User login

Update on high-grade vulvar interepithelial neoplasia

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Neurosurgery Operating Room Efficiency During the COVID-19 Era

From the Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Stefan W. Koester, Puja Jagasia, and Drs. Liles, Dambrino IV, Feldman, and Chambless), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Drs. Mathews and Tiwari).

ABSTRACT

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has had broad effects on surgical care, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and newly implemented anti-infective measures. Our aim was to assess neurosurgery OR efficiency before the COVID-19 pandemic, during peak COVID-19, and during current times.

Methods: Institutional perioperative databases at a single, high-volume neurosurgical center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, the day that the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency, was chosen as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 90-day periods before and after this day were used to define the pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-peak restrictions time periods for comparative analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover). Univariate analysis used Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous outcomes, while chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical comparisons. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results: First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-restrictions, and 2304 post-peak-restrictions cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was found to be significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different. The proportion of cases that started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have not been impacted. There was no significant change in turnover time during peak restrictions relative to the pre-COVID-19 period (88 [100] minutes vs 85 [95] minutes), and turnover time has since remained unchanged (83 [87] minutes).

Conclusion: Our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak restrictions even while instituting advanced infection-control strategies. While there were significant changes, delays were relatively small in magnitude.

Keywords: operating room timing, hospital efficiency, socioeconomics, pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to major changes in patient care both from a surgical perspective and in regard to inpatient hospital course. Safety protocols nationwide have been implemented to protect both patients and providers. Some elements of surgical care have drastically changed, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and increased sterilization measures. Furloughs, layoffs, and reassignments due to the focus on nonelective and COVID-19–related cases challenged OR staffing and efficiency. Operating room staff with COVID-19 exposures or COVID-19 infections also caused last-minute changes in staffing. All of these scenarios can cause issues due to actual understaffing or due to staff members being pushed into highly specialized areas, such as neurosurgery, in which they have very little experience. A further obstacle to OR efficiency included policy changes involving PPE utilization, sterilization measures, and supply chain shortages of necessary resources such as PPE.

Neurosurgery in particular has been susceptible to COVID-19–related system-wide changes given operator proximity to the patient’s respiratory passages, frequency of emergent cases, and varying anesthetic needs, as well as the high level of specialization needed to perform neurosurgical care. Previous studies have shown a change in the makeup of neurosurgical patients seeking care, as well as in the acuity of neurological consult of these patients.1 A study in orthopedic surgery by Andreata et al demonstrated worsened OR efficiency, with significantly increased first-start and turnover times.2 In the COVID-19 era, OR quality and safety are crucially important to both patients and providers. Providing this safe and effective care in an efficient manner is important for optimal neurosurgical management in the long term.3 Moreover, the financial burden of implementing new protocols and standards can be compounded by additional financial losses due to reduced OR efficiency.

Methods

To analyze the effect of COVID-19 on neurosurgical OR efficiency, institutional perioperative databases at a single high-volume center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, was chosen as the onset of COVID-19 for analytic purposes, as this was the date when the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency. The 90-day periods before and after this date were used for comparative analysis for pre-COVID-19, peak COVID-19, and post-peak-restrictions time periods. The peak COVID-19 period was defined as the 90-day period following the initial onset of COVID-19 and the surge of cases. For comparison purposes, post-peak COVID-19 was defined as the months following the first peak until October 2021 (approximately 17 months). COVID-19 burden was determined using a COVID-19 single-institution census of confirmed cases by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for which the average number of cases of COVID-19 during a given month was determined. This number is a scaled trend, and a true number of COVID-19 cases in our hospital was not reported.

Neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases were included in the analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases, defined as the time from the patient leaving the room until the next patient entered the room. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover, which is a standard for our single-institution perioperative center). Statistical analyses, including data aggregation, were performed using R, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using an independent 2-sample t-test for interval variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

First-Start Time

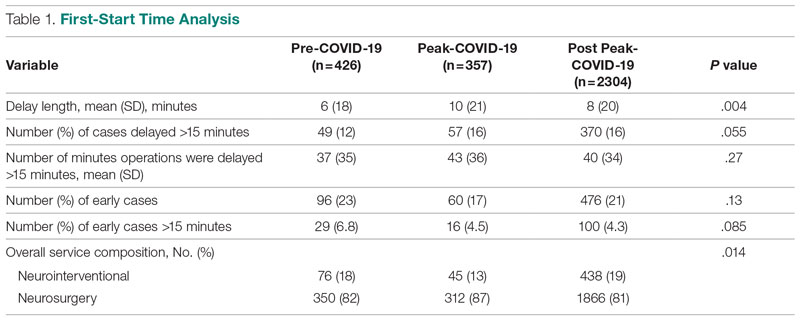

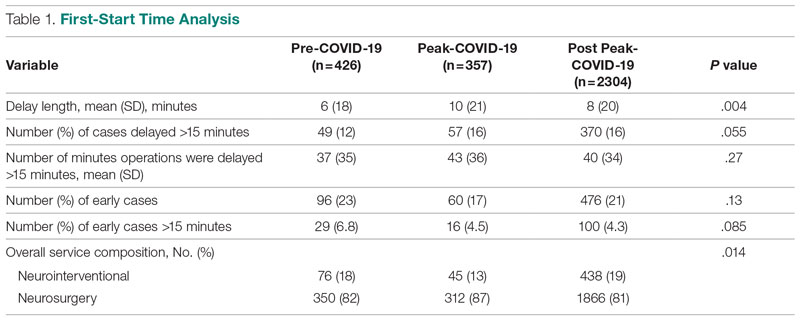

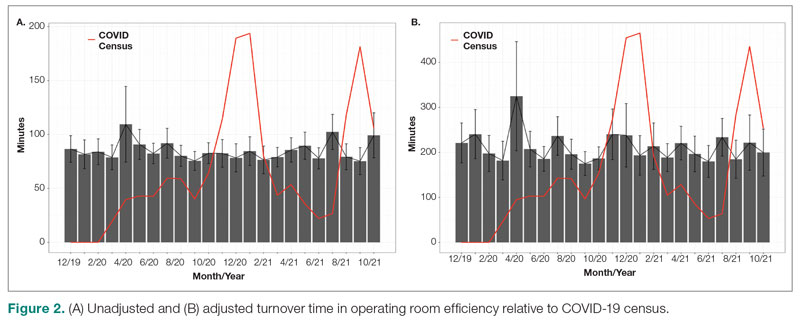

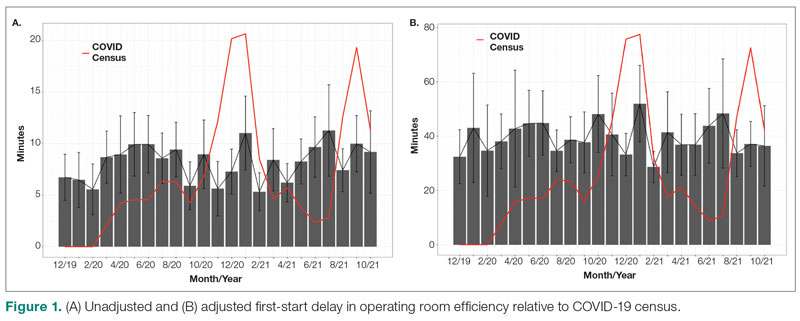

First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-COVID-19, and 2304 post-peak-COVID-19 cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004) (Table 1).

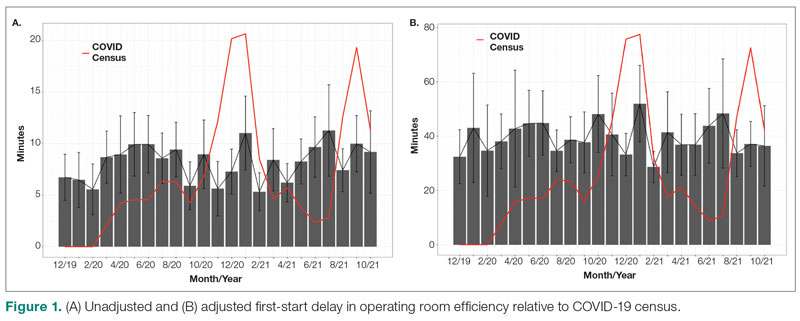

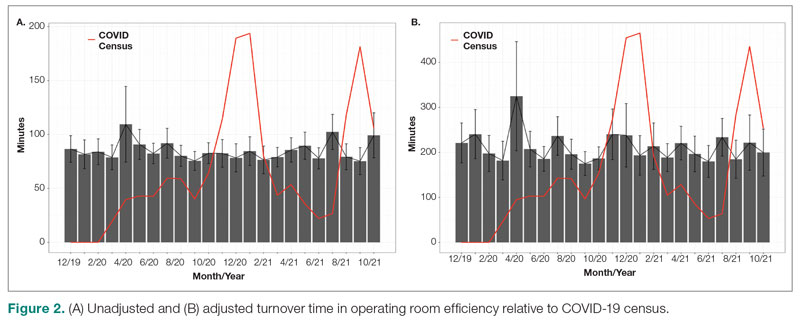

The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different, but they have been slightly higher since the onset of COVID-19. The proportion of cases that have started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have also trended down since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this difference was again not significant. The temporal relationship of first-start delay, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 1. The trend of increasing delay is loosely associated with the COVID-19 burden experienced by our hospital. The start of COVID-19 as well as both COVID-19 peaks have been associated with increased delays in our hospital.

Turnover Time

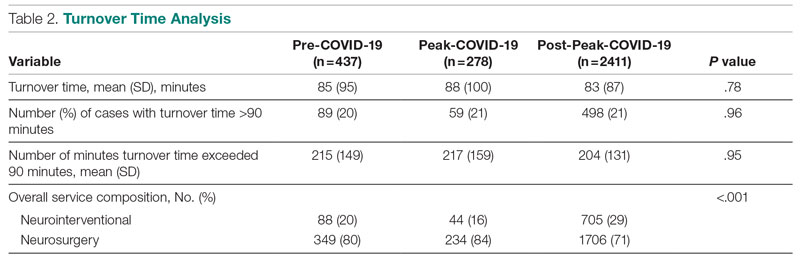

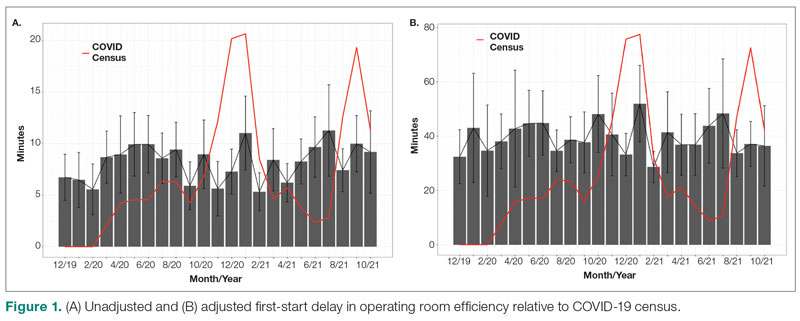

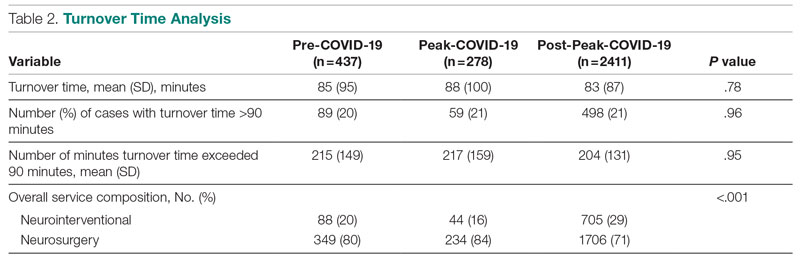

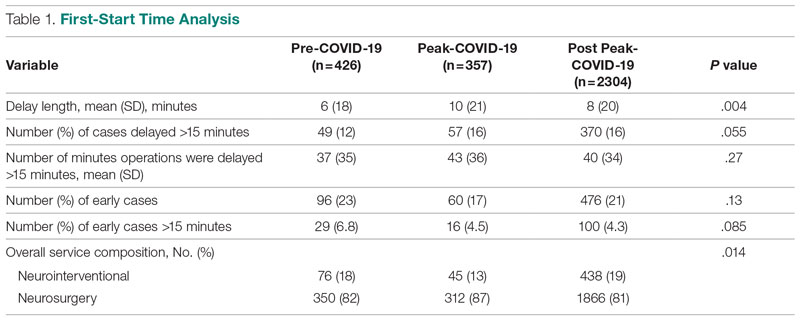

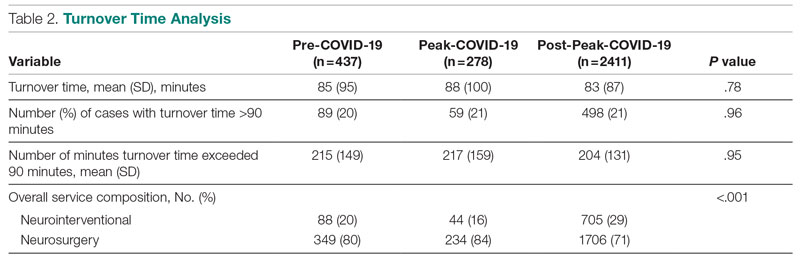

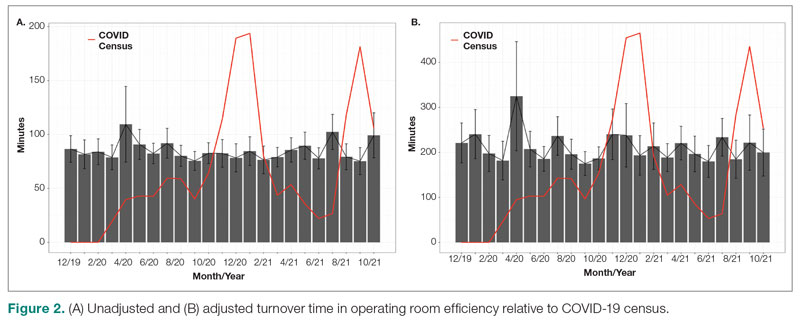

Turnover time was assessed in 437 pre-COVID-19, 278 peak-restrictions, and 2411 post-peak-restrictions cases. Turnover time during peak restrictions was not significantly different from pre-COVID-19 (88 [100] vs 85 [95]) and has since remained relatively unchanged (83 [87], P = .78). A similar trend held for comparisons of proportion of cases with turnover time past 90 minutes and average times past the 90-minute threshold (Table 2). The temporal relationship between COVID-19 burden and turnover time, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 2. Both figures demonstrate a slight initial increase in turnover time delay at the start of COVID-19, which stabilized with little variation thereafter.

Discussion

We analyzed the OR efficiency metrics of first-start and turnover time during the 90-day period before COVID-19 (pre-COVID-19), the 90 days following Tennessee declaring a state of emergency (peak COVID-19), and the time following this period (post-COVID-19) for all neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). We found a significant difference in unadjusted mean delay length in first-start time between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes for pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-COVID-19: 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). No significant increase in turnover time between cases was found between these 3 time periods. Based on metrics from first-start delay and turnover time, our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak COVID-19.

After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines recommending deferring elective procedures to conserve beds and PPE, VUMC made the decision to suspend all elective surgical procedures from March 18 to April 24, 2020. Prior research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated more than 400 types of surgical procedures with negatively impacted outcomes when compared to surgical outcomes from the same time frame in 2018 and 2019.4 For more than 20 of these types of procedures, there was a significant association between procedure delay and adverse patient outcomes.4 Testing protocols for patients prior to surgery varied throughout the pandemic based on vaccination status and type of procedure. Before vaccines became widely available, all patients were required to obtain a PCR SARS-CoV-2 test within 48 to 72 hours of the scheduled procedure. If the patient’s procedure was urgent and testing was not feasible, the patient was treated as a SARS-CoV-2–positive patient, which required all health care workers involved in the case to wear gowns, gloves, surgical masks, and eye protection. Testing patients preoperatively likely helped to maintain OR efficiency since not all patients received test results prior to the scheduled procedure, leading to cancellations of cases and therefore more staff available for fewer cases.

After vaccines became widely available to the public, testing requirements for patients preoperatively were relaxed, and only patients who were not fully vaccinated or severely immunocompromised were required to test prior to procedures. However, approximately 40% of the population in Tennessee was fully vaccinated in 2021, which reflects the patient population of VUMC.5 This means that many patients who received care at VUMC were still tested prior to procedures.

Adopting adequate safety protocols was found to be key for OR efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic since performing surgery increased the risk of infection for each health care worker in the OR.6 VUMC protocols identified procedures that required enhanced safety measures to prevent infection of health care workers and avoid staffing shortages, which would decrease OR efficiency. Protocols mandated that only anesthesia team members were allowed to be in the OR during intubation and extubation of patients, which could be one factor leading to increased delays and decreased efficiency for some institutions. Methods for neurosurgeons to decrease risk of infection in the OR include postponing all nonurgent cases, reappraising the necessity for general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, considering alternative surgical approaches that avoid the respiratory tract, and limiting the use of aerosol-generating instruments.7,8 VUMC’s success in implementing these protocols likely explains why our center was able to maintain OR efficiency throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study conducted by Andreata et al showed a significantly increased mean first-case delay and a nonsignificant increased turnover time in orthopedic surgeries in Northern Italy when comparing surgeries performed during the COVID-19 pandemic to those performed prior to COVID-19.2 Other studies have indicated a similar trend in decreased OR efficiency during COVID-19 in other areas around the world.9,10 These findings are not consistent with our own findings for neurosurgical and neuroendovascular surgeries at VUMC, and any change at our institution was relatively immaterial. Factors that threatened to change OR efficiency—but did not result in meaningful changes in our institutional experience—include delays due to pending COVID-19 test results, safety procedures such as PPE donning, and planning difficulties to ensure the existence of teams with non-overlapping providers in the case of a surgeon being infected.2,11-13

Globally, many surgery centers halted all elective surgeries during the initial COVID-19 spike to prevent a PPE shortage and mitigate risk of infection of patients and health care workers.8,12,14 However, there is no centralized definition of which neurosurgical procedures are elective, so that decision was made on a surgeon or center level, which could lead to variability in efficiency trends.14 One study on neurosurgical procedures during COVID-19 found a 30% decline in all cases and a 23% decline in emergent procedures, showing that the decrease in volume was not only due to cancellation of elective procedures.15 This decrease in elective and emergent surgeries created a backlog of surgeries as well as a loss in health care revenue, and caused many patients to go without adequate health care.10 Looking forward, it is imperative that surgical centers study trends in OR efficiency from COVID-19 and learn how to better maintain OR efficiency during future pandemic conditions to prevent a backlog of cases, loss of health care revenue, and decreased health care access.

Limitations

Our data are from a single center and therefore may not be representative of experiences of other hospitals due to different populations and different impacts from COVID-19. However, given our center’s high volume and diverse patient population, we believe our analysis highlights important trends in neurosurgery practice. Notably, data for patient and OR timing are digitally generated and are entered manually by nurses in the electronic medical record, making it prone to errors and variability. This is in our experience, and if any error is present, we believe it is minimal.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching effects on health care worldwide, including neurosurgical care. OR efficiency across the United States generally worsened given the stresses of supply chain issues, staffing shortages, and cancellations. At our institution, we were able to maintain OR efficiency during the known COVID-19 peaks until October 2021. Continually functional neurosurgical ORs are important in preventing delays in care and maintaining a steady revenue in order for hospitals and other health care entities to remain solvent. Further study of OR efficiency is needed for health care systems to prepare for future pandemics and other resource-straining events in order to provide optimal patient care.

Corresponding author: Campbell Liles, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Neurological Surgery, 1161 21st Ave. South, T4224 Medical Center North, Nashville, TN 37232-2380; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Koester SW, Catapano JS, Ma KL, et al. COVID-19 and neurosurgery consultation call volume at a single large tertiary center with a propensity- adjusted analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e768-e772. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.017

2. Andreata M, Faraldi M, Bucci E, Lombardi G, Zagra L. Operating room efficiency and timing during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in a referral orthopaedic hospital in Northern Italy. Int Orthop. 2020;44(12):2499-2504. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04772-x

3. Dexter F, Abouleish AE, Epstein RH, et al. Use of operating room information system data to predict the impact of reducing turnover times on staffing costs. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(4):1119-1126. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000082520.68800.79

4. Zheng NS, Warner JL, Osterman TJ, et al. A retrospective approach to evaluating potential adverse outcomes associated with delay of procedures for cardiovascular and cancer-related diagnoses in the context of COVID-19. J Biomed Inform. 2021;113:103657. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103657

5. Alcendor DJ. Targeting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in rural communities in Tennessee: implications for extending the COVID- 19 pandemic in the South. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1279. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111279

6. Perrone G, Giuffrida M, Bellini V, et al. Operating room setup: how to improve health care professionals safety during pandemic COVID- 19: a quality improvement study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(1):85-89. doi:10.1089/lap.2020.0592

7. Iorio-Morin C, Hodaie M, Sarica C, et al. Letter: the risk of COVID-19 infection during neurosurgical procedures: a review of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) modes of transmission and proposed neurosurgery-specific measures for mitigation. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(2):E178-E185. doi:10.1093/ neuros/nyaa157

8. Gupta P, Muthukumar N, Rajshekhar V, et al. Neurosurgery and neurology practices during the novel COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement from India. Neurol India. 2020;68(2):246-254. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.283130

9. Mercer ST, Agarwal R, Dayananda KSS, et al. A comparative study looking at trauma and orthopaedic operating efficiency in the COVID-19 era. Perioper Care Oper Room Manag. 2020;21:100142. doi:10.1016/j.pcorm.2020.100142

10. Rozario N, Rozario D. Can machine learning optimize the efficiency of the operating room in the era of COVID-19? Can J Surg. 2020;63(6):E527-E529. doi:10.1503/cjs.016520

11. Toh KHQ, Barazanchi A, Rajaretnam NS, et al. COVID-19 response by New Zealand general surgical departments in tertiary metropolitan hospitals. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(7-8):1352-1357. doi:10.1111/ ans.17044

12. Moorthy RK, Rajshekhar V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical practice in India: a survey on personal protective equipment usage, testing, and perceptions on disease transmission. Neurol India. 2020;68(5):1133-1138. doi:10.4103/0028- 3886.299173

13. Meneghini RM. Techniques and strategies to optimize efficiencies in the office and operating room: getting through the patient backlog and preserving hospital resources. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(7S):S49-S51. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.010

14. Jean WC, Ironside NT, Sack KD, et al. The impact of COVID- 19 on neurosurgeons and the strategy for triaging non-emergent operations: a global neurosurgery study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162(6):1229-1240. doi:10.1007/s00701-020- 04342-5

15. Raneri F, Rustemi O, Zambon G, et al. Neurosurgery in times of a pandemic: a survey of neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Veneto region in Italy. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;49(6):E9. doi:10.3171/2020.9.FOCUS20691

From the Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Stefan W. Koester, Puja Jagasia, and Drs. Liles, Dambrino IV, Feldman, and Chambless), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Drs. Mathews and Tiwari).

ABSTRACT

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has had broad effects on surgical care, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and newly implemented anti-infective measures. Our aim was to assess neurosurgery OR efficiency before the COVID-19 pandemic, during peak COVID-19, and during current times.

Methods: Institutional perioperative databases at a single, high-volume neurosurgical center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, the day that the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency, was chosen as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 90-day periods before and after this day were used to define the pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-peak restrictions time periods for comparative analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover). Univariate analysis used Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous outcomes, while chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical comparisons. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results: First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-restrictions, and 2304 post-peak-restrictions cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was found to be significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different. The proportion of cases that started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have not been impacted. There was no significant change in turnover time during peak restrictions relative to the pre-COVID-19 period (88 [100] minutes vs 85 [95] minutes), and turnover time has since remained unchanged (83 [87] minutes).

Conclusion: Our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak restrictions even while instituting advanced infection-control strategies. While there were significant changes, delays were relatively small in magnitude.

Keywords: operating room timing, hospital efficiency, socioeconomics, pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to major changes in patient care both from a surgical perspective and in regard to inpatient hospital course. Safety protocols nationwide have been implemented to protect both patients and providers. Some elements of surgical care have drastically changed, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and increased sterilization measures. Furloughs, layoffs, and reassignments due to the focus on nonelective and COVID-19–related cases challenged OR staffing and efficiency. Operating room staff with COVID-19 exposures or COVID-19 infections also caused last-minute changes in staffing. All of these scenarios can cause issues due to actual understaffing or due to staff members being pushed into highly specialized areas, such as neurosurgery, in which they have very little experience. A further obstacle to OR efficiency included policy changes involving PPE utilization, sterilization measures, and supply chain shortages of necessary resources such as PPE.

Neurosurgery in particular has been susceptible to COVID-19–related system-wide changes given operator proximity to the patient’s respiratory passages, frequency of emergent cases, and varying anesthetic needs, as well as the high level of specialization needed to perform neurosurgical care. Previous studies have shown a change in the makeup of neurosurgical patients seeking care, as well as in the acuity of neurological consult of these patients.1 A study in orthopedic surgery by Andreata et al demonstrated worsened OR efficiency, with significantly increased first-start and turnover times.2 In the COVID-19 era, OR quality and safety are crucially important to both patients and providers. Providing this safe and effective care in an efficient manner is important for optimal neurosurgical management in the long term.3 Moreover, the financial burden of implementing new protocols and standards can be compounded by additional financial losses due to reduced OR efficiency.

Methods

To analyze the effect of COVID-19 on neurosurgical OR efficiency, institutional perioperative databases at a single high-volume center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, was chosen as the onset of COVID-19 for analytic purposes, as this was the date when the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency. The 90-day periods before and after this date were used for comparative analysis for pre-COVID-19, peak COVID-19, and post-peak-restrictions time periods. The peak COVID-19 period was defined as the 90-day period following the initial onset of COVID-19 and the surge of cases. For comparison purposes, post-peak COVID-19 was defined as the months following the first peak until October 2021 (approximately 17 months). COVID-19 burden was determined using a COVID-19 single-institution census of confirmed cases by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for which the average number of cases of COVID-19 during a given month was determined. This number is a scaled trend, and a true number of COVID-19 cases in our hospital was not reported.

Neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases were included in the analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases, defined as the time from the patient leaving the room until the next patient entered the room. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover, which is a standard for our single-institution perioperative center). Statistical analyses, including data aggregation, were performed using R, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using an independent 2-sample t-test for interval variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

First-Start Time

First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-COVID-19, and 2304 post-peak-COVID-19 cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004) (Table 1).

The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different, but they have been slightly higher since the onset of COVID-19. The proportion of cases that have started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have also trended down since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this difference was again not significant. The temporal relationship of first-start delay, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 1. The trend of increasing delay is loosely associated with the COVID-19 burden experienced by our hospital. The start of COVID-19 as well as both COVID-19 peaks have been associated with increased delays in our hospital.

Turnover Time

Turnover time was assessed in 437 pre-COVID-19, 278 peak-restrictions, and 2411 post-peak-restrictions cases. Turnover time during peak restrictions was not significantly different from pre-COVID-19 (88 [100] vs 85 [95]) and has since remained relatively unchanged (83 [87], P = .78). A similar trend held for comparisons of proportion of cases with turnover time past 90 minutes and average times past the 90-minute threshold (Table 2). The temporal relationship between COVID-19 burden and turnover time, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 2. Both figures demonstrate a slight initial increase in turnover time delay at the start of COVID-19, which stabilized with little variation thereafter.

Discussion

We analyzed the OR efficiency metrics of first-start and turnover time during the 90-day period before COVID-19 (pre-COVID-19), the 90 days following Tennessee declaring a state of emergency (peak COVID-19), and the time following this period (post-COVID-19) for all neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). We found a significant difference in unadjusted mean delay length in first-start time between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes for pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-COVID-19: 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). No significant increase in turnover time between cases was found between these 3 time periods. Based on metrics from first-start delay and turnover time, our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak COVID-19.

After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines recommending deferring elective procedures to conserve beds and PPE, VUMC made the decision to suspend all elective surgical procedures from March 18 to April 24, 2020. Prior research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated more than 400 types of surgical procedures with negatively impacted outcomes when compared to surgical outcomes from the same time frame in 2018 and 2019.4 For more than 20 of these types of procedures, there was a significant association between procedure delay and adverse patient outcomes.4 Testing protocols for patients prior to surgery varied throughout the pandemic based on vaccination status and type of procedure. Before vaccines became widely available, all patients were required to obtain a PCR SARS-CoV-2 test within 48 to 72 hours of the scheduled procedure. If the patient’s procedure was urgent and testing was not feasible, the patient was treated as a SARS-CoV-2–positive patient, which required all health care workers involved in the case to wear gowns, gloves, surgical masks, and eye protection. Testing patients preoperatively likely helped to maintain OR efficiency since not all patients received test results prior to the scheduled procedure, leading to cancellations of cases and therefore more staff available for fewer cases.

After vaccines became widely available to the public, testing requirements for patients preoperatively were relaxed, and only patients who were not fully vaccinated or severely immunocompromised were required to test prior to procedures. However, approximately 40% of the population in Tennessee was fully vaccinated in 2021, which reflects the patient population of VUMC.5 This means that many patients who received care at VUMC were still tested prior to procedures.

Adopting adequate safety protocols was found to be key for OR efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic since performing surgery increased the risk of infection for each health care worker in the OR.6 VUMC protocols identified procedures that required enhanced safety measures to prevent infection of health care workers and avoid staffing shortages, which would decrease OR efficiency. Protocols mandated that only anesthesia team members were allowed to be in the OR during intubation and extubation of patients, which could be one factor leading to increased delays and decreased efficiency for some institutions. Methods for neurosurgeons to decrease risk of infection in the OR include postponing all nonurgent cases, reappraising the necessity for general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, considering alternative surgical approaches that avoid the respiratory tract, and limiting the use of aerosol-generating instruments.7,8 VUMC’s success in implementing these protocols likely explains why our center was able to maintain OR efficiency throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study conducted by Andreata et al showed a significantly increased mean first-case delay and a nonsignificant increased turnover time in orthopedic surgeries in Northern Italy when comparing surgeries performed during the COVID-19 pandemic to those performed prior to COVID-19.2 Other studies have indicated a similar trend in decreased OR efficiency during COVID-19 in other areas around the world.9,10 These findings are not consistent with our own findings for neurosurgical and neuroendovascular surgeries at VUMC, and any change at our institution was relatively immaterial. Factors that threatened to change OR efficiency—but did not result in meaningful changes in our institutional experience—include delays due to pending COVID-19 test results, safety procedures such as PPE donning, and planning difficulties to ensure the existence of teams with non-overlapping providers in the case of a surgeon being infected.2,11-13

Globally, many surgery centers halted all elective surgeries during the initial COVID-19 spike to prevent a PPE shortage and mitigate risk of infection of patients and health care workers.8,12,14 However, there is no centralized definition of which neurosurgical procedures are elective, so that decision was made on a surgeon or center level, which could lead to variability in efficiency trends.14 One study on neurosurgical procedures during COVID-19 found a 30% decline in all cases and a 23% decline in emergent procedures, showing that the decrease in volume was not only due to cancellation of elective procedures.15 This decrease in elective and emergent surgeries created a backlog of surgeries as well as a loss in health care revenue, and caused many patients to go without adequate health care.10 Looking forward, it is imperative that surgical centers study trends in OR efficiency from COVID-19 and learn how to better maintain OR efficiency during future pandemic conditions to prevent a backlog of cases, loss of health care revenue, and decreased health care access.

Limitations

Our data are from a single center and therefore may not be representative of experiences of other hospitals due to different populations and different impacts from COVID-19. However, given our center’s high volume and diverse patient population, we believe our analysis highlights important trends in neurosurgery practice. Notably, data for patient and OR timing are digitally generated and are entered manually by nurses in the electronic medical record, making it prone to errors and variability. This is in our experience, and if any error is present, we believe it is minimal.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching effects on health care worldwide, including neurosurgical care. OR efficiency across the United States generally worsened given the stresses of supply chain issues, staffing shortages, and cancellations. At our institution, we were able to maintain OR efficiency during the known COVID-19 peaks until October 2021. Continually functional neurosurgical ORs are important in preventing delays in care and maintaining a steady revenue in order for hospitals and other health care entities to remain solvent. Further study of OR efficiency is needed for health care systems to prepare for future pandemics and other resource-straining events in order to provide optimal patient care.

Corresponding author: Campbell Liles, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Neurological Surgery, 1161 21st Ave. South, T4224 Medical Center North, Nashville, TN 37232-2380; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Stefan W. Koester, Puja Jagasia, and Drs. Liles, Dambrino IV, Feldman, and Chambless), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN (Drs. Mathews and Tiwari).

ABSTRACT

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has had broad effects on surgical care, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and newly implemented anti-infective measures. Our aim was to assess neurosurgery OR efficiency before the COVID-19 pandemic, during peak COVID-19, and during current times.

Methods: Institutional perioperative databases at a single, high-volume neurosurgical center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, the day that the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency, was chosen as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 90-day periods before and after this day were used to define the pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-peak restrictions time periods for comparative analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover). Univariate analysis used Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous outcomes, while chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical comparisons. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results: First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-restrictions, and 2304 post-peak-restrictions cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was found to be significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different. The proportion of cases that started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have not been impacted. There was no significant change in turnover time during peak restrictions relative to the pre-COVID-19 period (88 [100] minutes vs 85 [95] minutes), and turnover time has since remained unchanged (83 [87] minutes).

Conclusion: Our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak restrictions even while instituting advanced infection-control strategies. While there were significant changes, delays were relatively small in magnitude.

Keywords: operating room timing, hospital efficiency, socioeconomics, pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to major changes in patient care both from a surgical perspective and in regard to inpatient hospital course. Safety protocols nationwide have been implemented to protect both patients and providers. Some elements of surgical care have drastically changed, including operating room (OR) staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, and increased sterilization measures. Furloughs, layoffs, and reassignments due to the focus on nonelective and COVID-19–related cases challenged OR staffing and efficiency. Operating room staff with COVID-19 exposures or COVID-19 infections also caused last-minute changes in staffing. All of these scenarios can cause issues due to actual understaffing or due to staff members being pushed into highly specialized areas, such as neurosurgery, in which they have very little experience. A further obstacle to OR efficiency included policy changes involving PPE utilization, sterilization measures, and supply chain shortages of necessary resources such as PPE.

Neurosurgery in particular has been susceptible to COVID-19–related system-wide changes given operator proximity to the patient’s respiratory passages, frequency of emergent cases, and varying anesthetic needs, as well as the high level of specialization needed to perform neurosurgical care. Previous studies have shown a change in the makeup of neurosurgical patients seeking care, as well as in the acuity of neurological consult of these patients.1 A study in orthopedic surgery by Andreata et al demonstrated worsened OR efficiency, with significantly increased first-start and turnover times.2 In the COVID-19 era, OR quality and safety are crucially important to both patients and providers. Providing this safe and effective care in an efficient manner is important for optimal neurosurgical management in the long term.3 Moreover, the financial burden of implementing new protocols and standards can be compounded by additional financial losses due to reduced OR efficiency.

Methods

To analyze the effect of COVID-19 on neurosurgical OR efficiency, institutional perioperative databases at a single high-volume center were queried for operations performed from December 2019 until October 2021. March 12, 2020, was chosen as the onset of COVID-19 for analytic purposes, as this was the date when the state of Tennessee declared a state of emergency. The 90-day periods before and after this date were used for comparative analysis for pre-COVID-19, peak COVID-19, and post-peak-restrictions time periods. The peak COVID-19 period was defined as the 90-day period following the initial onset of COVID-19 and the surge of cases. For comparison purposes, post-peak COVID-19 was defined as the months following the first peak until October 2021 (approximately 17 months). COVID-19 burden was determined using a COVID-19 single-institution census of confirmed cases by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for which the average number of cases of COVID-19 during a given month was determined. This number is a scaled trend, and a true number of COVID-19 cases in our hospital was not reported.

Neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases were included in the analysis. Outcomes included delay in first-start and OR turnover time between neurosurgical cases, defined as the time from the patient leaving the room until the next patient entered the room. Preset threshold times were used in analyses to adjust for normal leniency in OR scheduling (15 minutes for first start and 90 minutes for turnover, which is a standard for our single-institution perioperative center). Statistical analyses, including data aggregation, were performed using R, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using an independent 2-sample t-test for interval variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

First-Start Time

First-start time was analyzed in 426 pre-COVID-19, 357 peak-COVID-19, and 2304 post-peak-COVID-19 cases. The unadjusted mean delay length was significantly different between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes, 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004) (Table 1).

The adjusted average delay length and proportion of cases delayed beyond the 15-minute threshold were not significantly different, but they have been slightly higher since the onset of COVID-19. The proportion of cases that have started early, as well as significantly early past a 15-minute threshold, have also trended down since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this difference was again not significant. The temporal relationship of first-start delay, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 1. The trend of increasing delay is loosely associated with the COVID-19 burden experienced by our hospital. The start of COVID-19 as well as both COVID-19 peaks have been associated with increased delays in our hospital.

Turnover Time

Turnover time was assessed in 437 pre-COVID-19, 278 peak-restrictions, and 2411 post-peak-restrictions cases. Turnover time during peak restrictions was not significantly different from pre-COVID-19 (88 [100] vs 85 [95]) and has since remained relatively unchanged (83 [87], P = .78). A similar trend held for comparisons of proportion of cases with turnover time past 90 minutes and average times past the 90-minute threshold (Table 2). The temporal relationship between COVID-19 burden and turnover time, both unadjusted and adjusted, from December 2019 to October 2021 is shown in Figure 2. Both figures demonstrate a slight initial increase in turnover time delay at the start of COVID-19, which stabilized with little variation thereafter.

Discussion

We analyzed the OR efficiency metrics of first-start and turnover time during the 90-day period before COVID-19 (pre-COVID-19), the 90 days following Tennessee declaring a state of emergency (peak COVID-19), and the time following this period (post-COVID-19) for all neurosurgical and neuroendovascular cases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). We found a significant difference in unadjusted mean delay length in first-start time between the time periods, but the magnitude of increase in minutes was immaterial (mean [SD] minutes for pre-COVID-19, peak-COVID-19, and post-COVID-19: 6 [18] vs 10 [21] vs 8 [20], respectively; P = .004). No significant increase in turnover time between cases was found between these 3 time periods. Based on metrics from first-start delay and turnover time, our center was able to maintain OR efficiency before, during, and after peak COVID-19.

After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines recommending deferring elective procedures to conserve beds and PPE, VUMC made the decision to suspend all elective surgical procedures from March 18 to April 24, 2020. Prior research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated more than 400 types of surgical procedures with negatively impacted outcomes when compared to surgical outcomes from the same time frame in 2018 and 2019.4 For more than 20 of these types of procedures, there was a significant association between procedure delay and adverse patient outcomes.4 Testing protocols for patients prior to surgery varied throughout the pandemic based on vaccination status and type of procedure. Before vaccines became widely available, all patients were required to obtain a PCR SARS-CoV-2 test within 48 to 72 hours of the scheduled procedure. If the patient’s procedure was urgent and testing was not feasible, the patient was treated as a SARS-CoV-2–positive patient, which required all health care workers involved in the case to wear gowns, gloves, surgical masks, and eye protection. Testing patients preoperatively likely helped to maintain OR efficiency since not all patients received test results prior to the scheduled procedure, leading to cancellations of cases and therefore more staff available for fewer cases.

After vaccines became widely available to the public, testing requirements for patients preoperatively were relaxed, and only patients who were not fully vaccinated or severely immunocompromised were required to test prior to procedures. However, approximately 40% of the population in Tennessee was fully vaccinated in 2021, which reflects the patient population of VUMC.5 This means that many patients who received care at VUMC were still tested prior to procedures.

Adopting adequate safety protocols was found to be key for OR efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic since performing surgery increased the risk of infection for each health care worker in the OR.6 VUMC protocols identified procedures that required enhanced safety measures to prevent infection of health care workers and avoid staffing shortages, which would decrease OR efficiency. Protocols mandated that only anesthesia team members were allowed to be in the OR during intubation and extubation of patients, which could be one factor leading to increased delays and decreased efficiency for some institutions. Methods for neurosurgeons to decrease risk of infection in the OR include postponing all nonurgent cases, reappraising the necessity for general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, considering alternative surgical approaches that avoid the respiratory tract, and limiting the use of aerosol-generating instruments.7,8 VUMC’s success in implementing these protocols likely explains why our center was able to maintain OR efficiency throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study conducted by Andreata et al showed a significantly increased mean first-case delay and a nonsignificant increased turnover time in orthopedic surgeries in Northern Italy when comparing surgeries performed during the COVID-19 pandemic to those performed prior to COVID-19.2 Other studies have indicated a similar trend in decreased OR efficiency during COVID-19 in other areas around the world.9,10 These findings are not consistent with our own findings for neurosurgical and neuroendovascular surgeries at VUMC, and any change at our institution was relatively immaterial. Factors that threatened to change OR efficiency—but did not result in meaningful changes in our institutional experience—include delays due to pending COVID-19 test results, safety procedures such as PPE donning, and planning difficulties to ensure the existence of teams with non-overlapping providers in the case of a surgeon being infected.2,11-13

Globally, many surgery centers halted all elective surgeries during the initial COVID-19 spike to prevent a PPE shortage and mitigate risk of infection of patients and health care workers.8,12,14 However, there is no centralized definition of which neurosurgical procedures are elective, so that decision was made on a surgeon or center level, which could lead to variability in efficiency trends.14 One study on neurosurgical procedures during COVID-19 found a 30% decline in all cases and a 23% decline in emergent procedures, showing that the decrease in volume was not only due to cancellation of elective procedures.15 This decrease in elective and emergent surgeries created a backlog of surgeries as well as a loss in health care revenue, and caused many patients to go without adequate health care.10 Looking forward, it is imperative that surgical centers study trends in OR efficiency from COVID-19 and learn how to better maintain OR efficiency during future pandemic conditions to prevent a backlog of cases, loss of health care revenue, and decreased health care access.

Limitations

Our data are from a single center and therefore may not be representative of experiences of other hospitals due to different populations and different impacts from COVID-19. However, given our center’s high volume and diverse patient population, we believe our analysis highlights important trends in neurosurgery practice. Notably, data for patient and OR timing are digitally generated and are entered manually by nurses in the electronic medical record, making it prone to errors and variability. This is in our experience, and if any error is present, we believe it is minimal.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching effects on health care worldwide, including neurosurgical care. OR efficiency across the United States generally worsened given the stresses of supply chain issues, staffing shortages, and cancellations. At our institution, we were able to maintain OR efficiency during the known COVID-19 peaks until October 2021. Continually functional neurosurgical ORs are important in preventing delays in care and maintaining a steady revenue in order for hospitals and other health care entities to remain solvent. Further study of OR efficiency is needed for health care systems to prepare for future pandemics and other resource-straining events in order to provide optimal patient care.

Corresponding author: Campbell Liles, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Neurological Surgery, 1161 21st Ave. South, T4224 Medical Center North, Nashville, TN 37232-2380; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Koester SW, Catapano JS, Ma KL, et al. COVID-19 and neurosurgery consultation call volume at a single large tertiary center with a propensity- adjusted analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e768-e772. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.017

2. Andreata M, Faraldi M, Bucci E, Lombardi G, Zagra L. Operating room efficiency and timing during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in a referral orthopaedic hospital in Northern Italy. Int Orthop. 2020;44(12):2499-2504. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04772-x

3. Dexter F, Abouleish AE, Epstein RH, et al. Use of operating room information system data to predict the impact of reducing turnover times on staffing costs. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(4):1119-1126. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000082520.68800.79

4. Zheng NS, Warner JL, Osterman TJ, et al. A retrospective approach to evaluating potential adverse outcomes associated with delay of procedures for cardiovascular and cancer-related diagnoses in the context of COVID-19. J Biomed Inform. 2021;113:103657. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103657

5. Alcendor DJ. Targeting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in rural communities in Tennessee: implications for extending the COVID- 19 pandemic in the South. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1279. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111279

6. Perrone G, Giuffrida M, Bellini V, et al. Operating room setup: how to improve health care professionals safety during pandemic COVID- 19: a quality improvement study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(1):85-89. doi:10.1089/lap.2020.0592

7. Iorio-Morin C, Hodaie M, Sarica C, et al. Letter: the risk of COVID-19 infection during neurosurgical procedures: a review of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) modes of transmission and proposed neurosurgery-specific measures for mitigation. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(2):E178-E185. doi:10.1093/ neuros/nyaa157

8. Gupta P, Muthukumar N, Rajshekhar V, et al. Neurosurgery and neurology practices during the novel COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement from India. Neurol India. 2020;68(2):246-254. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.283130

9. Mercer ST, Agarwal R, Dayananda KSS, et al. A comparative study looking at trauma and orthopaedic operating efficiency in the COVID-19 era. Perioper Care Oper Room Manag. 2020;21:100142. doi:10.1016/j.pcorm.2020.100142

10. Rozario N, Rozario D. Can machine learning optimize the efficiency of the operating room in the era of COVID-19? Can J Surg. 2020;63(6):E527-E529. doi:10.1503/cjs.016520

11. Toh KHQ, Barazanchi A, Rajaretnam NS, et al. COVID-19 response by New Zealand general surgical departments in tertiary metropolitan hospitals. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(7-8):1352-1357. doi:10.1111/ ans.17044

12. Moorthy RK, Rajshekhar V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical practice in India: a survey on personal protective equipment usage, testing, and perceptions on disease transmission. Neurol India. 2020;68(5):1133-1138. doi:10.4103/0028- 3886.299173

13. Meneghini RM. Techniques and strategies to optimize efficiencies in the office and operating room: getting through the patient backlog and preserving hospital resources. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(7S):S49-S51. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.010

14. Jean WC, Ironside NT, Sack KD, et al. The impact of COVID- 19 on neurosurgeons and the strategy for triaging non-emergent operations: a global neurosurgery study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162(6):1229-1240. doi:10.1007/s00701-020- 04342-5

15. Raneri F, Rustemi O, Zambon G, et al. Neurosurgery in times of a pandemic: a survey of neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Veneto region in Italy. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;49(6):E9. doi:10.3171/2020.9.FOCUS20691

1. Koester SW, Catapano JS, Ma KL, et al. COVID-19 and neurosurgery consultation call volume at a single large tertiary center with a propensity- adjusted analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e768-e772. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.017

2. Andreata M, Faraldi M, Bucci E, Lombardi G, Zagra L. Operating room efficiency and timing during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in a referral orthopaedic hospital in Northern Italy. Int Orthop. 2020;44(12):2499-2504. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04772-x

3. Dexter F, Abouleish AE, Epstein RH, et al. Use of operating room information system data to predict the impact of reducing turnover times on staffing costs. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(4):1119-1126. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000082520.68800.79

4. Zheng NS, Warner JL, Osterman TJ, et al. A retrospective approach to evaluating potential adverse outcomes associated with delay of procedures for cardiovascular and cancer-related diagnoses in the context of COVID-19. J Biomed Inform. 2021;113:103657. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103657

5. Alcendor DJ. Targeting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in rural communities in Tennessee: implications for extending the COVID- 19 pandemic in the South. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1279. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111279

6. Perrone G, Giuffrida M, Bellini V, et al. Operating room setup: how to improve health care professionals safety during pandemic COVID- 19: a quality improvement study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;31(1):85-89. doi:10.1089/lap.2020.0592

7. Iorio-Morin C, Hodaie M, Sarica C, et al. Letter: the risk of COVID-19 infection during neurosurgical procedures: a review of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) modes of transmission and proposed neurosurgery-specific measures for mitigation. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(2):E178-E185. doi:10.1093/ neuros/nyaa157

8. Gupta P, Muthukumar N, Rajshekhar V, et al. Neurosurgery and neurology practices during the novel COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement from India. Neurol India. 2020;68(2):246-254. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.283130

9. Mercer ST, Agarwal R, Dayananda KSS, et al. A comparative study looking at trauma and orthopaedic operating efficiency in the COVID-19 era. Perioper Care Oper Room Manag. 2020;21:100142. doi:10.1016/j.pcorm.2020.100142

10. Rozario N, Rozario D. Can machine learning optimize the efficiency of the operating room in the era of COVID-19? Can J Surg. 2020;63(6):E527-E529. doi:10.1503/cjs.016520

11. Toh KHQ, Barazanchi A, Rajaretnam NS, et al. COVID-19 response by New Zealand general surgical departments in tertiary metropolitan hospitals. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(7-8):1352-1357. doi:10.1111/ ans.17044

12. Moorthy RK, Rajshekhar V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical practice in India: a survey on personal protective equipment usage, testing, and perceptions on disease transmission. Neurol India. 2020;68(5):1133-1138. doi:10.4103/0028- 3886.299173

13. Meneghini RM. Techniques and strategies to optimize efficiencies in the office and operating room: getting through the patient backlog and preserving hospital resources. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(7S):S49-S51. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.010

14. Jean WC, Ironside NT, Sack KD, et al. The impact of COVID- 19 on neurosurgeons and the strategy for triaging non-emergent operations: a global neurosurgery study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162(6):1229-1240. doi:10.1007/s00701-020- 04342-5

15. Raneri F, Rustemi O, Zambon G, et al. Neurosurgery in times of a pandemic: a survey of neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Veneto region in Italy. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;49(6):E9. doi:10.3171/2020.9.FOCUS20691

Anesthetic Choices and Postoperative Delirium Incidence: Propofol vs Sevoflurane

Study 1 Overview (Chang et al)

Objective: To assess the incidence of postoperative delirium (POD) following propofol- vs sevoflurane-based anesthesia in geriatric spine surgery patients.

Design: Retrospective, single-blinded observational study of propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia cohorts.

Setting and participants: Patients eligible for this study were aged 65 years or older admitted to the SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). All patients underwent general anesthesia either via intravenous propofol or inhalational sevoflurane for spine surgery between January 2015 and December 2019. Patients were retrospectively identified via electronic medical records. Patient exclusion criteria included preoperative delirium, history of dementia, psychiatric disease, alcoholism, hepatic or renal dysfunction, postoperative mechanical ventilation dependence, other surgery within the recent 6 months, maintenance of intraoperative anesthesia with combined anesthetics, or incomplete medical record.