inc., the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America, and the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. A detailed list of disclosures for all Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force Members is included with the full text of the report.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Androgen deprivation therapy linked to acute kidney injury

Androgen deprivation therapy was strongly associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury among men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer, according to a report in the July 17 issue of JAMA.

This elevation in risk varied slightly among different types of androgen deprivation agents, and was strongest with therapies that combine gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists with oral antiandrogens. That suggests "a possible additive effect ... on both receptor antagonism and reduction of testosterone excretion," said Francesco Lapi, Pharm.D., Ph.D., of the Centre for Clinical Epidemiology, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, and his associates (JAMA 2013;310:289-96).

The researchers discovered the risk elevation in what they described as the first population-based study to investigate the association between androgen deprivation therapy and acute kidney injury. They performed the study because even though the treatment traditionally has been reserved for advanced disease, it is now used increasingly in patients with earlier stages of prostate cancer.