User login

Lack of medical device tracking leaves patients vulnerable

.

As a result of this siloing of information, patients are not getting the expected benefits of a regulation finalized over a decade ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In 2013, the agency ordered companies to include unique device identifiers (UDIs) in plain-text and barcode format on some device labels, starting with implanted devices that are considered life-sustaining. The FDA said that tracking of UDI information would speed detection of complications linked to devices.

But identifiers are rarely on devices. At the time of the regulation creation, the FDA also said it expected this data would be integrated into EHRs. But only a few pioneer organizations such as Duke University and Mercy Health have so far attempted to track any UDI data in an organized way, researchers say.

Richard J. Kovacs, MD, the chief medical officer of the American College of Cardiology, contrasted the lack of useful implementation of UDI data with the speedy transfers of information that happen routinely in other industries. For example, employees of car rental agencies use handheld devices to gather detailed information about the vehicles being returned.

“But if you go to an emergency room with a medical device in your body, no one knows what it is or where it came from or anything about it,” Dr. Kovacs said in an interview.

Many physicians with expertise in device research have pushed for years to have insurers like Medicare require identification information on medical claims.

Even researchers face multiple obstacles in trying to investigate how well UDIs have been incorporated into EHRs and outcomes tied to certain devices.

In August, a Harvard team published a study in JAMA Internal Medicine, attempting to analyze the risks of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) devices. They reported an 11.6% risk for serious blood leaks with AFX Endovascular AAA System aneurysm devices, more than double the 5.7% risk estimated for competing products. The team selected EVAR devices for the study due in part to their known safety concerns. Endologix, the maker of the devices, declined to comment for this story.

The Harvard team used data from the Veterans Affairs health system, which is considered more well organized than most other health systems. But UDI information was found for only 19 of the 13,941 patients whose records were studied. In those cases, only partial information was included.

The researchers developed natural language processing tools, which they used to scrounge clinical notes for information about which devices patients received.

Using this method isn’t feasible for most clinicians, given that records from independent hospitals might not provide this kind of data and descriptions to search, according to the authors of an editorial accompanying the paper. Those researchers urged Congress to pass a law mandating inclusion of UDIs for all devices on claims forms as a condition for reimbursement by federal health care programs.

Setback for advocates

The movement toward UDI suffered a setback in June.

An influential, but little known federal advisory panel, the National Committee on Vital Health Statistics (NCVHS), opted to not recommend use of this information in claims, saying the FDA should consider the matter further.

Gaining an NCVHS recommendation would have been a win, said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-IA), and Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr. (D-NJ), in a December 2022 letter to the panel.

Including UDI data would let researchers track patients’ interactions with a health system and could be used to establish population-level correlations between a particular device and a long-term outcome or side effect, the lawmakers said.

That view had the support of at least one major maker of devices, Cook Group, which sells products for a variety of specialties, including cardiology.

In a comment to NCVHS, Cook urged for the inclusion identifiers in Medicare claims.

“While some have argued that the UDI is better suited for inclusion in the electronic health records, Cook believes this argument sets up a false choice between the two,” wrote Stephen L. Ferguson, JD, the chairman of Cook’s board. “Inclusion of the UDI in both electronic health records and claims forms will lead to a more robust system of real-world data.”

In contrast, AdvaMed, the trade group for device makers, told the NCVHS that it did not support adding the information to payment claims submissions, instead just supporting the inclusion in EHRs.

Dr. Kovacs of the ACC said one potential drawback to more transparency could be challenges in interpreting reports of complications in certain cases, at least initially. Reports about a flaw or even a suspected flaw in a device might lead patients to become concerned about their implanted devices, potentially registering unfounded complaints.

But this concern can be addressed through using “scientific rigor and safeguards” and is outweighed by the potential safety benefits for patients, Dr. Kovacs said.

Patients should ask health care systems to track and share information about their implanted devices, Dr. Kovacs suggested.

“I feel it would be my right to demand that that device information follows my electronic medical record, so that it’s readily available to anyone who’s taking care of me,” Dr. Kovacs said. “They would know what it is that’s in me, whether it’s a lens in my eye or a prosthesis in my hip or a highly complicated implantable cardiac electronic device.”

The Harvard study was supported by the FDA and National Institutes of Health. Authors of the study reported receiving fees from the FDA, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Authors of the editorial reported past and present connections with F-Prime Capital, FDA, Johnson & Johnson, the Medical Devices Innovation Consortium; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Arnold Ventures, as well being an expert witness at in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen. Authors of the Viewpoint reported past and present connections with the National Evaluation System for Health Technology Coordinating Center (NESTcc), which is part of the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC); AIM North America UDI Advisory Committee, Mass General Brigham, Arnold Ventures; the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review California Technology Assessment Forum; Yale University, Johnson & Johnson, FD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; as well as having been an expert witness in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

As a result of this siloing of information, patients are not getting the expected benefits of a regulation finalized over a decade ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In 2013, the agency ordered companies to include unique device identifiers (UDIs) in plain-text and barcode format on some device labels, starting with implanted devices that are considered life-sustaining. The FDA said that tracking of UDI information would speed detection of complications linked to devices.

But identifiers are rarely on devices. At the time of the regulation creation, the FDA also said it expected this data would be integrated into EHRs. But only a few pioneer organizations such as Duke University and Mercy Health have so far attempted to track any UDI data in an organized way, researchers say.

Richard J. Kovacs, MD, the chief medical officer of the American College of Cardiology, contrasted the lack of useful implementation of UDI data with the speedy transfers of information that happen routinely in other industries. For example, employees of car rental agencies use handheld devices to gather detailed information about the vehicles being returned.

“But if you go to an emergency room with a medical device in your body, no one knows what it is or where it came from or anything about it,” Dr. Kovacs said in an interview.

Many physicians with expertise in device research have pushed for years to have insurers like Medicare require identification information on medical claims.

Even researchers face multiple obstacles in trying to investigate how well UDIs have been incorporated into EHRs and outcomes tied to certain devices.

In August, a Harvard team published a study in JAMA Internal Medicine, attempting to analyze the risks of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) devices. They reported an 11.6% risk for serious blood leaks with AFX Endovascular AAA System aneurysm devices, more than double the 5.7% risk estimated for competing products. The team selected EVAR devices for the study due in part to their known safety concerns. Endologix, the maker of the devices, declined to comment for this story.

The Harvard team used data from the Veterans Affairs health system, which is considered more well organized than most other health systems. But UDI information was found for only 19 of the 13,941 patients whose records were studied. In those cases, only partial information was included.

The researchers developed natural language processing tools, which they used to scrounge clinical notes for information about which devices patients received.

Using this method isn’t feasible for most clinicians, given that records from independent hospitals might not provide this kind of data and descriptions to search, according to the authors of an editorial accompanying the paper. Those researchers urged Congress to pass a law mandating inclusion of UDIs for all devices on claims forms as a condition for reimbursement by federal health care programs.

Setback for advocates

The movement toward UDI suffered a setback in June.

An influential, but little known federal advisory panel, the National Committee on Vital Health Statistics (NCVHS), opted to not recommend use of this information in claims, saying the FDA should consider the matter further.

Gaining an NCVHS recommendation would have been a win, said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-IA), and Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr. (D-NJ), in a December 2022 letter to the panel.

Including UDI data would let researchers track patients’ interactions with a health system and could be used to establish population-level correlations between a particular device and a long-term outcome or side effect, the lawmakers said.

That view had the support of at least one major maker of devices, Cook Group, which sells products for a variety of specialties, including cardiology.

In a comment to NCVHS, Cook urged for the inclusion identifiers in Medicare claims.

“While some have argued that the UDI is better suited for inclusion in the electronic health records, Cook believes this argument sets up a false choice between the two,” wrote Stephen L. Ferguson, JD, the chairman of Cook’s board. “Inclusion of the UDI in both electronic health records and claims forms will lead to a more robust system of real-world data.”

In contrast, AdvaMed, the trade group for device makers, told the NCVHS that it did not support adding the information to payment claims submissions, instead just supporting the inclusion in EHRs.

Dr. Kovacs of the ACC said one potential drawback to more transparency could be challenges in interpreting reports of complications in certain cases, at least initially. Reports about a flaw or even a suspected flaw in a device might lead patients to become concerned about their implanted devices, potentially registering unfounded complaints.

But this concern can be addressed through using “scientific rigor and safeguards” and is outweighed by the potential safety benefits for patients, Dr. Kovacs said.

Patients should ask health care systems to track and share information about their implanted devices, Dr. Kovacs suggested.

“I feel it would be my right to demand that that device information follows my electronic medical record, so that it’s readily available to anyone who’s taking care of me,” Dr. Kovacs said. “They would know what it is that’s in me, whether it’s a lens in my eye or a prosthesis in my hip or a highly complicated implantable cardiac electronic device.”

The Harvard study was supported by the FDA and National Institutes of Health. Authors of the study reported receiving fees from the FDA, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Authors of the editorial reported past and present connections with F-Prime Capital, FDA, Johnson & Johnson, the Medical Devices Innovation Consortium; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Arnold Ventures, as well being an expert witness at in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen. Authors of the Viewpoint reported past and present connections with the National Evaluation System for Health Technology Coordinating Center (NESTcc), which is part of the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC); AIM North America UDI Advisory Committee, Mass General Brigham, Arnold Ventures; the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review California Technology Assessment Forum; Yale University, Johnson & Johnson, FD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; as well as having been an expert witness in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

As a result of this siloing of information, patients are not getting the expected benefits of a regulation finalized over a decade ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In 2013, the agency ordered companies to include unique device identifiers (UDIs) in plain-text and barcode format on some device labels, starting with implanted devices that are considered life-sustaining. The FDA said that tracking of UDI information would speed detection of complications linked to devices.

But identifiers are rarely on devices. At the time of the regulation creation, the FDA also said it expected this data would be integrated into EHRs. But only a few pioneer organizations such as Duke University and Mercy Health have so far attempted to track any UDI data in an organized way, researchers say.

Richard J. Kovacs, MD, the chief medical officer of the American College of Cardiology, contrasted the lack of useful implementation of UDI data with the speedy transfers of information that happen routinely in other industries. For example, employees of car rental agencies use handheld devices to gather detailed information about the vehicles being returned.

“But if you go to an emergency room with a medical device in your body, no one knows what it is or where it came from or anything about it,” Dr. Kovacs said in an interview.

Many physicians with expertise in device research have pushed for years to have insurers like Medicare require identification information on medical claims.

Even researchers face multiple obstacles in trying to investigate how well UDIs have been incorporated into EHRs and outcomes tied to certain devices.

In August, a Harvard team published a study in JAMA Internal Medicine, attempting to analyze the risks of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) devices. They reported an 11.6% risk for serious blood leaks with AFX Endovascular AAA System aneurysm devices, more than double the 5.7% risk estimated for competing products. The team selected EVAR devices for the study due in part to their known safety concerns. Endologix, the maker of the devices, declined to comment for this story.

The Harvard team used data from the Veterans Affairs health system, which is considered more well organized than most other health systems. But UDI information was found for only 19 of the 13,941 patients whose records were studied. In those cases, only partial information was included.

The researchers developed natural language processing tools, which they used to scrounge clinical notes for information about which devices patients received.

Using this method isn’t feasible for most clinicians, given that records from independent hospitals might not provide this kind of data and descriptions to search, according to the authors of an editorial accompanying the paper. Those researchers urged Congress to pass a law mandating inclusion of UDIs for all devices on claims forms as a condition for reimbursement by federal health care programs.

Setback for advocates

The movement toward UDI suffered a setback in June.

An influential, but little known federal advisory panel, the National Committee on Vital Health Statistics (NCVHS), opted to not recommend use of this information in claims, saying the FDA should consider the matter further.

Gaining an NCVHS recommendation would have been a win, said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-IA), and Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr. (D-NJ), in a December 2022 letter to the panel.

Including UDI data would let researchers track patients’ interactions with a health system and could be used to establish population-level correlations between a particular device and a long-term outcome or side effect, the lawmakers said.

That view had the support of at least one major maker of devices, Cook Group, which sells products for a variety of specialties, including cardiology.

In a comment to NCVHS, Cook urged for the inclusion identifiers in Medicare claims.

“While some have argued that the UDI is better suited for inclusion in the electronic health records, Cook believes this argument sets up a false choice between the two,” wrote Stephen L. Ferguson, JD, the chairman of Cook’s board. “Inclusion of the UDI in both electronic health records and claims forms will lead to a more robust system of real-world data.”

In contrast, AdvaMed, the trade group for device makers, told the NCVHS that it did not support adding the information to payment claims submissions, instead just supporting the inclusion in EHRs.

Dr. Kovacs of the ACC said one potential drawback to more transparency could be challenges in interpreting reports of complications in certain cases, at least initially. Reports about a flaw or even a suspected flaw in a device might lead patients to become concerned about their implanted devices, potentially registering unfounded complaints.

But this concern can be addressed through using “scientific rigor and safeguards” and is outweighed by the potential safety benefits for patients, Dr. Kovacs said.

Patients should ask health care systems to track and share information about their implanted devices, Dr. Kovacs suggested.

“I feel it would be my right to demand that that device information follows my electronic medical record, so that it’s readily available to anyone who’s taking care of me,” Dr. Kovacs said. “They would know what it is that’s in me, whether it’s a lens in my eye or a prosthesis in my hip or a highly complicated implantable cardiac electronic device.”

The Harvard study was supported by the FDA and National Institutes of Health. Authors of the study reported receiving fees from the FDA, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Authors of the editorial reported past and present connections with F-Prime Capital, FDA, Johnson & Johnson, the Medical Devices Innovation Consortium; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Arnold Ventures, as well being an expert witness at in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen. Authors of the Viewpoint reported past and present connections with the National Evaluation System for Health Technology Coordinating Center (NESTcc), which is part of the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC); AIM North America UDI Advisory Committee, Mass General Brigham, Arnold Ventures; the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review California Technology Assessment Forum; Yale University, Johnson & Johnson, FD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; as well as having been an expert witness in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rifampin for Prosthetic Joint Infections: Lessons Learned Over 20 Years at a VA Medical Center

Orthopedic implants are frequently used to repair fractures and replace joints. The number of total joint replacements is high, with > 1 million total hip (THA) and total knee (TKA) arthroplasties performed in the United States each year.1 While most joint arthroplasties are successful and significantly improve patient quality of life, a small proportion become infected.2 Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) causes substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly among older patients, and is difficult and costly to treat.3

The historic gold standard treatment for PJI is a 2-stage replacement, wherein the prosthesis is removed in one procedure and a new prosthesis is implanted in a second procedure after an extended course of antibiotics. This approach requires the patient to undergo 2 major procedures and spend considerable time without a functioning prosthesis, contributing to immobility and deconditioning. This option is difficult for frail or older patients and is associated with high medical costs.4

In 1998, a novel method of treatment known as debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) was evaluated in a small, randomized controlled trial.5 This study used a unique antimicrobial approach: the administration of ciprofloxacin plus either rifampin or placebo for 3 to 6 months, combined with a single surgical debridement. Eliminating a second surgical procedure and largely relying on oral antimicrobials reduces surgical risks and decreases costs.4 Current guidelines endorse DAIR with rifampin and a second antibiotic for patients diagnosed with PJI within about 30 days of prosthesis implantation who have a well-fixed implant without evidence of a sinus tract.6 Clinical trial data demonstrate that this approach is > 90% effective in patients with a well-fixed prosthesis and acute staphylococcal PJI.3,7

Thus far, clinical trials examining this approach have been small and did not include veterans who are typically older and have more comorbidities.8 The Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System (MVAHCS) infectious disease section has implemented the rifampin-based DAIR approach for orthopedic device-related infections since this approach was first described in 1998 but has not systematically evaluated its effectiveness or whether there are areas for improvement.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent DAIR combined with a rifampin-containing regimen at the MVAHCS from January 1, 2001, through June 30, 2021. Inclusion required a diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection and treatment with DAIR followed by antimicrobial therapy that included rifampin for 1 to 6 months. PJI was defined by meeting ≥ 1 of the following criteria: (1) isolation of the same microorganism from ≥ 2 cultures from joint aspirates or intraoperative tissue specimens; (2) purulence surrounding the prosthesis at the time of surgery; (3) acute inflammation consistent with infection on histopathological examination or periprosthetic tissue; or (4) presence of a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis.

All cases of orthopedic device infection managed with DAIR and rifampin were included, regardless of implant stability, age of the implant at the time of symptom onset, presence of a sinus tract, or infecting microorganism. Exclusion criteria included patients who started or finished PJI treatment at another facility, were lost to follow-up, discontinued rifampin, died within 1 year of completing antibiotic therapy due to reasons unrelated to treatment failure, received rifampin for < 50% of their antimicrobial treatment course, had complete hardware removal, or had < 1 year between the completion of antimicrobial therapy and the time of data collection.

Management of DAIR procedures at the MVAHCS involves evaluating the fixation of the prosthesis, tissue sampling for microbiological analysis, and thorough debridement of infected tissue. Following debridement, a course of IV antibiotics is administered before initiating oral antibiotic therapy. To protect against resistance, rifampin is combined with another antibiotic typically from the fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, or cephalosporin class. Current guidelines suggest 3 and 6 months of oral antibiotics for prosthetic hip and knee infections, respectively.6

Treatment Outcomes

The primary outcome was treatment success, defined as meeting all of the following: (1) lack of clinical signs and symptoms of infection; (2) absence of radiological signs of loosening or infection within 1 year after the conclusion of treatment; and (3) absence of additional PJI treatment interventions for the prosthesis of concern within 1 year after completing the original antibiotic treatment.

Treatment failure was defined as meeting any of the following: (1) recurrence of PJI (original strain or different microorganism) within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; (2) death attributed to PJI anytime after the initial debridement; (3) removal of the prosthetic joint within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; or (4) long-term antibiotic use to suppress the PJI after the completion of the initial antibiotic therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to define the baseline characteristics of patients receiving rifampin therapy for orthopedic implant infections at the MVAHCS. Variables analyzed were age, sex, race and ethnicity, type of implant, age of implant, duration of symptoms, comorbidities (diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis), and presence of chronic infection. Patients were classified as having a chronic infection if they received previous infection treatment (antibiotics or surgery) for the orthopedic device in question. We created this category because patients with persistent infection after a medical or surgical attempt at treatment are likely to have a higher probability of treatment failure compared with those with no prior therapy. Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated using clinical information present at the onset of infection.9 Fisher exact test was used to assess differences between categorical variables, and an independent t test was used to assess differences in continuous variables. P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

To assess the ability of a rifampin-based regimen to achieve a cure of PJI, we grouped participants into 2 categories: those with an intent to cure strategy and those without intent to cure based on documentation in the electronic health record (EHR). Participants who were prescribed rifampin with the documented goal of prosthesis retention with no further suppressive antibiotics were included in the intent-to-cure group, the primary focus of this study. Those excluded from the intent-to-cure group were given rifampin and another antibiotic, but there was a documented plan of either ongoing chronic suppression or eventual explantation; these participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Analysis of treatment success and failure was limited to the intent-to-cure group, whereas both groups were included for assessment of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment duration. This project was reviewed by the MVAHCS Institutional Review Board and determined to be a quality improvement initiative and to not meet the definition of research, and as such did not require review; it was reviewed and approved by the MVAHCS Research and Development Committee.

RESULTS

A total of 538 patients were identified who simultaneously received rifampin and another oral antibiotic between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2021.

Forty-two participants (54%) had Staphylococcus aureus and 31 participants (40%) had coagulase-negative staphylococci infections, while 11 gram-negative organisms (14%) and 6 gram-positive anaerobic cocci (8%) infections were noted. Cutibacterium acnes and Streptococcus agalactiae were each found in 3 participants (4% of), and diphtheroids (not further identified) was found on 2 participants (3%). Candida albicans was identified in a single participant (1%), along with coagulase-negative staphylococci, and 2 participants (3%) had no identified organisms. There were multiple organisms isolated from 20 patients (26%).

Fifty participants had clear documentation in their EHR that cure of infection was the goal, meeting the criteria for the intent-to-cure group. The remaining 28 participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Success and failure rates were only measured in the intent-to-cure group, as by definition the without-intent-to-cure group patients would meet the criteria for failure (removal of prosthesis or long-term antibiotic use). The without-intent-to-cure group had a higher median age than the intent-to-cure group (69 years vs 64 years, P = .24) and a higher proportion of male participants (96% vs 80%, P = .09). The median (IQR) implant age of 11 months (1.0-50.5) in the without-intent-to-cure group was also higher than the median implant age of 1 month (0.6-22.0) in the primary group (P = .22). In the without-intent-to-cure group, 19 participants (68%) had a chronic infection, compared with 11 (22%) in the intent-to-cure group (P < .001).

The mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index in the without-intent-to-cure group was 2.5 (1.3) compared with 1.9 (1.4) in the intent-to-cure group (P = .09). There was no significant difference in the type of implant or microbiology of the infecting organism between the 2 groups, although it should be noted that in the intent-to-cure group, 48 patients (96%) had Staphylococcus aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated.

The median (IQR) dosage of rifampin was 600 mg (300-900). The secondary oral antibiotics used most often were 36 fluoroquinolones (46%) followed by 20 tetracyclines (26%), 6 cephalosporins (8%), and 6 penicillins (8%). Additionally, 6 participants (8%) received IV vancomycin, and 1 participant (1%) was given an oral antifungal in addition to a fluoroquinolone because cultures revealed bacterial and fungal growth. The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3 months (1.4-3.0). The mean (SD) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3.6 (2.4) months for TKA infections and 2.4 (0.9) months for THA infections.

Clinical Outcome

Forty-one intent-to-cure group participants (82%) experienced treatment success. We further subdivided the intent-to-cure group by implant age. Participants whose implant was < 2 months old had a success rate of 93%, whereas patients whose implant was older had a success rate of 65% (P = .02).

Secondary Outcomes

The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial treatment was 3 months (1.4-3.0) for the 38 patients with TKA-related infections and 3 months (1.4-6.0) for the 29 patients with THA infections. AEs were recorded in 24 (31%) of all study participants. Of those with AEs, the average number reported per patient was 1.6. Diarrhea, gastric upset, and nausea were each reported 7 times, accounting for 87% of all recorded AEs. Five participants reported having a rash while on antibiotics, and 2 experienced dysgeusia. One participant reported developing a yeast infection and another experienced vaginitis.

DISCUSSION

Among patients with orthopedic implant infections treated with intent to cure using a rifampin-containing antibiotic regimen at the MVAHCS, 82% had clinical success. Although this is lower than the success rates reported in clinical trials, this is not entirely unexpected.5,7 In most clinical trials studying DAIR and rifampin for PJI, patients are excluded if they do not have an acute staphylococcal infection in the setting of a well-fixed prosthesis without evidence of a sinus tract. Such exclusion criteria were not present in our retrospective study, which was designed to evaluate the real-world practice patterns at this facility. The population at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is older, more frail, and with more comorbid conditions than populations in prior studies. It is possible that patients with characteristics that would have caused them to be excluded from a clinical trial would be less likely to receive rifampin therapy with the intent to cure. This is suggested by the significantly higher prevalence of chronic infections (68%) in the without-intent-to-cure group compared with 22% in the intent-to-cure group. However, there were reasonably high proportions of participants included in the intent-to-cure group who did have conditions that would have led to their exclusion from prior trials, such as chronic infection (22%) and implant age ≥ 2 months (40%).

When evaluating participants by the age of their implant, treatment success rose to 93% for patients with implants < 2 months old compared with 65% for patients with older implants. This suggests that participants with a newer implant or more recent infection have a greater likelihood of successful treatment, which is consistent with the results of previous clinical trials.5,10 Considering how difficult multiple surgeries can be for older adult patients with comorbidities, we suggest that DAIR with a rifampin-containing regimen be considered as the primary treatment option for early PJIs at the MVAHCS. We also note inconsistent adherence to IDSA treatment guidelines on rifampin therapy, in that patients without intent to cure were prescribed a regimen including rifampin. This may reflect appropriate variability in the care of individual patients but may also offer an opportunity to change processes to improve care.

Limitations

Our analysis has limitations. As with any retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of a specific antibiotic, we were not able to attribute specific outcomes to the antibiotic of interest. Since the choice of antibiotics was left to the treating health care practitioner, therapy was not standardized, and because this was a retrospective study, causal relationships could not be inferred. Our analysis was also limited by the lack of intent to cure in 28 participants (36%), which could be an indication of practitioner bias in therapy selection or characteristic differences between the 2 groups. We looked for signs of infection failure 1 year after the completion of antimicrobial therapy, but longer follow-up could have led to higher rates of failure. Also, while participants’ infections were considered cured if they never sought further medical care for the infection at the MVAHCS, it is possible that patients could have sought care at another facility. We note that 9 patients were excluded because they were unable to complete a treatment course due to rifampin AEs, meaning that the success rates reported here reflect the success that may be expected if a patient can tolerate and complete a rifampin-based regimen. This study was conducted in a single VA hospital and may not be generalizable to nonveterans or veterans seeking care at other facilities.

Conclusions

DAIR followed by a short course of IV antibiotics and an oral regimen including rifampin and another antimicrobial is a reasonable option for veterans with acute staphylococcal orthopedic device infections at the MVAHCS. Patients with a well-placed prosthesis and an acute infection seem especially well suited for this treatment, and treatment with intent to cure should be pursued in patients who meet the criteria for rifampin therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Stensgard, PharmD, for assistance in compiling the list of patients receiving rifampin and another antimicrobial.

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

2. Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):386-394. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61798-0

3. Zhan C, Kaczmarek R, Loyo-Berrios N, Sangl J, Bright RA. Incidence and short-term outcomes of primary and revision hip replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):526-533. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00952

4. Fisman DN, Reilly DT, Karchmer AW, Goldie SJ. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 management strategies for infected total hip arthroplasty in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):419-430. doi:10.1086/318502

5. Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1537-1541. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1537

6. Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):e1-e25. doi:10.1093/cid/cis803

7. Lora-Tamayo J, Euba G, Cobo J, et al. Short- versus long-duration levofloxacin plus rifampicin for acute staphylococcal prosthetic joint infection managed with implant retention: a randomised clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):310-316. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.021

8. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

9. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

10. Vilchez F, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, et al. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in early post-surgical prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus treated with debridement. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):439-444. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03244.x

Orthopedic implants are frequently used to repair fractures and replace joints. The number of total joint replacements is high, with > 1 million total hip (THA) and total knee (TKA) arthroplasties performed in the United States each year.1 While most joint arthroplasties are successful and significantly improve patient quality of life, a small proportion become infected.2 Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) causes substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly among older patients, and is difficult and costly to treat.3

The historic gold standard treatment for PJI is a 2-stage replacement, wherein the prosthesis is removed in one procedure and a new prosthesis is implanted in a second procedure after an extended course of antibiotics. This approach requires the patient to undergo 2 major procedures and spend considerable time without a functioning prosthesis, contributing to immobility and deconditioning. This option is difficult for frail or older patients and is associated with high medical costs.4

In 1998, a novel method of treatment known as debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) was evaluated in a small, randomized controlled trial.5 This study used a unique antimicrobial approach: the administration of ciprofloxacin plus either rifampin or placebo for 3 to 6 months, combined with a single surgical debridement. Eliminating a second surgical procedure and largely relying on oral antimicrobials reduces surgical risks and decreases costs.4 Current guidelines endorse DAIR with rifampin and a second antibiotic for patients diagnosed with PJI within about 30 days of prosthesis implantation who have a well-fixed implant without evidence of a sinus tract.6 Clinical trial data demonstrate that this approach is > 90% effective in patients with a well-fixed prosthesis and acute staphylococcal PJI.3,7

Thus far, clinical trials examining this approach have been small and did not include veterans who are typically older and have more comorbidities.8 The Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System (MVAHCS) infectious disease section has implemented the rifampin-based DAIR approach for orthopedic device-related infections since this approach was first described in 1998 but has not systematically evaluated its effectiveness or whether there are areas for improvement.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent DAIR combined with a rifampin-containing regimen at the MVAHCS from January 1, 2001, through June 30, 2021. Inclusion required a diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection and treatment with DAIR followed by antimicrobial therapy that included rifampin for 1 to 6 months. PJI was defined by meeting ≥ 1 of the following criteria: (1) isolation of the same microorganism from ≥ 2 cultures from joint aspirates or intraoperative tissue specimens; (2) purulence surrounding the prosthesis at the time of surgery; (3) acute inflammation consistent with infection on histopathological examination or periprosthetic tissue; or (4) presence of a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis.

All cases of orthopedic device infection managed with DAIR and rifampin were included, regardless of implant stability, age of the implant at the time of symptom onset, presence of a sinus tract, or infecting microorganism. Exclusion criteria included patients who started or finished PJI treatment at another facility, were lost to follow-up, discontinued rifampin, died within 1 year of completing antibiotic therapy due to reasons unrelated to treatment failure, received rifampin for < 50% of their antimicrobial treatment course, had complete hardware removal, or had < 1 year between the completion of antimicrobial therapy and the time of data collection.

Management of DAIR procedures at the MVAHCS involves evaluating the fixation of the prosthesis, tissue sampling for microbiological analysis, and thorough debridement of infected tissue. Following debridement, a course of IV antibiotics is administered before initiating oral antibiotic therapy. To protect against resistance, rifampin is combined with another antibiotic typically from the fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, or cephalosporin class. Current guidelines suggest 3 and 6 months of oral antibiotics for prosthetic hip and knee infections, respectively.6

Treatment Outcomes

The primary outcome was treatment success, defined as meeting all of the following: (1) lack of clinical signs and symptoms of infection; (2) absence of radiological signs of loosening or infection within 1 year after the conclusion of treatment; and (3) absence of additional PJI treatment interventions for the prosthesis of concern within 1 year after completing the original antibiotic treatment.

Treatment failure was defined as meeting any of the following: (1) recurrence of PJI (original strain or different microorganism) within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; (2) death attributed to PJI anytime after the initial debridement; (3) removal of the prosthetic joint within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; or (4) long-term antibiotic use to suppress the PJI after the completion of the initial antibiotic therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to define the baseline characteristics of patients receiving rifampin therapy for orthopedic implant infections at the MVAHCS. Variables analyzed were age, sex, race and ethnicity, type of implant, age of implant, duration of symptoms, comorbidities (diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis), and presence of chronic infection. Patients were classified as having a chronic infection if they received previous infection treatment (antibiotics or surgery) for the orthopedic device in question. We created this category because patients with persistent infection after a medical or surgical attempt at treatment are likely to have a higher probability of treatment failure compared with those with no prior therapy. Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated using clinical information present at the onset of infection.9 Fisher exact test was used to assess differences between categorical variables, and an independent t test was used to assess differences in continuous variables. P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

To assess the ability of a rifampin-based regimen to achieve a cure of PJI, we grouped participants into 2 categories: those with an intent to cure strategy and those without intent to cure based on documentation in the electronic health record (EHR). Participants who were prescribed rifampin with the documented goal of prosthesis retention with no further suppressive antibiotics were included in the intent-to-cure group, the primary focus of this study. Those excluded from the intent-to-cure group were given rifampin and another antibiotic, but there was a documented plan of either ongoing chronic suppression or eventual explantation; these participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Analysis of treatment success and failure was limited to the intent-to-cure group, whereas both groups were included for assessment of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment duration. This project was reviewed by the MVAHCS Institutional Review Board and determined to be a quality improvement initiative and to not meet the definition of research, and as such did not require review; it was reviewed and approved by the MVAHCS Research and Development Committee.

RESULTS

A total of 538 patients were identified who simultaneously received rifampin and another oral antibiotic between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2021.

Forty-two participants (54%) had Staphylococcus aureus and 31 participants (40%) had coagulase-negative staphylococci infections, while 11 gram-negative organisms (14%) and 6 gram-positive anaerobic cocci (8%) infections were noted. Cutibacterium acnes and Streptococcus agalactiae were each found in 3 participants (4% of), and diphtheroids (not further identified) was found on 2 participants (3%). Candida albicans was identified in a single participant (1%), along with coagulase-negative staphylococci, and 2 participants (3%) had no identified organisms. There were multiple organisms isolated from 20 patients (26%).

Fifty participants had clear documentation in their EHR that cure of infection was the goal, meeting the criteria for the intent-to-cure group. The remaining 28 participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Success and failure rates were only measured in the intent-to-cure group, as by definition the without-intent-to-cure group patients would meet the criteria for failure (removal of prosthesis or long-term antibiotic use). The without-intent-to-cure group had a higher median age than the intent-to-cure group (69 years vs 64 years, P = .24) and a higher proportion of male participants (96% vs 80%, P = .09). The median (IQR) implant age of 11 months (1.0-50.5) in the without-intent-to-cure group was also higher than the median implant age of 1 month (0.6-22.0) in the primary group (P = .22). In the without-intent-to-cure group, 19 participants (68%) had a chronic infection, compared with 11 (22%) in the intent-to-cure group (P < .001).

The mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index in the without-intent-to-cure group was 2.5 (1.3) compared with 1.9 (1.4) in the intent-to-cure group (P = .09). There was no significant difference in the type of implant or microbiology of the infecting organism between the 2 groups, although it should be noted that in the intent-to-cure group, 48 patients (96%) had Staphylococcus aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated.

The median (IQR) dosage of rifampin was 600 mg (300-900). The secondary oral antibiotics used most often were 36 fluoroquinolones (46%) followed by 20 tetracyclines (26%), 6 cephalosporins (8%), and 6 penicillins (8%). Additionally, 6 participants (8%) received IV vancomycin, and 1 participant (1%) was given an oral antifungal in addition to a fluoroquinolone because cultures revealed bacterial and fungal growth. The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3 months (1.4-3.0). The mean (SD) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3.6 (2.4) months for TKA infections and 2.4 (0.9) months for THA infections.

Clinical Outcome

Forty-one intent-to-cure group participants (82%) experienced treatment success. We further subdivided the intent-to-cure group by implant age. Participants whose implant was < 2 months old had a success rate of 93%, whereas patients whose implant was older had a success rate of 65% (P = .02).

Secondary Outcomes

The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial treatment was 3 months (1.4-3.0) for the 38 patients with TKA-related infections and 3 months (1.4-6.0) for the 29 patients with THA infections. AEs were recorded in 24 (31%) of all study participants. Of those with AEs, the average number reported per patient was 1.6. Diarrhea, gastric upset, and nausea were each reported 7 times, accounting for 87% of all recorded AEs. Five participants reported having a rash while on antibiotics, and 2 experienced dysgeusia. One participant reported developing a yeast infection and another experienced vaginitis.

DISCUSSION

Among patients with orthopedic implant infections treated with intent to cure using a rifampin-containing antibiotic regimen at the MVAHCS, 82% had clinical success. Although this is lower than the success rates reported in clinical trials, this is not entirely unexpected.5,7 In most clinical trials studying DAIR and rifampin for PJI, patients are excluded if they do not have an acute staphylococcal infection in the setting of a well-fixed prosthesis without evidence of a sinus tract. Such exclusion criteria were not present in our retrospective study, which was designed to evaluate the real-world practice patterns at this facility. The population at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is older, more frail, and with more comorbid conditions than populations in prior studies. It is possible that patients with characteristics that would have caused them to be excluded from a clinical trial would be less likely to receive rifampin therapy with the intent to cure. This is suggested by the significantly higher prevalence of chronic infections (68%) in the without-intent-to-cure group compared with 22% in the intent-to-cure group. However, there were reasonably high proportions of participants included in the intent-to-cure group who did have conditions that would have led to their exclusion from prior trials, such as chronic infection (22%) and implant age ≥ 2 months (40%).

When evaluating participants by the age of their implant, treatment success rose to 93% for patients with implants < 2 months old compared with 65% for patients with older implants. This suggests that participants with a newer implant or more recent infection have a greater likelihood of successful treatment, which is consistent with the results of previous clinical trials.5,10 Considering how difficult multiple surgeries can be for older adult patients with comorbidities, we suggest that DAIR with a rifampin-containing regimen be considered as the primary treatment option for early PJIs at the MVAHCS. We also note inconsistent adherence to IDSA treatment guidelines on rifampin therapy, in that patients without intent to cure were prescribed a regimen including rifampin. This may reflect appropriate variability in the care of individual patients but may also offer an opportunity to change processes to improve care.

Limitations

Our analysis has limitations. As with any retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of a specific antibiotic, we were not able to attribute specific outcomes to the antibiotic of interest. Since the choice of antibiotics was left to the treating health care practitioner, therapy was not standardized, and because this was a retrospective study, causal relationships could not be inferred. Our analysis was also limited by the lack of intent to cure in 28 participants (36%), which could be an indication of practitioner bias in therapy selection or characteristic differences between the 2 groups. We looked for signs of infection failure 1 year after the completion of antimicrobial therapy, but longer follow-up could have led to higher rates of failure. Also, while participants’ infections were considered cured if they never sought further medical care for the infection at the MVAHCS, it is possible that patients could have sought care at another facility. We note that 9 patients were excluded because they were unable to complete a treatment course due to rifampin AEs, meaning that the success rates reported here reflect the success that may be expected if a patient can tolerate and complete a rifampin-based regimen. This study was conducted in a single VA hospital and may not be generalizable to nonveterans or veterans seeking care at other facilities.

Conclusions

DAIR followed by a short course of IV antibiotics and an oral regimen including rifampin and another antimicrobial is a reasonable option for veterans with acute staphylococcal orthopedic device infections at the MVAHCS. Patients with a well-placed prosthesis and an acute infection seem especially well suited for this treatment, and treatment with intent to cure should be pursued in patients who meet the criteria for rifampin therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Stensgard, PharmD, for assistance in compiling the list of patients receiving rifampin and another antimicrobial.

Orthopedic implants are frequently used to repair fractures and replace joints. The number of total joint replacements is high, with > 1 million total hip (THA) and total knee (TKA) arthroplasties performed in the United States each year.1 While most joint arthroplasties are successful and significantly improve patient quality of life, a small proportion become infected.2 Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) causes substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly among older patients, and is difficult and costly to treat.3

The historic gold standard treatment for PJI is a 2-stage replacement, wherein the prosthesis is removed in one procedure and a new prosthesis is implanted in a second procedure after an extended course of antibiotics. This approach requires the patient to undergo 2 major procedures and spend considerable time without a functioning prosthesis, contributing to immobility and deconditioning. This option is difficult for frail or older patients and is associated with high medical costs.4

In 1998, a novel method of treatment known as debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) was evaluated in a small, randomized controlled trial.5 This study used a unique antimicrobial approach: the administration of ciprofloxacin plus either rifampin or placebo for 3 to 6 months, combined with a single surgical debridement. Eliminating a second surgical procedure and largely relying on oral antimicrobials reduces surgical risks and decreases costs.4 Current guidelines endorse DAIR with rifampin and a second antibiotic for patients diagnosed with PJI within about 30 days of prosthesis implantation who have a well-fixed implant without evidence of a sinus tract.6 Clinical trial data demonstrate that this approach is > 90% effective in patients with a well-fixed prosthesis and acute staphylococcal PJI.3,7

Thus far, clinical trials examining this approach have been small and did not include veterans who are typically older and have more comorbidities.8 The Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System (MVAHCS) infectious disease section has implemented the rifampin-based DAIR approach for orthopedic device-related infections since this approach was first described in 1998 but has not systematically evaluated its effectiveness or whether there are areas for improvement.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent DAIR combined with a rifampin-containing regimen at the MVAHCS from January 1, 2001, through June 30, 2021. Inclusion required a diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection and treatment with DAIR followed by antimicrobial therapy that included rifampin for 1 to 6 months. PJI was defined by meeting ≥ 1 of the following criteria: (1) isolation of the same microorganism from ≥ 2 cultures from joint aspirates or intraoperative tissue specimens; (2) purulence surrounding the prosthesis at the time of surgery; (3) acute inflammation consistent with infection on histopathological examination or periprosthetic tissue; or (4) presence of a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis.

All cases of orthopedic device infection managed with DAIR and rifampin were included, regardless of implant stability, age of the implant at the time of symptom onset, presence of a sinus tract, or infecting microorganism. Exclusion criteria included patients who started or finished PJI treatment at another facility, were lost to follow-up, discontinued rifampin, died within 1 year of completing antibiotic therapy due to reasons unrelated to treatment failure, received rifampin for < 50% of their antimicrobial treatment course, had complete hardware removal, or had < 1 year between the completion of antimicrobial therapy and the time of data collection.

Management of DAIR procedures at the MVAHCS involves evaluating the fixation of the prosthesis, tissue sampling for microbiological analysis, and thorough debridement of infected tissue. Following debridement, a course of IV antibiotics is administered before initiating oral antibiotic therapy. To protect against resistance, rifampin is combined with another antibiotic typically from the fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, or cephalosporin class. Current guidelines suggest 3 and 6 months of oral antibiotics for prosthetic hip and knee infections, respectively.6

Treatment Outcomes

The primary outcome was treatment success, defined as meeting all of the following: (1) lack of clinical signs and symptoms of infection; (2) absence of radiological signs of loosening or infection within 1 year after the conclusion of treatment; and (3) absence of additional PJI treatment interventions for the prosthesis of concern within 1 year after completing the original antibiotic treatment.

Treatment failure was defined as meeting any of the following: (1) recurrence of PJI (original strain or different microorganism) within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; (2) death attributed to PJI anytime after the initial debridement; (3) removal of the prosthetic joint within 1 year after the completion of antibiotic therapy; or (4) long-term antibiotic use to suppress the PJI after the completion of the initial antibiotic therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to define the baseline characteristics of patients receiving rifampin therapy for orthopedic implant infections at the MVAHCS. Variables analyzed were age, sex, race and ethnicity, type of implant, age of implant, duration of symptoms, comorbidities (diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis), and presence of chronic infection. Patients were classified as having a chronic infection if they received previous infection treatment (antibiotics or surgery) for the orthopedic device in question. We created this category because patients with persistent infection after a medical or surgical attempt at treatment are likely to have a higher probability of treatment failure compared with those with no prior therapy. Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated using clinical information present at the onset of infection.9 Fisher exact test was used to assess differences between categorical variables, and an independent t test was used to assess differences in continuous variables. P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

To assess the ability of a rifampin-based regimen to achieve a cure of PJI, we grouped participants into 2 categories: those with an intent to cure strategy and those without intent to cure based on documentation in the electronic health record (EHR). Participants who were prescribed rifampin with the documented goal of prosthesis retention with no further suppressive antibiotics were included in the intent-to-cure group, the primary focus of this study. Those excluded from the intent-to-cure group were given rifampin and another antibiotic, but there was a documented plan of either ongoing chronic suppression or eventual explantation; these participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Analysis of treatment success and failure was limited to the intent-to-cure group, whereas both groups were included for assessment of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment duration. This project was reviewed by the MVAHCS Institutional Review Board and determined to be a quality improvement initiative and to not meet the definition of research, and as such did not require review; it was reviewed and approved by the MVAHCS Research and Development Committee.

RESULTS

A total of 538 patients were identified who simultaneously received rifampin and another oral antibiotic between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2021.

Forty-two participants (54%) had Staphylococcus aureus and 31 participants (40%) had coagulase-negative staphylococci infections, while 11 gram-negative organisms (14%) and 6 gram-positive anaerobic cocci (8%) infections were noted. Cutibacterium acnes and Streptococcus agalactiae were each found in 3 participants (4% of), and diphtheroids (not further identified) was found on 2 participants (3%). Candida albicans was identified in a single participant (1%), along with coagulase-negative staphylococci, and 2 participants (3%) had no identified organisms. There were multiple organisms isolated from 20 patients (26%).

Fifty participants had clear documentation in their EHR that cure of infection was the goal, meeting the criteria for the intent-to-cure group. The remaining 28 participants were placed in the without-intent-to-cure group. Success and failure rates were only measured in the intent-to-cure group, as by definition the without-intent-to-cure group patients would meet the criteria for failure (removal of prosthesis or long-term antibiotic use). The without-intent-to-cure group had a higher median age than the intent-to-cure group (69 years vs 64 years, P = .24) and a higher proportion of male participants (96% vs 80%, P = .09). The median (IQR) implant age of 11 months (1.0-50.5) in the without-intent-to-cure group was also higher than the median implant age of 1 month (0.6-22.0) in the primary group (P = .22). In the without-intent-to-cure group, 19 participants (68%) had a chronic infection, compared with 11 (22%) in the intent-to-cure group (P < .001).

The mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index in the without-intent-to-cure group was 2.5 (1.3) compared with 1.9 (1.4) in the intent-to-cure group (P = .09). There was no significant difference in the type of implant or microbiology of the infecting organism between the 2 groups, although it should be noted that in the intent-to-cure group, 48 patients (96%) had Staphylococcus aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated.

The median (IQR) dosage of rifampin was 600 mg (300-900). The secondary oral antibiotics used most often were 36 fluoroquinolones (46%) followed by 20 tetracyclines (26%), 6 cephalosporins (8%), and 6 penicillins (8%). Additionally, 6 participants (8%) received IV vancomycin, and 1 participant (1%) was given an oral antifungal in addition to a fluoroquinolone because cultures revealed bacterial and fungal growth. The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3 months (1.4-3.0). The mean (SD) duration of antimicrobial therapy was 3.6 (2.4) months for TKA infections and 2.4 (0.9) months for THA infections.

Clinical Outcome

Forty-one intent-to-cure group participants (82%) experienced treatment success. We further subdivided the intent-to-cure group by implant age. Participants whose implant was < 2 months old had a success rate of 93%, whereas patients whose implant was older had a success rate of 65% (P = .02).

Secondary Outcomes

The median (IQR) duration of antimicrobial treatment was 3 months (1.4-3.0) for the 38 patients with TKA-related infections and 3 months (1.4-6.0) for the 29 patients with THA infections. AEs were recorded in 24 (31%) of all study participants. Of those with AEs, the average number reported per patient was 1.6. Diarrhea, gastric upset, and nausea were each reported 7 times, accounting for 87% of all recorded AEs. Five participants reported having a rash while on antibiotics, and 2 experienced dysgeusia. One participant reported developing a yeast infection and another experienced vaginitis.

DISCUSSION

Among patients with orthopedic implant infections treated with intent to cure using a rifampin-containing antibiotic regimen at the MVAHCS, 82% had clinical success. Although this is lower than the success rates reported in clinical trials, this is not entirely unexpected.5,7 In most clinical trials studying DAIR and rifampin for PJI, patients are excluded if they do not have an acute staphylococcal infection in the setting of a well-fixed prosthesis without evidence of a sinus tract. Such exclusion criteria were not present in our retrospective study, which was designed to evaluate the real-world practice patterns at this facility. The population at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is older, more frail, and with more comorbid conditions than populations in prior studies. It is possible that patients with characteristics that would have caused them to be excluded from a clinical trial would be less likely to receive rifampin therapy with the intent to cure. This is suggested by the significantly higher prevalence of chronic infections (68%) in the without-intent-to-cure group compared with 22% in the intent-to-cure group. However, there were reasonably high proportions of participants included in the intent-to-cure group who did have conditions that would have led to their exclusion from prior trials, such as chronic infection (22%) and implant age ≥ 2 months (40%).

When evaluating participants by the age of their implant, treatment success rose to 93% for patients with implants < 2 months old compared with 65% for patients with older implants. This suggests that participants with a newer implant or more recent infection have a greater likelihood of successful treatment, which is consistent with the results of previous clinical trials.5,10 Considering how difficult multiple surgeries can be for older adult patients with comorbidities, we suggest that DAIR with a rifampin-containing regimen be considered as the primary treatment option for early PJIs at the MVAHCS. We also note inconsistent adherence to IDSA treatment guidelines on rifampin therapy, in that patients without intent to cure were prescribed a regimen including rifampin. This may reflect appropriate variability in the care of individual patients but may also offer an opportunity to change processes to improve care.

Limitations

Our analysis has limitations. As with any retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of a specific antibiotic, we were not able to attribute specific outcomes to the antibiotic of interest. Since the choice of antibiotics was left to the treating health care practitioner, therapy was not standardized, and because this was a retrospective study, causal relationships could not be inferred. Our analysis was also limited by the lack of intent to cure in 28 participants (36%), which could be an indication of practitioner bias in therapy selection or characteristic differences between the 2 groups. We looked for signs of infection failure 1 year after the completion of antimicrobial therapy, but longer follow-up could have led to higher rates of failure. Also, while participants’ infections were considered cured if they never sought further medical care for the infection at the MVAHCS, it is possible that patients could have sought care at another facility. We note that 9 patients were excluded because they were unable to complete a treatment course due to rifampin AEs, meaning that the success rates reported here reflect the success that may be expected if a patient can tolerate and complete a rifampin-based regimen. This study was conducted in a single VA hospital and may not be generalizable to nonveterans or veterans seeking care at other facilities.

Conclusions

DAIR followed by a short course of IV antibiotics and an oral regimen including rifampin and another antimicrobial is a reasonable option for veterans with acute staphylococcal orthopedic device infections at the MVAHCS. Patients with a well-placed prosthesis and an acute infection seem especially well suited for this treatment, and treatment with intent to cure should be pursued in patients who meet the criteria for rifampin therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Stensgard, PharmD, for assistance in compiling the list of patients receiving rifampin and another antimicrobial.

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

2. Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):386-394. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61798-0

3. Zhan C, Kaczmarek R, Loyo-Berrios N, Sangl J, Bright RA. Incidence and short-term outcomes of primary and revision hip replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):526-533. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00952

4. Fisman DN, Reilly DT, Karchmer AW, Goldie SJ. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 management strategies for infected total hip arthroplasty in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):419-430. doi:10.1086/318502

5. Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1537-1541. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1537

6. Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):e1-e25. doi:10.1093/cid/cis803

7. Lora-Tamayo J, Euba G, Cobo J, et al. Short- versus long-duration levofloxacin plus rifampicin for acute staphylococcal prosthetic joint infection managed with implant retention: a randomised clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):310-316. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.021

8. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

9. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

10. Vilchez F, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, et al. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in early post-surgical prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus treated with debridement. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):439-444. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03244.x

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

2. Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):386-394. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61798-0

3. Zhan C, Kaczmarek R, Loyo-Berrios N, Sangl J, Bright RA. Incidence and short-term outcomes of primary and revision hip replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):526-533. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00952

4. Fisman DN, Reilly DT, Karchmer AW, Goldie SJ. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 management strategies for infected total hip arthroplasty in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):419-430. doi:10.1086/318502

5. Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1537-1541. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1537

6. Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):e1-e25. doi:10.1093/cid/cis803

7. Lora-Tamayo J, Euba G, Cobo J, et al. Short- versus long-duration levofloxacin plus rifampicin for acute staphylococcal prosthetic joint infection managed with implant retention: a randomised clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):310-316. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.021

8. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

9. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

10. Vilchez F, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, et al. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in early post-surgical prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus treated with debridement. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):439-444. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03244.x

‘Decapitated’ boy saved by surgery team

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

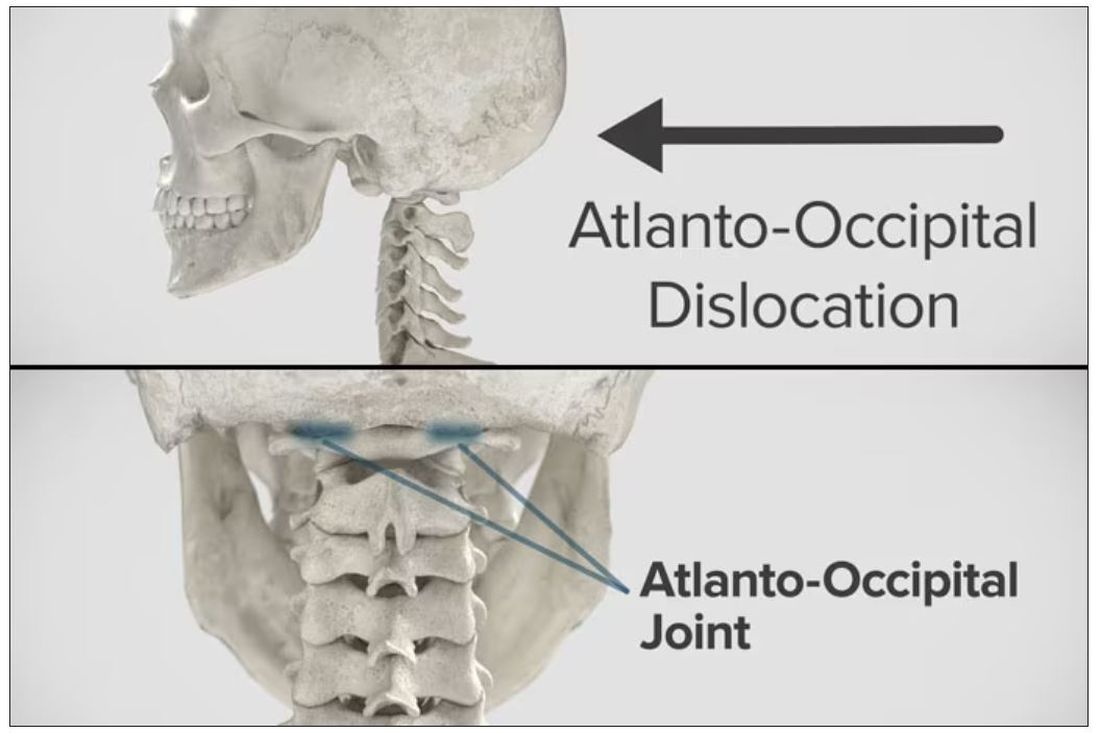

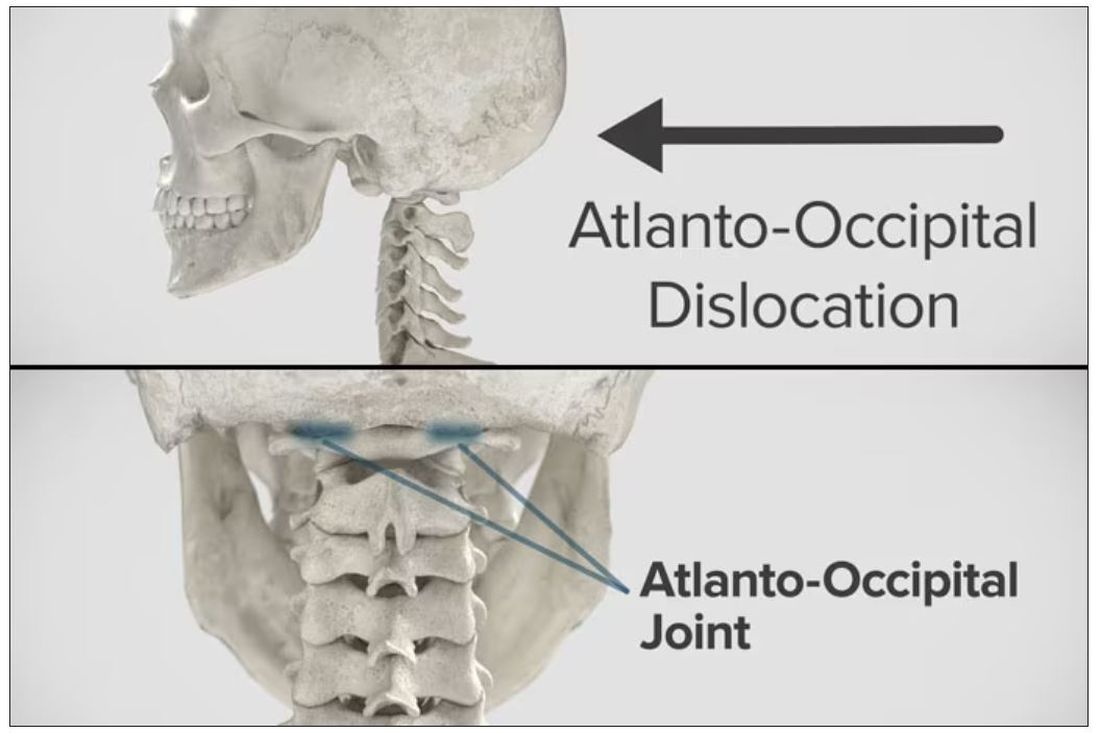

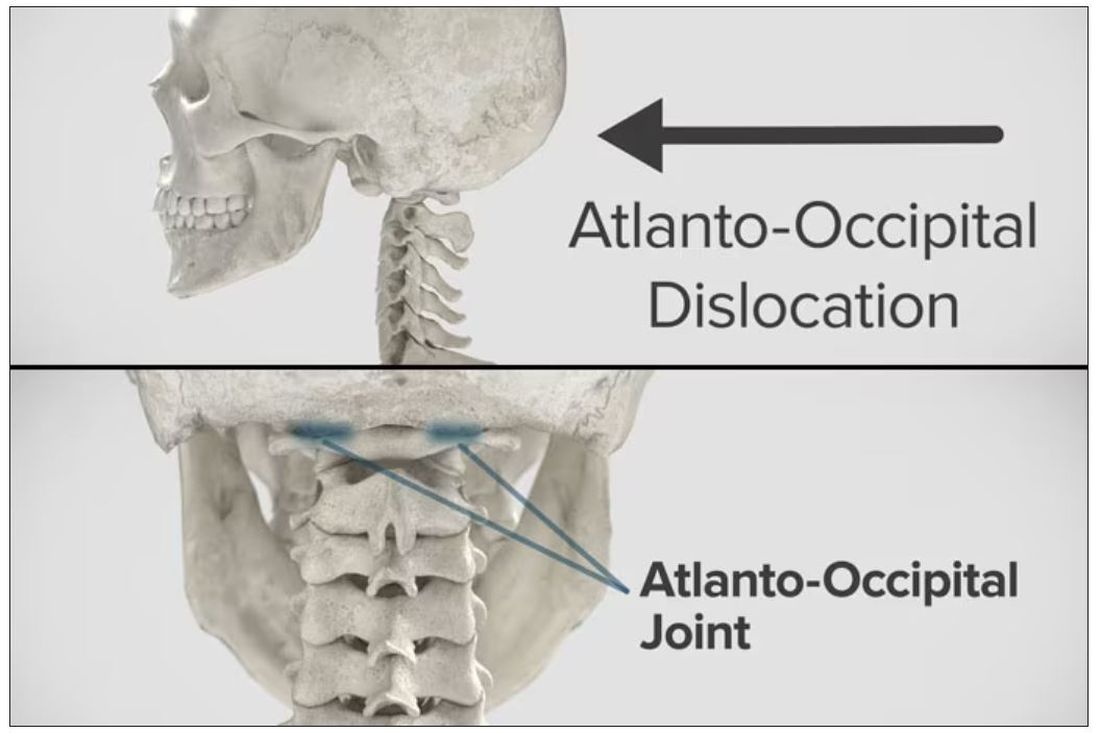

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?