User login

Application of Hand Therapy Extensor Tendon Protocol to Toe Extensor Tendon Rehabilitation

Plastic and orthopedic surgeons worked closely with therapists in military hospitals to rehabilitate soldiers afflicted with upper extremity trauma during World War II. Together, they developed treatment protocols. In 1975, the American Society for Hand Therapists (ASHT) was created during the American Society for Surgery of the Hand meeting. The ASHT application process required case studies, patient logs, and clinical hours, so membership was equivalent to competency. In May 1991, the first hand certification examination took place and designated the first group of certified hand therapists (CHT).1

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs collaboration takes place between different services and communication is facilitated using the electronic heath record. The case presented here is an example of several services (emergency medicine, plastic/hand surgery, and occupational therapy) working together to develop a treatment plan for a condition that often goes undiagnosed or untreated. This article describes an innovative application of hand extensor tendon therapy clinical decision making to rehabilitate foot extensor tendons when the plastic surgery service was called on to work outside its usual comfort zone of the hand and upper extremity. The hand therapist applied hand extensor tendon rehabilitation principles to recover toe extensor lacerations.

Certified hand therapists (CHTs) are key to a successful hand surgery practice. The Plastic Surgery Service at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida, relies heavily on the CHTs to optimize patient outcomes. The hand surgery clinic and hand therapy clinics are in the same hospital building, allowing for easy face-to-face communication. Hand therapy students are able to observe cases in the operating room. Immediately after surgery, follow-up consults are scheduled to coordinate postoperative care between the services.

Case Presentation

The next day, the patient was examined in the plastic surgery clinic and found to have a completely lacerated extensor digitorum brevis to the second toe and a completely lacerated extensor digitorum longus to the third toe. These were located proximal to the metatarsal phalangeal joints. Surgery was scheduled for the following week.

In surgery, the tendons were sharply debrided and repaired using a 3.0 Ethibond suture placed in a modified Kessler technique followed by a horizontal mattress for a total of a 4-core repair. This was reinforced with a No. 6 Prolene to the paratendon. The surgery was performed under IV sedation and an ankle block, using 17 minutes of tourniquet time.

On postoperative day 1, the patient was seen in plastic surgery and occupational therapy clinic. The hand therapist modified the hand extensor tendon repair protocol since there was no known protocol for repairs of the foot and toe extensor tendon. The patient was placed in an ankle foot orthosis with a toe extension device created by heating and molding a low-temperature thermoplastic sheet (Figure 2). The toes were boosted into slight hyper extension. This was done to reduce tension across the extensor tendon repair site. All of the toes were held in about 20°of extension, as the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) has a common origin, to aide in adherence of wearing and for comfort. No standing or weight bearing was permitted for 3 weeks.

A wheelchair was issued in lieu of crutches to inhibit the work of toe extension with gait swing-through. Otherwise, the patient would generate tension on the extensor tendon in order for the toes to clear the ground. It was postulated that it would be difficult to turn off the toe extensors while using crutches. Maximal laxity was desired because edema and early scar formation could increase tension on the repair, resulting in rupture if the patient tried to fire the muscle belly even while in passive extension.

The patient kept his appointments and progressed steadily. He started passive toe extension and relaxation once per day for 30 repetitions at 1 week to aide in tendon glide. He started place and hold techniques in toe extension at 3 weeks. This progressed to active extension 50% effort plus active flexion at 4 weeks after surgery, then 75% extension effort plus toe towel crunches at 5 weeks. Toe crunches are toe flexion exercises with a washcloth on the floor with active bending of the toes with light resistance similar to picking up a marble with the toes. He was found to have a third toe extensor lag at that time that was correctible. The patient was actively able to flex and extend the toe independently. The early extension lag was felt to be secondary to edema and scar formation, which, over time are anticipated to resolve and contract and effectively shorten the tendon. Tendon gliding, and scar massage were reviewed. The patient’s last therapy session occurred 7 weeks after surgery, and he was cleared for full activity at 12 weeks. There was no further follow-up as he was planning on back surgery 2 weeks later.

Discussion

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System is fortunate to have 4 CHTs on staff. CHTs take a 200 question 4 hour certifying exam after being licensed for a minimum of 3 years as a physical or occupational therapist and completing 4,000 hours of direct upper extremity patient experience. Pass rates from 2008 to 2018 ranged from 52% to 68%.3 These clinicians are key to the success of our hand surgery service, utilizing their education and skills on our elective and trauma cases. The hand therapy service applied their knowledge of hand extensor rehabilitation protocols to rehabilitate the patient’s toe extensor in the absence of clear guidelines.

Hand extensor tendon rehabilitation protocols are based on the location of the repair on the hand or forearm. Nine extensor zones are named, distal to proximal, from the distal interphalangeal joints to the proximal forearm (Figure 3). In his review of extensor hallucis longus (EHL) repairs, Al-Qattan described 6 foot-extensor tendon zones, distal to proximal, from the first toe at the insertion of the big toe extensor to the distal leg proximal to the extensor retinaculum (Figure 4).4 Zone 3 is over the metatarsophalangeal joint; zone 5 is under the extensor retinaculum. The extensor tendon repairs described in this report were in dorsal foot zone 4 (proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joint and over the metatarsals), which would be most comparable to hand extensor zone 6 (proximal to the metacarpal phalangeal joint and over the metacarpals).

The EDL originates on the lateral condyle of the tibia and anterior surface of the fibula and the interosseous membrane, passes under the extensor retinaculum, and divides into 4 separate tendons. The 4 tendons split into 3 slips; the central one inserts on the middle phalanx, and the lateral ones insert onto the distal phalanx of the 4 lateral toes, which allows for toe extension.5 The EDL common origin for the muscle belly that serves 4 tendon slips has clinical significance because rehabilitation for one digit will affect the others. Knowledge of the anatomical structures guides the clinical decision making whether it is in the hand or foot. The EDL works synergistically with the extensor digitorum brevis (EDBr) to dorsiflex (extend) the toe phalanges. The EDB originates at the supralateral surface of the calcaneus, lateral talocalcaneal ligament and cruciate crural ligament and inserts at the lateral side of the EDL of second, third, and fourth toes at the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint.6

Repair of lacerated extensor tendons in the foot is the recommended treatment. Chronic extensor lag of the phalanges can result in a claw toe deformity, difficulty controlling the toes when putting on shoes or socks, and catching of the toe on fabric or insoles.7 The extensor tendons are close to the deep and superficial peroneal nerves and to the dorsalis pedis artery, none of which were involved in this case report.

There are case reports and series of EHL repairs that all involves at least 3 weeks of immobilization.4,8,9 The EHL dorsiflexes the big toe. Al-Qattan’s series involved placing K wires across the interphalangeal joint of the big toe and across the metatarsophalangeal joint, which were removed at 6 weeks, in addition to 3.0 polypropylene tendon mattress sutures. All patients in this series healed without tendon rupture or infection. Our PubMed search did not reveal any specific protocol for the EDL or EDB tendons, which are anatomically most comparable to the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons in the hand. The EDC originates at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, also divides into 4 separate tendons and is responsible for extending the 4 ulnar sided fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joint.10

Tendon repair protocols are a balance between preventing tendon rupture by too aggressive therapy and with preventing tendon adhesions from prolonged immobilization. Orthotic fabrication plays a key early role with blocking possible forces creating unacceptable strain or tension across the surgical repair site. Traditionally, extensor tendon repairs in the hand were immobilized for at least 3 weeks to prevent rupture. This is still the preferred protocol for the patient unwilling or unable to follow instructions. The downside to this method is extension lags, extrinsic tightness, and adhesions that prevent flexion, which can require prolonged therapy or tenolysis surgery to correct.11-13

Early passive motion (EPM) was promoted in the 1980s when studies found better functional outcomes and fewer adhesions. This involved either a dynamic extension splint that relied on elastic bands (Louisville protocol) to keep tension off the repair or the Duran protocol that relied on a static splint and the patient doing the passive exercises with his other uninjured hand. Critics of the EPM protocol point to the costs of the splints and demands of postoperative hand therapy.11

Early active motion (EAM) is the most recent development in hand tendon rehabilitation and starts within days of surgery. Studies have found an earlier regain of total active motion in patients who are mobilized earlier.12 EAM protocols can be divided into controlled active motion (CAM) and relative motion extension splinting (RMES). CAM splints are forearm based and cross more joints. Relative motion splinting is the least restrictive, which makes it less likely that the patient will remove it. Patient friendly splints are ideal because tendon ruptures are often secondary to nonadherence.13 The yoke splint is an example of a RMES, which places the repaired digit in slightly greater extension at the metacarpal phalangeal joint than the other digits (Figure 5), allowing use of the uninjured digits.

The toe extensors do not have the juncturae tendinum connecting the individual EDL tendons to each other, as found between the EDC tendons in the hand. These connective bands can mask a single extensor tendon laceration in the hand when the patient is still able to extend the digit to neutral in the event of a more proximal dorsal hand laceration. A case can be made for closing the skin only in lesser toe extensor injuries in poor surgical candidates because the extensor lag would not be appreciated functionally when wearing shoes. There would be less functional impact when letting a toe extensor go untreated compared with that of a hand extensor. Routine activities such as typing or getting the fingers into a tight pocket could be challenging if hand extensors were untreated. The rehabilitation for toe extensors is more inconvenient when a patient is nonweight bearing, compared with wearing a hand yoke splint.

Conclusion

The case described used an early passive motion protocol without the dynamic splint to rehabilitate the third toe EDL and second toe EDB. This was felt to be the most patient and therapist friendly option, given the previously unchartered territory. The foot orthosis was in stock at the adjacent physical therapy clinic, and the toe booster was created in the hand therapy clinic with readily available supplies. Ideally, one would like to return structures to their anatomic site and control the healing process in the event of a traumatic injury to prevent nonanatomic healing between structures and painful scar adhesions in an area with little subcutaneous tissue. This patient’s tendon repair was still intact at 7 weeks and on his way to recovery, demonstrating good scar management techniques. The risks and benefits to lesser toe tendon repair and recovery would have to be weighed on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. History of HTCC. https://www.htcc.org/consumer-information/about-htcc/history-of-htcc. Accessed November 8, 2019.

2. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

3. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. Passing rates for the CHT exam. https://www.htcc.org/certify/exam-results/passing-rates. Accessed November 8, 2019.

4. Al-Qattan MM. Surgical treatment and results in 17 cases of open lacerations of the extensor hallucis longus tendon. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(4):360-367.

5. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum longus. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_longus. Updated December 8, 2011. Accessed November 8, 2019.

6. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum brevis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_brevis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

7. Coughlin M, Schon L. Disorders of tendons. https://musculoskeletalkey.com/disorders-of-tendons-2/#s0035. Published August 27, 2016. Accessed November 8, 2019.

8. Bronner S, Ojofeitimi S, Rose D. Repair and rehabilitation of extensor hallucis longus and brevis tendon lacerations in a professional dancer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(6):362-370.

9. Wong JC, Daniel JN, Raikin SM. Repair of acute extensor hallucis longus tendon injuries: a retrospective review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7(1):45-51.

10. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum communis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_communis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

11. Hall B, Lee H, Page R, Rosenwax L, Lee AH. Comparing three postoperative treatment protocols for extensor tendon repair in zones V and VI of the hand. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(5):682-688.

12. Wong AL, Wilson M, Girnary S, Nojoomi M, Acharya S, Paul SM. The optimal orthosis and motion protocol for extensor tendon injury in zones IV-VIII: a systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2017;30(4):447-456.

13. Collocott SJ, Kelly E, Ellis RF. Optimal early active mobilisation protocol after extensor tendon repairs in zones V and VI: a systematic review of literature. Hand Ther. 2018;23(1):3-18.

Plastic and orthopedic surgeons worked closely with therapists in military hospitals to rehabilitate soldiers afflicted with upper extremity trauma during World War II. Together, they developed treatment protocols. In 1975, the American Society for Hand Therapists (ASHT) was created during the American Society for Surgery of the Hand meeting. The ASHT application process required case studies, patient logs, and clinical hours, so membership was equivalent to competency. In May 1991, the first hand certification examination took place and designated the first group of certified hand therapists (CHT).1

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs collaboration takes place between different services and communication is facilitated using the electronic heath record. The case presented here is an example of several services (emergency medicine, plastic/hand surgery, and occupational therapy) working together to develop a treatment plan for a condition that often goes undiagnosed or untreated. This article describes an innovative application of hand extensor tendon therapy clinical decision making to rehabilitate foot extensor tendons when the plastic surgery service was called on to work outside its usual comfort zone of the hand and upper extremity. The hand therapist applied hand extensor tendon rehabilitation principles to recover toe extensor lacerations.

Certified hand therapists (CHTs) are key to a successful hand surgery practice. The Plastic Surgery Service at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida, relies heavily on the CHTs to optimize patient outcomes. The hand surgery clinic and hand therapy clinics are in the same hospital building, allowing for easy face-to-face communication. Hand therapy students are able to observe cases in the operating room. Immediately after surgery, follow-up consults are scheduled to coordinate postoperative care between the services.

Case Presentation

The next day, the patient was examined in the plastic surgery clinic and found to have a completely lacerated extensor digitorum brevis to the second toe and a completely lacerated extensor digitorum longus to the third toe. These were located proximal to the metatarsal phalangeal joints. Surgery was scheduled for the following week.

In surgery, the tendons were sharply debrided and repaired using a 3.0 Ethibond suture placed in a modified Kessler technique followed by a horizontal mattress for a total of a 4-core repair. This was reinforced with a No. 6 Prolene to the paratendon. The surgery was performed under IV sedation and an ankle block, using 17 minutes of tourniquet time.

On postoperative day 1, the patient was seen in plastic surgery and occupational therapy clinic. The hand therapist modified the hand extensor tendon repair protocol since there was no known protocol for repairs of the foot and toe extensor tendon. The patient was placed in an ankle foot orthosis with a toe extension device created by heating and molding a low-temperature thermoplastic sheet (Figure 2). The toes were boosted into slight hyper extension. This was done to reduce tension across the extensor tendon repair site. All of the toes were held in about 20°of extension, as the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) has a common origin, to aide in adherence of wearing and for comfort. No standing or weight bearing was permitted for 3 weeks.

A wheelchair was issued in lieu of crutches to inhibit the work of toe extension with gait swing-through. Otherwise, the patient would generate tension on the extensor tendon in order for the toes to clear the ground. It was postulated that it would be difficult to turn off the toe extensors while using crutches. Maximal laxity was desired because edema and early scar formation could increase tension on the repair, resulting in rupture if the patient tried to fire the muscle belly even while in passive extension.

The patient kept his appointments and progressed steadily. He started passive toe extension and relaxation once per day for 30 repetitions at 1 week to aide in tendon glide. He started place and hold techniques in toe extension at 3 weeks. This progressed to active extension 50% effort plus active flexion at 4 weeks after surgery, then 75% extension effort plus toe towel crunches at 5 weeks. Toe crunches are toe flexion exercises with a washcloth on the floor with active bending of the toes with light resistance similar to picking up a marble with the toes. He was found to have a third toe extensor lag at that time that was correctible. The patient was actively able to flex and extend the toe independently. The early extension lag was felt to be secondary to edema and scar formation, which, over time are anticipated to resolve and contract and effectively shorten the tendon. Tendon gliding, and scar massage were reviewed. The patient’s last therapy session occurred 7 weeks after surgery, and he was cleared for full activity at 12 weeks. There was no further follow-up as he was planning on back surgery 2 weeks later.

Discussion

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System is fortunate to have 4 CHTs on staff. CHTs take a 200 question 4 hour certifying exam after being licensed for a minimum of 3 years as a physical or occupational therapist and completing 4,000 hours of direct upper extremity patient experience. Pass rates from 2008 to 2018 ranged from 52% to 68%.3 These clinicians are key to the success of our hand surgery service, utilizing their education and skills on our elective and trauma cases. The hand therapy service applied their knowledge of hand extensor rehabilitation protocols to rehabilitate the patient’s toe extensor in the absence of clear guidelines.

Hand extensor tendon rehabilitation protocols are based on the location of the repair on the hand or forearm. Nine extensor zones are named, distal to proximal, from the distal interphalangeal joints to the proximal forearm (Figure 3). In his review of extensor hallucis longus (EHL) repairs, Al-Qattan described 6 foot-extensor tendon zones, distal to proximal, from the first toe at the insertion of the big toe extensor to the distal leg proximal to the extensor retinaculum (Figure 4).4 Zone 3 is over the metatarsophalangeal joint; zone 5 is under the extensor retinaculum. The extensor tendon repairs described in this report were in dorsal foot zone 4 (proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joint and over the metatarsals), which would be most comparable to hand extensor zone 6 (proximal to the metacarpal phalangeal joint and over the metacarpals).

The EDL originates on the lateral condyle of the tibia and anterior surface of the fibula and the interosseous membrane, passes under the extensor retinaculum, and divides into 4 separate tendons. The 4 tendons split into 3 slips; the central one inserts on the middle phalanx, and the lateral ones insert onto the distal phalanx of the 4 lateral toes, which allows for toe extension.5 The EDL common origin for the muscle belly that serves 4 tendon slips has clinical significance because rehabilitation for one digit will affect the others. Knowledge of the anatomical structures guides the clinical decision making whether it is in the hand or foot. The EDL works synergistically with the extensor digitorum brevis (EDBr) to dorsiflex (extend) the toe phalanges. The EDB originates at the supralateral surface of the calcaneus, lateral talocalcaneal ligament and cruciate crural ligament and inserts at the lateral side of the EDL of second, third, and fourth toes at the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint.6

Repair of lacerated extensor tendons in the foot is the recommended treatment. Chronic extensor lag of the phalanges can result in a claw toe deformity, difficulty controlling the toes when putting on shoes or socks, and catching of the toe on fabric or insoles.7 The extensor tendons are close to the deep and superficial peroneal nerves and to the dorsalis pedis artery, none of which were involved in this case report.

There are case reports and series of EHL repairs that all involves at least 3 weeks of immobilization.4,8,9 The EHL dorsiflexes the big toe. Al-Qattan’s series involved placing K wires across the interphalangeal joint of the big toe and across the metatarsophalangeal joint, which were removed at 6 weeks, in addition to 3.0 polypropylene tendon mattress sutures. All patients in this series healed without tendon rupture or infection. Our PubMed search did not reveal any specific protocol for the EDL or EDB tendons, which are anatomically most comparable to the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons in the hand. The EDC originates at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, also divides into 4 separate tendons and is responsible for extending the 4 ulnar sided fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joint.10

Tendon repair protocols are a balance between preventing tendon rupture by too aggressive therapy and with preventing tendon adhesions from prolonged immobilization. Orthotic fabrication plays a key early role with blocking possible forces creating unacceptable strain or tension across the surgical repair site. Traditionally, extensor tendon repairs in the hand were immobilized for at least 3 weeks to prevent rupture. This is still the preferred protocol for the patient unwilling or unable to follow instructions. The downside to this method is extension lags, extrinsic tightness, and adhesions that prevent flexion, which can require prolonged therapy or tenolysis surgery to correct.11-13

Early passive motion (EPM) was promoted in the 1980s when studies found better functional outcomes and fewer adhesions. This involved either a dynamic extension splint that relied on elastic bands (Louisville protocol) to keep tension off the repair or the Duran protocol that relied on a static splint and the patient doing the passive exercises with his other uninjured hand. Critics of the EPM protocol point to the costs of the splints and demands of postoperative hand therapy.11

Early active motion (EAM) is the most recent development in hand tendon rehabilitation and starts within days of surgery. Studies have found an earlier regain of total active motion in patients who are mobilized earlier.12 EAM protocols can be divided into controlled active motion (CAM) and relative motion extension splinting (RMES). CAM splints are forearm based and cross more joints. Relative motion splinting is the least restrictive, which makes it less likely that the patient will remove it. Patient friendly splints are ideal because tendon ruptures are often secondary to nonadherence.13 The yoke splint is an example of a RMES, which places the repaired digit in slightly greater extension at the metacarpal phalangeal joint than the other digits (Figure 5), allowing use of the uninjured digits.

The toe extensors do not have the juncturae tendinum connecting the individual EDL tendons to each other, as found between the EDC tendons in the hand. These connective bands can mask a single extensor tendon laceration in the hand when the patient is still able to extend the digit to neutral in the event of a more proximal dorsal hand laceration. A case can be made for closing the skin only in lesser toe extensor injuries in poor surgical candidates because the extensor lag would not be appreciated functionally when wearing shoes. There would be less functional impact when letting a toe extensor go untreated compared with that of a hand extensor. Routine activities such as typing or getting the fingers into a tight pocket could be challenging if hand extensors were untreated. The rehabilitation for toe extensors is more inconvenient when a patient is nonweight bearing, compared with wearing a hand yoke splint.

Conclusion

The case described used an early passive motion protocol without the dynamic splint to rehabilitate the third toe EDL and second toe EDB. This was felt to be the most patient and therapist friendly option, given the previously unchartered territory. The foot orthosis was in stock at the adjacent physical therapy clinic, and the toe booster was created in the hand therapy clinic with readily available supplies. Ideally, one would like to return structures to their anatomic site and control the healing process in the event of a traumatic injury to prevent nonanatomic healing between structures and painful scar adhesions in an area with little subcutaneous tissue. This patient’s tendon repair was still intact at 7 weeks and on his way to recovery, demonstrating good scar management techniques. The risks and benefits to lesser toe tendon repair and recovery would have to be weighed on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

Plastic and orthopedic surgeons worked closely with therapists in military hospitals to rehabilitate soldiers afflicted with upper extremity trauma during World War II. Together, they developed treatment protocols. In 1975, the American Society for Hand Therapists (ASHT) was created during the American Society for Surgery of the Hand meeting. The ASHT application process required case studies, patient logs, and clinical hours, so membership was equivalent to competency. In May 1991, the first hand certification examination took place and designated the first group of certified hand therapists (CHT).1

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs collaboration takes place between different services and communication is facilitated using the electronic heath record. The case presented here is an example of several services (emergency medicine, plastic/hand surgery, and occupational therapy) working together to develop a treatment plan for a condition that often goes undiagnosed or untreated. This article describes an innovative application of hand extensor tendon therapy clinical decision making to rehabilitate foot extensor tendons when the plastic surgery service was called on to work outside its usual comfort zone of the hand and upper extremity. The hand therapist applied hand extensor tendon rehabilitation principles to recover toe extensor lacerations.

Certified hand therapists (CHTs) are key to a successful hand surgery practice. The Plastic Surgery Service at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida, relies heavily on the CHTs to optimize patient outcomes. The hand surgery clinic and hand therapy clinics are in the same hospital building, allowing for easy face-to-face communication. Hand therapy students are able to observe cases in the operating room. Immediately after surgery, follow-up consults are scheduled to coordinate postoperative care between the services.

Case Presentation

The next day, the patient was examined in the plastic surgery clinic and found to have a completely lacerated extensor digitorum brevis to the second toe and a completely lacerated extensor digitorum longus to the third toe. These were located proximal to the metatarsal phalangeal joints. Surgery was scheduled for the following week.

In surgery, the tendons were sharply debrided and repaired using a 3.0 Ethibond suture placed in a modified Kessler technique followed by a horizontal mattress for a total of a 4-core repair. This was reinforced with a No. 6 Prolene to the paratendon. The surgery was performed under IV sedation and an ankle block, using 17 minutes of tourniquet time.

On postoperative day 1, the patient was seen in plastic surgery and occupational therapy clinic. The hand therapist modified the hand extensor tendon repair protocol since there was no known protocol for repairs of the foot and toe extensor tendon. The patient was placed in an ankle foot orthosis with a toe extension device created by heating and molding a low-temperature thermoplastic sheet (Figure 2). The toes were boosted into slight hyper extension. This was done to reduce tension across the extensor tendon repair site. All of the toes were held in about 20°of extension, as the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) has a common origin, to aide in adherence of wearing and for comfort. No standing or weight bearing was permitted for 3 weeks.

A wheelchair was issued in lieu of crutches to inhibit the work of toe extension with gait swing-through. Otherwise, the patient would generate tension on the extensor tendon in order for the toes to clear the ground. It was postulated that it would be difficult to turn off the toe extensors while using crutches. Maximal laxity was desired because edema and early scar formation could increase tension on the repair, resulting in rupture if the patient tried to fire the muscle belly even while in passive extension.

The patient kept his appointments and progressed steadily. He started passive toe extension and relaxation once per day for 30 repetitions at 1 week to aide in tendon glide. He started place and hold techniques in toe extension at 3 weeks. This progressed to active extension 50% effort plus active flexion at 4 weeks after surgery, then 75% extension effort plus toe towel crunches at 5 weeks. Toe crunches are toe flexion exercises with a washcloth on the floor with active bending of the toes with light resistance similar to picking up a marble with the toes. He was found to have a third toe extensor lag at that time that was correctible. The patient was actively able to flex and extend the toe independently. The early extension lag was felt to be secondary to edema and scar formation, which, over time are anticipated to resolve and contract and effectively shorten the tendon. Tendon gliding, and scar massage were reviewed. The patient’s last therapy session occurred 7 weeks after surgery, and he was cleared for full activity at 12 weeks. There was no further follow-up as he was planning on back surgery 2 weeks later.

Discussion

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System is fortunate to have 4 CHTs on staff. CHTs take a 200 question 4 hour certifying exam after being licensed for a minimum of 3 years as a physical or occupational therapist and completing 4,000 hours of direct upper extremity patient experience. Pass rates from 2008 to 2018 ranged from 52% to 68%.3 These clinicians are key to the success of our hand surgery service, utilizing their education and skills on our elective and trauma cases. The hand therapy service applied their knowledge of hand extensor rehabilitation protocols to rehabilitate the patient’s toe extensor in the absence of clear guidelines.

Hand extensor tendon rehabilitation protocols are based on the location of the repair on the hand or forearm. Nine extensor zones are named, distal to proximal, from the distal interphalangeal joints to the proximal forearm (Figure 3). In his review of extensor hallucis longus (EHL) repairs, Al-Qattan described 6 foot-extensor tendon zones, distal to proximal, from the first toe at the insertion of the big toe extensor to the distal leg proximal to the extensor retinaculum (Figure 4).4 Zone 3 is over the metatarsophalangeal joint; zone 5 is under the extensor retinaculum. The extensor tendon repairs described in this report were in dorsal foot zone 4 (proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joint and over the metatarsals), which would be most comparable to hand extensor zone 6 (proximal to the metacarpal phalangeal joint and over the metacarpals).

The EDL originates on the lateral condyle of the tibia and anterior surface of the fibula and the interosseous membrane, passes under the extensor retinaculum, and divides into 4 separate tendons. The 4 tendons split into 3 slips; the central one inserts on the middle phalanx, and the lateral ones insert onto the distal phalanx of the 4 lateral toes, which allows for toe extension.5 The EDL common origin for the muscle belly that serves 4 tendon slips has clinical significance because rehabilitation for one digit will affect the others. Knowledge of the anatomical structures guides the clinical decision making whether it is in the hand or foot. The EDL works synergistically with the extensor digitorum brevis (EDBr) to dorsiflex (extend) the toe phalanges. The EDB originates at the supralateral surface of the calcaneus, lateral talocalcaneal ligament and cruciate crural ligament and inserts at the lateral side of the EDL of second, third, and fourth toes at the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint.6

Repair of lacerated extensor tendons in the foot is the recommended treatment. Chronic extensor lag of the phalanges can result in a claw toe deformity, difficulty controlling the toes when putting on shoes or socks, and catching of the toe on fabric or insoles.7 The extensor tendons are close to the deep and superficial peroneal nerves and to the dorsalis pedis artery, none of which were involved in this case report.

There are case reports and series of EHL repairs that all involves at least 3 weeks of immobilization.4,8,9 The EHL dorsiflexes the big toe. Al-Qattan’s series involved placing K wires across the interphalangeal joint of the big toe and across the metatarsophalangeal joint, which were removed at 6 weeks, in addition to 3.0 polypropylene tendon mattress sutures. All patients in this series healed without tendon rupture or infection. Our PubMed search did not reveal any specific protocol for the EDL or EDB tendons, which are anatomically most comparable to the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons in the hand. The EDC originates at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, also divides into 4 separate tendons and is responsible for extending the 4 ulnar sided fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joint.10

Tendon repair protocols are a balance between preventing tendon rupture by too aggressive therapy and with preventing tendon adhesions from prolonged immobilization. Orthotic fabrication plays a key early role with blocking possible forces creating unacceptable strain or tension across the surgical repair site. Traditionally, extensor tendon repairs in the hand were immobilized for at least 3 weeks to prevent rupture. This is still the preferred protocol for the patient unwilling or unable to follow instructions. The downside to this method is extension lags, extrinsic tightness, and adhesions that prevent flexion, which can require prolonged therapy or tenolysis surgery to correct.11-13

Early passive motion (EPM) was promoted in the 1980s when studies found better functional outcomes and fewer adhesions. This involved either a dynamic extension splint that relied on elastic bands (Louisville protocol) to keep tension off the repair or the Duran protocol that relied on a static splint and the patient doing the passive exercises with his other uninjured hand. Critics of the EPM protocol point to the costs of the splints and demands of postoperative hand therapy.11

Early active motion (EAM) is the most recent development in hand tendon rehabilitation and starts within days of surgery. Studies have found an earlier regain of total active motion in patients who are mobilized earlier.12 EAM protocols can be divided into controlled active motion (CAM) and relative motion extension splinting (RMES). CAM splints are forearm based and cross more joints. Relative motion splinting is the least restrictive, which makes it less likely that the patient will remove it. Patient friendly splints are ideal because tendon ruptures are often secondary to nonadherence.13 The yoke splint is an example of a RMES, which places the repaired digit in slightly greater extension at the metacarpal phalangeal joint than the other digits (Figure 5), allowing use of the uninjured digits.

The toe extensors do not have the juncturae tendinum connecting the individual EDL tendons to each other, as found between the EDC tendons in the hand. These connective bands can mask a single extensor tendon laceration in the hand when the patient is still able to extend the digit to neutral in the event of a more proximal dorsal hand laceration. A case can be made for closing the skin only in lesser toe extensor injuries in poor surgical candidates because the extensor lag would not be appreciated functionally when wearing shoes. There would be less functional impact when letting a toe extensor go untreated compared with that of a hand extensor. Routine activities such as typing or getting the fingers into a tight pocket could be challenging if hand extensors were untreated. The rehabilitation for toe extensors is more inconvenient when a patient is nonweight bearing, compared with wearing a hand yoke splint.

Conclusion

The case described used an early passive motion protocol without the dynamic splint to rehabilitate the third toe EDL and second toe EDB. This was felt to be the most patient and therapist friendly option, given the previously unchartered territory. The foot orthosis was in stock at the adjacent physical therapy clinic, and the toe booster was created in the hand therapy clinic with readily available supplies. Ideally, one would like to return structures to their anatomic site and control the healing process in the event of a traumatic injury to prevent nonanatomic healing between structures and painful scar adhesions in an area with little subcutaneous tissue. This patient’s tendon repair was still intact at 7 weeks and on his way to recovery, demonstrating good scar management techniques. The risks and benefits to lesser toe tendon repair and recovery would have to be weighed on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. History of HTCC. https://www.htcc.org/consumer-information/about-htcc/history-of-htcc. Accessed November 8, 2019.

2. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

3. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. Passing rates for the CHT exam. https://www.htcc.org/certify/exam-results/passing-rates. Accessed November 8, 2019.

4. Al-Qattan MM. Surgical treatment and results in 17 cases of open lacerations of the extensor hallucis longus tendon. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(4):360-367.

5. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum longus. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_longus. Updated December 8, 2011. Accessed November 8, 2019.

6. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum brevis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_brevis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

7. Coughlin M, Schon L. Disorders of tendons. https://musculoskeletalkey.com/disorders-of-tendons-2/#s0035. Published August 27, 2016. Accessed November 8, 2019.

8. Bronner S, Ojofeitimi S, Rose D. Repair and rehabilitation of extensor hallucis longus and brevis tendon lacerations in a professional dancer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(6):362-370.

9. Wong JC, Daniel JN, Raikin SM. Repair of acute extensor hallucis longus tendon injuries: a retrospective review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7(1):45-51.

10. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum communis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_communis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

11. Hall B, Lee H, Page R, Rosenwax L, Lee AH. Comparing three postoperative treatment protocols for extensor tendon repair in zones V and VI of the hand. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(5):682-688.

12. Wong AL, Wilson M, Girnary S, Nojoomi M, Acharya S, Paul SM. The optimal orthosis and motion protocol for extensor tendon injury in zones IV-VIII: a systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2017;30(4):447-456.

13. Collocott SJ, Kelly E, Ellis RF. Optimal early active mobilisation protocol after extensor tendon repairs in zones V and VI: a systematic review of literature. Hand Ther. 2018;23(1):3-18.

1. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. History of HTCC. https://www.htcc.org/consumer-information/about-htcc/history-of-htcc. Accessed November 8, 2019.

2. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

3. Hand Therapy Certification Commission. Passing rates for the CHT exam. https://www.htcc.org/certify/exam-results/passing-rates. Accessed November 8, 2019.

4. Al-Qattan MM. Surgical treatment and results in 17 cases of open lacerations of the extensor hallucis longus tendon. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(4):360-367.

5. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum longus. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_longus. Updated December 8, 2011. Accessed November 8, 2019.

6. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum brevis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_brevis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

7. Coughlin M, Schon L. Disorders of tendons. https://musculoskeletalkey.com/disorders-of-tendons-2/#s0035. Published August 27, 2016. Accessed November 8, 2019.

8. Bronner S, Ojofeitimi S, Rose D. Repair and rehabilitation of extensor hallucis longus and brevis tendon lacerations in a professional dancer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(6):362-370.

9. Wong JC, Daniel JN, Raikin SM. Repair of acute extensor hallucis longus tendon injuries: a retrospective review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7(1):45-51.

10. Wheeless CR. Wheeless’ textbook of orthopaedics: extensor digitorum communis. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/extensor_digitorum_communis. Updated March 4, 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019.

11. Hall B, Lee H, Page R, Rosenwax L, Lee AH. Comparing three postoperative treatment protocols for extensor tendon repair in zones V and VI of the hand. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(5):682-688.

12. Wong AL, Wilson M, Girnary S, Nojoomi M, Acharya S, Paul SM. The optimal orthosis and motion protocol for extensor tendon injury in zones IV-VIII: a systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2017;30(4):447-456.

13. Collocott SJ, Kelly E, Ellis RF. Optimal early active mobilisation protocol after extensor tendon repairs in zones V and VI: a systematic review of literature. Hand Ther. 2018;23(1):3-18.

Orthopedic ambulatory surgery centers beat inpatient services on cost

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and (IPs) with similar levels of postoperative opioid use, according to a new study.

Fanta Waterman, PhD, director of medical and health sciences at Pacira Pharmaceuticals, and colleagues retrospectively published the results of their investigation in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy supplement for the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

Investigators evaluated data from 126,172 commercially insured patients who underwent one of six orthopedic surgical procedures between April 2012 and December 2017. Using the Optum Research Database, they pooled data from patients who had received total knee arthroplasty (TKA), partial knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty (THA), rotator cuff repair (RCR), total shoulder arthroplasty, and lumbar spine fusion.

More than half (51%) of the patients were male, and the patients averaged 58 years of age. Most patients who underwent any of the six surgical interventions had the procedures performed at IPs (68%), while 18% had their operations at HOPDs and 14% were perfomed at ASCs.

TKA, RCR, and THA were the most common procedures performed (32%, 27%, and 20%, respectively). While no fluctuation was observed in the total number of IP procedures performed during 2012-2017, researchers noted a marked increase in ASCs (58%) and HOPDs (15%).

At the 30-day mark, the total all-cause postsurgical costs associated with IPs ($44,566) were more than double that of HOPDs ($20,468) and ASCs ($19,110; P less than .001). Moreover, multivariate adjustment showed that postsurgical costs accrued 30 days after surgery for HOPDs and ASCs were 14% and 27% lower than IPs (P less than .001), respectively.

Additionally, each group exhibited similar evidence of opioid use in the 12-month period prior to undergoing surgery, ranging from 63% to 65%. Postsurgical opioid use among opioid-naive patients was the highest in the HOPD group at 96% prevalence, with IPs and ASCs trailing with 91% and 90% (P less than .001), respectively. However, the postsurgical prevalence of opioid use in patients who had used opioids before surgery was 95% for IPs and HOPDs and 82% for ASCs (P less than .001).

SOURCE: Waterman F et al. AMCP NEXUS 2019, Abstract U12.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and (IPs) with similar levels of postoperative opioid use, according to a new study.

Fanta Waterman, PhD, director of medical and health sciences at Pacira Pharmaceuticals, and colleagues retrospectively published the results of their investigation in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy supplement for the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

Investigators evaluated data from 126,172 commercially insured patients who underwent one of six orthopedic surgical procedures between April 2012 and December 2017. Using the Optum Research Database, they pooled data from patients who had received total knee arthroplasty (TKA), partial knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty (THA), rotator cuff repair (RCR), total shoulder arthroplasty, and lumbar spine fusion.

More than half (51%) of the patients were male, and the patients averaged 58 years of age. Most patients who underwent any of the six surgical interventions had the procedures performed at IPs (68%), while 18% had their operations at HOPDs and 14% were perfomed at ASCs.

TKA, RCR, and THA were the most common procedures performed (32%, 27%, and 20%, respectively). While no fluctuation was observed in the total number of IP procedures performed during 2012-2017, researchers noted a marked increase in ASCs (58%) and HOPDs (15%).

At the 30-day mark, the total all-cause postsurgical costs associated with IPs ($44,566) were more than double that of HOPDs ($20,468) and ASCs ($19,110; P less than .001). Moreover, multivariate adjustment showed that postsurgical costs accrued 30 days after surgery for HOPDs and ASCs were 14% and 27% lower than IPs (P less than .001), respectively.

Additionally, each group exhibited similar evidence of opioid use in the 12-month period prior to undergoing surgery, ranging from 63% to 65%. Postsurgical opioid use among opioid-naive patients was the highest in the HOPD group at 96% prevalence, with IPs and ASCs trailing with 91% and 90% (P less than .001), respectively. However, the postsurgical prevalence of opioid use in patients who had used opioids before surgery was 95% for IPs and HOPDs and 82% for ASCs (P less than .001).

SOURCE: Waterman F et al. AMCP NEXUS 2019, Abstract U12.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and (IPs) with similar levels of postoperative opioid use, according to a new study.

Fanta Waterman, PhD, director of medical and health sciences at Pacira Pharmaceuticals, and colleagues retrospectively published the results of their investigation in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy supplement for the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

Investigators evaluated data from 126,172 commercially insured patients who underwent one of six orthopedic surgical procedures between April 2012 and December 2017. Using the Optum Research Database, they pooled data from patients who had received total knee arthroplasty (TKA), partial knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty (THA), rotator cuff repair (RCR), total shoulder arthroplasty, and lumbar spine fusion.

More than half (51%) of the patients were male, and the patients averaged 58 years of age. Most patients who underwent any of the six surgical interventions had the procedures performed at IPs (68%), while 18% had their operations at HOPDs and 14% were perfomed at ASCs.

TKA, RCR, and THA were the most common procedures performed (32%, 27%, and 20%, respectively). While no fluctuation was observed in the total number of IP procedures performed during 2012-2017, researchers noted a marked increase in ASCs (58%) and HOPDs (15%).

At the 30-day mark, the total all-cause postsurgical costs associated with IPs ($44,566) were more than double that of HOPDs ($20,468) and ASCs ($19,110; P less than .001). Moreover, multivariate adjustment showed that postsurgical costs accrued 30 days after surgery for HOPDs and ASCs were 14% and 27% lower than IPs (P less than .001), respectively.

Additionally, each group exhibited similar evidence of opioid use in the 12-month period prior to undergoing surgery, ranging from 63% to 65%. Postsurgical opioid use among opioid-naive patients was the highest in the HOPD group at 96% prevalence, with IPs and ASCs trailing with 91% and 90% (P less than .001), respectively. However, the postsurgical prevalence of opioid use in patients who had used opioids before surgery was 95% for IPs and HOPDs and 82% for ASCs (P less than .001).

SOURCE: Waterman F et al. AMCP NEXUS 2019, Abstract U12.

REPORTING FROM AMCP NEXUS 2019

Two regenerative techniques prove comparable for repairing knee cartilage

When it comes to repairing knee cartilage, a new study found no significant differences between autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) and autologous chondrocyte implantation with a collagen membrane (ACI-C) as treatment options.

“If the conclusion of the present study stands and is confirmed by further clinical trials, AMIC could be considered an equal alternative to techniques based on chondrocyte transplantation for treatment of cartilage defects of the knee,” wrote Vegard Fossum, MD, of University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, and coauthors, adding that cost and comparative ease might actually make AMIC the preferred choice. The study was published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine.

To evaluate outcomes of the two procedures, the researchers initiated a clinical trial of 41 patients with at least one chondral or osteochondral defect of the distal femur or patella. They were split into two groups: those treated with ACI-C (n = 21) and those treated with AMIC (n = 20). At 1- and 2-year follow-up, patients were assessed via improvements in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), compared with baseline, along with Lysholm and visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores.

After 1 and 2 years, both groups saw improvements from baseline. At 2 years, the AMIC group had an 18.1 change in KOOS, compared with 10.3 in the ACI-C group (P = .17). Two-year improvements on the Lysholm score (19.7 in AMIC, compared with 17.0 in ACI-C, P = .66) and VAS pain score (30.6 in AMIC versus 19.6 in ACI-C, P = .19) were not significantly different. Two patients in the AMIC group had undergone total knee replacement after 2 years, compared with zero in the ACI-C group.

The authors noted their study’s potential limitations, including the small number of patients in each group – the initial plan was to include 80 total – and its broad inclusion criteria. However, since the aim was to compare treatment results and not evaluate effectiveness, they did not consider the broad criteria “a major limitation.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fossum V et al. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Sept 17. doi: 10.1177/2325967119868212.

When it comes to repairing knee cartilage, a new study found no significant differences between autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) and autologous chondrocyte implantation with a collagen membrane (ACI-C) as treatment options.

“If the conclusion of the present study stands and is confirmed by further clinical trials, AMIC could be considered an equal alternative to techniques based on chondrocyte transplantation for treatment of cartilage defects of the knee,” wrote Vegard Fossum, MD, of University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, and coauthors, adding that cost and comparative ease might actually make AMIC the preferred choice. The study was published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine.

To evaluate outcomes of the two procedures, the researchers initiated a clinical trial of 41 patients with at least one chondral or osteochondral defect of the distal femur or patella. They were split into two groups: those treated with ACI-C (n = 21) and those treated with AMIC (n = 20). At 1- and 2-year follow-up, patients were assessed via improvements in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), compared with baseline, along with Lysholm and visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores.

After 1 and 2 years, both groups saw improvements from baseline. At 2 years, the AMIC group had an 18.1 change in KOOS, compared with 10.3 in the ACI-C group (P = .17). Two-year improvements on the Lysholm score (19.7 in AMIC, compared with 17.0 in ACI-C, P = .66) and VAS pain score (30.6 in AMIC versus 19.6 in ACI-C, P = .19) were not significantly different. Two patients in the AMIC group had undergone total knee replacement after 2 years, compared with zero in the ACI-C group.

The authors noted their study’s potential limitations, including the small number of patients in each group – the initial plan was to include 80 total – and its broad inclusion criteria. However, since the aim was to compare treatment results and not evaluate effectiveness, they did not consider the broad criteria “a major limitation.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fossum V et al. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Sept 17. doi: 10.1177/2325967119868212.

When it comes to repairing knee cartilage, a new study found no significant differences between autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) and autologous chondrocyte implantation with a collagen membrane (ACI-C) as treatment options.

“If the conclusion of the present study stands and is confirmed by further clinical trials, AMIC could be considered an equal alternative to techniques based on chondrocyte transplantation for treatment of cartilage defects of the knee,” wrote Vegard Fossum, MD, of University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, and coauthors, adding that cost and comparative ease might actually make AMIC the preferred choice. The study was published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine.

To evaluate outcomes of the two procedures, the researchers initiated a clinical trial of 41 patients with at least one chondral or osteochondral defect of the distal femur or patella. They were split into two groups: those treated with ACI-C (n = 21) and those treated with AMIC (n = 20). At 1- and 2-year follow-up, patients were assessed via improvements in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), compared with baseline, along with Lysholm and visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores.

After 1 and 2 years, both groups saw improvements from baseline. At 2 years, the AMIC group had an 18.1 change in KOOS, compared with 10.3 in the ACI-C group (P = .17). Two-year improvements on the Lysholm score (19.7 in AMIC, compared with 17.0 in ACI-C, P = .66) and VAS pain score (30.6 in AMIC versus 19.6 in ACI-C, P = .19) were not significantly different. Two patients in the AMIC group had undergone total knee replacement after 2 years, compared with zero in the ACI-C group.

The authors noted their study’s potential limitations, including the small number of patients in each group – the initial plan was to include 80 total – and its broad inclusion criteria. However, since the aim was to compare treatment results and not evaluate effectiveness, they did not consider the broad criteria “a major limitation.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fossum V et al. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Sept 17. doi: 10.1177/2325967119868212.

FROM THE ORTHOPAEDIC JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE

Diagnosis Is an Open Book

ANSWER

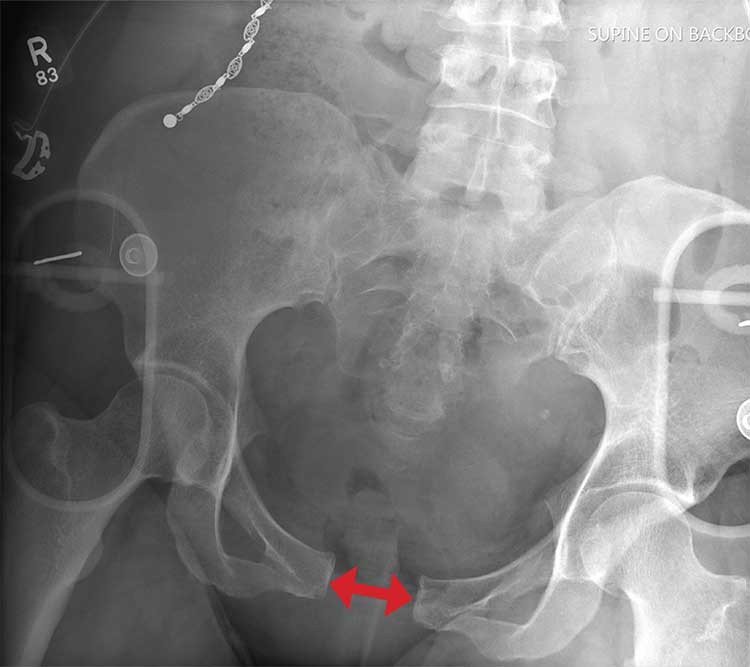

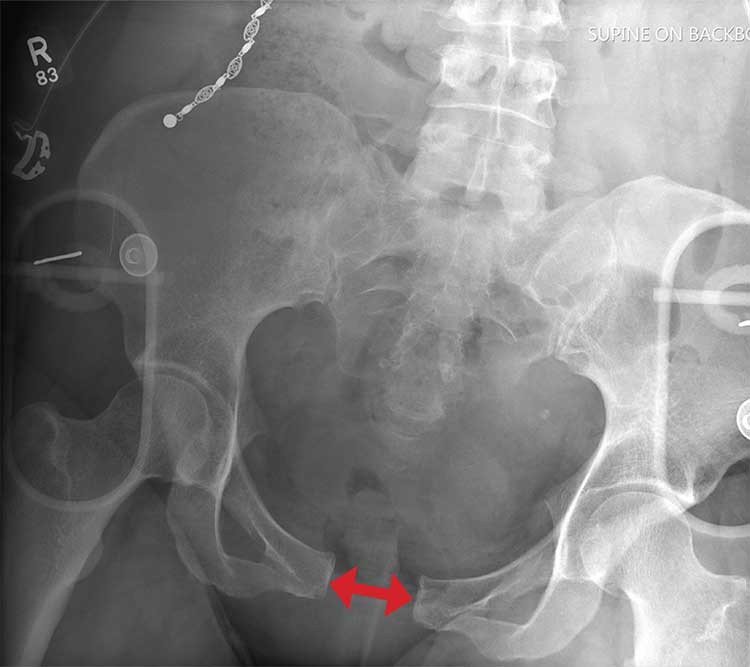

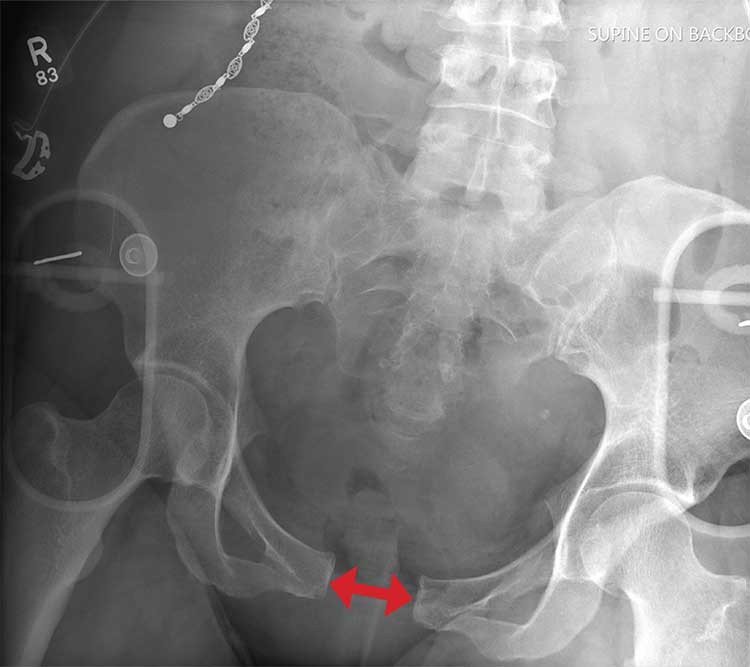

There is evidence of significant widening of the pubic symphysis. This injury results in a disruption of the normal pelvic ring. Such fractures are typically referred to as open-book pelvic fractures. Usually the result of high-energy trauma, they can also be associated with bladder and/or vascular injuries.

Orthopedics was consulted for management of this injury. Prompt stabilization with an external binder may help reduce complications. The patient will ultimately require some form of external or internal fixation.

ANSWER

There is evidence of significant widening of the pubic symphysis. This injury results in a disruption of the normal pelvic ring. Such fractures are typically referred to as open-book pelvic fractures. Usually the result of high-energy trauma, they can also be associated with bladder and/or vascular injuries.

Orthopedics was consulted for management of this injury. Prompt stabilization with an external binder may help reduce complications. The patient will ultimately require some form of external or internal fixation.

ANSWER

There is evidence of significant widening of the pubic symphysis. This injury results in a disruption of the normal pelvic ring. Such fractures are typically referred to as open-book pelvic fractures. Usually the result of high-energy trauma, they can also be associated with bladder and/or vascular injuries.

Orthopedics was consulted for management of this injury. Prompt stabilization with an external binder may help reduce complications. The patient will ultimately require some form of external or internal fixation.

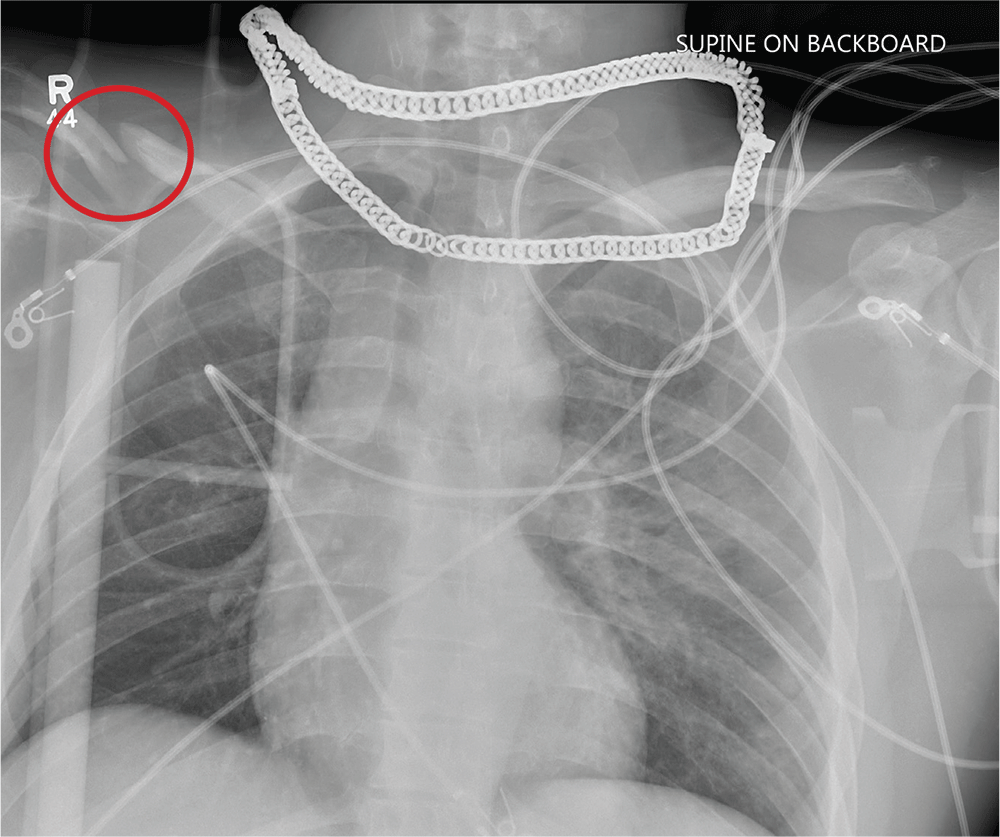

A 50-year-old woman is airlifted to your facility from the scene of an accident. She was riding a motorcycle that was struck by a car at a presumed high rate of speed. There was reportedly a brief loss of consciousness, although when the first responders arrived, the patient was complaining of pain in both her hands and wrists, as well as severe hip pain.

The patient was hemodynamically stable during transport. Blood pressure on arrival is 130/78 mm Hg, with a heart rate of 90 beats/min. Her O2 saturation is 97% with supplemental oxygen administered by nasal cannula.

As you begin your primary survey, the patient responds appropriately to you: She tells you her name and where she is from. Her medical history is significant for migraines, and her surgical history is significant for a prior cholecystectomy and tubal ligation. Primary exam overall appears normal, except for obvious deformities in both wrists.

As you begin your secondary survey, the radiology technicians obtain portable chest and pelvis radiographs (latter shown). What is your impression?

Tranexamic acid does not increase complications in high-risk joint replacement surgery patients

A study has found that administering tranexamic acid (TXA) to high-risk patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) does not increase their odds of adverse outcomes.

“The inclusion of high-risk patients in our study increases the generalizability of our findings and is consistent with the previous studies that showed no increase in complications when TXA is administered to TJA patients,” wrote Steven B. Porter, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

To determine the safety of TXA in patients at risk for thrombotic complications, the researchers investigated 38,220 patients who underwent total knee or total hip arthroplasty between 2011 and 2017 at the Mayo Clinic. Of those patients, 20,501 (54%) patients received TXA during their operation and 17,719 (46%) did not. Overall, 8,877 were classified as “high-risk” cases, which meant they had one or more cardiovascular disease or thromboembolic event before surgery.

After multivariable analysis, high risk-patients who received TXA had no significant difference in adverse outcome odds, compared with high-risk patients who did not receive TXA (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.18). After 90 days, high-risk patients who did not receive TXA were more likely than those who received TXA to experience deep vein thrombosis (2.3% vs 0.8%, P less than .001), pulmonary embolism (1.7% vs 1.0%, P less than .001), cerebrovascular accident (0.8% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001), or death (0.5% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001).

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including a higher baseline incidence of risk factors in high-risk patients who did not receive TXA, compared with high-risk patients who did, which could have led to that group being “self-selected” to not receive TXA. In addition, all medical histories and rates of complications were based on ICD codes, which may have been inaccurate and therefore led to mischaracterized risk or miscoded postoperative complications.

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Porter SB et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Aug 17. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.015.

A study has found that administering tranexamic acid (TXA) to high-risk patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) does not increase their odds of adverse outcomes.

“The inclusion of high-risk patients in our study increases the generalizability of our findings and is consistent with the previous studies that showed no increase in complications when TXA is administered to TJA patients,” wrote Steven B. Porter, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

To determine the safety of TXA in patients at risk for thrombotic complications, the researchers investigated 38,220 patients who underwent total knee or total hip arthroplasty between 2011 and 2017 at the Mayo Clinic. Of those patients, 20,501 (54%) patients received TXA during their operation and 17,719 (46%) did not. Overall, 8,877 were classified as “high-risk” cases, which meant they had one or more cardiovascular disease or thromboembolic event before surgery.

After multivariable analysis, high risk-patients who received TXA had no significant difference in adverse outcome odds, compared with high-risk patients who did not receive TXA (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.18). After 90 days, high-risk patients who did not receive TXA were more likely than those who received TXA to experience deep vein thrombosis (2.3% vs 0.8%, P less than .001), pulmonary embolism (1.7% vs 1.0%, P less than .001), cerebrovascular accident (0.8% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001), or death (0.5% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001).

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including a higher baseline incidence of risk factors in high-risk patients who did not receive TXA, compared with high-risk patients who did, which could have led to that group being “self-selected” to not receive TXA. In addition, all medical histories and rates of complications were based on ICD codes, which may have been inaccurate and therefore led to mischaracterized risk or miscoded postoperative complications.

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Porter SB et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Aug 17. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.015.

A study has found that administering tranexamic acid (TXA) to high-risk patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) does not increase their odds of adverse outcomes.

“The inclusion of high-risk patients in our study increases the generalizability of our findings and is consistent with the previous studies that showed no increase in complications when TXA is administered to TJA patients,” wrote Steven B. Porter, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

To determine the safety of TXA in patients at risk for thrombotic complications, the researchers investigated 38,220 patients who underwent total knee or total hip arthroplasty between 2011 and 2017 at the Mayo Clinic. Of those patients, 20,501 (54%) patients received TXA during their operation and 17,719 (46%) did not. Overall, 8,877 were classified as “high-risk” cases, which meant they had one or more cardiovascular disease or thromboembolic event before surgery.

After multivariable analysis, high risk-patients who received TXA had no significant difference in adverse outcome odds, compared with high-risk patients who did not receive TXA (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.18). After 90 days, high-risk patients who did not receive TXA were more likely than those who received TXA to experience deep vein thrombosis (2.3% vs 0.8%, P less than .001), pulmonary embolism (1.7% vs 1.0%, P less than .001), cerebrovascular accident (0.8% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001), or death (0.5% vs. 0.4%, P less than .001).

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including a higher baseline incidence of risk factors in high-risk patients who did not receive TXA, compared with high-risk patients who did, which could have led to that group being “self-selected” to not receive TXA. In addition, all medical histories and rates of complications were based on ICD codes, which may have been inaccurate and therefore led to mischaracterized risk or miscoded postoperative complications.

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Porter SB et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Aug 17. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.015.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ARTHROPLASTY

Key clinical point: Administering tranexamic acid to high-risk patients undergoing joint replacement surgery does not increase the odds of adverse outcomes.

Major finding: After multivariable analysis, high-risk patients who received tranexamic acid had no significant difference in adverse outcome odds, compared with high-risk patients who did not receive tranexamic acid (odd ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.18).

Study details: A retrospective case-control study of 38,220 patients who underwent primary total knee or total hip arthroplasty between 2011 and 2017.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic’s Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Porter SB et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Aug 17. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.015.

Delaying revision knee replacement increases the odds of infection

According to a study on patients undergoing revision knee replacement, a delay of more than 24 hours between hospital admission and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for periprosthetic fracture (PPF) led to increased odds of complications such as surgical site and urinary tract infections.

“Although this association is an important finding, the confounding factors that cause delay to surgery must be elucidated in non-database studies,” wrote Venkat Boddapati, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthroplasty Today.

To assess the best time for revision TKA after PPF of the knee, the researchers analyzed data from 484 patients who underwent another TKA from 2005 to 2016. Of those patients, 377 (78%) had expedited surgery – defined as less than or equal to 24 hours from hospital admission – and 107 (22%) had non-expedited surgery. Non-expedited patients averaged 3.2 days from admission to surgery.

After multivariate analysis, non-expedited patients had more complications overall, compared with expedited patients (odds ratio 2.35, P = .037). They also had comparative increases in surgical site infections (OR 12.87, P = .029), urinary tract infections (OR 10.46, P = .048), non-home discharge (OR 4.27, P less than .001), and blood transfusions (OR 4.53, P less than .001). The two groups saw no statistical difference in mortality.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including an inability to assess complications beyond 30 days after surgery, which may affect tracking longer-term outcomes such as mortality. In addition, they were only able to classify surgery as expedited or non-expedited based on when the patient was admitted to the hospital, not the time since their injury. Finally, they lacked “relevant variables that may have contributed to this analysis,” including the type of fracture and the revision implants used.

Three authors reported being paid consultants for, and receiving research support from, several medical companies. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Boddapati V et al. Arthroplast Today. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.05.002.

According to a study on patients undergoing revision knee replacement, a delay of more than 24 hours between hospital admission and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for periprosthetic fracture (PPF) led to increased odds of complications such as surgical site and urinary tract infections.

“Although this association is an important finding, the confounding factors that cause delay to surgery must be elucidated in non-database studies,” wrote Venkat Boddapati, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthroplasty Today.

To assess the best time for revision TKA after PPF of the knee, the researchers analyzed data from 484 patients who underwent another TKA from 2005 to 2016. Of those patients, 377 (78%) had expedited surgery – defined as less than or equal to 24 hours from hospital admission – and 107 (22%) had non-expedited surgery. Non-expedited patients averaged 3.2 days from admission to surgery.

After multivariate analysis, non-expedited patients had more complications overall, compared with expedited patients (odds ratio 2.35, P = .037). They also had comparative increases in surgical site infections (OR 12.87, P = .029), urinary tract infections (OR 10.46, P = .048), non-home discharge (OR 4.27, P less than .001), and blood transfusions (OR 4.53, P less than .001). The two groups saw no statistical difference in mortality.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including an inability to assess complications beyond 30 days after surgery, which may affect tracking longer-term outcomes such as mortality. In addition, they were only able to classify surgery as expedited or non-expedited based on when the patient was admitted to the hospital, not the time since their injury. Finally, they lacked “relevant variables that may have contributed to this analysis,” including the type of fracture and the revision implants used.

Three authors reported being paid consultants for, and receiving research support from, several medical companies. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Boddapati V et al. Arthroplast Today. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.05.002.

According to a study on patients undergoing revision knee replacement, a delay of more than 24 hours between hospital admission and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for periprosthetic fracture (PPF) led to increased odds of complications such as surgical site and urinary tract infections.

“Although this association is an important finding, the confounding factors that cause delay to surgery must be elucidated in non-database studies,” wrote Venkat Boddapati, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and coauthors. The study was published in Arthroplasty Today.

To assess the best time for revision TKA after PPF of the knee, the researchers analyzed data from 484 patients who underwent another TKA from 2005 to 2016. Of those patients, 377 (78%) had expedited surgery – defined as less than or equal to 24 hours from hospital admission – and 107 (22%) had non-expedited surgery. Non-expedited patients averaged 3.2 days from admission to surgery.

After multivariate analysis, non-expedited patients had more complications overall, compared with expedited patients (odds ratio 2.35, P = .037). They also had comparative increases in surgical site infections (OR 12.87, P = .029), urinary tract infections (OR 10.46, P = .048), non-home discharge (OR 4.27, P less than .001), and blood transfusions (OR 4.53, P less than .001). The two groups saw no statistical difference in mortality.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including an inability to assess complications beyond 30 days after surgery, which may affect tracking longer-term outcomes such as mortality. In addition, they were only able to classify surgery as expedited or non-expedited based on when the patient was admitted to the hospital, not the time since their injury. Finally, they lacked “relevant variables that may have contributed to this analysis,” including the type of fracture and the revision implants used.

Three authors reported being paid consultants for, and receiving research support from, several medical companies. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Boddapati V et al. Arthroplast Today. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.05.002.

FROM ARTHROPLASTY TODAY

Cross at the Green, Not in Between

ANSWER

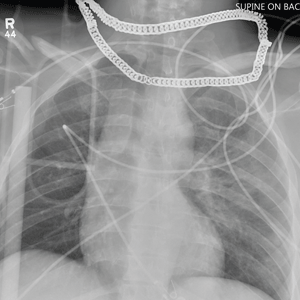

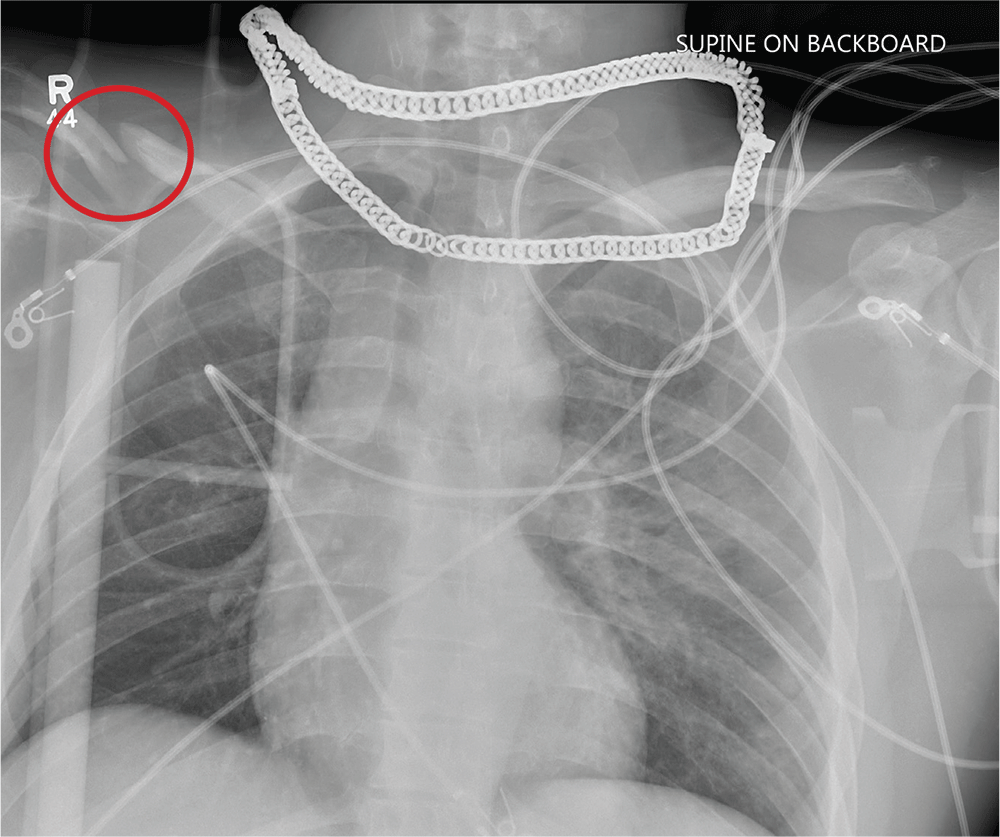

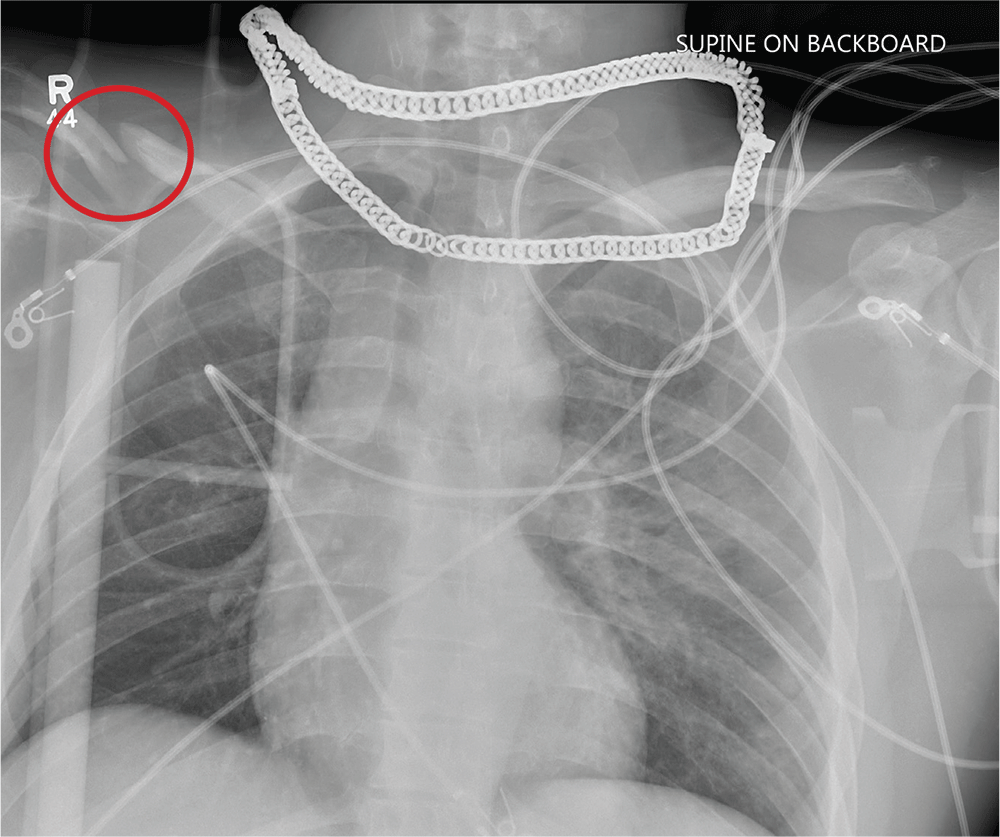

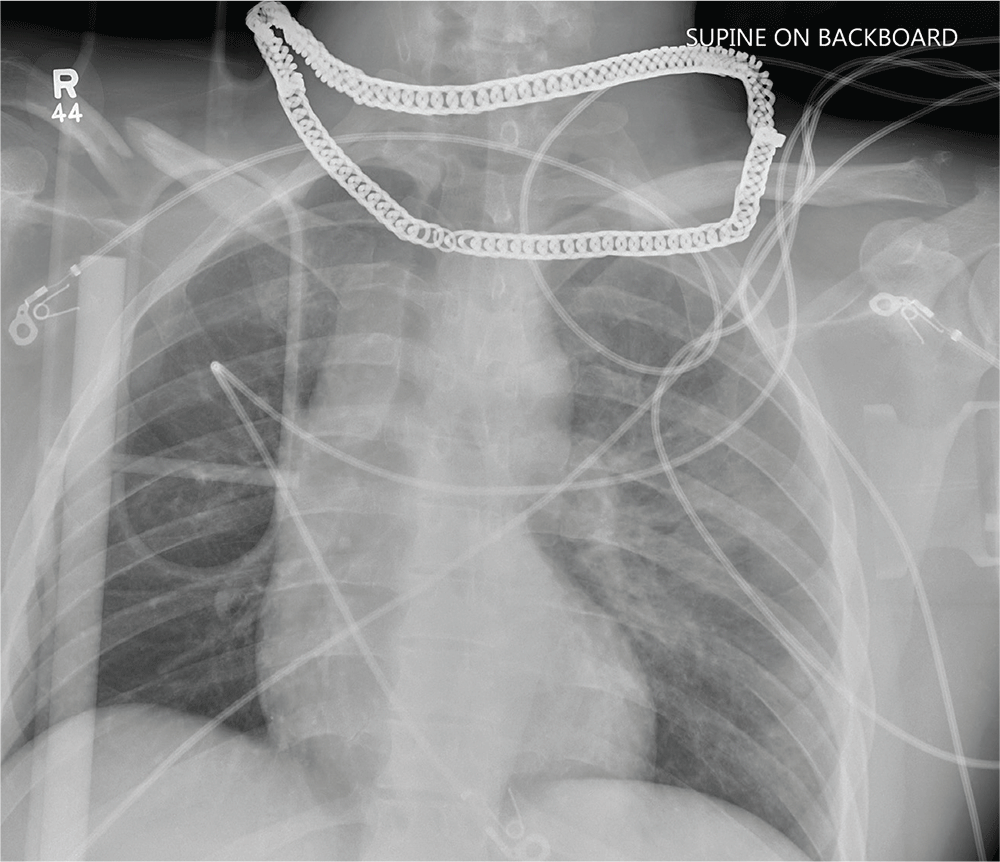

Aside from the usual artifacts from placement on a backboard and from the presence of monitoring devices and wires, the radiograph shows a displaced fracture of the right clavicle. No other significant abnormalities are present.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with multiple orthopedic injuries, and orthopedics was called to evaluate and manage accordingly.

ANSWER

Aside from the usual artifacts from placement on a backboard and from the presence of monitoring devices and wires, the radiograph shows a displaced fracture of the right clavicle. No other significant abnormalities are present.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with multiple orthopedic injuries, and orthopedics was called to evaluate and manage accordingly.

ANSWER

Aside from the usual artifacts from placement on a backboard and from the presence of monitoring devices and wires, the radiograph shows a displaced fracture of the right clavicle. No other significant abnormalities are present.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with multiple orthopedic injuries, and orthopedics was called to evaluate and manage accordingly.

A 25-year-old man is brought to your facility by EMS transport following an accident while riding a bicycle. Witnesses say he was hit by a car when he suddenly tried to cross a busy intersection. They also report that he was not wearing a helmet and that he was thrown off the bike, landing several feet away.

Initial survey reveals a male who is arousable but nonverbal, just moaning and groaning. There are obvious deformities in both lower extremities and the right upper extremity. The patient’s blood pressure is 100/50 mm Hg and his heart rate, 130 beats/min. Pulse oximetry shows his O2 saturation to be 95% with 100% oxygen via nonrebreather mask. His pupils are equal and reactive bilaterally. Heart and lungs sound clear. Abdomen is soft.

While you continue examining the patient and begin your secondary survey, a portable chest radiograph is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

Be alert to deep SSI risk after knee surgery

Deep surgical-site infections (SSIs) and septic arthritis are not uncommon after the surgeries for periarticular knee fractures, a meta-analysis of existing research found.