User login

Loneliness tied to increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

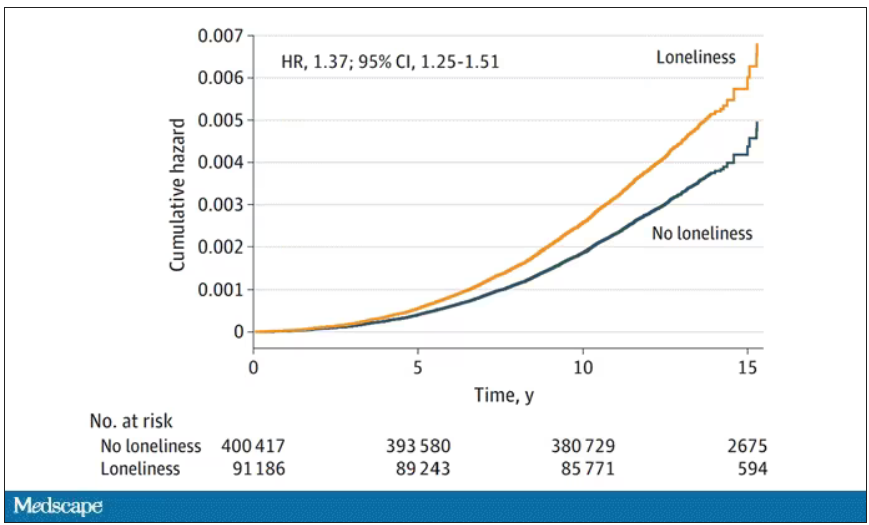

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

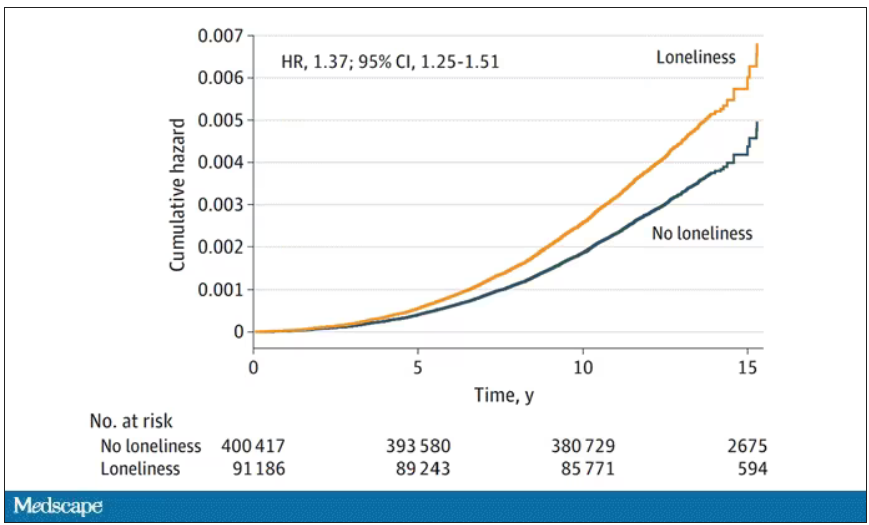

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

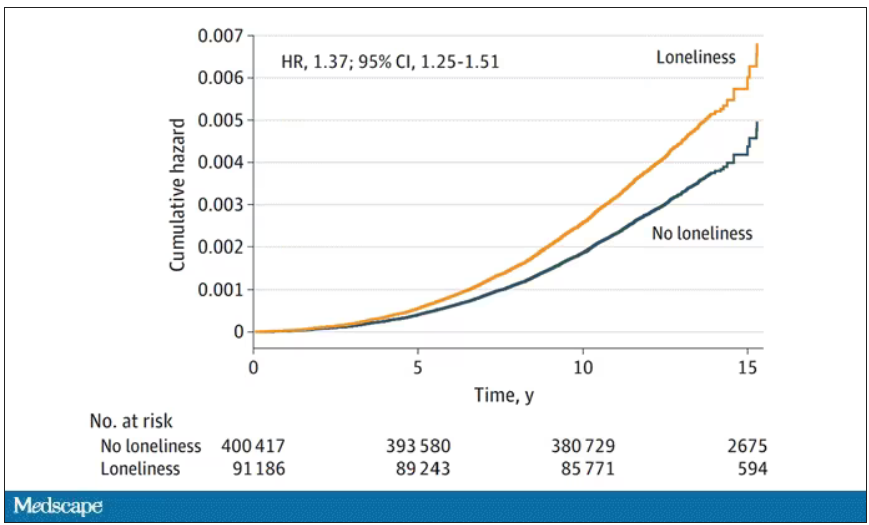

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The surprising link between loneliness and Parkinson’s disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Data Trends 2023: Migraine and Headache

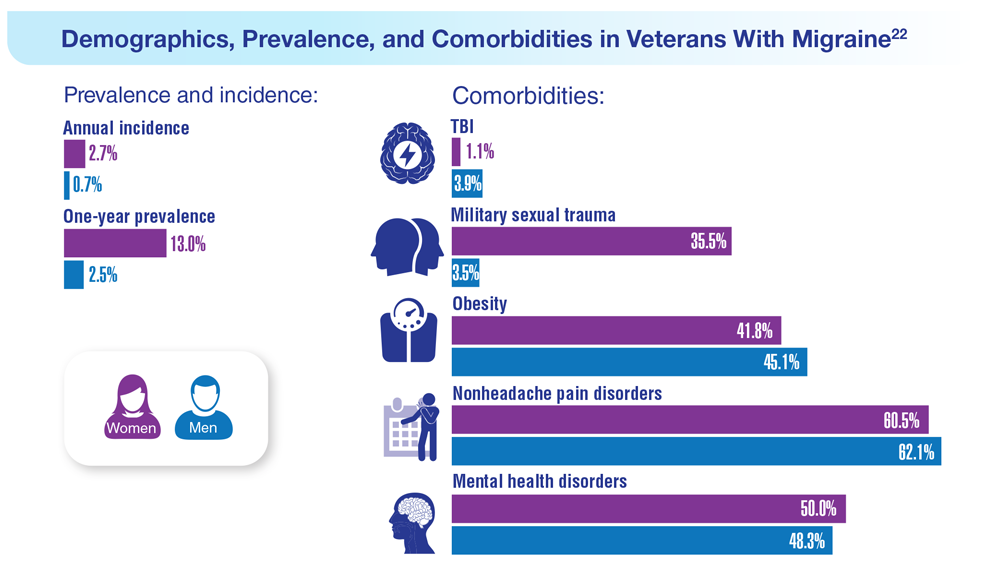

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

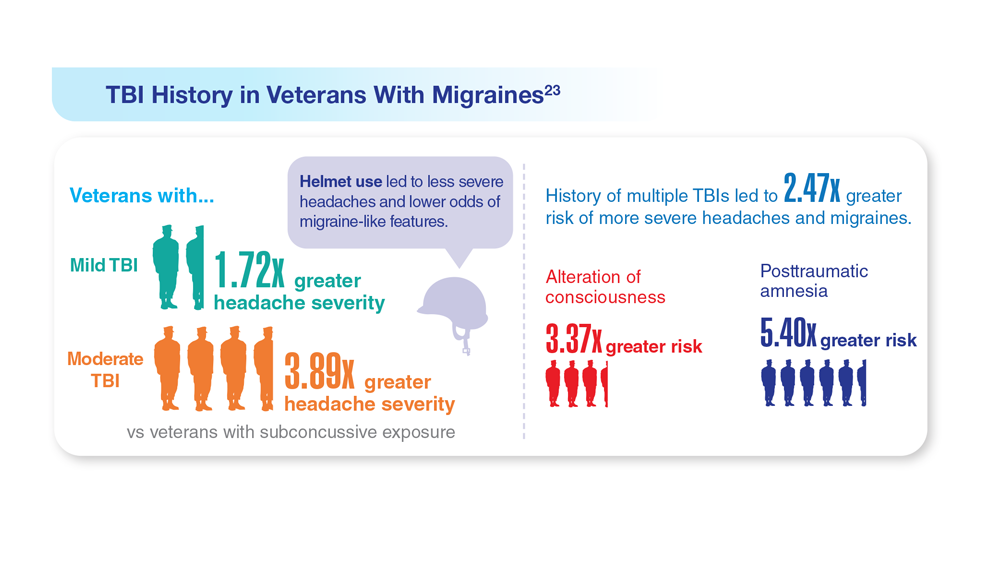

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

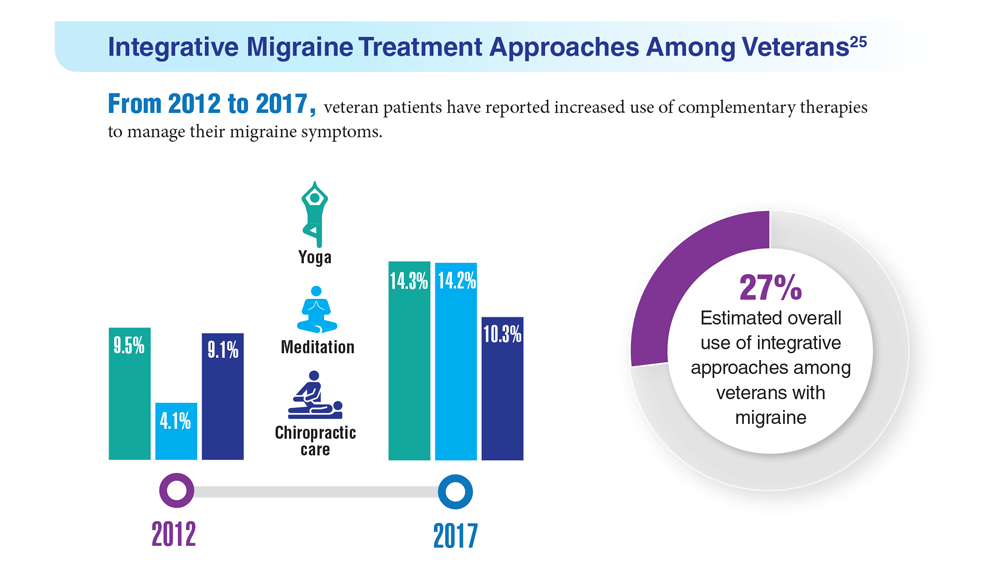

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

22. Seng EK et al. Neurology. 2022;99(18):e1979-e1992. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200888

23. Coffman C et al. Neurology. 2022;99(2):e187-e198. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200518

24. Hesselbrock RR et al. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2022;93(1):26-31. doi:10.3357/amhp.5980.2022

25. Kuruvilla DE et al. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12906-022-03511-6

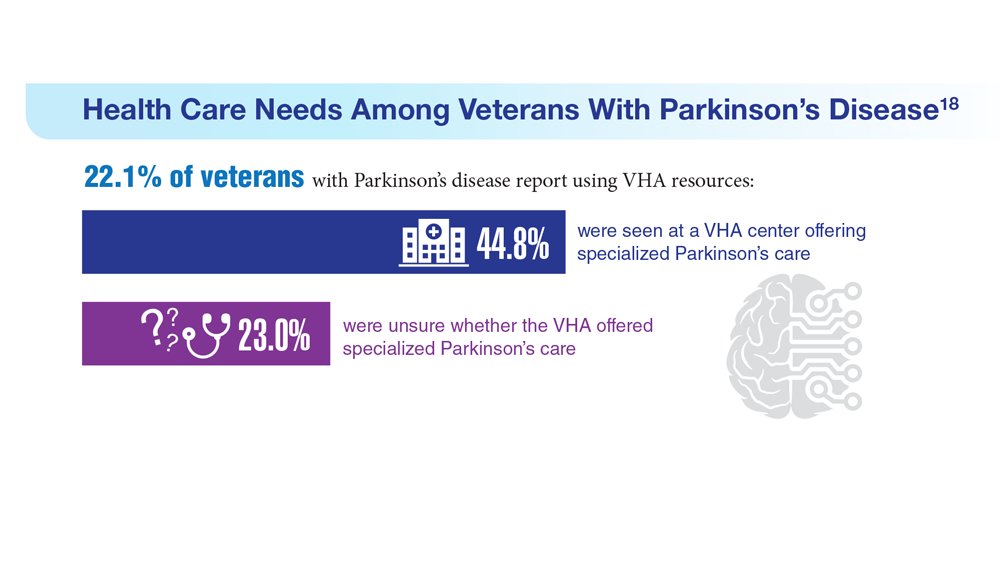

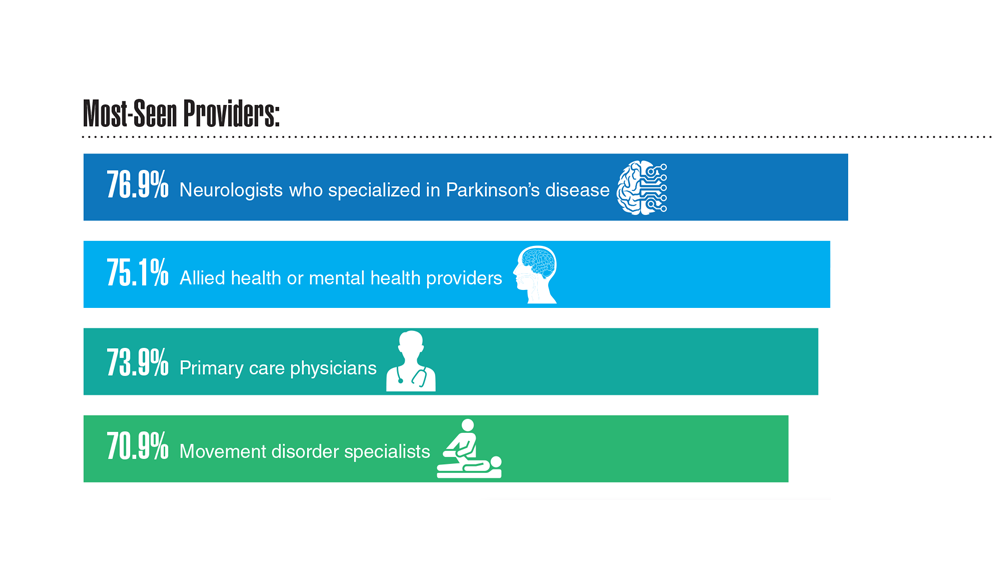

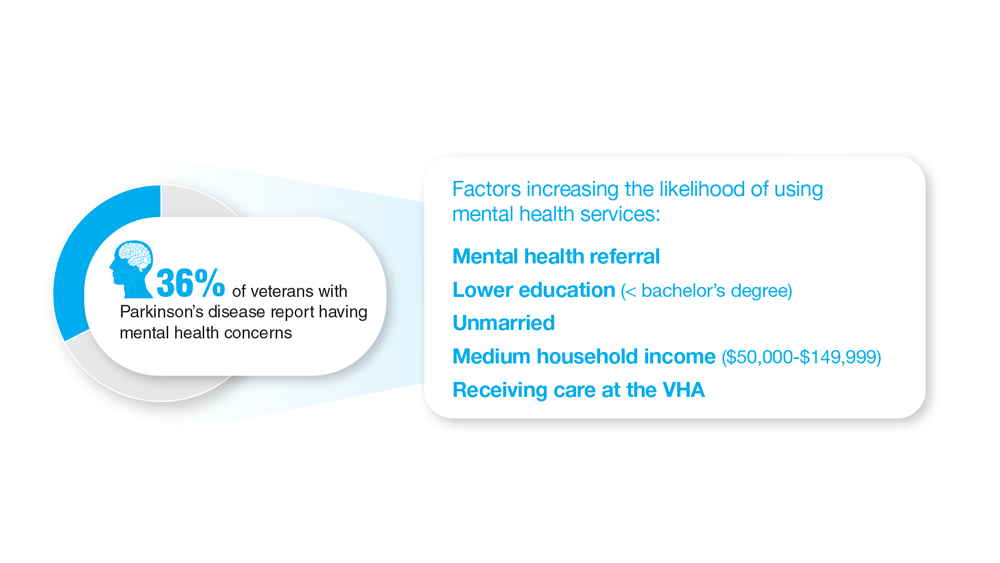

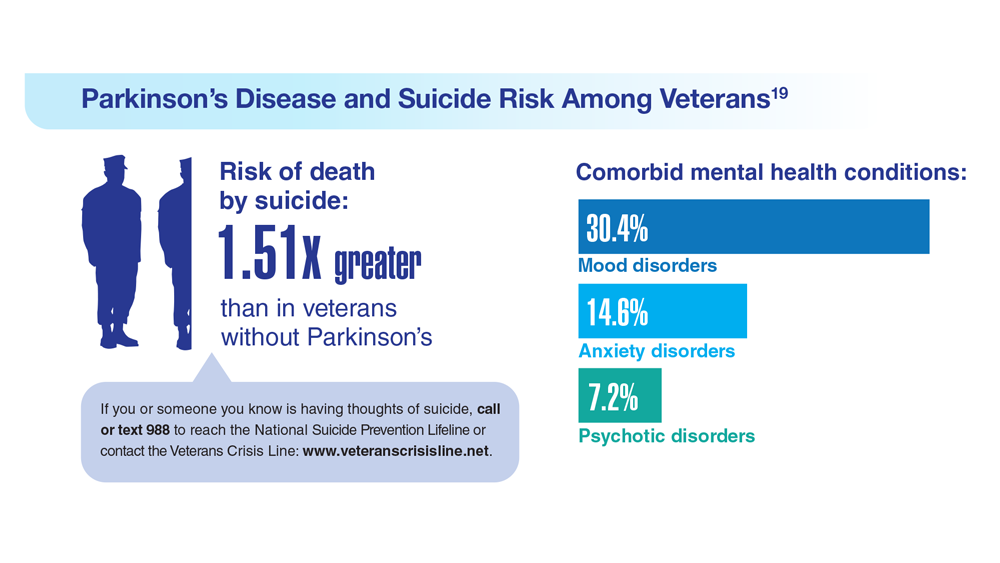

Data Trends 2023: Parkinson’s Disease

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Parkinson’s disease. Updated October 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023.

https://www.research.va.gov/topics/parkinsons.cfm

18. Feeney M et al. Front Neurol. 2022;13:924999. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.924999

19. Heronemus M et al. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;105:58-61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.11.003

20. Nejtek VA et al. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258851. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258851

21. Yang Y et al. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15(3):75-81. doi:10.12779/dnd.2016.15.3.75

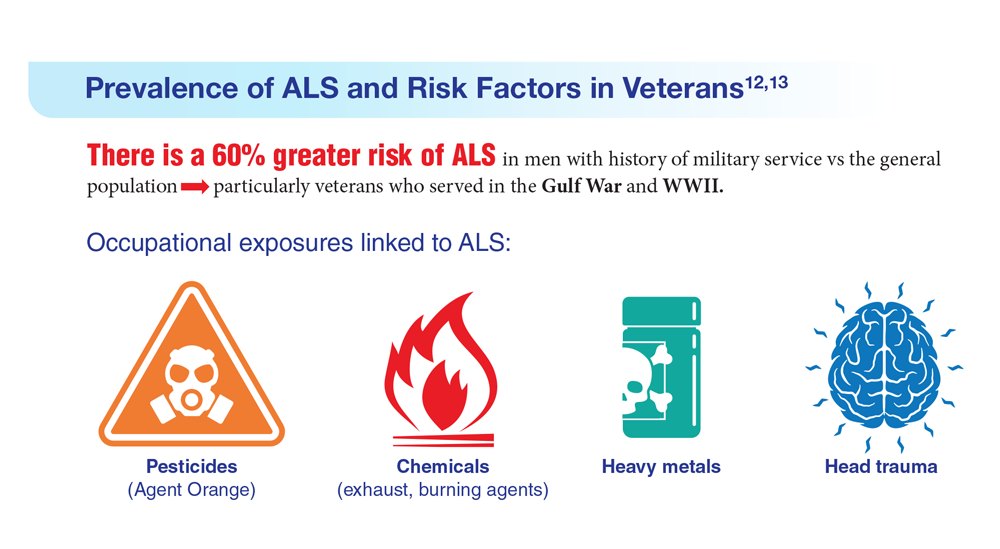

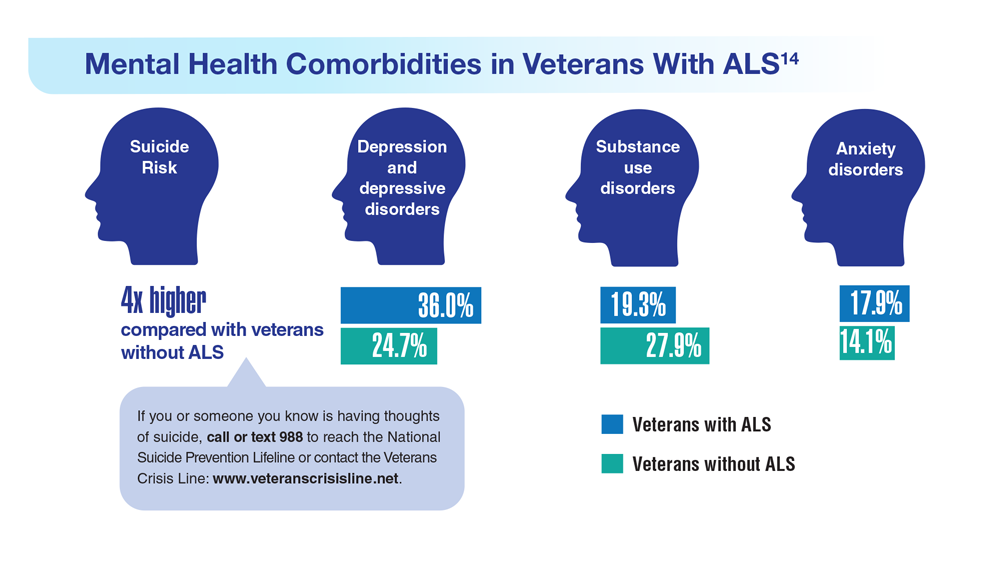

Data Trends 2023: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

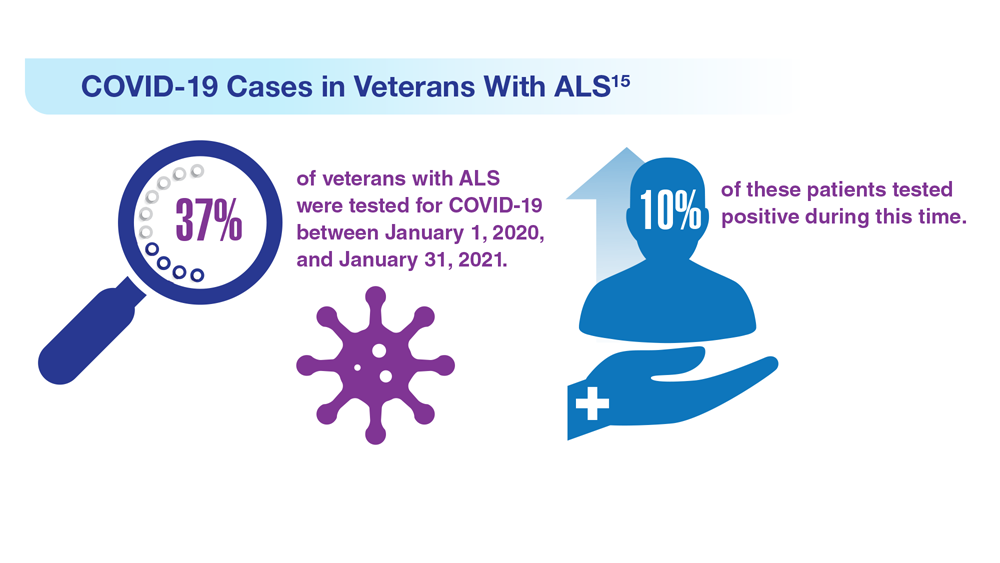

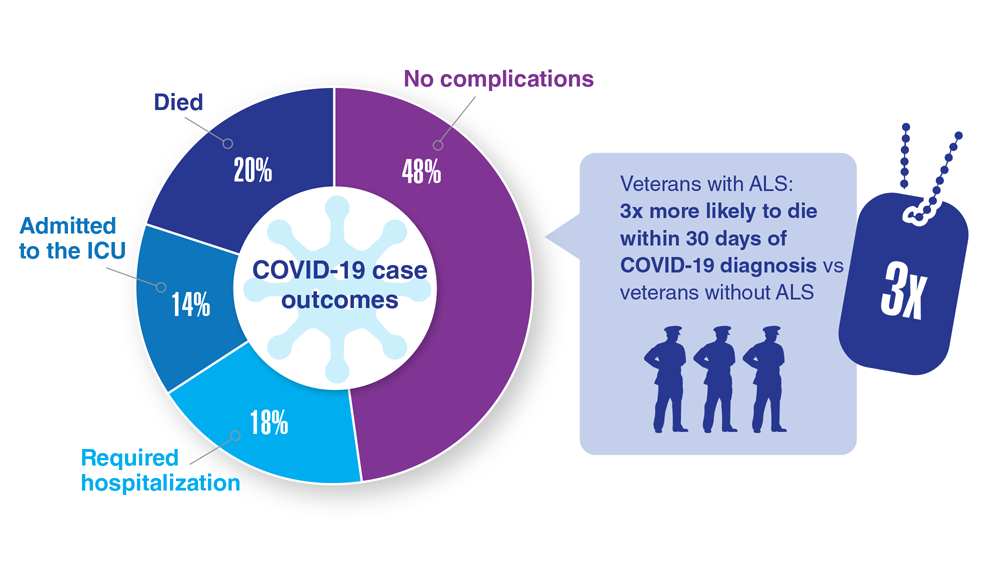

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

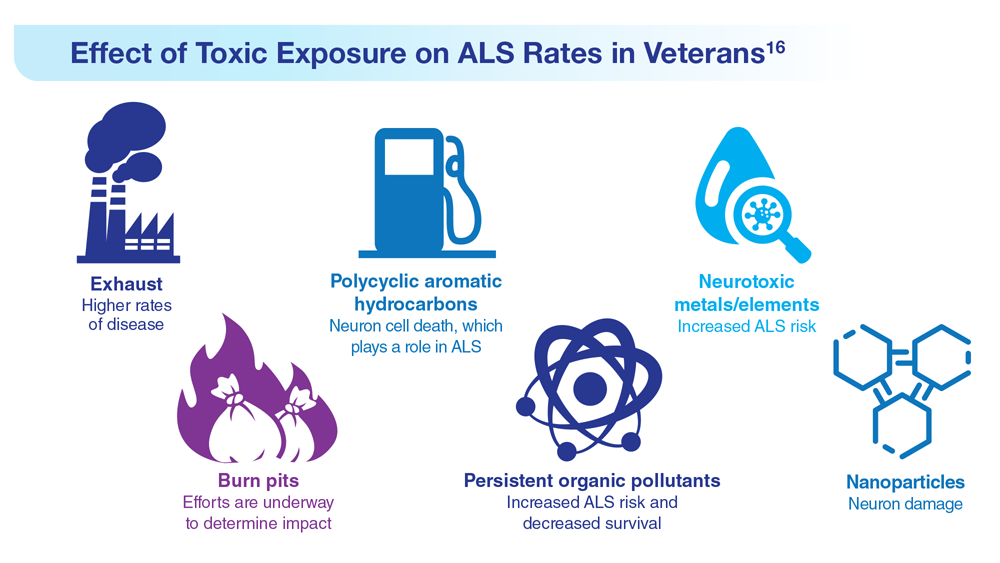

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

12. The ALS Association. ALS in the military. https://www.als.org/navigating-als/military-veterans/ALS-in-the-Military

13. McKay KA et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;143(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/ane.13345

14. Lund EM et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):807-811. doi:10.1002/mus.27181

15. Galea MD et al. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(4):E18-E20. doi:10.1002/mus.27373

16. Re DB et al. J Neurol. 2022;269(5):2359-2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10928-5

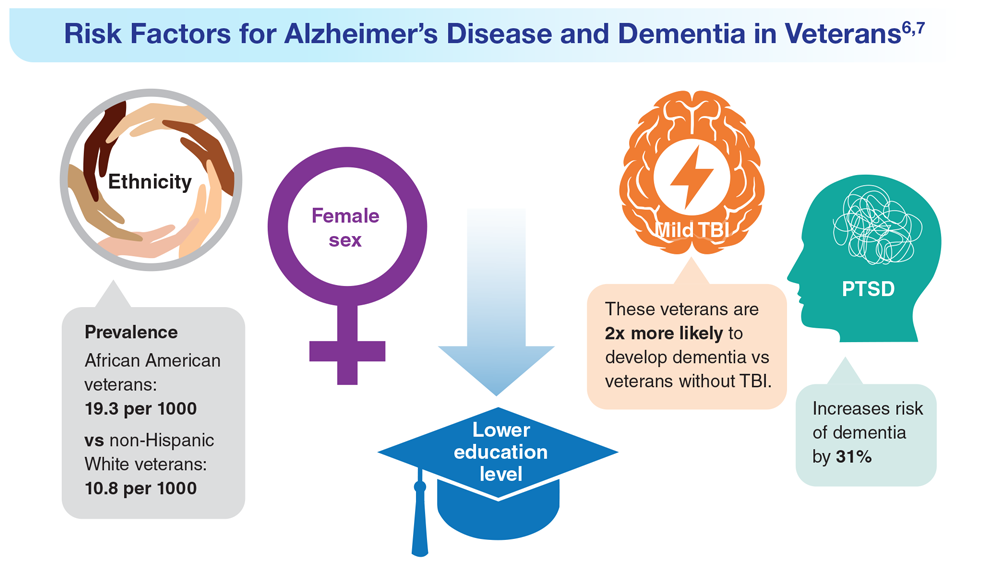

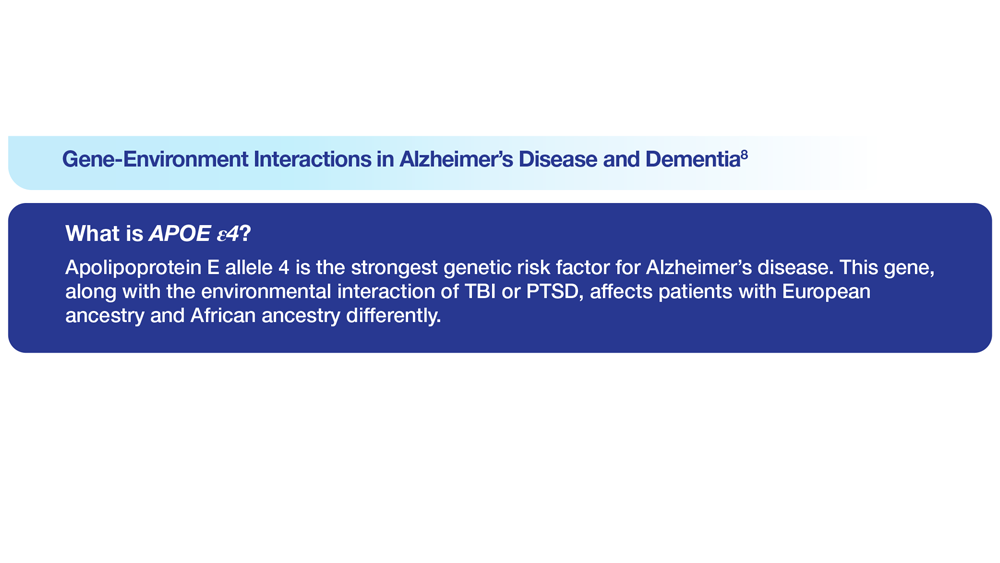

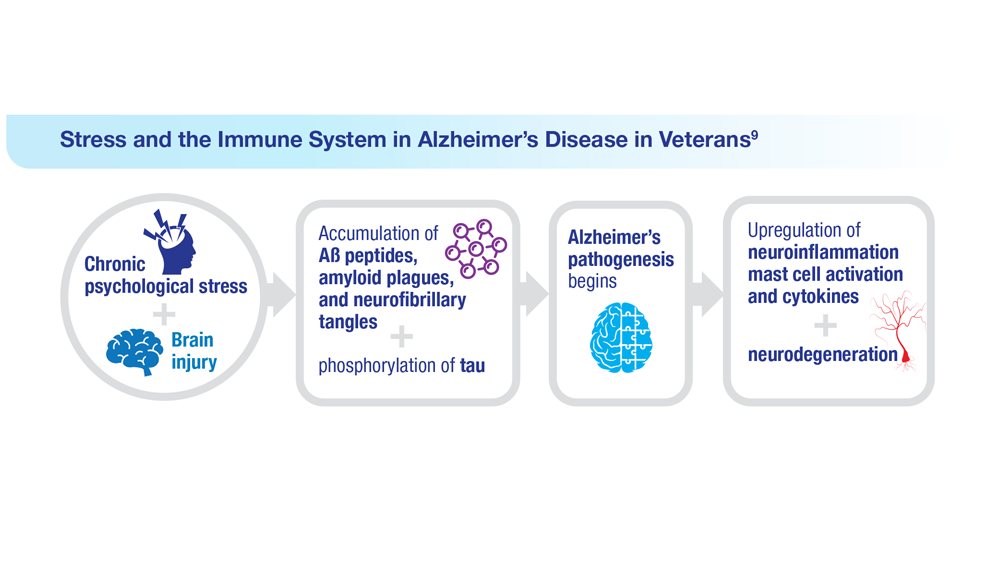

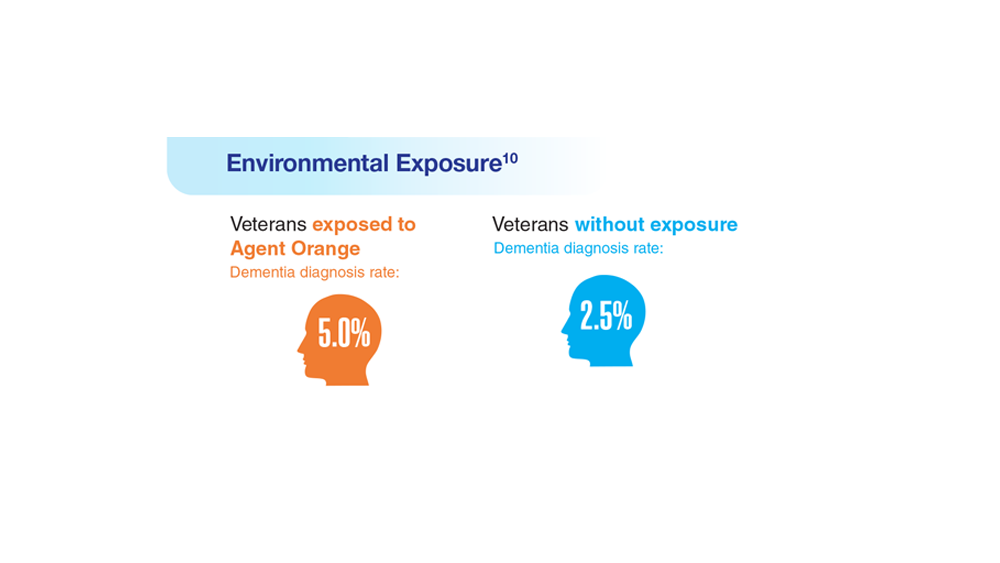

Data Trends 2023: Alzheimer’s and Dementia

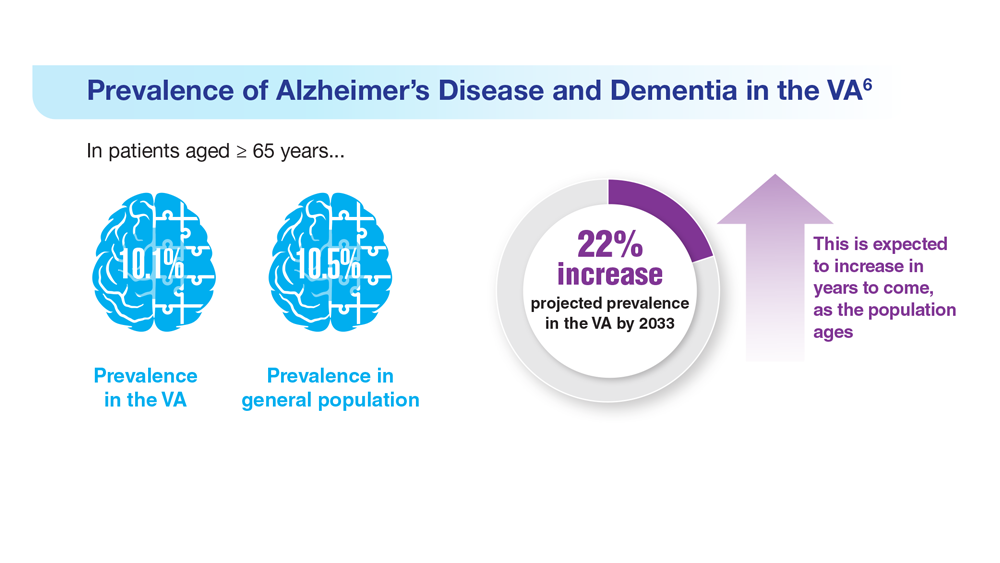

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

6. Zhu CW, Sano M. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:610334. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.610334

7. Nianogo RA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):584-591. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976

8. Logue MW et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec 22. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/alz.12870

9. Kempuraj D et al. Clin Ther. 2020;42(6):974-982. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.018

10. Martinez S et al. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):473-477. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5011

11. Verger A et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50(6):1553-1555. doi:10.1007/s00259-023-06177-5

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2023

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Data Trends 2023: Traumatic Brain Injury

- Howard JT et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148150. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48150

- Cogan AM et al. PM R. 2020;12(3):301-314. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12237

- Stewart IJ et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1122-1129. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2682

- Leng Y et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Winkler SL et al. Optom Vis Sci. 2022;99(1):3-8. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001824

- Howard JT et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148150. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48150

- Cogan AM et al. PM R. 2020;12(3):301-314. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12237

- Stewart IJ et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1122-1129. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2682

- Leng Y et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Winkler SL et al. Optom Vis Sci. 2022;99(1):3-8. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001824

- Howard JT et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148150. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48150

- Cogan AM et al. PM R. 2020;12(3):301-314. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12237

- Stewart IJ et al. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1122-1129. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2682

- Leng Y et al. Neurology. 2021;96(13):e1792-e1799. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011656

- Winkler SL et al. Optom Vis Sci. 2022;99(1):3-8. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001824

Multivitamins and dementia: Untangling the COSMOS study web

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Neuropsychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease: Practical considerations

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition diagnosed pathologically by alpha synuclein–containing Lewy bodies and dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Loss of dopaminergic input to the caudate and putamen disrupts the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways for motor control and contributes to the motor symptoms of PD.1 According to the Movement Disorder Society criteria, PD is diagnosed clinically by bradykinesia (slowness of movement) plus resting tremor and/or rigidity in the presence of supportive criteria, such as levodopa responsiveness and hyposmia, and in the absence of exclusion criteria and red flags that would suggest atypical parkinsonism or an alternative diagnosis.2

Although the diagnosis and treatment of PD focus heavily on the motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms can arise decades before the onset of motor symptoms and continue throughout the lifespan. Nonmotor symptoms affect patients from head (ie, cognition and mood) to toe (ie, striatal toe pain) and multiple organ systems in between, including the olfactory, integumentary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic nervous systems. Thus, it is not surprising that nonmotor symptoms of PD impact health-related quality of life more substantially than motor symptoms.3 A helpful analogy is to consider the motor symptoms of PD as the tip of the iceberg and the nonmotor symptoms as the larger, submerged portions of the iceberg.4

Nonmotor symptoms can negatively impact the treatment of motor symptoms. For example, imagine a patient who is very rigid and dyscoordinated in the arms and legs, which limits their ability to dress and walk. If this patient also suffers from nonmotor symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and psychosis—both of which can be exacerbated by levodopa—dose escalation of levodopa for the rigidity and dyscoordination could be compromised, rendering the patient undertreated and less mobile.

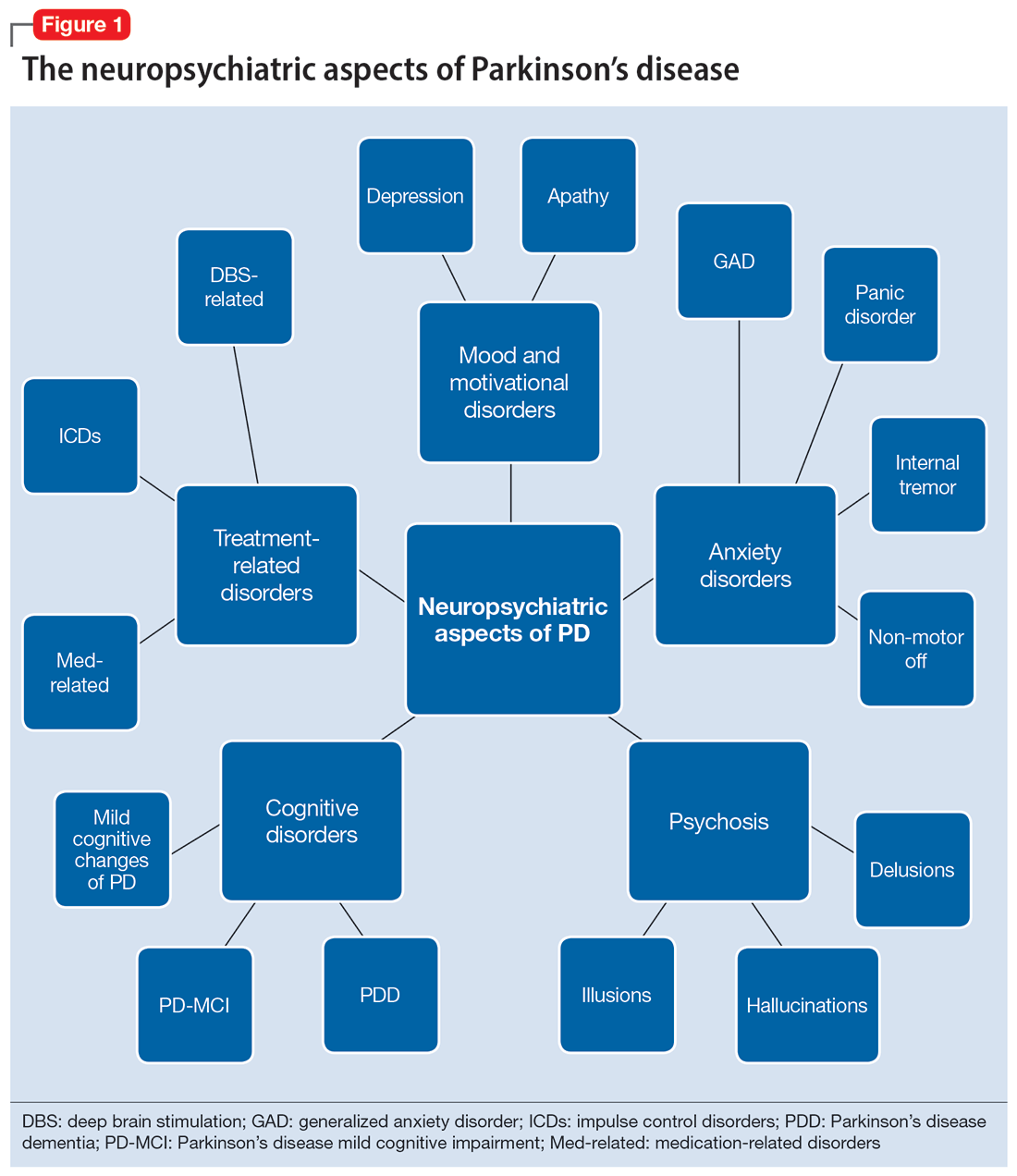

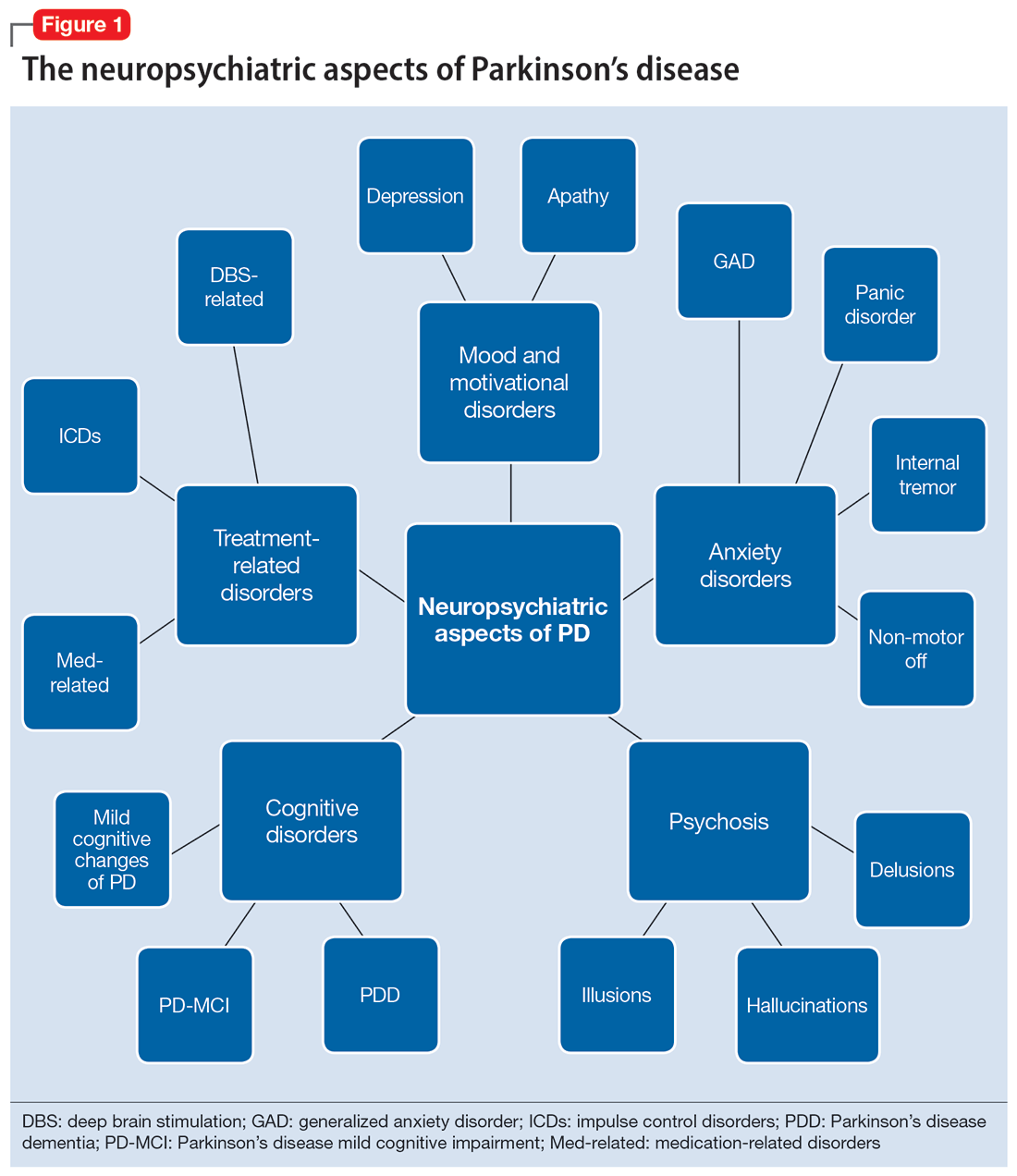

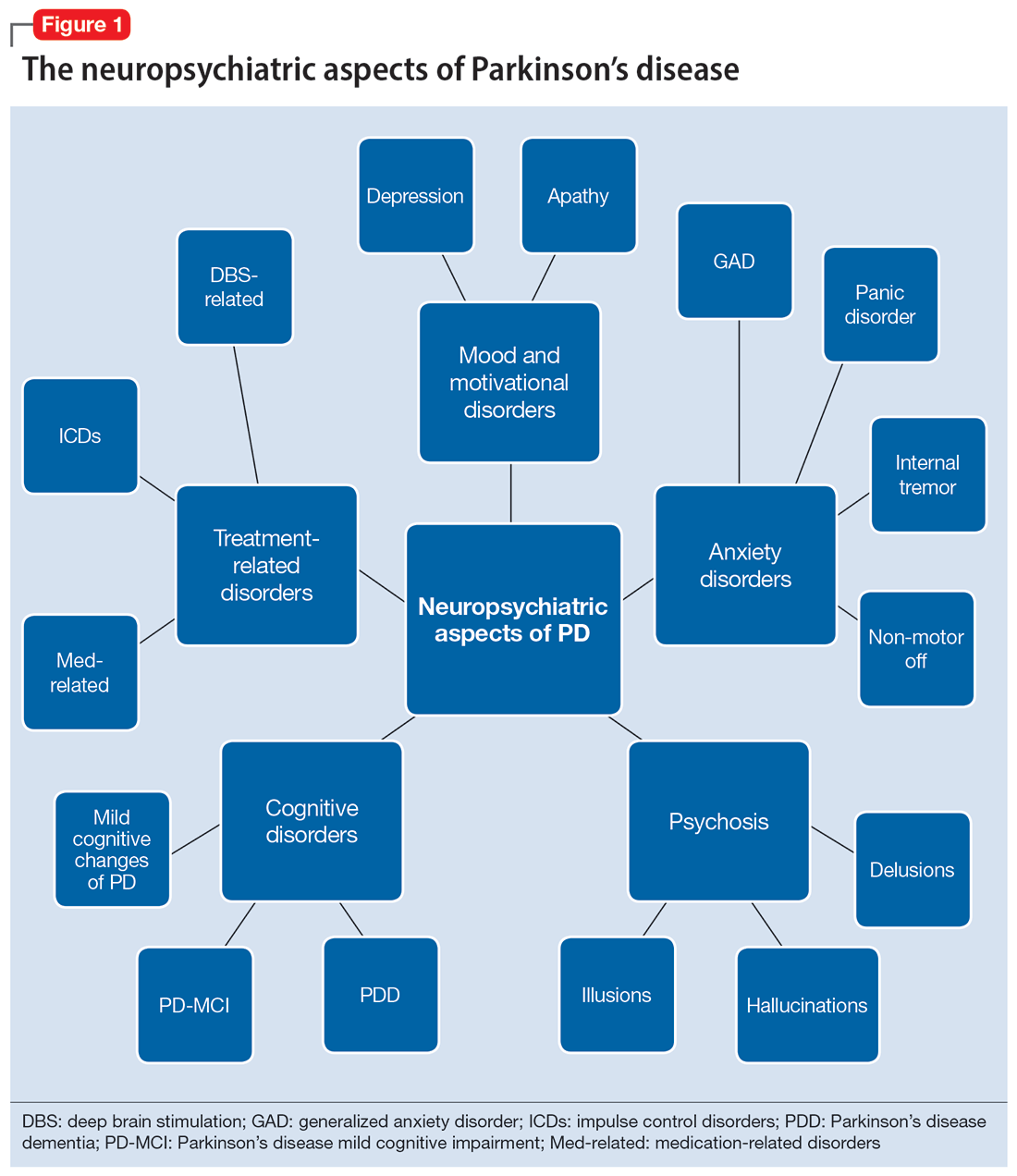

In this review, we focus on identifying and managing nonmotor symptoms of PD that are relevant to psychiatric practice, including mood and motivational disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, cognitive disorders, and disorders related to the pharmacologic and surgical treatment of PD (Figure 1).

Mood and motivational disorders

Depression

Depression is a common symptom in PD that can occur in the prodromal period years to decades before the onset of motor symptoms, as well as throughout the disease course.5 The prevalence of depression in PD varies from 3% to 90%, depending on the methods of assessment, clinical setting of assessment, motor symptom severity, and other factors; clinically significant depression likely affects approximately 35% to 38% of patients.5,6 How depression in patients with PD differs from depression in the general population is not entirely understood, but there does seem to be less guilt and suicidal ideation and a substantial component of negative affect, including dysphoria and anxiety.7 Practically speaking, depression is treated similarly in PD and general populations, with a few considerations.

Despite limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for efficacy specifically in patients with PD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line treatments. There is also evidence for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but due to potential worsening of orthostatic hypotension and cognition, TCAs may not be a favorable option for certain patients with PD.8,9 All antidepressants have the potential to worsen tremor. Theoretically, SNRIs, with noradrenergic activity, may be less tolerable than SSRIs in patients with PD. However, worsening tremor generally has not been a clinically significant adverse event reported in PD depression clinical trials, although it was seen in 17% of patients receiving paroxetine and 21% of patients receiving venlafaxine compared to 7% of patients receiving placebo.9-11 If tremor worsens, mirtazapine could be considered because it has been reported to cause less tremor than SSRIs or TCAs.12

Among medications for PD, pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, may have a beneficial effect on depression.13 Additionally, some evidence supports rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, as an adjunctive medication for depression in PD.14 Nevertheless, antidepressant medications remain the standard pharmacologic treatment for PD depression.

Continue to: In terms of nonpharmacologic options...

In terms of nonpharmacologic options, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is likely efficacious, exercise (especially yoga) is likely efficacious, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be efficacious.15,16 While further high-quality trials are needed, these treatments are low-risk and can be considered, especially for patients who cannot tolerate medications.

Apathy

Apathy—a loss of motivation and goal-directed behavior—can occur in up to 30% of patients during the prodromal period of PD, and in up to 70% of patients throughout the disease course.17 Apathy can coexist with depression, which can make apathy difficult to diagnose.17 Given the time constraints of a clinic visit, a practical approach would be to first screen for depression and cognitive impairment. If there is continued suspicion of apathy, the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part I question (“In the past week have you felt indifferent to doing activities or being with people?”) can be used to screen for apathy, and more detailed scales, such as the Apathy Scale (AS) or Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS), could be used if indicated.18

There are limited high-quality positive trials of apathy-specific treatments in PD. In an RCT of patients with PD who did not have depression or dementia, rivastigmine improved LARS scores compared to placebo.15 Piribedil, a D2/D3 receptor agonist, improved apathy in patients who underwent subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS).15 Exercise such as individualized physical therapy programs, dance, and Nordic walking as well as mindfulness interventions were shown to significantly reduce apathy scale scores.19 SSRIs, SNRIs, and rotigotine showed a trend toward reducing AS scores in RCTs.10,20

Larger, high-quality studies are needed to clarify the treatment of apathy in PD. In the meantime, a reasonable approach is to first treat any comorbid psychiatric or cognitive disorders, since apathy can be associated with these conditions, and to optimize antiparkinsonian medications for motor symptoms, motor fluctuations, and nonmotor fluctuations. Then, the investigational apathy treatments described in this section could be considered on an individual basis.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is seen throughout the disease course of PD in approximately 30% to 50% of patients.21 It can manifest as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders. There are no high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic treatments of anxiety specifically in patients with PD, except for a negative safety and tolerability study of buspirone in which one-half of patients experienced worsening motor symptoms.15,22 Thus, the treatment of anxiety in patients with PD is similar to treatments in the general population. SSRIs and SNRIs are typically considered first-line, benzodiazepines are sometimes used with caution (although cognitive adverse effects and fall risk need to be considered), and nonpharmacologic treatments such as mindfulness yoga, exercise, CBT, and psychotherapy can be effective.16,21,23

Continue to: Because there is the lack...

Because there is the lack of evidence-based treatments for anxiety in PD, we highlight 2 PD-specific anxiety disorders: internal tremor, and nonmotor “off” anxiety.

Internal tremor

Internal tremor is a sense of vibration in the axial and/or appendicular muscles that cannot be seen externally by the patient or examiner. It is not yet fully understood if this phenomenon is sensory, anxiety-related, related to subclinical tremor, or the result of a combination of these factors (ie, sensory awareness of a subclinical tremor that triggers or is worsened by anxiety). There is some evidence for subclinical tremor on electromyography, but internal tremor does not respond to antiparkinsonian medications in 70% of patients.24 More electrophysiological research is needed to clarify this phenomenon. Internal tremor has been associated with anxiety in 64% of patients and often improves with anxiolytic therapies.24

Although poorly understood, internal tremor is a documented phenomenon in 33% to 44% of patients with PD, and in some cases, it may be an initial symptom that motivates a patient to seek medical attention for the first time.24,25 Internal tremor has also been reported in patients with essential tremor and multiple sclerosis.25 Therefore, physicians should be aware of internal tremor because this symptom could herald an underlying neurological disease.

Nonmotor ‘off’ anxiety

Patients with PD are commonly prescribed carbidopa-levodopa, a dopamine precursor, at least 3 times daily. Initially, this medication controls motor symptoms well from 1 dose to the next. However, as the disease progresses, some patients report motor fluctuations in which an individual dose of carbidopa-levodopa may wear off early, take longer than usual to take effect, or not take effect at all. Patients describe these periods as an “off” state in which they do not feel their medications are working. Such motor fluctuations can lead to anxiety and avoidance behaviors, because patients fear being in public at times when the medication does not adequately control their motor symptoms.

In addition to these motor symptom fluctuations and related anxiety, patients can also experience nonmotor symptom fluctuations. A wide variety of nonmotor symptoms, such as mood, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms, have been reported to fluctuate in parallel with motor symptoms.26,27 One study reported fluctuating restlessness in 39% of patients with PD, excessive worry in 17%, shortness of breath in 13%, excessive sweating and fear in 12%, and palpitations in 10%.27 A patient with fluctuating shortness of breath, sweating, and palpitations (for example) may repeatedly present to the emergency department with a negative cardiac workup and eventually be diagnosed with panic disorder, whereas the patient is truly experiencing nonmotor “off” symptoms. Thus, it is important to be aware of nonmotor fluctuations so this diagnosis can be made and the symptoms appropriately treated. The first step in treating nonmotor fluctuations is to optimize the antiparkinsonian regimen to minimize fluctuations. If “off” anxiety symptoms persist, anxiolytic medications can be prescribed.21

Continue to: Psychosis

Psychosis

Psychosis can occur in prodromal and early PD but is most common in advanced PD.28 One study reported that 60% of patients developed hallucinations or delusions after 12 years of follow-up.29 Disease duration, disease severity, dementia, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are significant risk factors for psychosis in PD.30 Well-formed visual hallucinations are the most common manifestation of psychosis in patients with PD. Auditory hallucinations and delusions are less common. Delusions are usually seen in patients with dementia and are often paranoid delusions, such as of spousal infidelity.30 Sensory hallucinations can occur, but should not be mistaken with formication, a central pain syndrome in PD that can represent a nonmotor “off” symptom that may respond to dopaminergic medication.31 Other more mild psychotic symptoms include illusions or misinterpretation of stimuli, false sense of presence, and passage hallucinations of fleeting figures in the peripheral vision.30

The pathophysiology of PD psychosis is not entirely understood but differs from psychosis in other disorders. It can occur in the absence of antiparkinsonian medication exposure and is thought to be a consequence of the underlying disease process of PD involving neurodegeneration in certain brain regions and aberrant neurotransmission of not only dopamine but also serotonin, acetylcholine, and glutamate.30

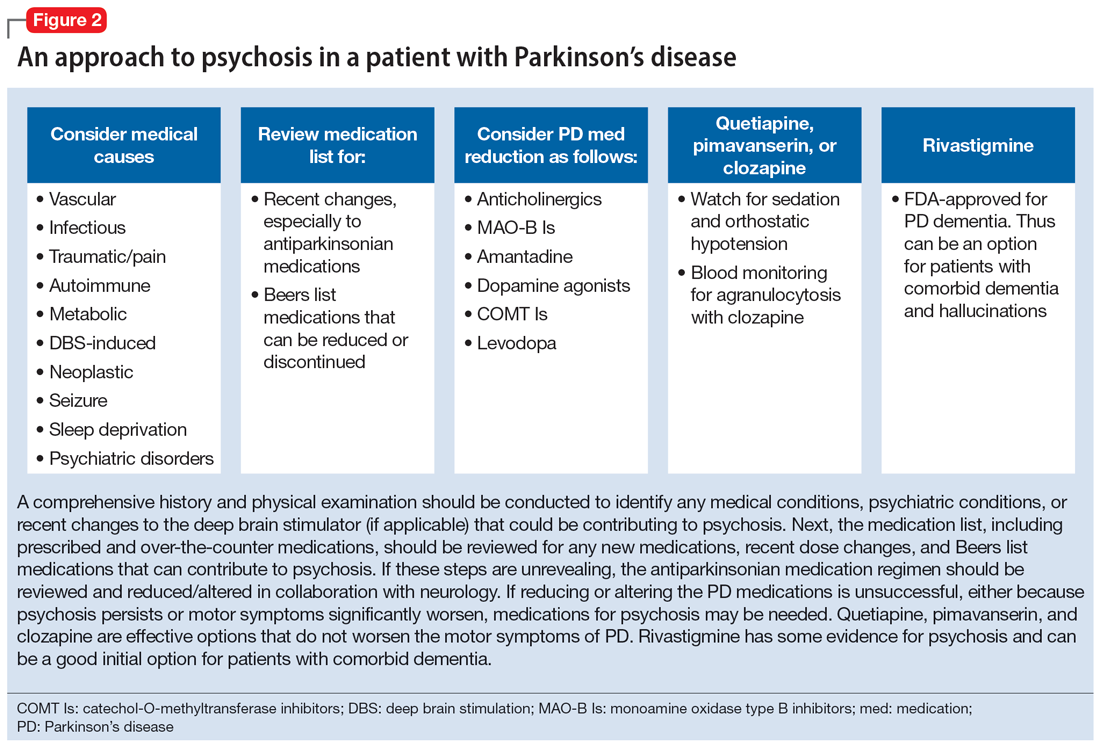

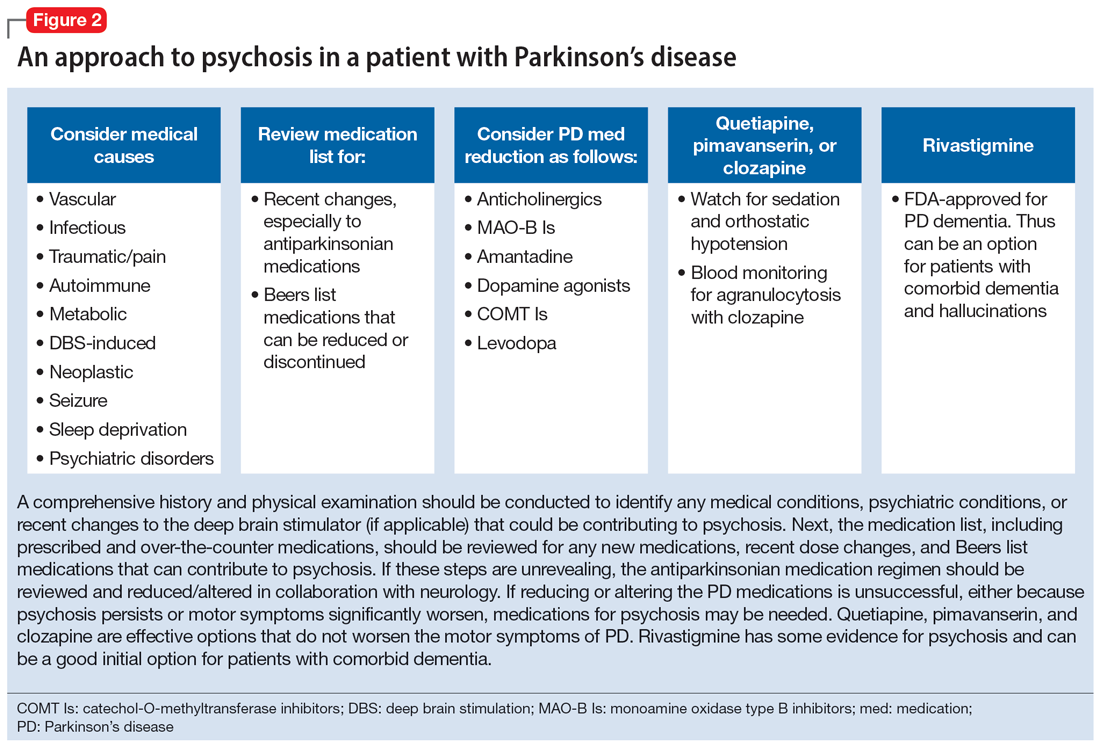

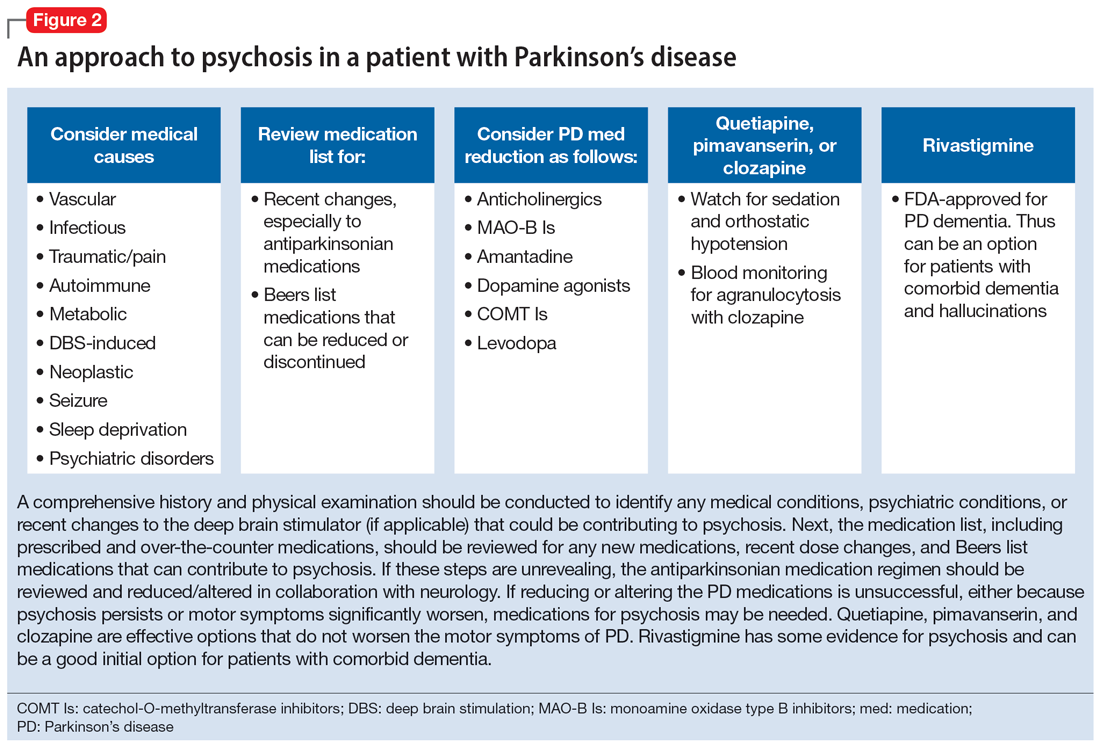

Figure 2 outlines the management of psychosis in PD. After addressing medical and medication-related causes, it is important to determine if the psychotic symptom is sufficiently bothersome to and/or potentially dangerous for the patient to warrant treatment. If treatment is indicated, pimavanserin and clozapine are efficacious for psychosis in PD without worsening motor symptoms, and quetiapine is possibly efficacious with a low risk of worsening motor symptoms.15 Other antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol, can substantially worsen motor symptoms.15 Both second-generation antipsychotics and pimavanserin have an FDA black-box warning for a higher risk of all-cause mortality in older patients with dementia; however, because psychosis is associated with early mortality in PD, the risk/benefit ratio should be discussed with the patient and family for shared decision-making.30 If the patient also has dementia, rivastigmine—which is FDA-approved for PD dementia (PDD)—may also improve hallucinations.32

Cognitive disorders

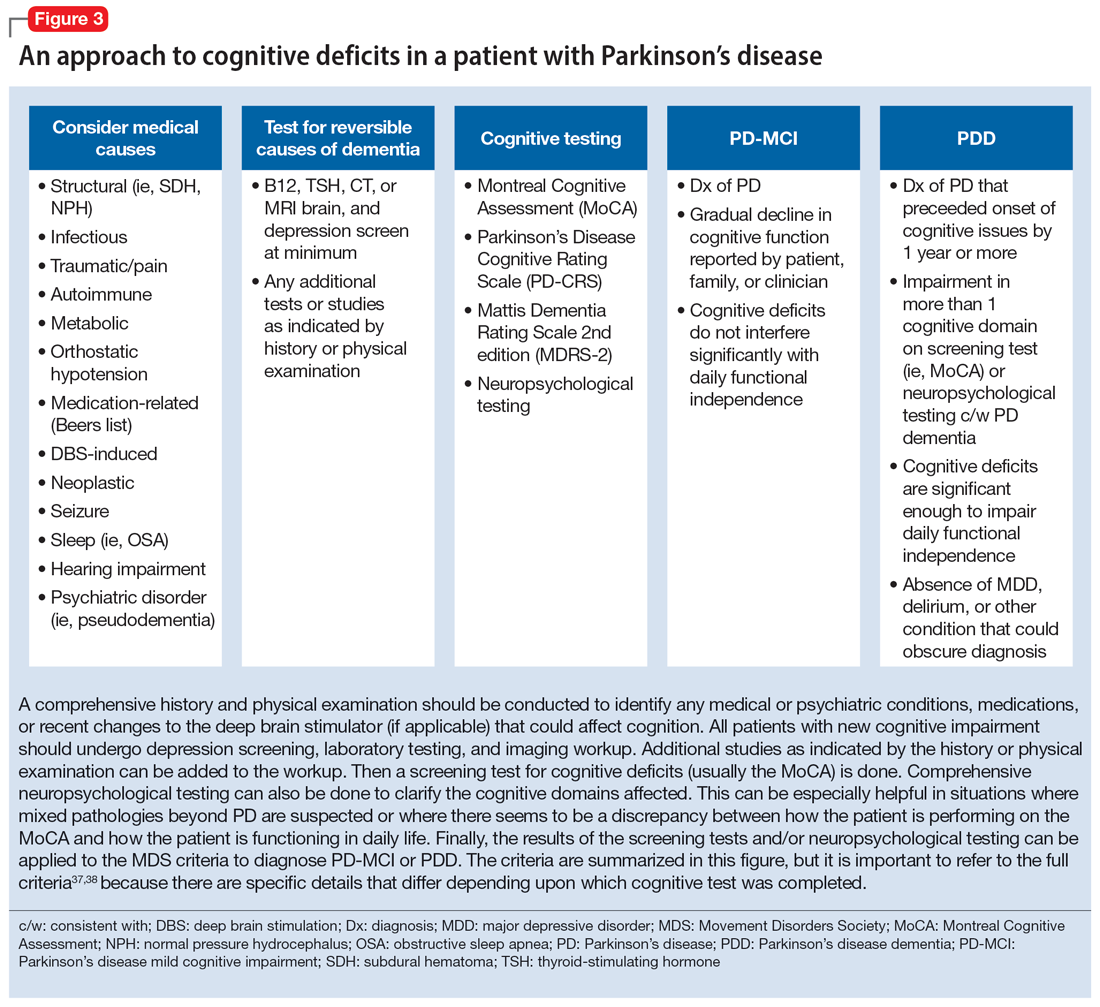

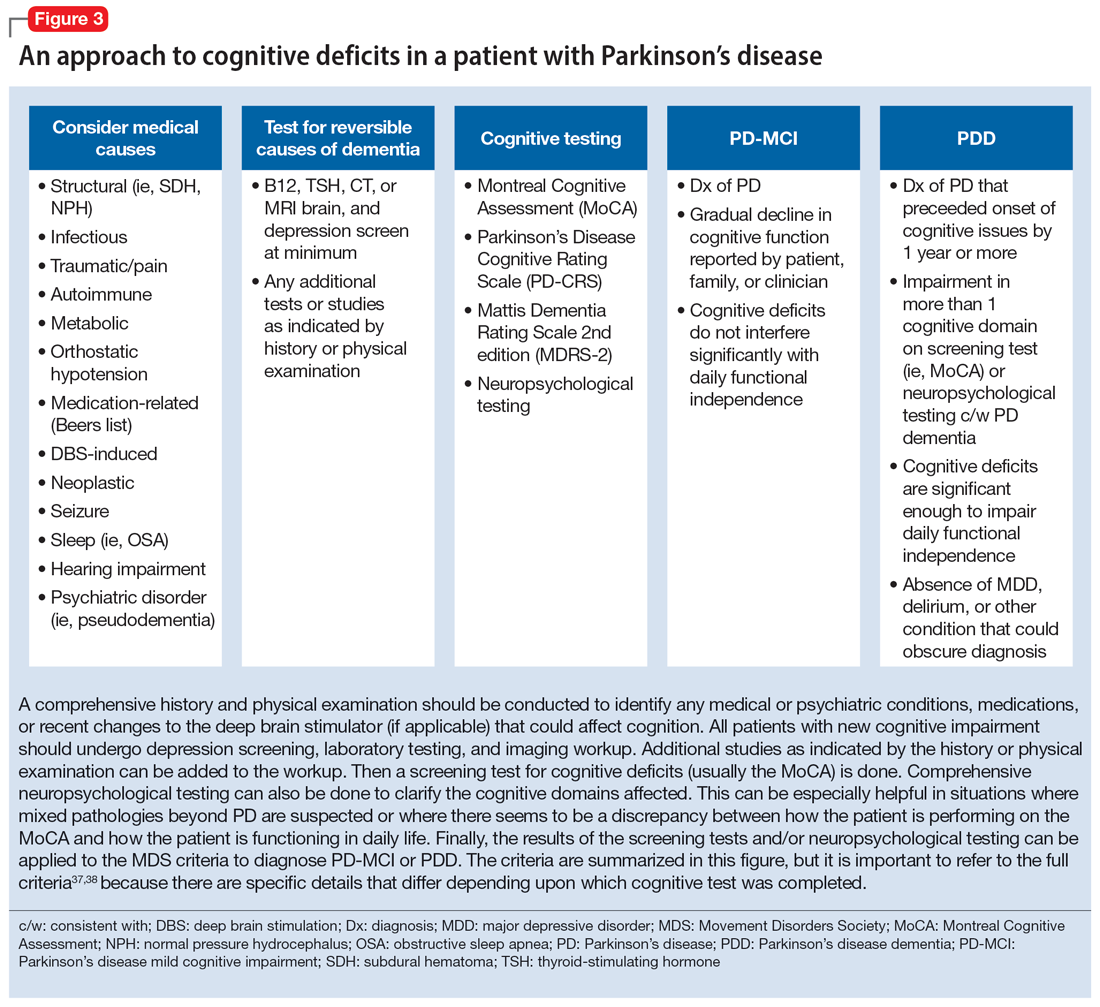

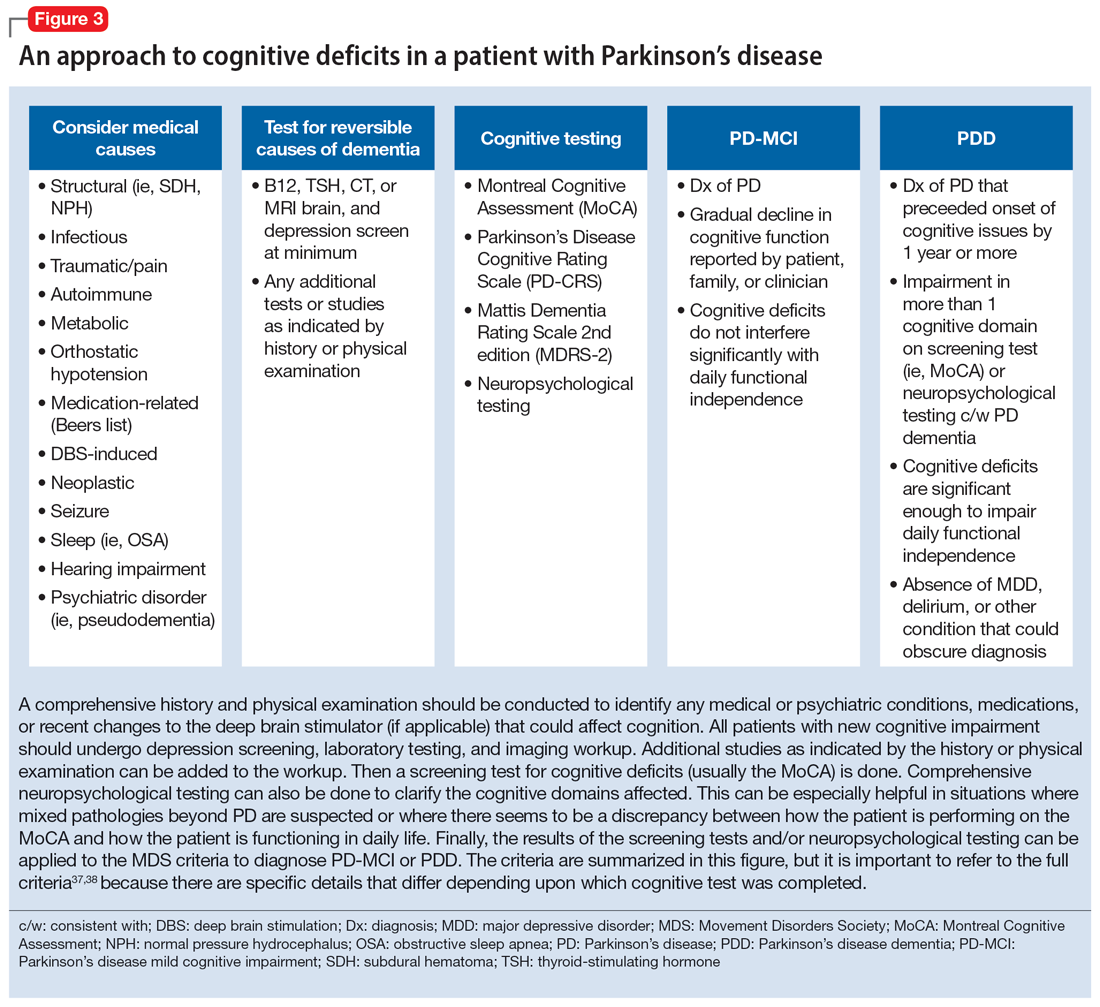

This section focuses on PD mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) and PDD. When a patient with PD reports cognitive concerns, the approach outlined in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder. A detailed history, medication review, and physical examination can identify any medical or psychiatric conditions that could affect cognition. The American Academy of Neurology recommends screening for depression, obtaining blood levels of vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone, and obtaining a CT or MRI of the brain to rule out reversible causes of dementia.33 A validated screening test such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which has higher sensitivity for PD-MCI than the Mini-Mental State Examination, is used to identify and quantify cognitive impairment.34 Neuropsychological testing is the gold standard and can be used to confirm and/or better quantify the degree and domains of cognitive impairment.35 Typically, cognitive deficits in PD affect executive function, attention, and/or visuospatial domains more than memory and language early on, and deficits in visuospatial and language domains have the highest sensitivity for predicting progression to PDD.36

Once reversible causes of dementia are addressed or ruled out and cognitive testing is completed, the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) criteria for PD-MCI and PDD summarized in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder.37,38 The MDS criteria for PDD require a diagnosis of PD for ≥1 year prior to the onset of dementia to differentiate PDD from dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). If the dementia starts within 1 year of the onset of parkinsonism, the diagnosis would be DLB. PDD and DLB are on the spectrum of Lewy body dementia, with the same Lewy body pathology in different temporal and spatial distributions in the brain.38

Continue to: PD-MCI is present in...

PD-MCI is present in approximately 25% of patients.35 PD-MCI does not always progress to dementia but increases the risk of dementia 6-fold. The prevalence of PDD increases with disease duration; it is present in approximately 50% of patients at 10 years and 80% of patients at 20 years of disease.35 Rivastigmine is the only FDA-approved medication to slow progression of PDD. There is insufficient evidence for other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.15 Unfortunately, RCTs of pharmacotherapy for PD-MCI have failed to show efficacy. However, exercise, cognitive rehabilitation, and neuromodulation are being studied. In the meantime, addressing modifiable risk factors (such as vascular risk factors and alcohol consumption) and treating comorbid orthostatic hypotension, obstructive sleep apnea, and depression may improve cognition.35,39

Treatment-related disorders

Impulse control disorders

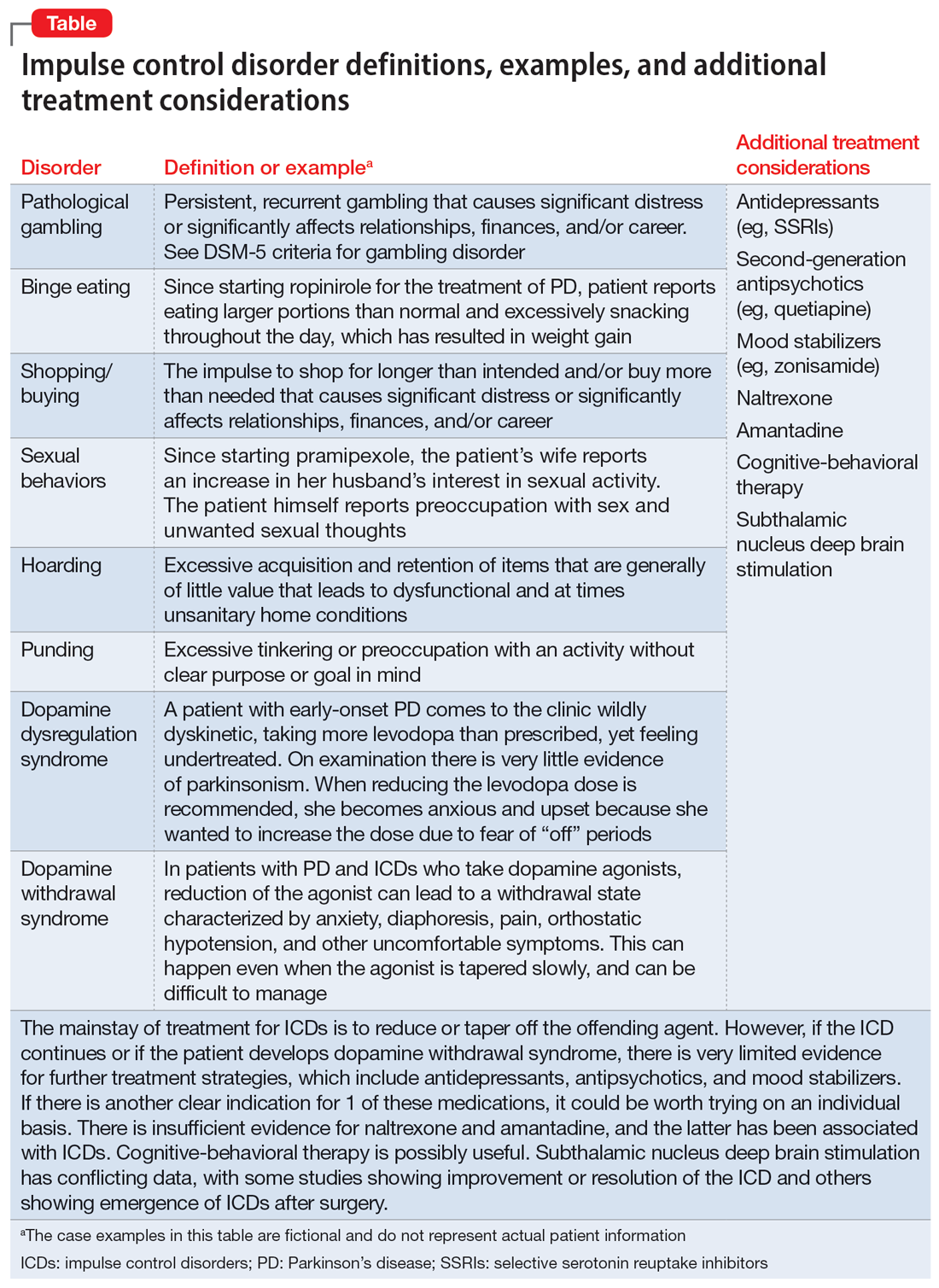

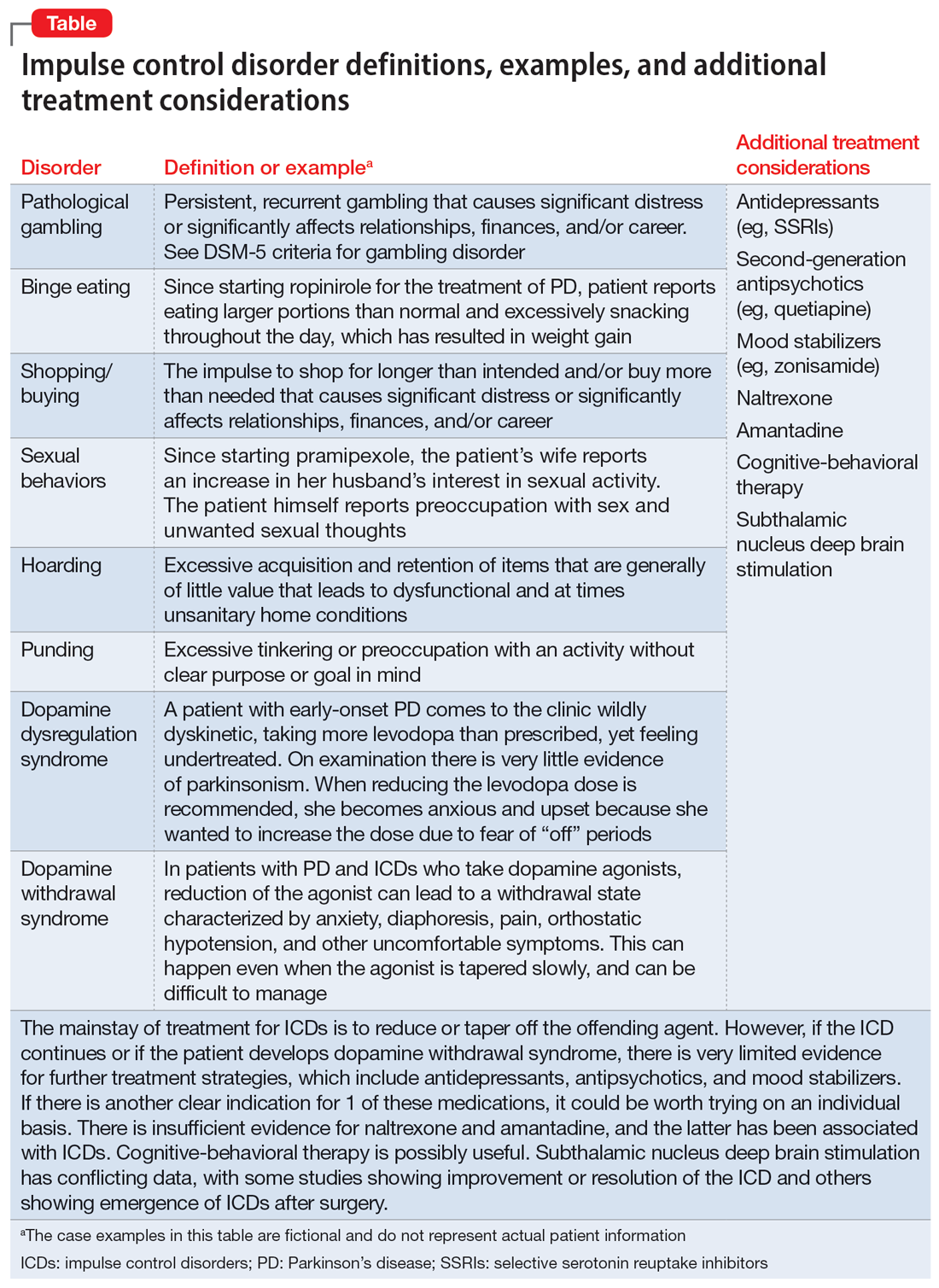

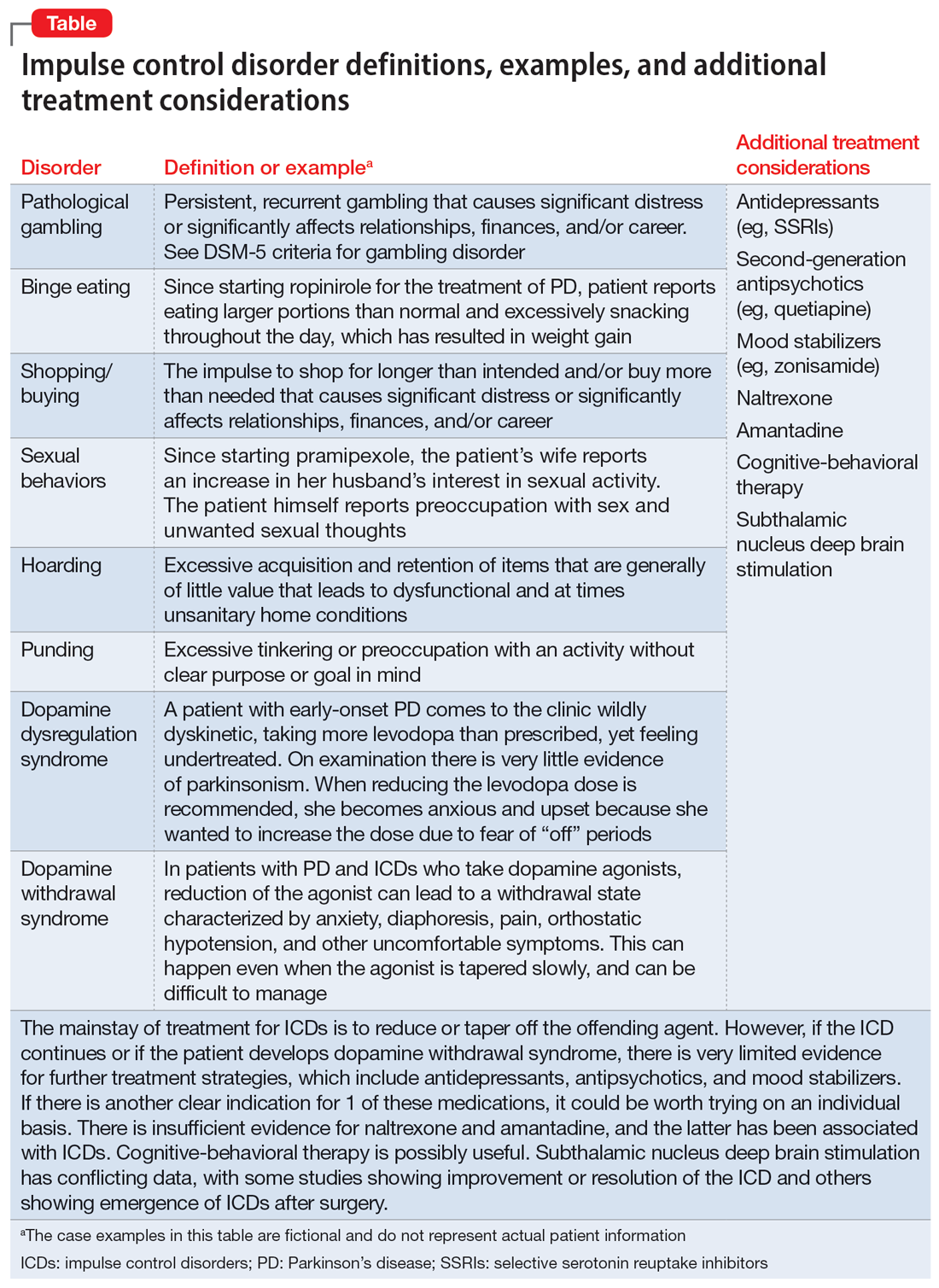

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) are an important medication-related consideration in patients with PD. The ICDs seen in PD include pathological gambling, binge eating, excessive shopping, hypersexual behaviors, and dopamine dysregulation syndrome (Table). These disorders are more common in younger patients with a history of impulsive personality traits and addictive behaviors (eg, history of tobacco or alcohol abuse), and are most strongly associated with dopaminergic therapies, particularly the dopamine agonists.40,41 In the DOMINION study, the odds of ICDs were 2- to 3.5-fold higher in patients taking dopamine agonists.42 This is mainly thought to be due to stimulation of D2/D3 receptors in the mesolimbic system.40 High doses of levodopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and amantadine are also associated with ICDs.40-42

The first step in managing ICDs is diagnosing them, which can be difficult because patients often are not forthcoming about these problems due to embarrassment or failure to recognize that the ICD is related to PD medications. If a family member accompanies the patient at the visit, the patient may not want to disclose the amount of money they spend or the extent to which the behavior is a problem. Thus, a screening questionnaire, such as the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease (QUIP) can be a helpful way for patients to alert the clinician to the issue.41 Education for the patient and family is crucial before the ICD causes significant financial, health, or relationship problems.

The mainstay of treatment is to reduce or taper off the dopamine agonist or other offending agent while monitoring for worsening motor symptoms and dopamine withdrawal syndrome. If this is unsuccessful, there is very limited evidence for further treatment strategies (Table), including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.40,43,44 There is insufficient evidence for naltrexone based on an RCT that failed to meet its primary endpoint, although naltrexone did significantly reduce QUIP scores.15,44 There is also insufficient evidence for amantadine, which showed benefit in some studies but was associated with ICDs in the DOMINION study.15,40,42 In terms of nonpharmacologic treatments, CBT is likely efficacious.15,40 There are mixed results for STN DBS. Some studies showed improvement in the ICD, due at least in part to dopaminergic medication reduction postoperatively, but this treatment has also been reported to increase impulsivity.40,45

Deep brain stimulation–related disorders

For patients with PD, the ideal lead location for STN DBS is the dorsolateral aspect of the STN, as this is the motor region of the nucleus. The STN functions in indirect and hyperdirect pathways to put the brake on certain motor programs so only the desired movement can be executed. Its function is clinically demonstrated by patients with STN stroke who develop excessive ballistic movements. Adjacent to the motor region of the STN is a centrally located associative region and a medially located limbic region. Thus, when stimulating the dorsolateral STN, current can spread to those regions as well, and the STN’s ability to put the brake on behavioral and emotional programs can be affected.46 Stimulation of the STN has been associated with mania, euphoria, new-onset ICDs, decreased verbal fluency, and executive dysfunction. Depression, apathy, and anxiety can also occur, but more commonly result from rapid withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications after DBS surgery.46,47 Therefore, for PD patients with DBS with new or worsening psychiatric or cognitive symptoms, it is important to inquire about any recent programming sessions with neurology as well as recent self-increases in stimulation by the patient using their controller. Collaboration with neurology is important to troubleshoot whether stimulation could be contributing to the patient’s psychiatric or cognitive symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Mood, anxiety, psychotic, and cognitive symptoms and disorders are common psychiatric manifestations associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD). In addition, patients with PD may experience impulsive control disorders and other symptoms related to treatments they receive for PD. Careful assessment and collaboration with neurology is crucial to alleviating the effects of these conditions.

Related Resources

- Weintraub D, Aarsland D, Chaudhuri KR, et al. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurology. 2022;21(1):89-102. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00330-6

- Goldman JG, Guerra CM. Treatment of nonmotor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease. Neurologic Clinics. 2020;38(2):269-292. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.12.003

- Castrioto A, Lhommee E, Moro E et al. Mood and behavioral effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2014;13(3):287-305. doi:10.1016/ S1474-4422(13)70294-1

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Memantine • Namenda

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • Vivitrol