User login

No clear winner in Pfannenstiel vs. vertical incision for high BMI cesareans

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Wound complication rates were similar with Pfannenstiel and vertical incisions in women with obesity.

Major finding: At 6 weeks, 21.1% of vertical incision recipients and 18.6% of Pfannenstiel recipients had wound complications.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 91 women with obesity receiving cesarean section.

Disclosures: Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

Tenofovir didn’t prevent hepatitis B transmission to newborns

Prenatal tenofovir didn’t reduce the rate of hepatitis B among infants born to women infected with the virus.

Among 322 6-month-olds, the rate of HBV transmission was 0 in those whose mothers received the antiviral during pregnancy and 2% among those whose mothers received placebo – not a statistically significant difference, Gonzague Jourdain, MD, and his colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study randomized 331 pregnant women with proven HBV infections to either tenofovir or placebo from 28 weeks’ gestation to 2 months post partum. All infants received HBV immune globulin at birth, and HBV vaccine at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months. The primary endpoint was confirmed HBV infection in the infant at 6 months.

Women were a mean of 28 weeks pregnant at baseline, with a mean viral load of 8.0 log10 IU/mL. Most women (about 90% of each group) had an HBV DNA of more than 200,000 IU/mL – a level associated with an increased risk of perinatal HBV infection despite vaccination.

There were 322 deliveries, resulting in 319 singletons, two pairs of twins, and one stillbirth. Postpartum infant treatment was quick, with a median of 1.3 hours from birth to administration of immune globulin and a median of 1.2 hours to administration of the first dose of the vaccine.

At 6 months, there were no HBV infections in the tenofovir-exposed group and 3 (2%) in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference (P = .12).

Tenofovir was safe for both mother and fetus, with no significant adverse events in either group. The incidence of elevated maternal alanine aminotransferase level (more than 300 IU/L) was 6% in the tenofovir group and 3% in the placebo group, also a nonsignificant finding.

Dr. Jourdain and his colleagues noted that the 2% transmission rate in the placebo group is considerably lower than the 7% seen in similar studies and could be related to the rapid postpartum administration of HBV immune globulin and vaccine. If this is the case, prenatal antivirals could be more effective in countries where postpartum treatment is delayed or inconsistent.

“Maternal use of tenofovir may prevent transmissions that would occur when the birth dose is delayed, but its exact timing has not been reported consistently in previous perinatal studies,” the team said.

Another question is whether the stringent, 5-dose infant HBV vaccine series required in Thailand is simply more effective than schedules that have fewer doses or are combined with other vaccines and delivered later.

“It remains unclear whether the administration of more vaccine doses is more efficacious than the administration of the three vaccine doses that is recommended in the United States and by the World Health Organization.”

Dr. Jourdain had no financial disclosures relevant to the study, which was sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Jourdain G et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-23.

The trial by Jourdain et al. – although described by the authors as negative – “puts down an intriguing marker attesting to the possibility that rapidly phasing in the timely administration of a safe monovalent HBV vaccine within a few hours after birth could contribute to the interruption of mother-to-child transmission and avert preventable HBV infections in childhood,” Geoffrey Dusheiko, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:952-3).

The World Health Organization supports HBV vaccine schedules of three or four doses, which are usually given as part of a combination immunization protocol beginning at 6 weeks of age. “Currently, HBV vaccination is most frequently administered as a pentavalent or hexavalent vaccine as part of the Expanded Program on Immunization, typically in combination with vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type B,” wrote Dr. Dusheiko. “Paradoxically, support for combination vaccines within an integrated EPI schedule has unwittingly but undesirably shifted thinking and policy away from HBV vaccination at birth. This gap in vaccine strategy is disadvantageous.”

While the study doesn’t support tenofovir for maternal prophylaxis, it does imply value for treating the infant with immune globulin and HBV vaccination soon after birth. Delivering this kind of care globally will be challenging, but it’s entirely feasible, Dr. Dusheiko said.

“It is necessary to analyze regional data to assess the requirements for implementing vaccination at birth, including ... the training of otherwise unskilled birth attendants to deliver monovalent HBV vaccine at the same time as the vaccines against polio and bacille Calmette–Guérin. Importantly, the use of monovalent HBV vaccine would also require governmental or nongovernmental support. HBV vaccination at birth, despite the challenges for poverty-affected countries to deliver vaccination in rural and isolated locales, is feasible.”

Dr. Dusheiko is a hepatologist at the University College London School of Medicine and King’s College Hospital, London.

The trial by Jourdain et al. – although described by the authors as negative – “puts down an intriguing marker attesting to the possibility that rapidly phasing in the timely administration of a safe monovalent HBV vaccine within a few hours after birth could contribute to the interruption of mother-to-child transmission and avert preventable HBV infections in childhood,” Geoffrey Dusheiko, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:952-3).

The World Health Organization supports HBV vaccine schedules of three or four doses, which are usually given as part of a combination immunization protocol beginning at 6 weeks of age. “Currently, HBV vaccination is most frequently administered as a pentavalent or hexavalent vaccine as part of the Expanded Program on Immunization, typically in combination with vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type B,” wrote Dr. Dusheiko. “Paradoxically, support for combination vaccines within an integrated EPI schedule has unwittingly but undesirably shifted thinking and policy away from HBV vaccination at birth. This gap in vaccine strategy is disadvantageous.”

While the study doesn’t support tenofovir for maternal prophylaxis, it does imply value for treating the infant with immune globulin and HBV vaccination soon after birth. Delivering this kind of care globally will be challenging, but it’s entirely feasible, Dr. Dusheiko said.

“It is necessary to analyze regional data to assess the requirements for implementing vaccination at birth, including ... the training of otherwise unskilled birth attendants to deliver monovalent HBV vaccine at the same time as the vaccines against polio and bacille Calmette–Guérin. Importantly, the use of monovalent HBV vaccine would also require governmental or nongovernmental support. HBV vaccination at birth, despite the challenges for poverty-affected countries to deliver vaccination in rural and isolated locales, is feasible.”

Dr. Dusheiko is a hepatologist at the University College London School of Medicine and King’s College Hospital, London.

The trial by Jourdain et al. – although described by the authors as negative – “puts down an intriguing marker attesting to the possibility that rapidly phasing in the timely administration of a safe monovalent HBV vaccine within a few hours after birth could contribute to the interruption of mother-to-child transmission and avert preventable HBV infections in childhood,” Geoffrey Dusheiko, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:952-3).

The World Health Organization supports HBV vaccine schedules of three or four doses, which are usually given as part of a combination immunization protocol beginning at 6 weeks of age. “Currently, HBV vaccination is most frequently administered as a pentavalent or hexavalent vaccine as part of the Expanded Program on Immunization, typically in combination with vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type B,” wrote Dr. Dusheiko. “Paradoxically, support for combination vaccines within an integrated EPI schedule has unwittingly but undesirably shifted thinking and policy away from HBV vaccination at birth. This gap in vaccine strategy is disadvantageous.”

While the study doesn’t support tenofovir for maternal prophylaxis, it does imply value for treating the infant with immune globulin and HBV vaccination soon after birth. Delivering this kind of care globally will be challenging, but it’s entirely feasible, Dr. Dusheiko said.

“It is necessary to analyze regional data to assess the requirements for implementing vaccination at birth, including ... the training of otherwise unskilled birth attendants to deliver monovalent HBV vaccine at the same time as the vaccines against polio and bacille Calmette–Guérin. Importantly, the use of monovalent HBV vaccine would also require governmental or nongovernmental support. HBV vaccination at birth, despite the challenges for poverty-affected countries to deliver vaccination in rural and isolated locales, is feasible.”

Dr. Dusheiko is a hepatologist at the University College London School of Medicine and King’s College Hospital, London.

Prenatal tenofovir didn’t reduce the rate of hepatitis B among infants born to women infected with the virus.

Among 322 6-month-olds, the rate of HBV transmission was 0 in those whose mothers received the antiviral during pregnancy and 2% among those whose mothers received placebo – not a statistically significant difference, Gonzague Jourdain, MD, and his colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study randomized 331 pregnant women with proven HBV infections to either tenofovir or placebo from 28 weeks’ gestation to 2 months post partum. All infants received HBV immune globulin at birth, and HBV vaccine at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months. The primary endpoint was confirmed HBV infection in the infant at 6 months.

Women were a mean of 28 weeks pregnant at baseline, with a mean viral load of 8.0 log10 IU/mL. Most women (about 90% of each group) had an HBV DNA of more than 200,000 IU/mL – a level associated with an increased risk of perinatal HBV infection despite vaccination.

There were 322 deliveries, resulting in 319 singletons, two pairs of twins, and one stillbirth. Postpartum infant treatment was quick, with a median of 1.3 hours from birth to administration of immune globulin and a median of 1.2 hours to administration of the first dose of the vaccine.

At 6 months, there were no HBV infections in the tenofovir-exposed group and 3 (2%) in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference (P = .12).

Tenofovir was safe for both mother and fetus, with no significant adverse events in either group. The incidence of elevated maternal alanine aminotransferase level (more than 300 IU/L) was 6% in the tenofovir group and 3% in the placebo group, also a nonsignificant finding.

Dr. Jourdain and his colleagues noted that the 2% transmission rate in the placebo group is considerably lower than the 7% seen in similar studies and could be related to the rapid postpartum administration of HBV immune globulin and vaccine. If this is the case, prenatal antivirals could be more effective in countries where postpartum treatment is delayed or inconsistent.

“Maternal use of tenofovir may prevent transmissions that would occur when the birth dose is delayed, but its exact timing has not been reported consistently in previous perinatal studies,” the team said.

Another question is whether the stringent, 5-dose infant HBV vaccine series required in Thailand is simply more effective than schedules that have fewer doses or are combined with other vaccines and delivered later.

“It remains unclear whether the administration of more vaccine doses is more efficacious than the administration of the three vaccine doses that is recommended in the United States and by the World Health Organization.”

Dr. Jourdain had no financial disclosures relevant to the study, which was sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Jourdain G et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-23.

Prenatal tenofovir didn’t reduce the rate of hepatitis B among infants born to women infected with the virus.

Among 322 6-month-olds, the rate of HBV transmission was 0 in those whose mothers received the antiviral during pregnancy and 2% among those whose mothers received placebo – not a statistically significant difference, Gonzague Jourdain, MD, and his colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study randomized 331 pregnant women with proven HBV infections to either tenofovir or placebo from 28 weeks’ gestation to 2 months post partum. All infants received HBV immune globulin at birth, and HBV vaccine at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months. The primary endpoint was confirmed HBV infection in the infant at 6 months.

Women were a mean of 28 weeks pregnant at baseline, with a mean viral load of 8.0 log10 IU/mL. Most women (about 90% of each group) had an HBV DNA of more than 200,000 IU/mL – a level associated with an increased risk of perinatal HBV infection despite vaccination.

There were 322 deliveries, resulting in 319 singletons, two pairs of twins, and one stillbirth. Postpartum infant treatment was quick, with a median of 1.3 hours from birth to administration of immune globulin and a median of 1.2 hours to administration of the first dose of the vaccine.

At 6 months, there were no HBV infections in the tenofovir-exposed group and 3 (2%) in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference (P = .12).

Tenofovir was safe for both mother and fetus, with no significant adverse events in either group. The incidence of elevated maternal alanine aminotransferase level (more than 300 IU/L) was 6% in the tenofovir group and 3% in the placebo group, also a nonsignificant finding.

Dr. Jourdain and his colleagues noted that the 2% transmission rate in the placebo group is considerably lower than the 7% seen in similar studies and could be related to the rapid postpartum administration of HBV immune globulin and vaccine. If this is the case, prenatal antivirals could be more effective in countries where postpartum treatment is delayed or inconsistent.

“Maternal use of tenofovir may prevent transmissions that would occur when the birth dose is delayed, but its exact timing has not been reported consistently in previous perinatal studies,” the team said.

Another question is whether the stringent, 5-dose infant HBV vaccine series required in Thailand is simply more effective than schedules that have fewer doses or are combined with other vaccines and delivered later.

“It remains unclear whether the administration of more vaccine doses is more efficacious than the administration of the three vaccine doses that is recommended in the United States and by the World Health Organization.”

Dr. Jourdain had no financial disclosures relevant to the study, which was sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Jourdain G et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-23.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Tenofovir was no different than placebo in preventing HBV transmission to newborns.

Major finding: The transmission rate was 0% in the tenofovir group and 2% in the placebo group (P = .12).

Study details: The study randomized 331 pregnant women to tenofovir or placebo from gestational week 28 to 2 months postpartum.

Disclosures: Dr. Jourdain had no financial disclosures; the National Institute of Child Health and Development sponsored the study.

Source: Jourdain G et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-23.

Adding hypertension in pregnancy doesn’t refine ASCVD risk prediction tool

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The first-ever study to examine the clinical utility of incorporating a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator in an effort to better delineate risk in women failed to show any added benefit.

But that doesn’t mean such a history is without value in daily clinical practice, Jennifer J. Stuart, ScD, asserted at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“While we did not demonstrate that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy improved cardiovascular risk discrimination in women, we do still believe – and I still believe – that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy remain an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease in women,” said Dr. Stuart of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

“In this latest analysis we’ve demonstrated over a fourfold increased risk of chronic hypertension in these women in the first 5 years after delivery. So we do see increased risk very soon after delivery, and it persists for decades. And hypertensive disorders of pregnancy as a risk marker does offer practical advantages: ease of ascertainment, low cost, and availability earlier in life,” the researcher noted.

Her study hypothesis was that adding hypertensive disorders of pregnancy – that is, gestational hypertension and preeclampsia – and parity to the current ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator would enhance the tool’s predictive tool’s power in women.

“We wanted to know if a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy can be leveraged to capture women currently being missed in screening,” she explained.

Her expectation that this would be the case was based on solid evidence that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies, are associated with subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular events. For example, a meta-analysis of published studies involving nearly 3.5 million women, including almost 200,000 with a history of preeclampsia, showed that preeclampsia was associated with a 2.16-fold increased risk of ischemic heart disease during 11.7 years of follow-up (BMJ. 2007 Nov 10;335[7627]:974). This meta-analysis was among the evidence that persuaded the AHA in 2011 to formally add hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to the list of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women (Circulation. 2011 Mar 22;123[11]:1243-62).

Dr. Stuart also incorporated parity in her investigational revised ASCVD risk model, because parity has been shown to be an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease in a relationship described by a J-shaped curve.

She put the souped-up risk prediction model to the test by separately applying it and the current version to data from the longitudinal prospective Nurses’ Health Study II. For this analysis, nearly 68,000 female registered nurses were followed for new diseases every 2 years from 1989, when they were aged 25-42, through 2013. She and her coinvestigators applied the two 10-year risk-prediction models to the overall cohort and again separately to women at aged 40-49 and 50-59.

The bottom line: This might be because the nurses comprise a relatively low-risk population. Also, even though hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated with 10-year cardiovascular disease risk independent of the established risk factors, there may be enough overlap that the standard risk factors sufficiently capture the risk.

“It may be that the information on history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be ascertained in the 20s and 30s, rather than waiting until age 40 or later, when we generally apply cardiovascular risk scores in practice. That [earlier assessment] may be a really important and valuable opportunity to identify these women at high risk and utilize primary prevention,” according to Dr. Stuart.

What’s next? “I’m certainly interested in educating these women about their increased risk. This is not something that’s done consistently across the country and across practices, and we really believe this is an important message for women to get when they deliver these pregnancies,” she added.

Dr. Stuart reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Stuart JJ. AHA Scientific Sessions.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The first-ever study to examine the clinical utility of incorporating a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator in an effort to better delineate risk in women failed to show any added benefit.

But that doesn’t mean such a history is without value in daily clinical practice, Jennifer J. Stuart, ScD, asserted at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“While we did not demonstrate that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy improved cardiovascular risk discrimination in women, we do still believe – and I still believe – that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy remain an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease in women,” said Dr. Stuart of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

“In this latest analysis we’ve demonstrated over a fourfold increased risk of chronic hypertension in these women in the first 5 years after delivery. So we do see increased risk very soon after delivery, and it persists for decades. And hypertensive disorders of pregnancy as a risk marker does offer practical advantages: ease of ascertainment, low cost, and availability earlier in life,” the researcher noted.

Her study hypothesis was that adding hypertensive disorders of pregnancy – that is, gestational hypertension and preeclampsia – and parity to the current ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator would enhance the tool’s predictive tool’s power in women.

“We wanted to know if a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy can be leveraged to capture women currently being missed in screening,” she explained.

Her expectation that this would be the case was based on solid evidence that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies, are associated with subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular events. For example, a meta-analysis of published studies involving nearly 3.5 million women, including almost 200,000 with a history of preeclampsia, showed that preeclampsia was associated with a 2.16-fold increased risk of ischemic heart disease during 11.7 years of follow-up (BMJ. 2007 Nov 10;335[7627]:974). This meta-analysis was among the evidence that persuaded the AHA in 2011 to formally add hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to the list of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women (Circulation. 2011 Mar 22;123[11]:1243-62).

Dr. Stuart also incorporated parity in her investigational revised ASCVD risk model, because parity has been shown to be an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease in a relationship described by a J-shaped curve.

She put the souped-up risk prediction model to the test by separately applying it and the current version to data from the longitudinal prospective Nurses’ Health Study II. For this analysis, nearly 68,000 female registered nurses were followed for new diseases every 2 years from 1989, when they were aged 25-42, through 2013. She and her coinvestigators applied the two 10-year risk-prediction models to the overall cohort and again separately to women at aged 40-49 and 50-59.

The bottom line: This might be because the nurses comprise a relatively low-risk population. Also, even though hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated with 10-year cardiovascular disease risk independent of the established risk factors, there may be enough overlap that the standard risk factors sufficiently capture the risk.

“It may be that the information on history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be ascertained in the 20s and 30s, rather than waiting until age 40 or later, when we generally apply cardiovascular risk scores in practice. That [earlier assessment] may be a really important and valuable opportunity to identify these women at high risk and utilize primary prevention,” according to Dr. Stuart.

What’s next? “I’m certainly interested in educating these women about their increased risk. This is not something that’s done consistently across the country and across practices, and we really believe this is an important message for women to get when they deliver these pregnancies,” she added.

Dr. Stuart reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Stuart JJ. AHA Scientific Sessions.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The first-ever study to examine the clinical utility of incorporating a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator in an effort to better delineate risk in women failed to show any added benefit.

But that doesn’t mean such a history is without value in daily clinical practice, Jennifer J. Stuart, ScD, asserted at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“While we did not demonstrate that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy improved cardiovascular risk discrimination in women, we do still believe – and I still believe – that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy remain an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease in women,” said Dr. Stuart of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

“In this latest analysis we’ve demonstrated over a fourfold increased risk of chronic hypertension in these women in the first 5 years after delivery. So we do see increased risk very soon after delivery, and it persists for decades. And hypertensive disorders of pregnancy as a risk marker does offer practical advantages: ease of ascertainment, low cost, and availability earlier in life,” the researcher noted.

Her study hypothesis was that adding hypertensive disorders of pregnancy – that is, gestational hypertension and preeclampsia – and parity to the current ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator would enhance the tool’s predictive tool’s power in women.

“We wanted to know if a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy can be leveraged to capture women currently being missed in screening,” she explained.

Her expectation that this would be the case was based on solid evidence that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies, are associated with subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular events. For example, a meta-analysis of published studies involving nearly 3.5 million women, including almost 200,000 with a history of preeclampsia, showed that preeclampsia was associated with a 2.16-fold increased risk of ischemic heart disease during 11.7 years of follow-up (BMJ. 2007 Nov 10;335[7627]:974). This meta-analysis was among the evidence that persuaded the AHA in 2011 to formally add hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to the list of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women (Circulation. 2011 Mar 22;123[11]:1243-62).

Dr. Stuart also incorporated parity in her investigational revised ASCVD risk model, because parity has been shown to be an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease in a relationship described by a J-shaped curve.

She put the souped-up risk prediction model to the test by separately applying it and the current version to data from the longitudinal prospective Nurses’ Health Study II. For this analysis, nearly 68,000 female registered nurses were followed for new diseases every 2 years from 1989, when they were aged 25-42, through 2013. She and her coinvestigators applied the two 10-year risk-prediction models to the overall cohort and again separately to women at aged 40-49 and 50-59.

The bottom line: This might be because the nurses comprise a relatively low-risk population. Also, even though hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated with 10-year cardiovascular disease risk independent of the established risk factors, there may be enough overlap that the standard risk factors sufficiently capture the risk.

“It may be that the information on history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be ascertained in the 20s and 30s, rather than waiting until age 40 or later, when we generally apply cardiovascular risk scores in practice. That [earlier assessment] may be a really important and valuable opportunity to identify these women at high risk and utilize primary prevention,” according to Dr. Stuart.

What’s next? “I’m certainly interested in educating these women about their increased risk. This is not something that’s done consistently across the country and across practices, and we really believe this is an important message for women to get when they deliver these pregnancies,” she added.

Dr. Stuart reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Stuart JJ. AHA Scientific Sessions.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: The ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator doesn’t do a better job of predicting 10-year risk in women when a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy is added into the formula.

Major finding: Incorporating a woman’s history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator doesn’t improve the tool’s accuracy in predicting 10-year risk.

Study details: An analysis of data from the longitudinal, prospective Nurses’ Health Study II.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Stuart JJ. AHA Scientific Sessions.

Abruptio placenta brings increased cardiovascular risk – and soon

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Women who experience placental abruption are at significantly increased risk for multiple forms of cardiovascular disease beginning within the first few years after their pregnancy complication, according to a study of more than 1.6 million California women.

While gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction have previously all been shown to be associated with increased risk of incident cardiovascular disease, this huge California study provides the first strong epidemiologic evidence that placental abruption is as well. Prior studies looking at the issue have been underpowered, Michael J. Healey, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our hypothesis is that there might be some type of shared mechanism, probably involving microvascular dysfunction, that explains the relationships we see between these pregnancy complications and increased near-term risk of cardiovascular disease,” he explained in an interview.

Dr. Healy, a hospitalist attached to the heart failure service at the University of California, San Francisco, presented a retrospective study of a multiethnic cohort comprising 1,614,950 parous women aged 15-50 years who participated in the California Healthcare Cost and Utility Project during 2005-2009. Placental abruption occurred in 15,057 of them at a mean age of 29.2 years.

During a median 4.9 years of follow-up, women who experienced abruptio placenta were at 6% increased risk for heart failure, 11% greater risk for MI, 8% increased risk for hypertensive urgency, and 2% greater risk for myocardial infarction with no obstructive atherosclerosis (MINOCA) in an age- and race-adjusted analysis. All of these were statistically significant differences.

Of note, however, in a multivariate analysis fully adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, as well as hypercoagulability, preterm birth, grand multiparity, and insurance status, placental abruption was independently associated with a 2.14-fold risk of MINOCA, but it was no longer linked to significantly increased risks of the other cardiovascular events.

The implication is that the increased risk of these other forms of cardiovascular disease is mediated through the women’s increased prevalence of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, whereas a novel mechanism – most likely microvascular dysfunction – underlies the association between placental abruption and MINOCA, according to Dr. Healy.

He plans to extend this research by taking a look at the relationship between placental abruption and the various subtypes of MINOCA, including coronary dissection, vasospasm, thrombophilia disorders, and stress cardiomyopathy, in order to examine whether the increased risk posed by placental abruption is concentrated in certain forms of MINOCA. Data on MINOCA subtypes were recorded as part of the California project.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Women who experience placental abruption are at significantly increased risk for multiple forms of cardiovascular disease beginning within the first few years after their pregnancy complication, according to a study of more than 1.6 million California women.

While gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction have previously all been shown to be associated with increased risk of incident cardiovascular disease, this huge California study provides the first strong epidemiologic evidence that placental abruption is as well. Prior studies looking at the issue have been underpowered, Michael J. Healey, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our hypothesis is that there might be some type of shared mechanism, probably involving microvascular dysfunction, that explains the relationships we see between these pregnancy complications and increased near-term risk of cardiovascular disease,” he explained in an interview.

Dr. Healy, a hospitalist attached to the heart failure service at the University of California, San Francisco, presented a retrospective study of a multiethnic cohort comprising 1,614,950 parous women aged 15-50 years who participated in the California Healthcare Cost and Utility Project during 2005-2009. Placental abruption occurred in 15,057 of them at a mean age of 29.2 years.

During a median 4.9 years of follow-up, women who experienced abruptio placenta were at 6% increased risk for heart failure, 11% greater risk for MI, 8% increased risk for hypertensive urgency, and 2% greater risk for myocardial infarction with no obstructive atherosclerosis (MINOCA) in an age- and race-adjusted analysis. All of these were statistically significant differences.

Of note, however, in a multivariate analysis fully adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, as well as hypercoagulability, preterm birth, grand multiparity, and insurance status, placental abruption was independently associated with a 2.14-fold risk of MINOCA, but it was no longer linked to significantly increased risks of the other cardiovascular events.

The implication is that the increased risk of these other forms of cardiovascular disease is mediated through the women’s increased prevalence of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, whereas a novel mechanism – most likely microvascular dysfunction – underlies the association between placental abruption and MINOCA, according to Dr. Healy.

He plans to extend this research by taking a look at the relationship between placental abruption and the various subtypes of MINOCA, including coronary dissection, vasospasm, thrombophilia disorders, and stress cardiomyopathy, in order to examine whether the increased risk posed by placental abruption is concentrated in certain forms of MINOCA. Data on MINOCA subtypes were recorded as part of the California project.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Women who experience placental abruption are at significantly increased risk for multiple forms of cardiovascular disease beginning within the first few years after their pregnancy complication, according to a study of more than 1.6 million California women.

While gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction have previously all been shown to be associated with increased risk of incident cardiovascular disease, this huge California study provides the first strong epidemiologic evidence that placental abruption is as well. Prior studies looking at the issue have been underpowered, Michael J. Healey, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our hypothesis is that there might be some type of shared mechanism, probably involving microvascular dysfunction, that explains the relationships we see between these pregnancy complications and increased near-term risk of cardiovascular disease,” he explained in an interview.

Dr. Healy, a hospitalist attached to the heart failure service at the University of California, San Francisco, presented a retrospective study of a multiethnic cohort comprising 1,614,950 parous women aged 15-50 years who participated in the California Healthcare Cost and Utility Project during 2005-2009. Placental abruption occurred in 15,057 of them at a mean age of 29.2 years.

During a median 4.9 years of follow-up, women who experienced abruptio placenta were at 6% increased risk for heart failure, 11% greater risk for MI, 8% increased risk for hypertensive urgency, and 2% greater risk for myocardial infarction with no obstructive atherosclerosis (MINOCA) in an age- and race-adjusted analysis. All of these were statistically significant differences.

Of note, however, in a multivariate analysis fully adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, as well as hypercoagulability, preterm birth, grand multiparity, and insurance status, placental abruption was independently associated with a 2.14-fold risk of MINOCA, but it was no longer linked to significantly increased risks of the other cardiovascular events.

The implication is that the increased risk of these other forms of cardiovascular disease is mediated through the women’s increased prevalence of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, whereas a novel mechanism – most likely microvascular dysfunction – underlies the association between placental abruption and MINOCA, according to Dr. Healy.

He plans to extend this research by taking a look at the relationship between placental abruption and the various subtypes of MINOCA, including coronary dissection, vasospasm, thrombophilia disorders, and stress cardiomyopathy, in order to examine whether the increased risk posed by placental abruption is concentrated in certain forms of MINOCA. Data on MINOCA subtypes were recorded as part of the California project.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Placental abruption is associated with increased risk of maternal cardiovascular events within a few years after delivery.

Major finding: Placental abruption was independently associated with a 2.14-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction with no obstructive atherosclerosis during a median 4.9 years of follow-up.

Study details: This was a retrospective study of more than 1.6 million parous women enrolled in the California Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, including 15,057 with placental abruption.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Product Update: Vistara; Ultravision trocar; CompuFlo Epidural; and Philips ultrasound

PRENATAL SCREENING FOR SINGLE-GENE DISORDERS

Vistara®, a non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT) from Natera, Inc, screens for single-gene disorders after 9 weeks’ gestation. Complementing the Panorama® NIPT, Vistara tests for major anatomic abnormalities and chromosome imbalances that have a combined incidence rate of 1 in 600 (higher than Down syndrome). These mutations can cause severe conditions affecting skeletal, cardiac, and neurologic systems, such as Noonan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, craniosynostosis syndromes, achondroplasia, and Rett syndrome. Standard NIPT commonly cannot detect these de novo (not inherited) mutations. Ultrasound exams may either completely miss the disorders or identify nonspecific findings later in pregnancy.

Natera says that Vistara has a combined analytical sensitivity of >99% and a combined analytical specificity of >99% in validation studies.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.natera.com/vistara

ELECTROSTATIC SURGICAL SMOKE REMOVAL

The UltravisionTM Trocar device from Alesi Surgical Technologies uses a low-energy electrostatic charge to eliminate the surgical smoke generated by cutting instruments during laparoscopic surgery. Electrostatic precipitation accelerates the natural process of sedimentation; Ultravision creates negatively charged gas ions that draw water vapor and particulate matter away from the surgical site toward “positive” patient tissue.

Alesi says that bench studies comparing Ultravision with a vacuum-system when using monopolar, bipolar, and ultrasonic instruments show that its device is faster and more efficient than smoke evacuation. When switched on before cutting, Ultravision precipitates 99% of particles within 30 seconds. After 1 minute of continuous use, Ultravision precipitates 99.9% of particles, independent of particle size, from 7 nm to 10 µm. Smoke evacuation removes 30.2% of particles after 1 minute, according to Alesi.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.alesi-surgical.com

PRESSURE-SENSING TECHNOLOGY FOR EPIDURALS

The CompuFlo®Epidural from Milestone Scientific uses pressure-sensing technology to identify the epidural space, and provides a computer-controlled drug delivery system.

Knowing the precise needle location during an epidural injection procedure provides a measure of safety not available to physicians who use conventional syringes. Milestone says that its CompuFlo Epidural allows anesthesiologists to use both hands to advance and direct the needle, and to confirm the epidural space with 99% accuracy on the first attempt.

CompuFlo Epidural differentiates tissue types for the medical professional via visual and audio feedback, leading to precise location guidance as the needle advances toward the intended area. It also allows for controlled needle exit pressure, precise flow rate and drug volumes, and patient treatment documentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.milestonescientific.com/products/compuflo-epidural

OBGYN ULTRASOUND INNOVATIONS

Philips recently announced enhancements to its EPIQ 7 and 5 and Affiniti 70 ultrasound systems. According to Philips, the eL18-4 transducer provides high-detail resolution and image uniformity with penetration for enhanced diagnostic quality in 1st- and 2nd-trimester obstetric exams. aBiometry AssistAI, with anatomical intelligence of fetal anatomy, streamlines fetal measurement by preplacing measurement cursors on selected structures. The new TouchVue control-panel interface on TrueVue allows practitioners to interact with finger gestures and to direct 3D-volume rotation and internal light-source position. The 2D Tilt feature offered on the 3D9-v3 transducer provides lateral scanning of anatomic structures that are off-axis without having to manually angle the transducer.

These new features complement the existing suite of Philips ObGyn ultrasound visualization tools: TrueVue, GlassVue, aRevealAI, and MaxVue.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.usa.philips.com/healthcare/resources/feature-detail/ultrasound-truevue-imaging

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

PRENATAL SCREENING FOR SINGLE-GENE DISORDERS

Vistara®, a non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT) from Natera, Inc, screens for single-gene disorders after 9 weeks’ gestation. Complementing the Panorama® NIPT, Vistara tests for major anatomic abnormalities and chromosome imbalances that have a combined incidence rate of 1 in 600 (higher than Down syndrome). These mutations can cause severe conditions affecting skeletal, cardiac, and neurologic systems, such as Noonan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, craniosynostosis syndromes, achondroplasia, and Rett syndrome. Standard NIPT commonly cannot detect these de novo (not inherited) mutations. Ultrasound exams may either completely miss the disorders or identify nonspecific findings later in pregnancy.

Natera says that Vistara has a combined analytical sensitivity of >99% and a combined analytical specificity of >99% in validation studies.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.natera.com/vistara

ELECTROSTATIC SURGICAL SMOKE REMOVAL

The UltravisionTM Trocar device from Alesi Surgical Technologies uses a low-energy electrostatic charge to eliminate the surgical smoke generated by cutting instruments during laparoscopic surgery. Electrostatic precipitation accelerates the natural process of sedimentation; Ultravision creates negatively charged gas ions that draw water vapor and particulate matter away from the surgical site toward “positive” patient tissue.

Alesi says that bench studies comparing Ultravision with a vacuum-system when using monopolar, bipolar, and ultrasonic instruments show that its device is faster and more efficient than smoke evacuation. When switched on before cutting, Ultravision precipitates 99% of particles within 30 seconds. After 1 minute of continuous use, Ultravision precipitates 99.9% of particles, independent of particle size, from 7 nm to 10 µm. Smoke evacuation removes 30.2% of particles after 1 minute, according to Alesi.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.alesi-surgical.com

PRESSURE-SENSING TECHNOLOGY FOR EPIDURALS

The CompuFlo®Epidural from Milestone Scientific uses pressure-sensing technology to identify the epidural space, and provides a computer-controlled drug delivery system.

Knowing the precise needle location during an epidural injection procedure provides a measure of safety not available to physicians who use conventional syringes. Milestone says that its CompuFlo Epidural allows anesthesiologists to use both hands to advance and direct the needle, and to confirm the epidural space with 99% accuracy on the first attempt.

CompuFlo Epidural differentiates tissue types for the medical professional via visual and audio feedback, leading to precise location guidance as the needle advances toward the intended area. It also allows for controlled needle exit pressure, precise flow rate and drug volumes, and patient treatment documentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.milestonescientific.com/products/compuflo-epidural

OBGYN ULTRASOUND INNOVATIONS

Philips recently announced enhancements to its EPIQ 7 and 5 and Affiniti 70 ultrasound systems. According to Philips, the eL18-4 transducer provides high-detail resolution and image uniformity with penetration for enhanced diagnostic quality in 1st- and 2nd-trimester obstetric exams. aBiometry AssistAI, with anatomical intelligence of fetal anatomy, streamlines fetal measurement by preplacing measurement cursors on selected structures. The new TouchVue control-panel interface on TrueVue allows practitioners to interact with finger gestures and to direct 3D-volume rotation and internal light-source position. The 2D Tilt feature offered on the 3D9-v3 transducer provides lateral scanning of anatomic structures that are off-axis without having to manually angle the transducer.

These new features complement the existing suite of Philips ObGyn ultrasound visualization tools: TrueVue, GlassVue, aRevealAI, and MaxVue.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.usa.philips.com/healthcare/resources/feature-detail/ultrasound-truevue-imaging

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

PRENATAL SCREENING FOR SINGLE-GENE DISORDERS

Vistara®, a non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT) from Natera, Inc, screens for single-gene disorders after 9 weeks’ gestation. Complementing the Panorama® NIPT, Vistara tests for major anatomic abnormalities and chromosome imbalances that have a combined incidence rate of 1 in 600 (higher than Down syndrome). These mutations can cause severe conditions affecting skeletal, cardiac, and neurologic systems, such as Noonan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, craniosynostosis syndromes, achondroplasia, and Rett syndrome. Standard NIPT commonly cannot detect these de novo (not inherited) mutations. Ultrasound exams may either completely miss the disorders or identify nonspecific findings later in pregnancy.

Natera says that Vistara has a combined analytical sensitivity of >99% and a combined analytical specificity of >99% in validation studies.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.natera.com/vistara

ELECTROSTATIC SURGICAL SMOKE REMOVAL

The UltravisionTM Trocar device from Alesi Surgical Technologies uses a low-energy electrostatic charge to eliminate the surgical smoke generated by cutting instruments during laparoscopic surgery. Electrostatic precipitation accelerates the natural process of sedimentation; Ultravision creates negatively charged gas ions that draw water vapor and particulate matter away from the surgical site toward “positive” patient tissue.

Alesi says that bench studies comparing Ultravision with a vacuum-system when using monopolar, bipolar, and ultrasonic instruments show that its device is faster and more efficient than smoke evacuation. When switched on before cutting, Ultravision precipitates 99% of particles within 30 seconds. After 1 minute of continuous use, Ultravision precipitates 99.9% of particles, independent of particle size, from 7 nm to 10 µm. Smoke evacuation removes 30.2% of particles after 1 minute, according to Alesi.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.alesi-surgical.com

PRESSURE-SENSING TECHNOLOGY FOR EPIDURALS

The CompuFlo®Epidural from Milestone Scientific uses pressure-sensing technology to identify the epidural space, and provides a computer-controlled drug delivery system.

Knowing the precise needle location during an epidural injection procedure provides a measure of safety not available to physicians who use conventional syringes. Milestone says that its CompuFlo Epidural allows anesthesiologists to use both hands to advance and direct the needle, and to confirm the epidural space with 99% accuracy on the first attempt.

CompuFlo Epidural differentiates tissue types for the medical professional via visual and audio feedback, leading to precise location guidance as the needle advances toward the intended area. It also allows for controlled needle exit pressure, precise flow rate and drug volumes, and patient treatment documentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.milestonescientific.com/products/compuflo-epidural

OBGYN ULTRASOUND INNOVATIONS

Philips recently announced enhancements to its EPIQ 7 and 5 and Affiniti 70 ultrasound systems. According to Philips, the eL18-4 transducer provides high-detail resolution and image uniformity with penetration for enhanced diagnostic quality in 1st- and 2nd-trimester obstetric exams. aBiometry AssistAI, with anatomical intelligence of fetal anatomy, streamlines fetal measurement by preplacing measurement cursors on selected structures. The new TouchVue control-panel interface on TrueVue allows practitioners to interact with finger gestures and to direct 3D-volume rotation and internal light-source position. The 2D Tilt feature offered on the 3D9-v3 transducer provides lateral scanning of anatomic structures that are off-axis without having to manually angle the transducer.

These new features complement the existing suite of Philips ObGyn ultrasound visualization tools: TrueVue, GlassVue, aRevealAI, and MaxVue.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.usa.philips.com/healthcare/resources/feature-detail/ultrasound-truevue-imaging

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

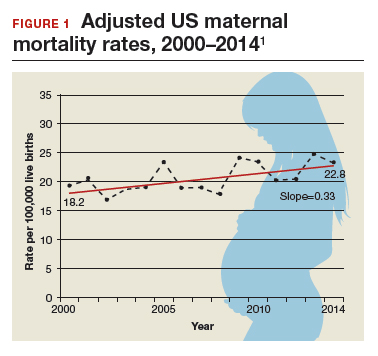

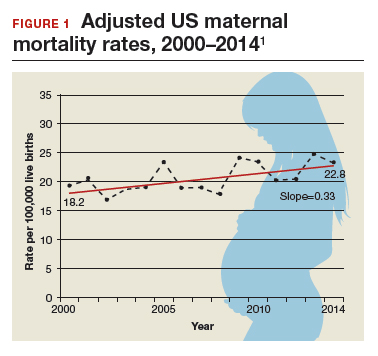

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

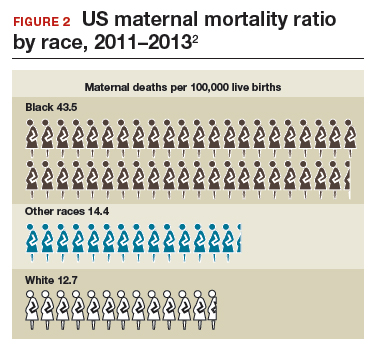

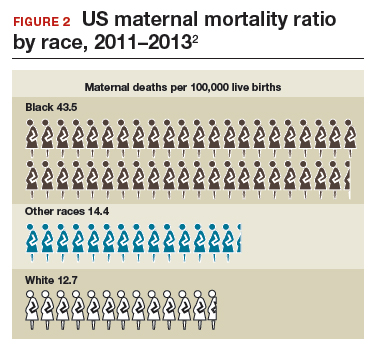

Considerable variations by race and by state

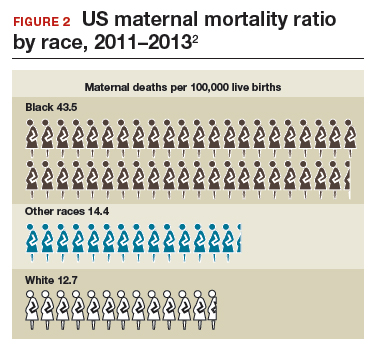

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

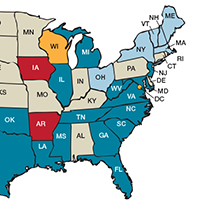

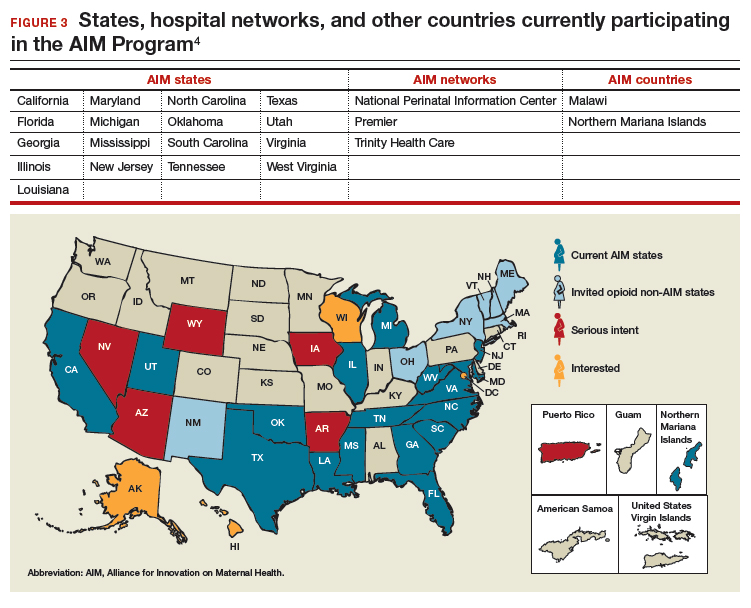

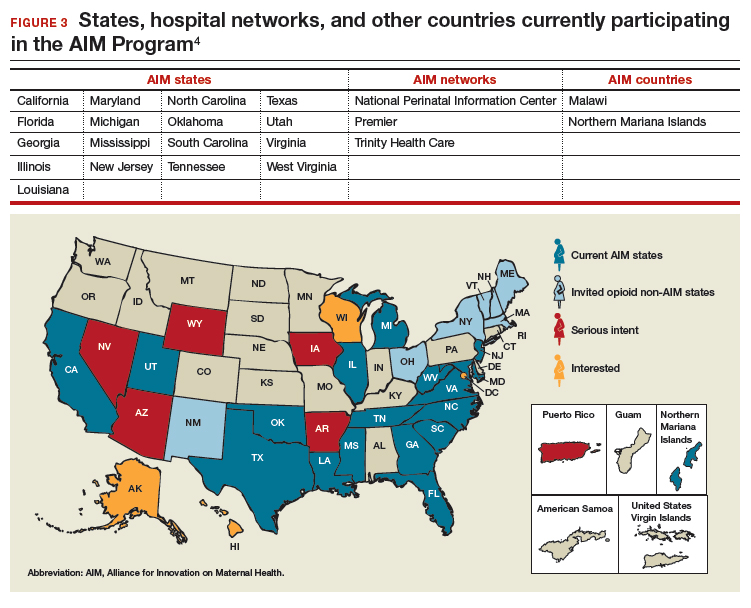

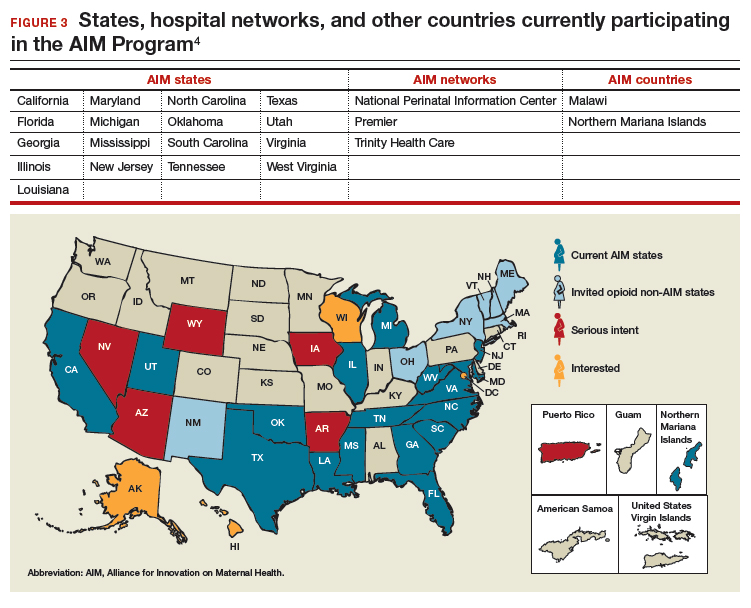

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.