User login

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia: A Single Disease Entity?

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) have overlapping neurologic symptoms — particularly profound fatigue. The similarity between these two conditions has led to the question of whether they are indeed distinct central nervous system (CNS) entities, or whether they exist along a spectrum and are actually two different manifestations of the same disease process.

A new study utilized a novel methodology — unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics — to investigate this question by analyzing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a group of patients with ME/CFS and another group of patients diagnosed with both ME/CFS and FM.

Close to 2,100 proteins were identified, of which nearly 1,800 were common to both conditions.

“ME/CFS and fibromyalgia do not appear to be distinct entities, with respect to their cerebrospinal fluid proteins,” lead author Steven Schutzer, MD, professor of medicine, Rutgers New Jersey School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“Work is underway to solve the multiple mysteries of ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and other neurologic-associated diseases,” he continued. “We have further affirmed that we have a precise objective discovery tool in our hands. Collectively studying multiple diseases brings clarity to each individual disease.”

The study was published in the December 2023 issue of Annals of Medicine.

Cutting-Edge Technology

“ME/CFS is characterized by disabling fatigue, and FM is an illness characterized by body-wide pain,” Dr. Schutzer said. These “medically unexplained” illnesses often coexist by current definitions, and the overlap between them has suggested that they may be part of the “same illness spectrum.”

But co-investigator Benjamin Natelson, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Pain and Fatigue Study Center, Mount Sinai, New York, and others found in previous research that there are distinct differences between the conditions, raising the possibility that there may be different pathophysiological processes.

“The physicians and scientists on our team have had longstanding interest in studying neurologic diseases with cutting-edge tools such as mass spectrometry applied to CSF,” Dr. Schutzer said. “We have had success using this message to distinguish diseases such as ME/CFS from post-treatment Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, and healthy normal people.”

Dr. Schutzer explained that Dr. Natelson had acquired CSF samples from “well-characterized [ME/CFS] patients and controls.”

Since the cause of ME/CFS is “unknown,” it seemed “ripe to investigate it further with the discovery tool of mass spectrometry” by harnessing the “most advanced equipment in the country at the pacific Northwest National Laboratory, which is part of the US Department of Energy.”

Dr. Schutzer noted that it was the “merger of different clinical and laboratory expertise” that enabled them to address whether ME/CFS and FM are two distinct disease processes.

The choice of analyzing CSF is that it’s the fluid closest to the brain, he added. “A lot of people have studied ME/CFS peripherally because they don’t have access to spinal fluid or it’s easier to look peripherally in the blood, but that doesn’t mean that the blood is where the real ‘action’ is occurring.”

The researchers compared the CSF of 15 patients with ME/CFS only to 15 patients with ME/CFS+FM using mass spectrometry-based proteomics, which they had employed in previous research to see whether ME/CFS was distinct from persistent neurologic Lyme disease syndrome.

This technology has become the “method of choice and discovery tool to rapidly uncover protein biomarkers that can distinguish one disease from another,” the authors stated.

In particular, in unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics, the researchers do not have to know in advance what’s in a sample before studying it, Dr. Schutzer explained.

Shared Pathophysiology?

Both groups of patients were of similar age (41.3 ± 9.4 years and 40.1 ± 11.0 years, respectively), with no differences in gender or rates of current comorbid psychiatric diagnoses between the groups.

The researchers quantified a total of 2,083 proteins, including 1,789 that were specifically quantified in all of the CSF samples, regardless of the presence or absence of FM.

Several analyses (including an ANOVA analysis with adjusted P values, a Random Forest machine learning approach that looked at relative protein abundance changes between those with ME/CFS and ME/CFS+FM, and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses) did not find distinguishing differences between the groups.

the authors stated.

They noted that both conditions are “medically unexplained,” with core symptoms of pain, fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive difficulty. The fact that these two syndromes coexist so often has led to the assumption that the “similarities between them outweigh the differences,” they wrote.

They pointed to some differences between the conditions, including an increase in substance P in the CSF of FM patients, but not in ME/CFS patients reported by others. There are also some immunological, physiological and genetic differences.

But if the conclusion that the two illnesses may share a similar pathophysiological basis is supported by other research that includes FM-only patients as comparators to those with ME/CFS, “this would support the notion that the two illnesses fall along a common illness spectrum and may be approached as a single entity — with implications for both diagnosis and the development of new treatment approaches,” they concluded.

‘Noncontributory’ Findings

Commenting on the research, Robert G. Lahita, MD, PhD, director of the Institute for Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases, St. Joseph Health, Wayne, New Jersey, stated that he does not regard these diseases as neurologic but rather as rheumatologic.

“Most neurologists don’t see these diseases, but as a rheumatologist, I see them every day,” said Dr. Lahita, professor of medicine at Hackensack (New Jersey) Meridian School of Medicine and a clinical professor of medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, New Brunswick. “ME/CFS isn’t as common in my practice, but we do deal with many post-COVID patients who are afflicted mostly with ME/CFS.”

He noted that an important reason for fatigue in FM is that patients generally don’t sleep, or their sleep is disrupted. This is different from the cause of fatigue in ME/CFS.

In addition, the small sample size and the lack of difference between males and females were both limitations of the current study, said Dr. Lahita, who was not involved in this research. “We know that FM disproportionately affects women — in my practice, for example, over 95% of the patients with FM are female — while ME/CFS affects both genders similarly.”

Using proteomics as a biomarker was also problematic, according to Dr. Lahita. “It would have been more valuable to investigate differences in cytokines, for example,” he suggested.

Ultimately, Dr. Lahita thinks that the study is “non-contributory to the field and, as complex as the analysis was, it does nothing to shed differentiate the two conditions or explain the syndromes themselves.”

He added that it would have been more valuable to compare ME/CFS not only to ME/CFS plus FM but also with FM without ME/CFS and to healthy controls, and perhaps to a group with an autoimmune condition, such as lupus or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Dr. Schutzer acknowledged that a limitation of the current study is that his team was unable analyze the CSF of patients with only FM. He and his colleagues “combed the world’s labs” for existing CSF samples of patients with FM alone but were unable to obtain any. “We see this study as a ‘stepping stone’ and hope that future studies will include patients with FM who are willing to donate CSF samples that we can use for comparison,” he said.

The authors received support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Schutzer, coauthors, and Dr. Lahita reported no relevant financial relationships.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) have overlapping neurologic symptoms — particularly profound fatigue. The similarity between these two conditions has led to the question of whether they are indeed distinct central nervous system (CNS) entities, or whether they exist along a spectrum and are actually two different manifestations of the same disease process.

A new study utilized a novel methodology — unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics — to investigate this question by analyzing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a group of patients with ME/CFS and another group of patients diagnosed with both ME/CFS and FM.

Close to 2,100 proteins were identified, of which nearly 1,800 were common to both conditions.

“ME/CFS and fibromyalgia do not appear to be distinct entities, with respect to their cerebrospinal fluid proteins,” lead author Steven Schutzer, MD, professor of medicine, Rutgers New Jersey School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“Work is underway to solve the multiple mysteries of ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and other neurologic-associated diseases,” he continued. “We have further affirmed that we have a precise objective discovery tool in our hands. Collectively studying multiple diseases brings clarity to each individual disease.”

The study was published in the December 2023 issue of Annals of Medicine.

Cutting-Edge Technology

“ME/CFS is characterized by disabling fatigue, and FM is an illness characterized by body-wide pain,” Dr. Schutzer said. These “medically unexplained” illnesses often coexist by current definitions, and the overlap between them has suggested that they may be part of the “same illness spectrum.”

But co-investigator Benjamin Natelson, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Pain and Fatigue Study Center, Mount Sinai, New York, and others found in previous research that there are distinct differences between the conditions, raising the possibility that there may be different pathophysiological processes.

“The physicians and scientists on our team have had longstanding interest in studying neurologic diseases with cutting-edge tools such as mass spectrometry applied to CSF,” Dr. Schutzer said. “We have had success using this message to distinguish diseases such as ME/CFS from post-treatment Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, and healthy normal people.”

Dr. Schutzer explained that Dr. Natelson had acquired CSF samples from “well-characterized [ME/CFS] patients and controls.”

Since the cause of ME/CFS is “unknown,” it seemed “ripe to investigate it further with the discovery tool of mass spectrometry” by harnessing the “most advanced equipment in the country at the pacific Northwest National Laboratory, which is part of the US Department of Energy.”

Dr. Schutzer noted that it was the “merger of different clinical and laboratory expertise” that enabled them to address whether ME/CFS and FM are two distinct disease processes.

The choice of analyzing CSF is that it’s the fluid closest to the brain, he added. “A lot of people have studied ME/CFS peripherally because they don’t have access to spinal fluid or it’s easier to look peripherally in the blood, but that doesn’t mean that the blood is where the real ‘action’ is occurring.”

The researchers compared the CSF of 15 patients with ME/CFS only to 15 patients with ME/CFS+FM using mass spectrometry-based proteomics, which they had employed in previous research to see whether ME/CFS was distinct from persistent neurologic Lyme disease syndrome.

This technology has become the “method of choice and discovery tool to rapidly uncover protein biomarkers that can distinguish one disease from another,” the authors stated.

In particular, in unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics, the researchers do not have to know in advance what’s in a sample before studying it, Dr. Schutzer explained.

Shared Pathophysiology?

Both groups of patients were of similar age (41.3 ± 9.4 years and 40.1 ± 11.0 years, respectively), with no differences in gender or rates of current comorbid psychiatric diagnoses between the groups.

The researchers quantified a total of 2,083 proteins, including 1,789 that were specifically quantified in all of the CSF samples, regardless of the presence or absence of FM.

Several analyses (including an ANOVA analysis with adjusted P values, a Random Forest machine learning approach that looked at relative protein abundance changes between those with ME/CFS and ME/CFS+FM, and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses) did not find distinguishing differences between the groups.

the authors stated.

They noted that both conditions are “medically unexplained,” with core symptoms of pain, fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive difficulty. The fact that these two syndromes coexist so often has led to the assumption that the “similarities between them outweigh the differences,” they wrote.

They pointed to some differences between the conditions, including an increase in substance P in the CSF of FM patients, but not in ME/CFS patients reported by others. There are also some immunological, physiological and genetic differences.

But if the conclusion that the two illnesses may share a similar pathophysiological basis is supported by other research that includes FM-only patients as comparators to those with ME/CFS, “this would support the notion that the two illnesses fall along a common illness spectrum and may be approached as a single entity — with implications for both diagnosis and the development of new treatment approaches,” they concluded.

‘Noncontributory’ Findings

Commenting on the research, Robert G. Lahita, MD, PhD, director of the Institute for Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases, St. Joseph Health, Wayne, New Jersey, stated that he does not regard these diseases as neurologic but rather as rheumatologic.

“Most neurologists don’t see these diseases, but as a rheumatologist, I see them every day,” said Dr. Lahita, professor of medicine at Hackensack (New Jersey) Meridian School of Medicine and a clinical professor of medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, New Brunswick. “ME/CFS isn’t as common in my practice, but we do deal with many post-COVID patients who are afflicted mostly with ME/CFS.”

He noted that an important reason for fatigue in FM is that patients generally don’t sleep, or their sleep is disrupted. This is different from the cause of fatigue in ME/CFS.

In addition, the small sample size and the lack of difference between males and females were both limitations of the current study, said Dr. Lahita, who was not involved in this research. “We know that FM disproportionately affects women — in my practice, for example, over 95% of the patients with FM are female — while ME/CFS affects both genders similarly.”

Using proteomics as a biomarker was also problematic, according to Dr. Lahita. “It would have been more valuable to investigate differences in cytokines, for example,” he suggested.

Ultimately, Dr. Lahita thinks that the study is “non-contributory to the field and, as complex as the analysis was, it does nothing to shed differentiate the two conditions or explain the syndromes themselves.”

He added that it would have been more valuable to compare ME/CFS not only to ME/CFS plus FM but also with FM without ME/CFS and to healthy controls, and perhaps to a group with an autoimmune condition, such as lupus or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Dr. Schutzer acknowledged that a limitation of the current study is that his team was unable analyze the CSF of patients with only FM. He and his colleagues “combed the world’s labs” for existing CSF samples of patients with FM alone but were unable to obtain any. “We see this study as a ‘stepping stone’ and hope that future studies will include patients with FM who are willing to donate CSF samples that we can use for comparison,” he said.

The authors received support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Schutzer, coauthors, and Dr. Lahita reported no relevant financial relationships.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) have overlapping neurologic symptoms — particularly profound fatigue. The similarity between these two conditions has led to the question of whether they are indeed distinct central nervous system (CNS) entities, or whether they exist along a spectrum and are actually two different manifestations of the same disease process.

A new study utilized a novel methodology — unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics — to investigate this question by analyzing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a group of patients with ME/CFS and another group of patients diagnosed with both ME/CFS and FM.

Close to 2,100 proteins were identified, of which nearly 1,800 were common to both conditions.

“ME/CFS and fibromyalgia do not appear to be distinct entities, with respect to their cerebrospinal fluid proteins,” lead author Steven Schutzer, MD, professor of medicine, Rutgers New Jersey School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“Work is underway to solve the multiple mysteries of ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and other neurologic-associated diseases,” he continued. “We have further affirmed that we have a precise objective discovery tool in our hands. Collectively studying multiple diseases brings clarity to each individual disease.”

The study was published in the December 2023 issue of Annals of Medicine.

Cutting-Edge Technology

“ME/CFS is characterized by disabling fatigue, and FM is an illness characterized by body-wide pain,” Dr. Schutzer said. These “medically unexplained” illnesses often coexist by current definitions, and the overlap between them has suggested that they may be part of the “same illness spectrum.”

But co-investigator Benjamin Natelson, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Pain and Fatigue Study Center, Mount Sinai, New York, and others found in previous research that there are distinct differences between the conditions, raising the possibility that there may be different pathophysiological processes.

“The physicians and scientists on our team have had longstanding interest in studying neurologic diseases with cutting-edge tools such as mass spectrometry applied to CSF,” Dr. Schutzer said. “We have had success using this message to distinguish diseases such as ME/CFS from post-treatment Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, and healthy normal people.”

Dr. Schutzer explained that Dr. Natelson had acquired CSF samples from “well-characterized [ME/CFS] patients and controls.”

Since the cause of ME/CFS is “unknown,” it seemed “ripe to investigate it further with the discovery tool of mass spectrometry” by harnessing the “most advanced equipment in the country at the pacific Northwest National Laboratory, which is part of the US Department of Energy.”

Dr. Schutzer noted that it was the “merger of different clinical and laboratory expertise” that enabled them to address whether ME/CFS and FM are two distinct disease processes.

The choice of analyzing CSF is that it’s the fluid closest to the brain, he added. “A lot of people have studied ME/CFS peripherally because they don’t have access to spinal fluid or it’s easier to look peripherally in the blood, but that doesn’t mean that the blood is where the real ‘action’ is occurring.”

The researchers compared the CSF of 15 patients with ME/CFS only to 15 patients with ME/CFS+FM using mass spectrometry-based proteomics, which they had employed in previous research to see whether ME/CFS was distinct from persistent neurologic Lyme disease syndrome.

This technology has become the “method of choice and discovery tool to rapidly uncover protein biomarkers that can distinguish one disease from another,” the authors stated.

In particular, in unbiased quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics, the researchers do not have to know in advance what’s in a sample before studying it, Dr. Schutzer explained.

Shared Pathophysiology?

Both groups of patients were of similar age (41.3 ± 9.4 years and 40.1 ± 11.0 years, respectively), with no differences in gender or rates of current comorbid psychiatric diagnoses between the groups.

The researchers quantified a total of 2,083 proteins, including 1,789 that were specifically quantified in all of the CSF samples, regardless of the presence or absence of FM.

Several analyses (including an ANOVA analysis with adjusted P values, a Random Forest machine learning approach that looked at relative protein abundance changes between those with ME/CFS and ME/CFS+FM, and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses) did not find distinguishing differences between the groups.

the authors stated.

They noted that both conditions are “medically unexplained,” with core symptoms of pain, fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive difficulty. The fact that these two syndromes coexist so often has led to the assumption that the “similarities between them outweigh the differences,” they wrote.

They pointed to some differences between the conditions, including an increase in substance P in the CSF of FM patients, but not in ME/CFS patients reported by others. There are also some immunological, physiological and genetic differences.

But if the conclusion that the two illnesses may share a similar pathophysiological basis is supported by other research that includes FM-only patients as comparators to those with ME/CFS, “this would support the notion that the two illnesses fall along a common illness spectrum and may be approached as a single entity — with implications for both diagnosis and the development of new treatment approaches,” they concluded.

‘Noncontributory’ Findings

Commenting on the research, Robert G. Lahita, MD, PhD, director of the Institute for Autoimmune and Rheumatic Diseases, St. Joseph Health, Wayne, New Jersey, stated that he does not regard these diseases as neurologic but rather as rheumatologic.

“Most neurologists don’t see these diseases, but as a rheumatologist, I see them every day,” said Dr. Lahita, professor of medicine at Hackensack (New Jersey) Meridian School of Medicine and a clinical professor of medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, New Brunswick. “ME/CFS isn’t as common in my practice, but we do deal with many post-COVID patients who are afflicted mostly with ME/CFS.”

He noted that an important reason for fatigue in FM is that patients generally don’t sleep, or their sleep is disrupted. This is different from the cause of fatigue in ME/CFS.

In addition, the small sample size and the lack of difference between males and females were both limitations of the current study, said Dr. Lahita, who was not involved in this research. “We know that FM disproportionately affects women — in my practice, for example, over 95% of the patients with FM are female — while ME/CFS affects both genders similarly.”

Using proteomics as a biomarker was also problematic, according to Dr. Lahita. “It would have been more valuable to investigate differences in cytokines, for example,” he suggested.

Ultimately, Dr. Lahita thinks that the study is “non-contributory to the field and, as complex as the analysis was, it does nothing to shed differentiate the two conditions or explain the syndromes themselves.”

He added that it would have been more valuable to compare ME/CFS not only to ME/CFS plus FM but also with FM without ME/CFS and to healthy controls, and perhaps to a group with an autoimmune condition, such as lupus or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Dr. Schutzer acknowledged that a limitation of the current study is that his team was unable analyze the CSF of patients with only FM. He and his colleagues “combed the world’s labs” for existing CSF samples of patients with FM alone but were unable to obtain any. “We see this study as a ‘stepping stone’ and hope that future studies will include patients with FM who are willing to donate CSF samples that we can use for comparison,” he said.

The authors received support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Schutzer, coauthors, and Dr. Lahita reported no relevant financial relationships.

‘Left in the Dark’: Prior Authorization Erodes Trust, Costs More

Mark Lewis, MD, saw the pain in his patient’s body. The man’s gastrointestinal tumor had metastasized to his bones. Even breathing had become agonizing.

It was a Friday afternoon. Dr. Lewis could see his patient would struggle to make it through the weekend without some pain relief.

When this happens, “the clock is ticking,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah. “A patient, especially one with more advanced disease, only has so much time to wait for care.”

Dr. Lewis sent in an electronic request for an opioid prescription to help ease his patient’s pain through the weekend. Once the prescription had gone through, Dr. Lewis told his patient the medication should be ready to pick up at his local pharmacy.

Dr. Lewis left work that Friday feeling a little lighter, knowing the pain medication would help his patient over the weekend.

Moments after walking into the clinic on Monday morning, Dr. Lewis received an unexpected message: “Your patient is in the hospital.”

The events of the weekend soon unfolded.

Dr. Lewis learned that when his patient went to the pharmacy to pick up his pain medication, the pharmacist told him the prescription required prior authorization.

The patient left the pharmacy empty-handed. Hours later, he was in the emergency room (ER) in extreme pain — the exact situation Dr. Lewis had been trying to avoid.

Dr. Lewis felt a sense of powerlessness in that moment.

“I had been left in the dark,” he said. The oncologist-patient relationship is predicated on trust and “that trust is eroded when I can’t give my patients the care they need,” he explained. “I can’t stand overpromising and underdelivering to them.”

Dr. Lewis had received no communication from the insurer that the prescription required prior authorization, no red flag that the request had been denied, and no notification to call the insurer.

Although physicians may need to tread carefully when prescribing opioids over the long term, “this was simply a prescription for 2-3 days of opioids for the exact patient who the drugs were developed to benefit,” Dr. Lewis said. But instead, “he ended up in ER with a pain crisis.”

Prior authorization delays like this often mean patients pay the price.

“These delays are not trivial,” Dr. Lewis said.

A recent study, presented at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium in October, found that among 3304 supportive care prescriptions requiring prior authorization, insurance companies denied 8% of requests, with final denials taking as long as 78 days. Among approved prescriptions, about 40% happened on the same day, while the remaining took anywhere from 1 to 54 days.

Denying or delaying necessary and cost-effective care, even briefly, can harm patients and lead to higher costs. A 2022 survey from the American Medical Association found that instead of reducing low-value care as insurance companies claim, prior authorization often leads to higher overall use of healthcare resources. More specifically, almost half of physicians surveyed said that prior authorization led to an ER visit or need for immediate care.

In this patient’s case, filling the opioid prescription that Friday would have cost no more than $300, possibly as little as $30. The ER visit to manage the patient’s pain crisis costs thousands.

The major issue overall, Dr. Lewis said, is the disconnect between the time spent waiting for prior authorization approvals and the necessity of these treatments. Dr. Lewis says even standard chemotherapy often requires prior authorization.

“The currency we all share is time,” Dr. Lewis said. “But it often feels like there’s very little urgency on insurance company side to approve a treatment, which places a heavy weight on patients and physicians.”

“It just shouldn’t be this hard,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com as part of the Gatekeepers of Care series on issues oncologists and people with cancer face navigating health insurance company requirements. Read more about the series here. Please email [email protected] to share experiences with prior authorization or other challenges receiving care.

Mark Lewis, MD, saw the pain in his patient’s body. The man’s gastrointestinal tumor had metastasized to his bones. Even breathing had become agonizing.

It was a Friday afternoon. Dr. Lewis could see his patient would struggle to make it through the weekend without some pain relief.

When this happens, “the clock is ticking,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah. “A patient, especially one with more advanced disease, only has so much time to wait for care.”

Dr. Lewis sent in an electronic request for an opioid prescription to help ease his patient’s pain through the weekend. Once the prescription had gone through, Dr. Lewis told his patient the medication should be ready to pick up at his local pharmacy.

Dr. Lewis left work that Friday feeling a little lighter, knowing the pain medication would help his patient over the weekend.

Moments after walking into the clinic on Monday morning, Dr. Lewis received an unexpected message: “Your patient is in the hospital.”

The events of the weekend soon unfolded.

Dr. Lewis learned that when his patient went to the pharmacy to pick up his pain medication, the pharmacist told him the prescription required prior authorization.

The patient left the pharmacy empty-handed. Hours later, he was in the emergency room (ER) in extreme pain — the exact situation Dr. Lewis had been trying to avoid.

Dr. Lewis felt a sense of powerlessness in that moment.

“I had been left in the dark,” he said. The oncologist-patient relationship is predicated on trust and “that trust is eroded when I can’t give my patients the care they need,” he explained. “I can’t stand overpromising and underdelivering to them.”

Dr. Lewis had received no communication from the insurer that the prescription required prior authorization, no red flag that the request had been denied, and no notification to call the insurer.

Although physicians may need to tread carefully when prescribing opioids over the long term, “this was simply a prescription for 2-3 days of opioids for the exact patient who the drugs were developed to benefit,” Dr. Lewis said. But instead, “he ended up in ER with a pain crisis.”

Prior authorization delays like this often mean patients pay the price.

“These delays are not trivial,” Dr. Lewis said.

A recent study, presented at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium in October, found that among 3304 supportive care prescriptions requiring prior authorization, insurance companies denied 8% of requests, with final denials taking as long as 78 days. Among approved prescriptions, about 40% happened on the same day, while the remaining took anywhere from 1 to 54 days.

Denying or delaying necessary and cost-effective care, even briefly, can harm patients and lead to higher costs. A 2022 survey from the American Medical Association found that instead of reducing low-value care as insurance companies claim, prior authorization often leads to higher overall use of healthcare resources. More specifically, almost half of physicians surveyed said that prior authorization led to an ER visit or need for immediate care.

In this patient’s case, filling the opioid prescription that Friday would have cost no more than $300, possibly as little as $30. The ER visit to manage the patient’s pain crisis costs thousands.

The major issue overall, Dr. Lewis said, is the disconnect between the time spent waiting for prior authorization approvals and the necessity of these treatments. Dr. Lewis says even standard chemotherapy often requires prior authorization.

“The currency we all share is time,” Dr. Lewis said. “But it often feels like there’s very little urgency on insurance company side to approve a treatment, which places a heavy weight on patients and physicians.”

“It just shouldn’t be this hard,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com as part of the Gatekeepers of Care series on issues oncologists and people with cancer face navigating health insurance company requirements. Read more about the series here. Please email [email protected] to share experiences with prior authorization or other challenges receiving care.

Mark Lewis, MD, saw the pain in his patient’s body. The man’s gastrointestinal tumor had metastasized to his bones. Even breathing had become agonizing.

It was a Friday afternoon. Dr. Lewis could see his patient would struggle to make it through the weekend without some pain relief.

When this happens, “the clock is ticking,” said Dr. Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology at Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah. “A patient, especially one with more advanced disease, only has so much time to wait for care.”

Dr. Lewis sent in an electronic request for an opioid prescription to help ease his patient’s pain through the weekend. Once the prescription had gone through, Dr. Lewis told his patient the medication should be ready to pick up at his local pharmacy.

Dr. Lewis left work that Friday feeling a little lighter, knowing the pain medication would help his patient over the weekend.

Moments after walking into the clinic on Monday morning, Dr. Lewis received an unexpected message: “Your patient is in the hospital.”

The events of the weekend soon unfolded.

Dr. Lewis learned that when his patient went to the pharmacy to pick up his pain medication, the pharmacist told him the prescription required prior authorization.

The patient left the pharmacy empty-handed. Hours later, he was in the emergency room (ER) in extreme pain — the exact situation Dr. Lewis had been trying to avoid.

Dr. Lewis felt a sense of powerlessness in that moment.

“I had been left in the dark,” he said. The oncologist-patient relationship is predicated on trust and “that trust is eroded when I can’t give my patients the care they need,” he explained. “I can’t stand overpromising and underdelivering to them.”

Dr. Lewis had received no communication from the insurer that the prescription required prior authorization, no red flag that the request had been denied, and no notification to call the insurer.

Although physicians may need to tread carefully when prescribing opioids over the long term, “this was simply a prescription for 2-3 days of opioids for the exact patient who the drugs were developed to benefit,” Dr. Lewis said. But instead, “he ended up in ER with a pain crisis.”

Prior authorization delays like this often mean patients pay the price.

“These delays are not trivial,” Dr. Lewis said.

A recent study, presented at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium in October, found that among 3304 supportive care prescriptions requiring prior authorization, insurance companies denied 8% of requests, with final denials taking as long as 78 days. Among approved prescriptions, about 40% happened on the same day, while the remaining took anywhere from 1 to 54 days.

Denying or delaying necessary and cost-effective care, even briefly, can harm patients and lead to higher costs. A 2022 survey from the American Medical Association found that instead of reducing low-value care as insurance companies claim, prior authorization often leads to higher overall use of healthcare resources. More specifically, almost half of physicians surveyed said that prior authorization led to an ER visit or need for immediate care.

In this patient’s case, filling the opioid prescription that Friday would have cost no more than $300, possibly as little as $30. The ER visit to manage the patient’s pain crisis costs thousands.

The major issue overall, Dr. Lewis said, is the disconnect between the time spent waiting for prior authorization approvals and the necessity of these treatments. Dr. Lewis says even standard chemotherapy often requires prior authorization.

“The currency we all share is time,” Dr. Lewis said. “But it often feels like there’s very little urgency on insurance company side to approve a treatment, which places a heavy weight on patients and physicians.”

“It just shouldn’t be this hard,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com as part of the Gatekeepers of Care series on issues oncologists and people with cancer face navigating health insurance company requirements. Read more about the series here. Please email [email protected] to share experiences with prior authorization or other challenges receiving care.

Comments Disputed on Negative Low-Dose Naltrexone Fibromyalgia Trial

Neuroinflammation expert Jarred Younger, PhD, disputes a recent study commentary calling for clinicians to stop prescribing low-dose naltrexone for people with fibromyalgia.

Naltrexone is a nonselective µ-opioid receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at doses of 50-100 mg/day to treat opioid and alcohol dependence. Lower doses, typically 1-5 mg, can produce an analgesic effect via antagonism of receptors on microglial cells that lead to neuroinflammation. The low-dose version, available at compounding pharmacies, is not FDA-approved, but for many years it has been used off-label to treat fibromyalgia and related conditions.

Results from earlier small clinical trials have conflicted, but two conducted by Dr. Younger using doses of 4.5 mg/day showed benefit in reducing pain and other fibromyalgia symptoms. However, a new study from Denmark on 6 mg low-dose naltrexone versus placebo among 99 women with fibromyalgia demonstrated no significant difference in the primary outcome of change in pain intensity from baseline to 12 weeks.

On the other hand, there was a significant improvement in memory, and there were no differences in adverse events or safety, the authors reported in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Nonetheless, an accompanying commentary called the study a “resoundingly negative trial” and advised that while off-label use of low-dose naltrexone could continue for patients already taking it, clinicians should not initiate it for patients who have not previously used it, pending additional data.

Dr. Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, was speaking on December 13, 2023, at a National Institutes of Health meeting about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome about the potential use of low-dose naltrexone for that patient population. He had checked the literature in preparation for his talk and saw the new study, which had just been published December 5, 2023.

During his talk, Dr. Younger said, “It looks like the study was very well done, and all the decisions made sense to me, so I don’t doubt the quality of their data or the statistics.”

But as for the commentary, he said, “I strongly disagree, and I believe the physicians at this conference strongly disagree with that as well. I know plenty of physicians who would say that is not good advice because this drug is so helpful for so many people.”

Indeed, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, who heard Dr. Younger’s talk but hadn’t seen the new study, told this news organization that he is a “fan” of low-dose naltrexone based on his own experience with one patient who had a “clearly beneficial response” and that of other clinicians he’s spoken with about it. “My colleagues say it doesn’t work for everyone because the disease is so heterogeneous ... but it definitely works for some patients.”

Dr. Younger noted that the proportion of people in the Danish study who reported a clinically significant, that is 30% reduction, in pain scores was 45% versus 28% with placebo, not far from the 50% he found in his studies. “If they’d had 40 to 60 more people, they would have had statistically significant difference,” Dr. Younger said.

Indeed, the authors themselves pointed this out in their discussion, noting, “Our study was not powered to detect a significant difference regarding responder indices ... Subgroups of patients with fibromyalgia might respond differently to low-dose naltrexone treatment, and we intend to conduct a responder analysis based on levels of inflammatory biomarkers and specific biomarkers of glial activation, hypothesising that an inflammatory subgroup might benefit from the treatment. Results will be published in subsequent papers.”

The commentary authors responded to that, saying that they “appreciate” the intention to conduct that subgroup analysis, but that it is “probable that the current sample size will preclude robust statistical comparisons but could be a step to generate hypotheses.”

Those authors noted that a systematic review has described both pro-inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor, interleukin [IL]-6, and IL-8) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines as peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in patients with fibromyalgia. “The specific peripheral biomarkers of glial activation are yet to be identified. The neuroinflammation hypothesis of fibromyalgia could be supported if a reduction of central nervous system inflammation would predict improvement of fibromyalgia symptoms. Subsequent work in this area is eagerly awaited.”

In the meantime, Dr. Younger said, “I do not think this should stop us from looking at low-dose naltrexone [or that] we shouldn’t try it. I’ve talked to over a thousand people over the last 10 years. It would be a very bad thing to give up on low-dose naltrexone now.”

Dr. Younger’s work is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, SolveME, the American Fibromyalgia Association, and ME Research UK. Komaroff has no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Neuroinflammation expert Jarred Younger, PhD, disputes a recent study commentary calling for clinicians to stop prescribing low-dose naltrexone for people with fibromyalgia.

Naltrexone is a nonselective µ-opioid receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at doses of 50-100 mg/day to treat opioid and alcohol dependence. Lower doses, typically 1-5 mg, can produce an analgesic effect via antagonism of receptors on microglial cells that lead to neuroinflammation. The low-dose version, available at compounding pharmacies, is not FDA-approved, but for many years it has been used off-label to treat fibromyalgia and related conditions.

Results from earlier small clinical trials have conflicted, but two conducted by Dr. Younger using doses of 4.5 mg/day showed benefit in reducing pain and other fibromyalgia symptoms. However, a new study from Denmark on 6 mg low-dose naltrexone versus placebo among 99 women with fibromyalgia demonstrated no significant difference in the primary outcome of change in pain intensity from baseline to 12 weeks.

On the other hand, there was a significant improvement in memory, and there were no differences in adverse events or safety, the authors reported in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Nonetheless, an accompanying commentary called the study a “resoundingly negative trial” and advised that while off-label use of low-dose naltrexone could continue for patients already taking it, clinicians should not initiate it for patients who have not previously used it, pending additional data.

Dr. Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, was speaking on December 13, 2023, at a National Institutes of Health meeting about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome about the potential use of low-dose naltrexone for that patient population. He had checked the literature in preparation for his talk and saw the new study, which had just been published December 5, 2023.

During his talk, Dr. Younger said, “It looks like the study was very well done, and all the decisions made sense to me, so I don’t doubt the quality of their data or the statistics.”

But as for the commentary, he said, “I strongly disagree, and I believe the physicians at this conference strongly disagree with that as well. I know plenty of physicians who would say that is not good advice because this drug is so helpful for so many people.”

Indeed, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, who heard Dr. Younger’s talk but hadn’t seen the new study, told this news organization that he is a “fan” of low-dose naltrexone based on his own experience with one patient who had a “clearly beneficial response” and that of other clinicians he’s spoken with about it. “My colleagues say it doesn’t work for everyone because the disease is so heterogeneous ... but it definitely works for some patients.”

Dr. Younger noted that the proportion of people in the Danish study who reported a clinically significant, that is 30% reduction, in pain scores was 45% versus 28% with placebo, not far from the 50% he found in his studies. “If they’d had 40 to 60 more people, they would have had statistically significant difference,” Dr. Younger said.

Indeed, the authors themselves pointed this out in their discussion, noting, “Our study was not powered to detect a significant difference regarding responder indices ... Subgroups of patients with fibromyalgia might respond differently to low-dose naltrexone treatment, and we intend to conduct a responder analysis based on levels of inflammatory biomarkers and specific biomarkers of glial activation, hypothesising that an inflammatory subgroup might benefit from the treatment. Results will be published in subsequent papers.”

The commentary authors responded to that, saying that they “appreciate” the intention to conduct that subgroup analysis, but that it is “probable that the current sample size will preclude robust statistical comparisons but could be a step to generate hypotheses.”

Those authors noted that a systematic review has described both pro-inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor, interleukin [IL]-6, and IL-8) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines as peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in patients with fibromyalgia. “The specific peripheral biomarkers of glial activation are yet to be identified. The neuroinflammation hypothesis of fibromyalgia could be supported if a reduction of central nervous system inflammation would predict improvement of fibromyalgia symptoms. Subsequent work in this area is eagerly awaited.”

In the meantime, Dr. Younger said, “I do not think this should stop us from looking at low-dose naltrexone [or that] we shouldn’t try it. I’ve talked to over a thousand people over the last 10 years. It would be a very bad thing to give up on low-dose naltrexone now.”

Dr. Younger’s work is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, SolveME, the American Fibromyalgia Association, and ME Research UK. Komaroff has no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Neuroinflammation expert Jarred Younger, PhD, disputes a recent study commentary calling for clinicians to stop prescribing low-dose naltrexone for people with fibromyalgia.

Naltrexone is a nonselective µ-opioid receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at doses of 50-100 mg/day to treat opioid and alcohol dependence. Lower doses, typically 1-5 mg, can produce an analgesic effect via antagonism of receptors on microglial cells that lead to neuroinflammation. The low-dose version, available at compounding pharmacies, is not FDA-approved, but for many years it has been used off-label to treat fibromyalgia and related conditions.

Results from earlier small clinical trials have conflicted, but two conducted by Dr. Younger using doses of 4.5 mg/day showed benefit in reducing pain and other fibromyalgia symptoms. However, a new study from Denmark on 6 mg low-dose naltrexone versus placebo among 99 women with fibromyalgia demonstrated no significant difference in the primary outcome of change in pain intensity from baseline to 12 weeks.

On the other hand, there was a significant improvement in memory, and there were no differences in adverse events or safety, the authors reported in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Nonetheless, an accompanying commentary called the study a “resoundingly negative trial” and advised that while off-label use of low-dose naltrexone could continue for patients already taking it, clinicians should not initiate it for patients who have not previously used it, pending additional data.

Dr. Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, was speaking on December 13, 2023, at a National Institutes of Health meeting about myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome about the potential use of low-dose naltrexone for that patient population. He had checked the literature in preparation for his talk and saw the new study, which had just been published December 5, 2023.

During his talk, Dr. Younger said, “It looks like the study was very well done, and all the decisions made sense to me, so I don’t doubt the quality of their data or the statistics.”

But as for the commentary, he said, “I strongly disagree, and I believe the physicians at this conference strongly disagree with that as well. I know plenty of physicians who would say that is not good advice because this drug is so helpful for so many people.”

Indeed, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, who heard Dr. Younger’s talk but hadn’t seen the new study, told this news organization that he is a “fan” of low-dose naltrexone based on his own experience with one patient who had a “clearly beneficial response” and that of other clinicians he’s spoken with about it. “My colleagues say it doesn’t work for everyone because the disease is so heterogeneous ... but it definitely works for some patients.”

Dr. Younger noted that the proportion of people in the Danish study who reported a clinically significant, that is 30% reduction, in pain scores was 45% versus 28% with placebo, not far from the 50% he found in his studies. “If they’d had 40 to 60 more people, they would have had statistically significant difference,” Dr. Younger said.

Indeed, the authors themselves pointed this out in their discussion, noting, “Our study was not powered to detect a significant difference regarding responder indices ... Subgroups of patients with fibromyalgia might respond differently to low-dose naltrexone treatment, and we intend to conduct a responder analysis based on levels of inflammatory biomarkers and specific biomarkers of glial activation, hypothesising that an inflammatory subgroup might benefit from the treatment. Results will be published in subsequent papers.”

The commentary authors responded to that, saying that they “appreciate” the intention to conduct that subgroup analysis, but that it is “probable that the current sample size will preclude robust statistical comparisons but could be a step to generate hypotheses.”

Those authors noted that a systematic review has described both pro-inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor, interleukin [IL]-6, and IL-8) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines as peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in patients with fibromyalgia. “The specific peripheral biomarkers of glial activation are yet to be identified. The neuroinflammation hypothesis of fibromyalgia could be supported if a reduction of central nervous system inflammation would predict improvement of fibromyalgia symptoms. Subsequent work in this area is eagerly awaited.”

In the meantime, Dr. Younger said, “I do not think this should stop us from looking at low-dose naltrexone [or that] we shouldn’t try it. I’ve talked to over a thousand people over the last 10 years. It would be a very bad thing to give up on low-dose naltrexone now.”

Dr. Younger’s work is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, SolveME, the American Fibromyalgia Association, and ME Research UK. Komaroff has no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

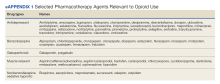

Building a Toolkit for the Treatment of Acute Migraine

Selecting a treatment plan to deal with acute migraine attacks can be like putting together a toolkit of possible therapies, individualized for each patient, one expert said.

The toolkit should comprise reliable treatments that patients know are going to work and that act quickly, allowing them to get back to functioning normally in their daily lives, said Jessica Ailani, MD, during a talk at the 17th European Headache Congress held recently in Barcelona, Spain.

“Everyone with migraine needs acute treatment,” Dr. Ailani, who is a clinical professor of neurology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital and director of the Georgetown Headache Center, Washington, DC, noted. “Sometimes we can reduce acute treatment with preventative agents, but some disability will remain, so we have to focus on good acute treatment, and this becomes more complex if a person has a lot of comorbidities, which is common in older patients.”

In selecting suitable treatments for migraine, consideration has to be given to the patient profile, any other conditions they have, speed of onset of the migraine attack, length of the attack, associated symptoms, and side effects of the medications, she said.

A Complex Case

As an example, Dr. Ailani described the process she used to treat one of her patients who had frequent severe migraines and other issues causing difficult decisions when selecting medications — a woman in her late 60s with several other comorbidities.

“This is the kind of case I see on a daily basis and which keeps me up at night,” she said. “Many times in clinical practice, we see complex cases like this, and through the course of a year, we may try every treatment option we have in a patient like this.”

On the first presentation, the patient had a chronic migraine with severe headaches every day. She had a history of previous cervical discectomy with fusion surgery; uncontrolled hypertension, for which she was taking an angiotensin blocker; high cholesterol, for which she was taking a statin; and diabetes with an A1c of 8. She did not smoke or drink alcohol, exercised moderately, and her body mass index was in a good range.

“Before a patient ever sees a doctor for their migraine, they will have already tried a lot of different things. Most people are already using NSAIDs and acetaminophen, the most commonly used treatments for acute migraine,” Dr. Ailani explains.

Her patient was taking a triptan and the barbiturate, butalbital. Dr. Ailani notes that the triptan is very effective, but in the United States, they are not available over the counter, and the patient is only allowed nine doses per month on her insurance, so she was supplementing with butalbital.

Over the course of a year, Dr. Ailani got her off the butalbital and started her on onabotulinum toxin A for migraine prevention, which reduced her headache days to about 15 per month (8 severe). She then added the anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody, galcanezumab, as another preventative, which further reduced the headache days down to 8-10 days per month (all migraine).

The attacks are rapid onset and can last multiple days. They come with photophobia and phonophobia and cause her to be bedridden, she noted.

“I was still worried about this frequency of headache and the fact she was using a triptan for acute treatment when she had uncontrolled hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Ailani commented.

She explained that triptans are generally not used in individuals aged over 65 years because of a lack of data in this age group. They are also contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular (CV) disease, and caution is advised in patients with CV risk factors. Noting that migraine is an independent risk factor for stroke in healthy individuals, and this patient already had three other major risk factors for stroke, Dr. Ailani said she did not think a triptan was the best option.

When triptans do not work, Dr. Ailani said she thinks about dihydroergotamine, which she describes as “a great drug for long-lasting migraine” as it tends to have a sustained response. But it also has vasoconstrictive effects and can increase blood pressure, so it was not suitable for this patient.

CV risk is also an issue with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), one of the staple treatments for acute migraine.

“NSAIDs are available over the counter, inexpensive, quite effective, and have minimal immediate side effects,” Dr. Ailani said. But long-term adverse events include CV events, particularly in those who already have CV risk factors, and it is now thought that NSAIDs actually carry more CV risk than triptans.

She noted that out of all the NSAIDs, celecoxib carries the lowest CV risk, and in the United States, it is available as a liquid formulation. There is also a study of ketorolac nasal spray showing it to be as effective as sumatriptan nasal spray for acute migraine.

As her patient was still going to the emergency room (ER) quite frequently at this point, Dr. Ailani prescribed ketorolac nasal spray as an emergency rescue medication, which did help to reduce ER visits but did not solve the acute treatment problem.

The next option she tried was the CGRP antagonists or “gepants” because of their good tolerability.

Because her patient had long attacks, Dr. Ailani said her first choice gepant was rimegepant as it has a long half-life.

She noted that in patients who have frequent migraine attacks (> 6 migraine days per month), using rimegepant as needed has been shown to lead to migraine frequency declining over time. “This shows that if we treat acute attacks properly, we can minimize the risk of chronic migraine.”

She pointed out that if a patient has prodrome that is easy to identify or has short attacks, ubrogepant may be a good option, having shown effectiveness in preventing or reducing the onset of the headache in the recently reported PRODROME trial when given the day before migraine starts.

Then there is also zavegepant, which is available as a nasal spray, so it is a good option for patients with nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ailani suggested that zavegepant as a third-generation gepant may be worth trying in patients who have tried the other gepants, as it is a different type of molecule.

For this patient, neither rimegepant nor ubrogepant worked. “We tried treating in the prodrome, when the pain was starting, adding to other treatments, but she is not a ‘gepant’ responder. We have yet to try zavegepant,” she said.

The next consideration was lasmiditan. “This patient is a triptan responder and lasmiditan is a 5HT1 agonist, so it makes sense to try this. Also, it doesn’t have a vasoconstrictor effect as it doesn’t work on the blood vessels, so it is safe for patients with high blood pressure,” Dr. Ailani noted.

She pointed out, however, that lasmiditan has become a rescue medication in her practice because of side effect issues such as dizziness and sleepiness.

But Dr. Ailani said she has learned how to use the medication to minimize the side effects, by increasing the dose slowly and advising patients to take it later in the day.

“We start with 50 mg for a few doses then increase to 100 mg. This seems to build tolerability.”

Her patient has found good relief from lasmiditan 100 mg, but she can’t take it during the day as it makes her sleepy.

As a last resort, Dr. Ailani went back to metoclopramide, which she described as “a tried and tested old-time drug.”

While this does not make the patient sleepy, it has other adverse effects limiting the frequency of its use, she noted. “I ask her to try to limit it to twice a week, and this has been pretty effective. She can function when she uses it.”

Dr. Ailani also points out that neuromodulation should be in everyone’s tool kit. “So, we added an external combined occipital and trigeminal (eCOT device) neurostimulation device.”

The patient’s tool kit now looks like this:

- Neuromodulation device and meditation at first sign of an attack.

- Add metoclopramide 10 mg and acetaminophen 1000 mg.

- If the attack lasts into the second day, add lasmiditan 100 mg in the evening of the second day (limit 8 days a month).

- If the patient has a sudden onset severe migraine with nausea and vomiting that might make her go to the ER, add in ketorolac nasal spray (not > 5 days per month).

Dr. Ailani noted that other patients will need different toolkits, and in most cases, it is recommended to think about “situational prevention” for times when migraine attacks are predictable, which may include air travel, high-stress times (holidays, etc.), occasions when alcohol will be consumed, and at times of certain weather triggers.

Dr. Ailani disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Selecting a treatment plan to deal with acute migraine attacks can be like putting together a toolkit of possible therapies, individualized for each patient, one expert said.

The toolkit should comprise reliable treatments that patients know are going to work and that act quickly, allowing them to get back to functioning normally in their daily lives, said Jessica Ailani, MD, during a talk at the 17th European Headache Congress held recently in Barcelona, Spain.

“Everyone with migraine needs acute treatment,” Dr. Ailani, who is a clinical professor of neurology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital and director of the Georgetown Headache Center, Washington, DC, noted. “Sometimes we can reduce acute treatment with preventative agents, but some disability will remain, so we have to focus on good acute treatment, and this becomes more complex if a person has a lot of comorbidities, which is common in older patients.”

In selecting suitable treatments for migraine, consideration has to be given to the patient profile, any other conditions they have, speed of onset of the migraine attack, length of the attack, associated symptoms, and side effects of the medications, she said.

A Complex Case

As an example, Dr. Ailani described the process she used to treat one of her patients who had frequent severe migraines and other issues causing difficult decisions when selecting medications — a woman in her late 60s with several other comorbidities.

“This is the kind of case I see on a daily basis and which keeps me up at night,” she said. “Many times in clinical practice, we see complex cases like this, and through the course of a year, we may try every treatment option we have in a patient like this.”

On the first presentation, the patient had a chronic migraine with severe headaches every day. She had a history of previous cervical discectomy with fusion surgery; uncontrolled hypertension, for which she was taking an angiotensin blocker; high cholesterol, for which she was taking a statin; and diabetes with an A1c of 8. She did not smoke or drink alcohol, exercised moderately, and her body mass index was in a good range.

“Before a patient ever sees a doctor for their migraine, they will have already tried a lot of different things. Most people are already using NSAIDs and acetaminophen, the most commonly used treatments for acute migraine,” Dr. Ailani explains.

Her patient was taking a triptan and the barbiturate, butalbital. Dr. Ailani notes that the triptan is very effective, but in the United States, they are not available over the counter, and the patient is only allowed nine doses per month on her insurance, so she was supplementing with butalbital.

Over the course of a year, Dr. Ailani got her off the butalbital and started her on onabotulinum toxin A for migraine prevention, which reduced her headache days to about 15 per month (8 severe). She then added the anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody, galcanezumab, as another preventative, which further reduced the headache days down to 8-10 days per month (all migraine).

The attacks are rapid onset and can last multiple days. They come with photophobia and phonophobia and cause her to be bedridden, she noted.

“I was still worried about this frequency of headache and the fact she was using a triptan for acute treatment when she had uncontrolled hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Ailani commented.

She explained that triptans are generally not used in individuals aged over 65 years because of a lack of data in this age group. They are also contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular (CV) disease, and caution is advised in patients with CV risk factors. Noting that migraine is an independent risk factor for stroke in healthy individuals, and this patient already had three other major risk factors for stroke, Dr. Ailani said she did not think a triptan was the best option.

When triptans do not work, Dr. Ailani said she thinks about dihydroergotamine, which she describes as “a great drug for long-lasting migraine” as it tends to have a sustained response. But it also has vasoconstrictive effects and can increase blood pressure, so it was not suitable for this patient.

CV risk is also an issue with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), one of the staple treatments for acute migraine.

“NSAIDs are available over the counter, inexpensive, quite effective, and have minimal immediate side effects,” Dr. Ailani said. But long-term adverse events include CV events, particularly in those who already have CV risk factors, and it is now thought that NSAIDs actually carry more CV risk than triptans.

She noted that out of all the NSAIDs, celecoxib carries the lowest CV risk, and in the United States, it is available as a liquid formulation. There is also a study of ketorolac nasal spray showing it to be as effective as sumatriptan nasal spray for acute migraine.

As her patient was still going to the emergency room (ER) quite frequently at this point, Dr. Ailani prescribed ketorolac nasal spray as an emergency rescue medication, which did help to reduce ER visits but did not solve the acute treatment problem.

The next option she tried was the CGRP antagonists or “gepants” because of their good tolerability.

Because her patient had long attacks, Dr. Ailani said her first choice gepant was rimegepant as it has a long half-life.

She noted that in patients who have frequent migraine attacks (> 6 migraine days per month), using rimegepant as needed has been shown to lead to migraine frequency declining over time. “This shows that if we treat acute attacks properly, we can minimize the risk of chronic migraine.”

She pointed out that if a patient has prodrome that is easy to identify or has short attacks, ubrogepant may be a good option, having shown effectiveness in preventing or reducing the onset of the headache in the recently reported PRODROME trial when given the day before migraine starts.

Then there is also zavegepant, which is available as a nasal spray, so it is a good option for patients with nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ailani suggested that zavegepant as a third-generation gepant may be worth trying in patients who have tried the other gepants, as it is a different type of molecule.

For this patient, neither rimegepant nor ubrogepant worked. “We tried treating in the prodrome, when the pain was starting, adding to other treatments, but she is not a ‘gepant’ responder. We have yet to try zavegepant,” she said.

The next consideration was lasmiditan. “This patient is a triptan responder and lasmiditan is a 5HT1 agonist, so it makes sense to try this. Also, it doesn’t have a vasoconstrictor effect as it doesn’t work on the blood vessels, so it is safe for patients with high blood pressure,” Dr. Ailani noted.

She pointed out, however, that lasmiditan has become a rescue medication in her practice because of side effect issues such as dizziness and sleepiness.

But Dr. Ailani said she has learned how to use the medication to minimize the side effects, by increasing the dose slowly and advising patients to take it later in the day.

“We start with 50 mg for a few doses then increase to 100 mg. This seems to build tolerability.”

Her patient has found good relief from lasmiditan 100 mg, but she can’t take it during the day as it makes her sleepy.

As a last resort, Dr. Ailani went back to metoclopramide, which she described as “a tried and tested old-time drug.”

While this does not make the patient sleepy, it has other adverse effects limiting the frequency of its use, she noted. “I ask her to try to limit it to twice a week, and this has been pretty effective. She can function when she uses it.”

Dr. Ailani also points out that neuromodulation should be in everyone’s tool kit. “So, we added an external combined occipital and trigeminal (eCOT device) neurostimulation device.”

The patient’s tool kit now looks like this:

- Neuromodulation device and meditation at first sign of an attack.

- Add metoclopramide 10 mg and acetaminophen 1000 mg.

- If the attack lasts into the second day, add lasmiditan 100 mg in the evening of the second day (limit 8 days a month).

- If the patient has a sudden onset severe migraine with nausea and vomiting that might make her go to the ER, add in ketorolac nasal spray (not > 5 days per month).

Dr. Ailani noted that other patients will need different toolkits, and in most cases, it is recommended to think about “situational prevention” for times when migraine attacks are predictable, which may include air travel, high-stress times (holidays, etc.), occasions when alcohol will be consumed, and at times of certain weather triggers.

Dr. Ailani disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Selecting a treatment plan to deal with acute migraine attacks can be like putting together a toolkit of possible therapies, individualized for each patient, one expert said.

The toolkit should comprise reliable treatments that patients know are going to work and that act quickly, allowing them to get back to functioning normally in their daily lives, said Jessica Ailani, MD, during a talk at the 17th European Headache Congress held recently in Barcelona, Spain.

“Everyone with migraine needs acute treatment,” Dr. Ailani, who is a clinical professor of neurology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital and director of the Georgetown Headache Center, Washington, DC, noted. “Sometimes we can reduce acute treatment with preventative agents, but some disability will remain, so we have to focus on good acute treatment, and this becomes more complex if a person has a lot of comorbidities, which is common in older patients.”

In selecting suitable treatments for migraine, consideration has to be given to the patient profile, any other conditions they have, speed of onset of the migraine attack, length of the attack, associated symptoms, and side effects of the medications, she said.

A Complex Case

As an example, Dr. Ailani described the process she used to treat one of her patients who had frequent severe migraines and other issues causing difficult decisions when selecting medications — a woman in her late 60s with several other comorbidities.

“This is the kind of case I see on a daily basis and which keeps me up at night,” she said. “Many times in clinical practice, we see complex cases like this, and through the course of a year, we may try every treatment option we have in a patient like this.”

On the first presentation, the patient had a chronic migraine with severe headaches every day. She had a history of previous cervical discectomy with fusion surgery; uncontrolled hypertension, for which she was taking an angiotensin blocker; high cholesterol, for which she was taking a statin; and diabetes with an A1c of 8. She did not smoke or drink alcohol, exercised moderately, and her body mass index was in a good range.

“Before a patient ever sees a doctor for their migraine, they will have already tried a lot of different things. Most people are already using NSAIDs and acetaminophen, the most commonly used treatments for acute migraine,” Dr. Ailani explains.

Her patient was taking a triptan and the barbiturate, butalbital. Dr. Ailani notes that the triptan is very effective, but in the United States, they are not available over the counter, and the patient is only allowed nine doses per month on her insurance, so she was supplementing with butalbital.

Over the course of a year, Dr. Ailani got her off the butalbital and started her on onabotulinum toxin A for migraine prevention, which reduced her headache days to about 15 per month (8 severe). She then added the anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody, galcanezumab, as another preventative, which further reduced the headache days down to 8-10 days per month (all migraine).

The attacks are rapid onset and can last multiple days. They come with photophobia and phonophobia and cause her to be bedridden, she noted.

“I was still worried about this frequency of headache and the fact she was using a triptan for acute treatment when she had uncontrolled hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Ailani commented.

She explained that triptans are generally not used in individuals aged over 65 years because of a lack of data in this age group. They are also contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular (CV) disease, and caution is advised in patients with CV risk factors. Noting that migraine is an independent risk factor for stroke in healthy individuals, and this patient already had three other major risk factors for stroke, Dr. Ailani said she did not think a triptan was the best option.

When triptans do not work, Dr. Ailani said she thinks about dihydroergotamine, which she describes as “a great drug for long-lasting migraine” as it tends to have a sustained response. But it also has vasoconstrictive effects and can increase blood pressure, so it was not suitable for this patient.

CV risk is also an issue with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), one of the staple treatments for acute migraine.

“NSAIDs are available over the counter, inexpensive, quite effective, and have minimal immediate side effects,” Dr. Ailani said. But long-term adverse events include CV events, particularly in those who already have CV risk factors, and it is now thought that NSAIDs actually carry more CV risk than triptans.

She noted that out of all the NSAIDs, celecoxib carries the lowest CV risk, and in the United States, it is available as a liquid formulation. There is also a study of ketorolac nasal spray showing it to be as effective as sumatriptan nasal spray for acute migraine.

As her patient was still going to the emergency room (ER) quite frequently at this point, Dr. Ailani prescribed ketorolac nasal spray as an emergency rescue medication, which did help to reduce ER visits but did not solve the acute treatment problem.

The next option she tried was the CGRP antagonists or “gepants” because of their good tolerability.

Because her patient had long attacks, Dr. Ailani said her first choice gepant was rimegepant as it has a long half-life.

She noted that in patients who have frequent migraine attacks (> 6 migraine days per month), using rimegepant as needed has been shown to lead to migraine frequency declining over time. “This shows that if we treat acute attacks properly, we can minimize the risk of chronic migraine.”

She pointed out that if a patient has prodrome that is easy to identify or has short attacks, ubrogepant may be a good option, having shown effectiveness in preventing or reducing the onset of the headache in the recently reported PRODROME trial when given the day before migraine starts.

Then there is also zavegepant, which is available as a nasal spray, so it is a good option for patients with nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ailani suggested that zavegepant as a third-generation gepant may be worth trying in patients who have tried the other gepants, as it is a different type of molecule.

For this patient, neither rimegepant nor ubrogepant worked. “We tried treating in the prodrome, when the pain was starting, adding to other treatments, but she is not a ‘gepant’ responder. We have yet to try zavegepant,” she said.

The next consideration was lasmiditan. “This patient is a triptan responder and lasmiditan is a 5HT1 agonist, so it makes sense to try this. Also, it doesn’t have a vasoconstrictor effect as it doesn’t work on the blood vessels, so it is safe for patients with high blood pressure,” Dr. Ailani noted.

She pointed out, however, that lasmiditan has become a rescue medication in her practice because of side effect issues such as dizziness and sleepiness.

But Dr. Ailani said she has learned how to use the medication to minimize the side effects, by increasing the dose slowly and advising patients to take it later in the day.

“We start with 50 mg for a few doses then increase to 100 mg. This seems to build tolerability.”

Her patient has found good relief from lasmiditan 100 mg, but she can’t take it during the day as it makes her sleepy.

As a last resort, Dr. Ailani went back to metoclopramide, which she described as “a tried and tested old-time drug.”

While this does not make the patient sleepy, it has other adverse effects limiting the frequency of its use, she noted. “I ask her to try to limit it to twice a week, and this has been pretty effective. She can function when she uses it.”

Dr. Ailani also points out that neuromodulation should be in everyone’s tool kit. “So, we added an external combined occipital and trigeminal (eCOT device) neurostimulation device.”

The patient’s tool kit now looks like this: