User login

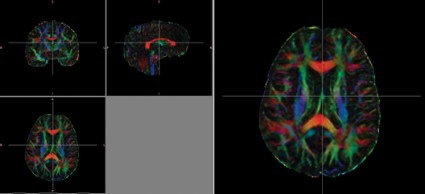

DTI detects long-term axonal injury in veterans with TBI

CHICAGO – Diffusion tensor imaging identified axonal damage in veterans more than 4 years after a blast-related traumatic brain injury in a phase I/II study.

None of the veterans had abnormalities on conventional CT or MRI, Thomas M. Malone reported at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Prior studies have shown that diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) identified white matter injuries in the middle cerebellar peduncles, cingulum bundles, and right orbitofrontal region of asymptomatic veterans with mild TBI less than 90 days post injury (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2091-100).

However, another study showed that the correlation between DTI findings and neuropsychological symptoms in the acute phase was inconsistent at 2.5 years (J. Neurotrauma 2010;27:683-94).

In the phase I portion of the current study, 10 veterans with blast-related mild TBI were evaluated at an average of 51.3 months after injury, along with 10 healthy controls.

Despite having normal findings on CT and MR imaging, veterans had significantly higher average DTI-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values than did controls in the right posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.739 vs. 0.706; P less than .05) and left posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.777 vs. 0.716; P less than .05). FA values were similar between groups in the anterior limbs of the internal capsule and genu and splenium of the corpus callosum. These higher FA values differ from results found in DTI studies conducted during the acute phase of blast-related mild TBI, said Mr. Malone of St. Louis University.

Overall, veterans scored significantly lower than did controls on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), immediate memory index (81.6 vs. 99.8; P less than .01), visual-constructional index (82.9 vs. 100.2; P less than .05), and delayed memory index (81.5 vs. 97.4; P less than .05).

Significant correlations were found between internal capsule FA values and neuropsychological tests measuring attention, memory, and motor functioning, including the RBANS and grooved pegboard test, Mr. Malone said.

For the phase II portion of the study, the investigators increased the cohort to 21 mild TBI and 8 moderate TBI veterans and 19 healthy controls, and removed outliers with FA values more than 2 standard deviations above or below the mean.

In this analysis, average FA values were significantly lower in the splenium of the corpus callosum among veterans than in controls (0.777 vs. 0.79; P less than .05).

"Decreased FA values among the TBI group are perhaps indicative of fiber damage and may explain the chronic deficits observed in mild blast injuries," Mr. Malone said.

Recovery from long-term axonal injury is possible, but the brain has somewhat limited capabilities in repairing itself, said senior author Dr. Richard Bucholz, professor and vice chair of neurosurgery at St. Louis University.

"My general feeling is if it doesn’t repair at 51 months, it probably never repairs," he said in an interview.

Although DTI findings of long-term axonal injury have important implications in terms of rehabilitation and continued problems associated with TBI injuries, both men urged caution in interpreting the results.

"I wouldn’t want to sell this as a diagnostic test," Mr. Malone said in a press briefing. "These were between-group differences."

Future studies will require larger numbers of veterans and the use of more robust preprocessing software such as Tortoise from the National Institutes of Health, automated segmentation, and voxel-based morphometry analysis.

Mr. Malone and his coauthors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Diffusion tensor imaging identified axonal damage in veterans more than 4 years after a blast-related traumatic brain injury in a phase I/II study.

None of the veterans had abnormalities on conventional CT or MRI, Thomas M. Malone reported at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Prior studies have shown that diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) identified white matter injuries in the middle cerebellar peduncles, cingulum bundles, and right orbitofrontal region of asymptomatic veterans with mild TBI less than 90 days post injury (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2091-100).

However, another study showed that the correlation between DTI findings and neuropsychological symptoms in the acute phase was inconsistent at 2.5 years (J. Neurotrauma 2010;27:683-94).

In the phase I portion of the current study, 10 veterans with blast-related mild TBI were evaluated at an average of 51.3 months after injury, along with 10 healthy controls.

Despite having normal findings on CT and MR imaging, veterans had significantly higher average DTI-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values than did controls in the right posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.739 vs. 0.706; P less than .05) and left posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.777 vs. 0.716; P less than .05). FA values were similar between groups in the anterior limbs of the internal capsule and genu and splenium of the corpus callosum. These higher FA values differ from results found in DTI studies conducted during the acute phase of blast-related mild TBI, said Mr. Malone of St. Louis University.

Overall, veterans scored significantly lower than did controls on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), immediate memory index (81.6 vs. 99.8; P less than .01), visual-constructional index (82.9 vs. 100.2; P less than .05), and delayed memory index (81.5 vs. 97.4; P less than .05).

Significant correlations were found between internal capsule FA values and neuropsychological tests measuring attention, memory, and motor functioning, including the RBANS and grooved pegboard test, Mr. Malone said.

For the phase II portion of the study, the investigators increased the cohort to 21 mild TBI and 8 moderate TBI veterans and 19 healthy controls, and removed outliers with FA values more than 2 standard deviations above or below the mean.

In this analysis, average FA values were significantly lower in the splenium of the corpus callosum among veterans than in controls (0.777 vs. 0.79; P less than .05).

"Decreased FA values among the TBI group are perhaps indicative of fiber damage and may explain the chronic deficits observed in mild blast injuries," Mr. Malone said.

Recovery from long-term axonal injury is possible, but the brain has somewhat limited capabilities in repairing itself, said senior author Dr. Richard Bucholz, professor and vice chair of neurosurgery at St. Louis University.

"My general feeling is if it doesn’t repair at 51 months, it probably never repairs," he said in an interview.

Although DTI findings of long-term axonal injury have important implications in terms of rehabilitation and continued problems associated with TBI injuries, both men urged caution in interpreting the results.

"I wouldn’t want to sell this as a diagnostic test," Mr. Malone said in a press briefing. "These were between-group differences."

Future studies will require larger numbers of veterans and the use of more robust preprocessing software such as Tortoise from the National Institutes of Health, automated segmentation, and voxel-based morphometry analysis.

Mr. Malone and his coauthors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Diffusion tensor imaging identified axonal damage in veterans more than 4 years after a blast-related traumatic brain injury in a phase I/II study.

None of the veterans had abnormalities on conventional CT or MRI, Thomas M. Malone reported at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Prior studies have shown that diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) identified white matter injuries in the middle cerebellar peduncles, cingulum bundles, and right orbitofrontal region of asymptomatic veterans with mild TBI less than 90 days post injury (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2091-100).

However, another study showed that the correlation between DTI findings and neuropsychological symptoms in the acute phase was inconsistent at 2.5 years (J. Neurotrauma 2010;27:683-94).

In the phase I portion of the current study, 10 veterans with blast-related mild TBI were evaluated at an average of 51.3 months after injury, along with 10 healthy controls.

Despite having normal findings on CT and MR imaging, veterans had significantly higher average DTI-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values than did controls in the right posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.739 vs. 0.706; P less than .05) and left posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.777 vs. 0.716; P less than .05). FA values were similar between groups in the anterior limbs of the internal capsule and genu and splenium of the corpus callosum. These higher FA values differ from results found in DTI studies conducted during the acute phase of blast-related mild TBI, said Mr. Malone of St. Louis University.

Overall, veterans scored significantly lower than did controls on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), immediate memory index (81.6 vs. 99.8; P less than .01), visual-constructional index (82.9 vs. 100.2; P less than .05), and delayed memory index (81.5 vs. 97.4; P less than .05).

Significant correlations were found between internal capsule FA values and neuropsychological tests measuring attention, memory, and motor functioning, including the RBANS and grooved pegboard test, Mr. Malone said.

For the phase II portion of the study, the investigators increased the cohort to 21 mild TBI and 8 moderate TBI veterans and 19 healthy controls, and removed outliers with FA values more than 2 standard deviations above or below the mean.

In this analysis, average FA values were significantly lower in the splenium of the corpus callosum among veterans than in controls (0.777 vs. 0.79; P less than .05).

"Decreased FA values among the TBI group are perhaps indicative of fiber damage and may explain the chronic deficits observed in mild blast injuries," Mr. Malone said.

Recovery from long-term axonal injury is possible, but the brain has somewhat limited capabilities in repairing itself, said senior author Dr. Richard Bucholz, professor and vice chair of neurosurgery at St. Louis University.

"My general feeling is if it doesn’t repair at 51 months, it probably never repairs," he said in an interview.

Although DTI findings of long-term axonal injury have important implications in terms of rehabilitation and continued problems associated with TBI injuries, both men urged caution in interpreting the results.

"I wouldn’t want to sell this as a diagnostic test," Mr. Malone said in a press briefing. "These were between-group differences."

Future studies will require larger numbers of veterans and the use of more robust preprocessing software such as Tortoise from the National Institutes of Health, automated segmentation, and voxel-based morphometry analysis.

Mr. Malone and his coauthors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT RSNA 2013

Major finding: Veterans had significantly higher average diffusion tensor imaging–derived fractional anisotropy values than did healthy controls in the right posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.739 vs. 0.706; P less than .05) and left posterior limb of the internal capsule (0.777 vs. 0.716; P less than .05)

Data source: A retrospective phase I/II study in 39 veterans with traumatic brain injury and 29 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Mr. Malone and his coauthors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Trauma surgeons placed intracranial pressure monitors safely

SAN FRANCISCO – Complications developed with 3% of 298 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by trauma surgeons and with 0.8% of 112 monitors placed by neurosurgeons in patients with traumatic brain injury, a statistically insignificant difference.

Mortality rates were 37% for patients in the trauma surgeon group and 30% for patients in the neurosurgeon group, a difference that also was not significant, Dr. Sadia Ilyas and her associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

They retrospectively studied data for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received intracranial pressure monitors in 2006 through 2011 at one Level I trauma center. The trauma surgeons there had undergone training and credentialing in 2005 by neurosurgeons at the same facility for insertion of the monitors because neurosurgery coverage is not always available, explained Dr. Ilyas of Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Complications in this series consisted of device malfunction or dislodgement, with no major or life-threatening complications.

Trauma surgeons in the training program each viewed two 10-minute instructional videos, were proctored by a neurosurgeon in a cadaver lab, and placed three monitors in patients under proctoring by a neurosurgeon. General surgery residents received similar training but were not credentialed to place intracranial pressure monitors without direct supervision.

Guidelines from the Brain Trauma Foundation recommend intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with severe TBI who have a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 or lower and an abnormal CT scan. Monitoring typically involves placement of a ventriculostomy or an intracranial pressure intraparenchymal monitor (bolt monitor).

In the study, 97% of all monitors placed were parenchymal monitors. Among those placed by neurosurgeons, 12% were ventriculostomies, which have the added advantage of therapeutic use but are more challenging to insert. "It is our view that placement of ICP parenchymal monitors is a more reasonable alternative for non-neurosurgeons," she said.

Six previous studies of 904 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by non-neurosurgeons found complication rates of 0%-8% with parenchymal monitors and 15% with ventriculostomy.

Each year in the United States approximately 200,000 people are hospitalized for TBI and 50,000 die from TBI. In 2010, an estimated 4,400 neurosurgeons were actively practicing in the United States (1.4 for every 100,000 residents), not all practiced trauma care, and a third were older than 55 years, she said.

Dr. Ilyas reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

These results have essentially been published before in other studies, and this paper doesn’t break any new ground.

I want to drive home the point that it is important, at least in my practice, to try to use ventriculostomy as the first line of monitoring because you can use it as a therapeutic tool to drain cerebrospinal fluid as well as just monitor. I do use parenchymal monitors but I can’t cannulate the ventricle.

A bigger issue is what to do with the information that you get from these monitors. Regardless of who puts these things in, someone needs to know how to treat the patients. Personally, I’ve been dismayed by the trend in recent years for so-called neuro critical care doctors to focus on things like temperature and serum sodium. It seems like very few intensivists who care for TBI patients really understand cerebral metabolism, cerebral blood flow, cerebral pathophysiology, and related processes.

As Dr. Ilyas and her colleagues have shown, the technical insertion of these devices is really not that difficult, but knowing the indications for when to put them in and when not to put them in, knowing how to interpret the data, and integrating the care of these patients into the neuro service are much more difficult things to do.

One problem with this paper is that it describes only short-term periprocedural complications. The real standard for measuring efficacy of interventions in TBI patients is long-term follow-up, which historically has been 6 months from injury and now more recent trials are using 12 months or even longer.

Dr. Alex B. Valadka is a neurosurgeon at the Seton Brain and Spine Institute, Austin, Tex. These are excerpts of his remarks as discussant of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

These results have essentially been published before in other studies, and this paper doesn’t break any new ground.

I want to drive home the point that it is important, at least in my practice, to try to use ventriculostomy as the first line of monitoring because you can use it as a therapeutic tool to drain cerebrospinal fluid as well as just monitor. I do use parenchymal monitors but I can’t cannulate the ventricle.

A bigger issue is what to do with the information that you get from these monitors. Regardless of who puts these things in, someone needs to know how to treat the patients. Personally, I’ve been dismayed by the trend in recent years for so-called neuro critical care doctors to focus on things like temperature and serum sodium. It seems like very few intensivists who care for TBI patients really understand cerebral metabolism, cerebral blood flow, cerebral pathophysiology, and related processes.

As Dr. Ilyas and her colleagues have shown, the technical insertion of these devices is really not that difficult, but knowing the indications for when to put them in and when not to put them in, knowing how to interpret the data, and integrating the care of these patients into the neuro service are much more difficult things to do.

One problem with this paper is that it describes only short-term periprocedural complications. The real standard for measuring efficacy of interventions in TBI patients is long-term follow-up, which historically has been 6 months from injury and now more recent trials are using 12 months or even longer.

Dr. Alex B. Valadka is a neurosurgeon at the Seton Brain and Spine Institute, Austin, Tex. These are excerpts of his remarks as discussant of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

These results have essentially been published before in other studies, and this paper doesn’t break any new ground.

I want to drive home the point that it is important, at least in my practice, to try to use ventriculostomy as the first line of monitoring because you can use it as a therapeutic tool to drain cerebrospinal fluid as well as just monitor. I do use parenchymal monitors but I can’t cannulate the ventricle.

A bigger issue is what to do with the information that you get from these monitors. Regardless of who puts these things in, someone needs to know how to treat the patients. Personally, I’ve been dismayed by the trend in recent years for so-called neuro critical care doctors to focus on things like temperature and serum sodium. It seems like very few intensivists who care for TBI patients really understand cerebral metabolism, cerebral blood flow, cerebral pathophysiology, and related processes.

As Dr. Ilyas and her colleagues have shown, the technical insertion of these devices is really not that difficult, but knowing the indications for when to put them in and when not to put them in, knowing how to interpret the data, and integrating the care of these patients into the neuro service are much more difficult things to do.

One problem with this paper is that it describes only short-term periprocedural complications. The real standard for measuring efficacy of interventions in TBI patients is long-term follow-up, which historically has been 6 months from injury and now more recent trials are using 12 months or even longer.

Dr. Alex B. Valadka is a neurosurgeon at the Seton Brain and Spine Institute, Austin, Tex. These are excerpts of his remarks as discussant of the study at the meeting. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Complications developed with 3% of 298 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by trauma surgeons and with 0.8% of 112 monitors placed by neurosurgeons in patients with traumatic brain injury, a statistically insignificant difference.

Mortality rates were 37% for patients in the trauma surgeon group and 30% for patients in the neurosurgeon group, a difference that also was not significant, Dr. Sadia Ilyas and her associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

They retrospectively studied data for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received intracranial pressure monitors in 2006 through 2011 at one Level I trauma center. The trauma surgeons there had undergone training and credentialing in 2005 by neurosurgeons at the same facility for insertion of the monitors because neurosurgery coverage is not always available, explained Dr. Ilyas of Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Complications in this series consisted of device malfunction or dislodgement, with no major or life-threatening complications.

Trauma surgeons in the training program each viewed two 10-minute instructional videos, were proctored by a neurosurgeon in a cadaver lab, and placed three monitors in patients under proctoring by a neurosurgeon. General surgery residents received similar training but were not credentialed to place intracranial pressure monitors without direct supervision.

Guidelines from the Brain Trauma Foundation recommend intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with severe TBI who have a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 or lower and an abnormal CT scan. Monitoring typically involves placement of a ventriculostomy or an intracranial pressure intraparenchymal monitor (bolt monitor).

In the study, 97% of all monitors placed were parenchymal monitors. Among those placed by neurosurgeons, 12% were ventriculostomies, which have the added advantage of therapeutic use but are more challenging to insert. "It is our view that placement of ICP parenchymal monitors is a more reasonable alternative for non-neurosurgeons," she said.

Six previous studies of 904 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by non-neurosurgeons found complication rates of 0%-8% with parenchymal monitors and 15% with ventriculostomy.

Each year in the United States approximately 200,000 people are hospitalized for TBI and 50,000 die from TBI. In 2010, an estimated 4,400 neurosurgeons were actively practicing in the United States (1.4 for every 100,000 residents), not all practiced trauma care, and a third were older than 55 years, she said.

Dr. Ilyas reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Complications developed with 3% of 298 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by trauma surgeons and with 0.8% of 112 monitors placed by neurosurgeons in patients with traumatic brain injury, a statistically insignificant difference.

Mortality rates were 37% for patients in the trauma surgeon group and 30% for patients in the neurosurgeon group, a difference that also was not significant, Dr. Sadia Ilyas and her associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

They retrospectively studied data for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received intracranial pressure monitors in 2006 through 2011 at one Level I trauma center. The trauma surgeons there had undergone training and credentialing in 2005 by neurosurgeons at the same facility for insertion of the monitors because neurosurgery coverage is not always available, explained Dr. Ilyas of Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Complications in this series consisted of device malfunction or dislodgement, with no major or life-threatening complications.

Trauma surgeons in the training program each viewed two 10-minute instructional videos, were proctored by a neurosurgeon in a cadaver lab, and placed three monitors in patients under proctoring by a neurosurgeon. General surgery residents received similar training but were not credentialed to place intracranial pressure monitors without direct supervision.

Guidelines from the Brain Trauma Foundation recommend intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with severe TBI who have a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 or lower and an abnormal CT scan. Monitoring typically involves placement of a ventriculostomy or an intracranial pressure intraparenchymal monitor (bolt monitor).

In the study, 97% of all monitors placed were parenchymal monitors. Among those placed by neurosurgeons, 12% were ventriculostomies, which have the added advantage of therapeutic use but are more challenging to insert. "It is our view that placement of ICP parenchymal monitors is a more reasonable alternative for non-neurosurgeons," she said.

Six previous studies of 904 intracranial pressure monitors inserted by non-neurosurgeons found complication rates of 0%-8% with parenchymal monitors and 15% with ventriculostomy.

Each year in the United States approximately 200,000 people are hospitalized for TBI and 50,000 die from TBI. In 2010, an estimated 4,400 neurosurgeons were actively practicing in the United States (1.4 for every 100,000 residents), not all practiced trauma care, and a third were older than 55 years, she said.

Dr. Ilyas reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT THE AAST ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Complications developed with 3% of monitors placed by trauma surgeons and 0.8% placed by neurosurgeons.

Data source: Retrospective review of 410 patients with TBI who received intracranial pressure monitors in 2006-2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Ilyas reported having no financial disclosures.

No differences are seen in concussion risk, severity, by helmet brand

ORLANDO – A prospective comparison of three brands of football helmets and various types of mouth guards raises questions about manufacturers’ claims regarding protection against sport-related concussions, according to Dr. Alison Brooks.

During the 2012 football season, 115 of 1,332 (9%) football players from 36 high schools had 116 sport-related concussions (SRCs). More than half (52%) of the players wore Riddell helmets, 35% wore Schutt helmets, and 13% wore Xenith helmets. Thirty-nine percent of the helmets were purchased during 2011-2012, 33% during 2009-2010, and 28% during 2002-2008.

No difference was seen in the rate or severity (based on days lost) of sport-related concussion (SRC) by helmet type or helmet purchase year, Dr. Brooks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The incidence rates of SRC were 9.5, 8.1, and 6.7 for the Riddell, Schutt, and Xenith helmets, respectively, and the SRC rates by year purchased were 9.3, 7.9, and 8.8 for helmets purchased during 2011-2012, 2009-2010, and 2002-2008, respectively. Median days lost were 13.5, 13.0, and 13.5, respectively.

"Contrary to manufacturer claims, lower risk and severity of SRC were not associated with a specific helmet brand," Dr. Brooks said.

As for mouth guards, 61% of the players wore generic models provided by their school, and 39% wore specialized mouth guards custom fitted by a dental professional or specifically marketed to reduce SRC.

The SRC rate was actually higher for those who wore a specialized (12.7) or custom-fitted (11.3) mouth guard than for those who wore a generic mouth guard (6.4), Dr. Brooks said.

Students included in the study were 9th through 12th graders with a mean age of 15.9 years. The students – who completed a preseason demographic and injury questionnaire (with 171 reporting a concussion in the prior 12 months) – wore various models of the three football helmet brands. Athletic trainers recorded the incidence and severity of SRC throughout the football season.

Although limited by factors such as possible selection bias (as schools and players were aware of the study), and recall bias (with respect to previous concussion status), the findings are important, because about 40,000 SRCs occur in high school football players in the United States each year. Despite limited prospective data on how specific football helmets and mouth guards affect the incidence and severity of SRC, manufacturers often cite laboratory research – based on impact (drop) testing – showing that their brand and/or a specific model will lessen impact forces associated with SRC, and they often claim that players who use their equipment may have a reduced SRC risk, she said, noting that schools and parents may feel pressured to purchase newer, more expensive equipment.

The current findings suggest that caution should be used when considering these claims, Dr. Brooks said.

In an interview, she added, "These preliminary findings are important in helping parents and coaches understand that there is no compelling evidence that any particular helmet or mouth guard significantly reduces concussion risk."

Helmets and mouth guards are nonetheless effective for doing what they are designed to do – prevent skull fractures and intracranial bleeds and dental injuries – and are important pieces of equipment that need to be maintained in good condition, and be fit and worn properly. There is also always a role for trying to improve technology. However, it may not be possible to significantly reduce concussion risk using helmet technology, she said.

"I think focus could be better spent on rule enforcement and coaching education on tackling technique to limit/avoid contact to the head, perhaps limiting contact practices, and behavior change about the intent of tackling to injure or ‘punish’ the opponent," she added.

Dr. Brooks reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A prospective comparison of three brands of football helmets and various types of mouth guards raises questions about manufacturers’ claims regarding protection against sport-related concussions, according to Dr. Alison Brooks.

During the 2012 football season, 115 of 1,332 (9%) football players from 36 high schools had 116 sport-related concussions (SRCs). More than half (52%) of the players wore Riddell helmets, 35% wore Schutt helmets, and 13% wore Xenith helmets. Thirty-nine percent of the helmets were purchased during 2011-2012, 33% during 2009-2010, and 28% during 2002-2008.

No difference was seen in the rate or severity (based on days lost) of sport-related concussion (SRC) by helmet type or helmet purchase year, Dr. Brooks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The incidence rates of SRC were 9.5, 8.1, and 6.7 for the Riddell, Schutt, and Xenith helmets, respectively, and the SRC rates by year purchased were 9.3, 7.9, and 8.8 for helmets purchased during 2011-2012, 2009-2010, and 2002-2008, respectively. Median days lost were 13.5, 13.0, and 13.5, respectively.

"Contrary to manufacturer claims, lower risk and severity of SRC were not associated with a specific helmet brand," Dr. Brooks said.

As for mouth guards, 61% of the players wore generic models provided by their school, and 39% wore specialized mouth guards custom fitted by a dental professional or specifically marketed to reduce SRC.

The SRC rate was actually higher for those who wore a specialized (12.7) or custom-fitted (11.3) mouth guard than for those who wore a generic mouth guard (6.4), Dr. Brooks said.

Students included in the study were 9th through 12th graders with a mean age of 15.9 years. The students – who completed a preseason demographic and injury questionnaire (with 171 reporting a concussion in the prior 12 months) – wore various models of the three football helmet brands. Athletic trainers recorded the incidence and severity of SRC throughout the football season.

Although limited by factors such as possible selection bias (as schools and players were aware of the study), and recall bias (with respect to previous concussion status), the findings are important, because about 40,000 SRCs occur in high school football players in the United States each year. Despite limited prospective data on how specific football helmets and mouth guards affect the incidence and severity of SRC, manufacturers often cite laboratory research – based on impact (drop) testing – showing that their brand and/or a specific model will lessen impact forces associated with SRC, and they often claim that players who use their equipment may have a reduced SRC risk, she said, noting that schools and parents may feel pressured to purchase newer, more expensive equipment.

The current findings suggest that caution should be used when considering these claims, Dr. Brooks said.

In an interview, she added, "These preliminary findings are important in helping parents and coaches understand that there is no compelling evidence that any particular helmet or mouth guard significantly reduces concussion risk."

Helmets and mouth guards are nonetheless effective for doing what they are designed to do – prevent skull fractures and intracranial bleeds and dental injuries – and are important pieces of equipment that need to be maintained in good condition, and be fit and worn properly. There is also always a role for trying to improve technology. However, it may not be possible to significantly reduce concussion risk using helmet technology, she said.

"I think focus could be better spent on rule enforcement and coaching education on tackling technique to limit/avoid contact to the head, perhaps limiting contact practices, and behavior change about the intent of tackling to injure or ‘punish’ the opponent," she added.

Dr. Brooks reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A prospective comparison of three brands of football helmets and various types of mouth guards raises questions about manufacturers’ claims regarding protection against sport-related concussions, according to Dr. Alison Brooks.

During the 2012 football season, 115 of 1,332 (9%) football players from 36 high schools had 116 sport-related concussions (SRCs). More than half (52%) of the players wore Riddell helmets, 35% wore Schutt helmets, and 13% wore Xenith helmets. Thirty-nine percent of the helmets were purchased during 2011-2012, 33% during 2009-2010, and 28% during 2002-2008.

No difference was seen in the rate or severity (based on days lost) of sport-related concussion (SRC) by helmet type or helmet purchase year, Dr. Brooks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The incidence rates of SRC were 9.5, 8.1, and 6.7 for the Riddell, Schutt, and Xenith helmets, respectively, and the SRC rates by year purchased were 9.3, 7.9, and 8.8 for helmets purchased during 2011-2012, 2009-2010, and 2002-2008, respectively. Median days lost were 13.5, 13.0, and 13.5, respectively.

"Contrary to manufacturer claims, lower risk and severity of SRC were not associated with a specific helmet brand," Dr. Brooks said.

As for mouth guards, 61% of the players wore generic models provided by their school, and 39% wore specialized mouth guards custom fitted by a dental professional or specifically marketed to reduce SRC.

The SRC rate was actually higher for those who wore a specialized (12.7) or custom-fitted (11.3) mouth guard than for those who wore a generic mouth guard (6.4), Dr. Brooks said.

Students included in the study were 9th through 12th graders with a mean age of 15.9 years. The students – who completed a preseason demographic and injury questionnaire (with 171 reporting a concussion in the prior 12 months) – wore various models of the three football helmet brands. Athletic trainers recorded the incidence and severity of SRC throughout the football season.

Although limited by factors such as possible selection bias (as schools and players were aware of the study), and recall bias (with respect to previous concussion status), the findings are important, because about 40,000 SRCs occur in high school football players in the United States each year. Despite limited prospective data on how specific football helmets and mouth guards affect the incidence and severity of SRC, manufacturers often cite laboratory research – based on impact (drop) testing – showing that their brand and/or a specific model will lessen impact forces associated with SRC, and they often claim that players who use their equipment may have a reduced SRC risk, she said, noting that schools and parents may feel pressured to purchase newer, more expensive equipment.

The current findings suggest that caution should be used when considering these claims, Dr. Brooks said.

In an interview, she added, "These preliminary findings are important in helping parents and coaches understand that there is no compelling evidence that any particular helmet or mouth guard significantly reduces concussion risk."

Helmets and mouth guards are nonetheless effective for doing what they are designed to do – prevent skull fractures and intracranial bleeds and dental injuries – and are important pieces of equipment that need to be maintained in good condition, and be fit and worn properly. There is also always a role for trying to improve technology. However, it may not be possible to significantly reduce concussion risk using helmet technology, she said.

"I think focus could be better spent on rule enforcement and coaching education on tackling technique to limit/avoid contact to the head, perhaps limiting contact practices, and behavior change about the intent of tackling to injure or ‘punish’ the opponent," she added.

Dr. Brooks reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE AAP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Major finding: Sport-related concussion incidence rates were 9.5, 8.1, and 6.7 for the Riddell, Schutt, and Xenith helmets, respectively. SRC rates were 9.3, 7.9, and 8.8 for helmets by year purchased during 2011-2012, 2009-2010, and 2002-2008, respectively.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 1,332 high school football players.

Disclosures: Dr. Brooks reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Nerve growth factor gene therapy delivered safely in Alzheimer’s patients

SAN DIEGO – Delivery of a gene therapy viral vector designed to express only the gene for human growth factor to the nucleus basalis of Meynert in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease appears to be safe and feasible, results from a first-in-human trial demonstrated.

"There are significant deficiencies with the therapies that exist for treating the memory and cognitive impairments of Alzheimer’s disease," Raymond T. Bartus, Ph.D., said at the Clinical Trials Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease.

Currently available cholinesterase inhibitors "are nonselective and suffer from serious dose-limiting side effects," said Dr. Bartus, president of San Diego–based RTBioconsultants. "Their mechanism of action for cholinergic enhancement is suboptimal, and they do not repair neurons, protect against death, or truly restore lost neuronal function. While they work to some extent, they are modest in their level of efficacy and do not improve symptoms in all patients. Moreover, they do nothing to affect the disease progression."

Nerve growth factor neurotrophic therapy, he continued, "should overcome all of these deficiencies and therefore provide a more effective therapy, applying a variation of the cholinergic approach that has shown proof of concept." Decades of research in animal models suggest that nerve growth factor "has remarkable antiapoptotic (i.e., antideath) and reparative properties for certain neurons in the degenerative brain," Dr. Bartus said. "There are at least two major obstacles to apply this technology to Alzheimer’s disease. The first is, Alzheimer’s is an extremely complicated disease, so determining where to target the treatment is especially important. Targeting the cholinergic neurons is compelling because their degeneration is known to contribute significantly to the memory loss."

The second key challenge, he said, is the need for constant exposure to cholinergic neurons that comprise the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) while avoiding exposure to untargeted neuronal populations. This has proven very difficult in past efforts extending back 20 years. In the past decade, gene therapy combined with stereotactic surgery has emerged as a practical enabling technology to accomplish this. On this basis, Dr. Bartus and his associates at Ceregene (where he served as chief scientific officer for more than 10 years) developed a viral gene therapy vector bioengineered to express only the gene for human nerve growth factor (AAV2-NGF, or CERE-110).

"You can think of it as an off-the-shelf biopharmaceutical that when injected into the human brain will induce the target neurons to produce or express and secrete only nerve growth factor and therefore provide support to NBM cholinergic neurons," he explained. "Preclinical studies have demonstrated an orderly dose-response relationship with NGF restricted to targeted basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, and no side effects or toxicity, even after testing very high doses in animals. That was quite surprising and certainly welcome."

Dr. Bartus presented phase I clinical data from 10 patients aged 50-79 years with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who received one of three ascending doses of AAV2-NGF via bilateral stereotactic injection into the nucleus basalis of Meynert: dose A (1.2 x 1010 viral genomes), dose B (5.8 x 1010 viral genomes; five times more than dose A), and dose C (1.2 x 1011 viral genomes; two times more than dose B). Patients were followed at 24 months for safety and feasibility and preliminary efficacy as measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months; autopsy tissue; and validated neuropsychological tests that included the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive (ADAS-Cog). Computer graphic software was used to provide a 3-D model of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in an effort to "determine where to distribute CERE-110 in the NBM and how much should be given to achieve optimal NGF exposure."

Dr. Bartus reported that AAV2-NGF was safe and well tolerated through 24 months. Adverse events and serious adverse events "were uneventful," he said. "What you see is a profile that reflects either incidental or unrelated events, or those related to a surgical procedure (e.g., temporary headache)."

PET imaging showed no evidence of accelerated decline, and brain autopsy tissue from three patients who died of unrelated causes confirmed long-term, therapeutically active, gene-mediated NGF expression accurately targeted to the nucleus basalis of Meynert.

The researchers observed some deterioration over time based on the ADAS-Cog and other neuropsychological measures. "There is no clinical evidence that cognitive decline is accelerated, but we can’t speak to whether or not we actually improved rate of decline," Dr. Bartus said.

These findings formed the basis of a phase II trial currently underway that is funded by the National Institutes of Health under the auspices of the Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Study. Outcomes from that 24-month trial are expected in 2015.

The phase 1 study was funded by Ceregene, which was acquired in October 2013 by Sangamo BioSciences.

Dr. Bartus disclosed that he is a consultant for Sangamo BioSciences.

SAN DIEGO – Delivery of a gene therapy viral vector designed to express only the gene for human growth factor to the nucleus basalis of Meynert in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease appears to be safe and feasible, results from a first-in-human trial demonstrated.

"There are significant deficiencies with the therapies that exist for treating the memory and cognitive impairments of Alzheimer’s disease," Raymond T. Bartus, Ph.D., said at the Clinical Trials Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease.

Currently available cholinesterase inhibitors "are nonselective and suffer from serious dose-limiting side effects," said Dr. Bartus, president of San Diego–based RTBioconsultants. "Their mechanism of action for cholinergic enhancement is suboptimal, and they do not repair neurons, protect against death, or truly restore lost neuronal function. While they work to some extent, they are modest in their level of efficacy and do not improve symptoms in all patients. Moreover, they do nothing to affect the disease progression."

Nerve growth factor neurotrophic therapy, he continued, "should overcome all of these deficiencies and therefore provide a more effective therapy, applying a variation of the cholinergic approach that has shown proof of concept." Decades of research in animal models suggest that nerve growth factor "has remarkable antiapoptotic (i.e., antideath) and reparative properties for certain neurons in the degenerative brain," Dr. Bartus said. "There are at least two major obstacles to apply this technology to Alzheimer’s disease. The first is, Alzheimer’s is an extremely complicated disease, so determining where to target the treatment is especially important. Targeting the cholinergic neurons is compelling because their degeneration is known to contribute significantly to the memory loss."

The second key challenge, he said, is the need for constant exposure to cholinergic neurons that comprise the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) while avoiding exposure to untargeted neuronal populations. This has proven very difficult in past efforts extending back 20 years. In the past decade, gene therapy combined with stereotactic surgery has emerged as a practical enabling technology to accomplish this. On this basis, Dr. Bartus and his associates at Ceregene (where he served as chief scientific officer for more than 10 years) developed a viral gene therapy vector bioengineered to express only the gene for human nerve growth factor (AAV2-NGF, or CERE-110).

"You can think of it as an off-the-shelf biopharmaceutical that when injected into the human brain will induce the target neurons to produce or express and secrete only nerve growth factor and therefore provide support to NBM cholinergic neurons," he explained. "Preclinical studies have demonstrated an orderly dose-response relationship with NGF restricted to targeted basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, and no side effects or toxicity, even after testing very high doses in animals. That was quite surprising and certainly welcome."

Dr. Bartus presented phase I clinical data from 10 patients aged 50-79 years with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who received one of three ascending doses of AAV2-NGF via bilateral stereotactic injection into the nucleus basalis of Meynert: dose A (1.2 x 1010 viral genomes), dose B (5.8 x 1010 viral genomes; five times more than dose A), and dose C (1.2 x 1011 viral genomes; two times more than dose B). Patients were followed at 24 months for safety and feasibility and preliminary efficacy as measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months; autopsy tissue; and validated neuropsychological tests that included the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive (ADAS-Cog). Computer graphic software was used to provide a 3-D model of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in an effort to "determine where to distribute CERE-110 in the NBM and how much should be given to achieve optimal NGF exposure."

Dr. Bartus reported that AAV2-NGF was safe and well tolerated through 24 months. Adverse events and serious adverse events "were uneventful," he said. "What you see is a profile that reflects either incidental or unrelated events, or those related to a surgical procedure (e.g., temporary headache)."

PET imaging showed no evidence of accelerated decline, and brain autopsy tissue from three patients who died of unrelated causes confirmed long-term, therapeutically active, gene-mediated NGF expression accurately targeted to the nucleus basalis of Meynert.

The researchers observed some deterioration over time based on the ADAS-Cog and other neuropsychological measures. "There is no clinical evidence that cognitive decline is accelerated, but we can’t speak to whether or not we actually improved rate of decline," Dr. Bartus said.

These findings formed the basis of a phase II trial currently underway that is funded by the National Institutes of Health under the auspices of the Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Study. Outcomes from that 24-month trial are expected in 2015.

The phase 1 study was funded by Ceregene, which was acquired in October 2013 by Sangamo BioSciences.

Dr. Bartus disclosed that he is a consultant for Sangamo BioSciences.

SAN DIEGO – Delivery of a gene therapy viral vector designed to express only the gene for human growth factor to the nucleus basalis of Meynert in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease appears to be safe and feasible, results from a first-in-human trial demonstrated.

"There are significant deficiencies with the therapies that exist for treating the memory and cognitive impairments of Alzheimer’s disease," Raymond T. Bartus, Ph.D., said at the Clinical Trials Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease.

Currently available cholinesterase inhibitors "are nonselective and suffer from serious dose-limiting side effects," said Dr. Bartus, president of San Diego–based RTBioconsultants. "Their mechanism of action for cholinergic enhancement is suboptimal, and they do not repair neurons, protect against death, or truly restore lost neuronal function. While they work to some extent, they are modest in their level of efficacy and do not improve symptoms in all patients. Moreover, they do nothing to affect the disease progression."

Nerve growth factor neurotrophic therapy, he continued, "should overcome all of these deficiencies and therefore provide a more effective therapy, applying a variation of the cholinergic approach that has shown proof of concept." Decades of research in animal models suggest that nerve growth factor "has remarkable antiapoptotic (i.e., antideath) and reparative properties for certain neurons in the degenerative brain," Dr. Bartus said. "There are at least two major obstacles to apply this technology to Alzheimer’s disease. The first is, Alzheimer’s is an extremely complicated disease, so determining where to target the treatment is especially important. Targeting the cholinergic neurons is compelling because their degeneration is known to contribute significantly to the memory loss."

The second key challenge, he said, is the need for constant exposure to cholinergic neurons that comprise the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) while avoiding exposure to untargeted neuronal populations. This has proven very difficult in past efforts extending back 20 years. In the past decade, gene therapy combined with stereotactic surgery has emerged as a practical enabling technology to accomplish this. On this basis, Dr. Bartus and his associates at Ceregene (where he served as chief scientific officer for more than 10 years) developed a viral gene therapy vector bioengineered to express only the gene for human nerve growth factor (AAV2-NGF, or CERE-110).

"You can think of it as an off-the-shelf biopharmaceutical that when injected into the human brain will induce the target neurons to produce or express and secrete only nerve growth factor and therefore provide support to NBM cholinergic neurons," he explained. "Preclinical studies have demonstrated an orderly dose-response relationship with NGF restricted to targeted basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, and no side effects or toxicity, even after testing very high doses in animals. That was quite surprising and certainly welcome."

Dr. Bartus presented phase I clinical data from 10 patients aged 50-79 years with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who received one of three ascending doses of AAV2-NGF via bilateral stereotactic injection into the nucleus basalis of Meynert: dose A (1.2 x 1010 viral genomes), dose B (5.8 x 1010 viral genomes; five times more than dose A), and dose C (1.2 x 1011 viral genomes; two times more than dose B). Patients were followed at 24 months for safety and feasibility and preliminary efficacy as measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months; autopsy tissue; and validated neuropsychological tests that included the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive (ADAS-Cog). Computer graphic software was used to provide a 3-D model of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in an effort to "determine where to distribute CERE-110 in the NBM and how much should be given to achieve optimal NGF exposure."

Dr. Bartus reported that AAV2-NGF was safe and well tolerated through 24 months. Adverse events and serious adverse events "were uneventful," he said. "What you see is a profile that reflects either incidental or unrelated events, or those related to a surgical procedure (e.g., temporary headache)."

PET imaging showed no evidence of accelerated decline, and brain autopsy tissue from three patients who died of unrelated causes confirmed long-term, therapeutically active, gene-mediated NGF expression accurately targeted to the nucleus basalis of Meynert.

The researchers observed some deterioration over time based on the ADAS-Cog and other neuropsychological measures. "There is no clinical evidence that cognitive decline is accelerated, but we can’t speak to whether or not we actually improved rate of decline," Dr. Bartus said.

These findings formed the basis of a phase II trial currently underway that is funded by the National Institutes of Health under the auspices of the Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Study. Outcomes from that 24-month trial are expected in 2015.

The phase 1 study was funded by Ceregene, which was acquired in October 2013 by Sangamo BioSciences.

Dr. Bartus disclosed that he is a consultant for Sangamo BioSciences.

AT CTAD

Major finding: At 24 months, human nerve growth factor gene therapy via bilateral stereotactic injection into the nucleus basalis of Meynert was safe and well tolerated, PET imaging showed no evidence of accelerated decline, and brain autopsy tissue from three patients who died of unrelated causes confirmed long-term, therapeutically active, gene-mediated NGF expression.

Data source: A study of 10 patients aged 50-79 years with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who received one of three ascending doses of AAV2-NGF.

Disclosures: Dr. Bartus disclosed that he is a consultant for Sangamo BioSciences.

Small study: TBI leads to rapid deposition of brain amyloid

Brain imaging of patients with traumatic brain injury in conjunction with analyses of postmortem tissue appears to confirm that beta amyloid plaques form in some areas of the brain shortly after injury, according to findings published Nov. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

The finding suggests that PET with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid beta plaques, could be useful in the post-TBI patient workup, reported Young T. Hong, Ph.D., of the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre at the University of Cambridge, England, and colleagues.

"The use of [PET PiB] for amyloid imaging following TBI provides us with the potential for understanding the pathophysiology of TBI, for characterizing the mechanistic drivers of disease progression or suboptimal recovery in the subacute phase of TBI, for identifying patients at high risk of accelerated [Alzheimer’s disease], and for evaluating the potential of antiamyloid therapies," the investigators wrote (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Nov. 11 [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4847]).

PET with PiB in 15 patients with a traumatic brain injury that occurred 1-361 days before showed more amyloid binding than did the scans of 11 healthy controls. Amyloid tended to appear rapidly – within 48 hours of injury in some patients. It was located with significantly greater concentration in the cortical gray matter and striatum of TBI patients, compared with controls, but not in the thalamus or white matter. However, most patients showed very little accumulation around the injury site or in places with high vasogenic edema. The medial temporal and hippocampal regions were likewise spared, the investigators noted.

They saw similar results in comparisons of postmortem tissue samples from 16 patients who had died 3 hours to 56 days after a TBI and 7 who had died of other, nonneurologic causes that were analyzed via autoradiography with tritium-labeled PiB and immunocytochemistry for amyloid beta. TBI patients had more frequent and denser amyloid in the neocortical gray matter than did controls. There was no cerebellar cortical amyloid binding among TBI patients except for a 61-year old woman who died 12 hours after a brain injury and had amyloid accumulation in the meningeal vessels.

In the imaging portion of the study, TBI patients and healthy controls had median ages of 33 years and 35 years, respectively. The postmortem analyses involved TBI patients and controls with median ages of 46 years and 61 years, respectively. Patients were matched for age within the cohorts.

Of the 15 TBI patients who underwent PET with PiB, 8 survived with good recovery, 2 with moderate disability, and 3 with severe disability; the other 2 remained in a vegetative state.

The amyloid biding in the TBI patients is reminiscent of the early amyloid deposition seen in some patients who have presenilin-1 gene mutations, which cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The areas of PiB binding in the TBI patients "would therefore be concordant with currently proposed mechanism of overproduction leading to amyloid deposition in TBI," the authors noted.

The study’s biggest weaknesses are its small sample size and lack of serial imaging, the latter perhaps most important because the small proportion of late studies in the 15-patient cohort "limits inferences regarding the temporal pattern of [PiB] binding in vivo and requires confirmation in a larger cohort," they wrote.

The National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre funded the study. Two authors – Dr. William E. Klunk and Chester A. Mathis, Ph.D. – are coinventors of PiB and have a financial interest in the licensing agreement for PiB between GE Healthcare and the University of Pittsburgh.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Brain imaging of patients with traumatic brain injury in conjunction with analyses of postmortem tissue appears to confirm that beta amyloid plaques form in some areas of the brain shortly after injury, according to findings published Nov. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

The finding suggests that PET with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid beta plaques, could be useful in the post-TBI patient workup, reported Young T. Hong, Ph.D., of the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre at the University of Cambridge, England, and colleagues.

"The use of [PET PiB] for amyloid imaging following TBI provides us with the potential for understanding the pathophysiology of TBI, for characterizing the mechanistic drivers of disease progression or suboptimal recovery in the subacute phase of TBI, for identifying patients at high risk of accelerated [Alzheimer’s disease], and for evaluating the potential of antiamyloid therapies," the investigators wrote (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Nov. 11 [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4847]).

PET with PiB in 15 patients with a traumatic brain injury that occurred 1-361 days before showed more amyloid binding than did the scans of 11 healthy controls. Amyloid tended to appear rapidly – within 48 hours of injury in some patients. It was located with significantly greater concentration in the cortical gray matter and striatum of TBI patients, compared with controls, but not in the thalamus or white matter. However, most patients showed very little accumulation around the injury site or in places with high vasogenic edema. The medial temporal and hippocampal regions were likewise spared, the investigators noted.

They saw similar results in comparisons of postmortem tissue samples from 16 patients who had died 3 hours to 56 days after a TBI and 7 who had died of other, nonneurologic causes that were analyzed via autoradiography with tritium-labeled PiB and immunocytochemistry for amyloid beta. TBI patients had more frequent and denser amyloid in the neocortical gray matter than did controls. There was no cerebellar cortical amyloid binding among TBI patients except for a 61-year old woman who died 12 hours after a brain injury and had amyloid accumulation in the meningeal vessels.

In the imaging portion of the study, TBI patients and healthy controls had median ages of 33 years and 35 years, respectively. The postmortem analyses involved TBI patients and controls with median ages of 46 years and 61 years, respectively. Patients were matched for age within the cohorts.

Of the 15 TBI patients who underwent PET with PiB, 8 survived with good recovery, 2 with moderate disability, and 3 with severe disability; the other 2 remained in a vegetative state.

The amyloid biding in the TBI patients is reminiscent of the early amyloid deposition seen in some patients who have presenilin-1 gene mutations, which cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The areas of PiB binding in the TBI patients "would therefore be concordant with currently proposed mechanism of overproduction leading to amyloid deposition in TBI," the authors noted.

The study’s biggest weaknesses are its small sample size and lack of serial imaging, the latter perhaps most important because the small proportion of late studies in the 15-patient cohort "limits inferences regarding the temporal pattern of [PiB] binding in vivo and requires confirmation in a larger cohort," they wrote.

The National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre funded the study. Two authors – Dr. William E. Klunk and Chester A. Mathis, Ph.D. – are coinventors of PiB and have a financial interest in the licensing agreement for PiB between GE Healthcare and the University of Pittsburgh.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Brain imaging of patients with traumatic brain injury in conjunction with analyses of postmortem tissue appears to confirm that beta amyloid plaques form in some areas of the brain shortly after injury, according to findings published Nov. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

The finding suggests that PET with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), which binds to amyloid beta plaques, could be useful in the post-TBI patient workup, reported Young T. Hong, Ph.D., of the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre at the University of Cambridge, England, and colleagues.

"The use of [PET PiB] for amyloid imaging following TBI provides us with the potential for understanding the pathophysiology of TBI, for characterizing the mechanistic drivers of disease progression or suboptimal recovery in the subacute phase of TBI, for identifying patients at high risk of accelerated [Alzheimer’s disease], and for evaluating the potential of antiamyloid therapies," the investigators wrote (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Nov. 11 [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4847]).

PET with PiB in 15 patients with a traumatic brain injury that occurred 1-361 days before showed more amyloid binding than did the scans of 11 healthy controls. Amyloid tended to appear rapidly – within 48 hours of injury in some patients. It was located with significantly greater concentration in the cortical gray matter and striatum of TBI patients, compared with controls, but not in the thalamus or white matter. However, most patients showed very little accumulation around the injury site or in places with high vasogenic edema. The medial temporal and hippocampal regions were likewise spared, the investigators noted.

They saw similar results in comparisons of postmortem tissue samples from 16 patients who had died 3 hours to 56 days after a TBI and 7 who had died of other, nonneurologic causes that were analyzed via autoradiography with tritium-labeled PiB and immunocytochemistry for amyloid beta. TBI patients had more frequent and denser amyloid in the neocortical gray matter than did controls. There was no cerebellar cortical amyloid binding among TBI patients except for a 61-year old woman who died 12 hours after a brain injury and had amyloid accumulation in the meningeal vessels.

In the imaging portion of the study, TBI patients and healthy controls had median ages of 33 years and 35 years, respectively. The postmortem analyses involved TBI patients and controls with median ages of 46 years and 61 years, respectively. Patients were matched for age within the cohorts.

Of the 15 TBI patients who underwent PET with PiB, 8 survived with good recovery, 2 with moderate disability, and 3 with severe disability; the other 2 remained in a vegetative state.

The amyloid biding in the TBI patients is reminiscent of the early amyloid deposition seen in some patients who have presenilin-1 gene mutations, which cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The areas of PiB binding in the TBI patients "would therefore be concordant with currently proposed mechanism of overproduction leading to amyloid deposition in TBI," the authors noted.

The study’s biggest weaknesses are its small sample size and lack of serial imaging, the latter perhaps most important because the small proportion of late studies in the 15-patient cohort "limits inferences regarding the temporal pattern of [PiB] binding in vivo and requires confirmation in a larger cohort," they wrote.

The National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre funded the study. Two authors – Dr. William E. Klunk and Chester A. Mathis, Ph.D. – are coinventors of PiB and have a financial interest in the licensing agreement for PiB between GE Healthcare and the University of Pittsburgh.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Major finding: Amyloid was located with significantly greater concentration in the cortical gray matter and striatum of TBI patients, compared with controls, but not in the thalamus or white matter.

Data source: The study compared brain imaging scans of 15 patients with recent TBI and 11 healthy controls, and postmortem brain tissue samples between 16 TBI patients and 7 controls.

Disclosures: The National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre funded the study. Two authors – Dr. William E. Klunk and Chester A. Mathis, Ph.D. – are coinventors of PiB and have a financial interest in the licensing agreement for PiB between GE Healthcare and the University of Pittsburgh.

Bicycle helmet use remains low, varies by ethnicity and socioeconomic status

ORLANDO – Only 11.3% of more than 1,200 children involved in bicycle-related accidents were wearing a helmet at the time of the accident, a study showed.

Children over age 12, and those of minority background and lower socioeconomic status, had the lowest rates of helmet use; thus the findings have implications for targeted education and prevention strategies, Dr. Veronica Sullins reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Of the 1,248 children from Los Angeles County who were included in the retrospective study of all injuries related to pediatric bicycle accidents between 2006 and 2011, most (85%) were boys. More than a third (35.2%) of white children wore helmets, but the rates were much lower for Asian (7.0%), black (6.0%), and Hispanic children (4.2%), said Dr. Sullins of the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif.

This is despite laws mandating helmet use in Los Angeles County, Dr. Sullins noted.

The differences in helmet use also appeared to vary based on socioeconomic status; helmets were worn by 15.2% of those with private insurance, compared with 7.6% of those with public insurance, Dr. Sullins noted.

Children in the study had a median age of 13 years. Those over age 12 were less likely to wear helmets than were those aged 12 years or younger (odds ratio, 0.7).

Emergency surgery was required in 5.9% of the children, and only 34.1% returned to their preinjury status. Nine patients (0.7%) died as a result of their injuries; eight of those were not wearing a helmet.

The findings suggest that targeting low-income middle and high schools and minority communities with bicycle safety education and accident prevention strategies may help improve helmet use in children, Dr. Sullins said.

"We really need to focus our efforts and resources on education programs targeting the highest-risk groups. In Los Angeles County, these groups are middle and high school–aged children, minorities, and those of lower socioeconomic status," Dr. Sullins said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 33 million children ride bicycles – for a total of 10 billion hours - each year, and nearly 400 children die as a result of bicycle crashes.

More than 150,000 emergency department visits each year are due to bicycle-related head injuries.

Helmet use has been shown to reduce bicycle-related head injuries by 80%; yet, as the results of this study and others show, the rate of helmet use remains low. The CDC reports that only 15% of adults and 19% of children wear helmets most or all of the time when riding a bicycle.

"We encourage other investigators to perform similar studies to identify [the highest-risk] groups specific to their regions or cities in order to more efficiently direct local injury prevention programs," Dr. Sullins said in the interview.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Only 11.3% of more than 1,200 children involved in bicycle-related accidents were wearing a helmet at the time of the accident, a study showed.

Children over age 12, and those of minority background and lower socioeconomic status, had the lowest rates of helmet use; thus the findings have implications for targeted education and prevention strategies, Dr. Veronica Sullins reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Of the 1,248 children from Los Angeles County who were included in the retrospective study of all injuries related to pediatric bicycle accidents between 2006 and 2011, most (85%) were boys. More than a third (35.2%) of white children wore helmets, but the rates were much lower for Asian (7.0%), black (6.0%), and Hispanic children (4.2%), said Dr. Sullins of the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif.

This is despite laws mandating helmet use in Los Angeles County, Dr. Sullins noted.

The differences in helmet use also appeared to vary based on socioeconomic status; helmets were worn by 15.2% of those with private insurance, compared with 7.6% of those with public insurance, Dr. Sullins noted.

Children in the study had a median age of 13 years. Those over age 12 were less likely to wear helmets than were those aged 12 years or younger (odds ratio, 0.7).

Emergency surgery was required in 5.9% of the children, and only 34.1% returned to their preinjury status. Nine patients (0.7%) died as a result of their injuries; eight of those were not wearing a helmet.

The findings suggest that targeting low-income middle and high schools and minority communities with bicycle safety education and accident prevention strategies may help improve helmet use in children, Dr. Sullins said.

"We really need to focus our efforts and resources on education programs targeting the highest-risk groups. In Los Angeles County, these groups are middle and high school–aged children, minorities, and those of lower socioeconomic status," Dr. Sullins said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 33 million children ride bicycles – for a total of 10 billion hours - each year, and nearly 400 children die as a result of bicycle crashes.

More than 150,000 emergency department visits each year are due to bicycle-related head injuries.

Helmet use has been shown to reduce bicycle-related head injuries by 80%; yet, as the results of this study and others show, the rate of helmet use remains low. The CDC reports that only 15% of adults and 19% of children wear helmets most or all of the time when riding a bicycle.

"We encourage other investigators to perform similar studies to identify [the highest-risk] groups specific to their regions or cities in order to more efficiently direct local injury prevention programs," Dr. Sullins said in the interview.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Only 11.3% of more than 1,200 children involved in bicycle-related accidents were wearing a helmet at the time of the accident, a study showed.

Children over age 12, and those of minority background and lower socioeconomic status, had the lowest rates of helmet use; thus the findings have implications for targeted education and prevention strategies, Dr. Veronica Sullins reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Of the 1,248 children from Los Angeles County who were included in the retrospective study of all injuries related to pediatric bicycle accidents between 2006 and 2011, most (85%) were boys. More than a third (35.2%) of white children wore helmets, but the rates were much lower for Asian (7.0%), black (6.0%), and Hispanic children (4.2%), said Dr. Sullins of the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif.

This is despite laws mandating helmet use in Los Angeles County, Dr. Sullins noted.

The differences in helmet use also appeared to vary based on socioeconomic status; helmets were worn by 15.2% of those with private insurance, compared with 7.6% of those with public insurance, Dr. Sullins noted.

Children in the study had a median age of 13 years. Those over age 12 were less likely to wear helmets than were those aged 12 years or younger (odds ratio, 0.7).

Emergency surgery was required in 5.9% of the children, and only 34.1% returned to their preinjury status. Nine patients (0.7%) died as a result of their injuries; eight of those were not wearing a helmet.

The findings suggest that targeting low-income middle and high schools and minority communities with bicycle safety education and accident prevention strategies may help improve helmet use in children, Dr. Sullins said.

"We really need to focus our efforts and resources on education programs targeting the highest-risk groups. In Los Angeles County, these groups are middle and high school–aged children, minorities, and those of lower socioeconomic status," Dr. Sullins said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 33 million children ride bicycles – for a total of 10 billion hours - each year, and nearly 400 children die as a result of bicycle crashes.

More than 150,000 emergency department visits each year are due to bicycle-related head injuries.

Helmet use has been shown to reduce bicycle-related head injuries by 80%; yet, as the results of this study and others show, the rate of helmet use remains low. The CDC reports that only 15% of adults and 19% of children wear helmets most or all of the time when riding a bicycle.

"We encourage other investigators to perform similar studies to identify [the highest-risk] groups specific to their regions or cities in order to more efficiently direct local injury prevention programs," Dr. Sullins said in the interview.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE AAP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Major finding: Only 11.3% of children injured in bicycle accidents were wearing a helmet (35.2%, 7.0%, 6.0%, and 4.2% of white, Asian, black, and Hispanic children, respectively).

Data source: A retrospective study of 1,248 cases of injury related to bicycle accidents during 2006-2011.

Disclosure: Dr. Sullins reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Clinical report: Students may need school break after concussion

Patients who sustain a concussion need their physicians’ guidance in returning to school in a way that facilitates rather than hinders their recovery, and the American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a clinical report to help.

Most research on pediatric concussions has focused on returning the patient to sports or other physical activities, while data for managing the "return to learn" are sparse. Many published statements emphasize the need for "cognitive rest" – avoiding obvious potential cognitive stressors such as class work and homework – but fall short of identifying and dealing with the myriad other stimuli that can impede recovery or even worsen symptoms, reported Dr. Mark E. Halstead and his associates on the AAP Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness and the AAP Council on School Health (Pediatrics 2013;132:948-57).

An estimated 1.7 million traumatic brain injuries occur each year, many of them concussions. "Given that students typically appear well physically after a concussion, it may be difficult for educators, school administrators, and peers to fully understand the extent of deficits experienced by a student with a concussion." This, in turn, might make school officials reluctant to accept that they must make adjustments for such students.

Pediatricians are in an excellent position to inform these educators, as well as the patients themselves and their families, of the symptoms that might develop and the strategies to prevent or minimize cognitive stress during recovery, said Dr. Halstead, an orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist at Washington University in St. Louis and Children’s Hospital of St. Louis, and his associates. Dr. Halstead also presented the clinical report Oct. 27 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics in Orlando.

The clinical report notes that most concussions resolve within 3 weeks of the injury, so most adjustments to the school environment can be made in the individual classroom setting without the need for a formalized written plan such as a 504 plan or individualized education plan. However, students who require longer-term recovery need more formalized accommodations and modifications.

The report lists typical signs and symptoms of concussion, along with adjustments that teachers and administrators can make to help the child returning to school.

Headache is the most frequent symptom and can recur throughout recovery. School personnel should be made aware that fluorescent lighting, loud noises, and even simply concentrating on a task can elicit headache in these patients, so they should be allowed to take breaks in a quiet area when needed.