User login

Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration: A Rare Reaction

Localized reactions and transient pain at the site of vaccine administration are frequent and well-described occurrences that are typically short-lived and mild in nature. The most common findings at the injection site are soreness, erythema, and edema.1 Although less common, generalized shoulder dysfunction after vaccine administration also has been reported. Bodor and colleagues described a peri-articular inflammatory response that led to shoulder pain and weakness.2 A single case report by Kuether and colleagues described atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after H1N1 vaccine administration in the deltoid.3 In 2010, shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) was described by Atanasoff and colleagues as the rapid onset of shoulder pain and dysfunction persisting as a complication of deltoid muscle vaccination in a case series of 13 patients.4 In our report, we present a case of an active-duty male eventually diagnosed with SIRVA after influenza vaccination and discuss factors that may prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty male presented to the Allergy clinic for evaluation of persistent left shoulder pain and decreased range of motion (ROM) following influenza vaccination 4 months prior. He reported a history of chronic low back and right shoulder pain. Although the patient had a traumatic injury to his right shoulder, which was corrected with surgery, he had no surgeries on the left shoulder. He reported no prior pain or known trauma to his left shoulder. He had no personal or family history of atopy or vaccine reactions.

The patient weighed 91 kg and received an intramuscular (IM) quadrivalent influenza vaccine with a 25-gauge, 1-inch needle during a mass influenza immunization. He recalled that the site of vaccination was slightly more than 3 cm below the top of the shoulder in a region correlating to the left deltoid. The vaccine was administered while he was standing with his arm extended, adducted, and internally rotated. The patient experienced intense pain immediately after the vaccination and noted decreased ROM. Initially, he dismissed the pain and decreased ROM as routine but sought medical attention when there was no improvement after 3 weeks.

Six weeks after the onset of symptoms, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed tendinopathy of the left distal subscapularis, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and teres minor tendon. These findings were suggestive of a small partial thickness tear of the supraspinatus (Figure 1), possible calcific tendinopathy of the distal teres minor (Figure 2), and underlying humeral head edema (Figure 3). The patient was evaluated by Orthopedics and experienced no relief from ibuprofen, celecoxib, and a steroid/lidocaine intra-articular injection. Laboratory studies included an unremarkable complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. He was diagnosed with SIRVA and continued in physical therapy with incomplete resolution of symptoms 6 months postvaccination.

Discussion

According to a 2018 report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, local reactions following immunizations are seen in up to 80% of administered vaccine doses.1 While most of these reactions are mild, transient, cutaneous reactions, rarely these also may persist and impact quality of life significantly. SIRVA is one such process that can lead to persistent musculoskeletal dysfunction. SIRVA presents as shoulder pain and limited ROM that occurs after the administration of an injectable vaccine. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine determined that evidence supported a causal relationship between vaccine administration and deltoid bursitis.5

In 2017, SIRVA was included in the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), a federal program that can provide compensation to individuals injured by certain vaccines.6 A diagnosis of SIRVA can be considered in patients who experience pain within 48 hours of vaccination, have no prior history of pain or dysfunction of the affected shoulder prior to vaccine administration, and have symptoms limited to the shoulder in which the vaccine was administered where no other abnormality is present to explain these symptoms (eg, brachial neuritis, other neuropathy). Currently, patients with back pain or musculoskeletal complaints that do not include the shoulder following deltoid vaccination do not meet the reporting criteria for SIRVA in the VICP.6

The exact prevalence or incidence of SIRVA is unknown. In a 2017 systematic review of the literature and the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System database, Martín Arias and colleagues found 45 cases of new onset, unilateral shoulder dysfunction without associated neuropathy or autoimmune conditions following vaccine administration. They noted a female to male predominance (71.1% vs 28.9%) with a mean age of 53.6 years (range 22-89 y). Most of the cases occurred following influenza vaccine (62%); pneumococcal vaccine was the next most common (13%).7 Shoulder injury also has been reported after tetanus-diphtheria toxoids, human papilloma virus, and hepatitis A virus vaccines.4,7 The review noted that all patients had onset of pain within the first week following vaccination with the majority (81%) having pain in the first 24 hours. Two cases found in the Spanish database had pain onset 2 months postvaccination.7 Atanasoff and colleagues found that 93% of patients had pain onset within 24 hours of vaccination with 54% reporting immediate pain.4

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) tracks reports of shoulder dysfunction following certain vaccinations, but the system is unable to establish causality. According to VAERS reporting, between 2010 and 2016, there were 1006 possible reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV) compared with an estimated 130 million doses of IIV given each influenza season in the US.8

Bodor and Montalvo postulated that vaccine antigen was being over penetrated into the synovial space of the shoulder, as the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa is located a mere 0.8 to 1.6 cm below the skin surface in patients with healthy body mass index.2 Atanasoff and colleagues expounded that antibodies from previous vaccination or natural infection may then form antigen-antibody complexes, creating prolonged local immune and inflammatory responses leading to bursitis or tendonitis.4 Martín Arias and colleagues hypothesized that improper injection technique, including wrong insertion angle, incorrect needle type/size, and failure to account for the patient’s physical characteristics were the most likely causes of SIRVA.7

Proper vaccine administration ensures that vaccinations are delivered in a safe and efficacious manner. Safe vaccination practices include the use of trained personnel who receive comprehensive, competency-based training regarding vaccine administration.1 Aspiration prior to an injection is a practice that has not been evaluated fully. Given that the 2 routinely recommended locations for IM vaccines (deltoid muscle in adults or vastus lateralis muscle in infants) lack large blood vessels, the practice of aspiration prior to an IM vaccine is not currently deemed necessary.1 Additional safe vaccine practices include the selection of appropriate needle length for muscle penetration and that anatomic landmarks determine the location of vaccination.1 Despite this, in a survey of 100 medical professionals, half could not name any structure at risk from improper deltoid vaccination technique.9

Cook and colleagues used anthropomorphic data to evaluate the potential for injury to the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa and/or the axillary nerve.10 Based on these data, they recommended safe IM vaccine administration can be assured by using the midpoint of the deltoid muscle located midway between the acromion and deltoid tuberosity with the arm abducted to 60°.10,11 In 46% of SIRVA cases described by Atanasoff and colleagues, patients reported that the vaccine was administered “too high.”4 The study also recommended that the clinician and the patient be in the seated position to ensure proper needle angle and location of administration.4 For most adults, a 1-inch needle is appropriate for vaccine administration in the deltoid; however, in females weighing < 70 kg and males < 75 kg, a 5/8-inch needle is recommended to avoid injury.7

Our 91-kg patient was appropriately administered his vaccine with a 1-inch needle. As he experienced immediate pain, it is unlikely that his symptoms were due to an immune-mediated process, as this would not be expected to occur immediately. Improper location of vaccine administration is a proposed mechanism of injury for our patient, though this cannot be confirmed by history alone. His prior history of traumatic injury to the opposite shoulder could represent a confounding factor as no prior imaging was available for the vaccine-affected shoulder. A preexisting shoulder abnormality or injury cannot be completely excluded, and it is possible that an underlying prior shoulder injury was aggravated postvaccination.

Evaluation and Treatment

There is no standardized approach for the evaluation of SIRVA to date. Awareness of SIRVA and a high index of suspicion are necessary to evaluate patients with shoulder concerns postvaccination. Laboratory evaluation should be considered to evaluate for other potential diagnoses (eg, infection, rheumatologic concerns). Routine X-rays are not helpful in cases of SIRVA. Ultrasound may be considered as it can show bursa abnormalities consistent with bursitis.2 MRI of the affected shoulder may provide improved diagnostic capability if SIRVA is suspected. MRI findings vary but include intraosseous edema, bursitis, tendonitis, and rotator cuff tears.4,12 Complete rotator cuff tears were found in 15% of cases reviewed by Atanasoff and colleagues.4 While there is no recommended timing for MRI, 63% of MRIs were performed within 3 months of symptom onset.4 As SIRVA is not a neurologic injury, nerve conduction, electromyographic studies, and neurologic evaluation or testing are expected to be normal.

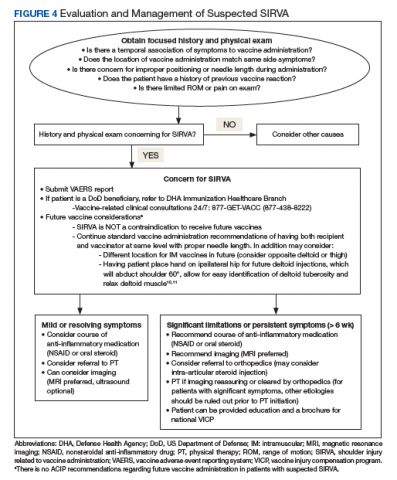

Treatment of SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder injuries typically have involved pain management (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents), intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy, though some patients never experience complete resolution of symptoms.2,4,7 Both patients with vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction described by Bodor and colleagues improved after intra-articular triamcinolone injections, with up to 3 injections before complete resolution of pain in one patient.2 Orthopedics evaluation may need to be considered for persistent symptoms. According to Atanasoff and colleagues, most patients were symptomatic for at least 6 months, and complete recovery was seen in less than one-third of patients.4 Although the development of SIRVA is not a contraindication to future doses of the presumed causative vaccine, subsequent vaccination should include careful consideration of other administration sites if possible (eg, vastus lateralis may be used for IM injections in adults) (Figure 4).

Reporting

A diagnosis or concern for SIRVA also should be reported to the VAERS, the national database established in order to detect possible safety problems with US-licensed vaccines. VAERS reports can be submitted by anyone with concerns for vaccine adverse reactions, including patients, caregivers, and health care professionals at vaers.hhs.gov/reportevent.html. Additional information regarding VICP can be obtained at www.hrsa.gov/vaccine-compensation/index.html.

Military-Specific Issues

The military values readiness, which includes ensuring that active-duty members remain up-to-date on life-saving vaccinations. Immunization is of critical importance to mobility and success of the overall mission. Mobility processing lines where immunizations can be provided to multiple active-duty members can be a successful strategy for mass immunizations. Although the quick administration of immunizations maintains readiness and provides a medically necessary service, it also may increase the chances of incorrect vaccine placement in the deltoid, causing long-term shoulder immobility that may impact a service member’s retainability. The benefits of mobility processing lines can continue to outweigh the risks of immunization administration by ensuring proper staff training, seating both the administrator and recipient of vaccination, and selecting a proper needle length and site of administration specific to each recipient.

Conclusion

Correct administration of vaccines is of utmost importance in preventing SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder dysfunctions. Proper staff training and refresher training can help prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries. Additionally, clinicians should be aware of this potential complication and maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with postvaccination shoulder complaints.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-admin.html. Published 2015. Accessed June 3, 2019.

2. Bodor M, Montalvo E. Vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction. Vaccine. 2007;25(4):585-587.

3. Kuether G, Dietrich B, Smith T, Peter C, Gruessner S. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after influenza A-(H1N1) v-2009 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29(40):6830-6833.

4. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, Johann-Liang R. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28(51):8049-8052.

5. Institute of Medicine. Adverse effects of vaccines: evidence and causality. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2011/Adverse-Effects-of-Vaccines-Evidence-and-Causality/Vaccine-report-brief-FINAL.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed June 3, 2019.

6. Health Resources and Services Administration, Health and Human Services Administration. National vaccine injury compensation program: revisions to the vaccine injury table. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/19/2017-00701/national-vaccine-injury-compensation-program-revisions-to-the-vaccine-injury-table. Published January 19, 2017. Accessed June 3, 2019.

7. Martín Arias LH, Sanz Fadrique R, Sáinz Gil M, Salgueiro-Vazquez ME. Risk of bursitis and other injuries and dysfunctions of the shoulder following vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):4870-4876.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2010-2016. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/57624. Published January 4, 2018. Accessed June 3, 2019.

9. McGarvey MA, Hooper AC. The deltoid intramuscular injection site in the adult. Current practice among general practitioners and practice nurses. Ir Med J. 2005;98(4):105-107.

10. Cook IF. An evidence based protocol for the prevention of upper arm injury related to vaccine administration (UAIRVA). Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(8):845-848.

11. Cook IF. Best vaccination practice and medically attended injection site events following deltoid intramuscular injection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(5):1184-1191.

12. Okur G, Chaney KA, Lomasney LM. Magnetic resonance imaging of abnormal shoulder pain following influenza vaccination. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(9):1325-1331.

Localized reactions and transient pain at the site of vaccine administration are frequent and well-described occurrences that are typically short-lived and mild in nature. The most common findings at the injection site are soreness, erythema, and edema.1 Although less common, generalized shoulder dysfunction after vaccine administration also has been reported. Bodor and colleagues described a peri-articular inflammatory response that led to shoulder pain and weakness.2 A single case report by Kuether and colleagues described atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after H1N1 vaccine administration in the deltoid.3 In 2010, shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) was described by Atanasoff and colleagues as the rapid onset of shoulder pain and dysfunction persisting as a complication of deltoid muscle vaccination in a case series of 13 patients.4 In our report, we present a case of an active-duty male eventually diagnosed with SIRVA after influenza vaccination and discuss factors that may prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty male presented to the Allergy clinic for evaluation of persistent left shoulder pain and decreased range of motion (ROM) following influenza vaccination 4 months prior. He reported a history of chronic low back and right shoulder pain. Although the patient had a traumatic injury to his right shoulder, which was corrected with surgery, he had no surgeries on the left shoulder. He reported no prior pain or known trauma to his left shoulder. He had no personal or family history of atopy or vaccine reactions.

The patient weighed 91 kg and received an intramuscular (IM) quadrivalent influenza vaccine with a 25-gauge, 1-inch needle during a mass influenza immunization. He recalled that the site of vaccination was slightly more than 3 cm below the top of the shoulder in a region correlating to the left deltoid. The vaccine was administered while he was standing with his arm extended, adducted, and internally rotated. The patient experienced intense pain immediately after the vaccination and noted decreased ROM. Initially, he dismissed the pain and decreased ROM as routine but sought medical attention when there was no improvement after 3 weeks.

Six weeks after the onset of symptoms, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed tendinopathy of the left distal subscapularis, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and teres minor tendon. These findings were suggestive of a small partial thickness tear of the supraspinatus (Figure 1), possible calcific tendinopathy of the distal teres minor (Figure 2), and underlying humeral head edema (Figure 3). The patient was evaluated by Orthopedics and experienced no relief from ibuprofen, celecoxib, and a steroid/lidocaine intra-articular injection. Laboratory studies included an unremarkable complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. He was diagnosed with SIRVA and continued in physical therapy with incomplete resolution of symptoms 6 months postvaccination.

Discussion

According to a 2018 report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, local reactions following immunizations are seen in up to 80% of administered vaccine doses.1 While most of these reactions are mild, transient, cutaneous reactions, rarely these also may persist and impact quality of life significantly. SIRVA is one such process that can lead to persistent musculoskeletal dysfunction. SIRVA presents as shoulder pain and limited ROM that occurs after the administration of an injectable vaccine. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine determined that evidence supported a causal relationship between vaccine administration and deltoid bursitis.5

In 2017, SIRVA was included in the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), a federal program that can provide compensation to individuals injured by certain vaccines.6 A diagnosis of SIRVA can be considered in patients who experience pain within 48 hours of vaccination, have no prior history of pain or dysfunction of the affected shoulder prior to vaccine administration, and have symptoms limited to the shoulder in which the vaccine was administered where no other abnormality is present to explain these symptoms (eg, brachial neuritis, other neuropathy). Currently, patients with back pain or musculoskeletal complaints that do not include the shoulder following deltoid vaccination do not meet the reporting criteria for SIRVA in the VICP.6

The exact prevalence or incidence of SIRVA is unknown. In a 2017 systematic review of the literature and the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System database, Martín Arias and colleagues found 45 cases of new onset, unilateral shoulder dysfunction without associated neuropathy or autoimmune conditions following vaccine administration. They noted a female to male predominance (71.1% vs 28.9%) with a mean age of 53.6 years (range 22-89 y). Most of the cases occurred following influenza vaccine (62%); pneumococcal vaccine was the next most common (13%).7 Shoulder injury also has been reported after tetanus-diphtheria toxoids, human papilloma virus, and hepatitis A virus vaccines.4,7 The review noted that all patients had onset of pain within the first week following vaccination with the majority (81%) having pain in the first 24 hours. Two cases found in the Spanish database had pain onset 2 months postvaccination.7 Atanasoff and colleagues found that 93% of patients had pain onset within 24 hours of vaccination with 54% reporting immediate pain.4

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) tracks reports of shoulder dysfunction following certain vaccinations, but the system is unable to establish causality. According to VAERS reporting, between 2010 and 2016, there were 1006 possible reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV) compared with an estimated 130 million doses of IIV given each influenza season in the US.8

Bodor and Montalvo postulated that vaccine antigen was being over penetrated into the synovial space of the shoulder, as the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa is located a mere 0.8 to 1.6 cm below the skin surface in patients with healthy body mass index.2 Atanasoff and colleagues expounded that antibodies from previous vaccination or natural infection may then form antigen-antibody complexes, creating prolonged local immune and inflammatory responses leading to bursitis or tendonitis.4 Martín Arias and colleagues hypothesized that improper injection technique, including wrong insertion angle, incorrect needle type/size, and failure to account for the patient’s physical characteristics were the most likely causes of SIRVA.7

Proper vaccine administration ensures that vaccinations are delivered in a safe and efficacious manner. Safe vaccination practices include the use of trained personnel who receive comprehensive, competency-based training regarding vaccine administration.1 Aspiration prior to an injection is a practice that has not been evaluated fully. Given that the 2 routinely recommended locations for IM vaccines (deltoid muscle in adults or vastus lateralis muscle in infants) lack large blood vessels, the practice of aspiration prior to an IM vaccine is not currently deemed necessary.1 Additional safe vaccine practices include the selection of appropriate needle length for muscle penetration and that anatomic landmarks determine the location of vaccination.1 Despite this, in a survey of 100 medical professionals, half could not name any structure at risk from improper deltoid vaccination technique.9

Cook and colleagues used anthropomorphic data to evaluate the potential for injury to the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa and/or the axillary nerve.10 Based on these data, they recommended safe IM vaccine administration can be assured by using the midpoint of the deltoid muscle located midway between the acromion and deltoid tuberosity with the arm abducted to 60°.10,11 In 46% of SIRVA cases described by Atanasoff and colleagues, patients reported that the vaccine was administered “too high.”4 The study also recommended that the clinician and the patient be in the seated position to ensure proper needle angle and location of administration.4 For most adults, a 1-inch needle is appropriate for vaccine administration in the deltoid; however, in females weighing < 70 kg and males < 75 kg, a 5/8-inch needle is recommended to avoid injury.7

Our 91-kg patient was appropriately administered his vaccine with a 1-inch needle. As he experienced immediate pain, it is unlikely that his symptoms were due to an immune-mediated process, as this would not be expected to occur immediately. Improper location of vaccine administration is a proposed mechanism of injury for our patient, though this cannot be confirmed by history alone. His prior history of traumatic injury to the opposite shoulder could represent a confounding factor as no prior imaging was available for the vaccine-affected shoulder. A preexisting shoulder abnormality or injury cannot be completely excluded, and it is possible that an underlying prior shoulder injury was aggravated postvaccination.

Evaluation and Treatment

There is no standardized approach for the evaluation of SIRVA to date. Awareness of SIRVA and a high index of suspicion are necessary to evaluate patients with shoulder concerns postvaccination. Laboratory evaluation should be considered to evaluate for other potential diagnoses (eg, infection, rheumatologic concerns). Routine X-rays are not helpful in cases of SIRVA. Ultrasound may be considered as it can show bursa abnormalities consistent with bursitis.2 MRI of the affected shoulder may provide improved diagnostic capability if SIRVA is suspected. MRI findings vary but include intraosseous edema, bursitis, tendonitis, and rotator cuff tears.4,12 Complete rotator cuff tears were found in 15% of cases reviewed by Atanasoff and colleagues.4 While there is no recommended timing for MRI, 63% of MRIs were performed within 3 months of symptom onset.4 As SIRVA is not a neurologic injury, nerve conduction, electromyographic studies, and neurologic evaluation or testing are expected to be normal.

Treatment of SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder injuries typically have involved pain management (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents), intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy, though some patients never experience complete resolution of symptoms.2,4,7 Both patients with vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction described by Bodor and colleagues improved after intra-articular triamcinolone injections, with up to 3 injections before complete resolution of pain in one patient.2 Orthopedics evaluation may need to be considered for persistent symptoms. According to Atanasoff and colleagues, most patients were symptomatic for at least 6 months, and complete recovery was seen in less than one-third of patients.4 Although the development of SIRVA is not a contraindication to future doses of the presumed causative vaccine, subsequent vaccination should include careful consideration of other administration sites if possible (eg, vastus lateralis may be used for IM injections in adults) (Figure 4).

Reporting

A diagnosis or concern for SIRVA also should be reported to the VAERS, the national database established in order to detect possible safety problems with US-licensed vaccines. VAERS reports can be submitted by anyone with concerns for vaccine adverse reactions, including patients, caregivers, and health care professionals at vaers.hhs.gov/reportevent.html. Additional information regarding VICP can be obtained at www.hrsa.gov/vaccine-compensation/index.html.

Military-Specific Issues

The military values readiness, which includes ensuring that active-duty members remain up-to-date on life-saving vaccinations. Immunization is of critical importance to mobility and success of the overall mission. Mobility processing lines where immunizations can be provided to multiple active-duty members can be a successful strategy for mass immunizations. Although the quick administration of immunizations maintains readiness and provides a medically necessary service, it also may increase the chances of incorrect vaccine placement in the deltoid, causing long-term shoulder immobility that may impact a service member’s retainability. The benefits of mobility processing lines can continue to outweigh the risks of immunization administration by ensuring proper staff training, seating both the administrator and recipient of vaccination, and selecting a proper needle length and site of administration specific to each recipient.

Conclusion

Correct administration of vaccines is of utmost importance in preventing SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder dysfunctions. Proper staff training and refresher training can help prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries. Additionally, clinicians should be aware of this potential complication and maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with postvaccination shoulder complaints.

Localized reactions and transient pain at the site of vaccine administration are frequent and well-described occurrences that are typically short-lived and mild in nature. The most common findings at the injection site are soreness, erythema, and edema.1 Although less common, generalized shoulder dysfunction after vaccine administration also has been reported. Bodor and colleagues described a peri-articular inflammatory response that led to shoulder pain and weakness.2 A single case report by Kuether and colleagues described atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after H1N1 vaccine administration in the deltoid.3 In 2010, shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) was described by Atanasoff and colleagues as the rapid onset of shoulder pain and dysfunction persisting as a complication of deltoid muscle vaccination in a case series of 13 patients.4 In our report, we present a case of an active-duty male eventually diagnosed with SIRVA after influenza vaccination and discuss factors that may prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty male presented to the Allergy clinic for evaluation of persistent left shoulder pain and decreased range of motion (ROM) following influenza vaccination 4 months prior. He reported a history of chronic low back and right shoulder pain. Although the patient had a traumatic injury to his right shoulder, which was corrected with surgery, he had no surgeries on the left shoulder. He reported no prior pain or known trauma to his left shoulder. He had no personal or family history of atopy or vaccine reactions.

The patient weighed 91 kg and received an intramuscular (IM) quadrivalent influenza vaccine with a 25-gauge, 1-inch needle during a mass influenza immunization. He recalled that the site of vaccination was slightly more than 3 cm below the top of the shoulder in a region correlating to the left deltoid. The vaccine was administered while he was standing with his arm extended, adducted, and internally rotated. The patient experienced intense pain immediately after the vaccination and noted decreased ROM. Initially, he dismissed the pain and decreased ROM as routine but sought medical attention when there was no improvement after 3 weeks.

Six weeks after the onset of symptoms, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed tendinopathy of the left distal subscapularis, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and teres minor tendon. These findings were suggestive of a small partial thickness tear of the supraspinatus (Figure 1), possible calcific tendinopathy of the distal teres minor (Figure 2), and underlying humeral head edema (Figure 3). The patient was evaluated by Orthopedics and experienced no relief from ibuprofen, celecoxib, and a steroid/lidocaine intra-articular injection. Laboratory studies included an unremarkable complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. He was diagnosed with SIRVA and continued in physical therapy with incomplete resolution of symptoms 6 months postvaccination.

Discussion

According to a 2018 report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, local reactions following immunizations are seen in up to 80% of administered vaccine doses.1 While most of these reactions are mild, transient, cutaneous reactions, rarely these also may persist and impact quality of life significantly. SIRVA is one such process that can lead to persistent musculoskeletal dysfunction. SIRVA presents as shoulder pain and limited ROM that occurs after the administration of an injectable vaccine. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine determined that evidence supported a causal relationship between vaccine administration and deltoid bursitis.5

In 2017, SIRVA was included in the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), a federal program that can provide compensation to individuals injured by certain vaccines.6 A diagnosis of SIRVA can be considered in patients who experience pain within 48 hours of vaccination, have no prior history of pain or dysfunction of the affected shoulder prior to vaccine administration, and have symptoms limited to the shoulder in which the vaccine was administered where no other abnormality is present to explain these symptoms (eg, brachial neuritis, other neuropathy). Currently, patients with back pain or musculoskeletal complaints that do not include the shoulder following deltoid vaccination do not meet the reporting criteria for SIRVA in the VICP.6

The exact prevalence or incidence of SIRVA is unknown. In a 2017 systematic review of the literature and the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System database, Martín Arias and colleagues found 45 cases of new onset, unilateral shoulder dysfunction without associated neuropathy or autoimmune conditions following vaccine administration. They noted a female to male predominance (71.1% vs 28.9%) with a mean age of 53.6 years (range 22-89 y). Most of the cases occurred following influenza vaccine (62%); pneumococcal vaccine was the next most common (13%).7 Shoulder injury also has been reported after tetanus-diphtheria toxoids, human papilloma virus, and hepatitis A virus vaccines.4,7 The review noted that all patients had onset of pain within the first week following vaccination with the majority (81%) having pain in the first 24 hours. Two cases found in the Spanish database had pain onset 2 months postvaccination.7 Atanasoff and colleagues found that 93% of patients had pain onset within 24 hours of vaccination with 54% reporting immediate pain.4

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) tracks reports of shoulder dysfunction following certain vaccinations, but the system is unable to establish causality. According to VAERS reporting, between 2010 and 2016, there were 1006 possible reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV) compared with an estimated 130 million doses of IIV given each influenza season in the US.8

Bodor and Montalvo postulated that vaccine antigen was being over penetrated into the synovial space of the shoulder, as the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa is located a mere 0.8 to 1.6 cm below the skin surface in patients with healthy body mass index.2 Atanasoff and colleagues expounded that antibodies from previous vaccination or natural infection may then form antigen-antibody complexes, creating prolonged local immune and inflammatory responses leading to bursitis or tendonitis.4 Martín Arias and colleagues hypothesized that improper injection technique, including wrong insertion angle, incorrect needle type/size, and failure to account for the patient’s physical characteristics were the most likely causes of SIRVA.7

Proper vaccine administration ensures that vaccinations are delivered in a safe and efficacious manner. Safe vaccination practices include the use of trained personnel who receive comprehensive, competency-based training regarding vaccine administration.1 Aspiration prior to an injection is a practice that has not been evaluated fully. Given that the 2 routinely recommended locations for IM vaccines (deltoid muscle in adults or vastus lateralis muscle in infants) lack large blood vessels, the practice of aspiration prior to an IM vaccine is not currently deemed necessary.1 Additional safe vaccine practices include the selection of appropriate needle length for muscle penetration and that anatomic landmarks determine the location of vaccination.1 Despite this, in a survey of 100 medical professionals, half could not name any structure at risk from improper deltoid vaccination technique.9

Cook and colleagues used anthropomorphic data to evaluate the potential for injury to the subdeltoid/subacromial bursa and/or the axillary nerve.10 Based on these data, they recommended safe IM vaccine administration can be assured by using the midpoint of the deltoid muscle located midway between the acromion and deltoid tuberosity with the arm abducted to 60°.10,11 In 46% of SIRVA cases described by Atanasoff and colleagues, patients reported that the vaccine was administered “too high.”4 The study also recommended that the clinician and the patient be in the seated position to ensure proper needle angle and location of administration.4 For most adults, a 1-inch needle is appropriate for vaccine administration in the deltoid; however, in females weighing < 70 kg and males < 75 kg, a 5/8-inch needle is recommended to avoid injury.7

Our 91-kg patient was appropriately administered his vaccine with a 1-inch needle. As he experienced immediate pain, it is unlikely that his symptoms were due to an immune-mediated process, as this would not be expected to occur immediately. Improper location of vaccine administration is a proposed mechanism of injury for our patient, though this cannot be confirmed by history alone. His prior history of traumatic injury to the opposite shoulder could represent a confounding factor as no prior imaging was available for the vaccine-affected shoulder. A preexisting shoulder abnormality or injury cannot be completely excluded, and it is possible that an underlying prior shoulder injury was aggravated postvaccination.

Evaluation and Treatment

There is no standardized approach for the evaluation of SIRVA to date. Awareness of SIRVA and a high index of suspicion are necessary to evaluate patients with shoulder concerns postvaccination. Laboratory evaluation should be considered to evaluate for other potential diagnoses (eg, infection, rheumatologic concerns). Routine X-rays are not helpful in cases of SIRVA. Ultrasound may be considered as it can show bursa abnormalities consistent with bursitis.2 MRI of the affected shoulder may provide improved diagnostic capability if SIRVA is suspected. MRI findings vary but include intraosseous edema, bursitis, tendonitis, and rotator cuff tears.4,12 Complete rotator cuff tears were found in 15% of cases reviewed by Atanasoff and colleagues.4 While there is no recommended timing for MRI, 63% of MRIs were performed within 3 months of symptom onset.4 As SIRVA is not a neurologic injury, nerve conduction, electromyographic studies, and neurologic evaluation or testing are expected to be normal.

Treatment of SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder injuries typically have involved pain management (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents), intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy, though some patients never experience complete resolution of symptoms.2,4,7 Both patients with vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction described by Bodor and colleagues improved after intra-articular triamcinolone injections, with up to 3 injections before complete resolution of pain in one patient.2 Orthopedics evaluation may need to be considered for persistent symptoms. According to Atanasoff and colleagues, most patients were symptomatic for at least 6 months, and complete recovery was seen in less than one-third of patients.4 Although the development of SIRVA is not a contraindication to future doses of the presumed causative vaccine, subsequent vaccination should include careful consideration of other administration sites if possible (eg, vastus lateralis may be used for IM injections in adults) (Figure 4).

Reporting

A diagnosis or concern for SIRVA also should be reported to the VAERS, the national database established in order to detect possible safety problems with US-licensed vaccines. VAERS reports can be submitted by anyone with concerns for vaccine adverse reactions, including patients, caregivers, and health care professionals at vaers.hhs.gov/reportevent.html. Additional information regarding VICP can be obtained at www.hrsa.gov/vaccine-compensation/index.html.

Military-Specific Issues

The military values readiness, which includes ensuring that active-duty members remain up-to-date on life-saving vaccinations. Immunization is of critical importance to mobility and success of the overall mission. Mobility processing lines where immunizations can be provided to multiple active-duty members can be a successful strategy for mass immunizations. Although the quick administration of immunizations maintains readiness and provides a medically necessary service, it also may increase the chances of incorrect vaccine placement in the deltoid, causing long-term shoulder immobility that may impact a service member’s retainability. The benefits of mobility processing lines can continue to outweigh the risks of immunization administration by ensuring proper staff training, seating both the administrator and recipient of vaccination, and selecting a proper needle length and site of administration specific to each recipient.

Conclusion

Correct administration of vaccines is of utmost importance in preventing SIRVA and other vaccine-related shoulder dysfunctions. Proper staff training and refresher training can help prevent vaccine-related shoulder injuries. Additionally, clinicians should be aware of this potential complication and maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with postvaccination shoulder complaints.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-admin.html. Published 2015. Accessed June 3, 2019.

2. Bodor M, Montalvo E. Vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction. Vaccine. 2007;25(4):585-587.

3. Kuether G, Dietrich B, Smith T, Peter C, Gruessner S. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after influenza A-(H1N1) v-2009 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29(40):6830-6833.

4. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, Johann-Liang R. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28(51):8049-8052.

5. Institute of Medicine. Adverse effects of vaccines: evidence and causality. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2011/Adverse-Effects-of-Vaccines-Evidence-and-Causality/Vaccine-report-brief-FINAL.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed June 3, 2019.

6. Health Resources and Services Administration, Health and Human Services Administration. National vaccine injury compensation program: revisions to the vaccine injury table. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/19/2017-00701/national-vaccine-injury-compensation-program-revisions-to-the-vaccine-injury-table. Published January 19, 2017. Accessed June 3, 2019.

7. Martín Arias LH, Sanz Fadrique R, Sáinz Gil M, Salgueiro-Vazquez ME. Risk of bursitis and other injuries and dysfunctions of the shoulder following vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):4870-4876.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2010-2016. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/57624. Published January 4, 2018. Accessed June 3, 2019.

9. McGarvey MA, Hooper AC. The deltoid intramuscular injection site in the adult. Current practice among general practitioners and practice nurses. Ir Med J. 2005;98(4):105-107.

10. Cook IF. An evidence based protocol for the prevention of upper arm injury related to vaccine administration (UAIRVA). Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(8):845-848.

11. Cook IF. Best vaccination practice and medically attended injection site events following deltoid intramuscular injection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(5):1184-1191.

12. Okur G, Chaney KA, Lomasney LM. Magnetic resonance imaging of abnormal shoulder pain following influenza vaccination. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(9):1325-1331.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-admin.html. Published 2015. Accessed June 3, 2019.

2. Bodor M, Montalvo E. Vaccination-related shoulder dysfunction. Vaccine. 2007;25(4):585-587.

3. Kuether G, Dietrich B, Smith T, Peter C, Gruessner S. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head after influenza A-(H1N1) v-2009 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29(40):6830-6833.

4. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, Johann-Liang R. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28(51):8049-8052.

5. Institute of Medicine. Adverse effects of vaccines: evidence and causality. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2011/Adverse-Effects-of-Vaccines-Evidence-and-Causality/Vaccine-report-brief-FINAL.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed June 3, 2019.

6. Health Resources and Services Administration, Health and Human Services Administration. National vaccine injury compensation program: revisions to the vaccine injury table. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/19/2017-00701/national-vaccine-injury-compensation-program-revisions-to-the-vaccine-injury-table. Published January 19, 2017. Accessed June 3, 2019.

7. Martín Arias LH, Sanz Fadrique R, Sáinz Gil M, Salgueiro-Vazquez ME. Risk of bursitis and other injuries and dysfunctions of the shoulder following vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):4870-4876.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reports of shoulder dysfunction following inactivated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2010-2016. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/57624. Published January 4, 2018. Accessed June 3, 2019.

9. McGarvey MA, Hooper AC. The deltoid intramuscular injection site in the adult. Current practice among general practitioners and practice nurses. Ir Med J. 2005;98(4):105-107.

10. Cook IF. An evidence based protocol for the prevention of upper arm injury related to vaccine administration (UAIRVA). Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(8):845-848.

11. Cook IF. Best vaccination practice and medically attended injection site events following deltoid intramuscular injection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(5):1184-1191.

12. Okur G, Chaney KA, Lomasney LM. Magnetic resonance imaging of abnormal shoulder pain following influenza vaccination. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(9):1325-1331.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Patients With Low Back Pain

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

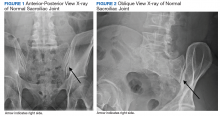

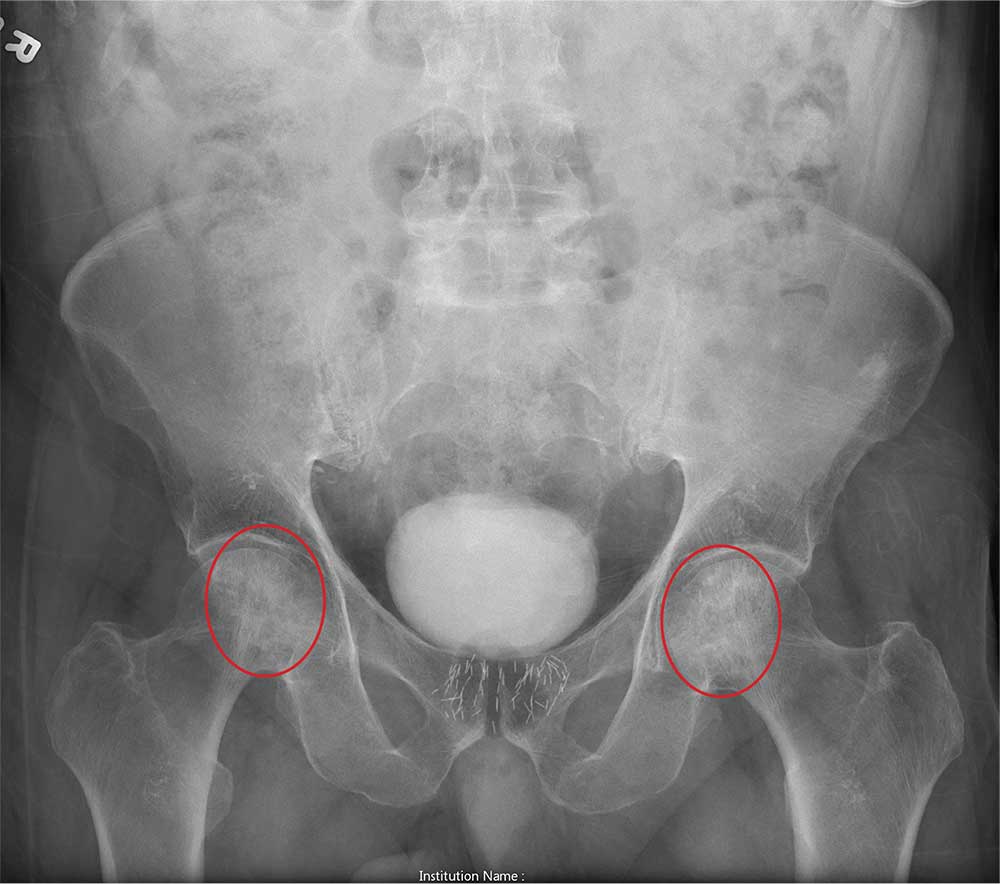

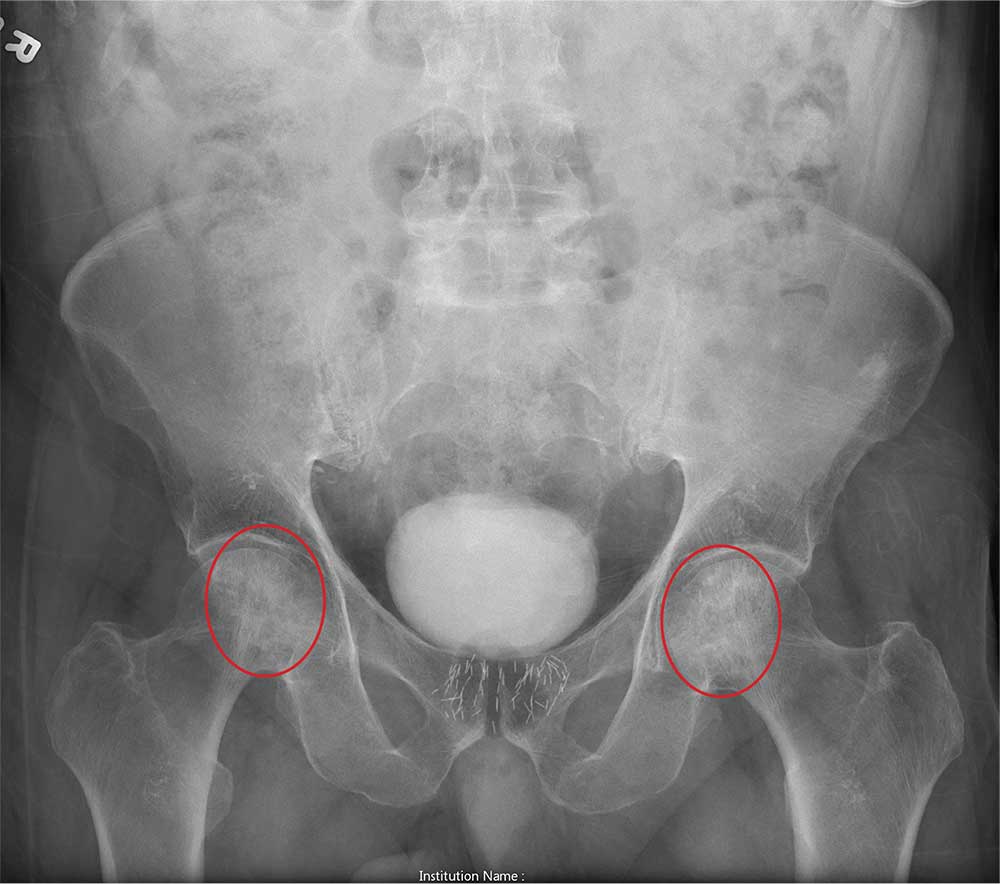

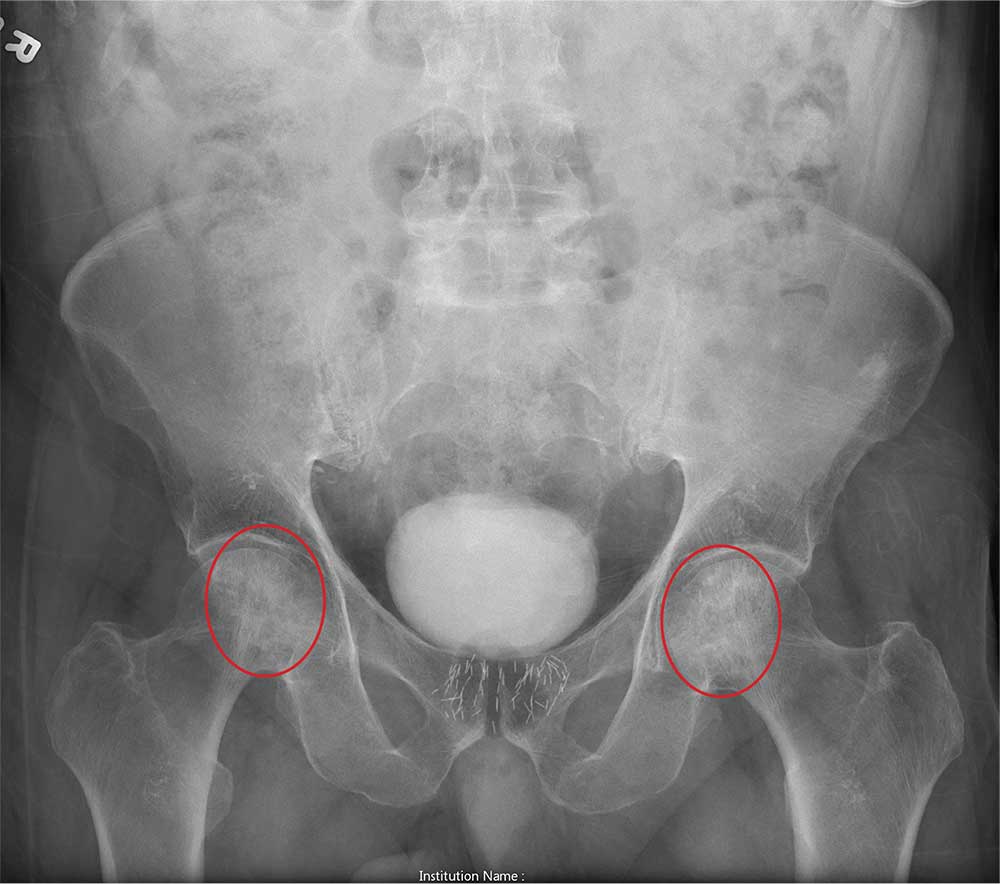

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

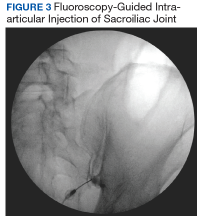

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment

Nonoperative management of SIJ dysfunction includes exercise programs, physical therapy, manual manipulation therapy, sacroiliac belts, and periodic articular injections. Efficacy of these methods is variable, and analgesics often do not significantly benefit this type of pain. Another nonoperative approach is radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the lumbar dorsal rami and lateral sacral branches, which can vary based on the number of rami treated as well as the technique used. About two-thirds of patients report pain relief after RFA.2 When successful, pain is relieved for 6 to 12 months, which is a temporary yet effective option for patients experiencing SIJ dysfunction.14,20

Fusion Surgery

Cadaver studies show that biomechanical stabilization of the SIJ leads to decreased range of motion in flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. This results in a decreased need for periarticular muscular and ligamentous support, therefore facilitating load transfer across the SIJ.21,22 Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery report better pain relief compared with those receiving open surgery at 12 months postoperatively.23 The 2 main SIJ fusion approaches used are the lateral transarticular and the dorsal approaches. In the dorsal approach, the SIJ is distracted and allograft dowels or titanium cages with graft are inserted into the joint space posteriorly through the back. When approaching laterally, hollow screw implants filled with graft or triangular titanium implants are placed across the joint, accessing the SIJ through the iliac bones using imaging guidance. This lateral transiliac approach using porous titanium triangular rods currently is the most studied technique.24

A recent prospective, multicenter trial included 423 patients with SIJ dysfunction who were randomized to receive SIJ fusion with triangular titanium implants vs a control group who received nonoperative management. Patients in the SIJ fusion group showed substantially greater improvement in pain (81.4%) compared with that of the nonoperative group (26.1%) 6 months after surgery. Pain relief in the SIJ fusion group was maintained at > 80% at 1 and 2 year follow-up, while the nonoperative group’s pain relief decreased to < 10% at the follow-ups. Measures of quality of life and disability also improved for the SIJ fusion group compared with that of the nonoperative group. Patients who were crossed over from conservative management to SIJ fusion after 6 months demonstrated improvements that were similar to those in the SIJ fusion group by the end of the study. Only 3% of patients required surgical revision. The strongest predictor of pain relief after surgery was a diagnostic SIJ anesthetic block of 30 to 60 minutes, which resulted in > 75% pain reduction.21,25 Additional predictors of successful SIJ fusion include nonsmokers, nonopioid users, and older patients who have a longer time course of SIJ pain.26

Another study investigating the outcomes of SIJ fusion, RFA, and conservative management with a 6-year follow-up demonstrated similar results.27 This further confirms the durability of the surgical group’s outcome, which sustained significant improvement compared with RFA and conservative management group in pain relief, daily function, and opioid use.

HCPs should consider SIJ fusion for patients who have at least 6 months of unsuccessful nonoperative management, significant SIJ pain (> 5 in a 10-point scale), ≥ 3 positive provocation tests, and at least 50% pain relief (> 75% preferred) with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injection.14 It is reasonable for primary care providers to refer these patients to a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon for possible fusion. Patients with earlier lumbar/lumbosacral spinal fusions and persistent LBP should be evaluated for potential SIJ dysfunction. SIJ dysfunction after lumbosacral fusion could be considered a form of distal pseudarthrosis resulting from increased motion at the joint. One study found its incidence correlated with the number of segments fused in the lumbar spine.28 Another study found that about one-third of patients with persistent LBP after lumbosacral fusion could be attributed to SIJ dysfunction.29

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female army veteran presented with bilateral buttock pain, which she described as a dull, aching pain across her sacral region, 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain was in a L5-S1 pattern. The pain was bilateral, with the right side worse than the left, and worsened with lateral bending and load transferring. She reported no numbness, tingling, or weakness.

On physical examination, she had full strength in her lower extremities and intact sensation. She reported tenderness to palpation of the sacrum and SIJ. Her gait was normal. The patient had positive thigh thrust and distraction tests. Lumbar spine X-ray, CT, MRI, and electromyographic studies did not show any pathology. She described little or no relief with analgesics or physical therapy. Previous L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet anesthetic injections and transforaminal epidural steroid injections provided minimal pain relief immediately after the procedures. Bilateral SIJ anesthetic injections under fluoroscopic guidance decreased her pain severity from a 7 to 3 out of 10 for 2 to 3 months before returning to her baseline. Radiofrequency ablation of the right SIJ under fluoroscopy provided moderate relief for about 4 months.

After exhausting nonoperative management for SIJ dysfunction without adequate pain control, the patient was referred to neurosurgery for surgical fusion. The patient was deemed an appropriate surgical candidate and underwent a right-sided SIJ fusion (Figures 4 and 5). At her 6-month and 1-year follow-up appointments, she had lasting pain relief, 2 out of 10.

Conclusion

SIJ dysfunction is widely overlooked because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other similarly presenting syndromes. However, with a detailed history, appropriate physical maneuvers, imaging, and adequate response to intra-articular anesthetic, providers can reach an accurate diagnosis that will inform subsequent treatments. After failure of nonsurgical methods, patients with SIJ dysfunction should be considered for minimally invasive fusion techniques, which have proven to be a safe, effective, and viable treatment option.

1. Zaidi HA, Montoure AJ, Dickman CA. Surgical and clinical efficacy of sacroiliac joint fusion: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(1):59-66.

2. Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5):1440-1453.

3. Chou LH, Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, et al. Inciting events initiating injection‐proven sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med. 2004;5(1):26-32.

4. Dreyfuss P, Dreyer SJ, Cole A, Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(4):255-265.

5. Buijs E, Visser L, Groen G. Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint: a forgotten concept. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(5):713-716.

6. Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: asymptomatic volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(13):1475-1482.

7. Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):31-37.

8. Fortin JD, Washington WJ, Falco FJ. Three pathways between the sacroiliac joint and neural structures. ANJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(8):1429-1434.

9. Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354-368.

10. Merskey H, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

11. Cusi MF. Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfunction. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(2):152-161.

12. Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207-218.

13. Laslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(3):142-152.

14. Polly DW Jr. The sacroiliac joint. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2017;28(3):301-312.

15. Cusi M, Van Der Wall H, Saunders J, Fogelman I. Metabolic disturbances identified by SPECT-CT in patients with a clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint incompetence. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(7):1674-1682.

16. Tofuku K, Koga H, Komiya S. The diagnostic value of single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography for severe sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(4):859-863.

17. Kennedy DJ, Engel A, Kreiner DS, Nampiaparampil D, Duszynski B, MacVicar J. Fluoroscopically guided diagnostic and therapeutic intra‐articular sacroiliac joint injections: a systematic review. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1500-1518.

18. Schneider BJ, Huynh L, Levin J, Rinkaekan P, Kordi R, Kennedy DJ. Does immediate pain relief after an injection into the sacroiliac joint with anesthetic and corticosteroid predict subsequent pain relief? Pain Med. 2018;19(2):244-251.

19. Murakami E, Tanaka Y, Aizawa T, Ishizuka M, Kokubun S. Effect of periarticular and intraarticular lidocaine injections for sacroiliac joint pain: prospective comparative study. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12(3):274-280.

20. Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Kurihara C, Morlando B, Dragovich A. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(2):279-288.

21. Polly DW, Cher DJ, Wine KD, et al; INSITE Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants vs nonsurgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: 12-month outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(5):674-690.

22. Soriano-Baron H, Lindsey DP, Rodriguez-Martinez N, et al. The effect of implant placement on sacroiliac joint range of motion: posterior versus transarticular. Spine. 2015;40(9):E525-E530.

23. Smith AG, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. Open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a multi-center comparison of perioperative measures and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):14.

24. Rashbaum RF, Ohnmeiss DD, Lindley EM, Kitchel SH, Patel VV. Sacroiliac joint pain and its treatment. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(2):42-48.

25. Polly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, et al. Two-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion vs. non-surgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:28.

26. Dengler J, Duhon B, Whang P, et al. Predictors of outcome in conservative and minimally invasive surgical management of pain originating from the sacroiliac joint: a pooled analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(21):1664-1673.

27. Vanaclocha V, Herrera JM, Sáiz-Sapena N, Rivera-Paz M, Verdú-López F. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, radiofrequency denervation, and conservative management for sacroiliac joint pain: 6-year comparative case series. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(1):48-55.

28. Unoki E, Abe E, Murai H, Kobayashi T, Abe T. Fusion of multiple segments can increase the incidence of sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(12):999-1005.

29. Katz V, Schofferman J, Reynolds J. The sacroiliac joint: a potential cause of pain after lumbar fusion to the sacrum. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):96-99.

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment