User login

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

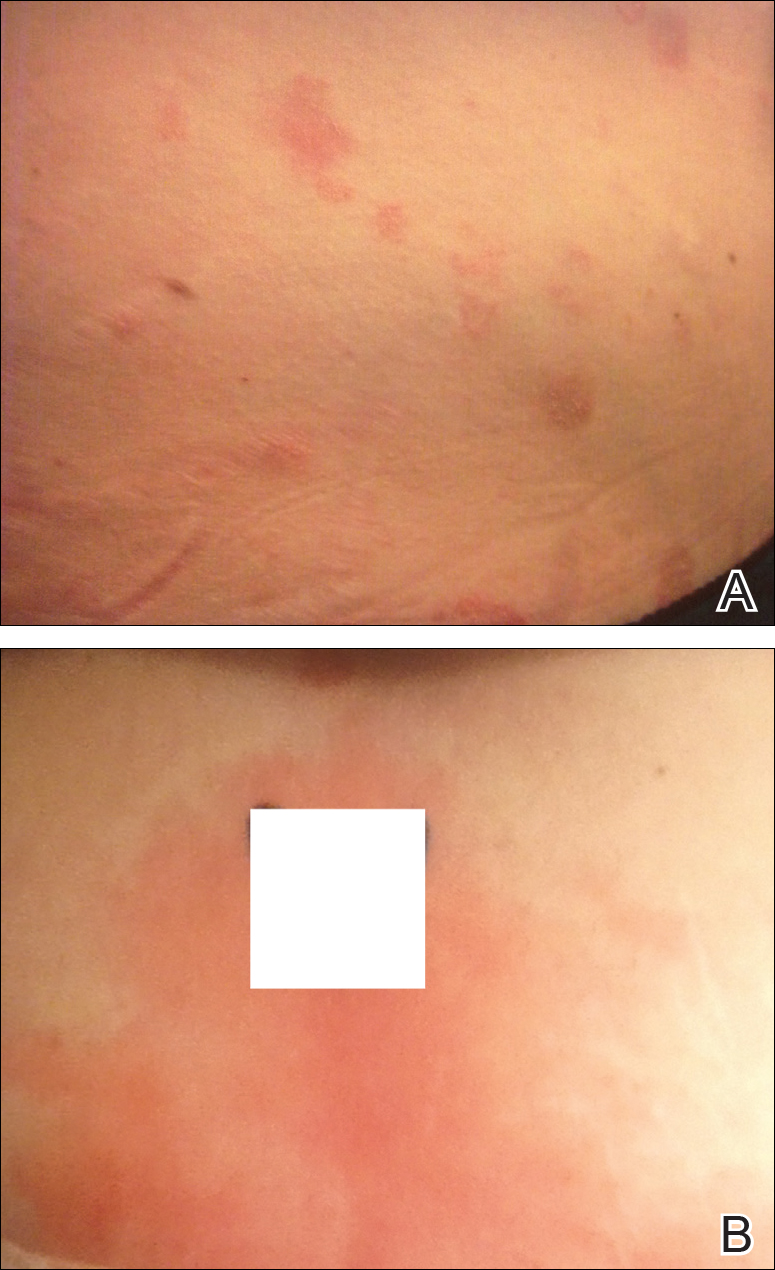

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a hypersensitivity reaction to the progesterone surge during a woman’s menstrual cycle.

- Patients with APD often are misdiagnosed for years due to the variability of each woman’s menstrual cycle, making the correlation difficult.

- It is important to keep APD in mind for any recalcitrant or recurrent rash in females. A thorough history is critical when formulating a diagnosis.

Metastatic Vulvovaginal Crohn Disease in the Setting of Well-Controlled Intestinal Disease

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

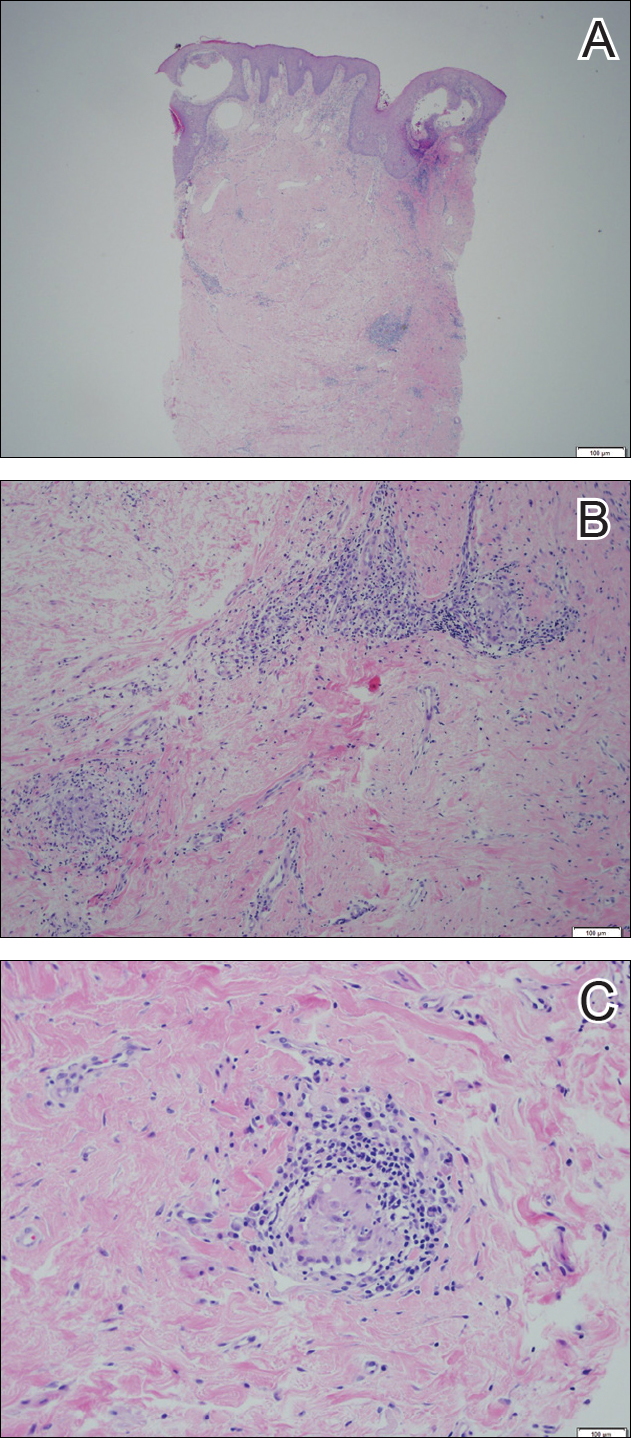

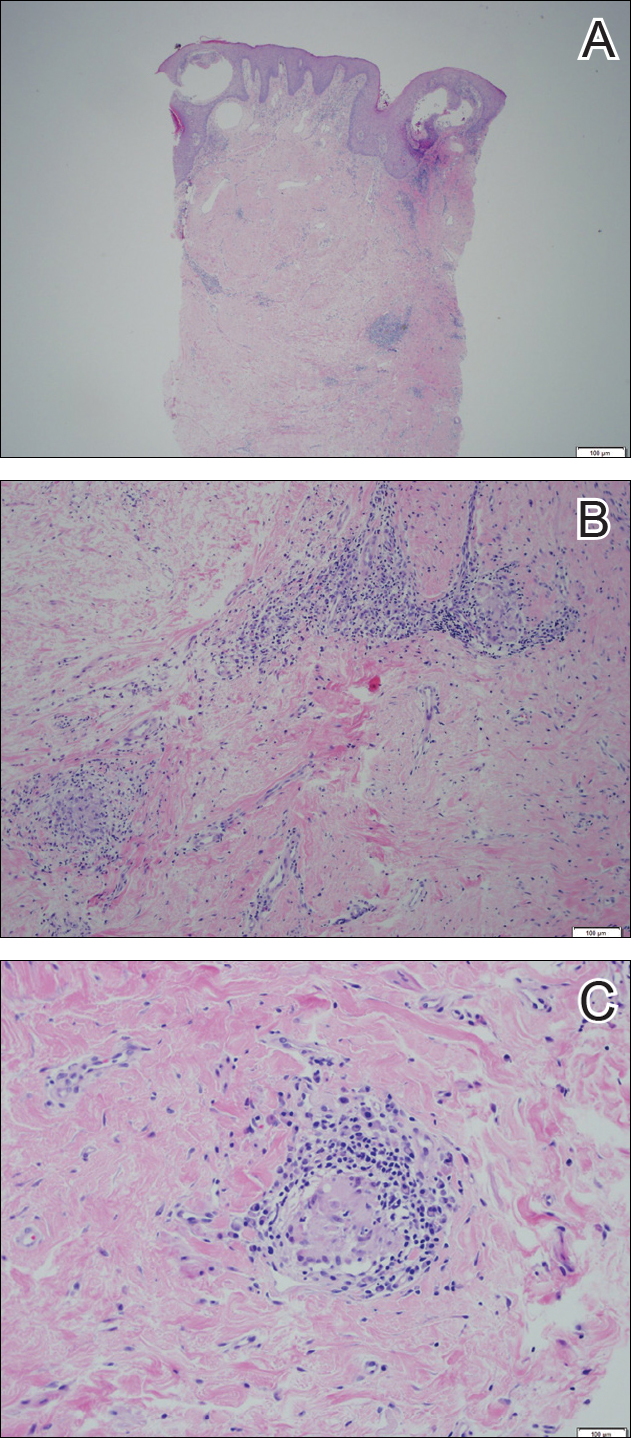

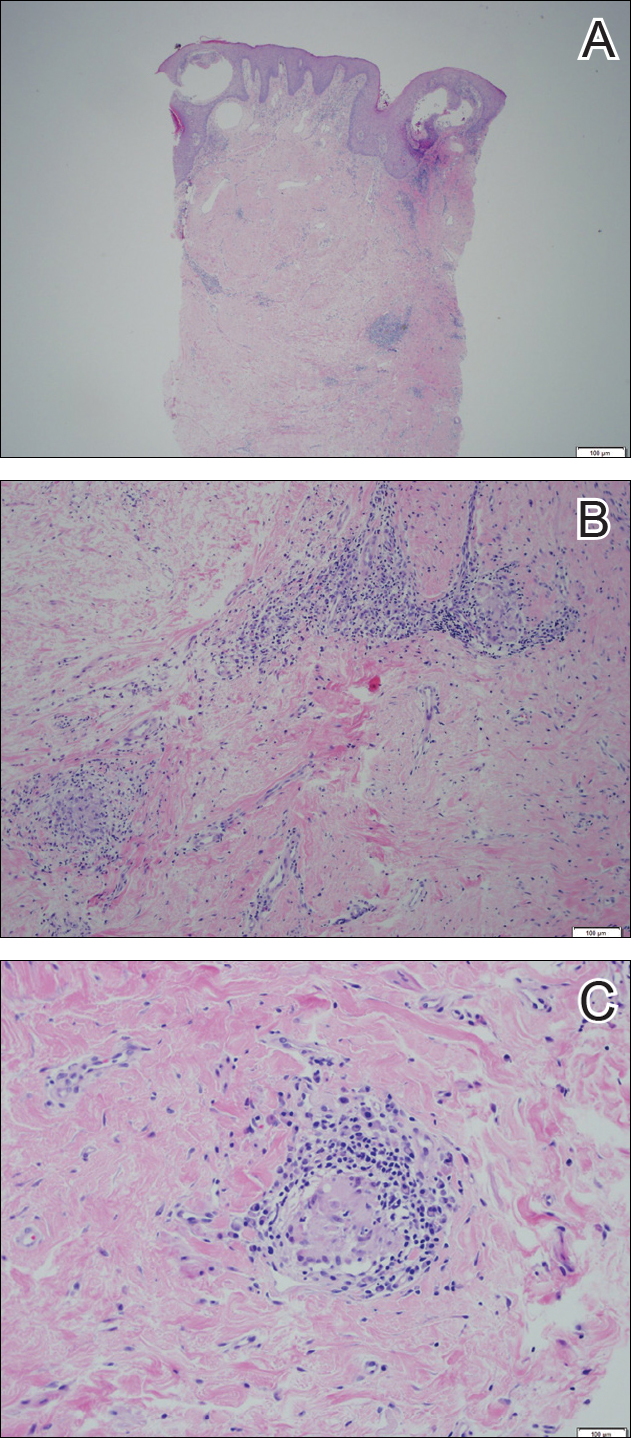

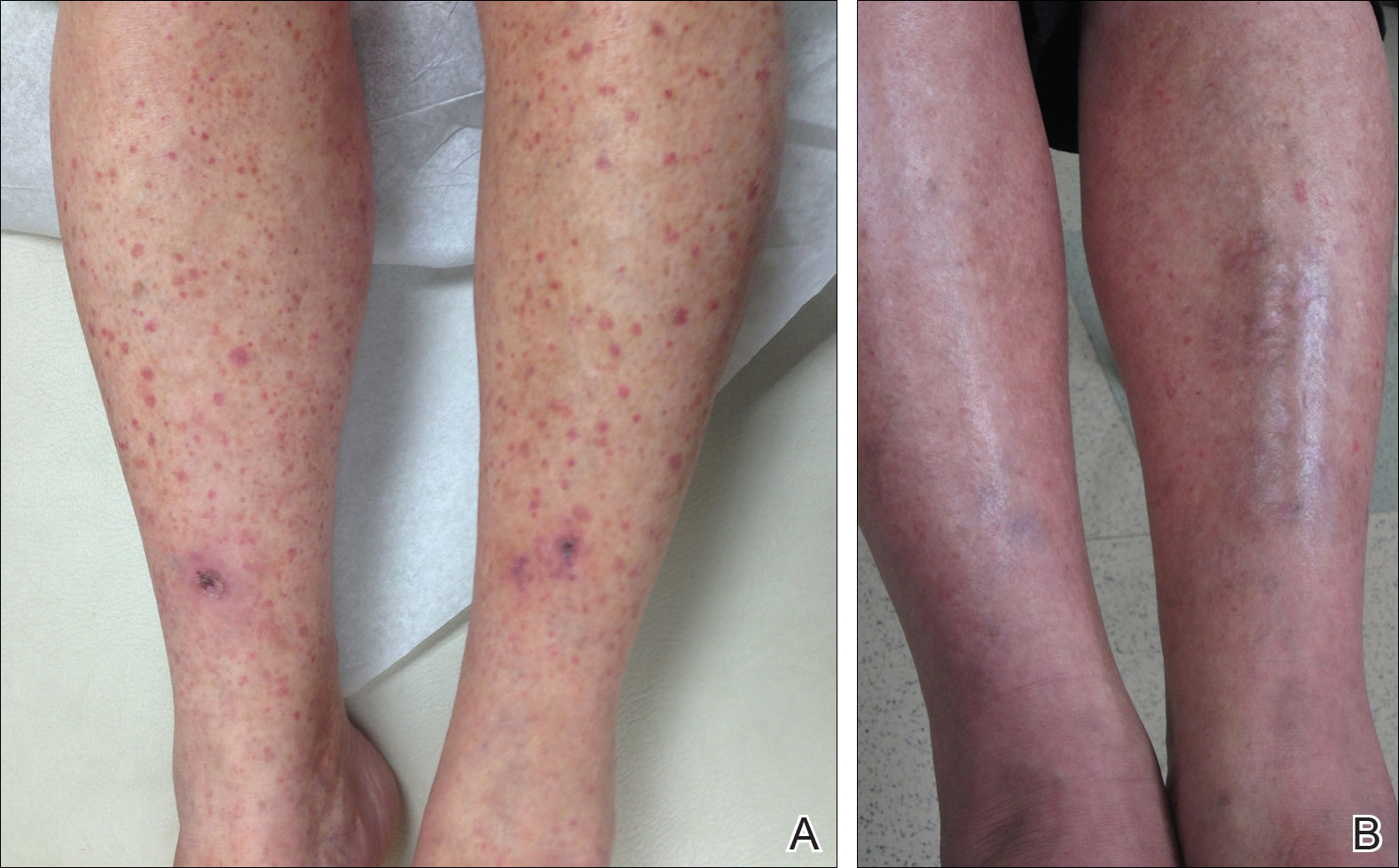

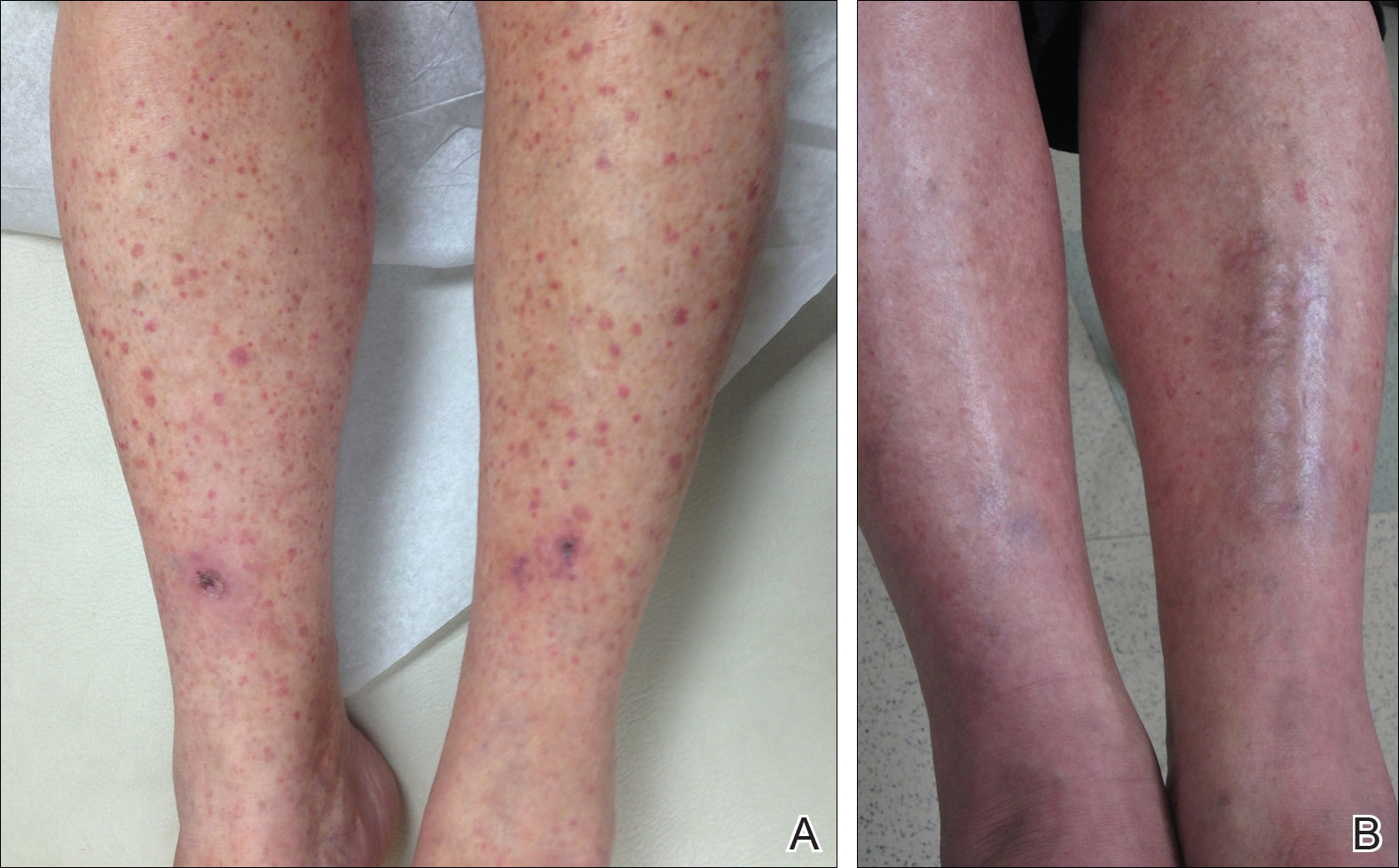

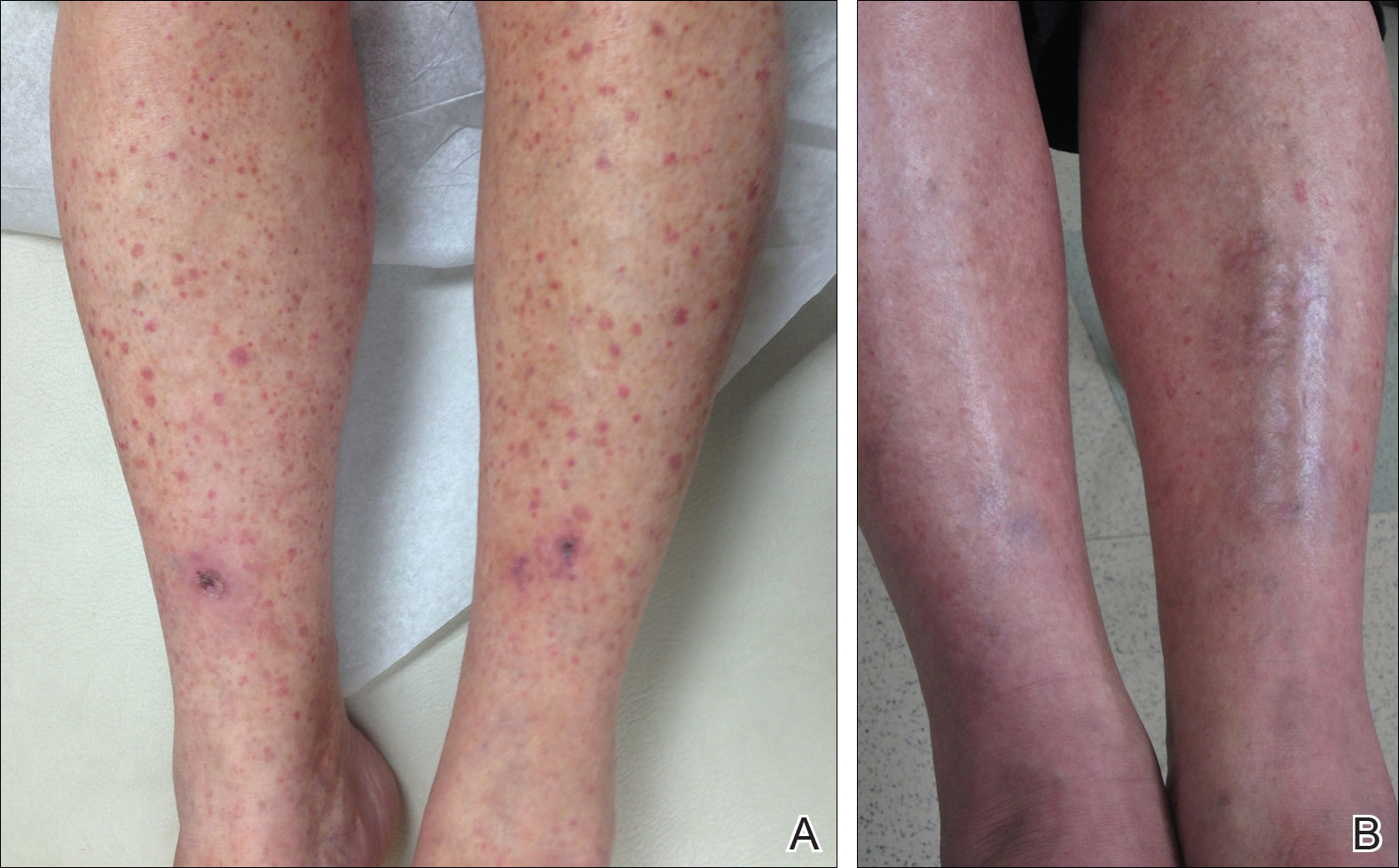

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

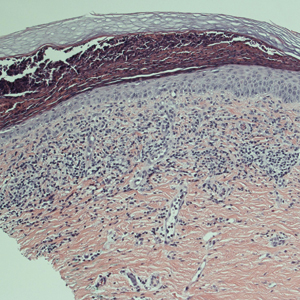

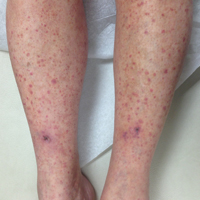

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.

Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis With Underlying Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) was originally described in 1965 and has since evolved into 3 distinct subtypes: classic, immunosuppressed (IS), and infantile types. Immunosuppressed EPF can be further subdivided into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated (IS-HIV) and non-HIV associated. Human immunodeficiency virus–seronegative cases have been associated with underlying malignancies (IS-heme) or chronic immunosuppression, such as that seen in transplant patients.

Case Report

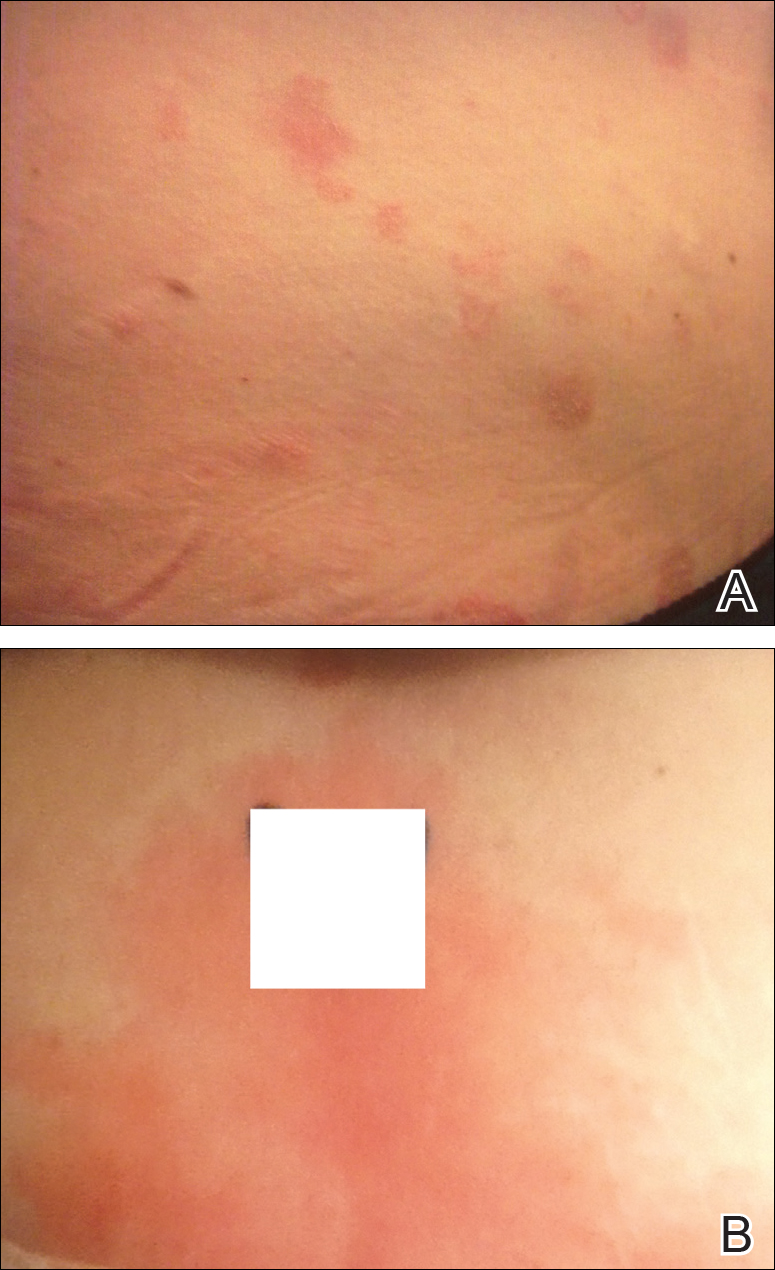

A 52-year-old man with a medical history limited to prostate adenocarcinoma treated with a robotic prostatectomy presented with a pruritic red rash on the face, neck, shoulders, and chest of 1 month’s duration. The patient previously completed a course of azithromycin 250 mg, intramuscular triamcinolone, and oral prednisone with only minor improvement. Physical examination demonstrated multiple pink folliculocentric papules and pustules scattered on the head (Figure 1A), neck, and chest (Figure 1B), as well as edematous pink papules and plaques on the forehead (Figures 1C and 1D). The palms, soles, and oral mucosa were clear.

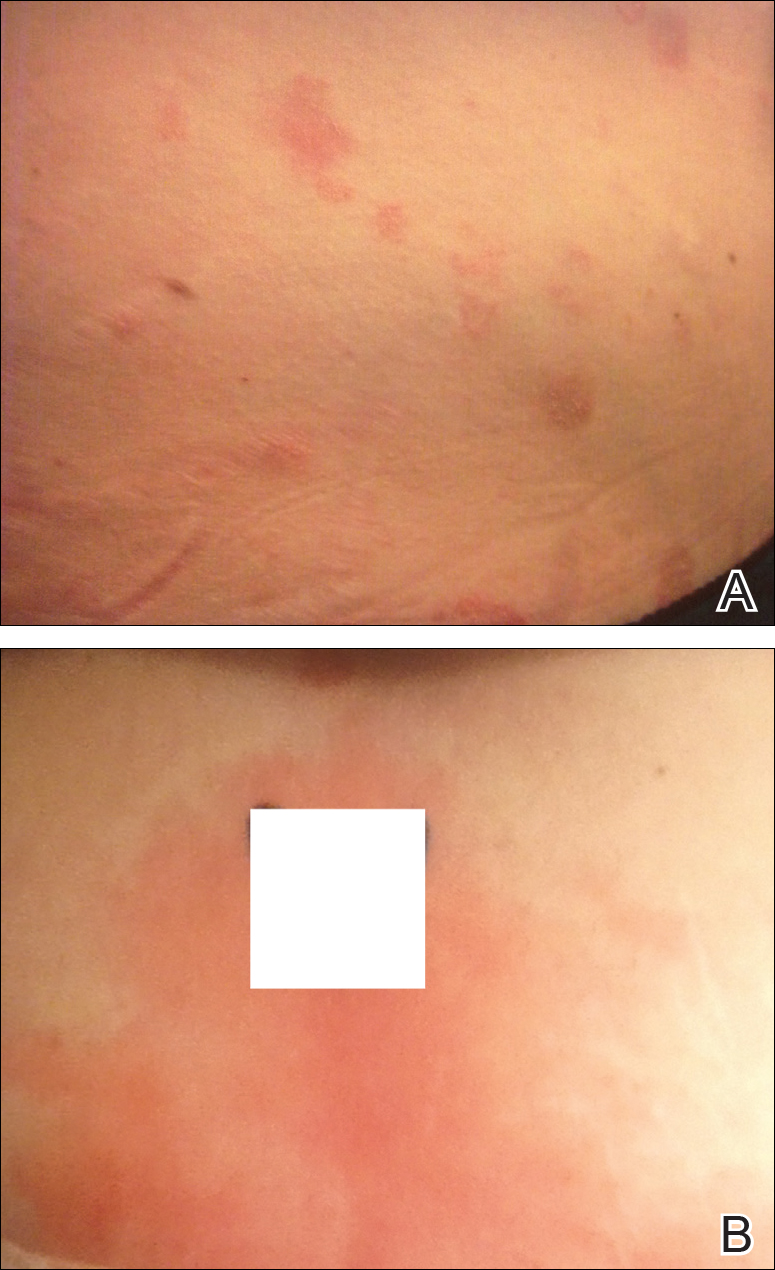

Initial biopsy of the right side of the chest was nonspecific and most consistent with a reaction to an arthropod bite. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. With no improvement seen, additional biopsies were obtained from the left side of the chest and forehead. The biopsy of the chest showed ruptured folliculitis with evidence of acute and chronic inflammation. The biopsy of the forehead demonstrated eosinophilic follicular spongiosis with intrafollicular Langerhans cell microgranulomas along with abundant eosinophils adjacent to follicles, consistent with EPF (Figure 2). Serum HIV testing was negative. Serum white blood cell count was normal at 6400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with mild elevation of eosinophils (8%). The remaining complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. The patient was subsequently started on oral indomethacin 25 mg twice daily and triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Within a few days he experienced initial improvement in his symptoms of pruritus and diminution in the number of inflammatory follicular papules.

Approximately 1 month after presentation, he began to experience symptoms of dysphagia and fatigue. In addition, tonsillar hypertrophy and palpable neck and axillary lymphadenopathy were present. Computed tomography of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed diffuse lymphadenopathy. Full-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography demonstrated extensive metabolically active lymphoma in multiple nodal groups above and below the diaphragm. There also was lymphomatous involvement of the spleen. An axillary lymph node biopsy was diagnostic for mantle cell lymphoma (CD4:CD8, 1:1; CD45 negative; CD20 positive; CD5 positive). He

Comment

Subtypes of EPF

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis was first described in a Japanese female presenting with folliculocentric pustules distributed on the face, torso, and arms.1 This noninfectious eosinophilic infiltration of hair follicles predominantly seen in the Japanese population is now regarded as the classic form. Three distinct subtypes of EPF now exist, including the originally described classic variant (Ofuji disease), an IS variant, and a rare infantile form.1

All 3 subtypes of EPF are more commonly seen in men than women. The classic form has a peak incidence between the third and fourth decades of life. It presents as chronic annular papules and sterile pustules exhibiting peripheral extension, with individual lesions lasting for approximately 7 to 10 days with frequent relapses. The face is the most common area of involvement, followed by the trunk, extremities, and more rarely the palmoplantar surfaces. Concomitant leukocytosis with eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients.1 The infantile type represents the rarest EPF form. The average age of onset is 5 months, with most cases resolving by 14 months of age.1

Clinically, EPF is characterized by recurrent papules and pustules predominantly on the scalp without annular or polycyclic ring formation, as seen in the classic type. The palms and soles may be involved, which can clinically mimic infantile acropustulosis and scabies infection. Most patients exhibit a concomitant peripheral eosinophilia.1,2

In the late 1980s, the IS variant of EPF was recognized in HIV-positive (IS-HIV) and HIV-negative malignancy-associated (IS-heme) populations.1,3 This newly characterized form differs morphologically and biologically from the classic and infantile subtypes. The IS subtype has a unique presentation including intensely pruritic, discrete, erythematous, follicular papules with palmoplantar sparing and infrequent annular or circinate plaque forms.1 Frequently, with the IS-HIV form, CD4+ T-cell counts are below 300 cells/mL, and 25% to 50% of patients have lymphopenia with eosinophilia.3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has been associated with EPF resolution in HIV-positive individuals; however, it also has been shown to induce transient EPF during the first 3 to 6 months of initiation.1,3,4

Unlike the IS-HIV form, the IS-heme form has occurred solely in males and is predominantly associated with hematologic malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome) 30 to 90 days following bone marrow transplant, peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or chemotherapy treatment.5,6 Unlike the chronic and persistent IS-HIV form, prior cases of IS-heme EPF have been predominantly self-limited. Interestingly, only 2 reported cases of EPF have occurred prior to the diagnosis of malignancy including B-cell leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.5

Histopathology

All 3 identified forms of EPF histopathologically show acute and chronic lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate concentrated at the follicular isthmus, which can lead to follicular destruction. Scattered mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are found within the pilar outer root sheath, sebaceous glands, and ducts. Approximately 40% of cases demonstrate follicular mucinosis.1 Histopathology of lesional palmar skin in classic-type EPF demonstrates intraepidermal pustule formation with abundant eosinophils and neutrophils adjacent to the acrosyringium.7,8

Pathogenesis

Although the pathophysiology of EPF is largely unknown, it is thought to represent a helper T cell (TH2) response involving IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines.9 Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2, which is expressed on eosinophils and lymphocytes, is believed to play a role in the pruritus, edema, and inflammatory response seen adjacent to pilosebaceous units in EPF.10 Moreover, immunohistochemical and flow cytometry analysis has revealed a prevalence of prostaglandin D2 within the perisebocyte infiltrate in EPF.9 Prostaglandin D2 induces eotaxin-3 production within sebocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which enhances chemoattraction of eosinophils. This pathogenesis represents a prostaglandin-based mechanism and potentially explains the efficacy of indomethacin treatment of EPF through its cyclooxygenase inhibition and reduction of chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2 expression.9-11

Treatment

Multiple therapeutic modalities have been reported for the treatment of EPF. For all 3 subtypes, moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy. UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly remains the gold standard, given its consistent efficacy.1,12 Indomethacin (50–75 mg daily) remains first-line treatment of classic EPF.4,12 Previously reported cases of classic EPF and IS-EPF have responded well to oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily).12,13 In a retrospective review of EPF treatment data, the following treatments also have been reported to be successful: psoralen plus UVA, oral cetirizine (20–40 mg daily, particularly for IS-EPF cases), metronidazole (250 mg 3 times daily), minocycline (150 mg daily), itraconazole (200–400 mg daily, dapsone (50–200 mg daily), systemic retinoids, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and permethrin cream.4,12

Malignancy

Although the entity of IS-heme EPF is rare, the morphology and treatment are unique and can potentially unmask an underlying hematologic malignancy. In patients with EPF and associated malignancy, such as our patient, a differential diagnosis to consider is eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (EDHM). Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is most commonly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and can be differentiated from EPF clinically, histopathologically, and by treatment response. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy clinically presents with nonspecific papules, pustules, and/or vesicles on the head, trunk, and extremities. On histopathology, EDHM shows a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial lymphoeosinophilic infiltration. Furthermore, EDHM patients typically exhibit a poor treatment response to oral indomethacin.14

Conclusion

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is a noninfectious folliculocentric process comprised of 3 distinct types. The histopathology shows follicular spongiosis with increased eosinophils. The pathogenesis is most likely related to a multifactorial immune system dysregulation involving TH2 T cells, prostaglandin D2, and eotaxin-3. The treatment of EPF may involve topical corticosteroids, UVB phototherapy, or most notably oral indomethacin. In patients with EPF and malignancy, EDHM is a differential diagnosis to consider. Our case serves as a reminder that rare eosinophilic dermatoses may represent manifestations of underlying hematopoietic malignancy and, when investigated early, can lead to appropriate life-saving treatment.

- Nervi J, Stephen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- Hernández-Martín Á, Nuño-González A, Colmenero I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy: a series of 15 cases and review of the literature [published online July 21, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:150-155.

- Soepr

ono F, Schinella R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1020-1022. - Katoh

M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. - Keida

T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplant. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. - Goiriz R, Gul-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36.

- Satoh T, Ikeda H, Yokozeki H. Acrosyringeal involvement of palmoplantar lesions of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:99.

- Tsuboi H, Wakita K, Fujimura T, et al. Acral variant of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:321-324.

- Nakahig

ashi K, Doi H, Otsuka A, et al. PGD2 induces eotaxin-3 via PPARgamma from sebocytes: a possible pathogenesis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:536-543. - Satoh

T, Shimura C, Miyagishi C, et al. Indomethacin-induced reduction in CRTH2 in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease): a proposed mechanism of action. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:18-22. - Hagiwara A, Fujimura T, Furudate S, et al. Induction of CD163(+)M2 macrophages in the lesional skin of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:104-106.

- Ellis

E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. - Bull R

H, Harland CA, Fallowfield ME, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: a self-limiting illness in patients being treated for haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:178-182. - Farber M, Forgia S, Sahu J, et al. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:690-695.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) was originally described in 1965 and has since evolved into 3 distinct subtypes: classic, immunosuppressed (IS), and infantile types. Immunosuppressed EPF can be further subdivided into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated (IS-HIV) and non-HIV associated. Human immunodeficiency virus–seronegative cases have been associated with underlying malignancies (IS-heme) or chronic immunosuppression, such as that seen in transplant patients.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with a medical history limited to prostate adenocarcinoma treated with a robotic prostatectomy presented with a pruritic red rash on the face, neck, shoulders, and chest of 1 month’s duration. The patient previously completed a course of azithromycin 250 mg, intramuscular triamcinolone, and oral prednisone with only minor improvement. Physical examination demonstrated multiple pink folliculocentric papules and pustules scattered on the head (Figure 1A), neck, and chest (Figure 1B), as well as edematous pink papules and plaques on the forehead (Figures 1C and 1D). The palms, soles, and oral mucosa were clear.

Initial biopsy of the right side of the chest was nonspecific and most consistent with a reaction to an arthropod bite. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. With no improvement seen, additional biopsies were obtained from the left side of the chest and forehead. The biopsy of the chest showed ruptured folliculitis with evidence of acute and chronic inflammation. The biopsy of the forehead demonstrated eosinophilic follicular spongiosis with intrafollicular Langerhans cell microgranulomas along with abundant eosinophils adjacent to follicles, consistent with EPF (Figure 2). Serum HIV testing was negative. Serum white blood cell count was normal at 6400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with mild elevation of eosinophils (8%). The remaining complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. The patient was subsequently started on oral indomethacin 25 mg twice daily and triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Within a few days he experienced initial improvement in his symptoms of pruritus and diminution in the number of inflammatory follicular papules.

Approximately 1 month after presentation, he began to experience symptoms of dysphagia and fatigue. In addition, tonsillar hypertrophy and palpable neck and axillary lymphadenopathy were present. Computed tomography of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed diffuse lymphadenopathy. Full-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography demonstrated extensive metabolically active lymphoma in multiple nodal groups above and below the diaphragm. There also was lymphomatous involvement of the spleen. An axillary lymph node biopsy was diagnostic for mantle cell lymphoma (CD4:CD8, 1:1; CD45 negative; CD20 positive; CD5 positive). He

Comment

Subtypes of EPF

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis was first described in a Japanese female presenting with folliculocentric pustules distributed on the face, torso, and arms.1 This noninfectious eosinophilic infiltration of hair follicles predominantly seen in the Japanese population is now regarded as the classic form. Three distinct subtypes of EPF now exist, including the originally described classic variant (Ofuji disease), an IS variant, and a rare infantile form.1

All 3 subtypes of EPF are more commonly seen in men than women. The classic form has a peak incidence between the third and fourth decades of life. It presents as chronic annular papules and sterile pustules exhibiting peripheral extension, with individual lesions lasting for approximately 7 to 10 days with frequent relapses. The face is the most common area of involvement, followed by the trunk, extremities, and more rarely the palmoplantar surfaces. Concomitant leukocytosis with eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients.1 The infantile type represents the rarest EPF form. The average age of onset is 5 months, with most cases resolving by 14 months of age.1

Clinically, EPF is characterized by recurrent papules and pustules predominantly on the scalp without annular or polycyclic ring formation, as seen in the classic type. The palms and soles may be involved, which can clinically mimic infantile acropustulosis and scabies infection. Most patients exhibit a concomitant peripheral eosinophilia.1,2

In the late 1980s, the IS variant of EPF was recognized in HIV-positive (IS-HIV) and HIV-negative malignancy-associated (IS-heme) populations.1,3 This newly characterized form differs morphologically and biologically from the classic and infantile subtypes. The IS subtype has a unique presentation including intensely pruritic, discrete, erythematous, follicular papules with palmoplantar sparing and infrequent annular or circinate plaque forms.1 Frequently, with the IS-HIV form, CD4+ T-cell counts are below 300 cells/mL, and 25% to 50% of patients have lymphopenia with eosinophilia.3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has been associated with EPF resolution in HIV-positive individuals; however, it also has been shown to induce transient EPF during the first 3 to 6 months of initiation.1,3,4

Unlike the IS-HIV form, the IS-heme form has occurred solely in males and is predominantly associated with hematologic malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome) 30 to 90 days following bone marrow transplant, peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or chemotherapy treatment.5,6 Unlike the chronic and persistent IS-HIV form, prior cases of IS-heme EPF have been predominantly self-limited. Interestingly, only 2 reported cases of EPF have occurred prior to the diagnosis of malignancy including B-cell leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.5

Histopathology

All 3 identified forms of EPF histopathologically show acute and chronic lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate concentrated at the follicular isthmus, which can lead to follicular destruction. Scattered mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are found within the pilar outer root sheath, sebaceous glands, and ducts. Approximately 40% of cases demonstrate follicular mucinosis.1 Histopathology of lesional palmar skin in classic-type EPF demonstrates intraepidermal pustule formation with abundant eosinophils and neutrophils adjacent to the acrosyringium.7,8

Pathogenesis

Although the pathophysiology of EPF is largely unknown, it is thought to represent a helper T cell (TH2) response involving IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines.9 Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2, which is expressed on eosinophils and lymphocytes, is believed to play a role in the pruritus, edema, and inflammatory response seen adjacent to pilosebaceous units in EPF.10 Moreover, immunohistochemical and flow cytometry analysis has revealed a prevalence of prostaglandin D2 within the perisebocyte infiltrate in EPF.9 Prostaglandin D2 induces eotaxin-3 production within sebocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which enhances chemoattraction of eosinophils. This pathogenesis represents a prostaglandin-based mechanism and potentially explains the efficacy of indomethacin treatment of EPF through its cyclooxygenase inhibition and reduction of chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2 expression.9-11

Treatment

Multiple therapeutic modalities have been reported for the treatment of EPF. For all 3 subtypes, moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy. UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly remains the gold standard, given its consistent efficacy.1,12 Indomethacin (50–75 mg daily) remains first-line treatment of classic EPF.4,12 Previously reported cases of classic EPF and IS-EPF have responded well to oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily).12,13 In a retrospective review of EPF treatment data, the following treatments also have been reported to be successful: psoralen plus UVA, oral cetirizine (20–40 mg daily, particularly for IS-EPF cases), metronidazole (250 mg 3 times daily), minocycline (150 mg daily), itraconazole (200–400 mg daily, dapsone (50–200 mg daily), systemic retinoids, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and permethrin cream.4,12

Malignancy