User login

Children and COVID: A look back as the fourth year begins

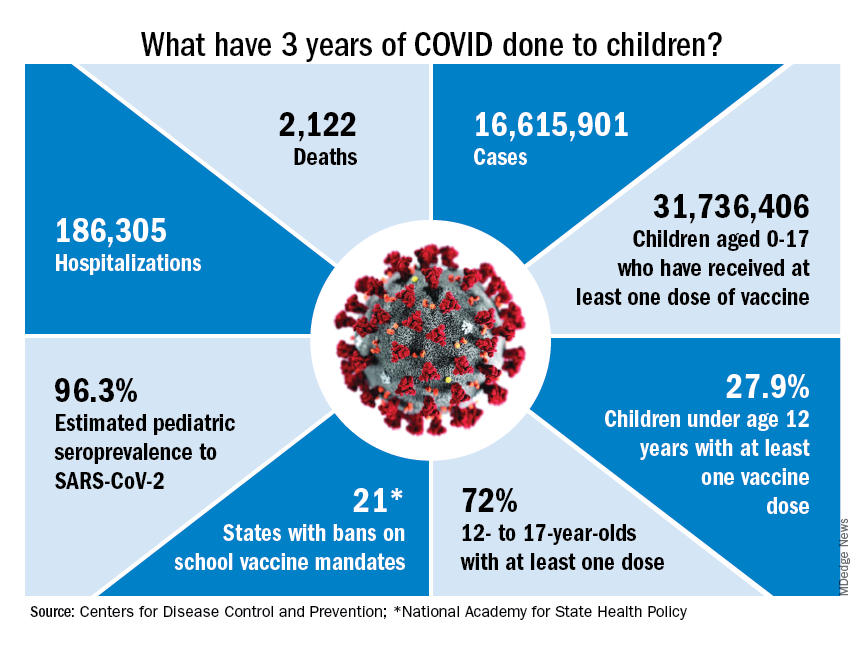

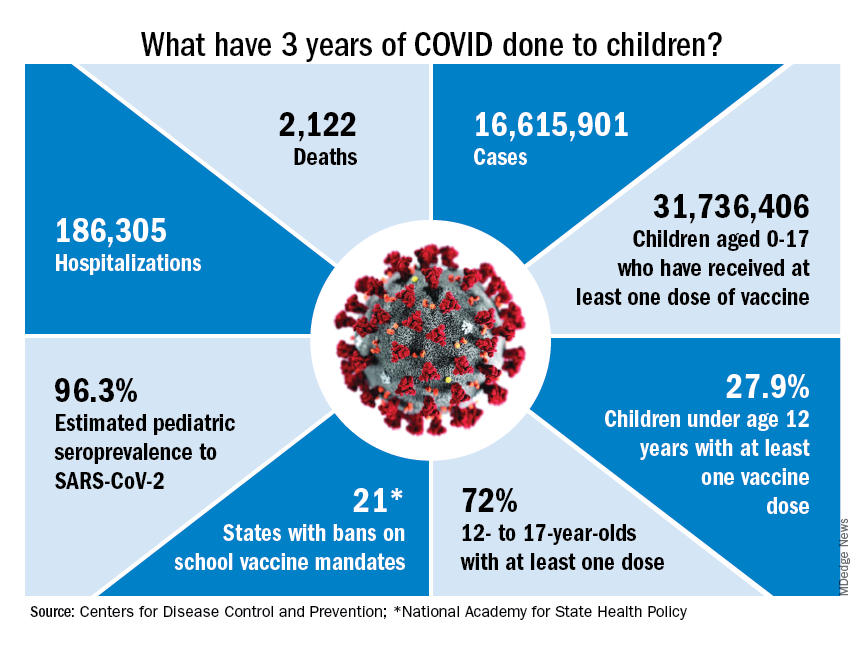

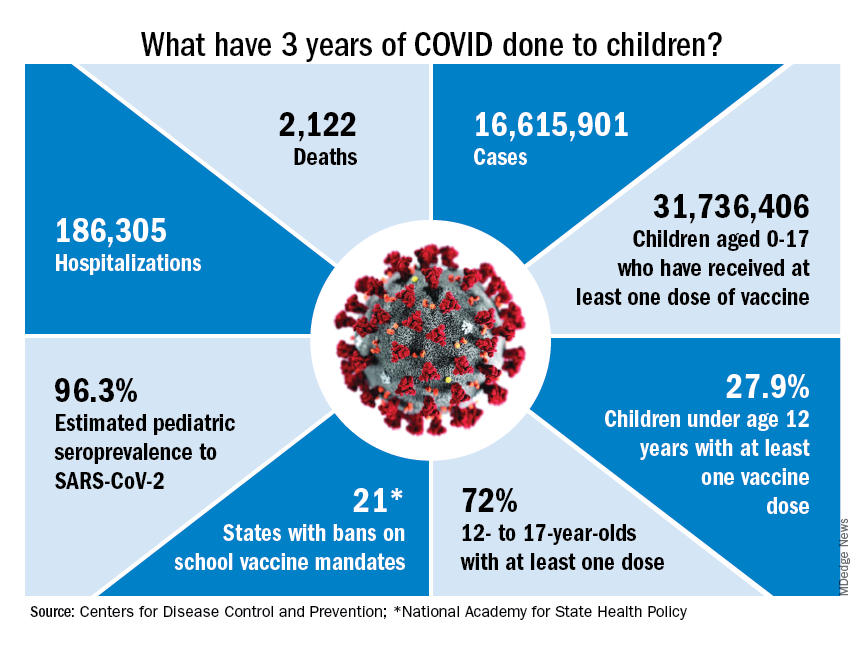

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

Will new guidelines widen the gap in treating childhood obesity?

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can particles in dairy and beef cause cancer and MS?

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Gestational diabetes affects fetal lung development

Lung development in the fetus may be adversely affected by a mother’s gestational diabetes, based on data from in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo studies.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has recently been associated with fetal lung underdevelopment (FLUD) and delayed lung maturation that may lead to immediate respiratory distress in newborns and later chronic lung disease, Pengzheng Chen, PhD, of Shandong University, Jinan, China, and colleagues wrote.

Antenatal corticosteroids are considered an effective treatment for gestational fetal lung underdevelopment, but recent studies have shown adverse effects of these medications, and therefore more research is needed to identify the etiology and pathogenesis of FLUD induced by GDM, they said.

In a study published in the International Journal of Nanomedicine, the researchers collected umbilical cord blood samples from patients with GDM and matched controls at a single hospital in China.

“Using an ex vivo exosome exposure model of fetal lung explants, we observed the morphological alteration of lung explants and evaluated the expression of molecules involved in lung development,” the researchers wrote.

Fetal lung underdevelopment was more common after exposure to exosomes from the umbilical cord plasma of individuals with gestational diabetes mellitus, compared with exosomes from healthy controls.

The researchers also used mouse models to examine the effects of exosomes on fetal lung development in vivo. They found that exosomes associated with GDM impeded the growth, branching morphogenesis, and maturation of fetal lungs in mouse models. In addition, the expression of the apoptotic biomarkers known as BAX, BIM, and cleaved CASPASE-3 was up-regulated in GDMUB-exosomes and HG-exos groups, but the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 was down-regulated; this further supported the negative impact of GDM exomes on fetal lung development, the researchers said.

The researchers then conducted miRNA sequencing, which showed that the miRNA in placenta-derived exosomes from GDM pregnancies were distinct from the miRNA in exosomes from healthy control pregnancies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the impurity of the isolated placenta-derived exosomes from the umbilical cord blood plasma, which were not placenta specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on different stages of lung development, and more research is needed to validate miRNAs and to explore the signally pathways involved in fetal lung development.

However, the study is the first known to demonstrate an adverse effect of GDM on fetal lung development via in vitro, ex vivo, and in vitro models, they said.

“These data highlight an emerging role of placenta-derived exosomes in the pathogenesis of fetal lung underdevelopment in GDM pregnancies, and provide a novel strategy for maternal-fetal communication,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Lung development in the fetus may be adversely affected by a mother’s gestational diabetes, based on data from in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo studies.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has recently been associated with fetal lung underdevelopment (FLUD) and delayed lung maturation that may lead to immediate respiratory distress in newborns and later chronic lung disease, Pengzheng Chen, PhD, of Shandong University, Jinan, China, and colleagues wrote.

Antenatal corticosteroids are considered an effective treatment for gestational fetal lung underdevelopment, but recent studies have shown adverse effects of these medications, and therefore more research is needed to identify the etiology and pathogenesis of FLUD induced by GDM, they said.

In a study published in the International Journal of Nanomedicine, the researchers collected umbilical cord blood samples from patients with GDM and matched controls at a single hospital in China.

“Using an ex vivo exosome exposure model of fetal lung explants, we observed the morphological alteration of lung explants and evaluated the expression of molecules involved in lung development,” the researchers wrote.

Fetal lung underdevelopment was more common after exposure to exosomes from the umbilical cord plasma of individuals with gestational diabetes mellitus, compared with exosomes from healthy controls.

The researchers also used mouse models to examine the effects of exosomes on fetal lung development in vivo. They found that exosomes associated with GDM impeded the growth, branching morphogenesis, and maturation of fetal lungs in mouse models. In addition, the expression of the apoptotic biomarkers known as BAX, BIM, and cleaved CASPASE-3 was up-regulated in GDMUB-exosomes and HG-exos groups, but the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 was down-regulated; this further supported the negative impact of GDM exomes on fetal lung development, the researchers said.

The researchers then conducted miRNA sequencing, which showed that the miRNA in placenta-derived exosomes from GDM pregnancies were distinct from the miRNA in exosomes from healthy control pregnancies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the impurity of the isolated placenta-derived exosomes from the umbilical cord blood plasma, which were not placenta specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on different stages of lung development, and more research is needed to validate miRNAs and to explore the signally pathways involved in fetal lung development.

However, the study is the first known to demonstrate an adverse effect of GDM on fetal lung development via in vitro, ex vivo, and in vitro models, they said.

“These data highlight an emerging role of placenta-derived exosomes in the pathogenesis of fetal lung underdevelopment in GDM pregnancies, and provide a novel strategy for maternal-fetal communication,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Lung development in the fetus may be adversely affected by a mother’s gestational diabetes, based on data from in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo studies.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has recently been associated with fetal lung underdevelopment (FLUD) and delayed lung maturation that may lead to immediate respiratory distress in newborns and later chronic lung disease, Pengzheng Chen, PhD, of Shandong University, Jinan, China, and colleagues wrote.

Antenatal corticosteroids are considered an effective treatment for gestational fetal lung underdevelopment, but recent studies have shown adverse effects of these medications, and therefore more research is needed to identify the etiology and pathogenesis of FLUD induced by GDM, they said.

In a study published in the International Journal of Nanomedicine, the researchers collected umbilical cord blood samples from patients with GDM and matched controls at a single hospital in China.

“Using an ex vivo exosome exposure model of fetal lung explants, we observed the morphological alteration of lung explants and evaluated the expression of molecules involved in lung development,” the researchers wrote.

Fetal lung underdevelopment was more common after exposure to exosomes from the umbilical cord plasma of individuals with gestational diabetes mellitus, compared with exosomes from healthy controls.

The researchers also used mouse models to examine the effects of exosomes on fetal lung development in vivo. They found that exosomes associated with GDM impeded the growth, branching morphogenesis, and maturation of fetal lungs in mouse models. In addition, the expression of the apoptotic biomarkers known as BAX, BIM, and cleaved CASPASE-3 was up-regulated in GDMUB-exosomes and HG-exos groups, but the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 was down-regulated; this further supported the negative impact of GDM exomes on fetal lung development, the researchers said.

The researchers then conducted miRNA sequencing, which showed that the miRNA in placenta-derived exosomes from GDM pregnancies were distinct from the miRNA in exosomes from healthy control pregnancies.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the impurity of the isolated placenta-derived exosomes from the umbilical cord blood plasma, which were not placenta specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on different stages of lung development, and more research is needed to validate miRNAs and to explore the signally pathways involved in fetal lung development.

However, the study is the first known to demonstrate an adverse effect of GDM on fetal lung development via in vitro, ex vivo, and in vitro models, they said.

“These data highlight an emerging role of placenta-derived exosomes in the pathogenesis of fetal lung underdevelopment in GDM pregnancies, and provide a novel strategy for maternal-fetal communication,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NANOMEDICINE

Are early childhood viral infections linked with asthma?

MARSEILLE, France – It is well known that viral infections, especially respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus (RV), exacerbate symptoms of asthma. But could they also play a part in triggering the onset of asthma?

The link between RSV and RV infections in early childhood and the development of asthma symptoms is well established, said Camille Taillé, MD, PhD, of the department of respiratory medicine and the rare diseases center of excellence at Bichat Hospital, Paris. But getting asthma is probably not just a matter of having a viral infection at a young age or of having a severe form of it. Gene polymorphisms, immune system disorders, and preexisting atopy are also associated with the risk of asthma. This was the focus of the 27th French-language respiratory medicine conference, held in Marseille, France.

RV and RSV

Persons with asthma are vulnerable to certain viral respiratory infections, in particular the flu and RV, which can exacerbate asthma symptoms. Inhaled corticosteroids have an overall protective effect against viral-induced exacerbations. For worsening asthma symptoms during an epidemic or pandemic, there is no contraindication to inhaled or oral corticosteroids.

Young children from the time of birth to 4 years of age are particularly susceptible to viral respiratory infections. According to data from France’s clinical surveillance network, Sentinelles, from the period covering winter 2021-2022, the rate of incidence per 100,000 inhabitants was systematically greater for the 0 to 4-year age range than for older age ranges.

Of the most common viruses that infect young children, RV, the virus that causes the common cold, is a nonenveloped RNA virus from the enterovirus family. There are 160 types, which are classified into three strains (A, B, and C). Of those strains, A and C confer the most severe infections. The virus is highly variable, which makes developing a vaccine challenging. The virus circulates year round, usually peaking in the fall and at the end of spring. RSV is an RNA virus that is classed as a respiratory virus. It comprises two serotypes: type A and B. Almost all children will have been infected with RSV by the time they are 2 years old. Epidemics occur each year during winter or in early spring in temperate climates. Vaccines are currently being developed and will soon be marketed. A monoclonal antibody (palivizumab), which targets fusion proteins of the virus, is available as prophylactic treatment for at-risk children.

RSV infection

During an RSV infection, the severe inflammation of the bronchial and alveolar wall causes acute respiratory distress. “But not all infants will develop severe forms of bronchiolitis,” said Dr. Taillé. “The risk factors for the severe form of the illness are well known: being under 6 months of age, prematurity, comorbidities (neurovascular, cardiovascular, respiratory, etc.), history of a stay in a neonatal intensive care unit at birth, living in low socioeconomic status towns, and exposure to smoking.”

Asthma development

The issue of whether or not viral diseases cause asthma has been the subject of intense debate. The studies are starting to stack up, however. They seem to show that RSV or RV infections are associated with the risk of subsequent asthma development. “For example, in a study published in 2022,” said Dr. Taillé, “in children admitted with an RSV infection, 60% of those who had been admitted to neonatal intensive care presented with symptoms of asthma between 3 and 6 years of age, compared with 18% of those who had had a milder case of RSV (admitted to nonintensive care settings). A serious RSV infection is a risk factor for later development of asthma.”

However, the link between RSV and later onset of asthma is also seen in milder cases of the infection. The American COAST study was designed to examine the effect of childhood respiratory infections on the risk of developing asthma. Researchers followed 259 newborns prospectively for 1, 3, and 6 years. To qualify, at least one parent was required to have respiratory allergies (defined as one or more positive aeroallergen skin tests) or a history of physician-diagnosed asthma. Regular samples taken during infectious episodes identified a virus in 90% of cases.

“We now know that RSV is not the only pathogen responsible for bronchiolitis. RV is often found, now that it can routinely be detected by PCR tests,” said Dr. Taillé. In the COAST study, the onset of wheezing during an RSV or RV infection in children aged 0-3 years was associated with an increased risk of asthma at 6 years of age. Globally, 28% of children infected by either virus were deemed to have asthma at 6 years of age. “There is clearly a link between having had a respiratory virus like RV or RSV and getting asthma symptoms at 6 years of age,” said Dr. Taillé. “What’s more, the effect of RV is not changed in this study by allergic sensitization.”

Many articles have been published on this topic. The results of cohort studies, from Japan to Finland and the United States, Italy, and Australia, are consistent with each other. Persons who have contracted RV or RSV are more likely to suffer from recurrent wheezing or asthma, especially if the infection is contracted in infancy or if it is severe. “Some studies even suggest that viral-induced asthma is more severe,” said Dr. Taillé. “For example, a Scottish study ... showed that children with a previous history of RSV infection had more hospital admissions and required more medication than asthmatics with no history of an RSV infection, suggesting the link between a previous history of RSV infection and the development of a more severe form of asthma.”

Reaching adulthood

Few longitudinal cohorts explore this issue in adulthood. A relatively old study reported an increased rate of asthma among adults who had required hospital admission for bronchiolitis in early childhood, as well as the effect on respiratory function. A 2023 study of the effects of respiratory illnesses in childhood reported similar findings. The authors evaluated lung structure and function via CT scans of 39 patients aged 26 years and concluded that participants who had been infected with RSV in childhood presented with increased air trapping, which is suggestive of airway abnormalities, possibly linked to a direct effect of viruses on lung development.

Mechanisms of action

“The real question is understanding if it’s the virus itself that causes asthma, or if the virus is simply uncovering underlying asthma in predisposed children,” said Dr. Taillé. From 30% to 40% of children who have had RSV will go on to develop wheezing or asthma in childhood. This observation suggests that there are factors favoring the development of asthma after infection with RSV. It has been shown that there is a genetic predisposition for RV. The roles of cigarette smoke, air pollution, environmental exposures to allergens, rapid urbanization, low vitamin D levels, low maternal omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid levels, maternal stress, and depression have also been highlighted.

It would seem that RSV and RV are a bit different. RV is thought to be associated with the development of asthma and wheezing, especially in people with a preexisting atopy or a reduced interferon immune response, while RSV, which occurs at a younger age and among the most vulnerable populations, seems to act independently of a person’s predisposition to allergies. RV stands out from other viral factors, owing to its tendency to create a Th2-biased inflammatory environment and its association with specific risk genes in people predisposed to asthma development (CDHR3).

Dr. Taillé has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MARSEILLE, France – It is well known that viral infections, especially respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus (RV), exacerbate symptoms of asthma. But could they also play a part in triggering the onset of asthma?

The link between RSV and RV infections in early childhood and the development of asthma symptoms is well established, said Camille Taillé, MD, PhD, of the department of respiratory medicine and the rare diseases center of excellence at Bichat Hospital, Paris. But getting asthma is probably not just a matter of having a viral infection at a young age or of having a severe form of it. Gene polymorphisms, immune system disorders, and preexisting atopy are also associated with the risk of asthma. This was the focus of the 27th French-language respiratory medicine conference, held in Marseille, France.

RV and RSV

Persons with asthma are vulnerable to certain viral respiratory infections, in particular the flu and RV, which can exacerbate asthma symptoms. Inhaled corticosteroids have an overall protective effect against viral-induced exacerbations. For worsening asthma symptoms during an epidemic or pandemic, there is no contraindication to inhaled or oral corticosteroids.

Young children from the time of birth to 4 years of age are particularly susceptible to viral respiratory infections. According to data from France’s clinical surveillance network, Sentinelles, from the period covering winter 2021-2022, the rate of incidence per 100,000 inhabitants was systematically greater for the 0 to 4-year age range than for older age ranges.

Of the most common viruses that infect young children, RV, the virus that causes the common cold, is a nonenveloped RNA virus from the enterovirus family. There are 160 types, which are classified into three strains (A, B, and C). Of those strains, A and C confer the most severe infections. The virus is highly variable, which makes developing a vaccine challenging. The virus circulates year round, usually peaking in the fall and at the end of spring. RSV is an RNA virus that is classed as a respiratory virus. It comprises two serotypes: type A and B. Almost all children will have been infected with RSV by the time they are 2 years old. Epidemics occur each year during winter or in early spring in temperate climates. Vaccines are currently being developed and will soon be marketed. A monoclonal antibody (palivizumab), which targets fusion proteins of the virus, is available as prophylactic treatment for at-risk children.

RSV infection

During an RSV infection, the severe inflammation of the bronchial and alveolar wall causes acute respiratory distress. “But not all infants will develop severe forms of bronchiolitis,” said Dr. Taillé. “The risk factors for the severe form of the illness are well known: being under 6 months of age, prematurity, comorbidities (neurovascular, cardiovascular, respiratory, etc.), history of a stay in a neonatal intensive care unit at birth, living in low socioeconomic status towns, and exposure to smoking.”

Asthma development

The issue of whether or not viral diseases cause asthma has been the subject of intense debate. The studies are starting to stack up, however. They seem to show that RSV or RV infections are associated with the risk of subsequent asthma development. “For example, in a study published in 2022,” said Dr. Taillé, “in children admitted with an RSV infection, 60% of those who had been admitted to neonatal intensive care presented with symptoms of asthma between 3 and 6 years of age, compared with 18% of those who had had a milder case of RSV (admitted to nonintensive care settings). A serious RSV infection is a risk factor for later development of asthma.”

However, the link between RSV and later onset of asthma is also seen in milder cases of the infection. The American COAST study was designed to examine the effect of childhood respiratory infections on the risk of developing asthma. Researchers followed 259 newborns prospectively for 1, 3, and 6 years. To qualify, at least one parent was required to have respiratory allergies (defined as one or more positive aeroallergen skin tests) or a history of physician-diagnosed asthma. Regular samples taken during infectious episodes identified a virus in 90% of cases.

“We now know that RSV is not the only pathogen responsible for bronchiolitis. RV is often found, now that it can routinely be detected by PCR tests,” said Dr. Taillé. In the COAST study, the onset of wheezing during an RSV or RV infection in children aged 0-3 years was associated with an increased risk of asthma at 6 years of age. Globally, 28% of children infected by either virus were deemed to have asthma at 6 years of age. “There is clearly a link between having had a respiratory virus like RV or RSV and getting asthma symptoms at 6 years of age,” said Dr. Taillé. “What’s more, the effect of RV is not changed in this study by allergic sensitization.”

Many articles have been published on this topic. The results of cohort studies, from Japan to Finland and the United States, Italy, and Australia, are consistent with each other. Persons who have contracted RV or RSV are more likely to suffer from recurrent wheezing or asthma, especially if the infection is contracted in infancy or if it is severe. “Some studies even suggest that viral-induced asthma is more severe,” said Dr. Taillé. “For example, a Scottish study ... showed that children with a previous history of RSV infection had more hospital admissions and required more medication than asthmatics with no history of an RSV infection, suggesting the link between a previous history of RSV infection and the development of a more severe form of asthma.”

Reaching adulthood

Few longitudinal cohorts explore this issue in adulthood. A relatively old study reported an increased rate of asthma among adults who had required hospital admission for bronchiolitis in early childhood, as well as the effect on respiratory function. A 2023 study of the effects of respiratory illnesses in childhood reported similar findings. The authors evaluated lung structure and function via CT scans of 39 patients aged 26 years and concluded that participants who had been infected with RSV in childhood presented with increased air trapping, which is suggestive of airway abnormalities, possibly linked to a direct effect of viruses on lung development.

Mechanisms of action

“The real question is understanding if it’s the virus itself that causes asthma, or if the virus is simply uncovering underlying asthma in predisposed children,” said Dr. Taillé. From 30% to 40% of children who have had RSV will go on to develop wheezing or asthma in childhood. This observation suggests that there are factors favoring the development of asthma after infection with RSV. It has been shown that there is a genetic predisposition for RV. The roles of cigarette smoke, air pollution, environmental exposures to allergens, rapid urbanization, low vitamin D levels, low maternal omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid levels, maternal stress, and depression have also been highlighted.

It would seem that RSV and RV are a bit different. RV is thought to be associated with the development of asthma and wheezing, especially in people with a preexisting atopy or a reduced interferon immune response, while RSV, which occurs at a younger age and among the most vulnerable populations, seems to act independently of a person’s predisposition to allergies. RV stands out from other viral factors, owing to its tendency to create a Th2-biased inflammatory environment and its association with specific risk genes in people predisposed to asthma development (CDHR3).

Dr. Taillé has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MARSEILLE, France – It is well known that viral infections, especially respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus (RV), exacerbate symptoms of asthma. But could they also play a part in triggering the onset of asthma?

The link between RSV and RV infections in early childhood and the development of asthma symptoms is well established, said Camille Taillé, MD, PhD, of the department of respiratory medicine and the rare diseases center of excellence at Bichat Hospital, Paris. But getting asthma is probably not just a matter of having a viral infection at a young age or of having a severe form of it. Gene polymorphisms, immune system disorders, and preexisting atopy are also associated with the risk of asthma. This was the focus of the 27th French-language respiratory medicine conference, held in Marseille, France.

RV and RSV

Persons with asthma are vulnerable to certain viral respiratory infections, in particular the flu and RV, which can exacerbate asthma symptoms. Inhaled corticosteroids have an overall protective effect against viral-induced exacerbations. For worsening asthma symptoms during an epidemic or pandemic, there is no contraindication to inhaled or oral corticosteroids.

Young children from the time of birth to 4 years of age are particularly susceptible to viral respiratory infections. According to data from France’s clinical surveillance network, Sentinelles, from the period covering winter 2021-2022, the rate of incidence per 100,000 inhabitants was systematically greater for the 0 to 4-year age range than for older age ranges.