User login

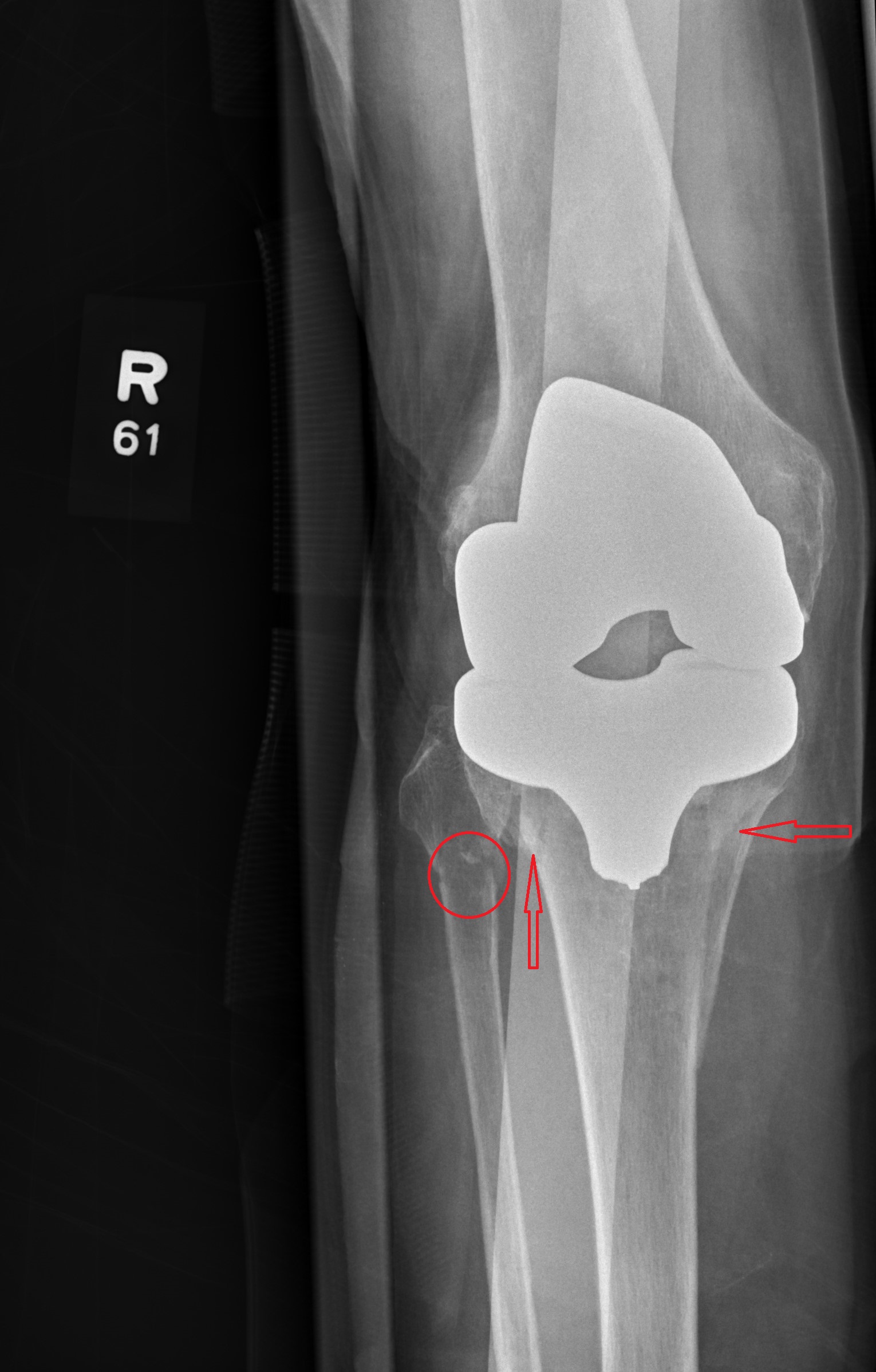

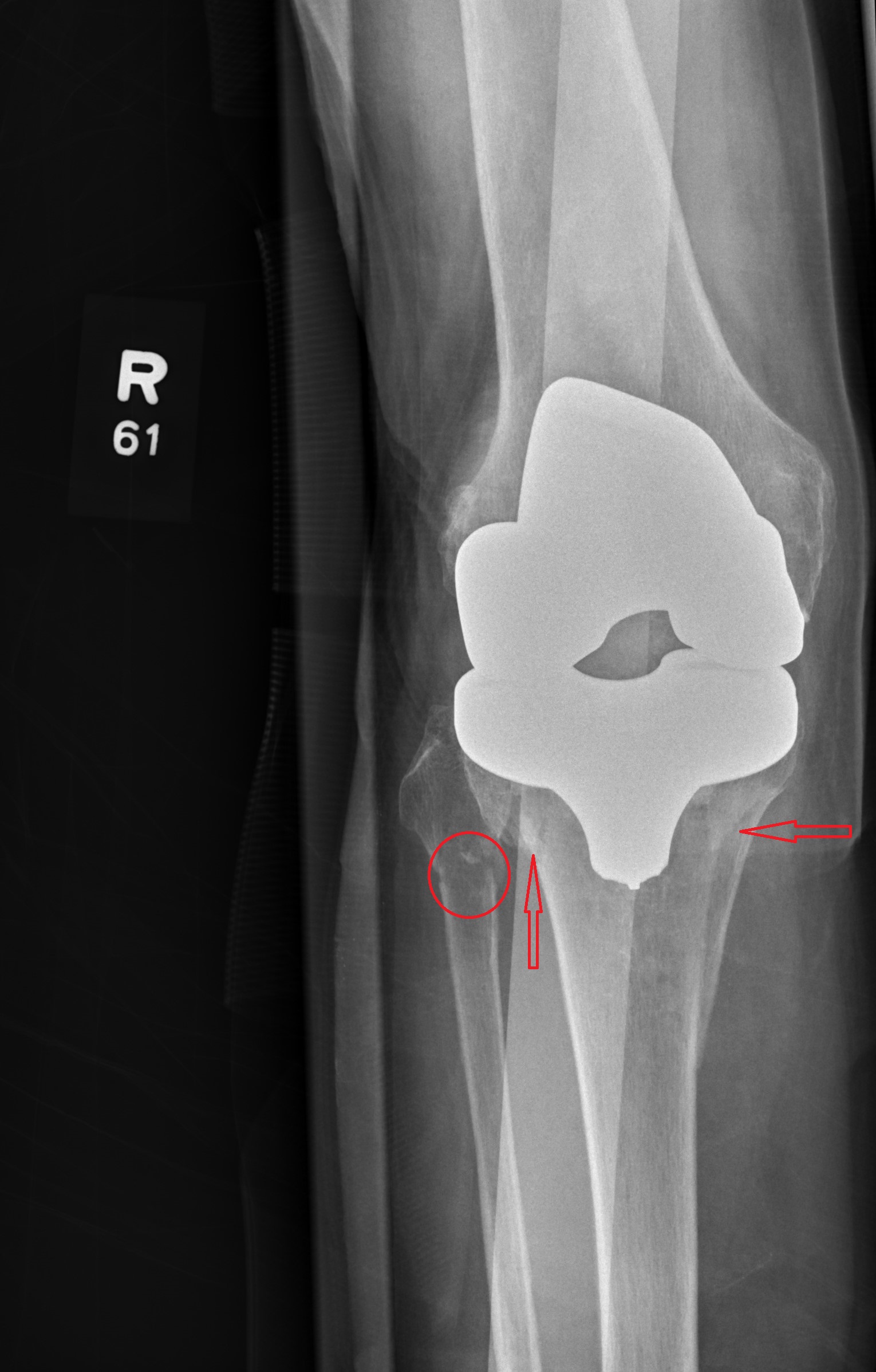

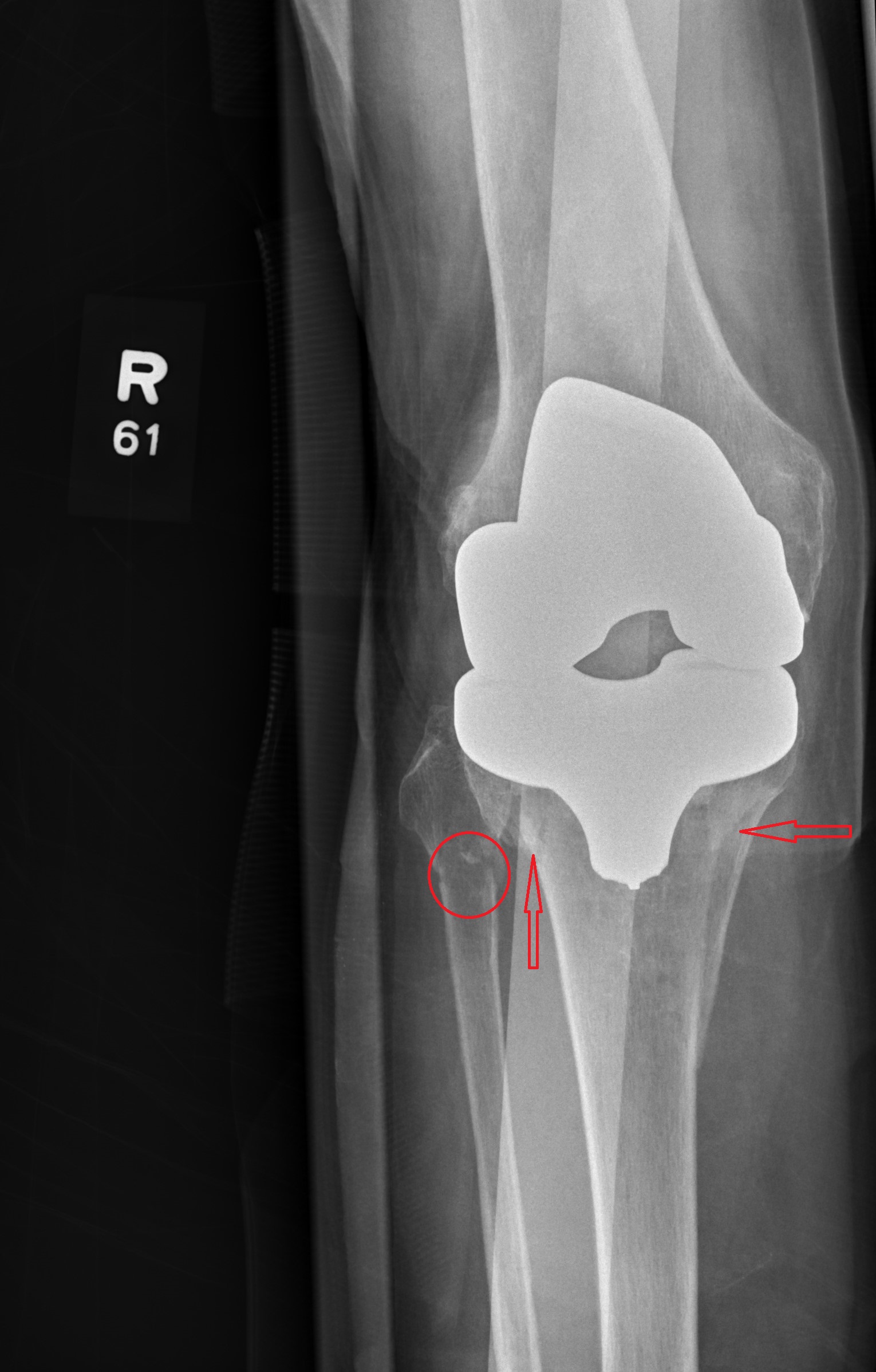

Fewer complications, better outcomes with outpatient UKA

according to a review from the University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic, Memphis.

“In carefully selected patients, the ASC [ambulatory surgery center] seems to be a safe alternative to the inpatient hospital setting,” concluded investigators led by led by Marcus Ford, MD, a Campbell Clinic orthopedic surgeon.

He and his colleagues have been doing outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) since 2009, and “based on the subjective success,” recently increased the number of total knee, hip, and shoulder arthroplasties performed in their ASC.

They wanted to make sure, however, that their impression of good outpatient UKA results was supported by the data, so they compared outcomes in 48 UKA patients treated at their ASC with 48 treated in the hospital. The operations were done by two surgeons using the same technique and same medial UKA implant.

“Naturally, surgeons select those patients who are deemed physically and mentally capable of succeeding with an accelerated discharge plan” for outpatient service, the investigators wrote. To address that potential selection bias, the team matched their subjects by age and comorbidities.

There was only one minor complication in the outpatient group, a superficial stitch abscess. No patient needed a second operation, and all went home the same day.

It was different on the inpatient side. The average length of stay was 2.9 days, and there were four major complications: a deep venous thrombosis, a pulmonary embolus, an acute postoperative infection, and a periprosthetic fracture. All four required hospital readmission, and two patients needed a second operation.

The report didn’t directly address the reasons for the differences, but Dr. Ford and colleagues did note that they “believe that the ASC allows the surgeon greater direct control of perioperative variables that can impact patient outcome.”

Patients were in their late 50s, on average, and there were more women than men in both groups. The mean American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification score was 1.94 and mean body mass index was 34.3 kg/m2 in the outpatient group, compared with a mean physical status classification score of 2.08 and mean body mass index of 32.9 kg/m2 in the inpatient group. The differences were not statistically significant.

No funding source was reported. The investigators did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Ford M et al. Orthop Clin North Am. 2020 Jan;51[1]:1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.08.001

according to a review from the University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic, Memphis.

“In carefully selected patients, the ASC [ambulatory surgery center] seems to be a safe alternative to the inpatient hospital setting,” concluded investigators led by led by Marcus Ford, MD, a Campbell Clinic orthopedic surgeon.

He and his colleagues have been doing outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) since 2009, and “based on the subjective success,” recently increased the number of total knee, hip, and shoulder arthroplasties performed in their ASC.

They wanted to make sure, however, that their impression of good outpatient UKA results was supported by the data, so they compared outcomes in 48 UKA patients treated at their ASC with 48 treated in the hospital. The operations were done by two surgeons using the same technique and same medial UKA implant.

“Naturally, surgeons select those patients who are deemed physically and mentally capable of succeeding with an accelerated discharge plan” for outpatient service, the investigators wrote. To address that potential selection bias, the team matched their subjects by age and comorbidities.

There was only one minor complication in the outpatient group, a superficial stitch abscess. No patient needed a second operation, and all went home the same day.

It was different on the inpatient side. The average length of stay was 2.9 days, and there were four major complications: a deep venous thrombosis, a pulmonary embolus, an acute postoperative infection, and a periprosthetic fracture. All four required hospital readmission, and two patients needed a second operation.

The report didn’t directly address the reasons for the differences, but Dr. Ford and colleagues did note that they “believe that the ASC allows the surgeon greater direct control of perioperative variables that can impact patient outcome.”

Patients were in their late 50s, on average, and there were more women than men in both groups. The mean American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification score was 1.94 and mean body mass index was 34.3 kg/m2 in the outpatient group, compared with a mean physical status classification score of 2.08 and mean body mass index of 32.9 kg/m2 in the inpatient group. The differences were not statistically significant.

No funding source was reported. The investigators did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Ford M et al. Orthop Clin North Am. 2020 Jan;51[1]:1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.08.001

according to a review from the University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic, Memphis.

“In carefully selected patients, the ASC [ambulatory surgery center] seems to be a safe alternative to the inpatient hospital setting,” concluded investigators led by led by Marcus Ford, MD, a Campbell Clinic orthopedic surgeon.

He and his colleagues have been doing outpatient unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) since 2009, and “based on the subjective success,” recently increased the number of total knee, hip, and shoulder arthroplasties performed in their ASC.

They wanted to make sure, however, that their impression of good outpatient UKA results was supported by the data, so they compared outcomes in 48 UKA patients treated at their ASC with 48 treated in the hospital. The operations were done by two surgeons using the same technique and same medial UKA implant.

“Naturally, surgeons select those patients who are deemed physically and mentally capable of succeeding with an accelerated discharge plan” for outpatient service, the investigators wrote. To address that potential selection bias, the team matched their subjects by age and comorbidities.

There was only one minor complication in the outpatient group, a superficial stitch abscess. No patient needed a second operation, and all went home the same day.

It was different on the inpatient side. The average length of stay was 2.9 days, and there were four major complications: a deep venous thrombosis, a pulmonary embolus, an acute postoperative infection, and a periprosthetic fracture. All four required hospital readmission, and two patients needed a second operation.

The report didn’t directly address the reasons for the differences, but Dr. Ford and colleagues did note that they “believe that the ASC allows the surgeon greater direct control of perioperative variables that can impact patient outcome.”

Patients were in their late 50s, on average, and there were more women than men in both groups. The mean American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification score was 1.94 and mean body mass index was 34.3 kg/m2 in the outpatient group, compared with a mean physical status classification score of 2.08 and mean body mass index of 32.9 kg/m2 in the inpatient group. The differences were not statistically significant.

No funding source was reported. The investigators did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Ford M et al. Orthop Clin North Am. 2020 Jan;51[1]:1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.08.001

FROM ORTHOPEDIC CLINICS OF NORTH AMERICA

Hip fracture patients with dementia benefit from increased rehab intensity

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

according to a recent Japanese study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Looking at 43,506 patients cared for at 1,053 hospitals, Kazuaki Uda, MPH, and colleagues of the University of Tokyo found that scores on the Barthel Index, a measure of functional status, climbed significantly as the frequency and duration of postoperative rehabilitation increased. There was also a statistically significant, but small, association with improved functional status and early initiation of rehabilitation.

“Our results suggest that additional days of rehabilitation or an additional 20 minutes for each daily rehabilitation session in acute-care hospitals may provide better functional outcomes for patients with dementia,” concluded Mr. Uda and coinvestigators.

The Barthel Index (BI) measures independence in performing 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, bathing, grooming, and dressing; bowel, bladder, and toileting; and transfers, mobility, and stair use. Each ADL is rate 0, 5, 10, or, for some, 15 points, and higher scores indicate more independence.

Compared with patients who received 3 days or fewer of rehabilitation weekly, patients receiving 3-4 days of rehabilitation saw an improvement of 2.62 on the BI. For those receiving 4-5 days, 5-6 days, and 6 or more days of rehabilitation, BI scores were higher by 5.83, 7.56, and 9.16, respectively. The results were statistically significant for all but the 3-4 day rehabilitation group.

Similarly, patients who received longer periods of rehabilitation saw more improvement in functional status. Compared with those who received 20-39 minutes per day of rehabilitation, those who received 40-59 minutes of therapy saw an increase of 4.37 on the BI, and those receiving an hour or more of therapy saw BI scores rise by 6.60 – both significant increases.

These results included a multivariable analysis that accounted for a number of patient characteristics such as comorbidities and body mass index, as well as fracture, fixation, and anesthesia type, and the interval from injury to surgery.

Representing the data in another way, the investigators found that “each increase in the average units of rehabilitation (units per day) was associated with a 5.46 increase in the BI.”

This retrospective cohort study, when placed in the context of previous work, suggests that “patients with cognitive impairment may benefit from rehabilitation for functional gains after hip fracture surgery in both acute and postacute settings,” the investigators wrote. They noted, however, that patients with dementia have often been excluded from larger outcome studies of hip fracture rehabilitation.

Patients in this study had a median 21-day inpatient stay after admission for their hip fracture, so much of the rehabilitation included as inpatient care in the Japanese schema would be delivered in the outpatient setting in the United States, where the mean inpatient length of stay after hip fracture is about 5 days.

Patients aged 65 years and older were included in the study if they had a prefracture diagnosis of dementia and sustained a hip fracture that was surgically repaired. Patients with multiple fracture sites, those with incomplete data, and those who didn’t undergo surgery or died in the hospital were excluded from the study. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.7%) were aged 85 years or older, and about a third (36.6%) were living in nursing facilities at the time of fracture. About 60% of patients were assessed as having mild dementia – a classification requiring little assistance with ADLs – before admission.

The authors noted that their study broke out timing, duration, and frequency of rehabilitation separately, unlike some previous work. They posited that longer or more frequent rounds of rehabilitation may be particularly effective in patients with dementia, who may face some communication barriers and require reteaching.

The study was unrandomized by design, and unmeasured confounders may have affected the results, they noted. Also, the study wasn’t designed to detect whether patient factors such as premorbid functional status, level of dementia, or living situation affected the timing, duration, and intensity of rehabilitation they were provided. The investigators recommended randomized studies to validate the effect of early, intensive rehabilitation for hip fracture surgery in patients with dementia.

The study was funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The authors reported that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Uda K et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:2301-7.

REPORTING FROM THE ARCHIVES OF PHYSICAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION

Delayed hospital admission after hip fracture raises mortality risk

a retrospective, observational study suggests.

Among 867 elderly patients who underwent hip fracture surgery at a university hospital in China and who were available for follow-up, the proportion hospitalized on the day of injury was 25.4%, and the proportion hospitalized on days 1, 2, and 7 after injury were 54.7%, 66.3%, and 12.6%, respectively, reported Wei He, MD, of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and colleagues in the World Journal of Emergency Medicine.

The mean time from admission to surgery was 5.2 days. Mortality rates at 1 year, 3 months, and 1 month after surgery were 10.5%, 5.4%, and 3.3%, respectively. Hospitalization at 7 or more days after injury was an independent risk factor for 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 1.76), the authors found.

Although the influence of surgical delay on mortality and morbidity among hip fracture patients has been widely studied, most data focus on surgery timing among hospitalized patients and fail to consider preadmission waiting time, they noted.

The current study aimed to assess outcomes based on “actual preadmission waiting time” through an analysis of data and surgical outcomes from a hospital electronic medical record system and from postoperative telephone interviews. Study subjects were patients aged over 65 years who underwent hip fracture surgery between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2017. The mean age was 81.4 years, 74.7% of the patients were women, 67.1% had femoral neck fracture, and 56.1% had hip replacement surgery.

The findings, though limited by the retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design, suggest that, under the current conditions in China, admission delay may increase 1-year mortality, they wrote, concluding that “[i]n addition to early surgery highlighted in the guidelines, we also advocate early admission.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: He W et al. World J Emerg Med. 2020;11(1):27-32.

a retrospective, observational study suggests.

Among 867 elderly patients who underwent hip fracture surgery at a university hospital in China and who were available for follow-up, the proportion hospitalized on the day of injury was 25.4%, and the proportion hospitalized on days 1, 2, and 7 after injury were 54.7%, 66.3%, and 12.6%, respectively, reported Wei He, MD, of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and colleagues in the World Journal of Emergency Medicine.

The mean time from admission to surgery was 5.2 days. Mortality rates at 1 year, 3 months, and 1 month after surgery were 10.5%, 5.4%, and 3.3%, respectively. Hospitalization at 7 or more days after injury was an independent risk factor for 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 1.76), the authors found.

Although the influence of surgical delay on mortality and morbidity among hip fracture patients has been widely studied, most data focus on surgery timing among hospitalized patients and fail to consider preadmission waiting time, they noted.

The current study aimed to assess outcomes based on “actual preadmission waiting time” through an analysis of data and surgical outcomes from a hospital electronic medical record system and from postoperative telephone interviews. Study subjects were patients aged over 65 years who underwent hip fracture surgery between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2017. The mean age was 81.4 years, 74.7% of the patients were women, 67.1% had femoral neck fracture, and 56.1% had hip replacement surgery.

The findings, though limited by the retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design, suggest that, under the current conditions in China, admission delay may increase 1-year mortality, they wrote, concluding that “[i]n addition to early surgery highlighted in the guidelines, we also advocate early admission.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: He W et al. World J Emerg Med. 2020;11(1):27-32.

a retrospective, observational study suggests.

Among 867 elderly patients who underwent hip fracture surgery at a university hospital in China and who were available for follow-up, the proportion hospitalized on the day of injury was 25.4%, and the proportion hospitalized on days 1, 2, and 7 after injury were 54.7%, 66.3%, and 12.6%, respectively, reported Wei He, MD, of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and colleagues in the World Journal of Emergency Medicine.

The mean time from admission to surgery was 5.2 days. Mortality rates at 1 year, 3 months, and 1 month after surgery were 10.5%, 5.4%, and 3.3%, respectively. Hospitalization at 7 or more days after injury was an independent risk factor for 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 1.76), the authors found.

Although the influence of surgical delay on mortality and morbidity among hip fracture patients has been widely studied, most data focus on surgery timing among hospitalized patients and fail to consider preadmission waiting time, they noted.

The current study aimed to assess outcomes based on “actual preadmission waiting time” through an analysis of data and surgical outcomes from a hospital electronic medical record system and from postoperative telephone interviews. Study subjects were patients aged over 65 years who underwent hip fracture surgery between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2017. The mean age was 81.4 years, 74.7% of the patients were women, 67.1% had femoral neck fracture, and 56.1% had hip replacement surgery.

The findings, though limited by the retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design, suggest that, under the current conditions in China, admission delay may increase 1-year mortality, they wrote, concluding that “[i]n addition to early surgery highlighted in the guidelines, we also advocate early admission.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: He W et al. World J Emerg Med. 2020;11(1):27-32.

FROM THE WORLD JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE

SimLEARN Musculoskeletal Training for VHA Primary Care Providers and Health Professions Educators

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

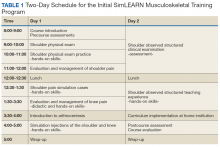

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

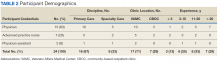

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

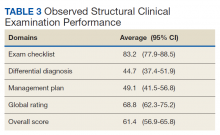

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.

This program has several significant strengths: First, this is the most recent step in the development of a portfolio of innovative MSK CPD programs that were envisioned through a systematic process involving projections of cost-effectiveness, local pilot testing, and national expansion.17,18,35 Second, the SimLEARN program uses assessment tools for which validity evidence has been published, made available for reflective critique by educational scholars.19,23 This supports a national consortium of MSK educators, advancing clinical teaching and educational scholarship, and creating opportunities for interprofessional collaboration in congruence with the vision expressed in the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions,” as well as the 2016 update of the BEME recommendations for faculty development.36,37

Our experience with the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrates need for 2 distinct courses: (1) the MSK Clinician—serving PCPs seeking to develop their skills in evaluating and managing patients with MSK problems; and (2), the MSK Master Educator—for those with preexisting content expertise who would value the introduction to a national curriculum and connections with other MSK master educators. Both of these are now offered regularly through SimLEARN for VHA and US Department of Defense employees. The MSK Clinician program establishes competence in systematically evaluating and managing shoulder and knee MSK problems in an educational setting and prepares participants for subsequent clinical experiences where they can perform related procedures if desired, under appropriate supervision. The Master Educator program introduces partici pants to the clinician curriculum and provides the opportunity to develop an individualized plan for implementation of an MSK educational program at their home institutions. Participants are selected through a competitive application process, and funding for travel to attend the Master Educator program is provided by SimLEARN for participants who are accepted. Additionally, the Master Educator program serves as a repository for potential future SimLEARN MSK Clinician course faculty.

Limitations

The small number of participants may limit the validity of our conclusions. Although we included an OSCE to measure competence in performing and interpreting the shoulder exam, the durability of these skills is not known. Periodic postcourse OSCEs could help determine this and refresh and preserve accuracy in the performance of specific maneuvers. Second, although this experience was rated highly by participants, we do not know the impact of the program on their daily work or career trajectory. Sustained follow-up of learners, perhaps developed on the model of the Long-Term Career Outcome Study, may increase the value of this experience for future participants.38 This program appealed to a diverse pool of learners, with a broad range of precourse expertise and varied expectations of how course experiences would impact their future work and career development. Some clinical educator attendees came from tertiary care facilities affiliated with academic medical centers, held specialist or subspecialist credentials, and had formal responsibilities as leaders in HPE. Other clinical practitioner participants were solitary PCPs, often in rural or home-based settings; although they may have been eager to apply new knowledge and skills in patient care, they neither anticipated nor desired any role as an educator.

Conclusion

The initial SimLEARN MSK Training Program provides PCPs and clinician educators with rich learning experiences, increasing confidence in addressing MSK problems and competence in performing and interpreting a systematic physical examination of the shoulder. The success of this program has created new opportunities for practitioners seeking to strengthen clinical skills and for leaders in health professions education looking to disseminate similar trainings and connect with a national group of educators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the faculty and staff at the Veterans Health Administration SimLEARN National Simulation Center, the faculty of the Salt Lake City Musculoskeletal Mini-Residency program, the supportive leadership of the George E. Wahlen Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the efforts of Danielle Blake for logistical support and data entry.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26-35.

3. Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001-2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(4):460-464.

4. Gupta S, Hawker GA, Laporte A, Croxford R, Coyte PC. The economic burden of disabling hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) from the perspective of individuals living with this condition. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(12):1531-1537.

5. Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct medical costs of patients with osteoarthritis in usual care: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):497-507.

6. Rabenda V, Manette C, Lemmens R, Mariani AM, Struvay N, Reginster JY. Direct and indirect costs attributable to osteoarthritis in active subjects. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1152-1158.

7. Day CS, Yeh AC. Evidence of educational inadequacies in region-specific musculoskeletal medicine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(10):2542-2547.

8. Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R. Determinants of physician confidence in the primary care management of musculoskeletal disorders. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(2):351-356.

9. Haywood BL, Porter SL, Grana WA. Assessment of musculoskeletal knowledge in primary care residents. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2006;35(6):273-275.

10. Monrad SU, Zeller JL, Craig CL, Diponio LA. Musculoskeletal education in US medical schools: lessons from the past and suggestions for the future. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2011;4(3):91-98.

11. O’Dunn-Orto A, Hartling L, Campbell S, Oswald AE. Teaching musculoskeletal clinical skills to medical trainees and physicians: a Best Evidence in Medical Education systematic review of strategies and their effectiveness: BEME Guide No. 18. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):93-102.

12. Wilcox T, Oyler J, Harada C, Utset T. Musculoskeletal exam and joint injection training for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):521-523.

13. Petron DJ, Greis PE, Aoki SK, et al. Use of knee magnetic resonance imaging by primary care physicians in patients aged 40 years and older. Sports Health. 2010;2(5):385-390.

14. Roberts TT, Singer N, Hushmendy S, et al. MRI for the evaluation of knee pain: comparison of ordering practices of primary care physicians and orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(9):709-714.

15. Wylie JD, Crim JR, Working ZM, Schmidt RL, Burks RT. Physician provider type influences utilization and diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(1):56-62.

16. Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC; 2013.

17. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Grotzke MP, Cannon GW. Mini-residency in musculoskeletal care: an interprofessional, mixed-methods educational initiative for primary care providers. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(2):275-279.

18. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Grotzke MP, Beck JP, Lawrence P, Cannon GW. “Mini-residency” in musculoskeletal care: a national continuing professional development program for primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1301-1307.

19. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Grotzke MP, et al. Effectiveness of an interprofessional and multidisciplinary musculoskeletal training program. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):398-404.

20. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Grotzke M, Cannon GW. Two-year impact of a continuing professional education program to train primary care providers to perform arthrocentesis. Presented at: 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting [Abstract 909]. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/two-year-impact-of-a-continuing-professional-education-program-to-train-primary-care-providers-to-perform-arthrocentesis. Accessed November 14, 2019.

21. Call MR, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Cannon GW, Battistone MJ. Impact of a musculoskeltal “mini-residency” continuing professional education program on knee mri orders by primary care providers. Presented at: 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting [Abstract 1011]. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/impact-of-a-musculoskeletal-aeoemini-residencyae%ef%bf%bd-continuing-professional-education-program-on-knee-mri-orders-by-primary-care-providers. Accessed November 14, 2019.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA SimLEARN. https://www.simlearn.va.gov/SIMLEARN/about_us.asp. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2019.

23. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Beck JP, Tashjian RZ, Cannon GW. Validity evidence for two objective structured clinical examination stations to evaluate core skills of the shoulder and knee assessment. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):13.

24. Artino AR Jr, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463-474.

25. Gehlbach H, Artino AR Jr. The survey checklist (Manifesto). Acad Med. 2018;93(3):360-366.

26. Haywood H, Pain H, Ryan S, Adams J. The continuing professional development for nurses and allied health professionals working within musculoskeletal services: a national UK survey. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11(2):63-70.

27. Haywood H, Pain H, Ryan S, Adams J. Continuing professional development: issues raised by nurses and allied health professionals working in musculoskeletal settings. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11(3):136-144.

28. Warburton L. Continuing professional development in musculoskeletal domains. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10(3):125-126.

29. Stansfield RB, Diponio L, Craig C, et al. Assessing musculoskeletal examination skills and diagnostic reasoning of 4th year medical students using a novel objective structured clinical exam. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):268.

30. Hose MK, Fontanesi J, Woytowitz M, Jarrin D, Quan A. Competency based clinical shoulder examination training improves physical exam, confidence, and knowledge in common shoulder conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1261-1265.

31. Bellamy N, Goldstein LD, Tekanoff RA. Continuing medical education-driven skills acquisition and impact on improved patient outcomes in family practice setting. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2000;20(1):52-61.

32. Macedo L, Sturpe DA, Haines ST, Layson-Wolf C, Tofade TS, McPherson ML. An objective structured teaching exercise (OSTE) for preceptor development. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7(5):627-634.

33. Sturpe DA, Schaivone KA. A primer for objective structured teaching exercises. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5):104.

34. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526.

35. Nelson SD, Nelson RE, Cannon GW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of training rural providers to identify and treat patients at risk for fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(12):2701-2707.

36. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786.

37. Institute of Medicine. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

38. Durning SJ, Dong T, LaRochelle JL, et al. The long-term career outcome study: lessons learned and implications for educational practice. Mil Med. 2015;180(suppl 4):164-170.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.

This program has several significant strengths: First, this is the most recent step in the development of a portfolio of innovative MSK CPD programs that were envisioned through a systematic process involving projections of cost-effectiveness, local pilot testing, and national expansion.17,18,35 Second, the SimLEARN program uses assessment tools for which validity evidence has been published, made available for reflective critique by educational scholars.19,23 This supports a national consortium of MSK educators, advancing clinical teaching and educational scholarship, and creating opportunities for interprofessional collaboration in congruence with the vision expressed in the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions,” as well as the 2016 update of the BEME recommendations for faculty development.36,37

Our experience with the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrates need for 2 distinct courses: (1) the MSK Clinician—serving PCPs seeking to develop their skills in evaluating and managing patients with MSK problems; and (2), the MSK Master Educator—for those with preexisting content expertise who would value the introduction to a national curriculum and connections with other MSK master educators. Both of these are now offered regularly through SimLEARN for VHA and US Department of Defense employees. The MSK Clinician program establishes competence in systematically evaluating and managing shoulder and knee MSK problems in an educational setting and prepares participants for subsequent clinical experiences where they can perform related procedures if desired, under appropriate supervision. The Master Educator program introduces partici pants to the clinician curriculum and provides the opportunity to develop an individualized plan for implementation of an MSK educational program at their home institutions. Participants are selected through a competitive application process, and funding for travel to attend the Master Educator program is provided by SimLEARN for participants who are accepted. Additionally, the Master Educator program serves as a repository for potential future SimLEARN MSK Clinician course faculty.

Limitations

The small number of participants may limit the validity of our conclusions. Although we included an OSCE to measure competence in performing and interpreting the shoulder exam, the durability of these skills is not known. Periodic postcourse OSCEs could help determine this and refresh and preserve accuracy in the performance of specific maneuvers. Second, although this experience was rated highly by participants, we do not know the impact of the program on their daily work or career trajectory. Sustained follow-up of learners, perhaps developed on the model of the Long-Term Career Outcome Study, may increase the value of this experience for future participants.38 This program appealed to a diverse pool of learners, with a broad range of precourse expertise and varied expectations of how course experiences would impact their future work and career development. Some clinical educator attendees came from tertiary care facilities affiliated with academic medical centers, held specialist or subspecialist credentials, and had formal responsibilities as leaders in HPE. Other clinical practitioner participants were solitary PCPs, often in rural or home-based settings; although they may have been eager to apply new knowledge and skills in patient care, they neither anticipated nor desired any role as an educator.

Conclusion

The initial SimLEARN MSK Training Program provides PCPs and clinician educators with rich learning experiences, increasing confidence in addressing MSK problems and competence in performing and interpreting a systematic physical examination of the shoulder. The success of this program has created new opportunities for practitioners seeking to strengthen clinical skills and for leaders in health professions education looking to disseminate similar trainings and connect with a national group of educators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the faculty and staff at the Veterans Health Administration SimLEARN National Simulation Center, the faculty of the Salt Lake City Musculoskeletal Mini-Residency program, the supportive leadership of the George E. Wahlen Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the efforts of Danielle Blake for logistical support and data entry.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.