User login

USPSTF: Screen all adults for depression

All adults, including pregnant and postpartum women, should be screened for depression, according to new recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The recommendation also calls for screening to be coupled with “adequate systems” to ensure diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:380-7).

The depression screening recommendation, authored by Dr. Albert L. Siu and the other members of the USPSTF, is a level B recommendation, meaning that it has either high certainty of moderate net benefit, or moderate certainty of moderate to substantial net benefit.

The new guidance in screening for depression helps address a disorder that is “the leading cause of disability among adults in high-income countries,” said Dr. Siu and his coauthors. Lost productivity attributable to depression cost $23 billion in the United States in 2011, and $22.8 billion was spent on treatments for depression in 2009, the last year for which figures are available.

Dr. Siu, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his coauthors cited “convincing evidence that screening improves the accurate identification of adult patients with depression in primary care settings, including pregnant and postpartum women.”

In addition, the task force found convincing evidence that for older adults as well as the general adult population, treatment of “depression identified through screening in primary care settings with antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both decreases clinical morbidity.”

For pregnant and postpartum women with depression, Dr. Siu and his coauthors found “adequate” evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) improves outcomes.

The recommendation does not identify optimal timing and intervals for depression screening, citing a need for more research in this area. However, “a pragmatic approach might include screening all adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment in consideration of risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of high-risk patients is warranted,” explained Dr. Siu and his coauthors.

The new depression screening recommendation from USPSTF updates the 2009 recommendation, which recommended universal screening if “staff-assisted depression care supports” were in place, and targeted screening based on clinical judgment and patient preference if such support were unavailable.

The rationale for the current recommendation of universal screening for those 18 years and older is the “recognition that such support is now much more widely available and accepted as part of mental health care,” the task force members said.

Any potential harms of screening, said Dr. Siu and his coauthors, were minimal to nonexistent.

Overall, the USPSTF assigned a small to moderate risk to the use of medication in depression. However, the use of “second-generation” antidepressants – mostly SSRIs – was associated with some harms, including increased risk of suicidal behavior in young adults and of gastrointestinal bleeding in older adults, as well as potential fetal harms in pregnant women taking antidepressants.

Using CBT to treat depression in pregnant and postpartum women was also associated with minimal to no harm.

The USPSTF screening recommendation is aligned with the American Academy of Family Physicians’ recommendation to screen the general adult population for depression, and with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation that pediatricians screen mothers for depression at their babies’ 1-, 2-, and 4-month office visits.

Released in draft form in July 2015, the depression screening recommendation was available for public comment for a period of 4 weeks. In response to public input, the final recommendation’s implementation section clarifies and characterizes an “adequate system” of screening, and gives more resources for evidence-based depression screening and treatment.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality supports the operations of the USPSTF, but the task force’s recommendations are independent of the federal government. Dr. Siu and the other task force members reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

The new USPSTF recommendations carry a B grade, reflecting both the heterogeneous nature of the diagnosis of depression and the many areas of uncertainty in screening and treatment of the disorder. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a varied condition that may respond to a variety of treatments, including medication and various forms of therapy. The clinical spectrum of MDD may range from a mild, self-limited course to disabling depression that interferes with daily function and that may persist for long periods of time.

Even the nine-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), considered the first choice of many in primary care, only has a positive predictive value of about 50%, and will miss about one in five cases of true depression. This means that screening must be followed by clinically appropriate evaluation to assure accurate diagnosis of MDD.

|

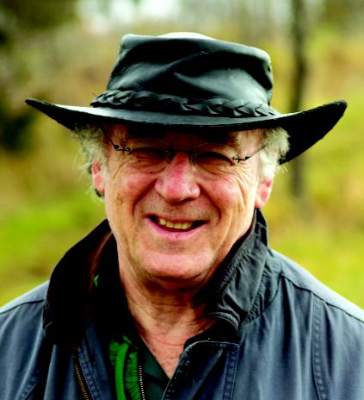

Dr. Michael E. Thase |

No biomarker has been identified that will predict which treatment will work for which patient with depression, and first-line antidepressants will only help about 50% of an intent-to-treat population.

Against that backdrop, clinicians should take patient preference into account, especially for patients with more severe depression, for whom preference may matter more. Individuals with more severe illness may require multiple adjustments to their pharmacologic and therapeutic regimen, so care systems should be built to anticipate this need.

Early warning systems that use technology to assess patient adherence and response may help effective tailoring of a therapeutic approach: Patients could complete online symptom diaries to assess early response to therapies, and a missed prescription refill – or failure to fill an initial prescription – could trigger prompt intervention by the care team.

Dr. Michael E. Thase is professor of psychiatry and chief of the mood and anxiety disorders treatment and research program at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The comments above were summarized from Dr. Thase’s editorial accompanying the USPSTF depression screening recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:349-50).

The new USPSTF recommendations carry a B grade, reflecting both the heterogeneous nature of the diagnosis of depression and the many areas of uncertainty in screening and treatment of the disorder. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a varied condition that may respond to a variety of treatments, including medication and various forms of therapy. The clinical spectrum of MDD may range from a mild, self-limited course to disabling depression that interferes with daily function and that may persist for long periods of time.

Even the nine-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), considered the first choice of many in primary care, only has a positive predictive value of about 50%, and will miss about one in five cases of true depression. This means that screening must be followed by clinically appropriate evaluation to assure accurate diagnosis of MDD.

|

Dr. Michael E. Thase |

No biomarker has been identified that will predict which treatment will work for which patient with depression, and first-line antidepressants will only help about 50% of an intent-to-treat population.

Against that backdrop, clinicians should take patient preference into account, especially for patients with more severe depression, for whom preference may matter more. Individuals with more severe illness may require multiple adjustments to their pharmacologic and therapeutic regimen, so care systems should be built to anticipate this need.

Early warning systems that use technology to assess patient adherence and response may help effective tailoring of a therapeutic approach: Patients could complete online symptom diaries to assess early response to therapies, and a missed prescription refill – or failure to fill an initial prescription – could trigger prompt intervention by the care team.

Dr. Michael E. Thase is professor of psychiatry and chief of the mood and anxiety disorders treatment and research program at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The comments above were summarized from Dr. Thase’s editorial accompanying the USPSTF depression screening recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:349-50).

The new USPSTF recommendations carry a B grade, reflecting both the heterogeneous nature of the diagnosis of depression and the many areas of uncertainty in screening and treatment of the disorder. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a varied condition that may respond to a variety of treatments, including medication and various forms of therapy. The clinical spectrum of MDD may range from a mild, self-limited course to disabling depression that interferes with daily function and that may persist for long periods of time.

Even the nine-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), considered the first choice of many in primary care, only has a positive predictive value of about 50%, and will miss about one in five cases of true depression. This means that screening must be followed by clinically appropriate evaluation to assure accurate diagnosis of MDD.

|

Dr. Michael E. Thase |

No biomarker has been identified that will predict which treatment will work for which patient with depression, and first-line antidepressants will only help about 50% of an intent-to-treat population.

Against that backdrop, clinicians should take patient preference into account, especially for patients with more severe depression, for whom preference may matter more. Individuals with more severe illness may require multiple adjustments to their pharmacologic and therapeutic regimen, so care systems should be built to anticipate this need.

Early warning systems that use technology to assess patient adherence and response may help effective tailoring of a therapeutic approach: Patients could complete online symptom diaries to assess early response to therapies, and a missed prescription refill – or failure to fill an initial prescription – could trigger prompt intervention by the care team.

Dr. Michael E. Thase is professor of psychiatry and chief of the mood and anxiety disorders treatment and research program at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The comments above were summarized from Dr. Thase’s editorial accompanying the USPSTF depression screening recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:349-50).

All adults, including pregnant and postpartum women, should be screened for depression, according to new recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The recommendation also calls for screening to be coupled with “adequate systems” to ensure diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:380-7).

The depression screening recommendation, authored by Dr. Albert L. Siu and the other members of the USPSTF, is a level B recommendation, meaning that it has either high certainty of moderate net benefit, or moderate certainty of moderate to substantial net benefit.

The new guidance in screening for depression helps address a disorder that is “the leading cause of disability among adults in high-income countries,” said Dr. Siu and his coauthors. Lost productivity attributable to depression cost $23 billion in the United States in 2011, and $22.8 billion was spent on treatments for depression in 2009, the last year for which figures are available.

Dr. Siu, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his coauthors cited “convincing evidence that screening improves the accurate identification of adult patients with depression in primary care settings, including pregnant and postpartum women.”

In addition, the task force found convincing evidence that for older adults as well as the general adult population, treatment of “depression identified through screening in primary care settings with antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both decreases clinical morbidity.”

For pregnant and postpartum women with depression, Dr. Siu and his coauthors found “adequate” evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) improves outcomes.

The recommendation does not identify optimal timing and intervals for depression screening, citing a need for more research in this area. However, “a pragmatic approach might include screening all adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment in consideration of risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of high-risk patients is warranted,” explained Dr. Siu and his coauthors.

The new depression screening recommendation from USPSTF updates the 2009 recommendation, which recommended universal screening if “staff-assisted depression care supports” were in place, and targeted screening based on clinical judgment and patient preference if such support were unavailable.

The rationale for the current recommendation of universal screening for those 18 years and older is the “recognition that such support is now much more widely available and accepted as part of mental health care,” the task force members said.

Any potential harms of screening, said Dr. Siu and his coauthors, were minimal to nonexistent.

Overall, the USPSTF assigned a small to moderate risk to the use of medication in depression. However, the use of “second-generation” antidepressants – mostly SSRIs – was associated with some harms, including increased risk of suicidal behavior in young adults and of gastrointestinal bleeding in older adults, as well as potential fetal harms in pregnant women taking antidepressants.

Using CBT to treat depression in pregnant and postpartum women was also associated with minimal to no harm.

The USPSTF screening recommendation is aligned with the American Academy of Family Physicians’ recommendation to screen the general adult population for depression, and with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation that pediatricians screen mothers for depression at their babies’ 1-, 2-, and 4-month office visits.

Released in draft form in July 2015, the depression screening recommendation was available for public comment for a period of 4 weeks. In response to public input, the final recommendation’s implementation section clarifies and characterizes an “adequate system” of screening, and gives more resources for evidence-based depression screening and treatment.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality supports the operations of the USPSTF, but the task force’s recommendations are independent of the federal government. Dr. Siu and the other task force members reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

All adults, including pregnant and postpartum women, should be screened for depression, according to new recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The recommendation also calls for screening to be coupled with “adequate systems” to ensure diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315[4]:380-7).

The depression screening recommendation, authored by Dr. Albert L. Siu and the other members of the USPSTF, is a level B recommendation, meaning that it has either high certainty of moderate net benefit, or moderate certainty of moderate to substantial net benefit.

The new guidance in screening for depression helps address a disorder that is “the leading cause of disability among adults in high-income countries,” said Dr. Siu and his coauthors. Lost productivity attributable to depression cost $23 billion in the United States in 2011, and $22.8 billion was spent on treatments for depression in 2009, the last year for which figures are available.

Dr. Siu, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his coauthors cited “convincing evidence that screening improves the accurate identification of adult patients with depression in primary care settings, including pregnant and postpartum women.”

In addition, the task force found convincing evidence that for older adults as well as the general adult population, treatment of “depression identified through screening in primary care settings with antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both decreases clinical morbidity.”

For pregnant and postpartum women with depression, Dr. Siu and his coauthors found “adequate” evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) improves outcomes.

The recommendation does not identify optimal timing and intervals for depression screening, citing a need for more research in this area. However, “a pragmatic approach might include screening all adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment in consideration of risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of high-risk patients is warranted,” explained Dr. Siu and his coauthors.

The new depression screening recommendation from USPSTF updates the 2009 recommendation, which recommended universal screening if “staff-assisted depression care supports” were in place, and targeted screening based on clinical judgment and patient preference if such support were unavailable.

The rationale for the current recommendation of universal screening for those 18 years and older is the “recognition that such support is now much more widely available and accepted as part of mental health care,” the task force members said.

Any potential harms of screening, said Dr. Siu and his coauthors, were minimal to nonexistent.

Overall, the USPSTF assigned a small to moderate risk to the use of medication in depression. However, the use of “second-generation” antidepressants – mostly SSRIs – was associated with some harms, including increased risk of suicidal behavior in young adults and of gastrointestinal bleeding in older adults, as well as potential fetal harms in pregnant women taking antidepressants.

Using CBT to treat depression in pregnant and postpartum women was also associated with minimal to no harm.

The USPSTF screening recommendation is aligned with the American Academy of Family Physicians’ recommendation to screen the general adult population for depression, and with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation that pediatricians screen mothers for depression at their babies’ 1-, 2-, and 4-month office visits.

Released in draft form in July 2015, the depression screening recommendation was available for public comment for a period of 4 weeks. In response to public input, the final recommendation’s implementation section clarifies and characterizes an “adequate system” of screening, and gives more resources for evidence-based depression screening and treatment.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality supports the operations of the USPSTF, but the task force’s recommendations are independent of the federal government. Dr. Siu and the other task force members reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Screen all adults for depression, including pregnant and postpartum women.

Major finding: All adults should be screened for depression, with adequate systems in place for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

Data source: New recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Disclosures: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality supports the operations of the USPSTF, but the task force’s recommendations are independent of the federal government. Dr. Siu and the other task force members reported no conflicts of interest.

Maternal immunization during pregnancy: lessons learned, and emerging opportunities

Pediatricians and our teams are the immunization experts. We educate, advocate, and incorporate vaccines into much of our daily routine. As such, we recognize the importance of working with our colleagues in family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics to optimize immunization programs for high-risk individuals, including pregnant women. Recent advances in vaccine recommendations during pregnancy are a result of the collaborative efforts of the health care providers for these women, and from systematic evaluation of immunization programs, vaccine pregnancy registries, and disease epidemiology.

Vaccinating women during pregnancy should be considered when a vaccine is known to be safe and when the following apply:

• The risk of severe infection is high during or augmented by pregnancy.

• The specific infection during pregnancy threatens the fetus.

• Maternal protection against infection benefits the newborn.

• Passive transfer of antibody from mother to fetus benefits the newborn.

Examples of safe vaccines immediately come to mind that fulfill one of more of these criteria, yet substantial obstacles exist even where safety and effectiveness data are robust. Because clinical vaccine trials traditionally exclude pregnant women, safety and effectiveness data for this group and their newborns are limited and often must come through experience. In a climate of increased vaccine hesitancy in general, both among providers and patients, vaccine delivery can be fragmented and particularly difficult to streamline. Additional obstacles that exist for any immunization program, including one that targets pregnant women specifically, are immunization delivery logistics and cost.

One of the major success stories of maternal immunization that is easily forgotten or overlooked in developed parts of the world is in the prevention of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT). A review of recent history reminds us that between the years 2000 and 2014, 35 countries were finally successful in eliminating MNT, including China, Turkey, Egypt, and South Africa. In addition, 24 of 36 states in the country of India, 30 of 34 provinces of Indonesia, and most of Ethiopia have met with success. This has been accomplished through aggressive tetanus vaccination programs, and through education programs targeted at optimal umbilical cord stump care after delivery.

In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all pregnant women should receive inactivated influenza vaccine and Tdap vaccine. In addition, several other vaccines are recommended under certain circumstances. Live attenuated vaccines are considered contraindicated, although yellow fever vaccine is an exception during epidemics, or when travel to a highly endemic area during pregnancy cannot be avoided.

Influenza vaccine administered during pregnancy reduces maternal morbidity and mortality. Moreover, safety and benefits for the fetus are clearly documented. Both retrospective cohort analysis studies and randomized controlled trials have consistently demonstrated lower risk of preterm birth and lower risk for delivering newborns small for gestational age among women who received inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy. The benefit extends to term healthy infants who are less likely to be hospitalized during the first months of life if their mother was vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy. Because the mother was immunized during pregnancy, it reduces her risk of infection, thereby reducing the potential that the newborn will be exposed to a mother who is contagious. Perhaps more importantly, infants born at or near term have the benefit of transplacental antibody endowment from their mother, including vaccine induced anti-influenza antibodies. This passive protection is expected to last for several months. Active immunization against influenza during infancy begins at 6 months of age.

Tdap vaccine is also recommended during each pregnancy. In the United States, MNT is eliminated. Here, as in other developed countries, Tdap is administered to reduce infant pertussis morbidity. Pertussis remains endemic to the United States, and infants who develop whooping cough during the first 2-3 months of life are at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality.

Historically, one-third of infants infected with pertussis were infected by their mother, although more recent evidence suggests that older siblings are at least as likely a source. Looking back to the paradigm for protection against influenza infection in the first few months of life, it becomes clear why the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended Tdap vaccine for all mothers during each pregnancy.

The first goal is to prevent pertussis in the mother so that she will not transmit the infection to her newborn. The additional goal, and the rationale for vaccinating pregnant women during every pregnancy, is to optimize levels of anti-pertussis antibody in the mother, so that the transplacental endowment to the infant is as robust as possible.

Serologic studies have demonstrated that Tdap vaccine induces high anti-pertussis antibodies when administered during pregnancy, but that the half-life of those antibodies is brief. When Tdap is given during pregnancy, and the infant is born at or near term, the antibody transfer to the infant is expected to provide passive protection for several months. Maternal immunization during pregnancy thereby reduces the risk that the mother will develop pertussis and transmit it to her newborn, while at the same time allows a degree of passive immunoprotection to the infant during the most vulnerable period of life. Active immunization against pertussis in the infant begins between 6-8 weeks of age.

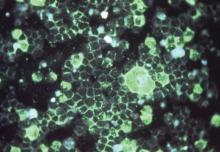

Another infection that is exceedingly common during the first several months of life is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV remains the most common reason for infant hospitalization in the United States and other developed countries. The source of the virus can be any other person with a mild or moderate respiratory tract infection as the virus is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime. The first infection, however, is the worst. It is estimated that between 3% and 4% of the U.S. birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV. With a U.S. birth cohort of about 4 million, the result is 120,000-160,000 infant admissions annually.

The RSV epidemic is seasonal, fairly predictable, and dreaded by primary care pediatricians and hospitalists alike. Lower respiratory tract infection with RSV, in the form of RSV bronchiolitis, presents all too commonly in the young infant with cough, coryza, tachypnea, and wheezing. When the work of breathing increases, and the cough symptoms predominate, the infant is unable to feed efficiently. Hospitalizations may be for dehydration, concerns for impending respiratory failure, or for the administration of supplemental oxygen or other respiratory support. No specific therapeutic interventions reliably reduce the symptoms or the length of hospital stay, nor do they reduce the possibility that intensive care with mechanical ventilation may be required. Treatments are only supportive. An effective vaccine remains elusive.

All other common infections that once resulted in high rates of hospitalization in the first year of life are now substantially reduced through vaccination. Why not this one? The development of a safe and effective vaccine to prevent infant RSV infection or to reduce RSV-associated hospitalizations is especially challenging for multiple reasons.

Some of these reasons have met with substantial advances quite recently, including the discovery of antigen structures needed to induce neutralizing antibody responses. There also are challenges specific to the infant group we need most to protect. Infant RSV infection itself confers only modest protection against subsequent infection. Repeated infections over time are necessary for protection against illness when re-exposed. A vaccine that is able to induce a response similar to natural infection would therefore require multiple doses, presumably over time (the so called ‘primary series’) before a substantial clinical benefit would be expected. This is particularly important because most RSV-associated hospitalizations occur during the first several months of life, reducing the timeline for which a protective vaccine series could be administered.

The challenges are parallel to the issues described earlier for protection against both influenza and pertussis. Infant protection against both of these infections are now addressed, at least to start with, by vaccinating the mother during her pregnancy. In the infant, the pertussis vaccine primary series is then initiated between 6 and 8 weeks of age, and the influenza series initiated at 6 months of age. It is the passive protection, in the form of transplacental maternal antibody, that offers the interim protection during the highest-risk first months of life.

For infants at very high risk of serious RSV infection, passive antibody protection is already administered in the form of the pharmacobiologic medication palivizumab. Its half-life dictates monthly injections for those eligible, and its cost precludes its use for any but the highest risk infants (those born prematurely, and those with chronic lung disease and/or congenital heart disease). This strategy, however, has proven effective in preventing RSV-associated hospitalization in every group in which it has been studied. This “proof of concept” strongly suggests that if the right RSV vaccine is given to women during pregnancy to induce a robust neutralizing anti-RSV antibody response, and that antibody is transferred to the fetus prior to birth, the newborn will benefit from protection against RSV for a period of time.

Several questions emerge. If RSV is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime, then some women will be infected during their pregnancy. Do their infants benefit? As a re-infection, the maternal symptoms would be expected to be mild, but the infection could boost the women’s natural immunity with a robust anamnestic antibody response. This possibility has not been studied systematically, but might help to explain why some healthy term infants exposed to RSV develop little or no symptoms, while others (mothers who have not recently had a natural RSV infection) develop severe illness requiring hospitalization.

There are data to support the contention that term infants born to mothers with higher naturally occurring anti-RSV neutralizing antibodies benefit from those antibodies. In a large prospective cohort study performed in Kenya, cord blood anti-RSV antibody concentrations correlated directly with the length of time before the infant’s first RSV infection. It’s therefore logical to conclude that administering an effective RSV vaccine during pregnancy could augment that natural antibody response, be transferred to the infant at birth, and offer protection against RSV when exposed.

Several candidate vaccines for study already exist and have undergone phase I testing in nonpregnant adults. Once safety is demonstrated, the next step is to identify the vaccine formulation resulting in the most robust anti-RSV neutralizing antibody concentrations. Such a candidate vaccine will be chosen for future phase III trials during pregnancy. Safety, and maternal/cord blood RSV antibody titers will be of interest during that clinical trial, but the rates and timing of RSV infection and RSV-associated hospitalizations among the infants born to those mothers will be the most instructive.

Ideally, a candidate RSV vaccine shown to be as safe and as effective during pregnancy as inactivated influenza vaccines and/or Tdap vaccines would be implemented immediately and universally. Unfortunately, substantial vaccine hesitancy for the use of influenza and Tdap vaccines continues among pregnant patients and their providers. Acceptance of an RSV vaccine for use during pregnancy will not come easily, or immediately. As with all of our successful vaccine programs, launching such an effort will require education, patience, and careful post-licensure documentation of the impact that the intervention has in the real world.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y. Dr. Domachowske is performing clinical trials and has grants in the area of RSV prevention with Astra Zeneca, Regeneron, and Glaxo Smith Kline.

Pediatricians and our teams are the immunization experts. We educate, advocate, and incorporate vaccines into much of our daily routine. As such, we recognize the importance of working with our colleagues in family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics to optimize immunization programs for high-risk individuals, including pregnant women. Recent advances in vaccine recommendations during pregnancy are a result of the collaborative efforts of the health care providers for these women, and from systematic evaluation of immunization programs, vaccine pregnancy registries, and disease epidemiology.

Vaccinating women during pregnancy should be considered when a vaccine is known to be safe and when the following apply:

• The risk of severe infection is high during or augmented by pregnancy.

• The specific infection during pregnancy threatens the fetus.

• Maternal protection against infection benefits the newborn.

• Passive transfer of antibody from mother to fetus benefits the newborn.

Examples of safe vaccines immediately come to mind that fulfill one of more of these criteria, yet substantial obstacles exist even where safety and effectiveness data are robust. Because clinical vaccine trials traditionally exclude pregnant women, safety and effectiveness data for this group and their newborns are limited and often must come through experience. In a climate of increased vaccine hesitancy in general, both among providers and patients, vaccine delivery can be fragmented and particularly difficult to streamline. Additional obstacles that exist for any immunization program, including one that targets pregnant women specifically, are immunization delivery logistics and cost.

One of the major success stories of maternal immunization that is easily forgotten or overlooked in developed parts of the world is in the prevention of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT). A review of recent history reminds us that between the years 2000 and 2014, 35 countries were finally successful in eliminating MNT, including China, Turkey, Egypt, and South Africa. In addition, 24 of 36 states in the country of India, 30 of 34 provinces of Indonesia, and most of Ethiopia have met with success. This has been accomplished through aggressive tetanus vaccination programs, and through education programs targeted at optimal umbilical cord stump care after delivery.

In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all pregnant women should receive inactivated influenza vaccine and Tdap vaccine. In addition, several other vaccines are recommended under certain circumstances. Live attenuated vaccines are considered contraindicated, although yellow fever vaccine is an exception during epidemics, or when travel to a highly endemic area during pregnancy cannot be avoided.

Influenza vaccine administered during pregnancy reduces maternal morbidity and mortality. Moreover, safety and benefits for the fetus are clearly documented. Both retrospective cohort analysis studies and randomized controlled trials have consistently demonstrated lower risk of preterm birth and lower risk for delivering newborns small for gestational age among women who received inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy. The benefit extends to term healthy infants who are less likely to be hospitalized during the first months of life if their mother was vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy. Because the mother was immunized during pregnancy, it reduces her risk of infection, thereby reducing the potential that the newborn will be exposed to a mother who is contagious. Perhaps more importantly, infants born at or near term have the benefit of transplacental antibody endowment from their mother, including vaccine induced anti-influenza antibodies. This passive protection is expected to last for several months. Active immunization against influenza during infancy begins at 6 months of age.

Tdap vaccine is also recommended during each pregnancy. In the United States, MNT is eliminated. Here, as in other developed countries, Tdap is administered to reduce infant pertussis morbidity. Pertussis remains endemic to the United States, and infants who develop whooping cough during the first 2-3 months of life are at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality.

Historically, one-third of infants infected with pertussis were infected by their mother, although more recent evidence suggests that older siblings are at least as likely a source. Looking back to the paradigm for protection against influenza infection in the first few months of life, it becomes clear why the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended Tdap vaccine for all mothers during each pregnancy.

The first goal is to prevent pertussis in the mother so that she will not transmit the infection to her newborn. The additional goal, and the rationale for vaccinating pregnant women during every pregnancy, is to optimize levels of anti-pertussis antibody in the mother, so that the transplacental endowment to the infant is as robust as possible.

Serologic studies have demonstrated that Tdap vaccine induces high anti-pertussis antibodies when administered during pregnancy, but that the half-life of those antibodies is brief. When Tdap is given during pregnancy, and the infant is born at or near term, the antibody transfer to the infant is expected to provide passive protection for several months. Maternal immunization during pregnancy thereby reduces the risk that the mother will develop pertussis and transmit it to her newborn, while at the same time allows a degree of passive immunoprotection to the infant during the most vulnerable period of life. Active immunization against pertussis in the infant begins between 6-8 weeks of age.

Another infection that is exceedingly common during the first several months of life is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV remains the most common reason for infant hospitalization in the United States and other developed countries. The source of the virus can be any other person with a mild or moderate respiratory tract infection as the virus is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime. The first infection, however, is the worst. It is estimated that between 3% and 4% of the U.S. birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV. With a U.S. birth cohort of about 4 million, the result is 120,000-160,000 infant admissions annually.

The RSV epidemic is seasonal, fairly predictable, and dreaded by primary care pediatricians and hospitalists alike. Lower respiratory tract infection with RSV, in the form of RSV bronchiolitis, presents all too commonly in the young infant with cough, coryza, tachypnea, and wheezing. When the work of breathing increases, and the cough symptoms predominate, the infant is unable to feed efficiently. Hospitalizations may be for dehydration, concerns for impending respiratory failure, or for the administration of supplemental oxygen or other respiratory support. No specific therapeutic interventions reliably reduce the symptoms or the length of hospital stay, nor do they reduce the possibility that intensive care with mechanical ventilation may be required. Treatments are only supportive. An effective vaccine remains elusive.

All other common infections that once resulted in high rates of hospitalization in the first year of life are now substantially reduced through vaccination. Why not this one? The development of a safe and effective vaccine to prevent infant RSV infection or to reduce RSV-associated hospitalizations is especially challenging for multiple reasons.

Some of these reasons have met with substantial advances quite recently, including the discovery of antigen structures needed to induce neutralizing antibody responses. There also are challenges specific to the infant group we need most to protect. Infant RSV infection itself confers only modest protection against subsequent infection. Repeated infections over time are necessary for protection against illness when re-exposed. A vaccine that is able to induce a response similar to natural infection would therefore require multiple doses, presumably over time (the so called ‘primary series’) before a substantial clinical benefit would be expected. This is particularly important because most RSV-associated hospitalizations occur during the first several months of life, reducing the timeline for which a protective vaccine series could be administered.

The challenges are parallel to the issues described earlier for protection against both influenza and pertussis. Infant protection against both of these infections are now addressed, at least to start with, by vaccinating the mother during her pregnancy. In the infant, the pertussis vaccine primary series is then initiated between 6 and 8 weeks of age, and the influenza series initiated at 6 months of age. It is the passive protection, in the form of transplacental maternal antibody, that offers the interim protection during the highest-risk first months of life.

For infants at very high risk of serious RSV infection, passive antibody protection is already administered in the form of the pharmacobiologic medication palivizumab. Its half-life dictates monthly injections for those eligible, and its cost precludes its use for any but the highest risk infants (those born prematurely, and those with chronic lung disease and/or congenital heart disease). This strategy, however, has proven effective in preventing RSV-associated hospitalization in every group in which it has been studied. This “proof of concept” strongly suggests that if the right RSV vaccine is given to women during pregnancy to induce a robust neutralizing anti-RSV antibody response, and that antibody is transferred to the fetus prior to birth, the newborn will benefit from protection against RSV for a period of time.

Several questions emerge. If RSV is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime, then some women will be infected during their pregnancy. Do their infants benefit? As a re-infection, the maternal symptoms would be expected to be mild, but the infection could boost the women’s natural immunity with a robust anamnestic antibody response. This possibility has not been studied systematically, but might help to explain why some healthy term infants exposed to RSV develop little or no symptoms, while others (mothers who have not recently had a natural RSV infection) develop severe illness requiring hospitalization.

There are data to support the contention that term infants born to mothers with higher naturally occurring anti-RSV neutralizing antibodies benefit from those antibodies. In a large prospective cohort study performed in Kenya, cord blood anti-RSV antibody concentrations correlated directly with the length of time before the infant’s first RSV infection. It’s therefore logical to conclude that administering an effective RSV vaccine during pregnancy could augment that natural antibody response, be transferred to the infant at birth, and offer protection against RSV when exposed.

Several candidate vaccines for study already exist and have undergone phase I testing in nonpregnant adults. Once safety is demonstrated, the next step is to identify the vaccine formulation resulting in the most robust anti-RSV neutralizing antibody concentrations. Such a candidate vaccine will be chosen for future phase III trials during pregnancy. Safety, and maternal/cord blood RSV antibody titers will be of interest during that clinical trial, but the rates and timing of RSV infection and RSV-associated hospitalizations among the infants born to those mothers will be the most instructive.

Ideally, a candidate RSV vaccine shown to be as safe and as effective during pregnancy as inactivated influenza vaccines and/or Tdap vaccines would be implemented immediately and universally. Unfortunately, substantial vaccine hesitancy for the use of influenza and Tdap vaccines continues among pregnant patients and their providers. Acceptance of an RSV vaccine for use during pregnancy will not come easily, or immediately. As with all of our successful vaccine programs, launching such an effort will require education, patience, and careful post-licensure documentation of the impact that the intervention has in the real world.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y. Dr. Domachowske is performing clinical trials and has grants in the area of RSV prevention with Astra Zeneca, Regeneron, and Glaxo Smith Kline.

Pediatricians and our teams are the immunization experts. We educate, advocate, and incorporate vaccines into much of our daily routine. As such, we recognize the importance of working with our colleagues in family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics to optimize immunization programs for high-risk individuals, including pregnant women. Recent advances in vaccine recommendations during pregnancy are a result of the collaborative efforts of the health care providers for these women, and from systematic evaluation of immunization programs, vaccine pregnancy registries, and disease epidemiology.

Vaccinating women during pregnancy should be considered when a vaccine is known to be safe and when the following apply:

• The risk of severe infection is high during or augmented by pregnancy.

• The specific infection during pregnancy threatens the fetus.

• Maternal protection against infection benefits the newborn.

• Passive transfer of antibody from mother to fetus benefits the newborn.

Examples of safe vaccines immediately come to mind that fulfill one of more of these criteria, yet substantial obstacles exist even where safety and effectiveness data are robust. Because clinical vaccine trials traditionally exclude pregnant women, safety and effectiveness data for this group and their newborns are limited and often must come through experience. In a climate of increased vaccine hesitancy in general, both among providers and patients, vaccine delivery can be fragmented and particularly difficult to streamline. Additional obstacles that exist for any immunization program, including one that targets pregnant women specifically, are immunization delivery logistics and cost.

One of the major success stories of maternal immunization that is easily forgotten or overlooked in developed parts of the world is in the prevention of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT). A review of recent history reminds us that between the years 2000 and 2014, 35 countries were finally successful in eliminating MNT, including China, Turkey, Egypt, and South Africa. In addition, 24 of 36 states in the country of India, 30 of 34 provinces of Indonesia, and most of Ethiopia have met with success. This has been accomplished through aggressive tetanus vaccination programs, and through education programs targeted at optimal umbilical cord stump care after delivery.

In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that all pregnant women should receive inactivated influenza vaccine and Tdap vaccine. In addition, several other vaccines are recommended under certain circumstances. Live attenuated vaccines are considered contraindicated, although yellow fever vaccine is an exception during epidemics, or when travel to a highly endemic area during pregnancy cannot be avoided.

Influenza vaccine administered during pregnancy reduces maternal morbidity and mortality. Moreover, safety and benefits for the fetus are clearly documented. Both retrospective cohort analysis studies and randomized controlled trials have consistently demonstrated lower risk of preterm birth and lower risk for delivering newborns small for gestational age among women who received inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy. The benefit extends to term healthy infants who are less likely to be hospitalized during the first months of life if their mother was vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy. Because the mother was immunized during pregnancy, it reduces her risk of infection, thereby reducing the potential that the newborn will be exposed to a mother who is contagious. Perhaps more importantly, infants born at or near term have the benefit of transplacental antibody endowment from their mother, including vaccine induced anti-influenza antibodies. This passive protection is expected to last for several months. Active immunization against influenza during infancy begins at 6 months of age.

Tdap vaccine is also recommended during each pregnancy. In the United States, MNT is eliminated. Here, as in other developed countries, Tdap is administered to reduce infant pertussis morbidity. Pertussis remains endemic to the United States, and infants who develop whooping cough during the first 2-3 months of life are at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality.

Historically, one-third of infants infected with pertussis were infected by their mother, although more recent evidence suggests that older siblings are at least as likely a source. Looking back to the paradigm for protection against influenza infection in the first few months of life, it becomes clear why the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended Tdap vaccine for all mothers during each pregnancy.

The first goal is to prevent pertussis in the mother so that she will not transmit the infection to her newborn. The additional goal, and the rationale for vaccinating pregnant women during every pregnancy, is to optimize levels of anti-pertussis antibody in the mother, so that the transplacental endowment to the infant is as robust as possible.

Serologic studies have demonstrated that Tdap vaccine induces high anti-pertussis antibodies when administered during pregnancy, but that the half-life of those antibodies is brief. When Tdap is given during pregnancy, and the infant is born at or near term, the antibody transfer to the infant is expected to provide passive protection for several months. Maternal immunization during pregnancy thereby reduces the risk that the mother will develop pertussis and transmit it to her newborn, while at the same time allows a degree of passive immunoprotection to the infant during the most vulnerable period of life. Active immunization against pertussis in the infant begins between 6-8 weeks of age.

Another infection that is exceedingly common during the first several months of life is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV remains the most common reason for infant hospitalization in the United States and other developed countries. The source of the virus can be any other person with a mild or moderate respiratory tract infection as the virus is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime. The first infection, however, is the worst. It is estimated that between 3% and 4% of the U.S. birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV. With a U.S. birth cohort of about 4 million, the result is 120,000-160,000 infant admissions annually.

The RSV epidemic is seasonal, fairly predictable, and dreaded by primary care pediatricians and hospitalists alike. Lower respiratory tract infection with RSV, in the form of RSV bronchiolitis, presents all too commonly in the young infant with cough, coryza, tachypnea, and wheezing. When the work of breathing increases, and the cough symptoms predominate, the infant is unable to feed efficiently. Hospitalizations may be for dehydration, concerns for impending respiratory failure, or for the administration of supplemental oxygen or other respiratory support. No specific therapeutic interventions reliably reduce the symptoms or the length of hospital stay, nor do they reduce the possibility that intensive care with mechanical ventilation may be required. Treatments are only supportive. An effective vaccine remains elusive.

All other common infections that once resulted in high rates of hospitalization in the first year of life are now substantially reduced through vaccination. Why not this one? The development of a safe and effective vaccine to prevent infant RSV infection or to reduce RSV-associated hospitalizations is especially challenging for multiple reasons.

Some of these reasons have met with substantial advances quite recently, including the discovery of antigen structures needed to induce neutralizing antibody responses. There also are challenges specific to the infant group we need most to protect. Infant RSV infection itself confers only modest protection against subsequent infection. Repeated infections over time are necessary for protection against illness when re-exposed. A vaccine that is able to induce a response similar to natural infection would therefore require multiple doses, presumably over time (the so called ‘primary series’) before a substantial clinical benefit would be expected. This is particularly important because most RSV-associated hospitalizations occur during the first several months of life, reducing the timeline for which a protective vaccine series could be administered.

The challenges are parallel to the issues described earlier for protection against both influenza and pertussis. Infant protection against both of these infections are now addressed, at least to start with, by vaccinating the mother during her pregnancy. In the infant, the pertussis vaccine primary series is then initiated between 6 and 8 weeks of age, and the influenza series initiated at 6 months of age. It is the passive protection, in the form of transplacental maternal antibody, that offers the interim protection during the highest-risk first months of life.

For infants at very high risk of serious RSV infection, passive antibody protection is already administered in the form of the pharmacobiologic medication palivizumab. Its half-life dictates monthly injections for those eligible, and its cost precludes its use for any but the highest risk infants (those born prematurely, and those with chronic lung disease and/or congenital heart disease). This strategy, however, has proven effective in preventing RSV-associated hospitalization in every group in which it has been studied. This “proof of concept” strongly suggests that if the right RSV vaccine is given to women during pregnancy to induce a robust neutralizing anti-RSV antibody response, and that antibody is transferred to the fetus prior to birth, the newborn will benefit from protection against RSV for a period of time.

Several questions emerge. If RSV is ubiquitous, and can re-infect individuals throughout their lifetime, then some women will be infected during their pregnancy. Do their infants benefit? As a re-infection, the maternal symptoms would be expected to be mild, but the infection could boost the women’s natural immunity with a robust anamnestic antibody response. This possibility has not been studied systematically, but might help to explain why some healthy term infants exposed to RSV develop little or no symptoms, while others (mothers who have not recently had a natural RSV infection) develop severe illness requiring hospitalization.

There are data to support the contention that term infants born to mothers with higher naturally occurring anti-RSV neutralizing antibodies benefit from those antibodies. In a large prospective cohort study performed in Kenya, cord blood anti-RSV antibody concentrations correlated directly with the length of time before the infant’s first RSV infection. It’s therefore logical to conclude that administering an effective RSV vaccine during pregnancy could augment that natural antibody response, be transferred to the infant at birth, and offer protection against RSV when exposed.

Several candidate vaccines for study already exist and have undergone phase I testing in nonpregnant adults. Once safety is demonstrated, the next step is to identify the vaccine formulation resulting in the most robust anti-RSV neutralizing antibody concentrations. Such a candidate vaccine will be chosen for future phase III trials during pregnancy. Safety, and maternal/cord blood RSV antibody titers will be of interest during that clinical trial, but the rates and timing of RSV infection and RSV-associated hospitalizations among the infants born to those mothers will be the most instructive.

Ideally, a candidate RSV vaccine shown to be as safe and as effective during pregnancy as inactivated influenza vaccines and/or Tdap vaccines would be implemented immediately and universally. Unfortunately, substantial vaccine hesitancy for the use of influenza and Tdap vaccines continues among pregnant patients and their providers. Acceptance of an RSV vaccine for use during pregnancy will not come easily, or immediately. As with all of our successful vaccine programs, launching such an effort will require education, patience, and careful post-licensure documentation of the impact that the intervention has in the real world.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y. Dr. Domachowske is performing clinical trials and has grants in the area of RSV prevention with Astra Zeneca, Regeneron, and Glaxo Smith Kline.

Practice guideline released for treating opioid use disorder

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released a practice guideline to help clinicians evaluate and treat opioid use disorder, with the ultimate goal of getting more physicians to provide effective treatment.

Effective treatment of opioid use disorder “requires skill and time that are not generally available to primary care doctors in most practice models,” so much of the treatment provided in primary care has been “suboptimal.” This has probably worsened what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described as an epidemic of opioid misuse and related deaths, said Dr. Kyle Kampman and Dr. Margaret Jarvis, cochairs of the ASAM’s guideline committee.

“At the same time, access to competent treatment is profoundly restricted because few physicians are willing and able to provide it,” they noted.

This guideline “is primarily intended for clinicians involved in evaluating patients and providing authorization for pharmacologic treatments at any level,” said Dr. Kampman of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and Dr. Jarvis, of the Marworth Alcohol & Chemical Dependency Center, an entity of the Geisinger Health System, Waverly, Pa.

To develop the guideline, the committee – experts and researchers in internal medicine, family medicine, addiction medicine, addiction psychiatry, general psychiatry, obstetrics, pharmacology, and neurobiology, including some with allopathic or osteopathic training – first reviewed 34 existing clinical guidelines and 27 recent studies in the literature assessing medications used with psychosocial interventions. None of the existing guidelines included all the medications currently in use, and few addressed critical special populations such as pregnant women, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, and patients with chronic pain.

The ASAM guideline specifically addresses these and other special populations (for example, adolescents, patients in the criminal justice system). It includes detailed sections on treating opioid withdrawal and opioid overdose, as well as comprehensive discussions of methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, and psychosocial therapies.

The guideline offers numerous clinical recommendations regarding patient assessment and diagnosis (J Addict Med. 2015;9:358:67).

First, “addiction should be considered a bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness, for which the use of medication(s) is but only one component of overall treatment.” In addition to a thorough history and physical exam (including specific laboratory tests needed for this patient population), patients should undergo a mental health assessment with particular attention to possible psychiatric comorbidities. And since opioid use often co-occurs with other substance-related disorders, “the totality of substances that surround the addiction” should be assessed before treatment is considered.

Notably, the concomitant use of alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics with opioids can cause respiratory depression. Patients who use these agents may automatically require a higher level of care than that offered in typical primary care practices.

As well, social and environmental factors should be assessed, to identify both barriers to and facilitators for addiction treatment in general and pharmacotherapy in particular. “At a minimum, psychosocial treatment should include the following: psychosocial needs assessment, supportive counseling, links to existing family supports, and referrals to community services.” Physicians should be prepared to collaborate with qualified behavioral health care providers, the guideline states.

Urinary drug testing is recommended, both during the assessment process and frequently throughout treatment.

Regarding treatment, the guideline recommends considering the patient’s preferences, past treatment history, and the treatment setting when deciding whether to prescribe methadone, bupenorphrine, or naltrexone. The treatment venue is as important as the specific medication selected. Office-based treatment, which provides medication prescribed either weekly or monthly, is limited to buprenorphine only. It might not be suitable for patients who regularly use alcohol or other substances.

In contrast, treatment programs provide daily supervised dosing of methadone and, increasingly, buprenorphine. Methadone is recommended for patients who fail on buprenorphine or who would benefit from daily dosing and supervision.

Naltrexone can be prescribed in any setting by any clinician, but prescribers must be aware that adherence to oral naltrexone is generally poor, which often leads to treatment failure. Extended-release injectable naltrexone reduces but doesn’t eliminate adherence issues. Clinicians should reserve naltrexone “for patients who would be able to comply with special techniques to enhance their adherence, such as observed dosing.”

Dr. Kampton disclosed research ties with Braeburn Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Jarvis disclosed business ties with U.S. Preventive Medicine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released a practice guideline to help clinicians evaluate and treat opioid use disorder, with the ultimate goal of getting more physicians to provide effective treatment.

Effective treatment of opioid use disorder “requires skill and time that are not generally available to primary care doctors in most practice models,” so much of the treatment provided in primary care has been “suboptimal.” This has probably worsened what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described as an epidemic of opioid misuse and related deaths, said Dr. Kyle Kampman and Dr. Margaret Jarvis, cochairs of the ASAM’s guideline committee.

“At the same time, access to competent treatment is profoundly restricted because few physicians are willing and able to provide it,” they noted.

This guideline “is primarily intended for clinicians involved in evaluating patients and providing authorization for pharmacologic treatments at any level,” said Dr. Kampman of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and Dr. Jarvis, of the Marworth Alcohol & Chemical Dependency Center, an entity of the Geisinger Health System, Waverly, Pa.

To develop the guideline, the committee – experts and researchers in internal medicine, family medicine, addiction medicine, addiction psychiatry, general psychiatry, obstetrics, pharmacology, and neurobiology, including some with allopathic or osteopathic training – first reviewed 34 existing clinical guidelines and 27 recent studies in the literature assessing medications used with psychosocial interventions. None of the existing guidelines included all the medications currently in use, and few addressed critical special populations such as pregnant women, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, and patients with chronic pain.

The ASAM guideline specifically addresses these and other special populations (for example, adolescents, patients in the criminal justice system). It includes detailed sections on treating opioid withdrawal and opioid overdose, as well as comprehensive discussions of methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, and psychosocial therapies.

The guideline offers numerous clinical recommendations regarding patient assessment and diagnosis (J Addict Med. 2015;9:358:67).

First, “addiction should be considered a bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness, for which the use of medication(s) is but only one component of overall treatment.” In addition to a thorough history and physical exam (including specific laboratory tests needed for this patient population), patients should undergo a mental health assessment with particular attention to possible psychiatric comorbidities. And since opioid use often co-occurs with other substance-related disorders, “the totality of substances that surround the addiction” should be assessed before treatment is considered.

Notably, the concomitant use of alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics with opioids can cause respiratory depression. Patients who use these agents may automatically require a higher level of care than that offered in typical primary care practices.

As well, social and environmental factors should be assessed, to identify both barriers to and facilitators for addiction treatment in general and pharmacotherapy in particular. “At a minimum, psychosocial treatment should include the following: psychosocial needs assessment, supportive counseling, links to existing family supports, and referrals to community services.” Physicians should be prepared to collaborate with qualified behavioral health care providers, the guideline states.

Urinary drug testing is recommended, both during the assessment process and frequently throughout treatment.

Regarding treatment, the guideline recommends considering the patient’s preferences, past treatment history, and the treatment setting when deciding whether to prescribe methadone, bupenorphrine, or naltrexone. The treatment venue is as important as the specific medication selected. Office-based treatment, which provides medication prescribed either weekly or monthly, is limited to buprenorphine only. It might not be suitable for patients who regularly use alcohol or other substances.

In contrast, treatment programs provide daily supervised dosing of methadone and, increasingly, buprenorphine. Methadone is recommended for patients who fail on buprenorphine or who would benefit from daily dosing and supervision.

Naltrexone can be prescribed in any setting by any clinician, but prescribers must be aware that adherence to oral naltrexone is generally poor, which often leads to treatment failure. Extended-release injectable naltrexone reduces but doesn’t eliminate adherence issues. Clinicians should reserve naltrexone “for patients who would be able to comply with special techniques to enhance their adherence, such as observed dosing.”

Dr. Kampton disclosed research ties with Braeburn Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Jarvis disclosed business ties with U.S. Preventive Medicine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released a practice guideline to help clinicians evaluate and treat opioid use disorder, with the ultimate goal of getting more physicians to provide effective treatment.

Effective treatment of opioid use disorder “requires skill and time that are not generally available to primary care doctors in most practice models,” so much of the treatment provided in primary care has been “suboptimal.” This has probably worsened what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described as an epidemic of opioid misuse and related deaths, said Dr. Kyle Kampman and Dr. Margaret Jarvis, cochairs of the ASAM’s guideline committee.

“At the same time, access to competent treatment is profoundly restricted because few physicians are willing and able to provide it,” they noted.

This guideline “is primarily intended for clinicians involved in evaluating patients and providing authorization for pharmacologic treatments at any level,” said Dr. Kampman of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and Dr. Jarvis, of the Marworth Alcohol & Chemical Dependency Center, an entity of the Geisinger Health System, Waverly, Pa.

To develop the guideline, the committee – experts and researchers in internal medicine, family medicine, addiction medicine, addiction psychiatry, general psychiatry, obstetrics, pharmacology, and neurobiology, including some with allopathic or osteopathic training – first reviewed 34 existing clinical guidelines and 27 recent studies in the literature assessing medications used with psychosocial interventions. None of the existing guidelines included all the medications currently in use, and few addressed critical special populations such as pregnant women, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, and patients with chronic pain.

The ASAM guideline specifically addresses these and other special populations (for example, adolescents, patients in the criminal justice system). It includes detailed sections on treating opioid withdrawal and opioid overdose, as well as comprehensive discussions of methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, and psychosocial therapies.

The guideline offers numerous clinical recommendations regarding patient assessment and diagnosis (J Addict Med. 2015;9:358:67).

First, “addiction should be considered a bio-psycho-social-spiritual illness, for which the use of medication(s) is but only one component of overall treatment.” In addition to a thorough history and physical exam (including specific laboratory tests needed for this patient population), patients should undergo a mental health assessment with particular attention to possible psychiatric comorbidities. And since opioid use often co-occurs with other substance-related disorders, “the totality of substances that surround the addiction” should be assessed before treatment is considered.

Notably, the concomitant use of alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics with opioids can cause respiratory depression. Patients who use these agents may automatically require a higher level of care than that offered in typical primary care practices.

As well, social and environmental factors should be assessed, to identify both barriers to and facilitators for addiction treatment in general and pharmacotherapy in particular. “At a minimum, psychosocial treatment should include the following: psychosocial needs assessment, supportive counseling, links to existing family supports, and referrals to community services.” Physicians should be prepared to collaborate with qualified behavioral health care providers, the guideline states.

Urinary drug testing is recommended, both during the assessment process and frequently throughout treatment.

Regarding treatment, the guideline recommends considering the patient’s preferences, past treatment history, and the treatment setting when deciding whether to prescribe methadone, bupenorphrine, or naltrexone. The treatment venue is as important as the specific medication selected. Office-based treatment, which provides medication prescribed either weekly or monthly, is limited to buprenorphine only. It might not be suitable for patients who regularly use alcohol or other substances.

In contrast, treatment programs provide daily supervised dosing of methadone and, increasingly, buprenorphine. Methadone is recommended for patients who fail on buprenorphine or who would benefit from daily dosing and supervision.

Naltrexone can be prescribed in any setting by any clinician, but prescribers must be aware that adherence to oral naltrexone is generally poor, which often leads to treatment failure. Extended-release injectable naltrexone reduces but doesn’t eliminate adherence issues. Clinicians should reserve naltrexone “for patients who would be able to comply with special techniques to enhance their adherence, such as observed dosing.”

Dr. Kampton disclosed research ties with Braeburn Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Jarvis disclosed business ties with U.S. Preventive Medicine.

FROM JOURNAL OF ADDICTION MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The American Society of Addiction Medicine has released a clinical practice guideline that discusses all of the medications used in treating opioid use disorder as well as treating special populations.

Major finding: Access to competent treatment of opioid use disorder has been “profoundly restricted,” because few physicians are willing and able to provide it.

Data source: A review of 34 existing clinical guidelines and 27 studies of treatments, and a compilation of clinical recommendations for treating opioid use disorder.

Disclosures: Dr. Kampton disclosed research ties with Braeburn Pharmaceuticals; Dr. Jarvis disclosed business ties with U.S. Preventive Medicine.

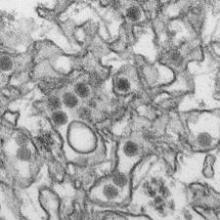

Zika virus: What clinicians must know

The recent spike in Zika virus cases in Central and South America brings with it the alarming risk – and even the expectation – of outbreaks occurring in the United States. How should U.S.-based clinicians prepare for the inevitable?

“The current outbreaks of Zika virus are the first of their kind in the Americas, so there isn’t a previous history of Zika virus spreading into the [United States],” explained Dr. Joy St. John, director of surveillance, disease prevention and control at the Caribbean Public Health Agency in Trinidad.

But now that the virus has hit the United States, with a confirmed case in Texas last week and more emerging since then, Dr. St. John said the most important thing is for U.S. health care providers to recognize the signs and symptoms of Zika virus infection. The virus is carried and transmitted by the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito, the same vector that transmits the dengue and chikungunya viruses. Zika virus symptoms are relatively mild, consisting predominantly of maculopapular rash, fever, arthralgia, myalgia, and conjunctivitis. Only one in five individuals with a Zika virus infection develop symptoms, but patients who present as such and who have traveled to Central or South America in the week prior to the onset of symptoms should be considered likely infected.

"At present, there is no rapid test available for diagnosis of Zika,” said Dr. St. John. “Diagnosis is primarily based on detection of viral RNA from clinical serum specimens in acutely ill patients.”

To that end, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can be conducted on serum samples collected within 3-5 days of symptom onset. Beyond that, elevated levels of IgM antibodies can be confirmed by serology, based on the neutralization, seroconversion, or four-fold increase of Zika-specific antibodies in paired samples. However, Dr. St. John warned that “Due to the possibility of cross reactivity with other viruses, for example, dengue, it is strongly recommended samples be collected early enough for PCR testing.”

Zika and pregnancy

Zika virus has now been identified in more than 20 countries and territories worldwide, most of them in the Americas, although outbreaks have occurred in areas of Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. While most infected patients experience relatively mild symptoms, Zika may be particularly dangerous when it infects a pregnant woman. There have been multiple cases of microcephaly in children whose mothers were infected with Zika virus during pregnancy, although the association of microcephaly with Zika virus infection during pregnancy has not been definitively confirmed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently issued a warning to Americans – particularly pregnant women – about traveling to high-risk areas.

“Scientifically, we’re not 100% sure if Zika virus is causing microcephaly, [but] what we’re seeing is in certain Brazilian districts, there’s been a 20-fold increase in rates of microcephaly at the same time that there’s been a lot more Zika virus in pregnant women,” explained Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake of Australian National University in Canberra.

According to data from the CDC, 1,248 suspected cases of microcephaly had been reported in Brazil as of Nov. 28, 2015, compared with the annual rate of just 150-200 such cases during 2010-2014. “Examination of the fetus [and] amniotic fluid, in some cases, has shown Zika virus, so there seems to be an association,” Dr. Senanayake clarified, adding that “the [ANVISA – Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency] has told women in certain districts where there’s been a lot of microcephaly not to get pregnant.”

Brazil is set to host millions of guests from around the world as the 2016 Olympics get underway in only a few months’ time. Women who are pregnant or anticipate becoming pregnant should consider the risks if they are planning to travel to Rio de Janeiro. The risk of microcephaly does not apply to infected women who are not pregnant, however, as the CDC states that “Zika virus usually remains in the blood of an infected person for only a few days to a week,” and therefore, “does not pose a risk of birth defects for future pregnancies.”

Dr. St. John also stated that “public health personnel are still cautioning pregnant women to take special care to avoid mosquito bites during their pregnancies,” adding that the “[Pan-American Health Organization] is working on their guidelines for surveillance of congenital abnormalities.”

Clinical insights