User login

Osteoporosis medication use down in older women

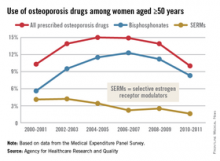

Even as the number of women aged 50 years and older continues to rise, the percentage who are taking osteoporosis medications has fallen by one-third since 2004-2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported.

In 2004-2005, 15% of all women aged 50 years and over were using some form of prescribed osteoporosis drug, but that number had dropped to 10% by 2010-2011, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The total number of women aged 50 and older increased from 47.8 million to 55.2 million over that same time period.

In 2010-2011, 8.3% of all women aged at least 50 years were using bisphosphonates, down from a high of 12.3% in 2006-2007 but up from 5.6% in 2000-2001. Use of the next most popular form of osteoporosis medication, the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), declined from 4.2% of all older women in 2002-2003 to 1.6% in 2010-2011, the AHRQ said.

Data for denosumab (Prolia), a fully human monoclonal antibody drug approved for the treatment of osteoporosis, were not available in the MEPS during the analysis period.

Even as the number of women aged 50 years and older continues to rise, the percentage who are taking osteoporosis medications has fallen by one-third since 2004-2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported.

In 2004-2005, 15% of all women aged 50 years and over were using some form of prescribed osteoporosis drug, but that number had dropped to 10% by 2010-2011, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The total number of women aged 50 and older increased from 47.8 million to 55.2 million over that same time period.

In 2010-2011, 8.3% of all women aged at least 50 years were using bisphosphonates, down from a high of 12.3% in 2006-2007 but up from 5.6% in 2000-2001. Use of the next most popular form of osteoporosis medication, the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), declined from 4.2% of all older women in 2002-2003 to 1.6% in 2010-2011, the AHRQ said.

Data for denosumab (Prolia), a fully human monoclonal antibody drug approved for the treatment of osteoporosis, were not available in the MEPS during the analysis period.

Even as the number of women aged 50 years and older continues to rise, the percentage who are taking osteoporosis medications has fallen by one-third since 2004-2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported.

In 2004-2005, 15% of all women aged 50 years and over were using some form of prescribed osteoporosis drug, but that number had dropped to 10% by 2010-2011, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The total number of women aged 50 and older increased from 47.8 million to 55.2 million over that same time period.

In 2010-2011, 8.3% of all women aged at least 50 years were using bisphosphonates, down from a high of 12.3% in 2006-2007 but up from 5.6% in 2000-2001. Use of the next most popular form of osteoporosis medication, the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), declined from 4.2% of all older women in 2002-2003 to 1.6% in 2010-2011, the AHRQ said.

Data for denosumab (Prolia), a fully human monoclonal antibody drug approved for the treatment of osteoporosis, were not available in the MEPS during the analysis period.

Vitamin D landscape marked by lack of consensus

If you’re stumped about what to tell patients who ask you if they should be adding supplemental vitamin D to their diet, you’re not alone.

Speaker after speaker at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health acknowledged that there is general disagreement among well-respected scientists and medical organizations not only about recommended intakes, but about whether supplementation of vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) has any impact on ailments ranging from depression and nonspecific pain to hypertension and fall prevention.

“Most people agree that at least in high-risk individuals with osteoporosis, vitamin D has an impact on bone and skeletal health, but maybe not in those who are asymptomatic and in healthy individuals as a preventive tool,” said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen, director of clinical and translational research and a senior scientist at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, Me. “There seems to be growing evidence that in high-risk individuals, or in those who repeatedly fall, vitamin D may have an impact, particularly in those with very-low levels of 25-D.”

Other relationships lack conclusive randomized control data, although there are strong observational data for vitamin D’s role in preventing type 2 diabetes. Dr. Rosen is one of the investigators in a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases–funded clinical trial known as D2D: a study of 4,000 IU of vitamin D vs. placebo in high-risk individuals with obesity and prediabetes. The primary outcome is time to onset of type 2 diabetes. “Currently, that [trial is] in its second year and is about 30% recruited,” said Dr. Rosen, who is also a member of the FDA Advisory Panel on Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs. “One of the biggest obstacles to recruitment has been the constant use of vitamin D by people being screened. [They say] ‘Why should I go into a clinical trial when I’m taking vitamin D, and my doctor tells me that it will prevent diabetes?’”

The potential benefit of vitamin D intake on reducing the risk for developing cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke is being investigated in the NIH-funded VITAL trial. Clinicians involved in this project have enrolled more than 28,000 men and women with no prior history of these illnesses, investigating the impact of taking vitamin D3 supplements (2,000 IU/day) or omega 3 fatty acids (1 G/day).

In the meantime, current vitamin D guidance and conclusions differ among leading medical organizations. For example, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends a daily dose of 4,000 IU for fall prevention in elderly individuals. This differs from the daily dose for adults recommended by the Endocrine Society (1,500-2,000 IU), Institute of Medicine (an average requirement of 400 IU and 600-800 IU meeting the greatest need), the United States Preventive Services Task Force (600-800 IU as a fall-prevention strategy), the Standing Committee of European Doctors (600-800 IU), and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (400-1,000 IU). “How do we reconcile vitamin D intake with vitamin D levels?” asked Dr. Rosen, who is also a professor of medicine at Tufts University. “This is one of the hallmarks of the questions or problems we have, or the lack of consistency of data. We know that intakes do not reflect serum 25-D levels to a great extent.”

In addition, the terminology for serum 25-D is not clear. “Is it a deficiency? Is it a disease? What does that mean?” he asked. “More importantly, we don’t really understand what vitamin D insufficiency is. Is it a disease? Not a disease? Is it inadequate intake?”

The definition of optimal 25-D is also a matter of debate, he continued. “What’s the upper level? What does pharmacological treatment mean with respect to long-term outcomes. What is the tolerable upper limit? What is the potentially toxic limit?”

A lack of consensus also exists regarding one’s risk of vitamin D deficiency. For example, the AGS puts this risk at less than 30 ng/mL, the Endocrine Society at less than 20 ng/mL, and the Institute of Medicine at less than 12 ng/mL. “We have a lot of inconsistency in the data,” Dr. Rosen concluded. “There’s not unanimity in recommendations, even among so-called experts.”

During the same session, Dr. Peter Millard presented findings from a national analysis of vitamin D level testing in adult patients conducted from January 2013 to September 2014. The sample, drawn from Athenahealth integrated electronic health records (EHRs), included more than 6,000 internists and family physicians and 2,000 nonphysician clinicians, translating into an estimated 900,000 patient encounters per month. During that time period 4%-5% of all adult patient encounters were associated with a vitamin D test ordered.

“Curiously, the Sunbelt states of Arizona and Nevada have a high testing rate, in the 8.5%-10.7% range,” said Dr. Millard, a family physician who practices at Seaport Community Health Center in Belfast, Me. “Perhaps it’s because of snowbirds coming down from Canada to get tested. I don’t know. There are certainly lots of retirees in those two states. There are also high levels of testing in Illinois, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Delaware. I don’t have a hypothesis as to why there are variations, but that’s about 10% of all encounters associated with a vitamin D test in those states, which seems like quite a high number.”

The greatest proportion of tests occurred in patients over the age of 65 (39%) years, and about 70% of all vitamin D tests were conducted in females.

Fewer than 0.1% of tests were associated with a diagnosis of osteoporosis. The most common diagnoses associated with ordering of a vitamin D test were depression and falls. “This was particularly true in the elderly group, where falls became much more important, and depression slightly less,” Dr. Millard said. He noted that the EHR findings “don’t answer many questions but clearly the cost for [vitamin D] testing itself is significant. The amount of time my colleagues are spending doing tests and interpreting tests for patients [and] deciding what to do about those results is very considerable. In the long run, the research to resolve these issues may not be anywhere near as expensive as continuing to do what we’re doing now.”

Dr. Rosen and Dr. Millard reporting having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

If you’re stumped about what to tell patients who ask you if they should be adding supplemental vitamin D to their diet, you’re not alone.

Speaker after speaker at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health acknowledged that there is general disagreement among well-respected scientists and medical organizations not only about recommended intakes, but about whether supplementation of vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) has any impact on ailments ranging from depression and nonspecific pain to hypertension and fall prevention.

“Most people agree that at least in high-risk individuals with osteoporosis, vitamin D has an impact on bone and skeletal health, but maybe not in those who are asymptomatic and in healthy individuals as a preventive tool,” said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen, director of clinical and translational research and a senior scientist at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, Me. “There seems to be growing evidence that in high-risk individuals, or in those who repeatedly fall, vitamin D may have an impact, particularly in those with very-low levels of 25-D.”

Other relationships lack conclusive randomized control data, although there are strong observational data for vitamin D’s role in preventing type 2 diabetes. Dr. Rosen is one of the investigators in a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases–funded clinical trial known as D2D: a study of 4,000 IU of vitamin D vs. placebo in high-risk individuals with obesity and prediabetes. The primary outcome is time to onset of type 2 diabetes. “Currently, that [trial is] in its second year and is about 30% recruited,” said Dr. Rosen, who is also a member of the FDA Advisory Panel on Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs. “One of the biggest obstacles to recruitment has been the constant use of vitamin D by people being screened. [They say] ‘Why should I go into a clinical trial when I’m taking vitamin D, and my doctor tells me that it will prevent diabetes?’”

The potential benefit of vitamin D intake on reducing the risk for developing cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke is being investigated in the NIH-funded VITAL trial. Clinicians involved in this project have enrolled more than 28,000 men and women with no prior history of these illnesses, investigating the impact of taking vitamin D3 supplements (2,000 IU/day) or omega 3 fatty acids (1 G/day).

In the meantime, current vitamin D guidance and conclusions differ among leading medical organizations. For example, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends a daily dose of 4,000 IU for fall prevention in elderly individuals. This differs from the daily dose for adults recommended by the Endocrine Society (1,500-2,000 IU), Institute of Medicine (an average requirement of 400 IU and 600-800 IU meeting the greatest need), the United States Preventive Services Task Force (600-800 IU as a fall-prevention strategy), the Standing Committee of European Doctors (600-800 IU), and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (400-1,000 IU). “How do we reconcile vitamin D intake with vitamin D levels?” asked Dr. Rosen, who is also a professor of medicine at Tufts University. “This is one of the hallmarks of the questions or problems we have, or the lack of consistency of data. We know that intakes do not reflect serum 25-D levels to a great extent.”

In addition, the terminology for serum 25-D is not clear. “Is it a deficiency? Is it a disease? What does that mean?” he asked. “More importantly, we don’t really understand what vitamin D insufficiency is. Is it a disease? Not a disease? Is it inadequate intake?”

The definition of optimal 25-D is also a matter of debate, he continued. “What’s the upper level? What does pharmacological treatment mean with respect to long-term outcomes. What is the tolerable upper limit? What is the potentially toxic limit?”

A lack of consensus also exists regarding one’s risk of vitamin D deficiency. For example, the AGS puts this risk at less than 30 ng/mL, the Endocrine Society at less than 20 ng/mL, and the Institute of Medicine at less than 12 ng/mL. “We have a lot of inconsistency in the data,” Dr. Rosen concluded. “There’s not unanimity in recommendations, even among so-called experts.”

During the same session, Dr. Peter Millard presented findings from a national analysis of vitamin D level testing in adult patients conducted from January 2013 to September 2014. The sample, drawn from Athenahealth integrated electronic health records (EHRs), included more than 6,000 internists and family physicians and 2,000 nonphysician clinicians, translating into an estimated 900,000 patient encounters per month. During that time period 4%-5% of all adult patient encounters were associated with a vitamin D test ordered.

“Curiously, the Sunbelt states of Arizona and Nevada have a high testing rate, in the 8.5%-10.7% range,” said Dr. Millard, a family physician who practices at Seaport Community Health Center in Belfast, Me. “Perhaps it’s because of snowbirds coming down from Canada to get tested. I don’t know. There are certainly lots of retirees in those two states. There are also high levels of testing in Illinois, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Delaware. I don’t have a hypothesis as to why there are variations, but that’s about 10% of all encounters associated with a vitamin D test in those states, which seems like quite a high number.”

The greatest proportion of tests occurred in patients over the age of 65 (39%) years, and about 70% of all vitamin D tests were conducted in females.

Fewer than 0.1% of tests were associated with a diagnosis of osteoporosis. The most common diagnoses associated with ordering of a vitamin D test were depression and falls. “This was particularly true in the elderly group, where falls became much more important, and depression slightly less,” Dr. Millard said. He noted that the EHR findings “don’t answer many questions but clearly the cost for [vitamin D] testing itself is significant. The amount of time my colleagues are spending doing tests and interpreting tests for patients [and] deciding what to do about those results is very considerable. In the long run, the research to resolve these issues may not be anywhere near as expensive as continuing to do what we’re doing now.”

Dr. Rosen and Dr. Millard reporting having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

If you’re stumped about what to tell patients who ask you if they should be adding supplemental vitamin D to their diet, you’re not alone.

Speaker after speaker at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health acknowledged that there is general disagreement among well-respected scientists and medical organizations not only about recommended intakes, but about whether supplementation of vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) has any impact on ailments ranging from depression and nonspecific pain to hypertension and fall prevention.

“Most people agree that at least in high-risk individuals with osteoporosis, vitamin D has an impact on bone and skeletal health, but maybe not in those who are asymptomatic and in healthy individuals as a preventive tool,” said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen, director of clinical and translational research and a senior scientist at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, Me. “There seems to be growing evidence that in high-risk individuals, or in those who repeatedly fall, vitamin D may have an impact, particularly in those with very-low levels of 25-D.”

Other relationships lack conclusive randomized control data, although there are strong observational data for vitamin D’s role in preventing type 2 diabetes. Dr. Rosen is one of the investigators in a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases–funded clinical trial known as D2D: a study of 4,000 IU of vitamin D vs. placebo in high-risk individuals with obesity and prediabetes. The primary outcome is time to onset of type 2 diabetes. “Currently, that [trial is] in its second year and is about 30% recruited,” said Dr. Rosen, who is also a member of the FDA Advisory Panel on Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs. “One of the biggest obstacles to recruitment has been the constant use of vitamin D by people being screened. [They say] ‘Why should I go into a clinical trial when I’m taking vitamin D, and my doctor tells me that it will prevent diabetes?’”

The potential benefit of vitamin D intake on reducing the risk for developing cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke is being investigated in the NIH-funded VITAL trial. Clinicians involved in this project have enrolled more than 28,000 men and women with no prior history of these illnesses, investigating the impact of taking vitamin D3 supplements (2,000 IU/day) or omega 3 fatty acids (1 G/day).

In the meantime, current vitamin D guidance and conclusions differ among leading medical organizations. For example, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends a daily dose of 4,000 IU for fall prevention in elderly individuals. This differs from the daily dose for adults recommended by the Endocrine Society (1,500-2,000 IU), Institute of Medicine (an average requirement of 400 IU and 600-800 IU meeting the greatest need), the United States Preventive Services Task Force (600-800 IU as a fall-prevention strategy), the Standing Committee of European Doctors (600-800 IU), and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (400-1,000 IU). “How do we reconcile vitamin D intake with vitamin D levels?” asked Dr. Rosen, who is also a professor of medicine at Tufts University. “This is one of the hallmarks of the questions or problems we have, or the lack of consistency of data. We know that intakes do not reflect serum 25-D levels to a great extent.”

In addition, the terminology for serum 25-D is not clear. “Is it a deficiency? Is it a disease? What does that mean?” he asked. “More importantly, we don’t really understand what vitamin D insufficiency is. Is it a disease? Not a disease? Is it inadequate intake?”

The definition of optimal 25-D is also a matter of debate, he continued. “What’s the upper level? What does pharmacological treatment mean with respect to long-term outcomes. What is the tolerable upper limit? What is the potentially toxic limit?”

A lack of consensus also exists regarding one’s risk of vitamin D deficiency. For example, the AGS puts this risk at less than 30 ng/mL, the Endocrine Society at less than 20 ng/mL, and the Institute of Medicine at less than 12 ng/mL. “We have a lot of inconsistency in the data,” Dr. Rosen concluded. “There’s not unanimity in recommendations, even among so-called experts.”

During the same session, Dr. Peter Millard presented findings from a national analysis of vitamin D level testing in adult patients conducted from January 2013 to September 2014. The sample, drawn from Athenahealth integrated electronic health records (EHRs), included more than 6,000 internists and family physicians and 2,000 nonphysician clinicians, translating into an estimated 900,000 patient encounters per month. During that time period 4%-5% of all adult patient encounters were associated with a vitamin D test ordered.

“Curiously, the Sunbelt states of Arizona and Nevada have a high testing rate, in the 8.5%-10.7% range,” said Dr. Millard, a family physician who practices at Seaport Community Health Center in Belfast, Me. “Perhaps it’s because of snowbirds coming down from Canada to get tested. I don’t know. There are certainly lots of retirees in those two states. There are also high levels of testing in Illinois, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Delaware. I don’t have a hypothesis as to why there are variations, but that’s about 10% of all encounters associated with a vitamin D test in those states, which seems like quite a high number.”

The greatest proportion of tests occurred in patients over the age of 65 (39%) years, and about 70% of all vitamin D tests were conducted in females.

Fewer than 0.1% of tests were associated with a diagnosis of osteoporosis. The most common diagnoses associated with ordering of a vitamin D test were depression and falls. “This was particularly true in the elderly group, where falls became much more important, and depression slightly less,” Dr. Millard said. He noted that the EHR findings “don’t answer many questions but clearly the cost for [vitamin D] testing itself is significant. The amount of time my colleagues are spending doing tests and interpreting tests for patients [and] deciding what to do about those results is very considerable. In the long run, the research to resolve these issues may not be anywhere near as expensive as continuing to do what we’re doing now.”

Dr. Rosen and Dr. Millard reporting having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

Men on androgen deprivation therapy not getting bisphosphonates

The rate of prescribing bisphosphonates to protect the bone health of prostate cancer patients taking androgen deprivation therapy is extremely low in Ontario, even among those at high risk of fracture, according to a research letter published online Dec. 2 in JAMA.

Canadian guidelines have recommended bisphosphonates for men at risk for bone fracture since 2002, and specifically for men taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) since 2006. However, prescribing patterns for these agents are relatively unknown, said Dr. Husayn Gulamhusein of University Health Network, Toronto, and his associates.

The investigators assessed rates of these prescriptions over time by analyzing data in an Ontario cancer registry regarding 35,487 men aged 66 years and older who initiated ADT for prostate cancer between 1995 and 2012. They found that bisphosphonate prescriptions were filled for only 0.35/100 men in the earliest years of the study period, a rate that rose to only 3.40/100 men in the final years. “Even among those with prior osteoporosis or fragility fracture, rates remained low,” the researchers said (JAMA 2014;312:2285-6).Their findings indicate “limited awareness among clinicians regarding optimal bone health management,” they added.

There was a decrease in bisphosphonate prescriptions after 2009, which “may be partly due to negative media regarding the association of bisphosphonates with rare osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures. This is appropriate for groups at low risk for fractures, but the decrease in use for high-risk patients is concerning,” Dr. Gulamhusein and his associates noted.

The rate of prescribing bisphosphonates to protect the bone health of prostate cancer patients taking androgen deprivation therapy is extremely low in Ontario, even among those at high risk of fracture, according to a research letter published online Dec. 2 in JAMA.

Canadian guidelines have recommended bisphosphonates for men at risk for bone fracture since 2002, and specifically for men taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) since 2006. However, prescribing patterns for these agents are relatively unknown, said Dr. Husayn Gulamhusein of University Health Network, Toronto, and his associates.

The investigators assessed rates of these prescriptions over time by analyzing data in an Ontario cancer registry regarding 35,487 men aged 66 years and older who initiated ADT for prostate cancer between 1995 and 2012. They found that bisphosphonate prescriptions were filled for only 0.35/100 men in the earliest years of the study period, a rate that rose to only 3.40/100 men in the final years. “Even among those with prior osteoporosis or fragility fracture, rates remained low,” the researchers said (JAMA 2014;312:2285-6).Their findings indicate “limited awareness among clinicians regarding optimal bone health management,” they added.

There was a decrease in bisphosphonate prescriptions after 2009, which “may be partly due to negative media regarding the association of bisphosphonates with rare osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures. This is appropriate for groups at low risk for fractures, but the decrease in use for high-risk patients is concerning,” Dr. Gulamhusein and his associates noted.

The rate of prescribing bisphosphonates to protect the bone health of prostate cancer patients taking androgen deprivation therapy is extremely low in Ontario, even among those at high risk of fracture, according to a research letter published online Dec. 2 in JAMA.

Canadian guidelines have recommended bisphosphonates for men at risk for bone fracture since 2002, and specifically for men taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) since 2006. However, prescribing patterns for these agents are relatively unknown, said Dr. Husayn Gulamhusein of University Health Network, Toronto, and his associates.

The investigators assessed rates of these prescriptions over time by analyzing data in an Ontario cancer registry regarding 35,487 men aged 66 years and older who initiated ADT for prostate cancer between 1995 and 2012. They found that bisphosphonate prescriptions were filled for only 0.35/100 men in the earliest years of the study period, a rate that rose to only 3.40/100 men in the final years. “Even among those with prior osteoporosis or fragility fracture, rates remained low,” the researchers said (JAMA 2014;312:2285-6).Their findings indicate “limited awareness among clinicians regarding optimal bone health management,” they added.

There was a decrease in bisphosphonate prescriptions after 2009, which “may be partly due to negative media regarding the association of bisphosphonates with rare osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures. This is appropriate for groups at low risk for fractures, but the decrease in use for high-risk patients is concerning,” Dr. Gulamhusein and his associates noted.

Key clinical point: Men taking androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer aren’t being prescribed bisphosphonates to protect their bone health.

Major finding: Bisphosphonate prescriptions were filled for only 0.35/100 men in the earliest years of the study period, a rate that rose to only 3.40/100 men in the final years.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 35,487 prostate cancer patients in Ontario taking androgen deprivation therapy during a 17-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported in part by Toronto General Hospital, the Toronto Western Hospital Research Foundation, the Canadian Cancer Society, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Gulamhusein reported having no financial disclosures; one of his associates reported receiving honoraria from Merck.

Statins don’t cut fracture risk

Daily rosuvastatin did not decrease fracture risk in a large international clinical trial involving older men and women who had elevated CRP levels, according to a report published online Dec. 1 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Statins are thought to stimulate bone formation and increase bone mineral density, suggesting that they may exert clinical benefits beyond cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. Several observational studies have reported that statin users show a decreased risk of osteoporotic fractures, compared with nonusers. To examine this possible benefit, the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) trial enrolled 17,802 men older than 50 years and women older than 60 years to receive either rosuvastatin or matching placebo and be followed for up to 5 years (median follow-up, 2 years) for both CVD and fracture events. The study was conducted at 1,315 medical centers in 26 countries, said Dr. Jessica M. Peña of the division of cardiology, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

A total of 431 participants sustained fractures: 221 in the rosuvastatin group and 210 in the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The corresponding rate of fracture was 1.20 per 100 person-years with the statin and 1.14 per 100 person-years with placebo, also a nonsignificant difference. The lack of protection associated with the active drug was consistent between men and women, across all fracture sites, and regardless of the participants’ fracture history. It also persisted through several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Dec. 1 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6388]).

“Our study does not support the use of statins in doses used for cardiovascular disease prevention to reduce the risk of fracture,” the researchers noted.

Daily rosuvastatin did not decrease fracture risk in a large international clinical trial involving older men and women who had elevated CRP levels, according to a report published online Dec. 1 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Statins are thought to stimulate bone formation and increase bone mineral density, suggesting that they may exert clinical benefits beyond cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. Several observational studies have reported that statin users show a decreased risk of osteoporotic fractures, compared with nonusers. To examine this possible benefit, the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) trial enrolled 17,802 men older than 50 years and women older than 60 years to receive either rosuvastatin or matching placebo and be followed for up to 5 years (median follow-up, 2 years) for both CVD and fracture events. The study was conducted at 1,315 medical centers in 26 countries, said Dr. Jessica M. Peña of the division of cardiology, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

A total of 431 participants sustained fractures: 221 in the rosuvastatin group and 210 in the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The corresponding rate of fracture was 1.20 per 100 person-years with the statin and 1.14 per 100 person-years with placebo, also a nonsignificant difference. The lack of protection associated with the active drug was consistent between men and women, across all fracture sites, and regardless of the participants’ fracture history. It also persisted through several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Dec. 1 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6388]).

“Our study does not support the use of statins in doses used for cardiovascular disease prevention to reduce the risk of fracture,” the researchers noted.

Daily rosuvastatin did not decrease fracture risk in a large international clinical trial involving older men and women who had elevated CRP levels, according to a report published online Dec. 1 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Statins are thought to stimulate bone formation and increase bone mineral density, suggesting that they may exert clinical benefits beyond cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. Several observational studies have reported that statin users show a decreased risk of osteoporotic fractures, compared with nonusers. To examine this possible benefit, the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) trial enrolled 17,802 men older than 50 years and women older than 60 years to receive either rosuvastatin or matching placebo and be followed for up to 5 years (median follow-up, 2 years) for both CVD and fracture events. The study was conducted at 1,315 medical centers in 26 countries, said Dr. Jessica M. Peña of the division of cardiology, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

A total of 431 participants sustained fractures: 221 in the rosuvastatin group and 210 in the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The corresponding rate of fracture was 1.20 per 100 person-years with the statin and 1.14 per 100 person-years with placebo, also a nonsignificant difference. The lack of protection associated with the active drug was consistent between men and women, across all fracture sites, and regardless of the participants’ fracture history. It also persisted through several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Dec. 1 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6388]).

“Our study does not support the use of statins in doses used for cardiovascular disease prevention to reduce the risk of fracture,” the researchers noted.

Key clinical point: Rosuvastatin didn’t lower the risk of bone fracture, compared with placebo.

Major finding: 221 participants given rosuvastatin and 210 given placebo sustained fractures, a nonsignificant difference.

Data source: An international randomized double-blind trial in which 17,802 older adults with elevated CRP received either rosuvastatin or placebo and were followed for a median of 2 years.

Disclosures: The JUPITER trial was supported by AstraZeneca, and Dr. Pena was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. She reported having no financial disclosures; her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

USPSTF: Not enough evidence for vitamin D screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against screening and treating asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the evidence regarding the benefits and harms is insufficient.

Major finding: Testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly, with one national survey showing the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reporting that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year.

Data source: A detailed review of the evidence and an expert consensus regarding screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency to prevent fractures, cancer, CVD, and other adverse outcomes.

Disclosures: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to improve Americans’ health by making recommendations concerning preventive services such as screenings and medications. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Repeat BMD screening not helpful for women under 65

Postmenopausal women without osteoporosis on their first bone mineral density test are unlikely to fracture before age 65, and are therefore unlikely to benefit from regular or repeated screening before that age, according to an analysis of results from a large cohort study.

“Our data can help inform a BMD testing interval for postmenopausal women who are screened before age 65 years. Using the more conservative time estimates for major osteoporotic fracture, clinicians might allow women aged 50 to 54 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test to wait 10 years for their next test. Similarly, women aged 60 to 64 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test might wait until after age 65 years for their next test,” Dr. Margaret Lee Gourlay of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Gourlay and her coinvestigators on the larger Women’s Health Initiative cohort study looked at data from 4,068 postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 64 years. None of the women had prior hip or vertebral fractures or received antifracture treatment; they underwent baseline bone mineral density testing between 1993 and 2005. Fracture follow-up continued through 2012 (Menopause 2014 [doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000356]).

Among women with a normal BMD on first screening, the estimated time for 1% of those aged 50-54 years to have a hip or clinical vertebral fracture was 12.8 years. Among women aged 60-64 years, the time to fracture was 7.6 years, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues found.

For the 8.5% of women in the cohort (all ages) with osteoporosis at baseline (n = 344), the age-adjusted time to hip or vertebral fracture was only 3 years.

Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues also estimated times to major osteoporotic fracture for 3% of the cohort, finding that it took 11.5 years for women aged 50-54 years to sustain a hip, clinical vertebral, proximal humerus, or wrist fracture, compared with 8.6 years for women who were 60-64 years at baseline. For women who had osteoporosis at baseline, the age-adjusted time for 3% to have an osteoporotic fracture was 2.5 years.

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of the study the fact that time estimates were based only on transitions to major fracture; that the full benefits and risks of screening, including cost-effectiveness, were not analyzed; and that the study was not powered to determine fracture risk in subgroups defined by individual risk factors.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that deferred repeat screening can be safe for postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older with normal BMD results at baseline, Dr. Gourlay and her coauthors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One of Dr. Gourlay’s coauthors is a consultant for MSD, and another reported receiving recent funding from Bone Ultrasound Finland.

This post hoc analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative cohort pursues the question of how frequently we should repeat BMD assessment on women under age 65 with normal baseline BMD. The study offers meaningful insight into how minuscule the fracture and osteoporosis risks are for women younger than 65 who have normal BMD at baseline. The younger cohort in this large study did not fracture or develop osteoporosis under surveillance to any significant extent.

While guidelines advise that women 65 and older be screened, as should younger postmenopausal women with risk factors, in clinical practice this often means that younger postmenopausal women with normal baseline BMD will enter into “autopilot” and undergo testing every 2 years. For young postmenopausal women with healthy BMD, we don’t need to fall into this default of biannual assessment. Clinicians could consider safely deferring a follow-up BMD test for young postmenopausal women with documented normal BMD for a few years, and for some even until age 65.

Nonetheless, clinicians should be mindful that this observational study was carried out in an asymptomatic group of women, and that the clinical picture should always guide the decision-making process on when and how often to screen.

Importantly, this study does not provide us any guidance regarding a young postmenopausal patient who has had a change in health status, such as a newly diagnosed autoimmune disease necessitating treatment with oral steroids, or after discontinuation of systemic menopausal hormone therapy, for whom repeating BMD assessment within 2 years or even 1 year of the initial study can be clinically justified despite evidence of normal BMD on her baseline scan.

Lubna Pal, M.D., is an associate director of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences as well as director of the Menopause Program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

This post hoc analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative cohort pursues the question of how frequently we should repeat BMD assessment on women under age 65 with normal baseline BMD. The study offers meaningful insight into how minuscule the fracture and osteoporosis risks are for women younger than 65 who have normal BMD at baseline. The younger cohort in this large study did not fracture or develop osteoporosis under surveillance to any significant extent.

While guidelines advise that women 65 and older be screened, as should younger postmenopausal women with risk factors, in clinical practice this often means that younger postmenopausal women with normal baseline BMD will enter into “autopilot” and undergo testing every 2 years. For young postmenopausal women with healthy BMD, we don’t need to fall into this default of biannual assessment. Clinicians could consider safely deferring a follow-up BMD test for young postmenopausal women with documented normal BMD for a few years, and for some even until age 65.

Nonetheless, clinicians should be mindful that this observational study was carried out in an asymptomatic group of women, and that the clinical picture should always guide the decision-making process on when and how often to screen.

Importantly, this study does not provide us any guidance regarding a young postmenopausal patient who has had a change in health status, such as a newly diagnosed autoimmune disease necessitating treatment with oral steroids, or after discontinuation of systemic menopausal hormone therapy, for whom repeating BMD assessment within 2 years or even 1 year of the initial study can be clinically justified despite evidence of normal BMD on her baseline scan.

Lubna Pal, M.D., is an associate director of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences as well as director of the Menopause Program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

This post hoc analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative cohort pursues the question of how frequently we should repeat BMD assessment on women under age 65 with normal baseline BMD. The study offers meaningful insight into how minuscule the fracture and osteoporosis risks are for women younger than 65 who have normal BMD at baseline. The younger cohort in this large study did not fracture or develop osteoporosis under surveillance to any significant extent.

While guidelines advise that women 65 and older be screened, as should younger postmenopausal women with risk factors, in clinical practice this often means that younger postmenopausal women with normal baseline BMD will enter into “autopilot” and undergo testing every 2 years. For young postmenopausal women with healthy BMD, we don’t need to fall into this default of biannual assessment. Clinicians could consider safely deferring a follow-up BMD test for young postmenopausal women with documented normal BMD for a few years, and for some even until age 65.

Nonetheless, clinicians should be mindful that this observational study was carried out in an asymptomatic group of women, and that the clinical picture should always guide the decision-making process on when and how often to screen.

Importantly, this study does not provide us any guidance regarding a young postmenopausal patient who has had a change in health status, such as a newly diagnosed autoimmune disease necessitating treatment with oral steroids, or after discontinuation of systemic menopausal hormone therapy, for whom repeating BMD assessment within 2 years or even 1 year of the initial study can be clinically justified despite evidence of normal BMD on her baseline scan.

Lubna Pal, M.D., is an associate director of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences as well as director of the Menopause Program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Postmenopausal women without osteoporosis on their first bone mineral density test are unlikely to fracture before age 65, and are therefore unlikely to benefit from regular or repeated screening before that age, according to an analysis of results from a large cohort study.

“Our data can help inform a BMD testing interval for postmenopausal women who are screened before age 65 years. Using the more conservative time estimates for major osteoporotic fracture, clinicians might allow women aged 50 to 54 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test to wait 10 years for their next test. Similarly, women aged 60 to 64 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test might wait until after age 65 years for their next test,” Dr. Margaret Lee Gourlay of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Gourlay and her coinvestigators on the larger Women’s Health Initiative cohort study looked at data from 4,068 postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 64 years. None of the women had prior hip or vertebral fractures or received antifracture treatment; they underwent baseline bone mineral density testing between 1993 and 2005. Fracture follow-up continued through 2012 (Menopause 2014 [doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000356]).

Among women with a normal BMD on first screening, the estimated time for 1% of those aged 50-54 years to have a hip or clinical vertebral fracture was 12.8 years. Among women aged 60-64 years, the time to fracture was 7.6 years, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues found.

For the 8.5% of women in the cohort (all ages) with osteoporosis at baseline (n = 344), the age-adjusted time to hip or vertebral fracture was only 3 years.

Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues also estimated times to major osteoporotic fracture for 3% of the cohort, finding that it took 11.5 years for women aged 50-54 years to sustain a hip, clinical vertebral, proximal humerus, or wrist fracture, compared with 8.6 years for women who were 60-64 years at baseline. For women who had osteoporosis at baseline, the age-adjusted time for 3% to have an osteoporotic fracture was 2.5 years.

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of the study the fact that time estimates were based only on transitions to major fracture; that the full benefits and risks of screening, including cost-effectiveness, were not analyzed; and that the study was not powered to determine fracture risk in subgroups defined by individual risk factors.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that deferred repeat screening can be safe for postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older with normal BMD results at baseline, Dr. Gourlay and her coauthors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One of Dr. Gourlay’s coauthors is a consultant for MSD, and another reported receiving recent funding from Bone Ultrasound Finland.

Postmenopausal women without osteoporosis on their first bone mineral density test are unlikely to fracture before age 65, and are therefore unlikely to benefit from regular or repeated screening before that age, according to an analysis of results from a large cohort study.

“Our data can help inform a BMD testing interval for postmenopausal women who are screened before age 65 years. Using the more conservative time estimates for major osteoporotic fracture, clinicians might allow women aged 50 to 54 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test to wait 10 years for their next test. Similarly, women aged 60 to 64 years without osteoporosis on their first BMD test might wait until after age 65 years for their next test,” Dr. Margaret Lee Gourlay of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Gourlay and her coinvestigators on the larger Women’s Health Initiative cohort study looked at data from 4,068 postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 64 years. None of the women had prior hip or vertebral fractures or received antifracture treatment; they underwent baseline bone mineral density testing between 1993 and 2005. Fracture follow-up continued through 2012 (Menopause 2014 [doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000356]).

Among women with a normal BMD on first screening, the estimated time for 1% of those aged 50-54 years to have a hip or clinical vertebral fracture was 12.8 years. Among women aged 60-64 years, the time to fracture was 7.6 years, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues found.

For the 8.5% of women in the cohort (all ages) with osteoporosis at baseline (n = 344), the age-adjusted time to hip or vertebral fracture was only 3 years.

Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues also estimated times to major osteoporotic fracture for 3% of the cohort, finding that it took 11.5 years for women aged 50-54 years to sustain a hip, clinical vertebral, proximal humerus, or wrist fracture, compared with 8.6 years for women who were 60-64 years at baseline. For women who had osteoporosis at baseline, the age-adjusted time for 3% to have an osteoporotic fracture was 2.5 years.

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of the study the fact that time estimates were based only on transitions to major fracture; that the full benefits and risks of screening, including cost-effectiveness, were not analyzed; and that the study was not powered to determine fracture risk in subgroups defined by individual risk factors.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that deferred repeat screening can be safe for postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older with normal BMD results at baseline, Dr. Gourlay and her coauthors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One of Dr. Gourlay’s coauthors is a consultant for MSD, and another reported receiving recent funding from Bone Ultrasound Finland.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Key clinical point: Women under age 65 without risk factors whose first BMD screen is normal are not likely to benefit from repeat screening.

Major finding: Time to hip or vertebral fracture for 1% of women aged 50-54 years with normal BMD at baseline was 12.8 years, and 7.6 years for women aged 60-64 years, compared with 3 years for women aged 50-64 years with baseline osteoporosis.

Data source: An observational cohort of 4,068 women recruited as part of a larger trial cohort of postmenopausal women (n = 161,808) in the Women’s Health Initiative study.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One of Dr. Gourlay’s coauthors is a consultant for MSD, and another reported receiving recent funding from Bone Ultrasound Finland.

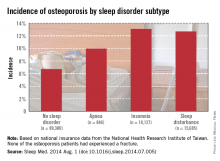

Link found between sleep disorders and osteoporosis risk

Patients with sleep disorders are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than are those without sleep disorders, according to Dr. Chia-Ming Yen and her associates.

Patients diagnosed with sleep apnea between 1998 and 2001 had an osteoporosis incidence of nearly 10% at the end of 2010, while those without sleep disorders had incidence of 6.7%. Patients with insomnia developed osteoporosis at a rate of 13.1%, and patients with other sleep disturbances had an incidence of 12.7%, Dr. Yen of the National Formosa University in Taiwan, and her associates reported (Sleep Med. 2014 Aug. 1 [doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.005]).

Women and the elderly were particularly likely to develop osteoporosis if a sleep disorder was present. Of patients aged 64 years and older who were diagnosed with osteoporosis, 36.2% also had sleep apnea, and 31.9% had another sleep disorder. Incidences of osteoporosis in women in all cases were three to five times higher than those in men, and patients with multiple comorbidities also had an increased risk of osteoporosis, the investigators reported.

The study used data collected from 1996-2010 by the National Health Research Institute of Taiwan.

Patients with sleep disorders are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than are those without sleep disorders, according to Dr. Chia-Ming Yen and her associates.

Patients diagnosed with sleep apnea between 1998 and 2001 had an osteoporosis incidence of nearly 10% at the end of 2010, while those without sleep disorders had incidence of 6.7%. Patients with insomnia developed osteoporosis at a rate of 13.1%, and patients with other sleep disturbances had an incidence of 12.7%, Dr. Yen of the National Formosa University in Taiwan, and her associates reported (Sleep Med. 2014 Aug. 1 [doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.005]).

Women and the elderly were particularly likely to develop osteoporosis if a sleep disorder was present. Of patients aged 64 years and older who were diagnosed with osteoporosis, 36.2% also had sleep apnea, and 31.9% had another sleep disorder. Incidences of osteoporosis in women in all cases were three to five times higher than those in men, and patients with multiple comorbidities also had an increased risk of osteoporosis, the investigators reported.

The study used data collected from 1996-2010 by the National Health Research Institute of Taiwan.

Patients with sleep disorders are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than are those without sleep disorders, according to Dr. Chia-Ming Yen and her associates.

Patients diagnosed with sleep apnea between 1998 and 2001 had an osteoporosis incidence of nearly 10% at the end of 2010, while those without sleep disorders had incidence of 6.7%. Patients with insomnia developed osteoporosis at a rate of 13.1%, and patients with other sleep disturbances had an incidence of 12.7%, Dr. Yen of the National Formosa University in Taiwan, and her associates reported (Sleep Med. 2014 Aug. 1 [doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.005]).

Women and the elderly were particularly likely to develop osteoporosis if a sleep disorder was present. Of patients aged 64 years and older who were diagnosed with osteoporosis, 36.2% also had sleep apnea, and 31.9% had another sleep disorder. Incidences of osteoporosis in women in all cases were three to five times higher than those in men, and patients with multiple comorbidities also had an increased risk of osteoporosis, the investigators reported.

The study used data collected from 1996-2010 by the National Health Research Institute of Taiwan.

Vitamin D deficiency associated with Alzheimer’s

Our relationship with vitamins and supplements may be approach-avoidance. On one hand, if they are beneficial and patients are motivated to take them, we do not complain. This is likely a marker of motivated patient who may heed other health promotional advice that we proffer. On the other hand, it is difficult to keep up with the massive amount of good and bad literature about them. Patients can challenge us on our medical knowledge, pinging our opinions about the latest findings tweeted out while we struggle to keep up with all the wheelchair forms.

Vitamins are clearly not consistently beneficial. B vitamins may increase lung cancer risk in smokers. Vitamin D, however, seems to have some of the greatest “staying power” in the clinical realm and has a good reputation as far as vitamins go. Vitamin D is probably good for the heart, but how about the head? Could low D cause dementia? If so, how?

Previous studies of the relationship between vitamin D and dementia have not shown consistent results. Thomas Littlejohns, M.Sc., and colleagues have published a fantastic piece of work (Neurology 2014 Aug. 6 [doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000755]) that sheds some light. They evaluated a prospective cohort of 1,658 elderly ambulatory adults with no history of dementia, CVD, or stroke who had baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations at baseline. Severely low levels of 25(OH)D and deficiency (≥25 to <50 nmol/L) were associated with a significantly increased risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia.

Several hypotheses exist as to why vitamin D helps the brain. Vitamin D may attenuate amyloid-induced cytotoxicity and neural apoptosis. It also may reduce the risk of strokes by promoting healthy cerebral vasculature.

The Institute of Medicine recommends a serum concentration of 25(OH)D at 50 nmol/L. This study would suggest that sufficiency to this level is neuroprotective. The next step is to see if supplementation can modify baseline risk, but many of my patients may wait for these data to come out before starting their vitamin D supplements.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

Our relationship with vitamins and supplements may be approach-avoidance. On one hand, if they are beneficial and patients are motivated to take them, we do not complain. This is likely a marker of motivated patient who may heed other health promotional advice that we proffer. On the other hand, it is difficult to keep up with the massive amount of good and bad literature about them. Patients can challenge us on our medical knowledge, pinging our opinions about the latest findings tweeted out while we struggle to keep up with all the wheelchair forms.

Vitamins are clearly not consistently beneficial. B vitamins may increase lung cancer risk in smokers. Vitamin D, however, seems to have some of the greatest “staying power” in the clinical realm and has a good reputation as far as vitamins go. Vitamin D is probably good for the heart, but how about the head? Could low D cause dementia? If so, how?

Previous studies of the relationship between vitamin D and dementia have not shown consistent results. Thomas Littlejohns, M.Sc., and colleagues have published a fantastic piece of work (Neurology 2014 Aug. 6 [doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000755]) that sheds some light. They evaluated a prospective cohort of 1,658 elderly ambulatory adults with no history of dementia, CVD, or stroke who had baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations at baseline. Severely low levels of 25(OH)D and deficiency (≥25 to <50 nmol/L) were associated with a significantly increased risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia.

Several hypotheses exist as to why vitamin D helps the brain. Vitamin D may attenuate amyloid-induced cytotoxicity and neural apoptosis. It also may reduce the risk of strokes by promoting healthy cerebral vasculature.

The Institute of Medicine recommends a serum concentration of 25(OH)D at 50 nmol/L. This study would suggest that sufficiency to this level is neuroprotective. The next step is to see if supplementation can modify baseline risk, but many of my patients may wait for these data to come out before starting their vitamin D supplements.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

Our relationship with vitamins and supplements may be approach-avoidance. On one hand, if they are beneficial and patients are motivated to take them, we do not complain. This is likely a marker of motivated patient who may heed other health promotional advice that we proffer. On the other hand, it is difficult to keep up with the massive amount of good and bad literature about them. Patients can challenge us on our medical knowledge, pinging our opinions about the latest findings tweeted out while we struggle to keep up with all the wheelchair forms.

Vitamins are clearly not consistently beneficial. B vitamins may increase lung cancer risk in smokers. Vitamin D, however, seems to have some of the greatest “staying power” in the clinical realm and has a good reputation as far as vitamins go. Vitamin D is probably good for the heart, but how about the head? Could low D cause dementia? If so, how?

Previous studies of the relationship between vitamin D and dementia have not shown consistent results. Thomas Littlejohns, M.Sc., and colleagues have published a fantastic piece of work (Neurology 2014 Aug. 6 [doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000755]) that sheds some light. They evaluated a prospective cohort of 1,658 elderly ambulatory adults with no history of dementia, CVD, or stroke who had baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations at baseline. Severely low levels of 25(OH)D and deficiency (≥25 to <50 nmol/L) were associated with a significantly increased risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia.

Several hypotheses exist as to why vitamin D helps the brain. Vitamin D may attenuate amyloid-induced cytotoxicity and neural apoptosis. It also may reduce the risk of strokes by promoting healthy cerebral vasculature.

The Institute of Medicine recommends a serum concentration of 25(OH)D at 50 nmol/L. This study would suggest that sufficiency to this level is neuroprotective. The next step is to see if supplementation can modify baseline risk, but many of my patients may wait for these data to come out before starting their vitamin D supplements.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

Biomarker predicts bone loss in premenopausal breast cancer patients

CHICAGO – A premenopausal breast cancer patient’s follicle-stimulating hormone level upon completion of chemotherapy predicts her risk of bone loss during the ensuing 12 months, Dr. Laila S. Tabatabai reported at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

“This may have significant implications for preserving bone health in premenopausal women with breast cancer. Appropriate use of FSH as a marker for premature ovarian failure and as a predictor of bone loss after breast cancer treatment may allow for the timely implementation of preventive measures to reduce fracture risk,” said Dr. Tabatabai of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

She presented a secondary analysis from the Exercise for Bone Health: Young Breast Cancer Survivors Study, in which 206 women who were under age 55 and had completed adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer were randomized to a 12-month structured exercise program conducted through the YMCA or to a control group that received a monthly health newsletter.

Investigators measured baseline levels of FSH, bone turnover markers, calciotropic hormones, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. At 1 year follow-up, only baseline FSH level was significantly related to bone loss.

After adjustment for age, ethnicity, baseline bone mineral density, and assignment to the exercise or control arm, multivariate analysis showed that only women in the lowest tertile for baseline FSH – that is, a level of 21.1 IU/L or less – maintained their baseline bone mineral density at the lumbar spine. They averaged a 0.007% increase over 12 months. In contrast, women in the middle tertile, with a baseline FSH of 21.2-61.6 IU/L, had a mean 0.96% decrease in bone density, and those in the highest tertile, with an FSH of 61.7-124.6 IU/L, averaged a 2.2% bone loss.