User login

Supreme Court appears ready to overturn Roe

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

Review of new drugs that may be used during pregnancy

In 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved 50 new drugs, but 24 will not be described here because they would probably not be used in pregnancy. The 24 are Aduhelm (aducanumab) to treat Alzheimer’s disease; Azstarys (serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate), a combination CNS stimulant indicated for the treatment of ADHD; Cabenuva (cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to treat HIV; Voxzogo (vosoritide) for children with achondroplasia and open epiphyses; Qelbree (viloxazine) used in children aged 6-17 years to treat ADHD; and Pylarify (piflufolastat) for prostate cancer. Other anticancer drugs that will not be covered are Cosela (trilaciclib), Cytalux (pafolacianine), Exkivity (mobocertinib); Fotivda (tivozanib), Jemperli (dostarlimab-gxly), Lumakras (sotorasib), Pepaxto (melphalan flufenamide), Rybrevant (amivantamab-vmjw), Rylaze (asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi), Scemblix (asciminib), Tepmetko (tepotinib), Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv), Truseltiq (infigratinib), Ukoniq (umbralisib), and Zynlonta (loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl).

Skytrofa (lonapegsomatropin-tcgd) will not be described below because it is indicated to treat short stature and is unlikely to be used in pregnancy. Nextstellis (drospirenone and estetrol) is used to prevent pregnancy.

Typically, for new drugs there will be no published reports describing their use in pregnant women. That information will come much later. In the sections below, the indications, effects on pregnant animals, and the potential for harm of a fetus/embryo are described. However, the relevance of animal data to human pregnancies is not great.

Adbry (tralokinumab) (molecular weight [MW], 147 kilodaltons), is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. The drug did not harm fetal monkeys at doses that were 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.

Besremi (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft) (MW, 60 kDa) is an interferon alfa-2b indicated for the treatment of adults with polycythemia vera. It is given by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. Animal studies assessing reproductive toxicity have not been conducted. The manufacturer states that the drug may cause fetal harm and should be assumed to have abortifacient potential.

Brexafemme (ibrexafungerp) (MW, 922) is indicated for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not in pregnant rats. The manufacturer recommends females with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 4 days after the final dose.

Bylvay (odevixibat) (MW unknown) is indicated for the treatment of pruritus in patients aged 3 months and older. There are no human data regarding its use in pregnant women. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits. Although there are no data, the drug has low absorption following oral administration and breastfeeding is not expected to result in exposure of the infant.

Empaveli (pegcetacoplan) (MW, 44 kDa) is used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. When the drug was given to pregnant cynomolgus monkeys there was an increase in abortions and stillbirths.

Evkeeza (evinacumab-dgnb) (MW, 146k) is used to treat homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. The drug was teratogenic in rabbits but not rats.

Fexinidazole (MW not specified) is indicated to treat human African trypanosomiasis caused by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Additional information not available.

Kerendia (finerenone) (MW, 378), is indicated to reduce the risk of kidney and heart complications in chronic kidney disease associated with type 2 diabetes. The drug was teratogenic in rats.

Korsuva (difelikefalin) (MW, 679) is a kappa opioid–receptor agonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease in adults undergoing hemodialysis. No adverse effects were observed in pregnant rats and rabbits. The limited human data on use of Korsuva in pregnant women are not sufficient to evaluate a drug associated risk for major birth defects or miscarriage.

Leqvio (inclisiran) (MW, 17,285) is indicated to treat heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as an add-on therapy. The drug was not teratogenic in rats and rabbits.

Livmarli (maralixibat) (MW, 710) is indicated for the treatment of cholestatic pruritus associated with Alagille syndrome. Because systemic absorption is low, the recommended clinical dose is not expected to result in measurable fetal exposure. No effects on fetal rats were observed.

Livtencity (maribavir) (MW, 376) is used to treat posttransplant cytomegalovirus infection that has not responded to other treatment. Embryo/fetal survival was reduced in rats but not in rabbits at doses less then the human dose.

Lupkynis (voclosporin) (MW, 1,215) is used to treat nephritis. Avoid use of Lupkynis in pregnant women because of the alcohol content of the drug formulation. The drug was embryocidal and feticidal in rats and rabbits but with no treatment-related fetal malformations or variations.

Lybalvi (olanzapine and samidorphan) (MW, 312 and 505) is a combination drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It was fetal toxic in pregnant rats and rabbits but with no evidence of malformations. There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to atypical antipsychotics, including this drug, during pregnancy. Health care providers are encouraged to register patients by contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visit the Reproductive Psychiatry Resource and Information Center of the MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health.

Nexviazyme (avalglucosidase alfa-ngpt) (MW, 124k) is a hydrolytic lysosomal glycogen-specific enzyme indicated for the treatment of patients aged 1 year and older with late-onset Pompe disease. The drug was not teratogenic in mice and rabbits.

Nulibry (fosdenopterin) (MW, 480) is used to reduce the risk of mortality in molybdenum cofactor deficiency type A. Studies have not been conducted in pregnant animals.

Ponvory (ponesimod) (MW, 461) is used to treat relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. The drug caused severe adverse effects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Qulipta (atogepant) (MW, 604) is indicated to prevent episodic migraines. It is embryo/fetal toxic in rats and rabbits.

Saphnelo (anifrolumab-fnia) (MW, 148k) is used to treat moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus along with standard therapy. In pregnant cynomolgus monkeys, there was no evidence of embryotoxicity or fetal malformations with exposures up to approximately 28 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

Tavneos (avacopan) (MW, 582) is indicated to treat severe active antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated vasculitis in combination with standard therapy including glucocorticoids. There appears to be an increased risk for hepatotoxicity. The drug caused no defects in hamsters and rabbits, but in rabbits there was an increase in abortions.

Tezspire (tezepelumab-ekko) (MW, 147k) is indicated to treat severe asthma as an add-on maintenance therapy. No adverse fetal effects were observed in pregnant cynomolgus monkeys.

Verquvo (vericiguat) (MW, 426) is used to mitigate the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for chronic heart failure. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not rats.

Vyvgart (efgartigimod alfa-fcab) (MW, 54k) is indicated to treat generalized myasthenia gravis. The drug did not cause birth defects in rats and rabbits.

Welireg (belzutifan) (MW, 383) is used to treat von Hippel–Lindau disease. In pregnant rats, the drug caused embryo-fetal lethality, reduced fetal body weight, and caused fetal skeletal malformations at maternal exposures of at least 0.2 times the human exposures.

Zegalogue (dasiglucagon) (MW, 3,382) is used to treat severe hypoglycemia. The drug did not cause birth defects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Breastfeeding

It is not known if the above drugs will be in breast milk, but the safest course for an infant is to not breast feed if the mother is taking any of the above drugs.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved 50 new drugs, but 24 will not be described here because they would probably not be used in pregnancy. The 24 are Aduhelm (aducanumab) to treat Alzheimer’s disease; Azstarys (serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate), a combination CNS stimulant indicated for the treatment of ADHD; Cabenuva (cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to treat HIV; Voxzogo (vosoritide) for children with achondroplasia and open epiphyses; Qelbree (viloxazine) used in children aged 6-17 years to treat ADHD; and Pylarify (piflufolastat) for prostate cancer. Other anticancer drugs that will not be covered are Cosela (trilaciclib), Cytalux (pafolacianine), Exkivity (mobocertinib); Fotivda (tivozanib), Jemperli (dostarlimab-gxly), Lumakras (sotorasib), Pepaxto (melphalan flufenamide), Rybrevant (amivantamab-vmjw), Rylaze (asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi), Scemblix (asciminib), Tepmetko (tepotinib), Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv), Truseltiq (infigratinib), Ukoniq (umbralisib), and Zynlonta (loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl).

Skytrofa (lonapegsomatropin-tcgd) will not be described below because it is indicated to treat short stature and is unlikely to be used in pregnancy. Nextstellis (drospirenone and estetrol) is used to prevent pregnancy.

Typically, for new drugs there will be no published reports describing their use in pregnant women. That information will come much later. In the sections below, the indications, effects on pregnant animals, and the potential for harm of a fetus/embryo are described. However, the relevance of animal data to human pregnancies is not great.

Adbry (tralokinumab) (molecular weight [MW], 147 kilodaltons), is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. The drug did not harm fetal monkeys at doses that were 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.

Besremi (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft) (MW, 60 kDa) is an interferon alfa-2b indicated for the treatment of adults with polycythemia vera. It is given by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. Animal studies assessing reproductive toxicity have not been conducted. The manufacturer states that the drug may cause fetal harm and should be assumed to have abortifacient potential.

Brexafemme (ibrexafungerp) (MW, 922) is indicated for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not in pregnant rats. The manufacturer recommends females with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 4 days after the final dose.

Bylvay (odevixibat) (MW unknown) is indicated for the treatment of pruritus in patients aged 3 months and older. There are no human data regarding its use in pregnant women. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits. Although there are no data, the drug has low absorption following oral administration and breastfeeding is not expected to result in exposure of the infant.

Empaveli (pegcetacoplan) (MW, 44 kDa) is used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. When the drug was given to pregnant cynomolgus monkeys there was an increase in abortions and stillbirths.

Evkeeza (evinacumab-dgnb) (MW, 146k) is used to treat homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. The drug was teratogenic in rabbits but not rats.

Fexinidazole (MW not specified) is indicated to treat human African trypanosomiasis caused by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Additional information not available.

Kerendia (finerenone) (MW, 378), is indicated to reduce the risk of kidney and heart complications in chronic kidney disease associated with type 2 diabetes. The drug was teratogenic in rats.

Korsuva (difelikefalin) (MW, 679) is a kappa opioid–receptor agonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease in adults undergoing hemodialysis. No adverse effects were observed in pregnant rats and rabbits. The limited human data on use of Korsuva in pregnant women are not sufficient to evaluate a drug associated risk for major birth defects or miscarriage.

Leqvio (inclisiran) (MW, 17,285) is indicated to treat heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as an add-on therapy. The drug was not teratogenic in rats and rabbits.

Livmarli (maralixibat) (MW, 710) is indicated for the treatment of cholestatic pruritus associated with Alagille syndrome. Because systemic absorption is low, the recommended clinical dose is not expected to result in measurable fetal exposure. No effects on fetal rats were observed.

Livtencity (maribavir) (MW, 376) is used to treat posttransplant cytomegalovirus infection that has not responded to other treatment. Embryo/fetal survival was reduced in rats but not in rabbits at doses less then the human dose.

Lupkynis (voclosporin) (MW, 1,215) is used to treat nephritis. Avoid use of Lupkynis in pregnant women because of the alcohol content of the drug formulation. The drug was embryocidal and feticidal in rats and rabbits but with no treatment-related fetal malformations or variations.

Lybalvi (olanzapine and samidorphan) (MW, 312 and 505) is a combination drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It was fetal toxic in pregnant rats and rabbits but with no evidence of malformations. There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to atypical antipsychotics, including this drug, during pregnancy. Health care providers are encouraged to register patients by contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visit the Reproductive Psychiatry Resource and Information Center of the MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health.

Nexviazyme (avalglucosidase alfa-ngpt) (MW, 124k) is a hydrolytic lysosomal glycogen-specific enzyme indicated for the treatment of patients aged 1 year and older with late-onset Pompe disease. The drug was not teratogenic in mice and rabbits.

Nulibry (fosdenopterin) (MW, 480) is used to reduce the risk of mortality in molybdenum cofactor deficiency type A. Studies have not been conducted in pregnant animals.

Ponvory (ponesimod) (MW, 461) is used to treat relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. The drug caused severe adverse effects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Qulipta (atogepant) (MW, 604) is indicated to prevent episodic migraines. It is embryo/fetal toxic in rats and rabbits.

Saphnelo (anifrolumab-fnia) (MW, 148k) is used to treat moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus along with standard therapy. In pregnant cynomolgus monkeys, there was no evidence of embryotoxicity or fetal malformations with exposures up to approximately 28 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

Tavneos (avacopan) (MW, 582) is indicated to treat severe active antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated vasculitis in combination with standard therapy including glucocorticoids. There appears to be an increased risk for hepatotoxicity. The drug caused no defects in hamsters and rabbits, but in rabbits there was an increase in abortions.

Tezspire (tezepelumab-ekko) (MW, 147k) is indicated to treat severe asthma as an add-on maintenance therapy. No adverse fetal effects were observed in pregnant cynomolgus monkeys.

Verquvo (vericiguat) (MW, 426) is used to mitigate the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for chronic heart failure. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not rats.

Vyvgart (efgartigimod alfa-fcab) (MW, 54k) is indicated to treat generalized myasthenia gravis. The drug did not cause birth defects in rats and rabbits.

Welireg (belzutifan) (MW, 383) is used to treat von Hippel–Lindau disease. In pregnant rats, the drug caused embryo-fetal lethality, reduced fetal body weight, and caused fetal skeletal malformations at maternal exposures of at least 0.2 times the human exposures.

Zegalogue (dasiglucagon) (MW, 3,382) is used to treat severe hypoglycemia. The drug did not cause birth defects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Breastfeeding

It is not known if the above drugs will be in breast milk, but the safest course for an infant is to not breast feed if the mother is taking any of the above drugs.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved 50 new drugs, but 24 will not be described here because they would probably not be used in pregnancy. The 24 are Aduhelm (aducanumab) to treat Alzheimer’s disease; Azstarys (serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate), a combination CNS stimulant indicated for the treatment of ADHD; Cabenuva (cabotegravir and rilpivirine) to treat HIV; Voxzogo (vosoritide) for children with achondroplasia and open epiphyses; Qelbree (viloxazine) used in children aged 6-17 years to treat ADHD; and Pylarify (piflufolastat) for prostate cancer. Other anticancer drugs that will not be covered are Cosela (trilaciclib), Cytalux (pafolacianine), Exkivity (mobocertinib); Fotivda (tivozanib), Jemperli (dostarlimab-gxly), Lumakras (sotorasib), Pepaxto (melphalan flufenamide), Rybrevant (amivantamab-vmjw), Rylaze (asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi), Scemblix (asciminib), Tepmetko (tepotinib), Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv), Truseltiq (infigratinib), Ukoniq (umbralisib), and Zynlonta (loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl).

Skytrofa (lonapegsomatropin-tcgd) will not be described below because it is indicated to treat short stature and is unlikely to be used in pregnancy. Nextstellis (drospirenone and estetrol) is used to prevent pregnancy.

Typically, for new drugs there will be no published reports describing their use in pregnant women. That information will come much later. In the sections below, the indications, effects on pregnant animals, and the potential for harm of a fetus/embryo are described. However, the relevance of animal data to human pregnancies is not great.

Adbry (tralokinumab) (molecular weight [MW], 147 kilodaltons), is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. The drug did not harm fetal monkeys at doses that were 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.

Besremi (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft) (MW, 60 kDa) is an interferon alfa-2b indicated for the treatment of adults with polycythemia vera. It is given by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. Animal studies assessing reproductive toxicity have not been conducted. The manufacturer states that the drug may cause fetal harm and should be assumed to have abortifacient potential.

Brexafemme (ibrexafungerp) (MW, 922) is indicated for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not in pregnant rats. The manufacturer recommends females with reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 4 days after the final dose.

Bylvay (odevixibat) (MW unknown) is indicated for the treatment of pruritus in patients aged 3 months and older. There are no human data regarding its use in pregnant women. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits. Although there are no data, the drug has low absorption following oral administration and breastfeeding is not expected to result in exposure of the infant.

Empaveli (pegcetacoplan) (MW, 44 kDa) is used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. When the drug was given to pregnant cynomolgus monkeys there was an increase in abortions and stillbirths.

Evkeeza (evinacumab-dgnb) (MW, 146k) is used to treat homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. The drug was teratogenic in rabbits but not rats.

Fexinidazole (MW not specified) is indicated to treat human African trypanosomiasis caused by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Additional information not available.

Kerendia (finerenone) (MW, 378), is indicated to reduce the risk of kidney and heart complications in chronic kidney disease associated with type 2 diabetes. The drug was teratogenic in rats.

Korsuva (difelikefalin) (MW, 679) is a kappa opioid–receptor agonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pruritus associated with chronic kidney disease in adults undergoing hemodialysis. No adverse effects were observed in pregnant rats and rabbits. The limited human data on use of Korsuva in pregnant women are not sufficient to evaluate a drug associated risk for major birth defects or miscarriage.

Leqvio (inclisiran) (MW, 17,285) is indicated to treat heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as an add-on therapy. The drug was not teratogenic in rats and rabbits.

Livmarli (maralixibat) (MW, 710) is indicated for the treatment of cholestatic pruritus associated with Alagille syndrome. Because systemic absorption is low, the recommended clinical dose is not expected to result in measurable fetal exposure. No effects on fetal rats were observed.

Livtencity (maribavir) (MW, 376) is used to treat posttransplant cytomegalovirus infection that has not responded to other treatment. Embryo/fetal survival was reduced in rats but not in rabbits at doses less then the human dose.

Lupkynis (voclosporin) (MW, 1,215) is used to treat nephritis. Avoid use of Lupkynis in pregnant women because of the alcohol content of the drug formulation. The drug was embryocidal and feticidal in rats and rabbits but with no treatment-related fetal malformations or variations.

Lybalvi (olanzapine and samidorphan) (MW, 312 and 505) is a combination drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It was fetal toxic in pregnant rats and rabbits but with no evidence of malformations. There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to atypical antipsychotics, including this drug, during pregnancy. Health care providers are encouraged to register patients by contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visit the Reproductive Psychiatry Resource and Information Center of the MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health.

Nexviazyme (avalglucosidase alfa-ngpt) (MW, 124k) is a hydrolytic lysosomal glycogen-specific enzyme indicated for the treatment of patients aged 1 year and older with late-onset Pompe disease. The drug was not teratogenic in mice and rabbits.

Nulibry (fosdenopterin) (MW, 480) is used to reduce the risk of mortality in molybdenum cofactor deficiency type A. Studies have not been conducted in pregnant animals.

Ponvory (ponesimod) (MW, 461) is used to treat relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. The drug caused severe adverse effects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Qulipta (atogepant) (MW, 604) is indicated to prevent episodic migraines. It is embryo/fetal toxic in rats and rabbits.

Saphnelo (anifrolumab-fnia) (MW, 148k) is used to treat moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus along with standard therapy. In pregnant cynomolgus monkeys, there was no evidence of embryotoxicity or fetal malformations with exposures up to approximately 28 times the exposure at the maximum recommended human dose.

Tavneos (avacopan) (MW, 582) is indicated to treat severe active antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated vasculitis in combination with standard therapy including glucocorticoids. There appears to be an increased risk for hepatotoxicity. The drug caused no defects in hamsters and rabbits, but in rabbits there was an increase in abortions.

Tezspire (tezepelumab-ekko) (MW, 147k) is indicated to treat severe asthma as an add-on maintenance therapy. No adverse fetal effects were observed in pregnant cynomolgus monkeys.

Verquvo (vericiguat) (MW, 426) is used to mitigate the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for chronic heart failure. The drug was teratogenic in pregnant rabbits but not rats.

Vyvgart (efgartigimod alfa-fcab) (MW, 54k) is indicated to treat generalized myasthenia gravis. The drug did not cause birth defects in rats and rabbits.

Welireg (belzutifan) (MW, 383) is used to treat von Hippel–Lindau disease. In pregnant rats, the drug caused embryo-fetal lethality, reduced fetal body weight, and caused fetal skeletal malformations at maternal exposures of at least 0.2 times the human exposures.

Zegalogue (dasiglucagon) (MW, 3,382) is used to treat severe hypoglycemia. The drug did not cause birth defects in pregnant rats and rabbits.

Breastfeeding

It is not known if the above drugs will be in breast milk, but the safest course for an infant is to not breast feed if the mother is taking any of the above drugs.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Indications and techniques for multifetal pregnancy reduction

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

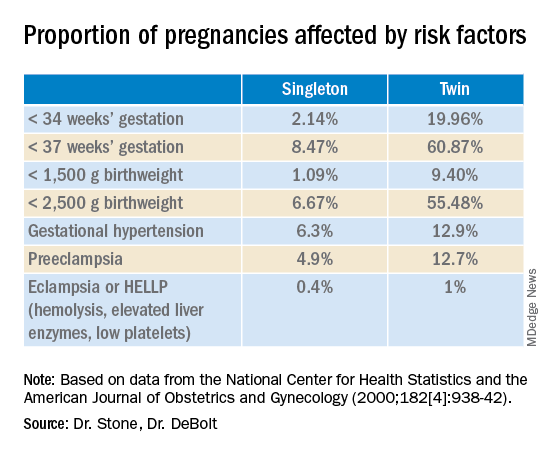

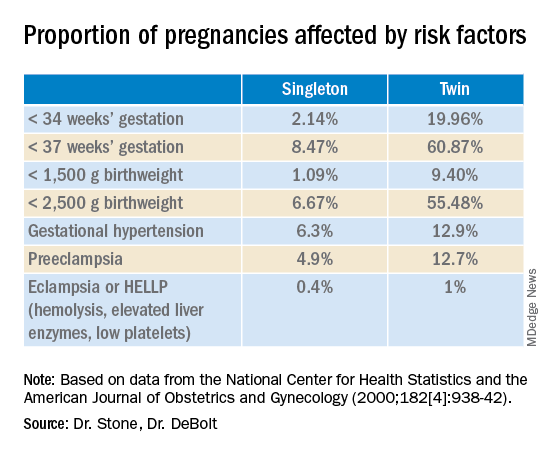

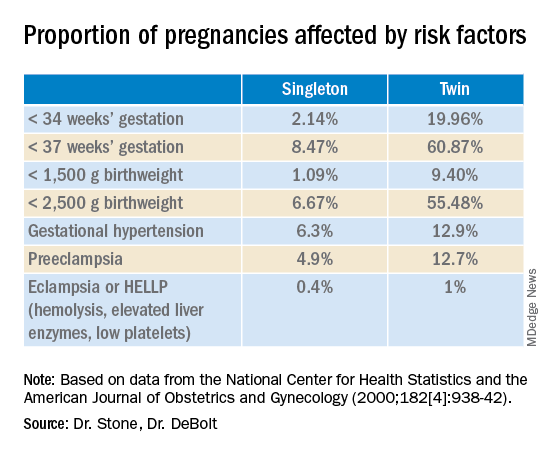

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

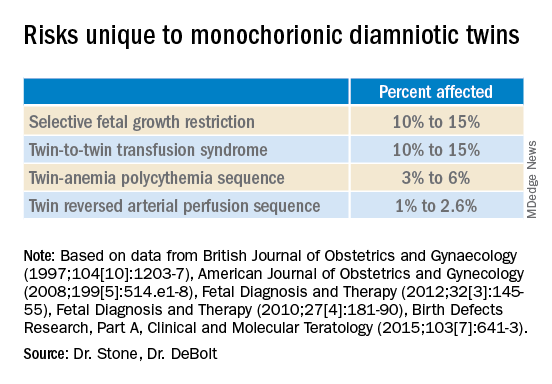

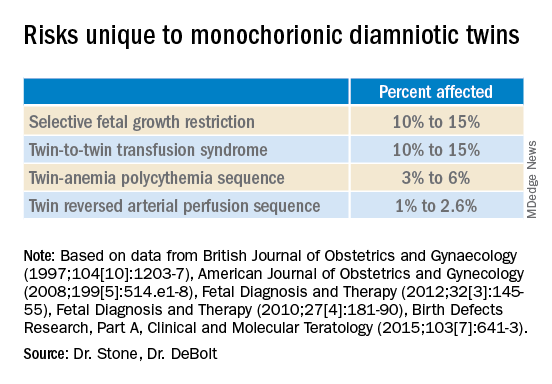

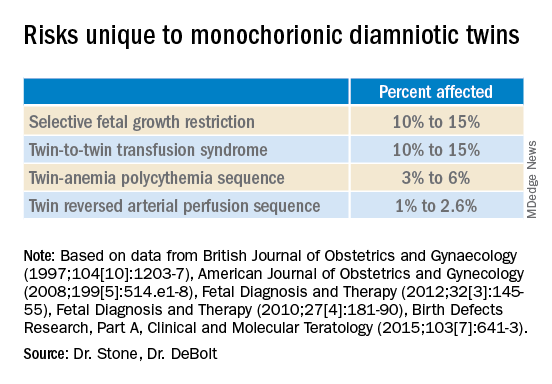

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

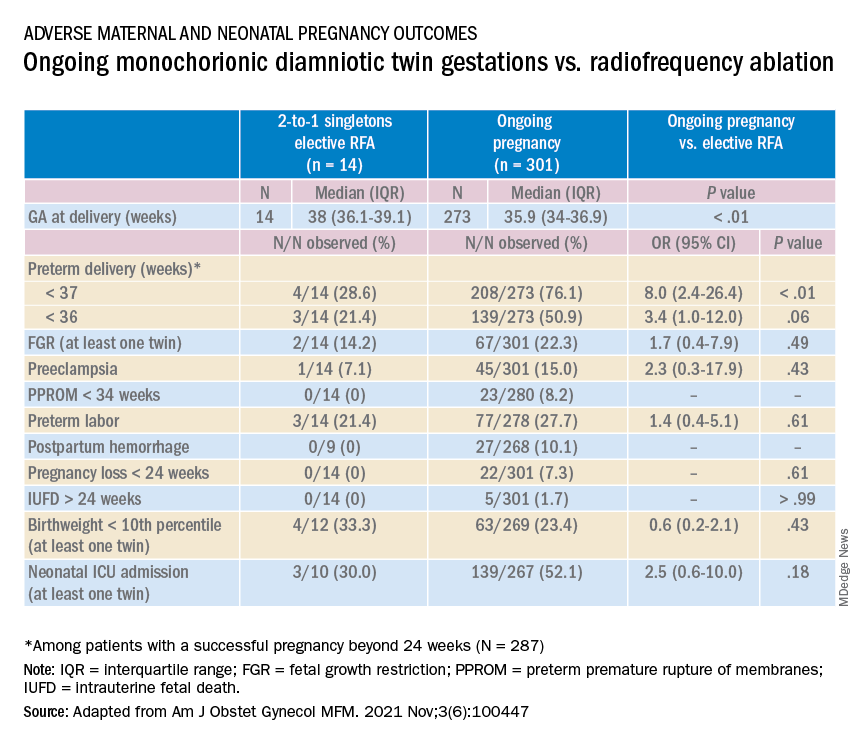

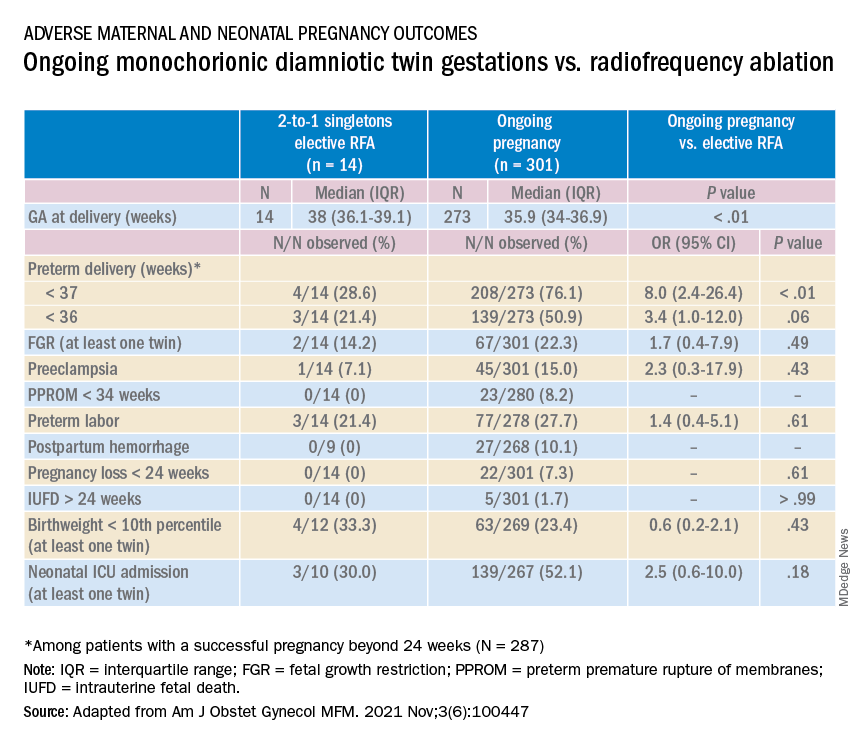

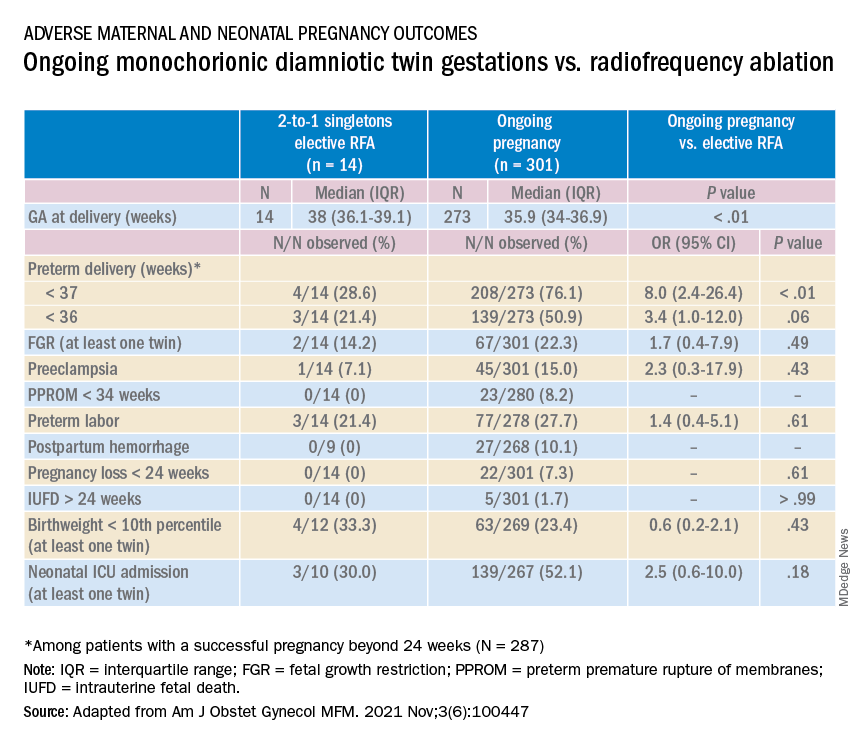

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Managing maternal mortality with multifetal pregnancy reduction

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

Mediterranean diet linked to lower risk for preeclampsia

Pregnant women who had a higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet had a lower risk of preeclampsia, according to the results of a new study.

“As an observational study, it obviously has limitations that need to be considered, but these results build on other evidence that Mediterranean diet reduces cardiovascular risk and extends those findings to pregnancy as preeclampsia is a cardiovascular outcome,” senior author Noel T. Mueller, PhD, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in an interview.

The study was published online April 20 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The authors noted that preeclampsia, characterized by a range of symptoms including hypertension, proteinuria, and end-organ dysfunction, is a disorder that occurs in up to 5%-10% of all pregnant women worldwide, and is more common in Black women. It is a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and raises the risk for long-term cardiovascular disease (CVD), including chronic hypertension, coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, and heart failure.

Children born to mothers with preeclampsia are at an elevated risk of having higher blood pressure and other abnormal cardiometabolic parameters.

The authors noted that multiple studies have demonstrated the benefit of the Mediterranean diet – characterized primarily by high intake of vegetables, fruits, and unsaturated fats – in reducing cardiovascular risk in the nonpregnant population. The current study was conducted to investigate whether benefits could also be seen in pregnant women in the form of a reduced risk of preeclampsia.

For the study, which used data from the Boston Birth Cohort, maternal sociodemographic and dietary data were obtained from 8,507 women via interview and food frequency questionnaire within 24-72 hours of giving birth. A Mediterranean-style diet score was calculated from the food frequency questionnaire. Additional clinical information, including physician diagnoses of preexisting conditions and preeclampsia, were extracted from medical records.

Of the women in the sample, 848 developed preeclampsia, of whom 47% were Black, and 28% were Hispanic.

After multivariable adjustment, the greatest adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was associated with lower odds of developing preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio comparing tertile 3 to tertile 1, 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64-0.96).

A subgroup analysis of Black women demonstrated a similar benefit with an adjusted odds ratio comparing tertile 3 to tertile 1 of 0.74 (95% CI, 0.76-0.96).

“In this racially and ethnically diverse cohort, women who had greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet during pregnancy had a greater than 20% lower odds of developing preeclampsia, after [adjustment] for potential confounders. In addition, the evidence for the protective effect of a Mediterranean-style diet against the odds of developing preeclampsia remained present in a subgroup analysis of Black women,” the researchers concluded.

Asked whether this would be enough evidence to recommend a Mediterranean diet to pregnant women, Dr. Mueller said that the organizations that issue dietary guidelines would probably require replication of these results and also possibly a randomized trial in a diverse population group before advocating such a diet.

“That is something we would like to do but this will take time and money,” he added.

Lead study author Anum Minhas, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said that in the meantime she would be recommending a Mediterranean diet to her pregnant patients.

“The Mediterranean diet is a very healthy way of eating. I can’t see any downside of following such a diet in pregnancy, especially for high-risk women – those with obesity, hypertension or gestational diabetes, and there are likely other potential benefits such as reduced weight gain and reduced gestational diabetes,” she said.

Dr. Mueller said he appreciated this pragmatic approach. “Sometimes there can be hesitation on making recommendations from observational studies, but the alternative to recommending this diet is either no recommendations on diet or recommending an alternative diet,” he said. “The Mediterranean diet or the DASH diet, which is quite similar, have shown by far the most evidence of cardioprotection of any diets. They have been shown to reduce blood pressure and lipids and improve cardiovascular risk, and I think we can now assume that that likely extends to pregnancy. I feel comfortable for this diet to be recommended to pregnant women.”

But he added: “Having said that, there is still a need for a randomized trial in pregnancy. We think it works but until we have a randomized trial we won’t know for sure, and we won’t know how much of a benefit we can get.”

Commenting on the study, JoAnn Manson, MD, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, pointed out that this type of observational study is important for hypothesis generation but cannot prove cause and effect relationships.

“The evidence is promising enough,” said Dr. Manson, who was not involved with this study. But she added that to move forward, a randomized trial in women at elevated risk of preeclampsia would be needed, beginning in early pregnancy, if not earlier.

“In the meantime,” she noted, “several large-scale cohorts could be leveraged to look at diet assessed before or during pregnancy to see if this dietary pattern is prospectively related to lower risk of preeclampsia.

“With additional supportive data, and in view of the diet’s safety and general cardiovascular benefits, it could become a major tool for preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

The Boston Birth Cohort study was supported in part by grants from the March of Dimes, the National Institutes of Health, and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnant women who had a higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet had a lower risk of preeclampsia, according to the results of a new study.

“As an observational study, it obviously has limitations that need to be considered, but these results build on other evidence that Mediterranean diet reduces cardiovascular risk and extends those findings to pregnancy as preeclampsia is a cardiovascular outcome,” senior author Noel T. Mueller, PhD, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in an interview.

The study was published online April 20 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The authors noted that preeclampsia, characterized by a range of symptoms including hypertension, proteinuria, and end-organ dysfunction, is a disorder that occurs in up to 5%-10% of all pregnant women worldwide, and is more common in Black women. It is a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and raises the risk for long-term cardiovascular disease (CVD), including chronic hypertension, coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, and heart failure.

Children born to mothers with preeclampsia are at an elevated risk of having higher blood pressure and other abnormal cardiometabolic parameters.

The authors noted that multiple studies have demonstrated the benefit of the Mediterranean diet – characterized primarily by high intake of vegetables, fruits, and unsaturated fats – in reducing cardiovascular risk in the nonpregnant population. The current study was conducted to investigate whether benefits could also be seen in pregnant women in the form of a reduced risk of preeclampsia.