User login

2019-2020 flu season starts off full throttle

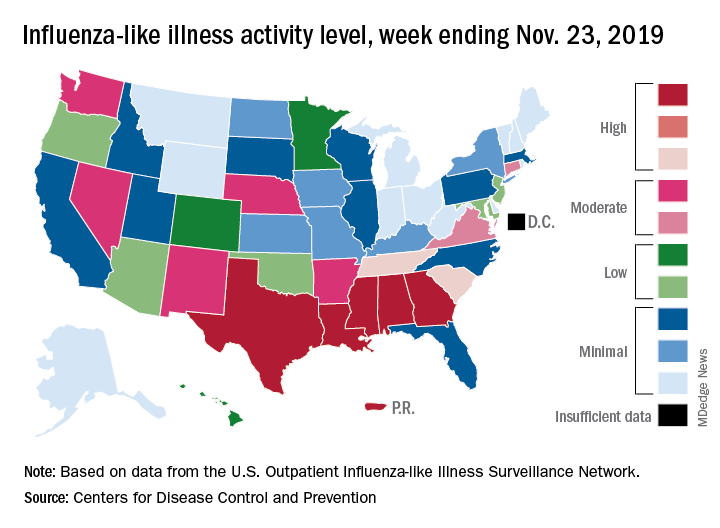

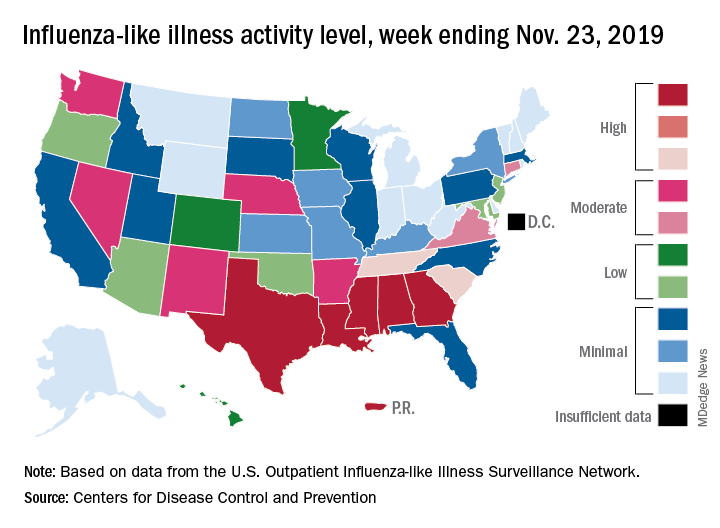

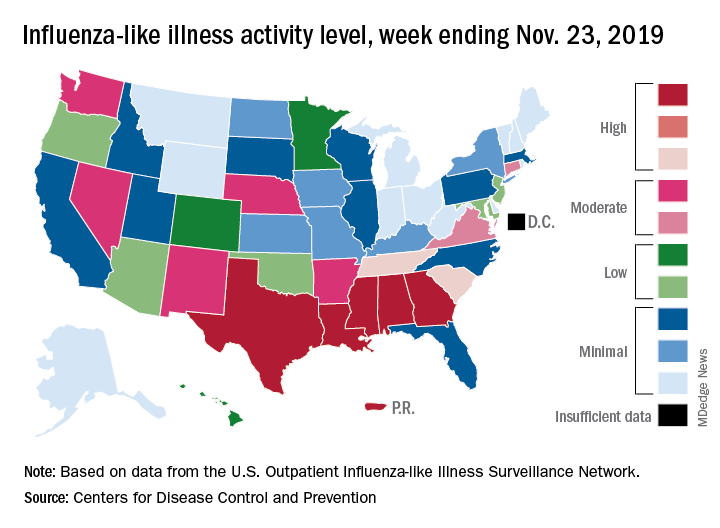

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

Nearly one in five U.S. adolescents have prediabetes

with a higher prevalence among males, a study has found.

Linda J. Andes, PhD, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors reported in JAMA Pediatrics their analysis of data from 2,606 adolescent (12-18 years) and 3,180 young adult (19-34 years) participants in the 2005-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

This found that the percentage with prediabetes – defined as either impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or increased hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level – was 18% among adolescents and 24% among young adults.

The most common condition was IFG, which was seen in 11% of adolescents and 16% of young adults. The rate of IGT was 4% in adolescents and 6% of young adults, while elevated HbA1c levels were seen in 5% of adolescents and 8% of young adults.

This information is important because “In adults, these three phenotypes increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote. “In 2011-2012, the overall prevalence of prediabetes among U.S. adults, defined as the presence of any of the three glucose metabolism dysregulation phenotypes, was 38% and it increased to about 50% in persons 65 years and older.”

Dr. Andes and associates noted that isolated IFG was the most common glucose dysregulation seen in both adolescents and young adults. “While individuals with IFG are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes, few primary prevention trials have included individuals selected for the presence of IFG and none have been conducted in adolescents with IFG or IGT to our knowledge.”

The study saw some key gender differences in prevalence. For example, the prevalence of IFG was significantly lower in adolescent girls than in boys (7% vs. 15%; P less than .001), and in young women, compared with young men (10% vs. 22%; P less than .001).

“These findings are consistent with those of other studies in adults; however, the underlying mechanisms for explaining this discrepancy are still unclear,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote.

Ethnicity also appeared to influence risk, with the prevalence of IFG significantly lower in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic adolescents. However, increased HbA1c levels were significantly more prevalent in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic or non-Hispanic white adolescents.

“These findings highlight the need for additional studies on the long-term consequences and preventive strategies of abnormal glucose metabolism as measured by HbA1c levels in adolescents and young adults, especially of minority racial/ethnic groups,” the authors wrote.

Adolescents with prediabetes had significantly higher systolic blood pressure, non-HDL cholesterol, waist-to-height ratio, higher body mass index, and lower insulin sensitivity, compared with those with normal glucose tolerance. Among young adults with prediabetes, there was significantly higher systolic blood pressure and non-HDL cholesterol, compared with individuals with normal glucose tolerance.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Andes LJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Dec 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4498.

with a higher prevalence among males, a study has found.

Linda J. Andes, PhD, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors reported in JAMA Pediatrics their analysis of data from 2,606 adolescent (12-18 years) and 3,180 young adult (19-34 years) participants in the 2005-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

This found that the percentage with prediabetes – defined as either impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or increased hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level – was 18% among adolescents and 24% among young adults.

The most common condition was IFG, which was seen in 11% of adolescents and 16% of young adults. The rate of IGT was 4% in adolescents and 6% of young adults, while elevated HbA1c levels were seen in 5% of adolescents and 8% of young adults.

This information is important because “In adults, these three phenotypes increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote. “In 2011-2012, the overall prevalence of prediabetes among U.S. adults, defined as the presence of any of the three glucose metabolism dysregulation phenotypes, was 38% and it increased to about 50% in persons 65 years and older.”

Dr. Andes and associates noted that isolated IFG was the most common glucose dysregulation seen in both adolescents and young adults. “While individuals with IFG are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes, few primary prevention trials have included individuals selected for the presence of IFG and none have been conducted in adolescents with IFG or IGT to our knowledge.”

The study saw some key gender differences in prevalence. For example, the prevalence of IFG was significantly lower in adolescent girls than in boys (7% vs. 15%; P less than .001), and in young women, compared with young men (10% vs. 22%; P less than .001).

“These findings are consistent with those of other studies in adults; however, the underlying mechanisms for explaining this discrepancy are still unclear,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote.

Ethnicity also appeared to influence risk, with the prevalence of IFG significantly lower in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic adolescents. However, increased HbA1c levels were significantly more prevalent in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic or non-Hispanic white adolescents.

“These findings highlight the need for additional studies on the long-term consequences and preventive strategies of abnormal glucose metabolism as measured by HbA1c levels in adolescents and young adults, especially of minority racial/ethnic groups,” the authors wrote.

Adolescents with prediabetes had significantly higher systolic blood pressure, non-HDL cholesterol, waist-to-height ratio, higher body mass index, and lower insulin sensitivity, compared with those with normal glucose tolerance. Among young adults with prediabetes, there was significantly higher systolic blood pressure and non-HDL cholesterol, compared with individuals with normal glucose tolerance.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Andes LJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Dec 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4498.

with a higher prevalence among males, a study has found.

Linda J. Andes, PhD, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors reported in JAMA Pediatrics their analysis of data from 2,606 adolescent (12-18 years) and 3,180 young adult (19-34 years) participants in the 2005-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

This found that the percentage with prediabetes – defined as either impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or increased hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level – was 18% among adolescents and 24% among young adults.

The most common condition was IFG, which was seen in 11% of adolescents and 16% of young adults. The rate of IGT was 4% in adolescents and 6% of young adults, while elevated HbA1c levels were seen in 5% of adolescents and 8% of young adults.

This information is important because “In adults, these three phenotypes increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote. “In 2011-2012, the overall prevalence of prediabetes among U.S. adults, defined as the presence of any of the three glucose metabolism dysregulation phenotypes, was 38% and it increased to about 50% in persons 65 years and older.”

Dr. Andes and associates noted that isolated IFG was the most common glucose dysregulation seen in both adolescents and young adults. “While individuals with IFG are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes, few primary prevention trials have included individuals selected for the presence of IFG and none have been conducted in adolescents with IFG or IGT to our knowledge.”

The study saw some key gender differences in prevalence. For example, the prevalence of IFG was significantly lower in adolescent girls than in boys (7% vs. 15%; P less than .001), and in young women, compared with young men (10% vs. 22%; P less than .001).

“These findings are consistent with those of other studies in adults; however, the underlying mechanisms for explaining this discrepancy are still unclear,” Dr. Andes and coauthors wrote.

Ethnicity also appeared to influence risk, with the prevalence of IFG significantly lower in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic adolescents. However, increased HbA1c levels were significantly more prevalent in non-Hispanic black adolescents, compared with Hispanic or non-Hispanic white adolescents.

“These findings highlight the need for additional studies on the long-term consequences and preventive strategies of abnormal glucose metabolism as measured by HbA1c levels in adolescents and young adults, especially of minority racial/ethnic groups,” the authors wrote.

Adolescents with prediabetes had significantly higher systolic blood pressure, non-HDL cholesterol, waist-to-height ratio, higher body mass index, and lower insulin sensitivity, compared with those with normal glucose tolerance. Among young adults with prediabetes, there was significantly higher systolic blood pressure and non-HDL cholesterol, compared with individuals with normal glucose tolerance.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Andes LJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Dec 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4498.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

ART treatment at birth found to benefit neonates with HIV

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

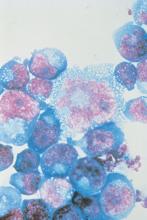

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

Initiating antiretroviral therapy within an hour after birth, rather than waiting a few weeks, lowers the reservoir of HIV virus and improves immune response, early results from an ongoing study in Botswana, Africa, showed.

Despite advances in treatment programs during pregnancy that prevent mother to child HIV transmission, 300-500 pediatric HIV infections occur each day in sub-Saharan Africa, Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, said during a media teleconference organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “Most pediatric HIV diagnosis programs currently test children at 4-6 weeks of age to identify infections that occur either in pregnancy or during delivery,” said Dr. Shapiro, associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “However, these programs miss the opportunity to begin immediate antiretroviral treatment for children who can be identified earlier. There are benefits to starting treatment and arresting HIV replication in the first week of life. These include limiting the viral reservoir or the population of infected cells, limiting potentially harmful immune responses to the virus, and preventing the rapid decline in health that can occur in the early weeks of HIV infection in infants. Without treatment, 50% of HIV-infected children regress to death by 2 years. Starting treatment in the first weeks or months of life has been shown to improve survival.”

With these benefits in mind, he and his associates initiated the Early Infant Treatment (EIT) study in 2015 to diagnose and treat HIV infected infants in Botswana in the first week of life or as early as possible after infection. They screened more than 10,000 children and identified 40 that were HIV infected. “This low transmission rate is a testament to the fact that most HIV-positive women in Botswana receive three-drug treatment in pregnancy, which is highly successful in blocking transmission,” Dr. Shapiro said. “When we identified an HIV-infected infant, we consented mothers to allow us to start treatment right away. We used a series of regimens because there are limited options. The available options include older drugs, some of which are no longer used for adults but which were the only options for children.”

The researchers initiated three initial drugs approved for newborns: nevirapine, zidovudine, and lamivudine, and then changed the regimen slightly after a few weeks, when they used ritonavir-boosted lopinavir, plus the lamivudine and zidovudine. “We followed the children weekly at first, then at monthly refill visits, and kept close track of how they were taking the medicines and the level of virus in each child’s blood,” Dr. Shapiro said.

In a manuscript published online in Science Translational Medicine on Nov. 27, 2019, he and his associates reported results of the first 10 children enrolled in the EIT study who reached about 96 weeks on treatment. For comparison, they also enrolled a group of children as controls, who started treatment later in the first year of life, after being identified at a more standard time of 4-6 weeks. Tests performed included droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, HIV near-full-genome sequencing, whole-genome amplification, and flow cytometry.

“What we wanted to focus on are the HIV reservoir cells that are persisting in the setting of antiretroviral treatment,” study coauthor Mathias Lichterfeld, MD, PhD, explained during the teleconference. “Those are the cells that would cause viral rebound if treatment were to be interrupted. We used complex technology to look at these cells, using next-generation sequencing, which allows us to identify those cells that harbor HIV that has the ability to initiate new viral replication.”

He and his colleagues observed that the number of reservoir cells was significantly smaller than in adults who were on ART for a median of 16 years. It also was smaller than in infected infants who started ART treatment weeks after birth.

In addition, immune activation was reduced in the cohort of infants who were treated immediately after birth.

“We are seeing a distinct advantage of early treatment initiation,” said Dr. Lichterfeld of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “By doing these assays we see both virological benefits in terms of a very-low reservoir size, and we see immune system characteristics that are also associated with better abilities for antimicrobial immune defense and a lower level of immune activation.”

Another study coauthor, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the infectious disease division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said the findings show “how critically important” it is to extend studies of HIV cure or long-term remission to infants and children. “Very-early intervention in neonates limits the size of the reservoir and offers us the best opportunity for future interventions aimed at cure and long-term drug-free remission of HIV infection,” he said. “We don’t think the current intervention is itself curative, but it sets the stage for the capacity to offer additional innovative interventions in the future. Beyond the importance of this work for cure research per se, this very early intervention in neonates also has the potential of conferring important clinical benefits to the children who participated in this study. Finally, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of doing this type of research in neonates in resource-limited settings, given the appropriate infrastructure.”

EIT is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

SOURCE: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Antiretroviral treatment initiation immediately after birth reduced HIV-1 viral reservoir size and alters innate immune responses in neonates.

Major finding: Very-early ART intervention in neonates infected with HIV limited the number of virally infected cells and improves immune response.

Study details: A cohort study of 10 infants infected with HIV who were born in Botswana, Africa.

Disclosures: The Early Infant Treatment study is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lichterfeld disclosed having received speaking and consulting honoraria from Merck and Gilead. Dr. Kuritzkes disclosed having received consulting honoraria and/or research support from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV.

Source: Garcia-Broncano P et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Nov 27. eaax7350.

FDA approves Tula system for recurrent pediatric ear infections

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Tubes Under Local Anesthesia (Tula) System for treatment of recurrent ear infections (otitis media) via tympanostomy in young children, according to a release from the agency.

Consisting of Tymbion anesthetic, tympanostomy tubes developed by Tusker Medical, and several devices that deliver them into the ear drum,

“This approval has the potential to expand patient access to a treatment that can be administered in a physician’s office with local anesthesia and minimal discomfort,” said Jeff Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The approval was based on data from 222 children treated with the device, with a procedural success rate of 86% in children under 5 years and 89% in children aged 5-12 years. The most common adverse event was insufficient anesthetic.

The system should not be used in children with allergies to some local anesthetics or those younger than 6 months. It also is not intended for patients with preexisting issues with their eardrums, such as perforated ear drums, according to the press release.

The Tula system was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, which means the FDA provided intensive engagement and guidance during its development. The full release can be found on the FDA website.

PHM19: MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

PHM19 session

MOC Part 4 projects for community pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Jack M. Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, MHM

Nancy Chen, MD, FAAP

Elizabeth Dobler, MD, FAAP

Lindsay Fox, MD

Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, SFHM

Clota Snow, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Jack Percelay, of Sutter Health in San Francisco, started this session at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 by outlining the process of submitting a small group (n = 1-10) project for Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit including the basics of what is needed for the application:

- Aim statement.

- Metrics used.

- Data required (3 data points: pre, post, and sustain).

He also shared the requirement of “meaningful participation” for participants to be eligible for MOC Part 4 credit.

Examples of successful projects were shared by members of the presenting group:

- Dr. Natt: Improving the timing of the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination.

- Dr. Dobler: Improving the hepatitis B vaccination rate within 24 hours of birth.

- Dr. Snow: Supplementing vitamin D in the newborn nursery.

- Dr. Fox: Improving newborn discharge efficiency, improving screening for smoking exposure, and offering smoking cessation.

- Dr. Percelay: Improving hospitalist billing and coding using time as a factor.

- Dr. Chen: Improving patient satisfaction through improvement of family-centered rounds.

The workshop audience divided into groups to brainstorm/troubleshoot projects and to elicit general advice regarding the process. Sample submissions were provided.

Key takeaways

- Even small projects (i.e. single metric) can be submitted/accepted with pre- and postintervention data.

- Be creative! Think about changes you are making at your institution and gather the data to support the intervention.

- Always double-dip on QI projects to gain valuable MOC Part 4 credit!

Dr. Fox is site director, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Division at MetroWest Medical Center, Framingham, Mass.

Obesity dropping in kids aged 2-4 years in WIC program

During 2010-2016, the prevalence of obesity among children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program significantly decreased in 73% of 56 states and territories, Liping Pan, MD, and colleagues reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The obesity prevalence decreases varied, but exceeded 3% in Guam, New Jersey, New Mexico, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Utah, and Virginia. Puerto Rico experienced the greatest benefit, with an 8% decrease in obesity among children aged 2-4 years enrolled in the WIC program, wrote Dr. Pan, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Although the changes were small, the positive trend gains more import when viewed in light of the country’s long-term obesity trends, Dr. Pan and his team wrote. After a short-lived dip during 2007-2012, obesity has been on the rise among these children, jumping from 8% in 2012 to 14% in 2016. “Thus, even these small decreases indicate progress for this vulnerable WIC population,” the team said.

WIC extends nutritional assistance to families whose income is 185% or less of the federal poverty guideline or are eligible for other programs, as well as being deemed at nutritional risk.

The current study looked at obesity trends during 2010-2016 among 12,403,629 WIC recipients aged 2-4 years in all 50 U.S. states and five territories.

In 2010, obesity prevalence ranged from a low of 10% in Colorado to a high of 22% in Virginia. In Alaska, Puerto Rico, and Virginia, it was 20% or higher. Only in Colorado and Hawaii was obesity prevalence 10% or less among these children.

By 2016, obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years ranged from 8% in the Northern Mariana Islands to 19.8% in Alaska. It was less than 20% in all the states and territories, and less than 10% in Colorado, Guam, Hawaii, Northern Mariana Islands, Utah, and Wyoming.

It increased during 2010-2016, however, in Alabama (0.5%), North Carolina (0.6%), and West Virginia (2.2%).

The changes reflect the 2009 program revisions made to adhere to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the infant food and feeding practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Pan and associates wrote.

“The revised food packages include a broader range of healthy food options; promote fruit, vegetable, and whole wheat product purchases; support breastfeeding; and give WIC state and territory agencies more flexibility to accommodate cultural food preferences,” the authors noted.

In response to the changes, Dr. Pan and associates noted, authorized WIC stores began carrying healthier offerings. Tracking showed that children in the program consumed more fruits, vegetables, and whole grain products and less juice, white bread, and whole milk after the revisions than they did previously.

Despite the good news, childhood obesity rates still are too high and much remains to be done, they noted.

“Multiple approaches are needed to address and eliminate childhood obesity. The National Academy of Medicine and other groups have recommended a comprehensive and integrated approach that calls for positive changes in physical activity and food and beverage environments in multiple settings including home, early care and education [such as nutrition standards for food served], and community [such as neighborhood designs that encourage walking and biking] to promote healthy eating and physical activity for young children. Further implementation of these positive changes across the United States could further the decreases in child-hood obesity,” Dr. Pan and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Pan and coauthors had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 22;68(46):1057-61.

During 2010-2016, the prevalence of obesity among children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program significantly decreased in 73% of 56 states and territories, Liping Pan, MD, and colleagues reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The obesity prevalence decreases varied, but exceeded 3% in Guam, New Jersey, New Mexico, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Utah, and Virginia. Puerto Rico experienced the greatest benefit, with an 8% decrease in obesity among children aged 2-4 years enrolled in the WIC program, wrote Dr. Pan, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Although the changes were small, the positive trend gains more import when viewed in light of the country’s long-term obesity trends, Dr. Pan and his team wrote. After a short-lived dip during 2007-2012, obesity has been on the rise among these children, jumping from 8% in 2012 to 14% in 2016. “Thus, even these small decreases indicate progress for this vulnerable WIC population,” the team said.

WIC extends nutritional assistance to families whose income is 185% or less of the federal poverty guideline or are eligible for other programs, as well as being deemed at nutritional risk.

The current study looked at obesity trends during 2010-2016 among 12,403,629 WIC recipients aged 2-4 years in all 50 U.S. states and five territories.

In 2010, obesity prevalence ranged from a low of 10% in Colorado to a high of 22% in Virginia. In Alaska, Puerto Rico, and Virginia, it was 20% or higher. Only in Colorado and Hawaii was obesity prevalence 10% or less among these children.

By 2016, obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years ranged from 8% in the Northern Mariana Islands to 19.8% in Alaska. It was less than 20% in all the states and territories, and less than 10% in Colorado, Guam, Hawaii, Northern Mariana Islands, Utah, and Wyoming.

It increased during 2010-2016, however, in Alabama (0.5%), North Carolina (0.6%), and West Virginia (2.2%).

The changes reflect the 2009 program revisions made to adhere to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the infant food and feeding practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Pan and associates wrote.

“The revised food packages include a broader range of healthy food options; promote fruit, vegetable, and whole wheat product purchases; support breastfeeding; and give WIC state and territory agencies more flexibility to accommodate cultural food preferences,” the authors noted.

In response to the changes, Dr. Pan and associates noted, authorized WIC stores began carrying healthier offerings. Tracking showed that children in the program consumed more fruits, vegetables, and whole grain products and less juice, white bread, and whole milk after the revisions than they did previously.

Despite the good news, childhood obesity rates still are too high and much remains to be done, they noted.

“Multiple approaches are needed to address and eliminate childhood obesity. The National Academy of Medicine and other groups have recommended a comprehensive and integrated approach that calls for positive changes in physical activity and food and beverage environments in multiple settings including home, early care and education [such as nutrition standards for food served], and community [such as neighborhood designs that encourage walking and biking] to promote healthy eating and physical activity for young children. Further implementation of these positive changes across the United States could further the decreases in child-hood obesity,” Dr. Pan and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Pan and coauthors had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 22;68(46):1057-61.

During 2010-2016, the prevalence of obesity among children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program significantly decreased in 73% of 56 states and territories, Liping Pan, MD, and colleagues reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The obesity prevalence decreases varied, but exceeded 3% in Guam, New Jersey, New Mexico, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Utah, and Virginia. Puerto Rico experienced the greatest benefit, with an 8% decrease in obesity among children aged 2-4 years enrolled in the WIC program, wrote Dr. Pan, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Although the changes were small, the positive trend gains more import when viewed in light of the country’s long-term obesity trends, Dr. Pan and his team wrote. After a short-lived dip during 2007-2012, obesity has been on the rise among these children, jumping from 8% in 2012 to 14% in 2016. “Thus, even these small decreases indicate progress for this vulnerable WIC population,” the team said.

WIC extends nutritional assistance to families whose income is 185% or less of the federal poverty guideline or are eligible for other programs, as well as being deemed at nutritional risk.

The current study looked at obesity trends during 2010-2016 among 12,403,629 WIC recipients aged 2-4 years in all 50 U.S. states and five territories.

In 2010, obesity prevalence ranged from a low of 10% in Colorado to a high of 22% in Virginia. In Alaska, Puerto Rico, and Virginia, it was 20% or higher. Only in Colorado and Hawaii was obesity prevalence 10% or less among these children.

By 2016, obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years ranged from 8% in the Northern Mariana Islands to 19.8% in Alaska. It was less than 20% in all the states and territories, and less than 10% in Colorado, Guam, Hawaii, Northern Mariana Islands, Utah, and Wyoming.

It increased during 2010-2016, however, in Alabama (0.5%), North Carolina (0.6%), and West Virginia (2.2%).

The changes reflect the 2009 program revisions made to adhere to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the infant food and feeding practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Pan and associates wrote.

“The revised food packages include a broader range of healthy food options; promote fruit, vegetable, and whole wheat product purchases; support breastfeeding; and give WIC state and territory agencies more flexibility to accommodate cultural food preferences,” the authors noted.

In response to the changes, Dr. Pan and associates noted, authorized WIC stores began carrying healthier offerings. Tracking showed that children in the program consumed more fruits, vegetables, and whole grain products and less juice, white bread, and whole milk after the revisions than they did previously.

Despite the good news, childhood obesity rates still are too high and much remains to be done, they noted.

“Multiple approaches are needed to address and eliminate childhood obesity. The National Academy of Medicine and other groups have recommended a comprehensive and integrated approach that calls for positive changes in physical activity and food and beverage environments in multiple settings including home, early care and education [such as nutrition standards for food served], and community [such as neighborhood designs that encourage walking and biking] to promote healthy eating and physical activity for young children. Further implementation of these positive changes across the United States could further the decreases in child-hood obesity,” Dr. Pan and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Pan and coauthors had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 22;68(46):1057-61.

FROM THE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Managing pain in kids during minor procedures: A tricky balance

NEW ORLEANS – Baruch S. Krauss, MD, EdM said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Krauss, a pediatric emergency physician at Boston Children’s Hospital, shared tips for producing a positive experience when children present for minor procedures such as an intravenous catheter insertion or a laceration repair.

Control the environment

Setting the stage for a positive experience for children and their parents involves decreasing sensory stimuli by minimizing noise and bustle, the number of people in the room, and the reminder cues. “Even if you have trust with the child, there are certain things that could trigger the child to become fearful and anxious,” said Dr. Krauss, who also holds an academic post in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “You want to make sure that medical equipment or a syringe is covered – anything that would remind the child or trigger the child to be more concerned and anxious.”

He recommends careful use of lighting, particularly in children who present with a head laceration or a facial laceration. “You may need to put a light near the wound, but that may be fearful for the child,” said Dr. Krauss, who coauthored a recent article on the topic that contains links to instructional videos (Ann Emerg Med 2019;74[1]:30-5). “Read the cues of the child,” he said. One desensitization technique he uses in such cases is to tell the child a story about the sun. He then goes on to liken the warmth of the exam light to the warmth of the sun.

Limiting the number of clinicians who speak to the child during the procedure also is key. “One person should speak to the child,” he advised. “Otherwise, it creates confusion for the child and it is hard for them to focus their attention. What you really want is to be able to control the child’s attention. You want to be able to capture their attention.”

It’s also important to keep medical equipment out of view. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen consultants come in and a child needs to have a laceration repair, and they’re filling the syringe with lidocaine in front of the child,” Dr. Krauss said. “You want to avoid that. You also want to work outside of the child’s visual field if you can. Positioning is critical. I will try whatever position works for the child and the family.” This may including asking the parent to hold and swaddle an infant during the procedure, or positioning young children in the parent’s lap with their arm secured.

“Two things that upset kids during laceration repair are water dripping into their eyes during irrigation and the suture falling across their face as you’re stitching,” he added. “You want to develop your procedural skills so you can avoid that happening.”

Tailor the approach to the individual child

Some children will want to watch what you’re doing, but normally Dr. Krauss uses towels or blankets to cover the area being worked on. “If the child is part of your practice and you know his temperament and coping style, that makes it a lot easier; you know how to approach him,” he said. “They can trust you but they still can be quite fearful.” Sometimes, the child is relaxed but the parent becomes anxious. That anxiety can be transmitted to child. “If I see that the parents are anxious, I work directly with the child, and not the parent,” he said. “There’s not much I can tell a parent verbally that’s going to change their anxiety or fear level. But, as soon I start moving the child’s emotional state from fear to trust, the parent senses that and they relax, and that gets transmitted back to the child.”

Use age-appropriate language

When treating infants and children, Dr. Krauss often uses “parentese,” a simplified way that parents use to talk to young children. “It’s clearer, simpler, more attention-maintaining, and has longer pauses,” he said. “That can be very comforting to children.” Content and phrasing become important in older children. “You want to avoid the nocebo effect,” he continued. “If you tell a child, ‘This is really going to sting or hurt,’ you’re tipping the scales toward them having that experience.”

In an article about behavioral approaches to anxiety and pain management for pediatric venous access, Lindsey L. Cohen, PhD, devised a list of suggested phrasing to use. For example, instead of saying “You will be fine; there is nothing to worry about,” ask, “What did you do in school today?” as a form of distraction. Instead of saying, “It will feel like a bee sting,” ask, “Tell me how it feels.” And instead of saying, “Don’t cry,” say, “That was hard; I am proud of you” (Pediatrics 2008;122[suppl 3]:S134-9).

In a more recent article, Dr. Krauss and colleagues discussed current concepts of managing pain in children who present to the emergency department (Lancet 2016;387:83-92). Among distracting activities to try with infants and preschoolers are blowing bubbles, the use of a lighted wand, sound, music, or books, they noted. Distracting activities to try with preschoolers and in older children include art activities such as drawing, coloring, and the use of play dough, and computer games.

Clinicians also can ask the child to engage in a developmental task as a form of distraction. Dr. Krauss recalled a 22-month-old boy who presented to the emergency department with a forehead laceration. Mindful that the boy was developing eye-hand coordination and fine motor activity, Dr. Krauss offered him a coloring book that contained a picture of a clown, and instructed him to color the clown’s eyes red while Dr. Krauss tended to the wound. “His attention was completely fixed on that learning task,” he said.

Dr. Krauss reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Baruch S. Krauss, MD, EdM said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Krauss, a pediatric emergency physician at Boston Children’s Hospital, shared tips for producing a positive experience when children present for minor procedures such as an intravenous catheter insertion or a laceration repair.

Control the environment

Setting the stage for a positive experience for children and their parents involves decreasing sensory stimuli by minimizing noise and bustle, the number of people in the room, and the reminder cues. “Even if you have trust with the child, there are certain things that could trigger the child to become fearful and anxious,” said Dr. Krauss, who also holds an academic post in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “You want to make sure that medical equipment or a syringe is covered – anything that would remind the child or trigger the child to be more concerned and anxious.”

He recommends careful use of lighting, particularly in children who present with a head laceration or a facial laceration. “You may need to put a light near the wound, but that may be fearful for the child,” said Dr. Krauss, who coauthored a recent article on the topic that contains links to instructional videos (Ann Emerg Med 2019;74[1]:30-5). “Read the cues of the child,” he said. One desensitization technique he uses in such cases is to tell the child a story about the sun. He then goes on to liken the warmth of the exam light to the warmth of the sun.

Limiting the number of clinicians who speak to the child during the procedure also is key. “One person should speak to the child,” he advised. “Otherwise, it creates confusion for the child and it is hard for them to focus their attention. What you really want is to be able to control the child’s attention. You want to be able to capture their attention.”

It’s also important to keep medical equipment out of view. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen consultants come in and a child needs to have a laceration repair, and they’re filling the syringe with lidocaine in front of the child,” Dr. Krauss said. “You want to avoid that. You also want to work outside of the child’s visual field if you can. Positioning is critical. I will try whatever position works for the child and the family.” This may including asking the parent to hold and swaddle an infant during the procedure, or positioning young children in the parent’s lap with their arm secured.

“Two things that upset kids during laceration repair are water dripping into their eyes during irrigation and the suture falling across their face as you’re stitching,” he added. “You want to develop your procedural skills so you can avoid that happening.”

Tailor the approach to the individual child

Some children will want to watch what you’re doing, but normally Dr. Krauss uses towels or blankets to cover the area being worked on. “If the child is part of your practice and you know his temperament and coping style, that makes it a lot easier; you know how to approach him,” he said. “They can trust you but they still can be quite fearful.” Sometimes, the child is relaxed but the parent becomes anxious. That anxiety can be transmitted to child. “If I see that the parents are anxious, I work directly with the child, and not the parent,” he said. “There’s not much I can tell a parent verbally that’s going to change their anxiety or fear level. But, as soon I start moving the child’s emotional state from fear to trust, the parent senses that and they relax, and that gets transmitted back to the child.”

Use age-appropriate language

When treating infants and children, Dr. Krauss often uses “parentese,” a simplified way that parents use to talk to young children. “It’s clearer, simpler, more attention-maintaining, and has longer pauses,” he said. “That can be very comforting to children.” Content and phrasing become important in older children. “You want to avoid the nocebo effect,” he continued. “If you tell a child, ‘This is really going to sting or hurt,’ you’re tipping the scales toward them having that experience.”

In an article about behavioral approaches to anxiety and pain management for pediatric venous access, Lindsey L. Cohen, PhD, devised a list of suggested phrasing to use. For example, instead of saying “You will be fine; there is nothing to worry about,” ask, “What did you do in school today?” as a form of distraction. Instead of saying, “It will feel like a bee sting,” ask, “Tell me how it feels.” And instead of saying, “Don’t cry,” say, “That was hard; I am proud of you” (Pediatrics 2008;122[suppl 3]:S134-9).

In a more recent article, Dr. Krauss and colleagues discussed current concepts of managing pain in children who present to the emergency department (Lancet 2016;387:83-92). Among distracting activities to try with infants and preschoolers are blowing bubbles, the use of a lighted wand, sound, music, or books, they noted. Distracting activities to try with preschoolers and in older children include art activities such as drawing, coloring, and the use of play dough, and computer games.

Clinicians also can ask the child to engage in a developmental task as a form of distraction. Dr. Krauss recalled a 22-month-old boy who presented to the emergency department with a forehead laceration. Mindful that the boy was developing eye-hand coordination and fine motor activity, Dr. Krauss offered him a coloring book that contained a picture of a clown, and instructed him to color the clown’s eyes red while Dr. Krauss tended to the wound. “His attention was completely fixed on that learning task,” he said.

Dr. Krauss reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Baruch S. Krauss, MD, EdM said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Krauss, a pediatric emergency physician at Boston Children’s Hospital, shared tips for producing a positive experience when children present for minor procedures such as an intravenous catheter insertion or a laceration repair.

Control the environment

Setting the stage for a positive experience for children and their parents involves decreasing sensory stimuli by minimizing noise and bustle, the number of people in the room, and the reminder cues. “Even if you have trust with the child, there are certain things that could trigger the child to become fearful and anxious,” said Dr. Krauss, who also holds an academic post in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “You want to make sure that medical equipment or a syringe is covered – anything that would remind the child or trigger the child to be more concerned and anxious.”

He recommends careful use of lighting, particularly in children who present with a head laceration or a facial laceration. “You may need to put a light near the wound, but that may be fearful for the child,” said Dr. Krauss, who coauthored a recent article on the topic that contains links to instructional videos (Ann Emerg Med 2019;74[1]:30-5). “Read the cues of the child,” he said. One desensitization technique he uses in such cases is to tell the child a story about the sun. He then goes on to liken the warmth of the exam light to the warmth of the sun.

Limiting the number of clinicians who speak to the child during the procedure also is key. “One person should speak to the child,” he advised. “Otherwise, it creates confusion for the child and it is hard for them to focus their attention. What you really want is to be able to control the child’s attention. You want to be able to capture their attention.”

It’s also important to keep medical equipment out of view. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen consultants come in and a child needs to have a laceration repair, and they’re filling the syringe with lidocaine in front of the child,” Dr. Krauss said. “You want to avoid that. You also want to work outside of the child’s visual field if you can. Positioning is critical. I will try whatever position works for the child and the family.” This may including asking the parent to hold and swaddle an infant during the procedure, or positioning young children in the parent’s lap with their arm secured.

“Two things that upset kids during laceration repair are water dripping into their eyes during irrigation and the suture falling across their face as you’re stitching,” he added. “You want to develop your procedural skills so you can avoid that happening.”

Tailor the approach to the individual child

Some children will want to watch what you’re doing, but normally Dr. Krauss uses towels or blankets to cover the area being worked on. “If the child is part of your practice and you know his temperament and coping style, that makes it a lot easier; you know how to approach him,” he said. “They can trust you but they still can be quite fearful.” Sometimes, the child is relaxed but the parent becomes anxious. That anxiety can be transmitted to child. “If I see that the parents are anxious, I work directly with the child, and not the parent,” he said. “There’s not much I can tell a parent verbally that’s going to change their anxiety or fear level. But, as soon I start moving the child’s emotional state from fear to trust, the parent senses that and they relax, and that gets transmitted back to the child.”

Use age-appropriate language

When treating infants and children, Dr. Krauss often uses “parentese,” a simplified way that parents use to talk to young children. “It’s clearer, simpler, more attention-maintaining, and has longer pauses,” he said. “That can be very comforting to children.” Content and phrasing become important in older children. “You want to avoid the nocebo effect,” he continued. “If you tell a child, ‘This is really going to sting or hurt,’ you’re tipping the scales toward them having that experience.”

In an article about behavioral approaches to anxiety and pain management for pediatric venous access, Lindsey L. Cohen, PhD, devised a list of suggested phrasing to use. For example, instead of saying “You will be fine; there is nothing to worry about,” ask, “What did you do in school today?” as a form of distraction. Instead of saying, “It will feel like a bee sting,” ask, “Tell me how it feels.” And instead of saying, “Don’t cry,” say, “That was hard; I am proud of you” (Pediatrics 2008;122[suppl 3]:S134-9).

In a more recent article, Dr. Krauss and colleagues discussed current concepts of managing pain in children who present to the emergency department (Lancet 2016;387:83-92). Among distracting activities to try with infants and preschoolers are blowing bubbles, the use of a lighted wand, sound, music, or books, they noted. Distracting activities to try with preschoolers and in older children include art activities such as drawing, coloring, and the use of play dough, and computer games.

Clinicians also can ask the child to engage in a developmental task as a form of distraction. Dr. Krauss recalled a 22-month-old boy who presented to the emergency department with a forehead laceration. Mindful that the boy was developing eye-hand coordination and fine motor activity, Dr. Krauss offered him a coloring book that contained a picture of a clown, and instructed him to color the clown’s eyes red while Dr. Krauss tended to the wound. “His attention was completely fixed on that learning task,” he said.

Dr. Krauss reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AAP 19

Inexperience is the main cause of unsafe driving among teens

NEW ORLEANS – Teens need to drive for a wide range of reasons, from going to and from school or work to overall mobility, but driving still is the most dangerous thing teenagers do, according to Brian Johnston, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Motor vehicle traffic accidents continue to be the leading cause of death of adolescents aged 15-19 years, according to 2017 data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for the Disease Control and Prevention.

“Inexperience drives the statistics we see,” Dr. Johnston said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “There is a steep learning curve among drivers of all ages, and crash rates are highest during the first few months after teens begin driving without supervision.”

Although the risk of accidents is higher than average for any new driver, it’s disproportionately higher for younger teens, compared with other ages: 16-year-old novice drivers have a higher accident risk than that of 17-year-olds, whose risk is similar to that of 18- and 19-year-old novices.

How long drivers have been licensed has a far bigger impact on crash risk, Dr. Johnston said (Traffic Inj. Prev. 2009 Jun;10[3]:209-19).

But the risk of an accident also increases with each additional passenger a teen driver has, particularly for younger and male drivers (Traffic Inj Prev. 2013;14[3]:283-92). More passengers likely means more distraction, and distraction, driving too fast for road conditions, and not scanning the roadway are the three most common errors – together accounting for about half of all teen drivers’ crashes.

Risk factors for accidents

Speed is a contributing factor in just over a third (36%) of teens’ fatal crashes. Adolescents drive faster and keep shorter following distances than adults do. But as with adults, wearing seat belts substantially reduces the risk of death in accidents.

Nationally, 90% of drivers use seat belts, with higher rates in states with primary enforcement (92%) than those in states with secondary enforcement (83%).

But barely more than half (54%) of U.S. high school students say they “always” wear a seat belt, and just under half of teens (47%) who died in crashes in 2017 weren’t wearing one. As seen in adults, teens are more likely to buckle up, by 12%, in states with primary seat belt laws.

Distraction during driving can be visual, manual, or cognitive – and handheld electronic devices such as smartphones cause all three distraction types. Cell phones nearly double the proportion of teen drivers who die in crashes, from 7% to 13%.

But if teens can keep their eyes on the roadway at all times, even the risks posed by cellphones drop considerably.

“The best evidence shows that secondary tasks only degrade driving performance when they require drivers to look away from the road,” Dr. Johnston said. Looking away for 2 seconds or longer increases crash risk more than fivefold.

Two other risk factors for teen car accidents are drowsiness and nighttime driving. Sleepiness can play a role in crashes at any time of day, and Dr. Johnston noted that some research has associated later high school start times with reduced crash risk.

Teens aged 16-19 years are about four times more likely to have a car accident at night than during the day per each mile driven, the pediatrician noted. Many licensing laws restrict teen driving starting at 11 p.m. or later, but about 50%-60% of their crashes occur between 9 and 11 p.m.

One reason for the increased risk is less experience driving in more difficult conditions, but teens also are more likely to have teen passengers, to be driving excessively fast, or to be under the influence of alcohol at night.

Adolescents’ crash risk is higher than that of adults for any level of blood alcohol content. Self-reported driving after drinking dropped by almost half – from 10% to 5.5% – from 2013 to 2017, but alcohol still is implicated in a substantial number of fatal teen crashes.

As drunk driving has declined, however, driving while under the influence of marijuana has been increasing. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, case control studies show drivers with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in their blood have a 25% increased risk of accidents – but the excess risk associated with THC vanishes when researchers control for age, sex, and concurrent use of alcohol. Not enough research exists to determine what the crash risk would be for adolescent drivers using THC alone.

A less-recognized risk factor for car accidents in teen drivers is ADHD, which increases a teen’s risk of crashing by 36%, particularly in the first month after getting a license, Dr. Johnston said.

ADHD medication appears to mitigate the danger, according to data: Crash risk was 40% lower in adult drivers with ADHD during months they filled their stimulant prescriptions. But one study found only 12% of teens with ADHD filled their prescriptions the month they got their license, and adolescents may not take their medications or still have them in their system on weekends or at night.