User login

No ‘one size fits all’ approach to managing severe pediatric psoriasis

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SPD 2019

Psoriasis Journal Scan: August 2019

Verrucous psoriasis: A rare variant of psoriasis masquerading as verrucous carcinoma.

Garvie K, McGinley Simpson M, Logemann N, Lackey J. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Aug 5;5(8):723-725.

Verrucous psoriasis is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hyperkeratotic, papillomatous plaques that clinically resemble verrucous carcinoma in lesion appearance and distribution. It is amenable to medical treatments. Conversely, verrucous carcinoma, a rare subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, is treated with surgical excision. Histologically, they may be difficult to differentiate. This case report presents a patient with verrucous psoriasis of the heal that was initially diagnosed as verrucous carcinoma and excised.

Re-Categorization of Psoriasis Severity: Delphi Consensus from the International Psoriasis Council.

Strober B, Ryan C, van de Kerkhof P, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 16.

This consensus statement on the classification of psoriasis severity preferentially ranked seven severity definitions. This most preferred statement rejects the mild, moderate and severe categories in favor of a dichotomous definition: Psoriasis patients should be classified as either candidates for topical therapy or candidates for systemic therapy; the latter are patients who meet at least one of the following criteria: 1) BSA > 10%, 2) Disease involving special areas, 3) Failure of topical therapy.

Gluten intake and risk of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis among US women.

Drucker AM, Qureshi AA, Thompson JM, Li T, Cho E. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 9.

Associations between gluten intake and psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis are poorly understood. Gluten content of participants' diet was calculated every four years using food frequency questionnaires. Disease outcomes were assessed by self-report and subsequently validated.

Psoriasis and Mortality in the US: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Semenov YR, Herbosa CM, Rogers AT, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 12.

In this retrospective population-based cohort study of adults and adolescents > 10 years (n=13,031) who participated in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (2003-2006; 2009-2010), psoriasis was present in 2.7% of the study population. Over an average 52.3 months median follow-up, psoriasis was significantly associated with increased mortality risk. This relationship is partially mediated by an increased prevalence of cardiovascular, infectious, and neoplastic disorders seen among psoriatics.

Ostraceous Psoriasis Presenting as Koebner Phenomenon in a Tattoo.

Reinhart J, Willett M, Gibbs N. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Aug 1;18(8):825-826.

Psoriasis ostracea is defined as having pronounced adherent scales resembling an oyster shell. Many ostraceous cases occur as generalized outbreaks in patients with long-standing history of psoriasis. Rarely does this variant occur as a direct flare from a cutaneous insult. In these situations, when a pre-existing dermatosis appears in response to a traumatic insult to skin, the process is referred to as the Koebner phenomenon. In addition to lichen planus and vitiligo, psoriasis is a commonly known condition that can present as a Koebner reaction. In this atypical case, the authors present a 21-year-old male with remarkable ostraceous psoriatic lesions precipitated by an upper arm tattoo, demonstrating the Koebner phenomenon.

Verrucous psoriasis: A rare variant of psoriasis masquerading as verrucous carcinoma.

Garvie K, McGinley Simpson M, Logemann N, Lackey J. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Aug 5;5(8):723-725.

Verrucous psoriasis is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hyperkeratotic, papillomatous plaques that clinically resemble verrucous carcinoma in lesion appearance and distribution. It is amenable to medical treatments. Conversely, verrucous carcinoma, a rare subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, is treated with surgical excision. Histologically, they may be difficult to differentiate. This case report presents a patient with verrucous psoriasis of the heal that was initially diagnosed as verrucous carcinoma and excised.

Re-Categorization of Psoriasis Severity: Delphi Consensus from the International Psoriasis Council.

Strober B, Ryan C, van de Kerkhof P, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 16.

This consensus statement on the classification of psoriasis severity preferentially ranked seven severity definitions. This most preferred statement rejects the mild, moderate and severe categories in favor of a dichotomous definition: Psoriasis patients should be classified as either candidates for topical therapy or candidates for systemic therapy; the latter are patients who meet at least one of the following criteria: 1) BSA > 10%, 2) Disease involving special areas, 3) Failure of topical therapy.

Gluten intake and risk of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis among US women.

Drucker AM, Qureshi AA, Thompson JM, Li T, Cho E. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 9.

Associations between gluten intake and psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis are poorly understood. Gluten content of participants' diet was calculated every four years using food frequency questionnaires. Disease outcomes were assessed by self-report and subsequently validated.

Psoriasis and Mortality in the US: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Semenov YR, Herbosa CM, Rogers AT, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 12.

In this retrospective population-based cohort study of adults and adolescents > 10 years (n=13,031) who participated in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (2003-2006; 2009-2010), psoriasis was present in 2.7% of the study population. Over an average 52.3 months median follow-up, psoriasis was significantly associated with increased mortality risk. This relationship is partially mediated by an increased prevalence of cardiovascular, infectious, and neoplastic disorders seen among psoriatics.

Ostraceous Psoriasis Presenting as Koebner Phenomenon in a Tattoo.

Reinhart J, Willett M, Gibbs N. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Aug 1;18(8):825-826.

Psoriasis ostracea is defined as having pronounced adherent scales resembling an oyster shell. Many ostraceous cases occur as generalized outbreaks in patients with long-standing history of psoriasis. Rarely does this variant occur as a direct flare from a cutaneous insult. In these situations, when a pre-existing dermatosis appears in response to a traumatic insult to skin, the process is referred to as the Koebner phenomenon. In addition to lichen planus and vitiligo, psoriasis is a commonly known condition that can present as a Koebner reaction. In this atypical case, the authors present a 21-year-old male with remarkable ostraceous psoriatic lesions precipitated by an upper arm tattoo, demonstrating the Koebner phenomenon.

Verrucous psoriasis: A rare variant of psoriasis masquerading as verrucous carcinoma.

Garvie K, McGinley Simpson M, Logemann N, Lackey J. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Aug 5;5(8):723-725.

Verrucous psoriasis is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hyperkeratotic, papillomatous plaques that clinically resemble verrucous carcinoma in lesion appearance and distribution. It is amenable to medical treatments. Conversely, verrucous carcinoma, a rare subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, is treated with surgical excision. Histologically, they may be difficult to differentiate. This case report presents a patient with verrucous psoriasis of the heal that was initially diagnosed as verrucous carcinoma and excised.

Re-Categorization of Psoriasis Severity: Delphi Consensus from the International Psoriasis Council.

Strober B, Ryan C, van de Kerkhof P, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 16.

This consensus statement on the classification of psoriasis severity preferentially ranked seven severity definitions. This most preferred statement rejects the mild, moderate and severe categories in favor of a dichotomous definition: Psoriasis patients should be classified as either candidates for topical therapy or candidates for systemic therapy; the latter are patients who meet at least one of the following criteria: 1) BSA > 10%, 2) Disease involving special areas, 3) Failure of topical therapy.

Gluten intake and risk of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis among US women.

Drucker AM, Qureshi AA, Thompson JM, Li T, Cho E. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 9.

Associations between gluten intake and psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and atopic dermatitis are poorly understood. Gluten content of participants' diet was calculated every four years using food frequency questionnaires. Disease outcomes were assessed by self-report and subsequently validated.

Psoriasis and Mortality in the US: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Semenov YR, Herbosa CM, Rogers AT, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Aug 12.

In this retrospective population-based cohort study of adults and adolescents > 10 years (n=13,031) who participated in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (2003-2006; 2009-2010), psoriasis was present in 2.7% of the study population. Over an average 52.3 months median follow-up, psoriasis was significantly associated with increased mortality risk. This relationship is partially mediated by an increased prevalence of cardiovascular, infectious, and neoplastic disorders seen among psoriatics.

Ostraceous Psoriasis Presenting as Koebner Phenomenon in a Tattoo.

Reinhart J, Willett M, Gibbs N. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Aug 1;18(8):825-826.

Psoriasis ostracea is defined as having pronounced adherent scales resembling an oyster shell. Many ostraceous cases occur as generalized outbreaks in patients with long-standing history of psoriasis. Rarely does this variant occur as a direct flare from a cutaneous insult. In these situations, when a pre-existing dermatosis appears in response to a traumatic insult to skin, the process is referred to as the Koebner phenomenon. In addition to lichen planus and vitiligo, psoriasis is a commonly known condition that can present as a Koebner reaction. In this atypical case, the authors present a 21-year-old male with remarkable ostraceous psoriatic lesions precipitated by an upper arm tattoo, demonstrating the Koebner phenomenon.

Considerations for Psoriasis in Pregnancy

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Psoriasis patients on biologics show improved heart health

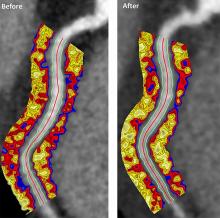

Biologics improved coronary inflammation as well as psoriasis symptoms, according to data from the perivascular fat attenuation index in 134 adults identified using coronary CT angiography.

“The perivascular fat attenuation index [FAI] is a [CT]-based, novel, noninvasive imaging technique that allows for direct visualization and quantification of coronary inflammation using differential mapping of attenuation gradients in pericoronary fat,” wrote Youssef A. Elnabawi, MD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and colleagues. Biologics have been associated with reduced noncalcified coronary plaques in psoriasis patients, which suggests possible reduction in coronary inflammation as well.

In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, the researchers analyzed data from 134 adults with moderate to severe psoriasis who received no biologic therapy for at least 3 months before starting the study. Of these, 52 chose not to receive biologics, and served as controls while being treated with topical or light therapies. The participants are part of the Psoriasis Atherosclerosis Cardiometabolic Initiative, an ongoing, prospective cohort study. The average age of the patients was 51 years, and 63% were male.

The 82 patients given biologics received anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha, anti–interleukin-12/23, or anti-IL-17 for 1 year. Overall, patients on biologics showed a significant decrease in FAI from a median of –71.22 Hounsfield units (HU) at baseline to a median of –76.06 at 1 year. These patients also showed significant improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, from a median of 7.7 at baseline to a median of 3.2 at 1 year. The control patients not on biologics showed no significant changes in FAI, with a median of –71.98 HU at baseline and –72.66 HU at 1 year.

The changes were consistent among the various biologics used, and The median FAI for patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha changed from –71.25 at baseline to –75.49 at 1 year; median FAI for both IL-12/23 and anti-IL-17 treatment groups changed from –71.18 HU at baseline to –76.92 at 1 year.

In addition, only patients treated with biologics showed a significant reduction in median C-reactive protein levels from baseline (2.2 mg/L vs. 1.3 mg/L). The changes in FAI were not associated with the presence of coronary plaques, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design, small size, and lack of data on cardiovascular endpoints. “Future studies will be needed to explore whether the residual CV risk detected by perivascular FAI can be attenuated using targeted anti-inflammatory interventions,” they wrote.

However, the results suggest that biologics impact coronary vasculature at the microenvironmental level, and that FAI can be a noninvasive, cost-effective way to stratify patients at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, the researchers noted.

“We believe that the strength of perivascular FAI in risk stratifying patients with increased coronary inflammation will allow for better identification of patients at increased risk of future myocardial events that are not captured by traditional CV risk factors,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, several research foundations, Elsevier, Colgate-Palmolive, and Genentech. Dr. Elnabawi had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with multiple companies. One coauthor disclosed a pending and licensed patent to a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification based on the CT attenuation of perivascular tissue (OxScore) and a pending and licensed patent to perivascular texture index.

SOURCE: Elnabawi YA et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2589.

Biologics improved coronary inflammation as well as psoriasis symptoms, according to data from the perivascular fat attenuation index in 134 adults identified using coronary CT angiography.

“The perivascular fat attenuation index [FAI] is a [CT]-based, novel, noninvasive imaging technique that allows for direct visualization and quantification of coronary inflammation using differential mapping of attenuation gradients in pericoronary fat,” wrote Youssef A. Elnabawi, MD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and colleagues. Biologics have been associated with reduced noncalcified coronary plaques in psoriasis patients, which suggests possible reduction in coronary inflammation as well.

In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, the researchers analyzed data from 134 adults with moderate to severe psoriasis who received no biologic therapy for at least 3 months before starting the study. Of these, 52 chose not to receive biologics, and served as controls while being treated with topical or light therapies. The participants are part of the Psoriasis Atherosclerosis Cardiometabolic Initiative, an ongoing, prospective cohort study. The average age of the patients was 51 years, and 63% were male.

The 82 patients given biologics received anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha, anti–interleukin-12/23, or anti-IL-17 for 1 year. Overall, patients on biologics showed a significant decrease in FAI from a median of –71.22 Hounsfield units (HU) at baseline to a median of –76.06 at 1 year. These patients also showed significant improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, from a median of 7.7 at baseline to a median of 3.2 at 1 year. The control patients not on biologics showed no significant changes in FAI, with a median of –71.98 HU at baseline and –72.66 HU at 1 year.

The changes were consistent among the various biologics used, and The median FAI for patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha changed from –71.25 at baseline to –75.49 at 1 year; median FAI for both IL-12/23 and anti-IL-17 treatment groups changed from –71.18 HU at baseline to –76.92 at 1 year.

In addition, only patients treated with biologics showed a significant reduction in median C-reactive protein levels from baseline (2.2 mg/L vs. 1.3 mg/L). The changes in FAI were not associated with the presence of coronary plaques, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design, small size, and lack of data on cardiovascular endpoints. “Future studies will be needed to explore whether the residual CV risk detected by perivascular FAI can be attenuated using targeted anti-inflammatory interventions,” they wrote.

However, the results suggest that biologics impact coronary vasculature at the microenvironmental level, and that FAI can be a noninvasive, cost-effective way to stratify patients at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, the researchers noted.

“We believe that the strength of perivascular FAI in risk stratifying patients with increased coronary inflammation will allow for better identification of patients at increased risk of future myocardial events that are not captured by traditional CV risk factors,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, several research foundations, Elsevier, Colgate-Palmolive, and Genentech. Dr. Elnabawi had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with multiple companies. One coauthor disclosed a pending and licensed patent to a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification based on the CT attenuation of perivascular tissue (OxScore) and a pending and licensed patent to perivascular texture index.

SOURCE: Elnabawi YA et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2589.

Biologics improved coronary inflammation as well as psoriasis symptoms, according to data from the perivascular fat attenuation index in 134 adults identified using coronary CT angiography.

“The perivascular fat attenuation index [FAI] is a [CT]-based, novel, noninvasive imaging technique that allows for direct visualization and quantification of coronary inflammation using differential mapping of attenuation gradients in pericoronary fat,” wrote Youssef A. Elnabawi, MD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and colleagues. Biologics have been associated with reduced noncalcified coronary plaques in psoriasis patients, which suggests possible reduction in coronary inflammation as well.

In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, the researchers analyzed data from 134 adults with moderate to severe psoriasis who received no biologic therapy for at least 3 months before starting the study. Of these, 52 chose not to receive biologics, and served as controls while being treated with topical or light therapies. The participants are part of the Psoriasis Atherosclerosis Cardiometabolic Initiative, an ongoing, prospective cohort study. The average age of the patients was 51 years, and 63% were male.

The 82 patients given biologics received anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha, anti–interleukin-12/23, or anti-IL-17 for 1 year. Overall, patients on biologics showed a significant decrease in FAI from a median of –71.22 Hounsfield units (HU) at baseline to a median of –76.06 at 1 year. These patients also showed significant improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, from a median of 7.7 at baseline to a median of 3.2 at 1 year. The control patients not on biologics showed no significant changes in FAI, with a median of –71.98 HU at baseline and –72.66 HU at 1 year.

The changes were consistent among the various biologics used, and The median FAI for patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha changed from –71.25 at baseline to –75.49 at 1 year; median FAI for both IL-12/23 and anti-IL-17 treatment groups changed from –71.18 HU at baseline to –76.92 at 1 year.

In addition, only patients treated with biologics showed a significant reduction in median C-reactive protein levels from baseline (2.2 mg/L vs. 1.3 mg/L). The changes in FAI were not associated with the presence of coronary plaques, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design, small size, and lack of data on cardiovascular endpoints. “Future studies will be needed to explore whether the residual CV risk detected by perivascular FAI can be attenuated using targeted anti-inflammatory interventions,” they wrote.

However, the results suggest that biologics impact coronary vasculature at the microenvironmental level, and that FAI can be a noninvasive, cost-effective way to stratify patients at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, the researchers noted.

“We believe that the strength of perivascular FAI in risk stratifying patients with increased coronary inflammation will allow for better identification of patients at increased risk of future myocardial events that are not captured by traditional CV risk factors,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, several research foundations, Elsevier, Colgate-Palmolive, and Genentech. Dr. Elnabawi had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with multiple companies. One coauthor disclosed a pending and licensed patent to a novel tool for cardiovascular risk stratification based on the CT attenuation of perivascular tissue (OxScore) and a pending and licensed patent to perivascular texture index.

SOURCE: Elnabawi YA et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jul 31. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2589.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Did You Know? Psoriasis and cardiovascular disease

Psoriasis Journal Scan: July 2019

Facial involvement and the severity of psoriasis.

Passos AN, de A Rêgo VRP, Duarte GV, Santos E Miranda RC, de O Rocha B, de F S P de Oliveira M. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Jul 26.

The aim of this cross-sectional study is to compare the severity of psoriasis, measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), in patients with and without facial lesions.

Genital Psoriasis: Impact on Quality of Life and Treatment Options.

Kelly A, Ryan C. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 Jul 16

Psoriasis involving the genital skin occurs in up to two-thirds of psoriasis patients but is often overlooked by physicians. Furthermore, psoriasis objective and subjective severity indexes for common plaque psoriasis often neglect the impact this small area of psoriasis can have on a patient. It can have a significant impact on patients' psychosocial function due to intrusive physical symptoms such as genital itch and pain, and a detrimental impact on sexual health and impaired relationships.

Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis.

Ko SH, Chi CC, Yeh ML, Wang SH, Tsai YS, Hsu MY. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 16

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of lifestyle changes for psoriasis, including weight reduction, alcohol abstinence, smoking cessation, dietary modification, exercise, and other lifestyle change interventions. Dietary intervention may reduce the severity of psoriasis (low-quality evidence) and probably improves quality of life and reduces BMI (moderate-quality evidence) in obese people when compared with usual care, while combined dietary intervention and exercise programme probably improves psoriasis severity and BMI when compared with information only (moderate-quality evidence).

The Incidence Rates and Risk Factors of Parkinson's Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study.

Lee JH, Han K, Gee HY. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 11.

This was a nationwide population-based cohort study to determine the incidence rates and risk factors of Parkinson's disease in patients with psoriasis. The psoriasis group showed a significantly increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease. The risk of Parkinson's disease was significantly high among the psoriasis patients who were not receiving systemic therapy and was low among the psoriasis patients on systemic therapy.

Psoriasis-associated itch: etiology, assessment, impact, and management.

Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, Wu JJ. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019 Jul 5:1-9.

Pruritus, a very broad, subjective, and complex symptom, troubles the majority of patients with psoriasis. However, the subjective and multidimensional nature of the symptom renders it challenging for patients to appropriately communicate their experiences with itch to providers. This review explores current perspectives regarding the underlying mechanisms, assessment tools, burden, and treatment modalities for psoriatic pruritus. It emphasizes the significance of incorporating a standardized, thorough, and verified metric that incorporates severity, distribution, and character of pruritus as well as its effects on various aspects of quality of life. It also underscores the importance of continued research to fully understand the pathogenesis of psoriatic itch for establishment of novel, targeted therapeutics.

Facial involvement and the severity of psoriasis.

Passos AN, de A Rêgo VRP, Duarte GV, Santos E Miranda RC, de O Rocha B, de F S P de Oliveira M. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Jul 26.

The aim of this cross-sectional study is to compare the severity of psoriasis, measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), in patients with and without facial lesions.

Genital Psoriasis: Impact on Quality of Life and Treatment Options.

Kelly A, Ryan C. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 Jul 16

Psoriasis involving the genital skin occurs in up to two-thirds of psoriasis patients but is often overlooked by physicians. Furthermore, psoriasis objective and subjective severity indexes for common plaque psoriasis often neglect the impact this small area of psoriasis can have on a patient. It can have a significant impact on patients' psychosocial function due to intrusive physical symptoms such as genital itch and pain, and a detrimental impact on sexual health and impaired relationships.

Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis.

Ko SH, Chi CC, Yeh ML, Wang SH, Tsai YS, Hsu MY. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 16

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of lifestyle changes for psoriasis, including weight reduction, alcohol abstinence, smoking cessation, dietary modification, exercise, and other lifestyle change interventions. Dietary intervention may reduce the severity of psoriasis (low-quality evidence) and probably improves quality of life and reduces BMI (moderate-quality evidence) in obese people when compared with usual care, while combined dietary intervention and exercise programme probably improves psoriasis severity and BMI when compared with information only (moderate-quality evidence).

The Incidence Rates and Risk Factors of Parkinson's Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study.

Lee JH, Han K, Gee HY. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 11.

This was a nationwide population-based cohort study to determine the incidence rates and risk factors of Parkinson's disease in patients with psoriasis. The psoriasis group showed a significantly increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease. The risk of Parkinson's disease was significantly high among the psoriasis patients who were not receiving systemic therapy and was low among the psoriasis patients on systemic therapy.

Psoriasis-associated itch: etiology, assessment, impact, and management.

Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, Wu JJ. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019 Jul 5:1-9.

Pruritus, a very broad, subjective, and complex symptom, troubles the majority of patients with psoriasis. However, the subjective and multidimensional nature of the symptom renders it challenging for patients to appropriately communicate their experiences with itch to providers. This review explores current perspectives regarding the underlying mechanisms, assessment tools, burden, and treatment modalities for psoriatic pruritus. It emphasizes the significance of incorporating a standardized, thorough, and verified metric that incorporates severity, distribution, and character of pruritus as well as its effects on various aspects of quality of life. It also underscores the importance of continued research to fully understand the pathogenesis of psoriatic itch for establishment of novel, targeted therapeutics.

Facial involvement and the severity of psoriasis.

Passos AN, de A Rêgo VRP, Duarte GV, Santos E Miranda RC, de O Rocha B, de F S P de Oliveira M. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Jul 26.

The aim of this cross-sectional study is to compare the severity of psoriasis, measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), in patients with and without facial lesions.

Genital Psoriasis: Impact on Quality of Life and Treatment Options.

Kelly A, Ryan C. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 Jul 16

Psoriasis involving the genital skin occurs in up to two-thirds of psoriasis patients but is often overlooked by physicians. Furthermore, psoriasis objective and subjective severity indexes for common plaque psoriasis often neglect the impact this small area of psoriasis can have on a patient. It can have a significant impact on patients' psychosocial function due to intrusive physical symptoms such as genital itch and pain, and a detrimental impact on sexual health and impaired relationships.

Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis.

Ko SH, Chi CC, Yeh ML, Wang SH, Tsai YS, Hsu MY. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jul 16

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of lifestyle changes for psoriasis, including weight reduction, alcohol abstinence, smoking cessation, dietary modification, exercise, and other lifestyle change interventions. Dietary intervention may reduce the severity of psoriasis (low-quality evidence) and probably improves quality of life and reduces BMI (moderate-quality evidence) in obese people when compared with usual care, while combined dietary intervention and exercise programme probably improves psoriasis severity and BMI when compared with information only (moderate-quality evidence).

The Incidence Rates and Risk Factors of Parkinson's Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study.

Lee JH, Han K, Gee HY. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 11.

This was a nationwide population-based cohort study to determine the incidence rates and risk factors of Parkinson's disease in patients with psoriasis. The psoriasis group showed a significantly increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease. The risk of Parkinson's disease was significantly high among the psoriasis patients who were not receiving systemic therapy and was low among the psoriasis patients on systemic therapy.

Psoriasis-associated itch: etiology, assessment, impact, and management.

Pithadia DJ, Reynolds KA, Lee EB, Wu JJ. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019 Jul 5:1-9.

Pruritus, a very broad, subjective, and complex symptom, troubles the majority of patients with psoriasis. However, the subjective and multidimensional nature of the symptom renders it challenging for patients to appropriately communicate their experiences with itch to providers. This review explores current perspectives regarding the underlying mechanisms, assessment tools, burden, and treatment modalities for psoriatic pruritus. It emphasizes the significance of incorporating a standardized, thorough, and verified metric that incorporates severity, distribution, and character of pruritus as well as its effects on various aspects of quality of life. It also underscores the importance of continued research to fully understand the pathogenesis of psoriatic itch for establishment of novel, targeted therapeutics.

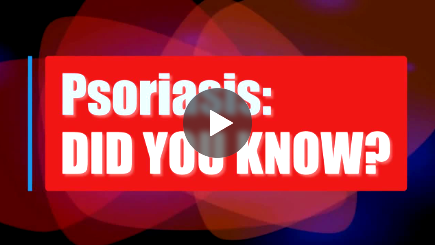

AAD, NPF update use of phototherapy for psoriasis

, according to updated guidelines issued jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“Phototherapy serves as a reasonable and effective treatment option for patients requiring more than topical medications and/or those wishing to avoid systemic medications or simply seeking an adjunct to a failing regimen,” wrote working group cochair Craig A. Elmets, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and coauthors.

The guidelines, which focus on phototherapy for adults with psoriasis, join a multipart series on psoriasis being published this year in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The working group used an evidence-based model to examine efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of the following modalities: narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB); broadband ultraviolet B (BB-UVB); targeted phototherapy using excimer laser and excimer lamp; psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, including topical, oral, and bath PUVA; photodynamic therapy (PDT), grenz ray therapy, climatotherapy; visible light therapy; Goeckerman therapy; and pulsed dye laser/intense pulsed light.

NB-UVB, which can be used to treat generalized plaque psoriasis, refers to wavelengths of 311-313 nm. The recommended treatment is two or three times a week, with a starting dose based on skin phenotype or minimal erythema dose. Although oral PUVA has shown higher clearance rates, compared with NB-UVB, NB-UVB has demonstrated fewer side effects. NB-UVB also has shown effectiveness for psoriasis in combination with medications including oral retinoids, “particularly useful in patients at increased risk for skin cancer,” the working group wrote. Genital shielding and eye protection are recommended during all phototherapy sessions to reduce the risk of cancer and cataracts, they emphasized.

BB-UVB, an older version of NB-UVB, is still effective for generalized plaque psoriasis as monotherapy, but evidence does not support additional benefit in combination with other treatments, and overall BB-UVB is less effective than either NB-UVB or oral PUVA, the working group said.

For treatment of localized psoriatic lesions, some evidence supports the ability of targeted UVB therapy to improve lesions in fewer treatments and at a lower cumulative dose, compared with nontargeted phototherapy, for palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis. Excimer lasers also have shown effectiveness against scalp psoriasis, the working group noted. However, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend the excimer laser rather than topical PUVA for treatment of localized plaque psoriasis,” they said.

PUVA treatments are available as topical creams, or they can be taken orally, or mixed with bath water. All forms of PUVA include psoralens, photosensitizing agents that prepare target cells for the effects of UVA light. Topical PUVA has demonstrated particular effectiveness for palmoplantar psoriasis, the working group noted, but there is a risk of phototoxicity, so it has become less popular, they added. Similarly, evidence supports effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA, but all forms are used less frequently because of the increased availability of NB-UVB phototherapy, they said.

PDT is primarily used to destroy premalignant or malignant cells, and in theory “PDT-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes could lead to reductions in inflammatory cytokines and, in turn, to improvement of psoriasis,” the working group noted. However, “clinical studies have failed to find significant benefit” of PDT using either 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) or methyl aminolevulinic acid (MAL) for psoriasis, or any significant benefits of MAL-PDT for nail psoriasis.

The grenz ray is an effective, but rarely used treatment in which 75% of long-wavelength ionizing radiation is absorbed by the first 1 mm of skin and 95% is absorbed within the first 3 mm of skin to protect the deeper tissues from radiation. Although more alternatives are available, grenz rays can be used for psoriasis patients unable to tolerate UV therapy, according to the working group.

Climatotherapy involves temporary or permanent relocation of the patient to a part of the world with a climate that could be favorable for psoriasis because of the unique effects of environmental factors in those areas. The evidence to support climatotherapy is both subjective and objective, but considered safe.

Visible light has been associated with improvement in erythema in psoriasis, with hyperpigmentation as the only notable side effect based on the evidence reviewed. However, the working group found the current evidence insufficient to recommend the use of intense pulsed light for treating psoriasis.

Goeckerman therapy, a method that combines coal tar and UVB phototherapy, has shown safety and effectiveness for patients with recalcitrant or severe psoriasis, and remains a recommended treatment, according to the working group research. However, this method is underused, especially in the United States, because of the messiness of the application, challenge of insurance reimbursement, and investment of time for outpatient care, the work group noted.

Pulsed dye laser treatment is effective for nail psoriasis, and reported adverse effects have been mild, according to the working group.

Overall, the guidelines emphasize that quality of life and disease severity should be considered and discussed with patients along with efficacy and safety information so they can make informed decisions about adding phototherapy to a current regimen or switching among modalities.

The guidelines have no funding sources. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including manufacturers of psoriasis products; however, a minimum of 51% of the work group had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose, in accordance with AAD policy. Work group members with potential conflicts recused themselves from discussion and drafting of recommendations in the relevant topic areas. Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, is the other cochair of the work group.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042.

, according to updated guidelines issued jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“Phototherapy serves as a reasonable and effective treatment option for patients requiring more than topical medications and/or those wishing to avoid systemic medications or simply seeking an adjunct to a failing regimen,” wrote working group cochair Craig A. Elmets, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and coauthors.

The guidelines, which focus on phototherapy for adults with psoriasis, join a multipart series on psoriasis being published this year in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The working group used an evidence-based model to examine efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of the following modalities: narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB); broadband ultraviolet B (BB-UVB); targeted phototherapy using excimer laser and excimer lamp; psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, including topical, oral, and bath PUVA; photodynamic therapy (PDT), grenz ray therapy, climatotherapy; visible light therapy; Goeckerman therapy; and pulsed dye laser/intense pulsed light.

NB-UVB, which can be used to treat generalized plaque psoriasis, refers to wavelengths of 311-313 nm. The recommended treatment is two or three times a week, with a starting dose based on skin phenotype or minimal erythema dose. Although oral PUVA has shown higher clearance rates, compared with NB-UVB, NB-UVB has demonstrated fewer side effects. NB-UVB also has shown effectiveness for psoriasis in combination with medications including oral retinoids, “particularly useful in patients at increased risk for skin cancer,” the working group wrote. Genital shielding and eye protection are recommended during all phototherapy sessions to reduce the risk of cancer and cataracts, they emphasized.

BB-UVB, an older version of NB-UVB, is still effective for generalized plaque psoriasis as monotherapy, but evidence does not support additional benefit in combination with other treatments, and overall BB-UVB is less effective than either NB-UVB or oral PUVA, the working group said.

For treatment of localized psoriatic lesions, some evidence supports the ability of targeted UVB therapy to improve lesions in fewer treatments and at a lower cumulative dose, compared with nontargeted phototherapy, for palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis. Excimer lasers also have shown effectiveness against scalp psoriasis, the working group noted. However, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend the excimer laser rather than topical PUVA for treatment of localized plaque psoriasis,” they said.

PUVA treatments are available as topical creams, or they can be taken orally, or mixed with bath water. All forms of PUVA include psoralens, photosensitizing agents that prepare target cells for the effects of UVA light. Topical PUVA has demonstrated particular effectiveness for palmoplantar psoriasis, the working group noted, but there is a risk of phototoxicity, so it has become less popular, they added. Similarly, evidence supports effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA, but all forms are used less frequently because of the increased availability of NB-UVB phototherapy, they said.

PDT is primarily used to destroy premalignant or malignant cells, and in theory “PDT-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes could lead to reductions in inflammatory cytokines and, in turn, to improvement of psoriasis,” the working group noted. However, “clinical studies have failed to find significant benefit” of PDT using either 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) or methyl aminolevulinic acid (MAL) for psoriasis, or any significant benefits of MAL-PDT for nail psoriasis.

The grenz ray is an effective, but rarely used treatment in which 75% of long-wavelength ionizing radiation is absorbed by the first 1 mm of skin and 95% is absorbed within the first 3 mm of skin to protect the deeper tissues from radiation. Although more alternatives are available, grenz rays can be used for psoriasis patients unable to tolerate UV therapy, according to the working group.

Climatotherapy involves temporary or permanent relocation of the patient to a part of the world with a climate that could be favorable for psoriasis because of the unique effects of environmental factors in those areas. The evidence to support climatotherapy is both subjective and objective, but considered safe.

Visible light has been associated with improvement in erythema in psoriasis, with hyperpigmentation as the only notable side effect based on the evidence reviewed. However, the working group found the current evidence insufficient to recommend the use of intense pulsed light for treating psoriasis.

Goeckerman therapy, a method that combines coal tar and UVB phototherapy, has shown safety and effectiveness for patients with recalcitrant or severe psoriasis, and remains a recommended treatment, according to the working group research. However, this method is underused, especially in the United States, because of the messiness of the application, challenge of insurance reimbursement, and investment of time for outpatient care, the work group noted.

Pulsed dye laser treatment is effective for nail psoriasis, and reported adverse effects have been mild, according to the working group.

Overall, the guidelines emphasize that quality of life and disease severity should be considered and discussed with patients along with efficacy and safety information so they can make informed decisions about adding phototherapy to a current regimen or switching among modalities.

The guidelines have no funding sources. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including manufacturers of psoriasis products; however, a minimum of 51% of the work group had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose, in accordance with AAD policy. Work group members with potential conflicts recused themselves from discussion and drafting of recommendations in the relevant topic areas. Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, is the other cochair of the work group.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042.

, according to updated guidelines issued jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“Phototherapy serves as a reasonable and effective treatment option for patients requiring more than topical medications and/or those wishing to avoid systemic medications or simply seeking an adjunct to a failing regimen,” wrote working group cochair Craig A. Elmets, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and coauthors.

The guidelines, which focus on phototherapy for adults with psoriasis, join a multipart series on psoriasis being published this year in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The working group used an evidence-based model to examine efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of the following modalities: narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB); broadband ultraviolet B (BB-UVB); targeted phototherapy using excimer laser and excimer lamp; psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, including topical, oral, and bath PUVA; photodynamic therapy (PDT), grenz ray therapy, climatotherapy; visible light therapy; Goeckerman therapy; and pulsed dye laser/intense pulsed light.

NB-UVB, which can be used to treat generalized plaque psoriasis, refers to wavelengths of 311-313 nm. The recommended treatment is two or three times a week, with a starting dose based on skin phenotype or minimal erythema dose. Although oral PUVA has shown higher clearance rates, compared with NB-UVB, NB-UVB has demonstrated fewer side effects. NB-UVB also has shown effectiveness for psoriasis in combination with medications including oral retinoids, “particularly useful in patients at increased risk for skin cancer,” the working group wrote. Genital shielding and eye protection are recommended during all phototherapy sessions to reduce the risk of cancer and cataracts, they emphasized.

BB-UVB, an older version of NB-UVB, is still effective for generalized plaque psoriasis as monotherapy, but evidence does not support additional benefit in combination with other treatments, and overall BB-UVB is less effective than either NB-UVB or oral PUVA, the working group said.

For treatment of localized psoriatic lesions, some evidence supports the ability of targeted UVB therapy to improve lesions in fewer treatments and at a lower cumulative dose, compared with nontargeted phototherapy, for palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis. Excimer lasers also have shown effectiveness against scalp psoriasis, the working group noted. However, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend the excimer laser rather than topical PUVA for treatment of localized plaque psoriasis,” they said.

PUVA treatments are available as topical creams, or they can be taken orally, or mixed with bath water. All forms of PUVA include psoralens, photosensitizing agents that prepare target cells for the effects of UVA light. Topical PUVA has demonstrated particular effectiveness for palmoplantar psoriasis, the working group noted, but there is a risk of phototoxicity, so it has become less popular, they added. Similarly, evidence supports effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA, but all forms are used less frequently because of the increased availability of NB-UVB phototherapy, they said.

PDT is primarily used to destroy premalignant or malignant cells, and in theory “PDT-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes could lead to reductions in inflammatory cytokines and, in turn, to improvement of psoriasis,” the working group noted. However, “clinical studies have failed to find significant benefit” of PDT using either 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) or methyl aminolevulinic acid (MAL) for psoriasis, or any significant benefits of MAL-PDT for nail psoriasis.

The grenz ray is an effective, but rarely used treatment in which 75% of long-wavelength ionizing radiation is absorbed by the first 1 mm of skin and 95% is absorbed within the first 3 mm of skin to protect the deeper tissues from radiation. Although more alternatives are available, grenz rays can be used for psoriasis patients unable to tolerate UV therapy, according to the working group.

Climatotherapy involves temporary or permanent relocation of the patient to a part of the world with a climate that could be favorable for psoriasis because of the unique effects of environmental factors in those areas. The evidence to support climatotherapy is both subjective and objective, but considered safe.

Visible light has been associated with improvement in erythema in psoriasis, with hyperpigmentation as the only notable side effect based on the evidence reviewed. However, the working group found the current evidence insufficient to recommend the use of intense pulsed light for treating psoriasis.

Goeckerman therapy, a method that combines coal tar and UVB phototherapy, has shown safety and effectiveness for patients with recalcitrant or severe psoriasis, and remains a recommended treatment, according to the working group research. However, this method is underused, especially in the United States, because of the messiness of the application, challenge of insurance reimbursement, and investment of time for outpatient care, the work group noted.

Pulsed dye laser treatment is effective for nail psoriasis, and reported adverse effects have been mild, according to the working group.

Overall, the guidelines emphasize that quality of life and disease severity should be considered and discussed with patients along with efficacy and safety information so they can make informed decisions about adding phototherapy to a current regimen or switching among modalities.

The guidelines have no funding sources. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including manufacturers of psoriasis products; however, a minimum of 51% of the work group had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose, in accordance with AAD policy. Work group members with potential conflicts recused themselves from discussion and drafting of recommendations in the relevant topic areas. Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, is the other cochair of the work group.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Biologics for pediatric psoriasis don’t increase infection risk

AUSTIN, TEX. – Among children with psoriasis, there appears to be no strong evidence that biologic immunomodulating drugs increase the 6-month risk of serious infections, compared with systemic nonbiologics or phototherapy, according to results from the largest population-based study of its kind to date.

However, children with psoriasis face a 64% increased risk of infection, compared with risk-matched pediatric patients without the disease.