User login

Consider neurodevelopmental impacts of hyperemesis gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) affects just 1%-2% of pregnant women, but it’s clinical consequences are significant, with excess vomiting and dehydration, hospitalization, and the need for intravenous fluids being common in that group. In extreme cases, repeated vomiting has led to tears in the esophagus and severe dehydration has caused acute renal failure. All of that leaves aside the obvious suffering and distress it causes for women with the condition.

While studies continue to support the long-held theory that mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting has a protective effect in pregnancy, that does not appear to be true for HG. Rather, the medical literature shows that HG is associated with small-for-gestational-age neonates, low birth weight, higher rates of preterm birth, and lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes.

I was one of the investigators on a study that prospectively followed more than 200 women with nausea and vomiting in pregnancy from 2006 to 2012. We found that children whose mothers were hospitalized for their symptoms – 22 in all – had significantly lower IQ scores at 3.5 years to 7 years, compared with children whose mothers were not hospitalized. Verbal IQ scores were 107.2 points vs. 112.7 (P = .04), performance IQ scores were 105.6 vs. 112.3 (P = .03), and full scale IQ was 108.7 vs. 114.2 (P = .05).

The study cohort included three groups: women treated with more than four tablets per day of doxylamine/pyridoxine (Diclegis); women treated with up to four tablets per day of the drug; and women who did not receive pharmacotherapy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000463229.81803.1a).

Hospitalized women in the study received antiemetics about a week later, experienced more severe symptoms, and were more likely to report depression. Overall, we found that duration of hospitalization, maternal depression, and maternal IQ all were significant predictors for these outcomes. However, daily antiemetic therapy was not associated with adverse outcomes.

Another study, published the same year, found that children exposed to HG had a more than three times increased risk for a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including attention disorders, speech and language delays, and sensory disorders. The changes were more prevalent when women experienced symptoms early in pregnancy – prior to 5 weeks of gestation (Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015 Jun;189:79-84).

The study compared neurodevelopmental outcomes for 312 children from 203 women with HG, with 169 children from 89 unaffected mothers. The findings are similar to those of our study, despite the differences in methodologies. Both studies found that the antiemetics were not associated with adverse outcomes, but the symptoms of HG appear to be the culprit.

While more research is needed to confirm these findings, it makes sense that the nutritional deficiencies created by excess vomiting and inability to eat are having an impact on the fetus.

It also raises an important question for the ob.gyn. about when to intervene in these women. Often, clinicians take a wait-and-see approach to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, but the developing research suggests that earlier intervention would lead to better outcomes for mother and baby. One guide to determining that preventive antiemetics are necessary is to consider whether your patient has had HG in a previous pregnancy or if her mother or sister has experienced HG.

Another consideration is treating the nutritional deficiency that develops in women whose HG symptoms persist. These women are not simply in need of fluids and electrolytes but are missing essential vitamins and proteins. This is an area where much more research is needed, but clinicians can take a proactive approach by providing team care that includes consultation with a dietitians or nutritionist.

Finally, we cannot forget that maternal depression also appears to be significant predictor of poor fetal outcomes, so providing appropriate psychiatric treatment is essential.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology and pediatrics at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. Dr. Koren was a principal investigator in the U.S. study that resulted in the approval of Diclegis, marketed by Duchesnay USA, and has served as a consultant to Duchesnay.

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) affects just 1%-2% of pregnant women, but it’s clinical consequences are significant, with excess vomiting and dehydration, hospitalization, and the need for intravenous fluids being common in that group. In extreme cases, repeated vomiting has led to tears in the esophagus and severe dehydration has caused acute renal failure. All of that leaves aside the obvious suffering and distress it causes for women with the condition.

While studies continue to support the long-held theory that mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting has a protective effect in pregnancy, that does not appear to be true for HG. Rather, the medical literature shows that HG is associated with small-for-gestational-age neonates, low birth weight, higher rates of preterm birth, and lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes.

I was one of the investigators on a study that prospectively followed more than 200 women with nausea and vomiting in pregnancy from 2006 to 2012. We found that children whose mothers were hospitalized for their symptoms – 22 in all – had significantly lower IQ scores at 3.5 years to 7 years, compared with children whose mothers were not hospitalized. Verbal IQ scores were 107.2 points vs. 112.7 (P = .04), performance IQ scores were 105.6 vs. 112.3 (P = .03), and full scale IQ was 108.7 vs. 114.2 (P = .05).

The study cohort included three groups: women treated with more than four tablets per day of doxylamine/pyridoxine (Diclegis); women treated with up to four tablets per day of the drug; and women who did not receive pharmacotherapy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000463229.81803.1a).

Hospitalized women in the study received antiemetics about a week later, experienced more severe symptoms, and were more likely to report depression. Overall, we found that duration of hospitalization, maternal depression, and maternal IQ all were significant predictors for these outcomes. However, daily antiemetic therapy was not associated with adverse outcomes.

Another study, published the same year, found that children exposed to HG had a more than three times increased risk for a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including attention disorders, speech and language delays, and sensory disorders. The changes were more prevalent when women experienced symptoms early in pregnancy – prior to 5 weeks of gestation (Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015 Jun;189:79-84).

The study compared neurodevelopmental outcomes for 312 children from 203 women with HG, with 169 children from 89 unaffected mothers. The findings are similar to those of our study, despite the differences in methodologies. Both studies found that the antiemetics were not associated with adverse outcomes, but the symptoms of HG appear to be the culprit.

While more research is needed to confirm these findings, it makes sense that the nutritional deficiencies created by excess vomiting and inability to eat are having an impact on the fetus.

It also raises an important question for the ob.gyn. about when to intervene in these women. Often, clinicians take a wait-and-see approach to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, but the developing research suggests that earlier intervention would lead to better outcomes for mother and baby. One guide to determining that preventive antiemetics are necessary is to consider whether your patient has had HG in a previous pregnancy or if her mother or sister has experienced HG.

Another consideration is treating the nutritional deficiency that develops in women whose HG symptoms persist. These women are not simply in need of fluids and electrolytes but are missing essential vitamins and proteins. This is an area where much more research is needed, but clinicians can take a proactive approach by providing team care that includes consultation with a dietitians or nutritionist.

Finally, we cannot forget that maternal depression also appears to be significant predictor of poor fetal outcomes, so providing appropriate psychiatric treatment is essential.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology and pediatrics at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. Dr. Koren was a principal investigator in the U.S. study that resulted in the approval of Diclegis, marketed by Duchesnay USA, and has served as a consultant to Duchesnay.

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) affects just 1%-2% of pregnant women, but it’s clinical consequences are significant, with excess vomiting and dehydration, hospitalization, and the need for intravenous fluids being common in that group. In extreme cases, repeated vomiting has led to tears in the esophagus and severe dehydration has caused acute renal failure. All of that leaves aside the obvious suffering and distress it causes for women with the condition.

While studies continue to support the long-held theory that mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting has a protective effect in pregnancy, that does not appear to be true for HG. Rather, the medical literature shows that HG is associated with small-for-gestational-age neonates, low birth weight, higher rates of preterm birth, and lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes.

I was one of the investigators on a study that prospectively followed more than 200 women with nausea and vomiting in pregnancy from 2006 to 2012. We found that children whose mothers were hospitalized for their symptoms – 22 in all – had significantly lower IQ scores at 3.5 years to 7 years, compared with children whose mothers were not hospitalized. Verbal IQ scores were 107.2 points vs. 112.7 (P = .04), performance IQ scores were 105.6 vs. 112.3 (P = .03), and full scale IQ was 108.7 vs. 114.2 (P = .05).

The study cohort included three groups: women treated with more than four tablets per day of doxylamine/pyridoxine (Diclegis); women treated with up to four tablets per day of the drug; and women who did not receive pharmacotherapy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000463229.81803.1a).

Hospitalized women in the study received antiemetics about a week later, experienced more severe symptoms, and were more likely to report depression. Overall, we found that duration of hospitalization, maternal depression, and maternal IQ all were significant predictors for these outcomes. However, daily antiemetic therapy was not associated with adverse outcomes.

Another study, published the same year, found that children exposed to HG had a more than three times increased risk for a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including attention disorders, speech and language delays, and sensory disorders. The changes were more prevalent when women experienced symptoms early in pregnancy – prior to 5 weeks of gestation (Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015 Jun;189:79-84).

The study compared neurodevelopmental outcomes for 312 children from 203 women with HG, with 169 children from 89 unaffected mothers. The findings are similar to those of our study, despite the differences in methodologies. Both studies found that the antiemetics were not associated with adverse outcomes, but the symptoms of HG appear to be the culprit.

While more research is needed to confirm these findings, it makes sense that the nutritional deficiencies created by excess vomiting and inability to eat are having an impact on the fetus.

It also raises an important question for the ob.gyn. about when to intervene in these women. Often, clinicians take a wait-and-see approach to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, but the developing research suggests that earlier intervention would lead to better outcomes for mother and baby. One guide to determining that preventive antiemetics are necessary is to consider whether your patient has had HG in a previous pregnancy or if her mother or sister has experienced HG.

Another consideration is treating the nutritional deficiency that develops in women whose HG symptoms persist. These women are not simply in need of fluids and electrolytes but are missing essential vitamins and proteins. This is an area where much more research is needed, but clinicians can take a proactive approach by providing team care that includes consultation with a dietitians or nutritionist.

Finally, we cannot forget that maternal depression also appears to be significant predictor of poor fetal outcomes, so providing appropriate psychiatric treatment is essential.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology and pediatrics at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. Dr. Koren was a principal investigator in the U.S. study that resulted in the approval of Diclegis, marketed by Duchesnay USA, and has served as a consultant to Duchesnay.

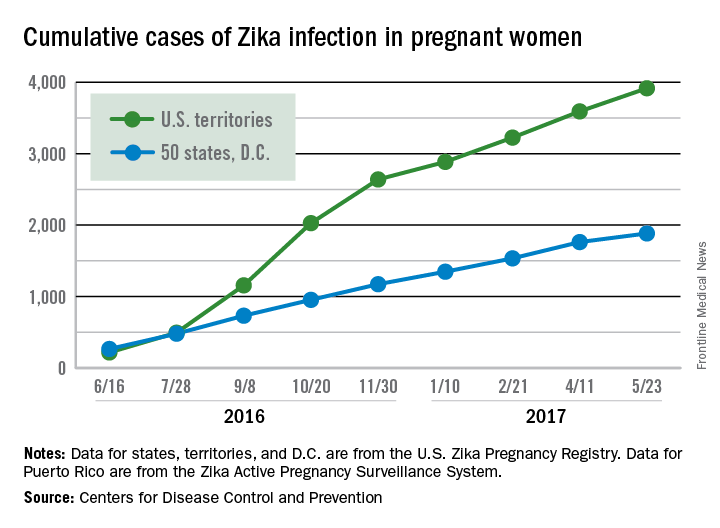

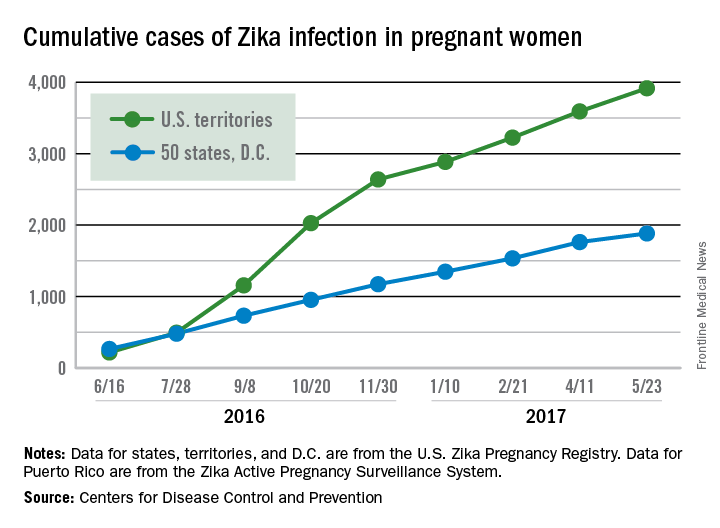

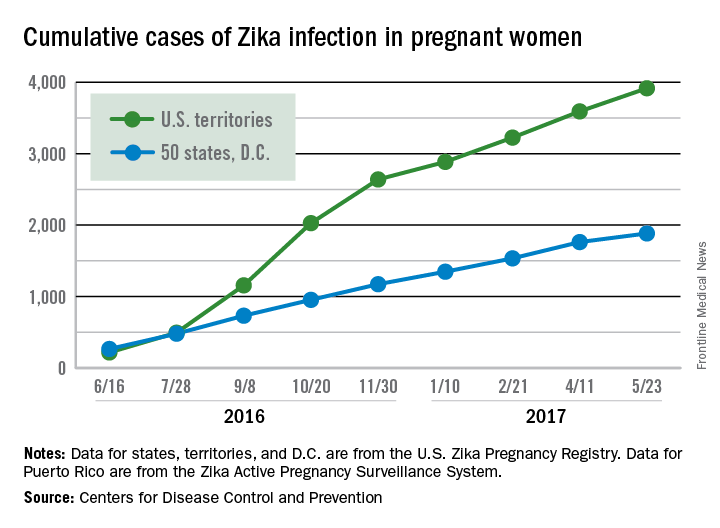

Zika-related birth defects up in recent weeks

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Cord gas analysis can be beneficial but has drawbacks

“HOW AND WHEN UMBILICAL CORD GAS ANALYSIS CAN JUSTIFY YOUR OBSTETRIC MANAGEMENT”

MICHAEL G. ROSS, MD, MPH (MARCH 2017)

Cord gas analysis can be beneficial but has drawbacks

In his article, Dr. Ross makes a few statements I would like to challenge. He gives a list of indications for cord gas analysis, even with a vigorous newborn. I would suggest that doing so is not only unnecessary, but could get the delivering provider in trouble. Normal gases with a vigorous infant are not actionable, and neither are abnormal gases with a vigorous infant. The latter situation could, however, lower the bar for a lawsuit if any neurologic pathology is diagnosed in the child.

At our hospital, blood gas assessments generate charges of $90 for each arterial and venous sample. The author states that gases are helpful for staff education. If that is the purposeof measuring the gases when Apgar scores are normal, then the bill for the gases should be sent to the staff, not the patient or insurance company.

The precise reason for doing cord gases is to prove you are a good doctor. If the Apgar scores are low, a healthy set of gases shows that your interventions were timely and appropriate. Normal gases prevent lawsuits in this situation.

Joe Walsh, MD

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Dr. Ross responds

I appreciate the comments of Dr. Walsh, who suggests that we should not obtain cord gases in vigorous infants due, in part, to the hospital charges. There are several reasons for the indications detailed in the article. Although normal Apgar scores would appear to negate the potential for severe metabolic acidosis, Apgar scoring accuracy has been challenged in medical legal cases. Furthermore, there may be newborn complications (eg, pre-existing hypoxic injury, intraventricular bleed) that may not be recognized immediately, yet hypoxemia and acidosis may be alleged to have contributed to the outcome. The actual cost of running a blood gas sample is far less than the $90 hospital charges. Nevertheless, if hospital charge is a concern, I recommend that the physician obtain a cord gas sample immediately following the delivery and determine whether to run the sample after the 5-minute Apgar score is obtained.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“HOW AND WHEN UMBILICAL CORD GAS ANALYSIS CAN JUSTIFY YOUR OBSTETRIC MANAGEMENT”

MICHAEL G. ROSS, MD, MPH (MARCH 2017)

Cord gas analysis can be beneficial but has drawbacks

In his article, Dr. Ross makes a few statements I would like to challenge. He gives a list of indications for cord gas analysis, even with a vigorous newborn. I would suggest that doing so is not only unnecessary, but could get the delivering provider in trouble. Normal gases with a vigorous infant are not actionable, and neither are abnormal gases with a vigorous infant. The latter situation could, however, lower the bar for a lawsuit if any neurologic pathology is diagnosed in the child.

At our hospital, blood gas assessments generate charges of $90 for each arterial and venous sample. The author states that gases are helpful for staff education. If that is the purposeof measuring the gases when Apgar scores are normal, then the bill for the gases should be sent to the staff, not the patient or insurance company.

The precise reason for doing cord gases is to prove you are a good doctor. If the Apgar scores are low, a healthy set of gases shows that your interventions were timely and appropriate. Normal gases prevent lawsuits in this situation.

Joe Walsh, MD

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Dr. Ross responds

I appreciate the comments of Dr. Walsh, who suggests that we should not obtain cord gases in vigorous infants due, in part, to the hospital charges. There are several reasons for the indications detailed in the article. Although normal Apgar scores would appear to negate the potential for severe metabolic acidosis, Apgar scoring accuracy has been challenged in medical legal cases. Furthermore, there may be newborn complications (eg, pre-existing hypoxic injury, intraventricular bleed) that may not be recognized immediately, yet hypoxemia and acidosis may be alleged to have contributed to the outcome. The actual cost of running a blood gas sample is far less than the $90 hospital charges. Nevertheless, if hospital charge is a concern, I recommend that the physician obtain a cord gas sample immediately following the delivery and determine whether to run the sample after the 5-minute Apgar score is obtained.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“HOW AND WHEN UMBILICAL CORD GAS ANALYSIS CAN JUSTIFY YOUR OBSTETRIC MANAGEMENT”

MICHAEL G. ROSS, MD, MPH (MARCH 2017)

Cord gas analysis can be beneficial but has drawbacks

In his article, Dr. Ross makes a few statements I would like to challenge. He gives a list of indications for cord gas analysis, even with a vigorous newborn. I would suggest that doing so is not only unnecessary, but could get the delivering provider in trouble. Normal gases with a vigorous infant are not actionable, and neither are abnormal gases with a vigorous infant. The latter situation could, however, lower the bar for a lawsuit if any neurologic pathology is diagnosed in the child.

At our hospital, blood gas assessments generate charges of $90 for each arterial and venous sample. The author states that gases are helpful for staff education. If that is the purposeof measuring the gases when Apgar scores are normal, then the bill for the gases should be sent to the staff, not the patient or insurance company.

The precise reason for doing cord gases is to prove you are a good doctor. If the Apgar scores are low, a healthy set of gases shows that your interventions were timely and appropriate. Normal gases prevent lawsuits in this situation.

Joe Walsh, MD

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Dr. Ross responds

I appreciate the comments of Dr. Walsh, who suggests that we should not obtain cord gases in vigorous infants due, in part, to the hospital charges. There are several reasons for the indications detailed in the article. Although normal Apgar scores would appear to negate the potential for severe metabolic acidosis, Apgar scoring accuracy has been challenged in medical legal cases. Furthermore, there may be newborn complications (eg, pre-existing hypoxic injury, intraventricular bleed) that may not be recognized immediately, yet hypoxemia and acidosis may be alleged to have contributed to the outcome. The actual cost of running a blood gas sample is far less than the $90 hospital charges. Nevertheless, if hospital charge is a concern, I recommend that the physician obtain a cord gas sample immediately following the delivery and determine whether to run the sample after the 5-minute Apgar score is obtained.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

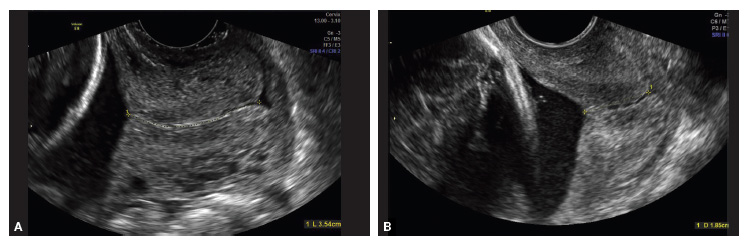

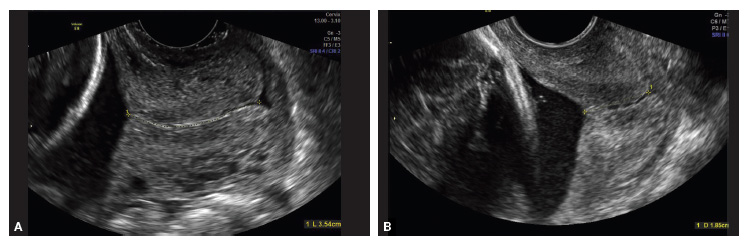

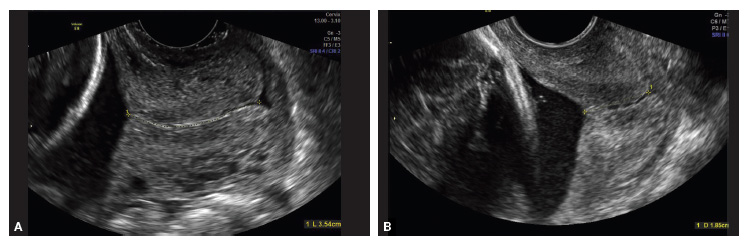

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

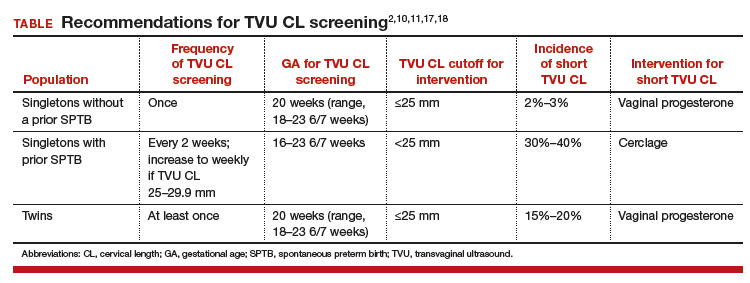

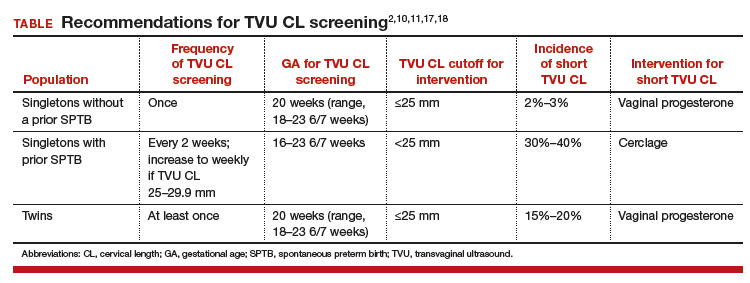

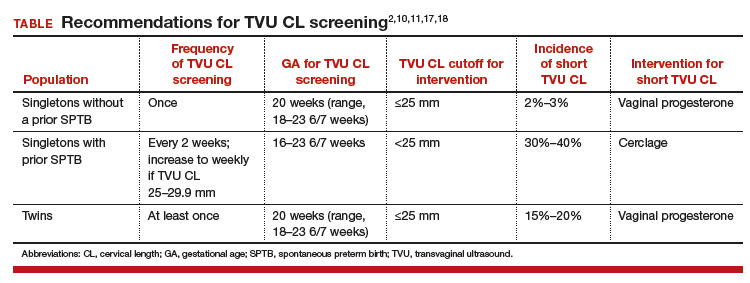

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

First trimester use of inactivated flu vaccine didn’t cause birth defects

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Infections up the risk for pregnancy-associated stroke in preeclampsia

A host of factors, some of them preventable or treatable, increase the risk of pregnancy-related stroke among women hospitalized for preeclampsia, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 800 preeclamptic women in New York.

Women who experienced a stroke were roughly seven times more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, and about three to four times more likely to have an infection, a prothrombotic state, a coagulopathy, or chronic hypertension, according to the findings (Stroke. 2017 May 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017374).

“Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and develop interventions aimed at preventing strokes in this uniquely vulnerable group,” they added.

For the study, the investigators used billing data from the 2003-2012 New York State Department of Health inpatient database to identify women aged 12-55 years admitted with preeclampsia.

They matched each woman who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke with three randomly selected controls of the same age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. They then compared the groups on a set of predefined risk factors.

Results showed that of 88,857 women admitted for preeclampsia during the study period, 0.2% experienced pregnancy-associated stroke, translating to a cumulative incidence of 222 per 100,000 preeclamptic women, a value more than six times that seen in the general pregnant population, the investigators noted.

The majority of strokes occurred post partum (66.5%), but more than a quarter occurred before delivery (27.9%). The single most common type of stroke was hemorrhagic (46.7%).

The 197 women with preeclampsia who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke had a sharply higher rate of in-hospital mortality (13.2%), compared with the 591 controls (0.2%).

In multivariate analysis, women with preeclampsia experiencing stroke were more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia (odds ratio, 7.2; 95% confidence interval, 4.6-11.3), or infections at the time of admission (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.6-5.8), predominantly genitourinary infections.

Other risk factors for pregnancy-associated stroke included prothrombotic states (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3-9.2), coagulopathies (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-7.1), or chronic hypertension (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.8-5.5).

The findings were similar when women were matched by the severity of preeclampsia, when women with eclampsia were excluded, or when women with only postpartum stroke were included.

Heart disease, multiple gestation, and previous pregnancies were not significantly independently associated with the risk of pregnancy-associated stroke.

“The ethnic and regional diversity of New York State increases the generalizability of our findings,” the investigators wrote. “Matching of cases and controls allowed for nuanced analysis of other risk factors.”

But the study may have missed some cases of preeclampsia not formally diagnosed, and the timing of infections relative to stroke was unknown, they acknowledged. Additionally, they noted that causality cannot be inferred from the observational study, and therefore the results should be interpreted cautiously.

The investigators reported research support from the National Institutes of Health. They had no other financial disclosures.

A host of factors, some of them preventable or treatable, increase the risk of pregnancy-related stroke among women hospitalized for preeclampsia, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 800 preeclamptic women in New York.

Women who experienced a stroke were roughly seven times more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, and about three to four times more likely to have an infection, a prothrombotic state, a coagulopathy, or chronic hypertension, according to the findings (Stroke. 2017 May 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017374).

“Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and develop interventions aimed at preventing strokes in this uniquely vulnerable group,” they added.

For the study, the investigators used billing data from the 2003-2012 New York State Department of Health inpatient database to identify women aged 12-55 years admitted with preeclampsia.

They matched each woman who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke with three randomly selected controls of the same age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. They then compared the groups on a set of predefined risk factors.

Results showed that of 88,857 women admitted for preeclampsia during the study period, 0.2% experienced pregnancy-associated stroke, translating to a cumulative incidence of 222 per 100,000 preeclamptic women, a value more than six times that seen in the general pregnant population, the investigators noted.

The majority of strokes occurred post partum (66.5%), but more than a quarter occurred before delivery (27.9%). The single most common type of stroke was hemorrhagic (46.7%).

The 197 women with preeclampsia who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke had a sharply higher rate of in-hospital mortality (13.2%), compared with the 591 controls (0.2%).

In multivariate analysis, women with preeclampsia experiencing stroke were more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia (odds ratio, 7.2; 95% confidence interval, 4.6-11.3), or infections at the time of admission (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.6-5.8), predominantly genitourinary infections.

Other risk factors for pregnancy-associated stroke included prothrombotic states (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3-9.2), coagulopathies (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-7.1), or chronic hypertension (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.8-5.5).

The findings were similar when women were matched by the severity of preeclampsia, when women with eclampsia were excluded, or when women with only postpartum stroke were included.

Heart disease, multiple gestation, and previous pregnancies were not significantly independently associated with the risk of pregnancy-associated stroke.

“The ethnic and regional diversity of New York State increases the generalizability of our findings,” the investigators wrote. “Matching of cases and controls allowed for nuanced analysis of other risk factors.”

But the study may have missed some cases of preeclampsia not formally diagnosed, and the timing of infections relative to stroke was unknown, they acknowledged. Additionally, they noted that causality cannot be inferred from the observational study, and therefore the results should be interpreted cautiously.

The investigators reported research support from the National Institutes of Health. They had no other financial disclosures.

A host of factors, some of them preventable or treatable, increase the risk of pregnancy-related stroke among women hospitalized for preeclampsia, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 800 preeclamptic women in New York.

Women who experienced a stroke were roughly seven times more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, and about three to four times more likely to have an infection, a prothrombotic state, a coagulopathy, or chronic hypertension, according to the findings (Stroke. 2017 May 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017374).

“Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and develop interventions aimed at preventing strokes in this uniquely vulnerable group,” they added.

For the study, the investigators used billing data from the 2003-2012 New York State Department of Health inpatient database to identify women aged 12-55 years admitted with preeclampsia.

They matched each woman who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke with three randomly selected controls of the same age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. They then compared the groups on a set of predefined risk factors.

Results showed that of 88,857 women admitted for preeclampsia during the study period, 0.2% experienced pregnancy-associated stroke, translating to a cumulative incidence of 222 per 100,000 preeclamptic women, a value more than six times that seen in the general pregnant population, the investigators noted.

The majority of strokes occurred post partum (66.5%), but more than a quarter occurred before delivery (27.9%). The single most common type of stroke was hemorrhagic (46.7%).

The 197 women with preeclampsia who experienced pregnancy-associated stroke had a sharply higher rate of in-hospital mortality (13.2%), compared with the 591 controls (0.2%).

In multivariate analysis, women with preeclampsia experiencing stroke were more likely to have severe preeclampsia or eclampsia (odds ratio, 7.2; 95% confidence interval, 4.6-11.3), or infections at the time of admission (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.6-5.8), predominantly genitourinary infections.

Other risk factors for pregnancy-associated stroke included prothrombotic states (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3-9.2), coagulopathies (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-7.1), or chronic hypertension (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.8-5.5).

The findings were similar when women were matched by the severity of preeclampsia, when women with eclampsia were excluded, or when women with only postpartum stroke were included.

Heart disease, multiple gestation, and previous pregnancies were not significantly independently associated with the risk of pregnancy-associated stroke.

“The ethnic and regional diversity of New York State increases the generalizability of our findings,” the investigators wrote. “Matching of cases and controls allowed for nuanced analysis of other risk factors.”

But the study may have missed some cases of preeclampsia not formally diagnosed, and the timing of infections relative to stroke was unknown, they acknowledged. Additionally, they noted that causality cannot be inferred from the observational study, and therefore the results should be interpreted cautiously.

The investigators reported research support from the National Institutes of Health. They had no other financial disclosures.

FROM STROKE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Independent risk factors for pregnancy-associated stroke were severe preeclampsia or eclampsia (OR, 7.2), infections (OR, 3.0), prothrombotic states (OR, 3.5), coagulopathies (OR, 3.1), or chronic hypertension (OR, 3.2).

Data source: A matched, case-control study of 788 women from a New York inpatient database who were hospitalized for preeclampsia.

Disclosures: The investigators reported research support from the National Institutes of Health. They had no other financial disclosures.

Inpatient prenatal yoga found feasible for high-risk women

AT ACOG 2017

SAN DIEGO – Inpatient prenatal yoga is a feasible and acceptable intervention for high-risk women admitted to the hospital, results from a single-center study suggested.

“We know that outside of obstetrics, yoga is beneficial to stress relief, musculoskeletal pain, and sleep quality,” Veronica Demtchouk, MD, said in an interview at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Inpatient high-risk obstetrics patients have very limited physical activity that they feel is safe to do.”

In an effort to investigate the feasibility of establishing an inpatient prenatal yoga program, the researchers recruited 40 women with anticipated admission to the antepartum service for at least 72 hours and who received medical clearance from their primary obstetrician. One of the medical center’s nurse practitioners, who is also a certified yoga instructor, taught a 30-minute prenatal yoga session once a week in a waiting room.

“It was a large enough space; we moved away the furniture and did the yoga sessions there,” Dr. Demtchouk said.

Study participants completed a questionnaire after each yoga session and at hospital discharge, while 14 nurses completed questionnaires regarding patient care and patient satisfaction. Of the 40 patients, 16 completed one or more yoga sessions; 24 did not participate because of scheduling conflicts with ultrasound or fetal testing, change in clinical status, lack of interest on the day of the session, and delivery or discharge prior to the yoga session.

Of the 16 study participants, 8 reported a decreased level of stress, 4 reported better sleep, 4 reported applying the yoga techniques outside of class, and 3 reported decreased pain/discomfort.

“Not a single woman complained or was displeased with the yoga sessions,” Dr. Demtchouk said. “The biggest challenge was the timing of the yoga session. It was just once a week, which limited the number of women who could attend.”

Of the 14 nurses who completed questionnaires, all viewed yoga as beneficial to their patients, none found it disruptive to providing patient care, and all indicated they would recommend an inpatient prenatal yoga program to other hospitals with an antepartum service.

“I think having several sessions throughout the week is essential for having adequate patient participation,” Dr. Demtchouk added. “It’s essential to have the nurses on board with it.”

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2017

SAN DIEGO – Inpatient prenatal yoga is a feasible and acceptable intervention for high-risk women admitted to the hospital, results from a single-center study suggested.

“We know that outside of obstetrics, yoga is beneficial to stress relief, musculoskeletal pain, and sleep quality,” Veronica Demtchouk, MD, said in an interview at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Inpatient high-risk obstetrics patients have very limited physical activity that they feel is safe to do.”

In an effort to investigate the feasibility of establishing an inpatient prenatal yoga program, the researchers recruited 40 women with anticipated admission to the antepartum service for at least 72 hours and who received medical clearance from their primary obstetrician. One of the medical center’s nurse practitioners, who is also a certified yoga instructor, taught a 30-minute prenatal yoga session once a week in a waiting room.

“It was a large enough space; we moved away the furniture and did the yoga sessions there,” Dr. Demtchouk said.

Study participants completed a questionnaire after each yoga session and at hospital discharge, while 14 nurses completed questionnaires regarding patient care and patient satisfaction. Of the 40 patients, 16 completed one or more yoga sessions; 24 did not participate because of scheduling conflicts with ultrasound or fetal testing, change in clinical status, lack of interest on the day of the session, and delivery or discharge prior to the yoga session.

Of the 16 study participants, 8 reported a decreased level of stress, 4 reported better sleep, 4 reported applying the yoga techniques outside of class, and 3 reported decreased pain/discomfort.