User login

All isn’t well with HIV-exposed uninfected infants

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

AT ESPID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of hospitalization for a serious infectious illness during the first 12 months of life was 21% in HIV-exposed uninfected children, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies.

Data source: This prospective observational study included 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds and their offspring, followed to date through the infants’ first birthday.

Disclosures: Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Intra-amniotic sludge: Does its presence rule out cerclage for short cervix?

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

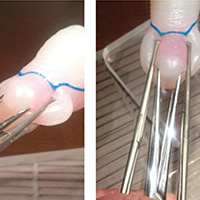

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

OSA in pregnancy linked to congenital anomalies

BOSTON – Newborns exposed to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in utero are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with congenital anomalies, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The researchers’ analysis covered data from more than 1.4 million births during 2010-2014. Circulatory, musculoskeletal, and central nervous systems were among the types of anomalies they saw in the 17.3% of babies born to mothers who had OSA during pregnancy. These babies were also more likely to require intensive care at birth, compared with those born to mothers who had not been diagnosed with OSA.

Additionally, the investigators found that the 0.1% of women who had a diagnosis of OSA were 2.76 times more likely to have babies that required some kind of resuscitative effort at birth. Specifically, 0.5% of the newborns of the mothers with OSA required resuscitation, compared with 0.1% of the other group’s babies. The newborns of women with OSA were also 2.25 times more likely to have a longer hospital stay.

Mothers with OSA were older and more likely to be non-Hispanic black and have a diagnosis of obesity, tobacco use, and drug use but not alcohol use.

“We can’t say for sure that sleep apnea is causing these outcomes,” said abstract presenter and principal investigator Ghada Bourjeily, MD, of Brown University and Miriam Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., in an interview.

“We know that women who have sleep apnea also often have other morbidities, so we don’t know what might have contributed to the congenital outcomes,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “We also don’t know if treating sleep apnea can reverse or prevent birth complications or even maternal complications, like preeclampsia or gestational diabetes.”

Ongoing studies are looking at maternal continuous positive airway pressure therapy use and neonatal outcomes, but “they are nothing to write home about yet,” she said.

“This is an underdiagnosed condition and it’s probably undercoded too, but we know from another study that the prevalence of OSA in the first trimester in an all-comers population that was screened for the condition is 4%,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “If another 3% of [the study participants] actually had OSA, then all of these findings are potentially underestimated.”

The majority of OSA in pregnant women that has been identified in prospective studies is mild and not necessarily something that most physicians would treat, she noted. “In our study, the ones who were diagnosed were those who probably went to their doctors and complained of sleepiness or loud snoring.”

The researchers also determined that the newborns of mothers with sleep apnea were more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (25.3% vs. 8.1%) or a special care nursery (34.9% vs. 13.6%).

A diagnosis of OSA was established when a diagnosis code for OSA was present on the delivery discharge record. Maternal and infant outcomes were collected for ICD-9 and procedural codes.

Dr. Bourjeily received research equipment support from Respironics.

BOSTON – Newborns exposed to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in utero are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with congenital anomalies, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The researchers’ analysis covered data from more than 1.4 million births during 2010-2014. Circulatory, musculoskeletal, and central nervous systems were among the types of anomalies they saw in the 17.3% of babies born to mothers who had OSA during pregnancy. These babies were also more likely to require intensive care at birth, compared with those born to mothers who had not been diagnosed with OSA.

Additionally, the investigators found that the 0.1% of women who had a diagnosis of OSA were 2.76 times more likely to have babies that required some kind of resuscitative effort at birth. Specifically, 0.5% of the newborns of the mothers with OSA required resuscitation, compared with 0.1% of the other group’s babies. The newborns of women with OSA were also 2.25 times more likely to have a longer hospital stay.

Mothers with OSA were older and more likely to be non-Hispanic black and have a diagnosis of obesity, tobacco use, and drug use but not alcohol use.

“We can’t say for sure that sleep apnea is causing these outcomes,” said abstract presenter and principal investigator Ghada Bourjeily, MD, of Brown University and Miriam Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., in an interview.

“We know that women who have sleep apnea also often have other morbidities, so we don’t know what might have contributed to the congenital outcomes,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “We also don’t know if treating sleep apnea can reverse or prevent birth complications or even maternal complications, like preeclampsia or gestational diabetes.”

Ongoing studies are looking at maternal continuous positive airway pressure therapy use and neonatal outcomes, but “they are nothing to write home about yet,” she said.

“This is an underdiagnosed condition and it’s probably undercoded too, but we know from another study that the prevalence of OSA in the first trimester in an all-comers population that was screened for the condition is 4%,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “If another 3% of [the study participants] actually had OSA, then all of these findings are potentially underestimated.”

The majority of OSA in pregnant women that has been identified in prospective studies is mild and not necessarily something that most physicians would treat, she noted. “In our study, the ones who were diagnosed were those who probably went to their doctors and complained of sleepiness or loud snoring.”

The researchers also determined that the newborns of mothers with sleep apnea were more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (25.3% vs. 8.1%) or a special care nursery (34.9% vs. 13.6%).

A diagnosis of OSA was established when a diagnosis code for OSA was present on the delivery discharge record. Maternal and infant outcomes were collected for ICD-9 and procedural codes.

Dr. Bourjeily received research equipment support from Respironics.

BOSTON – Newborns exposed to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in utero are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with congenital anomalies, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The researchers’ analysis covered data from more than 1.4 million births during 2010-2014. Circulatory, musculoskeletal, and central nervous systems were among the types of anomalies they saw in the 17.3% of babies born to mothers who had OSA during pregnancy. These babies were also more likely to require intensive care at birth, compared with those born to mothers who had not been diagnosed with OSA.

Additionally, the investigators found that the 0.1% of women who had a diagnosis of OSA were 2.76 times more likely to have babies that required some kind of resuscitative effort at birth. Specifically, 0.5% of the newborns of the mothers with OSA required resuscitation, compared with 0.1% of the other group’s babies. The newborns of women with OSA were also 2.25 times more likely to have a longer hospital stay.

Mothers with OSA were older and more likely to be non-Hispanic black and have a diagnosis of obesity, tobacco use, and drug use but not alcohol use.

“We can’t say for sure that sleep apnea is causing these outcomes,” said abstract presenter and principal investigator Ghada Bourjeily, MD, of Brown University and Miriam Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., in an interview.

“We know that women who have sleep apnea also often have other morbidities, so we don’t know what might have contributed to the congenital outcomes,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “We also don’t know if treating sleep apnea can reverse or prevent birth complications or even maternal complications, like preeclampsia or gestational diabetes.”

Ongoing studies are looking at maternal continuous positive airway pressure therapy use and neonatal outcomes, but “they are nothing to write home about yet,” she said.

“This is an underdiagnosed condition and it’s probably undercoded too, but we know from another study that the prevalence of OSA in the first trimester in an all-comers population that was screened for the condition is 4%,” said Dr. Bourjeily. “If another 3% of [the study participants] actually had OSA, then all of these findings are potentially underestimated.”

The majority of OSA in pregnant women that has been identified in prospective studies is mild and not necessarily something that most physicians would treat, she noted. “In our study, the ones who were diagnosed were those who probably went to their doctors and complained of sleepiness or loud snoring.”

The researchers also determined that the newborns of mothers with sleep apnea were more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (25.3% vs. 8.1%) or a special care nursery (34.9% vs. 13.6%).

A diagnosis of OSA was established when a diagnosis code for OSA was present on the delivery discharge record. Maternal and infant outcomes were collected for ICD-9 and procedural codes.

Dr. Bourjeily received research equipment support from Respironics.

AT SLEEP 2017

Key clinical point: This large cohort study is the first study to show an increased risk of congenital anomalies and resuscitation at birth in newborns born to mothers with diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Major finding: Of babies born to a mother with OSA, 17.3% had a congenital anomaly, compared with 10.6% of those born to mothers without OSA (P less than .001). This difference remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders.

Data source: A national cohort study including more than 1.4 million linked maternal and newborn records with a delivery hospitalization during 2010-2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Bourjeily received research equipment support from Respironics.

Study sheds light on pregnancy outcomes following ocrelizumab treatment

NEW ORLEANS – Data from the ocrelizumab clinical development program gives clinicians a first look at pregnancy outcomes after exposure to the drug, but the small size limits the ability to draw firm conclusions.

In the United States, prescribing information for ocrelizumab states that women of childbearing potential should use contraception while receiving ocrelizumab and for 6 months after the last infusion. At the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, researchers led by Sibyl Wray, MD, set out to assess the pregnancy, fetal, neonatal and infant outcomes in patients who became pregnant during ocrelizumab trials in MS, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through Sept. 15, 2015.

The analysis included ocrelizumab-exposed women in primarily European-based clinical trials in patients with MS, RA, or SLE, in whom doses ranged from 20 mg to 2,000 mg. These included three randomized trials of its use in MS, totaling 1,876 patients with a mean age of 40 years; four trials of its use in RA, totaling 2,759 patients with a mean age of 53 years; and one trial of its use in SLE, totaling 381 patients with a mean age of 31 years. Between 2008 and Sept. 14, 2015, a total of 48 women who were enrolled in the trials reported pregnancies.

MS data

Of the 15 pregnancies in the MS trials, three involved the delivery of full term, healthy newborns. In one case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 28 months before conception. In the second case, an infusion was given 20 weeks before conception, and a further infusion was given 17 days after conception. In the third case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 26.5 weeks before conception.

One live term birth occurred with an abnormal finding. In this case, the last infusion of ocrelizumab was 23 weeks prior to the last menstrual period or about 6 months prior to conception. The embryo/fetus was not exposed to the drug in utero. The researchers also found that seven elective terminations occurred among MS patients and that four pregnancies were ongoing at the time of this report.

“We have to be cautious because we don’t have enough data yet to know, but it’s encouraging to see that, if you follow the guidelines, the patient population and the newborns seem to be healthy in these exposed individuals,” Dr. Wray said.

RA data

Data from the RA clinical trials revealed 22 pregnancies in 21 patients exposed to ocrelizumab. Of these, eight pregnancies resulted in healthy term babies; four resulted in live births with abnormal findings (structural malformation, growth abnormality) or preterm birth; and eight pregnancies in seven women resulted in spontaneous abortion (one patient experienced a spontaneous abortion on two occasions), missed abortion, or an embryonic pregnancy. One pregnancy was lost to follow-up and another resulted in elective termination.

SLE data

During the SLE trials, 11 pregnancies occurred in 10 patients. Three pregnancies in two women resulted in healthy term babies. Three other pregnancies resulted in live births with an abnormal finding (structural malformation, functional deficit, growth abnormality) and/or preterm birth. Two pregnancies resulted in spontaneous/missed abortion. One pregnancy resulted in fetal death at 7.5 months’ gestation secondary to fatal pulmonary embolism in the mother; one pregnancy resulted in elective termination; and one pregnancy resulted in a healthy baby born at an unknown gestational week.

Dr. Wray emphasized that the small numbers of patients studied make it difficult to draw conclusions about pregnancy outcomes following ocrelizumab in patients with MS and other autoimmune diseases. “We need to pay attention to the half-life of this drug, the time it takes to clear, and how to plan pregnancies around that,” she said. She noted that pregnancy outcomes in ongoing ocrelizumab studies and postmarketing experiences will continue to be collected and assessed.

The study was funded by Roche, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Wray reported that she has received honoraria and/or research funding from Actelion, Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics.

NEW ORLEANS – Data from the ocrelizumab clinical development program gives clinicians a first look at pregnancy outcomes after exposure to the drug, but the small size limits the ability to draw firm conclusions.

In the United States, prescribing information for ocrelizumab states that women of childbearing potential should use contraception while receiving ocrelizumab and for 6 months after the last infusion. At the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, researchers led by Sibyl Wray, MD, set out to assess the pregnancy, fetal, neonatal and infant outcomes in patients who became pregnant during ocrelizumab trials in MS, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through Sept. 15, 2015.

The analysis included ocrelizumab-exposed women in primarily European-based clinical trials in patients with MS, RA, or SLE, in whom doses ranged from 20 mg to 2,000 mg. These included three randomized trials of its use in MS, totaling 1,876 patients with a mean age of 40 years; four trials of its use in RA, totaling 2,759 patients with a mean age of 53 years; and one trial of its use in SLE, totaling 381 patients with a mean age of 31 years. Between 2008 and Sept. 14, 2015, a total of 48 women who were enrolled in the trials reported pregnancies.

MS data

Of the 15 pregnancies in the MS trials, three involved the delivery of full term, healthy newborns. In one case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 28 months before conception. In the second case, an infusion was given 20 weeks before conception, and a further infusion was given 17 days after conception. In the third case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 26.5 weeks before conception.

One live term birth occurred with an abnormal finding. In this case, the last infusion of ocrelizumab was 23 weeks prior to the last menstrual period or about 6 months prior to conception. The embryo/fetus was not exposed to the drug in utero. The researchers also found that seven elective terminations occurred among MS patients and that four pregnancies were ongoing at the time of this report.

“We have to be cautious because we don’t have enough data yet to know, but it’s encouraging to see that, if you follow the guidelines, the patient population and the newborns seem to be healthy in these exposed individuals,” Dr. Wray said.

RA data

Data from the RA clinical trials revealed 22 pregnancies in 21 patients exposed to ocrelizumab. Of these, eight pregnancies resulted in healthy term babies; four resulted in live births with abnormal findings (structural malformation, growth abnormality) or preterm birth; and eight pregnancies in seven women resulted in spontaneous abortion (one patient experienced a spontaneous abortion on two occasions), missed abortion, or an embryonic pregnancy. One pregnancy was lost to follow-up and another resulted in elective termination.

SLE data

During the SLE trials, 11 pregnancies occurred in 10 patients. Three pregnancies in two women resulted in healthy term babies. Three other pregnancies resulted in live births with an abnormal finding (structural malformation, functional deficit, growth abnormality) and/or preterm birth. Two pregnancies resulted in spontaneous/missed abortion. One pregnancy resulted in fetal death at 7.5 months’ gestation secondary to fatal pulmonary embolism in the mother; one pregnancy resulted in elective termination; and one pregnancy resulted in a healthy baby born at an unknown gestational week.

Dr. Wray emphasized that the small numbers of patients studied make it difficult to draw conclusions about pregnancy outcomes following ocrelizumab in patients with MS and other autoimmune diseases. “We need to pay attention to the half-life of this drug, the time it takes to clear, and how to plan pregnancies around that,” she said. She noted that pregnancy outcomes in ongoing ocrelizumab studies and postmarketing experiences will continue to be collected and assessed.

The study was funded by Roche, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Wray reported that she has received honoraria and/or research funding from Actelion, Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics.

NEW ORLEANS – Data from the ocrelizumab clinical development program gives clinicians a first look at pregnancy outcomes after exposure to the drug, but the small size limits the ability to draw firm conclusions.

In the United States, prescribing information for ocrelizumab states that women of childbearing potential should use contraception while receiving ocrelizumab and for 6 months after the last infusion. At the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, researchers led by Sibyl Wray, MD, set out to assess the pregnancy, fetal, neonatal and infant outcomes in patients who became pregnant during ocrelizumab trials in MS, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through Sept. 15, 2015.

The analysis included ocrelizumab-exposed women in primarily European-based clinical trials in patients with MS, RA, or SLE, in whom doses ranged from 20 mg to 2,000 mg. These included three randomized trials of its use in MS, totaling 1,876 patients with a mean age of 40 years; four trials of its use in RA, totaling 2,759 patients with a mean age of 53 years; and one trial of its use in SLE, totaling 381 patients with a mean age of 31 years. Between 2008 and Sept. 14, 2015, a total of 48 women who were enrolled in the trials reported pregnancies.

MS data

Of the 15 pregnancies in the MS trials, three involved the delivery of full term, healthy newborns. In one case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 28 months before conception. In the second case, an infusion was given 20 weeks before conception, and a further infusion was given 17 days after conception. In the third case, the last ocrelizumab infusion was given 26.5 weeks before conception.

One live term birth occurred with an abnormal finding. In this case, the last infusion of ocrelizumab was 23 weeks prior to the last menstrual period or about 6 months prior to conception. The embryo/fetus was not exposed to the drug in utero. The researchers also found that seven elective terminations occurred among MS patients and that four pregnancies were ongoing at the time of this report.

“We have to be cautious because we don’t have enough data yet to know, but it’s encouraging to see that, if you follow the guidelines, the patient population and the newborns seem to be healthy in these exposed individuals,” Dr. Wray said.

RA data

Data from the RA clinical trials revealed 22 pregnancies in 21 patients exposed to ocrelizumab. Of these, eight pregnancies resulted in healthy term babies; four resulted in live births with abnormal findings (structural malformation, growth abnormality) or preterm birth; and eight pregnancies in seven women resulted in spontaneous abortion (one patient experienced a spontaneous abortion on two occasions), missed abortion, or an embryonic pregnancy. One pregnancy was lost to follow-up and another resulted in elective termination.

SLE data

During the SLE trials, 11 pregnancies occurred in 10 patients. Three pregnancies in two women resulted in healthy term babies. Three other pregnancies resulted in live births with an abnormal finding (structural malformation, functional deficit, growth abnormality) and/or preterm birth. Two pregnancies resulted in spontaneous/missed abortion. One pregnancy resulted in fetal death at 7.5 months’ gestation secondary to fatal pulmonary embolism in the mother; one pregnancy resulted in elective termination; and one pregnancy resulted in a healthy baby born at an unknown gestational week.

Dr. Wray emphasized that the small numbers of patients studied make it difficult to draw conclusions about pregnancy outcomes following ocrelizumab in patients with MS and other autoimmune diseases. “We need to pay attention to the half-life of this drug, the time it takes to clear, and how to plan pregnancies around that,” she said. She noted that pregnancy outcomes in ongoing ocrelizumab studies and postmarketing experiences will continue to be collected and assessed.

The study was funded by Roche, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Wray reported that she has received honoraria and/or research funding from Actelion, Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics.

AT THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 15 pregnancies in the MS trials, three involved the delivery of three full term, healthy newborns; one live term birth occurred with an abnormal finding; seven elective terminations occurred; and four pregnancies were ongoing.

Data source: A review of 48 pregnancies among women enrolled in clinical trials for ocrelizumab in MS, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Roche, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Wray reported that she has received honoraria and/or research funding from Actelion, Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, Novartis, and TG Therapeutics.

DMD use during pregnancy low, study finds

NEW ORLEANS – The proportion of women with multiple sclerosis with a live birth receiving disease-modifying drug therapy was low and declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods, results from a large analysis of national claims data found.

“Multiple sclerosis is up to three times more common in women than in men, and the clinical onset is often during childbearing years,” researchers led by Maria K. Houtchens, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “A better understanding of the ‘real world’ disease-modifying drug treatment patterns in women with MS and a pregnancy is essential in order to improve available clinical support, health care services, and quality of life for women with MS of childbearing age.”

Dr. Houtchens, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates reported results from 2,518 women who were included in the final analysis. Their mean age was 30 years, and 99% had commercial health insurance.

Overall, the proportion of women with MS and a live birth receiving DMD treatment was low, ranging from 1.9% to 25.5%, and the rate of treatment declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods.

During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a DMD decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and to 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased to 2.97% during the third trimester. At 9-12 months postpartum, the proportion of women treated with a DMD was 25.5%. Most patients were treated with self-injectable DMDs (from 1.7% to 19.6%), while the use of oral and infusion agents was low (0.1%-3.1% and 0%-0.2%, respectively).

The researchers also found that the proportion of women with DMD treatment before and after pregnancy increased significantly with the number of relapses experienced prepregnancy. A greater number of relapses before pregnancy led to more patients treated with DMDs.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on information from patients with health insurance administered by regional health plans. “Results may not be generalizable to patients who self-pay or patients without employer-sponsored commercial health insurance.”

The study was supported by EMD Serono. Dr. Houtchens reported that she has received funding support from EMD Serono and that she serves on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva Neuroscience. She also has received research support from Sanofi Genzyme.

NEW ORLEANS – The proportion of women with multiple sclerosis with a live birth receiving disease-modifying drug therapy was low and declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods, results from a large analysis of national claims data found.

“Multiple sclerosis is up to three times more common in women than in men, and the clinical onset is often during childbearing years,” researchers led by Maria K. Houtchens, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “A better understanding of the ‘real world’ disease-modifying drug treatment patterns in women with MS and a pregnancy is essential in order to improve available clinical support, health care services, and quality of life for women with MS of childbearing age.”

Dr. Houtchens, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates reported results from 2,518 women who were included in the final analysis. Their mean age was 30 years, and 99% had commercial health insurance.

Overall, the proportion of women with MS and a live birth receiving DMD treatment was low, ranging from 1.9% to 25.5%, and the rate of treatment declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods.

During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a DMD decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and to 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased to 2.97% during the third trimester. At 9-12 months postpartum, the proportion of women treated with a DMD was 25.5%. Most patients were treated with self-injectable DMDs (from 1.7% to 19.6%), while the use of oral and infusion agents was low (0.1%-3.1% and 0%-0.2%, respectively).

The researchers also found that the proportion of women with DMD treatment before and after pregnancy increased significantly with the number of relapses experienced prepregnancy. A greater number of relapses before pregnancy led to more patients treated with DMDs.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on information from patients with health insurance administered by regional health plans. “Results may not be generalizable to patients who self-pay or patients without employer-sponsored commercial health insurance.”

The study was supported by EMD Serono. Dr. Houtchens reported that she has received funding support from EMD Serono and that she serves on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva Neuroscience. She also has received research support from Sanofi Genzyme.

NEW ORLEANS – The proportion of women with multiple sclerosis with a live birth receiving disease-modifying drug therapy was low and declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods, results from a large analysis of national claims data found.

“Multiple sclerosis is up to three times more common in women than in men, and the clinical onset is often during childbearing years,” researchers led by Maria K. Houtchens, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “A better understanding of the ‘real world’ disease-modifying drug treatment patterns in women with MS and a pregnancy is essential in order to improve available clinical support, health care services, and quality of life for women with MS of childbearing age.”

Dr. Houtchens, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates reported results from 2,518 women who were included in the final analysis. Their mean age was 30 years, and 99% had commercial health insurance.

Overall, the proportion of women with MS and a live birth receiving DMD treatment was low, ranging from 1.9% to 25.5%, and the rate of treatment declined during the prepregnancy and pregnancy periods.

During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a DMD decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and to 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased to 2.97% during the third trimester. At 9-12 months postpartum, the proportion of women treated with a DMD was 25.5%. Most patients were treated with self-injectable DMDs (from 1.7% to 19.6%), while the use of oral and infusion agents was low (0.1%-3.1% and 0%-0.2%, respectively).

The researchers also found that the proportion of women with DMD treatment before and after pregnancy increased significantly with the number of relapses experienced prepregnancy. A greater number of relapses before pregnancy led to more patients treated with DMDs.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on information from patients with health insurance administered by regional health plans. “Results may not be generalizable to patients who self-pay or patients without employer-sponsored commercial health insurance.”

The study was supported by EMD Serono. Dr. Houtchens reported that she has received funding support from EMD Serono and that she serves on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva Neuroscience. She also has received research support from Sanofi Genzyme.

AT THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall, the proportion of women with multiple sclerosis and a live birth receiving DMD treatment was low, ranging from 1.9% to 25.5%.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of claims data from 2,518 women with MS.

Disclosures: The study was supported by EMD Serono. Dr. Houtchens reported that she has received funding support from EMD Serono and that she serves on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva Neuroscience. She also has received research support from Sanofi Genzyme.

Loud, frequent snoring increases preterm delivery risk

BOSTON – Women who were prepregnancy, frequent, and loud snorers during pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of preterm or early term delivery, in a study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

“The fact that there is an association between snoring and time to delivery in a cohort which is not hypertensive is alarming, and I think that treatment for snoring earlier on in pregnancy may alleviate some of these outcomes,” reported Galit Levi Dunietz, PhD, MPH, of the University of Michigan in a session at the meeting.

Compared with nonsnorers, frequently loud snorers had about a 60% increased risk of preterm delivery even after adjusting for baseline body mass index, smoking, education, race, and parity. Pregnancy-onset snoring and infrequent or quiet snoring were not associated with preterm birth.

A limitation on the findings was that only a small number of women (4% of the sample) fell into the chronic, frequent, and loud snoring category. These women, however, had significantly lower mean gestational age, mean baseline BMI, and were more likely to be smokers, as compared with nonsnorers and quiet frequent or infrequent snorers.

“I think this is excellent work because it’s a big question,” said Dr. Omavi Gbodossou Bailey, MD, MPH from the University of Arizona, Pheonix, in a Q&A session at the conference. “As a primary care physician, I deliver babies and I also deal with sleep and when I ask the ob.gyns. about sleep apnea in this patient population, they’re not usually interested.”

Dr. Bailey noted in an interview that, often, women who had uncomplicated first pregnancies return with later pregnancies heavier, more sleep deprived, and snoring. “Then, they have higher risk for complications in the second or third pregnancy,” he said.

Snoring is common in pregnancy, affecting about 35% of women, and pregnancy itself is a risk factor for snoring. Previous studies have associated snoring with key pregnancy morbidities including hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes, but, prior to this research, the few studies that had looked at snoring and preterm delivery had shown inconsistent results.

The researchers recruited 904 pregnant women in their third trimester and without hypertension or diabetes from prenatal clinics at the University of Michigan cared for between 2008 and 2011. The women were queried on the frequency of their snoring (from never to three or more times per week) along with its intensity (from nonsnoring to loud or very loud snoring). They were also categorized, based on self-report, as either chronic/prepregnancy snorers or incident/pregnancy-onset snorers.

In this low-risk cohort, 25% of the women reported incident snoring and 9% reported chronic prepregnancy snoring.

“The combination of snoring frequency and intensity may be a clinically useful marker to identify otherwise low-risk women who are likely to deliver earlier,” said Dr. Dunietz.

This study was funded by the Gilmore Fund for Sleep Research, the University of Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dunietz reported having no financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Women who were prepregnancy, frequent, and loud snorers during pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of preterm or early term delivery, in a study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

“The fact that there is an association between snoring and time to delivery in a cohort which is not hypertensive is alarming, and I think that treatment for snoring earlier on in pregnancy may alleviate some of these outcomes,” reported Galit Levi Dunietz, PhD, MPH, of the University of Michigan in a session at the meeting.

Compared with nonsnorers, frequently loud snorers had about a 60% increased risk of preterm delivery even after adjusting for baseline body mass index, smoking, education, race, and parity. Pregnancy-onset snoring and infrequent or quiet snoring were not associated with preterm birth.

A limitation on the findings was that only a small number of women (4% of the sample) fell into the chronic, frequent, and loud snoring category. These women, however, had significantly lower mean gestational age, mean baseline BMI, and were more likely to be smokers, as compared with nonsnorers and quiet frequent or infrequent snorers.

“I think this is excellent work because it’s a big question,” said Dr. Omavi Gbodossou Bailey, MD, MPH from the University of Arizona, Pheonix, in a Q&A session at the conference. “As a primary care physician, I deliver babies and I also deal with sleep and when I ask the ob.gyns. about sleep apnea in this patient population, they’re not usually interested.”

Dr. Bailey noted in an interview that, often, women who had uncomplicated first pregnancies return with later pregnancies heavier, more sleep deprived, and snoring. “Then, they have higher risk for complications in the second or third pregnancy,” he said.

Snoring is common in pregnancy, affecting about 35% of women, and pregnancy itself is a risk factor for snoring. Previous studies have associated snoring with key pregnancy morbidities including hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes, but, prior to this research, the few studies that had looked at snoring and preterm delivery had shown inconsistent results.

The researchers recruited 904 pregnant women in their third trimester and without hypertension or diabetes from prenatal clinics at the University of Michigan cared for between 2008 and 2011. The women were queried on the frequency of their snoring (from never to three or more times per week) along with its intensity (from nonsnoring to loud or very loud snoring). They were also categorized, based on self-report, as either chronic/prepregnancy snorers or incident/pregnancy-onset snorers.

In this low-risk cohort, 25% of the women reported incident snoring and 9% reported chronic prepregnancy snoring.

“The combination of snoring frequency and intensity may be a clinically useful marker to identify otherwise low-risk women who are likely to deliver earlier,” said Dr. Dunietz.

This study was funded by the Gilmore Fund for Sleep Research, the University of Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dunietz reported having no financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Women who were prepregnancy, frequent, and loud snorers during pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of preterm or early term delivery, in a study presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.