User login

Clinical Guidelines Hub only

Guideline recommends combination therapy for smoking cessation in cancer patients

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

Statins for all eligible under new guidelines could save lives

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

AT AHA EPI/LIFESTYLE 2015MEETING

Key clinical point: New statin guidelines, if followed, could save lives but increase cases of myopathy and diabetes.

Major finding: Up to 12.6% of current deaths from CVD could be prevented if all guideline-eligible Americans took statins; saving of these lives would come at the cost of excess cases of diabetes and myopathy.

Data source: Analysis of U.S. census data and data from the NHANES study, together with meta-analysis of RCTs, used to model outcomes for 100% guideline-eligible statin use.

Disclosures: No authors reported financial disclosures.

Latest valvular disease guidelines bring big changes

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

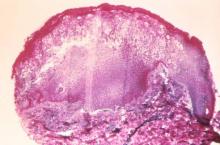

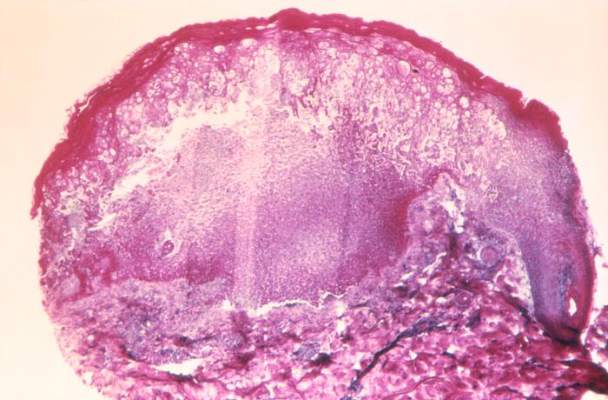

ACP guidelines for preventing, treating pressure ulcers

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

Postexposure smallpox vaccination not recommended for immunodeficient patients

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.

Find the full guideline in the MMWR (February 20, 2015 / 64(RR02);1-26).

VIDEO: Is JNC 8’s hypertension treatment threshold too high?

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Last year, the Eighth Joint National Committee revised upward its classification of hypertension in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, recommending treatment when systolic pressure hits at least 150 mm Hg, or diastolic pressure reaches at least 90 mm Hg.

But raising the treatment cut point by 10 mm Hg from the earlier JNC 7 recommendations is a bad idea, Dr. Ralph L. Sacco warned at the International Stroke Conference – very bad, in fact.

And Dr. Sacco, the Olemberg Family Chair in Neurological Disorders at the University of Miami, said he has the data to prove it.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Sacco outlined the findings from a new study exploring the stroke risks of patients who might find themselves now deemed normotensive under the JNC 8 hypertension guidelines.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Last year, the Eighth Joint National Committee revised upward its classification of hypertension in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, recommending treatment when systolic pressure hits at least 150 mm Hg, or diastolic pressure reaches at least 90 mm Hg.

But raising the treatment cut point by 10 mm Hg from the earlier JNC 7 recommendations is a bad idea, Dr. Ralph L. Sacco warned at the International Stroke Conference – very bad, in fact.

And Dr. Sacco, the Olemberg Family Chair in Neurological Disorders at the University of Miami, said he has the data to prove it.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Sacco outlined the findings from a new study exploring the stroke risks of patients who might find themselves now deemed normotensive under the JNC 8 hypertension guidelines.

On Twitter @alz_gal

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Last year, the Eighth Joint National Committee revised upward its classification of hypertension in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, recommending treatment when systolic pressure hits at least 150 mm Hg, or diastolic pressure reaches at least 90 mm Hg.

But raising the treatment cut point by 10 mm Hg from the earlier JNC 7 recommendations is a bad idea, Dr. Ralph L. Sacco warned at the International Stroke Conference – very bad, in fact.

And Dr. Sacco, the Olemberg Family Chair in Neurological Disorders at the University of Miami, said he has the data to prove it.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Sacco outlined the findings from a new study exploring the stroke risks of patients who might find themselves now deemed normotensive under the JNC 8 hypertension guidelines.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

ASCO endorses ACS guidelines for prostate cancer survivor care

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has endorsed the American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines, a 39-point list with recommendations on continuing care for prostate care survivors, but with a number of qualifying statements and modifications.

The guidelines, developed by a workgroup of 16 multidisciplinary experts specializing in the care of prostate cancer patients and the long-term effects of their treatments, are intended as points of reference for primary care providers, medical oncologists, urologists, and other health care providers.

Areas covered in the guidelines include health promotion, surveillance for recurrence, screening and early detection of second primary cancers, assessment and management of physical and psychosocial long-term and late effects, and care coordination and practice implications.Read the full list of recommendations here: (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has endorsed the American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines, a 39-point list with recommendations on continuing care for prostate care survivors, but with a number of qualifying statements and modifications.

The guidelines, developed by a workgroup of 16 multidisciplinary experts specializing in the care of prostate cancer patients and the long-term effects of their treatments, are intended as points of reference for primary care providers, medical oncologists, urologists, and other health care providers.

Areas covered in the guidelines include health promotion, surveillance for recurrence, screening and early detection of second primary cancers, assessment and management of physical and psychosocial long-term and late effects, and care coordination and practice implications.Read the full list of recommendations here: (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has endorsed the American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines, a 39-point list with recommendations on continuing care for prostate care survivors, but with a number of qualifying statements and modifications.

The guidelines, developed by a workgroup of 16 multidisciplinary experts specializing in the care of prostate cancer patients and the long-term effects of their treatments, are intended as points of reference for primary care providers, medical oncologists, urologists, and other health care providers.

Areas covered in the guidelines include health promotion, surveillance for recurrence, screening and early detection of second primary cancers, assessment and management of physical and psychosocial long-term and late effects, and care coordination and practice implications.Read the full list of recommendations here: (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557).

Guideline clarifies first-line treatment for allergic rhinitis

First-line treatment for allergic rhinitis should include intranasal steroids, as well as less-sedating second-generation oral antihistamines for patients whose primary complaints are sneezing and itching, according to a new clinical practice guideline published online Feb. 2 in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

In contrast, sinonasal imaging should not be routine when patients first present with symptoms consistent with allergic rhinitis, and oral leukotriene receptor antagonists are not recommended as first-line therapy, said Dr. Michael D. Seidman of Henry Ford West Bloomfield (Mich.) Hospital and chair of the guideline working group, and his associates.

Dr. Seidman and a panel of 20 experts in otolaryngology, allergy and immunology, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, sleep medicine, advanced practice nursing, complementary and alternative medicine, and consumer advocacy developed the new practice guideline to enable clinicians in all settings to improve patient care and reduce harmful or unnecessary variations in care for allergic rhinitis.

“The guideline is intended to focus on a limited number of quality improvement opportunities deemed most important by the working group and is not intended to be a comprehensive reference for diagnosing and managing allergic rhinitis,” the authors noted.

During the course of 1 year, the working group reviewed 1,605 randomized, controlled trials, 31 existing clinical practice guidelines, and 390 systematic reviews of the literature regarding allergic rhinitis in adults and children older than age 2 years. They then compiled 14 key recommendations that underwent extensive peer review, which have been published online and as a supplement to the February issue (Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:S1-S43).

In addition to the recommendations noted above, the guideline advises:

* Clinicians should diagnose allergic rhinitis when patients present with a history and physical exam consistent with the disorder (including clear rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, pale discoloration of the nasal mucosa, and red, watery eyes) plus symptoms of nasal congestion, runny nose, itchy nose, or sneezing.

* Clinicians should perform and interpret (or refer patients for) specific IgE allergy testing for allergic rhinitis that doesn’t respond to empiric treatment, or when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when identifying the specific causative allergen would allow targeted therapy.

* Clinicians should assess diagnosed patients for associated conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, sleep-disordered breathing, conjunctivitis, rhinosinusitis, and otitis media, and should document that in the medical record.

* Clinicians should offer (or refer patients for) sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy when allergic rhinitis doesn’t respond adequately to pharmacologic therapy.

* Clinicians may advise avoidance of known allergens or controlling the patient’s environment by such measures as removing pets, using air filtration systems, using dust-mite–reducing covers for bedding, and using acaricides.

* Clinicians may offer intranasal antihistamines for patients with seasonal, perennial or episodic allergic rhinitis.*

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patients for) reduction of the inferior turbinates for patients who have nasal airway obstruction or enlarged turbinates.

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patient for) acupuncture if they are interested in nonpharmacologic therapy.

*Clinicians may offer combination pharmacologic therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis who have inadequate response to pharmacologic monotherapy.

The working group offered no recommendations concerning herbal therapy for allergic rhinitis, because of the limited literature on those substances and concern about their safety.

The full text of the guideline and its supporting data are available free of charge at www.entnet.org. In addition, an algorithm of the guideline’s action statements and a table of common allergic rhinitis clinical scenarios are available as quick reference guides for clinicians.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation funded the guideline. Dr. Seidman reported being medical director of the Scientific Advisory Board of Visalus, founder of the Body Language Vitamin, and holder of six patents related to dietary supplements, aircraft, and middle ear and brain implants. His associates reported ties to Acclarent/Johnson/Johnson, FirstLine Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, Intersect, MEDA, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, TEVA, Transit of Venus, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and WellPoint.

*Correction, 2/18/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the guideline for the use of intranasal antihistamines.

First-line treatment for allergic rhinitis should include intranasal steroids, as well as less-sedating second-generation oral antihistamines for patients whose primary complaints are sneezing and itching, according to a new clinical practice guideline published online Feb. 2 in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

In contrast, sinonasal imaging should not be routine when patients first present with symptoms consistent with allergic rhinitis, and oral leukotriene receptor antagonists are not recommended as first-line therapy, said Dr. Michael D. Seidman of Henry Ford West Bloomfield (Mich.) Hospital and chair of the guideline working group, and his associates.

Dr. Seidman and a panel of 20 experts in otolaryngology, allergy and immunology, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, sleep medicine, advanced practice nursing, complementary and alternative medicine, and consumer advocacy developed the new practice guideline to enable clinicians in all settings to improve patient care and reduce harmful or unnecessary variations in care for allergic rhinitis.

“The guideline is intended to focus on a limited number of quality improvement opportunities deemed most important by the working group and is not intended to be a comprehensive reference for diagnosing and managing allergic rhinitis,” the authors noted.

During the course of 1 year, the working group reviewed 1,605 randomized, controlled trials, 31 existing clinical practice guidelines, and 390 systematic reviews of the literature regarding allergic rhinitis in adults and children older than age 2 years. They then compiled 14 key recommendations that underwent extensive peer review, which have been published online and as a supplement to the February issue (Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:S1-S43).

In addition to the recommendations noted above, the guideline advises:

* Clinicians should diagnose allergic rhinitis when patients present with a history and physical exam consistent with the disorder (including clear rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, pale discoloration of the nasal mucosa, and red, watery eyes) plus symptoms of nasal congestion, runny nose, itchy nose, or sneezing.

* Clinicians should perform and interpret (or refer patients for) specific IgE allergy testing for allergic rhinitis that doesn’t respond to empiric treatment, or when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when identifying the specific causative allergen would allow targeted therapy.

* Clinicians should assess diagnosed patients for associated conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, sleep-disordered breathing, conjunctivitis, rhinosinusitis, and otitis media, and should document that in the medical record.

* Clinicians should offer (or refer patients for) sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy when allergic rhinitis doesn’t respond adequately to pharmacologic therapy.

* Clinicians may advise avoidance of known allergens or controlling the patient’s environment by such measures as removing pets, using air filtration systems, using dust-mite–reducing covers for bedding, and using acaricides.

* Clinicians may offer intranasal antihistamines for patients with seasonal, perennial or episodic allergic rhinitis.*

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patients for) reduction of the inferior turbinates for patients who have nasal airway obstruction or enlarged turbinates.

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patient for) acupuncture if they are interested in nonpharmacologic therapy.

*Clinicians may offer combination pharmacologic therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis who have inadequate response to pharmacologic monotherapy.

The working group offered no recommendations concerning herbal therapy for allergic rhinitis, because of the limited literature on those substances and concern about their safety.

The full text of the guideline and its supporting data are available free of charge at www.entnet.org. In addition, an algorithm of the guideline’s action statements and a table of common allergic rhinitis clinical scenarios are available as quick reference guides for clinicians.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation funded the guideline. Dr. Seidman reported being medical director of the Scientific Advisory Board of Visalus, founder of the Body Language Vitamin, and holder of six patents related to dietary supplements, aircraft, and middle ear and brain implants. His associates reported ties to Acclarent/Johnson/Johnson, FirstLine Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, Intersect, MEDA, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, TEVA, Transit of Venus, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and WellPoint.

*Correction, 2/18/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the guideline for the use of intranasal antihistamines.

First-line treatment for allergic rhinitis should include intranasal steroids, as well as less-sedating second-generation oral antihistamines for patients whose primary complaints are sneezing and itching, according to a new clinical practice guideline published online Feb. 2 in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

In contrast, sinonasal imaging should not be routine when patients first present with symptoms consistent with allergic rhinitis, and oral leukotriene receptor antagonists are not recommended as first-line therapy, said Dr. Michael D. Seidman of Henry Ford West Bloomfield (Mich.) Hospital and chair of the guideline working group, and his associates.

Dr. Seidman and a panel of 20 experts in otolaryngology, allergy and immunology, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, sleep medicine, advanced practice nursing, complementary and alternative medicine, and consumer advocacy developed the new practice guideline to enable clinicians in all settings to improve patient care and reduce harmful or unnecessary variations in care for allergic rhinitis.

“The guideline is intended to focus on a limited number of quality improvement opportunities deemed most important by the working group and is not intended to be a comprehensive reference for diagnosing and managing allergic rhinitis,” the authors noted.

During the course of 1 year, the working group reviewed 1,605 randomized, controlled trials, 31 existing clinical practice guidelines, and 390 systematic reviews of the literature regarding allergic rhinitis in adults and children older than age 2 years. They then compiled 14 key recommendations that underwent extensive peer review, which have been published online and as a supplement to the February issue (Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:S1-S43).

In addition to the recommendations noted above, the guideline advises:

* Clinicians should diagnose allergic rhinitis when patients present with a history and physical exam consistent with the disorder (including clear rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, pale discoloration of the nasal mucosa, and red, watery eyes) plus symptoms of nasal congestion, runny nose, itchy nose, or sneezing.

* Clinicians should perform and interpret (or refer patients for) specific IgE allergy testing for allergic rhinitis that doesn’t respond to empiric treatment, or when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when identifying the specific causative allergen would allow targeted therapy.

* Clinicians should assess diagnosed patients for associated conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, sleep-disordered breathing, conjunctivitis, rhinosinusitis, and otitis media, and should document that in the medical record.

* Clinicians should offer (or refer patients for) sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy when allergic rhinitis doesn’t respond adequately to pharmacologic therapy.

* Clinicians may advise avoidance of known allergens or controlling the patient’s environment by such measures as removing pets, using air filtration systems, using dust-mite–reducing covers for bedding, and using acaricides.

* Clinicians may offer intranasal antihistamines for patients with seasonal, perennial or episodic allergic rhinitis.*

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patients for) reduction of the inferior turbinates for patients who have nasal airway obstruction or enlarged turbinates.

* Clinicians may offer (or refer patient for) acupuncture if they are interested in nonpharmacologic therapy.

*Clinicians may offer combination pharmacologic therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis who have inadequate response to pharmacologic monotherapy.

The working group offered no recommendations concerning herbal therapy for allergic rhinitis, because of the limited literature on those substances and concern about their safety.

The full text of the guideline and its supporting data are available free of charge at www.entnet.org. In addition, an algorithm of the guideline’s action statements and a table of common allergic rhinitis clinical scenarios are available as quick reference guides for clinicians.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation funded the guideline. Dr. Seidman reported being medical director of the Scientific Advisory Board of Visalus, founder of the Body Language Vitamin, and holder of six patents related to dietary supplements, aircraft, and middle ear and brain implants. His associates reported ties to Acclarent/Johnson/Johnson, FirstLine Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, Intersect, MEDA, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, TEVA, Transit of Venus, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and WellPoint.

*Correction, 2/18/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the guideline for the use of intranasal antihistamines.

FROM OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD AND NECK SURGERY

Key clinical point: First-line treatment for allergic rhinitis should include intranasal steroids and second-generation oral antihistamines, and should not include leukotriene receptor antagonists or sinonasal imaging studies.

Major finding: A panel of 20 experts took 1 year to review the literature and develop action items focusing on a limited number of quality improvement opportunities they deemed most important to improve patient care.

Data source: A review of 1,605 randomized, controlled trials, 31 sets of practice guidelines, and 390 systematic reviews regarding allergic rhinitis, and a compilation of 14 recommendations for managing the disorder.

Disclosures: The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation funded the guideline. Dr. Seidman reported being medical director of the Scientific Advisory Board of Visalus, founder of the Body Language Vitamin, and holder of six patents related to dietary supplements, aircraft, and middle ear and brain implants. His associates reported ties to Acclarent/Johnson/Johnson, FirstLine Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, Intersect, MEDA, Medtronic, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, TEVA, Transit of Venus, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and WellPoint.

Broad application of JNC-8 would save lives, reduce costs

Antihypertensive therapy would prevent about 56,000 cardiovascular events annually and 13,000 deaths from strokes, myocardial infarctions, and other causes if it were used by all U.S. adults who qualify for treatment under 2014 Joint National Committee hypertension guidelines, according to computer modeling published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the new Joint Committee guidelines are a bit less stringent than the committee’s prior 2003 advice, blood pressure remains inadequately controlled in 44% of the 64 million U.S. adults with hypertension, according to the investigators, led by Dr. Andrew Moran of Columbia University Medical Center, New York (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:447-55).

The team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Framingham Heart Study, and other sources to estimate costs and benefits of expanding treatment to all U.S. adults aged 35-74 years who meet the 2014 benchmarks. They then calculated cost-effectiveness of expanding use in various subpopulations, using $50,000/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, or less, as their cut-off.

Overall, the investigators found that fuller implementation of the Joint Committee goals would pay for itself in reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The results were driven primarily by secondary prevention in patients with cardiovascular disease and primary prevention in patients with stage 2 hypertension, meaning systolic BP of 160 mm Hg or higher or diastolic BP of 100 mm Hg or higher.

“There is an enormous potential for improving population health by expanding treatment and improving control. Our findings clearly show that it would be worthwhile to significantly increase spending on office visits, home blood pressure monitoring, and interventions to improve treatment adherence. In fact, we could double treatment and monitoring spending for some patients – namely those with severe hypertension – and still break even,” Dr. Moran said in a statement announcing the results.

Treatment of patients with existing cardiovascular disease or stage 2 hypertension would save lives and costs in all men 35-74 years old and in women aged 45-74 years. The treatment of more modest hypertension – systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of 90-99 mm Hg – was cost effective for all men and for women also between the ages of 45 and 74 years, but treating women 35-44 years old with moderate hypertension and diabetes or kidney disease had intermediate cost-effectiveness ($125,000 per QALY), and low cost-effectiveness ($181,000 per QALY) if those comorbidities were not present.

“Some people will be alarmed about our conclusion that it may not be cost effective to treat hypertension in young adults, especially young women. It’s worth noting that our analysis didn’t capture the cumulative, lifetime effects of hypertension. It may well turn out to be cost effective to treat this group if we look at data on costs and benefits over several decades,” Dr. Moran said.

The team assumed a medication adherence rate of 75%. The costs of treatment included medications, monitoring, and drug side effects.

They did not analyze the effect of diet and lifestyle interventions for lowering blood pressure, or compare the cost-effectiveness of specific antihypertensive medication classes or combinations.

The work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, among others. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Antihypertensive therapy would prevent about 56,000 cardiovascular events annually and 13,000 deaths from strokes, myocardial infarctions, and other causes if it were used by all U.S. adults who qualify for treatment under 2014 Joint National Committee hypertension guidelines, according to computer modeling published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the new Joint Committee guidelines are a bit less stringent than the committee’s prior 2003 advice, blood pressure remains inadequately controlled in 44% of the 64 million U.S. adults with hypertension, according to the investigators, led by Dr. Andrew Moran of Columbia University Medical Center, New York (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:447-55).