User login

Preoperative preparation for gender-affirming vaginoplasty surgery

The field of gender-affirming surgery is one of the fastest growing surgical specialties in the country. Within the last few years, the number of procedures has increased markedly – with a total of 16,353 performed in 2020 compared with 8,304 in 2017.1,2 As the number of surgeries increases, so does the need for a standardized approach to preoperative evaluation and patient preparation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery for transfeminine individuals encompasses a spectrum of procedures that includes removal of the testicles (orchiectomy), creation of a neovaginal canal (full-depth vaginoplasty), and creation of external vulvar structures without a vaginal canal (zero-depth vaginoplasty). Each of these requires different levels of preoperative preparedness and medical optimization, and has unique postoperative challenges. Often, these postoperative complications can be mitigated with adequate patient education.

Many centers that offer genital gender-affirming surgery have a multidisciplinary team composed of a social worker, mental health providers, care coordinators, primary care providers, and surgeons. This team is essential to providing supportive services within their respective scope of practices.

The role of the mental health provider cannot be understated. While the updated standards of care from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health no longer require two letters from mental health providers prior to genital surgery, it is important to recognize that many insurance companies have not yet updated their policies and still require two letters. Even when insurance companies adjust their policies to reflect current standards, a mental health assessment is still necessary to determine if patients have any mental health issues that could negatively affect their surgical outcome.3 Furthermore, a continued relationship with a mental health provider is beneficial for patients as they go through a stressful and life-changing procedure.4

As with any surgery, understanding patient goals and expectations is a key element in achieving optimal patient satisfaction. Patients with high esthetic or functional expectations experience higher rates of disappointment after surgery and have more difficulty coping with complications.5

Decisions about proceeding with a particular type of genital surgery should consider a patient’s desire to have vaginal-receptive intercourse, their commitment to dilation, financial stability, a safe environment for recovery, a support network, and the ability to understand and cope with potential complications.4 Patients will present with a wide variety of educational backgrounds and medical literacy, and will have differing intellectual capabilities.4 Consultations should take into account potential challenges these factors may play in patients’ ability to understand this complex surgery.

An adequate amount of time should be allotted to addressing these challenges. In my practice, a consultation for a gender-affirming genital surgery takes approximately 60 minutes. A preoperative packet with information is mailed to the patient ahead of time that will be reviewed at the time of the visit. During the consultation, I utilize a visual presentation that details the preoperative requirements and different types of surgical procedures, shows preoperative and postoperative surgical results, and discusses potential complications. Before the consultation, I advise that patients bring a support person (ideally the person who will assist in postoperative care) and a list of questions that they may have.

Both full- and shallow-depth procedures are reviewed at the time of initial consultation. For patients who seek a full-depth vaginoplasty procedure, it is important to determine whether patients are committed to dilation and have a safe, supportive environment to do so. Patients may have physical limitations, such as obesity or mobility issues, that could make dilation difficult or even impossible. Patients may not have stable housing, may experience financial restrictions that would impede their ability to purchase necessary supplies, and lack a support person who can care for them in the immediate postoperative period. Many patients are unaware of the importance these social factors play in a successful outcome. Social workers and care coordinators are important resources when these challenges are encountered.

Medical optimization is not unlike other gynecologic procedures with a few exceptions. Obesity, diabetes, and smoking play larger roles in surgical complications than in other surgeries as vaginoplasty techniques use pedicled flaps that rely on adequate blood supply. Obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, and smoking are associated with increased rates of wound infection, poor wound healing, and graft loss. Smoking cessation for 8 weeks prior to surgery and for 4 weeks afterward is mandatory.

For patients with a history of smoking, a nicotine test is performed within 4 weeks of surgery. Many surgeons have body mass index requirements, typically ranging between 20 and 30 kg/m2, despite limited data. This paradigm is shifting to consider body fat distribution rather than BMI alone. Extensive body fat in the mons or groin area can increase the difficulty of pelvic floor dissection during surgery and impede visualization for dilation in the postoperative period. There are reports of patients dilating into their rectum or neourethra, which can have catastrophic consequences. For these patients, a zero-depth vaginoplasty or orchiectomy may initially be a safer option.

Many patients are justifiably excited to undergo the procedures as quality of life is typically improved after surgery. However, even with adequate counseling, many patients often underestimate the extensive recovery process. This surgical procedure requires extensive planning and adequate resources.4 Patients must be able to take off from work for prolonged periods of time (typically 6 weeks), which can serve as a source of financial stress. To maintain the integrity of suture lines in the genital region, prolonged or limited mobilization is recommended. This can create boredom and forces patients to rely on a caregiver for activities of daily living, such as household chores, cooking meals, and transportation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery is not only a complex surgical procedure but also requires extensive preoperative education and postoperative support. As this field continues to grow, patients, providers, and caregivers should work toward further developing a collaborative care model to optimize surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2020.

2. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2017.

3. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. Version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 23(S1):S1-S258. doi :10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

4. Penkin A et al. In: Nikolavsky D and Blakely SA, eds. Urological care for the transgender patient: A comprehensive guide. Switzerland: Springer, 2021:37-44.

5. Waljee J et al. Surgery. 2014;155:799-808.

The field of gender-affirming surgery is one of the fastest growing surgical specialties in the country. Within the last few years, the number of procedures has increased markedly – with a total of 16,353 performed in 2020 compared with 8,304 in 2017.1,2 As the number of surgeries increases, so does the need for a standardized approach to preoperative evaluation and patient preparation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery for transfeminine individuals encompasses a spectrum of procedures that includes removal of the testicles (orchiectomy), creation of a neovaginal canal (full-depth vaginoplasty), and creation of external vulvar structures without a vaginal canal (zero-depth vaginoplasty). Each of these requires different levels of preoperative preparedness and medical optimization, and has unique postoperative challenges. Often, these postoperative complications can be mitigated with adequate patient education.

Many centers that offer genital gender-affirming surgery have a multidisciplinary team composed of a social worker, mental health providers, care coordinators, primary care providers, and surgeons. This team is essential to providing supportive services within their respective scope of practices.

The role of the mental health provider cannot be understated. While the updated standards of care from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health no longer require two letters from mental health providers prior to genital surgery, it is important to recognize that many insurance companies have not yet updated their policies and still require two letters. Even when insurance companies adjust their policies to reflect current standards, a mental health assessment is still necessary to determine if patients have any mental health issues that could negatively affect their surgical outcome.3 Furthermore, a continued relationship with a mental health provider is beneficial for patients as they go through a stressful and life-changing procedure.4

As with any surgery, understanding patient goals and expectations is a key element in achieving optimal patient satisfaction. Patients with high esthetic or functional expectations experience higher rates of disappointment after surgery and have more difficulty coping with complications.5

Decisions about proceeding with a particular type of genital surgery should consider a patient’s desire to have vaginal-receptive intercourse, their commitment to dilation, financial stability, a safe environment for recovery, a support network, and the ability to understand and cope with potential complications.4 Patients will present with a wide variety of educational backgrounds and medical literacy, and will have differing intellectual capabilities.4 Consultations should take into account potential challenges these factors may play in patients’ ability to understand this complex surgery.

An adequate amount of time should be allotted to addressing these challenges. In my practice, a consultation for a gender-affirming genital surgery takes approximately 60 minutes. A preoperative packet with information is mailed to the patient ahead of time that will be reviewed at the time of the visit. During the consultation, I utilize a visual presentation that details the preoperative requirements and different types of surgical procedures, shows preoperative and postoperative surgical results, and discusses potential complications. Before the consultation, I advise that patients bring a support person (ideally the person who will assist in postoperative care) and a list of questions that they may have.

Both full- and shallow-depth procedures are reviewed at the time of initial consultation. For patients who seek a full-depth vaginoplasty procedure, it is important to determine whether patients are committed to dilation and have a safe, supportive environment to do so. Patients may have physical limitations, such as obesity or mobility issues, that could make dilation difficult or even impossible. Patients may not have stable housing, may experience financial restrictions that would impede their ability to purchase necessary supplies, and lack a support person who can care for them in the immediate postoperative period. Many patients are unaware of the importance these social factors play in a successful outcome. Social workers and care coordinators are important resources when these challenges are encountered.

Medical optimization is not unlike other gynecologic procedures with a few exceptions. Obesity, diabetes, and smoking play larger roles in surgical complications than in other surgeries as vaginoplasty techniques use pedicled flaps that rely on adequate blood supply. Obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, and smoking are associated with increased rates of wound infection, poor wound healing, and graft loss. Smoking cessation for 8 weeks prior to surgery and for 4 weeks afterward is mandatory.

For patients with a history of smoking, a nicotine test is performed within 4 weeks of surgery. Many surgeons have body mass index requirements, typically ranging between 20 and 30 kg/m2, despite limited data. This paradigm is shifting to consider body fat distribution rather than BMI alone. Extensive body fat in the mons or groin area can increase the difficulty of pelvic floor dissection during surgery and impede visualization for dilation in the postoperative period. There are reports of patients dilating into their rectum or neourethra, which can have catastrophic consequences. For these patients, a zero-depth vaginoplasty or orchiectomy may initially be a safer option.

Many patients are justifiably excited to undergo the procedures as quality of life is typically improved after surgery. However, even with adequate counseling, many patients often underestimate the extensive recovery process. This surgical procedure requires extensive planning and adequate resources.4 Patients must be able to take off from work for prolonged periods of time (typically 6 weeks), which can serve as a source of financial stress. To maintain the integrity of suture lines in the genital region, prolonged or limited mobilization is recommended. This can create boredom and forces patients to rely on a caregiver for activities of daily living, such as household chores, cooking meals, and transportation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery is not only a complex surgical procedure but also requires extensive preoperative education and postoperative support. As this field continues to grow, patients, providers, and caregivers should work toward further developing a collaborative care model to optimize surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2020.

2. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2017.

3. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. Version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 23(S1):S1-S258. doi :10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

4. Penkin A et al. In: Nikolavsky D and Blakely SA, eds. Urological care for the transgender patient: A comprehensive guide. Switzerland: Springer, 2021:37-44.

5. Waljee J et al. Surgery. 2014;155:799-808.

The field of gender-affirming surgery is one of the fastest growing surgical specialties in the country. Within the last few years, the number of procedures has increased markedly – with a total of 16,353 performed in 2020 compared with 8,304 in 2017.1,2 As the number of surgeries increases, so does the need for a standardized approach to preoperative evaluation and patient preparation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery for transfeminine individuals encompasses a spectrum of procedures that includes removal of the testicles (orchiectomy), creation of a neovaginal canal (full-depth vaginoplasty), and creation of external vulvar structures without a vaginal canal (zero-depth vaginoplasty). Each of these requires different levels of preoperative preparedness and medical optimization, and has unique postoperative challenges. Often, these postoperative complications can be mitigated with adequate patient education.

Many centers that offer genital gender-affirming surgery have a multidisciplinary team composed of a social worker, mental health providers, care coordinators, primary care providers, and surgeons. This team is essential to providing supportive services within their respective scope of practices.

The role of the mental health provider cannot be understated. While the updated standards of care from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health no longer require two letters from mental health providers prior to genital surgery, it is important to recognize that many insurance companies have not yet updated their policies and still require two letters. Even when insurance companies adjust their policies to reflect current standards, a mental health assessment is still necessary to determine if patients have any mental health issues that could negatively affect their surgical outcome.3 Furthermore, a continued relationship with a mental health provider is beneficial for patients as they go through a stressful and life-changing procedure.4

As with any surgery, understanding patient goals and expectations is a key element in achieving optimal patient satisfaction. Patients with high esthetic or functional expectations experience higher rates of disappointment after surgery and have more difficulty coping with complications.5

Decisions about proceeding with a particular type of genital surgery should consider a patient’s desire to have vaginal-receptive intercourse, their commitment to dilation, financial stability, a safe environment for recovery, a support network, and the ability to understand and cope with potential complications.4 Patients will present with a wide variety of educational backgrounds and medical literacy, and will have differing intellectual capabilities.4 Consultations should take into account potential challenges these factors may play in patients’ ability to understand this complex surgery.

An adequate amount of time should be allotted to addressing these challenges. In my practice, a consultation for a gender-affirming genital surgery takes approximately 60 minutes. A preoperative packet with information is mailed to the patient ahead of time that will be reviewed at the time of the visit. During the consultation, I utilize a visual presentation that details the preoperative requirements and different types of surgical procedures, shows preoperative and postoperative surgical results, and discusses potential complications. Before the consultation, I advise that patients bring a support person (ideally the person who will assist in postoperative care) and a list of questions that they may have.

Both full- and shallow-depth procedures are reviewed at the time of initial consultation. For patients who seek a full-depth vaginoplasty procedure, it is important to determine whether patients are committed to dilation and have a safe, supportive environment to do so. Patients may have physical limitations, such as obesity or mobility issues, that could make dilation difficult or even impossible. Patients may not have stable housing, may experience financial restrictions that would impede their ability to purchase necessary supplies, and lack a support person who can care for them in the immediate postoperative period. Many patients are unaware of the importance these social factors play in a successful outcome. Social workers and care coordinators are important resources when these challenges are encountered.

Medical optimization is not unlike other gynecologic procedures with a few exceptions. Obesity, diabetes, and smoking play larger roles in surgical complications than in other surgeries as vaginoplasty techniques use pedicled flaps that rely on adequate blood supply. Obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, and smoking are associated with increased rates of wound infection, poor wound healing, and graft loss. Smoking cessation for 8 weeks prior to surgery and for 4 weeks afterward is mandatory.

For patients with a history of smoking, a nicotine test is performed within 4 weeks of surgery. Many surgeons have body mass index requirements, typically ranging between 20 and 30 kg/m2, despite limited data. This paradigm is shifting to consider body fat distribution rather than BMI alone. Extensive body fat in the mons or groin area can increase the difficulty of pelvic floor dissection during surgery and impede visualization for dilation in the postoperative period. There are reports of patients dilating into their rectum or neourethra, which can have catastrophic consequences. For these patients, a zero-depth vaginoplasty or orchiectomy may initially be a safer option.

Many patients are justifiably excited to undergo the procedures as quality of life is typically improved after surgery. However, even with adequate counseling, many patients often underestimate the extensive recovery process. This surgical procedure requires extensive planning and adequate resources.4 Patients must be able to take off from work for prolonged periods of time (typically 6 weeks), which can serve as a source of financial stress. To maintain the integrity of suture lines in the genital region, prolonged or limited mobilization is recommended. This can create boredom and forces patients to rely on a caregiver for activities of daily living, such as household chores, cooking meals, and transportation.

Gender-affirming genital surgery is not only a complex surgical procedure but also requires extensive preoperative education and postoperative support. As this field continues to grow, patients, providers, and caregivers should work toward further developing a collaborative care model to optimize surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2020.

2. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report–2017.

3. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. Version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 23(S1):S1-S258. doi :10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

4. Penkin A et al. In: Nikolavsky D and Blakely SA, eds. Urological care for the transgender patient: A comprehensive guide. Switzerland: Springer, 2021:37-44.

5. Waljee J et al. Surgery. 2014;155:799-808.

Surgeon gender not associated with maternal morbidity and hemorrhage after C-section

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Update on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer

Recurrent ovarian cancer is difficult to treat; it has high recurrence rates and poor targeted treatment options. Between 60% and 75% of patients initially diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer will relapse within 2-3 years.1 Survival for these patients is poor, with an average overall survival (OS) of 30-40 months from the time of recurrence.2 Historically, immunotherapy has shown poor efficacy for recurrent ovarian malignancy, leaving few options for patients and their providers. Given the lack of effective treatment options, secondary cytoreductive surgery (surgery at the time of recurrence) has been heavily studied as a potential therapeutic option.

The initial rationale for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer focused on palliation of symptoms from large, bulky disease that frequently caused obstructive symptoms and pain. Now, cytoreduction is a critical part of therapy. It decreases chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells, improves the immune response, and is thought to optimize perfusion of the residual cancer for systemic therapy. The survival benefit of surgery in the frontline setting, either with primary or interval debulking, is well established, and much of the data now demonstrate that complete resection of all macroscopic disease (also known as an R0 resection) has the greatest survival benefit.3 Given the benefits of an initial debulking surgery, secondary cytoreduction has been studied since the 1980s with mixed results. These data have demonstrated that the largest barrier to care has been appropriate patient selection for this often complex surgical procedure.

The 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines list secondary CRS as a treatment option; however, the procedure should only be considered in patients who have platinum sensitive disease, a performance status of 0-1, no ascites, and an isolated focus or limited focus of disease that is amenable to complete resection. Numerous retrospective studies have suggested that secondary CRS is beneficial to patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially if complete cytoreduction can be accomplished. Many of these studies have similarly concluded that there are benefits, such as less ascites at the time of recurrence, smaller disease burden, and a longer disease-free interval. From that foundation, multiple groups used retrospective data to investigate prognostic models to determine who would benefit most from secondary cytoreduction.

The DESKTOP Group initially published their retrospective study in 2006 and created a scoring system assessing who would benefit from secondary CRS.4 Data demonstrated that a performance status of 0, FIGO stage of I/II at the time of initial diagnosis, no residual tumor after primary surgery, and ascites less than 500 mL were associated with improved survival after secondary cytoreduction. They created the AGO score out of these data, which is positive only if three criteria are met: a performance status of 0, R0 after primary debulk, and ascites less than 500 mL at the time of recurrence.

They prospectively tested this score in DESKTOP II, which validated their findings and showed that complete secondary CRS could be achieved in 76% of those with a positive AGO score.5 Many believed that the AGO score was too restrictive, and a second retrospective study performed by a group at Memorial Sloan Kettering showed that optimal secondary cytoreduction could be achieved to prolong survival by a median of 30 months in patients with a longer disease-free interval, a single site of recurrence, and residual disease measuring less than 5 mm at time of initial/first-line surgery.6 Many individuals now use this scoring system to determine candidacy for secondary debulking: disease-free interval, number of sites of recurrence (ideally oligometastatic disease), and residual disease less than 5 mm at the time of primary debulking.

Finally, the iMODEL was developed by a group from China and found that complete R0 secondary CRS was associated with a low initial FIGO stage, no residual disease after primary surgery, longer platinum-free interval, better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lower CA-125 levels, as well as no ascites at the time of recurrence. Based on these criteria, individuals received either high or low iMODEL scores, and those with a low score were said to be candidates for secondary CRS. Overall, these models demonstrate that the strongest predictive factor that suggests a survival benefit from secondary CRS is the ability to achieve a complete R0 resection at the time of surgery.

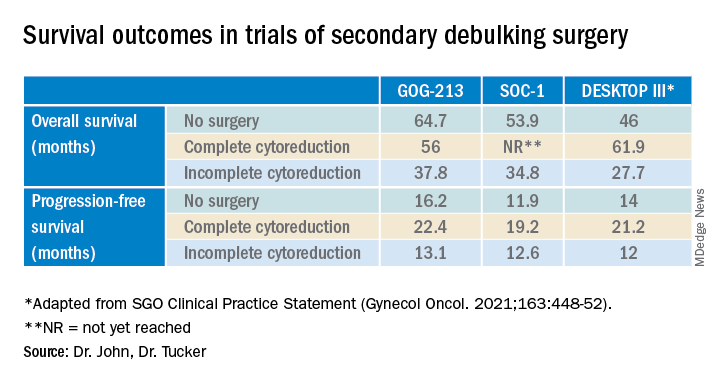

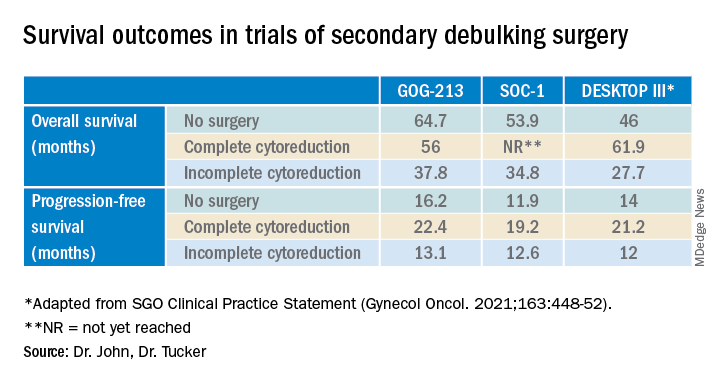

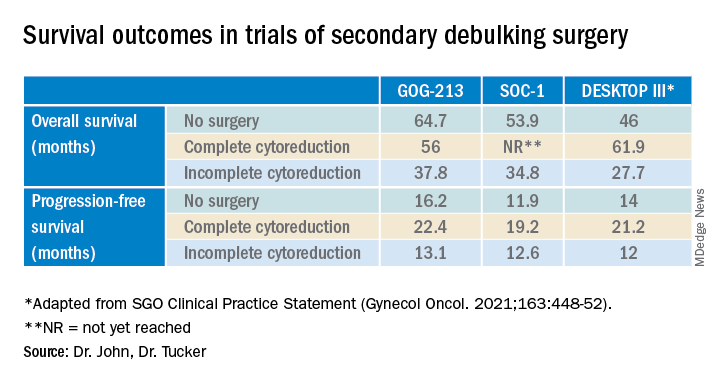

Secondary debulking surgery has been tested in three large randomized controlled trials. The DESKTOP investigators and the SOC-1 trial have been the most successful groups to publish on this topic with positive results. Both groups use prognostic models for their inclusion criteria to select candidates in whom an R0 resection is believed to be most feasible. The first randomized controlled trial to publish on this topic was GOG-213,7 which did not use prognostic modeling for their inclusion criteria. Patients were randomized to secondary cytoreduction followed by platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab versus chemotherapy alone. The median OS was 50.6 months in the surgery group and 64.7 months in the no-surgery group (P = .08), suggesting no survival benefit to secondary cytoreduction; however, an ad hoc exploratory analysis of the surgery arm showed that both overall and progression-free survival were significantly improved in the complete cytoreduction group, compared with those with residual disease at time of surgery.

The results from the GOG-213 group suggested that improved survival from secondary debulking might be achieved when prognostic modeling is used to select optimal surgical candidates. The SOC-1 trial, published in 2021, was a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial that used the iMODEL scoring system combined with PET/CT imaging for patient selection.8 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 73% of patients with a low iMODEL score, and these data showed improved OS in the surgery group of 58.1 months versus 53.9 months (P < .05) in the no-surgery group. Lastly, the DESKTOP group most recently published results on this topic in a large randomized, controlled trial.9 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Inclusion criteria were only met in patients with a positive AGO score. An improved OS of 7.7 months (53.7 vs. 46 months; P < .05) was demonstrated in patients that underwent surgery versus those exposed to only chemotherapy. Again, this group showed that overall survival was further improved when complete cytoreduction was achieved.

Given the results of these three trials, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology has released a statement on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer (see Table).10 While it is important to use caution when comparing the three studies as study populations differed substantially, the most important takeaway the difference in survival outcomes in patients in whom complete gross resection was achieved versus no complete gross resection versus no surgery. This comparison highlights the benefit of complete cytoreduction as well as the potential harms of secondary debulking when an R0 resection cannot be achieved. Although not yet evaluated in this clinical setting, laparoscopic exploration may be useful to augment assessment of disease extent and possibility of disease resection, just as it is in frontline ovarian cancer surgery.

The importance of bevacizumab use in recurrent ovarian cancer is also highlighted in the SGO statement. In GOG-213, 84% of the total study population (in both the surgery and no surgery cohort) were treated with concurrent followed by maintenance bevacizumab with an improved survival outcome, which may suggest that this trial generalizes better than the others to contemporary management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.

Overall, given the mixed data, the recommendation is for surgeons to consider all available data to guide them in treatment planning with a strong emphasis on using all available technology to assess whether complete cytoreduction can be achieved in the setting of recurrence so as to not delay the patient’s ability to receive chemotherapy.

Dr. John is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

1. du Bois A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320-9.

2. Wagner U et al. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:588-91.

3. Vergote I et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-53.

4. Harter P et al. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-10.

5. Harter P et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289-95.

6. Chi DS et al. Cancer. 2006 106:1933-9.

7. Coleman RL et al. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-1.

8. Shi T et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:439-49.

9. Harter P et al. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2123-31.

10. Harrison R, et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:448-52.

Recurrent ovarian cancer is difficult to treat; it has high recurrence rates and poor targeted treatment options. Between 60% and 75% of patients initially diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer will relapse within 2-3 years.1 Survival for these patients is poor, with an average overall survival (OS) of 30-40 months from the time of recurrence.2 Historically, immunotherapy has shown poor efficacy for recurrent ovarian malignancy, leaving few options for patients and their providers. Given the lack of effective treatment options, secondary cytoreductive surgery (surgery at the time of recurrence) has been heavily studied as a potential therapeutic option.

The initial rationale for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer focused on palliation of symptoms from large, bulky disease that frequently caused obstructive symptoms and pain. Now, cytoreduction is a critical part of therapy. It decreases chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells, improves the immune response, and is thought to optimize perfusion of the residual cancer for systemic therapy. The survival benefit of surgery in the frontline setting, either with primary or interval debulking, is well established, and much of the data now demonstrate that complete resection of all macroscopic disease (also known as an R0 resection) has the greatest survival benefit.3 Given the benefits of an initial debulking surgery, secondary cytoreduction has been studied since the 1980s with mixed results. These data have demonstrated that the largest barrier to care has been appropriate patient selection for this often complex surgical procedure.

The 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines list secondary CRS as a treatment option; however, the procedure should only be considered in patients who have platinum sensitive disease, a performance status of 0-1, no ascites, and an isolated focus or limited focus of disease that is amenable to complete resection. Numerous retrospective studies have suggested that secondary CRS is beneficial to patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially if complete cytoreduction can be accomplished. Many of these studies have similarly concluded that there are benefits, such as less ascites at the time of recurrence, smaller disease burden, and a longer disease-free interval. From that foundation, multiple groups used retrospective data to investigate prognostic models to determine who would benefit most from secondary cytoreduction.

The DESKTOP Group initially published their retrospective study in 2006 and created a scoring system assessing who would benefit from secondary CRS.4 Data demonstrated that a performance status of 0, FIGO stage of I/II at the time of initial diagnosis, no residual tumor after primary surgery, and ascites less than 500 mL were associated with improved survival after secondary cytoreduction. They created the AGO score out of these data, which is positive only if three criteria are met: a performance status of 0, R0 after primary debulk, and ascites less than 500 mL at the time of recurrence.

They prospectively tested this score in DESKTOP II, which validated their findings and showed that complete secondary CRS could be achieved in 76% of those with a positive AGO score.5 Many believed that the AGO score was too restrictive, and a second retrospective study performed by a group at Memorial Sloan Kettering showed that optimal secondary cytoreduction could be achieved to prolong survival by a median of 30 months in patients with a longer disease-free interval, a single site of recurrence, and residual disease measuring less than 5 mm at time of initial/first-line surgery.6 Many individuals now use this scoring system to determine candidacy for secondary debulking: disease-free interval, number of sites of recurrence (ideally oligometastatic disease), and residual disease less than 5 mm at the time of primary debulking.

Finally, the iMODEL was developed by a group from China and found that complete R0 secondary CRS was associated with a low initial FIGO stage, no residual disease after primary surgery, longer platinum-free interval, better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lower CA-125 levels, as well as no ascites at the time of recurrence. Based on these criteria, individuals received either high or low iMODEL scores, and those with a low score were said to be candidates for secondary CRS. Overall, these models demonstrate that the strongest predictive factor that suggests a survival benefit from secondary CRS is the ability to achieve a complete R0 resection at the time of surgery.

Secondary debulking surgery has been tested in three large randomized controlled trials. The DESKTOP investigators and the SOC-1 trial have been the most successful groups to publish on this topic with positive results. Both groups use prognostic models for their inclusion criteria to select candidates in whom an R0 resection is believed to be most feasible. The first randomized controlled trial to publish on this topic was GOG-213,7 which did not use prognostic modeling for their inclusion criteria. Patients were randomized to secondary cytoreduction followed by platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab versus chemotherapy alone. The median OS was 50.6 months in the surgery group and 64.7 months in the no-surgery group (P = .08), suggesting no survival benefit to secondary cytoreduction; however, an ad hoc exploratory analysis of the surgery arm showed that both overall and progression-free survival were significantly improved in the complete cytoreduction group, compared with those with residual disease at time of surgery.

The results from the GOG-213 group suggested that improved survival from secondary debulking might be achieved when prognostic modeling is used to select optimal surgical candidates. The SOC-1 trial, published in 2021, was a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial that used the iMODEL scoring system combined with PET/CT imaging for patient selection.8 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 73% of patients with a low iMODEL score, and these data showed improved OS in the surgery group of 58.1 months versus 53.9 months (P < .05) in the no-surgery group. Lastly, the DESKTOP group most recently published results on this topic in a large randomized, controlled trial.9 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Inclusion criteria were only met in patients with a positive AGO score. An improved OS of 7.7 months (53.7 vs. 46 months; P < .05) was demonstrated in patients that underwent surgery versus those exposed to only chemotherapy. Again, this group showed that overall survival was further improved when complete cytoreduction was achieved.

Given the results of these three trials, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology has released a statement on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer (see Table).10 While it is important to use caution when comparing the three studies as study populations differed substantially, the most important takeaway the difference in survival outcomes in patients in whom complete gross resection was achieved versus no complete gross resection versus no surgery. This comparison highlights the benefit of complete cytoreduction as well as the potential harms of secondary debulking when an R0 resection cannot be achieved. Although not yet evaluated in this clinical setting, laparoscopic exploration may be useful to augment assessment of disease extent and possibility of disease resection, just as it is in frontline ovarian cancer surgery.

The importance of bevacizumab use in recurrent ovarian cancer is also highlighted in the SGO statement. In GOG-213, 84% of the total study population (in both the surgery and no surgery cohort) were treated with concurrent followed by maintenance bevacizumab with an improved survival outcome, which may suggest that this trial generalizes better than the others to contemporary management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.

Overall, given the mixed data, the recommendation is for surgeons to consider all available data to guide them in treatment planning with a strong emphasis on using all available technology to assess whether complete cytoreduction can be achieved in the setting of recurrence so as to not delay the patient’s ability to receive chemotherapy.

Dr. John is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

1. du Bois A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320-9.

2. Wagner U et al. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:588-91.

3. Vergote I et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-53.

4. Harter P et al. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-10.

5. Harter P et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289-95.

6. Chi DS et al. Cancer. 2006 106:1933-9.

7. Coleman RL et al. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-1.

8. Shi T et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:439-49.

9. Harter P et al. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2123-31.

10. Harrison R, et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:448-52.

Recurrent ovarian cancer is difficult to treat; it has high recurrence rates and poor targeted treatment options. Between 60% and 75% of patients initially diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer will relapse within 2-3 years.1 Survival for these patients is poor, with an average overall survival (OS) of 30-40 months from the time of recurrence.2 Historically, immunotherapy has shown poor efficacy for recurrent ovarian malignancy, leaving few options for patients and their providers. Given the lack of effective treatment options, secondary cytoreductive surgery (surgery at the time of recurrence) has been heavily studied as a potential therapeutic option.

The initial rationale for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer focused on palliation of symptoms from large, bulky disease that frequently caused obstructive symptoms and pain. Now, cytoreduction is a critical part of therapy. It decreases chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells, improves the immune response, and is thought to optimize perfusion of the residual cancer for systemic therapy. The survival benefit of surgery in the frontline setting, either with primary or interval debulking, is well established, and much of the data now demonstrate that complete resection of all macroscopic disease (also known as an R0 resection) has the greatest survival benefit.3 Given the benefits of an initial debulking surgery, secondary cytoreduction has been studied since the 1980s with mixed results. These data have demonstrated that the largest barrier to care has been appropriate patient selection for this often complex surgical procedure.

The 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines list secondary CRS as a treatment option; however, the procedure should only be considered in patients who have platinum sensitive disease, a performance status of 0-1, no ascites, and an isolated focus or limited focus of disease that is amenable to complete resection. Numerous retrospective studies have suggested that secondary CRS is beneficial to patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially if complete cytoreduction can be accomplished. Many of these studies have similarly concluded that there are benefits, such as less ascites at the time of recurrence, smaller disease burden, and a longer disease-free interval. From that foundation, multiple groups used retrospective data to investigate prognostic models to determine who would benefit most from secondary cytoreduction.

The DESKTOP Group initially published their retrospective study in 2006 and created a scoring system assessing who would benefit from secondary CRS.4 Data demonstrated that a performance status of 0, FIGO stage of I/II at the time of initial diagnosis, no residual tumor after primary surgery, and ascites less than 500 mL were associated with improved survival after secondary cytoreduction. They created the AGO score out of these data, which is positive only if three criteria are met: a performance status of 0, R0 after primary debulk, and ascites less than 500 mL at the time of recurrence.

They prospectively tested this score in DESKTOP II, which validated their findings and showed that complete secondary CRS could be achieved in 76% of those with a positive AGO score.5 Many believed that the AGO score was too restrictive, and a second retrospective study performed by a group at Memorial Sloan Kettering showed that optimal secondary cytoreduction could be achieved to prolong survival by a median of 30 months in patients with a longer disease-free interval, a single site of recurrence, and residual disease measuring less than 5 mm at time of initial/first-line surgery.6 Many individuals now use this scoring system to determine candidacy for secondary debulking: disease-free interval, number of sites of recurrence (ideally oligometastatic disease), and residual disease less than 5 mm at the time of primary debulking.

Finally, the iMODEL was developed by a group from China and found that complete R0 secondary CRS was associated with a low initial FIGO stage, no residual disease after primary surgery, longer platinum-free interval, better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lower CA-125 levels, as well as no ascites at the time of recurrence. Based on these criteria, individuals received either high or low iMODEL scores, and those with a low score were said to be candidates for secondary CRS. Overall, these models demonstrate that the strongest predictive factor that suggests a survival benefit from secondary CRS is the ability to achieve a complete R0 resection at the time of surgery.

Secondary debulking surgery has been tested in three large randomized controlled trials. The DESKTOP investigators and the SOC-1 trial have been the most successful groups to publish on this topic with positive results. Both groups use prognostic models for their inclusion criteria to select candidates in whom an R0 resection is believed to be most feasible. The first randomized controlled trial to publish on this topic was GOG-213,7 which did not use prognostic modeling for their inclusion criteria. Patients were randomized to secondary cytoreduction followed by platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab versus chemotherapy alone. The median OS was 50.6 months in the surgery group and 64.7 months in the no-surgery group (P = .08), suggesting no survival benefit to secondary cytoreduction; however, an ad hoc exploratory analysis of the surgery arm showed that both overall and progression-free survival were significantly improved in the complete cytoreduction group, compared with those with residual disease at time of surgery.

The results from the GOG-213 group suggested that improved survival from secondary debulking might be achieved when prognostic modeling is used to select optimal surgical candidates. The SOC-1 trial, published in 2021, was a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial that used the iMODEL scoring system combined with PET/CT imaging for patient selection.8 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 73% of patients with a low iMODEL score, and these data showed improved OS in the surgery group of 58.1 months versus 53.9 months (P < .05) in the no-surgery group. Lastly, the DESKTOP group most recently published results on this topic in a large randomized, controlled trial.9 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Inclusion criteria were only met in patients with a positive AGO score. An improved OS of 7.7 months (53.7 vs. 46 months; P < .05) was demonstrated in patients that underwent surgery versus those exposed to only chemotherapy. Again, this group showed that overall survival was further improved when complete cytoreduction was achieved.

Given the results of these three trials, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology has released a statement on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer (see Table).10 While it is important to use caution when comparing the three studies as study populations differed substantially, the most important takeaway the difference in survival outcomes in patients in whom complete gross resection was achieved versus no complete gross resection versus no surgery. This comparison highlights the benefit of complete cytoreduction as well as the potential harms of secondary debulking when an R0 resection cannot be achieved. Although not yet evaluated in this clinical setting, laparoscopic exploration may be useful to augment assessment of disease extent and possibility of disease resection, just as it is in frontline ovarian cancer surgery.

The importance of bevacizumab use in recurrent ovarian cancer is also highlighted in the SGO statement. In GOG-213, 84% of the total study population (in both the surgery and no surgery cohort) were treated with concurrent followed by maintenance bevacizumab with an improved survival outcome, which may suggest that this trial generalizes better than the others to contemporary management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.

Overall, given the mixed data, the recommendation is for surgeons to consider all available data to guide them in treatment planning with a strong emphasis on using all available technology to assess whether complete cytoreduction can be achieved in the setting of recurrence so as to not delay the patient’s ability to receive chemotherapy.

Dr. John is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

1. du Bois A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320-9.

2. Wagner U et al. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:588-91.

3. Vergote I et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-53.

4. Harter P et al. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-10.

5. Harter P et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289-95.

6. Chi DS et al. Cancer. 2006 106:1933-9.

7. Coleman RL et al. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-1.

8. Shi T et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:439-49.

9. Harter P et al. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2123-31.

10. Harrison R, et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:448-52.

Liability in robotic gyn surgery

The approach to hysterectomy has been debated, with the need for individualization case by case stressed, and the expertise of the operating surgeon considered.

CASE Was surgeon experience a factor in case complications?

VM is a 46-year-old woman (G5 P4014) reporting persistent uterine bleeding that is refractory to medical therapy. The patient has uterine fibroids, 6 weeks in size on examination, with “mild” prolapse noted. Additional medical diagnoses included vulvitis, ovarian cyst in the past, cystic mastopathy, and prior evidence of pelvic adhesion, noted at the time of ovarian cystectomy. Prior surgical records were not obtained by the operating surgeon, although her obstetric history includes 2 prior vaginal deliveries and 2 cesarean deliveries (CDs). The patient had an umbilical herniorraphy a number of years ago. Her medications include hormonal therapy, for presumed menopause, and medication for depression (she reported “doing well” on medication). She reported smoking 1 PPD and had a prior tubal ligation.

VM was previously evaluated for Lynch Syndrome and informed of the potential for increased risks of colon, endometrial, and several other cancers. She did not have cancer as of the time of planned surgery.

The patient underwent robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The operating surgeon did not have a lot of experience with robotic hysterectomies but told the patient preoperatively “I have done a few.” Perioperatively, blood loss was minimal, urine output was recorded as 25 mL, and according to the operative report there were extensive pelvic adhesions and no complications. The “ureters were identified” when the broad ligament was opened at the time of skeletonization of the uterine vessels and documented accordingly. The intraoperative Foley was discontinued at the end of the procedure. The pathology report noted diffuse adenomyosis and uterine fibroids; the uterus weighed 250 g. In addition, a “large hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst” was noted on the right ovary.

The patient presented for a postoperative visit reporting “leaking” serosanguinous fluid that began 2.5 weeks postoperatively and required her to wear 3 to 4 “Depends” every day. She also reported constipation since beginning her prescribed pain medication. She requested a copy of her medical records and said she was dissatisfied with the care she had received related to the hysterectomy; she was “seeking a second opinion from a urologist.” The urologist suggested evaluation of the “leaking,” and a Foley catheter was placed. When she stood up, however, there was leaking around the catheter, and she reported a “yellowish-green,” foul smelling discharge. She called the urologist’s office, stating, “I think I have a bowel obstruction.” The patient was instructed to proceed to the emergency department at her local hospital. She was released with a diagnosis of constipation. Upon follow-up urologic evaluation, a vulvovaginal fistula was noted. Management was a “simple fistula repair,” and the patient did well subsequently.

The patient brought suit against the hospital and operating gynecologist. In part the hospital records noted, “relatively inexperienced robotic surgeon.” The hospital was taken to task for granting privileges to an individual that had prior privilege “problems.”

Continue to: Medical opinion...

Medical opinion

This case demonstrates a number of issues. (We will discuss the credentials for the surgeon and hospital privileges in the legal considerations section.) From the medical perspective, the rate of urologic injury associated with all hysterectomies is 0.87%.1 Robotic hysterectomy has been reported at 0.92% in a series published from Henry Ford Hospital.1 The lowest rate of urologic injury is associated with vaginal hysterectomy, reported at 0.2%.2 Reported rates of urologic injury by approach to hysterectomy are1:

- robotic, 0.92%

- laparoscopic, 0.90%

- vaginal, 0.33%

- abdominal, 0.96%.

Complications by surgeon type also have been addressed, and the percent of total urologic complications are reported as1:

- ObGyn, 47%

- gyn oncologist, 47%

- urogynecologist, 6%.

Intraoperative conversion to laparotomy from initial robotic approach has been addressed in a retrospective study over a 2-year period, with operative times ranging from 1 hr, 50 min to 9 hrs of surgical time.1 The vast majority of intraoperative complications in a series reported from Finland were managed “within minutes,” and in the series of 83 patients, 5 (6%) required conversion to laparotomy.2 Intraoperative complications reported include failed entry, vascular injury, nerve injury, visceral injury, solid organ injury, tumor fragmentation, and anesthetic-related complications.3 Of note, the vascular injuries included inferior vena cava, common iliac, and external iliac.

Mortality rates in association with benign laparoscopic and robotic procedures have been addressed and noted to be 1:6,456 cases based upon a meta-analysis.4 The analysis included 124,216 patients. Laparoscopic versus robotic mortality rates were not statistically different. Mortality was more common among cases of undiagnosed rare colorectal injury. This mortality is on par with complications from Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures. Procedures such as sacrocolpopexy are equated with higher mortality (1:1,246) in comparison with benign hysterectomy.5

Infectious complications following either laparoscopic or robotic hysterectomy were reported at less than 1% and not statistically different for either approach.6 The series authored by Marra et al evaluated 176,016 patients.

Overall, robotic-assisted gynecologic complications are rare. One series was focused on gynecological oncologic cases.7 Specific categories of complications included7:

- patient positioning and pneumoperitoneum

- injury to surrounding organs

- bowel injury

- port site metastasis

- surgical emphysema

- vaginal cuff dehiscence

- anesthesia-related problems.

The authors concluded, “robotic assisted surgery in gynecological oncology is safe and the incidence of complications is low.”7 The major cause of death related to robotic surgery is vascular injury–related. The authors emphasized the importance of knowledge of anatomy, basic principles of “traction and counter-traction” and proper dissection along tissue planes as key to minimizing complications. Consider placement of stents for ureter identification, as appropriate. Barbed-suturing does not prevent dehiscence.

Continue to: Legal considerations...

Legal considerations

Robotic surgery presents many legal issues and promises to raise many more in the future. The law must control new technology while encouraging productive uses, and provide new remedies for harms while respecting traditional legal principles.8 There is no shortage of good ideas about controlling surgical robots,9 automated devices more generally,10 and artificial intelligence.11 Those issues will be important, and watching them unfold will be intriguing.

In the meantime, physicians and other health care professionals, health care facilities, technology companies, and patients must work within current legal structures in implementing and using robotic surgery. These are extraordinarily complex issues, so it is possible only to review the current landscape and speculate what the near future may hold.

Regulating surgical robots

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the primary regulator of robots used in medicine.12 It has the authority to regulate surgical devices, including surgical robots—which it refers to as “robotically-assisted surgical devices,” or RASD. In 2000, it approved Intuitive Surgical’s daVinci system for use in surgery. In 2017, the FDA expanded its clearance to include the Senhance System of TransEnterix Surgical Inc. for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.13 In 2021, the FDA cleared the Hominis Surgical System for transvaginal hysterectomy “in certain patients.” However, the FDA emphasized that this clearance is for benign hysterectomy with salpingo-oophorectomy.14 (The FDA has cleared various robotic devices for several other areas of surgical practice, including neurosurgery, orthopedics, and urology.)

The use of robots in cancer surgery is limited. The FDA approved specific RASDs in some “surgical procedures commonly performed in patients with cancer, such as hysterectomy, prostatectomy, and colectomy.”15 However, it cautioned that this clearance was based only on a 30-day patient follow up. More specifically, the FDA “has not evaluated the safety or effectiveness of RASD devices for the prevention or treatment of cancer, based on cancer-related outcomes such as overall survival, recurrence, and disease-free survival.”15

The FDA has clearly warned physicians and patients that the agency has not granted the use of RASDs “for any cancer-related surgery marketing authorization, and therefore the survival benefits to patients compared to traditional surgery have not been established.”15 (This did not apply to the hysterectomy surgery as noted above. More specifically, that clearance did not apply to anything other than 30-day results, nor to the efficacy related to cancer survival.)

States also have some authority to regulate medical practice within their borders.9 When the FDA has approved a device as safe and effective, however, there are limits on what states can do to regulate or impose liability on the approved product. The Supreme Court held that the FDA approval “pre-empted” some state action regarding approved devices.16

Hospitals, of course, regulate what is allowed within the hospital. For example, it may require training before a physician is permitted to use equipment, limit the conditions for which the equipment may be used, or decline to obtain equipment for use in the hospitals.17 In the case of RASDs, however, the high cost of equipment may provide an incentive for hospitals to urge the wide use of the latest robotic acquisition.18

Regulation aims primarily to protect patients, usually from injury or inadequate treatment. Some robotic surgery is likely to be more expensive than the same surgery without robotic assistance. The cost to the patient is not usually part of the FDA’s consideration. Insurance companies (including Medicare and Medicaid), however, do care about costs and will set or negotiate how much the reimbursement will be for a procedure. Third-party payers may decline to cover the additional cost when there is no apparent benefit from using the robot.19 For some institutions, the public perception that it offers “the most modern technology” is an important public message and a strong incentive to have the equipment.20

There are inconsistent studies about the advantages and disadvantages of RADS in gynecologic procedures, although there are few randomized studies.21 The demonstrated advantages are generally identified as somewhat shorter recovery time.22 The ultimate goal will be to minimize risks while maximizing the many potential benefits of robotic surgery.23

Continue to: Liability...

Liability

A recent study by De Ravin and colleagues of robotic surgery liability found a 250% increase in the total number of robotic surgery–related malpractice claims reported in 7 recent years (2014-2021), compared with the prior 7 (2006-2013).24 However, the number of cases varied considerably from year to year. ObGyn had the most significant gain (from 19% to 49% of all claims). During the same time, urology claims declined from 56% to 16%. (The limitations of the study’s data are discussed later in this article.)

De Ravin et al reported the legal bases for the claims, but the specific legal claim was unclear in many cases.24 For example, the vast majority were classified as “negligent surgery.” Many cases made more than 1 legal claim for liability, so the total percentages were greater than 100%. Of the specific claims, many appear unrelated to robotic surgery (misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, or infection). However, there were a significant number of cases that raised issues that were related to robotic surgery. The following are those claims that probably relate to the “robotic” surgery, along with the percentage of cases making such a claim as reported24:

- “Patient not a candidate for surgery performed” appeared in about 13% of the cases.24 Such claims could include that the surgeon should have performed the surgery with traditional laparoscopy or open technique, but instead using a robot led to the injury. Physicians may feel pressure from patients or hospitals, because of the equipment’s cost, to use robotic surgery as it seems to be the modern approach (and therefore better). Neither reason is sufficient for using robotic assistance unless it will benefit the patient.

- “Failure to calibrate or operate robot” was in 11% of the claims.24 Physicians must properly calibrate and otherwise ensure that surgical equipment is operating correctly. In addition, the hospitals supplying the equipment must ensure that the equipment is maintained correctly. Finally, the equipment manufacturer may be liable through “products liability” if the equipment is defective.25 The expanding use of artificial intelligence in medical equipment (including surgical robots) is increasing the complexity of determining what “defective” means.11

- “Training deficiencies or credentialing” liability is a common problem with new technology. Physicians using new technology should be thoroughly trained and, where appropriate, certified in the use of the new technology.26 Early adopters of the technology should be especially cautious because good training may be challenging to obtain. In the study, the claims of inadequate training were particularly high during the early 7 years (35%), but dropped during the later time (4%).24

- “Improper positioning” of the patient or device or patient was raised in 7% of the cases.24