User login

Patient-reported complications regarding PICC lines after inpatient discharge

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Thromboembolic events more likely among CIDP patients with CVAD

AUSTIN, TEX. – Patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) who receive intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) appear to have an increased risk of thromboembolic events if it is administered with a central venous access device (CVAD) when compared against those without a CVAD, according to a recent study.

Although CVADs can reliably deliver IVIg, they also represent an established risk factor for thromboembolic events, Ami Patel, PhD, a senior epidemiologist at CSL Behring, and colleagues noted on their poster at the annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

The results suggest a need for physicians to be vigilant about patients’ potential risk factors for thromboembolic events, Dr. Patel said in an interview. Further research is planned, however, because the current study did not control for other risk factors or explore other possible confounding, she said.

Dr. Patel and her associates analyzed U.S. claims data (IBM/Truven MarketScan) from 2006 to 2018 and included all patients with a CIDP diagnosis claim and a postdiagnosis code for IVIg. A code for CVAD up to 2 months before CIDP diagnosis without removal before IVIg treatment ended determined those with CVAD exposure, and thromboembolic events included any codes related to arterial, venous, or vascular prostheses.

The researchers then compared patients in a case-control fashion, matching each one with a CVAD to five patients of similar demographics without a CVAD. Characteristics used for matching included medical insurance type, prescription data availability, sex, age, geographic region, and years enrolled in the database.

Among 7,447 patients with at least one IVIg claim, 11.8% (n = 882) had CVAD exposure and 88.2% (n = 6,565) did not. Of those without a CVAD, 3,642 patients were matched to patients with CVAD. A quarter (25.4%) of patients with a CVAD had a thromboembolic event, compared with 11.2% of matched patients without CVADs (P less than .0001).

In the year leading up to IVIg therapy, 16.9% of those with a CVAD and 10.9% of matched patients without one had a previous thromboembolic event (P less than .0001). Patients with a CVAD also had significantly higher rates of hypertension (51.9% vs. 45.0% with placebo; P less than .001) and anticoagulation therapy (7.0% vs. 5.2% with placebo; P less than .05). Differences between the groups were not significant for diabetes (26.9% vs. 24.2%) and hyperlipidemia (19.1% vs. 17.8%).

Occlusion and stenosis of the carotid artery was the most common arterial thromboembolic outcome, occurring in 5.3% of those with a CVAD and in 2.8% of those without a CVAD. The most common venous thromboembolic event was acute venous embolism and thrombosis of lower-extremity deep vessels, which occurred in 7% of those with a CVAD and in 1.8% of those without.

The researchers also compared inpatient admissions and emergency department visits among those with and without a CVAD; both rates were higher in patients with a CVAD. Visits to the emergency department occurred at a rate of 0.14 events per month for those with a CVAD (2.01 distinct months with a claim) and 0.09 events per month for those without a CVAD (0.65 distinct months with a claim). Patients with a CVAD had 1.44 months with an inpatient admissions claim, in comparison with 0.41 months among matched patients without a CVAD. Inpatient admission frequency per month was 0.14 for those with a CVAD and 0.08 for those without.

The research was funded by CSL Behring. Dr. Patel and two of the other five authors are employees of CSL Behring.

SOURCE: Patel A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 94.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) who receive intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) appear to have an increased risk of thromboembolic events if it is administered with a central venous access device (CVAD) when compared against those without a CVAD, according to a recent study.

Although CVADs can reliably deliver IVIg, they also represent an established risk factor for thromboembolic events, Ami Patel, PhD, a senior epidemiologist at CSL Behring, and colleagues noted on their poster at the annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

The results suggest a need for physicians to be vigilant about patients’ potential risk factors for thromboembolic events, Dr. Patel said in an interview. Further research is planned, however, because the current study did not control for other risk factors or explore other possible confounding, she said.

Dr. Patel and her associates analyzed U.S. claims data (IBM/Truven MarketScan) from 2006 to 2018 and included all patients with a CIDP diagnosis claim and a postdiagnosis code for IVIg. A code for CVAD up to 2 months before CIDP diagnosis without removal before IVIg treatment ended determined those with CVAD exposure, and thromboembolic events included any codes related to arterial, venous, or vascular prostheses.

The researchers then compared patients in a case-control fashion, matching each one with a CVAD to five patients of similar demographics without a CVAD. Characteristics used for matching included medical insurance type, prescription data availability, sex, age, geographic region, and years enrolled in the database.

Among 7,447 patients with at least one IVIg claim, 11.8% (n = 882) had CVAD exposure and 88.2% (n = 6,565) did not. Of those without a CVAD, 3,642 patients were matched to patients with CVAD. A quarter (25.4%) of patients with a CVAD had a thromboembolic event, compared with 11.2% of matched patients without CVADs (P less than .0001).

In the year leading up to IVIg therapy, 16.9% of those with a CVAD and 10.9% of matched patients without one had a previous thromboembolic event (P less than .0001). Patients with a CVAD also had significantly higher rates of hypertension (51.9% vs. 45.0% with placebo; P less than .001) and anticoagulation therapy (7.0% vs. 5.2% with placebo; P less than .05). Differences between the groups were not significant for diabetes (26.9% vs. 24.2%) and hyperlipidemia (19.1% vs. 17.8%).

Occlusion and stenosis of the carotid artery was the most common arterial thromboembolic outcome, occurring in 5.3% of those with a CVAD and in 2.8% of those without a CVAD. The most common venous thromboembolic event was acute venous embolism and thrombosis of lower-extremity deep vessels, which occurred in 7% of those with a CVAD and in 1.8% of those without.

The researchers also compared inpatient admissions and emergency department visits among those with and without a CVAD; both rates were higher in patients with a CVAD. Visits to the emergency department occurred at a rate of 0.14 events per month for those with a CVAD (2.01 distinct months with a claim) and 0.09 events per month for those without a CVAD (0.65 distinct months with a claim). Patients with a CVAD had 1.44 months with an inpatient admissions claim, in comparison with 0.41 months among matched patients without a CVAD. Inpatient admission frequency per month was 0.14 for those with a CVAD and 0.08 for those without.

The research was funded by CSL Behring. Dr. Patel and two of the other five authors are employees of CSL Behring.

SOURCE: Patel A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 94.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) who receive intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) appear to have an increased risk of thromboembolic events if it is administered with a central venous access device (CVAD) when compared against those without a CVAD, according to a recent study.

Although CVADs can reliably deliver IVIg, they also represent an established risk factor for thromboembolic events, Ami Patel, PhD, a senior epidemiologist at CSL Behring, and colleagues noted on their poster at the annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

The results suggest a need for physicians to be vigilant about patients’ potential risk factors for thromboembolic events, Dr. Patel said in an interview. Further research is planned, however, because the current study did not control for other risk factors or explore other possible confounding, she said.

Dr. Patel and her associates analyzed U.S. claims data (IBM/Truven MarketScan) from 2006 to 2018 and included all patients with a CIDP diagnosis claim and a postdiagnosis code for IVIg. A code for CVAD up to 2 months before CIDP diagnosis without removal before IVIg treatment ended determined those with CVAD exposure, and thromboembolic events included any codes related to arterial, venous, or vascular prostheses.

The researchers then compared patients in a case-control fashion, matching each one with a CVAD to five patients of similar demographics without a CVAD. Characteristics used for matching included medical insurance type, prescription data availability, sex, age, geographic region, and years enrolled in the database.

Among 7,447 patients with at least one IVIg claim, 11.8% (n = 882) had CVAD exposure and 88.2% (n = 6,565) did not. Of those without a CVAD, 3,642 patients were matched to patients with CVAD. A quarter (25.4%) of patients with a CVAD had a thromboembolic event, compared with 11.2% of matched patients without CVADs (P less than .0001).

In the year leading up to IVIg therapy, 16.9% of those with a CVAD and 10.9% of matched patients without one had a previous thromboembolic event (P less than .0001). Patients with a CVAD also had significantly higher rates of hypertension (51.9% vs. 45.0% with placebo; P less than .001) and anticoagulation therapy (7.0% vs. 5.2% with placebo; P less than .05). Differences between the groups were not significant for diabetes (26.9% vs. 24.2%) and hyperlipidemia (19.1% vs. 17.8%).

Occlusion and stenosis of the carotid artery was the most common arterial thromboembolic outcome, occurring in 5.3% of those with a CVAD and in 2.8% of those without a CVAD. The most common venous thromboembolic event was acute venous embolism and thrombosis of lower-extremity deep vessels, which occurred in 7% of those with a CVAD and in 1.8% of those without.

The researchers also compared inpatient admissions and emergency department visits among those with and without a CVAD; both rates were higher in patients with a CVAD. Visits to the emergency department occurred at a rate of 0.14 events per month for those with a CVAD (2.01 distinct months with a claim) and 0.09 events per month for those without a CVAD (0.65 distinct months with a claim). Patients with a CVAD had 1.44 months with an inpatient admissions claim, in comparison with 0.41 months among matched patients without a CVAD. Inpatient admission frequency per month was 0.14 for those with a CVAD and 0.08 for those without.

The research was funded by CSL Behring. Dr. Patel and two of the other five authors are employees of CSL Behring.

SOURCE: Patel A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 94.

REPORTING FROM AANEM 2019

How should anticoagulation be managed in a patient with cirrhosis?

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

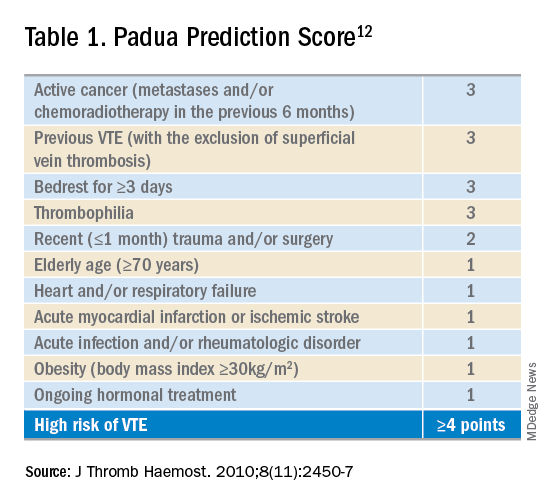

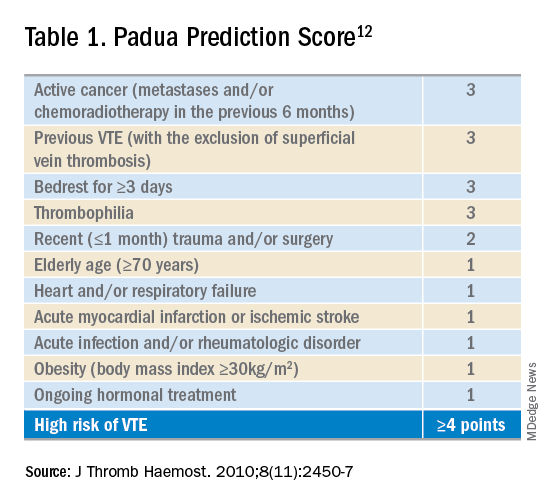

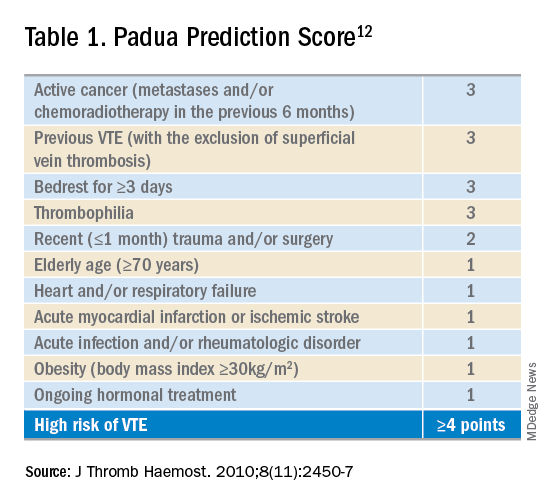

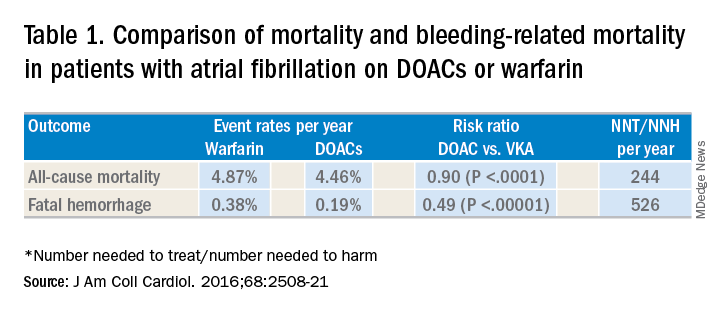

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

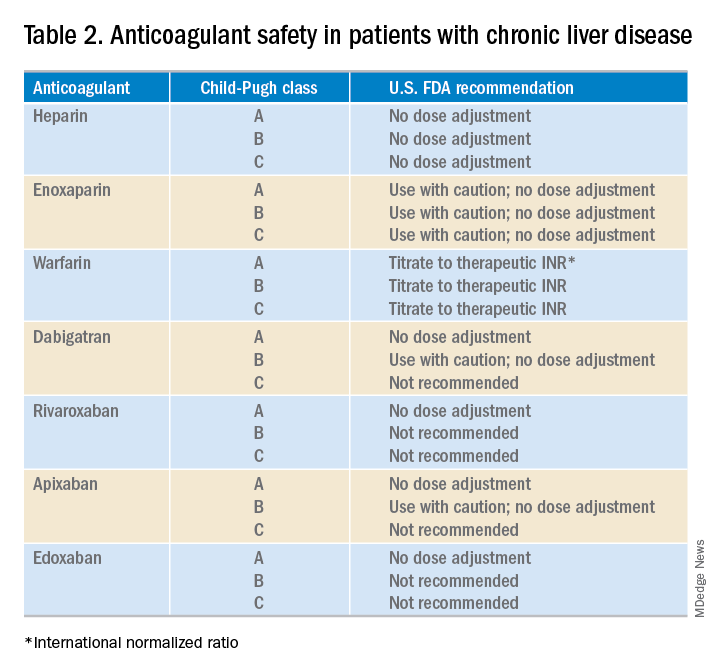

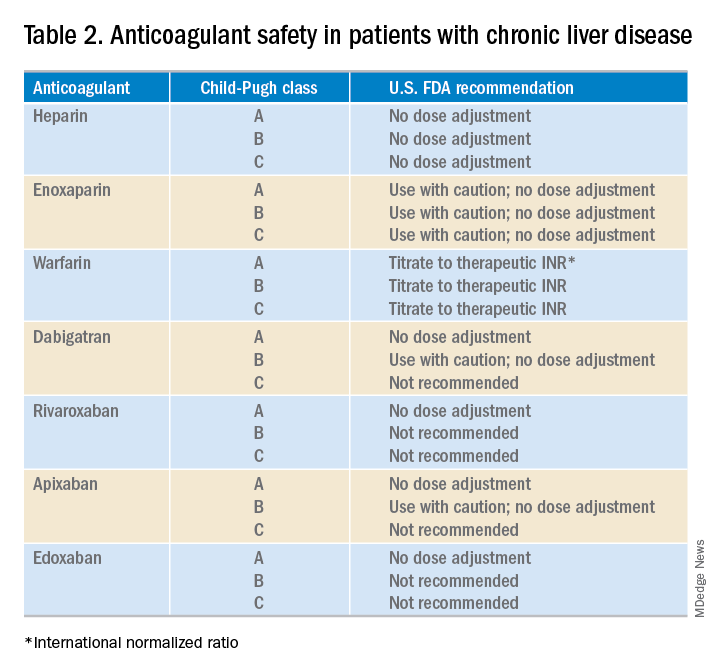

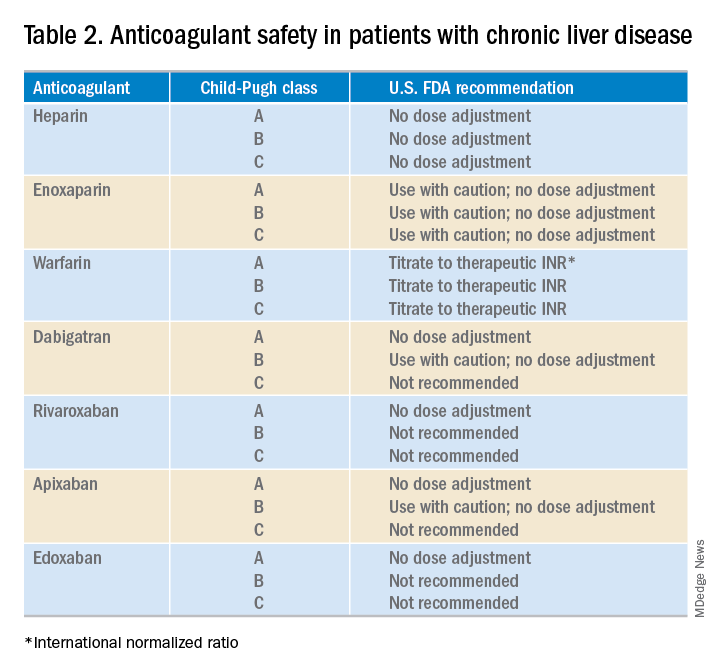

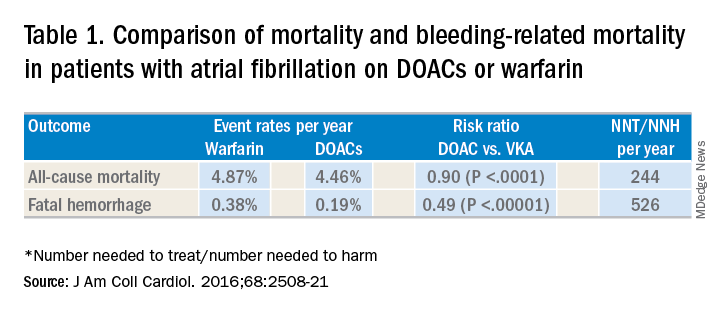

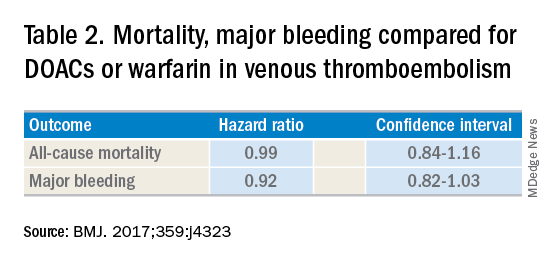

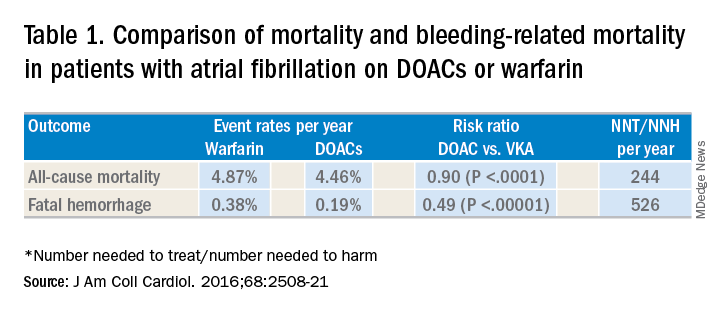

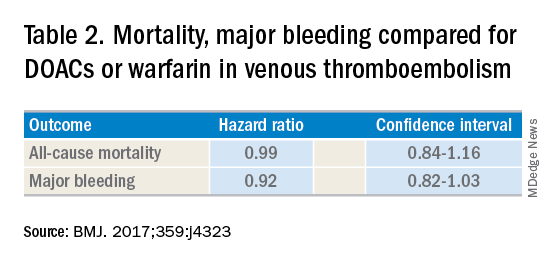

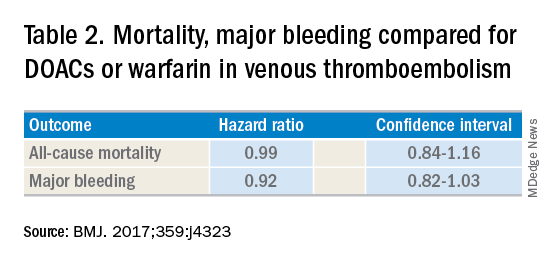

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

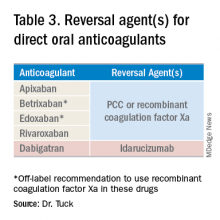

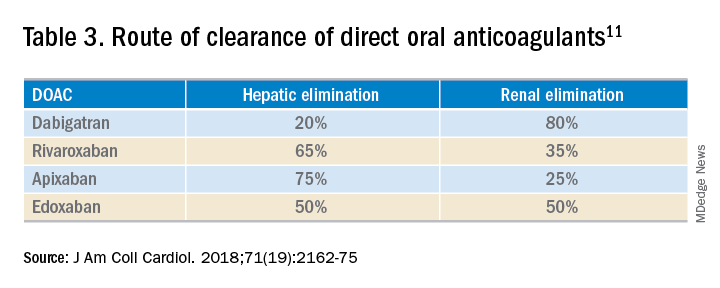

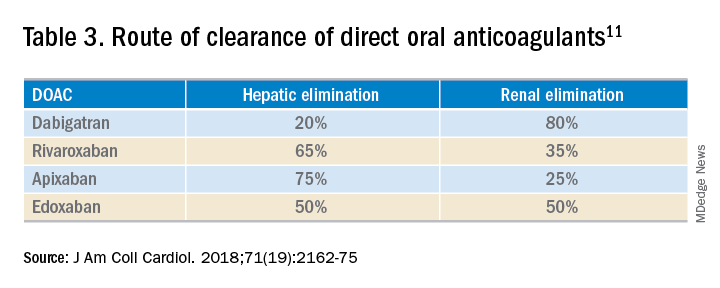

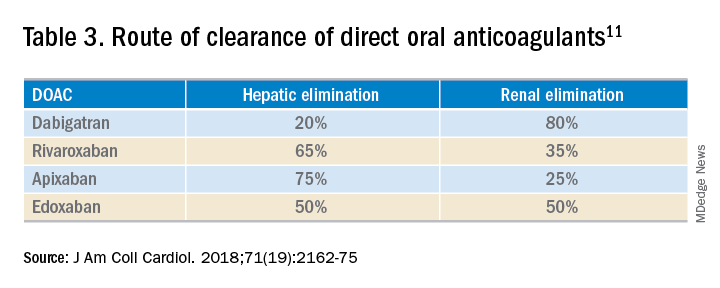

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.

FDA approves rivaroxaban for VTE prevention in hospitalized, acutely ill patients

The Food and Drug Administration has approved rivaroxaban (Xarelto) for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized, acutely ill patients at risk for thromboembolic complications who do not have a high bleeding risk, according to a release from Janssen.

FDA approval for the new indication is based on results from the phase 3 MAGELLAN and MARINER trials, which included more than 20,000 hospitalized, acutely ill patients. In MAGELLAN, rivaroxaban demonstrated noninferiority to enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, in short-term usage, and it was superior over the long term, compared with short-term enoxaparin followed by placebo.

While VTE and VTE-related deaths were not reduced in MARINER, compared with placebo, patients who received rivaroxaban did see a significantly reduction in symptomatic VTE with a favorable safety profile.

According to the indication, rivaroxaban can be administered to patients during hospitalization and can be continued after discharge for 31-39 days. The safety profile in MAGELLAN and MARINER was consistent with that already seen, with the most common adverse event being bleeding.

The new indication is the eighth for rivaroxaban, the most of any direct oral anticoagulant; six of these are specifically for the treatment, prevention, and reduction in the risk of VTE recurrence.

“With this new approval, Xarelto as an oral-only option now has the potential to change how acutely ill medical patients are managed for the prevention of blood clots, both in the hospital and for an extended period after discharge,” said Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and a member of the steering committee of the MAGELLAN trial.

Find the full press release on the Janssen website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved rivaroxaban (Xarelto) for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized, acutely ill patients at risk for thromboembolic complications who do not have a high bleeding risk, according to a release from Janssen.

FDA approval for the new indication is based on results from the phase 3 MAGELLAN and MARINER trials, which included more than 20,000 hospitalized, acutely ill patients. In MAGELLAN, rivaroxaban demonstrated noninferiority to enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, in short-term usage, and it was superior over the long term, compared with short-term enoxaparin followed by placebo.

While VTE and VTE-related deaths were not reduced in MARINER, compared with placebo, patients who received rivaroxaban did see a significantly reduction in symptomatic VTE with a favorable safety profile.

According to the indication, rivaroxaban can be administered to patients during hospitalization and can be continued after discharge for 31-39 days. The safety profile in MAGELLAN and MARINER was consistent with that already seen, with the most common adverse event being bleeding.

The new indication is the eighth for rivaroxaban, the most of any direct oral anticoagulant; six of these are specifically for the treatment, prevention, and reduction in the risk of VTE recurrence.

“With this new approval, Xarelto as an oral-only option now has the potential to change how acutely ill medical patients are managed for the prevention of blood clots, both in the hospital and for an extended period after discharge,” said Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and a member of the steering committee of the MAGELLAN trial.

Find the full press release on the Janssen website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved rivaroxaban (Xarelto) for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized, acutely ill patients at risk for thromboembolic complications who do not have a high bleeding risk, according to a release from Janssen.

FDA approval for the new indication is based on results from the phase 3 MAGELLAN and MARINER trials, which included more than 20,000 hospitalized, acutely ill patients. In MAGELLAN, rivaroxaban demonstrated noninferiority to enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, in short-term usage, and it was superior over the long term, compared with short-term enoxaparin followed by placebo.

While VTE and VTE-related deaths were not reduced in MARINER, compared with placebo, patients who received rivaroxaban did see a significantly reduction in symptomatic VTE with a favorable safety profile.

According to the indication, rivaroxaban can be administered to patients during hospitalization and can be continued after discharge for 31-39 days. The safety profile in MAGELLAN and MARINER was consistent with that already seen, with the most common adverse event being bleeding.

The new indication is the eighth for rivaroxaban, the most of any direct oral anticoagulant; six of these are specifically for the treatment, prevention, and reduction in the risk of VTE recurrence.

“With this new approval, Xarelto as an oral-only option now has the potential to change how acutely ill medical patients are managed for the prevention of blood clots, both in the hospital and for an extended period after discharge,” said Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, and a member of the steering committee of the MAGELLAN trial.

Find the full press release on the Janssen website.

Rivaroxaban trends toward higher thrombotic risk than vitamin K antagonists in APS

suggests a recent trial conducted in Spain.

Stroke was also more common among those taking rivaroxaban, while major bleeding was slightly less common, reported lead author Josep Ordi-Ros, MD, PhD, of Vall d’Hebrón University Hospital Research Institute in Barcelona, and colleagues in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Two randomized, controlled trials comparing rivaroxaban with warfarin suggested that rivaroxaban may be efficacious in patients with previous venous thromboembolism who are receiving standard-intensity anticoagulation but showed an increased thrombotic risk in those with triple-positive antiphospholipid antibodies,” the investigators wrote. However, they also noted that these findings required a cautious interpretation because of study limitations, such as premature termination caused by an excess of study events and the use of a laboratory surrogate marker as a primary outcome.

To learn more, the investigators performed an open-label, phase 3 trial involving 190 patients with thrombotic APS. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either rivaroxaban (20 mg per day, or 15 mg per day for patients with a creatinine clearance of 30-49 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or an adjusted dosage of vitamin K antagonists (target international normalized ratio of 2.0-3.0, or 3.1-4.0 for those with a history of recurrent thrombosis).

Patients underwent evaluations every month for the first 3 months and then every 3 months thereafter, each of which involved a variety of laboratory diagnostics such as checks for antinuclear antibodies and lupus anticoagulant, among others. Statistical analyses aimed to determine if rivaroxaban was noninferior to therapy with vitamin K antagonists based on parameters drawn from previous meta-analyses, as no studies had compared the two types of treatment when the present study was designed.

After 3 years of follow-up, almost twice as many patients in the rivaroxaban group had experienced recurrent thrombosis (11.6% vs. 6.3%), although this finding lacked statistical significance for both noninferiority of rivaroxaban (P = .29) and superiority of vitamin K antagonists (P = .20). Still, supporting a similar trend toward differences in efficacy, stroke was more common in the rivaroxaban group, in which nine events occurred, compared with none in the vitamin K antagonist group. In contrast, major bleeding was slightly less common with rivaroxaban than vitamin K antagonists (6.3% vs. 7.4%).

“In conclusion, rivaroxaban did not demonstrate noninferiority to dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists for secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with thrombotic APS,” the investigators wrote. “Instead, our results indicate a recurrent thrombotic rate that is nearly double, albeit without statistical significance.”

The study was funded by Bayer Hispania. One coauthor reported additional relationships with Pfizer, Lilly, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Ordi-Ros J et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

The recent trial by Ordi-Ros et al. revealed similar findings to a previous trial, TRAPS, by Pengo et al., which compared rivaroxaban with warfarin among patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome and triple positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies. Despite the caveat that TRAPS was prematurely terminated, in both studies, a higher proportion of patients in the rivaroxaban group than the vitamin K antagonist group had thrombotic events, most of which were arterial, whether considering MI or stroke. Furthermore, both studies did not show noninferiority of rivaroxaban versus dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists.

The reasons for this failure of noninferiority remain unclear.

Denis Wahl, MD, PhD, and Virginie Dufrost, MD, are with the University of Lorraine, Nancy, France, and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nancy. No conflicts of interest were reported. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-2815).

The recent trial by Ordi-Ros et al. revealed similar findings to a previous trial, TRAPS, by Pengo et al., which compared rivaroxaban with warfarin among patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome and triple positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies. Despite the caveat that TRAPS was prematurely terminated, in both studies, a higher proportion of patients in the rivaroxaban group than the vitamin K antagonist group had thrombotic events, most of which were arterial, whether considering MI or stroke. Furthermore, both studies did not show noninferiority of rivaroxaban versus dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists.

The reasons for this failure of noninferiority remain unclear.

Denis Wahl, MD, PhD, and Virginie Dufrost, MD, are with the University of Lorraine, Nancy, France, and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nancy. No conflicts of interest were reported. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-2815).

The recent trial by Ordi-Ros et al. revealed similar findings to a previous trial, TRAPS, by Pengo et al., which compared rivaroxaban with warfarin among patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome and triple positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies. Despite the caveat that TRAPS was prematurely terminated, in both studies, a higher proportion of patients in the rivaroxaban group than the vitamin K antagonist group had thrombotic events, most of which were arterial, whether considering MI or stroke. Furthermore, both studies did not show noninferiority of rivaroxaban versus dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists.

The reasons for this failure of noninferiority remain unclear.

Denis Wahl, MD, PhD, and Virginie Dufrost, MD, are with the University of Lorraine, Nancy, France, and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nancy. No conflicts of interest were reported. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-2815).

suggests a recent trial conducted in Spain.

Stroke was also more common among those taking rivaroxaban, while major bleeding was slightly less common, reported lead author Josep Ordi-Ros, MD, PhD, of Vall d’Hebrón University Hospital Research Institute in Barcelona, and colleagues in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Two randomized, controlled trials comparing rivaroxaban with warfarin suggested that rivaroxaban may be efficacious in patients with previous venous thromboembolism who are receiving standard-intensity anticoagulation but showed an increased thrombotic risk in those with triple-positive antiphospholipid antibodies,” the investigators wrote. However, they also noted that these findings required a cautious interpretation because of study limitations, such as premature termination caused by an excess of study events and the use of a laboratory surrogate marker as a primary outcome.

To learn more, the investigators performed an open-label, phase 3 trial involving 190 patients with thrombotic APS. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either rivaroxaban (20 mg per day, or 15 mg per day for patients with a creatinine clearance of 30-49 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or an adjusted dosage of vitamin K antagonists (target international normalized ratio of 2.0-3.0, or 3.1-4.0 for those with a history of recurrent thrombosis).

Patients underwent evaluations every month for the first 3 months and then every 3 months thereafter, each of which involved a variety of laboratory diagnostics such as checks for antinuclear antibodies and lupus anticoagulant, among others. Statistical analyses aimed to determine if rivaroxaban was noninferior to therapy with vitamin K antagonists based on parameters drawn from previous meta-analyses, as no studies had compared the two types of treatment when the present study was designed.

After 3 years of follow-up, almost twice as many patients in the rivaroxaban group had experienced recurrent thrombosis (11.6% vs. 6.3%), although this finding lacked statistical significance for both noninferiority of rivaroxaban (P = .29) and superiority of vitamin K antagonists (P = .20). Still, supporting a similar trend toward differences in efficacy, stroke was more common in the rivaroxaban group, in which nine events occurred, compared with none in the vitamin K antagonist group. In contrast, major bleeding was slightly less common with rivaroxaban than vitamin K antagonists (6.3% vs. 7.4%).

“In conclusion, rivaroxaban did not demonstrate noninferiority to dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists for secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with thrombotic APS,” the investigators wrote. “Instead, our results indicate a recurrent thrombotic rate that is nearly double, albeit without statistical significance.”

The study was funded by Bayer Hispania. One coauthor reported additional relationships with Pfizer, Lilly, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Ordi-Ros J et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

suggests a recent trial conducted in Spain.

Stroke was also more common among those taking rivaroxaban, while major bleeding was slightly less common, reported lead author Josep Ordi-Ros, MD, PhD, of Vall d’Hebrón University Hospital Research Institute in Barcelona, and colleagues in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Two randomized, controlled trials comparing rivaroxaban with warfarin suggested that rivaroxaban may be efficacious in patients with previous venous thromboembolism who are receiving standard-intensity anticoagulation but showed an increased thrombotic risk in those with triple-positive antiphospholipid antibodies,” the investigators wrote. However, they also noted that these findings required a cautious interpretation because of study limitations, such as premature termination caused by an excess of study events and the use of a laboratory surrogate marker as a primary outcome.

To learn more, the investigators performed an open-label, phase 3 trial involving 190 patients with thrombotic APS. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either rivaroxaban (20 mg per day, or 15 mg per day for patients with a creatinine clearance of 30-49 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or an adjusted dosage of vitamin K antagonists (target international normalized ratio of 2.0-3.0, or 3.1-4.0 for those with a history of recurrent thrombosis).

Patients underwent evaluations every month for the first 3 months and then every 3 months thereafter, each of which involved a variety of laboratory diagnostics such as checks for antinuclear antibodies and lupus anticoagulant, among others. Statistical analyses aimed to determine if rivaroxaban was noninferior to therapy with vitamin K antagonists based on parameters drawn from previous meta-analyses, as no studies had compared the two types of treatment when the present study was designed.

After 3 years of follow-up, almost twice as many patients in the rivaroxaban group had experienced recurrent thrombosis (11.6% vs. 6.3%), although this finding lacked statistical significance for both noninferiority of rivaroxaban (P = .29) and superiority of vitamin K antagonists (P = .20). Still, supporting a similar trend toward differences in efficacy, stroke was more common in the rivaroxaban group, in which nine events occurred, compared with none in the vitamin K antagonist group. In contrast, major bleeding was slightly less common with rivaroxaban than vitamin K antagonists (6.3% vs. 7.4%).

“In conclusion, rivaroxaban did not demonstrate noninferiority to dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists for secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with thrombotic APS,” the investigators wrote. “Instead, our results indicate a recurrent thrombotic rate that is nearly double, albeit without statistical significance.”

The study was funded by Bayer Hispania. One coauthor reported additional relationships with Pfizer, Lilly, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Ordi-Ros J et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 15. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Ticagrelor monotherapy tops DAPT for high-risk PCI patients

SAN FRANCISCO – After 3 months of ticagrelor (Brilinta) plus aspirin following cardiac stenting, stopping the aspirin but continuing the ticagrelor resulted in less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events in a randomized trial with more than 7,000 drug-eluting stent patients at high risk for both.

“This was a superior therapy” to staying on both drugs, the more usual approach, said lead investigator Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“We can’t say this is for all comers, but for patients whose physician felt comfortable putting them on aspirin and ticagrelor,” who tolerated it well for the first 3 months, and who had clinical and angiographic indications of risk, “I think these patients can be peeled away” from aspirin, she said in a presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting that coincided with publication of the trial, dubbed TWILIGHT (Ticagrelor with Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention).

Interventional cardiologists have long sought the sweet spot for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after stenting; the idea is to maximize thrombosis prevention while minimizing bleeding risk. The trial supports the trend in recent years towards shorter DAPT. Often, however, it’s the P2Y12 inhibitor – ticagrelor, clopidogrel (Plavix), or prasugrel (Effient) – that goes first, not the aspirin.

Responding to an audience question about why the trial didn’t include an aspirin monotherapy arm, Dr. Mehran said that aspirin alone wouldn’t have been sufficient in high-risk patients “in whom you have almost 70% acute coronary syndrome.” She added that her team has data showing that aspirin itself doesn’t have much effect on blood thrombogenicity.

The 7,119 patients in TWILIGHT were on ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and aspirin 81-100 mg daily for 3 months, then evenly randomized to continued treatment or ticagrelor plus an aspirin placebo for a year.

Subjects had to have at least one clinical and angiographic finding that put them at high risk for bleeding or an ischemic event, such as chronic kidney disease, acute coronary syndrome, diabetes, or a bifurcated target lesion treated with two stents.

One year after randomization, 4% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group versus 7.1% in the ticagrelor plus aspirin arm reached the primary end point, actionable (type 2), severe (type 3), or fatal (type 5) bleeding on the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.45 - 0.68, P less than .001).

The incidence of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was 3.9% in both groups (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.25; P less than .001 for noninferiority).

There were more ischemic strokes in the ticagrelor monotherapy arm (0.5% versus 0.2%). All-cause mortality (1.3% versus 1%) and stent thrombosis (0.6% versus 0.4%) were more frequent in the ticagrelor/aspirin group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The two groups were well balanced. The mean age was 65 years, 23.8% of the patients were female, 37% had diabetes, and 65% had percutaneous coronary intervention for an acute coronary syndrome. Almost two-thirds had multivessel disease. Mean stent length was about 40 mm. The trial excluded patients with prior strokes.

Almost 2,000 patients originally enrolled in the trial never made it to randomization because they had a major bleeding or ischemic event in the 3-month run up, or dyspnea or some other reaction to ticagrelor.

The recent STOPDAPT-2 trial had a similar outcome – less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events – with clopidogrel monotherapy after a month-long run in of dual therapy with aspirin, versus continued treatment with both, in patients at low risk for ischemic events after stenting (JAMA. 2019 Jun 25;321[24]:2414-27).

Another recent study, GLOBAL LEADERS, concluded that 1 month of DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months was not superior to 12 months of DAPT followed by a year of aspirin. There was a numerical advantage for solo ticagrelor on death, myocardial infarction, and bleeding, but it did not reach statistical significance (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:940-9).

The work was funded by ticagrelor’s maker, AstraZeneca. Dr. Mehran reported consulting and other relationships with Abbott, Janssen, and other companies.

SOURCE: Mehran A et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419.

SAN FRANCISCO – After 3 months of ticagrelor (Brilinta) plus aspirin following cardiac stenting, stopping the aspirin but continuing the ticagrelor resulted in less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events in a randomized trial with more than 7,000 drug-eluting stent patients at high risk for both.

“This was a superior therapy” to staying on both drugs, the more usual approach, said lead investigator Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“We can’t say this is for all comers, but for patients whose physician felt comfortable putting them on aspirin and ticagrelor,” who tolerated it well for the first 3 months, and who had clinical and angiographic indications of risk, “I think these patients can be peeled away” from aspirin, she said in a presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting that coincided with publication of the trial, dubbed TWILIGHT (Ticagrelor with Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention).

Interventional cardiologists have long sought the sweet spot for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after stenting; the idea is to maximize thrombosis prevention while minimizing bleeding risk. The trial supports the trend in recent years towards shorter DAPT. Often, however, it’s the P2Y12 inhibitor – ticagrelor, clopidogrel (Plavix), or prasugrel (Effient) – that goes first, not the aspirin.

Responding to an audience question about why the trial didn’t include an aspirin monotherapy arm, Dr. Mehran said that aspirin alone wouldn’t have been sufficient in high-risk patients “in whom you have almost 70% acute coronary syndrome.” She added that her team has data showing that aspirin itself doesn’t have much effect on blood thrombogenicity.

The 7,119 patients in TWILIGHT were on ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and aspirin 81-100 mg daily for 3 months, then evenly randomized to continued treatment or ticagrelor plus an aspirin placebo for a year.

Subjects had to have at least one clinical and angiographic finding that put them at high risk for bleeding or an ischemic event, such as chronic kidney disease, acute coronary syndrome, diabetes, or a bifurcated target lesion treated with two stents.

One year after randomization, 4% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group versus 7.1% in the ticagrelor plus aspirin arm reached the primary end point, actionable (type 2), severe (type 3), or fatal (type 5) bleeding on the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.45 - 0.68, P less than .001).

The incidence of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was 3.9% in both groups (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.25; P less than .001 for noninferiority).

There were more ischemic strokes in the ticagrelor monotherapy arm (0.5% versus 0.2%). All-cause mortality (1.3% versus 1%) and stent thrombosis (0.6% versus 0.4%) were more frequent in the ticagrelor/aspirin group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The two groups were well balanced. The mean age was 65 years, 23.8% of the patients were female, 37% had diabetes, and 65% had percutaneous coronary intervention for an acute coronary syndrome. Almost two-thirds had multivessel disease. Mean stent length was about 40 mm. The trial excluded patients with prior strokes.

Almost 2,000 patients originally enrolled in the trial never made it to randomization because they had a major bleeding or ischemic event in the 3-month run up, or dyspnea or some other reaction to ticagrelor.

The recent STOPDAPT-2 trial had a similar outcome – less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events – with clopidogrel monotherapy after a month-long run in of dual therapy with aspirin, versus continued treatment with both, in patients at low risk for ischemic events after stenting (JAMA. 2019 Jun 25;321[24]:2414-27).

Another recent study, GLOBAL LEADERS, concluded that 1 month of DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months was not superior to 12 months of DAPT followed by a year of aspirin. There was a numerical advantage for solo ticagrelor on death, myocardial infarction, and bleeding, but it did not reach statistical significance (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:940-9).

The work was funded by ticagrelor’s maker, AstraZeneca. Dr. Mehran reported consulting and other relationships with Abbott, Janssen, and other companies.

SOURCE: Mehran A et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419.

SAN FRANCISCO – After 3 months of ticagrelor (Brilinta) plus aspirin following cardiac stenting, stopping the aspirin but continuing the ticagrelor resulted in less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events in a randomized trial with more than 7,000 drug-eluting stent patients at high risk for both.

“This was a superior therapy” to staying on both drugs, the more usual approach, said lead investigator Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“We can’t say this is for all comers, but for patients whose physician felt comfortable putting them on aspirin and ticagrelor,” who tolerated it well for the first 3 months, and who had clinical and angiographic indications of risk, “I think these patients can be peeled away” from aspirin, she said in a presentation at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting that coincided with publication of the trial, dubbed TWILIGHT (Ticagrelor with Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention).

Interventional cardiologists have long sought the sweet spot for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after stenting; the idea is to maximize thrombosis prevention while minimizing bleeding risk. The trial supports the trend in recent years towards shorter DAPT. Often, however, it’s the P2Y12 inhibitor – ticagrelor, clopidogrel (Plavix), or prasugrel (Effient) – that goes first, not the aspirin.

Responding to an audience question about why the trial didn’t include an aspirin monotherapy arm, Dr. Mehran said that aspirin alone wouldn’t have been sufficient in high-risk patients “in whom you have almost 70% acute coronary syndrome.” She added that her team has data showing that aspirin itself doesn’t have much effect on blood thrombogenicity.

The 7,119 patients in TWILIGHT were on ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and aspirin 81-100 mg daily for 3 months, then evenly randomized to continued treatment or ticagrelor plus an aspirin placebo for a year.

Subjects had to have at least one clinical and angiographic finding that put them at high risk for bleeding or an ischemic event, such as chronic kidney disease, acute coronary syndrome, diabetes, or a bifurcated target lesion treated with two stents.

One year after randomization, 4% in the ticagrelor monotherapy group versus 7.1% in the ticagrelor plus aspirin arm reached the primary end point, actionable (type 2), severe (type 3), or fatal (type 5) bleeding on the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.45 - 0.68, P less than .001).

The incidence of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was 3.9% in both groups (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.25; P less than .001 for noninferiority).

There were more ischemic strokes in the ticagrelor monotherapy arm (0.5% versus 0.2%). All-cause mortality (1.3% versus 1%) and stent thrombosis (0.6% versus 0.4%) were more frequent in the ticagrelor/aspirin group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The two groups were well balanced. The mean age was 65 years, 23.8% of the patients were female, 37% had diabetes, and 65% had percutaneous coronary intervention for an acute coronary syndrome. Almost two-thirds had multivessel disease. Mean stent length was about 40 mm. The trial excluded patients with prior strokes.

Almost 2,000 patients originally enrolled in the trial never made it to randomization because they had a major bleeding or ischemic event in the 3-month run up, or dyspnea or some other reaction to ticagrelor.

The recent STOPDAPT-2 trial had a similar outcome – less bleeding with no increase in ischemic events – with clopidogrel monotherapy after a month-long run in of dual therapy with aspirin, versus continued treatment with both, in patients at low risk for ischemic events after stenting (JAMA. 2019 Jun 25;321[24]:2414-27).

Another recent study, GLOBAL LEADERS, concluded that 1 month of DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months was not superior to 12 months of DAPT followed by a year of aspirin. There was a numerical advantage for solo ticagrelor on death, myocardial infarction, and bleeding, but it did not reach statistical significance (Lancet. 2018 Sep 15;392[10151]:940-9).

The work was funded by ticagrelor’s maker, AstraZeneca. Dr. Mehran reported consulting and other relationships with Abbott, Janssen, and other companies.

SOURCE: Mehran A et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2019

Apixaban prevents clots with cancer

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.

Bottom line: VTE is significantly lower with the use of apixaban, compared with placebo, in intermediate- to high-risk ambulatory patients with active cancer who are initiating chemotherapy.

Citation: Carrier M et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.

Bottom line: VTE is significantly lower with the use of apixaban, compared with placebo, in intermediate- to high-risk ambulatory patients with active cancer who are initiating chemotherapy.

Citation: Carrier M et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.

Dr. Trammell Velasquez is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Background: Active cancer places patients at increased risk for VTE. Ambulatory patients can be risk stratified using the validated Khorana score to assess risk for VTE, a complication resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Study design: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting: Ambulatory; Canada.

Synopsis: A total of 1,809 patients were assessed for eligibility, 1,235 were excluded, and 574 with a Khorana score of 2 or higher were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo. Treatment or placebo was given within 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy and continued for 180 days. The primary efficacy outcome – first episode of major VTE within 180 days of randomization – occurred in 4.2% of the apixaban group and in 10.2% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.65; P less than .001). Major bleeding in the modified intention-to-treat analysis occurred in 3.5% in the apixaban group and 1.8% in the placebo group (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.01-3.95; P = .046).

There was no significant difference in overall survival, with 87% of deaths were related to cancer or cancer progression.