User login

Does using e-cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in adolescents?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 9 prospective cohort studies (total 17,389 patients) at least 6 months in duration evaluated the association between e-cigarette exposure and subsequent cigarette smoking in adolescents and young adults.1 It found that smoking was more prevalent in ever-users of e-cigarettes than nonusers at 1 year (23.3% vs 7.2%; odds ratio [OR] = 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.38-5.16). The association was even stronger among recent users (within 30 days) of e-cigarettes compared with nonusers (21.5% vs 4.6%; OR = 4.28; 95% CI, 2.52-7.27). The mean age of approximately 80% of participants was 20 years or younger.

Further studies also support a link between e-cigarette and cigarette use

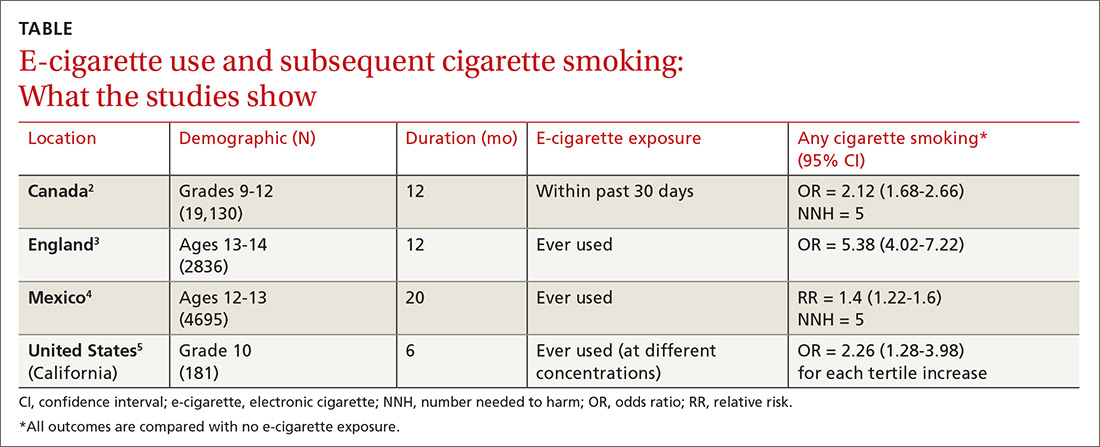

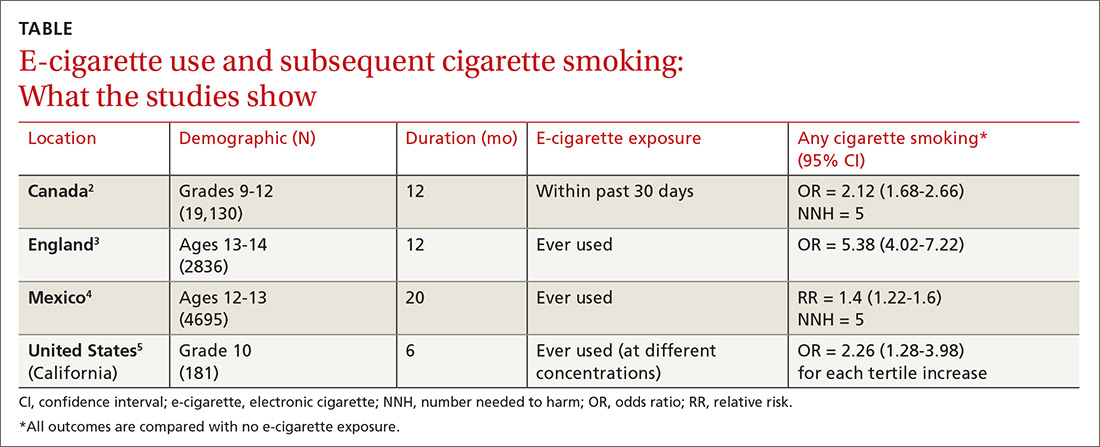

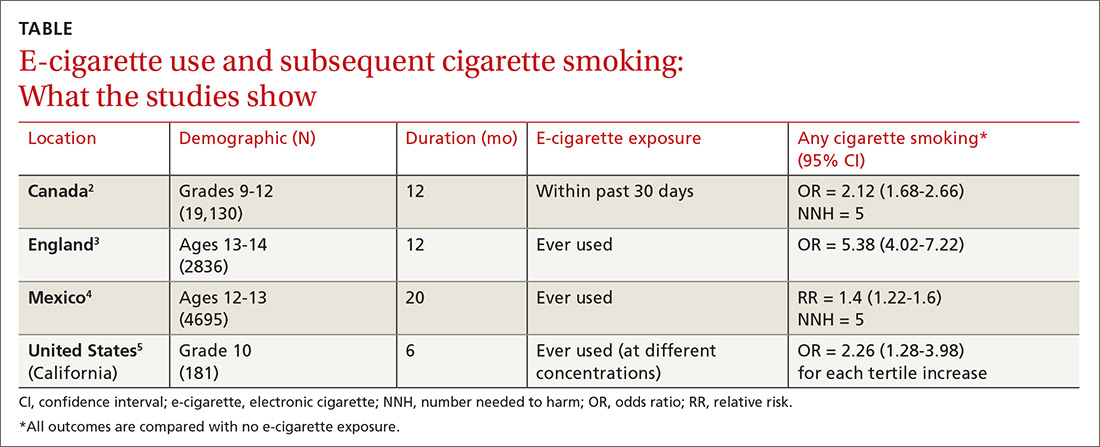

Four subsequent cohort studies also found links between e-cigarette exposure and any level of cigarette smoking (TABLE).2-5 A Canadian study of high school students reported a positive association between recent e-cigarette use (within the previous 30 days) and subsequent daily cigarette usage (OR = 1.79; 95% CI, 1.41-2.28).2 A British study that documented the largest association uniquely validated smoking status with carbon monoxide testing.3 A study of Mexican adolescents found that adolescents who tried e-cigarettes were more likely to smoke cigarettes and also reported an association between e-cigarette use and marijuana use (relative risk [RR] = 1.93; 95% CI, 1.14–3.28).4 A California study that evaluated e-cigarette nicotine level and subsequent cigarette smoking found a dose-dependent response, suggesting an association between nicotine concentration and subsequent uptake of cigarettes.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

A policy statement from The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Tobacco Control states that youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to use cigarettes and other tobacco products.6 It recommends that physicians screen patients for use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), counsel about immediate and long-term harms and the importance of not using ENDS, and offer current users tobacco cessation counseling (with Food and Drug Administration-approved tobacco dependence treatment).

Editor’s takeaway

While these cohort studies don’t definitively prove causation, they provide the best quality evidence that we are likely to see in support of counseling adolescents against using e-cigarettes, educating them about harms, and offering tobacco cessation measures when appropriate.

1. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Willis TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797.

2. Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, et al. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1328-E1336.

3. Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, et al. Do electronic cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in UK adolescents? Evidence from a 12-month prospective study. Tob Control. 2018;27:365-372.

4. Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:427-430.

5. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, et al. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1192-1199.

6. Walley SC, Jenssen BP; Section on Tobacco Control. Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1018-1026.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 9 prospective cohort studies (total 17,389 patients) at least 6 months in duration evaluated the association between e-cigarette exposure and subsequent cigarette smoking in adolescents and young adults.1 It found that smoking was more prevalent in ever-users of e-cigarettes than nonusers at 1 year (23.3% vs 7.2%; odds ratio [OR] = 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.38-5.16). The association was even stronger among recent users (within 30 days) of e-cigarettes compared with nonusers (21.5% vs 4.6%; OR = 4.28; 95% CI, 2.52-7.27). The mean age of approximately 80% of participants was 20 years or younger.

Further studies also support a link between e-cigarette and cigarette use

Four subsequent cohort studies also found links between e-cigarette exposure and any level of cigarette smoking (TABLE).2-5 A Canadian study of high school students reported a positive association between recent e-cigarette use (within the previous 30 days) and subsequent daily cigarette usage (OR = 1.79; 95% CI, 1.41-2.28).2 A British study that documented the largest association uniquely validated smoking status with carbon monoxide testing.3 A study of Mexican adolescents found that adolescents who tried e-cigarettes were more likely to smoke cigarettes and also reported an association between e-cigarette use and marijuana use (relative risk [RR] = 1.93; 95% CI, 1.14–3.28).4 A California study that evaluated e-cigarette nicotine level and subsequent cigarette smoking found a dose-dependent response, suggesting an association between nicotine concentration and subsequent uptake of cigarettes.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

A policy statement from The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Tobacco Control states that youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to use cigarettes and other tobacco products.6 It recommends that physicians screen patients for use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), counsel about immediate and long-term harms and the importance of not using ENDS, and offer current users tobacco cessation counseling (with Food and Drug Administration-approved tobacco dependence treatment).

Editor’s takeaway

While these cohort studies don’t definitively prove causation, they provide the best quality evidence that we are likely to see in support of counseling adolescents against using e-cigarettes, educating them about harms, and offering tobacco cessation measures when appropriate.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 9 prospective cohort studies (total 17,389 patients) at least 6 months in duration evaluated the association between e-cigarette exposure and subsequent cigarette smoking in adolescents and young adults.1 It found that smoking was more prevalent in ever-users of e-cigarettes than nonusers at 1 year (23.3% vs 7.2%; odds ratio [OR] = 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.38-5.16). The association was even stronger among recent users (within 30 days) of e-cigarettes compared with nonusers (21.5% vs 4.6%; OR = 4.28; 95% CI, 2.52-7.27). The mean age of approximately 80% of participants was 20 years or younger.

Further studies also support a link between e-cigarette and cigarette use

Four subsequent cohort studies also found links between e-cigarette exposure and any level of cigarette smoking (TABLE).2-5 A Canadian study of high school students reported a positive association between recent e-cigarette use (within the previous 30 days) and subsequent daily cigarette usage (OR = 1.79; 95% CI, 1.41-2.28).2 A British study that documented the largest association uniquely validated smoking status with carbon monoxide testing.3 A study of Mexican adolescents found that adolescents who tried e-cigarettes were more likely to smoke cigarettes and also reported an association between e-cigarette use and marijuana use (relative risk [RR] = 1.93; 95% CI, 1.14–3.28).4 A California study that evaluated e-cigarette nicotine level and subsequent cigarette smoking found a dose-dependent response, suggesting an association between nicotine concentration and subsequent uptake of cigarettes.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

A policy statement from The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Tobacco Control states that youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to use cigarettes and other tobacco products.6 It recommends that physicians screen patients for use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), counsel about immediate and long-term harms and the importance of not using ENDS, and offer current users tobacco cessation counseling (with Food and Drug Administration-approved tobacco dependence treatment).

Editor’s takeaway

While these cohort studies don’t definitively prove causation, they provide the best quality evidence that we are likely to see in support of counseling adolescents against using e-cigarettes, educating them about harms, and offering tobacco cessation measures when appropriate.

1. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Willis TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797.

2. Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, et al. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1328-E1336.

3. Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, et al. Do electronic cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in UK adolescents? Evidence from a 12-month prospective study. Tob Control. 2018;27:365-372.

4. Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:427-430.

5. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, et al. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1192-1199.

6. Walley SC, Jenssen BP; Section on Tobacco Control. Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1018-1026.

1. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Willis TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797.

2. Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, et al. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1328-E1336.

3. Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, et al. Do electronic cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in UK adolescents? Evidence from a 12-month prospective study. Tob Control. 2018;27:365-372.

4. Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:427-430.

5. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, et al. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1192-1199.

6. Walley SC, Jenssen BP; Section on Tobacco Control. Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1018-1026.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably. Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use by adolescents is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in cigarette smoking over the next year (strength of recommendation: A, meta-analysis and subsequent prospective cohort studies).

Infant with bilious emesis

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

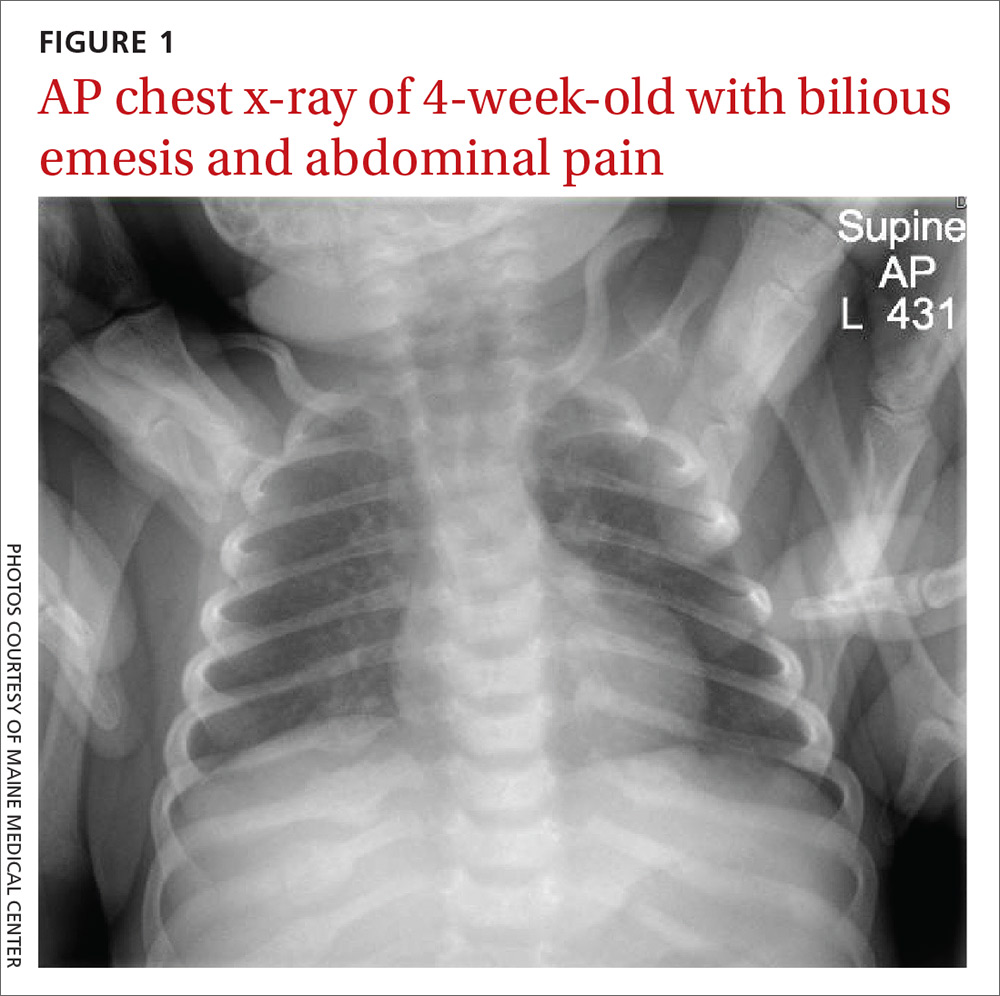

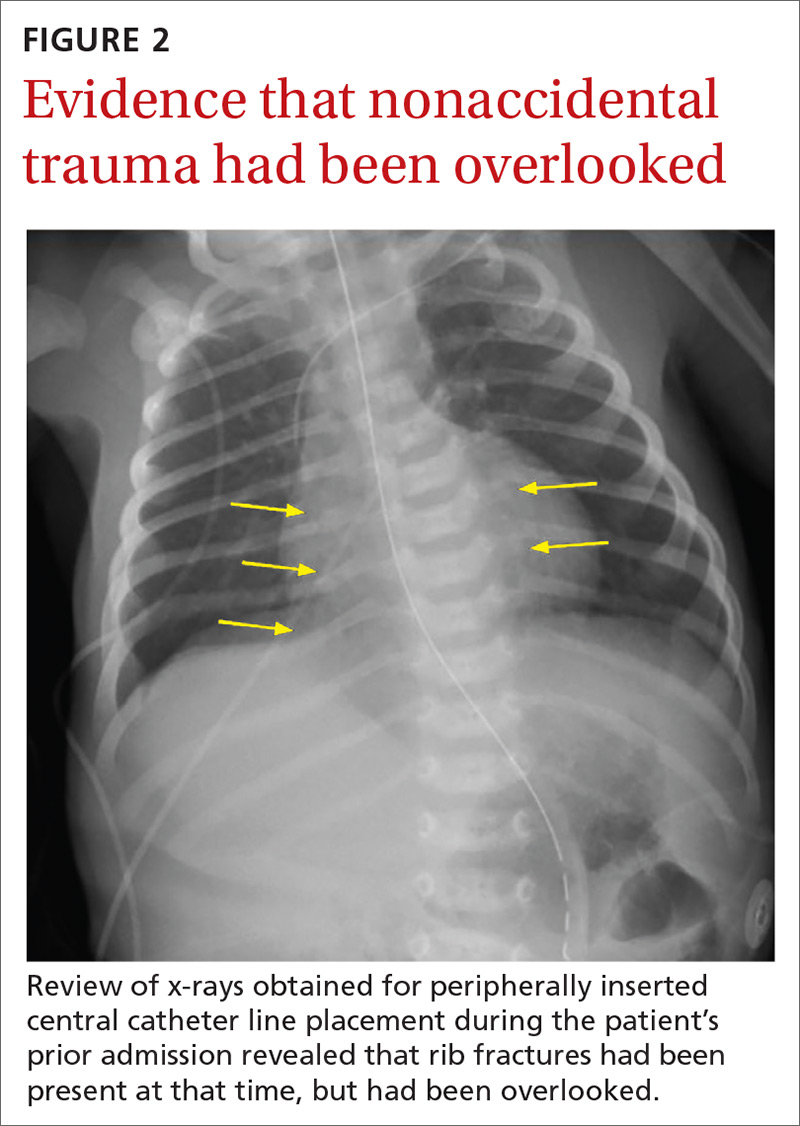

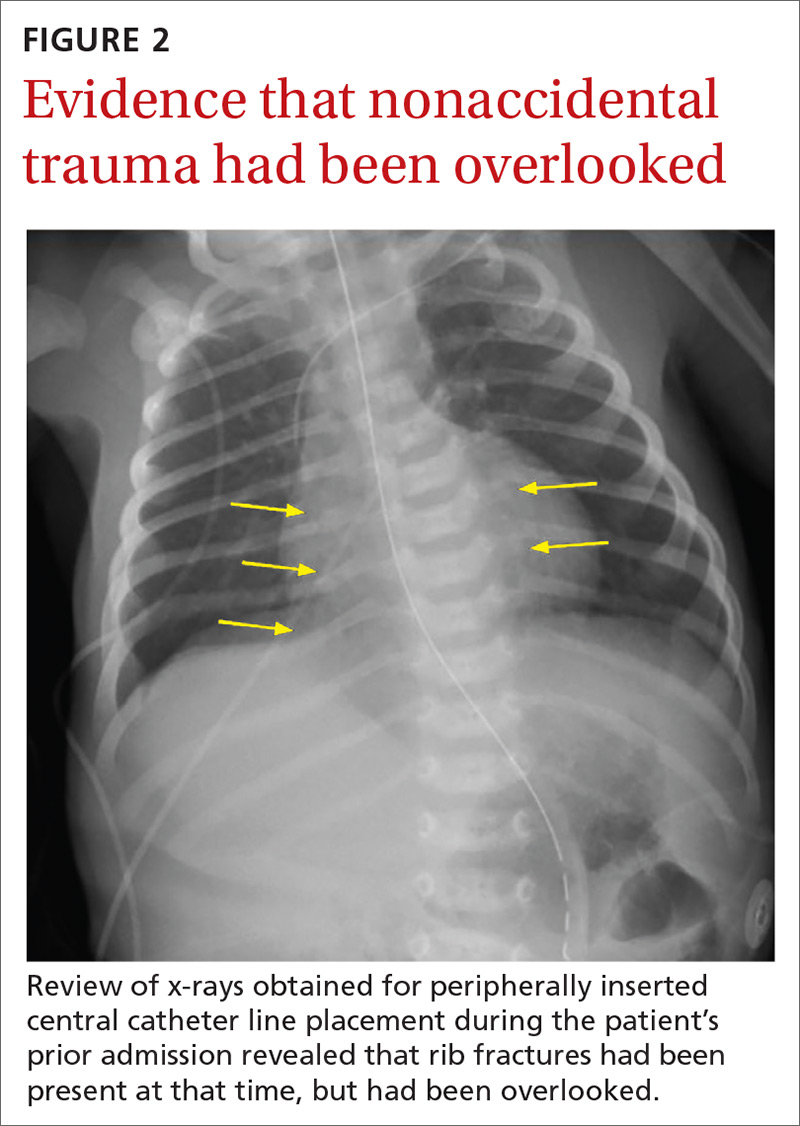

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

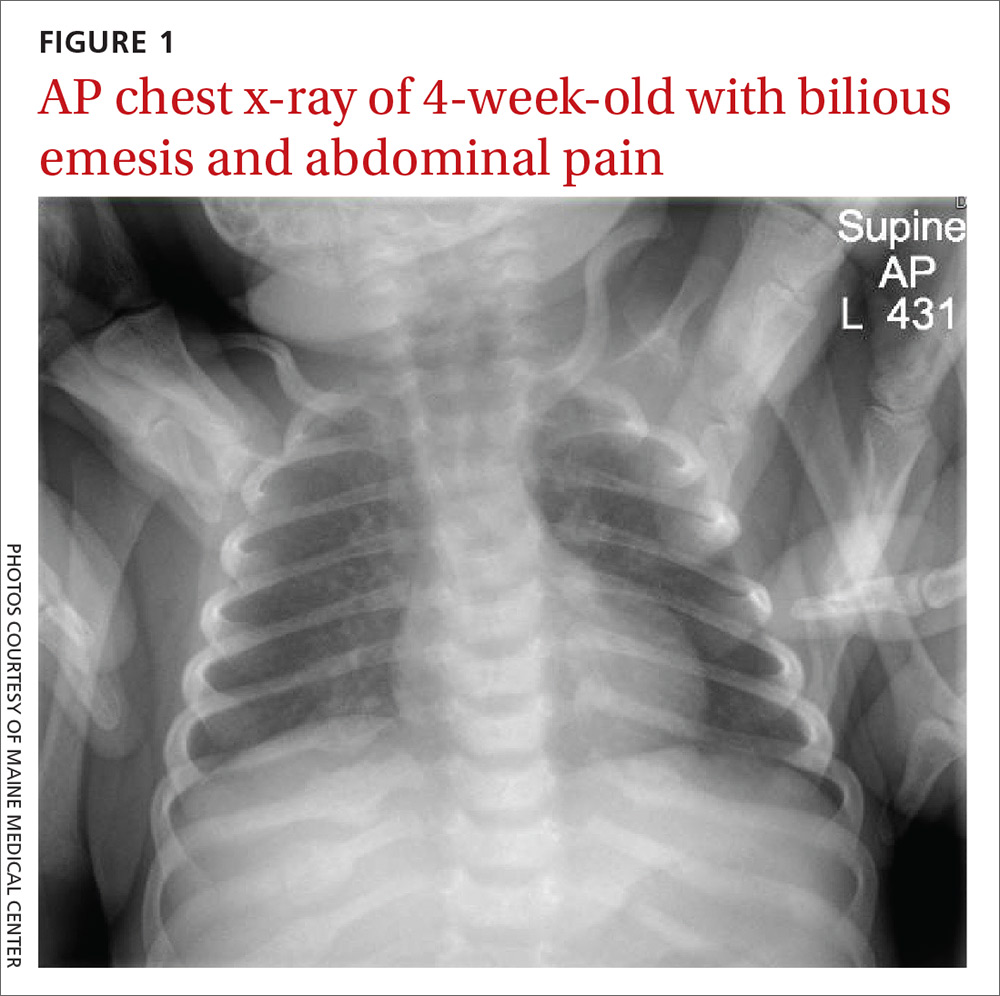

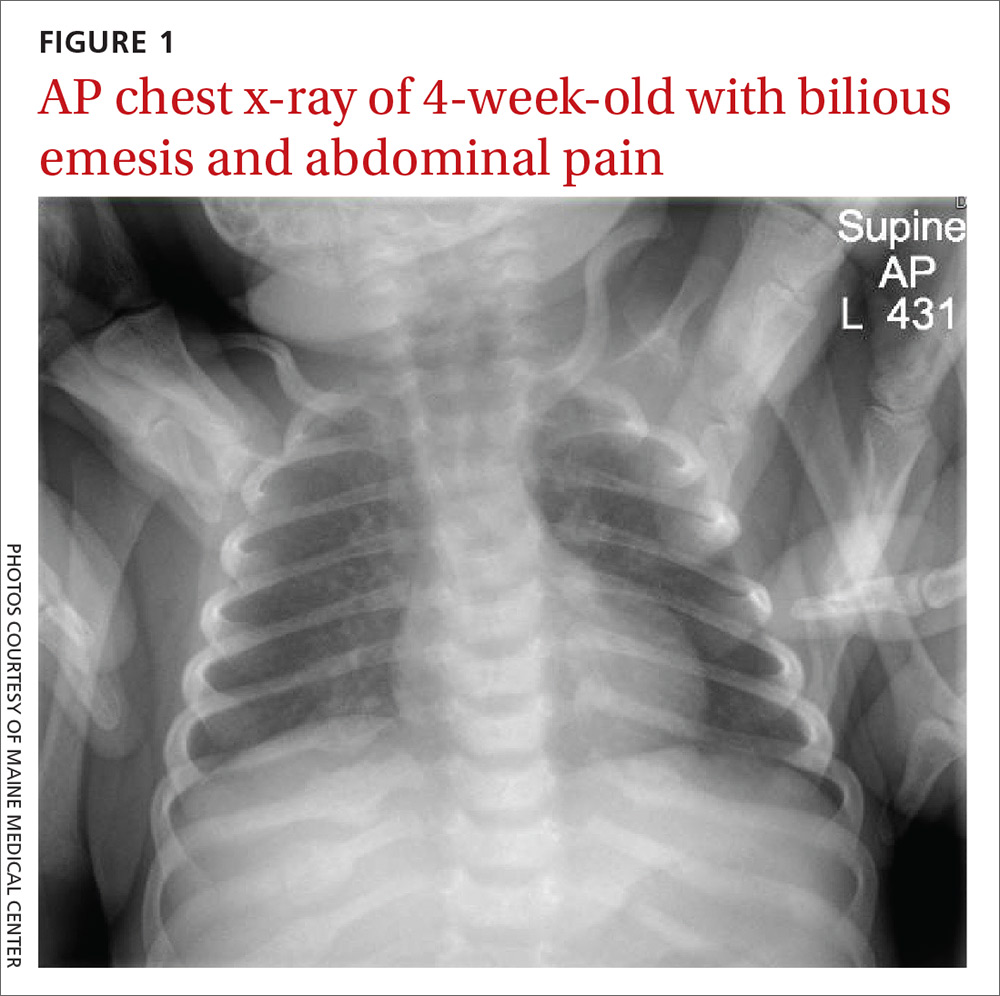

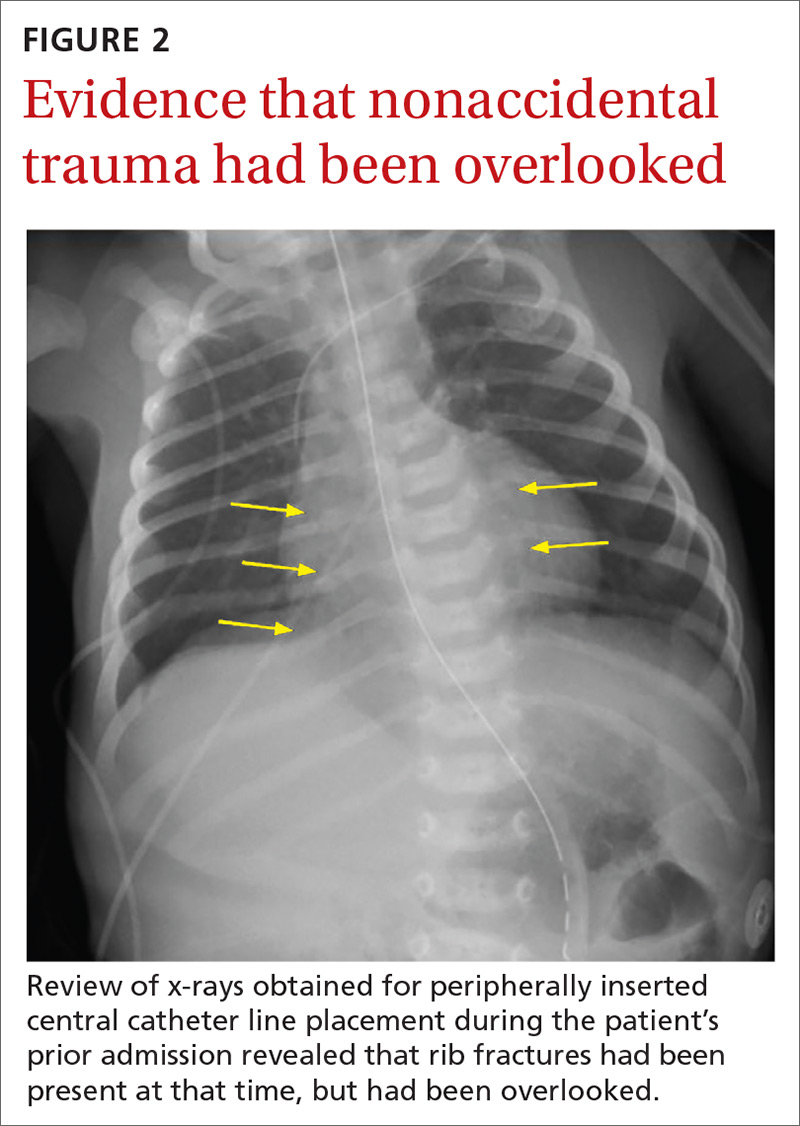

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

Fragmentation of sickle cell disease care starts in young adulthood

ORLANDO – While over time, results of a retrospective study suggest.

Nearly 60% of children between aged10-17 years were seen at just one facility over the course of 7 years in the analysis, which was based on analysis of data for nearly 7,000 patients seen in California during 1991-2016.

That contrasted sharply with young adults, aged 18-25 years, only about 20% of whom were admitted to one facility, said senior study author Anjlee Mahajan, MD, of the University of California, Davis, adding that another 20% were seen at five or more centers over a 7-year follow-up period.

Fragmentation of care didn’t increase the risk of death in this study, as investigators hypothesized it might. However, the outcomes and the quality of care among young adults with SCD who received inpatient care at multiple facilities nevertheless was likely to be affected, Dr. Mahajan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Imagine what that would be like to have a chronic, debilitating illness and to have to go to multiple different hospitals, during this vulnerable time period in your life, and being seen by different care providers who may not know you and may not have all of your records as well,” she said in a press conference at the meeting.

Providers and the health care system need to work harder to ensure young adults receive comprehensive and coordinated care, especially at a time when therapeutic advances are improving the treatment of this disease, according to the investigator.

“When you’re seen at one center, you can have a specific pain plan, and maybe when you are going into the emergency room and being admitted, your sickle cell care provider might come and visit you in the hospital or at least be in contact with your team,” Dr. Mahajan said in an interview. “That may not happen if you’re going to be seen at five different hospitals in 7 years.”

Encouraging the concept of “medical home” for SCD may be help ease transition from pediatric to adult care, thereby reducing fragmentation of care for young adults, according to Julie A. Panepinto, MD, professor of pediatric hematology and the director of the center for clinical effectiveness research at the Children’s Research Institute, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“That 18- to 30-year-old age group historically and repeatedly over time is shown to be the age that relies on the emergency department and that has a higher mortality as they transition,” Dr. Panepinto said in an interview. “So ideally, you would have a pediatric program that’s comprehensive and that can transition an adult patient to a very similar setting with knowledgeable providers in SCD across the spectrum, from the emergency department to the hospital to the outpatient clinic.”

Dr. Mahajan reported no disclosures related to her group’s study. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Pfizer and Janssen.

SOURCE: Shatola A et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 4667.

ORLANDO – While over time, results of a retrospective study suggest.

Nearly 60% of children between aged10-17 years were seen at just one facility over the course of 7 years in the analysis, which was based on analysis of data for nearly 7,000 patients seen in California during 1991-2016.

That contrasted sharply with young adults, aged 18-25 years, only about 20% of whom were admitted to one facility, said senior study author Anjlee Mahajan, MD, of the University of California, Davis, adding that another 20% were seen at five or more centers over a 7-year follow-up period.

Fragmentation of care didn’t increase the risk of death in this study, as investigators hypothesized it might. However, the outcomes and the quality of care among young adults with SCD who received inpatient care at multiple facilities nevertheless was likely to be affected, Dr. Mahajan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Imagine what that would be like to have a chronic, debilitating illness and to have to go to multiple different hospitals, during this vulnerable time period in your life, and being seen by different care providers who may not know you and may not have all of your records as well,” she said in a press conference at the meeting.

Providers and the health care system need to work harder to ensure young adults receive comprehensive and coordinated care, especially at a time when therapeutic advances are improving the treatment of this disease, according to the investigator.

“When you’re seen at one center, you can have a specific pain plan, and maybe when you are going into the emergency room and being admitted, your sickle cell care provider might come and visit you in the hospital or at least be in contact with your team,” Dr. Mahajan said in an interview. “That may not happen if you’re going to be seen at five different hospitals in 7 years.”

Encouraging the concept of “medical home” for SCD may be help ease transition from pediatric to adult care, thereby reducing fragmentation of care for young adults, according to Julie A. Panepinto, MD, professor of pediatric hematology and the director of the center for clinical effectiveness research at the Children’s Research Institute, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“That 18- to 30-year-old age group historically and repeatedly over time is shown to be the age that relies on the emergency department and that has a higher mortality as they transition,” Dr. Panepinto said in an interview. “So ideally, you would have a pediatric program that’s comprehensive and that can transition an adult patient to a very similar setting with knowledgeable providers in SCD across the spectrum, from the emergency department to the hospital to the outpatient clinic.”

Dr. Mahajan reported no disclosures related to her group’s study. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Pfizer and Janssen.

SOURCE: Shatola A et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 4667.

ORLANDO – While over time, results of a retrospective study suggest.

Nearly 60% of children between aged10-17 years were seen at just one facility over the course of 7 years in the analysis, which was based on analysis of data for nearly 7,000 patients seen in California during 1991-2016.

That contrasted sharply with young adults, aged 18-25 years, only about 20% of whom were admitted to one facility, said senior study author Anjlee Mahajan, MD, of the University of California, Davis, adding that another 20% were seen at five or more centers over a 7-year follow-up period.

Fragmentation of care didn’t increase the risk of death in this study, as investigators hypothesized it might. However, the outcomes and the quality of care among young adults with SCD who received inpatient care at multiple facilities nevertheless was likely to be affected, Dr. Mahajan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Imagine what that would be like to have a chronic, debilitating illness and to have to go to multiple different hospitals, during this vulnerable time period in your life, and being seen by different care providers who may not know you and may not have all of your records as well,” she said in a press conference at the meeting.

Providers and the health care system need to work harder to ensure young adults receive comprehensive and coordinated care, especially at a time when therapeutic advances are improving the treatment of this disease, according to the investigator.

“When you’re seen at one center, you can have a specific pain plan, and maybe when you are going into the emergency room and being admitted, your sickle cell care provider might come and visit you in the hospital or at least be in contact with your team,” Dr. Mahajan said in an interview. “That may not happen if you’re going to be seen at five different hospitals in 7 years.”

Encouraging the concept of “medical home” for SCD may be help ease transition from pediatric to adult care, thereby reducing fragmentation of care for young adults, according to Julie A. Panepinto, MD, professor of pediatric hematology and the director of the center for clinical effectiveness research at the Children’s Research Institute, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

“That 18- to 30-year-old age group historically and repeatedly over time is shown to be the age that relies on the emergency department and that has a higher mortality as they transition,” Dr. Panepinto said in an interview. “So ideally, you would have a pediatric program that’s comprehensive and that can transition an adult patient to a very similar setting with knowledgeable providers in SCD across the spectrum, from the emergency department to the hospital to the outpatient clinic.”

Dr. Mahajan reported no disclosures related to her group’s study. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Pfizer and Janssen.

SOURCE: Shatola A et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 4667.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2019

Social anxiety more likely with inattentive ADHD, psychiatric comorbidities

Social anxiety is more likely in adolescents aged 12-18 years with predominantly inattentive ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities, according to María Jesús Mardomingo-Sanz, MD, PhD, and associates.

A total of 234 ADHD patients with a mean age of 14.9 years were recruited for the cross-sectional, observational study, and social anxiety was assessed using the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A). Just under 70% were male; 37.2% had predominantly inattentive disease, 9% had predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease, and 51.7% had combined-type disease. , reported Dr. Mardomingo-Sanz, of the child psychiatry and psychology section at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, and associates. The study was published in Anales de Pediatría.

The investigators found that 50.4% of patients had a psychiatric comorbidity. Learning and communication disorders, and anxiety disorders were the most common, occurring in 20.1% and 19.2% of all patients, respectively. Patients within the cohort scored significantly higher on the SAS-A, compared with reference values in a healthy population.

Patients with predominantly inattentive disease had significantly higher scores in the SAS-A, compared with those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease (P = .015). Comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with the worst SAS-A scores (P less than .001).

“Social anxiety greatly influences the way in which children and adolescents interact with the surrounding environment and react to it, and therefore can contribute to the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Social anxiety detected by the SAS-A questionnaire is not diagnostic of an anxiety disorder, but detecting it is important, as it can contribute to the secondary prevention of future comorbidities that could lead to less favorable outcomes of these stage of development in patients with ADHD,” the investigators concluded.

Laboratorios Farmacéuticos funded the study, and the investigators reported receiving fees and being employed by Laboratorios Farmacéuticos.

SOURCE: Mardomingo-Sanz MJ et al. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90(6):349-61.

Social anxiety is more likely in adolescents aged 12-18 years with predominantly inattentive ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities, according to María Jesús Mardomingo-Sanz, MD, PhD, and associates.

A total of 234 ADHD patients with a mean age of 14.9 years were recruited for the cross-sectional, observational study, and social anxiety was assessed using the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A). Just under 70% were male; 37.2% had predominantly inattentive disease, 9% had predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease, and 51.7% had combined-type disease. , reported Dr. Mardomingo-Sanz, of the child psychiatry and psychology section at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, and associates. The study was published in Anales de Pediatría.

The investigators found that 50.4% of patients had a psychiatric comorbidity. Learning and communication disorders, and anxiety disorders were the most common, occurring in 20.1% and 19.2% of all patients, respectively. Patients within the cohort scored significantly higher on the SAS-A, compared with reference values in a healthy population.

Patients with predominantly inattentive disease had significantly higher scores in the SAS-A, compared with those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease (P = .015). Comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with the worst SAS-A scores (P less than .001).

“Social anxiety greatly influences the way in which children and adolescents interact with the surrounding environment and react to it, and therefore can contribute to the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Social anxiety detected by the SAS-A questionnaire is not diagnostic of an anxiety disorder, but detecting it is important, as it can contribute to the secondary prevention of future comorbidities that could lead to less favorable outcomes of these stage of development in patients with ADHD,” the investigators concluded.

Laboratorios Farmacéuticos funded the study, and the investigators reported receiving fees and being employed by Laboratorios Farmacéuticos.

SOURCE: Mardomingo-Sanz MJ et al. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90(6):349-61.

Social anxiety is more likely in adolescents aged 12-18 years with predominantly inattentive ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities, according to María Jesús Mardomingo-Sanz, MD, PhD, and associates.

A total of 234 ADHD patients with a mean age of 14.9 years were recruited for the cross-sectional, observational study, and social anxiety was assessed using the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A). Just under 70% were male; 37.2% had predominantly inattentive disease, 9% had predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease, and 51.7% had combined-type disease. , reported Dr. Mardomingo-Sanz, of the child psychiatry and psychology section at the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, and associates. The study was published in Anales de Pediatría.

The investigators found that 50.4% of patients had a psychiatric comorbidity. Learning and communication disorders, and anxiety disorders were the most common, occurring in 20.1% and 19.2% of all patients, respectively. Patients within the cohort scored significantly higher on the SAS-A, compared with reference values in a healthy population.

Patients with predominantly inattentive disease had significantly higher scores in the SAS-A, compared with those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive disease (P = .015). Comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with the worst SAS-A scores (P less than .001).

“Social anxiety greatly influences the way in which children and adolescents interact with the surrounding environment and react to it, and therefore can contribute to the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Social anxiety detected by the SAS-A questionnaire is not diagnostic of an anxiety disorder, but detecting it is important, as it can contribute to the secondary prevention of future comorbidities that could lead to less favorable outcomes of these stage of development in patients with ADHD,” the investigators concluded.

Laboratorios Farmacéuticos funded the study, and the investigators reported receiving fees and being employed by Laboratorios Farmacéuticos.

SOURCE: Mardomingo-Sanz MJ et al. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90(6):349-61.

FROM ANALES DE PEDIATRÍA

Influenza already in midseason form

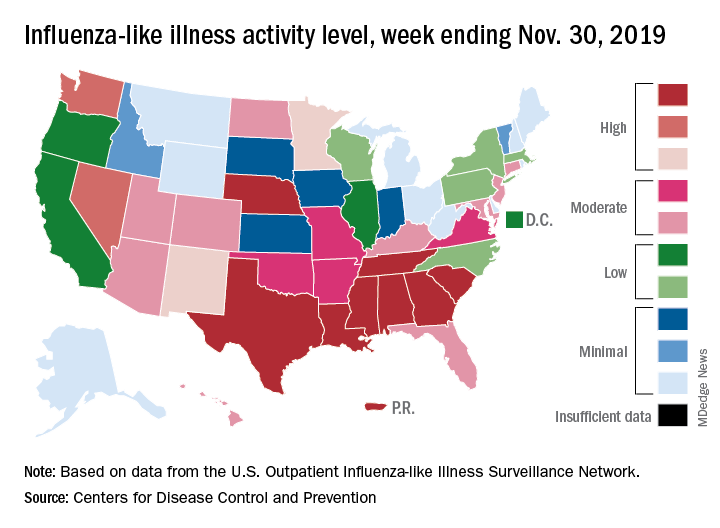

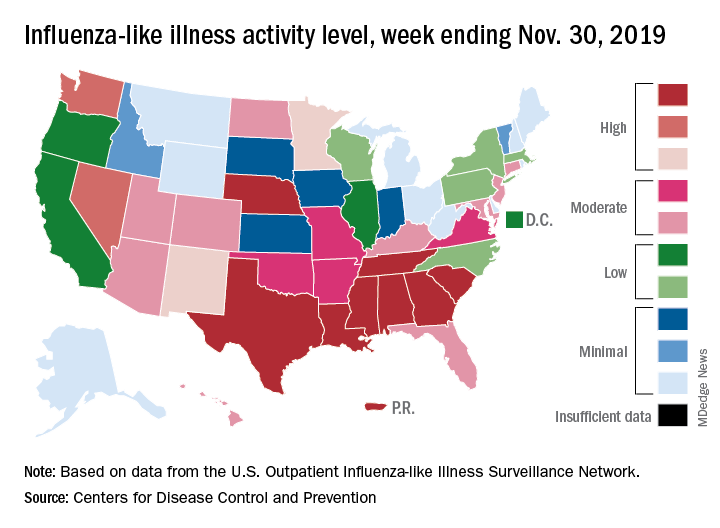

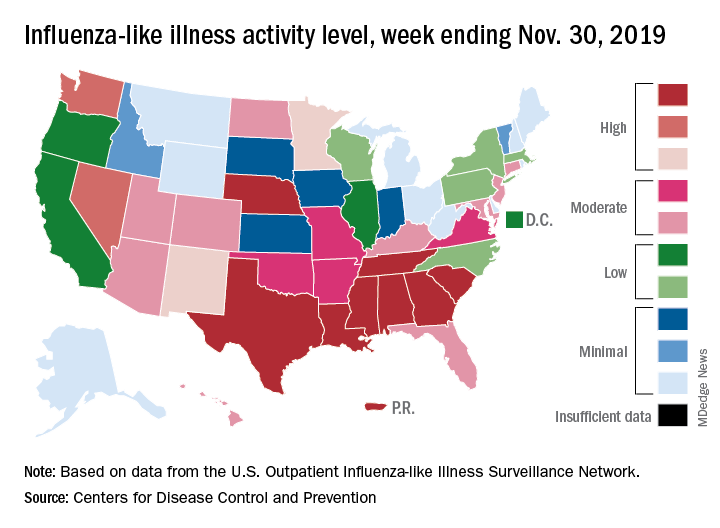

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

Reward, decision-making brain regions altered in teens with obesity

CHICAGO – according to a Brazilian study that used MRI to detect these changes.

Brain changes were significantly correlated with increased levels of insulin, leptin, and other appetite- and diet-related hormones and neurohormones, as well as with inflammatory markers.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Pamela Bertolazzi, a PhD student at the University of São Paulo, explained that childhood obesity in Brazil is estimated to have climbed by up to 40% in recent years, with almost one-third of Brazilian children and adolescents experiencing obesity. Epidemiologists estimate that there’s the potential for 2.6 million premature deaths from this level of overweight and obesity, she said. Brazil has over 211 million residents.

Previous studies have established diffusion tensor imaging as an MRI technique to assess white-matter integrity and architecture. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is a measure of brain tract integrity, and decreased FA can indicate demyelination or axonal degeneration.

Ms. Bertolazzi and colleagues compared 60 healthy weight adolescents with 57 adolescents with obesity to see how cerebral connectivity differed, and further correlated MRI findings with a serum assay of 57 analytes including inflammatory markers, neuropeptides, and hormones.

Adolescents aged 12-16 years were included if they met World Health Organization criteria for obesity or for healthy weight. The z score for the participants with obesity was 2.74, and 0.25 for the healthy-weight participants (P less than .001). Individuals who were underweight or overweight (but not obese) were excluded. Those with known significant psychiatric diagnoses or prior traumatic brain injury or neurosurgery also were excluded.

The mean age of participants was 14 years, and 29 of the 57 (51%) participants with obesity were female, as were 33 of 60 (55%) healthy weight participants. There was no significant difference in socioeconomic status between the two groups.

When participants’ brain MRI results were reviewed, Ms. Bertolazzi and associates saw several regions that had decreased FA only in the adolescents with obesity. In general terms, these brain areas are known to be concerned with appetite and reward.

Decreased FA – indicating demyelination or axonal degeneration – was seen particularly on the left-hand side of the corpus callosum, “the largest association pathway in the human brain,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. Looking at the interaction between decreased FA in this area and levels of various analytes, leptin, insulin, C-peptide, and total glucagonlike peptide–1 levels all were negatively associated with FA levels. A ratio of leptin to the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 also had a negative correlation with FA levels. All of these associations were statistically significant.

Decreased FA also was seen in the orbitofrontal gyrus, an area of the prefrontal cortex that links decision making with emotions and reward. Here, significant negative associations were seen with C-peptide, amylin, and the ratios of several other inflammatory markers to IL-10.

“Obesity was associated with a reduction of cerebral integrity in obese adolescents,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. The clinical significance of these findings is not yet known. However, she said that the disruption in regulation of reward and appetite circuitry her study found may set up adolescents with excess body mass for a maladaptive positive feedback loop: elevated insulin, leptin, and inflammatory cytokine levels may be contributing to disrupted appetite, which in turn contributes to ongoing increases in body mass index.

She and her colleagues are planning to enroll adolescents with obesity and their families in nutritional education and exercise programs, hoping to interrupt the cycle. They plan to obtain a baseline serum assay and MRI scan with diffusion tensor imaging and FA, and to repeat the studies about 3 months into an intensive intervention, to test the hypothesis that increased exercise and improved diet will result in reversal of the brain changes they found in this exploratory study. In particular, said Ms. Bertolazzi, they hope that encouraging physical activity will boost levels of HDL cholesterol, which may have a neuroprotective effect.

Ms. Bertolazzi reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – according to a Brazilian study that used MRI to detect these changes.

Brain changes were significantly correlated with increased levels of insulin, leptin, and other appetite- and diet-related hormones and neurohormones, as well as with inflammatory markers.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Pamela Bertolazzi, a PhD student at the University of São Paulo, explained that childhood obesity in Brazil is estimated to have climbed by up to 40% in recent years, with almost one-third of Brazilian children and adolescents experiencing obesity. Epidemiologists estimate that there’s the potential for 2.6 million premature deaths from this level of overweight and obesity, she said. Brazil has over 211 million residents.

Previous studies have established diffusion tensor imaging as an MRI technique to assess white-matter integrity and architecture. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is a measure of brain tract integrity, and decreased FA can indicate demyelination or axonal degeneration.

Ms. Bertolazzi and colleagues compared 60 healthy weight adolescents with 57 adolescents with obesity to see how cerebral connectivity differed, and further correlated MRI findings with a serum assay of 57 analytes including inflammatory markers, neuropeptides, and hormones.

Adolescents aged 12-16 years were included if they met World Health Organization criteria for obesity or for healthy weight. The z score for the participants with obesity was 2.74, and 0.25 for the healthy-weight participants (P less than .001). Individuals who were underweight or overweight (but not obese) were excluded. Those with known significant psychiatric diagnoses or prior traumatic brain injury or neurosurgery also were excluded.

The mean age of participants was 14 years, and 29 of the 57 (51%) participants with obesity were female, as were 33 of 60 (55%) healthy weight participants. There was no significant difference in socioeconomic status between the two groups.

When participants’ brain MRI results were reviewed, Ms. Bertolazzi and associates saw several regions that had decreased FA only in the adolescents with obesity. In general terms, these brain areas are known to be concerned with appetite and reward.

Decreased FA – indicating demyelination or axonal degeneration – was seen particularly on the left-hand side of the corpus callosum, “the largest association pathway in the human brain,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. Looking at the interaction between decreased FA in this area and levels of various analytes, leptin, insulin, C-peptide, and total glucagonlike peptide–1 levels all were negatively associated with FA levels. A ratio of leptin to the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 also had a negative correlation with FA levels. All of these associations were statistically significant.

Decreased FA also was seen in the orbitofrontal gyrus, an area of the prefrontal cortex that links decision making with emotions and reward. Here, significant negative associations were seen with C-peptide, amylin, and the ratios of several other inflammatory markers to IL-10.

“Obesity was associated with a reduction of cerebral integrity in obese adolescents,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. The clinical significance of these findings is not yet known. However, she said that the disruption in regulation of reward and appetite circuitry her study found may set up adolescents with excess body mass for a maladaptive positive feedback loop: elevated insulin, leptin, and inflammatory cytokine levels may be contributing to disrupted appetite, which in turn contributes to ongoing increases in body mass index.

She and her colleagues are planning to enroll adolescents with obesity and their families in nutritional education and exercise programs, hoping to interrupt the cycle. They plan to obtain a baseline serum assay and MRI scan with diffusion tensor imaging and FA, and to repeat the studies about 3 months into an intensive intervention, to test the hypothesis that increased exercise and improved diet will result in reversal of the brain changes they found in this exploratory study. In particular, said Ms. Bertolazzi, they hope that encouraging physical activity will boost levels of HDL cholesterol, which may have a neuroprotective effect.

Ms. Bertolazzi reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – according to a Brazilian study that used MRI to detect these changes.

Brain changes were significantly correlated with increased levels of insulin, leptin, and other appetite- and diet-related hormones and neurohormones, as well as with inflammatory markers.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Pamela Bertolazzi, a PhD student at the University of São Paulo, explained that childhood obesity in Brazil is estimated to have climbed by up to 40% in recent years, with almost one-third of Brazilian children and adolescents experiencing obesity. Epidemiologists estimate that there’s the potential for 2.6 million premature deaths from this level of overweight and obesity, she said. Brazil has over 211 million residents.

Previous studies have established diffusion tensor imaging as an MRI technique to assess white-matter integrity and architecture. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is a measure of brain tract integrity, and decreased FA can indicate demyelination or axonal degeneration.

Ms. Bertolazzi and colleagues compared 60 healthy weight adolescents with 57 adolescents with obesity to see how cerebral connectivity differed, and further correlated MRI findings with a serum assay of 57 analytes including inflammatory markers, neuropeptides, and hormones.

Adolescents aged 12-16 years were included if they met World Health Organization criteria for obesity or for healthy weight. The z score for the participants with obesity was 2.74, and 0.25 for the healthy-weight participants (P less than .001). Individuals who were underweight or overweight (but not obese) were excluded. Those with known significant psychiatric diagnoses or prior traumatic brain injury or neurosurgery also were excluded.

The mean age of participants was 14 years, and 29 of the 57 (51%) participants with obesity were female, as were 33 of 60 (55%) healthy weight participants. There was no significant difference in socioeconomic status between the two groups.

When participants’ brain MRI results were reviewed, Ms. Bertolazzi and associates saw several regions that had decreased FA only in the adolescents with obesity. In general terms, these brain areas are known to be concerned with appetite and reward.

Decreased FA – indicating demyelination or axonal degeneration – was seen particularly on the left-hand side of the corpus callosum, “the largest association pathway in the human brain,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. Looking at the interaction between decreased FA in this area and levels of various analytes, leptin, insulin, C-peptide, and total glucagonlike peptide–1 levels all were negatively associated with FA levels. A ratio of leptin to the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 also had a negative correlation with FA levels. All of these associations were statistically significant.

Decreased FA also was seen in the orbitofrontal gyrus, an area of the prefrontal cortex that links decision making with emotions and reward. Here, significant negative associations were seen with C-peptide, amylin, and the ratios of several other inflammatory markers to IL-10.

“Obesity was associated with a reduction of cerebral integrity in obese adolescents,” said Ms. Bertolazzi. The clinical significance of these findings is not yet known. However, she said that the disruption in regulation of reward and appetite circuitry her study found may set up adolescents with excess body mass for a maladaptive positive feedback loop: elevated insulin, leptin, and inflammatory cytokine levels may be contributing to disrupted appetite, which in turn contributes to ongoing increases in body mass index.

She and her colleagues are planning to enroll adolescents with obesity and their families in nutritional education and exercise programs, hoping to interrupt the cycle. They plan to obtain a baseline serum assay and MRI scan with diffusion tensor imaging and FA, and to repeat the studies about 3 months into an intensive intervention, to test the hypothesis that increased exercise and improved diet will result in reversal of the brain changes they found in this exploratory study. In particular, said Ms. Bertolazzi, they hope that encouraging physical activity will boost levels of HDL cholesterol, which may have a neuroprotective effect.

Ms. Bertolazzi reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM RSNA 2019

FDA expands use of Toujeo to childhood type 1 diabetes

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for Toujeo (insulin glargine 300 units/mL injection; Sanofi) to include children as young as 6 years of age with type 1 diabetes.

The FDA first approved Toujeo in 2015 for adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, designed as a more potent follow-up to Sanofi’s top-selling insulin glargine (Lantus).

Last month, Sanofi reported positive results from the phase 3 EDITION JUNIOR trial of Toujeo in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. These were presented at the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes 45th Annual Conference in Boston.

In the trial, 463 children and adolescents (aged 6-17 years) treated for type 1 diabetes for at least 1 year and with A1c between 7.5% and 11.0% at screening were randomized to Toujeo or insulin glargine 100 units/mL (Gla-100); participants continued to take their existing mealtime insulin.

The primary endpoint was noninferior reduction in A1c after 26 weeks.

The study met its primary endpoint, confirming a noninferior reduction in A1c with Toujeo versus Gla-100 after 26 weeks (mean reduction, 0.4% vs. 0.4%; difference, 0.004%; 95% confidence interval, –0.17 to 0.18; upper bound was below the prespecified noninferiority margin of 0.3%).

Over 26 weeks, a comparable number of patients in each group experienced one or more hypoglycemic events documented at anytime over 24 hours. Numerically fewer patients taking Toujeo experienced severe hypoglycemia or experienced one or more episodes of hyperglycemia with ketosis compared with those taking Gla-100.

No unexpected safety concerns were reported based on the established profiles of both products, the company said.

In October 2019, the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Toujeo for children age 6 years and older with diabetes.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for Toujeo (insulin glargine 300 units/mL injection; Sanofi) to include children as young as 6 years of age with type 1 diabetes.

The FDA first approved Toujeo in 2015 for adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, designed as a more potent follow-up to Sanofi’s top-selling insulin glargine (Lantus).

Last month, Sanofi reported positive results from the phase 3 EDITION JUNIOR trial of Toujeo in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. These were presented at the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes 45th Annual Conference in Boston.

In the trial, 463 children and adolescents (aged 6-17 years) treated for type 1 diabetes for at least 1 year and with A1c between 7.5% and 11.0% at screening were randomized to Toujeo or insulin glargine 100 units/mL (Gla-100); participants continued to take their existing mealtime insulin.

The primary endpoint was noninferior reduction in A1c after 26 weeks.

The study met its primary endpoint, confirming a noninferior reduction in A1c with Toujeo versus Gla-100 after 26 weeks (mean reduction, 0.4% vs. 0.4%; difference, 0.004%; 95% confidence interval, –0.17 to 0.18; upper bound was below the prespecified noninferiority margin of 0.3%).

Over 26 weeks, a comparable number of patients in each group experienced one or more hypoglycemic events documented at anytime over 24 hours. Numerically fewer patients taking Toujeo experienced severe hypoglycemia or experienced one or more episodes of hyperglycemia with ketosis compared with those taking Gla-100.

No unexpected safety concerns were reported based on the established profiles of both products, the company said.

In October 2019, the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Toujeo for children age 6 years and older with diabetes.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for Toujeo (insulin glargine 300 units/mL injection; Sanofi) to include children as young as 6 years of age with type 1 diabetes.

The FDA first approved Toujeo in 2015 for adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, designed as a more potent follow-up to Sanofi’s top-selling insulin glargine (Lantus).

Last month, Sanofi reported positive results from the phase 3 EDITION JUNIOR trial of Toujeo in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. These were presented at the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes 45th Annual Conference in Boston.

In the trial, 463 children and adolescents (aged 6-17 years) treated for type 1 diabetes for at least 1 year and with A1c between 7.5% and 11.0% at screening were randomized to Toujeo or insulin glargine 100 units/mL (Gla-100); participants continued to take their existing mealtime insulin.

The primary endpoint was noninferior reduction in A1c after 26 weeks.

The study met its primary endpoint, confirming a noninferior reduction in A1c with Toujeo versus Gla-100 after 26 weeks (mean reduction, 0.4% vs. 0.4%; difference, 0.004%; 95% confidence interval, –0.17 to 0.18; upper bound was below the prespecified noninferiority margin of 0.3%).

Over 26 weeks, a comparable number of patients in each group experienced one or more hypoglycemic events documented at anytime over 24 hours. Numerically fewer patients taking Toujeo experienced severe hypoglycemia or experienced one or more episodes of hyperglycemia with ketosis compared with those taking Gla-100.

No unexpected safety concerns were reported based on the established profiles of both products, the company said.

In October 2019, the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Toujeo for children age 6 years and older with diabetes.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

Decreasing Overutilization of Echocardiograms and Abdominal Imaging in the Evaluation of Children with Fungemia

From the University of Miami, Department of Pediatrics and Department of Medicine, Miami, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: Pediatric fungemia is associated with a low risk of fungal endocarditis and renal infections. The majority of current guidelines do not recommend routine abdominal imaging/echocardiograms in the evaluation of fungemia, but such imaging has been routinely ordered for patients on the pediatric gastroenterology service at our institution. Our goals were to assess the financial impact of this deviation from current clinical guidelines and redefine the standard work to reduce overutilization of abdominal ultrasounds and echocardiograms. Specifically, our goal was to reduce imaging by 50% by 18 months.

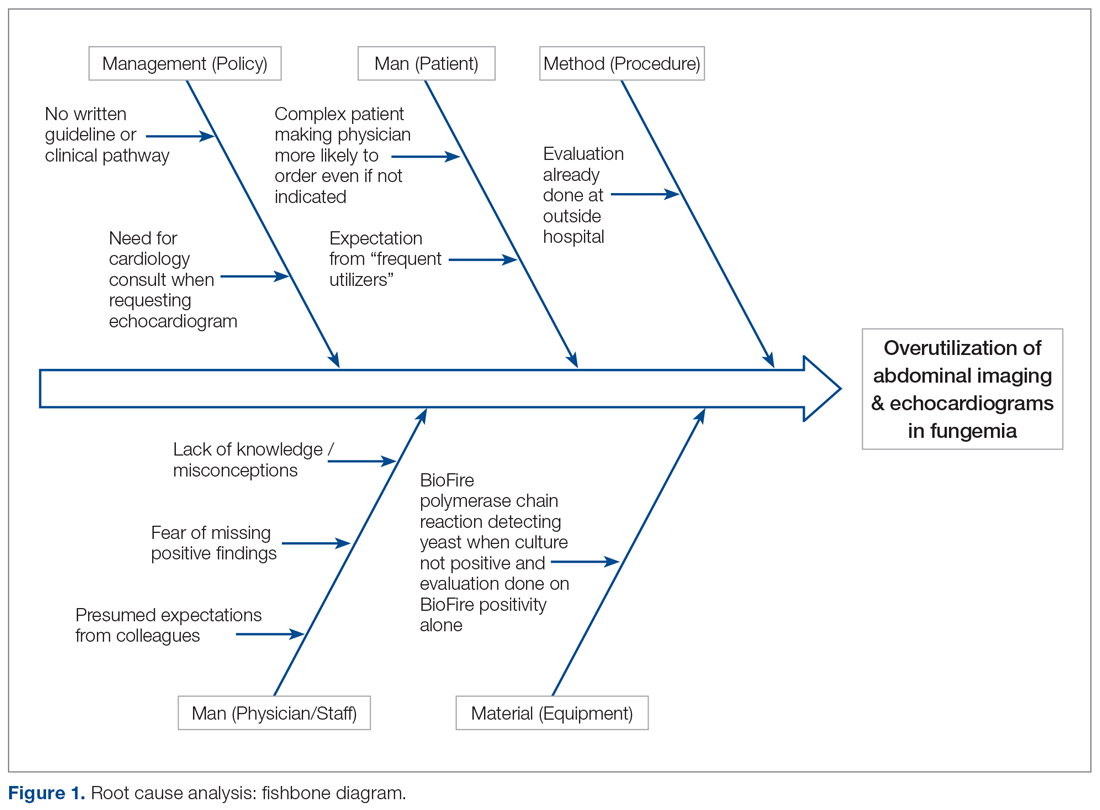

- Methods: Root cause analysis showed a lack of familiarity with current evidence. Using this data, countermeasures were implemented, including practitioner education of guidelines and creation of a readily accessible clinical pathway and an electronic order set for pediatric fungemia management. Balancing measures were missed episodes of fungal endocarditis and renal infection.

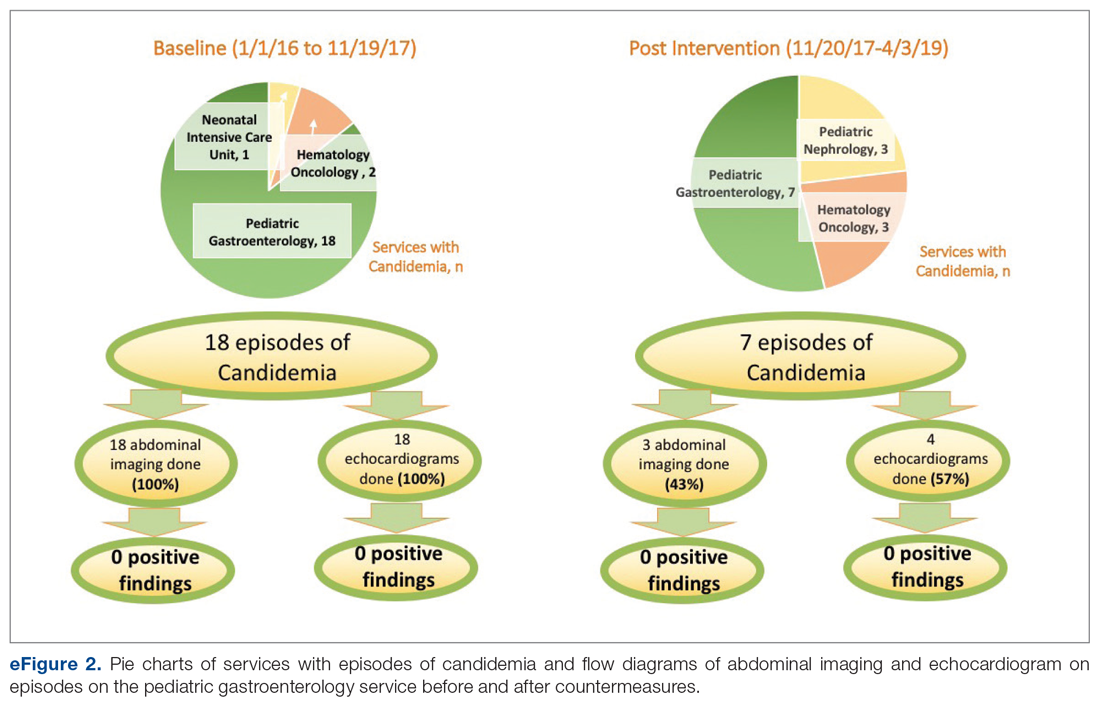

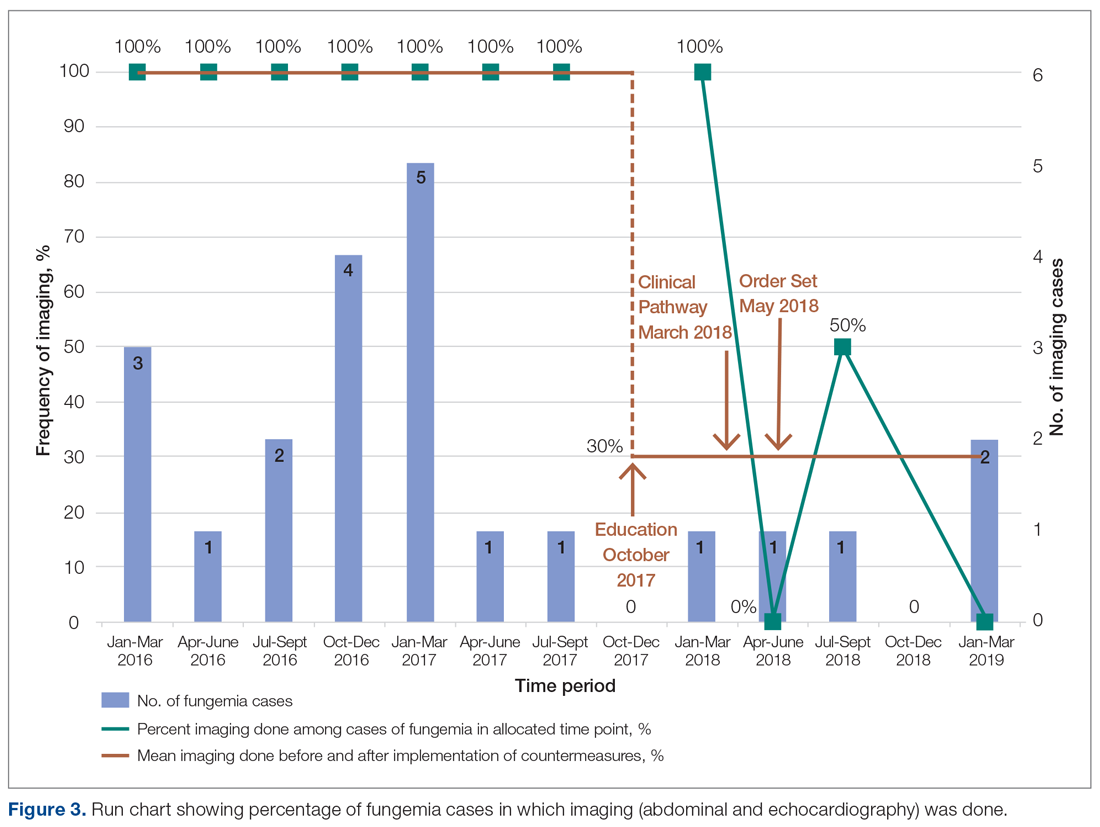

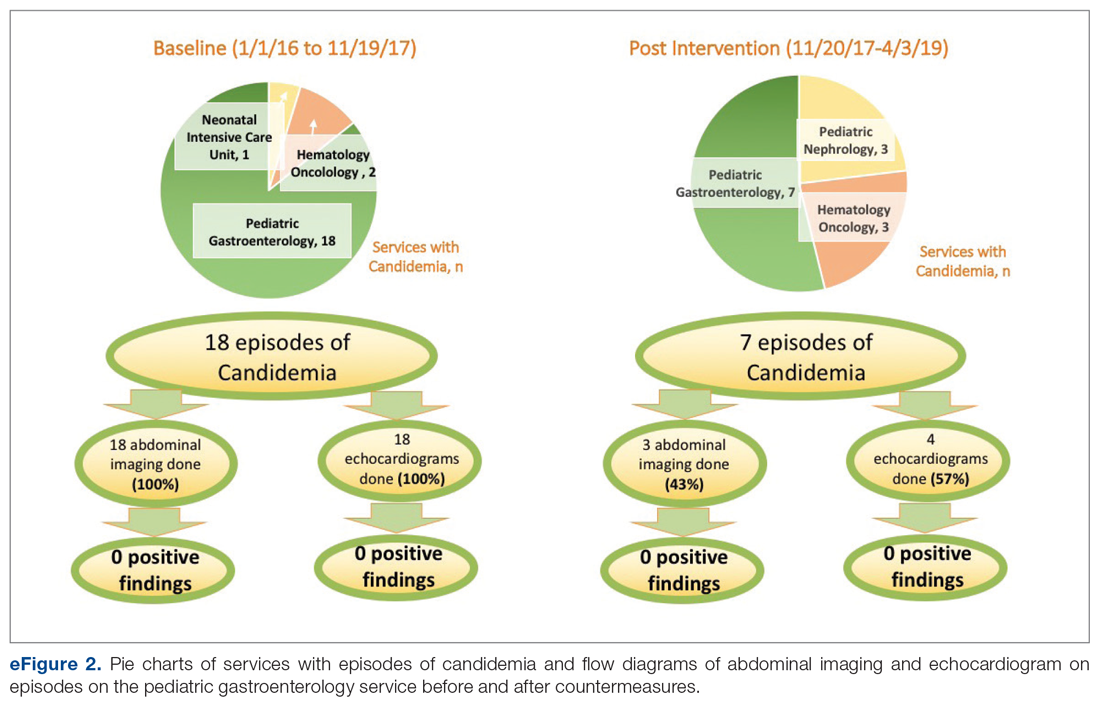

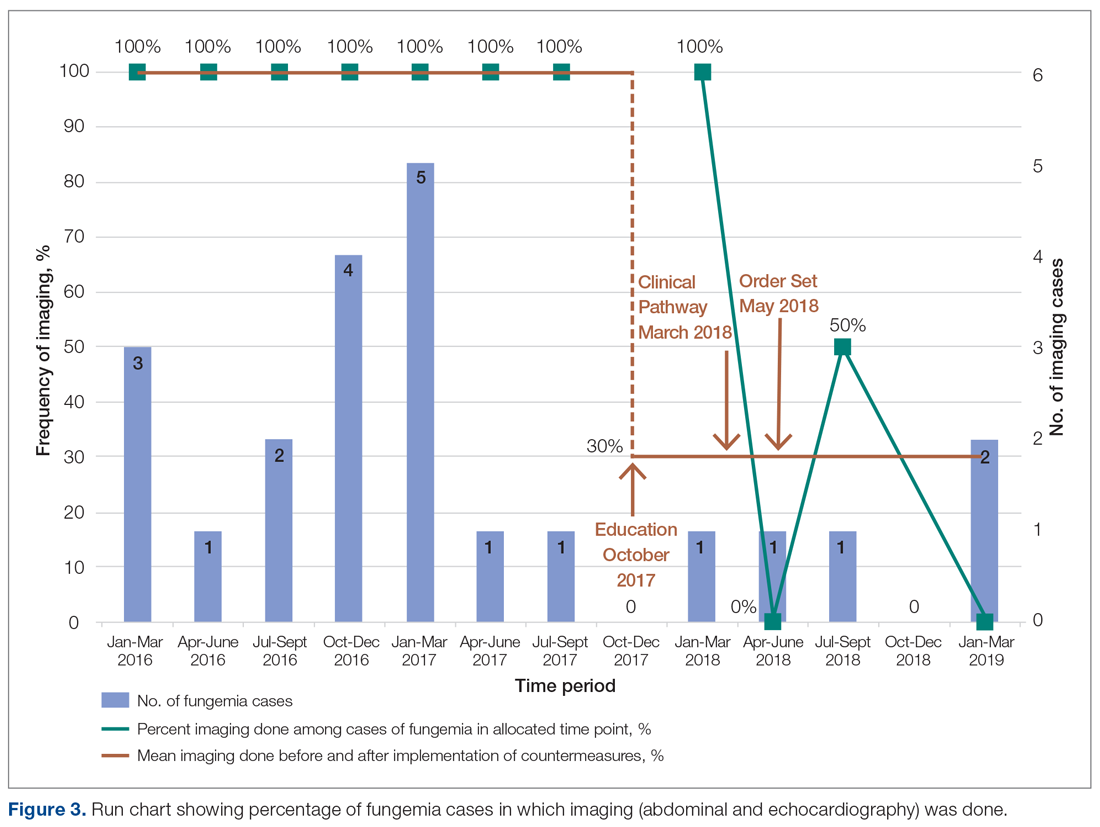

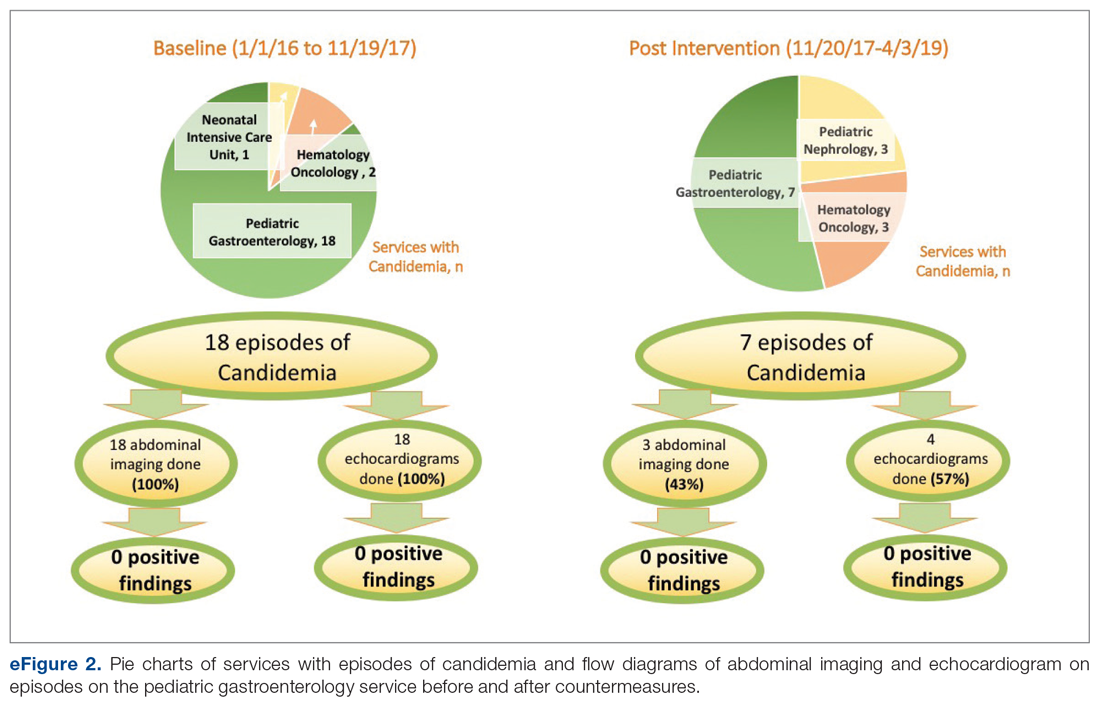

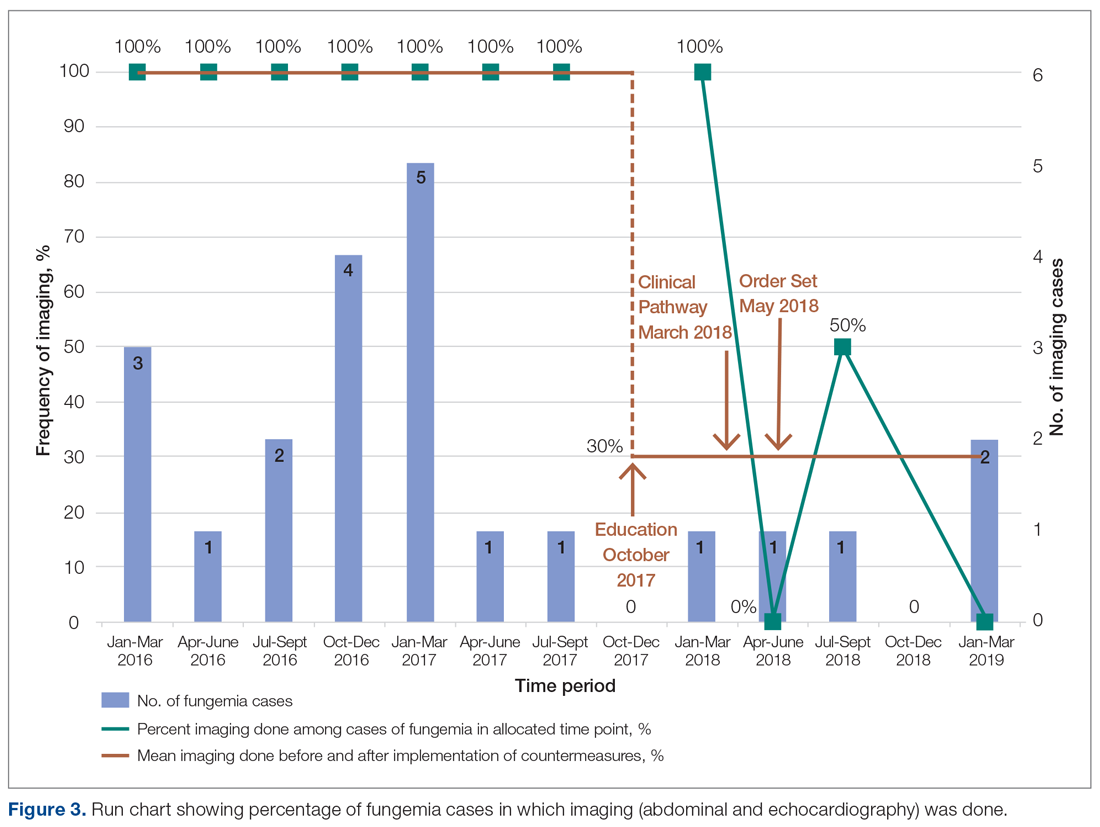

- Results: During the period January 1, 2016 to November 19, 2017, 18 of 21 episodes of fungemia in our pediatric institution occurred in patients admitted to the pediatric gastroenterology service. Abdominal imaging and echocardiograms were done 100% of the time, with no positive findings and an estimated cost of approximately $58,000. Post-intervention from November 20, 2017 to April 3, 2019, 7 of 13 episodes of fungemia occurred on this service. Frequency of abdominal imaging and echocardiograms decreased to 43% and 57%, respectively. No episodes of fungal endocarditis or renal infection were identified.

- Conclusion: Overutilization of abdominal imaging and echocardiograms in pediatric fungemia evaluation can be safely decreased.

Keywords: guidelines; cost; candidemia; endocarditis.

Practitioners may remain under the impression that routine abdominal ultrasounds (US) and echocardiograms (echo) are indicated in fungemia to evaluate for fungal endocarditis and renal infection, although these conditions are rare and limited to a subset of the population.1-10 Risk factors include prematurity, immunosuppression, prior bacterial endocarditis, abnormal cardiac valves, and previous urogenital surgeries.11

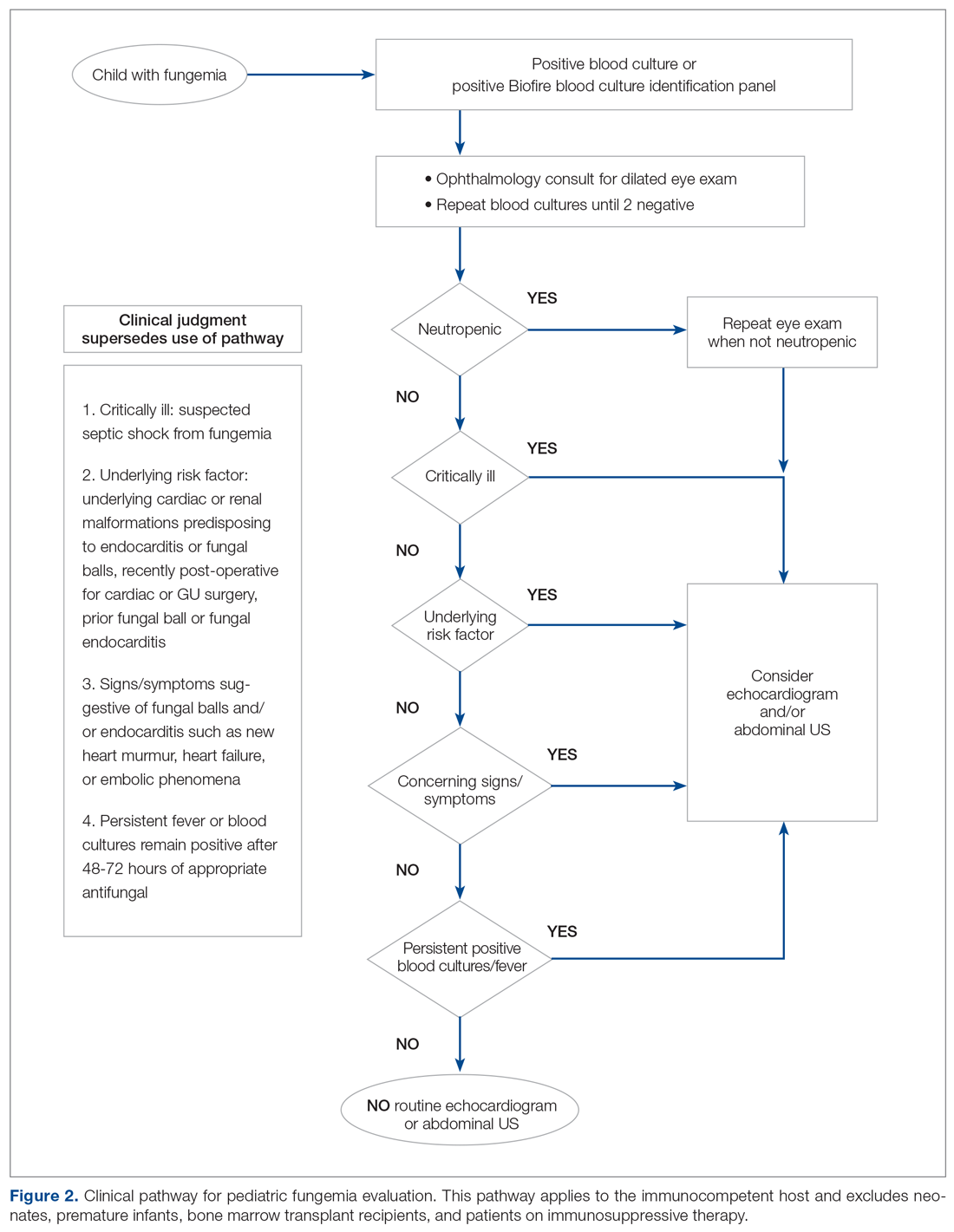

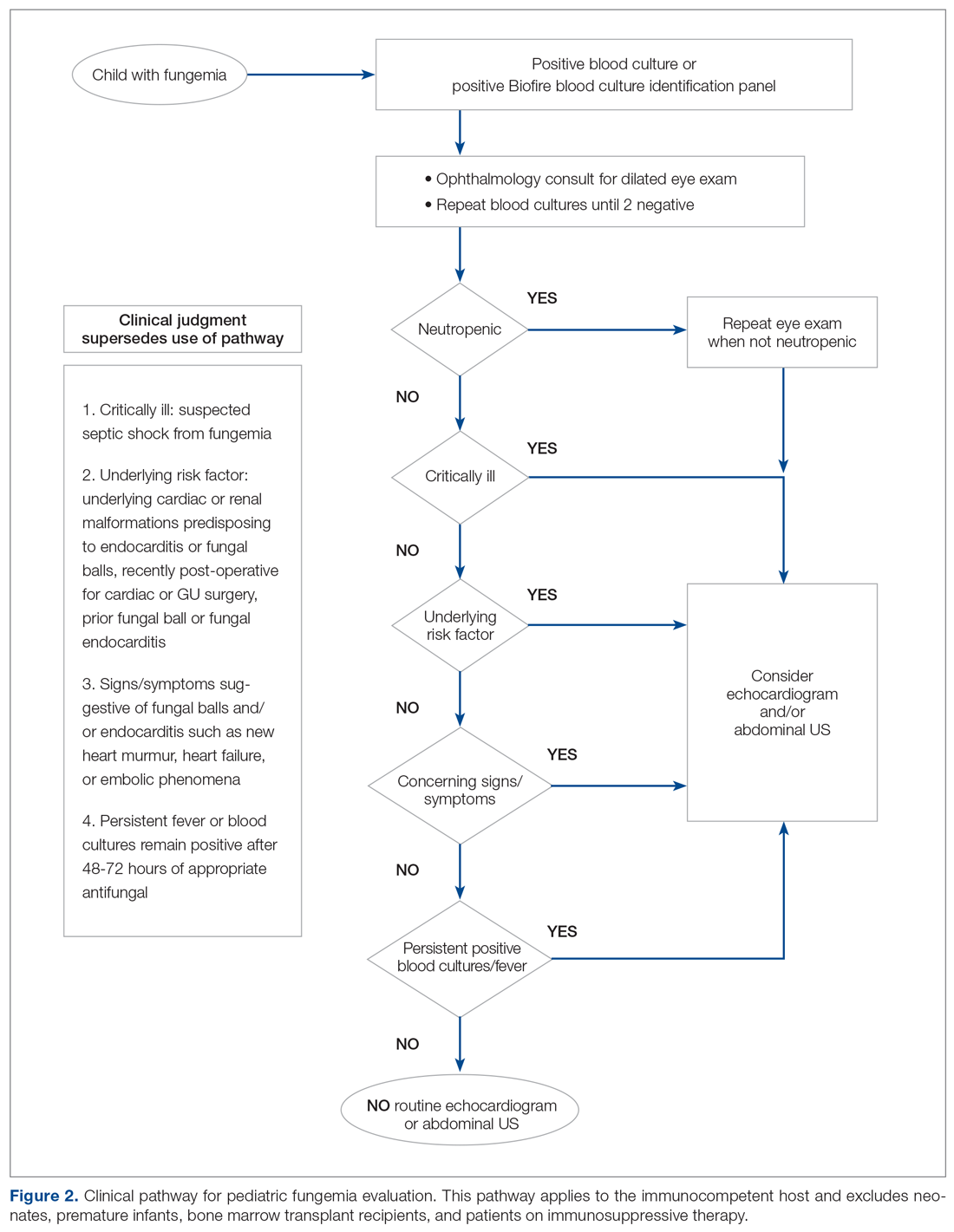

The 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines do not recommend routine US or echo but rather provide scenarios in which Candida endocarditis should be suspected, and these include: persistently positive blood cultures, persistent fevers despite appropriate therapy, and clinical signs that may suggest endocarditis, such as a new heart murmur, heart failure, or embolic phenomena.11 IDSA recommends abdominal imaging in neonates with persistently positive blood cultures to evaluate the urogenital system, in addition to the liver and spleen. They also recommend abdominal imaging in symptomatic ascending Candida pyelonephritis beyond the neonatal period and in chronic disseminated candidiasis; the latter is uncommon and seen almost exclusively in patients recovering from neutropenia with a hematologic malignancy.11

We also reviewed guidelines on fungemia originating outside the United States. The 2010 Canadian clinical guidelines on invasive candidiasis do not explicitly recommend routine imaging, but rather state that various imaging studies, including US and echo among others, may be helpful.12 The German Speaking Mycological Society and the Paul-Ehrlich-Society for Chemotherapy published a joint recommendation against routine US and echo in uncomplicated candidemia in 2011.13

The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases is the only society that recommends routine echo. Their 2012 guidelines on candidiasis recommend transesophageal echo in adults14 and echocardiography in children,15 as well as abdominal imaging in the diagnosis of chronic disseminated candidiasis in adults with hematological malignancies/hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.16

The 2013 Brazilian guidelines explicitly recommend against routine abdominal imaging and echo because of the low frequency of visceral lesions in adults with candidemia and recommend reserving imaging for those with persistently positive blood cultures or with clinical signs/symptoms suggestive of endocarditis/abdominal infection or clinical deterioration.17 The 2014 Japanese guidelines recommend ruling out chronic disseminated candidiasis in these patients with symptoms during the neutrophil recovery phase, but do not mention routinely imaging other patients. They do not address the role of echocardiography.18

Although physicians in the United Sates typically follow IDSA guidelines, abdominal US and echo were ordered routinely for patients with fungemia on the pediatric gastroenterology service at our institution, leading to higher medical costs and waste of medical resources. Our goals were to assess the current standard work for fungemia evaluation on this service, assess the impact of its deviation from current clinical guidelines, and redefine the standard work by (1) presenting current evidence to practitioners taking care of patients on this service, (2) providing a clinical pathway that allowed for variations where appropriate, and (3) providing a plan for pediatric fungemia management. Our SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely) goal was to reduce overutilization of abdominal US and echo in pediatric patients with fungemia on the pediatric gastroenterology service by 50%.

Methods

Study, Setting, and Participants

We executed this quality improvement project at a quaternary care pediatric hospital affiliated with a school of medicine. The project scope consisted of inpatient pediatric patients with fungemia on the pediatric gastroenterology service admitted to the wards or pediatric critical care unit at this institution, along with the practitioners caring for these patients. The project was part of an institutional quality improvement initiative program. The quality improvement team included quality improvement experts from the departments of medicine and pediatrics, a pediatric resident and student, and physicians from the divisions of pediatric infectious disease, pediatric critical care, and pediatric gastroenterology. This study qualified for Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption based on the University’s IRB stipulations.

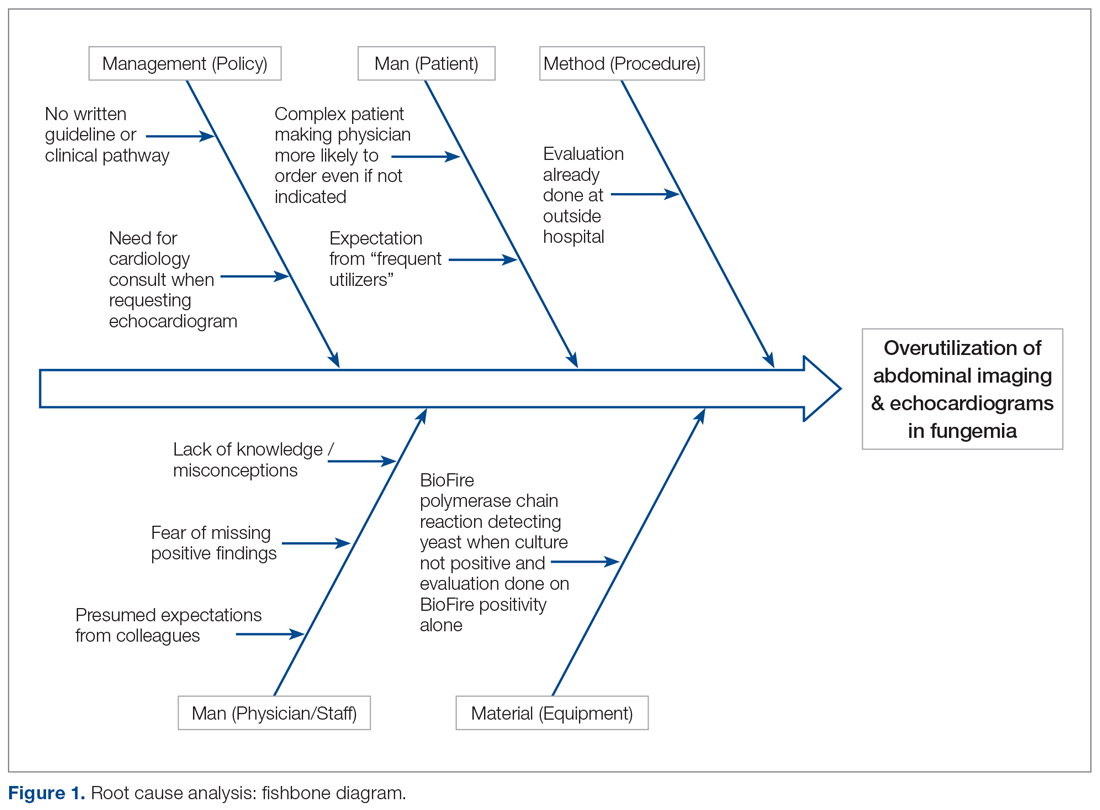

Current Condition

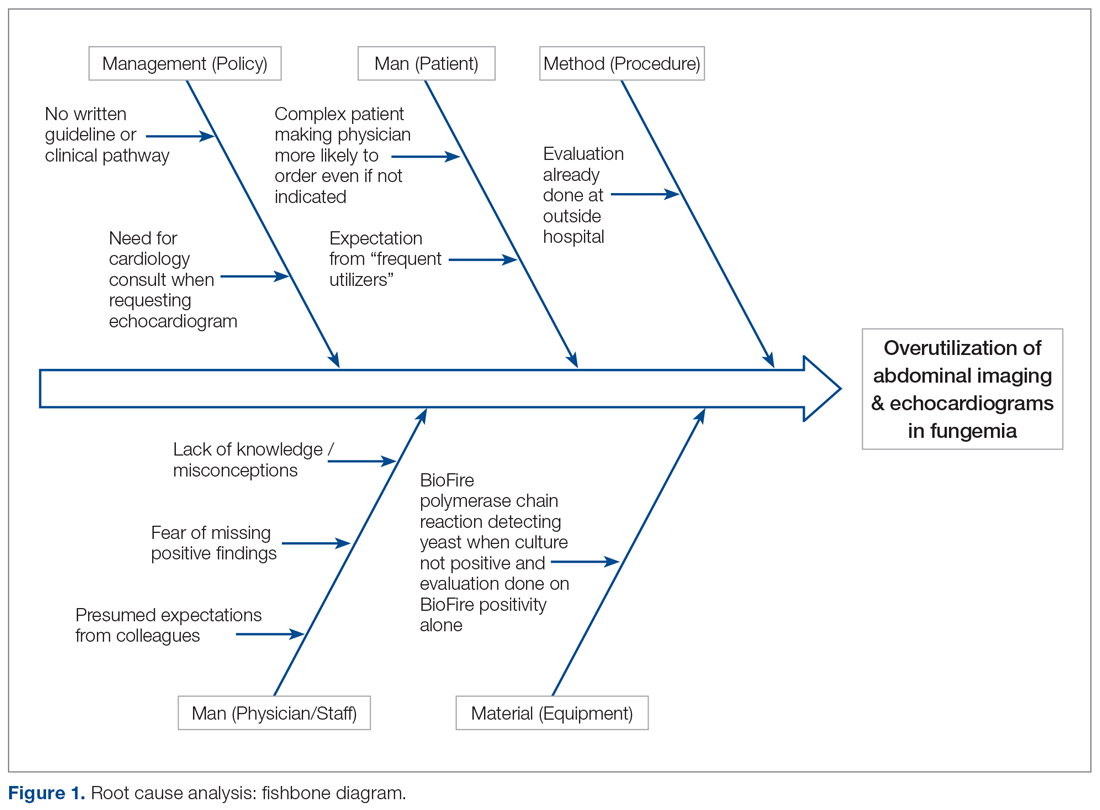

Root cause analysis was performed by creating a process map of the current standard work and a fishbone diagram (Figure 1). We incorporated feedback from voice of the customer in the root cause analysis. In this analysis, the voice of the customer came from the bedside floor nurses, ultrasound clerk and sonographer, echo technician, cardiology fellow, and microbiology medical technician. We got their feedback on our process map, its accuracy and ways to expand, their thoughts on the problem and why we have this problem, and any solutions they could offer to help improve the problem. Some of the key points obtained were: echos were not routinely done on the floors and were not considered urgent as they often did not change management; the sonographer and those from the cardiology department felt imaging was often overutilized because of misconceptions and lack of available hospital guidelines. Suggested solutions included provider education with reference to Duke’s criteria and establishing a clinical pathway approved by all concerned departments.

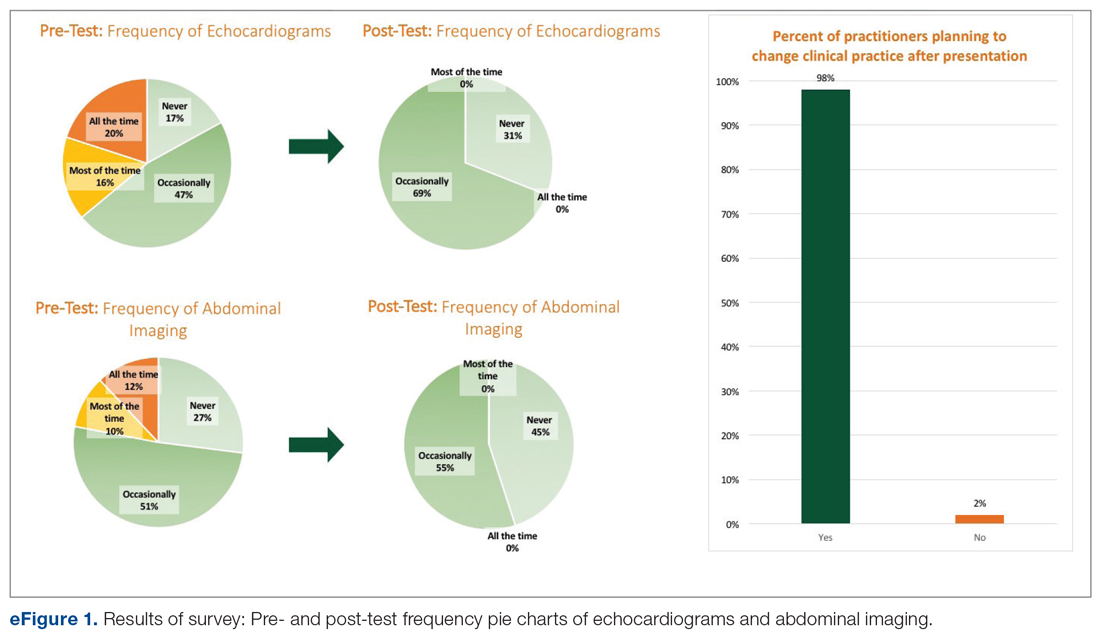

Prior to education, we surveyed current practices of practitioners on teams caring for these patients, which included physicians of all levels (attendings, fellows, residents) as well as nurse practitioners and medical students from the department of pediatrics and divisions of pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric infectious disease, and pediatric critical care medicine.

Countermeasures

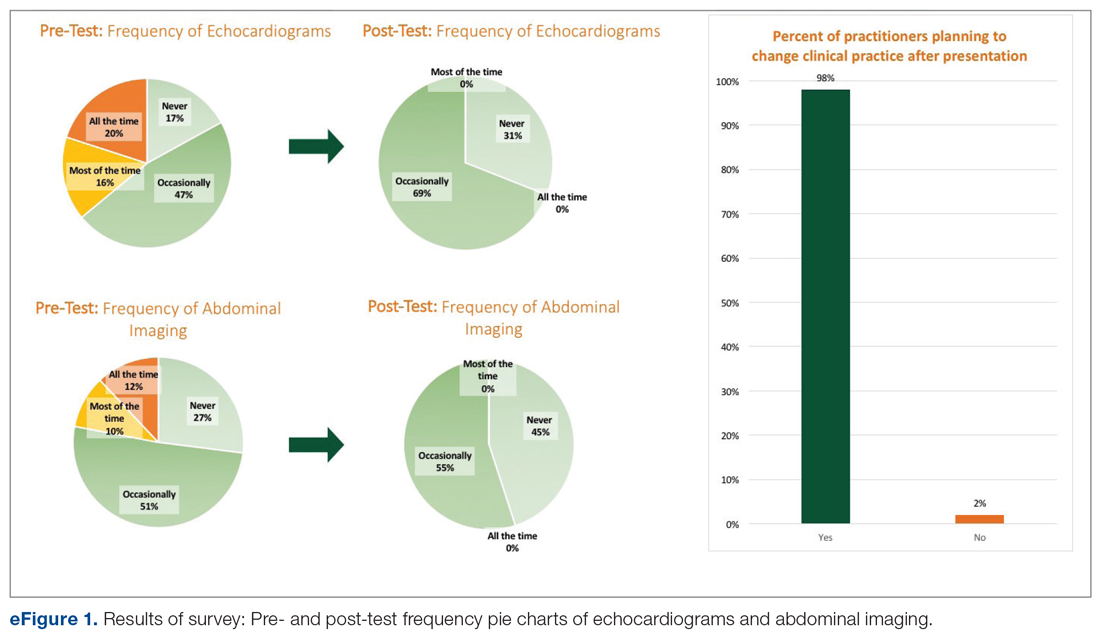

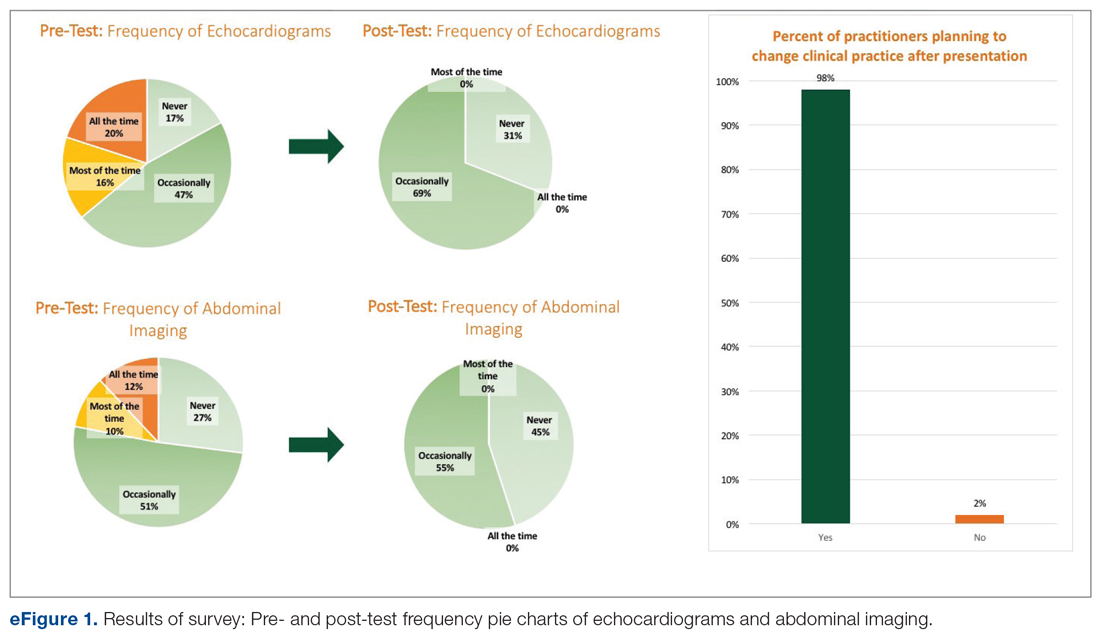

Practitioner Education. In October 2017 practitioners were given a 20-minute presentation on the latest international guidelines on fungemia. Fifty-nine practitioners completed pre- and post-test surveys. Eight respondents were excluded due to incomplete surveys. We compared self-reported frequencies of ordering abdominal imaging and echo before the presentation with intention to order post education. Intention to change clinical practice after the presentation was also surveyed.

Clinical Pathway. Education alone may not result in sustainability, and thus we provided a readily accessible clinical pathway and an electronic order set for pediatric fungemia management. Inter-department buy-in was also necessary for success. It was important to get the input from the various teams (infectious disease, cardiology, gastroenterology, and critical care), which was done by incorporating members from those divisions in the project or getting their feedback through voice of the customer analysis.

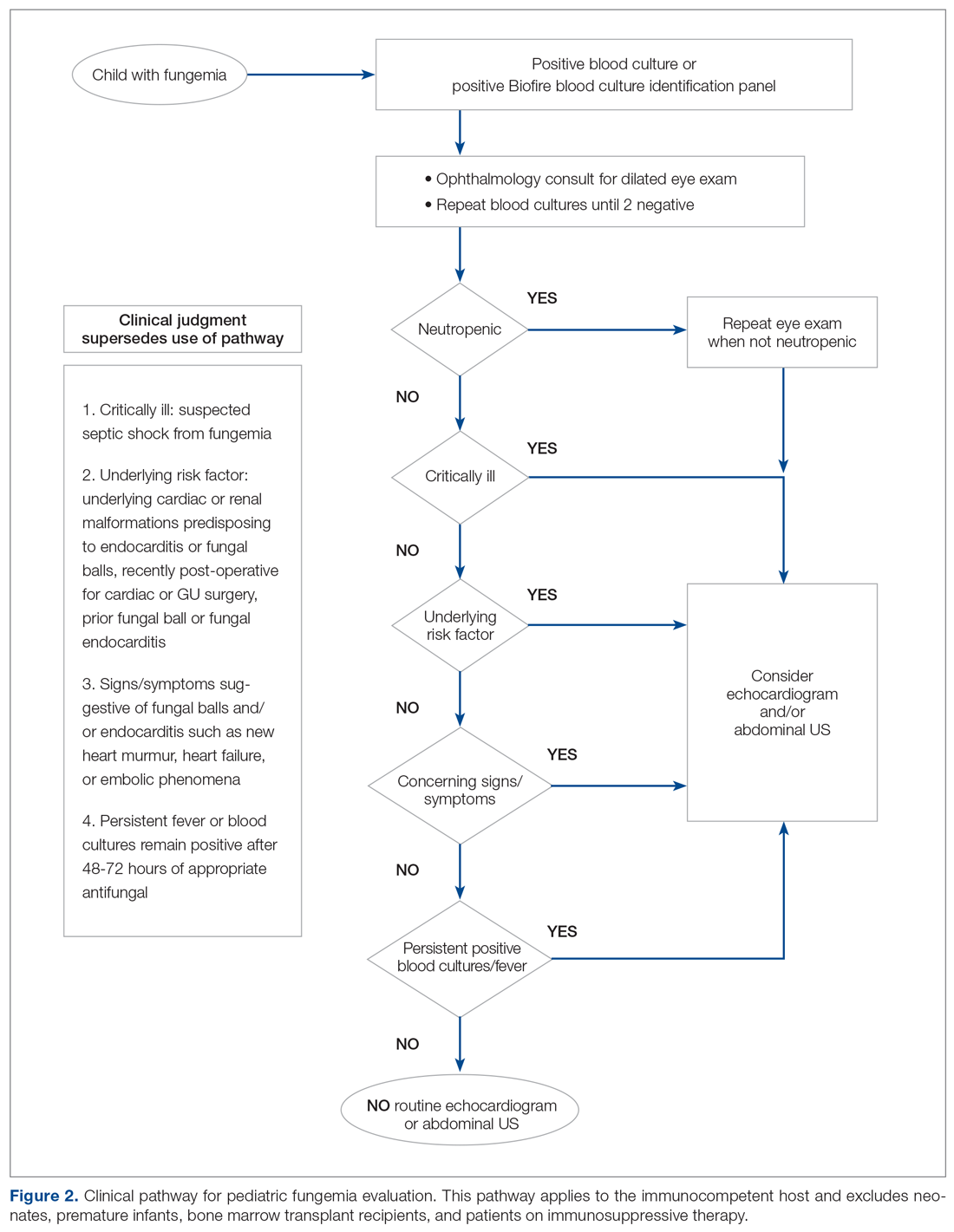

We redefined standard work based on current evidence and created a clinical pathway during March 2018 that included variations when appropriate (Figure 2). We presented the clinical pathway to practitioners and distributed it via email. We also made it available to pediatric residents and fellows on their mobile institutional work resource application.

Electronic Order Set. We created an electronic order set for pediatric fungemia management and made it available in the electronic health record May 2018.

Measurement