User login

NSAIDs Offer No Relief for Pain From IUD Placement

Research on pain management during placement of intrauterine devices (IUD) is lacking, but most studies so far indicate that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not effective, according to a poster presented at Pain Week 2024 in Las Vegas.

Roughly 79% of the 14 studies included in the systematic review found NSAIDs — one of the most common drugs clinicians advise patients to take before placement — did not diminish discomfort.

“We’re challenging the current practice of using just NSAIDs as a first-line of treatment,” said Kevin Rowland, PhD, professor and chair of biomedical sciences at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine in Houston, who helped conduct the meta-analysis. “We need additional measures.”

Some studies found the drugs offered virtually no improvement for patients, while the biggest drop in pain shown in one study was about 40%. The range of pain levels women reported while using NSAIDs was between 1.8 and 7.3 on the visual analog scale (VAS), with an average score of 4.25.

The review included 10 types of NSAIDs and dosages administered to patients before the procedure. One intramuscular NSAID was included while the remaining were oral. All studies were peer-reviewed, used the VAS pain scale, and were not limited to any specific population.

The findings highlight a longstanding but unresolved problem in reproductive health: An overall lack of effective pain management strategies for gynecologic procedures.

“We went into this having a pretty good idea of what we were going to find because [the lack of NSAID efficacy] has been shown before, it’s been talked about before, and we’re just not listening as a medical community,” said Isabella D. Martingano, an MD candidate at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, who led the review.

The research also points to a lack of robust studies on pain during IUD placement, said Emma Lakey, a coauthor and medical student at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine.

“We were only able to review 14 studies, which was enough to go off of, but considering we were looking for trials about pain control for a procedure that helps prevent pregnancy, that’s just not enough research,” Ms. Lakey said.

Discomfort associated with IUD placement ranges from mild to severe, can last for over a week, and includes cramping, bleeding, lightheadedness, nausea, and fainting. Some research suggests that providers may underestimate the level of pain the procedures cause.

“Unfortunately, the pain associated with IUD insertion and removal has been underplayed for a long time and many practitioners in the field likely haven’t counseled patients fully on what the procedure will feel like,” said Jennifer Chin, MD, an ob.gyn. and assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

NSAIDs are not mentioned in the recently expanded guidelines on IUD placement from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC recommends lidocaine paracervical blocks, gels, sprays, and creams, plus counseling women about pain ahead of the procedures.

IUDs are one of the most effective forms of birth control, with a failure rate below 1%.

Yet hearing about painful placement keeps many women from seeking out an IUD or replacing an existing device, Dr. Rowland said. The review adds to the body of evidence that current strategies are not working and that more research is needed, he said.

According to Dr. Chin, making IUDs more accessible means taking a more personalized approach to pain management while understanding that what may be a painless procedure for one patient may be excruciating for another.

Dr. Chin offers a range of options for her patients, including NSAIDs, lorazepam for anxiety, paracervical blocks, lidocaine jelly and spray, intravenous sedation, and general anesthesia. She also talks to her patients through the procedure and provides guided imagery and meditation.

“We should always make sure we’re prioritizing the patients and providing evidence-based, compassionate, and individualized care,” said Dr. Chin. “Each patient comes to us in a particular context and with a specific set of experiences and history that will make a difference in how we’re best able to take care of them.”

The authors reported no disclosures and no sources of funding. Dr. Chin reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Research on pain management during placement of intrauterine devices (IUD) is lacking, but most studies so far indicate that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not effective, according to a poster presented at Pain Week 2024 in Las Vegas.

Roughly 79% of the 14 studies included in the systematic review found NSAIDs — one of the most common drugs clinicians advise patients to take before placement — did not diminish discomfort.

“We’re challenging the current practice of using just NSAIDs as a first-line of treatment,” said Kevin Rowland, PhD, professor and chair of biomedical sciences at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine in Houston, who helped conduct the meta-analysis. “We need additional measures.”

Some studies found the drugs offered virtually no improvement for patients, while the biggest drop in pain shown in one study was about 40%. The range of pain levels women reported while using NSAIDs was between 1.8 and 7.3 on the visual analog scale (VAS), with an average score of 4.25.

The review included 10 types of NSAIDs and dosages administered to patients before the procedure. One intramuscular NSAID was included while the remaining were oral. All studies were peer-reviewed, used the VAS pain scale, and were not limited to any specific population.

The findings highlight a longstanding but unresolved problem in reproductive health: An overall lack of effective pain management strategies for gynecologic procedures.

“We went into this having a pretty good idea of what we were going to find because [the lack of NSAID efficacy] has been shown before, it’s been talked about before, and we’re just not listening as a medical community,” said Isabella D. Martingano, an MD candidate at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, who led the review.

The research also points to a lack of robust studies on pain during IUD placement, said Emma Lakey, a coauthor and medical student at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine.

“We were only able to review 14 studies, which was enough to go off of, but considering we were looking for trials about pain control for a procedure that helps prevent pregnancy, that’s just not enough research,” Ms. Lakey said.

Discomfort associated with IUD placement ranges from mild to severe, can last for over a week, and includes cramping, bleeding, lightheadedness, nausea, and fainting. Some research suggests that providers may underestimate the level of pain the procedures cause.

“Unfortunately, the pain associated with IUD insertion and removal has been underplayed for a long time and many practitioners in the field likely haven’t counseled patients fully on what the procedure will feel like,” said Jennifer Chin, MD, an ob.gyn. and assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

NSAIDs are not mentioned in the recently expanded guidelines on IUD placement from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC recommends lidocaine paracervical blocks, gels, sprays, and creams, plus counseling women about pain ahead of the procedures.

IUDs are one of the most effective forms of birth control, with a failure rate below 1%.

Yet hearing about painful placement keeps many women from seeking out an IUD or replacing an existing device, Dr. Rowland said. The review adds to the body of evidence that current strategies are not working and that more research is needed, he said.

According to Dr. Chin, making IUDs more accessible means taking a more personalized approach to pain management while understanding that what may be a painless procedure for one patient may be excruciating for another.

Dr. Chin offers a range of options for her patients, including NSAIDs, lorazepam for anxiety, paracervical blocks, lidocaine jelly and spray, intravenous sedation, and general anesthesia. She also talks to her patients through the procedure and provides guided imagery and meditation.

“We should always make sure we’re prioritizing the patients and providing evidence-based, compassionate, and individualized care,” said Dr. Chin. “Each patient comes to us in a particular context and with a specific set of experiences and history that will make a difference in how we’re best able to take care of them.”

The authors reported no disclosures and no sources of funding. Dr. Chin reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Research on pain management during placement of intrauterine devices (IUD) is lacking, but most studies so far indicate that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not effective, according to a poster presented at Pain Week 2024 in Las Vegas.

Roughly 79% of the 14 studies included in the systematic review found NSAIDs — one of the most common drugs clinicians advise patients to take before placement — did not diminish discomfort.

“We’re challenging the current practice of using just NSAIDs as a first-line of treatment,” said Kevin Rowland, PhD, professor and chair of biomedical sciences at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine in Houston, who helped conduct the meta-analysis. “We need additional measures.”

Some studies found the drugs offered virtually no improvement for patients, while the biggest drop in pain shown in one study was about 40%. The range of pain levels women reported while using NSAIDs was between 1.8 and 7.3 on the visual analog scale (VAS), with an average score of 4.25.

The review included 10 types of NSAIDs and dosages administered to patients before the procedure. One intramuscular NSAID was included while the remaining were oral. All studies were peer-reviewed, used the VAS pain scale, and were not limited to any specific population.

The findings highlight a longstanding but unresolved problem in reproductive health: An overall lack of effective pain management strategies for gynecologic procedures.

“We went into this having a pretty good idea of what we were going to find because [the lack of NSAID efficacy] has been shown before, it’s been talked about before, and we’re just not listening as a medical community,” said Isabella D. Martingano, an MD candidate at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, who led the review.

The research also points to a lack of robust studies on pain during IUD placement, said Emma Lakey, a coauthor and medical student at Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine.

“We were only able to review 14 studies, which was enough to go off of, but considering we were looking for trials about pain control for a procedure that helps prevent pregnancy, that’s just not enough research,” Ms. Lakey said.

Discomfort associated with IUD placement ranges from mild to severe, can last for over a week, and includes cramping, bleeding, lightheadedness, nausea, and fainting. Some research suggests that providers may underestimate the level of pain the procedures cause.

“Unfortunately, the pain associated with IUD insertion and removal has been underplayed for a long time and many practitioners in the field likely haven’t counseled patients fully on what the procedure will feel like,” said Jennifer Chin, MD, an ob.gyn. and assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

NSAIDs are not mentioned in the recently expanded guidelines on IUD placement from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC recommends lidocaine paracervical blocks, gels, sprays, and creams, plus counseling women about pain ahead of the procedures.

IUDs are one of the most effective forms of birth control, with a failure rate below 1%.

Yet hearing about painful placement keeps many women from seeking out an IUD or replacing an existing device, Dr. Rowland said. The review adds to the body of evidence that current strategies are not working and that more research is needed, he said.

According to Dr. Chin, making IUDs more accessible means taking a more personalized approach to pain management while understanding that what may be a painless procedure for one patient may be excruciating for another.

Dr. Chin offers a range of options for her patients, including NSAIDs, lorazepam for anxiety, paracervical blocks, lidocaine jelly and spray, intravenous sedation, and general anesthesia. She also talks to her patients through the procedure and provides guided imagery and meditation.

“We should always make sure we’re prioritizing the patients and providing evidence-based, compassionate, and individualized care,” said Dr. Chin. “Each patient comes to us in a particular context and with a specific set of experiences and history that will make a difference in how we’re best able to take care of them.”

The authors reported no disclosures and no sources of funding. Dr. Chin reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do Cannabis Users Need More Anesthesia During Surgery?

TOPLINE:

However, the clinical relevance of this difference remains unclear.

METHODOLOGY:

- To assess if cannabis use leads to higher doses of inhalational anesthesia during surgery, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing the average intraoperative minimum alveolar concentrations of volatile anesthetics (isoflurane and sevoflurane) between older adults who used cannabis products and those who did not.

- The researchers reviewed electronic health records of 22,476 patients aged 65 years or older who underwent surgery at the University of Florida Health System between 2018 and 2020.

- Overall, 268 patients who reported using cannabis within 60 days of surgery (median age, 69 years; 35% women) were matched to 1072 nonusers.

- The median duration of anesthesia was 175 minutes.

- The primary outcome was the intraoperative time-weighted average of isoflurane or sevoflurane minimum alveolar concentration equivalents.

TAKEAWAY:

- Cannabis users had significantly higher average minimum alveolar concentrations of isoflurane or sevoflurane than nonusers (mean, 0.58 vs 0.54; mean difference, 0.04; P = .021).

- The findings were confirmed in a sensitivity analysis that revealed higher mean average minimum alveolar concentrations of anesthesia in cannabis users than in nonusers (0.57 vs 0.53; P = .029).

- Although the 0.04 difference in minimum alveolar concentration between cannabis users and nonusers was statistically significant, its clinical importance is unclear.

IN PRACTICE:

“While recent guidelines underscore the importance of universal screening for cannabinoids before surgery, caution is paramount to prevent clinical bias leading to the administration of unnecessary higher doses of inhalational anesthesia, especially as robust evidence supporting such practices remains lacking,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Ruba Sajdeya, MD, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and was published online in August 2024 in Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study lacked access to prescription or dispensed medications, including opioids, which may have introduced residual confounding. Potential underdocumentation of cannabis use in medical records could have led to exposure misclassification. The causality between cannabis usage and increased anesthetic dosing could not be established due to the observational nature of this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Some authors declared receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria and having other ties with pharmaceutical companies and various other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

However, the clinical relevance of this difference remains unclear.

METHODOLOGY:

- To assess if cannabis use leads to higher doses of inhalational anesthesia during surgery, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing the average intraoperative minimum alveolar concentrations of volatile anesthetics (isoflurane and sevoflurane) between older adults who used cannabis products and those who did not.

- The researchers reviewed electronic health records of 22,476 patients aged 65 years or older who underwent surgery at the University of Florida Health System between 2018 and 2020.

- Overall, 268 patients who reported using cannabis within 60 days of surgery (median age, 69 years; 35% women) were matched to 1072 nonusers.

- The median duration of anesthesia was 175 minutes.

- The primary outcome was the intraoperative time-weighted average of isoflurane or sevoflurane minimum alveolar concentration equivalents.

TAKEAWAY:

- Cannabis users had significantly higher average minimum alveolar concentrations of isoflurane or sevoflurane than nonusers (mean, 0.58 vs 0.54; mean difference, 0.04; P = .021).

- The findings were confirmed in a sensitivity analysis that revealed higher mean average minimum alveolar concentrations of anesthesia in cannabis users than in nonusers (0.57 vs 0.53; P = .029).

- Although the 0.04 difference in minimum alveolar concentration between cannabis users and nonusers was statistically significant, its clinical importance is unclear.

IN PRACTICE:

“While recent guidelines underscore the importance of universal screening for cannabinoids before surgery, caution is paramount to prevent clinical bias leading to the administration of unnecessary higher doses of inhalational anesthesia, especially as robust evidence supporting such practices remains lacking,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Ruba Sajdeya, MD, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and was published online in August 2024 in Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study lacked access to prescription or dispensed medications, including opioids, which may have introduced residual confounding. Potential underdocumentation of cannabis use in medical records could have led to exposure misclassification. The causality between cannabis usage and increased anesthetic dosing could not be established due to the observational nature of this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Some authors declared receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria and having other ties with pharmaceutical companies and various other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

However, the clinical relevance of this difference remains unclear.

METHODOLOGY:

- To assess if cannabis use leads to higher doses of inhalational anesthesia during surgery, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing the average intraoperative minimum alveolar concentrations of volatile anesthetics (isoflurane and sevoflurane) between older adults who used cannabis products and those who did not.

- The researchers reviewed electronic health records of 22,476 patients aged 65 years or older who underwent surgery at the University of Florida Health System between 2018 and 2020.

- Overall, 268 patients who reported using cannabis within 60 days of surgery (median age, 69 years; 35% women) were matched to 1072 nonusers.

- The median duration of anesthesia was 175 minutes.

- The primary outcome was the intraoperative time-weighted average of isoflurane or sevoflurane minimum alveolar concentration equivalents.

TAKEAWAY:

- Cannabis users had significantly higher average minimum alveolar concentrations of isoflurane or sevoflurane than nonusers (mean, 0.58 vs 0.54; mean difference, 0.04; P = .021).

- The findings were confirmed in a sensitivity analysis that revealed higher mean average minimum alveolar concentrations of anesthesia in cannabis users than in nonusers (0.57 vs 0.53; P = .029).

- Although the 0.04 difference in minimum alveolar concentration between cannabis users and nonusers was statistically significant, its clinical importance is unclear.

IN PRACTICE:

“While recent guidelines underscore the importance of universal screening for cannabinoids before surgery, caution is paramount to prevent clinical bias leading to the administration of unnecessary higher doses of inhalational anesthesia, especially as robust evidence supporting such practices remains lacking,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Ruba Sajdeya, MD, PhD, of the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and was published online in August 2024 in Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study lacked access to prescription or dispensed medications, including opioids, which may have introduced residual confounding. Potential underdocumentation of cannabis use in medical records could have led to exposure misclassification. The causality between cannabis usage and increased anesthetic dosing could not be established due to the observational nature of this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Some authors declared receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria and having other ties with pharmaceutical companies and various other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Prohibitive Price Tag

Earlier in 2024 the American Headache Society issued a position statement that CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) agents are a first-line option for migraine prevention.

No Shinola, Sherlock.

Any of us working frontline neurology have figured that out, including me. And I was, honestly, pretty skeptical of them when they hit the pharmacy shelves. But these days, to quote The Monkees (and Neil Diamond), “I’m a Believer.”

Unfortunately, things don’t quite work out that way. Just because a drug is clearly successful doesn’t make it practical to use first line. Most insurances won’t even let family doctors prescribe them, so they have to send patients to a neurologist (which I’m not complaining about).

Then me and my neuro-brethren have to jump through hoops because of their cost. One month of any of these drugs costs the same as a few years (or more) of generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Granted, I shouldn’t complain about that, either. If everyone with migraines was getting them it would drive up insurance premiums across the board — including mine.

So, after patients have tried and failed at least two to four other options (depending on their plan) I can usually get a CGRP covered. This involves filling out some forms online and submitting them ... then waiting.

Even if the drug is approved, and successful, that’s still not the end of the story. Depending on the plan I have to get them reauthorized anywhere from every 3 to 12 months. There’s also the chance that in December I’ll get a letter saying the drug won’t be covered starting January, and to try one of the recommended alternatives, like generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Having celebrities like Lady Gaga pushing them doesn’t help. The commercials never mention that getting the medication isn’t as easy as “ask your doctor.” Nor does it point out that Lady Gaga won’t have an issue with a CGRP agent’s price tag of $800-$1000 per month, while most of her fans need that money for rent and groceries.

The guidelines, in essence, are useful, but only apply to a perfect world where drug cost doesn’t matter. We aren’t in one. I’m not knocking the pharmaceutical companies — research and development take A LOT of money, and every drug that comes to market has to pay not only for itself, but for several others that failed. Innovation isn’t cheap.

That doesn’t make it any easier to explain to patients, who see ads, or news blurbs on Facebook, or whatever. I just wish the advertisements would have more transparency about how the pricing works.

After all, regardless of how good an automobile may be, don’t car ads show an MSRP?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Earlier in 2024 the American Headache Society issued a position statement that CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) agents are a first-line option for migraine prevention.

No Shinola, Sherlock.

Any of us working frontline neurology have figured that out, including me. And I was, honestly, pretty skeptical of them when they hit the pharmacy shelves. But these days, to quote The Monkees (and Neil Diamond), “I’m a Believer.”

Unfortunately, things don’t quite work out that way. Just because a drug is clearly successful doesn’t make it practical to use first line. Most insurances won’t even let family doctors prescribe them, so they have to send patients to a neurologist (which I’m not complaining about).

Then me and my neuro-brethren have to jump through hoops because of their cost. One month of any of these drugs costs the same as a few years (or more) of generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Granted, I shouldn’t complain about that, either. If everyone with migraines was getting them it would drive up insurance premiums across the board — including mine.

So, after patients have tried and failed at least two to four other options (depending on their plan) I can usually get a CGRP covered. This involves filling out some forms online and submitting them ... then waiting.

Even if the drug is approved, and successful, that’s still not the end of the story. Depending on the plan I have to get them reauthorized anywhere from every 3 to 12 months. There’s also the chance that in December I’ll get a letter saying the drug won’t be covered starting January, and to try one of the recommended alternatives, like generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Having celebrities like Lady Gaga pushing them doesn’t help. The commercials never mention that getting the medication isn’t as easy as “ask your doctor.” Nor does it point out that Lady Gaga won’t have an issue with a CGRP agent’s price tag of $800-$1000 per month, while most of her fans need that money for rent and groceries.

The guidelines, in essence, are useful, but only apply to a perfect world where drug cost doesn’t matter. We aren’t in one. I’m not knocking the pharmaceutical companies — research and development take A LOT of money, and every drug that comes to market has to pay not only for itself, but for several others that failed. Innovation isn’t cheap.

That doesn’t make it any easier to explain to patients, who see ads, or news blurbs on Facebook, or whatever. I just wish the advertisements would have more transparency about how the pricing works.

After all, regardless of how good an automobile may be, don’t car ads show an MSRP?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Earlier in 2024 the American Headache Society issued a position statement that CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) agents are a first-line option for migraine prevention.

No Shinola, Sherlock.

Any of us working frontline neurology have figured that out, including me. And I was, honestly, pretty skeptical of them when they hit the pharmacy shelves. But these days, to quote The Monkees (and Neil Diamond), “I’m a Believer.”

Unfortunately, things don’t quite work out that way. Just because a drug is clearly successful doesn’t make it practical to use first line. Most insurances won’t even let family doctors prescribe them, so they have to send patients to a neurologist (which I’m not complaining about).

Then me and my neuro-brethren have to jump through hoops because of their cost. One month of any of these drugs costs the same as a few years (or more) of generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Granted, I shouldn’t complain about that, either. If everyone with migraines was getting them it would drive up insurance premiums across the board — including mine.

So, after patients have tried and failed at least two to four other options (depending on their plan) I can usually get a CGRP covered. This involves filling out some forms online and submitting them ... then waiting.

Even if the drug is approved, and successful, that’s still not the end of the story. Depending on the plan I have to get them reauthorized anywhere from every 3 to 12 months. There’s also the chance that in December I’ll get a letter saying the drug won’t be covered starting January, and to try one of the recommended alternatives, like generic Topamax, Nortriptyline, Nadolol, etc. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Having celebrities like Lady Gaga pushing them doesn’t help. The commercials never mention that getting the medication isn’t as easy as “ask your doctor.” Nor does it point out that Lady Gaga won’t have an issue with a CGRP agent’s price tag of $800-$1000 per month, while most of her fans need that money for rent and groceries.

The guidelines, in essence, are useful, but only apply to a perfect world where drug cost doesn’t matter. We aren’t in one. I’m not knocking the pharmaceutical companies — research and development take A LOT of money, and every drug that comes to market has to pay not only for itself, but for several others that failed. Innovation isn’t cheap.

That doesn’t make it any easier to explain to patients, who see ads, or news blurbs on Facebook, or whatever. I just wish the advertisements would have more transparency about how the pricing works.

After all, regardless of how good an automobile may be, don’t car ads show an MSRP?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Gabapentin: The Hope, the Harm, the Myth, the Reality

Since gabapentin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of partial-onset seizures and postherpetic neuralgia, it has been used in many different ways, many off-label indications, and with several recent safety warnings.

Early Problems

After FDA approval in 1993 (for partial seizures), gabapentin was promoted by its maker (Park-Davis) for off-label indications, especially for pain. There was no FDA approval for that indication and the studies the company had done were deemed to have been manipulated in a subsequent lawsuit.1 Gabapentin became the nonopioid go-to medication for treatment of pain despite underwhelming evidence.

Studies on Neuropathy

In the largest trial of gabapentin for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Rauck and colleagues found no significant difference in pain relief between gabapentin and placebo.2 A Cochrane review of gabapentin for neuropathic pain concluded that about 30%-40% of patients taking gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy achieved meaningful pain relief with gabapentin use, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6.6.3 The review also concluded that for postherpetic neuralgia (an FDA-approved indication) 78% of patients had moderate to substantial benefit with gabapentin (NNT 4.8 for moderate benefit).

Side Effects of Gabapentin

From the Cochrane review, the most common side effects were: dizziness (19%), somnolence (14%), peripheral edema (7%), and gait disturbance (14%). The number needed to harm for gabapentin was 7.5 The two side effects listed here that are often overlooked that I want to highlight are peripheral edema and gait disturbance. I have seen these both fairly frequently over the years. A side effect not found in the Cochrane review was weight gain. Weight gain with gabapentin was reported in a meta-analysis of drugs that can cause weight gain.4

New Warnings

In December 2019, the FDA released a warning on the potential for serious respiratory problems with gabapentin and pregabalin in patients with certain risk factors: opioid use or use of other drugs that depress the central nervous system, COPD, and other severe lung diseases.5 Rahman and colleagues found that compared with nonuse, gabapentinoid use was associated with increased risk for severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.50).6

Off-Label Uses

Primary care professionals frequently use gabapentin for two off-label indications that are incorporated into practice guidelines. Ryan et al. studied gabapentin in patients with refractory, unexplained chronic cough.7 In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, gabapentin improved cough-specific quality of life compared with placebo (P = .004; NNT 3.58). Use of gabapentin for treatment of unexplained, refractory cough has been included in several chronic cough practice guidelines.8,9

Gabapentin has been studied for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and has been recommended as an option to treat moderate to severe restless legs syndrome in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Guidelines.10

Pearl of the Month:

Gabapentin is used widely for many different pain syndromes. The best evidence is for postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy. Be aware of the side effects and risks of use in patients with pulmonary disease and who are taking CNS-depressant medications.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Landefeld CS, Steinman MA. The Neurontin legacy: marketing through misinformation and manipulation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):103-6.

2. Rauck R et al. A randomized, controlled trial of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pain Pract. 2013;13(6):485-96.

3. Wiffen PJ et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD007938.

4. Domecq JP et al. Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Feb;100(2):363-70.

5. 12-19-2019 FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR).

6. Rahman AA et al. Gabapentinoids and risk for severe exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Feb;177(2):144-54.

7. Ryan NM et al. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9853):1583-9.

8. Gibson P et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016 Jan;149(1):27-44.

9. De Vincentis A et al. Chronic cough in adults: recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34:1529.

10. Aurora RN et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults — an update for 2012: Practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Sleep 2012;35:1039.

Since gabapentin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of partial-onset seizures and postherpetic neuralgia, it has been used in many different ways, many off-label indications, and with several recent safety warnings.

Early Problems

After FDA approval in 1993 (for partial seizures), gabapentin was promoted by its maker (Park-Davis) for off-label indications, especially for pain. There was no FDA approval for that indication and the studies the company had done were deemed to have been manipulated in a subsequent lawsuit.1 Gabapentin became the nonopioid go-to medication for treatment of pain despite underwhelming evidence.

Studies on Neuropathy

In the largest trial of gabapentin for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Rauck and colleagues found no significant difference in pain relief between gabapentin and placebo.2 A Cochrane review of gabapentin for neuropathic pain concluded that about 30%-40% of patients taking gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy achieved meaningful pain relief with gabapentin use, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6.6.3 The review also concluded that for postherpetic neuralgia (an FDA-approved indication) 78% of patients had moderate to substantial benefit with gabapentin (NNT 4.8 for moderate benefit).

Side Effects of Gabapentin

From the Cochrane review, the most common side effects were: dizziness (19%), somnolence (14%), peripheral edema (7%), and gait disturbance (14%). The number needed to harm for gabapentin was 7.5 The two side effects listed here that are often overlooked that I want to highlight are peripheral edema and gait disturbance. I have seen these both fairly frequently over the years. A side effect not found in the Cochrane review was weight gain. Weight gain with gabapentin was reported in a meta-analysis of drugs that can cause weight gain.4

New Warnings

In December 2019, the FDA released a warning on the potential for serious respiratory problems with gabapentin and pregabalin in patients with certain risk factors: opioid use or use of other drugs that depress the central nervous system, COPD, and other severe lung diseases.5 Rahman and colleagues found that compared with nonuse, gabapentinoid use was associated with increased risk for severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.50).6

Off-Label Uses

Primary care professionals frequently use gabapentin for two off-label indications that are incorporated into practice guidelines. Ryan et al. studied gabapentin in patients with refractory, unexplained chronic cough.7 In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, gabapentin improved cough-specific quality of life compared with placebo (P = .004; NNT 3.58). Use of gabapentin for treatment of unexplained, refractory cough has been included in several chronic cough practice guidelines.8,9

Gabapentin has been studied for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and has been recommended as an option to treat moderate to severe restless legs syndrome in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Guidelines.10

Pearl of the Month:

Gabapentin is used widely for many different pain syndromes. The best evidence is for postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy. Be aware of the side effects and risks of use in patients with pulmonary disease and who are taking CNS-depressant medications.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Landefeld CS, Steinman MA. The Neurontin legacy: marketing through misinformation and manipulation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):103-6.

2. Rauck R et al. A randomized, controlled trial of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pain Pract. 2013;13(6):485-96.

3. Wiffen PJ et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD007938.

4. Domecq JP et al. Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Feb;100(2):363-70.

5. 12-19-2019 FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR).

6. Rahman AA et al. Gabapentinoids and risk for severe exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Feb;177(2):144-54.

7. Ryan NM et al. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9853):1583-9.

8. Gibson P et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016 Jan;149(1):27-44.

9. De Vincentis A et al. Chronic cough in adults: recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34:1529.

10. Aurora RN et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults — an update for 2012: Practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Sleep 2012;35:1039.

Since gabapentin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of partial-onset seizures and postherpetic neuralgia, it has been used in many different ways, many off-label indications, and with several recent safety warnings.

Early Problems

After FDA approval in 1993 (for partial seizures), gabapentin was promoted by its maker (Park-Davis) for off-label indications, especially for pain. There was no FDA approval for that indication and the studies the company had done were deemed to have been manipulated in a subsequent lawsuit.1 Gabapentin became the nonopioid go-to medication for treatment of pain despite underwhelming evidence.

Studies on Neuropathy

In the largest trial of gabapentin for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Rauck and colleagues found no significant difference in pain relief between gabapentin and placebo.2 A Cochrane review of gabapentin for neuropathic pain concluded that about 30%-40% of patients taking gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy achieved meaningful pain relief with gabapentin use, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6.6.3 The review also concluded that for postherpetic neuralgia (an FDA-approved indication) 78% of patients had moderate to substantial benefit with gabapentin (NNT 4.8 for moderate benefit).

Side Effects of Gabapentin

From the Cochrane review, the most common side effects were: dizziness (19%), somnolence (14%), peripheral edema (7%), and gait disturbance (14%). The number needed to harm for gabapentin was 7.5 The two side effects listed here that are often overlooked that I want to highlight are peripheral edema and gait disturbance. I have seen these both fairly frequently over the years. A side effect not found in the Cochrane review was weight gain. Weight gain with gabapentin was reported in a meta-analysis of drugs that can cause weight gain.4

New Warnings

In December 2019, the FDA released a warning on the potential for serious respiratory problems with gabapentin and pregabalin in patients with certain risk factors: opioid use or use of other drugs that depress the central nervous system, COPD, and other severe lung diseases.5 Rahman and colleagues found that compared with nonuse, gabapentinoid use was associated with increased risk for severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.50).6

Off-Label Uses

Primary care professionals frequently use gabapentin for two off-label indications that are incorporated into practice guidelines. Ryan et al. studied gabapentin in patients with refractory, unexplained chronic cough.7 In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, gabapentin improved cough-specific quality of life compared with placebo (P = .004; NNT 3.58). Use of gabapentin for treatment of unexplained, refractory cough has been included in several chronic cough practice guidelines.8,9

Gabapentin has been studied for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and has been recommended as an option to treat moderate to severe restless legs syndrome in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Guidelines.10

Pearl of the Month:

Gabapentin is used widely for many different pain syndromes. The best evidence is for postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy. Be aware of the side effects and risks of use in patients with pulmonary disease and who are taking CNS-depressant medications.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Landefeld CS, Steinman MA. The Neurontin legacy: marketing through misinformation and manipulation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):103-6.

2. Rauck R et al. A randomized, controlled trial of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pain Pract. 2013;13(6):485-96.

3. Wiffen PJ et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD007938.

4. Domecq JP et al. Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Feb;100(2):363-70.

5. 12-19-2019 FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR).

6. Rahman AA et al. Gabapentinoids and risk for severe exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Feb;177(2):144-54.

7. Ryan NM et al. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9853):1583-9.

8. Gibson P et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016 Jan;149(1):27-44.

9. De Vincentis A et al. Chronic cough in adults: recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34:1529.

10. Aurora RN et al. The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults — an update for 2012: Practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Sleep 2012;35:1039.

Veterans Found Relief From Chronic Pain Through Telehealth Mindfulness

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

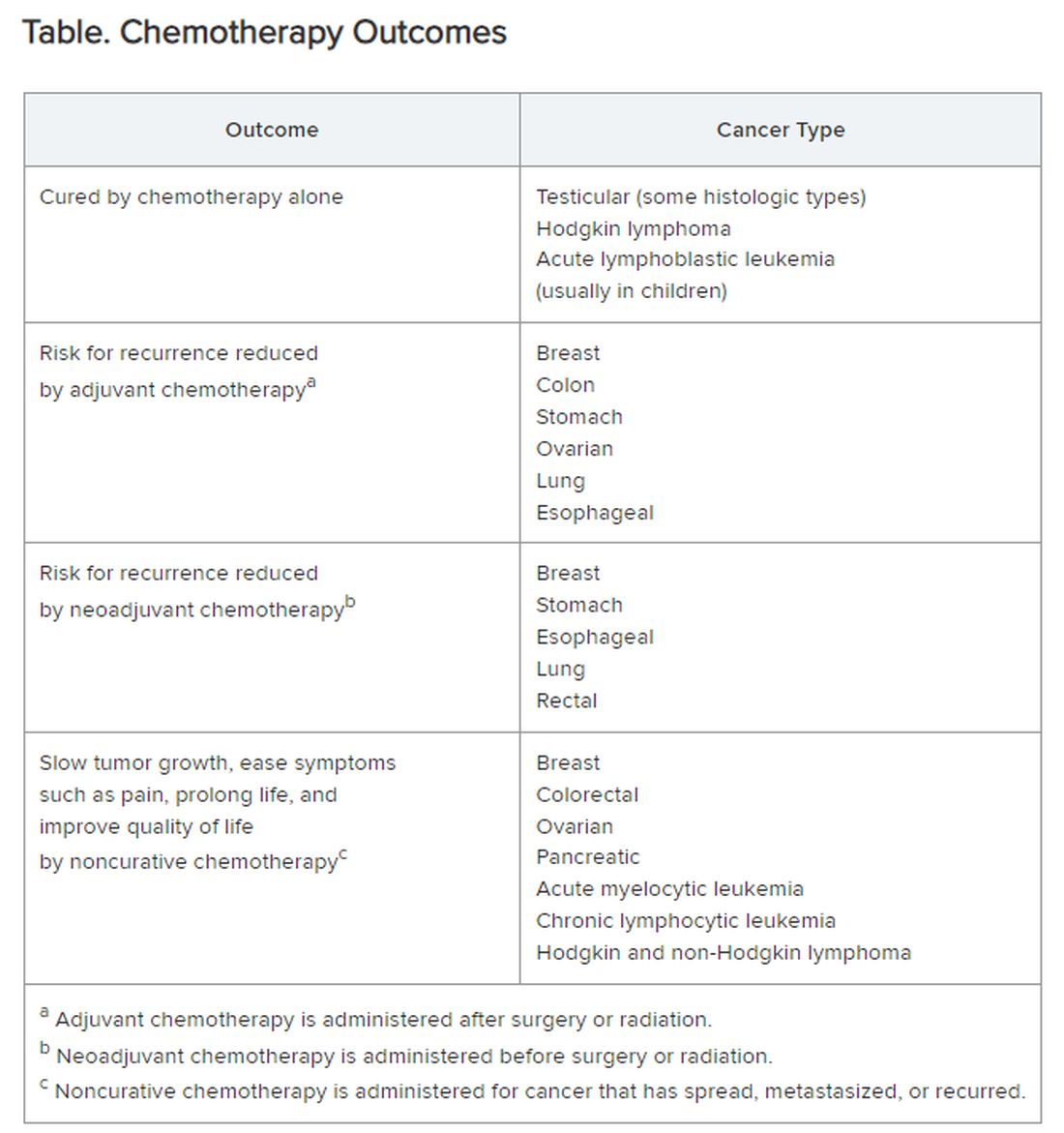

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.