User login

SSI risk after cesarean is nearly double for Medicaid patients

SAN DIEGO – Medicaid patients were nearly twice as likely to develop surgical site infections after cesarean delivery than privately insured women, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The association remained even after researchers accounted for several demographic and clinical variables, Dr. Sarah Yi said in an interview at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“If we can identify a population that is at higher risk for health care–associated infections, then maybe we can intervene at some level,” said Dr. Yi of the division of healthcare quality promotion at the CDC. “If we can elucidate the mechanism better, it will give us other clues about where we can prevent infections.”

More than 1.2 million cesareans were performed in the United States in 2012, and low transverse C-sections ranked fifth among all procedures performed during hospital stays, Dr. Yi noted. Post-cesarean surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a major cause of expense and morbidity, but not many studies have evaluated the relationship between insurance type and the risk of SSIs or other health care–associated infections, she added.

To explore the issue, Dr. Yi and her associates analyzed national health care safety data for 2,769 women who had a cesarean delivery in New York in 2010 or 2011 and had either Medicaid or private insurance at the time of their delivery. The Medicaid group included 1,763 women, while the privately insured group included 1,006 women. Medicaid patients were younger, more likely to be Hispanic, black, or homeless, and were more often treated at government and teaching facilities than privately insured patients were.

After researchers accounted for age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, facility type, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, emergency and labor status, use of anesthesia, duration of surgery, and wound classification, Medicaid patients still had nearly double the risk of an SSI after cesarean as did their counterparts with private insurance (risk ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8; P = .02).

While homelessness could potentially increase the risk of SSI by limiting opportunities for self-care, social support, and clinical follow-up, Medicaid remained a significant predictor of SSI even after excluding homeless women from the analysis, Dr. Yi said.

But Medicaid might represent one, or several, factors that the model did not account for, such as socioeconomic status or prenatal care, said Dr. Yi.

Prenatal care, in particular, might have been lower among Medicaid patients for women who did not obtain coverage until after arriving at the hospital for delivery, she said. Inadequate prenatal care has been linked to complications after delivery, and the proportion of eligible women who are enrolled in Medicaid has been found to vary at different times during pregnancy, she added (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015 Jun 19;64[4]:1-19).

The CDC investigators plan to continue the research by trying to validate the association in other populations, in other years, and in other states, Dr. Yi said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Medicaid patients were nearly twice as likely to develop surgical site infections after cesarean delivery than privately insured women, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The association remained even after researchers accounted for several demographic and clinical variables, Dr. Sarah Yi said in an interview at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“If we can identify a population that is at higher risk for health care–associated infections, then maybe we can intervene at some level,” said Dr. Yi of the division of healthcare quality promotion at the CDC. “If we can elucidate the mechanism better, it will give us other clues about where we can prevent infections.”

More than 1.2 million cesareans were performed in the United States in 2012, and low transverse C-sections ranked fifth among all procedures performed during hospital stays, Dr. Yi noted. Post-cesarean surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a major cause of expense and morbidity, but not many studies have evaluated the relationship between insurance type and the risk of SSIs or other health care–associated infections, she added.

To explore the issue, Dr. Yi and her associates analyzed national health care safety data for 2,769 women who had a cesarean delivery in New York in 2010 or 2011 and had either Medicaid or private insurance at the time of their delivery. The Medicaid group included 1,763 women, while the privately insured group included 1,006 women. Medicaid patients were younger, more likely to be Hispanic, black, or homeless, and were more often treated at government and teaching facilities than privately insured patients were.

After researchers accounted for age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, facility type, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, emergency and labor status, use of anesthesia, duration of surgery, and wound classification, Medicaid patients still had nearly double the risk of an SSI after cesarean as did their counterparts with private insurance (risk ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8; P = .02).

While homelessness could potentially increase the risk of SSI by limiting opportunities for self-care, social support, and clinical follow-up, Medicaid remained a significant predictor of SSI even after excluding homeless women from the analysis, Dr. Yi said.

But Medicaid might represent one, or several, factors that the model did not account for, such as socioeconomic status or prenatal care, said Dr. Yi.

Prenatal care, in particular, might have been lower among Medicaid patients for women who did not obtain coverage until after arriving at the hospital for delivery, she said. Inadequate prenatal care has been linked to complications after delivery, and the proportion of eligible women who are enrolled in Medicaid has been found to vary at different times during pregnancy, she added (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015 Jun 19;64[4]:1-19).

The CDC investigators plan to continue the research by trying to validate the association in other populations, in other years, and in other states, Dr. Yi said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Medicaid patients were nearly twice as likely to develop surgical site infections after cesarean delivery than privately insured women, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The association remained even after researchers accounted for several demographic and clinical variables, Dr. Sarah Yi said in an interview at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“If we can identify a population that is at higher risk for health care–associated infections, then maybe we can intervene at some level,” said Dr. Yi of the division of healthcare quality promotion at the CDC. “If we can elucidate the mechanism better, it will give us other clues about where we can prevent infections.”

More than 1.2 million cesareans were performed in the United States in 2012, and low transverse C-sections ranked fifth among all procedures performed during hospital stays, Dr. Yi noted. Post-cesarean surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a major cause of expense and morbidity, but not many studies have evaluated the relationship between insurance type and the risk of SSIs or other health care–associated infections, she added.

To explore the issue, Dr. Yi and her associates analyzed national health care safety data for 2,769 women who had a cesarean delivery in New York in 2010 or 2011 and had either Medicaid or private insurance at the time of their delivery. The Medicaid group included 1,763 women, while the privately insured group included 1,006 women. Medicaid patients were younger, more likely to be Hispanic, black, or homeless, and were more often treated at government and teaching facilities than privately insured patients were.

After researchers accounted for age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, facility type, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, emergency and labor status, use of anesthesia, duration of surgery, and wound classification, Medicaid patients still had nearly double the risk of an SSI after cesarean as did their counterparts with private insurance (risk ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8; P = .02).

While homelessness could potentially increase the risk of SSI by limiting opportunities for self-care, social support, and clinical follow-up, Medicaid remained a significant predictor of SSI even after excluding homeless women from the analysis, Dr. Yi said.

But Medicaid might represent one, or several, factors that the model did not account for, such as socioeconomic status or prenatal care, said Dr. Yi.

Prenatal care, in particular, might have been lower among Medicaid patients for women who did not obtain coverage until after arriving at the hospital for delivery, she said. Inadequate prenatal care has been linked to complications after delivery, and the proportion of eligible women who are enrolled in Medicaid has been found to vary at different times during pregnancy, she added (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015 Jun 19;64[4]:1-19).

The CDC investigators plan to continue the research by trying to validate the association in other populations, in other years, and in other states, Dr. Yi said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Medicaid patients had about a twofold higher risk of surgical site infections after cesarean delivery than did privately insured women.

Major finding: The association between Medicaid coverage and surgical site infections after cesarean delivery remained significant after researchers controlled for several potential confounders (risk ratio, 1.8; P = .02).

Data source: Analysis of national health care safety data for 2,769 women who had a cesarean in New York in 2010 or 2011.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Hospitals improve breastfeeding support

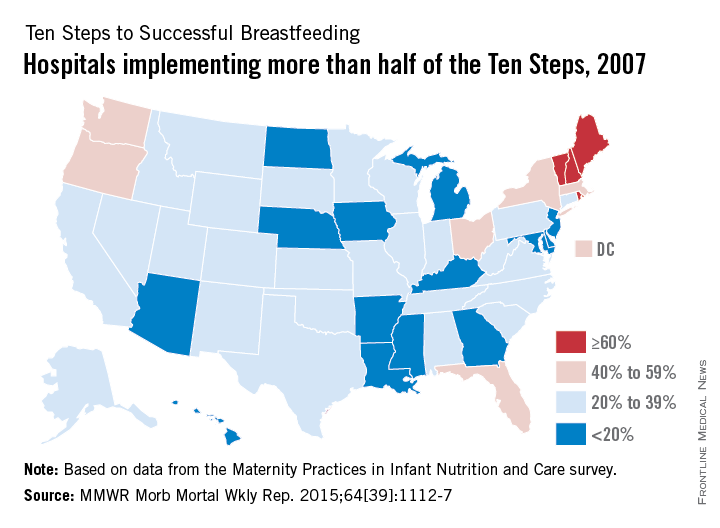

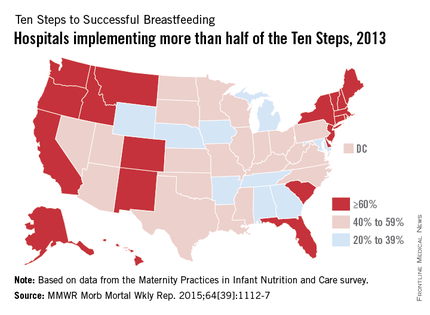

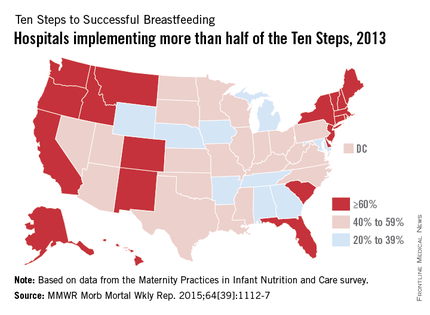

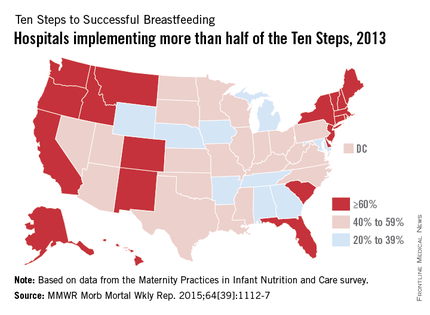

The number of hospitals implementing a majority of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, a global standard for hospital care, nearly doubled from 2007 to 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Oct. 8.

Almost 54% of hospitals nationwide had implemented more than half of the Ten Steps by 2013, compared with 28.7% in 2007, according to data from the biennial Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[39]:1112-7).

The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding are policies and practices that form the core of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, a program launched in 1991 by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. The Ten Steps that hospitals can take include:

• “Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.”

• “Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth.”

• “Practice rooming-in – allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours per day.”

Since 2007, when the CDC first surveyed hospitals regarding the Ten Steps, the number of states with more than 60% of hospitals implementing a majority of the steps increased from 4 to 21; the number of states with less than 20% of hospitals implementing a majority dropped from 15 to 0, the CDC noted.

“Breastfeeding has immense health benefits for babies and their mothers,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a written statement. “More hospitals are better supporting new moms to breastfeed – every newborn should have the best possible start in life.”

The number of hospitals implementing a majority of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, a global standard for hospital care, nearly doubled from 2007 to 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Oct. 8.

Almost 54% of hospitals nationwide had implemented more than half of the Ten Steps by 2013, compared with 28.7% in 2007, according to data from the biennial Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[39]:1112-7).

The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding are policies and practices that form the core of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, a program launched in 1991 by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. The Ten Steps that hospitals can take include:

• “Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.”

• “Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth.”

• “Practice rooming-in – allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours per day.”

Since 2007, when the CDC first surveyed hospitals regarding the Ten Steps, the number of states with more than 60% of hospitals implementing a majority of the steps increased from 4 to 21; the number of states with less than 20% of hospitals implementing a majority dropped from 15 to 0, the CDC noted.

“Breastfeeding has immense health benefits for babies and their mothers,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a written statement. “More hospitals are better supporting new moms to breastfeed – every newborn should have the best possible start in life.”

The number of hospitals implementing a majority of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, a global standard for hospital care, nearly doubled from 2007 to 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Oct. 8.

Almost 54% of hospitals nationwide had implemented more than half of the Ten Steps by 2013, compared with 28.7% in 2007, according to data from the biennial Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[39]:1112-7).

The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding are policies and practices that form the core of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, a program launched in 1991 by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. The Ten Steps that hospitals can take include:

• “Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.”

• “Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth.”

• “Practice rooming-in – allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours per day.”

Since 2007, when the CDC first surveyed hospitals regarding the Ten Steps, the number of states with more than 60% of hospitals implementing a majority of the steps increased from 4 to 21; the number of states with less than 20% of hospitals implementing a majority dropped from 15 to 0, the CDC noted.

“Breastfeeding has immense health benefits for babies and their mothers,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a written statement. “More hospitals are better supporting new moms to breastfeed – every newborn should have the best possible start in life.”

FROM MMWR

CDC: Hospital support of breastfeeding grows, but improvements needed

Hospital support for breastfeeding mothers has nearly doubled nationwide through a global initiative, but more work is needed to increase the number of baby-friendly hospitals, according to an Oct. 6 Vital Signs report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The report found the rate of U.S. hospitals using the World Health Organization’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding rose from 29% in 2007 to 54% in 2013.

“What happens in the hospital can determine whether a mom starts and continues to breastfeed, and we know that many moms – 60% – stop breastfeeding earlier than they’d like,” said CDC epidemiologist Cria Perrine, PhD, in a statement. “These improvements in hospital support for breastfeeding are promising, but we also want to see more hospitals fully supporting mothers who want to breastfeed. The Ten Steps help ensure that mothers get the best start with breastfeeding.”

Of the nearly 4 million babies born each year in the United States, 14% are born in “baby-friendly” hospitals, a number that has almost tripled in recent years, but remains low, according to the CDC. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative was established by the World Health Organization and UNICEF and is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The core of the initiative is the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, which measures a hospital’s breastfeeding support before, during, and after a mother’s hospital stay.

The report, “Vital Signs: Improvements in Maternity Care Policies and Practices That Support Breastfeeding — United States, 2007–2013,” examined data from CDC’s national survey, Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, which measures the percentage of U.S. hospitals with practices that are consistent with the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Findings showed that in 2013, 93% of hospitals provided high levels of: prenatal breastfeeding education, up from 91% in 2007. A majority of hospitals also taught mothers breastfeeding techniques – 92% in 2013 compared with 88% in 2007. Sixty-five percent of hospitals promoted early initiation of breastfeeding for mothers, up from 44% in 2007.

However, CDC leaders note that other findings demonstrate the need for improvement. For example, just over a quarter of hospitals surveyed had a model breastfeeding policy, commonly the foundation for many of the steps. Additionally, just 26% of hospitals ensured that only breast milk was given to healthy, breastfeeding infants who did not need infant formula for a medical reason in 2013. Only 45% of hospitals in 2013 kept mothers and babies together through their entire hospital stay, a practice which provides opportunities to breastfeed and helps mothers learn feeding cues, the report found. Just 32% of hospitals provided enough support for breastfeeding mothers when they left the hospital, including follow-up visits, phone calls, and referrals for additional support. These percentages were only slight increases from 2007, said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden during an Oct. 6 press conference.

“Every 1 of the 10 steps is important to use in the hospital to give babies the best start [and] to help mothers start and continue to breastfeed as recommended,” Dr. Frieden said. “I’d like to ask hospitals to keep making progress. Make a plan for what you can do right now that’s in line with the 10 steps, and phase that in over time. Ideally, we’d like every birth hospital in this country to adopt all of the 10 steps and become baby-friendly.”

Dr. Perrine acknowledged that hospitals are not without challenges in implementing the Ten Steps. Primary obstacles could be convincing hospital leadership to focus on the initiative, training staff, and confronting push-back from senior labor and delivery employees, Dr. Perrine said.

The CDC calls for more hospitals to implement the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and to work toward achieving baby-friendly status. Hospitals can also participate in CDC’s Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey and get an individualized report that shows how they compare with other hospitals. Additionally, hospitals should work with physicians, nurses, lactation care providers, and other organizations to develop networks that can provide clinic-based, at-home, or community breastfeeding support.

“Doctors can make a really big difference in encouraging and supporting women who choose to breastfeed,” Dr. Frieden said during the press conference. “And hospitals can play a critical role in those first few days of life which really do form the basis of the pattern of breastfeeding.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Hospital support for breastfeeding mothers has nearly doubled nationwide through a global initiative, but more work is needed to increase the number of baby-friendly hospitals, according to an Oct. 6 Vital Signs report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The report found the rate of U.S. hospitals using the World Health Organization’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding rose from 29% in 2007 to 54% in 2013.

“What happens in the hospital can determine whether a mom starts and continues to breastfeed, and we know that many moms – 60% – stop breastfeeding earlier than they’d like,” said CDC epidemiologist Cria Perrine, PhD, in a statement. “These improvements in hospital support for breastfeeding are promising, but we also want to see more hospitals fully supporting mothers who want to breastfeed. The Ten Steps help ensure that mothers get the best start with breastfeeding.”

Of the nearly 4 million babies born each year in the United States, 14% are born in “baby-friendly” hospitals, a number that has almost tripled in recent years, but remains low, according to the CDC. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative was established by the World Health Organization and UNICEF and is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The core of the initiative is the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, which measures a hospital’s breastfeeding support before, during, and after a mother’s hospital stay.

The report, “Vital Signs: Improvements in Maternity Care Policies and Practices That Support Breastfeeding — United States, 2007–2013,” examined data from CDC’s national survey, Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, which measures the percentage of U.S. hospitals with practices that are consistent with the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Findings showed that in 2013, 93% of hospitals provided high levels of: prenatal breastfeeding education, up from 91% in 2007. A majority of hospitals also taught mothers breastfeeding techniques – 92% in 2013 compared with 88% in 2007. Sixty-five percent of hospitals promoted early initiation of breastfeeding for mothers, up from 44% in 2007.

However, CDC leaders note that other findings demonstrate the need for improvement. For example, just over a quarter of hospitals surveyed had a model breastfeeding policy, commonly the foundation for many of the steps. Additionally, just 26% of hospitals ensured that only breast milk was given to healthy, breastfeeding infants who did not need infant formula for a medical reason in 2013. Only 45% of hospitals in 2013 kept mothers and babies together through their entire hospital stay, a practice which provides opportunities to breastfeed and helps mothers learn feeding cues, the report found. Just 32% of hospitals provided enough support for breastfeeding mothers when they left the hospital, including follow-up visits, phone calls, and referrals for additional support. These percentages were only slight increases from 2007, said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden during an Oct. 6 press conference.

“Every 1 of the 10 steps is important to use in the hospital to give babies the best start [and] to help mothers start and continue to breastfeed as recommended,” Dr. Frieden said. “I’d like to ask hospitals to keep making progress. Make a plan for what you can do right now that’s in line with the 10 steps, and phase that in over time. Ideally, we’d like every birth hospital in this country to adopt all of the 10 steps and become baby-friendly.”

Dr. Perrine acknowledged that hospitals are not without challenges in implementing the Ten Steps. Primary obstacles could be convincing hospital leadership to focus on the initiative, training staff, and confronting push-back from senior labor and delivery employees, Dr. Perrine said.

The CDC calls for more hospitals to implement the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and to work toward achieving baby-friendly status. Hospitals can also participate in CDC’s Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey and get an individualized report that shows how they compare with other hospitals. Additionally, hospitals should work with physicians, nurses, lactation care providers, and other organizations to develop networks that can provide clinic-based, at-home, or community breastfeeding support.

“Doctors can make a really big difference in encouraging and supporting women who choose to breastfeed,” Dr. Frieden said during the press conference. “And hospitals can play a critical role in those first few days of life which really do form the basis of the pattern of breastfeeding.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Hospital support for breastfeeding mothers has nearly doubled nationwide through a global initiative, but more work is needed to increase the number of baby-friendly hospitals, according to an Oct. 6 Vital Signs report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The report found the rate of U.S. hospitals using the World Health Organization’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding rose from 29% in 2007 to 54% in 2013.

“What happens in the hospital can determine whether a mom starts and continues to breastfeed, and we know that many moms – 60% – stop breastfeeding earlier than they’d like,” said CDC epidemiologist Cria Perrine, PhD, in a statement. “These improvements in hospital support for breastfeeding are promising, but we also want to see more hospitals fully supporting mothers who want to breastfeed. The Ten Steps help ensure that mothers get the best start with breastfeeding.”

Of the nearly 4 million babies born each year in the United States, 14% are born in “baby-friendly” hospitals, a number that has almost tripled in recent years, but remains low, according to the CDC. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative was established by the World Health Organization and UNICEF and is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The core of the initiative is the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, which measures a hospital’s breastfeeding support before, during, and after a mother’s hospital stay.

The report, “Vital Signs: Improvements in Maternity Care Policies and Practices That Support Breastfeeding — United States, 2007–2013,” examined data from CDC’s national survey, Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, which measures the percentage of U.S. hospitals with practices that are consistent with the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Findings showed that in 2013, 93% of hospitals provided high levels of: prenatal breastfeeding education, up from 91% in 2007. A majority of hospitals also taught mothers breastfeeding techniques – 92% in 2013 compared with 88% in 2007. Sixty-five percent of hospitals promoted early initiation of breastfeeding for mothers, up from 44% in 2007.

However, CDC leaders note that other findings demonstrate the need for improvement. For example, just over a quarter of hospitals surveyed had a model breastfeeding policy, commonly the foundation for many of the steps. Additionally, just 26% of hospitals ensured that only breast milk was given to healthy, breastfeeding infants who did not need infant formula for a medical reason in 2013. Only 45% of hospitals in 2013 kept mothers and babies together through their entire hospital stay, a practice which provides opportunities to breastfeed and helps mothers learn feeding cues, the report found. Just 32% of hospitals provided enough support for breastfeeding mothers when they left the hospital, including follow-up visits, phone calls, and referrals for additional support. These percentages were only slight increases from 2007, said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden during an Oct. 6 press conference.

“Every 1 of the 10 steps is important to use in the hospital to give babies the best start [and] to help mothers start and continue to breastfeed as recommended,” Dr. Frieden said. “I’d like to ask hospitals to keep making progress. Make a plan for what you can do right now that’s in line with the 10 steps, and phase that in over time. Ideally, we’d like every birth hospital in this country to adopt all of the 10 steps and become baby-friendly.”

Dr. Perrine acknowledged that hospitals are not without challenges in implementing the Ten Steps. Primary obstacles could be convincing hospital leadership to focus on the initiative, training staff, and confronting push-back from senior labor and delivery employees, Dr. Perrine said.

The CDC calls for more hospitals to implement the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and to work toward achieving baby-friendly status. Hospitals can also participate in CDC’s Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey and get an individualized report that shows how they compare with other hospitals. Additionally, hospitals should work with physicians, nurses, lactation care providers, and other organizations to develop networks that can provide clinic-based, at-home, or community breastfeeding support.

“Doctors can make a really big difference in encouraging and supporting women who choose to breastfeed,” Dr. Frieden said during the press conference. “And hospitals can play a critical role in those first few days of life which really do form the basis of the pattern of breastfeeding.”

On Twitter @legal_med

In utero exposure to tenofovir associated with lower BMC

The average bone mineral content (BMC) of infants of mothers who took tenofovir during pregnancy was 12.2% lower than was the average BMC of infants who were not exposed to the drug in utero, according to a controlled study.

The study’s participants were infants of mothers with HIV infections. The mothers enrolled in the study from April 2011 to June 2013, at 14 U.S. clinical sites. Late in pregnancy, 74 of the infants’ mothers had taken tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which when combined with other antiretroviral drugs, is the preferred initial therapy for adults with (HIV) infection. The study’s additional participants were 69 infants of mothers who had not taken tenofovir during gestation. Infants from both groups had their BMC measured within a month of their births. All of the infants were born no earlier than after a 36-week pregnancy, did not have HIV infection, and were singletons.

The average whole-body BMC (with head) of infants exposed to TDF in utero was 56.0 g, compared with 63.8 g for unexposed infants (P = .002). For whole-body less head BMC, the mean was 33.3 g in the TDF-exposed group, compared with 36.3 g in the unexposed group (P = .038), showing that for TDF-exposed infants, the average whole-body less head BMC was 8.3% smaller than was that of the unexposed infants.

According to the researchers’ adjusted linear regression model, for TDF-exposed infants, the mean whole-body BMC (with head) was 5.3 g lower (P = .013) in the TDF-exposed infants. For the mean whole-body less head BMC, the adjusted model showed that this measurement was 1.9 g lower in the TDF-exposed infants (P = .15).

“The present study provides strong evidence of a biologic effect of maternal TDF on infant bone. However, the lack of infant BMC reference standards makes it difficult to determine if the lower BMC in tenofovir-exposed infants is abnormal,” according to Dr. George K. Siberry and his colleagues.

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/civ437).

The average bone mineral content (BMC) of infants of mothers who took tenofovir during pregnancy was 12.2% lower than was the average BMC of infants who were not exposed to the drug in utero, according to a controlled study.

The study’s participants were infants of mothers with HIV infections. The mothers enrolled in the study from April 2011 to June 2013, at 14 U.S. clinical sites. Late in pregnancy, 74 of the infants’ mothers had taken tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which when combined with other antiretroviral drugs, is the preferred initial therapy for adults with (HIV) infection. The study’s additional participants were 69 infants of mothers who had not taken tenofovir during gestation. Infants from both groups had their BMC measured within a month of their births. All of the infants were born no earlier than after a 36-week pregnancy, did not have HIV infection, and were singletons.

The average whole-body BMC (with head) of infants exposed to TDF in utero was 56.0 g, compared with 63.8 g for unexposed infants (P = .002). For whole-body less head BMC, the mean was 33.3 g in the TDF-exposed group, compared with 36.3 g in the unexposed group (P = .038), showing that for TDF-exposed infants, the average whole-body less head BMC was 8.3% smaller than was that of the unexposed infants.

According to the researchers’ adjusted linear regression model, for TDF-exposed infants, the mean whole-body BMC (with head) was 5.3 g lower (P = .013) in the TDF-exposed infants. For the mean whole-body less head BMC, the adjusted model showed that this measurement was 1.9 g lower in the TDF-exposed infants (P = .15).

“The present study provides strong evidence of a biologic effect of maternal TDF on infant bone. However, the lack of infant BMC reference standards makes it difficult to determine if the lower BMC in tenofovir-exposed infants is abnormal,” according to Dr. George K. Siberry and his colleagues.

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/civ437).

The average bone mineral content (BMC) of infants of mothers who took tenofovir during pregnancy was 12.2% lower than was the average BMC of infants who were not exposed to the drug in utero, according to a controlled study.

The study’s participants were infants of mothers with HIV infections. The mothers enrolled in the study from April 2011 to June 2013, at 14 U.S. clinical sites. Late in pregnancy, 74 of the infants’ mothers had taken tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which when combined with other antiretroviral drugs, is the preferred initial therapy for adults with (HIV) infection. The study’s additional participants were 69 infants of mothers who had not taken tenofovir during gestation. Infants from both groups had their BMC measured within a month of their births. All of the infants were born no earlier than after a 36-week pregnancy, did not have HIV infection, and were singletons.

The average whole-body BMC (with head) of infants exposed to TDF in utero was 56.0 g, compared with 63.8 g for unexposed infants (P = .002). For whole-body less head BMC, the mean was 33.3 g in the TDF-exposed group, compared with 36.3 g in the unexposed group (P = .038), showing that for TDF-exposed infants, the average whole-body less head BMC was 8.3% smaller than was that of the unexposed infants.

According to the researchers’ adjusted linear regression model, for TDF-exposed infants, the mean whole-body BMC (with head) was 5.3 g lower (P = .013) in the TDF-exposed infants. For the mean whole-body less head BMC, the adjusted model showed that this measurement was 1.9 g lower in the TDF-exposed infants (P = .15).

“The present study provides strong evidence of a biologic effect of maternal TDF on infant bone. However, the lack of infant BMC reference standards makes it difficult to determine if the lower BMC in tenofovir-exposed infants is abnormal,” according to Dr. George K. Siberry and his colleagues.

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/civ437).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Does episiotomy at vacuum delivery increase maternal morbidity?

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

Should the 30-minute rule for emergent cesarean delivery be applied universally?

CASE 1: Term delivery: 45 minutes from decision to incision

P. G. is a 27-year-old woman (G2P1) at 38.2 weeks’ gestation who presents to the labor and delivery unit reporting painful contractions after uncomplicated prenatal care. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 40 kg/m2. Upon admission, her fetal heart-rate (FHR) tracing falls into Category 1. An examination reveals a cervix dilated to 4 cm and 70% effaced. Epidural analgesia is administered for pain control.

After 4 hours, the FHR tracing reveals minimal variability with occasional variable decelerations. The obstetrician is informed but issues no specific instructions. After 2 more hours, the FHR tracing lacks variability, with late decelerations and no spontaneous accelerations—a Category 3 tracing, which is predictive of abnormal acid-base status. Contractions occur every 3 to 4 minutes.

When fetal scalp stimulation by the nurse fails to elicit any accelerations, intrauterine resuscitation is attempted with an intravenous fluid bolus, left lateral positioning, and oxygen administration. Despite these measures, the FHR pattern fails to improve.

Although she is apprised of the need for prompt delivery, the patient hopes to avoid cesarean delivery, if possible, and insists on more time before a decision is made to proceed to cesarean. After another 2 hours, the FHR pattern has not improved and cervical dilation remains at 4 cm. The patient gives her consent for cesarean delivery.

Approximately 35 minutes are needed to take the patient to the operating room (OR). About 45 minutes after informed consent, the incision is made. Forty-seven minutes later, a male infant is delivered with Apgar scores of 1, 3, and 4 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Umbilical arterial analysis reveals a pH level of 6.9, with a base excess of –21. The infant has a neonatal seizure within 3 hours and is eventually diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

A claim against the clinicians alleges that deviation from the “standard of care 30-minute rule more than likely caused” hypoxic ische- mic injury and cerebral palsy.

Does the literature support this claim?

Approximately 3% of all births involve cesarean delivery for a nonreassuring FHR tracing.1 Much has been written about the “30-minute rule” for decision to incision time. In this article, we highlight current limitations of this standard in the context of 4 distinct clinical scenarios.

Case 1 highlights several limitations and ambiguities in the obstetric literature. Although a timely delivery is always desirable, it may not always be possible to achieve safely due to intrinsic patient characteristics or situational constraints. Conditions prevailing before the decision to proceed to cesarean delivery also affect overall pregnancy outcomes. Not all cases have the same starting point; fetal status at the time of the cesarean decision also determines the acuity and urgency of the case.

A widely promulgated rule— but is it valid?

Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists have published guidelines stating that any hospital offering obstetric care should have the capability to perform emergent cesarean delivery within 30 minutes.2,3 This general statement has been touted as the standard by which obstetric services should be evaluated. Regardless of the clinical situation, obstetric providers are expected to abide by this rule.

These guidelines recently have come under scrutiny. For example, a 2014 meta-analysis involving more than 30 studies and 22,000 women revealed that only 36% of all cases with a Category 2 FHR tracing were delivered within 30 minutes.4 Interestingly, investigators reported that infants with a shorter delivery interval had a higher likelihood of having a 5-minute Apgar score below 7 and an umbilical artery pH level below 7.1, with no difference in the rate of admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) when the time from decision to delivery was examined.4 This finding highlights the questionable nature of the current clinical standard, as well as the conflicting findings currently present in the literature.

In general, patients who have graver clinical findings will be delivered at a shorter interval but may still have worse neonatal outcomes than infants delivered 30 minutes or more after the decision for cesarean is made.

Although Case 1 is complicated by FHR abnormalities, the association between such abnormalities and adverse long-term outcomes in neonates is questionable. Fewer than 1% of cases involving late decelerations or decreased variability during labor lead to cerebral palsy,5 highlighting the weak association between FHR abnormalities and neurologic sequelae. Most adverse neurologic neonatal outcomes are multifactorial in nature and may not be attributable to a single prenatal event.

With such limitations, the application and use of the 30-minute “standard” by hospitals, professional societies, and the medicolegal community may not be appropriate. The literature may not justify using this arbitrary rule as the standard of care. Clearly, there are gaps in our knowledge and understanding of FHR abnormalities and the optimal interval for cesarean delivery. Therefore, it may be unfair and inappropriate to group all cases and clinical situations together.

CASE 2: 25 minutes from decision to preterm delivery

J. P. (G2P1) undergoes an ultrasonographic examination at 33.4 weeks’ gestation because of concern about a discrepancy between fetal size and gestational age. The estimated fetal weight is in the 5th percentile. Amniotic fluid level is normal, but the biophysical profile is 6/8, with no breathing for 30 seconds. Umbilical artery Doppler imaging reveals absent end-diastolic flow, and FHR monitoring reveals repetitive late decelerations.

The patient is admitted immediately to the labor and delivery unit and placed on continuous electronic fetal monitoring. Betamethasone is given to enhance fetal lung maturity. FHR monitoring continues to show repetitive late decelerations with every contraction.

After 10 minutes on the labor floor, a decision is made to proceed to emergent cesarean delivery. Within 25 minutes of that decision, a female infant weighing 1,731 g (3rd percentile) is delivered, with Apgar scores of 1, 1, and 4 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. The infant is eventually diagnosed with moderate cerebral palsy.

Could this outcome have been prevented?

Published reports on the association between abnormal FHR patterns and adverse perinatal outcomes in preterm infants are even more scarce than they are for infants delivered at term. Case 2 highlights the fact that achievement of a 30-minute interval from decision to delivery doesn’t necessarily eliminate the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes and long-term morbidity.

One of the best evaluations of this association was published by Shy and colleagues in the 1980s.6 In that study, investigators randomly assigned 173 preterm infants to intermittent auscultation or continuous external fetal monitoring. Use of external fetal monitoring did not improve neurologic outcomes at 18 months of age. Nor did the duration of FHR abnormalities predict the development of cerebral palsy.6

A recent secondary analysis from a randomized trial evaluating the use of antenatal magnesium sulfate to prevent cerebral palsy revealed that preterm FHR patterns labeled as “fetal distress” by the treating physician were associated with an increased risk of cerebral palsy in the newborn.7 Although this analysis revealed an association, a causal link could not be established. Damage to a preterm infant’s central nervous system can occur before the mother presents to the ultrasound unit or clinic, and alterations to FHR patterns can reflect previous injury. In such cases, a short decision to incision interval would not prevent damage to the central nervous system of the preterm infant.

CASE 3: 5 minutes from decision to incision after uterine rupture

G. P. is a patient (G2P1) at 38 weeks’ gestation who has had a previous low uterine transverse cesarean delivery. She strongly wishes to attempt vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and has been extensively counseled about the risks and benefits of this approach. This counseling has been appropriately documented in her chart. Her predicted likelihood of success is 54%.

Upon arrival in the triage unit, she reiterates that she hopes to deliver her child vaginally. Upon examination, she is found to be dilated to 4 cm. She is admitted to the labor and delivery unit, with reevaluation planned 2 hours after epidural administration. At that time, her labor is noted to be progressing at an appropriate rate.

After 5 hours of labor, the baseline FHR drops into the 70s. Immediate evaluation reveals significant uterine bleeding, with the fetus no longer engaged in the pelvis. The attending physician immediately suspects uterine rupture.

The patient is rushed to the OR, and delivery is complicated by the presence of extensive adhesions to the uterus and anterior abdominal wall. After 20 minutes, a female infant is delivered, with Apgar scores of 0, 0, and 1 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Medical care is withdrawn after 3 days in the NICU.

In a true obstetric catastrophe such as uterine rupture, should the decision to incision interval be 30 minutes?

Although it is rare, uterine rupture is a known complication of VBAC attempts. The actual rate varies across the literature but appears to be approximately 0.5% to 0.9% in women attempting vaginal birth after a prior lower uterine incision.8

If uterine rupture develops, both mother and fetus are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality. The risk of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy after uterine rupture is about 6.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–10.6), and the risk of neonatal death is about 1.8% (95% CI, 0–4.2).9 Uterine rupture also has been linked to an increase in:

- severe postpartum hemorrhage (odds ratio [OR], 8.51; 95% CI, 4.6–15.1)

- general anesthesia exposure (OR, 14.20; 95% CI, 9.1–22.2)

- hysterectomy (OR, 51.36; 95% CI, 13.6–193.4)

- serious perinatal outcome (OR, 24.51; 95% CI, 11.9–51.9).10

- serious perinatal outcome (OR, 24.51; 95% CI, 11.9–51.9).

Case 3 again highlights the limitations and difficulties of encompassing all cases within a 30-minute timeframe. Although the newborn was delivered within this interval after the initial insult, the intervention was insufficient to prevent severe and long-term damage.

In cases of true obstetric emergency, the catastrophic nature of the event may lead to adverse long-term neonatal outcomes even if the standard of care is met. Immediate delivery still may not allow for the prevention of neurologic morbidity in the fetus. When evaluating such cases retrospectively, all parties involved always should consider these facts before drawing any conclusions on causality and prevention.

CASE 4: Twins delivered 20 minutes after cesarean decision

P. R. (G1P0) presents for routine prenatal care at 36 weeks’ gestation. She is carrying a dichorionic/diamniotic twin gestation that so far has been uncomplicated. She has been experiencing contractions for the past 2 weeks, but they have intensified during the past 2 days. When an examination reveals that she is dilated to 4 cm, she is admitted to the labor and delivery unit.

Both fetuses are evaluated via external FHR monitoring. Initially, both have Category 1 tracings but, approximately 1 hour later, both tracings are noted to have minimal variability with variable decelerations, with a nadir at 80 bpm that lasts 30 to 45 seconds. These abnormalities persist even after intrauterine resuscitation is attempted. The cervix remains dilated at 4 cm.

After a Category 2 tracing persists for 1 hour, the attending physician proceeds to cesarean delivery. Both infants are delivered within 20 minutes after the decision is made. Two female infants of appropriate gestational size are delivered, with Apgar scores of 7 and 8 for Twin A and 8 and 9 for Twin B. The newborns eventually are discharged home with the mother. Twin B is subsequently given a diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

Should the decision to incision rule be applied to twin gestations?

Multifetal gestations carry an increased risk not only of fetal and neonatal death but also of handicap among survivors, compared with singleton pregnancies.11 The literature evaluating the link between abnormal FHR patterns and adverse neonatal outcomes in twin pregnancies is sparse. Adding to the confusion is the fact that signal loss from fetal monitoring during labor occurs more frequently in twins than in singletons, with a reported incidence of 26% to 33% during the 1st stage of labor and 41% to 63% during the 2nd stage.12 Moreover, the FHR pattern of one twin may be recorded twice inadvertently and the same tracing erroneously attributed to both twins.

The decision to incision and delivery time in twin gestations should be evaluated in the context of all the limitations the clinician faces when managing labor in a twin gestation. The 30-minute rule never has been specifically evaluated in the context of multifetal gestations. The pathway and contributing factors that lead to adverse neonatal outcomes in twin gestations may be very different from those related to singleton pregnancies and may be more relevant to antepartum than intrapartum events.

Take-home message

The 4 cases presented here call into question the applicability and generalizability of the 30-minute decision to incision rule. Diverse clinical situations encountered in practice should lead to different interpretations of this standard. No single rule can encompass all possible scenarios; therefore, a single rule should not be touted as universal. All clinical variables should be weighed and interpreted in the retrospective evaluation of a case involving a cesarean delivery performed after a 30-minute decision to incision interval.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Scott JR, Scardo JA, Hendrix NW, Martin JN Jr. Cesarean delivery for fetal distress: rate and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58(5):337–350.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Professional Standards. Standards for Obstetric-Gynecologic Hospital Services. 7th ed. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1989.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Caesarean Section Guideline. London, UK: NICE; 2011.

- Tolcher MC, Johnson RL, El-Nashar SA, West CP. Decision-to-incision time and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):536–548.

- Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, Grether JK. Uncertain values of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(10):613–618.

- Shy KK, Luthy DA, Bennett FC, et al. Effects of electronic fetal heart-rate monitoring, as compared with periodic auscultation, on the neurologic development of premature infants. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(9):588–593.

- Mendez-Figueroa H, Chauhan SP, Pedroza C, Refuerzo JS, Dahlke JD, Rouse DJ. Preterm cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate: neonatal and neurologic morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):636–642.

- Macones GA, Cahill AG, Samilio DM, Odibo A, Peipert J, Stevens EJ. Can uterine rupture in patients attempting vaginal birth after cesarean delivery be predicted? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):1148–1152.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2581–2589.

- Al-Zirqi I, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsen L, Daltveit AK, Vangen S. Uterine rupture: trends over 40 years [published online ahead of print April 2, 2015]. BJOG. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13394.

- Ramsey PS, Repke JT. Intrapartum management of multifetal pregnancies. Semin Perinatol. 2003;27(1):54–72.

- Bakker PC, Colenbrander GJ, Verstraeten AA, Van Geijn HP. Quality of intrapartum cardiotocography in twin deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):2114–2119.

CASE 1: Term delivery: 45 minutes from decision to incision

P. G. is a 27-year-old woman (G2P1) at 38.2 weeks’ gestation who presents to the labor and delivery unit reporting painful contractions after uncomplicated prenatal care. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 40 kg/m2. Upon admission, her fetal heart-rate (FHR) tracing falls into Category 1. An examination reveals a cervix dilated to 4 cm and 70% effaced. Epidural analgesia is administered for pain control.

After 4 hours, the FHR tracing reveals minimal variability with occasional variable decelerations. The obstetrician is informed but issues no specific instructions. After 2 more hours, the FHR tracing lacks variability, with late decelerations and no spontaneous accelerations—a Category 3 tracing, which is predictive of abnormal acid-base status. Contractions occur every 3 to 4 minutes.

When fetal scalp stimulation by the nurse fails to elicit any accelerations, intrauterine resuscitation is attempted with an intravenous fluid bolus, left lateral positioning, and oxygen administration. Despite these measures, the FHR pattern fails to improve.

Although she is apprised of the need for prompt delivery, the patient hopes to avoid cesarean delivery, if possible, and insists on more time before a decision is made to proceed to cesarean. After another 2 hours, the FHR pattern has not improved and cervical dilation remains at 4 cm. The patient gives her consent for cesarean delivery.

Approximately 35 minutes are needed to take the patient to the operating room (OR). About 45 minutes after informed consent, the incision is made. Forty-seven minutes later, a male infant is delivered with Apgar scores of 1, 3, and 4 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Umbilical arterial analysis reveals a pH level of 6.9, with a base excess of –21. The infant has a neonatal seizure within 3 hours and is eventually diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

A claim against the clinicians alleges that deviation from the “standard of care 30-minute rule more than likely caused” hypoxic ische- mic injury and cerebral palsy.

Does the literature support this claim?

Approximately 3% of all births involve cesarean delivery for a nonreassuring FHR tracing.1 Much has been written about the “30-minute rule” for decision to incision time. In this article, we highlight current limitations of this standard in the context of 4 distinct clinical scenarios.

Case 1 highlights several limitations and ambiguities in the obstetric literature. Although a timely delivery is always desirable, it may not always be possible to achieve safely due to intrinsic patient characteristics or situational constraints. Conditions prevailing before the decision to proceed to cesarean delivery also affect overall pregnancy outcomes. Not all cases have the same starting point; fetal status at the time of the cesarean decision also determines the acuity and urgency of the case.

A widely promulgated rule— but is it valid?

Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists have published guidelines stating that any hospital offering obstetric care should have the capability to perform emergent cesarean delivery within 30 minutes.2,3 This general statement has been touted as the standard by which obstetric services should be evaluated. Regardless of the clinical situation, obstetric providers are expected to abide by this rule.

These guidelines recently have come under scrutiny. For example, a 2014 meta-analysis involving more than 30 studies and 22,000 women revealed that only 36% of all cases with a Category 2 FHR tracing were delivered within 30 minutes.4 Interestingly, investigators reported that infants with a shorter delivery interval had a higher likelihood of having a 5-minute Apgar score below 7 and an umbilical artery pH level below 7.1, with no difference in the rate of admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) when the time from decision to delivery was examined.4 This finding highlights the questionable nature of the current clinical standard, as well as the conflicting findings currently present in the literature.

In general, patients who have graver clinical findings will be delivered at a shorter interval but may still have worse neonatal outcomes than infants delivered 30 minutes or more after the decision for cesarean is made.

Although Case 1 is complicated by FHR abnormalities, the association between such abnormalities and adverse long-term outcomes in neonates is questionable. Fewer than 1% of cases involving late decelerations or decreased variability during labor lead to cerebral palsy,5 highlighting the weak association between FHR abnormalities and neurologic sequelae. Most adverse neurologic neonatal outcomes are multifactorial in nature and may not be attributable to a single prenatal event.

With such limitations, the application and use of the 30-minute “standard” by hospitals, professional societies, and the medicolegal community may not be appropriate. The literature may not justify using this arbitrary rule as the standard of care. Clearly, there are gaps in our knowledge and understanding of FHR abnormalities and the optimal interval for cesarean delivery. Therefore, it may be unfair and inappropriate to group all cases and clinical situations together.

CASE 2: 25 minutes from decision to preterm delivery

J. P. (G2P1) undergoes an ultrasonographic examination at 33.4 weeks’ gestation because of concern about a discrepancy between fetal size and gestational age. The estimated fetal weight is in the 5th percentile. Amniotic fluid level is normal, but the biophysical profile is 6/8, with no breathing for 30 seconds. Umbilical artery Doppler imaging reveals absent end-diastolic flow, and FHR monitoring reveals repetitive late decelerations.

The patient is admitted immediately to the labor and delivery unit and placed on continuous electronic fetal monitoring. Betamethasone is given to enhance fetal lung maturity. FHR monitoring continues to show repetitive late decelerations with every contraction.

After 10 minutes on the labor floor, a decision is made to proceed to emergent cesarean delivery. Within 25 minutes of that decision, a female infant weighing 1,731 g (3rd percentile) is delivered, with Apgar scores of 1, 1, and 4 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. The infant is eventually diagnosed with moderate cerebral palsy.

Could this outcome have been prevented?

Published reports on the association between abnormal FHR patterns and adverse perinatal outcomes in preterm infants are even more scarce than they are for infants delivered at term. Case 2 highlights the fact that achievement of a 30-minute interval from decision to delivery doesn’t necessarily eliminate the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes and long-term morbidity.

One of the best evaluations of this association was published by Shy and colleagues in the 1980s.6 In that study, investigators randomly assigned 173 preterm infants to intermittent auscultation or continuous external fetal monitoring. Use of external fetal monitoring did not improve neurologic outcomes at 18 months of age. Nor did the duration of FHR abnormalities predict the development of cerebral palsy.6

A recent secondary analysis from a randomized trial evaluating the use of antenatal magnesium sulfate to prevent cerebral palsy revealed that preterm FHR patterns labeled as “fetal distress” by the treating physician were associated with an increased risk of cerebral palsy in the newborn.7 Although this analysis revealed an association, a causal link could not be established. Damage to a preterm infant’s central nervous system can occur before the mother presents to the ultrasound unit or clinic, and alterations to FHR patterns can reflect previous injury. In such cases, a short decision to incision interval would not prevent damage to the central nervous system of the preterm infant.

CASE 3: 5 minutes from decision to incision after uterine rupture