User login

Chest reconstruction surgeries up nearly fourfold among adolescents

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Options and outcomes for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

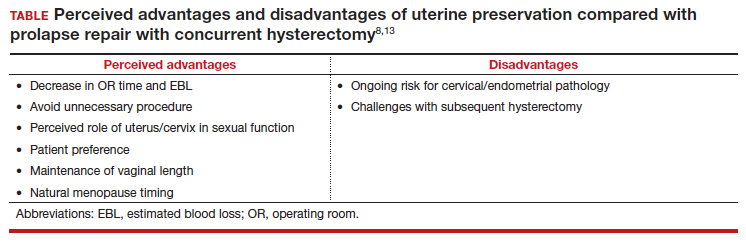

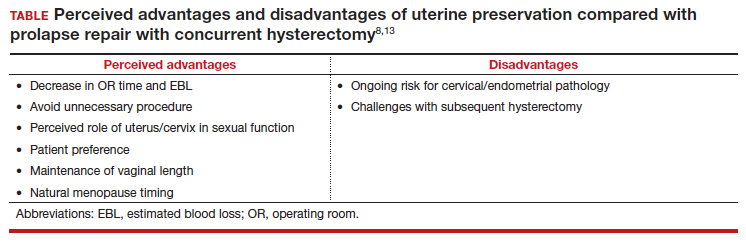

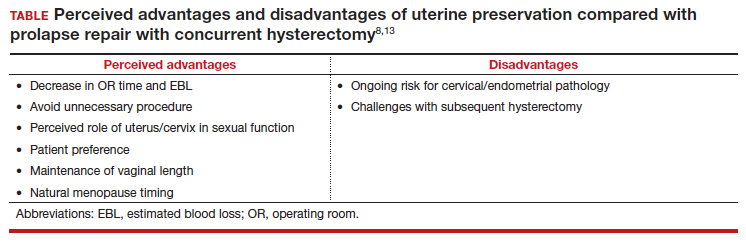

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

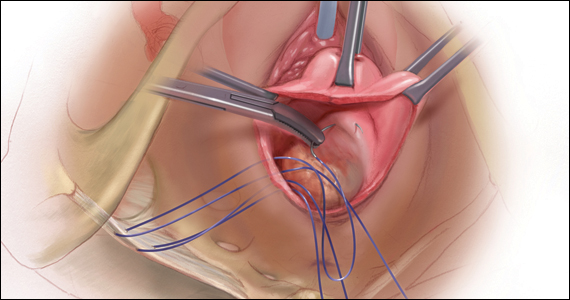

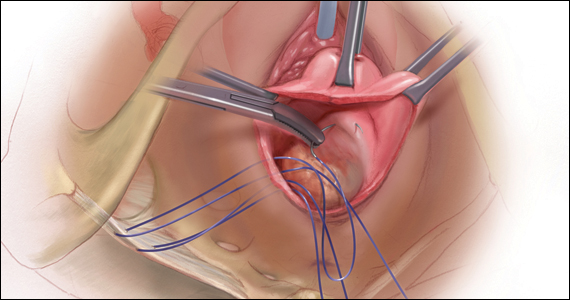

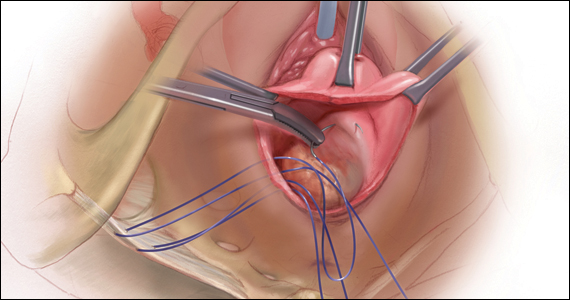

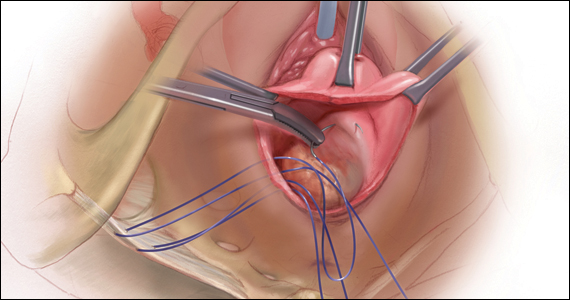

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

Gender-affirming mastectomy boosts image and quality of life in gender-diverse youth

Adolescents and young adults who undergo “top surgery” for gender dysphoria overwhelmingly report being satisfied with the procedure in the near-term, new research shows.

The results of the prospective cohort study, reported recently in JAMA Pediatrics, suggest that the surgery can help facilitate gender congruence and comfort with body image for transmasculine and nonbinary youth. The authors, from Northwestern University, Chicago, said the findings may “help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery.”

Sumanas Jordan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of plastic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a coauthor of the study, said the study was the first prospective, matched cohort analysis showing that chest surgery improves outcomes in this age group.

“We focused our study on chest dysphoria, the distress due to the presence of breasts, and gender congruence, the feeling of alignment between identity and physical characteristics,” Dr. Jordan said. “We will continue to study the effect of surgery in other areas of health, such as physical functioning and quality of life, and follow our patients longer term.”

As many as 9% of adolescents and young adults identify as transgender or nonbinary - a group underrepresented in the pediatric literature, Dr. Jordan’s group said. Chest dysphoria often is associated with psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety.

“Dysphoria can lead to a range of negative physical and emotional consequences, such as avoidance of exercise and sports, harmful chest-binding practices, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation, said M. Brett Cooper, MD, MEd, assistant professor of pediatrics, and adolescent and young adult medicine, at UT Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health, Dallas. “These young people often bind for several hours a day to reduce the presence of their chest.”

The study

The Northwestern team recruited 81 patients with a mean age of 18.6 years whose sex at birth was assigned female. Patients were overwhelmingly White (89%), and the majority (59%) were transgender male, the remaining patients nonbinary.

The population sample included patients aged 13-24 who underwent top surgery from December 2019 to April 2021 and a matched control group of those who did not have surgery.

Outcomes measures were assessed preoperatively and 3 months after surgery.

Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 of those in the control arm completed the outcomes measures. Surgical complications were minimal. Propensity analyses suggested an association between surgery and substantial improvements in scores on the following study endpoints:

- Chest dysphoria measure (–25.58 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], –29.18 to –21.98).

- Transgender congruence scale (7.78 points, 95%: CI, 6.06-9.50)

- Body image scale (–7.20 points, 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72).

The patients who underwent top surgery reported significant improvements in scores of chest dysphoria, transgender congruence, and body image. The results for patients younger than age 18 paralleled those for older participants in the study.

While the results corroborate other studies showing that gender-affirming therapy improves mental health and quality of life among these young people, the researchers cautioned that some insurers require testosterone therapy for 1 year before their plans will cover the costs of gender-affirming surgery.

This may negatively affect those nonbinary patients who do not undergo hormone therapy,” the researchers wrote. They are currently collecting 1-year follow-up data to determine the long-term effects of top surgery on chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image.

As surgical patients progress through adult life, does the risk of regret increase? “We did not address regret in this short-term study,” Dr. Jordan said. “However, previous studies have shown very low levels of regret.”

An accompanying editorial concurred that top surgery is effective and medically necessary in this population of young people.

Calling the study “an important milestone in gender affirmation research,” Kishan M. Thadikonda, MD, and Katherine M. Gast, MD, MS, of the school of medicine and public health at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said it will be important to follow this young cohort to prove these benefits will endure as patients age.

They cautioned, however, that nonbinary patients represented just 13% of the patient total and only 8% of the surgical cohort. Nonbinary patients are not well understood as a patient population when it comes to gender-affirmation surgery and are often included in studies with transgender patients despite clear differences, they noted.

Current setbacks

According to Dr. Cooper, politics is already affecting care in Texas. “Due to the sociopolitical climate in my state in regard to gender-affirming care, I have also seen a few young people have their surgeries either canceled or postponed by their parents,” he said. “This has led to a worsening of mental health in these patients.”

Dr. Cooper stressed the need for more research on the perspective of non-White and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.

“This study also highlights the disparity between patients who have commercial insurance versus those who are on Medicaid,” he said. “Medicaid plans often do not cover this, so those patients usually have to continue to suffer or pay for this surgery out of their own pocket.”

This study was supported by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. Funding also came from the Plastic Surgery Foundation and American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgery. Dr. Jordan received grants from the Plastic Surgery Foundation during the study. One coauthor reported consultant fees from CVS Caremark for consulting outside the submitted work, and another reported grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Cooper disclosed no competing interests relevant to his comments. The editorial commentators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Adolescents and young adults who undergo “top surgery” for gender dysphoria overwhelmingly report being satisfied with the procedure in the near-term, new research shows.

The results of the prospective cohort study, reported recently in JAMA Pediatrics, suggest that the surgery can help facilitate gender congruence and comfort with body image for transmasculine and nonbinary youth. The authors, from Northwestern University, Chicago, said the findings may “help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery.”

Sumanas Jordan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of plastic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a coauthor of the study, said the study was the first prospective, matched cohort analysis showing that chest surgery improves outcomes in this age group.

“We focused our study on chest dysphoria, the distress due to the presence of breasts, and gender congruence, the feeling of alignment between identity and physical characteristics,” Dr. Jordan said. “We will continue to study the effect of surgery in other areas of health, such as physical functioning and quality of life, and follow our patients longer term.”

As many as 9% of adolescents and young adults identify as transgender or nonbinary - a group underrepresented in the pediatric literature, Dr. Jordan’s group said. Chest dysphoria often is associated with psychosocial issues such as depression and anxiety.

“Dysphoria can lead to a range of negative physical and emotional consequences, such as avoidance of exercise and sports, harmful chest-binding practices, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation, said M. Brett Cooper, MD, MEd, assistant professor of pediatrics, and adolescent and young adult medicine, at UT Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health, Dallas. “These young people often bind for several hours a day to reduce the presence of their chest.”

The study

The Northwestern team recruited 81 patients with a mean age of 18.6 years whose sex at birth was assigned female. Patients were overwhelmingly White (89%), and the majority (59%) were transgender male, the remaining patients nonbinary.

The population sample included patients aged 13-24 who underwent top surgery from December 2019 to April 2021 and a matched control group of those who did not have surgery.

Outcomes measures were assessed preoperatively and 3 months after surgery.

Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 of those in the control arm completed the outcomes measures. Surgical complications were minimal. Propensity analyses suggested an association between surgery and substantial improvements in scores on the following study endpoints:

- Chest dysphoria measure (–25.58 points, 95% confidence interval [CI], –29.18 to –21.98).

- Transgender congruence scale (7.78 points, 95%: CI, 6.06-9.50)

- Body image scale (–7.20 points, 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72).

The patients who underwent top surgery reported significant improvements in scores of chest dysphoria, transgender congruence, and body image. The results for patients younger than age 18 paralleled those for older participants in the study.