User login

A gentler approach to gastroschisis improves outcomes

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Multiple sclerosis may not flare up after pregnancy

PHILADELPHIA – according to a study to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We did not observe any rebound disease activity,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD, and her research colleagues in their report.

The findings contrast with those of 20-year-old studies that first identified a lower risk of relapse during pregnancy but signficant rebound disease activity in the early postpartum period. The initial studies were conducted before disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) were available and before neurologists used MRI to help diagnose MS after one attack, noted Dr. Langer-Gould in a statement.

In the large, contemporary cohort of patients with MS, the annualized relapse rate was 0.39 pre-pregnancy, 0.07-0.14 during pregnancy, 0.27 in the first 3 months postpartum, and 0.37 at 4-6 months postpartum. Exclusive breastfeeding significantly reduced the risk of postpartum relapses by 42% (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.58). Women who supplemented breast milk with formula within 2 months of delivery had the same risk of relapse as women who did not breastfeed, however.

“These results are exciting, as MS is more common among women of childbearing age than in any other group,” said Dr. Langer-Gould, who is regional lead for clinical and translational neuroscience at Kaiser Permanente Southern California in Pasadena, in the statement. “This shows us that women with MS today can have children, breastfeed, and resume their treatment without experiencing an increased risk of relapses during the postpartum period.”

To describe the risk of postpartum relapses and identify potential risk factors for relapse the investigators analyzed prospectively collected data from 466 pregnancies among 375 women with MS from the complete electronic health record at Kaiser Permanente Southern and Northern California between 2008 and 2016. The researchers also used surveys to collect information about treatment history, breastfeeding, and relapses. They used multivariable models to account for intraclass clustering and disease severity.

In 38% of the pregnancies, the mother had not received treatment in the year before conception. In 14.6%, the mother had a clinically isolated syndrome; in 8.4%, the mother had a relapse during pregnancy.

Resuming modestly effective DMTs such as interferon-betas and glatiramer acetate did not affect relapse risk.

In the postpartum year, 26.4% of mothers relapsed, 87% breastfed, 35% breastfed exclusively, and 41.2% resumed using DMT.

The lack of rebound disease activity in this cohort could be related to the high rate of exclusive breastfeeding, as well as the inclusion of women from a population-based setting and the inclusion of women who had incorrectly been diagnosed with MS after a single relapse. Few patients in this cohort had been treated with natalizumab or fingolimod prior to pregnancy, so the study does not address the potential harms of stopping these drugs or the potential benefits of breastfeeding among patients treated with these drugs.

The study was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S6.007.

PHILADELPHIA – according to a study to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We did not observe any rebound disease activity,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD, and her research colleagues in their report.

The findings contrast with those of 20-year-old studies that first identified a lower risk of relapse during pregnancy but signficant rebound disease activity in the early postpartum period. The initial studies were conducted before disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) were available and before neurologists used MRI to help diagnose MS after one attack, noted Dr. Langer-Gould in a statement.

In the large, contemporary cohort of patients with MS, the annualized relapse rate was 0.39 pre-pregnancy, 0.07-0.14 during pregnancy, 0.27 in the first 3 months postpartum, and 0.37 at 4-6 months postpartum. Exclusive breastfeeding significantly reduced the risk of postpartum relapses by 42% (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.58). Women who supplemented breast milk with formula within 2 months of delivery had the same risk of relapse as women who did not breastfeed, however.

“These results are exciting, as MS is more common among women of childbearing age than in any other group,” said Dr. Langer-Gould, who is regional lead for clinical and translational neuroscience at Kaiser Permanente Southern California in Pasadena, in the statement. “This shows us that women with MS today can have children, breastfeed, and resume their treatment without experiencing an increased risk of relapses during the postpartum period.”

To describe the risk of postpartum relapses and identify potential risk factors for relapse the investigators analyzed prospectively collected data from 466 pregnancies among 375 women with MS from the complete electronic health record at Kaiser Permanente Southern and Northern California between 2008 and 2016. The researchers also used surveys to collect information about treatment history, breastfeeding, and relapses. They used multivariable models to account for intraclass clustering and disease severity.

In 38% of the pregnancies, the mother had not received treatment in the year before conception. In 14.6%, the mother had a clinically isolated syndrome; in 8.4%, the mother had a relapse during pregnancy.

Resuming modestly effective DMTs such as interferon-betas and glatiramer acetate did not affect relapse risk.

In the postpartum year, 26.4% of mothers relapsed, 87% breastfed, 35% breastfed exclusively, and 41.2% resumed using DMT.

The lack of rebound disease activity in this cohort could be related to the high rate of exclusive breastfeeding, as well as the inclusion of women from a population-based setting and the inclusion of women who had incorrectly been diagnosed with MS after a single relapse. Few patients in this cohort had been treated with natalizumab or fingolimod prior to pregnancy, so the study does not address the potential harms of stopping these drugs or the potential benefits of breastfeeding among patients treated with these drugs.

The study was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S6.007.

PHILADELPHIA – according to a study to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We did not observe any rebound disease activity,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD, and her research colleagues in their report.

The findings contrast with those of 20-year-old studies that first identified a lower risk of relapse during pregnancy but signficant rebound disease activity in the early postpartum period. The initial studies were conducted before disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) were available and before neurologists used MRI to help diagnose MS after one attack, noted Dr. Langer-Gould in a statement.

In the large, contemporary cohort of patients with MS, the annualized relapse rate was 0.39 pre-pregnancy, 0.07-0.14 during pregnancy, 0.27 in the first 3 months postpartum, and 0.37 at 4-6 months postpartum. Exclusive breastfeeding significantly reduced the risk of postpartum relapses by 42% (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.58). Women who supplemented breast milk with formula within 2 months of delivery had the same risk of relapse as women who did not breastfeed, however.

“These results are exciting, as MS is more common among women of childbearing age than in any other group,” said Dr. Langer-Gould, who is regional lead for clinical and translational neuroscience at Kaiser Permanente Southern California in Pasadena, in the statement. “This shows us that women with MS today can have children, breastfeed, and resume their treatment without experiencing an increased risk of relapses during the postpartum period.”

To describe the risk of postpartum relapses and identify potential risk factors for relapse the investigators analyzed prospectively collected data from 466 pregnancies among 375 women with MS from the complete electronic health record at Kaiser Permanente Southern and Northern California between 2008 and 2016. The researchers also used surveys to collect information about treatment history, breastfeeding, and relapses. They used multivariable models to account for intraclass clustering and disease severity.

In 38% of the pregnancies, the mother had not received treatment in the year before conception. In 14.6%, the mother had a clinically isolated syndrome; in 8.4%, the mother had a relapse during pregnancy.

Resuming modestly effective DMTs such as interferon-betas and glatiramer acetate did not affect relapse risk.

In the postpartum year, 26.4% of mothers relapsed, 87% breastfed, 35% breastfed exclusively, and 41.2% resumed using DMT.

The lack of rebound disease activity in this cohort could be related to the high rate of exclusive breastfeeding, as well as the inclusion of women from a population-based setting and the inclusion of women who had incorrectly been diagnosed with MS after a single relapse. Few patients in this cohort had been treated with natalizumab or fingolimod prior to pregnancy, so the study does not address the potential harms of stopping these drugs or the potential benefits of breastfeeding among patients treated with these drugs.

The study was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S6.007.

FROM AAN 2019

ACOG guidance addresses cardiac contributors to maternal mortality

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to new comprehensive guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The toolkit algorithm is called the California Improving Health Care Response to Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy and Postpartum Toolkit. It was developed by the Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy Postpartum Task Force to serve as a resource for obstetrics, primary care and emergency medicine providers who provide prenatal care or interact with women during the postpartum period. It incldues an overview of clinical assessment and comprehensive management strategies for cardiovascular disease based on risk factors and presenting symptoms.

The guidance also calls for all pregnant and postpartum women with known or suspected CVD to undergo further evaluation by a “Pregnancy Heart Team that includes a cardiologist and maternal–fetal medicine subspecialist, or both, and other subspecialists as necessary.” The guidance was issued in Practice Bulletin 212, Pregnancy and Heart Disease, which is published in the May edition of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-e356).

In all, 27 specific recommendations and conclusions relating to screening, diagnosis, and management of CVD for women during the prepregnancy period through the postpartum period are included in the guidance.

ACOG president Lisa Hollier, MD, convened the task force that developed this guidance to address cardiac contributors to maternal mortality, she said during a press briefing at the ACOG annual clinical and scientific meeting.

“When I began my presidency a year ago, my goal was to bring together a multidisciplinary group of clinicians ... to create clinical guidance that would make a difference in the lives of women," said Dr. Hollier, who is also a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Part of her presidential initiative was centered on eliminating preventable maternal death, and this guidance has the potential to make strides toward that goal, she said. When it comes to CVD in pregnancy, “there is so much we can do to prevent negative outcomes and ensure that moms go home with their babies and are around to see them grow up,” she noted.

CVD is the leading cause of death in pregnant women and women in the postpartum period, accounting for 26.5% of U.S. pregnancy-related deaths.

“It’s critical that we as physicians and health care professionals develop expertise in recognizing the signs and symptoms so that we can save women’s lives,” she said in the press breifing. Dr. Hollier also implored her colleagues to “start using this guidance immediately and prevent more women from dying from cardiovascular complications of pregnancy.”

In this video interview, Dr. Hollier further explains the need for the guidance and its potential for improving maternal mortality rates.

Dr. Hollier reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hollier L et al., Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-56.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to new comprehensive guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The toolkit algorithm is called the California Improving Health Care Response to Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy and Postpartum Toolkit. It was developed by the Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy Postpartum Task Force to serve as a resource for obstetrics, primary care and emergency medicine providers who provide prenatal care or interact with women during the postpartum period. It incldues an overview of clinical assessment and comprehensive management strategies for cardiovascular disease based on risk factors and presenting symptoms.

The guidance also calls for all pregnant and postpartum women with known or suspected CVD to undergo further evaluation by a “Pregnancy Heart Team that includes a cardiologist and maternal–fetal medicine subspecialist, or both, and other subspecialists as necessary.” The guidance was issued in Practice Bulletin 212, Pregnancy and Heart Disease, which is published in the May edition of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-e356).

In all, 27 specific recommendations and conclusions relating to screening, diagnosis, and management of CVD for women during the prepregnancy period through the postpartum period are included in the guidance.

ACOG president Lisa Hollier, MD, convened the task force that developed this guidance to address cardiac contributors to maternal mortality, she said during a press briefing at the ACOG annual clinical and scientific meeting.

“When I began my presidency a year ago, my goal was to bring together a multidisciplinary group of clinicians ... to create clinical guidance that would make a difference in the lives of women," said Dr. Hollier, who is also a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Part of her presidential initiative was centered on eliminating preventable maternal death, and this guidance has the potential to make strides toward that goal, she said. When it comes to CVD in pregnancy, “there is so much we can do to prevent negative outcomes and ensure that moms go home with their babies and are around to see them grow up,” she noted.

CVD is the leading cause of death in pregnant women and women in the postpartum period, accounting for 26.5% of U.S. pregnancy-related deaths.

“It’s critical that we as physicians and health care professionals develop expertise in recognizing the signs and symptoms so that we can save women’s lives,” she said in the press breifing. Dr. Hollier also implored her colleagues to “start using this guidance immediately and prevent more women from dying from cardiovascular complications of pregnancy.”

In this video interview, Dr. Hollier further explains the need for the guidance and its potential for improving maternal mortality rates.

Dr. Hollier reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hollier L et al., Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-56.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to new comprehensive guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The toolkit algorithm is called the California Improving Health Care Response to Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy and Postpartum Toolkit. It was developed by the Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy Postpartum Task Force to serve as a resource for obstetrics, primary care and emergency medicine providers who provide prenatal care or interact with women during the postpartum period. It incldues an overview of clinical assessment and comprehensive management strategies for cardiovascular disease based on risk factors and presenting symptoms.

The guidance also calls for all pregnant and postpartum women with known or suspected CVD to undergo further evaluation by a “Pregnancy Heart Team that includes a cardiologist and maternal–fetal medicine subspecialist, or both, and other subspecialists as necessary.” The guidance was issued in Practice Bulletin 212, Pregnancy and Heart Disease, which is published in the May edition of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-e356).

In all, 27 specific recommendations and conclusions relating to screening, diagnosis, and management of CVD for women during the prepregnancy period through the postpartum period are included in the guidance.

ACOG president Lisa Hollier, MD, convened the task force that developed this guidance to address cardiac contributors to maternal mortality, she said during a press briefing at the ACOG annual clinical and scientific meeting.

“When I began my presidency a year ago, my goal was to bring together a multidisciplinary group of clinicians ... to create clinical guidance that would make a difference in the lives of women," said Dr. Hollier, who is also a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Part of her presidential initiative was centered on eliminating preventable maternal death, and this guidance has the potential to make strides toward that goal, she said. When it comes to CVD in pregnancy, “there is so much we can do to prevent negative outcomes and ensure that moms go home with their babies and are around to see them grow up,” she noted.

CVD is the leading cause of death in pregnant women and women in the postpartum period, accounting for 26.5% of U.S. pregnancy-related deaths.

“It’s critical that we as physicians and health care professionals develop expertise in recognizing the signs and symptoms so that we can save women’s lives,” she said in the press breifing. Dr. Hollier also implored her colleagues to “start using this guidance immediately and prevent more women from dying from cardiovascular complications of pregnancy.”

In this video interview, Dr. Hollier further explains the need for the guidance and its potential for improving maternal mortality rates.

Dr. Hollier reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hollier L et al., Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:e320-56.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Good news for ObGyns: Medical liability claims resulting in payment are decreasing!

Medical professional liability claims (claims) are a major cause of worry and agony for physicians who are dedicated to optimizing the health of all their patients. Among physicians, those who practice neurosurgery, thoracic surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology have the greatest rate of making a payment on a claim per year of practice.1 Physicians who practice psychiatry, pediatrics, pathology, and internal medicine have the lowest rate of making a payment on a claim. Among the physicians in high-risk specialties, greater than 90% will have a claim filed against them during their career.2 Although professional liability exposure reached a crisis during the 1980s and 1990s, recent data have shown a decrease in overall professional liability risk.

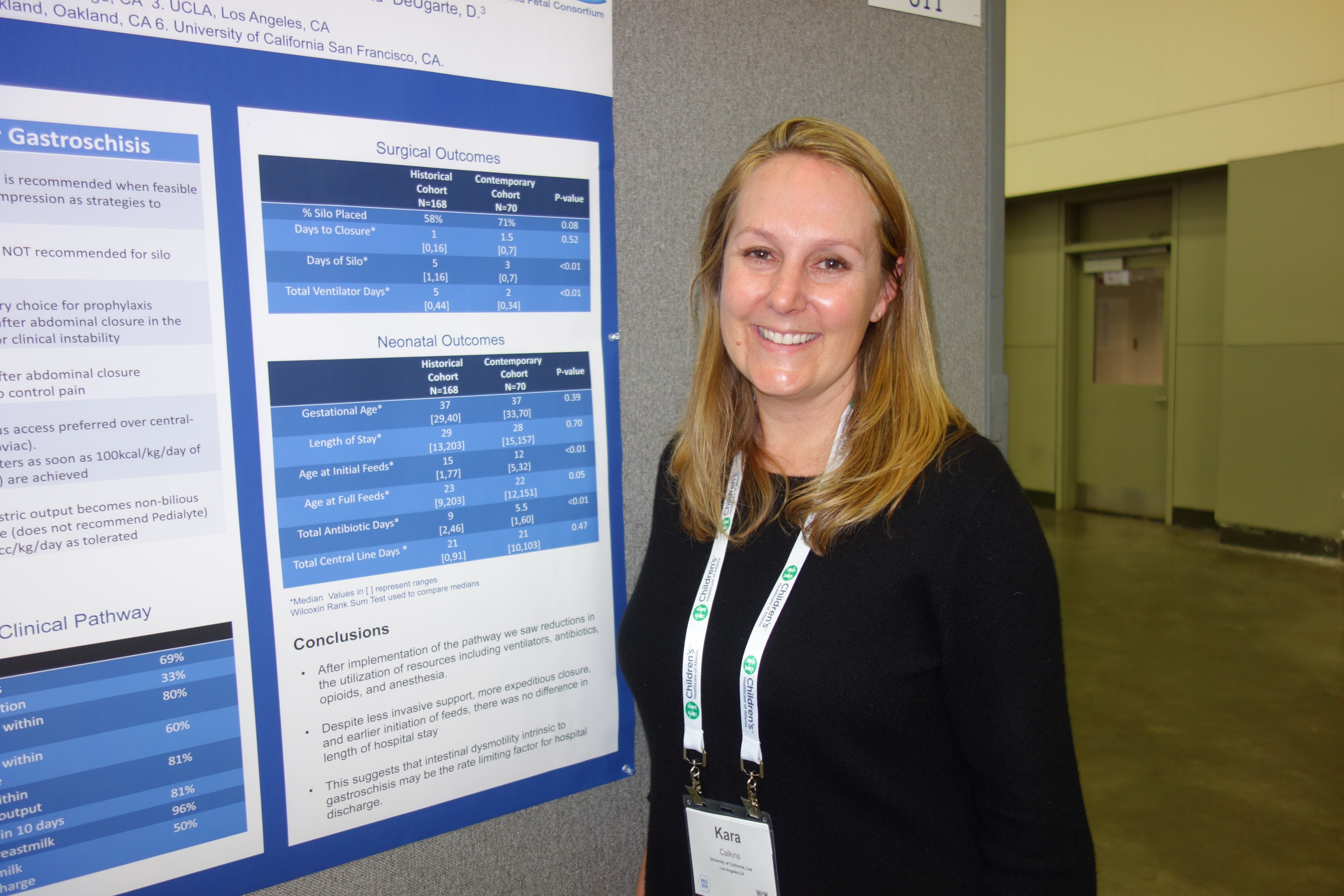

The good news: Paid claims per 1,000 ObGyns have decreased greatly

In a review of all paid claims reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank from 1992 to 2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was determined.1 For the time periods 1992–1996, 1997–2002, 2003–2008,and 2009–2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was 57.6, 51.5, 40.0, and 25.9, representing an astounding 55% decrease in paid claims from 1992 to 2014 (FIGURE).1

The majority of claims result in no payment

In a review of the experience of a nationwide professional liability insurer from 1991 to 2005, only 22% of claims resulted in a payment.2 In this study, for obstetrics and gynecology and gynecologic surgery, only 11% and 8% of claims, respectively, resulted in a payment.2 However, being named in a malpractice claim results in significant stress for a physician and requires a great deal of work and time to defend.

In another study using data from the Physician Insurer’s Association of America, among 10,915 claims closed from 2005 to 2014, 59.5% were dropped, withdrawn, or dismissed; 27.7% were settled; 2.5% were resolved using an alternative dispute resolution process; 1.8% were uncategorized; and 8.6% went to trial.3 Of the cases that went to trial, 87% resulted in a verdict for the physician and 13% resulted in a verdict for the plaintiff.3

Not as good news: Payments per claim and claims settling for a payment > $1 million are increasing

In the period 1992–1996, the average payment per paid claim in the field of obstetrics and gynecology was $387,186, rising to $447,034 in 2009–2014—a 16% increase.1 From 2004 to 2010, million dollar payments occurred in about 8% of cases of paid claims, but they represent 36% of the total of all paid claims.4 In the time periods 1992–1996 and 2009–2014, payments greater than $1 million occurred in 6% and 8% of paid claims, respectively.1

Claims settled for much more than $1 million are of great concern to physicians because the payment may exceed their policy limit, creating a complex legal problem that may take time to resolve. In some cases, where the award is greater than the insurance policy limit, aggressive plaintiff attorneys have obtained a lien on the defendant physician’s home pending settlement of the case. When a multimillion dollar payment is made to settle a professional liability claim, it can greatly influence physician practice and change hospital policies. Frequently, following a multimillion dollar payment a physician may decide to limit their practice to low-risk cases or retire from the practice of medicine.

Liability premiums are stable or decreasing

From 2014 to 2019, my ObGyn professional liability insurance premiums decreased by 18%. During the same time period, my colleagues who practice surgical gynecology (no obstetrics) had a premium decrease of 22%. Insurers use a complex algorithm to determine annual liability insurance premiums, and premiums for ObGyns may not have stabilized or decreased in all regions. Take this Instant Poll:

Create your own user feedback survey

Reform of the liability tort system

Litigation policies and practices that reduce liability risk reduce total medical liability losses. Policies that have helped to constrain medical liability risk include state constitutional amendments limiting payments for pain and suffering, caps on compensation to plaintiff attorneys, increased early resolution programs that compensate patients who experience an adverse event and no-fault conflict resolution programs.5 In 2003, Texas implemented a comprehensive package of tort reform laws. Experts believe the reforms decreased the financial burden of professional liability insurance6 and led to less defensive medical practices, reducing excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests.

Medical factors contributing to a decrease in claims

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine released the report, “To Err is Human,” which galvanized health care systems to deploy systems of care that reduce the rate of adverse patient outcomes.7 Over the past 20 years, health systems have implemented quality improvement programs in obstetrics and gynecology that have contributed to a reduction in the rate of adverse patient outcomes. This may have contributed to the decrease in the rate of paid claims.

In a quasi-experimental study performed in 13 health systems, 7 interventions were implemented with the goal of improving outcomes and reducing medical liability. The 7 interventions included8:

- an elective induction bundle focused on the safe use of oxytocin

- an augmentation bundle focused on early intervention for possible fetal metabolic acidosis

- an operative vaginal delivery bundle

- TeamSTEPPS teamwork training to improve the quality of communication

- best practices education with a focus on electronic fetal monitoring

- regular performance feedback to hospitals and clinicians

- implementation of a quality improvement collaboration to support implementation of the interventions.

During the two-year baseline period prior to the intervention there were 185,373 deliveries with 6.7 perinatal claims made per 10,000 deliveries and 1.3 claims paid per 10,000 deliveries. Following the intervention, the rate of claims made and claims paid per 10,000 deliveries decreased by 22% and 37%, respectively. In addition there was a marked decrease in claims over $1 million paid, greatly limiting total financial liability losses.

Experts with vast experience in obstetrics and obstetric liability litigation have identified 4 priority interventions that may improve outcomes and mitigate liability risk, including: 1) 24-hour in-house physician coverage of an obstetrics service, 2) a conservative approach to trial of labor after a prior cesarean delivery, 3) utilization of a comprehensive, standardized event note in cases of a shoulder dystocia, and 4) judicious use of oxytocin, misoprostol, and magnesium sulfate.9

Other health system interventions that may contribute to a reduction in claims include:

- systematic improvement in the quality of communication among physicians and nurses through the use of team training, preprocedure huddles, and time-out processes10

- rapid response systems to rescue hospital patients with worrisome vital signs11

- standardized responses to a worrisome category 2 or 3 fetal heart-rate tracing12

- rapid recognition, evaluation, and treatment of women with hemorrhage, severe hypertension, sepsis, and venous thromboembolism13

- identification and referral of high-risk patients to tertiary centers14

- closed loop communication of critical imaging and laboratory results15

- universal insurance coverage for health care including contraception, obstetrics, and pediatric care.

Medical liability risk is an important practice issue because it causes excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests and often traumatizes clinicians, which can result in burnout. In the 1980s and 1990s, medical liability litigation reached a crescendo and was a prominent concern among obstetrician-gynecologists. The good news is that, for ObGyns, liability risk has stabilized. Hopefully our resolute efforts to continuously improve the quality of care will result in a long-term reduction in medical liability risk.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992–2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-e6.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, et al. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Quality. 2014;36:43-53.

- Cardoso R, Zarin W, Nincic V, et al. Evaluative reports on medical malpractice policies in obstetrics: a rapid scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:181.

- Stewart RM, Geoghegan K, Myers JG, et al. Malpractice risk and costs are significantly reduced after tort reform. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:463-467.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Riley W, Meredith LW, Price R, et al. Decreasing malpractice claims by reducing preventable perinatal harm. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(suppl 3):2453-2471.

- Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1279-1283.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499.

- Patel S, Gillon SA, Jones DA. Rapid response systems: recognition and rescue of the deteriorating hospital patient. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:143-148.

- Clark SL, Hamilton EF, Garite TJ, et al. The limits of electronic fetal heart rate monitoring in the prevention of neonatal metabolic acidemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:163.e1-163.e6.

- The Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Healthcare website. www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- Zahn CM, Remick A, Catalano A, et al. Levels of maternal care verification pilot: translating guidance into practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1401-1406.

- Zuccotti G, Maloney FL, Feblowitz J, et al. Reducing risk with clinical decision support: a study of closed malpractice claims. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5:746-756.

Medical professional liability claims (claims) are a major cause of worry and agony for physicians who are dedicated to optimizing the health of all their patients. Among physicians, those who practice neurosurgery, thoracic surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology have the greatest rate of making a payment on a claim per year of practice.1 Physicians who practice psychiatry, pediatrics, pathology, and internal medicine have the lowest rate of making a payment on a claim. Among the physicians in high-risk specialties, greater than 90% will have a claim filed against them during their career.2 Although professional liability exposure reached a crisis during the 1980s and 1990s, recent data have shown a decrease in overall professional liability risk.

The good news: Paid claims per 1,000 ObGyns have decreased greatly

In a review of all paid claims reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank from 1992 to 2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was determined.1 For the time periods 1992–1996, 1997–2002, 2003–2008,and 2009–2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was 57.6, 51.5, 40.0, and 25.9, representing an astounding 55% decrease in paid claims from 1992 to 2014 (FIGURE).1

The majority of claims result in no payment

In a review of the experience of a nationwide professional liability insurer from 1991 to 2005, only 22% of claims resulted in a payment.2 In this study, for obstetrics and gynecology and gynecologic surgery, only 11% and 8% of claims, respectively, resulted in a payment.2 However, being named in a malpractice claim results in significant stress for a physician and requires a great deal of work and time to defend.

In another study using data from the Physician Insurer’s Association of America, among 10,915 claims closed from 2005 to 2014, 59.5% were dropped, withdrawn, or dismissed; 27.7% were settled; 2.5% were resolved using an alternative dispute resolution process; 1.8% were uncategorized; and 8.6% went to trial.3 Of the cases that went to trial, 87% resulted in a verdict for the physician and 13% resulted in a verdict for the plaintiff.3

Not as good news: Payments per claim and claims settling for a payment > $1 million are increasing

In the period 1992–1996, the average payment per paid claim in the field of obstetrics and gynecology was $387,186, rising to $447,034 in 2009–2014—a 16% increase.1 From 2004 to 2010, million dollar payments occurred in about 8% of cases of paid claims, but they represent 36% of the total of all paid claims.4 In the time periods 1992–1996 and 2009–2014, payments greater than $1 million occurred in 6% and 8% of paid claims, respectively.1

Claims settled for much more than $1 million are of great concern to physicians because the payment may exceed their policy limit, creating a complex legal problem that may take time to resolve. In some cases, where the award is greater than the insurance policy limit, aggressive plaintiff attorneys have obtained a lien on the defendant physician’s home pending settlement of the case. When a multimillion dollar payment is made to settle a professional liability claim, it can greatly influence physician practice and change hospital policies. Frequently, following a multimillion dollar payment a physician may decide to limit their practice to low-risk cases or retire from the practice of medicine.

Liability premiums are stable or decreasing

From 2014 to 2019, my ObGyn professional liability insurance premiums decreased by 18%. During the same time period, my colleagues who practice surgical gynecology (no obstetrics) had a premium decrease of 22%. Insurers use a complex algorithm to determine annual liability insurance premiums, and premiums for ObGyns may not have stabilized or decreased in all regions. Take this Instant Poll:

Create your own user feedback survey

Reform of the liability tort system

Litigation policies and practices that reduce liability risk reduce total medical liability losses. Policies that have helped to constrain medical liability risk include state constitutional amendments limiting payments for pain and suffering, caps on compensation to plaintiff attorneys, increased early resolution programs that compensate patients who experience an adverse event and no-fault conflict resolution programs.5 In 2003, Texas implemented a comprehensive package of tort reform laws. Experts believe the reforms decreased the financial burden of professional liability insurance6 and led to less defensive medical practices, reducing excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests.

Medical factors contributing to a decrease in claims

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine released the report, “To Err is Human,” which galvanized health care systems to deploy systems of care that reduce the rate of adverse patient outcomes.7 Over the past 20 years, health systems have implemented quality improvement programs in obstetrics and gynecology that have contributed to a reduction in the rate of adverse patient outcomes. This may have contributed to the decrease in the rate of paid claims.

In a quasi-experimental study performed in 13 health systems, 7 interventions were implemented with the goal of improving outcomes and reducing medical liability. The 7 interventions included8:

- an elective induction bundle focused on the safe use of oxytocin

- an augmentation bundle focused on early intervention for possible fetal metabolic acidosis

- an operative vaginal delivery bundle

- TeamSTEPPS teamwork training to improve the quality of communication

- best practices education with a focus on electronic fetal monitoring

- regular performance feedback to hospitals and clinicians

- implementation of a quality improvement collaboration to support implementation of the interventions.

During the two-year baseline period prior to the intervention there were 185,373 deliveries with 6.7 perinatal claims made per 10,000 deliveries and 1.3 claims paid per 10,000 deliveries. Following the intervention, the rate of claims made and claims paid per 10,000 deliveries decreased by 22% and 37%, respectively. In addition there was a marked decrease in claims over $1 million paid, greatly limiting total financial liability losses.

Experts with vast experience in obstetrics and obstetric liability litigation have identified 4 priority interventions that may improve outcomes and mitigate liability risk, including: 1) 24-hour in-house physician coverage of an obstetrics service, 2) a conservative approach to trial of labor after a prior cesarean delivery, 3) utilization of a comprehensive, standardized event note in cases of a shoulder dystocia, and 4) judicious use of oxytocin, misoprostol, and magnesium sulfate.9

Other health system interventions that may contribute to a reduction in claims include:

- systematic improvement in the quality of communication among physicians and nurses through the use of team training, preprocedure huddles, and time-out processes10

- rapid response systems to rescue hospital patients with worrisome vital signs11

- standardized responses to a worrisome category 2 or 3 fetal heart-rate tracing12

- rapid recognition, evaluation, and treatment of women with hemorrhage, severe hypertension, sepsis, and venous thromboembolism13

- identification and referral of high-risk patients to tertiary centers14

- closed loop communication of critical imaging and laboratory results15

- universal insurance coverage for health care including contraception, obstetrics, and pediatric care.

Medical liability risk is an important practice issue because it causes excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests and often traumatizes clinicians, which can result in burnout. In the 1980s and 1990s, medical liability litigation reached a crescendo and was a prominent concern among obstetrician-gynecologists. The good news is that, for ObGyns, liability risk has stabilized. Hopefully our resolute efforts to continuously improve the quality of care will result in a long-term reduction in medical liability risk.

Medical professional liability claims (claims) are a major cause of worry and agony for physicians who are dedicated to optimizing the health of all their patients. Among physicians, those who practice neurosurgery, thoracic surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology have the greatest rate of making a payment on a claim per year of practice.1 Physicians who practice psychiatry, pediatrics, pathology, and internal medicine have the lowest rate of making a payment on a claim. Among the physicians in high-risk specialties, greater than 90% will have a claim filed against them during their career.2 Although professional liability exposure reached a crisis during the 1980s and 1990s, recent data have shown a decrease in overall professional liability risk.

The good news: Paid claims per 1,000 ObGyns have decreased greatly

In a review of all paid claims reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank from 1992 to 2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was determined.1 For the time periods 1992–1996, 1997–2002, 2003–2008,and 2009–2014, the annual rate of paid claims per 1,000 ObGyn physician-years was 57.6, 51.5, 40.0, and 25.9, representing an astounding 55% decrease in paid claims from 1992 to 2014 (FIGURE).1

The majority of claims result in no payment

In a review of the experience of a nationwide professional liability insurer from 1991 to 2005, only 22% of claims resulted in a payment.2 In this study, for obstetrics and gynecology and gynecologic surgery, only 11% and 8% of claims, respectively, resulted in a payment.2 However, being named in a malpractice claim results in significant stress for a physician and requires a great deal of work and time to defend.

In another study using data from the Physician Insurer’s Association of America, among 10,915 claims closed from 2005 to 2014, 59.5% were dropped, withdrawn, or dismissed; 27.7% were settled; 2.5% were resolved using an alternative dispute resolution process; 1.8% were uncategorized; and 8.6% went to trial.3 Of the cases that went to trial, 87% resulted in a verdict for the physician and 13% resulted in a verdict for the plaintiff.3

Not as good news: Payments per claim and claims settling for a payment > $1 million are increasing

In the period 1992–1996, the average payment per paid claim in the field of obstetrics and gynecology was $387,186, rising to $447,034 in 2009–2014—a 16% increase.1 From 2004 to 2010, million dollar payments occurred in about 8% of cases of paid claims, but they represent 36% of the total of all paid claims.4 In the time periods 1992–1996 and 2009–2014, payments greater than $1 million occurred in 6% and 8% of paid claims, respectively.1

Claims settled for much more than $1 million are of great concern to physicians because the payment may exceed their policy limit, creating a complex legal problem that may take time to resolve. In some cases, where the award is greater than the insurance policy limit, aggressive plaintiff attorneys have obtained a lien on the defendant physician’s home pending settlement of the case. When a multimillion dollar payment is made to settle a professional liability claim, it can greatly influence physician practice and change hospital policies. Frequently, following a multimillion dollar payment a physician may decide to limit their practice to low-risk cases or retire from the practice of medicine.

Liability premiums are stable or decreasing

From 2014 to 2019, my ObGyn professional liability insurance premiums decreased by 18%. During the same time period, my colleagues who practice surgical gynecology (no obstetrics) had a premium decrease of 22%. Insurers use a complex algorithm to determine annual liability insurance premiums, and premiums for ObGyns may not have stabilized or decreased in all regions. Take this Instant Poll:

Create your own user feedback survey

Reform of the liability tort system

Litigation policies and practices that reduce liability risk reduce total medical liability losses. Policies that have helped to constrain medical liability risk include state constitutional amendments limiting payments for pain and suffering, caps on compensation to plaintiff attorneys, increased early resolution programs that compensate patients who experience an adverse event and no-fault conflict resolution programs.5 In 2003, Texas implemented a comprehensive package of tort reform laws. Experts believe the reforms decreased the financial burden of professional liability insurance6 and led to less defensive medical practices, reducing excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests.

Medical factors contributing to a decrease in claims

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine released the report, “To Err is Human,” which galvanized health care systems to deploy systems of care that reduce the rate of adverse patient outcomes.7 Over the past 20 years, health systems have implemented quality improvement programs in obstetrics and gynecology that have contributed to a reduction in the rate of adverse patient outcomes. This may have contributed to the decrease in the rate of paid claims.

In a quasi-experimental study performed in 13 health systems, 7 interventions were implemented with the goal of improving outcomes and reducing medical liability. The 7 interventions included8:

- an elective induction bundle focused on the safe use of oxytocin

- an augmentation bundle focused on early intervention for possible fetal metabolic acidosis

- an operative vaginal delivery bundle

- TeamSTEPPS teamwork training to improve the quality of communication

- best practices education with a focus on electronic fetal monitoring

- regular performance feedback to hospitals and clinicians

- implementation of a quality improvement collaboration to support implementation of the interventions.

During the two-year baseline period prior to the intervention there were 185,373 deliveries with 6.7 perinatal claims made per 10,000 deliveries and 1.3 claims paid per 10,000 deliveries. Following the intervention, the rate of claims made and claims paid per 10,000 deliveries decreased by 22% and 37%, respectively. In addition there was a marked decrease in claims over $1 million paid, greatly limiting total financial liability losses.

Experts with vast experience in obstetrics and obstetric liability litigation have identified 4 priority interventions that may improve outcomes and mitigate liability risk, including: 1) 24-hour in-house physician coverage of an obstetrics service, 2) a conservative approach to trial of labor after a prior cesarean delivery, 3) utilization of a comprehensive, standardized event note in cases of a shoulder dystocia, and 4) judicious use of oxytocin, misoprostol, and magnesium sulfate.9

Other health system interventions that may contribute to a reduction in claims include:

- systematic improvement in the quality of communication among physicians and nurses through the use of team training, preprocedure huddles, and time-out processes10

- rapid response systems to rescue hospital patients with worrisome vital signs11

- standardized responses to a worrisome category 2 or 3 fetal heart-rate tracing12

- rapid recognition, evaluation, and treatment of women with hemorrhage, severe hypertension, sepsis, and venous thromboembolism13

- identification and referral of high-risk patients to tertiary centers14

- closed loop communication of critical imaging and laboratory results15

- universal insurance coverage for health care including contraception, obstetrics, and pediatric care.

Medical liability risk is an important practice issue because it causes excessive use of imaging and laboratory tests and often traumatizes clinicians, which can result in burnout. In the 1980s and 1990s, medical liability litigation reached a crescendo and was a prominent concern among obstetrician-gynecologists. The good news is that, for ObGyns, liability risk has stabilized. Hopefully our resolute efforts to continuously improve the quality of care will result in a long-term reduction in medical liability risk.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992–2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-e6.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, et al. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Quality. 2014;36:43-53.

- Cardoso R, Zarin W, Nincic V, et al. Evaluative reports on medical malpractice policies in obstetrics: a rapid scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:181.

- Stewart RM, Geoghegan K, Myers JG, et al. Malpractice risk and costs are significantly reduced after tort reform. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:463-467.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Riley W, Meredith LW, Price R, et al. Decreasing malpractice claims by reducing preventable perinatal harm. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(suppl 3):2453-2471.

- Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1279-1283.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499.

- Patel S, Gillon SA, Jones DA. Rapid response systems: recognition and rescue of the deteriorating hospital patient. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:143-148.

- Clark SL, Hamilton EF, Garite TJ, et al. The limits of electronic fetal heart rate monitoring in the prevention of neonatal metabolic acidemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:163.e1-163.e6.

- The Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Healthcare website. www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- Zahn CM, Remick A, Catalano A, et al. Levels of maternal care verification pilot: translating guidance into practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1401-1406.

- Zuccotti G, Maloney FL, Feblowitz J, et al. Reducing risk with clinical decision support: a study of closed malpractice claims. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5:746-756.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992–2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-e6.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, et al. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Quality. 2014;36:43-53.

- Cardoso R, Zarin W, Nincic V, et al. Evaluative reports on medical malpractice policies in obstetrics: a rapid scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:181.

- Stewart RM, Geoghegan K, Myers JG, et al. Malpractice risk and costs are significantly reduced after tort reform. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:463-467.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Riley W, Meredith LW, Price R, et al. Decreasing malpractice claims by reducing preventable perinatal harm. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(suppl 3):2453-2471.

- Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1279-1283.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499.

- Patel S, Gillon SA, Jones DA. Rapid response systems: recognition and rescue of the deteriorating hospital patient. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:143-148.

- Clark SL, Hamilton EF, Garite TJ, et al. The limits of electronic fetal heart rate monitoring in the prevention of neonatal metabolic acidemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:163.e1-163.e6.

- The Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Healthcare website. www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- Zahn CM, Remick A, Catalano A, et al. Levels of maternal care verification pilot: translating guidance into practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1401-1406.

- Zuccotti G, Maloney FL, Feblowitz J, et al. Reducing risk with clinical decision support: a study of closed malpractice claims. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5:746-756.

Are sweeping efforts to reduce primary CD rates associated with an increase in maternal or neonatal AEs?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.

- Rosenbloom JI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. New labor management guidelines and changes in cesarean delivery patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:689.e1-689.e8.

- Vadnais MA, Hacker MR, Shah NT, et al. Quality improvement initiatives lead to reduction in nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rate. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:53-61.

- Zipori Y, Grunwald O, Ginsberg Y, et al. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220:191.e1-191.e7.

- Thuillier C, Roy S, Peyronnet V, et al. Impact of recommended changes in labor management for prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:341.e1-341.e9.

- Gimovsky AC, Berghella V. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged second stage: extending the time limit vs usual guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:361.e1-361.e6.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.

- Rosenbloom JI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. New labor management guidelines and changes in cesarean delivery patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:689.e1-689.e8.

- Vadnais MA, Hacker MR, Shah NT, et al. Quality improvement initiatives lead to reduction in nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rate. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:53-61.

- Zipori Y, Grunwald O, Ginsberg Y, et al. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220:191.e1-191.e7.

- Thuillier C, Roy S, Peyronnet V, et al. Impact of recommended changes in labor management for prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:341.e1-341.e9.

- Gimovsky AC, Berghella V. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged second stage: extending the time limit vs usual guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:361.e1-361.e6.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.