User login

Factors that change our brains; The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Stigma in dementia: It’s time to talk about it

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

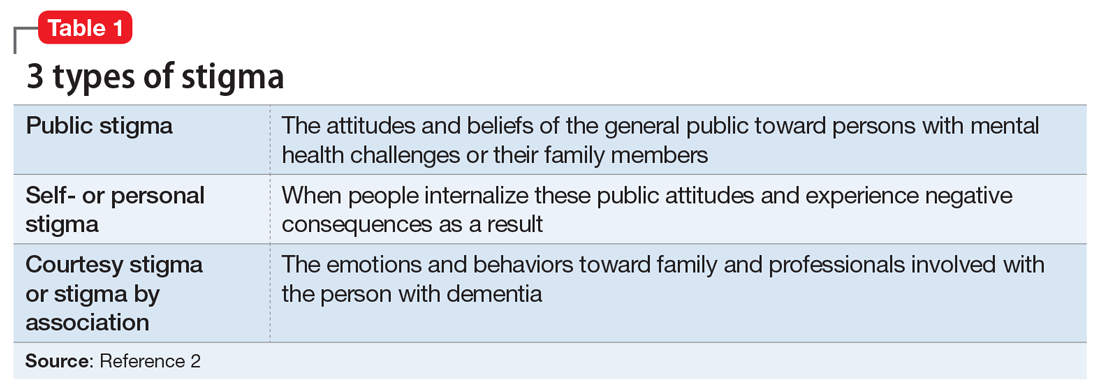

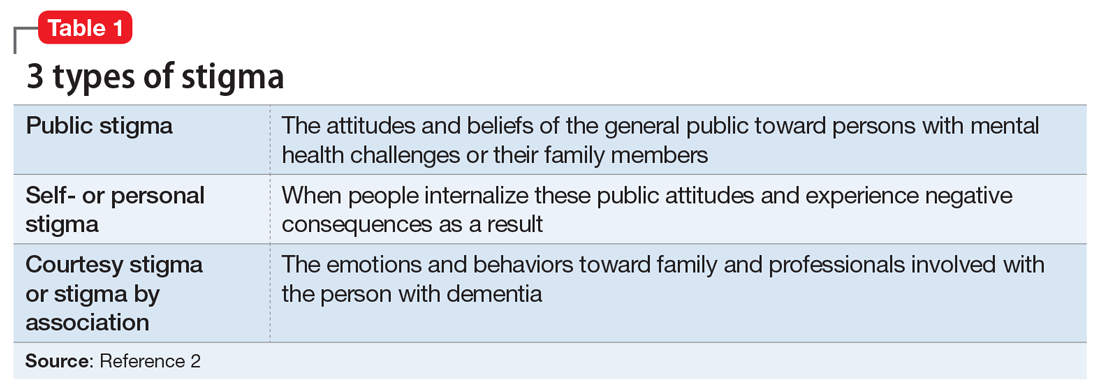

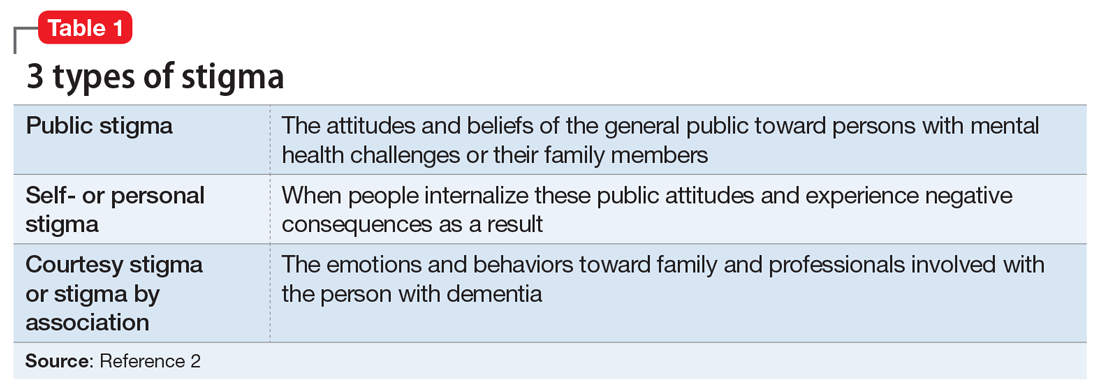

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

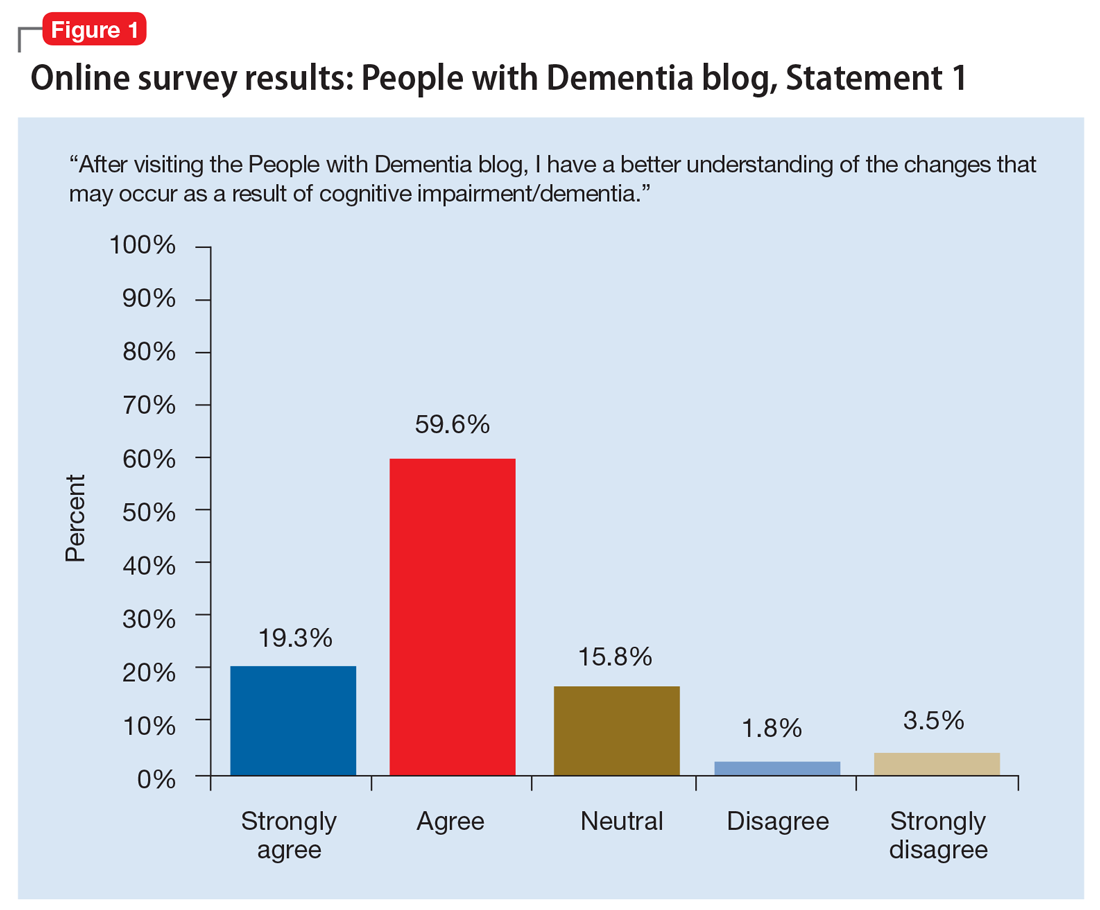

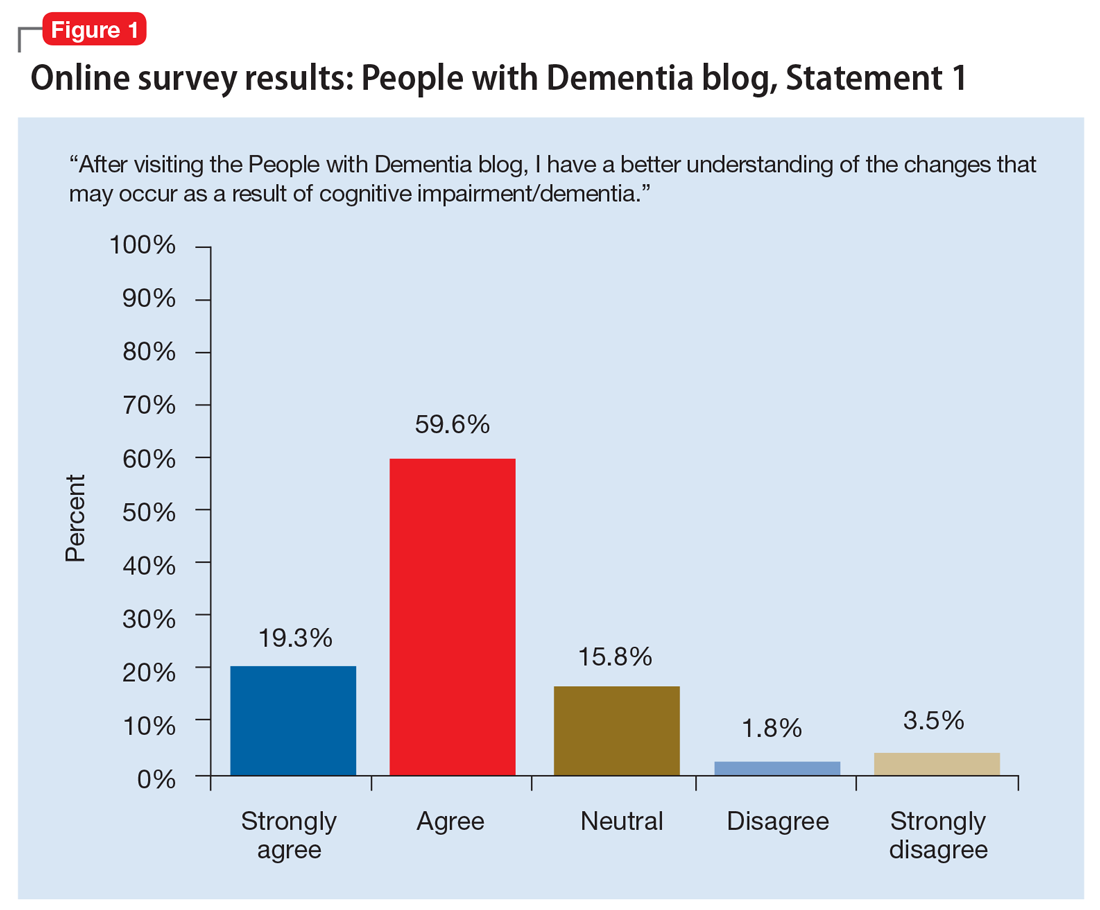

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

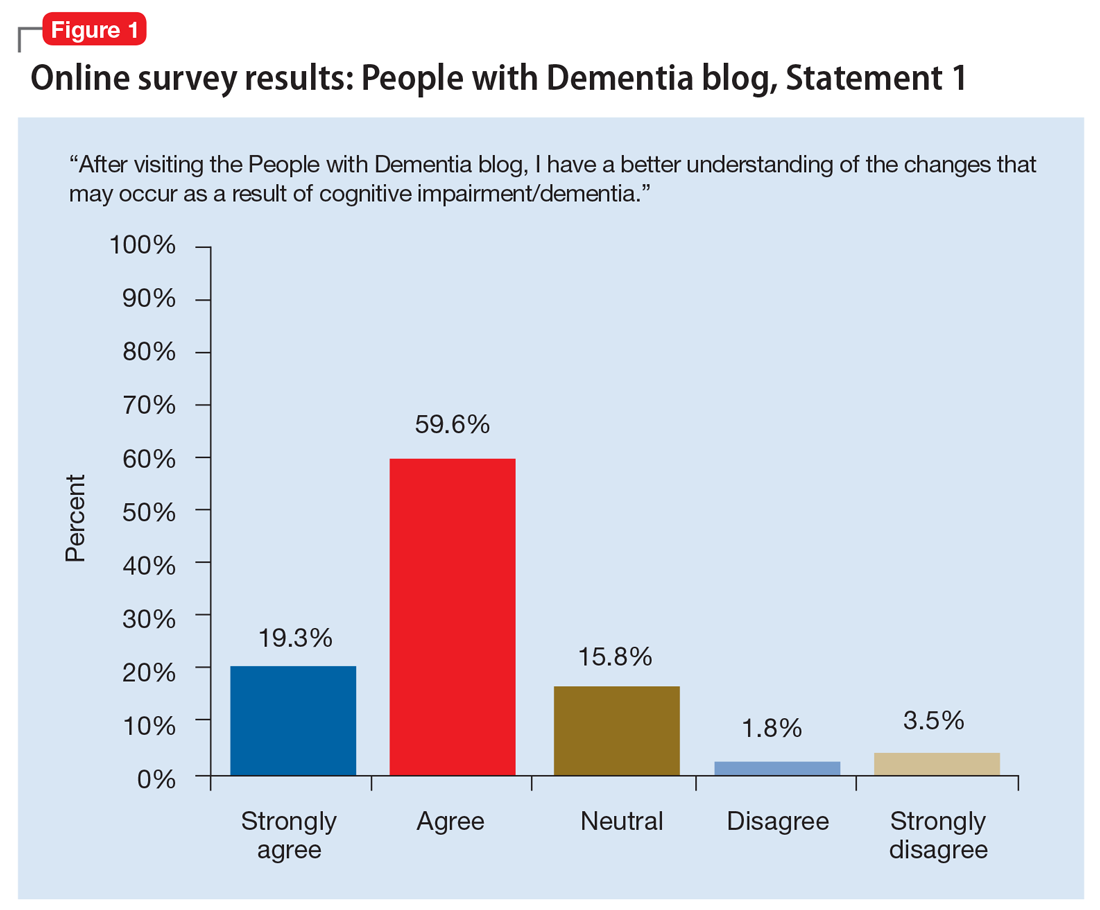

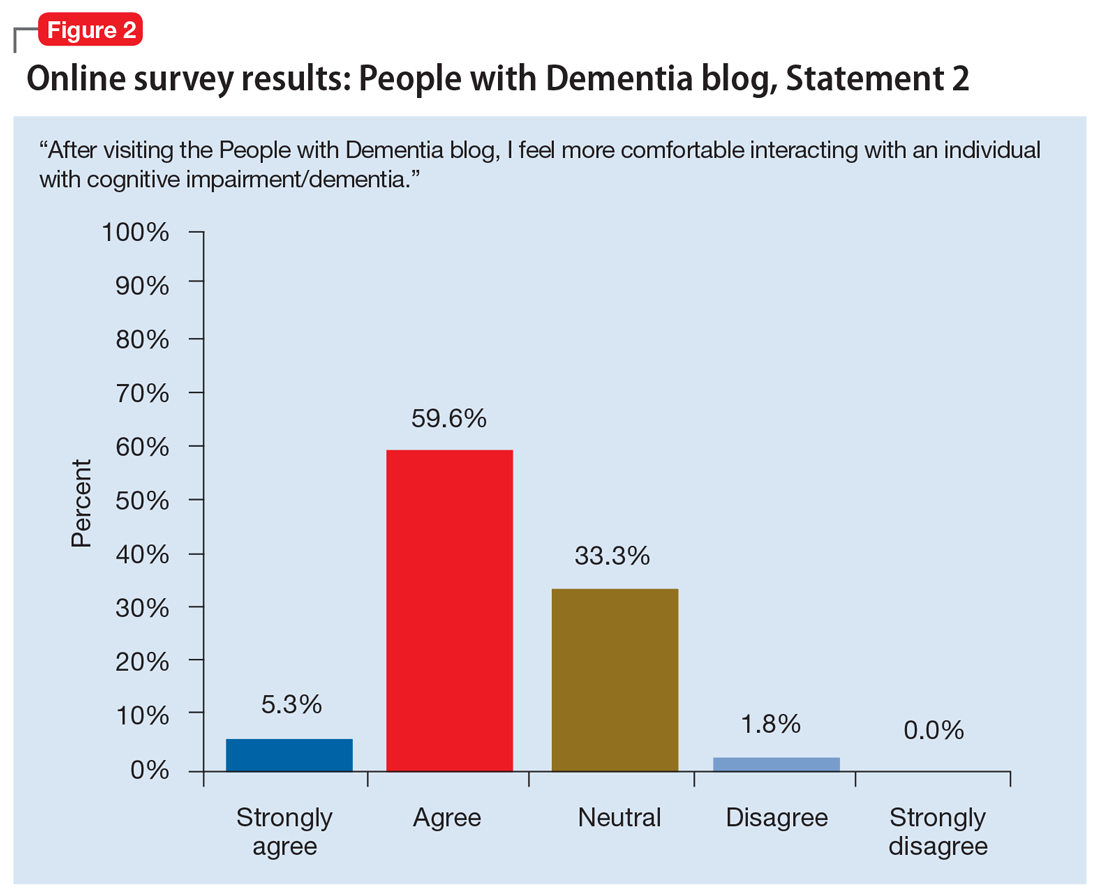

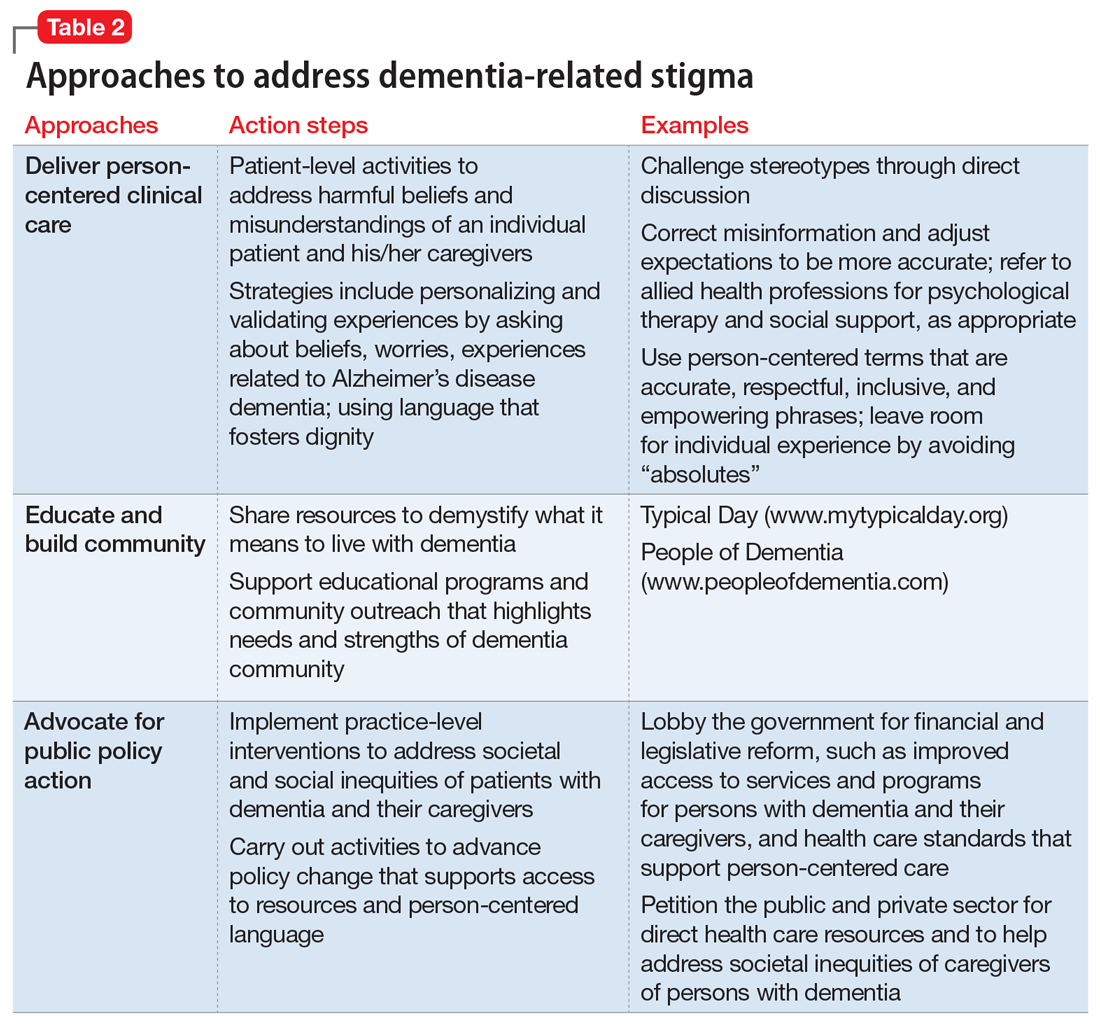

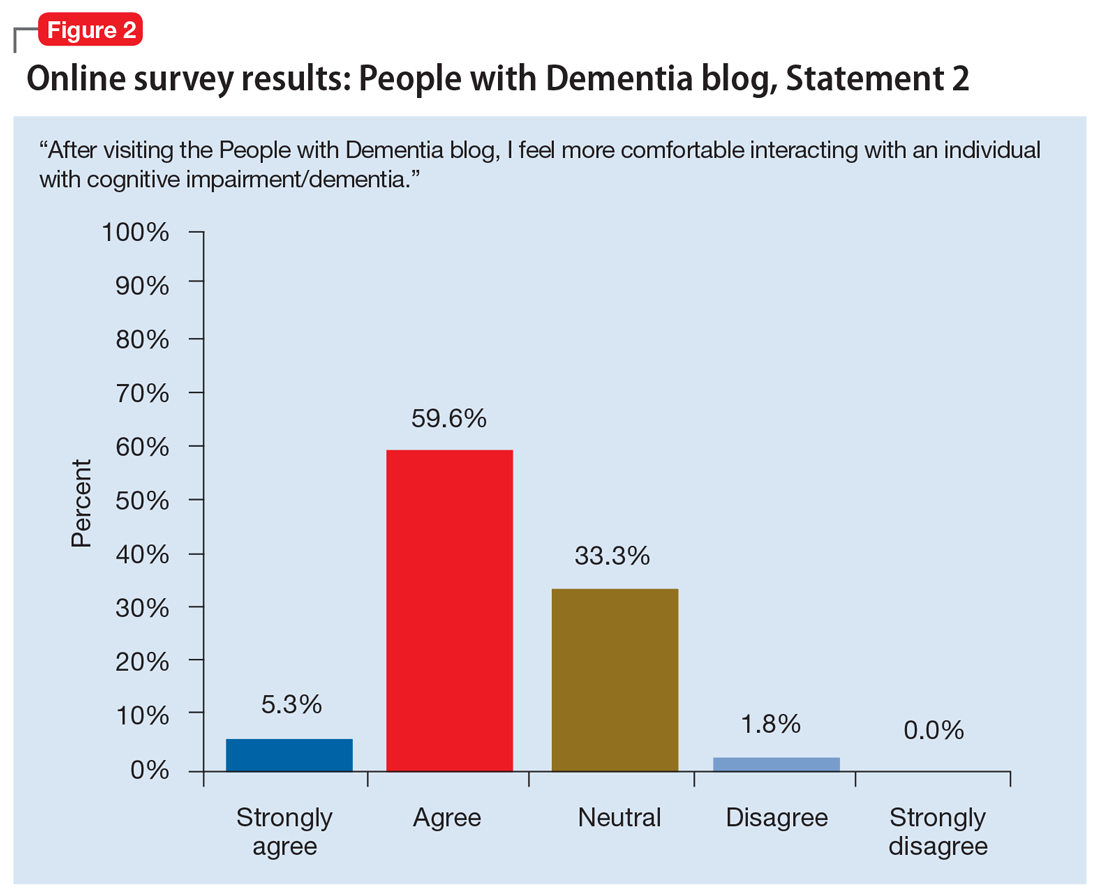

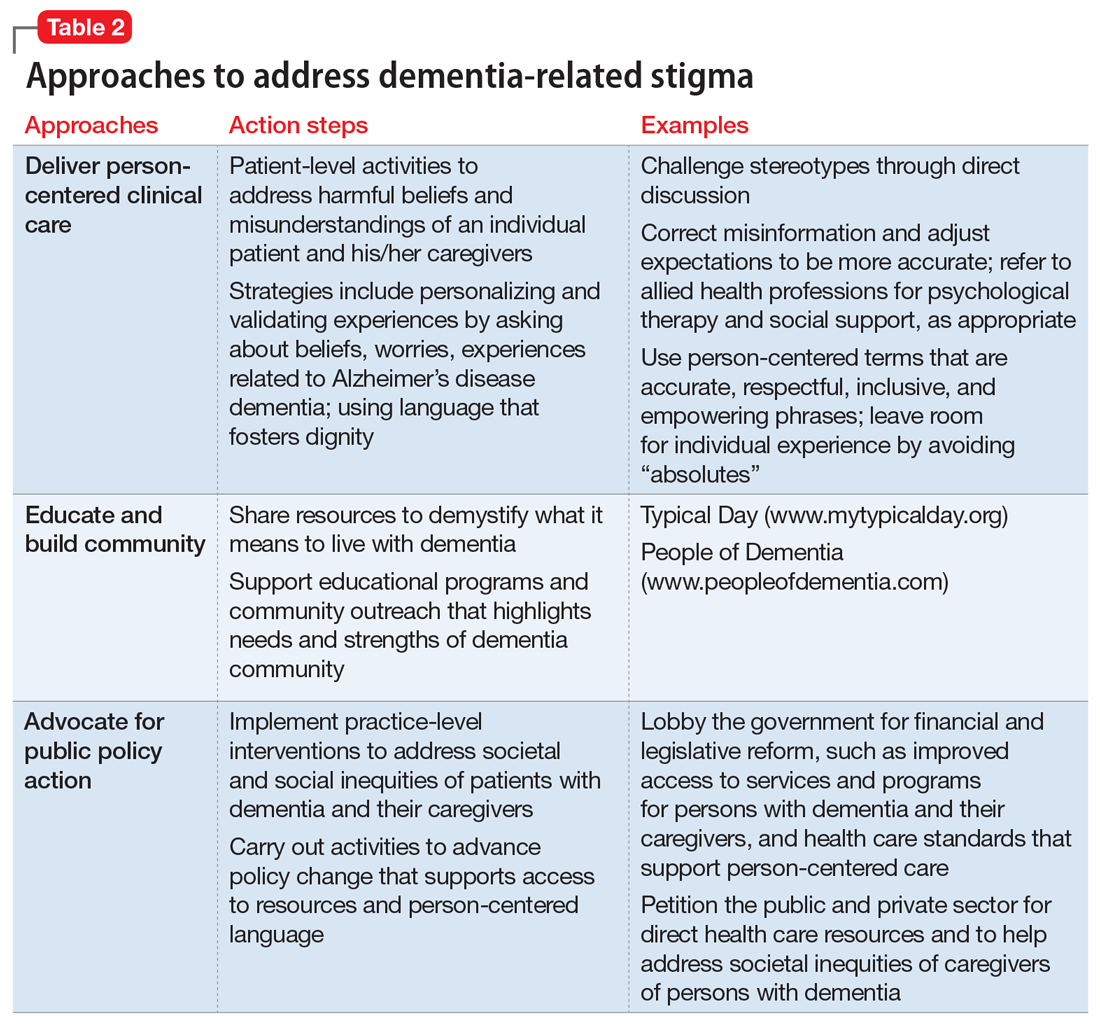

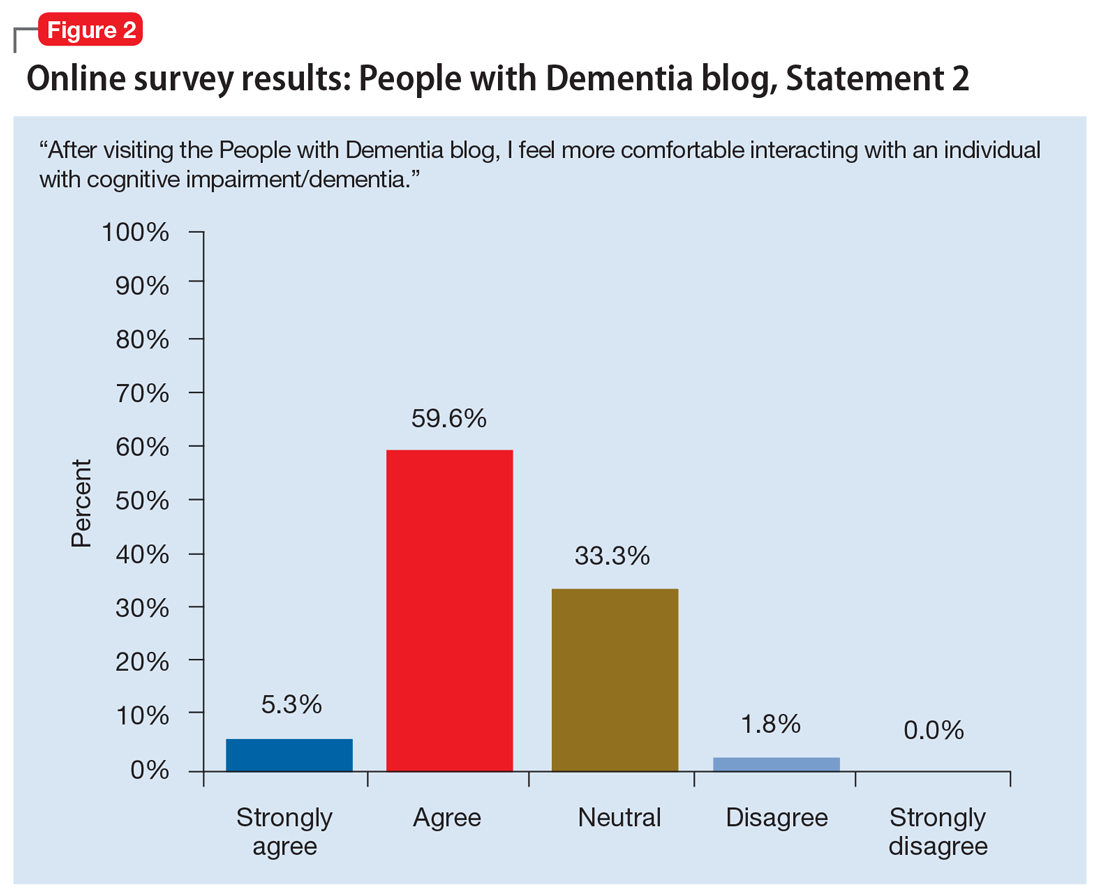

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

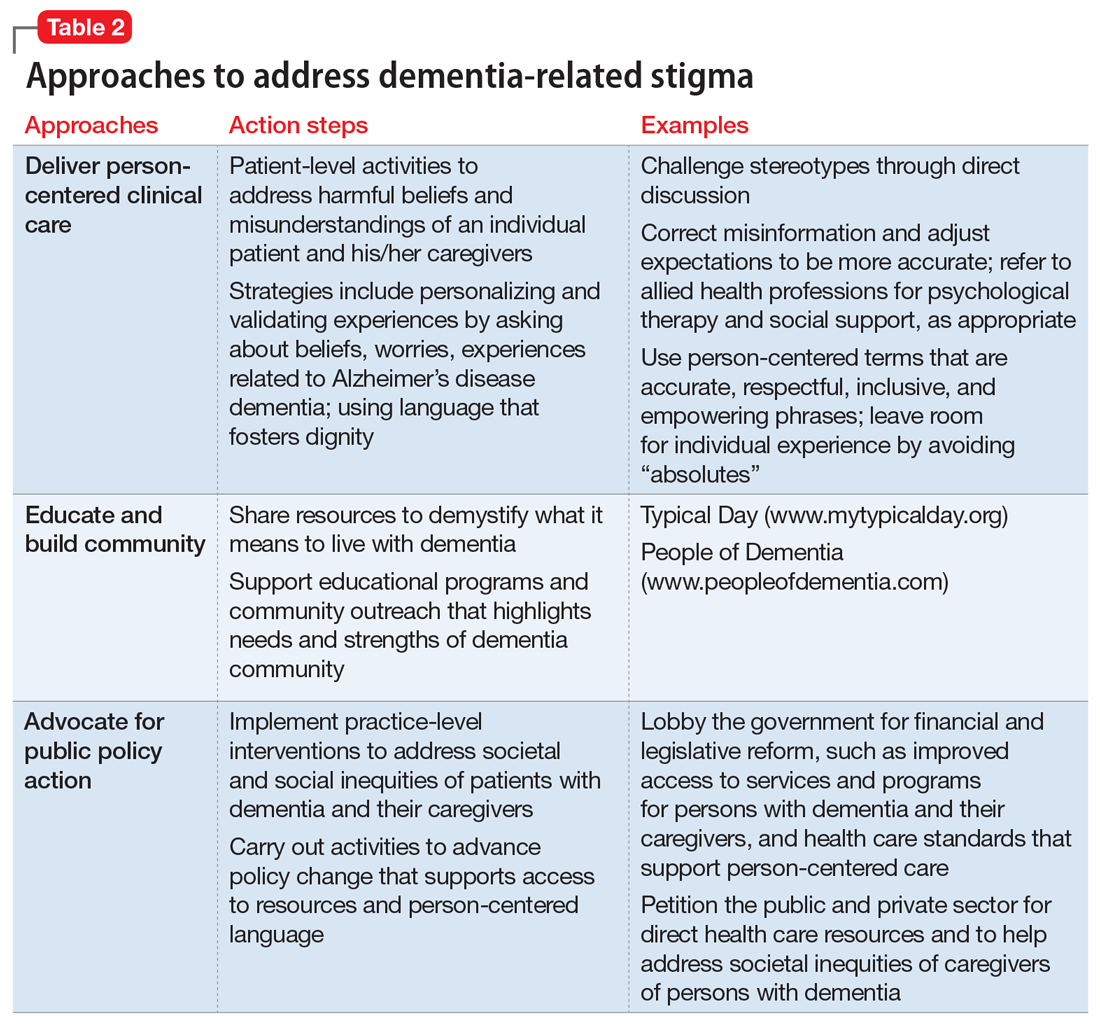

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

1. World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/policy_guidance/en/. Published 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

2. Goffman E. Stigma. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1963:1-123.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed May 28, 2019.

4. Blay SL, Peluso ETP. Public stigma: the community’s tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163-171.

5. Piver LC, Nubukpo P, Faure A, et al. Describing perceived stigma against Alzheimer’s disease in a general population in France: the STIG-MA survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):933-938.

6. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316-331.

7. Eng KJ, Woo BKP. Knowledge of dementia community resources and stigma among Chinese American immigrants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):e3-e4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.003.

8. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):419-433.

9. Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Development and validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25(1):42-48.

10. Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585-595.

11. Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):812-820.

12. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkounkova Y, et al. Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia. 2015;14(5):609-632.

13. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K. The effects of perceived stigma on persons with dementia and their family caregivers. In: Symposium on Stigma: It’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

14. Harper L, Dobbs B, Royan H, et al. The experience of stigma in care partners of people with dementia – results from an exploratory study. In Symposium on stigma: it’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

15. Burgener S, Berger B. Measuring perceived stigma in persons with progressive neurological disease: Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson disease. Dementia. 2008;7(1):31-53.

16. Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;10;285-300.

17. Anderson LA, Egge R. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer’s disease: the Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(50):S453-S456.

18. Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup. Report on the milestones for the US National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2014;10(Suppl 5);S430-S452. doi:10.1016/j/jalz.2014.08.103.

19. Kirkman AM. Dementia in the news: the media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2006;25(2):74-79.

20. Swaffer, K. Dementia: stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia. 2014;13(6):709-716.

21. Stites SD, Karlawish J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Practical Neurology. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2018-june/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia. Published June 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

22. Jamieson J, Dobbs B, Charles L, et al. Forgetful, but not forgotten people of dementia: a novel, technology focused project with a humanistic touch. Geriatric Grand Rounds; October 10, 2017. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

23. Dobbs B, Charles L, Chan K, et al. People of Dementia. CGS 37th Annual Scientific Meeting: Integrating Care, Making an Impact. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(3):220.

24. Government of Canada. Conference report: National Dementia Conference. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/national-dementia-conference-report.html. Government of Canada. Published August 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

25. The Gerontological Society of America. Program Abstracts from the GSA 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting “The Purposes of Longer Lives.” Innovation in Aging. 2018;2(Suppl 1):143.

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

Dementia is a family of disorders characterized by a decline in multiple cognitive abilities that significantly interferes with an individual’s functioning. An estimated 50 million people are living with a dementia worldwide.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for approximately two-thirds of dementia cases.1 These numbers are expected to increase dramatically in the upcoming decades.

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “an attribute, behaviour, or reputation which is socially discrediting in a particular way: it causes an individual to be mentally classified by others in an undesirable, rejected stereotype rather than in an accepted, normal one.”2 Goffman2 defined 3 broad categories of stigma: public, self, and courtesy (Table 12).

Considerable evidence shows that the combined impact of having dementia and the negative response to the diagnosis significantly undermines an individual’s psychosocial well-being and quality of life.3 Persons with dementia (PwD) commonly report a loss of identity and self-worth, and stigma appears to deepen this distress.3 Stigma also negatively affects individuals associated with PwD, including family members and professionals. In this article, we discuss the impact of dementia-related stigma, and steps you can take to address it, including implementing person-centered clinical practices, promoting anti-stigma messaging campaigns, and advocating for public policy action to improve the lives of PwD and their families.

A pervasive problem

Although the Alzheimer’s Society International and the World Health Organization acknowledge that stigma has a central role in defining the experience of AD, how stigma may present, how clinicians and researchers can recognize and measure stigma, and how to best combat it have been understudied.3-5 A recent systematic literature review examined worldwide evidence on dementia-related stigma over the past decade.6 Hermann et al6 found that health care providers and the general public may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward PwD, and that stigma may be particularly harsh among racial and ethnic minorities, although the literature is scarce in this area. Cultural factors may also worsen stigma, and stigma may be associated with reduced awareness of dementia services and reduced help-seeking among minority groups.7,8 Studies show that stigmatizing attitudes are more pronounced in people with limited knowledge of dementia, in those with little contact with PwD, in men, in younger individuals, and in the context of cultural interpretations of dementia.6 Health care providers can also sometimes contribute to the perpetuation of stigma.6

In terms of standardized scales or instruments for evaluating dementia-related stigma, there is no uniformly accepted “gold standard” measure, which makes it difficult to compare studies.6 In order to effectively study efforts to reduce stigma, researchers need to identify and establish a consensus on rating scales for evaluating stigma among PwD, caregivers, and the general public. Three instruments that may be used for this purpose are the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS),9 the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI),10 and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC).11

The detrimental effects of stigma

Burgener et al12 reported that personal stigma impacted functioning and quality of life in PwD. Higher levels of stigma were associated with higher anxiety, depression, and behavioral symptoms and lower self-esteem, social support, participation in activities, personal control, and physical health.12 Personal characteristics that may affect stigma include gender, location (rural vs urban), ethnicity, education level, and living arrangements (alone vs with family).12

In a subset of PwD with early-stage memory loss (n = 22), Burgener and Buckwalter13 found that 42% of participants were reluctant to reveal their diagnosis to others, with some fearing they would no longer be allowed to live alone and would be “sent to a facility.” In addition, 46% indicated they did not want “to be talked about like they were not there.” More than 50% of participants reported changes in their social network after receiving the diagnosis, including reducing activities and limiting types of contacts (ie, telephone only) or interacting only when “people come to me.” Participants were most comfortable with good friends “who understand” and persons within their faith communities. When asked about how they were treated by family members, >50% of participants described being treated differently, including loss of financial independence, more limited contact, and being “treated like a baby” by their children, who in general were uncomfortable talking about the diagnosis.

Continue to: In a recent study...

In a recent study by Harper et al,14 stigma was prevalent in the experience of PwD. One participant disclosed:

“I think there is [are] people I know who don’t ask me to go places or do things ’cause I have a dementia…I think lots of people don’t know what dementia is and I think it scares them ’cause they think of it as crazy. It hurts…”

Another participant said:

“I have had friends for over thirty years. They have turned their backs on me…we used to go for walks and they would phone me and go for coffee. Now I don’t hear from any of them…those aren’t true friends…true friends will stand behind you, not in front of you. That’s why I am not happy.”

Overall, quantitative and qualitative findings indicate multiple, detrimental effects of personal stigma on PwD. These effects fit well with measures of self-stigma, including social rejection (eg, being treated differently, participating in fewer activities, and having fewer friends), internalized shame (eg, being treated like a child, having fewer responsibilities, others acting as if dementia is “contagious”), and social isolation (eg, being less outgoing, feeling more comfortable in small groups, having limited social contacts).15

Continue to: Receiving a diagnosis of dementia...

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges.16 Many of these challenges are the consequence of stigma. A broad range of efforts are underway worldwide to reduce dementia-related stigma. These efforts include programs to promote public awareness and education, campaigns to develop inclusive social policies, and skills-based training initiatives to promote delivery of patient-centered care by clinicians and educators.3,17,18 Many of these efforts share a common focus on promoting the “dignity” and “personhood” of PwD in order to disrupt stereotypes or fixed, oversimplified beliefs associated with dementia.

Implementing person-centered clinical care

In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Health care communications that call attention to stereotypes may allow PwD to identify stereotypes as well as inaccuracies in those stereotypes. Interventions that validate the value of diversity can help PwD accept the ways in which they may not conform to social norms. This could include language such as “There is no one way to have Alzheimer’s disease. A person’s experience can differ from what others might experience or expect, and that’s okay.” In addition, the use of language that is accurate, respectful, inclusive, and empowering can support PwD and their caregivers.19,20 For example, referring to PwD as “individuals living with dementia” rather than “those who are demented” conveys respect and appreciation for personhood. Other clinicians have provided additional practical suggestions.21

Anti-stigma messaging campaigns

The mass media is a common source of stereotypes about AD and other dementias. They typically present a “worst-case” scenario that promotes ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions, which may worsen stigma and discrimination towards PwD and the people who care for them. However, public messaging campaigns are emerging to counter negative messages and stereotypes in the mass media. Projects such as Typical Day, People with Dementia, and other online anti-stigma messaging campaigns allow a broad audience to gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of PwD and their caregivers. These projects are rich resources that offer education and personal stories that can counter common stereotypes about dementia.

Typical Day is a photography project developed and maintained by clinicians and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Since early 2017, the project has provided a forum for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia to document their lives and show what it means to them to live with dementia. Participants in the project photo-document the people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. They review and explain these photos with researchers at Penn Memory Center, who help them tell their stories. The participants’ stories, the photos they capture, and their portraits are available at www.mytypicalday.org.

People of Dementia. Storytelling is a powerful way to raise awareness of and reduce the stigma associated with dementia. For PwD, telling their stories can be an effective and therapeutic way to communicate their emotions and deliver an important message. In the blog People of Dementia (www.peopleofdementia.com),22,23 PwD highlight who they were before the disease and how things have changed, with family members highlighting the challenges of caring for a person with dementia.

Continue to: The common thread is...

The common thread is the enduring “person” behind the exterior that is obscured by dementia. By allowing the audience to form a connection with who the individual was prior to the disease, and understanding the changes that have come as a result of dementia to both PwD and their support network, readers gain a greater appreciation of those affected by dementia. Between May 1, 2017 and May 31, 2019, the blog had more than 3,860 visitors. In an accompanying online survey (N = 57), 79% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that after visiting the People of Dementia blog, they had a better understanding of the changes that occur as a result of cognitive impairment/dementia (Figure 1). Almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more comfortable interacting with PwD (Figure 2). Additionally, 60% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they were more encouraged to work with PwD, and 90% agreed/strongly agreed that they had a greater appreciation of the challenges of being a caregiver for PwD. Overall, these findings suggest that the People of Dementia blog is useful for engaging the public and promoting a better understanding of dementia.

Work for policy changes

Clinicians can support public policy through education and advocacy both in the delivery of care and as spokespersons and stakeholders in their local communities. Public policies are important for providing access to medical and social services to meet the needs of PwD and their caregivers. The absence—real or perceived—of sufficient resources exacerbates dementia-related stigma. In addition to facilitating access to resources, national dementia strategies or legal frameworks, such as the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States, include policy initiatives to identify and promote communication approaches that are effective and sensitive with respect to people living with dementia and their caregivers.

State and local legislators and patient advocates are leading policy efforts to reduce dementia-related stigma. For example, Colorado recently changed statutory references from being specific to diseases that cause dementia to the broader, more inclusive phrase “dementia diseases and related disabilities.”18 In addition to making funds available to support caregiving services for PwD, this legislative change added training for first responders to better meet the needs of missing PwD, and shifted the terminology used to diagnose and communicate about diseases causing dementia. The shift in language added new terminology that was chosen for being more person-centered to replace prior references to “senior senility,” “senility,” and other terms with pejorative meanings.

In Canada, a National Dementia Strategy will commit the Canadian government to action with definitive timelines, targets, reporting structures, and measurable outcomes.24

Table 2 summarizes approaches to a

Continue to: An open discussion

An open discussion

Larger studies and testing of diverse approaches are needed to better understand whether intergenerational initiatives or other approaches can genuinely modify stigmatizing attitudes in various dementia populations, especially considering language, health literacy, cultural preferences, and other needs. The identified effects on physical and mental health, quality of life, self-esteem, and behavioral symptoms further support the extensive, negative effects of self-stigma on PwD, and emphasize the need to develop and test interventions to ameliorate these effects.

We presented at a Stigma Symposium at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.25 Attendees of this conference shared our concerns about the detrimental effects of stigma. The main question we were asked was “What can we do to reduce stigma?” Perhaps the most immediate response is that in order to move the stigma dial, clinicians need to recognize that stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on PwD and their families.6 Bringing the discussion into the open and targeting stigma at multiple levels needs to be addressed by clinicians, researchers, administrators, and society at large.

Bottom Line

Stigma has multiple, broad-reaching, and negative effects on persons with dementia and their families. In clinical practice, direct discussion that encourages reflection and the use of effective and sensitive communication can help to limit passing on stigmatizing beliefs and to reduce negative stereotypes associated with the disease. Anti-stigma messaging campaigns and public policy changes also can be used to address societal and social inequities of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

Related Resources

- Khoury R, Shach R, Nair A, et al. Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):29-36,38.

- Burke AD, Burke WJ. Antipsychotics for patients with dementia: The road less traveled. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):26-32,35-37.

1. World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/policy_guidance/en/. Published 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

2. Goffman E. Stigma. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1963:1-123.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed May 28, 2019.

4. Blay SL, Peluso ETP. Public stigma: the community’s tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163-171.

5. Piver LC, Nubukpo P, Faure A, et al. Describing perceived stigma against Alzheimer’s disease in a general population in France: the STIG-MA survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):933-938.

6. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316-331.

7. Eng KJ, Woo BKP. Knowledge of dementia community resources and stigma among Chinese American immigrants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):e3-e4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.003.

8. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):419-433.

9. Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Development and validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25(1):42-48.

10. Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585-595.

11. Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):812-820.

12. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkounkova Y, et al. Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia. 2015;14(5):609-632.

13. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K. The effects of perceived stigma on persons with dementia and their family caregivers. In: Symposium on Stigma: It’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

14. Harper L, Dobbs B, Royan H, et al. The experience of stigma in care partners of people with dementia – results from an exploratory study. In Symposium on stigma: it’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.

15. Burgener S, Berger B. Measuring perceived stigma in persons with progressive neurological disease: Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson disease. Dementia. 2008;7(1):31-53.

16. Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;10;285-300.

17. Anderson LA, Egge R. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer’s disease: the Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10(50):S453-S456.

18. Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup. Report on the milestones for the US National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2014;10(Suppl 5);S430-S452. doi:10.1016/j/jalz.2014.08.103.

19. Kirkman AM. Dementia in the news: the media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2006;25(2):74-79.

20. Swaffer, K. Dementia: stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia. 2014;13(6):709-716.

21. Stites SD, Karlawish J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Practical Neurology. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2018-june/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia. Published June 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

22. Jamieson J, Dobbs B, Charles L, et al. Forgetful, but not forgotten people of dementia: a novel, technology focused project with a humanistic touch. Geriatric Grand Rounds; October 10, 2017. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

23. Dobbs B, Charles L, Chan K, et al. People of Dementia. CGS 37th Annual Scientific Meeting: Integrating Care, Making an Impact. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(3):220.

24. Government of Canada. Conference report: National Dementia Conference. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/national-dementia-conference-report.html. Government of Canada. Published August 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

25. The Gerontological Society of America. Program Abstracts from the GSA 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting “The Purposes of Longer Lives.” Innovation in Aging. 2018;2(Suppl 1):143.

1. World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/policy_guidance/en/. Published 2018. Accessed May 28, 2019.

2. Goffman E. Stigma. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1963:1-123.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed May 28, 2019.

4. Blay SL, Peluso ETP. Public stigma: the community’s tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163-171.

5. Piver LC, Nubukpo P, Faure A, et al. Describing perceived stigma against Alzheimer’s disease in a general population in France: the STIG-MA survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):933-938.

6. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316-331.

7. Eng KJ, Woo BKP. Knowledge of dementia community resources and stigma among Chinese American immigrants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):e3-e4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.003.

8. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. J Aging Health. 2010;22(4):419-433.

9. Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Development and validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25(1):42-48.

10. Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585-595.

11. Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):812-820.

12. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkounkova Y, et al. Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia. 2015;14(5):609-632.

13. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K. The effects of perceived stigma on persons with dementia and their family caregivers. In: Symposium on Stigma: It’s time to talk about it. Boston, MA: Gerontological Society of America 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting; 2018. Session 2805.