User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Early meniscal surgery on par with active rehab in under 40s

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to the results of the randomized controlled DREAM trial presented at the OARSI 2022 World Congress.

Indeed, similar clinically relevant improvements in knee pain, function, and quality of life at 12 months were seen among participants in both study arms.

“Our results highlight that decisions on surgery or nonsurgical treatment must depend on preferences and values and needs of the individuals consulting their surgeon,” Søren T. Skou, PT, MSc, PhD, reported during one of the opening sessions at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The lack of superiority was contrary to the expectations of the researchers who hypothesized that early surgical intervention in adults aged between 18 and 40 years would be more beneficial than an active rehabilitation program with later surgery if needed.

Although the results do tie in with the results of other trials and systematic reviews in older adults the reason for looking at young adults specifically, aside from the obvious differences and the origin of meniscal tears, was that no study had previously looked at this population, Dr. Skou explained.

Assembling the DREAM team

The DREAM (Danish RCT on Exercise versus Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery for Young Adults) trial “was a collaborative effort among many clinicians in Denmark – physical therapists, exercise physiologists, and surgeons,” Dr. Skou observed.

In total, 121 adults with MRI-verified meniscal tears who were eligible for surgery were recruited and randomized to either the early meniscal surgery group (n = 60) or to the exercise and education group (n = 61). The mean age was just below 30 years and 28% were female

Meniscal surgery, which was either an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or meniscal repair, was performed at seven specialist centers. The exercise and education program was delivered by trained physical therapists working at 19 participating centers. The latter consisted of 24 sessions of group-based exercise therapy and education held over a period of 12 weeks.

Participants randomized to the exercise and education arm had the option of later meniscal surgery, with one in four eventually undergoing this procedure.

No gain in pain

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the mean of four of the subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) from baseline to 12-month assessment. The KOOS4 looks at knee pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life.

“We considered a 10-point difference between groups as clinically relevant,” said Dr. Skou, but “adjusting for the baseline differences, we found no [statistical] differences or clinically relevant differences between groups.”

Improvement was seen in both groups. In an intention-to-treat analysis the KOOS4 scores improved by 19.2 points and 16.4 points respectively in the surgery and exercise and education groups, with a mean adjusted difference of 5.4 (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 11.4). There was also no difference in a per protocol analysis, which considered only those participants who received the treatment strategy they were allocated (mean adjusted difference, 5.7; 95% CI, –0.9 to 12.4).

Secondary outcomes were also similarly improved in both groups with clinically relevant increases in all four KOOS subscale scores and in the Western Ontario Meniscal Evaluation Tool (WOMET).

While there were some statistical differences between the groups, such as better KOOS pain, symptoms, and WOMET scores in the surgery group, these were felt unlikely to be clinically relevant. Likewise, there was a statistically greater improvement in muscle strength in the exercise and education group than surgery group.

There was no statistical difference in the number of serious adverse events, including worsening of symptoms with or without acute onset during activity and lateral meniscal cysts, with four reported in the surgical group and seven in the exercise and education group.

Views on results

The results of the trial, published in NEJM Evidence, garnered attention on Twitter with several physiotherapists noting the data were positive for the nonsurgical management of meniscal tears in younger adults.

During discussion at the meeting, Nadine Foster, PhD, NIHR Professor of Musculoskeletal Health in Primary Care at Keele (England) University, asked if a larger cohort might not swing the results in favor of surgery.

She said: “Congratulations on this trial. The challenge: Your 95% CIs suggest a larger trial would have concluded superiority of surgery?”

Dr. Skou responded: “Most likely the true difference is outside the clinically relevant difference, but obviously, we cannot exclude that there is actually a clinically relevant difference between groups.”

Martin Englund, MD, Phd, of Lund (Sweden) University Hospital in Sweden, pointed out that 16 patients in the exercise and education group had “crossed over” and undergone surgery. “Were there any differences for those patients?” he asked.

“We looked at whether there was a difference between those – obviously only having 16 participants, we’re not able to do any statistical comparisons – but looking just visually at the data, they seem to improve to the same extent as those undergoing nonsurgical only,” Dr. Skou said.

The 2-year MRI data are currently being examined and will “obviously also be very interesting,” he added.

The DREAM trial was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, IMK Almene Fond, Lundbeck Foundation, Spar Nord Foundation, Danish Rheumatism Association, Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, Research Council at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, and Region Zealand. Dr. Skou had no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM OARSI 2022

Denosumab boosts bone strength in glucocorticoid users

Bone strength and microarchitecture remained stronger at 24 months after treatment with denosumab compared to risedronate, in a study of 110 adults using glucocorticoids.

Patients using glucocorticoids are at increased risk for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures at both the start of treatment or as treatment continues, wrote Piet Geusens, MD, of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Imaging data collected via high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) allow for the assessment of bone microarchitecture and strength, but specific data comparing the impact of bone treatment in patients using glucocorticoids are lacking, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the researchers identified a subset of 56 patients randomized to denosumab and 54 to risedronate patients out of a total of 590 patients who were enrolled in a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial of denosumab vs. risedronate for bone mineral density. The main results of the larger trial – presented at EULAR 2018 – showed greater increases in bone strength with denosumab over risedronate in patients receiving glucocorticoids.

In the current study, the researchers reviewed HR-pQCT scans of the distal radius and tibia at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Bone strength and microarchitecture were defined in terms of failure load (FL) as a primary outcome. Patients also were divided into subpopulations of those initiating glucocorticoid treatment (GC-I) and continuing treatment (GC-C).

Baseline characteristics were mainly balanced among the treatment groups within the GC-I and GC-C categories.

Among the GC-I patients, in the denosumab group, FL increased significantly from baseline to 12 months at the radius at tibia (1.8% and 1.7%, respectively) but did not change significantly in the risedronate group, which translated to a significant treatment difference between the drugs of 3.3% for radius and 2.5% for tibia.

At 24 months, the radius measure of FL was unchanged from baseline in denosumab patients but significantly decreased in risedronate patients, with a difference of –4.1%, which translated to a significant between-treatment difference at the radius of 5.6% (P < .001). Changes at the tibia were not significantly different between the groups at 24 months.

Among the GC-C patients, FL was unchanged from baseline to 12 months for both the denosumab and risedronate groups. However, FL significantly increased with denosumab (4.3%) and remained unchanged in the risedronate group.

The researchers also found significant differences between denosumab and risedronate in percentage changes in cortical bone mineral density, and less prominent changes and differences in trabecular bone mineral density.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of the HR-pQCT scanner, which limits the measurement of trabecular microarchitecture, and the use of only standard HR-pQCT parameters, which do not allow insight into endosteal changes, and the inability to correct for multiplicity of data, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the superiority of denosumab over risedronate for preventing FL and total bone mineral density loss at the radius and tibia in new glucocorticoid users, and for increasing FL and total bone mineral density at the radius in long-term glucocorticoid users, they said.

Denosumab therefore could be a useful therapeutic option and could inform decision-making in patients initiating GC-therapy or on long-term GC-therapy, they concluded.

The study was supported by Amgen. Dr. Geusens disclosed grants from Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Fresenius, Mylan, and Sandoz, and grants and other funding from AbbVie, outside the current study.

Bone strength and microarchitecture remained stronger at 24 months after treatment with denosumab compared to risedronate, in a study of 110 adults using glucocorticoids.

Patients using glucocorticoids are at increased risk for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures at both the start of treatment or as treatment continues, wrote Piet Geusens, MD, of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Imaging data collected via high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) allow for the assessment of bone microarchitecture and strength, but specific data comparing the impact of bone treatment in patients using glucocorticoids are lacking, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the researchers identified a subset of 56 patients randomized to denosumab and 54 to risedronate patients out of a total of 590 patients who were enrolled in a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial of denosumab vs. risedronate for bone mineral density. The main results of the larger trial – presented at EULAR 2018 – showed greater increases in bone strength with denosumab over risedronate in patients receiving glucocorticoids.

In the current study, the researchers reviewed HR-pQCT scans of the distal radius and tibia at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Bone strength and microarchitecture were defined in terms of failure load (FL) as a primary outcome. Patients also were divided into subpopulations of those initiating glucocorticoid treatment (GC-I) and continuing treatment (GC-C).

Baseline characteristics were mainly balanced among the treatment groups within the GC-I and GC-C categories.

Among the GC-I patients, in the denosumab group, FL increased significantly from baseline to 12 months at the radius at tibia (1.8% and 1.7%, respectively) but did not change significantly in the risedronate group, which translated to a significant treatment difference between the drugs of 3.3% for radius and 2.5% for tibia.

At 24 months, the radius measure of FL was unchanged from baseline in denosumab patients but significantly decreased in risedronate patients, with a difference of –4.1%, which translated to a significant between-treatment difference at the radius of 5.6% (P < .001). Changes at the tibia were not significantly different between the groups at 24 months.

Among the GC-C patients, FL was unchanged from baseline to 12 months for both the denosumab and risedronate groups. However, FL significantly increased with denosumab (4.3%) and remained unchanged in the risedronate group.

The researchers also found significant differences between denosumab and risedronate in percentage changes in cortical bone mineral density, and less prominent changes and differences in trabecular bone mineral density.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of the HR-pQCT scanner, which limits the measurement of trabecular microarchitecture, and the use of only standard HR-pQCT parameters, which do not allow insight into endosteal changes, and the inability to correct for multiplicity of data, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the superiority of denosumab over risedronate for preventing FL and total bone mineral density loss at the radius and tibia in new glucocorticoid users, and for increasing FL and total bone mineral density at the radius in long-term glucocorticoid users, they said.

Denosumab therefore could be a useful therapeutic option and could inform decision-making in patients initiating GC-therapy or on long-term GC-therapy, they concluded.

The study was supported by Amgen. Dr. Geusens disclosed grants from Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Fresenius, Mylan, and Sandoz, and grants and other funding from AbbVie, outside the current study.

Bone strength and microarchitecture remained stronger at 24 months after treatment with denosumab compared to risedronate, in a study of 110 adults using glucocorticoids.

Patients using glucocorticoids are at increased risk for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures at both the start of treatment or as treatment continues, wrote Piet Geusens, MD, of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Imaging data collected via high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) allow for the assessment of bone microarchitecture and strength, but specific data comparing the impact of bone treatment in patients using glucocorticoids are lacking, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the researchers identified a subset of 56 patients randomized to denosumab and 54 to risedronate patients out of a total of 590 patients who were enrolled in a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial of denosumab vs. risedronate for bone mineral density. The main results of the larger trial – presented at EULAR 2018 – showed greater increases in bone strength with denosumab over risedronate in patients receiving glucocorticoids.

In the current study, the researchers reviewed HR-pQCT scans of the distal radius and tibia at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Bone strength and microarchitecture were defined in terms of failure load (FL) as a primary outcome. Patients also were divided into subpopulations of those initiating glucocorticoid treatment (GC-I) and continuing treatment (GC-C).

Baseline characteristics were mainly balanced among the treatment groups within the GC-I and GC-C categories.

Among the GC-I patients, in the denosumab group, FL increased significantly from baseline to 12 months at the radius at tibia (1.8% and 1.7%, respectively) but did not change significantly in the risedronate group, which translated to a significant treatment difference between the drugs of 3.3% for radius and 2.5% for tibia.

At 24 months, the radius measure of FL was unchanged from baseline in denosumab patients but significantly decreased in risedronate patients, with a difference of –4.1%, which translated to a significant between-treatment difference at the radius of 5.6% (P < .001). Changes at the tibia were not significantly different between the groups at 24 months.

Among the GC-C patients, FL was unchanged from baseline to 12 months for both the denosumab and risedronate groups. However, FL significantly increased with denosumab (4.3%) and remained unchanged in the risedronate group.

The researchers also found significant differences between denosumab and risedronate in percentage changes in cortical bone mineral density, and less prominent changes and differences in trabecular bone mineral density.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of the HR-pQCT scanner, which limits the measurement of trabecular microarchitecture, and the use of only standard HR-pQCT parameters, which do not allow insight into endosteal changes, and the inability to correct for multiplicity of data, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the superiority of denosumab over risedronate for preventing FL and total bone mineral density loss at the radius and tibia in new glucocorticoid users, and for increasing FL and total bone mineral density at the radius in long-term glucocorticoid users, they said.

Denosumab therefore could be a useful therapeutic option and could inform decision-making in patients initiating GC-therapy or on long-term GC-therapy, they concluded.

The study was supported by Amgen. Dr. Geusens disclosed grants from Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, UCB, Fresenius, Mylan, and Sandoz, and grants and other funding from AbbVie, outside the current study.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

Medical cannabis may cut opioid use for back pain, OA

CHICAGO – Access to medical cannabis (MC) cut opioid prescriptions for patients with chronic noncancer back pain and patients with osteoarthritis, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

For those with chronic back pain, the average morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day dropped from 15.1 to 11.0 (n = 186; P < .01). More than one-third of the patients (38.7%) stopped taking morphine after they filled prescriptions for medical cannabis.

Opioid prescriptions were filled 6 months before access to MC and then were compared with 6 months after access to MC.

In analyzing subgroups, the researchers found that patients who started at less than 15 MME/day and more than 15 MME/day showed significant decreases after filling the MC prescription.

Almost half (48.5%) of the patients in the group that started at less than 15 MME daily dropped to 0 MME/day, and 13.5% of patients who were getting more than 15 MME/day stopped using opioids.

Data on filled opioid prescriptions were gathered from a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) system for patients diagnosed with chronic musculoskeletal noncancer back pain who were eligible for MC access between February 2018 and July 2019.

Medical cannabis has shown benefit in treating chronic pain, but evidence has been limited on whether it can reduce opioid use, which can lead to substance abuse, addiction, overdose, and death, the researchers noted.

Researchers found that using MC via multiple routes of administration seemed to be important.

Patients who used only a single administration route showed a statistically insignificant decrease in MME/day from 20.0 to 15.1 (n = 68; P = .054), whereas patients who used two or more routes showed a significant decrease from 13.2 to 9.5 (n = 76; P < .01).

“We have many patients who are benefiting from a single route of delivery for chronic orthopedic pain,” Ari Greis, DO, a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist in Bryn Mawr, Pa., and a coauthor of the MC studies for both back pain and OA, said in an interview. “However, our data shows a greater reduction in opioid consumption in patients using more than one route of delivery.”

He said delivery modes in the studies included vaporized cannabis oil or flower; sublingual tinctures; capsules or tablets; and topical lotions, creams, and salves.

Dr. Greis is the director of the medical cannabis department at Rothman Orthopaedic Institute in Bryn Mawr, and is a senior fellow in the Institute of Emerging Health Professions and the Lambert Center for the Study of Medicinal Cannabis and Hemp, both in Philadelphia.

Medical cannabis also reduces opioids for OA

The same team of researchers, using the data from the PDMP system, showed that medical cannabis also helped reduce opioid use for osteoarthritis.

For patients using opioids for OA, there was a significant decrease in average MME/day of prescriptions filled by patients following MC access – from 18.2 to 9.8 (n = 40; P < .05). The average drop in MME/day was 46.3%. The percentage of patients who stopped using opioids was 37.5%. Pain score on a 0-10 visual analog scale decreased significantly from 6.6 (n = 36) to 5.0 (n = 26; P < .01) at 3 months and 5.4 (n = 16; P < .05) at 6 months.

Gary Stewart, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Morrow, Ga., who was not part of the studies, told this news organization that the studies offer good preliminary data to offer help with the opioid issue.

“I sometimes feel that we, as orthopedic surgeons and physicians in general, are working with one hand behind our back. We’re taking something that is a heroin or morphine derivative and giving it to our patients when we know it has a high risk of building tolerance and addiction. But at the same time, we have no alternative,” he said.

He said it’s important to remember the results from the relatively small study are preliminary and observational. People used different forms and amounts of MC and the data show only that prescriptions were filled, but not whether the cannabis was used. Prospective, controlled studies where opioids go head-to-head with MC are needed, he said.

“Still, this can lead us to more studies to give us an option [apart from] an opioid that we know is highly addictive,” he said.

Dr. Stewart is a member of the AAOS Opioid Task Force. Dr. Greis and several coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships, and other coauthors report financial ties to companies unrelated to the research presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – Access to medical cannabis (MC) cut opioid prescriptions for patients with chronic noncancer back pain and patients with osteoarthritis, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

For those with chronic back pain, the average morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day dropped from 15.1 to 11.0 (n = 186; P < .01). More than one-third of the patients (38.7%) stopped taking morphine after they filled prescriptions for medical cannabis.

Opioid prescriptions were filled 6 months before access to MC and then were compared with 6 months after access to MC.

In analyzing subgroups, the researchers found that patients who started at less than 15 MME/day and more than 15 MME/day showed significant decreases after filling the MC prescription.

Almost half (48.5%) of the patients in the group that started at less than 15 MME daily dropped to 0 MME/day, and 13.5% of patients who were getting more than 15 MME/day stopped using opioids.

Data on filled opioid prescriptions were gathered from a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) system for patients diagnosed with chronic musculoskeletal noncancer back pain who were eligible for MC access between February 2018 and July 2019.

Medical cannabis has shown benefit in treating chronic pain, but evidence has been limited on whether it can reduce opioid use, which can lead to substance abuse, addiction, overdose, and death, the researchers noted.

Researchers found that using MC via multiple routes of administration seemed to be important.

Patients who used only a single administration route showed a statistically insignificant decrease in MME/day from 20.0 to 15.1 (n = 68; P = .054), whereas patients who used two or more routes showed a significant decrease from 13.2 to 9.5 (n = 76; P < .01).

“We have many patients who are benefiting from a single route of delivery for chronic orthopedic pain,” Ari Greis, DO, a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist in Bryn Mawr, Pa., and a coauthor of the MC studies for both back pain and OA, said in an interview. “However, our data shows a greater reduction in opioid consumption in patients using more than one route of delivery.”

He said delivery modes in the studies included vaporized cannabis oil or flower; sublingual tinctures; capsules or tablets; and topical lotions, creams, and salves.

Dr. Greis is the director of the medical cannabis department at Rothman Orthopaedic Institute in Bryn Mawr, and is a senior fellow in the Institute of Emerging Health Professions and the Lambert Center for the Study of Medicinal Cannabis and Hemp, both in Philadelphia.

Medical cannabis also reduces opioids for OA

The same team of researchers, using the data from the PDMP system, showed that medical cannabis also helped reduce opioid use for osteoarthritis.

For patients using opioids for OA, there was a significant decrease in average MME/day of prescriptions filled by patients following MC access – from 18.2 to 9.8 (n = 40; P < .05). The average drop in MME/day was 46.3%. The percentage of patients who stopped using opioids was 37.5%. Pain score on a 0-10 visual analog scale decreased significantly from 6.6 (n = 36) to 5.0 (n = 26; P < .01) at 3 months and 5.4 (n = 16; P < .05) at 6 months.

Gary Stewart, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Morrow, Ga., who was not part of the studies, told this news organization that the studies offer good preliminary data to offer help with the opioid issue.

“I sometimes feel that we, as orthopedic surgeons and physicians in general, are working with one hand behind our back. We’re taking something that is a heroin or morphine derivative and giving it to our patients when we know it has a high risk of building tolerance and addiction. But at the same time, we have no alternative,” he said.

He said it’s important to remember the results from the relatively small study are preliminary and observational. People used different forms and amounts of MC and the data show only that prescriptions were filled, but not whether the cannabis was used. Prospective, controlled studies where opioids go head-to-head with MC are needed, he said.

“Still, this can lead us to more studies to give us an option [apart from] an opioid that we know is highly addictive,” he said.

Dr. Stewart is a member of the AAOS Opioid Task Force. Dr. Greis and several coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships, and other coauthors report financial ties to companies unrelated to the research presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – Access to medical cannabis (MC) cut opioid prescriptions for patients with chronic noncancer back pain and patients with osteoarthritis, according to preliminary data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

For those with chronic back pain, the average morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day dropped from 15.1 to 11.0 (n = 186; P < .01). More than one-third of the patients (38.7%) stopped taking morphine after they filled prescriptions for medical cannabis.

Opioid prescriptions were filled 6 months before access to MC and then were compared with 6 months after access to MC.

In analyzing subgroups, the researchers found that patients who started at less than 15 MME/day and more than 15 MME/day showed significant decreases after filling the MC prescription.

Almost half (48.5%) of the patients in the group that started at less than 15 MME daily dropped to 0 MME/day, and 13.5% of patients who were getting more than 15 MME/day stopped using opioids.

Data on filled opioid prescriptions were gathered from a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) system for patients diagnosed with chronic musculoskeletal noncancer back pain who were eligible for MC access between February 2018 and July 2019.

Medical cannabis has shown benefit in treating chronic pain, but evidence has been limited on whether it can reduce opioid use, which can lead to substance abuse, addiction, overdose, and death, the researchers noted.

Researchers found that using MC via multiple routes of administration seemed to be important.

Patients who used only a single administration route showed a statistically insignificant decrease in MME/day from 20.0 to 15.1 (n = 68; P = .054), whereas patients who used two or more routes showed a significant decrease from 13.2 to 9.5 (n = 76; P < .01).

“We have many patients who are benefiting from a single route of delivery for chronic orthopedic pain,” Ari Greis, DO, a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist in Bryn Mawr, Pa., and a coauthor of the MC studies for both back pain and OA, said in an interview. “However, our data shows a greater reduction in opioid consumption in patients using more than one route of delivery.”

He said delivery modes in the studies included vaporized cannabis oil or flower; sublingual tinctures; capsules or tablets; and topical lotions, creams, and salves.

Dr. Greis is the director of the medical cannabis department at Rothman Orthopaedic Institute in Bryn Mawr, and is a senior fellow in the Institute of Emerging Health Professions and the Lambert Center for the Study of Medicinal Cannabis and Hemp, both in Philadelphia.

Medical cannabis also reduces opioids for OA

The same team of researchers, using the data from the PDMP system, showed that medical cannabis also helped reduce opioid use for osteoarthritis.

For patients using opioids for OA, there was a significant decrease in average MME/day of prescriptions filled by patients following MC access – from 18.2 to 9.8 (n = 40; P < .05). The average drop in MME/day was 46.3%. The percentage of patients who stopped using opioids was 37.5%. Pain score on a 0-10 visual analog scale decreased significantly from 6.6 (n = 36) to 5.0 (n = 26; P < .01) at 3 months and 5.4 (n = 16; P < .05) at 6 months.

Gary Stewart, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Morrow, Ga., who was not part of the studies, told this news organization that the studies offer good preliminary data to offer help with the opioid issue.

“I sometimes feel that we, as orthopedic surgeons and physicians in general, are working with one hand behind our back. We’re taking something that is a heroin or morphine derivative and giving it to our patients when we know it has a high risk of building tolerance and addiction. But at the same time, we have no alternative,” he said.

He said it’s important to remember the results from the relatively small study are preliminary and observational. People used different forms and amounts of MC and the data show only that prescriptions were filled, but not whether the cannabis was used. Prospective, controlled studies where opioids go head-to-head with MC are needed, he said.

“Still, this can lead us to more studies to give us an option [apart from] an opioid that we know is highly addictive,” he said.

Dr. Stewart is a member of the AAOS Opioid Task Force. Dr. Greis and several coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships, and other coauthors report financial ties to companies unrelated to the research presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAOS 2022

Shoulder arthritis surgery: Depression complicates care

CHICAGO – new data show.

The abstract was presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Researchers, led by Keith Diamond, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Maimonides Medical Center in New York, queried a private payer database looking for patients who had primary RSA for treatment of glenohumeral OA and also had a diagnosis of depressive disorder (DD) from 2010 to 2019. Patients without DD served as the controls.

After the randomized matching with controls at a 1:5 ratio, the study consisted of 28,410 patients: 4,084 in the DD group and 24,326 in the control group.

Researchers found that patients with depression had longer hospital stays (3 vs. 2 days, P = .0007). They also had higher frequency and odds of developing side effects within the period of care (47.4% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 2.27; 95% CI, 2.10-2.45, P < .0001).

Patients with depression also had significantly higher rates of medical complications surrounding the surgery and costs were higher ($19,363 vs. $17,927, P < .0001).

Pneumonia rates were much higher in patients with DD (10% vs. 1.8%; OR, 2.88; P < .0001).

Patients with depression had higher odds of cerebrovascular accident (3.1% vs. 0.7%; OR, 2.69, P < .0001); myocardial infarctions (2% vs. 0.4%; OR, 2.54; P < .0001); acute kidney injuries (11.1% vs. 2.3%; OR, 2.11, P < .0001); surgical site infections (4.4% vs. 2.4%; OR, 1.52, P < .0001); and other complications, the authors wrote.

Dr. Diamond said in an interview that there may be a few potential reasons for the associations.

In regard to the strong association with pneumonia, Dr. Diamond hypothesized, “patients with depression can be shown to have lower respiratory drive. If a patient isn’t motivated to get out of bed, that can lead to decreased inflation of the lungs.”

Acute kidney injury could be linked with depression-related lack of self-care in properly hydrating, he said. Surgical site infections could come from suboptimal hygiene related to managing the cast after surgery, which may be more difficult when patients also struggle with depression.

Asked to comment on Dr. Diamond’s study, Grant Garrigues, MD, an associate professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and director of upper extremity research, told this news organization the study helps confirm known associations between depression and arthritis.

“We know that people with depression and anxiety feel pain differently,” he said. “It might have to do with your outlook – are you catastrophizing or thinking it’s a minor inconvenience? It’s not that it’s just in your head – you physically feel it differently. That is something we’re certainly attuned to. We want to make sure the mental health part of the picture is optimized as much as possible.”

He added that there is increasing evidence of links between depression and the development of arthritis.

“I’m not saying that everyone with arthritis has depression, but with arthritis being multifactorial, there’s a relatively high incidence of symptomatic arthritis in patients with depression,” Dr. Garrigues said.

“We think it may have something to do with the fight-or-flight hormones in your body that may be revved up if you are living in a stressful environment or are living with a mental health problem. Those will actually change – on a cellular and biochemical basis – some of the things that affect arthritis.”

Stronger emphasis on mental health

Dr. Diamond said the field needs more emphasis on perioperative state of mind.

“As orthopedic surgeons, we are preoccupied with the mechanical, the structural aspects of health care as we try to fix bones, ligaments, and tendons. But I think we need to recognize and explore the connection between the psychiatric and psychological health with our musculoskeletal health.”

He noted that, in the preoperative setting, providers look for hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, and other conditions that could complicate surgical outcomes and said mental health should be a factor in whether a surgery proceeds.

“If someone’s diabetes isn’t controlled you can delay an elective case until their [hemoglobin] A1c is under the recommended limit and you get clearance from their primary care doctor. I think that’s something that should be applied to patients with depressive disorders,” Dr. Diamond said.

This study did not distinguish between patients who were being treated for depression at the time of surgery and those not on treatment. More study related to whether treatment affects depression’s association with RSA outcomes is needed, Dr. Diamond added.

Dr. Garrigues said he talks candidly with patients considering surgery about how they are managing their mental health struggles.

“If they say they haven’t seen their psychiatrist or are off their medications, that’s a nonstarter,” he said.

“Anything outside of the surgery you can optimize, whether it’s mental health, medical, social situations – you want to have all your ducks in a row before you dive into surgery,” Dr. Garrigues said.

He added that patients’ mental health status may even affect the venue for the patient – whether outpatient or inpatient, where they can get more supervision and help in making transitions after surgery.

Dr. Diamond and coauthors and Dr. Garrigues disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – new data show.

The abstract was presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Researchers, led by Keith Diamond, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Maimonides Medical Center in New York, queried a private payer database looking for patients who had primary RSA for treatment of glenohumeral OA and also had a diagnosis of depressive disorder (DD) from 2010 to 2019. Patients without DD served as the controls.

After the randomized matching with controls at a 1:5 ratio, the study consisted of 28,410 patients: 4,084 in the DD group and 24,326 in the control group.

Researchers found that patients with depression had longer hospital stays (3 vs. 2 days, P = .0007). They also had higher frequency and odds of developing side effects within the period of care (47.4% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 2.27; 95% CI, 2.10-2.45, P < .0001).

Patients with depression also had significantly higher rates of medical complications surrounding the surgery and costs were higher ($19,363 vs. $17,927, P < .0001).

Pneumonia rates were much higher in patients with DD (10% vs. 1.8%; OR, 2.88; P < .0001).

Patients with depression had higher odds of cerebrovascular accident (3.1% vs. 0.7%; OR, 2.69, P < .0001); myocardial infarctions (2% vs. 0.4%; OR, 2.54; P < .0001); acute kidney injuries (11.1% vs. 2.3%; OR, 2.11, P < .0001); surgical site infections (4.4% vs. 2.4%; OR, 1.52, P < .0001); and other complications, the authors wrote.

Dr. Diamond said in an interview that there may be a few potential reasons for the associations.

In regard to the strong association with pneumonia, Dr. Diamond hypothesized, “patients with depression can be shown to have lower respiratory drive. If a patient isn’t motivated to get out of bed, that can lead to decreased inflation of the lungs.”

Acute kidney injury could be linked with depression-related lack of self-care in properly hydrating, he said. Surgical site infections could come from suboptimal hygiene related to managing the cast after surgery, which may be more difficult when patients also struggle with depression.

Asked to comment on Dr. Diamond’s study, Grant Garrigues, MD, an associate professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and director of upper extremity research, told this news organization the study helps confirm known associations between depression and arthritis.

“We know that people with depression and anxiety feel pain differently,” he said. “It might have to do with your outlook – are you catastrophizing or thinking it’s a minor inconvenience? It’s not that it’s just in your head – you physically feel it differently. That is something we’re certainly attuned to. We want to make sure the mental health part of the picture is optimized as much as possible.”

He added that there is increasing evidence of links between depression and the development of arthritis.

“I’m not saying that everyone with arthritis has depression, but with arthritis being multifactorial, there’s a relatively high incidence of symptomatic arthritis in patients with depression,” Dr. Garrigues said.

“We think it may have something to do with the fight-or-flight hormones in your body that may be revved up if you are living in a stressful environment or are living with a mental health problem. Those will actually change – on a cellular and biochemical basis – some of the things that affect arthritis.”

Stronger emphasis on mental health

Dr. Diamond said the field needs more emphasis on perioperative state of mind.

“As orthopedic surgeons, we are preoccupied with the mechanical, the structural aspects of health care as we try to fix bones, ligaments, and tendons. But I think we need to recognize and explore the connection between the psychiatric and psychological health with our musculoskeletal health.”

He noted that, in the preoperative setting, providers look for hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, and other conditions that could complicate surgical outcomes and said mental health should be a factor in whether a surgery proceeds.

“If someone’s diabetes isn’t controlled you can delay an elective case until their [hemoglobin] A1c is under the recommended limit and you get clearance from their primary care doctor. I think that’s something that should be applied to patients with depressive disorders,” Dr. Diamond said.

This study did not distinguish between patients who were being treated for depression at the time of surgery and those not on treatment. More study related to whether treatment affects depression’s association with RSA outcomes is needed, Dr. Diamond added.

Dr. Garrigues said he talks candidly with patients considering surgery about how they are managing their mental health struggles.

“If they say they haven’t seen their psychiatrist or are off their medications, that’s a nonstarter,” he said.

“Anything outside of the surgery you can optimize, whether it’s mental health, medical, social situations – you want to have all your ducks in a row before you dive into surgery,” Dr. Garrigues said.

He added that patients’ mental health status may even affect the venue for the patient – whether outpatient or inpatient, where they can get more supervision and help in making transitions after surgery.

Dr. Diamond and coauthors and Dr. Garrigues disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – new data show.

The abstract was presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Researchers, led by Keith Diamond, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Maimonides Medical Center in New York, queried a private payer database looking for patients who had primary RSA for treatment of glenohumeral OA and also had a diagnosis of depressive disorder (DD) from 2010 to 2019. Patients without DD served as the controls.

After the randomized matching with controls at a 1:5 ratio, the study consisted of 28,410 patients: 4,084 in the DD group and 24,326 in the control group.

Researchers found that patients with depression had longer hospital stays (3 vs. 2 days, P = .0007). They also had higher frequency and odds of developing side effects within the period of care (47.4% vs. 14.7%; odds ratio, 2.27; 95% CI, 2.10-2.45, P < .0001).

Patients with depression also had significantly higher rates of medical complications surrounding the surgery and costs were higher ($19,363 vs. $17,927, P < .0001).

Pneumonia rates were much higher in patients with DD (10% vs. 1.8%; OR, 2.88; P < .0001).

Patients with depression had higher odds of cerebrovascular accident (3.1% vs. 0.7%; OR, 2.69, P < .0001); myocardial infarctions (2% vs. 0.4%; OR, 2.54; P < .0001); acute kidney injuries (11.1% vs. 2.3%; OR, 2.11, P < .0001); surgical site infections (4.4% vs. 2.4%; OR, 1.52, P < .0001); and other complications, the authors wrote.

Dr. Diamond said in an interview that there may be a few potential reasons for the associations.

In regard to the strong association with pneumonia, Dr. Diamond hypothesized, “patients with depression can be shown to have lower respiratory drive. If a patient isn’t motivated to get out of bed, that can lead to decreased inflation of the lungs.”

Acute kidney injury could be linked with depression-related lack of self-care in properly hydrating, he said. Surgical site infections could come from suboptimal hygiene related to managing the cast after surgery, which may be more difficult when patients also struggle with depression.

Asked to comment on Dr. Diamond’s study, Grant Garrigues, MD, an associate professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and director of upper extremity research, told this news organization the study helps confirm known associations between depression and arthritis.

“We know that people with depression and anxiety feel pain differently,” he said. “It might have to do with your outlook – are you catastrophizing or thinking it’s a minor inconvenience? It’s not that it’s just in your head – you physically feel it differently. That is something we’re certainly attuned to. We want to make sure the mental health part of the picture is optimized as much as possible.”

He added that there is increasing evidence of links between depression and the development of arthritis.

“I’m not saying that everyone with arthritis has depression, but with arthritis being multifactorial, there’s a relatively high incidence of symptomatic arthritis in patients with depression,” Dr. Garrigues said.

“We think it may have something to do with the fight-or-flight hormones in your body that may be revved up if you are living in a stressful environment or are living with a mental health problem. Those will actually change – on a cellular and biochemical basis – some of the things that affect arthritis.”

Stronger emphasis on mental health

Dr. Diamond said the field needs more emphasis on perioperative state of mind.

“As orthopedic surgeons, we are preoccupied with the mechanical, the structural aspects of health care as we try to fix bones, ligaments, and tendons. But I think we need to recognize and explore the connection between the psychiatric and psychological health with our musculoskeletal health.”

He noted that, in the preoperative setting, providers look for hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, and other conditions that could complicate surgical outcomes and said mental health should be a factor in whether a surgery proceeds.

“If someone’s diabetes isn’t controlled you can delay an elective case until their [hemoglobin] A1c is under the recommended limit and you get clearance from their primary care doctor. I think that’s something that should be applied to patients with depressive disorders,” Dr. Diamond said.

This study did not distinguish between patients who were being treated for depression at the time of surgery and those not on treatment. More study related to whether treatment affects depression’s association with RSA outcomes is needed, Dr. Diamond added.

Dr. Garrigues said he talks candidly with patients considering surgery about how they are managing their mental health struggles.

“If they say they haven’t seen their psychiatrist or are off their medications, that’s a nonstarter,” he said.

“Anything outside of the surgery you can optimize, whether it’s mental health, medical, social situations – you want to have all your ducks in a row before you dive into surgery,” Dr. Garrigues said.

He added that patients’ mental health status may even affect the venue for the patient – whether outpatient or inpatient, where they can get more supervision and help in making transitions after surgery.

Dr. Diamond and coauthors and Dr. Garrigues disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAOS 2022

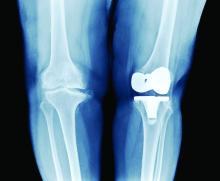

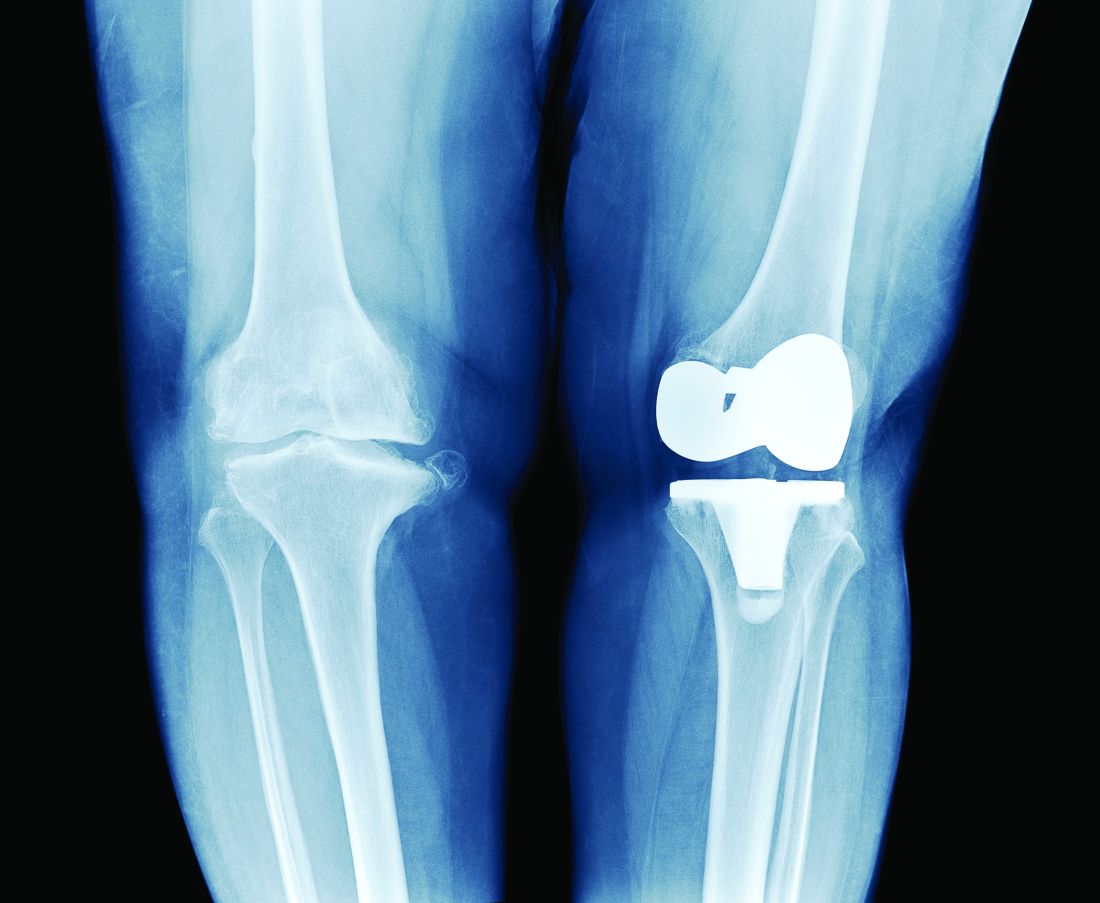

TKA outcomes for age 80+ similar to younger patients

CHICAGO - Patients 80 years or older undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have similar odds of complications, compared with 65- to 79-year-old patients, an analysis of more than 1.7 million cases suggests.

Priscilla Varghese, MBA, MS, and an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn, led the research, presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2022 annual meeting.

Ms. Varghese’s team queried a Medicare claims database for the years 2005-2014 and analyzed information from 295,908 octogenarians and 1.4 million control patients aged 65-79 who received TKA.

Study group patients were randomly matched to controls in a 1:5 ratio according to gender and comorbidities, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and kidney failure.

Octogenarians were found to have higher incidence and odds of 90-day readmission rates (10.59% vs. 9.35%; odds ratio, 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.16; P < .0001).

Hospital stays were also longer (3.69 days ± 1.95 vs. 3.23 days ± 1.83; P < .0001), compared with controls.

Reassuring older patients

However, Ms. Varghese told this news organization she was surprised to find that the older group had equal incidence and odds of developing medical complications (1.26% vs. 1.26%; OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.03; P =.99).

“That’s a really important piece of information to have when we are advising 80-year-olds – to be able to say their risk of adverse outcomes is similar to someone who’s 10 years, 15 years younger,” she said. “It’s really reassuring.”

These results offer good news to older patients who might be hesitant to undergo the surgery, and good news in general as life expectancy increases and people stay active long into their later years, forecasting the need for more knee replacements.

The number of total knee replacements is expected to rise dramatically in the United States.

In a 2017 study published in Osteoarthritis Cartilage, the authors write, “the number of TKAs in the U.S., which already has the highest [incidence rate] of knee arthroplasty in the world, is expected to increase 143% by 2050.”

Thomas Fleeter, MD, an orthopedic surgeon practicing in Reston, Virginia, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization this study reinforces that “it’s OK to do knee replacements in elderly people; you just have to pick the right ones.”

He pointed out that the study also showed that the 80-and-older patients don’t have the added risk of loosening their mechanical components after the surgery, likely because they are less inclined than their younger counterparts to follow surgery with strenuous activities.

In a subanalysis, revision rates were also lower for the octogenarians (0.01% vs. 0.02% for controls).

Octogenarians who had TKA were found to have lower incidence and odds (1.6% vs. 1.93%; OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.83-0.88, P < .001) of implant-related complications, compared with the younger group.

The increased length of stay would be expected, Dr. Fleeter said, because those 80-plus may need a bit more help getting out of bed and may not have as much support at home.

A total knee replacement can have the substantial benefit of improving octogenarians’ ability to maintain their independence longer by facilitating driving or walking.

“It’s a small and manageable risk if you pick the right patients,” he said.

Demand for TKAs rises as population ages

As patients are living longer and wanting to maintain their mobility and as obesity rates are rising, more older patients will seek total knee replacements, especially since the payoff is high, Ms. Varghese noted.

“People who undergo this operation tend to show remarkable decreases in pain and increases in range of motion,” she said.

This study has the advantage of a more personalized look at risks of TKA because it stratifies age groups.

“The literature tends to look at the elderly population as one big cohort – 65 and older,” Ms. Varghese said. “We were able to provide patients more specific data.”

Ms. Varghese and Dr. Fleeter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO - Patients 80 years or older undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have similar odds of complications, compared with 65- to 79-year-old patients, an analysis of more than 1.7 million cases suggests.

Priscilla Varghese, MBA, MS, and an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn, led the research, presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2022 annual meeting.

Ms. Varghese’s team queried a Medicare claims database for the years 2005-2014 and analyzed information from 295,908 octogenarians and 1.4 million control patients aged 65-79 who received TKA.

Study group patients were randomly matched to controls in a 1:5 ratio according to gender and comorbidities, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and kidney failure.

Octogenarians were found to have higher incidence and odds of 90-day readmission rates (10.59% vs. 9.35%; odds ratio, 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.16; P < .0001).

Hospital stays were also longer (3.69 days ± 1.95 vs. 3.23 days ± 1.83; P < .0001), compared with controls.

Reassuring older patients

However, Ms. Varghese told this news organization she was surprised to find that the older group had equal incidence and odds of developing medical complications (1.26% vs. 1.26%; OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.03; P =.99).

“That’s a really important piece of information to have when we are advising 80-year-olds – to be able to say their risk of adverse outcomes is similar to someone who’s 10 years, 15 years younger,” she said. “It’s really reassuring.”

These results offer good news to older patients who might be hesitant to undergo the surgery, and good news in general as life expectancy increases and people stay active long into their later years, forecasting the need for more knee replacements.

The number of total knee replacements is expected to rise dramatically in the United States.

In a 2017 study published in Osteoarthritis Cartilage, the authors write, “the number of TKAs in the U.S., which already has the highest [incidence rate] of knee arthroplasty in the world, is expected to increase 143% by 2050.”

Thomas Fleeter, MD, an orthopedic surgeon practicing in Reston, Virginia, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization this study reinforces that “it’s OK to do knee replacements in elderly people; you just have to pick the right ones.”

He pointed out that the study also showed that the 80-and-older patients don’t have the added risk of loosening their mechanical components after the surgery, likely because they are less inclined than their younger counterparts to follow surgery with strenuous activities.

In a subanalysis, revision rates were also lower for the octogenarians (0.01% vs. 0.02% for controls).

Octogenarians who had TKA were found to have lower incidence and odds (1.6% vs. 1.93%; OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.83-0.88, P < .001) of implant-related complications, compared with the younger group.

The increased length of stay would be expected, Dr. Fleeter said, because those 80-plus may need a bit more help getting out of bed and may not have as much support at home.

A total knee replacement can have the substantial benefit of improving octogenarians’ ability to maintain their independence longer by facilitating driving or walking.

“It’s a small and manageable risk if you pick the right patients,” he said.

Demand for TKAs rises as population ages

As patients are living longer and wanting to maintain their mobility and as obesity rates are rising, more older patients will seek total knee replacements, especially since the payoff is high, Ms. Varghese noted.

“People who undergo this operation tend to show remarkable decreases in pain and increases in range of motion,” she said.

This study has the advantage of a more personalized look at risks of TKA because it stratifies age groups.

“The literature tends to look at the elderly population as one big cohort – 65 and older,” Ms. Varghese said. “We were able to provide patients more specific data.”

Ms. Varghese and Dr. Fleeter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO - Patients 80 years or older undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have similar odds of complications, compared with 65- to 79-year-old patients, an analysis of more than 1.7 million cases suggests.

Priscilla Varghese, MBA, MS, and an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn, led the research, presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2022 annual meeting.

Ms. Varghese’s team queried a Medicare claims database for the years 2005-2014 and analyzed information from 295,908 octogenarians and 1.4 million control patients aged 65-79 who received TKA.

Study group patients were randomly matched to controls in a 1:5 ratio according to gender and comorbidities, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and kidney failure.

Octogenarians were found to have higher incidence and odds of 90-day readmission rates (10.59% vs. 9.35%; odds ratio, 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.16; P < .0001).

Hospital stays were also longer (3.69 days ± 1.95 vs. 3.23 days ± 1.83; P < .0001), compared with controls.

Reassuring older patients

However, Ms. Varghese told this news organization she was surprised to find that the older group had equal incidence and odds of developing medical complications (1.26% vs. 1.26%; OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.03; P =.99).

“That’s a really important piece of information to have when we are advising 80-year-olds – to be able to say their risk of adverse outcomes is similar to someone who’s 10 years, 15 years younger,” she said. “It’s really reassuring.”

These results offer good news to older patients who might be hesitant to undergo the surgery, and good news in general as life expectancy increases and people stay active long into their later years, forecasting the need for more knee replacements.

The number of total knee replacements is expected to rise dramatically in the United States.

In a 2017 study published in Osteoarthritis Cartilage, the authors write, “the number of TKAs in the U.S., which already has the highest [incidence rate] of knee arthroplasty in the world, is expected to increase 143% by 2050.”

Thomas Fleeter, MD, an orthopedic surgeon practicing in Reston, Virginia, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization this study reinforces that “it’s OK to do knee replacements in elderly people; you just have to pick the right ones.”

He pointed out that the study also showed that the 80-and-older patients don’t have the added risk of loosening their mechanical components after the surgery, likely because they are less inclined than their younger counterparts to follow surgery with strenuous activities.

In a subanalysis, revision rates were also lower for the octogenarians (0.01% vs. 0.02% for controls).

Octogenarians who had TKA were found to have lower incidence and odds (1.6% vs. 1.93%; OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.83-0.88, P < .001) of implant-related complications, compared with the younger group.

The increased length of stay would be expected, Dr. Fleeter said, because those 80-plus may need a bit more help getting out of bed and may not have as much support at home.

A total knee replacement can have the substantial benefit of improving octogenarians’ ability to maintain their independence longer by facilitating driving or walking.

“It’s a small and manageable risk if you pick the right patients,” he said.

Demand for TKAs rises as population ages

As patients are living longer and wanting to maintain their mobility and as obesity rates are rising, more older patients will seek total knee replacements, especially since the payoff is high, Ms. Varghese noted.

“People who undergo this operation tend to show remarkable decreases in pain and increases in range of motion,” she said.

This study has the advantage of a more personalized look at risks of TKA because it stratifies age groups.

“The literature tends to look at the elderly population as one big cohort – 65 and older,” Ms. Varghese said. “We were able to provide patients more specific data.”

Ms. Varghese and Dr. Fleeter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Osteoarthritis burden grows worldwide, Global Burden of Disease study finds

Prevalent cases of osteoarthritis increased significantly worldwide from 1990 to 2019, based on data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

OA remains a highly prevalent condition worldwide, with no nonsurgical interventions to prevent progression, wrote Huibin Long, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and colleagues.

Data from previous studies show that the prevalence of OA varies depending on the joints involved, with the knee being most frequently affected. However, site-specific data on OA trends and disease burden across regions or territories has not been well documented, they said.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers analyzed data from the Global Burden of Disease Study, an ongoing project involving researchers in approximately 200 countries and territories to provide up-to-date information on the disease burdens of more than 350 types of diseases and injuries.

The Global Burden of Disease study for 2019 (GBD 2019) included data on age- and sex-specific incidence, prevalence, mortality, years of life lost, and disability-adjusted life-years for 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories. Countries were divided into five groups based on a composite sociodemographic index (SDI) of factors including fertility, income, and educational attainment; the SDI represents the quality and availability of health care, the researchers wrote.

OA was defined as radiologically confirmed Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2-4 and pain for at least 1 month during the past 12 months.

Overall, prevalent OA cases increased by 113.25% worldwide, from 247.51 million in 1990 to 527.81 million in 2019. China had the highest number of cases in 2019 (132.81 million), followed by India (62.36 million), and the United States (51.87 million). The percentage increases for these three countries from 1990 to 2019 were 156.58%, 165.75%, and 79.63%, respectively.

To further calculate trends in OA, the researchers used age-standardized prevalence rates (ASRs). The overall ASRs increased from 6,173.38 per 100,000 individuals in 1990 to 6,348.25 per 100,000 individuals in 2019, for an estimated annual percentage change of 0.12%. The ASR of OA varied substantially across countries in 2019, with the highest level observed in the United States (9,960.88 per 100,000) and the lowest in Timor-Leste (3,768.44 per 100,000). The prevalence of OA was higher in countries with higher SDI levels, such as the United States and the Republic of Korea, and increased life expectancy may play a role, they said.

OA prevalence increased with age; the prevalence of OA among adults peaked at 60-64 years in both 1990 and 2019. The absolute number of cases rose most sharply among individuals aged 95 years and older, increasing nearly fourfold during the 30-year period. The ASR of OA was also highest for people aged 95 years or older.

As for site-specific prevalence in 2019, OA of the knee was the most common site worldwide (60.6% of cases), followed by OA of the hand (23.7%), other joint sites (10.2%), and the hip (5.5%).

The ASR of OA increased for knee, hip, and other joints, with estimated annual percentage changes of 0.32%, 0.28%, and 0.18%, respectively, but decreased by 0.36% for the hand.

OA in large joints, such as the knee and hip, is often associated with higher disease burden, the researchers said. However, this held true for only knee OA because in this study, “globally as well as in most regions and countries, joints with the main disease burden were the knee, followed by the hand, [and] other joints except spine, while OA [of the] hip contributed the least,” they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the adjustments from individual studies in the GBD and the exclusion of spinal symptoms, which might have contributed to an underestimation of disease burden, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of assessment of the effect of health systems as part of the SDI, they said.

Overall, the results support a trend of increasing OA worldwide that is expected to continue in part because of the aging global population and the ongoing epidemic of obesity, the researchers said.

“Public awareness of the modifiable risk factors, and potential education programs of prevention of disease occurrence are essential to alleviate the enormous burden of OA,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Beijing Postdoctoral Research Foundation and National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Prevalent cases of osteoarthritis increased significantly worldwide from 1990 to 2019, based on data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

OA remains a highly prevalent condition worldwide, with no nonsurgical interventions to prevent progression, wrote Huibin Long, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and colleagues.

Data from previous studies show that the prevalence of OA varies depending on the joints involved, with the knee being most frequently affected. However, site-specific data on OA trends and disease burden across regions or territories has not been well documented, they said.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers analyzed data from the Global Burden of Disease Study, an ongoing project involving researchers in approximately 200 countries and territories to provide up-to-date information on the disease burdens of more than 350 types of diseases and injuries.

The Global Burden of Disease study for 2019 (GBD 2019) included data on age- and sex-specific incidence, prevalence, mortality, years of life lost, and disability-adjusted life-years for 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories. Countries were divided into five groups based on a composite sociodemographic index (SDI) of factors including fertility, income, and educational attainment; the SDI represents the quality and availability of health care, the researchers wrote.