User login

Mobile stroke teams treat patients faster and reduce disability

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

FROM STROKE

COVID-19 tied to acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease pathology

, a new study shows.

These results suggest that COVID-19 may accelerate Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology, said study investigator Thomas Wisniewski, MD, professor of neurology, pathology, and psychiatry at New York University.

The findings were presented here at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2021.

Strong correlation

There’s a clear association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease are at threefold higher risk for the infection and have a twofold higher risk for death, Dr. Wisniewski told meeting delegates.

He and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of patients who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who experienced neurologic sequelae and SARS-CoV-2 patients who were without neurologic sequelae. All patients were hospitalized from March 10 to May 20, 2020. This was during a period when New York City was overwhelmed by COVID: About 35% of hospitalized patients had COVID.

Of those who experienced neurologic events, the most common “by far and away” (51%) was toxic metabolic encephalopathy (TME), said Dr. Wisniewski. Other associations included seizures, hypoxic/anoxic injury, and ischemic stroke.

The most common TMEs were septic and hypoxic ischemia. In most patients (78%), TME had more than one cause.

Researchers followed 196 patients with COVID and neurologic complications (case patients) and 186 matched control patients who had no neurologic complications over a period of 6 months.

“Unfortunately, both groups had poor outcomes,” said Dr. Wisniewski. About 50% had impaired cognition, and 56% experienced limitations in activities of daily living.

However, those patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic sequelae “fared even worse,” said Dr. Wisniewski. Compared with control patients, they had twofold worse Modified Rankin Scale scores and worse scores on activity of daily living, and they were much less likely to return to work.

Mechanisms by which COVID-19 affects longer-term cognitive dysfunction are unclear, but inflammation likely plays a role.

The research team compared a number of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers in 158 patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic symptoms and 152 COVID patients with COVID but no neurologic symptoms. They found marked elevations of neurofilament light, a marker of neuronal injury, in those with symptoms (P = .0003) as well as increased glial fibrillary acid protein, a marker of neuroinflammation (P = .0098).

Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1, another marker of neuronal injury, was also elevated in those with neurologic symptoms. Regarding Alzheimer’s disease pathology, total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau “also tracked with neurological sequelae,” said Dr. Wisniewski.

There was no difference in levels of amyloid beta 40 (A beta 40) between groups. However, A beta 42 plasma levels were significantly lower in those with neurologic effects, suggesting higher levels in the brain. In addition, the ratio of t-tau to A beta 42 “clearly differentiated the two groups,” he said.

“Serum biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neuronal injury and Alzheimer’s disease correlate strongly, perhaps suggesting that folks with COVID infection and neurological sequelae may have an acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology,” he said. “That’s something that needs longer follow-up.”

Important differentiation

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said the study provides important information. The inclusion of plasma biomarkers in this research is “really critical to tease out what’s the impact of COVID itself on the brain,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

“We’re in an era of biomarkers when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and being able to define those changes that are happening in the brain over time is going to be really critical and aid in early detection and accurate diagnoses,” she said.

What is still to be learned is what these biomarkers reveal long term, said Dr. Edelmayer. “Do those biological markers change? Do they go back to normal? A lot of that is still unknown,” she said.

She noted that many diseases that are linked to inflammation produce similar biomarkers in the brain – for example, neurofilament light.

With other viral infections, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), similar associations between the infection and cognition have been reported, said Dr. Edelmayer.

“But there are still a lot of questions around cause and effect. Is it really a direct effect of the virus on the brain itself? Is it an effect of having an enormous amount of inflammation going on in the body? A lot of that still needs to be teased out,” she commented.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the State of New York. Dr. Wisniewski has consulted for Grifols, Amylon Pharmaceuticals, and Alzamed Neuro; 30 NYU patents are related to AD therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

These results suggest that COVID-19 may accelerate Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology, said study investigator Thomas Wisniewski, MD, professor of neurology, pathology, and psychiatry at New York University.

The findings were presented here at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2021.

Strong correlation

There’s a clear association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease are at threefold higher risk for the infection and have a twofold higher risk for death, Dr. Wisniewski told meeting delegates.

He and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of patients who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who experienced neurologic sequelae and SARS-CoV-2 patients who were without neurologic sequelae. All patients were hospitalized from March 10 to May 20, 2020. This was during a period when New York City was overwhelmed by COVID: About 35% of hospitalized patients had COVID.

Of those who experienced neurologic events, the most common “by far and away” (51%) was toxic metabolic encephalopathy (TME), said Dr. Wisniewski. Other associations included seizures, hypoxic/anoxic injury, and ischemic stroke.

The most common TMEs were septic and hypoxic ischemia. In most patients (78%), TME had more than one cause.

Researchers followed 196 patients with COVID and neurologic complications (case patients) and 186 matched control patients who had no neurologic complications over a period of 6 months.

“Unfortunately, both groups had poor outcomes,” said Dr. Wisniewski. About 50% had impaired cognition, and 56% experienced limitations in activities of daily living.

However, those patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic sequelae “fared even worse,” said Dr. Wisniewski. Compared with control patients, they had twofold worse Modified Rankin Scale scores and worse scores on activity of daily living, and they were much less likely to return to work.

Mechanisms by which COVID-19 affects longer-term cognitive dysfunction are unclear, but inflammation likely plays a role.

The research team compared a number of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers in 158 patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic symptoms and 152 COVID patients with COVID but no neurologic symptoms. They found marked elevations of neurofilament light, a marker of neuronal injury, in those with symptoms (P = .0003) as well as increased glial fibrillary acid protein, a marker of neuroinflammation (P = .0098).

Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1, another marker of neuronal injury, was also elevated in those with neurologic symptoms. Regarding Alzheimer’s disease pathology, total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau “also tracked with neurological sequelae,” said Dr. Wisniewski.

There was no difference in levels of amyloid beta 40 (A beta 40) between groups. However, A beta 42 plasma levels were significantly lower in those with neurologic effects, suggesting higher levels in the brain. In addition, the ratio of t-tau to A beta 42 “clearly differentiated the two groups,” he said.

“Serum biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neuronal injury and Alzheimer’s disease correlate strongly, perhaps suggesting that folks with COVID infection and neurological sequelae may have an acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology,” he said. “That’s something that needs longer follow-up.”

Important differentiation

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said the study provides important information. The inclusion of plasma biomarkers in this research is “really critical to tease out what’s the impact of COVID itself on the brain,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

“We’re in an era of biomarkers when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and being able to define those changes that are happening in the brain over time is going to be really critical and aid in early detection and accurate diagnoses,” she said.

What is still to be learned is what these biomarkers reveal long term, said Dr. Edelmayer. “Do those biological markers change? Do they go back to normal? A lot of that is still unknown,” she said.

She noted that many diseases that are linked to inflammation produce similar biomarkers in the brain – for example, neurofilament light.

With other viral infections, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), similar associations between the infection and cognition have been reported, said Dr. Edelmayer.

“But there are still a lot of questions around cause and effect. Is it really a direct effect of the virus on the brain itself? Is it an effect of having an enormous amount of inflammation going on in the body? A lot of that still needs to be teased out,” she commented.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the State of New York. Dr. Wisniewski has consulted for Grifols, Amylon Pharmaceuticals, and Alzamed Neuro; 30 NYU patents are related to AD therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

These results suggest that COVID-19 may accelerate Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology, said study investigator Thomas Wisniewski, MD, professor of neurology, pathology, and psychiatry at New York University.

The findings were presented here at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2021.

Strong correlation

There’s a clear association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease are at threefold higher risk for the infection and have a twofold higher risk for death, Dr. Wisniewski told meeting delegates.

He and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of patients who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who experienced neurologic sequelae and SARS-CoV-2 patients who were without neurologic sequelae. All patients were hospitalized from March 10 to May 20, 2020. This was during a period when New York City was overwhelmed by COVID: About 35% of hospitalized patients had COVID.

Of those who experienced neurologic events, the most common “by far and away” (51%) was toxic metabolic encephalopathy (TME), said Dr. Wisniewski. Other associations included seizures, hypoxic/anoxic injury, and ischemic stroke.

The most common TMEs were septic and hypoxic ischemia. In most patients (78%), TME had more than one cause.

Researchers followed 196 patients with COVID and neurologic complications (case patients) and 186 matched control patients who had no neurologic complications over a period of 6 months.

“Unfortunately, both groups had poor outcomes,” said Dr. Wisniewski. About 50% had impaired cognition, and 56% experienced limitations in activities of daily living.

However, those patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic sequelae “fared even worse,” said Dr. Wisniewski. Compared with control patients, they had twofold worse Modified Rankin Scale scores and worse scores on activity of daily living, and they were much less likely to return to work.

Mechanisms by which COVID-19 affects longer-term cognitive dysfunction are unclear, but inflammation likely plays a role.

The research team compared a number of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers in 158 patients with COVID-19 who had neurologic symptoms and 152 COVID patients with COVID but no neurologic symptoms. They found marked elevations of neurofilament light, a marker of neuronal injury, in those with symptoms (P = .0003) as well as increased glial fibrillary acid protein, a marker of neuroinflammation (P = .0098).

Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1, another marker of neuronal injury, was also elevated in those with neurologic symptoms. Regarding Alzheimer’s disease pathology, total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau “also tracked with neurological sequelae,” said Dr. Wisniewski.

There was no difference in levels of amyloid beta 40 (A beta 40) between groups. However, A beta 42 plasma levels were significantly lower in those with neurologic effects, suggesting higher levels in the brain. In addition, the ratio of t-tau to A beta 42 “clearly differentiated the two groups,” he said.

“Serum biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neuronal injury and Alzheimer’s disease correlate strongly, perhaps suggesting that folks with COVID infection and neurological sequelae may have an acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease symptoms and pathology,” he said. “That’s something that needs longer follow-up.”

Important differentiation

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said the study provides important information. The inclusion of plasma biomarkers in this research is “really critical to tease out what’s the impact of COVID itself on the brain,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

“We’re in an era of biomarkers when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and being able to define those changes that are happening in the brain over time is going to be really critical and aid in early detection and accurate diagnoses,” she said.

What is still to be learned is what these biomarkers reveal long term, said Dr. Edelmayer. “Do those biological markers change? Do they go back to normal? A lot of that is still unknown,” she said.

She noted that many diseases that are linked to inflammation produce similar biomarkers in the brain – for example, neurofilament light.

With other viral infections, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), similar associations between the infection and cognition have been reported, said Dr. Edelmayer.

“But there are still a lot of questions around cause and effect. Is it really a direct effect of the virus on the brain itself? Is it an effect of having an enormous amount of inflammation going on in the body? A lot of that still needs to be teased out,” she commented.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the State of New York. Dr. Wisniewski has consulted for Grifols, Amylon Pharmaceuticals, and Alzamed Neuro; 30 NYU patents are related to AD therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2021

‘Alarming’ data on early cognitive decline in transgender adults

, new research shows.

Investigators found transgender adults – individuals who identify with a gender different than the one assigned to them at birth – were nearly twice as likely to report subjective cognitive decline and more than twice as likely to report SCD-related functional limitations – such as reduced ability to work, volunteer, or be social – than cisgender adults.

“Trans populations are disproportionately impacted by health disparities and also risk factors for dementia. Putting these pieces together, I wasn’t surprised by their greater risk of cognitive decline,” said study investigator Ethan Cicero, PhD, RN, an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

‘Alarming’ finding

SCD is a self-reported experience of worsening memory or thinking and is one of the first clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD). Yet there is limited research into cognitive impairment among transgender adults.

The researchers examined SCD and associated functional limitations among transgender and cisgender adults older than age 45 years who provided health and health behavior data as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys (2015-2019).

The sample included 386,529 adults of whom 1,302 identified as transgender and 385,227 as cisgender.

Roughly 17% of transgender adults reported SCD, which is significantly higher than the 10.6% rate for cisgender adults (P < .001).

Compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD, transgender adults reporting SCD were younger (mean age 61.9 vs. 65.2 years, P = .0005), more likely to be in a racial/ethnic minority group (37.3% vs. 19.5%, P < .0001), have a high school degree or less (59.6% vs. 43.4%, P = .0003), be uninsured (17% vs. 5.5%, P = .0007) and have a depressive disorder (58.8% vs. 45.7%, P = .0028).

The fact that transgender people who reported SCD were about 3 years younger than cisgender people who reported SCD is “somewhat alarming and a red flag to ask middle-aged trans adults about their brain health and not just older or elderly trans adults,” said Dr. Cicero.

The study also showed that transgender adults reporting SCD were 2.3 times more likely to report related social and self-care limitations when compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD.

The findings align with a study reported at AAIC 2019, which showed that sexual or gender minorities (SGM) are almost 30% more likely to report subjective cognitive decline compared with the non-SGM population.

Cause unclear

“We are not certain what may be causing the elevated subjective cognitive decline rates among transgender adults. We postulate that it may be in part due to anti-transgender stigma and prejudice that expose transgender people to high rates of mistreatment and discrimination where they live, work, learn, seek health care, and age,” Dr. Cicero said.

“More research is needed to identify and target preventive intervention strategies, develop culturally relevant screenings, and shape policies to improve the health and well-being of the transgender population,” he added.

Weighing in on the study, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “researchers have only just started to explore the experiences of dementia within the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community, but this is the first time we are seeing some specific research that’s looking at cognition in transgender individuals and gender nonbinary individuals.”

“We don’t know exactly why transgender and gender nonbinary individuals experience greater rates of subjective cognitive decline, but we do know that they have greater rates of health disparities that are considered risk factors for dementia, including higher rates of cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, tobacco and alcohol use, and obesity,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

“Alzheimer’s and dementia do not discriminate. Neither can we,” Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, chief science officer for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

“The Alzheimer’s Association advocates for more research to better understand the cognitive and emotional needs of transgender and nonbinary individuals so that our nation’s health care providers can offer them culturally sensitive care,” said Dr. Carrillo.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cicero, Dr. Carrillo, and Dr. Edelmayer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Investigators found transgender adults – individuals who identify with a gender different than the one assigned to them at birth – were nearly twice as likely to report subjective cognitive decline and more than twice as likely to report SCD-related functional limitations – such as reduced ability to work, volunteer, or be social – than cisgender adults.

“Trans populations are disproportionately impacted by health disparities and also risk factors for dementia. Putting these pieces together, I wasn’t surprised by their greater risk of cognitive decline,” said study investigator Ethan Cicero, PhD, RN, an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

‘Alarming’ finding

SCD is a self-reported experience of worsening memory or thinking and is one of the first clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD). Yet there is limited research into cognitive impairment among transgender adults.

The researchers examined SCD and associated functional limitations among transgender and cisgender adults older than age 45 years who provided health and health behavior data as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys (2015-2019).

The sample included 386,529 adults of whom 1,302 identified as transgender and 385,227 as cisgender.

Roughly 17% of transgender adults reported SCD, which is significantly higher than the 10.6% rate for cisgender adults (P < .001).

Compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD, transgender adults reporting SCD were younger (mean age 61.9 vs. 65.2 years, P = .0005), more likely to be in a racial/ethnic minority group (37.3% vs. 19.5%, P < .0001), have a high school degree or less (59.6% vs. 43.4%, P = .0003), be uninsured (17% vs. 5.5%, P = .0007) and have a depressive disorder (58.8% vs. 45.7%, P = .0028).

The fact that transgender people who reported SCD were about 3 years younger than cisgender people who reported SCD is “somewhat alarming and a red flag to ask middle-aged trans adults about their brain health and not just older or elderly trans adults,” said Dr. Cicero.

The study also showed that transgender adults reporting SCD were 2.3 times more likely to report related social and self-care limitations when compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD.

The findings align with a study reported at AAIC 2019, which showed that sexual or gender minorities (SGM) are almost 30% more likely to report subjective cognitive decline compared with the non-SGM population.

Cause unclear

“We are not certain what may be causing the elevated subjective cognitive decline rates among transgender adults. We postulate that it may be in part due to anti-transgender stigma and prejudice that expose transgender people to high rates of mistreatment and discrimination where they live, work, learn, seek health care, and age,” Dr. Cicero said.

“More research is needed to identify and target preventive intervention strategies, develop culturally relevant screenings, and shape policies to improve the health and well-being of the transgender population,” he added.

Weighing in on the study, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “researchers have only just started to explore the experiences of dementia within the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community, but this is the first time we are seeing some specific research that’s looking at cognition in transgender individuals and gender nonbinary individuals.”

“We don’t know exactly why transgender and gender nonbinary individuals experience greater rates of subjective cognitive decline, but we do know that they have greater rates of health disparities that are considered risk factors for dementia, including higher rates of cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, tobacco and alcohol use, and obesity,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

“Alzheimer’s and dementia do not discriminate. Neither can we,” Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, chief science officer for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

“The Alzheimer’s Association advocates for more research to better understand the cognitive and emotional needs of transgender and nonbinary individuals so that our nation’s health care providers can offer them culturally sensitive care,” said Dr. Carrillo.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cicero, Dr. Carrillo, and Dr. Edelmayer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Investigators found transgender adults – individuals who identify with a gender different than the one assigned to them at birth – were nearly twice as likely to report subjective cognitive decline and more than twice as likely to report SCD-related functional limitations – such as reduced ability to work, volunteer, or be social – than cisgender adults.

“Trans populations are disproportionately impacted by health disparities and also risk factors for dementia. Putting these pieces together, I wasn’t surprised by their greater risk of cognitive decline,” said study investigator Ethan Cicero, PhD, RN, an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

‘Alarming’ finding

SCD is a self-reported experience of worsening memory or thinking and is one of the first clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD). Yet there is limited research into cognitive impairment among transgender adults.

The researchers examined SCD and associated functional limitations among transgender and cisgender adults older than age 45 years who provided health and health behavior data as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys (2015-2019).

The sample included 386,529 adults of whom 1,302 identified as transgender and 385,227 as cisgender.

Roughly 17% of transgender adults reported SCD, which is significantly higher than the 10.6% rate for cisgender adults (P < .001).

Compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD, transgender adults reporting SCD were younger (mean age 61.9 vs. 65.2 years, P = .0005), more likely to be in a racial/ethnic minority group (37.3% vs. 19.5%, P < .0001), have a high school degree or less (59.6% vs. 43.4%, P = .0003), be uninsured (17% vs. 5.5%, P = .0007) and have a depressive disorder (58.8% vs. 45.7%, P = .0028).

The fact that transgender people who reported SCD were about 3 years younger than cisgender people who reported SCD is “somewhat alarming and a red flag to ask middle-aged trans adults about their brain health and not just older or elderly trans adults,” said Dr. Cicero.

The study also showed that transgender adults reporting SCD were 2.3 times more likely to report related social and self-care limitations when compared with cisgender adults reporting SCD.

The findings align with a study reported at AAIC 2019, which showed that sexual or gender minorities (SGM) are almost 30% more likely to report subjective cognitive decline compared with the non-SGM population.

Cause unclear

“We are not certain what may be causing the elevated subjective cognitive decline rates among transgender adults. We postulate that it may be in part due to anti-transgender stigma and prejudice that expose transgender people to high rates of mistreatment and discrimination where they live, work, learn, seek health care, and age,” Dr. Cicero said.

“More research is needed to identify and target preventive intervention strategies, develop culturally relevant screenings, and shape policies to improve the health and well-being of the transgender population,” he added.

Weighing in on the study, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “researchers have only just started to explore the experiences of dementia within the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community, but this is the first time we are seeing some specific research that’s looking at cognition in transgender individuals and gender nonbinary individuals.”

“We don’t know exactly why transgender and gender nonbinary individuals experience greater rates of subjective cognitive decline, but we do know that they have greater rates of health disparities that are considered risk factors for dementia, including higher rates of cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, tobacco and alcohol use, and obesity,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

“Alzheimer’s and dementia do not discriminate. Neither can we,” Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, chief science officer for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

“The Alzheimer’s Association advocates for more research to better understand the cognitive and emotional needs of transgender and nonbinary individuals so that our nation’s health care providers can offer them culturally sensitive care,” said Dr. Carrillo.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cicero, Dr. Carrillo, and Dr. Edelmayer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2021

Low-dose aspirin linked to lower dementia risk in some

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2021

Needed: More studies of CSF molecular biomarkers in psychiatric disorders

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

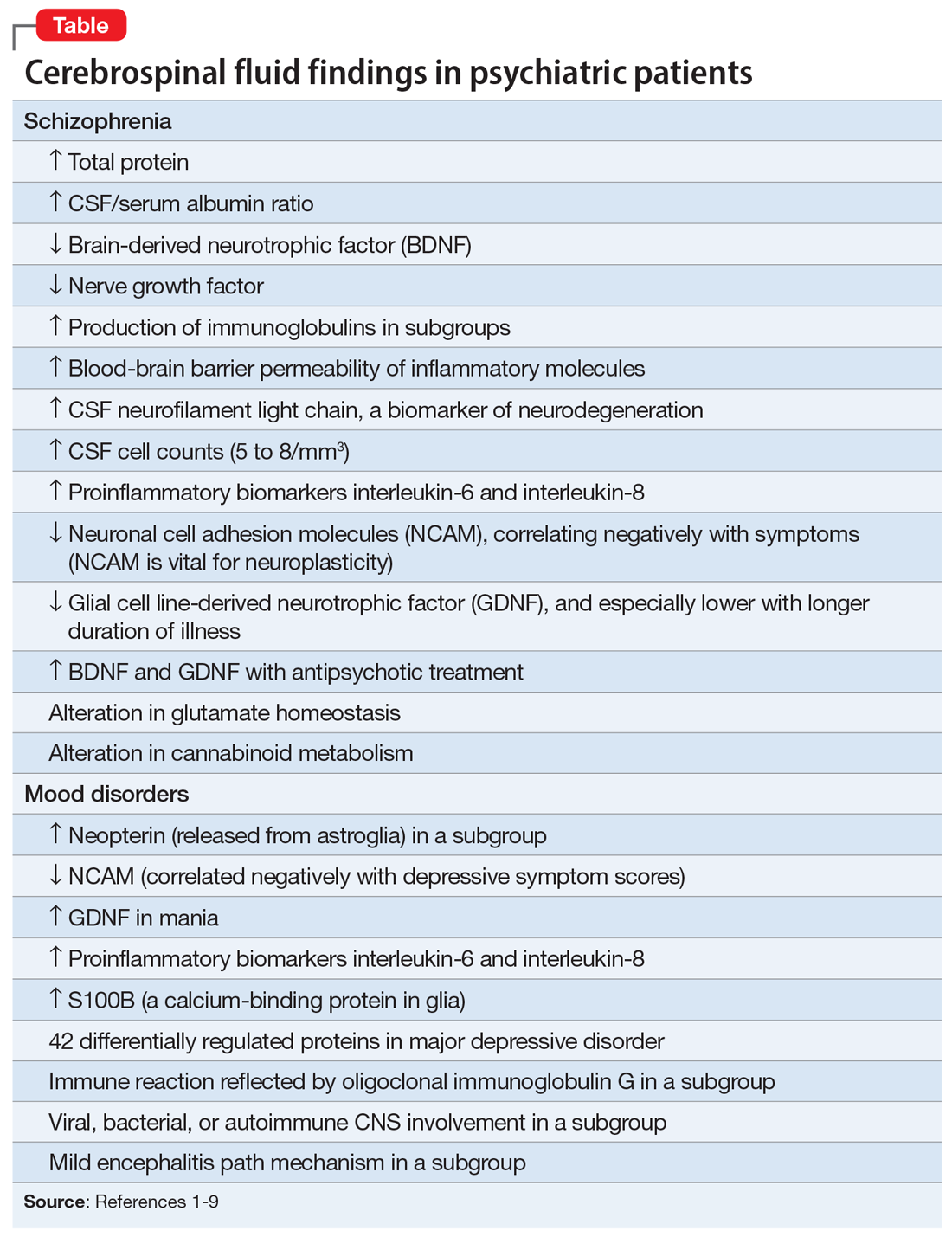

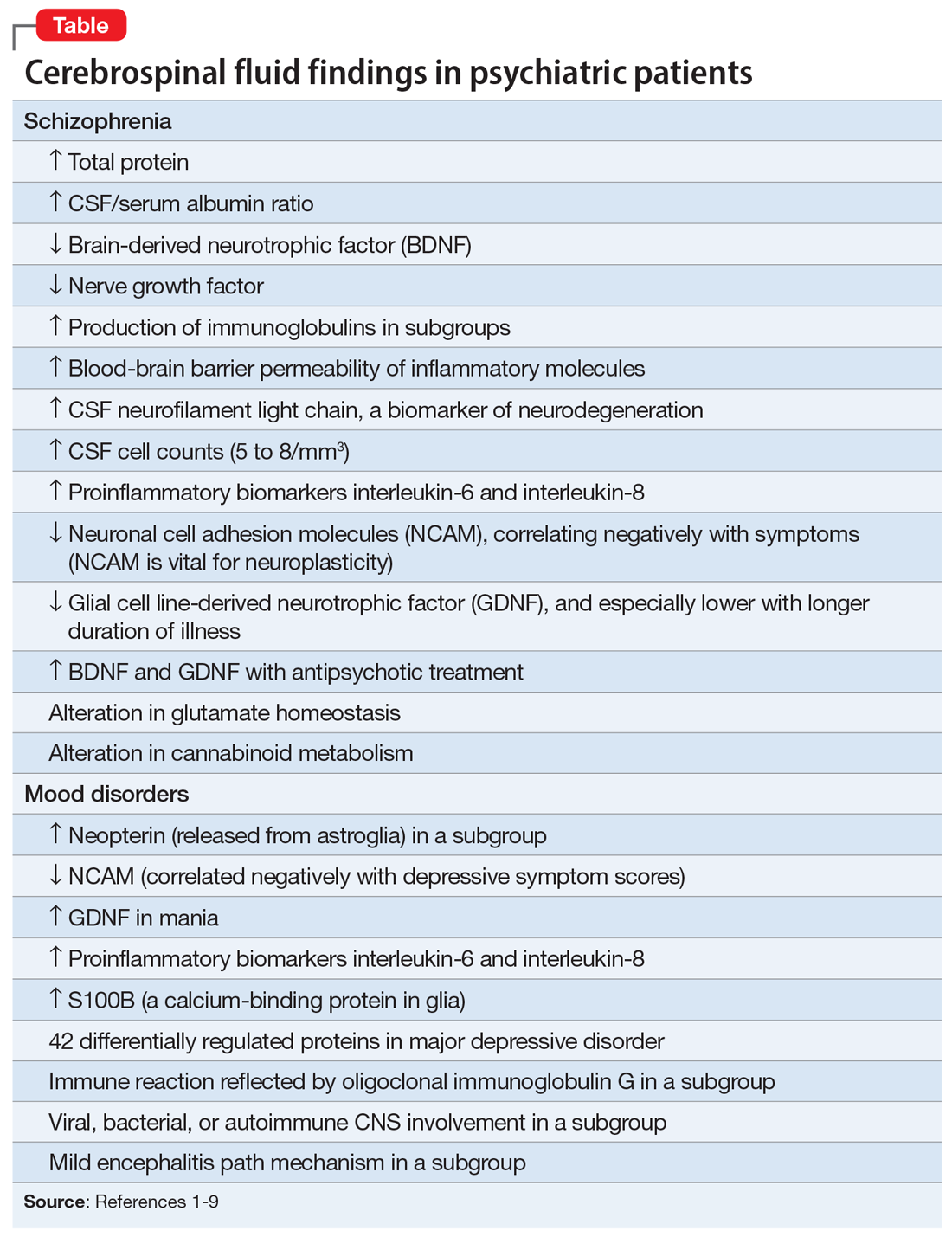

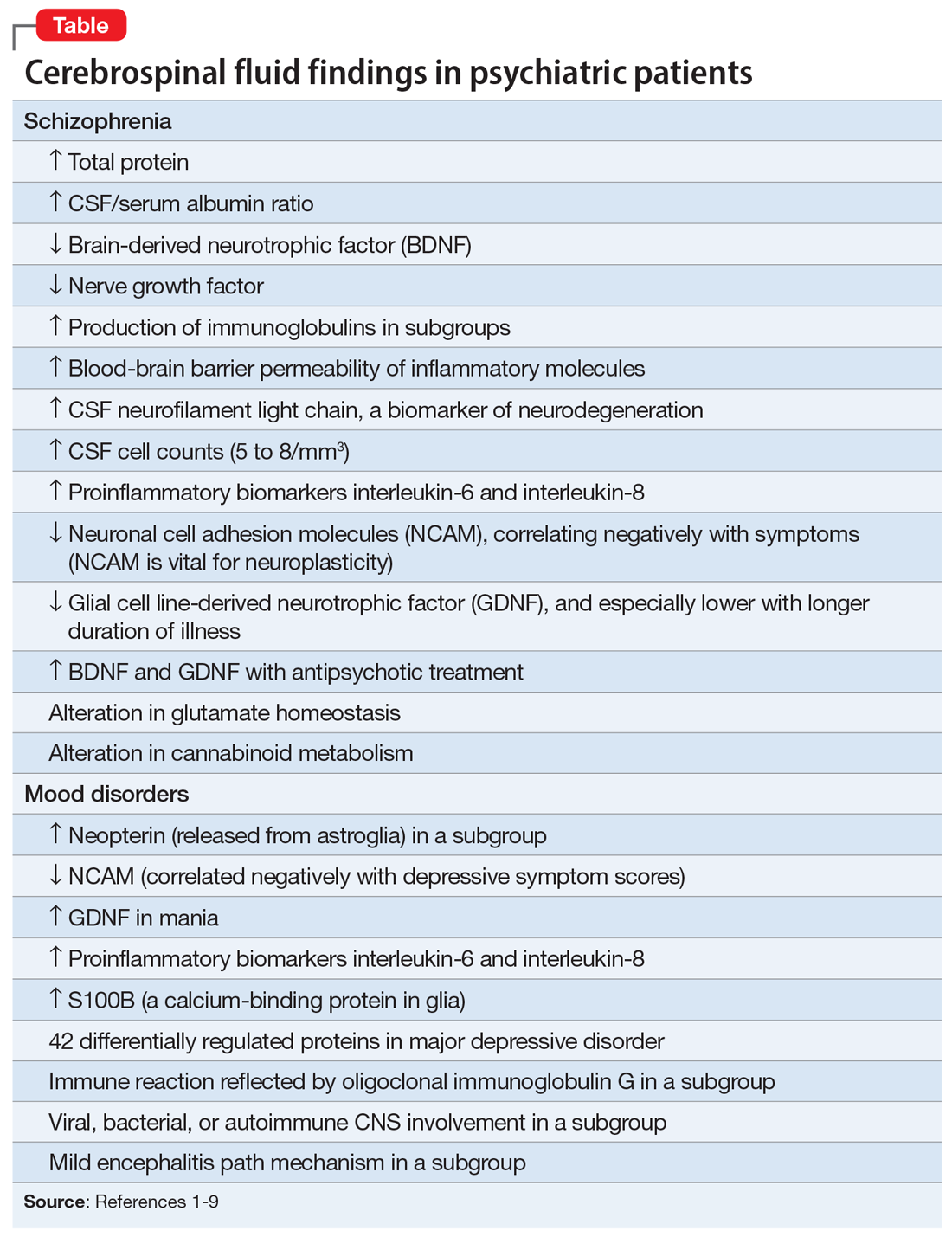

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Short sleep is linked to future dementia

, according to a new analysis of data from the Whitehall II cohort study.

Previous work had identified links between short sleep duration and dementia risk, but few studies examined sleep habits long before onset of dementia. Those that did produced inconsistent results, according to Séverine Sabia, PhD, who is a research associate at Inserm (France) and the University College London.

“One potential reason for these inconstancies is the large range of ages of the study populations, and the small number of participants within each sleep duration group. The novelty of our study is to examine this association among almost 8,000 participants with a follow-up of 30 years, using repeated measures of sleep duration starting in midlife to consider sleep duration at specific ages,” Dr. Sabia said in an interview. She presented the research at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Those previous studies found a U-shaped association between sleep duration and dementia risk, with lowest risk associated with 7-8 hours of sleep, but greater risk for shorter and longer durations. However, because the studies had follow-up periods shorter than 10 years, they are at greater risk of reverse causation bias. Longer follow-up studies tended to have small sample sizes or to focus on older adults.

The longer follow-up in the current study makes for a more compelling case, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of Scientific Programs & Outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association. Observations of short or long sleep closer to the onset of symptoms could just be a warning sign of dementia. “But looking at age 50, age 60 ... if you’re seeing those relationships, then it’s less likely that it is just purely prodromal,” said Dr. Sexton. But it still doesn’t necessarily confirm causation. “It could also be a risk factor,” Dr. Sexton added.

Multifactorial risk

Dr. Sabia also noted that the magnitude of risk was similar to that seen with smoking or obesity, and many factors play a role in dementia risk. “Even if the risk of dementia was 30% higher in those with persistent short sleep duration, in absolute terms, the percentage of those with persistent short duration who developed dementia was 8%, and 6% in those with persistent sleep duration of 7 hours. Dementia is a multifactorial disease, which means that several factors are likely to influence its onset. Sleep duration is one of them, but if a person has poor sleep and does not manage to increase it, there are other important prevention measures. It is important to keep a healthy lifestyle and cardiometabolic measures in the normal range. All together it is likely to be beneficial for brain health in later life,” she said.

Dr. Sexton agreed. “With sleep we’re still trying to tease apart what aspect of sleep is important. Is it the sleep duration? Is it the quality of sleep? Is it certain sleep stages?” she said.

Regardless of sleep’s potential influence on dementia risk, both Dr. Sexton and Dr. Sabia noted the importance of sleep for general health. “These types of problems are very prevalent, so it’s good for people to be aware of them. And then if they notice any problems with their sleep, or any changes, to go and see their health care provider, and to be discussing them, and then to be investigating the cause, and to see whether changes in sleep hygiene and treatments for insomnia could address these sleep problems,” said Dr. Sexton.

Decades of data

During the Whitehall II study, researchers assessed average sleep duration (“How many hours of sleep do you have on an average weeknight?”) six times over 30 years of follow-up. Dr. Sabia’s group extracted self-reported sleep duration data at ages 50, 60, and 70. Short sleep duration was defined as fewer than 5 hours, or 6 hours. Normal sleep duration was defined as 7 hours. Long duration was defined as 8 hours or more.

A questioner during the Q&A period noted that this grouping is a little unusual. Many studies define 7-8 hours as normal. Dr. Sabia answered that they were unable to examine periods of 9 hours or more due to the nature of the data, and the lowest associated risk was found at 7 hours.