User login

The longevity gene: Healthy mutant reverses heart aging

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Canadian guidance recommends reducing alcohol consumption

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Will your smartphone be the next doctor’s office?

A fingertip pressed against a phone’s camera lens can measure a heart rate. The microphone, kept by the bedside, can screen for sleep apnea. Even the speaker is being tapped, to monitor breathing using sonar technology.

In the best of this new world, the data is conveyed remotely to a medical professional for the convenience and comfort of the patient or, in some cases, to support a clinician without the need for costly hardware.

But using smartphones as diagnostic tools is a work in progress, experts say. Although doctors and their patients have found some real-world success in deploying the phone as a medical device, the overall potential remains unfulfilled and uncertain.

Smartphones come packed with sensors capable of monitoring a patient’s vital signs. They can help assess people for concussions, watch for atrial fibrillation, and conduct mental health wellness checks, to name the uses of a few nascent applications.

Companies and researchers eager to find medical applications for smartphone technology are tapping into modern phones’ built-in cameras and light sensors; microphones; accelerometers, which detect body movements; gyroscopes; and even speakers. The apps then use artificial intelligence software to analyze the collected sights and sounds to create an easy connection between patients and physicians. Earning potential and marketability are evidenced by the more than 350,000 digital health products available in app stores, according to a Grand View Research report.

“It’s very hard to put devices into the patient home or in the hospital, but everybody is just walking around with a cellphone that has a network connection,” said Dr. Andrew Gostine, CEO of the sensor network company Artisight. Most Americans own a smartphone, including more than 60% of people 65 and over, an increase from just 13% a decade ago, according the Pew Research Center. The COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed people to become more comfortable with virtual care.

Some of these products have sought FDA clearance to be marketed as a medical device. That way, if patients must pay to use the software, health insurers are more likely to cover at least part of the cost. Other products are designated as exempt from this regulatory process, placed in the same clinical classification as a Band-Aid. But how the agency handles AI and machine learning–based medical devices is still being adjusted to reflect software’s adaptive nature.

Ensuring accuracy and clinical validation is crucial to securing buy-in from health care providers. And many tools still need fine-tuning, said Eugene Yang, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Currently, Dr. Yang is testing contactless measurement of blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation gleaned remotely via Zoom camera footage of a patient’s face.

Judging these new technologies is difficult because they rely on algorithms built by machine learning and artificial intelligence to collect data, rather than the physical tools typically used in hospitals. So researchers cannot “compare apples to apples” with medical industry standards, Dr. Yang said. Failure to build in such assurances undermines the technology’s ultimate goals of easing costs and access because a doctor still must verify results.

“False positives and false negatives lead to more testing and more cost to the health care system,” he said.

Big tech companies like Google have heavily invested in researching this kind of technology, catering to clinicians and in-home caregivers, as well as consumers. Currently, in the Google Fit app, users can check their heart rate by placing their finger on the rear-facing camera lens or track their breathing rate using the front-facing camera.

“If you took the sensor out of the phone and out of a clinical device, they are probably the same thing,” said Shwetak Patel, director of health technologies at Google and a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Washington.

Google’s research uses machine learning and computer vision, a field within AI based on information from visual inputs like videos or images. So instead of using a blood pressure cuff, for example, the algorithm can interpret slight visual changes to the body that serve as proxies and biosignals for a patient’s blood pressure, Mr. Patel said.

Google is also investigating the effectiveness of the built-in microphone for detecting heartbeats and murmurs and using the camera to preserve eyesight by screening for diabetic eye disease, according to information the company published last year.

The tech giant recently purchased Sound Life Sciences, a Seattle startup with an FDA-cleared sonar technology app. It uses a smart device’s speaker to bounce inaudible pulses off a patient’s body to identify movement and monitor breathing.

Binah.ai, based in Israel, is another company using the smartphone camera to calculate vital signs. Its software looks at the region around the eyes, where the skin is a bit thinner, and analyzes the light reflecting off blood vessels back to the lens. The company is wrapping up a U.S. clinical trial and marketing its wellness app directly to insurers and other health companies, said company spokesperson Mona Popilian-Yona.

The applications even reach into disciplines such as optometry and mental health:

- With the microphone, Canary Speech uses the same underlying technology as Amazon’s Alexa to analyze patients’ voices for mental health conditions. The software can integrate with telemedicine appointments and allow clinicians to screen for anxiety and depression using a library of vocal biomarkers and predictive analytics, said Henry O’Connell, the company’s CEO.

- Australia-based ResApp Health last year for its iPhone app that screens for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea by listening to breathing and snoring. SleepCheckRx, which will require a prescription, is minimally invasive compared with sleep studies currently used to diagnose sleep apnea. Those can cost thousands of dollars and require an array of tests.

- Brightlamp’s Reflex app is a clinical decision support tool for helping manage concussions and vision rehabilitation, among other things. Using an iPad’s or iPhone’s camera, the mobile app measures how a person’s pupils react to changes in light. Through machine learning analysis, the imagery gives practitioners data points for evaluating patients. Brightlamp sells directly to health care providers and is being used in more than 230 clinics. Clinicians pay a $400 standard annual fee per account, which is currently not covered by insurance. The Department of Defense has an ongoing clinical trial using Reflex.

In some cases, such as with the Reflex app, the data is processed directly on the phone – rather than in the cloud, Brightlamp CEO Kurtis Sluss said. By processing everything on the device, the app avoids running into privacy issues, as streaming data elsewhere requires patient consent.

But algorithms need to be trained and tested by collecting reams of data, and that is an ongoing process.

Researchers, for example, have found that some computer vision applications, like heart rate or blood pressure monitoring, can be less accurate for darker skin. Studies are underway to find better solutions.

Small algorithm glitches can also produce false alarms and frighten patients enough to keep widespread adoption out of reach. For example, Apple’s new car-crash detection feature, available on both the latest iPhone and Apple Watch, was set off when people were riding roller coasters and automatically dialed 911.

“We’re not there yet,” Dr. Yang said. “That’s the bottom line.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

A fingertip pressed against a phone’s camera lens can measure a heart rate. The microphone, kept by the bedside, can screen for sleep apnea. Even the speaker is being tapped, to monitor breathing using sonar technology.

In the best of this new world, the data is conveyed remotely to a medical professional for the convenience and comfort of the patient or, in some cases, to support a clinician without the need for costly hardware.

But using smartphones as diagnostic tools is a work in progress, experts say. Although doctors and their patients have found some real-world success in deploying the phone as a medical device, the overall potential remains unfulfilled and uncertain.

Smartphones come packed with sensors capable of monitoring a patient’s vital signs. They can help assess people for concussions, watch for atrial fibrillation, and conduct mental health wellness checks, to name the uses of a few nascent applications.

Companies and researchers eager to find medical applications for smartphone technology are tapping into modern phones’ built-in cameras and light sensors; microphones; accelerometers, which detect body movements; gyroscopes; and even speakers. The apps then use artificial intelligence software to analyze the collected sights and sounds to create an easy connection between patients and physicians. Earning potential and marketability are evidenced by the more than 350,000 digital health products available in app stores, according to a Grand View Research report.

“It’s very hard to put devices into the patient home or in the hospital, but everybody is just walking around with a cellphone that has a network connection,” said Dr. Andrew Gostine, CEO of the sensor network company Artisight. Most Americans own a smartphone, including more than 60% of people 65 and over, an increase from just 13% a decade ago, according the Pew Research Center. The COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed people to become more comfortable with virtual care.

Some of these products have sought FDA clearance to be marketed as a medical device. That way, if patients must pay to use the software, health insurers are more likely to cover at least part of the cost. Other products are designated as exempt from this regulatory process, placed in the same clinical classification as a Band-Aid. But how the agency handles AI and machine learning–based medical devices is still being adjusted to reflect software’s adaptive nature.

Ensuring accuracy and clinical validation is crucial to securing buy-in from health care providers. And many tools still need fine-tuning, said Eugene Yang, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Currently, Dr. Yang is testing contactless measurement of blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation gleaned remotely via Zoom camera footage of a patient’s face.

Judging these new technologies is difficult because they rely on algorithms built by machine learning and artificial intelligence to collect data, rather than the physical tools typically used in hospitals. So researchers cannot “compare apples to apples” with medical industry standards, Dr. Yang said. Failure to build in such assurances undermines the technology’s ultimate goals of easing costs and access because a doctor still must verify results.

“False positives and false negatives lead to more testing and more cost to the health care system,” he said.

Big tech companies like Google have heavily invested in researching this kind of technology, catering to clinicians and in-home caregivers, as well as consumers. Currently, in the Google Fit app, users can check their heart rate by placing their finger on the rear-facing camera lens or track their breathing rate using the front-facing camera.

“If you took the sensor out of the phone and out of a clinical device, they are probably the same thing,” said Shwetak Patel, director of health technologies at Google and a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Washington.

Google’s research uses machine learning and computer vision, a field within AI based on information from visual inputs like videos or images. So instead of using a blood pressure cuff, for example, the algorithm can interpret slight visual changes to the body that serve as proxies and biosignals for a patient’s blood pressure, Mr. Patel said.

Google is also investigating the effectiveness of the built-in microphone for detecting heartbeats and murmurs and using the camera to preserve eyesight by screening for diabetic eye disease, according to information the company published last year.

The tech giant recently purchased Sound Life Sciences, a Seattle startup with an FDA-cleared sonar technology app. It uses a smart device’s speaker to bounce inaudible pulses off a patient’s body to identify movement and monitor breathing.

Binah.ai, based in Israel, is another company using the smartphone camera to calculate vital signs. Its software looks at the region around the eyes, where the skin is a bit thinner, and analyzes the light reflecting off blood vessels back to the lens. The company is wrapping up a U.S. clinical trial and marketing its wellness app directly to insurers and other health companies, said company spokesperson Mona Popilian-Yona.

The applications even reach into disciplines such as optometry and mental health:

- With the microphone, Canary Speech uses the same underlying technology as Amazon’s Alexa to analyze patients’ voices for mental health conditions. The software can integrate with telemedicine appointments and allow clinicians to screen for anxiety and depression using a library of vocal biomarkers and predictive analytics, said Henry O’Connell, the company’s CEO.

- Australia-based ResApp Health last year for its iPhone app that screens for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea by listening to breathing and snoring. SleepCheckRx, which will require a prescription, is minimally invasive compared with sleep studies currently used to diagnose sleep apnea. Those can cost thousands of dollars and require an array of tests.

- Brightlamp’s Reflex app is a clinical decision support tool for helping manage concussions and vision rehabilitation, among other things. Using an iPad’s or iPhone’s camera, the mobile app measures how a person’s pupils react to changes in light. Through machine learning analysis, the imagery gives practitioners data points for evaluating patients. Brightlamp sells directly to health care providers and is being used in more than 230 clinics. Clinicians pay a $400 standard annual fee per account, which is currently not covered by insurance. The Department of Defense has an ongoing clinical trial using Reflex.

In some cases, such as with the Reflex app, the data is processed directly on the phone – rather than in the cloud, Brightlamp CEO Kurtis Sluss said. By processing everything on the device, the app avoids running into privacy issues, as streaming data elsewhere requires patient consent.

But algorithms need to be trained and tested by collecting reams of data, and that is an ongoing process.

Researchers, for example, have found that some computer vision applications, like heart rate or blood pressure monitoring, can be less accurate for darker skin. Studies are underway to find better solutions.

Small algorithm glitches can also produce false alarms and frighten patients enough to keep widespread adoption out of reach. For example, Apple’s new car-crash detection feature, available on both the latest iPhone and Apple Watch, was set off when people were riding roller coasters and automatically dialed 911.

“We’re not there yet,” Dr. Yang said. “That’s the bottom line.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

A fingertip pressed against a phone’s camera lens can measure a heart rate. The microphone, kept by the bedside, can screen for sleep apnea. Even the speaker is being tapped, to monitor breathing using sonar technology.

In the best of this new world, the data is conveyed remotely to a medical professional for the convenience and comfort of the patient or, in some cases, to support a clinician without the need for costly hardware.

But using smartphones as diagnostic tools is a work in progress, experts say. Although doctors and their patients have found some real-world success in deploying the phone as a medical device, the overall potential remains unfulfilled and uncertain.

Smartphones come packed with sensors capable of monitoring a patient’s vital signs. They can help assess people for concussions, watch for atrial fibrillation, and conduct mental health wellness checks, to name the uses of a few nascent applications.

Companies and researchers eager to find medical applications for smartphone technology are tapping into modern phones’ built-in cameras and light sensors; microphones; accelerometers, which detect body movements; gyroscopes; and even speakers. The apps then use artificial intelligence software to analyze the collected sights and sounds to create an easy connection between patients and physicians. Earning potential and marketability are evidenced by the more than 350,000 digital health products available in app stores, according to a Grand View Research report.

“It’s very hard to put devices into the patient home or in the hospital, but everybody is just walking around with a cellphone that has a network connection,” said Dr. Andrew Gostine, CEO of the sensor network company Artisight. Most Americans own a smartphone, including more than 60% of people 65 and over, an increase from just 13% a decade ago, according the Pew Research Center. The COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed people to become more comfortable with virtual care.

Some of these products have sought FDA clearance to be marketed as a medical device. That way, if patients must pay to use the software, health insurers are more likely to cover at least part of the cost. Other products are designated as exempt from this regulatory process, placed in the same clinical classification as a Band-Aid. But how the agency handles AI and machine learning–based medical devices is still being adjusted to reflect software’s adaptive nature.

Ensuring accuracy and clinical validation is crucial to securing buy-in from health care providers. And many tools still need fine-tuning, said Eugene Yang, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Currently, Dr. Yang is testing contactless measurement of blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation gleaned remotely via Zoom camera footage of a patient’s face.

Judging these new technologies is difficult because they rely on algorithms built by machine learning and artificial intelligence to collect data, rather than the physical tools typically used in hospitals. So researchers cannot “compare apples to apples” with medical industry standards, Dr. Yang said. Failure to build in such assurances undermines the technology’s ultimate goals of easing costs and access because a doctor still must verify results.

“False positives and false negatives lead to more testing and more cost to the health care system,” he said.

Big tech companies like Google have heavily invested in researching this kind of technology, catering to clinicians and in-home caregivers, as well as consumers. Currently, in the Google Fit app, users can check their heart rate by placing their finger on the rear-facing camera lens or track their breathing rate using the front-facing camera.

“If you took the sensor out of the phone and out of a clinical device, they are probably the same thing,” said Shwetak Patel, director of health technologies at Google and a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Washington.

Google’s research uses machine learning and computer vision, a field within AI based on information from visual inputs like videos or images. So instead of using a blood pressure cuff, for example, the algorithm can interpret slight visual changes to the body that serve as proxies and biosignals for a patient’s blood pressure, Mr. Patel said.

Google is also investigating the effectiveness of the built-in microphone for detecting heartbeats and murmurs and using the camera to preserve eyesight by screening for diabetic eye disease, according to information the company published last year.

The tech giant recently purchased Sound Life Sciences, a Seattle startup with an FDA-cleared sonar technology app. It uses a smart device’s speaker to bounce inaudible pulses off a patient’s body to identify movement and monitor breathing.

Binah.ai, based in Israel, is another company using the smartphone camera to calculate vital signs. Its software looks at the region around the eyes, where the skin is a bit thinner, and analyzes the light reflecting off blood vessels back to the lens. The company is wrapping up a U.S. clinical trial and marketing its wellness app directly to insurers and other health companies, said company spokesperson Mona Popilian-Yona.

The applications even reach into disciplines such as optometry and mental health:

- With the microphone, Canary Speech uses the same underlying technology as Amazon’s Alexa to analyze patients’ voices for mental health conditions. The software can integrate with telemedicine appointments and allow clinicians to screen for anxiety and depression using a library of vocal biomarkers and predictive analytics, said Henry O’Connell, the company’s CEO.

- Australia-based ResApp Health last year for its iPhone app that screens for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea by listening to breathing and snoring. SleepCheckRx, which will require a prescription, is minimally invasive compared with sleep studies currently used to diagnose sleep apnea. Those can cost thousands of dollars and require an array of tests.

- Brightlamp’s Reflex app is a clinical decision support tool for helping manage concussions and vision rehabilitation, among other things. Using an iPad’s or iPhone’s camera, the mobile app measures how a person’s pupils react to changes in light. Through machine learning analysis, the imagery gives practitioners data points for evaluating patients. Brightlamp sells directly to health care providers and is being used in more than 230 clinics. Clinicians pay a $400 standard annual fee per account, which is currently not covered by insurance. The Department of Defense has an ongoing clinical trial using Reflex.

In some cases, such as with the Reflex app, the data is processed directly on the phone – rather than in the cloud, Brightlamp CEO Kurtis Sluss said. By processing everything on the device, the app avoids running into privacy issues, as streaming data elsewhere requires patient consent.

But algorithms need to be trained and tested by collecting reams of data, and that is an ongoing process.

Researchers, for example, have found that some computer vision applications, like heart rate or blood pressure monitoring, can be less accurate for darker skin. Studies are underway to find better solutions.

Small algorithm glitches can also produce false alarms and frighten patients enough to keep widespread adoption out of reach. For example, Apple’s new car-crash detection feature, available on both the latest iPhone and Apple Watch, was set off when people were riding roller coasters and automatically dialed 911.

“We’re not there yet,” Dr. Yang said. “That’s the bottom line.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Sleep complaints in major depression flag risk for other psychiatric disorders

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

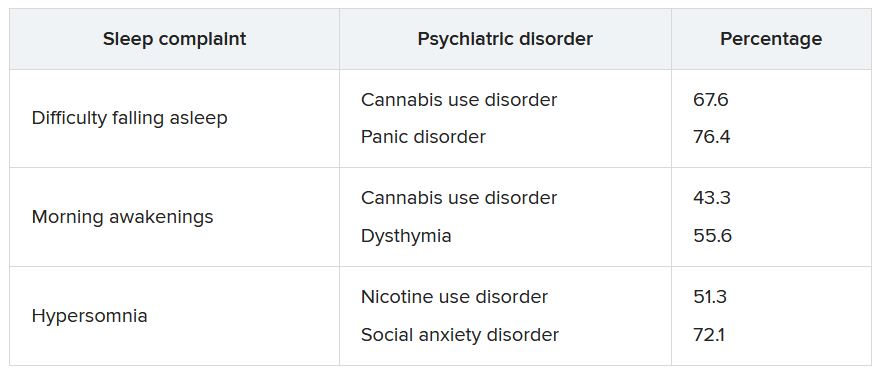

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.

Hypersomnia, in particular, significantly increased the odds of having another psychiatric disorder. For patients with MDD who reported hypersomnia, the mean number of sleep disorders was significantly higher than for patients without hypersomnia (2.08 vs. 1.32; P < .001).

“This explains why hypersomnia appears more strongly associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and antisocial personality disorder, the effects shared across all sleep complaints were “significantly associated with the incident general psychopathology factor, representing mechanisms that may lead to incidence of all psychiatric disorder in the model,” they add.

The researchers note that insomnia and hypersomnia can impair cognitive function, decision-making, problem-solving, and emotion processing networks, thereby increasing the onset of psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals.

Shared biological determinants, such as monoamine neurotransmitters that play a major role in depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and the regulation of sleep stages, may also underlie both sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, they speculate.

“These results suggest the importance of systematically assessing insomnia and hypersomnia when evaluating psychiatric disorders and considering these symptoms as nonspecific prodromal or at-risk symptoms, also shared with suicidal behaviors,” the investigators write.

“In addition, since most individuals who developed a psychiatric disorder had at least one sleep complaint, all psychiatric disorders should be carefully screened among individuals with sleep complaints,” they add.

Transdiagnostic phenomenon

In a comment, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, noted that the study replicates previous observations that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbances and mental disorders and that there “seems to be a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality that is bidirectional.”

He added that he appreciated the fact that the investigators “took this knowledge one step further; and what they are saying is that within the syndrome of depression, it is the sleep disturbance that is predicting future problems.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation in Toronto, was not involved with the study.

The data suggest that, “conceptually, sleep disturbance is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that may also be the nexus when multiple comorbid mental disorders occur,” he said.

“If this is the case, clinically, there is an opportunity here to prevent incident mental disorders in persons with depression and sleep disturbance, prioritizing sleep management in any patient with a mood disorder,” Dr. McIntyre added.

He noted that “the testable hypothesis” is how this is occurring mechanistically.

“I would conjecture that it could be inflammation and/or insulin resistance that is part of sleep disturbance that could predispose and portend other mental illnesses – and likely other medical conditions too, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said.

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute; has received speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes,Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences; and is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

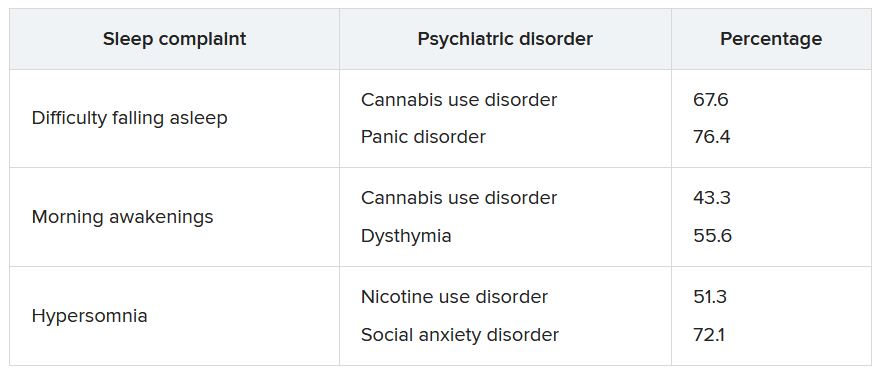

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.

Hypersomnia, in particular, significantly increased the odds of having another psychiatric disorder. For patients with MDD who reported hypersomnia, the mean number of sleep disorders was significantly higher than for patients without hypersomnia (2.08 vs. 1.32; P < .001).

“This explains why hypersomnia appears more strongly associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and antisocial personality disorder, the effects shared across all sleep complaints were “significantly associated with the incident general psychopathology factor, representing mechanisms that may lead to incidence of all psychiatric disorder in the model,” they add.

The researchers note that insomnia and hypersomnia can impair cognitive function, decision-making, problem-solving, and emotion processing networks, thereby increasing the onset of psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals.

Shared biological determinants, such as monoamine neurotransmitters that play a major role in depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and the regulation of sleep stages, may also underlie both sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, they speculate.

“These results suggest the importance of systematically assessing insomnia and hypersomnia when evaluating psychiatric disorders and considering these symptoms as nonspecific prodromal or at-risk symptoms, also shared with suicidal behaviors,” the investigators write.

“In addition, since most individuals who developed a psychiatric disorder had at least one sleep complaint, all psychiatric disorders should be carefully screened among individuals with sleep complaints,” they add.

Transdiagnostic phenomenon

In a comment, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, noted that the study replicates previous observations that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbances and mental disorders and that there “seems to be a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality that is bidirectional.”

He added that he appreciated the fact that the investigators “took this knowledge one step further; and what they are saying is that within the syndrome of depression, it is the sleep disturbance that is predicting future problems.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation in Toronto, was not involved with the study.

The data suggest that, “conceptually, sleep disturbance is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that may also be the nexus when multiple comorbid mental disorders occur,” he said.

“If this is the case, clinically, there is an opportunity here to prevent incident mental disorders in persons with depression and sleep disturbance, prioritizing sleep management in any patient with a mood disorder,” Dr. McIntyre added.

He noted that “the testable hypothesis” is how this is occurring mechanistically.

“I would conjecture that it could be inflammation and/or insulin resistance that is part of sleep disturbance that could predispose and portend other mental illnesses – and likely other medical conditions too, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said.

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute; has received speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes,Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences; and is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

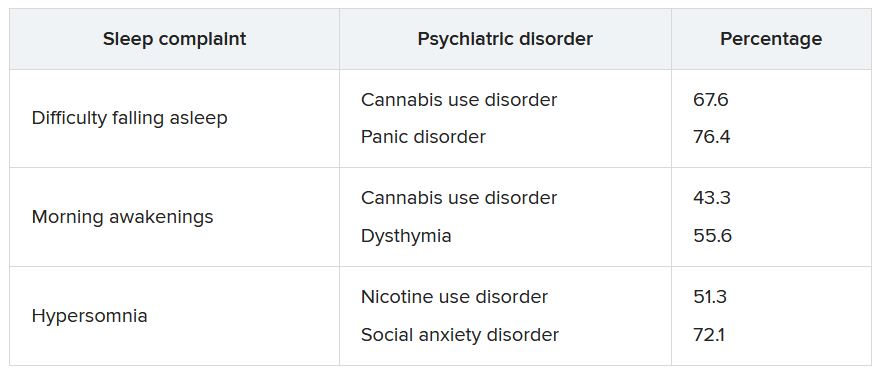

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.