User login

Did You Know? Psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease

Psoriasis registry data provide evidence that adalimumab reduces mortality

MADRID – Psoriasis patients on adalimumab for up to 10 years in the prospective, observational, international, real-world ESPRIT registry had a sharply reduced likelihood of all-cause mortality, compared with the age- and sex-matched general population in participating countries, Diamant T. Thaci, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“If someone tells you that you as a dermatologist can save patient lives by controlling psoriasis, you may not believe it. But look at this standardized mortality ratio data,” said Dr. Thaci, professor of dermatology and head of the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine at the University of Luebeck (Germany).

Indeed, the standardized in routine clinical practice, was 58% lower than expected, based upon published mortality rate data for the general population in the United States, Canada, and the 10 participating European countries. A total of 144 deaths were predicted in the matched general population, yet only 60 deaths occurred in adalimumab-treated registry participants.

This finding is all the more remarkable because ESPRIT participants had high rates of cardiovascular risk factors, as well as a substantial burden of comorbid conditions, as is typical for patients with chronic moderate to severe psoriasis encountered in real-world clinical practice. It’s a different population than enrollees in the long-term, open-label extensions of phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trials of biologics in psoriasis, which at the outset typically excluded patients with baseline substantial comorbidities, he noted.

Moreover, the incidence rates of serious infections, malignancies, and cardiovascular events in ESPRIT participants remained stable over time and well within the range of published rates in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy.

“All of this underscores the importance of good control of psoriasis,” Dr. Thaci commented.

The ESPRIT registry began enrolling patients and evaluating them every 6 months in 2008, when the vast majority of dermatologists in clinical practice relied upon Physician Global Assessment (PGA) to evaluate treatment efficacy. For this reason, the PGA, rather than the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, was the main efficacy measure utilized in the registry. The rate of PGA “clear” or “almost clear” was steady over time at 57% at 1 year, 62.1% at 5 years, and 61.5% at 10 years. It should be noted that this was reported in an “as-observed” analysis, which introduces bias favoring a rosier picture of efficacy since by 10 years slightly under half of patients remained on the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

However, the primary focus of this ESPRIT analysis was safety, not efficacy. The rate of serious infections was 1.0 event per 100 person-years on adalimumab, compared with published rates of 0.3-2.1 events/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on a biologic. Malignancies occurred at a rate of 1.3 events/100 person-years in ESPRIT, compared with published rates of 0.5-2.0/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy. Acute MI occurred at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 person-years in ESPRIT, stroke at 0.2 events/100 person-years, and heart failure at less than 0.1 event/100 person-years, versus a collective rate of 0.6-1.5 events/100 person-years in the comparator population.

Another view of the data is that, at 10 years, 99.4% of ESPRIT participants had not experienced an acute MI, 95.9% hadn’t had a malignancy, and 96.1% remained free of serious infection while on adalimumab, Dr. Thaci continued.

Injection-site reactions, a significant source of concern when adalimumab first reached the marketplace, occurred at a rate of 0.2 events/100 person-years over the course of 10 years. Oral candidiasis, active tuberculosis, demyelinating disorders, and lupus-like reactions were rare, each occurring at an incidence of less than 0.1 event/100 person-years.

Dr. Thaci’s 10-year update from the ongoing registry follows an earlier report of the 5-year results (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73[3]:410-9.e6).

The ESPRIT registry is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Thaci reported serving as a consultant to and/or receiving research grants from that pharmaceutical company and nearly two dozen others.

MADRID – Psoriasis patients on adalimumab for up to 10 years in the prospective, observational, international, real-world ESPRIT registry had a sharply reduced likelihood of all-cause mortality, compared with the age- and sex-matched general population in participating countries, Diamant T. Thaci, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“If someone tells you that you as a dermatologist can save patient lives by controlling psoriasis, you may not believe it. But look at this standardized mortality ratio data,” said Dr. Thaci, professor of dermatology and head of the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine at the University of Luebeck (Germany).

Indeed, the standardized in routine clinical practice, was 58% lower than expected, based upon published mortality rate data for the general population in the United States, Canada, and the 10 participating European countries. A total of 144 deaths were predicted in the matched general population, yet only 60 deaths occurred in adalimumab-treated registry participants.

This finding is all the more remarkable because ESPRIT participants had high rates of cardiovascular risk factors, as well as a substantial burden of comorbid conditions, as is typical for patients with chronic moderate to severe psoriasis encountered in real-world clinical practice. It’s a different population than enrollees in the long-term, open-label extensions of phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trials of biologics in psoriasis, which at the outset typically excluded patients with baseline substantial comorbidities, he noted.

Moreover, the incidence rates of serious infections, malignancies, and cardiovascular events in ESPRIT participants remained stable over time and well within the range of published rates in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy.

“All of this underscores the importance of good control of psoriasis,” Dr. Thaci commented.

The ESPRIT registry began enrolling patients and evaluating them every 6 months in 2008, when the vast majority of dermatologists in clinical practice relied upon Physician Global Assessment (PGA) to evaluate treatment efficacy. For this reason, the PGA, rather than the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, was the main efficacy measure utilized in the registry. The rate of PGA “clear” or “almost clear” was steady over time at 57% at 1 year, 62.1% at 5 years, and 61.5% at 10 years. It should be noted that this was reported in an “as-observed” analysis, which introduces bias favoring a rosier picture of efficacy since by 10 years slightly under half of patients remained on the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

However, the primary focus of this ESPRIT analysis was safety, not efficacy. The rate of serious infections was 1.0 event per 100 person-years on adalimumab, compared with published rates of 0.3-2.1 events/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on a biologic. Malignancies occurred at a rate of 1.3 events/100 person-years in ESPRIT, compared with published rates of 0.5-2.0/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy. Acute MI occurred at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 person-years in ESPRIT, stroke at 0.2 events/100 person-years, and heart failure at less than 0.1 event/100 person-years, versus a collective rate of 0.6-1.5 events/100 person-years in the comparator population.

Another view of the data is that, at 10 years, 99.4% of ESPRIT participants had not experienced an acute MI, 95.9% hadn’t had a malignancy, and 96.1% remained free of serious infection while on adalimumab, Dr. Thaci continued.

Injection-site reactions, a significant source of concern when adalimumab first reached the marketplace, occurred at a rate of 0.2 events/100 person-years over the course of 10 years. Oral candidiasis, active tuberculosis, demyelinating disorders, and lupus-like reactions were rare, each occurring at an incidence of less than 0.1 event/100 person-years.

Dr. Thaci’s 10-year update from the ongoing registry follows an earlier report of the 5-year results (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73[3]:410-9.e6).

The ESPRIT registry is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Thaci reported serving as a consultant to and/or receiving research grants from that pharmaceutical company and nearly two dozen others.

MADRID – Psoriasis patients on adalimumab for up to 10 years in the prospective, observational, international, real-world ESPRIT registry had a sharply reduced likelihood of all-cause mortality, compared with the age- and sex-matched general population in participating countries, Diamant T. Thaci, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“If someone tells you that you as a dermatologist can save patient lives by controlling psoriasis, you may not believe it. But look at this standardized mortality ratio data,” said Dr. Thaci, professor of dermatology and head of the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine at the University of Luebeck (Germany).

Indeed, the standardized in routine clinical practice, was 58% lower than expected, based upon published mortality rate data for the general population in the United States, Canada, and the 10 participating European countries. A total of 144 deaths were predicted in the matched general population, yet only 60 deaths occurred in adalimumab-treated registry participants.

This finding is all the more remarkable because ESPRIT participants had high rates of cardiovascular risk factors, as well as a substantial burden of comorbid conditions, as is typical for patients with chronic moderate to severe psoriasis encountered in real-world clinical practice. It’s a different population than enrollees in the long-term, open-label extensions of phase 3, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trials of biologics in psoriasis, which at the outset typically excluded patients with baseline substantial comorbidities, he noted.

Moreover, the incidence rates of serious infections, malignancies, and cardiovascular events in ESPRIT participants remained stable over time and well within the range of published rates in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy.

“All of this underscores the importance of good control of psoriasis,” Dr. Thaci commented.

The ESPRIT registry began enrolling patients and evaluating them every 6 months in 2008, when the vast majority of dermatologists in clinical practice relied upon Physician Global Assessment (PGA) to evaluate treatment efficacy. For this reason, the PGA, rather than the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, was the main efficacy measure utilized in the registry. The rate of PGA “clear” or “almost clear” was steady over time at 57% at 1 year, 62.1% at 5 years, and 61.5% at 10 years. It should be noted that this was reported in an “as-observed” analysis, which introduces bias favoring a rosier picture of efficacy since by 10 years slightly under half of patients remained on the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

However, the primary focus of this ESPRIT analysis was safety, not efficacy. The rate of serious infections was 1.0 event per 100 person-years on adalimumab, compared with published rates of 0.3-2.1 events/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on a biologic. Malignancies occurred at a rate of 1.3 events/100 person-years in ESPRIT, compared with published rates of 0.5-2.0/100 person-years in psoriasis patients not on biologic therapy. Acute MI occurred at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 person-years in ESPRIT, stroke at 0.2 events/100 person-years, and heart failure at less than 0.1 event/100 person-years, versus a collective rate of 0.6-1.5 events/100 person-years in the comparator population.

Another view of the data is that, at 10 years, 99.4% of ESPRIT participants had not experienced an acute MI, 95.9% hadn’t had a malignancy, and 96.1% remained free of serious infection while on adalimumab, Dr. Thaci continued.

Injection-site reactions, a significant source of concern when adalimumab first reached the marketplace, occurred at a rate of 0.2 events/100 person-years over the course of 10 years. Oral candidiasis, active tuberculosis, demyelinating disorders, and lupus-like reactions were rare, each occurring at an incidence of less than 0.1 event/100 person-years.

Dr. Thaci’s 10-year update from the ongoing registry follows an earlier report of the 5-year results (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73[3]:410-9.e6).

The ESPRIT registry is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Thaci reported serving as a consultant to and/or receiving research grants from that pharmaceutical company and nearly two dozen others.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Psoriasis comorbidities: Biologics may help

SEATTLE – Psoriasis is a complex condition, made more difficult by comorbidities. Psoriatic arthritis is the most common and is frequently discussed. But mental health issues and cardiovascular events also co-occur and can present major complications, according to Jashin Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation, who discussed psoriasis comorbidities at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

Mental health–related issues associated with psoriasis (Psychiatr Danub. 2017 Dec;29[4]:401-6) include sleep disorders (prevalence, 62%), sexual dysfunction (46%), personality disorder (35%), anxiety (30%), adjustment (29%), and depressive disorders (28%); 25% of patients have an accompanying substance abuse disorder. Suicidal ideation and suicidal depression are particularly concerning, and a meta-analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3]:425-40.e2) showed a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation associated with psoriasis.

Such problems aren’t surprising, since psoriasis is a lifelong disease, and many patients’ symptoms aren’t adequately controlled. “A lot of these patients get topical therapies, which is probably not enough, especially if they have severe disease,” said Dr. Wu in an interview.

Dermatologists can sometimes be nervous about biologics because of concerns over increased risk of infection or cancer. That can lead to conservative, topical treatment. Dr. Wu feels that rare side effects shouldn’t deter from aggressive treatment, when appropriate. “It’s better to treat the patient to make sure they’re clear, which may improve their comorbidities as well. In general, if you’re worried, you can send them to other specialists to do monitoring,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Different treatment methods may influence mental health outcomes, according to the PSOLAR study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:70-80). It examined the issue prospectively with over 12,000 psoriasis patients, and found a depression incidence of 3.01 per 100-patient years when treated with biologics, compared with 5.85 for phototherapy and 5.70 for conventional therapy. Put another way, exposure to biologics was associated with a reduced risk of depression, compared with conventional therapies (hazard ratio, 0.76; P = .0367). “It seems to show that biologics have a better improvement of depression symptoms, compared to phototherapy or oral therapy,” said Dr. Wu.

Those results suggest that dermatologists should be on the lookout for mental health issues, though that is a challenge for someone not trained in the field. Dr. Wu takes a simple approach. “I like just asking open-ended questions, like how they’re doing, and if you get a sense that maybe they’re depressed, ask more specific questions about their mood, how they’re feeling, how things are at work, how things are at home.” When things aren’t right, “the key is to try to get them on something that’s going to clear them very quickly. If it’s severe disease, use a biologic that’s going to clear it very quickly,” he added.

Unfortunately, just being clear isn’t a complete guarantee of improved mental health. Dr. Wu had two patients who committed suicide despite significant skin improvement. Patients may have between-visit flare-ups, or regular injections may be a reminder that psoriasis is an ongoing health struggle. Or patients may have other psychological concerns. That underlines the importance of awareness of mental health issues. “You don’t need to refer everyone [to a mental health specialist], but you should have a rolodex where you have someone you can send a patient to if you’re worried,” said Dr. Wu.

As with mental health issues, psoriasis patients are also at elevated risk for a wide range of cardiovascular comorbidities, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure. “As a dermatologist, you may not want to screen for these things, but you can send them to their primary care doctor or a cardiologist,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Also like mental health issues, there is evidence that treatment with biologics may have an outsized protective effect. One study (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Mar 24. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14951) led by Dr. Wu showed that treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitor led to a significant reduction in major adverse cardiac events, compared with topical therapy (propensity score–adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), while phototherapy or oral therapy trended towards an increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00-1.28). Another analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:81-90) from Dr. Wu’s group that included about 380,000 psoriasis patients found that treatment with TNF-alpha inhibitors was associated with fewer major cardiovascular events, compared with treatment with methotrexate (adjusted HR, 0.55; P less than .0001). Individual analyses showed associated reductions in stroke or transient ischemic attack (aHR, 0.55; P less than .0001), unstable angina (aHR, 0.58; P = .0024), and MI (aHR, 0.49; P = .0002). TNF-alpha inhibitors also seem to beat out phototherapy with respect to major cardiovascular events (aHR, 0.77; P = .046. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul;79[1]:60-6).

More direct evidence of the benefit of biologics comes from the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31), which randomized more than 10,000 patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes to receive the IL-1 beta-blocker canakinumab or placebo. Canakinumab was associated with significant reductions in nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death at 150 mg (HR, 0.85; P = .021) and 300 mg (HR, 0.86; P = .031), but not at 50 mg.

The bottom line, said Dr. Wu, is that psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis should be treated early with TNF-alpha inhibitors or IL-17 inhibitors in an effort to improve mental health, cardiovascular, and psoriatic arthritis outcomes.

Dr. Wu has been a consultant or speaker for, or done research on behalf of, AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America.

The meeting is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – Psoriasis is a complex condition, made more difficult by comorbidities. Psoriatic arthritis is the most common and is frequently discussed. But mental health issues and cardiovascular events also co-occur and can present major complications, according to Jashin Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation, who discussed psoriasis comorbidities at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

Mental health–related issues associated with psoriasis (Psychiatr Danub. 2017 Dec;29[4]:401-6) include sleep disorders (prevalence, 62%), sexual dysfunction (46%), personality disorder (35%), anxiety (30%), adjustment (29%), and depressive disorders (28%); 25% of patients have an accompanying substance abuse disorder. Suicidal ideation and suicidal depression are particularly concerning, and a meta-analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3]:425-40.e2) showed a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation associated with psoriasis.

Such problems aren’t surprising, since psoriasis is a lifelong disease, and many patients’ symptoms aren’t adequately controlled. “A lot of these patients get topical therapies, which is probably not enough, especially if they have severe disease,” said Dr. Wu in an interview.

Dermatologists can sometimes be nervous about biologics because of concerns over increased risk of infection or cancer. That can lead to conservative, topical treatment. Dr. Wu feels that rare side effects shouldn’t deter from aggressive treatment, when appropriate. “It’s better to treat the patient to make sure they’re clear, which may improve their comorbidities as well. In general, if you’re worried, you can send them to other specialists to do monitoring,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Different treatment methods may influence mental health outcomes, according to the PSOLAR study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:70-80). It examined the issue prospectively with over 12,000 psoriasis patients, and found a depression incidence of 3.01 per 100-patient years when treated with biologics, compared with 5.85 for phototherapy and 5.70 for conventional therapy. Put another way, exposure to biologics was associated with a reduced risk of depression, compared with conventional therapies (hazard ratio, 0.76; P = .0367). “It seems to show that biologics have a better improvement of depression symptoms, compared to phototherapy or oral therapy,” said Dr. Wu.

Those results suggest that dermatologists should be on the lookout for mental health issues, though that is a challenge for someone not trained in the field. Dr. Wu takes a simple approach. “I like just asking open-ended questions, like how they’re doing, and if you get a sense that maybe they’re depressed, ask more specific questions about their mood, how they’re feeling, how things are at work, how things are at home.” When things aren’t right, “the key is to try to get them on something that’s going to clear them very quickly. If it’s severe disease, use a biologic that’s going to clear it very quickly,” he added.

Unfortunately, just being clear isn’t a complete guarantee of improved mental health. Dr. Wu had two patients who committed suicide despite significant skin improvement. Patients may have between-visit flare-ups, or regular injections may be a reminder that psoriasis is an ongoing health struggle. Or patients may have other psychological concerns. That underlines the importance of awareness of mental health issues. “You don’t need to refer everyone [to a mental health specialist], but you should have a rolodex where you have someone you can send a patient to if you’re worried,” said Dr. Wu.

As with mental health issues, psoriasis patients are also at elevated risk for a wide range of cardiovascular comorbidities, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure. “As a dermatologist, you may not want to screen for these things, but you can send them to their primary care doctor or a cardiologist,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Also like mental health issues, there is evidence that treatment with biologics may have an outsized protective effect. One study (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Mar 24. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14951) led by Dr. Wu showed that treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitor led to a significant reduction in major adverse cardiac events, compared with topical therapy (propensity score–adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), while phototherapy or oral therapy trended towards an increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00-1.28). Another analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:81-90) from Dr. Wu’s group that included about 380,000 psoriasis patients found that treatment with TNF-alpha inhibitors was associated with fewer major cardiovascular events, compared with treatment with methotrexate (adjusted HR, 0.55; P less than .0001). Individual analyses showed associated reductions in stroke or transient ischemic attack (aHR, 0.55; P less than .0001), unstable angina (aHR, 0.58; P = .0024), and MI (aHR, 0.49; P = .0002). TNF-alpha inhibitors also seem to beat out phototherapy with respect to major cardiovascular events (aHR, 0.77; P = .046. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul;79[1]:60-6).

More direct evidence of the benefit of biologics comes from the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31), which randomized more than 10,000 patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes to receive the IL-1 beta-blocker canakinumab or placebo. Canakinumab was associated with significant reductions in nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death at 150 mg (HR, 0.85; P = .021) and 300 mg (HR, 0.86; P = .031), but not at 50 mg.

The bottom line, said Dr. Wu, is that psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis should be treated early with TNF-alpha inhibitors or IL-17 inhibitors in an effort to improve mental health, cardiovascular, and psoriatic arthritis outcomes.

Dr. Wu has been a consultant or speaker for, or done research on behalf of, AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America.

The meeting is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – Psoriasis is a complex condition, made more difficult by comorbidities. Psoriatic arthritis is the most common and is frequently discussed. But mental health issues and cardiovascular events also co-occur and can present major complications, according to Jashin Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation, who discussed psoriasis comorbidities at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

Mental health–related issues associated with psoriasis (Psychiatr Danub. 2017 Dec;29[4]:401-6) include sleep disorders (prevalence, 62%), sexual dysfunction (46%), personality disorder (35%), anxiety (30%), adjustment (29%), and depressive disorders (28%); 25% of patients have an accompanying substance abuse disorder. Suicidal ideation and suicidal depression are particularly concerning, and a meta-analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3]:425-40.e2) showed a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation associated with psoriasis.

Such problems aren’t surprising, since psoriasis is a lifelong disease, and many patients’ symptoms aren’t adequately controlled. “A lot of these patients get topical therapies, which is probably not enough, especially if they have severe disease,” said Dr. Wu in an interview.

Dermatologists can sometimes be nervous about biologics because of concerns over increased risk of infection or cancer. That can lead to conservative, topical treatment. Dr. Wu feels that rare side effects shouldn’t deter from aggressive treatment, when appropriate. “It’s better to treat the patient to make sure they’re clear, which may improve their comorbidities as well. In general, if you’re worried, you can send them to other specialists to do monitoring,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Different treatment methods may influence mental health outcomes, according to the PSOLAR study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78[1]:70-80). It examined the issue prospectively with over 12,000 psoriasis patients, and found a depression incidence of 3.01 per 100-patient years when treated with biologics, compared with 5.85 for phototherapy and 5.70 for conventional therapy. Put another way, exposure to biologics was associated with a reduced risk of depression, compared with conventional therapies (hazard ratio, 0.76; P = .0367). “It seems to show that biologics have a better improvement of depression symptoms, compared to phototherapy or oral therapy,” said Dr. Wu.

Those results suggest that dermatologists should be on the lookout for mental health issues, though that is a challenge for someone not trained in the field. Dr. Wu takes a simple approach. “I like just asking open-ended questions, like how they’re doing, and if you get a sense that maybe they’re depressed, ask more specific questions about their mood, how they’re feeling, how things are at work, how things are at home.” When things aren’t right, “the key is to try to get them on something that’s going to clear them very quickly. If it’s severe disease, use a biologic that’s going to clear it very quickly,” he added.

Unfortunately, just being clear isn’t a complete guarantee of improved mental health. Dr. Wu had two patients who committed suicide despite significant skin improvement. Patients may have between-visit flare-ups, or regular injections may be a reminder that psoriasis is an ongoing health struggle. Or patients may have other psychological concerns. That underlines the importance of awareness of mental health issues. “You don’t need to refer everyone [to a mental health specialist], but you should have a rolodex where you have someone you can send a patient to if you’re worried,” said Dr. Wu.

As with mental health issues, psoriasis patients are also at elevated risk for a wide range of cardiovascular comorbidities, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure. “As a dermatologist, you may not want to screen for these things, but you can send them to their primary care doctor or a cardiologist,” Dr. Wu said in the interview.

Also like mental health issues, there is evidence that treatment with biologics may have an outsized protective effect. One study (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Mar 24. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14951) led by Dr. Wu showed that treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitor led to a significant reduction in major adverse cardiac events, compared with topical therapy (propensity score–adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98), while phototherapy or oral therapy trended towards an increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00-1.28). Another analysis (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:81-90) from Dr. Wu’s group that included about 380,000 psoriasis patients found that treatment with TNF-alpha inhibitors was associated with fewer major cardiovascular events, compared with treatment with methotrexate (adjusted HR, 0.55; P less than .0001). Individual analyses showed associated reductions in stroke or transient ischemic attack (aHR, 0.55; P less than .0001), unstable angina (aHR, 0.58; P = .0024), and MI (aHR, 0.49; P = .0002). TNF-alpha inhibitors also seem to beat out phototherapy with respect to major cardiovascular events (aHR, 0.77; P = .046. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul;79[1]:60-6).

More direct evidence of the benefit of biologics comes from the CANTOS trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31), which randomized more than 10,000 patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes to receive the IL-1 beta-blocker canakinumab or placebo. Canakinumab was associated with significant reductions in nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death at 150 mg (HR, 0.85; P = .021) and 300 mg (HR, 0.86; P = .031), but not at 50 mg.

The bottom line, said Dr. Wu, is that psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis should be treated early with TNF-alpha inhibitors or IL-17 inhibitors in an effort to improve mental health, cardiovascular, and psoriatic arthritis outcomes.

Dr. Wu has been a consultant or speaker for, or done research on behalf of, AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America.

The meeting is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM COASTAL DERM

Guide to the guidelines: Biologics for psoriasis

SEATTLE – The availability of biologics for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has exploded in recent years, with 11 biologics now approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Targets include four separate mechanisms: inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, IL-12/23, and IL-17. The surfeit of treatment options can be a little overwhelming.

“It can be confusing. We have a lot of choices, but the good news is that most of our choices are excellent, and they treat both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. That’s very important because, when we think of our psoriasis patients, we need to think not only about their skin but also their joint involvement. Assessment of psoriatic arthritis will drive some of our therapeutic [decisions],” April Armstrong, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

In April, the American Academy of Dermatology came to the rescue with comprehensive guidelines. Aside from general advice, the guidelines “provide tips for monitoring as well as dose escalation, which will be very helpful in daily practice,” Dr. Armstrong said in an interview.

The best studied of the biologics with respect to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are the IL-17 inhibitors and TNF inhibitors, she said. While TNF inhibitors have traditionally been the treatment of choice for both conditions, “I think these days, people realize that IL-17 inhibitors can be just as good.”

A head-to-head study of the IL-17 inhibitor ixekizumab and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab, presented at the EULAR Congress, looked at a combined outcome of skin and joints and found ixekizumab to be superior, though the study design’s inclusion of a skin outcome may have favored ixekizumab (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.8709).

A few other head-to-head studies have been performed, but properly ranking all 11 biologics would require dozens of clinical trials. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting last March, Dr. Armstrong presented the results of a network meta-analysis of anti-TNF agents, anti-interleukin agents, anti–phosphodiesterase 4 agents, and fumaric acid esters (J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.488). That study, funded by AbbVie, compared the individual agents to a collective placebo group and concluded that anti-interleukin agents generate the highest level of PASI 90/100 response rate. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, and guselkumab, all IL inhibitors, achieved the best marks over the primary response period.

The AAD guidelines include recommendations for tests to be done upon initiation of a biologic, including a tuberculosis test, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and tests for hepatitis B and C. TB testing should be performed annually during treatment.

The guidelines also include recommendations for dose escalation, which can provide leverage for getting coverage approved. “One can use those guidelines to show payers how dose escalation can be done, so that [physicians] can potentially get more access to medications for their patients,” Dr. Armstrong said at the meeting jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guideline also ranks the existing evidence supporting individual biologics for the treatment of psoriasis subtypes. For example, for the treatment of moderate to severe scalp psoriasis, etanercept and guselkumab have consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence supporting them; infliximab, adalimumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab are recommended based on inconsistent or limited quality patient-oriented evidence; and ustekinumab is supported only by consensus opinion, case studies, or disease-oriented evidence. The guidelines provide similar categorization of biologics for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque type palmoplantar psoriasis, moderate to severe psoriasis affecting the nails, adults with pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis, and adults with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Armstrong is a research investigator and/or advisor to AbbVie, Janssen, Lily, LEO Pharma, Novartis, UCB, Ortho Dermatologics, Dermera, Regeneron, BMS, Dermavant, and KHK. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – The availability of biologics for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has exploded in recent years, with 11 biologics now approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Targets include four separate mechanisms: inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, IL-12/23, and IL-17. The surfeit of treatment options can be a little overwhelming.

“It can be confusing. We have a lot of choices, but the good news is that most of our choices are excellent, and they treat both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. That’s very important because, when we think of our psoriasis patients, we need to think not only about their skin but also their joint involvement. Assessment of psoriatic arthritis will drive some of our therapeutic [decisions],” April Armstrong, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

In April, the American Academy of Dermatology came to the rescue with comprehensive guidelines. Aside from general advice, the guidelines “provide tips for monitoring as well as dose escalation, which will be very helpful in daily practice,” Dr. Armstrong said in an interview.

The best studied of the biologics with respect to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are the IL-17 inhibitors and TNF inhibitors, she said. While TNF inhibitors have traditionally been the treatment of choice for both conditions, “I think these days, people realize that IL-17 inhibitors can be just as good.”

A head-to-head study of the IL-17 inhibitor ixekizumab and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab, presented at the EULAR Congress, looked at a combined outcome of skin and joints and found ixekizumab to be superior, though the study design’s inclusion of a skin outcome may have favored ixekizumab (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.8709).

A few other head-to-head studies have been performed, but properly ranking all 11 biologics would require dozens of clinical trials. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting last March, Dr. Armstrong presented the results of a network meta-analysis of anti-TNF agents, anti-interleukin agents, anti–phosphodiesterase 4 agents, and fumaric acid esters (J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.488). That study, funded by AbbVie, compared the individual agents to a collective placebo group and concluded that anti-interleukin agents generate the highest level of PASI 90/100 response rate. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, and guselkumab, all IL inhibitors, achieved the best marks over the primary response period.

The AAD guidelines include recommendations for tests to be done upon initiation of a biologic, including a tuberculosis test, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and tests for hepatitis B and C. TB testing should be performed annually during treatment.

The guidelines also include recommendations for dose escalation, which can provide leverage for getting coverage approved. “One can use those guidelines to show payers how dose escalation can be done, so that [physicians] can potentially get more access to medications for their patients,” Dr. Armstrong said at the meeting jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guideline also ranks the existing evidence supporting individual biologics for the treatment of psoriasis subtypes. For example, for the treatment of moderate to severe scalp psoriasis, etanercept and guselkumab have consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence supporting them; infliximab, adalimumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab are recommended based on inconsistent or limited quality patient-oriented evidence; and ustekinumab is supported only by consensus opinion, case studies, or disease-oriented evidence. The guidelines provide similar categorization of biologics for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque type palmoplantar psoriasis, moderate to severe psoriasis affecting the nails, adults with pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis, and adults with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Armstrong is a research investigator and/or advisor to AbbVie, Janssen, Lily, LEO Pharma, Novartis, UCB, Ortho Dermatologics, Dermera, Regeneron, BMS, Dermavant, and KHK. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – The availability of biologics for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has exploded in recent years, with 11 biologics now approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Targets include four separate mechanisms: inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, IL-12/23, and IL-17. The surfeit of treatment options can be a little overwhelming.

“It can be confusing. We have a lot of choices, but the good news is that most of our choices are excellent, and they treat both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. That’s very important because, when we think of our psoriasis patients, we need to think not only about their skin but also their joint involvement. Assessment of psoriatic arthritis will drive some of our therapeutic [decisions],” April Armstrong, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

In April, the American Academy of Dermatology came to the rescue with comprehensive guidelines. Aside from general advice, the guidelines “provide tips for monitoring as well as dose escalation, which will be very helpful in daily practice,” Dr. Armstrong said in an interview.

The best studied of the biologics with respect to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are the IL-17 inhibitors and TNF inhibitors, she said. While TNF inhibitors have traditionally been the treatment of choice for both conditions, “I think these days, people realize that IL-17 inhibitors can be just as good.”

A head-to-head study of the IL-17 inhibitor ixekizumab and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab, presented at the EULAR Congress, looked at a combined outcome of skin and joints and found ixekizumab to be superior, though the study design’s inclusion of a skin outcome may have favored ixekizumab (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jun. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.8709).

A few other head-to-head studies have been performed, but properly ranking all 11 biologics would require dozens of clinical trials. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting last March, Dr. Armstrong presented the results of a network meta-analysis of anti-TNF agents, anti-interleukin agents, anti–phosphodiesterase 4 agents, and fumaric acid esters (J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.488). That study, funded by AbbVie, compared the individual agents to a collective placebo group and concluded that anti-interleukin agents generate the highest level of PASI 90/100 response rate. Risankizumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, and guselkumab, all IL inhibitors, achieved the best marks over the primary response period.

The AAD guidelines include recommendations for tests to be done upon initiation of a biologic, including a tuberculosis test, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and tests for hepatitis B and C. TB testing should be performed annually during treatment.

The guidelines also include recommendations for dose escalation, which can provide leverage for getting coverage approved. “One can use those guidelines to show payers how dose escalation can be done, so that [physicians] can potentially get more access to medications for their patients,” Dr. Armstrong said at the meeting jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guideline also ranks the existing evidence supporting individual biologics for the treatment of psoriasis subtypes. For example, for the treatment of moderate to severe scalp psoriasis, etanercept and guselkumab have consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence supporting them; infliximab, adalimumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab are recommended based on inconsistent or limited quality patient-oriented evidence; and ustekinumab is supported only by consensus opinion, case studies, or disease-oriented evidence. The guidelines provide similar categorization of biologics for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque type palmoplantar psoriasis, moderate to severe psoriasis affecting the nails, adults with pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis, and adults with psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Armstrong is a research investigator and/or advisor to AbbVie, Janssen, Lily, LEO Pharma, Novartis, UCB, Ortho Dermatologics, Dermera, Regeneron, BMS, Dermavant, and KHK. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM COASTAL DERM

Guttate Psoriasis Following Presumed Coxsackievirus A

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

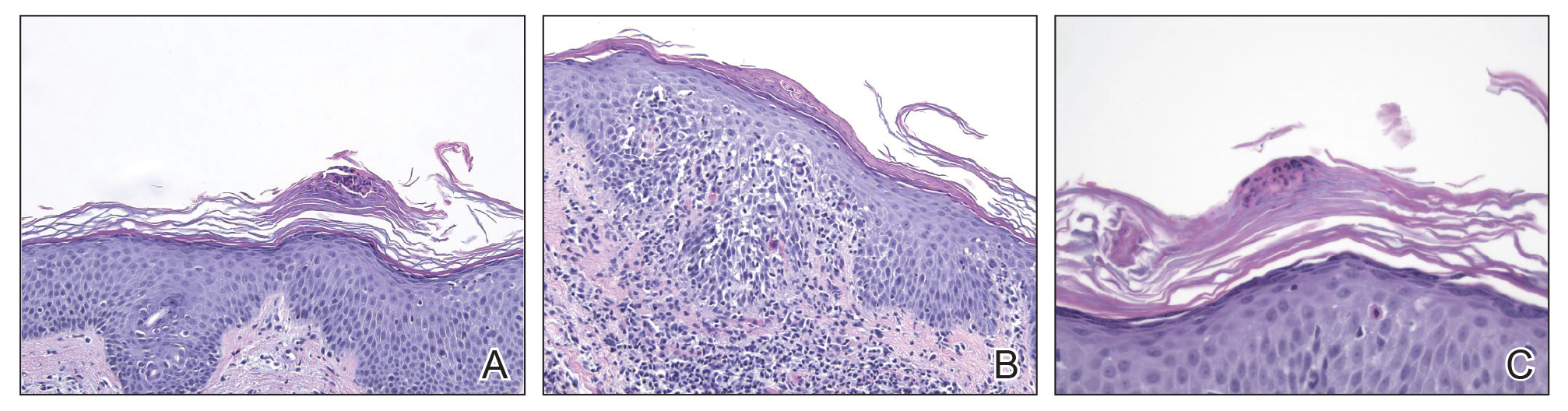

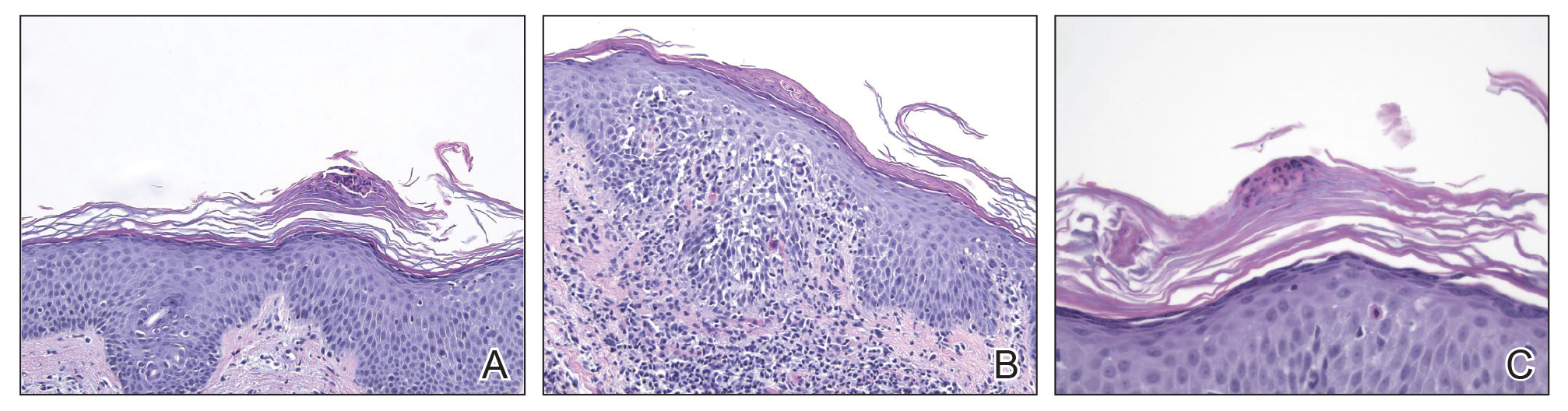

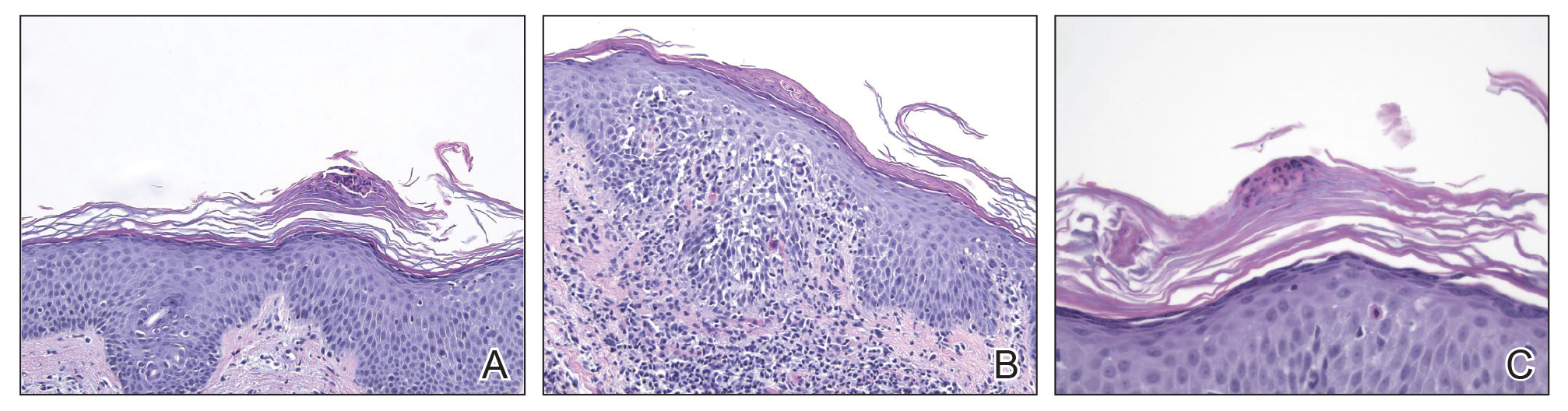

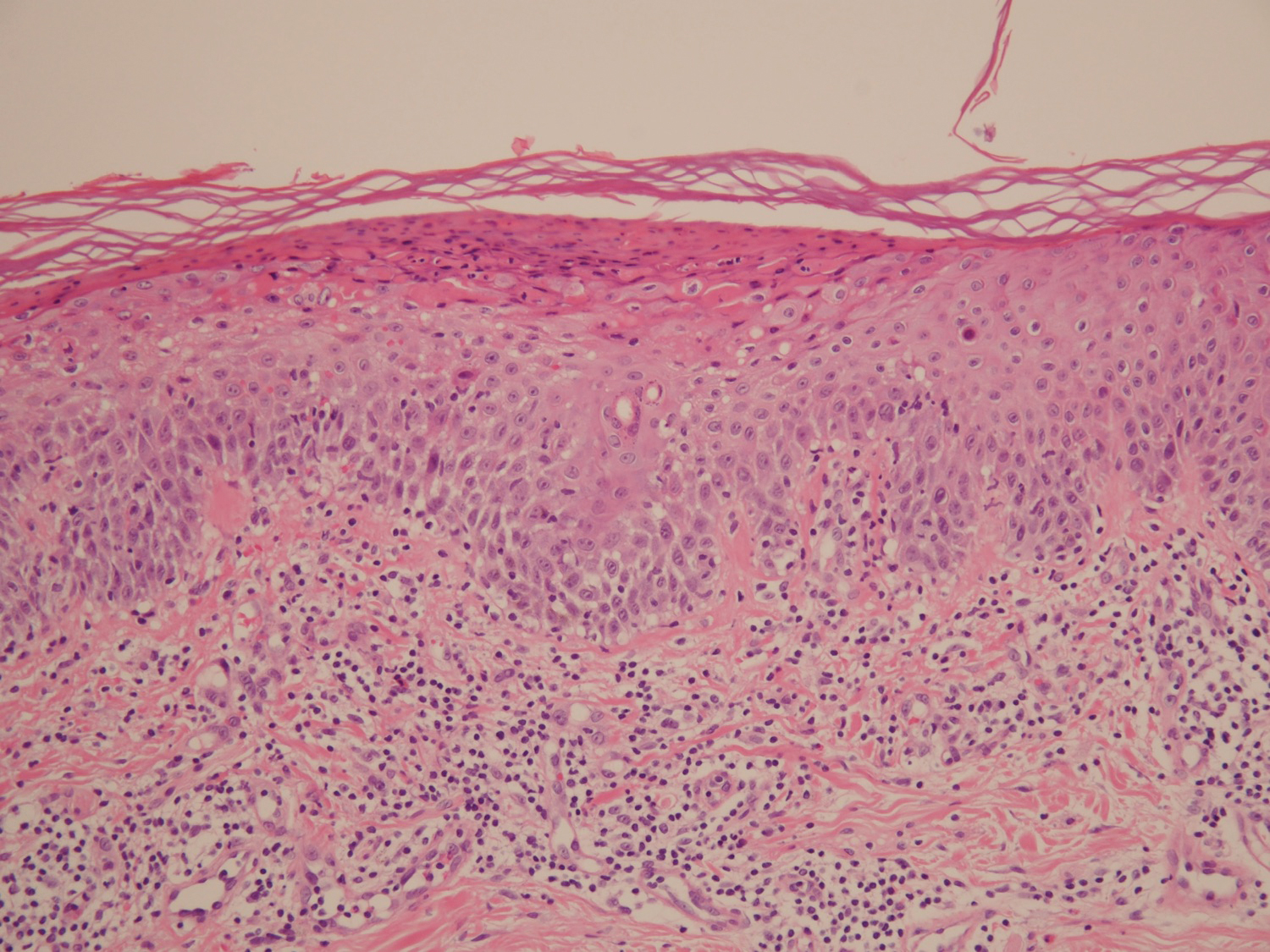

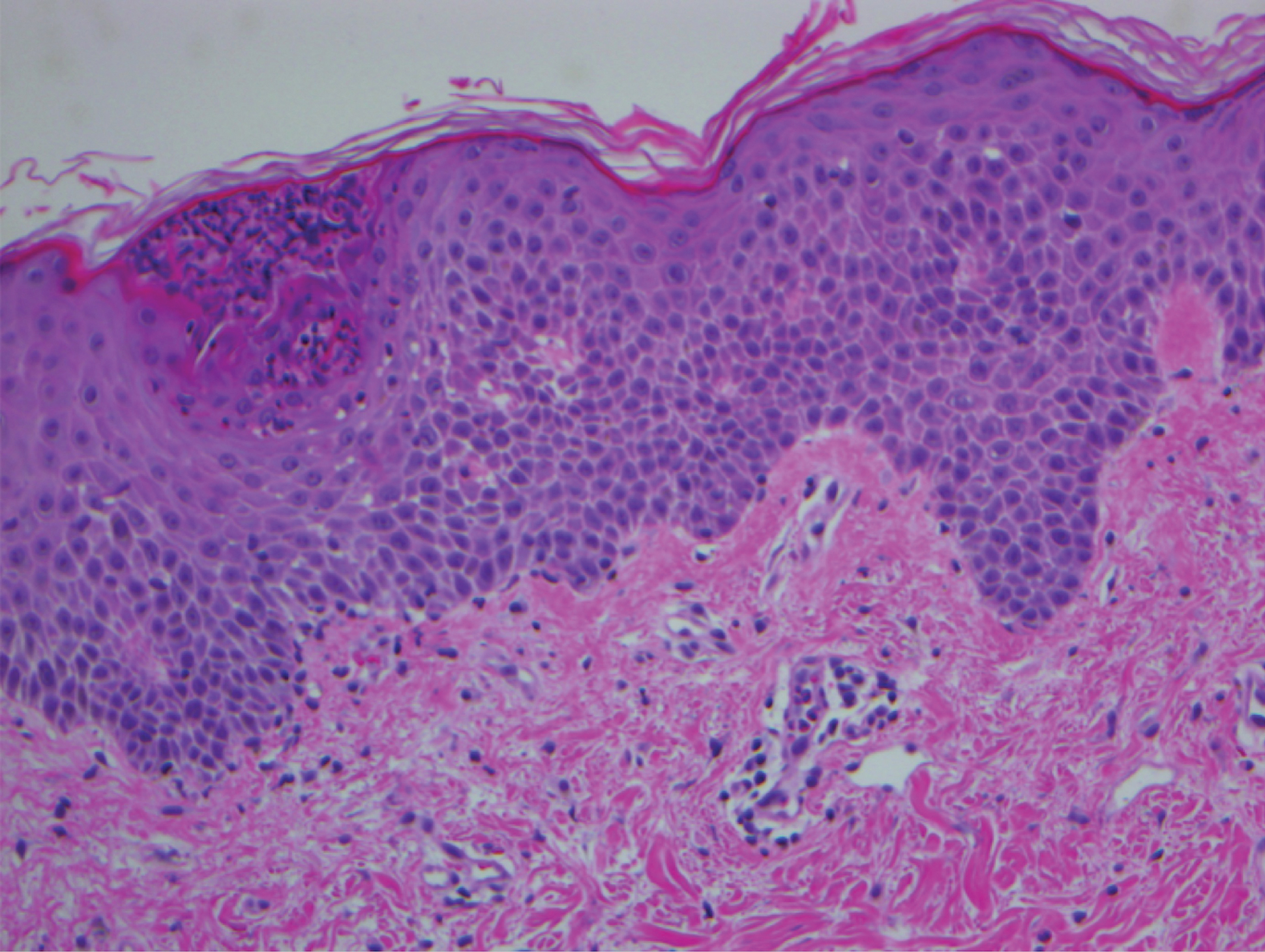

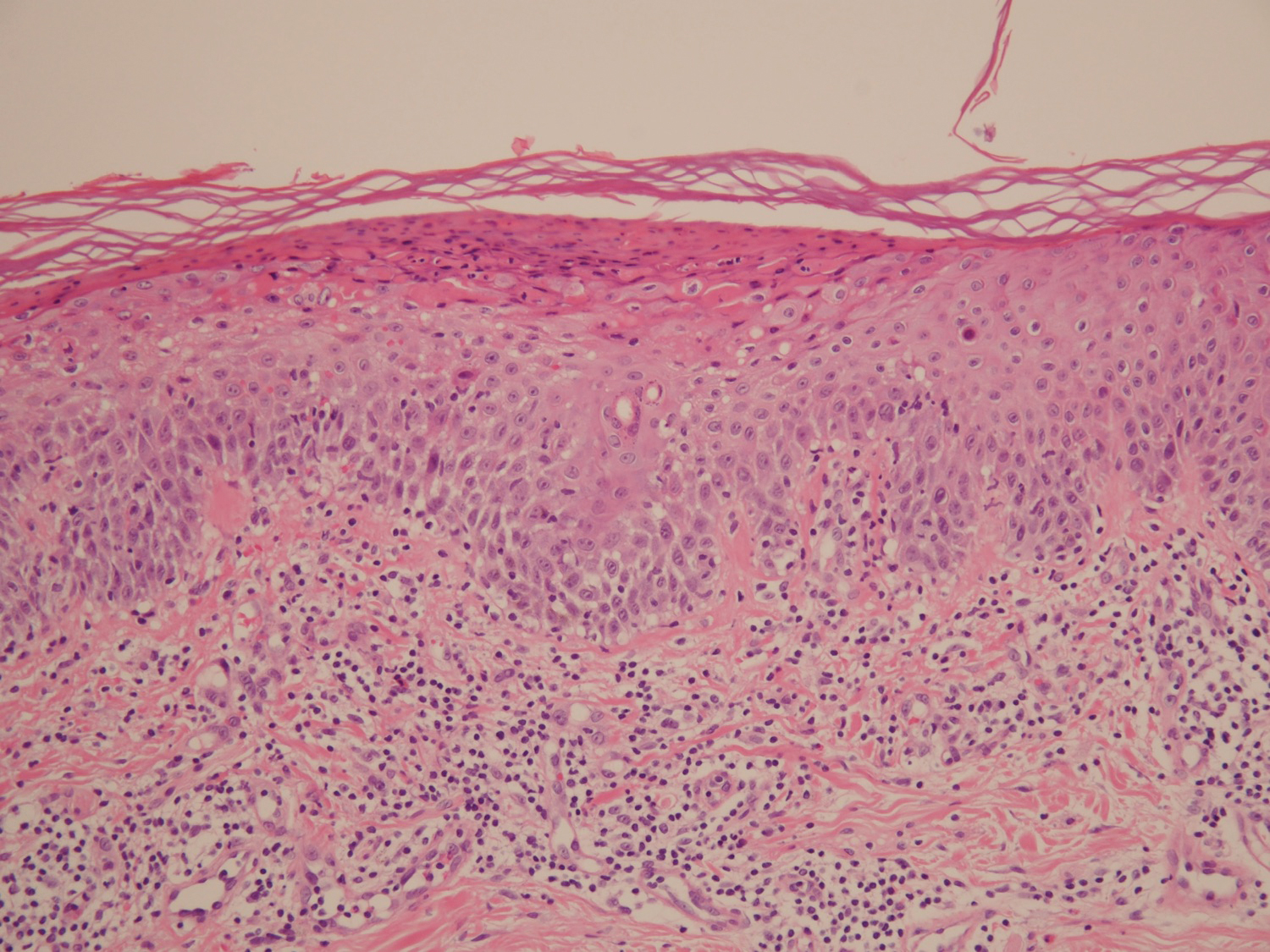

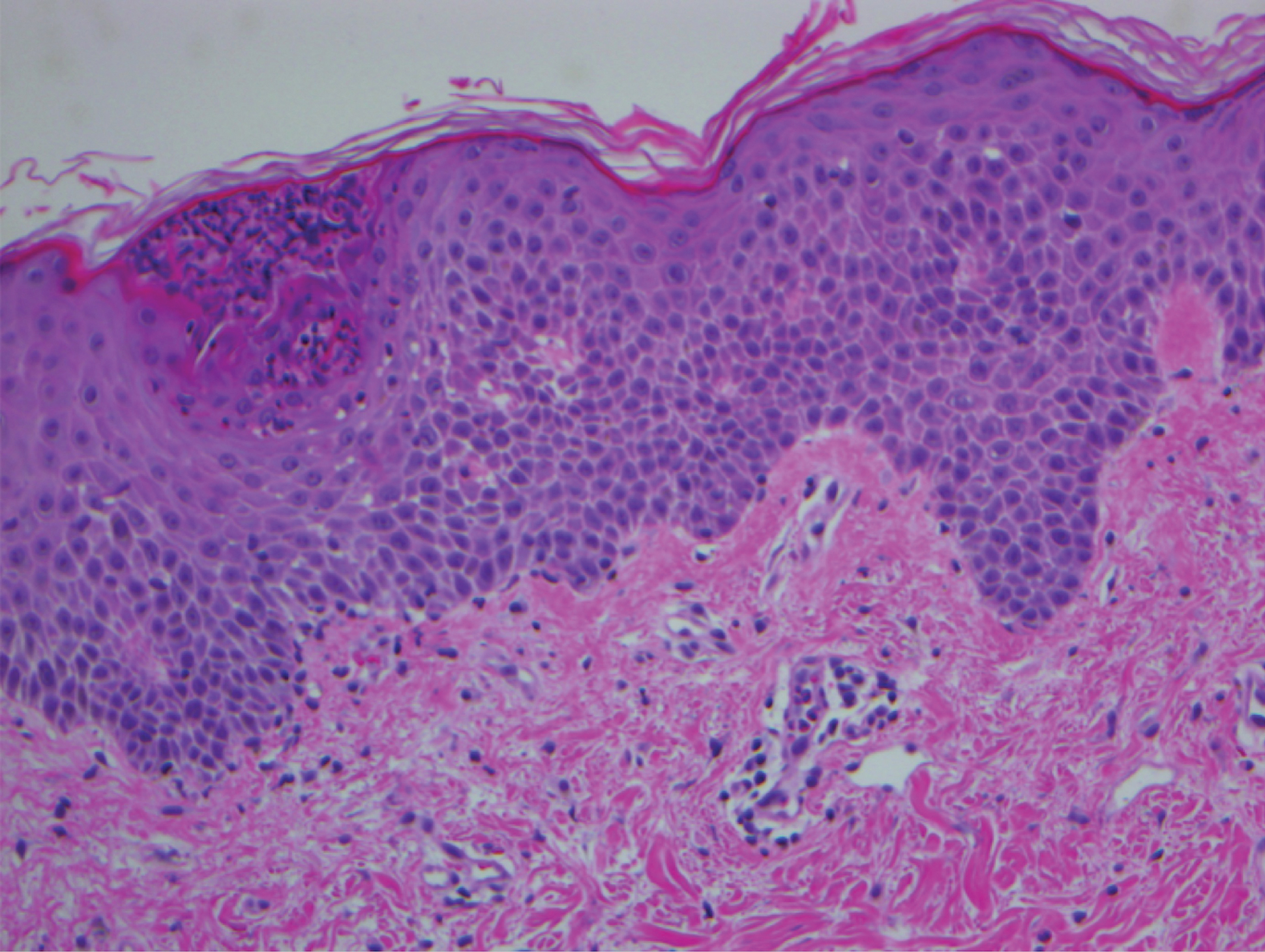

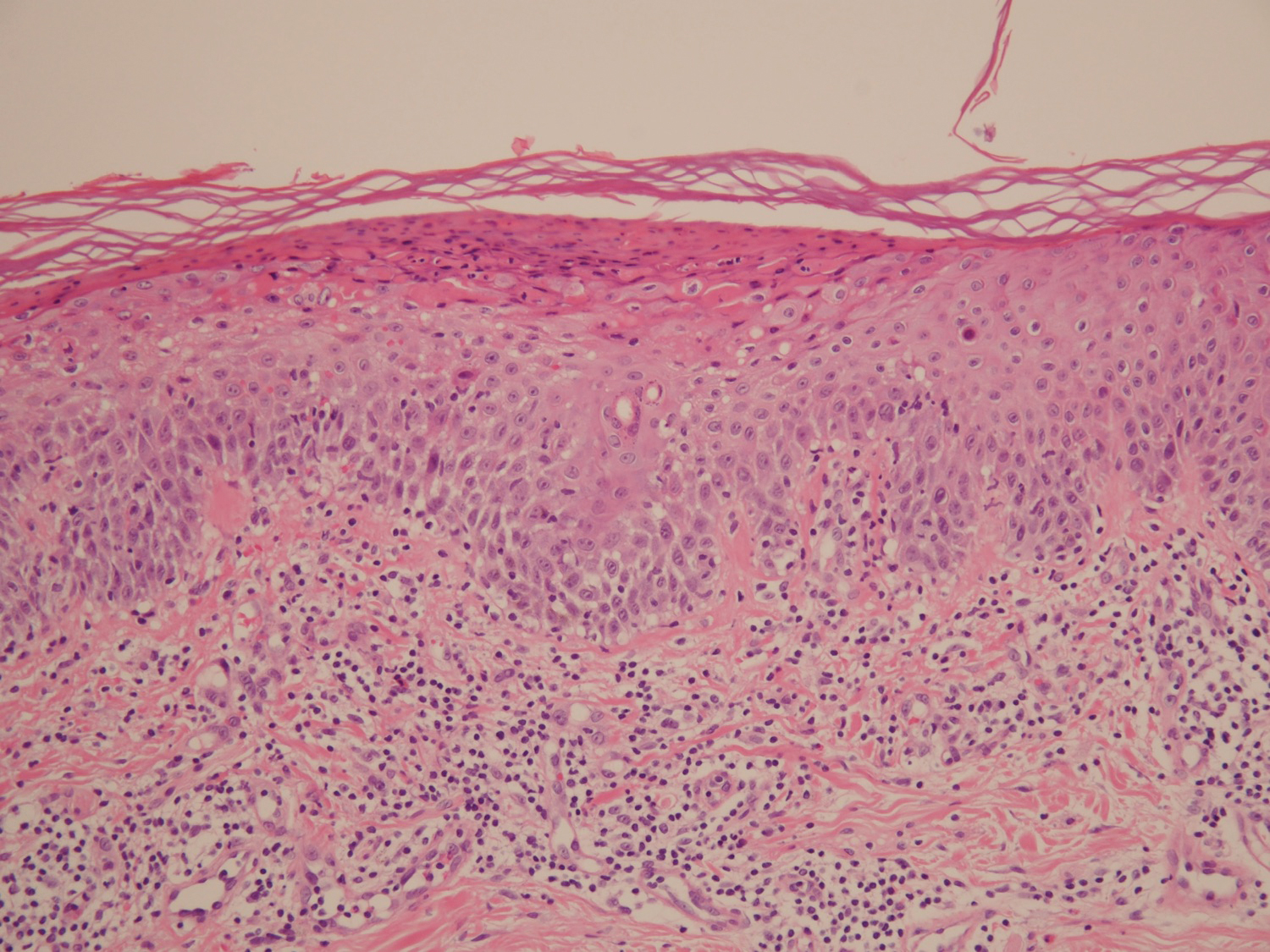

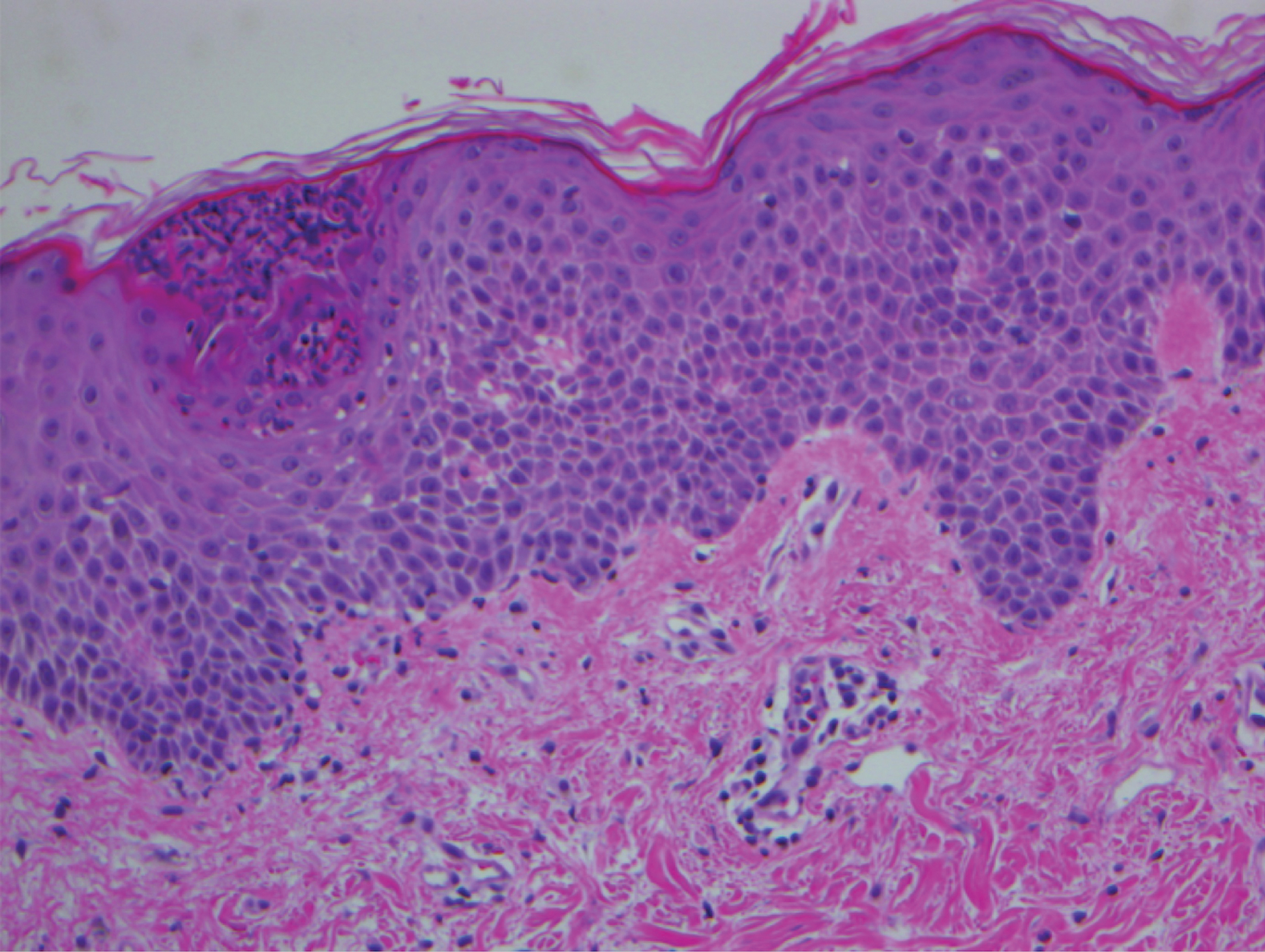

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

Practice Points

- Inquire about any illnesses preceding derma-tologic diseases.

- There may be additional microbial triggers for dermatologic diseases.

Psoriasis Journal Scan: September 2019

Psychological and Sexual Consequences of Psoriasis Vulgaris on Patients and Their Partners.

Alariny AF, Farid CI, Elweshahi HM, Abbood SS. J Sex Med. 2019 Sep 18.

In a comparative cross-sectional study that aimed to evaluate the psychopathological and sexual aspects of psoriasis vulgaris in patients and their partners, the sample included 220 psoriasis vulgaris patients (110 males and 110 females), their consenting partners, and 220 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The main outcome measures were frequency of depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and sexual dysfunction in psoriasis vulgaris patients, partners, and controls; the domains of sexual function affected in the studied groups; and the etiology of erectile dysfunction in affected psoriatic males.

Ceramide- and Keratolytic-containing Body Cleanser and Cream Application in Patients with Psoriasis: Outcomes from a Consumer Usage Study.

Del Rosso JQ. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019 Jul;12(7):18-21

Ceramides are epidermal lipids that play an essential role in stratum corneum function, including maintaining physiologic permeability barrier properties. The role of ceramides in the maintenance and repair of epidermal barrier function is believed to be valuable in the treatment of psoriasis. Normalization of corneocyte desquamation and the incorporation of agents that promote desquamation to reduce hyperkeratosis are also regarded as key factors in psoriasis management. Based on results reported by the study patients, the evaluated ceramide/keratolytic-containing cream and cleanser both yielded a high level of patient acceptance regarding improvement in skin characteristics in patients with psoriasis, including when used as a combination adjunctive regimen.

Split thickness skin graft in active psoriasis in patient with clear cell variant squamous cell carcinoma.

Scupham L, Ingle A. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Sep 16;12(9).

The case report discusses split thickness skin grafting in a patient with active psoriasis. This also reports a case of a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma.

Epicardial Adipose Tissue Inflammation Can Cause the Distinctive Pattern of Cardiovascular Disorders Seen in Psoriasis.

Packer M. Am J Med. 2019 Sep 11.

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disorder that can target adipose tissue; the resulting adipocyte dysfunction is manifest clinically as the metabolic syndrome, which is present in ≈20-40% of patients. Epicardial adipose tissue inflammation is likely responsible for a distinctive pattern of cardiovascular disorders, consisting of: accelerated coronary atherosclerosis leading to myocardial infarction, atrial myopathy leading to atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic stroke, and ventricular myopathy leading to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. If cardiovascular inflammation drives these risks, then treatments that focus on blood pressure, lipids and glucose will not ameliorate the burden of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis, especially in those who are young and have severe inflammation. Instead, interventions that alleviate systemic and adipose tissue inflammation may not only minimize the risks of atrial fibrillation and heart failure, but may also have favorable effects on the severity of psoriasis. Viewed from this perspective, the known link between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease is not related to the influence of the individual diagnostic components of the metabolic syndrome.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound can improve referrals from dermatology to rheumatology for patients with psoriasis.

Solmaz D, Bakirci S, Al Onazi A, Al Osaimi N, Fahim S, Aydin SZ. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Sep 10.

Psoriasis affects 1-3% of the population and up to 1/3 of psoriasis patients have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Non-specific musculoskeletal complaints are even higher, being around 50%. Detecting early signs of PsA and early treatments are crucial to improve the outcomes to prevent progressive, damaging arthritis. Due to the high frequency of non-specific pain in psoriasis, it is not possible for every psoriasis patient with joint pain to be assessed by a rheumato

Psychological and Sexual Consequences of Psoriasis Vulgaris on Patients and Their Partners.

Alariny AF, Farid CI, Elweshahi HM, Abbood SS. J Sex Med. 2019 Sep 18.

In a comparative cross-sectional study that aimed to evaluate the psychopathological and sexual aspects of psoriasis vulgaris in patients and their partners, the sample included 220 psoriasis vulgaris patients (110 males and 110 females), their consenting partners, and 220 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The main outcome measures were frequency of depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and sexual dysfunction in psoriasis vulgaris patients, partners, and controls; the domains of sexual function affected in the studied groups; and the etiology of erectile dysfunction in affected psoriatic males.

Ceramide- and Keratolytic-containing Body Cleanser and Cream Application in Patients with Psoriasis: Outcomes from a Consumer Usage Study.

Del Rosso JQ. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019 Jul;12(7):18-21

Ceramides are epidermal lipids that play an essential role in stratum corneum function, including maintaining physiologic permeability barrier properties. The role of ceramides in the maintenance and repair of epidermal barrier function is believed to be valuable in the treatment of psoriasis. Normalization of corneocyte desquamation and the incorporation of agents that promote desquamation to reduce hyperkeratosis are also regarded as key factors in psoriasis management. Based on results reported by the study patients, the evaluated ceramide/keratolytic-containing cream and cleanser both yielded a high level of patient acceptance regarding improvement in skin characteristics in patients with psoriasis, including when used as a combination adjunctive regimen.

Split thickness skin graft in active psoriasis in patient with clear cell variant squamous cell carcinoma.

Scupham L, Ingle A. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Sep 16;12(9).

The case report discusses split thickness skin grafting in a patient with active psoriasis. This also reports a case of a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma.

Epicardial Adipose Tissue Inflammation Can Cause the Distinctive Pattern of Cardiovascular Disorders Seen in Psoriasis.

Packer M. Am J Med. 2019 Sep 11.

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disorder that can target adipose tissue; the resulting adipocyte dysfunction is manifest clinically as the metabolic syndrome, which is present in ≈20-40% of patients. Epicardial adipose tissue inflammation is likely responsible for a distinctive pattern of cardiovascular disorders, consisting of: accelerated coronary atherosclerosis leading to myocardial infarction, atrial myopathy leading to atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic stroke, and ventricular myopathy leading to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. If cardiovascular inflammation drives these risks, then treatments that focus on blood pressure, lipids and glucose will not ameliorate the burden of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis, especially in those who are young and have severe inflammation. Instead, interventions that alleviate systemic and adipose tissue inflammation may not only minimize the risks of atrial fibrillation and heart failure, but may also have favorable effects on the severity of psoriasis. Viewed from this perspective, the known link between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease is not related to the influence of the individual diagnostic components of the metabolic syndrome.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound can improve referrals from dermatology to rheumatology for patients with psoriasis.

Solmaz D, Bakirci S, Al Onazi A, Al Osaimi N, Fahim S, Aydin SZ. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Sep 10.

Psoriasis affects 1-3% of the population and up to 1/3 of psoriasis patients have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Non-specific musculoskeletal complaints are even higher, being around 50%. Detecting early signs of PsA and early treatments are crucial to improve the outcomes to prevent progressive, damaging arthritis. Due to the high frequency of non-specific pain in psoriasis, it is not possible for every psoriasis patient with joint pain to be assessed by a rheumato

Psychological and Sexual Consequences of Psoriasis Vulgaris on Patients and Their Partners.

Alariny AF, Farid CI, Elweshahi HM, Abbood SS. J Sex Med. 2019 Sep 18.

In a comparative cross-sectional study that aimed to evaluate the psychopathological and sexual aspects of psoriasis vulgaris in patients and their partners, the sample included 220 psoriasis vulgaris patients (110 males and 110 females), their consenting partners, and 220 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The main outcome measures were frequency of depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and sexual dysfunction in psoriasis vulgaris patients, partners, and controls; the domains of sexual function affected in the studied groups; and the etiology of erectile dysfunction in affected psoriatic males.

Ceramide- and Keratolytic-containing Body Cleanser and Cream Application in Patients with Psoriasis: Outcomes from a Consumer Usage Study.

Del Rosso JQ. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019 Jul;12(7):18-21

Ceramides are epidermal lipids that play an essential role in stratum corneum function, including maintaining physiologic permeability barrier properties. The role of ceramides in the maintenance and repair of epidermal barrier function is believed to be valuable in the treatment of psoriasis. Normalization of corneocyte desquamation and the incorporation of agents that promote desquamation to reduce hyperkeratosis are also regarded as key factors in psoriasis management. Based on results reported by the study patients, the evaluated ceramide/keratolytic-containing cream and cleanser both yielded a high level of patient acceptance regarding improvement in skin characteristics in patients with psoriasis, including when used as a combination adjunctive regimen.

Split thickness skin graft in active psoriasis in patient with clear cell variant squamous cell carcinoma.

Scupham L, Ingle A. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Sep 16;12(9).

The case report discusses split thickness skin grafting in a patient with active psoriasis. This also reports a case of a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma.

Epicardial Adipose Tissue Inflammation Can Cause the Distinctive Pattern of Cardiovascular Disorders Seen in Psoriasis.

Packer M. Am J Med. 2019 Sep 11.

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disorder that can target adipose tissue; the resulting adipocyte dysfunction is manifest clinically as the metabolic syndrome, which is present in ≈20-40% of patients. Epicardial adipose tissue inflammation is likely responsible for a distinctive pattern of cardiovascular disorders, consisting of: accelerated coronary atherosclerosis leading to myocardial infarction, atrial myopathy leading to atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic stroke, and ventricular myopathy leading to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. If cardiovascular inflammation drives these risks, then treatments that focus on blood pressure, lipids and glucose will not ameliorate the burden of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis, especially in those who are young and have severe inflammation. Instead, interventions that alleviate systemic and adipose tissue inflammation may not only minimize the risks of atrial fibrillation and heart failure, but may also have favorable effects on the severity of psoriasis. Viewed from this perspective, the known link between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease is not related to the influence of the individual diagnostic components of the metabolic syndrome.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound can improve referrals from dermatology to rheumatology for patients with psoriasis.

Solmaz D, Bakirci S, Al Onazi A, Al Osaimi N, Fahim S, Aydin SZ. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Sep 10.

Psoriasis affects 1-3% of the population and up to 1/3 of psoriasis patients have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Non-specific musculoskeletal complaints are even higher, being around 50%. Detecting early signs of PsA and early treatments are crucial to improve the outcomes to prevent progressive, damaging arthritis. Due to the high frequency of non-specific pain in psoriasis, it is not possible for every psoriasis patient with joint pain to be assessed by a rheumato

Role of the Nervous System in Psoriasis

1. Amanat M, Salehi M, Rezaei N. Neurological and psychiatric disorders in psoriasis. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:805-813.

2. Eberle FC, Brück J, Holstein J, et al. Recent advances in understanding psoriasis [published April 28, 2016]. F1000Res. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7927.1.

3. Lee EB, Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, et al. Clearance of psoriasis after ischemic stroke. Cutis. 2019;103:74-76.

4. Zhu TH, Nakamura M, Farahnik B, et al. The role of the nervous system in the pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review of cases of psoriasis remission or improvement following denervation injury. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:257-263.

5. Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. Neuroimmunologic aspects of psoriasis. Cutis. 2000;66:357-362.