User login

Anti-TNFs help psoriatic arthritis patients get back to work

ROME – Anti–tumor necrosis factor agents have a slight edge over conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs when it comes to helping psoriatic arthritis patients who are having work issues, according to a large British observational study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Among 236 of 400 subjects working at baseline, presenteeism improved from 30% to 10% and productivity loss improved from 45% to 10% among patients who started taking anti-TNF (anti-tumor necrosis factor) agents. Gains were more modest when patients were started on DMARDs, with presenteeism improving from 30% to 20% and productivity loss from 40% to 25%. The difference in change of presenteeism between the two treatment groups became statistically significant at 2 weeks and remained so at 24 weeks.

“Work disability is a continuum,” said the presenting author, Dr. William Tillett of the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath (England). It starts with the normal situation then graduates from presenteeism, where the individual is sick but still attends the workplace, to absenteeism, where the individual is sick and no longer attends the place of work, and eventual unemployment, he explained. “This study suggests that work disability is reversible in the real-world setting,” he added.

The study is from the Long-term Outcomes in Psoriatic ArthritiS (LOPAS II) working group, a 2-year, multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study of work disability in psoriatic arthritis. The group has previously reported that unemployment in psoriatic arthritis is associated with older age, disease duration of 2-5 years, and worse physical function, but that employer awareness and helpfulness enabled patients to stay on the job. Higher levels of global and joint-specific disease activity and worse physical function were associated with greater levels of reporting to work sick (presenteeism) and productivity loss (Rheumatology 2015;54:157-62).

The latest study by Dr. Tillett and his team is a follow-up to see how treatment affects work performance. At baseline, before treatment with anti-TNF or DMARDs, the LOPAS II team of investigators found that 164 (41%) of their 400 subjects were unemployed. Unemployed patients tended to be older (median of 59 years vs. 49 years) and to have worse physical function (a median score of 1.4 on the Health Assessment Questionnaire vs. 1.0). Subsequent treatment with anti-TNFs or DMARDs didn’t change overall employment levels.

Patients who started on anti-TNFs tended to have longer disease duration (median of 11 vs. 5 years) and a greater median number of tender (16 vs. 11) and swollen (7 vs. 5) joints, but otherwise there were no significant differences in demographic or clinical measures between the two treatment groups.

Median scores on the Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) improved over 24 weeks from 53 to 14 among anti-TNF patients, which is considered a good response, but only improved from 39 to 30 in the DMARD group, which is considered a poor response. All of the findings were statistically significant.

The results revealed a “surprisingly poor clinical response to synthetic DMARDs on clinical outcomes … as opposed to good response amongst patients commenced on TNF inhibitors,” Dr. Tillett said in an interview. The improvement in work disability and disease activity seen also was greater and more rapid among those who started on anti-TNF rather than synthetic DMARD.

Dr. Tillett reported receiving grant/research support from AbbVie and speaker or advisory board fees from UCB, Pfizer, and AbbVie. The other authors said they have no disclosures.

ROME – Anti–tumor necrosis factor agents have a slight edge over conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs when it comes to helping psoriatic arthritis patients who are having work issues, according to a large British observational study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Among 236 of 400 subjects working at baseline, presenteeism improved from 30% to 10% and productivity loss improved from 45% to 10% among patients who started taking anti-TNF (anti-tumor necrosis factor) agents. Gains were more modest when patients were started on DMARDs, with presenteeism improving from 30% to 20% and productivity loss from 40% to 25%. The difference in change of presenteeism between the two treatment groups became statistically significant at 2 weeks and remained so at 24 weeks.

“Work disability is a continuum,” said the presenting author, Dr. William Tillett of the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath (England). It starts with the normal situation then graduates from presenteeism, where the individual is sick but still attends the workplace, to absenteeism, where the individual is sick and no longer attends the place of work, and eventual unemployment, he explained. “This study suggests that work disability is reversible in the real-world setting,” he added.

The study is from the Long-term Outcomes in Psoriatic ArthritiS (LOPAS II) working group, a 2-year, multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study of work disability in psoriatic arthritis. The group has previously reported that unemployment in psoriatic arthritis is associated with older age, disease duration of 2-5 years, and worse physical function, but that employer awareness and helpfulness enabled patients to stay on the job. Higher levels of global and joint-specific disease activity and worse physical function were associated with greater levels of reporting to work sick (presenteeism) and productivity loss (Rheumatology 2015;54:157-62).

The latest study by Dr. Tillett and his team is a follow-up to see how treatment affects work performance. At baseline, before treatment with anti-TNF or DMARDs, the LOPAS II team of investigators found that 164 (41%) of their 400 subjects were unemployed. Unemployed patients tended to be older (median of 59 years vs. 49 years) and to have worse physical function (a median score of 1.4 on the Health Assessment Questionnaire vs. 1.0). Subsequent treatment with anti-TNFs or DMARDs didn’t change overall employment levels.

Patients who started on anti-TNFs tended to have longer disease duration (median of 11 vs. 5 years) and a greater median number of tender (16 vs. 11) and swollen (7 vs. 5) joints, but otherwise there were no significant differences in demographic or clinical measures between the two treatment groups.

Median scores on the Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) improved over 24 weeks from 53 to 14 among anti-TNF patients, which is considered a good response, but only improved from 39 to 30 in the DMARD group, which is considered a poor response. All of the findings were statistically significant.

The results revealed a “surprisingly poor clinical response to synthetic DMARDs on clinical outcomes … as opposed to good response amongst patients commenced on TNF inhibitors,” Dr. Tillett said in an interview. The improvement in work disability and disease activity seen also was greater and more rapid among those who started on anti-TNF rather than synthetic DMARD.

Dr. Tillett reported receiving grant/research support from AbbVie and speaker or advisory board fees from UCB, Pfizer, and AbbVie. The other authors said they have no disclosures.

ROME – Anti–tumor necrosis factor agents have a slight edge over conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs when it comes to helping psoriatic arthritis patients who are having work issues, according to a large British observational study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Among 236 of 400 subjects working at baseline, presenteeism improved from 30% to 10% and productivity loss improved from 45% to 10% among patients who started taking anti-TNF (anti-tumor necrosis factor) agents. Gains were more modest when patients were started on DMARDs, with presenteeism improving from 30% to 20% and productivity loss from 40% to 25%. The difference in change of presenteeism between the two treatment groups became statistically significant at 2 weeks and remained so at 24 weeks.

“Work disability is a continuum,” said the presenting author, Dr. William Tillett of the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath (England). It starts with the normal situation then graduates from presenteeism, where the individual is sick but still attends the workplace, to absenteeism, where the individual is sick and no longer attends the place of work, and eventual unemployment, he explained. “This study suggests that work disability is reversible in the real-world setting,” he added.

The study is from the Long-term Outcomes in Psoriatic ArthritiS (LOPAS II) working group, a 2-year, multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study of work disability in psoriatic arthritis. The group has previously reported that unemployment in psoriatic arthritis is associated with older age, disease duration of 2-5 years, and worse physical function, but that employer awareness and helpfulness enabled patients to stay on the job. Higher levels of global and joint-specific disease activity and worse physical function were associated with greater levels of reporting to work sick (presenteeism) and productivity loss (Rheumatology 2015;54:157-62).

The latest study by Dr. Tillett and his team is a follow-up to see how treatment affects work performance. At baseline, before treatment with anti-TNF or DMARDs, the LOPAS II team of investigators found that 164 (41%) of their 400 subjects were unemployed. Unemployed patients tended to be older (median of 59 years vs. 49 years) and to have worse physical function (a median score of 1.4 on the Health Assessment Questionnaire vs. 1.0). Subsequent treatment with anti-TNFs or DMARDs didn’t change overall employment levels.

Patients who started on anti-TNFs tended to have longer disease duration (median of 11 vs. 5 years) and a greater median number of tender (16 vs. 11) and swollen (7 vs. 5) joints, but otherwise there were no significant differences in demographic or clinical measures between the two treatment groups.

Median scores on the Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) improved over 24 weeks from 53 to 14 among anti-TNF patients, which is considered a good response, but only improved from 39 to 30 in the DMARD group, which is considered a poor response. All of the findings were statistically significant.

The results revealed a “surprisingly poor clinical response to synthetic DMARDs on clinical outcomes … as opposed to good response amongst patients commenced on TNF inhibitors,” Dr. Tillett said in an interview. The improvement in work disability and disease activity seen also was greater and more rapid among those who started on anti-TNF rather than synthetic DMARD.

Dr. Tillett reported receiving grant/research support from AbbVie and speaker or advisory board fees from UCB, Pfizer, and AbbVie. The other authors said they have no disclosures.

AT THE EULAR 2015 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Work disability is a reversible outcome in psoriatic arthritis and improves significantly more with use of anti-TNF drugs than with synthetic DMARDs.

Major finding: Presenteeism improved from 30% to 10% and productivity loss improved from 45% to 10% among patients who started taking anti-TNF agents.

Data source: A 2-year, multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study of work disability in 400 patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Disclosures: Dr. Tillett reported receiving research support from AbbVie and speaker or advisory board fees from UCB, Pfizer, and Abbvie.

Fragile Drug Development Process

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

Fathers factor in psoriatic disease

Researchers have discovered further evidence of paternal transmission bias in psoriatic disease, according to a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

Significantly more individuals with a first-degree relative affected with psoriatic disease reported an affected father (57%), compared with an affected mother (43%). Self-reported family history was obtained from 849 Canadian adults who reported a first-degree relative affected with either cutaneous psoriasis without arthritis (PsC) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). A total of 532 (63%) reported an affected parent, and 23 probands reported that both parents were affected. The researchers found significantly more fathers with psoriatic disease than mothers: 289 (57%) of 509 discordant pairs vs. 220 (43%) of 509 discordant pairs, respectively (P = .003).

The paternal transmission bias did not reach statistical significance in PsC probands (P = .20), but the proportion of paternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (161 [75%] of 214 paternal transmissions) was significantly larger (P = .02) than maternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (103 [64%] of 161 maternal transmissions).

“If PsA is considered a more severe form of psoriatic disease than PsC alone, this finding suggests that there is a greater chance of an increase in disease severity when psoriatic disease is transmitted by an affected male compared to an affected female,” wrote the investigators, led by Remy A. Pollock of Toronto Western Hospital.

Read the full article here: (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 [doi:10.1002/acr.22625]).

Researchers have discovered further evidence of paternal transmission bias in psoriatic disease, according to a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

Significantly more individuals with a first-degree relative affected with psoriatic disease reported an affected father (57%), compared with an affected mother (43%). Self-reported family history was obtained from 849 Canadian adults who reported a first-degree relative affected with either cutaneous psoriasis without arthritis (PsC) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). A total of 532 (63%) reported an affected parent, and 23 probands reported that both parents were affected. The researchers found significantly more fathers with psoriatic disease than mothers: 289 (57%) of 509 discordant pairs vs. 220 (43%) of 509 discordant pairs, respectively (P = .003).

The paternal transmission bias did not reach statistical significance in PsC probands (P = .20), but the proportion of paternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (161 [75%] of 214 paternal transmissions) was significantly larger (P = .02) than maternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (103 [64%] of 161 maternal transmissions).

“If PsA is considered a more severe form of psoriatic disease than PsC alone, this finding suggests that there is a greater chance of an increase in disease severity when psoriatic disease is transmitted by an affected male compared to an affected female,” wrote the investigators, led by Remy A. Pollock of Toronto Western Hospital.

Read the full article here: (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 [doi:10.1002/acr.22625]).

Researchers have discovered further evidence of paternal transmission bias in psoriatic disease, according to a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

Significantly more individuals with a first-degree relative affected with psoriatic disease reported an affected father (57%), compared with an affected mother (43%). Self-reported family history was obtained from 849 Canadian adults who reported a first-degree relative affected with either cutaneous psoriasis without arthritis (PsC) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). A total of 532 (63%) reported an affected parent, and 23 probands reported that both parents were affected. The researchers found significantly more fathers with psoriatic disease than mothers: 289 (57%) of 509 discordant pairs vs. 220 (43%) of 509 discordant pairs, respectively (P = .003).

The paternal transmission bias did not reach statistical significance in PsC probands (P = .20), but the proportion of paternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (161 [75%] of 214 paternal transmissions) was significantly larger (P = .02) than maternal PsC–proband PsA pairs (103 [64%] of 161 maternal transmissions).

“If PsA is considered a more severe form of psoriatic disease than PsC alone, this finding suggests that there is a greater chance of an increase in disease severity when psoriatic disease is transmitted by an affected male compared to an affected female,” wrote the investigators, led by Remy A. Pollock of Toronto Western Hospital.

Read the full article here: (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 [doi:10.1002/acr.22625]).

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Psoriasis, PsA increase temporomandibular disorder risk

Psoriasis may play a role in temporomandibular joint disorders, according to an observational study that compared psoriasis patients to individuals without the disorder.

The Italian study, conducted from January 2014 to December 2014, included 112 patients with psoriasis and a 112-person control group. Of the patients with psoriasis, 25 (22%) had psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Patients were examined for temporomandibular disorder (TMD) signs and symptoms based on the standardized Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. TMD was assessed through a questionnaire and a clinical examination.

Overall, patients with psoriasis experienced TMD symptoms significantly more frequently than did members of the control group, with 69% of the psoriasis group reporting one or more symptoms, compared with 24% of the controls. Most often, the patients with psoriasis reported suffering from tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders, muscle pain on chewing, and the sensation of a stuck or locked jaw. The control group’s major complaint was tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement, which are signs of TMD, also were more common in the patients with psoriasis than in the control group.

TMD symptoms and signs were even more common in the subset of patients with PsA, with 80% of these patients reporting symptoms. Additionally, a statistically significant increase in opening derangement, bruxism, and temporomandibular joint sounds occurred in patients with PsA, compared with psoriasis patents without arthritis and controls.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement “were found to be more frequent and severe in patients with psoriasis and PsA than in the healthy subjects, this result being highly significant,” wrote Dr. Vito Crincoli and colleagues at the University of Bari (Italy). “Therefore, in addition to dermatological and rheumatological implications, psoriasis seems to play a role in TMJ disorders, causing an increase in orofacial pain and an altered chewing function.”

Read the full study in the International Journal of Medical Sciences (2015;12:341-8 [doi:10.7150/ijms.11288]).

Psoriasis may play a role in temporomandibular joint disorders, according to an observational study that compared psoriasis patients to individuals without the disorder.

The Italian study, conducted from January 2014 to December 2014, included 112 patients with psoriasis and a 112-person control group. Of the patients with psoriasis, 25 (22%) had psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Patients were examined for temporomandibular disorder (TMD) signs and symptoms based on the standardized Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. TMD was assessed through a questionnaire and a clinical examination.

Overall, patients with psoriasis experienced TMD symptoms significantly more frequently than did members of the control group, with 69% of the psoriasis group reporting one or more symptoms, compared with 24% of the controls. Most often, the patients with psoriasis reported suffering from tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders, muscle pain on chewing, and the sensation of a stuck or locked jaw. The control group’s major complaint was tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement, which are signs of TMD, also were more common in the patients with psoriasis than in the control group.

TMD symptoms and signs were even more common in the subset of patients with PsA, with 80% of these patients reporting symptoms. Additionally, a statistically significant increase in opening derangement, bruxism, and temporomandibular joint sounds occurred in patients with PsA, compared with psoriasis patents without arthritis and controls.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement “were found to be more frequent and severe in patients with psoriasis and PsA than in the healthy subjects, this result being highly significant,” wrote Dr. Vito Crincoli and colleagues at the University of Bari (Italy). “Therefore, in addition to dermatological and rheumatological implications, psoriasis seems to play a role in TMJ disorders, causing an increase in orofacial pain and an altered chewing function.”

Read the full study in the International Journal of Medical Sciences (2015;12:341-8 [doi:10.7150/ijms.11288]).

Psoriasis may play a role in temporomandibular joint disorders, according to an observational study that compared psoriasis patients to individuals without the disorder.

The Italian study, conducted from January 2014 to December 2014, included 112 patients with psoriasis and a 112-person control group. Of the patients with psoriasis, 25 (22%) had psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Patients were examined for temporomandibular disorder (TMD) signs and symptoms based on the standardized Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. TMD was assessed through a questionnaire and a clinical examination.

Overall, patients with psoriasis experienced TMD symptoms significantly more frequently than did members of the control group, with 69% of the psoriasis group reporting one or more symptoms, compared with 24% of the controls. Most often, the patients with psoriasis reported suffering from tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders, muscle pain on chewing, and the sensation of a stuck or locked jaw. The control group’s major complaint was tenderness or stiffness in the neck and shoulders.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement, which are signs of TMD, also were more common in the patients with psoriasis than in the control group.

TMD symptoms and signs were even more common in the subset of patients with PsA, with 80% of these patients reporting symptoms. Additionally, a statistically significant increase in opening derangement, bruxism, and temporomandibular joint sounds occurred in patients with PsA, compared with psoriasis patents without arthritis and controls.

Temporomandibular joint sounds and opening derangement “were found to be more frequent and severe in patients with psoriasis and PsA than in the healthy subjects, this result being highly significant,” wrote Dr. Vito Crincoli and colleagues at the University of Bari (Italy). “Therefore, in addition to dermatological and rheumatological implications, psoriasis seems to play a role in TMJ disorders, causing an increase in orofacial pain and an altered chewing function.”

Read the full study in the International Journal of Medical Sciences (2015;12:341-8 [doi:10.7150/ijms.11288]).

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Chromosome deletion linked to PsA risk

A deletion between the ADAMTS9 and MAGI1 genes was associated with psoriatic arthritis and is unrelated to purely cutaneous psoriasis, according to Dr. Antonio Juliá of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

Of 165 common copy number variants found in both the psoriatic arthritis (PsA) group and control group, only the ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion showed a significant association, with an odds ratio of 1.94. A deletion between the HLA-C and HLA-B genes was initially significant, but the association disappeared after correcting for alleles located at those genes already associated with PsA.

The ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion occurred significantly less often in patients with cutaneous psoriasis (PsC) than in PsA patients, and there was no significant difference in deletion frequency between the control group and the PsC group.

“It is possible, however, that once the specific biological mechanisms influenced by this genetic variation are identified, more targeted analysis will reveal association to other PsA phenotypes,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207190)

A deletion between the ADAMTS9 and MAGI1 genes was associated with psoriatic arthritis and is unrelated to purely cutaneous psoriasis, according to Dr. Antonio Juliá of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

Of 165 common copy number variants found in both the psoriatic arthritis (PsA) group and control group, only the ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion showed a significant association, with an odds ratio of 1.94. A deletion between the HLA-C and HLA-B genes was initially significant, but the association disappeared after correcting for alleles located at those genes already associated with PsA.

The ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion occurred significantly less often in patients with cutaneous psoriasis (PsC) than in PsA patients, and there was no significant difference in deletion frequency between the control group and the PsC group.

“It is possible, however, that once the specific biological mechanisms influenced by this genetic variation are identified, more targeted analysis will reveal association to other PsA phenotypes,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207190)

A deletion between the ADAMTS9 and MAGI1 genes was associated with psoriatic arthritis and is unrelated to purely cutaneous psoriasis, according to Dr. Antonio Juliá of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

Of 165 common copy number variants found in both the psoriatic arthritis (PsA) group and control group, only the ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion showed a significant association, with an odds ratio of 1.94. A deletion between the HLA-C and HLA-B genes was initially significant, but the association disappeared after correcting for alleles located at those genes already associated with PsA.

The ADAMTS9-MAGI1 deletion occurred significantly less often in patients with cutaneous psoriasis (PsC) than in PsA patients, and there was no significant difference in deletion frequency between the control group and the PsC group.

“It is possible, however, that once the specific biological mechanisms influenced by this genetic variation are identified, more targeted analysis will reveal association to other PsA phenotypes,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207190)

Remission of Psoriasis 13 Years After Autologous Stem Cell Transplant

To the Editor:

Remission of psoriasis after bone marrow transplant has been reported1; however, follow-up typically has been limited. We describe a case of a remote recurrence of psoriasis 13 years after autologous stem cell transplant.

In September 1997, a 48-year-old woman with a 20-year history of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, previously managed with oral methotrexate (up to 30–40 mg weekly), presented to her primary care physician with a persistent cough and newly pervasive arthralgia and myalgia. A complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell count of 6.9 mg/dL (reference range, 3.8–10.8 mg/dL), hemoglobin level of 11.6 mg/dL (reference range, 11.7–15.5 mg/dL), and hematocrit level of 34% (reference range, 35.0%–45.0%). Bone survey demonstrated a 4×2-cm lytic expansile lesion in the occipital bone, and a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed 40% plasma cells. She was subsequently diagnosed with stage IIIA IgA λ and free λ light chain multiple myeloma with an IgA level of 62.1 g/L (reference range, 1.24–2.17 g/L).

Therapy was initiated with dexamethasone in combination with pamidronate and she was transitioned to cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. A peripheral autologous blood stem cell transplant followed. Throughout her initial treatment, the psoriasis continued to flare and she remained on methotrexate to help maintain control of the skin disease.

In November 1998, the patient underwent an autologous CD34+ stem cell transplant. There were no complications following the transplant and the multiple myeloma has remained in complete remission to date. Following the stem cell transplant, the patient remained free of psoriatic disease for just over 13 years without any intervention. Recurrent erythematous plaques with thick scale on the bilateral lower legs prompted her return to dermatology in August 2011. To date, she continues to note intermittent though mild flares of her psoriasis. She has responded well to methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% as needed with satisfactory control of her disease.

The development of autoimmune disease following an allogenic bone marrow transplant such as psoriasis, thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and vitiligo has been well described.2-4 The causal relationship between allogenic hematopoetic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and subsequent autoimmune disease has been attributed to T cells and passive transfer of autoimmune disease from the donor to the recipient.1

In the case of autologous HSCT, the remission of autoimmune disease thereafter has been attributed to myeloablative conditioning, whereby high-dose chemotherapy eliminates self-reactive lymphocytes, resulting in ablation of peripheral reactive and alloreactive T cells with depletion of thymus and reactive B cells.1

In 1997, Cooley et al5 described 4 patients with autoimmune disease who experienced complete but temporary (up to 26 months) remission following autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplant. A comprehensive review of psoriasis cases that resolved after HSCT published by Kaffenberger et al6 in 2013 cited 6 cases of autologous and 13 cases of allogenic transplant that resulted in resolution of psoriatic disease. Recurrence of disease was witnessed in 3 of 13 allogenic HSCT patients and 5 of 6 autologous HSCT patients. Of note, all 5 of these patients developed recurrent disease within 24 months following autologous HSCT, albeit with more benign disease.6

Similar to those cases presented by Kaffenberger et al,6 our patient’s psoriatic disease was notably mild compared to her disease prior to HSCT. Although an unintended but welcome outcome of multiple myeloma treatment, the nearly quiescent nature of her skin disease following autologous HSCT has led to a dramatic improvement in her quality of life.

We highlight a unique case in which psoriatic skin disease recurred more than 1 decade after autologous HSCT.

1. Braiteh F, Hymes SR, Giralt SA, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4511-4513.

2. Kishimoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto N, et al. Transfer of autoimmune thyroiditis and resolution of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1997;19:1041-1043.

3. Wahie S, Alexandroff A, Reynolds NY, et al. Psoriasis occurring after myeloablative therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:177-204.

4. Snowden JA, Heaton DC. Development of psoriasis after syngenic bone marrow transplant from psoriatic donor: further evidence for adoptive autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:130-132.

5. Cooley HM, Snowden JA, Grigg AP, et al. Outcome of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis following autologous stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1712-1715.

6. Kaffenberger BH, Wong HK, Jarjour W, et al. Remission of psoriasis after allogenic but not autologous, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:489-492.

To the Editor:

Remission of psoriasis after bone marrow transplant has been reported1; however, follow-up typically has been limited. We describe a case of a remote recurrence of psoriasis 13 years after autologous stem cell transplant.

In September 1997, a 48-year-old woman with a 20-year history of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, previously managed with oral methotrexate (up to 30–40 mg weekly), presented to her primary care physician with a persistent cough and newly pervasive arthralgia and myalgia. A complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell count of 6.9 mg/dL (reference range, 3.8–10.8 mg/dL), hemoglobin level of 11.6 mg/dL (reference range, 11.7–15.5 mg/dL), and hematocrit level of 34% (reference range, 35.0%–45.0%). Bone survey demonstrated a 4×2-cm lytic expansile lesion in the occipital bone, and a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed 40% plasma cells. She was subsequently diagnosed with stage IIIA IgA λ and free λ light chain multiple myeloma with an IgA level of 62.1 g/L (reference range, 1.24–2.17 g/L).

Therapy was initiated with dexamethasone in combination with pamidronate and she was transitioned to cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. A peripheral autologous blood stem cell transplant followed. Throughout her initial treatment, the psoriasis continued to flare and she remained on methotrexate to help maintain control of the skin disease.

In November 1998, the patient underwent an autologous CD34+ stem cell transplant. There were no complications following the transplant and the multiple myeloma has remained in complete remission to date. Following the stem cell transplant, the patient remained free of psoriatic disease for just over 13 years without any intervention. Recurrent erythematous plaques with thick scale on the bilateral lower legs prompted her return to dermatology in August 2011. To date, she continues to note intermittent though mild flares of her psoriasis. She has responded well to methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% as needed with satisfactory control of her disease.

The development of autoimmune disease following an allogenic bone marrow transplant such as psoriasis, thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and vitiligo has been well described.2-4 The causal relationship between allogenic hematopoetic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and subsequent autoimmune disease has been attributed to T cells and passive transfer of autoimmune disease from the donor to the recipient.1

In the case of autologous HSCT, the remission of autoimmune disease thereafter has been attributed to myeloablative conditioning, whereby high-dose chemotherapy eliminates self-reactive lymphocytes, resulting in ablation of peripheral reactive and alloreactive T cells with depletion of thymus and reactive B cells.1

In 1997, Cooley et al5 described 4 patients with autoimmune disease who experienced complete but temporary (up to 26 months) remission following autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplant. A comprehensive review of psoriasis cases that resolved after HSCT published by Kaffenberger et al6 in 2013 cited 6 cases of autologous and 13 cases of allogenic transplant that resulted in resolution of psoriatic disease. Recurrence of disease was witnessed in 3 of 13 allogenic HSCT patients and 5 of 6 autologous HSCT patients. Of note, all 5 of these patients developed recurrent disease within 24 months following autologous HSCT, albeit with more benign disease.6

Similar to those cases presented by Kaffenberger et al,6 our patient’s psoriatic disease was notably mild compared to her disease prior to HSCT. Although an unintended but welcome outcome of multiple myeloma treatment, the nearly quiescent nature of her skin disease following autologous HSCT has led to a dramatic improvement in her quality of life.

We highlight a unique case in which psoriatic skin disease recurred more than 1 decade after autologous HSCT.

To the Editor:

Remission of psoriasis after bone marrow transplant has been reported1; however, follow-up typically has been limited. We describe a case of a remote recurrence of psoriasis 13 years after autologous stem cell transplant.

In September 1997, a 48-year-old woman with a 20-year history of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, previously managed with oral methotrexate (up to 30–40 mg weekly), presented to her primary care physician with a persistent cough and newly pervasive arthralgia and myalgia. A complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell count of 6.9 mg/dL (reference range, 3.8–10.8 mg/dL), hemoglobin level of 11.6 mg/dL (reference range, 11.7–15.5 mg/dL), and hematocrit level of 34% (reference range, 35.0%–45.0%). Bone survey demonstrated a 4×2-cm lytic expansile lesion in the occipital bone, and a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed 40% plasma cells. She was subsequently diagnosed with stage IIIA IgA λ and free λ light chain multiple myeloma with an IgA level of 62.1 g/L (reference range, 1.24–2.17 g/L).

Therapy was initiated with dexamethasone in combination with pamidronate and she was transitioned to cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. A peripheral autologous blood stem cell transplant followed. Throughout her initial treatment, the psoriasis continued to flare and she remained on methotrexate to help maintain control of the skin disease.

In November 1998, the patient underwent an autologous CD34+ stem cell transplant. There were no complications following the transplant and the multiple myeloma has remained in complete remission to date. Following the stem cell transplant, the patient remained free of psoriatic disease for just over 13 years without any intervention. Recurrent erythematous plaques with thick scale on the bilateral lower legs prompted her return to dermatology in August 2011. To date, she continues to note intermittent though mild flares of her psoriasis. She has responded well to methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% as needed with satisfactory control of her disease.

The development of autoimmune disease following an allogenic bone marrow transplant such as psoriasis, thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and vitiligo has been well described.2-4 The causal relationship between allogenic hematopoetic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and subsequent autoimmune disease has been attributed to T cells and passive transfer of autoimmune disease from the donor to the recipient.1

In the case of autologous HSCT, the remission of autoimmune disease thereafter has been attributed to myeloablative conditioning, whereby high-dose chemotherapy eliminates self-reactive lymphocytes, resulting in ablation of peripheral reactive and alloreactive T cells with depletion of thymus and reactive B cells.1

In 1997, Cooley et al5 described 4 patients with autoimmune disease who experienced complete but temporary (up to 26 months) remission following autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplant. A comprehensive review of psoriasis cases that resolved after HSCT published by Kaffenberger et al6 in 2013 cited 6 cases of autologous and 13 cases of allogenic transplant that resulted in resolution of psoriatic disease. Recurrence of disease was witnessed in 3 of 13 allogenic HSCT patients and 5 of 6 autologous HSCT patients. Of note, all 5 of these patients developed recurrent disease within 24 months following autologous HSCT, albeit with more benign disease.6

Similar to those cases presented by Kaffenberger et al,6 our patient’s psoriatic disease was notably mild compared to her disease prior to HSCT. Although an unintended but welcome outcome of multiple myeloma treatment, the nearly quiescent nature of her skin disease following autologous HSCT has led to a dramatic improvement in her quality of life.

We highlight a unique case in which psoriatic skin disease recurred more than 1 decade after autologous HSCT.

1. Braiteh F, Hymes SR, Giralt SA, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4511-4513.

2. Kishimoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto N, et al. Transfer of autoimmune thyroiditis and resolution of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1997;19:1041-1043.

3. Wahie S, Alexandroff A, Reynolds NY, et al. Psoriasis occurring after myeloablative therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:177-204.

4. Snowden JA, Heaton DC. Development of psoriasis after syngenic bone marrow transplant from psoriatic donor: further evidence for adoptive autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:130-132.

5. Cooley HM, Snowden JA, Grigg AP, et al. Outcome of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis following autologous stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1712-1715.

6. Kaffenberger BH, Wong HK, Jarjour W, et al. Remission of psoriasis after allogenic but not autologous, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:489-492.

1. Braiteh F, Hymes SR, Giralt SA, et al. Complete remission of psoriasis after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4511-4513.

2. Kishimoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto N, et al. Transfer of autoimmune thyroiditis and resolution of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1997;19:1041-1043.

3. Wahie S, Alexandroff A, Reynolds NY, et al. Psoriasis occurring after myeloablative therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:177-204.

4. Snowden JA, Heaton DC. Development of psoriasis after syngenic bone marrow transplant from psoriatic donor: further evidence for adoptive autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:130-132.

5. Cooley HM, Snowden JA, Grigg AP, et al. Outcome of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis following autologous stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1712-1715.

6. Kaffenberger BH, Wong HK, Jarjour W, et al. Remission of psoriasis after allogenic but not autologous, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:489-492.

BSR: Multiple benefits seen with intensive psoriatic arthritis therapy

MANCHESTER, U.K. – Multiple joint and skin benefits can be achieved by intensively treating patients with psoriatic arthritis until they achieve a set of minimal disease activity criteria, an expert said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

While data are mounting on the value of treating to target (otherwise known as tight control) in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), these data lag significantly behind that for inducing and maintaining remission in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), noted Dr. Philip Helliwell of the University of Leeds (England).

“There is half as much evidence in PsA as there is in rheumatoid arthritis,” he observed. “But we’ve also got a heterogeneous disease and what we are going to have to do moving forward is to find out how to treat different phenotypic expressions of psoriatic disease, and we’re beginning to work towards that now,” he said during a Special Interest Group on Spondyloarthropathies.

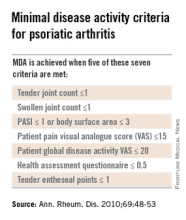

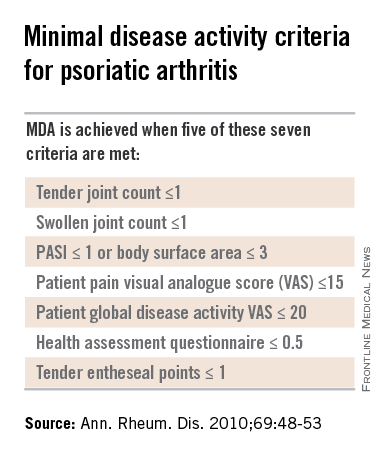

Dr. Helliwell is the principal investigator of the Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) study, which he highlighted as an example of how targeting treatment to achieve minimal disease activity (MDA) criteria (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:48-53) could be beneficial versus standard care.

A total of 206 patients with newly-diagnosed PsA were enrolled into the study and were randomized to receive either ‘tight control’ – meaning an intensive management strategy – or to standard care for 48 weeks.

Intensive treatment involved starting with methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/kg per week and rapidly escalating to 25 mg/kg per week at 6 weeks if needed. If patients did not achieve five out of a set of seven MDA criteria for PsA, then methotrexate was continued and sulfasalazine was added and dose escalated after 4-8 weeks.

If MDA was still not achieved and criteria for biologics were not met according to NICE guidance, then alternatives were swapping out sulfasalazine for cyclosporine or leflunomide, again increasing the doses. Patients who did get put onto a biologic could switch to another anti-TNF if they did not respond after 12 weeks.

The primary endpoint data from the trial have been reported previously and showed that a higher proportion of patients in the intensive management group achieved ACR20 at 48 weeks, compared with those in the standard care group (62% vs. 45%, respectively; P = .02). A higher percentage of intensively managed patients also achieved ACR50 (51% vs. 25%; P = .0004) and ACR70 (38% vs. 17%, P = .002).

Skin symptoms, measured via the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) showed significant improvement favoring intensive therapy over standard care. PASI20 was achieved by 72% of intensively managed patients versus 52% of those who received standard care. PASI75 was achieved by 59% versus 33%, respectively, and PASI90 by 40% versus 20%, respectively.

The full results of the study will be published soon in The Lancet and will include details of a variety of secondary outcomes and the cost-effectiveness of the intensive management strategy versus the standard care approach.

One of the key secondary outcomes of the trial was to look at the effects of the two treatment strategies on other PsA symptoms, such as enthesitis, dactylitis, and nail symptoms. No differences between the groups were observed, however, with similar decreases seen in the tight control and standard care groups.

There were no statistically significant differences in radiologic outcomes, which included baseline and end-of-treatment changes in the total modified Sharp van der Heijde (SVdH) score, the erosion score, and joint-space narrowing (JSN) score.

While this might seem somewhat disappointing, “there wasn’t a lot of radiologic progression going on anyway,” Dr. Helliwell pointed out. Overall, there was a difference of about 5% in the percentage of patients with at least one joint erosion at baseline and after 48 weeks of treatment.

The majority of radiographic change that did occur was JSN of the hands, Dr. Helliwell said, adding that patients with JSN tended to be slightly older than those without, although this observation did not reach statistical significance.

“We’ve since looked for associations with ACPA [anticitrullinated protein antibodies] – about 7% of our patients were ACPA positive – but there is no relationship,” he added. There was also no significant association between levels of C-reactive protein levels and erosive disease.

There was a trend suggesting that patients with erosions may be more likely to have polyarticular disease than oligoarticular disease, so a next step would be to look at radiologic progression in these two groups of patients in more detail.

More adverse events were seen in the tight control arm, compared with the standard care arm, including more serious adverse events, but not all of these were related to study treatment and many adverse events were those to be expected with methotrexate treatment, Dr. Helliwell observed.

But is the intensive approach cost-effective when compared to standard care? Data suggest that it is. Although the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) initially exceeded the £20,000–£30,000 (about $31,000-$47,000) threshold used by the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to judge if a new treatment is cost effective, allowing for certain factors enabled the ICER to be brought down to about £28,000 ($44,000), making it a cost-effective strategy.

PsA consists of five classical subtypes. The most common of these subtypes is polyarthritis (60% of patients), followed by oligoarthritis (30%). The remaining 10% of patients comprise those with arthritis mutilans, distal interphalangeal predominant disease, or spinal predominant disease. The clinical features of dactylitis and enthesitis are prevalent in about 40% and 50% of patients, respectively, and can occur in any subgroup.

Considering such heterogeneity in its presentation, the challenge now will be to determine if all clinical subgroups of PsA could benefit from treating to an MDA target with intensive management, or if one or other subgroups benefit more than another.

The TICOPA study was funded by Arthritis Research UK with support from Pfizer. Dr. Helliwell has received consulting fees from Pfizer.

Results of this study were published in the Lancet Sept. 30, 2015.

This article was updated October 6, 2015.

MANCHESTER, U.K. – Multiple joint and skin benefits can be achieved by intensively treating patients with psoriatic arthritis until they achieve a set of minimal disease activity criteria, an expert said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

While data are mounting on the value of treating to target (otherwise known as tight control) in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), these data lag significantly behind that for inducing and maintaining remission in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), noted Dr. Philip Helliwell of the University of Leeds (England).

“There is half as much evidence in PsA as there is in rheumatoid arthritis,” he observed. “But we’ve also got a heterogeneous disease and what we are going to have to do moving forward is to find out how to treat different phenotypic expressions of psoriatic disease, and we’re beginning to work towards that now,” he said during a Special Interest Group on Spondyloarthropathies.

Dr. Helliwell is the principal investigator of the Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) study, which he highlighted as an example of how targeting treatment to achieve minimal disease activity (MDA) criteria (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:48-53) could be beneficial versus standard care.

A total of 206 patients with newly-diagnosed PsA were enrolled into the study and were randomized to receive either ‘tight control’ – meaning an intensive management strategy – or to standard care for 48 weeks.

Intensive treatment involved starting with methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/kg per week and rapidly escalating to 25 mg/kg per week at 6 weeks if needed. If patients did not achieve five out of a set of seven MDA criteria for PsA, then methotrexate was continued and sulfasalazine was added and dose escalated after 4-8 weeks.

If MDA was still not achieved and criteria for biologics were not met according to NICE guidance, then alternatives were swapping out sulfasalazine for cyclosporine or leflunomide, again increasing the doses. Patients who did get put onto a biologic could switch to another anti-TNF if they did not respond after 12 weeks.

The primary endpoint data from the trial have been reported previously and showed that a higher proportion of patients in the intensive management group achieved ACR20 at 48 weeks, compared with those in the standard care group (62% vs. 45%, respectively; P = .02). A higher percentage of intensively managed patients also achieved ACR50 (51% vs. 25%; P = .0004) and ACR70 (38% vs. 17%, P = .002).

Skin symptoms, measured via the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) showed significant improvement favoring intensive therapy over standard care. PASI20 was achieved by 72% of intensively managed patients versus 52% of those who received standard care. PASI75 was achieved by 59% versus 33%, respectively, and PASI90 by 40% versus 20%, respectively.

The full results of the study will be published soon in The Lancet and will include details of a variety of secondary outcomes and the cost-effectiveness of the intensive management strategy versus the standard care approach.

One of the key secondary outcomes of the trial was to look at the effects of the two treatment strategies on other PsA symptoms, such as enthesitis, dactylitis, and nail symptoms. No differences between the groups were observed, however, with similar decreases seen in the tight control and standard care groups.

There were no statistically significant differences in radiologic outcomes, which included baseline and end-of-treatment changes in the total modified Sharp van der Heijde (SVdH) score, the erosion score, and joint-space narrowing (JSN) score.

While this might seem somewhat disappointing, “there wasn’t a lot of radiologic progression going on anyway,” Dr. Helliwell pointed out. Overall, there was a difference of about 5% in the percentage of patients with at least one joint erosion at baseline and after 48 weeks of treatment.

The majority of radiographic change that did occur was JSN of the hands, Dr. Helliwell said, adding that patients with JSN tended to be slightly older than those without, although this observation did not reach statistical significance.

“We’ve since looked for associations with ACPA [anticitrullinated protein antibodies] – about 7% of our patients were ACPA positive – but there is no relationship,” he added. There was also no significant association between levels of C-reactive protein levels and erosive disease.

There was a trend suggesting that patients with erosions may be more likely to have polyarticular disease than oligoarticular disease, so a next step would be to look at radiologic progression in these two groups of patients in more detail.

More adverse events were seen in the tight control arm, compared with the standard care arm, including more serious adverse events, but not all of these were related to study treatment and many adverse events were those to be expected with methotrexate treatment, Dr. Helliwell observed.

But is the intensive approach cost-effective when compared to standard care? Data suggest that it is. Although the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) initially exceeded the £20,000–£30,000 (about $31,000-$47,000) threshold used by the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to judge if a new treatment is cost effective, allowing for certain factors enabled the ICER to be brought down to about £28,000 ($44,000), making it a cost-effective strategy.

PsA consists of five classical subtypes. The most common of these subtypes is polyarthritis (60% of patients), followed by oligoarthritis (30%). The remaining 10% of patients comprise those with arthritis mutilans, distal interphalangeal predominant disease, or spinal predominant disease. The clinical features of dactylitis and enthesitis are prevalent in about 40% and 50% of patients, respectively, and can occur in any subgroup.

Considering such heterogeneity in its presentation, the challenge now will be to determine if all clinical subgroups of PsA could benefit from treating to an MDA target with intensive management, or if one or other subgroups benefit more than another.

The TICOPA study was funded by Arthritis Research UK with support from Pfizer. Dr. Helliwell has received consulting fees from Pfizer.

Results of this study were published in the Lancet Sept. 30, 2015.

This article was updated October 6, 2015.

MANCHESTER, U.K. – Multiple joint and skin benefits can be achieved by intensively treating patients with psoriatic arthritis until they achieve a set of minimal disease activity criteria, an expert said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

While data are mounting on the value of treating to target (otherwise known as tight control) in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), these data lag significantly behind that for inducing and maintaining remission in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), noted Dr. Philip Helliwell of the University of Leeds (England).

“There is half as much evidence in PsA as there is in rheumatoid arthritis,” he observed. “But we’ve also got a heterogeneous disease and what we are going to have to do moving forward is to find out how to treat different phenotypic expressions of psoriatic disease, and we’re beginning to work towards that now,” he said during a Special Interest Group on Spondyloarthropathies.

Dr. Helliwell is the principal investigator of the Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) study, which he highlighted as an example of how targeting treatment to achieve minimal disease activity (MDA) criteria (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:48-53) could be beneficial versus standard care.

A total of 206 patients with newly-diagnosed PsA were enrolled into the study and were randomized to receive either ‘tight control’ – meaning an intensive management strategy – or to standard care for 48 weeks.

Intensive treatment involved starting with methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/kg per week and rapidly escalating to 25 mg/kg per week at 6 weeks if needed. If patients did not achieve five out of a set of seven MDA criteria for PsA, then methotrexate was continued and sulfasalazine was added and dose escalated after 4-8 weeks.

If MDA was still not achieved and criteria for biologics were not met according to NICE guidance, then alternatives were swapping out sulfasalazine for cyclosporine or leflunomide, again increasing the doses. Patients who did get put onto a biologic could switch to another anti-TNF if they did not respond after 12 weeks.

The primary endpoint data from the trial have been reported previously and showed that a higher proportion of patients in the intensive management group achieved ACR20 at 48 weeks, compared with those in the standard care group (62% vs. 45%, respectively; P = .02). A higher percentage of intensively managed patients also achieved ACR50 (51% vs. 25%; P = .0004) and ACR70 (38% vs. 17%, P = .002).

Skin symptoms, measured via the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) showed significant improvement favoring intensive therapy over standard care. PASI20 was achieved by 72% of intensively managed patients versus 52% of those who received standard care. PASI75 was achieved by 59% versus 33%, respectively, and PASI90 by 40% versus 20%, respectively.

The full results of the study will be published soon in The Lancet and will include details of a variety of secondary outcomes and the cost-effectiveness of the intensive management strategy versus the standard care approach.

One of the key secondary outcomes of the trial was to look at the effects of the two treatment strategies on other PsA symptoms, such as enthesitis, dactylitis, and nail symptoms. No differences between the groups were observed, however, with similar decreases seen in the tight control and standard care groups.

There were no statistically significant differences in radiologic outcomes, which included baseline and end-of-treatment changes in the total modified Sharp van der Heijde (SVdH) score, the erosion score, and joint-space narrowing (JSN) score.

While this might seem somewhat disappointing, “there wasn’t a lot of radiologic progression going on anyway,” Dr. Helliwell pointed out. Overall, there was a difference of about 5% in the percentage of patients with at least one joint erosion at baseline and after 48 weeks of treatment.

The majority of radiographic change that did occur was JSN of the hands, Dr. Helliwell said, adding that patients with JSN tended to be slightly older than those without, although this observation did not reach statistical significance.

“We’ve since looked for associations with ACPA [anticitrullinated protein antibodies] – about 7% of our patients were ACPA positive – but there is no relationship,” he added. There was also no significant association between levels of C-reactive protein levels and erosive disease.

There was a trend suggesting that patients with erosions may be more likely to have polyarticular disease than oligoarticular disease, so a next step would be to look at radiologic progression in these two groups of patients in more detail.

More adverse events were seen in the tight control arm, compared with the standard care arm, including more serious adverse events, but not all of these were related to study treatment and many adverse events were those to be expected with methotrexate treatment, Dr. Helliwell observed.

But is the intensive approach cost-effective when compared to standard care? Data suggest that it is. Although the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) initially exceeded the £20,000–£30,000 (about $31,000-$47,000) threshold used by the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to judge if a new treatment is cost effective, allowing for certain factors enabled the ICER to be brought down to about £28,000 ($44,000), making it a cost-effective strategy.

PsA consists of five classical subtypes. The most common of these subtypes is polyarthritis (60% of patients), followed by oligoarthritis (30%). The remaining 10% of patients comprise those with arthritis mutilans, distal interphalangeal predominant disease, or spinal predominant disease. The clinical features of dactylitis and enthesitis are prevalent in about 40% and 50% of patients, respectively, and can occur in any subgroup.

Considering such heterogeneity in its presentation, the challenge now will be to determine if all clinical subgroups of PsA could benefit from treating to an MDA target with intensive management, or if one or other subgroups benefit more than another.

The TICOPA study was funded by Arthritis Research UK with support from Pfizer. Dr. Helliwell has received consulting fees from Pfizer.

Results of this study were published in the Lancet Sept. 30, 2015.

This article was updated October 6, 2015.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2015

Special Considerations for the Pediatric Population With Psoriasis

Although the clinical presentation of pediatric psoriasis mimics adult disease, there are special considerations for this patient population. Dr. Nanette Silverberg discusses triggers for psoriasis in pediatric patients, including streptococcal infection. She also reviews comorbid conditions and the incidence of obesity in children with psoriasis. Dermatologists also must be aware of the psychological component of this debilitating condition in children and caregivers. Dr. Silverberg outlines off-label therapies that are available for pediatric psoriasis but emphasizes the need for more data in this patient population. Ultimately, more research on pediatric psoriasis will lead to better care and more treatment options for this population.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Although the clinical presentation of pediatric psoriasis mimics adult disease, there are special considerations for this patient population. Dr. Nanette Silverberg discusses triggers for psoriasis in pediatric patients, including streptococcal infection. She also reviews comorbid conditions and the incidence of obesity in children with psoriasis. Dermatologists also must be aware of the psychological component of this debilitating condition in children and caregivers. Dr. Silverberg outlines off-label therapies that are available for pediatric psoriasis but emphasizes the need for more data in this patient population. Ultimately, more research on pediatric psoriasis will lead to better care and more treatment options for this population.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Although the clinical presentation of pediatric psoriasis mimics adult disease, there are special considerations for this patient population. Dr. Nanette Silverberg discusses triggers for psoriasis in pediatric patients, including streptococcal infection. She also reviews comorbid conditions and the incidence of obesity in children with psoriasis. Dermatologists also must be aware of the psychological component of this debilitating condition in children and caregivers. Dr. Silverberg outlines off-label therapies that are available for pediatric psoriasis but emphasizes the need for more data in this patient population. Ultimately, more research on pediatric psoriasis will lead to better care and more treatment options for this population.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Corrona Begins

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

New psoriatic arthritis risk locus unrelated to psoriasis found

The PTPN22 gene was significantly associated with susceptibility to psoriatic arthritis but was not related to psoriasis risk, according to Dr. John Bowes and his associates.

In a total sample of 3,139 psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cases and 11,078 controls, the investigators tested 13 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and found 2 to be significantly associated with PsA, rs4795067 and rs2476601. The single-nucleotide polymorphism rs4795067, which maps to the NOS2 gene, was already known as a risk locus, but rs2476601, which maps to PTPN22, was not. The odds ratio for PTPN22 was 1.32, slightly more than the OR for the previously known NOS2 locus at 1.22.

“The identification of PsA-specific loci is vital in terms of understanding the different pathways involved, which may require different treatments, and for future screening strategies to identify subjects at risk of developing PsA in patients with psoriasis,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207187).

The PTPN22 gene was significantly associated with susceptibility to psoriatic arthritis but was not related to psoriasis risk, according to Dr. John Bowes and his associates.

In a total sample of 3,139 psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cases and 11,078 controls, the investigators tested 13 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and found 2 to be significantly associated with PsA, rs4795067 and rs2476601. The single-nucleotide polymorphism rs4795067, which maps to the NOS2 gene, was already known as a risk locus, but rs2476601, which maps to PTPN22, was not. The odds ratio for PTPN22 was 1.32, slightly more than the OR for the previously known NOS2 locus at 1.22.

“The identification of PsA-specific loci is vital in terms of understanding the different pathways involved, which may require different treatments, and for future screening strategies to identify subjects at risk of developing PsA in patients with psoriasis,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207187).

The PTPN22 gene was significantly associated with susceptibility to psoriatic arthritis but was not related to psoriasis risk, according to Dr. John Bowes and his associates.

In a total sample of 3,139 psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cases and 11,078 controls, the investigators tested 13 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and found 2 to be significantly associated with PsA, rs4795067 and rs2476601. The single-nucleotide polymorphism rs4795067, which maps to the NOS2 gene, was already known as a risk locus, but rs2476601, which maps to PTPN22, was not. The odds ratio for PTPN22 was 1.32, slightly more than the OR for the previously known NOS2 locus at 1.22.

“The identification of PsA-specific loci is vital in terms of understanding the different pathways involved, which may require different treatments, and for future screening strategies to identify subjects at risk of developing PsA in patients with psoriasis,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full study in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207187).