User login

‘Where does it hurt?’: Primary care tips for common ortho problems

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

Wearable sensors deemed reliable for home gait assessment in knee OA

Remote gait assessment in people with knee osteoarthritis using wearable sensors appears reliable but yields results slightly different from those achieved in the laboratory, researchers from Boston University have found.

As reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress, there was “good to excellent reliability” in repeated measures collected by patients at home while being instructed via video teleconferencing.

Agreement was “moderate to excellent” when the findings were compared with those recorded in the lab, Michael J. Rose of Boston University reported at the congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“People walked faster and stood up faster in the lab,” Mr. Rose said. “Later we found that the difference in gait speed was statistically significant between the lab and home environment.”

This has been suggested previously and implies that data collected at home may have “greater ecological validity,” he observed.

Accelerated adoption of telehealth

Assessing how well someone walks or can stand from a seated position are well known and important assessments in knee OA, but these have but have traditionally only been done in large and expensive gait labs, Mr. Rose said.

Wearable technologies, such as the ones used in the study he presented, could help move these assessments out into the community. This is particularly timely considering the increased adoption of telehealth practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To look at the reliability measurements obtained via wearable sensors versus lab assessments, Mr. Rose and associates set up a substudy within a larger ongoing, single-arm trial looking at the use of digital assessments to measure the efficacy of an exercise intervention in reducing knee pain and improving knee function.

For inclusion in the main trial (n = 60), and hence the substudy (n = 20), participants had to have physician-diagnosed knee OA, be 50 years of age or older, have a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or lower, be able to walk at for a least 20 minutes, and have a score of three or higher on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score pain subscale for weight-bearing items.

Acceptance of in-lab versus home testing

The substudy participants (mean age, 70.5 years) all underwent in-person lab visits in which a wearable sensor was placed on each foot and one around the lower back and the participant asked to perform walking and chair stand tests. The latter involved standing from a seated position as quickly as possible without using the arms five times, while the former involved walking 28 meters in two laps of a 7-meter path defined by two cones. These tests were repeated twice.

Participants were then given the equipment to repeat these tests at home; this included the three sensors, a tablet computer, and chair and cones. The home assessments were conducted via video conferencing, with the researchers reminding how to place the sensors correctly. The walking and chair stand tests were then each performed four times: Twice in a row and then a 15-minute rest period before being performed twice in a row again.

The researchers collected participants’ feedback about the process on questionnaires and Likert scales that showed an overall positive experience for the remote home visit, with the median rating being “very likely” to participate in another home visit and that the time commitment required was “very manageable.”

Good correlation found

To determine the correlation and the test-retest reliability of the data obtained during the repeated home tasks, Mr. Rose and collaborators used Pearson’s correlation R2 and the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC).

ICCs for various gait and chair stand variables obtained with the sensors were between 0.85 and 0.96 for the test-retest reliability during the remote home visit, and R2 ranged between 0.81 and 0.95. Variables include stance, cadence (steps per minute), step duration and length, speed, and chair stand duration.

With regard to the agreement between the home versus lab results, ICCs ranged between 0.63 and 0.9.

“There were some logistical and technological challenges with the approach,” Mr. Rose conceded. “Despite written and verbal instructions, 2 of the 20 participants ended up having gait data that was unusable in the home visit.”

Another limitation is that the study population, while “representative,” contained a higher number of individuals than the general population who identified as being White (95%) and female (85%), and 90% had a college degree.

“Individuals typically representative of an OA population were generally accepting and willing to participate in remote visits showing the feasibility of our approach,” Mr. Rose said.

“We need to determine the responsiveness of gait and chair stand outcomes from wearable sensors at home to change over time.”

The study was sponsored by Boston University with funding from Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The researchers used the OPAL inertial sensor (APDM Wearable Technologies) in the study. Mr. Rose made no personal disclosures. Four of his collaborators were employees of Pfizer and one is an employee of Eli Lilly & Company, all with stock or stock options.

Remote gait assessment in people with knee osteoarthritis using wearable sensors appears reliable but yields results slightly different from those achieved in the laboratory, researchers from Boston University have found.

As reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress, there was “good to excellent reliability” in repeated measures collected by patients at home while being instructed via video teleconferencing.

Agreement was “moderate to excellent” when the findings were compared with those recorded in the lab, Michael J. Rose of Boston University reported at the congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“People walked faster and stood up faster in the lab,” Mr. Rose said. “Later we found that the difference in gait speed was statistically significant between the lab and home environment.”

This has been suggested previously and implies that data collected at home may have “greater ecological validity,” he observed.

Accelerated adoption of telehealth

Assessing how well someone walks or can stand from a seated position are well known and important assessments in knee OA, but these have but have traditionally only been done in large and expensive gait labs, Mr. Rose said.

Wearable technologies, such as the ones used in the study he presented, could help move these assessments out into the community. This is particularly timely considering the increased adoption of telehealth practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To look at the reliability measurements obtained via wearable sensors versus lab assessments, Mr. Rose and associates set up a substudy within a larger ongoing, single-arm trial looking at the use of digital assessments to measure the efficacy of an exercise intervention in reducing knee pain and improving knee function.

For inclusion in the main trial (n = 60), and hence the substudy (n = 20), participants had to have physician-diagnosed knee OA, be 50 years of age or older, have a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or lower, be able to walk at for a least 20 minutes, and have a score of three or higher on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score pain subscale for weight-bearing items.

Acceptance of in-lab versus home testing

The substudy participants (mean age, 70.5 years) all underwent in-person lab visits in which a wearable sensor was placed on each foot and one around the lower back and the participant asked to perform walking and chair stand tests. The latter involved standing from a seated position as quickly as possible without using the arms five times, while the former involved walking 28 meters in two laps of a 7-meter path defined by two cones. These tests were repeated twice.

Participants were then given the equipment to repeat these tests at home; this included the three sensors, a tablet computer, and chair and cones. The home assessments were conducted via video conferencing, with the researchers reminding how to place the sensors correctly. The walking and chair stand tests were then each performed four times: Twice in a row and then a 15-minute rest period before being performed twice in a row again.

The researchers collected participants’ feedback about the process on questionnaires and Likert scales that showed an overall positive experience for the remote home visit, with the median rating being “very likely” to participate in another home visit and that the time commitment required was “very manageable.”

Good correlation found

To determine the correlation and the test-retest reliability of the data obtained during the repeated home tasks, Mr. Rose and collaborators used Pearson’s correlation R2 and the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC).

ICCs for various gait and chair stand variables obtained with the sensors were between 0.85 and 0.96 for the test-retest reliability during the remote home visit, and R2 ranged between 0.81 and 0.95. Variables include stance, cadence (steps per minute), step duration and length, speed, and chair stand duration.

With regard to the agreement between the home versus lab results, ICCs ranged between 0.63 and 0.9.

“There were some logistical and technological challenges with the approach,” Mr. Rose conceded. “Despite written and verbal instructions, 2 of the 20 participants ended up having gait data that was unusable in the home visit.”

Another limitation is that the study population, while “representative,” contained a higher number of individuals than the general population who identified as being White (95%) and female (85%), and 90% had a college degree.

“Individuals typically representative of an OA population were generally accepting and willing to participate in remote visits showing the feasibility of our approach,” Mr. Rose said.

“We need to determine the responsiveness of gait and chair stand outcomes from wearable sensors at home to change over time.”

The study was sponsored by Boston University with funding from Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The researchers used the OPAL inertial sensor (APDM Wearable Technologies) in the study. Mr. Rose made no personal disclosures. Four of his collaborators were employees of Pfizer and one is an employee of Eli Lilly & Company, all with stock or stock options.

Remote gait assessment in people with knee osteoarthritis using wearable sensors appears reliable but yields results slightly different from those achieved in the laboratory, researchers from Boston University have found.

As reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress, there was “good to excellent reliability” in repeated measures collected by patients at home while being instructed via video teleconferencing.

Agreement was “moderate to excellent” when the findings were compared with those recorded in the lab, Michael J. Rose of Boston University reported at the congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“People walked faster and stood up faster in the lab,” Mr. Rose said. “Later we found that the difference in gait speed was statistically significant between the lab and home environment.”

This has been suggested previously and implies that data collected at home may have “greater ecological validity,” he observed.

Accelerated adoption of telehealth

Assessing how well someone walks or can stand from a seated position are well known and important assessments in knee OA, but these have but have traditionally only been done in large and expensive gait labs, Mr. Rose said.

Wearable technologies, such as the ones used in the study he presented, could help move these assessments out into the community. This is particularly timely considering the increased adoption of telehealth practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To look at the reliability measurements obtained via wearable sensors versus lab assessments, Mr. Rose and associates set up a substudy within a larger ongoing, single-arm trial looking at the use of digital assessments to measure the efficacy of an exercise intervention in reducing knee pain and improving knee function.

For inclusion in the main trial (n = 60), and hence the substudy (n = 20), participants had to have physician-diagnosed knee OA, be 50 years of age or older, have a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or lower, be able to walk at for a least 20 minutes, and have a score of three or higher on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score pain subscale for weight-bearing items.

Acceptance of in-lab versus home testing

The substudy participants (mean age, 70.5 years) all underwent in-person lab visits in which a wearable sensor was placed on each foot and one around the lower back and the participant asked to perform walking and chair stand tests. The latter involved standing from a seated position as quickly as possible without using the arms five times, while the former involved walking 28 meters in two laps of a 7-meter path defined by two cones. These tests were repeated twice.

Participants were then given the equipment to repeat these tests at home; this included the three sensors, a tablet computer, and chair and cones. The home assessments were conducted via video conferencing, with the researchers reminding how to place the sensors correctly. The walking and chair stand tests were then each performed four times: Twice in a row and then a 15-minute rest period before being performed twice in a row again.

The researchers collected participants’ feedback about the process on questionnaires and Likert scales that showed an overall positive experience for the remote home visit, with the median rating being “very likely” to participate in another home visit and that the time commitment required was “very manageable.”

Good correlation found

To determine the correlation and the test-retest reliability of the data obtained during the repeated home tasks, Mr. Rose and collaborators used Pearson’s correlation R2 and the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC).

ICCs for various gait and chair stand variables obtained with the sensors were between 0.85 and 0.96 for the test-retest reliability during the remote home visit, and R2 ranged between 0.81 and 0.95. Variables include stance, cadence (steps per minute), step duration and length, speed, and chair stand duration.

With regard to the agreement between the home versus lab results, ICCs ranged between 0.63 and 0.9.

“There were some logistical and technological challenges with the approach,” Mr. Rose conceded. “Despite written and verbal instructions, 2 of the 20 participants ended up having gait data that was unusable in the home visit.”

Another limitation is that the study population, while “representative,” contained a higher number of individuals than the general population who identified as being White (95%) and female (85%), and 90% had a college degree.

“Individuals typically representative of an OA population were generally accepting and willing to participate in remote visits showing the feasibility of our approach,” Mr. Rose said.

“We need to determine the responsiveness of gait and chair stand outcomes from wearable sensors at home to change over time.”

The study was sponsored by Boston University with funding from Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The researchers used the OPAL inertial sensor (APDM Wearable Technologies) in the study. Mr. Rose made no personal disclosures. Four of his collaborators were employees of Pfizer and one is an employee of Eli Lilly & Company, all with stock or stock options.

FROM OARSI 2022

Inadequate pain relief in OA, high opioid use before TKA

Inadequate pain relief was recorded in 68.8% of a sample of people with hip or knee OA who participated in the population-based EpiReumaPt study, researchers reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

“This can be explained by a lack of effectiveness of current management strategies, low uptake of recommended interventions by health care professionals, and also by low adherence by patients to medication and lifestyle interventions,” said Daniela Sofia Albino Costa, MSc, a PhD student at NOVA University Lisbon.

In addition to looking at the prevalence of inadequate pain relief – defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) – the study she presented at the congress, which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International, looked at the predictors for inadequate pain control.

It was found that being female, obesity, and having multimorbidity doubled the risk of inadequate versus adequate pain control, with respective odds ratios of 2.32 (P < .001), 2.26 (P = .006), and 2.07 (P = .001). Overweight was also associated with an increased odds ratio for poor pain control (OR, 1.84; P = .0035).

“We found that patients with inadequate pain relief also have a low performance on activities of daily living and a low quality of life,” Ms. Costa said.

Nearly one-third (29%) of patients in the inadequate pain relief group (n = 765) took medication, versus 15% of patients in the adequate pain relief group (n = 270). This was mostly NSAIDs, but also included analgesics and antipyretics, and in a few cases (4.8% vs. 1.3%), simple opioids.

“We know that current care is not concordant with recommendations,” said Ms. Costa, noting that medication being used as first-line treatment and core nonpharmacologic interventions are being offered to less than half of patients who are eligible.

In addition, the rate for total joint replacement has increased globally, and pain is an important predictor for this.

“So, we need to evaluate pain control and current management offered to people with hip or knee arthritis to identify to identify areas for improvement,” Ms. Costa said.

High rates of prescription opioid use before TKA

In a separate study also presented at the congress, Daniel Rhon, DPT, DSc, director of musculoskeletal research in primary care at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, gave a worrying glimpse of high rates of opioid use in the 4 years before total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Using data from the U.S. Military Health System, the records of all individuals who had a knee replacement procedure between January 2017 and December 2018 were studied, to identify and characterize the use of prescription opioids.

Of the 46,362 individuals, 52.9% had prior opioid use, despite the fact that “opioids are not recommended for the management of knee OA,” said Dr. Rhon.

He also reported that as many as 40% of those who had at least one prescription for opioids had received a high-potency drug, such as fentanyl or oxycodone. The mean age of participants overall was 65 years, with a higher mean for those receiving opioids than those who did not (68 vs. 61.5 years). Data on sex and ethnicity were not available in time for presentation at the congress.

“Most of these individuals are getting these opioid prescriptions probably within 6 months, which maybe aligns with escalation of pain and maybe the decision to have that knee replacement,” Dr. Rhon said. Individuals that used opioids filled their most recent prescription a median of 146 days before TKA to surgery, with a mean of 317 days.

“You can’t always link the reason for the opioid prescription, that’s not really clear in the database,” he admitted; however, an analysis was performed to check if other surgeries had been performed that may have warranted the opioid treatment. The results revealed that very few of the opioid users (4%-7%) had undergone another type of surgical procedure.

“So, we feel a little bit better, that these findings weren’t for other surgical procedures,” said Dr. Rhon. He added that future qualitative research was needed to understand why health care professionals were prescribing opioids, and why patients felt like they needed them.

“That’s bad,” Haxby Abbott, PhD, DPT, a research professor at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, commented on Twitter.

Dr. Abbott, who was not involved in the study, added: “We’ve done a similar study of the whole NZ population [currently under review] – similar to Australia and not nearly as bad as you found. That needs urgent attention.”

Sharp rise in opioid use 2 years before TKA

Lower rates of opioid use before TKA were seen in two European cohorts, at 43% in England and 33% in Sweden, as reported by Clara Hellberg, PhD, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University. However, rates had increased over a 10-year study period from a respective 23% and 16%, with a sharp increase in use in the 2 years before knee replacement.

The analysis was based on 49,043 patients from the English national database Clinical Practice Research Datalink, and 5,955 patients from the Swedish Skåne Healthcare register who had undergone total knee replacement between 2015 and 2019 and were matched by age, sex and general practice to individuals not undergoing knee replacement.

The prevalence ratio for using opioids over a 10-year period increased from 1.6 to 2.7 in England, and from 1.6 to 2.6 in Sweden.

“While the overall prevalence of opioid use was higher in England, the majority of both cases and controls were using weak opioids,” Dr. Hellberg said.

“Codeine was classified as a weak opioid, whereas morphine was classified as a strong opioid,” she added.

In contrast, the proportion of people using strong opioids in Sweden was greater than in England, she said.

The high opioid use found in the study highlights “the need for better opioid stewardship, and the availability of acceptable, effective alternatives,” Dr. Hellberg and associates concluded in their abstract.

The study presented by Ms. Costa was funded by the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology and by an independent research grant from Pfizer. Dr. Rhon acknowledged grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defense. Dr. Hellberg had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Inadequate pain relief was recorded in 68.8% of a sample of people with hip or knee OA who participated in the population-based EpiReumaPt study, researchers reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

“This can be explained by a lack of effectiveness of current management strategies, low uptake of recommended interventions by health care professionals, and also by low adherence by patients to medication and lifestyle interventions,” said Daniela Sofia Albino Costa, MSc, a PhD student at NOVA University Lisbon.

In addition to looking at the prevalence of inadequate pain relief – defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) – the study she presented at the congress, which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International, looked at the predictors for inadequate pain control.

It was found that being female, obesity, and having multimorbidity doubled the risk of inadequate versus adequate pain control, with respective odds ratios of 2.32 (P < .001), 2.26 (P = .006), and 2.07 (P = .001). Overweight was also associated with an increased odds ratio for poor pain control (OR, 1.84; P = .0035).

“We found that patients with inadequate pain relief also have a low performance on activities of daily living and a low quality of life,” Ms. Costa said.

Nearly one-third (29%) of patients in the inadequate pain relief group (n = 765) took medication, versus 15% of patients in the adequate pain relief group (n = 270). This was mostly NSAIDs, but also included analgesics and antipyretics, and in a few cases (4.8% vs. 1.3%), simple opioids.

“We know that current care is not concordant with recommendations,” said Ms. Costa, noting that medication being used as first-line treatment and core nonpharmacologic interventions are being offered to less than half of patients who are eligible.

In addition, the rate for total joint replacement has increased globally, and pain is an important predictor for this.

“So, we need to evaluate pain control and current management offered to people with hip or knee arthritis to identify to identify areas for improvement,” Ms. Costa said.

High rates of prescription opioid use before TKA

In a separate study also presented at the congress, Daniel Rhon, DPT, DSc, director of musculoskeletal research in primary care at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, gave a worrying glimpse of high rates of opioid use in the 4 years before total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Using data from the U.S. Military Health System, the records of all individuals who had a knee replacement procedure between January 2017 and December 2018 were studied, to identify and characterize the use of prescription opioids.

Of the 46,362 individuals, 52.9% had prior opioid use, despite the fact that “opioids are not recommended for the management of knee OA,” said Dr. Rhon.

He also reported that as many as 40% of those who had at least one prescription for opioids had received a high-potency drug, such as fentanyl or oxycodone. The mean age of participants overall was 65 years, with a higher mean for those receiving opioids than those who did not (68 vs. 61.5 years). Data on sex and ethnicity were not available in time for presentation at the congress.

“Most of these individuals are getting these opioid prescriptions probably within 6 months, which maybe aligns with escalation of pain and maybe the decision to have that knee replacement,” Dr. Rhon said. Individuals that used opioids filled their most recent prescription a median of 146 days before TKA to surgery, with a mean of 317 days.

“You can’t always link the reason for the opioid prescription, that’s not really clear in the database,” he admitted; however, an analysis was performed to check if other surgeries had been performed that may have warranted the opioid treatment. The results revealed that very few of the opioid users (4%-7%) had undergone another type of surgical procedure.

“So, we feel a little bit better, that these findings weren’t for other surgical procedures,” said Dr. Rhon. He added that future qualitative research was needed to understand why health care professionals were prescribing opioids, and why patients felt like they needed them.

“That’s bad,” Haxby Abbott, PhD, DPT, a research professor at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, commented on Twitter.

Dr. Abbott, who was not involved in the study, added: “We’ve done a similar study of the whole NZ population [currently under review] – similar to Australia and not nearly as bad as you found. That needs urgent attention.”

Sharp rise in opioid use 2 years before TKA

Lower rates of opioid use before TKA were seen in two European cohorts, at 43% in England and 33% in Sweden, as reported by Clara Hellberg, PhD, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University. However, rates had increased over a 10-year study period from a respective 23% and 16%, with a sharp increase in use in the 2 years before knee replacement.

The analysis was based on 49,043 patients from the English national database Clinical Practice Research Datalink, and 5,955 patients from the Swedish Skåne Healthcare register who had undergone total knee replacement between 2015 and 2019 and were matched by age, sex and general practice to individuals not undergoing knee replacement.

The prevalence ratio for using opioids over a 10-year period increased from 1.6 to 2.7 in England, and from 1.6 to 2.6 in Sweden.

“While the overall prevalence of opioid use was higher in England, the majority of both cases and controls were using weak opioids,” Dr. Hellberg said.

“Codeine was classified as a weak opioid, whereas morphine was classified as a strong opioid,” she added.

In contrast, the proportion of people using strong opioids in Sweden was greater than in England, she said.

The high opioid use found in the study highlights “the need for better opioid stewardship, and the availability of acceptable, effective alternatives,” Dr. Hellberg and associates concluded in their abstract.

The study presented by Ms. Costa was funded by the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology and by an independent research grant from Pfizer. Dr. Rhon acknowledged grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defense. Dr. Hellberg had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Inadequate pain relief was recorded in 68.8% of a sample of people with hip or knee OA who participated in the population-based EpiReumaPt study, researchers reported at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

“This can be explained by a lack of effectiveness of current management strategies, low uptake of recommended interventions by health care professionals, and also by low adherence by patients to medication and lifestyle interventions,” said Daniela Sofia Albino Costa, MSc, a PhD student at NOVA University Lisbon.

In addition to looking at the prevalence of inadequate pain relief – defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) – the study she presented at the congress, which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International, looked at the predictors for inadequate pain control.

It was found that being female, obesity, and having multimorbidity doubled the risk of inadequate versus adequate pain control, with respective odds ratios of 2.32 (P < .001), 2.26 (P = .006), and 2.07 (P = .001). Overweight was also associated with an increased odds ratio for poor pain control (OR, 1.84; P = .0035).

“We found that patients with inadequate pain relief also have a low performance on activities of daily living and a low quality of life,” Ms. Costa said.

Nearly one-third (29%) of patients in the inadequate pain relief group (n = 765) took medication, versus 15% of patients in the adequate pain relief group (n = 270). This was mostly NSAIDs, but also included analgesics and antipyretics, and in a few cases (4.8% vs. 1.3%), simple opioids.

“We know that current care is not concordant with recommendations,” said Ms. Costa, noting that medication being used as first-line treatment and core nonpharmacologic interventions are being offered to less than half of patients who are eligible.

In addition, the rate for total joint replacement has increased globally, and pain is an important predictor for this.

“So, we need to evaluate pain control and current management offered to people with hip or knee arthritis to identify to identify areas for improvement,” Ms. Costa said.

High rates of prescription opioid use before TKA

In a separate study also presented at the congress, Daniel Rhon, DPT, DSc, director of musculoskeletal research in primary care at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, gave a worrying glimpse of high rates of opioid use in the 4 years before total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Using data from the U.S. Military Health System, the records of all individuals who had a knee replacement procedure between January 2017 and December 2018 were studied, to identify and characterize the use of prescription opioids.

Of the 46,362 individuals, 52.9% had prior opioid use, despite the fact that “opioids are not recommended for the management of knee OA,” said Dr. Rhon.

He also reported that as many as 40% of those who had at least one prescription for opioids had received a high-potency drug, such as fentanyl or oxycodone. The mean age of participants overall was 65 years, with a higher mean for those receiving opioids than those who did not (68 vs. 61.5 years). Data on sex and ethnicity were not available in time for presentation at the congress.

“Most of these individuals are getting these opioid prescriptions probably within 6 months, which maybe aligns with escalation of pain and maybe the decision to have that knee replacement,” Dr. Rhon said. Individuals that used opioids filled their most recent prescription a median of 146 days before TKA to surgery, with a mean of 317 days.

“You can’t always link the reason for the opioid prescription, that’s not really clear in the database,” he admitted; however, an analysis was performed to check if other surgeries had been performed that may have warranted the opioid treatment. The results revealed that very few of the opioid users (4%-7%) had undergone another type of surgical procedure.

“So, we feel a little bit better, that these findings weren’t for other surgical procedures,” said Dr. Rhon. He added that future qualitative research was needed to understand why health care professionals were prescribing opioids, and why patients felt like they needed them.

“That’s bad,” Haxby Abbott, PhD, DPT, a research professor at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, commented on Twitter.

Dr. Abbott, who was not involved in the study, added: “We’ve done a similar study of the whole NZ population [currently under review] – similar to Australia and not nearly as bad as you found. That needs urgent attention.”

Sharp rise in opioid use 2 years before TKA

Lower rates of opioid use before TKA were seen in two European cohorts, at 43% in England and 33% in Sweden, as reported by Clara Hellberg, PhD, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University. However, rates had increased over a 10-year study period from a respective 23% and 16%, with a sharp increase in use in the 2 years before knee replacement.

The analysis was based on 49,043 patients from the English national database Clinical Practice Research Datalink, and 5,955 patients from the Swedish Skåne Healthcare register who had undergone total knee replacement between 2015 and 2019 and were matched by age, sex and general practice to individuals not undergoing knee replacement.

The prevalence ratio for using opioids over a 10-year period increased from 1.6 to 2.7 in England, and from 1.6 to 2.6 in Sweden.

“While the overall prevalence of opioid use was higher in England, the majority of both cases and controls were using weak opioids,” Dr. Hellberg said.

“Codeine was classified as a weak opioid, whereas morphine was classified as a strong opioid,” she added.

In contrast, the proportion of people using strong opioids in Sweden was greater than in England, she said.

The high opioid use found in the study highlights “the need for better opioid stewardship, and the availability of acceptable, effective alternatives,” Dr. Hellberg and associates concluded in their abstract.

The study presented by Ms. Costa was funded by the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology and by an independent research grant from Pfizer. Dr. Rhon acknowledged grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defense. Dr. Hellberg had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM OARSI 2022

Early meniscal surgery on par with active rehab in under 40s

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM OARSI 2022

Elective Total Hip Arthroplasty: Which Surgical Approach Is Optimal?

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful orthopedic interventions performed today in terms of pain relief, cost effectiveness, and clinical outcomes.1 As a definitive treatment for end-stage arthritis of the hip, more than 330,000 procedures are performed in the Unites States each year. The number performed is growing by > 5% per year and is predicted to double by 2030, partly due to patients living longer, older individuals seeking a higher level of functionality than did previous generations, and better access to health care.2,3

The THA procedure also has become increasingly common in a younger population for posttraumatic fractures and conditions that lead to early-onset secondary arthritis, such as avascular necrosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, hip dysplasia, Perthes disease, and femoroacetabular impingement.4 Younger patients are more likely to need a revision. According to a study by Evans and colleagues using available arthroplasty registry data, about three-quarters of hip replacements last 15 to 20 years, and 58% of hip replacements last 25 years in patients with osteoarthritis.5

For decades, the THA procedure of choice has been a standard posterior approach (PA). The PA was used because it allowed excellent intraoperative exposure and was applicable to a wide range of hip problems.6 In the past several years, modified muscle-sparing surgical approaches have been introduced. Two performed frequently are the mini PA (MPA) and the direct anterior approach (DAA).

The MPA is a modification of the PA. Surgeons perform the THA through a small incision without cutting the abductor muscles that are critical to hip stability and gait. A study published in 2010 concluded that the MPA was associated with less pain, shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) (therefore, an economic saving), and an earlier return to walking postoperatively.7

The DAA has been around since the early days of THA. Carl Hueter first described the anterior approach to the hip in 1881 (referred to as the Hueter approach). Smith-Peterson is frequently credited with popularizing the DAA technique during his career after publishing his first description of the approach in 1917.8 About 10 years ago, the DAA showed a resurgence as another muscle-sparing alternative for THAs. The DAA is considered to be a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint, thereby preserving the stability of the joint.9-11 The optimal surgical approach is still the subject of debate.

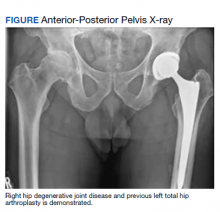

We present a male with right hip end-stage degenerative joint disease (DJD) and review some medical literature. Although other approaches to THA can be used (lateral, anterolateral), the discussion focuses on 2 muscle-sparing approaches performed frequently, the MPA and the DAA, and can be of value to primary care practitioners in their discussion with patients.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old male patient presented with progressive right hip pain. At age 37, he had a left THA via a PA due to hip dysplasia and a revision on the same hip at age 55 (the polyethylene liner was replaced and the cobalt chromium head was changed to ceramic), again through a PA. An orthopedic clinical evaluation and X-rays confirmed end-stage DJD of the right hip (Figure). He was informed to return to plan an elective THA when the “bad days were significantly greater than the good days” and/or when his functionality or quality of life was unacceptable. The orthopedic surgeon favored an MPA but offered a hand-off to colleagues who preferred the DAA. The patient was given information to review.

Discussion

No matter which approach is used, one study concluded that surgeons who perform > 50 hip replacements each year have better overall outcomes.12

The MPA emerged in the past decade as a muscle-sparing modification of the PA. The incision length (< 10 cm) is the simplest way of categorizing the surgery as an MPA. However, the amount of deep surgical dissection is a more important consideration for sparing muscle (for improved postoperative functionality, recovery, and joint stability) due to the gluteus maximus insertion, the quadratus femoris, and the piriformis tendons being left intact.13-16

Multiple studies have directly compared the MPA and PA, with variable results. One study concluded that the MPA was associated with lower surgical blood loss, lower pain at rest, and a faster recovery compared with that of the PA. Still, the study found no significant difference in postoperative laboratory values of possible markers of increased tissue damage and surgical invasiveness, such as creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels.15 Another randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 100 patients concluded that there was a trend for improved walking times and patient satisfaction at 6 weeks post-MPA vs PA.16 Other studies have found that the MPA and PA were essentially equivalent to each other regarding operative time, early postoperative outcomes, transfusion rate, hospital LOS, and postoperative complications.14 However, a recent meta-analysis found positive trends in favor of the MPA. The MPA was associated with a slight decrease in operating time, blood loss, hospital LOS, and earlier improvement in Harris hip scores. The meta-analysis found no significant decrease in the rate of dislocation or femoral fracture.13 Studies are still needed to evaluate long-term implant survival and outcomes for MPA and PA.

The DAA has received renewed attention as surgeons seek minimally invasive techniques and more rapid recoveries.6 The DAA involves a 3- to 4-inch incision on the front of the hip and enters the hip joint through the intermuscular interval between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius muscles laterally and the sartorius muscle and rectus fascia medially.9 The DAA is considered a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint (including the posterior capsule), thereby presumably preserving the stability of the joint.9 The popularity for this approach has been attributed primarily to claims of improved recovery times, lower pain levels, improved patient satisfaction, as well as improved accuracy on both implant placement/alignment and leg length restoration.17 Orthopedic surgeons are increasingly being trained in the DAA during their residency and fellowship training.