User login

Solar Urticaria Treated With Omalizumab

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

Practice Points

- Recurrent solar urticaria can be recalcitrant to treatment.

- Omalizumab may be an effective treatment option for solar urticaria, especially in patients with a concomitant asthma diagnosis.

Chronic urticaria population identified

Half a million people. That’s pretty close to the population of Sacramento. It’s also the estimated number of adults living with chronic urticaria in the United States, according to analysis of a database including over 55 million individuals.

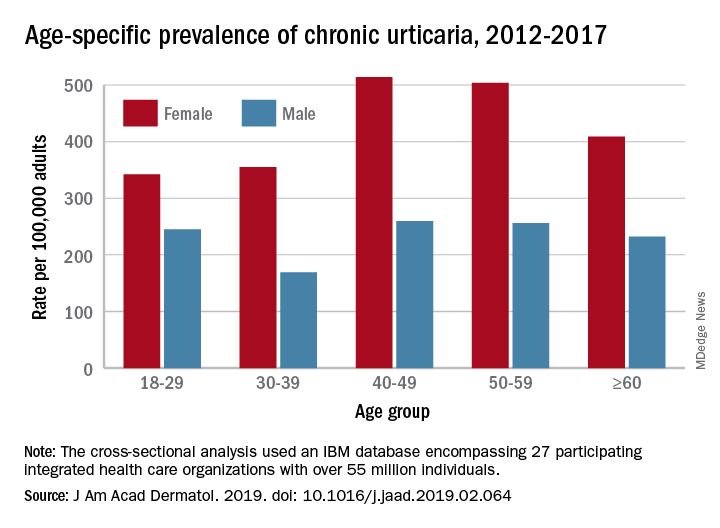

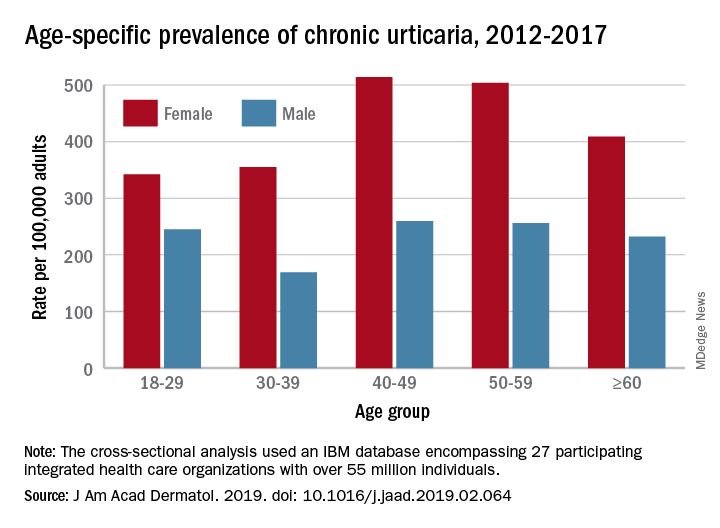

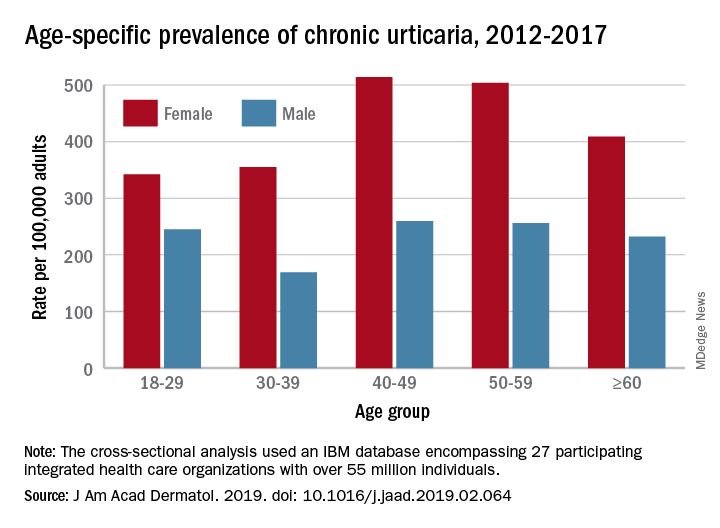

That cross-sectional analysis put the overall standardized at 309.3 per 100,000 (0.31%) and men well below at 145.5 per 100,000 (0.15%), Sara Wertenteil, BA, and her associates at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall prevalence of chronic urticaria was similar for all age groups, ranging from 0.21% for those aged 18-29 years and those aged 30-39 years to 0.26% for those aged 40-49, and prevalence was higher for females than males in all age groups, the investigators reported.

“Epidemiologic studies estimating disease burden for chronic urticaria are sparse, [but this study] is based on one of the largest and most ethnically diversified population samples in the United States. It is also drawn from patients with all insurance types and self-pay patients across various types of health care settings and from all census regions,” Ms. Wertenteil and her associates wrote.

The study involved an IBM Watson Health database encompassing 27 participating integrated health care organizations and representing approximately 17% of the population. The analysis identified 69,570 adult patients with chronic urticaria, and the ratio of women to men was 2.7:1.

The senior author, Amit Garg, MD, has served as an advisor for AbbVie, Pfizer, Janssen, and Asana Biosciences.

SOURCE: Wertenteil S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.064.

Half a million people. That’s pretty close to the population of Sacramento. It’s also the estimated number of adults living with chronic urticaria in the United States, according to analysis of a database including over 55 million individuals.

That cross-sectional analysis put the overall standardized at 309.3 per 100,000 (0.31%) and men well below at 145.5 per 100,000 (0.15%), Sara Wertenteil, BA, and her associates at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall prevalence of chronic urticaria was similar for all age groups, ranging from 0.21% for those aged 18-29 years and those aged 30-39 years to 0.26% for those aged 40-49, and prevalence was higher for females than males in all age groups, the investigators reported.

“Epidemiologic studies estimating disease burden for chronic urticaria are sparse, [but this study] is based on one of the largest and most ethnically diversified population samples in the United States. It is also drawn from patients with all insurance types and self-pay patients across various types of health care settings and from all census regions,” Ms. Wertenteil and her associates wrote.

The study involved an IBM Watson Health database encompassing 27 participating integrated health care organizations and representing approximately 17% of the population. The analysis identified 69,570 adult patients with chronic urticaria, and the ratio of women to men was 2.7:1.

The senior author, Amit Garg, MD, has served as an advisor for AbbVie, Pfizer, Janssen, and Asana Biosciences.

SOURCE: Wertenteil S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.064.

Half a million people. That’s pretty close to the population of Sacramento. It’s also the estimated number of adults living with chronic urticaria in the United States, according to analysis of a database including over 55 million individuals.

That cross-sectional analysis put the overall standardized at 309.3 per 100,000 (0.31%) and men well below at 145.5 per 100,000 (0.15%), Sara Wertenteil, BA, and her associates at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Overall prevalence of chronic urticaria was similar for all age groups, ranging from 0.21% for those aged 18-29 years and those aged 30-39 years to 0.26% for those aged 40-49, and prevalence was higher for females than males in all age groups, the investigators reported.

“Epidemiologic studies estimating disease burden for chronic urticaria are sparse, [but this study] is based on one of the largest and most ethnically diversified population samples in the United States. It is also drawn from patients with all insurance types and self-pay patients across various types of health care settings and from all census regions,” Ms. Wertenteil and her associates wrote.

The study involved an IBM Watson Health database encompassing 27 participating integrated health care organizations and representing approximately 17% of the population. The analysis identified 69,570 adult patients with chronic urticaria, and the ratio of women to men was 2.7:1.

The senior author, Amit Garg, MD, has served as an advisor for AbbVie, Pfizer, Janssen, and Asana Biosciences.

SOURCE: Wertenteil S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.064.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Ligelizumab maintains urticaria control for up to 1 year

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

VIDEO: Immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

Bedbugs in the Workplace

Choose your steps for treating chronic spontaneous urticaria

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”

Drug choice is largely physician preference. A 2014 Cochrane review examined 73 studies of H1-histamine blockers in 9,759 participants and found little difference between any of the drugs. “No single H1‐antihistamine stands out as most effective,” the authors concluded. “Cetirizine at 10 mg once daily in the short term and in the intermediate term was found to be effective in completely suppressing urticaria. Evidence is limited for desloratadine given at 5 mg once daily in the intermediate term and at 20 mg in the short term. Levocetirizine at 5 mg in the intermediate but not short term was effective for complete suppression. Levocetirizine 20 mg was effective in the short term, but 10 mg was not,” the study noted (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 14;[11]:CD006137).

“In my practice, we use cetirizine,” Dr. Baker said. “But if a patient is on fexofenadine, for example, and doing well, I wouldn’t change that.”

The treatment guidelines agree on the next step for unresponsive patients: Updosing the antihistamine. “You may have to jump up to four times the recommended dose,” she said. “Sometimes we do this gradually, but sometimes I go right ahead to that dose just to get the patient under control. And there’s good evidence that 50%-75% of our patients will be controlled on an updosing regimen. Just keep them on it until they are symptom free, and then you can try reducing it to see how they do.”

But even this can leave up to half of patients still itching. The next treatment step is where the guidelines diverge, Dr. Baker said. The U.S. document suggests trying several other options, including adding another second-generation antihistamine, adding an H2 agonist, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, or a sedating first-generation antihistamine.

“The European recommendation is to go straight to omalizumab,” Dr. Baker said. “They based this recommendation on the finding of insufficient evidence in the literature for any of these other things.”

Instead of recommending omalizumab to antihistamine-resistant patients, the U.S. guidelines suggest a dose-advancement trial of hydroxyzine or doxepin.

But there’s no arguing that omalizumab is highly effective for chronic urticaria, Dr. Baker noted. The 2015 ASTERIA trial perfectly illustrated the drug’s benefit for patients who were still symptomatic on optimal antihistamine treatment (J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jan;135[1]:67-75).

The 40-week, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study enrolled 319 patients, who received the injections as a monthly add-on therapy for 24 weeks in doses of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg or placebo. This was followed by 16 weeks of observation. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in weekly Itch Severity Score (ISS) at week 12.

The omalizumab 300-mg group had the best ISS scores at the end of the study. This group also met nine secondary endpoints, including a decreased time to reach the clinically important response of at least a 5-point ISS decrease.

The drug carries a low risk of adverse events, with just four patients (5%) in the omalizumab 300-mg group developing a serious side effect; none of these were judged to be related to the study drug. There is a very low risk of anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab – about 0.1% in clinical trials and 0.2% in postmarketing observational studies. A 2017 review of three omalizumab studies determined that asthma is the biggest risk factor for such a reaction.

The review found 132 patients with potential anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab. Asthma was the indication for omalizumab therapy in 80%; 43% of patients who provided an anaphylaxis history said that they had experienced a prior non–omalizumab-related reaction.

The U.S. guidelines don’t bring omalizumab into the picture until the final step, which recommends it, cyclosporine, or other unspecified biologics or immunosuppressive agents. At this point, however, the European guidelines move to a cyclosporine recommendation for the very small number of patients who were unresponsive to omalizumab.

Pivotal trials of omalizumab in urticaria used a once-monthly injection schedule, but more recent data suggest that patients who get the drug every 2 weeks may do better, Dr. Baker added. A chart review published in 2016 found a 100% response rate in patients who received twice monthly doses of 300 mg (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74[6]:1274-6).

Dr. Baker disclosed that she has been a clinical trial investigator for Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”

Drug choice is largely physician preference. A 2014 Cochrane review examined 73 studies of H1-histamine blockers in 9,759 participants and found little difference between any of the drugs. “No single H1‐antihistamine stands out as most effective,” the authors concluded. “Cetirizine at 10 mg once daily in the short term and in the intermediate term was found to be effective in completely suppressing urticaria. Evidence is limited for desloratadine given at 5 mg once daily in the intermediate term and at 20 mg in the short term. Levocetirizine at 5 mg in the intermediate but not short term was effective for complete suppression. Levocetirizine 20 mg was effective in the short term, but 10 mg was not,” the study noted (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 14;[11]:CD006137).

“In my practice, we use cetirizine,” Dr. Baker said. “But if a patient is on fexofenadine, for example, and doing well, I wouldn’t change that.”

The treatment guidelines agree on the next step for unresponsive patients: Updosing the antihistamine. “You may have to jump up to four times the recommended dose,” she said. “Sometimes we do this gradually, but sometimes I go right ahead to that dose just to get the patient under control. And there’s good evidence that 50%-75% of our patients will be controlled on an updosing regimen. Just keep them on it until they are symptom free, and then you can try reducing it to see how they do.”

But even this can leave up to half of patients still itching. The next treatment step is where the guidelines diverge, Dr. Baker said. The U.S. document suggests trying several other options, including adding another second-generation antihistamine, adding an H2 agonist, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, or a sedating first-generation antihistamine.

“The European recommendation is to go straight to omalizumab,” Dr. Baker said. “They based this recommendation on the finding of insufficient evidence in the literature for any of these other things.”

Instead of recommending omalizumab to antihistamine-resistant patients, the U.S. guidelines suggest a dose-advancement trial of hydroxyzine or doxepin.

But there’s no arguing that omalizumab is highly effective for chronic urticaria, Dr. Baker noted. The 2015 ASTERIA trial perfectly illustrated the drug’s benefit for patients who were still symptomatic on optimal antihistamine treatment (J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jan;135[1]:67-75).

The 40-week, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study enrolled 319 patients, who received the injections as a monthly add-on therapy for 24 weeks in doses of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg or placebo. This was followed by 16 weeks of observation. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in weekly Itch Severity Score (ISS) at week 12.

The omalizumab 300-mg group had the best ISS scores at the end of the study. This group also met nine secondary endpoints, including a decreased time to reach the clinically important response of at least a 5-point ISS decrease.

The drug carries a low risk of adverse events, with just four patients (5%) in the omalizumab 300-mg group developing a serious side effect; none of these were judged to be related to the study drug. There is a very low risk of anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab – about 0.1% in clinical trials and 0.2% in postmarketing observational studies. A 2017 review of three omalizumab studies determined that asthma is the biggest risk factor for such a reaction.

The review found 132 patients with potential anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab. Asthma was the indication for omalizumab therapy in 80%; 43% of patients who provided an anaphylaxis history said that they had experienced a prior non–omalizumab-related reaction.

The U.S. guidelines don’t bring omalizumab into the picture until the final step, which recommends it, cyclosporine, or other unspecified biologics or immunosuppressive agents. At this point, however, the European guidelines move to a cyclosporine recommendation for the very small number of patients who were unresponsive to omalizumab.

Pivotal trials of omalizumab in urticaria used a once-monthly injection schedule, but more recent data suggest that patients who get the drug every 2 weeks may do better, Dr. Baker added. A chart review published in 2016 found a 100% response rate in patients who received twice monthly doses of 300 mg (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74[6]:1274-6).

Dr. Baker disclosed that she has been a clinical trial investigator for Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS – in about half of patients.

But for those who don’t respond, treatment guidelines in both the United States and Europe outline a stepwise algorithm that should eventually control symptoms in about 95% of people, without continuous steroid use, Diane Baker, MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [EAACI] and the American Academy of Allergy /Global Allergy are markedly similar, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist in Portland, Ore.

The U.S. document offers a few more choices in its algorithm, while the European document sticks to a more straightforward progression of antihistamine progressing to omalizumab and then to cyclosporine.

“Both guidelines start with monotherapy of a second-generation antihistamine in the licensed dose. This has to be continuous monotherapy though. We still get patients who say, ‘My hives get better with the antihistamine, but they come back when I’m not taking it.’ Yes, patients need to understand that they have to stay on daily doses in order to control symptoms.”

Drug choice is largely physician preference. A 2014 Cochrane review examined 73 studies of H1-histamine blockers in 9,759 participants and found little difference between any of the drugs. “No single H1‐antihistamine stands out as most effective,” the authors concluded. “Cetirizine at 10 mg once daily in the short term and in the intermediate term was found to be effective in completely suppressing urticaria. Evidence is limited for desloratadine given at 5 mg once daily in the intermediate term and at 20 mg in the short term. Levocetirizine at 5 mg in the intermediate but not short term was effective for complete suppression. Levocetirizine 20 mg was effective in the short term, but 10 mg was not,” the study noted (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 14;[11]:CD006137).

“In my practice, we use cetirizine,” Dr. Baker said. “But if a patient is on fexofenadine, for example, and doing well, I wouldn’t change that.”

The treatment guidelines agree on the next step for unresponsive patients: Updosing the antihistamine. “You may have to jump up to four times the recommended dose,” she said. “Sometimes we do this gradually, but sometimes I go right ahead to that dose just to get the patient under control. And there’s good evidence that 50%-75% of our patients will be controlled on an updosing regimen. Just keep them on it until they are symptom free, and then you can try reducing it to see how they do.”

But even this can leave up to half of patients still itching. The next treatment step is where the guidelines diverge, Dr. Baker said. The U.S. document suggests trying several other options, including adding another second-generation antihistamine, adding an H2 agonist, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, or a sedating first-generation antihistamine.

“The European recommendation is to go straight to omalizumab,” Dr. Baker said. “They based this recommendation on the finding of insufficient evidence in the literature for any of these other things.”

Instead of recommending omalizumab to antihistamine-resistant patients, the U.S. guidelines suggest a dose-advancement trial of hydroxyzine or doxepin.

But there’s no arguing that omalizumab is highly effective for chronic urticaria, Dr. Baker noted. The 2015 ASTERIA trial perfectly illustrated the drug’s benefit for patients who were still symptomatic on optimal antihistamine treatment (J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jan;135[1]:67-75).

The 40-week, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled study enrolled 319 patients, who received the injections as a monthly add-on therapy for 24 weeks in doses of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg or placebo. This was followed by 16 weeks of observation. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in weekly Itch Severity Score (ISS) at week 12.

The omalizumab 300-mg group had the best ISS scores at the end of the study. This group also met nine secondary endpoints, including a decreased time to reach the clinically important response of at least a 5-point ISS decrease.

The drug carries a low risk of adverse events, with just four patients (5%) in the omalizumab 300-mg group developing a serious side effect; none of these were judged to be related to the study drug. There is a very low risk of anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab – about 0.1% in clinical trials and 0.2% in postmarketing observational studies. A 2017 review of three omalizumab studies determined that asthma is the biggest risk factor for such a reaction.

The review found 132 patients with potential anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab. Asthma was the indication for omalizumab therapy in 80%; 43% of patients who provided an anaphylaxis history said that they had experienced a prior non–omalizumab-related reaction.

The U.S. guidelines don’t bring omalizumab into the picture until the final step, which recommends it, cyclosporine, or other unspecified biologics or immunosuppressive agents. At this point, however, the European guidelines move to a cyclosporine recommendation for the very small number of patients who were unresponsive to omalizumab.

Pivotal trials of omalizumab in urticaria used a once-monthly injection schedule, but more recent data suggest that patients who get the drug every 2 weeks may do better, Dr. Baker added. A chart review published in 2016 found a 100% response rate in patients who received twice monthly doses of 300 mg (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74[6]:1274-6).

Dr. Baker disclosed that she has been a clinical trial investigator for Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

This article was updated 2/1/19.

REPORTING FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

What’s Eating You? Bedbugs

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

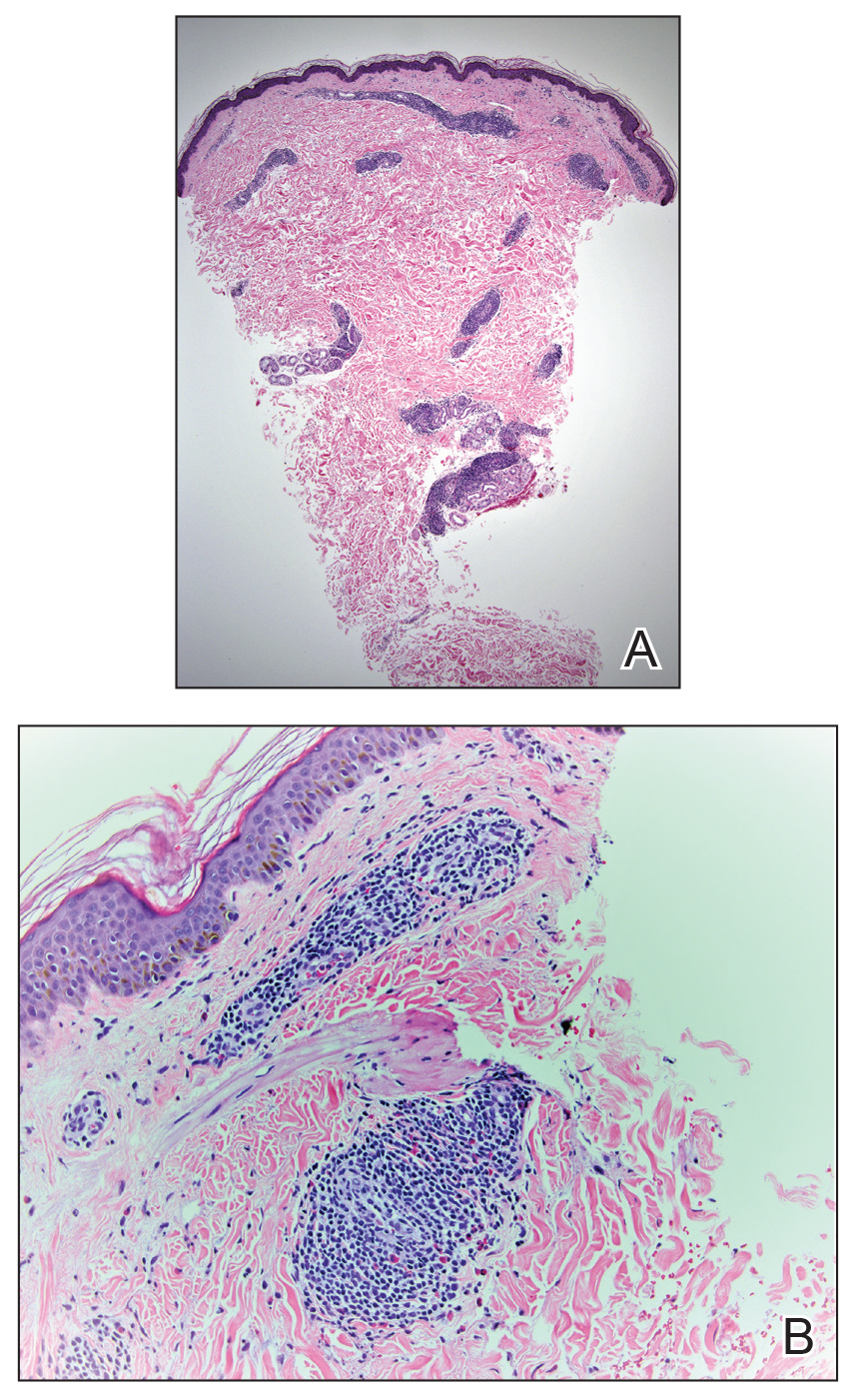

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.

Bedbugs have successfully adapted to a new environment in the office space. Dermatologists and other health care professionals can no longer exclusively associate bedbugs with the home. When the clinical and histological presentation suggests an arthropod assault, we must counsel our patients to surveil their homes and work settings alike. If necessary, they should seek the assistance of occupational health professionals.

1. Ralph N, Jones HE, Thorpe LE. Self-reported bed bug infestation among New York City residents: prevalence and risk factors. J Environ Health; 2013;76:38-45.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Bed Bugs are public health pests. EPA website. https://www.epa.gov/bedbugs/bed-bugs-are-public-health-pests. Accessed December 6, 2018.

3. Potter MF, Haynes KF, Fredericks J. Bed bugs across America: 2015 Bugs Without Borders survey. Pestworld. 2015:4-14. https://www.npmapestworld.org/default/assets/File/newsroom/magazine/2015/nov-dec_2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

4. Pinto LJ, Cooper R, Kraft SK. Bed bugs in office buildings: the ultimate challenge? MGK website. http://giecdn.blob.core.windows.net/fileuploads/file/bedbugs-office-buildings.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

5. Baumblatt JA, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. An outbreak of bed bug infestation in an office building. J Environ Health. 2014;76:16-19.

6. Parasites: bed bugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/parasites/bedbugs/biology.html. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2018.

7. Bed bugs. University of Minnesota Extension website. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/bed-bugs-in-residences. Accessed September 21, 2018.

8. Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

9. Scarupa, MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1508-1509.

10. Abdel-Naser MB, Lotfy RA, Al-Sherbiny MM, et al. Patients with papular urticaria have IgG antibodies to bedbug (Cimex lectularius) antigens. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:550-556.

11. Lai O, Ho D, Glick S, et al. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:531-538.

12. Vaidyanathan R, Feldlaufer MF. Bed bug detection: current technologies and future directions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:619-625.

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.