User login

VIDEO: New directions in bariatric surgery quality measures

CHICAGO – Bariatric surgery has made great strides in safety and efficacy – so many, in fact, that the field is ready to focus on a new range of quality goals, explained Dr. John Morton.

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, Dr. Morton, chief of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, discussed how new quality targets, such as 30-day readmissions, could improve bariatric surgery outcomes and boost patient satisfaction.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Bariatric surgery has made great strides in safety and efficacy – so many, in fact, that the field is ready to focus on a new range of quality goals, explained Dr. John Morton.

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, Dr. Morton, chief of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, discussed how new quality targets, such as 30-day readmissions, could improve bariatric surgery outcomes and boost patient satisfaction.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Bariatric surgery has made great strides in safety and efficacy – so many, in fact, that the field is ready to focus on a new range of quality goals, explained Dr. John Morton.

In an interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week, Dr. Morton, chief of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, discussed how new quality targets, such as 30-day readmissions, could improve bariatric surgery outcomes and boost patient satisfaction.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

At DDW 2014

Patient satisfaction not always linked to hospital safety, effectiveness

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

AT ASA 2014

Major finding: In the sample, 62% of high-volume hospitals achieved high patient satisfaction, vs. 38% of low-volume hospitals. Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of HCAHPS surveys at 171 U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

FDA proposes stricter review of surgical mesh products for prolapse repair

Surgical mesh products used for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse would be reclassified as high-risk devices, and manufacturers would have to submit approval applications, under a proposed order issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

These proposals address the serious health risks that have been associated with surgical mesh in this setting, and reflect the recommendations made by the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices panel at a meeting in September 2011, according to the FDA statement announcing the proposal issued on April 29.

"If these proposals are finalized, we will require manufacturers to provide premarket clinical data to demonstrate a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for surgical mesh used to treat transvaginal POP [pelvic organ prolapse] repair," Dr. William Maisel, deputy director of science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The proposal to categorize these devices as class III devices is "based on the tentative determination that general controls by themselves are insufficient to provide reasonable assurance of the safety and effectiveness of these devices, and there is sufficient information to establish special controls to provide such assurance," according to the FDA document that is being published in the Federal Register.

Surgical mesh products have been regulated as class II, moderate-risk devices, which usually are exempt from premarket review; approval of class II devices is based on whether the FDA determines that the device is "substantially equivalent" to a similar device already on the market. Class III devices require safety and effectiveness data to be submitted and reviewed for approval.

The FDA issued notifications about serious adverse events associated with the use of surgical mesh devices to repair POP in 2008 and 2011, which have included mesh erosion through the vagina, pain, infection, bleeding, dyspareunia, organ perforation, and urinary problems – as well as recurrent prolapse, neuromuscular problems, and vaginal scarring/shrinkage.

The FDA is also proposing that the urogynecologic surgical instruments that are included in the mesh implant kits be reclassified from low-risk (class I) to moderate-risk devices. The agency has identified risks associated with the use of these devices to include organ perforation or injury and bleeding, as well as "damage to blood vessels, nerves, connective tissue, and other structures." Such injuries may be due to "improperly designed and/or misused surgical mesh instrumentation," according to the document posted in the Federal Register.

Comments on the proposals can be submitted to the FDA for 90 days after the May 1 publication of the proposal in the Federal Register electronically, through www.regulations.gov; or can be sent to the Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Include Docket No. FDA-2014-N-0297. As of May 1, the proposal will be available here.

Surgical mesh products used for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse would be reclassified as high-risk devices, and manufacturers would have to submit approval applications, under a proposed order issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

These proposals address the serious health risks that have been associated with surgical mesh in this setting, and reflect the recommendations made by the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices panel at a meeting in September 2011, according to the FDA statement announcing the proposal issued on April 29.

"If these proposals are finalized, we will require manufacturers to provide premarket clinical data to demonstrate a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for surgical mesh used to treat transvaginal POP [pelvic organ prolapse] repair," Dr. William Maisel, deputy director of science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The proposal to categorize these devices as class III devices is "based on the tentative determination that general controls by themselves are insufficient to provide reasonable assurance of the safety and effectiveness of these devices, and there is sufficient information to establish special controls to provide such assurance," according to the FDA document that is being published in the Federal Register.

Surgical mesh products have been regulated as class II, moderate-risk devices, which usually are exempt from premarket review; approval of class II devices is based on whether the FDA determines that the device is "substantially equivalent" to a similar device already on the market. Class III devices require safety and effectiveness data to be submitted and reviewed for approval.

The FDA issued notifications about serious adverse events associated with the use of surgical mesh devices to repair POP in 2008 and 2011, which have included mesh erosion through the vagina, pain, infection, bleeding, dyspareunia, organ perforation, and urinary problems – as well as recurrent prolapse, neuromuscular problems, and vaginal scarring/shrinkage.

The FDA is also proposing that the urogynecologic surgical instruments that are included in the mesh implant kits be reclassified from low-risk (class I) to moderate-risk devices. The agency has identified risks associated with the use of these devices to include organ perforation or injury and bleeding, as well as "damage to blood vessels, nerves, connective tissue, and other structures." Such injuries may be due to "improperly designed and/or misused surgical mesh instrumentation," according to the document posted in the Federal Register.

Comments on the proposals can be submitted to the FDA for 90 days after the May 1 publication of the proposal in the Federal Register electronically, through www.regulations.gov; or can be sent to the Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Include Docket No. FDA-2014-N-0297. As of May 1, the proposal will be available here.

Surgical mesh products used for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse would be reclassified as high-risk devices, and manufacturers would have to submit approval applications, under a proposed order issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

These proposals address the serious health risks that have been associated with surgical mesh in this setting, and reflect the recommendations made by the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices panel at a meeting in September 2011, according to the FDA statement announcing the proposal issued on April 29.

"If these proposals are finalized, we will require manufacturers to provide premarket clinical data to demonstrate a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for surgical mesh used to treat transvaginal POP [pelvic organ prolapse] repair," Dr. William Maisel, deputy director of science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The proposal to categorize these devices as class III devices is "based on the tentative determination that general controls by themselves are insufficient to provide reasonable assurance of the safety and effectiveness of these devices, and there is sufficient information to establish special controls to provide such assurance," according to the FDA document that is being published in the Federal Register.

Surgical mesh products have been regulated as class II, moderate-risk devices, which usually are exempt from premarket review; approval of class II devices is based on whether the FDA determines that the device is "substantially equivalent" to a similar device already on the market. Class III devices require safety and effectiveness data to be submitted and reviewed for approval.

The FDA issued notifications about serious adverse events associated with the use of surgical mesh devices to repair POP in 2008 and 2011, which have included mesh erosion through the vagina, pain, infection, bleeding, dyspareunia, organ perforation, and urinary problems – as well as recurrent prolapse, neuromuscular problems, and vaginal scarring/shrinkage.

The FDA is also proposing that the urogynecologic surgical instruments that are included in the mesh implant kits be reclassified from low-risk (class I) to moderate-risk devices. The agency has identified risks associated with the use of these devices to include organ perforation or injury and bleeding, as well as "damage to blood vessels, nerves, connective tissue, and other structures." Such injuries may be due to "improperly designed and/or misused surgical mesh instrumentation," according to the document posted in the Federal Register.

Comments on the proposals can be submitted to the FDA for 90 days after the May 1 publication of the proposal in the Federal Register electronically, through www.regulations.gov; or can be sent to the Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Include Docket No. FDA-2014-N-0297. As of May 1, the proposal will be available here.

Short CAM-S delirium scale predicted clinical outcomes

A new delirium scoring system has shown excellent correlation with clinical outcomes in hospitalized elderly patients, including length of stay, functional decline, and death, investigators report.

In both short and long form, the Confusion Assessment Methods-S (CAM-S) is designed to complement the existing CAM, Dr. Sharon Inouye and her colleagues reported in the April 14 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine (2014;160:526-33).

"The short form (5-minute completion and scoring time), which is based on the CAM diagnostic algorithm alone, is quicker and simpler to rate; however, the long form (10-minute completion and scoring time) provides a broader range of severity scores in delirium and no-delirium groups," wrote Dr. Inouye of the Institute for Aging Research, Boston, and her coauthors.

"Unlike the Delirium Rating Scale, a clinician rater is not required for the CAM-S. Instead, well-trained research assistants can reliably conduct the assessments," the researchers wrote.

Both the short-form and long-form CAM-S instruments were validated in a group of 919 patients aged 70 years or older, who were scheduled for major surgery. The cohort was drawn from two extant study groups: the ongoing SAGES (Successful Aging After Elective Surgery) study,and Project Recovery, which ran from 1995 to 1998. Delirium was first rated by the existing CAM, and then according to the two versions of CAM-S.

The short-form CAM-S rates patients on four features of the CAM: symptom fluctuation, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The most severe score is a 7. The longer form is based on 10 features, which also include disorientation, memory impairment, perceptual disturbances, psychomotor agitation, and sleep-wake cycle disturbance. The most severe score is a 19.

The measures had excellent correlation with each other, and with several clinical outcomes, the investigators said.

Length of hospital stay increased with increasing delirium severity across both forms, with an adjusted mean stay of 6.5 days for no delirium to almost 13 days with high severity in the short form. In the long form, length of stay increased from about 6 days to 12 days.

Hospital costs also tracked severity, ranging from an adjusted mean of $5,100 for no delirium to $13,200 for severe delirium in the short form. A similar pattern emerged in the long form, ranging from $4,200 to $11,400.

Functional decline was also highly correlated with score. On the short form, it occurred in 36%-68% of patients, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 25%-61%. Cognitive decline showed a similar pattern.

In the short form, the cumulative adjusted rates of death within 90 days ranged from 7% to 27%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 7%-22%.

In the composite outcome of death or nursing home placement, results on the short form ranged from 15% to 51%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 13%-48%

While the Project Recovery data are more than 16 years old, the researchers said that this time lapse is not an issue because their primary interest is in comparison of outcomes among severity groups, which minimizes the importance of the internal values.

Also, "there may be inherent dependencies between CAM-S score and adverse outcomes," investigators wrote. "For example, patients with longer lengths of stay may have had higher CAM-S scores because of more opportunities for measurement."

The CAM-S score requires validation in groups younger than the age 70-plus patients addressed in the current study, researchers noted.

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. None of the authors reported having any financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

A new delirium scoring system has shown excellent correlation with clinical outcomes in hospitalized elderly patients, including length of stay, functional decline, and death, investigators report.

In both short and long form, the Confusion Assessment Methods-S (CAM-S) is designed to complement the existing CAM, Dr. Sharon Inouye and her colleagues reported in the April 14 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine (2014;160:526-33).

"The short form (5-minute completion and scoring time), which is based on the CAM diagnostic algorithm alone, is quicker and simpler to rate; however, the long form (10-minute completion and scoring time) provides a broader range of severity scores in delirium and no-delirium groups," wrote Dr. Inouye of the Institute for Aging Research, Boston, and her coauthors.

"Unlike the Delirium Rating Scale, a clinician rater is not required for the CAM-S. Instead, well-trained research assistants can reliably conduct the assessments," the researchers wrote.

Both the short-form and long-form CAM-S instruments were validated in a group of 919 patients aged 70 years or older, who were scheduled for major surgery. The cohort was drawn from two extant study groups: the ongoing SAGES (Successful Aging After Elective Surgery) study,and Project Recovery, which ran from 1995 to 1998. Delirium was first rated by the existing CAM, and then according to the two versions of CAM-S.

The short-form CAM-S rates patients on four features of the CAM: symptom fluctuation, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The most severe score is a 7. The longer form is based on 10 features, which also include disorientation, memory impairment, perceptual disturbances, psychomotor agitation, and sleep-wake cycle disturbance. The most severe score is a 19.

The measures had excellent correlation with each other, and with several clinical outcomes, the investigators said.

Length of hospital stay increased with increasing delirium severity across both forms, with an adjusted mean stay of 6.5 days for no delirium to almost 13 days with high severity in the short form. In the long form, length of stay increased from about 6 days to 12 days.

Hospital costs also tracked severity, ranging from an adjusted mean of $5,100 for no delirium to $13,200 for severe delirium in the short form. A similar pattern emerged in the long form, ranging from $4,200 to $11,400.

Functional decline was also highly correlated with score. On the short form, it occurred in 36%-68% of patients, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 25%-61%. Cognitive decline showed a similar pattern.

In the short form, the cumulative adjusted rates of death within 90 days ranged from 7% to 27%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 7%-22%.

In the composite outcome of death or nursing home placement, results on the short form ranged from 15% to 51%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 13%-48%

While the Project Recovery data are more than 16 years old, the researchers said that this time lapse is not an issue because their primary interest is in comparison of outcomes among severity groups, which minimizes the importance of the internal values.

Also, "there may be inherent dependencies between CAM-S score and adverse outcomes," investigators wrote. "For example, patients with longer lengths of stay may have had higher CAM-S scores because of more opportunities for measurement."

The CAM-S score requires validation in groups younger than the age 70-plus patients addressed in the current study, researchers noted.

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. None of the authors reported having any financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

A new delirium scoring system has shown excellent correlation with clinical outcomes in hospitalized elderly patients, including length of stay, functional decline, and death, investigators report.

In both short and long form, the Confusion Assessment Methods-S (CAM-S) is designed to complement the existing CAM, Dr. Sharon Inouye and her colleagues reported in the April 14 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine (2014;160:526-33).

"The short form (5-minute completion and scoring time), which is based on the CAM diagnostic algorithm alone, is quicker and simpler to rate; however, the long form (10-minute completion and scoring time) provides a broader range of severity scores in delirium and no-delirium groups," wrote Dr. Inouye of the Institute for Aging Research, Boston, and her coauthors.

"Unlike the Delirium Rating Scale, a clinician rater is not required for the CAM-S. Instead, well-trained research assistants can reliably conduct the assessments," the researchers wrote.

Both the short-form and long-form CAM-S instruments were validated in a group of 919 patients aged 70 years or older, who were scheduled for major surgery. The cohort was drawn from two extant study groups: the ongoing SAGES (Successful Aging After Elective Surgery) study,and Project Recovery, which ran from 1995 to 1998. Delirium was first rated by the existing CAM, and then according to the two versions of CAM-S.

The short-form CAM-S rates patients on four features of the CAM: symptom fluctuation, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The most severe score is a 7. The longer form is based on 10 features, which also include disorientation, memory impairment, perceptual disturbances, psychomotor agitation, and sleep-wake cycle disturbance. The most severe score is a 19.

The measures had excellent correlation with each other, and with several clinical outcomes, the investigators said.

Length of hospital stay increased with increasing delirium severity across both forms, with an adjusted mean stay of 6.5 days for no delirium to almost 13 days with high severity in the short form. In the long form, length of stay increased from about 6 days to 12 days.

Hospital costs also tracked severity, ranging from an adjusted mean of $5,100 for no delirium to $13,200 for severe delirium in the short form. A similar pattern emerged in the long form, ranging from $4,200 to $11,400.

Functional decline was also highly correlated with score. On the short form, it occurred in 36%-68% of patients, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 25%-61%. Cognitive decline showed a similar pattern.

In the short form, the cumulative adjusted rates of death within 90 days ranged from 7% to 27%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 7%-22%.

In the composite outcome of death or nursing home placement, results on the short form ranged from 15% to 51%, depending on severity. In the long form, the range was 13%-48%

While the Project Recovery data are more than 16 years old, the researchers said that this time lapse is not an issue because their primary interest is in comparison of outcomes among severity groups, which minimizes the importance of the internal values.

Also, "there may be inherent dependencies between CAM-S score and adverse outcomes," investigators wrote. "For example, patients with longer lengths of stay may have had higher CAM-S scores because of more opportunities for measurement."

The CAM-S score requires validation in groups younger than the age 70-plus patients addressed in the current study, researchers noted.

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. None of the authors reported having any financial declarations.

On Twitter @alz_gal

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Major finding: Two versions of the CAM-S delirium scale were predictive of major clinical outcomes in the elderly, including death within 30 days of surgery (7%-27%, depending on severity scores).

Data source: CAM-S was validated in a group of 919 patients.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Aging funded the study. Neither Dr. Inouye nor any of the coauthors had any financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Feeding elderly patients after hip surgery

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE prophylaxis mantra

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Angiography timing shown not a risk for AKI in most cardiac surgery

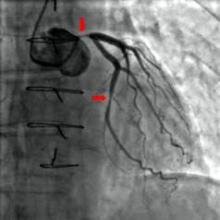

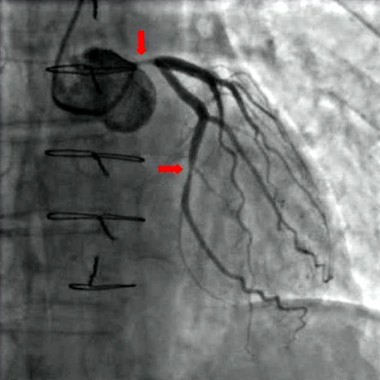

Acute kidney injury is a serious adverse effect of cardiac surgery, and contrast-induced nephropathy due to coronary angiography has been suggested as a potentially important component. However, the results of a retrospective study of more than 2,500 patients showed that acute kidney injury is significantly higher only in those patients who have combined cardiac surgery within 24 hours of catheterization.

The study by Dr. Giovanni Mariscalco of the Varese (Italy) University Hospital, and his colleagues assessed all consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery at the hospital between Jan. 1, 2005, and Dec. 31, 2011. The operations performed were isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve surgery with or without concomitant CABG, and proximal aortic procedures. After exclusion of patients who did not undergo cardiopulmonary bypass, a known major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI), and those who died during the procedure, a total of 2,504 patients remained. These patients had a mean age of 68.4 years and consisted mostly of men (67.3%), according to the report in the April issue of the International Journal of Cardiology.

The primary endpoint of the study was the effect of timing between cardiac catheterization and surgery on the development of AKI. Postoperative AKI was defined by the consensus RIFLE criteria (risk, injury, failure, loss of function, and end-stage renal disease), using the maximal change in serum creatinine and the estimated glomerular filtration rate during the first 7 days after surgery, compared with baseline values collected the day before surgery or immediately before surgery when cardiac catheterization was performed on the same day as the operation.

The researchers defined AKI as a 50% increase in the postoperative serum creatinine over baseline. Propensity analysis was used to match patients, who were then assessed both pre- and postmatch.

The overall incidence of AKI after surgery was 9.2% (230/2,504 patients). A breakdown by procedure showed that AKI occurred in 7.7% of isolated CABG patients, 12.2% of isolated valve patients, 9.5% of combined-procedure patients, and 9.5% of the proximal aorta surgery patients (Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;173:46-54).

As has been seen in previous studies, AKI was associated with patient-specific pre- and perioperative variables, including increased patient age, added comorbidities, longer cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times, higher rates of combined procedures, and the use of intra-aortic balloon pumps.

Unadjusted analysis of the total cohort showed AKI was significantly associated with contrast exposure within 1 day of surgery. However, in multivariable analysis, the time interval between catheterization and surgery as both a categorical and continuous variable was not an independent predictor of postoperative AKI for the total cohort. In subgroup analysis, only the combined valve and CABG group of patients showed an independent association of contrast exposure within 1 day before surgery and AKI in both the prematched (odds ratio, 2.69; P = .004) and the postmatched (OR, 3.68; P = .014) groups.

"Avoiding surgery within 1 day after contrast exposure should be recommended for patients undergoing valve surgery with concomitant CABG only. For other types of cardiac operations, delaying cardiac surgery after contrast exposure seems not to be justified," the researchers concluded.

Study limitations cited include its retrospective and single-institution nature and the statistical effect of different numbers of observations among the surgery groups. Patients affected with AKI also had higher rates of other postoperative complications, and AKI in some cases may have been the result of these rather than an independent event.

he study was supported by the Fondazione Cesare Bartorelli. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Acute kidney injury is a serious adverse effect of cardiac surgery, and contrast-induced nephropathy due to coronary angiography has been suggested as a potentially important component. However, the results of a retrospective study of more than 2,500 patients showed that acute kidney injury is significantly higher only in those patients who have combined cardiac surgery within 24 hours of catheterization.

The study by Dr. Giovanni Mariscalco of the Varese (Italy) University Hospital, and his colleagues assessed all consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery at the hospital between Jan. 1, 2005, and Dec. 31, 2011. The operations performed were isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve surgery with or without concomitant CABG, and proximal aortic procedures. After exclusion of patients who did not undergo cardiopulmonary bypass, a known major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI), and those who died during the procedure, a total of 2,504 patients remained. These patients had a mean age of 68.4 years and consisted mostly of men (67.3%), according to the report in the April issue of the International Journal of Cardiology.

The primary endpoint of the study was the effect of timing between cardiac catheterization and surgery on the development of AKI. Postoperative AKI was defined by the consensus RIFLE criteria (risk, injury, failure, loss of function, and end-stage renal disease), using the maximal change in serum creatinine and the estimated glomerular filtration rate during the first 7 days after surgery, compared with baseline values collected the day before surgery or immediately before surgery when cardiac catheterization was performed on the same day as the operation.

The researchers defined AKI as a 50% increase in the postoperative serum creatinine over baseline. Propensity analysis was used to match patients, who were then assessed both pre- and postmatch.

The overall incidence of AKI after surgery was 9.2% (230/2,504 patients). A breakdown by procedure showed that AKI occurred in 7.7% of isolated CABG patients, 12.2% of isolated valve patients, 9.5% of combined-procedure patients, and 9.5% of the proximal aorta surgery patients (Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;173:46-54).

As has been seen in previous studies, AKI was associated with patient-specific pre- and perioperative variables, including increased patient age, added comorbidities, longer cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times, higher rates of combined procedures, and the use of intra-aortic balloon pumps.

Unadjusted analysis of the total cohort showed AKI was significantly associated with contrast exposure within 1 day of surgery. However, in multivariable analysis, the time interval between catheterization and surgery as both a categorical and continuous variable was not an independent predictor of postoperative AKI for the total cohort. In subgroup analysis, only the combined valve and CABG group of patients showed an independent association of contrast exposure within 1 day before surgery and AKI in both the prematched (odds ratio, 2.69; P = .004) and the postmatched (OR, 3.68; P = .014) groups.

"Avoiding surgery within 1 day after contrast exposure should be recommended for patients undergoing valve surgery with concomitant CABG only. For other types of cardiac operations, delaying cardiac surgery after contrast exposure seems not to be justified," the researchers concluded.

Study limitations cited include its retrospective and single-institution nature and the statistical effect of different numbers of observations among the surgery groups. Patients affected with AKI also had higher rates of other postoperative complications, and AKI in some cases may have been the result of these rather than an independent event.

he study was supported by the Fondazione Cesare Bartorelli. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Acute kidney injury is a serious adverse effect of cardiac surgery, and contrast-induced nephropathy due to coronary angiography has been suggested as a potentially important component. However, the results of a retrospective study of more than 2,500 patients showed that acute kidney injury is significantly higher only in those patients who have combined cardiac surgery within 24 hours of catheterization.

The study by Dr. Giovanni Mariscalco of the Varese (Italy) University Hospital, and his colleagues assessed all consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery at the hospital between Jan. 1, 2005, and Dec. 31, 2011. The operations performed were isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve surgery with or without concomitant CABG, and proximal aortic procedures. After exclusion of patients who did not undergo cardiopulmonary bypass, a known major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI), and those who died during the procedure, a total of 2,504 patients remained. These patients had a mean age of 68.4 years and consisted mostly of men (67.3%), according to the report in the April issue of the International Journal of Cardiology.

The primary endpoint of the study was the effect of timing between cardiac catheterization and surgery on the development of AKI. Postoperative AKI was defined by the consensus RIFLE criteria (risk, injury, failure, loss of function, and end-stage renal disease), using the maximal change in serum creatinine and the estimated glomerular filtration rate during the first 7 days after surgery, compared with baseline values collected the day before surgery or immediately before surgery when cardiac catheterization was performed on the same day as the operation.

The researchers defined AKI as a 50% increase in the postoperative serum creatinine over baseline. Propensity analysis was used to match patients, who were then assessed both pre- and postmatch.

The overall incidence of AKI after surgery was 9.2% (230/2,504 patients). A breakdown by procedure showed that AKI occurred in 7.7% of isolated CABG patients, 12.2% of isolated valve patients, 9.5% of combined-procedure patients, and 9.5% of the proximal aorta surgery patients (Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;173:46-54).

As has been seen in previous studies, AKI was associated with patient-specific pre- and perioperative variables, including increased patient age, added comorbidities, longer cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times, higher rates of combined procedures, and the use of intra-aortic balloon pumps.

Unadjusted analysis of the total cohort showed AKI was significantly associated with contrast exposure within 1 day of surgery. However, in multivariable analysis, the time interval between catheterization and surgery as both a categorical and continuous variable was not an independent predictor of postoperative AKI for the total cohort. In subgroup analysis, only the combined valve and CABG group of patients showed an independent association of contrast exposure within 1 day before surgery and AKI in both the prematched (odds ratio, 2.69; P = .004) and the postmatched (OR, 3.68; P = .014) groups.

"Avoiding surgery within 1 day after contrast exposure should be recommended for patients undergoing valve surgery with concomitant CABG only. For other types of cardiac operations, delaying cardiac surgery after contrast exposure seems not to be justified," the researchers concluded.

Study limitations cited include its retrospective and single-institution nature and the statistical effect of different numbers of observations among the surgery groups. Patients affected with AKI also had higher rates of other postoperative complications, and AKI in some cases may have been the result of these rather than an independent event.

he study was supported by the Fondazione Cesare Bartorelli. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY

Major finding: Only combined surgery plus contrast within 1 day before surgery was significantly associated with AKI in the prematched (OR, 2.69) and postmatched (OR, 3.68) groups.

Data source: A single-institute, retrospective study of 2,504 cardiac surgery patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Fondazione Cesare Bartorelli. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Neither perioperative aspirin nor clonidine prevents MI

Neither perioperative aspirin therapy nor perioperative clonidine prevented death or MI in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were at risk for major vascular complications, according to data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Far from being protective, both preventive strategies exerted harmful effects: Aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding, and clonidine increased the risks of clinically important hypotension, bradycardia, and nonfatal MI, said Dr. P. J. Devereaux of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton (Ont.) General Hospital, and his associates in the POISE-2 (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) clinical trial.

The POISE-2 findings were simultaneously reported online in the New England Journal of Medicine 2014 March 31 [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401105] and [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401106]).

MI is the most common major vascular complication related to noncardiac surgery, and perioperative aspirin is thought to prevent it by inhibiting thrombus formation. At present, one-third of patients at risk for vascular complications receive perioperative aspirin even though the risks and benefits of this preventive strategy are uncertain.

Similarly, small trials have indicated that the antihypertensive agent clonidine, an alpha2 adrenergic agonist, reduces the risk of myocardial ischemia without inducing hemodynamic instability when given to at-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, which in turn may prevent MI and death. Clonidine has additional analgesic, anxiolytic, antishivering, and anti-inflammatory effects that may be helpful.

The POISE-2 trial was designed to determine whether either of these approaches was more effective than placebo at preventing the composite endpoint of MI or death within 30 days of surgery.

A total of 10,010 patients were enrolled at 135 hospitals in 23 countries, stratified by whether they were already taking daily aspirin prophylaxis, and randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to receive either perioperative aspirin (4,998 subjects) or placebo (5,012 subjects), and to receive either perioperative clonidine (5,009 subjects) or placebo (5,001 subjects). The mean age of these participants was 68.6 years, and 52.8% were men. Most were at risk because of their history of vascular disease; advanced age; need for dialysis; smoking status; or comorbid diabetes, heart failure, transient ischemic attack, or hypertension.

The types of surgery they underwent included general, orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, vascular, and thoracic procedures.

The primary outcome of death or MI occurred in 7% of the aspirin group and 7.1% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The risks of other adverse outcomes, including stroke, cardiac revascularization, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, and deep vein thrombosis, also were not significantly different between the two groups.

Median length of hospital stay and length of ICU and CCU stays also were not significantly different between patients who received aspirin and those who received placebo. However, aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding (4.6%), compared with placebo (3.8%), for a hazard ratio of 1.23. The most common sites of bleeding were the surgical site and the GI tract.

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, they were the same whether the patients were already taking daily prophylactic aspirin therapy.

Clonidine also did not prevent death or MI within 30 days, compared with placebo; the rates were 7.3% and 6.8%, respectively. The risks of other adverse outcomes also were not significantly different between the two groups, nor were lengths of hospital, ICU, or CCU stays. However, clonidine raised the risk of clinically important hypotension (47.6% vs. 37.1%), clinically important bradycardia (12% vs. 8.1%), and nonfatal cardiac arrest (0.3% vs. 0.1%).

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, clonidine was no more beneficial than was placebo in patients who underwent vascular surgery, a subgroup in whom previous, smaller studies found the drug to protect against both MI and mortality.

POISE-2 was not designed to determine why aspirin wasn’t effective at preventing perioperative MI, but Dr. Devereaux and his associates offered three possible explanations. First, MI was associated with major bleeding, and aspirin raises the risk of this complication. "It is possible that aspirin prevented some perioperative MI through thrombus inhibition [but] caused some MIs through bleeding and the subsequent mismatch between the supply of and the demand for myocardial oxygen, thus resulting in the overall neutral effect in our study," they said.

Second, the heart rate findings couldn’t statistically rule out a possible moderate beneficial effect of aspirin therapy. And third, it is possible that coronary-artery thrombus isn’t the dominant mechanism of perioperative MI, and aspirin’s antithrombotic effect didn’t address this unknown dominant mechanism.

Similarly, it is not known why clonidine failed to be protective, but the investigators offered two possible reasons. First, the drug induced hypotension, which raises the risk of perioperative MI. And second, it also induced bradycardia, which may be a proxy for an overall adverse effect on heart rate control; this also can increase the risk of perioperative MI, they said.

The POISE-2 trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy. Bayer Pharma provided the aspirin used in the study, and Boehringer Ingelheim provided the clonidine and some funding. Dr. Devereaux reported ties to Abbott, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Covidien, Roche, and Stryker and; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

Myriad, and sometimes opposing, mechanisms contribute to perioperative MI, including excess bleeding, dramatic fluid shifts, unrelenting tachycardia, myocardial stress with fixed coronary obstruction, profound hypo- or hypertension, coronary plaque rupture, and coronary spasm, said Dr. Prashant Vaishnava and Dr. Kim A. Eagle.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that a medical therapy aimed at one of these mechanisms may actually augment a different mechanism, and end up raising MI risk. "Aspirin may reduce coronary thrombosis at the expense of excess bleeding; clonidine may reduce hypertensive swings only to be countered by clinically important hypotension," they noted.

On balance, the POISE-2 results provide cogent evidence against the use of either perioperative aspirin or clonidine.

Dr. Vaishnava and Dr. Eagle are at the Samuel and Jean A. Frankel Cardiovascular Center at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. They reported no potential conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the POISE-2 trial reports (New Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 31 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1402976]).

Myriad, and sometimes opposing, mechanisms contribute to perioperative MI, including excess bleeding, dramatic fluid shifts, unrelenting tachycardia, myocardial stress with fixed coronary obstruction, profound hypo- or hypertension, coronary plaque rupture, and coronary spasm, said Dr. Prashant Vaishnava and Dr. Kim A. Eagle.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that a medical therapy aimed at one of these mechanisms may actually augment a different mechanism, and end up raising MI risk. "Aspirin may reduce coronary thrombosis at the expense of excess bleeding; clonidine may reduce hypertensive swings only to be countered by clinically important hypotension," they noted.

On balance, the POISE-2 results provide cogent evidence against the use of either perioperative aspirin or clonidine.

Dr. Vaishnava and Dr. Eagle are at the Samuel and Jean A. Frankel Cardiovascular Center at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. They reported no potential conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the POISE-2 trial reports (New Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 31 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1402976]).

Myriad, and sometimes opposing, mechanisms contribute to perioperative MI, including excess bleeding, dramatic fluid shifts, unrelenting tachycardia, myocardial stress with fixed coronary obstruction, profound hypo- or hypertension, coronary plaque rupture, and coronary spasm, said Dr. Prashant Vaishnava and Dr. Kim A. Eagle.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that a medical therapy aimed at one of these mechanisms may actually augment a different mechanism, and end up raising MI risk. "Aspirin may reduce coronary thrombosis at the expense of excess bleeding; clonidine may reduce hypertensive swings only to be countered by clinically important hypotension," they noted.

On balance, the POISE-2 results provide cogent evidence against the use of either perioperative aspirin or clonidine.

Dr. Vaishnava and Dr. Eagle are at the Samuel and Jean A. Frankel Cardiovascular Center at the University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor. They reported no potential conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the POISE-2 trial reports (New Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 31 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1402976]).

Neither perioperative aspirin therapy nor perioperative clonidine prevented death or MI in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were at risk for major vascular complications, according to data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Far from being protective, both preventive strategies exerted harmful effects: Aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding, and clonidine increased the risks of clinically important hypotension, bradycardia, and nonfatal MI, said Dr. P. J. Devereaux of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton (Ont.) General Hospital, and his associates in the POISE-2 (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) clinical trial.

The POISE-2 findings were simultaneously reported online in the New England Journal of Medicine 2014 March 31 [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401105] and [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401106]).

MI is the most common major vascular complication related to noncardiac surgery, and perioperative aspirin is thought to prevent it by inhibiting thrombus formation. At present, one-third of patients at risk for vascular complications receive perioperative aspirin even though the risks and benefits of this preventive strategy are uncertain.

Similarly, small trials have indicated that the antihypertensive agent clonidine, an alpha2 adrenergic agonist, reduces the risk of myocardial ischemia without inducing hemodynamic instability when given to at-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, which in turn may prevent MI and death. Clonidine has additional analgesic, anxiolytic, antishivering, and anti-inflammatory effects that may be helpful.

The POISE-2 trial was designed to determine whether either of these approaches was more effective than placebo at preventing the composite endpoint of MI or death within 30 days of surgery.

A total of 10,010 patients were enrolled at 135 hospitals in 23 countries, stratified by whether they were already taking daily aspirin prophylaxis, and randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to receive either perioperative aspirin (4,998 subjects) or placebo (5,012 subjects), and to receive either perioperative clonidine (5,009 subjects) or placebo (5,001 subjects). The mean age of these participants was 68.6 years, and 52.8% were men. Most were at risk because of their history of vascular disease; advanced age; need for dialysis; smoking status; or comorbid diabetes, heart failure, transient ischemic attack, or hypertension.

The types of surgery they underwent included general, orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, vascular, and thoracic procedures.

The primary outcome of death or MI occurred in 7% of the aspirin group and 7.1% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The risks of other adverse outcomes, including stroke, cardiac revascularization, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, and deep vein thrombosis, also were not significantly different between the two groups.

Median length of hospital stay and length of ICU and CCU stays also were not significantly different between patients who received aspirin and those who received placebo. However, aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding (4.6%), compared with placebo (3.8%), for a hazard ratio of 1.23. The most common sites of bleeding were the surgical site and the GI tract.

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, they were the same whether the patients were already taking daily prophylactic aspirin therapy.

Clonidine also did not prevent death or MI within 30 days, compared with placebo; the rates were 7.3% and 6.8%, respectively. The risks of other adverse outcomes also were not significantly different between the two groups, nor were lengths of hospital, ICU, or CCU stays. However, clonidine raised the risk of clinically important hypotension (47.6% vs. 37.1%), clinically important bradycardia (12% vs. 8.1%), and nonfatal cardiac arrest (0.3% vs. 0.1%).

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, clonidine was no more beneficial than was placebo in patients who underwent vascular surgery, a subgroup in whom previous, smaller studies found the drug to protect against both MI and mortality.

POISE-2 was not designed to determine why aspirin wasn’t effective at preventing perioperative MI, but Dr. Devereaux and his associates offered three possible explanations. First, MI was associated with major bleeding, and aspirin raises the risk of this complication. "It is possible that aspirin prevented some perioperative MI through thrombus inhibition [but] caused some MIs through bleeding and the subsequent mismatch between the supply of and the demand for myocardial oxygen, thus resulting in the overall neutral effect in our study," they said.

Second, the heart rate findings couldn’t statistically rule out a possible moderate beneficial effect of aspirin therapy. And third, it is possible that coronary-artery thrombus isn’t the dominant mechanism of perioperative MI, and aspirin’s antithrombotic effect didn’t address this unknown dominant mechanism.

Similarly, it is not known why clonidine failed to be protective, but the investigators offered two possible reasons. First, the drug induced hypotension, which raises the risk of perioperative MI. And second, it also induced bradycardia, which may be a proxy for an overall adverse effect on heart rate control; this also can increase the risk of perioperative MI, they said.

The POISE-2 trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy. Bayer Pharma provided the aspirin used in the study, and Boehringer Ingelheim provided the clonidine and some funding. Dr. Devereaux reported ties to Abbott, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Covidien, Roche, and Stryker and; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

Neither perioperative aspirin therapy nor perioperative clonidine prevented death or MI in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were at risk for major vascular complications, according to data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Far from being protective, both preventive strategies exerted harmful effects: Aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding, and clonidine increased the risks of clinically important hypotension, bradycardia, and nonfatal MI, said Dr. P. J. Devereaux of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton (Ont.) General Hospital, and his associates in the POISE-2 (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) clinical trial.

The POISE-2 findings were simultaneously reported online in the New England Journal of Medicine 2014 March 31 [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401105] and [doi:10/1056.

NEJMoa1401106]).

MI is the most common major vascular complication related to noncardiac surgery, and perioperative aspirin is thought to prevent it by inhibiting thrombus formation. At present, one-third of patients at risk for vascular complications receive perioperative aspirin even though the risks and benefits of this preventive strategy are uncertain.

Similarly, small trials have indicated that the antihypertensive agent clonidine, an alpha2 adrenergic agonist, reduces the risk of myocardial ischemia without inducing hemodynamic instability when given to at-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, which in turn may prevent MI and death. Clonidine has additional analgesic, anxiolytic, antishivering, and anti-inflammatory effects that may be helpful.

The POISE-2 trial was designed to determine whether either of these approaches was more effective than placebo at preventing the composite endpoint of MI or death within 30 days of surgery.

A total of 10,010 patients were enrolled at 135 hospitals in 23 countries, stratified by whether they were already taking daily aspirin prophylaxis, and randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to receive either perioperative aspirin (4,998 subjects) or placebo (5,012 subjects), and to receive either perioperative clonidine (5,009 subjects) or placebo (5,001 subjects). The mean age of these participants was 68.6 years, and 52.8% were men. Most were at risk because of their history of vascular disease; advanced age; need for dialysis; smoking status; or comorbid diabetes, heart failure, transient ischemic attack, or hypertension.

The types of surgery they underwent included general, orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, vascular, and thoracic procedures.

The primary outcome of death or MI occurred in 7% of the aspirin group and 7.1% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference. The risks of other adverse outcomes, including stroke, cardiac revascularization, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, and deep vein thrombosis, also were not significantly different between the two groups.

Median length of hospital stay and length of ICU and CCU stays also were not significantly different between patients who received aspirin and those who received placebo. However, aspirin raised the risk of major bleeding (4.6%), compared with placebo (3.8%), for a hazard ratio of 1.23. The most common sites of bleeding were the surgical site and the GI tract.

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, they were the same whether the patients were already taking daily prophylactic aspirin therapy.

Clonidine also did not prevent death or MI within 30 days, compared with placebo; the rates were 7.3% and 6.8%, respectively. The risks of other adverse outcomes also were not significantly different between the two groups, nor were lengths of hospital, ICU, or CCU stays. However, clonidine raised the risk of clinically important hypotension (47.6% vs. 37.1%), clinically important bradycardia (12% vs. 8.1%), and nonfatal cardiac arrest (0.3% vs. 0.1%).

These effects were consistent across all subgroups of patients. In particular, clonidine was no more beneficial than was placebo in patients who underwent vascular surgery, a subgroup in whom previous, smaller studies found the drug to protect against both MI and mortality.

POISE-2 was not designed to determine why aspirin wasn’t effective at preventing perioperative MI, but Dr. Devereaux and his associates offered three possible explanations. First, MI was associated with major bleeding, and aspirin raises the risk of this complication. "It is possible that aspirin prevented some perioperative MI through thrombus inhibition [but] caused some MIs through bleeding and the subsequent mismatch between the supply of and the demand for myocardial oxygen, thus resulting in the overall neutral effect in our study," they said.

Second, the heart rate findings couldn’t statistically rule out a possible moderate beneficial effect of aspirin therapy. And third, it is possible that coronary-artery thrombus isn’t the dominant mechanism of perioperative MI, and aspirin’s antithrombotic effect didn’t address this unknown dominant mechanism.

Similarly, it is not known why clonidine failed to be protective, but the investigators offered two possible reasons. First, the drug induced hypotension, which raises the risk of perioperative MI. And second, it also induced bradycardia, which may be a proxy for an overall adverse effect on heart rate control; this also can increase the risk of perioperative MI, they said.

The POISE-2 trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy. Bayer Pharma provided the aspirin used in the study, and Boehringer Ingelheim provided the clonidine and some funding. Dr. Devereaux reported ties to Abbott, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Covidien, Roche, and Stryker and; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

FROM ACC 14

Major finding: The primary outcome of death or MI occurred in 7% of the aspirin group and 7.1% of the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference; it also occurred in 7.3% of the clonidine group and 6.8% of the placebo group, also a nonsignificant difference.

Data source: A randomized, blinded clinical trial evaluating perioperative aspirin vs. placebo and perioperative clonidine vs. placebo in 10,010 patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were at risk for major vascular complications.

Disclosures: The POISE-2 trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy. Bayer Pharma provided the aspirin used in the study and Boehringer Ingelheim provided the clonidine and some funding. Dr. Devereaux reported ties to Abbott, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Covidien, Roche, and Stryker and; some of his associates reported ties to several industry sources.

VIDEO: Study highlights progress, challenges in nosocomial infections

One in 25 hospitalized patients on any given day has an infection acquired from health care, and as many as 1 in 9 of those will die.

At a press briefing, Dr. Michael Bell discussed new data from a prevalence study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where he is the deputy director for the division of health care quality promotion. Hospitals, doctors, and patients all have a role to play in decreasing the risks of these infections, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

This article was updated 3/28/2014.

One in 25 hospitalized patients on any given day has an infection acquired from health care, and as many as 1 in 9 of those will die.

At a press briefing, Dr. Michael Bell discussed new data from a prevalence study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where he is the deputy director for the division of health care quality promotion. Hospitals, doctors, and patients all have a role to play in decreasing the risks of these infections, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

This article was updated 3/28/2014.

One in 25 hospitalized patients on any given day has an infection acquired from health care, and as many as 1 in 9 of those will die.

At a press briefing, Dr. Michael Bell discussed new data from a prevalence study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where he is the deputy director for the division of health care quality promotion. Hospitals, doctors, and patients all have a role to play in decreasing the risks of these infections, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

This article was updated 3/28/2014.

FROM THE CDC

Optimal management of patients with chronic kidney disease