User login

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2023

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

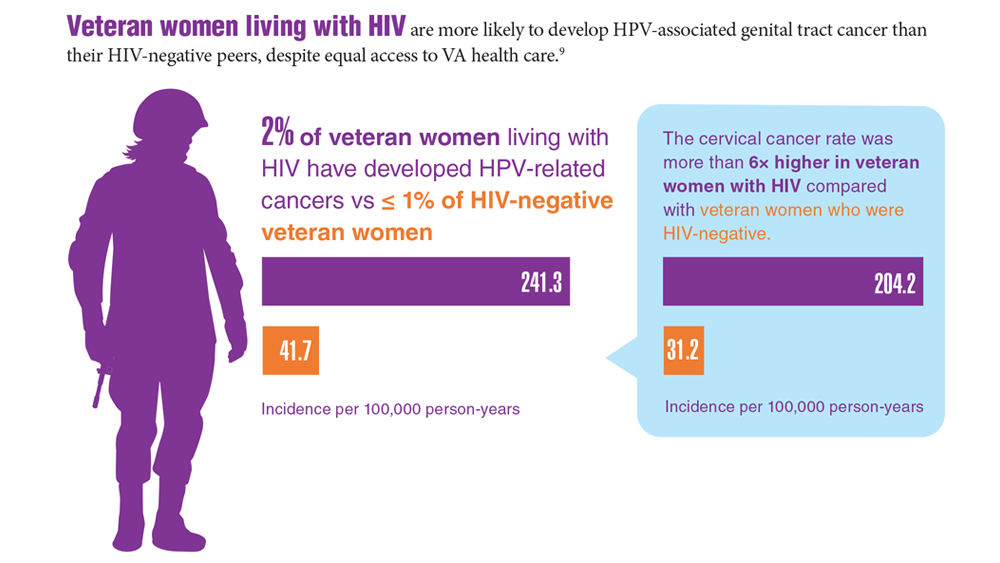

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Data Trends 2023: HPV and Related Cancers

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

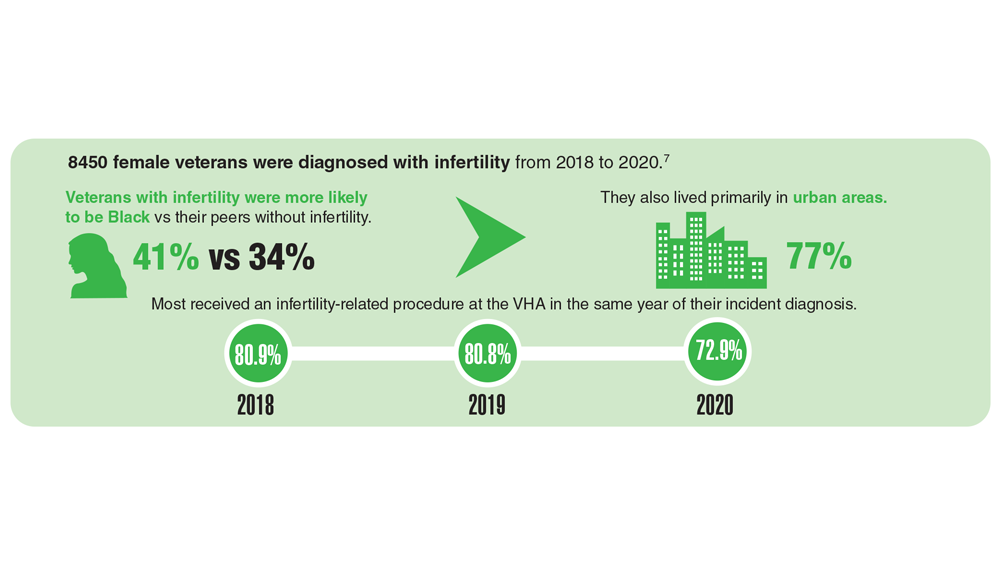

Data Trends 2023: Infertility

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1031-1.html

- Congressional Research Service Report. Infertility in the military. Updated May 26, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11504

- Mancuso AC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(5):744.e1-744.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.002

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infertility FAQs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/

- Kroll-Desrosiers A et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;1-7. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08080-z

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Infertility and IVF. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/topics/infertility-and-ivf.asp

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1031-1.html

- Congressional Research Service Report. Infertility in the military. Updated May 26, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11504

- Mancuso AC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(5):744.e1-744.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.002

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infertility FAQs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/

- Kroll-Desrosiers A et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;1-7. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08080-z

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Infertility and IVF. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/topics/infertility-and-ivf.asp

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1031-1.html

- Congressional Research Service Report. Infertility in the military. Updated May 26, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11504

- Mancuso AC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(5):744.e1-744.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.002

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infertility FAQs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/

- Kroll-Desrosiers A et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;1-7. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08080-z

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Infertility and IVF. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/topics/infertility-and-ivf.asp

Menstruation linked to underdiagnosis of type 2 diabetes?

The analysis estimates that an additional 17% of undiagnosed women younger than 50 years could be reclassified as having T2D, and that women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was markedly lower than that of men under 50, by a mean of 1.6 mmol/mol.

In a study that will be presented at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the researchers wanted to investigate whether a contributing factor to late diagnosis of T2D in women under 50 may be the difference in A1c levels due to hemoglobin replacement linked to menstrual blood loss.

The study was published online in Diabetes Therapy. “If the threshold for diagnosis of diabetes ... was lowered by 2 mmol/mol in women under the age of 50, an additional 17% of these women (approximately equivalent to 35,000 women in England and Wales) would be diagnosed with diabetes ... which may contribute to up to 64% of the difference in mortality rates between men/women with diabetes mellitus aged 16-50 years,” the researchers noted.

They added that A1c levels in women under 50 years were found to be consistently lower than those in men, and with A1c levels in women reaching the equivalent of those in men up to 10 years later, this “may result in delayed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in premenopausal women.”

Noting that the study was observational, senior author Adrian Heald, MD, consultant endocrinologist, Salford (England) Royal NHS Foundation Trust, said that it “may be the case that prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in women are not being spotted because the set point needs to be slightly lower, but a systematic study sampling from the population of at-risk individuals is needed further to our findings.

“We also need to refer back to use of the glucose tolerance test, because A1c has been used for the past 15 years but it is not the gold standard,” added Dr. Heald. “Clinicians have often wondered if patients might be missed with A1c measurement, or even overdiagnosed.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, from Diabetes UK, acknowledged that the research was valuable but added: “More research on sex differences in thresholds for a type 2 diagnosis is needed to inform any changes to clinical practice. In the meantime, we encourage clinicians to follow the current guidance of not ruling out type 2 diabetes based on a one-off A1c below the diagnostic threshold.”

But in support of greater understanding around the sex differences in A1c diagnostic thresholds, Dr. Chambers added: “Receiving an accurate and timely diagnosis ensures that women get the treatment and support needed to manage their type 2 diabetes and avoid long-term complications, including heart disease, where sex-based inequalities in care already contribute to poorer outcomes for women.”

Effect of A1c reference range on T2D diagnosis and associated CVD

Compared with men, women with T2D have poorer glycemic control; a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) complications; reduced life expectancy (5.3 years shorter vs. 4.5 years shorter); and a higher risk factor burden, such as obesity and hypertension at diagnosis.

In addition, T2D is a stronger risk factor for CV disease (CVD) in women than in men, and those aged 35-59 years who receive a diagnosis have the highest relative CV death risk across all age and sex groups.

The researchers pointed out that previous studies have observed differences in A1c relative to menopause, and they too found that “A1c levels rose after the age of 50 in women.”

However, they noted that the implication of differing A1c reference ranges on delayed diabetes diagnosis with worsening CV risk profile had not been previously recognized and that their study “[h]ighlights for the first time that, while 1.6 mmol/mol may appear only a small difference in terms of laboratory measurement, at population level this has implications for significant number of premenopausal women.”

The researchers initially observed the trend in local data in Salford, in the northwest of England. “These ... data highlighted that women seemed to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age, so we wanted to examine what the source of that might be,” study author Mike Stedman, BSc, director, Res Consortium, Andover, England, said in an interview.

Dr. Stedman and his colleagues assessed the sex and age differences of A1c in individuals who had not been diagnosed with diabetes (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [≤ 6.5%]). “We looked at data from other labs [in addition to those in Salford, totaling 938,678 people] to see if this was a local phenomenon. They could only provide more recent data, but these also showed a similar pattern,” he added.

Finally, Dr. Stedman, Dr. Heald, and their colleagues estimated the possible national impact by extrapolating findings based on population data from the UK Office of National Statistics and on National Diabetes Audit data for type 2 diabetes prevalence and related excess mortality. This brought them to the conclusion that T2D would be diagnosed in an additional 17% of women if the threshold were lowered by 2 mmol/mol, to 46 mmol/mol, in women under 50 years.

Lower A1c in women under 50 may delay T2D diagnosis by up to 10 years

The analysis found that the median A1c increased with age, with values in women younger than 50 years consistently being 1 mmol/mol lower than values in men. In contrast, A1c values in women over 50 years were equivalent to those in men.

However, at age 50 years, compared with men, A1c in women was found to lag by approximately 5 years. Women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was lower than that of men by an average of 1.6 mmol/mol (4.7% of mean; P < .0001), whereas this difference in individuals aged 50 years or older was less pronounced (P < .0001).

The authors wrote that “an undermeasurement of approximately 1.6 mmol/mol A1c in women may delay their diabetes ... diagnosis by up to 10 years.”

Further analysis showed that, at an A1c of 48 mmol/mol, 50% fewer women than men under the age of 50 could be diagnosed with T2D, whereas only 20% fewer women than men aged 50 years or older could be diagnosed with T2D.

Lowering the A1c threshold for diagnosis of T2D from 48 mmol/mol to 46 mmol/mol in women under 50 led to an estimate that an additional 35,345 undiagnosed women in England could be reclassified as having a T2D diagnosis.

The authors pointed out that “gender difference in adverse cardiovascular risk factors are known to be present prior to the development of [type 2] diabetes” and that “once diagnosed, atherosclerotic CVD prevalence is twice as high in patients with diabetes ... compared to those without a diagnosis.”

Dr. Heald added that there is always the possibility that other factors might be at play and that the work posed questions rather than presented answers.

Taking a pragmatic view, the researchers suggested that “one alternative approach may be to offer further assessment using fasting plasma glucose or oral glucose tolerance testing in those with A1c values of 46 or 47 mmol/mol.”

“In anyone with an early diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, in addition to dietary modification and especially if there is cardiovascular risk, then one might start them on metformin due to the cardiovascular benefits as well as the sugar-lowering effects,” said Dr. Heald, adding that “we certainly don’t want women missing out on metformin that could have huge benefits in the longer term.”

Dr. Stedman and Dr. Heald declared no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Dr. Chambers has declared no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The analysis estimates that an additional 17% of undiagnosed women younger than 50 years could be reclassified as having T2D, and that women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was markedly lower than that of men under 50, by a mean of 1.6 mmol/mol.

In a study that will be presented at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the researchers wanted to investigate whether a contributing factor to late diagnosis of T2D in women under 50 may be the difference in A1c levels due to hemoglobin replacement linked to menstrual blood loss.

The study was published online in Diabetes Therapy. “If the threshold for diagnosis of diabetes ... was lowered by 2 mmol/mol in women under the age of 50, an additional 17% of these women (approximately equivalent to 35,000 women in England and Wales) would be diagnosed with diabetes ... which may contribute to up to 64% of the difference in mortality rates between men/women with diabetes mellitus aged 16-50 years,” the researchers noted.

They added that A1c levels in women under 50 years were found to be consistently lower than those in men, and with A1c levels in women reaching the equivalent of those in men up to 10 years later, this “may result in delayed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in premenopausal women.”

Noting that the study was observational, senior author Adrian Heald, MD, consultant endocrinologist, Salford (England) Royal NHS Foundation Trust, said that it “may be the case that prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in women are not being spotted because the set point needs to be slightly lower, but a systematic study sampling from the population of at-risk individuals is needed further to our findings.

“We also need to refer back to use of the glucose tolerance test, because A1c has been used for the past 15 years but it is not the gold standard,” added Dr. Heald. “Clinicians have often wondered if patients might be missed with A1c measurement, or even overdiagnosed.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, from Diabetes UK, acknowledged that the research was valuable but added: “More research on sex differences in thresholds for a type 2 diagnosis is needed to inform any changes to clinical practice. In the meantime, we encourage clinicians to follow the current guidance of not ruling out type 2 diabetes based on a one-off A1c below the diagnostic threshold.”

But in support of greater understanding around the sex differences in A1c diagnostic thresholds, Dr. Chambers added: “Receiving an accurate and timely diagnosis ensures that women get the treatment and support needed to manage their type 2 diabetes and avoid long-term complications, including heart disease, where sex-based inequalities in care already contribute to poorer outcomes for women.”

Effect of A1c reference range on T2D diagnosis and associated CVD

Compared with men, women with T2D have poorer glycemic control; a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) complications; reduced life expectancy (5.3 years shorter vs. 4.5 years shorter); and a higher risk factor burden, such as obesity and hypertension at diagnosis.

In addition, T2D is a stronger risk factor for CV disease (CVD) in women than in men, and those aged 35-59 years who receive a diagnosis have the highest relative CV death risk across all age and sex groups.

The researchers pointed out that previous studies have observed differences in A1c relative to menopause, and they too found that “A1c levels rose after the age of 50 in women.”

However, they noted that the implication of differing A1c reference ranges on delayed diabetes diagnosis with worsening CV risk profile had not been previously recognized and that their study “[h]ighlights for the first time that, while 1.6 mmol/mol may appear only a small difference in terms of laboratory measurement, at population level this has implications for significant number of premenopausal women.”

The researchers initially observed the trend in local data in Salford, in the northwest of England. “These ... data highlighted that women seemed to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age, so we wanted to examine what the source of that might be,” study author Mike Stedman, BSc, director, Res Consortium, Andover, England, said in an interview.

Dr. Stedman and his colleagues assessed the sex and age differences of A1c in individuals who had not been diagnosed with diabetes (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [≤ 6.5%]). “We looked at data from other labs [in addition to those in Salford, totaling 938,678 people] to see if this was a local phenomenon. They could only provide more recent data, but these also showed a similar pattern,” he added.

Finally, Dr. Stedman, Dr. Heald, and their colleagues estimated the possible national impact by extrapolating findings based on population data from the UK Office of National Statistics and on National Diabetes Audit data for type 2 diabetes prevalence and related excess mortality. This brought them to the conclusion that T2D would be diagnosed in an additional 17% of women if the threshold were lowered by 2 mmol/mol, to 46 mmol/mol, in women under 50 years.

Lower A1c in women under 50 may delay T2D diagnosis by up to 10 years

The analysis found that the median A1c increased with age, with values in women younger than 50 years consistently being 1 mmol/mol lower than values in men. In contrast, A1c values in women over 50 years were equivalent to those in men.

However, at age 50 years, compared with men, A1c in women was found to lag by approximately 5 years. Women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was lower than that of men by an average of 1.6 mmol/mol (4.7% of mean; P < .0001), whereas this difference in individuals aged 50 years or older was less pronounced (P < .0001).

The authors wrote that “an undermeasurement of approximately 1.6 mmol/mol A1c in women may delay their diabetes ... diagnosis by up to 10 years.”

Further analysis showed that, at an A1c of 48 mmol/mol, 50% fewer women than men under the age of 50 could be diagnosed with T2D, whereas only 20% fewer women than men aged 50 years or older could be diagnosed with T2D.

Lowering the A1c threshold for diagnosis of T2D from 48 mmol/mol to 46 mmol/mol in women under 50 led to an estimate that an additional 35,345 undiagnosed women in England could be reclassified as having a T2D diagnosis.

The authors pointed out that “gender difference in adverse cardiovascular risk factors are known to be present prior to the development of [type 2] diabetes” and that “once diagnosed, atherosclerotic CVD prevalence is twice as high in patients with diabetes ... compared to those without a diagnosis.”

Dr. Heald added that there is always the possibility that other factors might be at play and that the work posed questions rather than presented answers.

Taking a pragmatic view, the researchers suggested that “one alternative approach may be to offer further assessment using fasting plasma glucose or oral glucose tolerance testing in those with A1c values of 46 or 47 mmol/mol.”

“In anyone with an early diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, in addition to dietary modification and especially if there is cardiovascular risk, then one might start them on metformin due to the cardiovascular benefits as well as the sugar-lowering effects,” said Dr. Heald, adding that “we certainly don’t want women missing out on metformin that could have huge benefits in the longer term.”

Dr. Stedman and Dr. Heald declared no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Dr. Chambers has declared no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The analysis estimates that an additional 17% of undiagnosed women younger than 50 years could be reclassified as having T2D, and that women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was markedly lower than that of men under 50, by a mean of 1.6 mmol/mol.

In a study that will be presented at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the researchers wanted to investigate whether a contributing factor to late diagnosis of T2D in women under 50 may be the difference in A1c levels due to hemoglobin replacement linked to menstrual blood loss.

The study was published online in Diabetes Therapy. “If the threshold for diagnosis of diabetes ... was lowered by 2 mmol/mol in women under the age of 50, an additional 17% of these women (approximately equivalent to 35,000 women in England and Wales) would be diagnosed with diabetes ... which may contribute to up to 64% of the difference in mortality rates between men/women with diabetes mellitus aged 16-50 years,” the researchers noted.

They added that A1c levels in women under 50 years were found to be consistently lower than those in men, and with A1c levels in women reaching the equivalent of those in men up to 10 years later, this “may result in delayed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in premenopausal women.”

Noting that the study was observational, senior author Adrian Heald, MD, consultant endocrinologist, Salford (England) Royal NHS Foundation Trust, said that it “may be the case that prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in women are not being spotted because the set point needs to be slightly lower, but a systematic study sampling from the population of at-risk individuals is needed further to our findings.

“We also need to refer back to use of the glucose tolerance test, because A1c has been used for the past 15 years but it is not the gold standard,” added Dr. Heald. “Clinicians have often wondered if patients might be missed with A1c measurement, or even overdiagnosed.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, from Diabetes UK, acknowledged that the research was valuable but added: “More research on sex differences in thresholds for a type 2 diagnosis is needed to inform any changes to clinical practice. In the meantime, we encourage clinicians to follow the current guidance of not ruling out type 2 diabetes based on a one-off A1c below the diagnostic threshold.”

But in support of greater understanding around the sex differences in A1c diagnostic thresholds, Dr. Chambers added: “Receiving an accurate and timely diagnosis ensures that women get the treatment and support needed to manage their type 2 diabetes and avoid long-term complications, including heart disease, where sex-based inequalities in care already contribute to poorer outcomes for women.”

Effect of A1c reference range on T2D diagnosis and associated CVD

Compared with men, women with T2D have poorer glycemic control; a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) complications; reduced life expectancy (5.3 years shorter vs. 4.5 years shorter); and a higher risk factor burden, such as obesity and hypertension at diagnosis.

In addition, T2D is a stronger risk factor for CV disease (CVD) in women than in men, and those aged 35-59 years who receive a diagnosis have the highest relative CV death risk across all age and sex groups.

The researchers pointed out that previous studies have observed differences in A1c relative to menopause, and they too found that “A1c levels rose after the age of 50 in women.”

However, they noted that the implication of differing A1c reference ranges on delayed diabetes diagnosis with worsening CV risk profile had not been previously recognized and that their study “[h]ighlights for the first time that, while 1.6 mmol/mol may appear only a small difference in terms of laboratory measurement, at population level this has implications for significant number of premenopausal women.”

The researchers initially observed the trend in local data in Salford, in the northwest of England. “These ... data highlighted that women seemed to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age, so we wanted to examine what the source of that might be,” study author Mike Stedman, BSc, director, Res Consortium, Andover, England, said in an interview.

Dr. Stedman and his colleagues assessed the sex and age differences of A1c in individuals who had not been diagnosed with diabetes (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [≤ 6.5%]). “We looked at data from other labs [in addition to those in Salford, totaling 938,678 people] to see if this was a local phenomenon. They could only provide more recent data, but these also showed a similar pattern,” he added.

Finally, Dr. Stedman, Dr. Heald, and their colleagues estimated the possible national impact by extrapolating findings based on population data from the UK Office of National Statistics and on National Diabetes Audit data for type 2 diabetes prevalence and related excess mortality. This brought them to the conclusion that T2D would be diagnosed in an additional 17% of women if the threshold were lowered by 2 mmol/mol, to 46 mmol/mol, in women under 50 years.

Lower A1c in women under 50 may delay T2D diagnosis by up to 10 years

The analysis found that the median A1c increased with age, with values in women younger than 50 years consistently being 1 mmol/mol lower than values in men. In contrast, A1c values in women over 50 years were equivalent to those in men.

However, at age 50 years, compared with men, A1c in women was found to lag by approximately 5 years. Women under 50 had an A1c distribution that was lower than that of men by an average of 1.6 mmol/mol (4.7% of mean; P < .0001), whereas this difference in individuals aged 50 years or older was less pronounced (P < .0001).

The authors wrote that “an undermeasurement of approximately 1.6 mmol/mol A1c in women may delay their diabetes ... diagnosis by up to 10 years.”

Further analysis showed that, at an A1c of 48 mmol/mol, 50% fewer women than men under the age of 50 could be diagnosed with T2D, whereas only 20% fewer women than men aged 50 years or older could be diagnosed with T2D.

Lowering the A1c threshold for diagnosis of T2D from 48 mmol/mol to 46 mmol/mol in women under 50 led to an estimate that an additional 35,345 undiagnosed women in England could be reclassified as having a T2D diagnosis.

The authors pointed out that “gender difference in adverse cardiovascular risk factors are known to be present prior to the development of [type 2] diabetes” and that “once diagnosed, atherosclerotic CVD prevalence is twice as high in patients with diabetes ... compared to those without a diagnosis.”

Dr. Heald added that there is always the possibility that other factors might be at play and that the work posed questions rather than presented answers.

Taking a pragmatic view, the researchers suggested that “one alternative approach may be to offer further assessment using fasting plasma glucose or oral glucose tolerance testing in those with A1c values of 46 or 47 mmol/mol.”

“In anyone with an early diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, in addition to dietary modification and especially if there is cardiovascular risk, then one might start them on metformin due to the cardiovascular benefits as well as the sugar-lowering effects,” said Dr. Heald, adding that “we certainly don’t want women missing out on metformin that could have huge benefits in the longer term.”

Dr. Stedman and Dr. Heald declared no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Dr. Chambers has declared no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2023

Hyaluronic acid suppository improves menopause symptoms

TOPLINE:

Among women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause, 12 weeks of treatment with vaginal suppositories containing hyaluronic acid (HLA) reduces vulvovaginal symptoms, according to trial results presented at the annual Menopause Meeting. HLA may be a promising nonhormonal therapy for this condition, the researchers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators randomly assigned 49 women to receive treatment with a vaginal suppository containing 5 mg of HLA or standard-of-care treatment with vaginal estrogen cream (0.01%).

- The trial was conducted between September 2021 and August 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients in both treatment arms experienced improvements on the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), the study’s primary outcome.

- The VSQ assesses vulvovaginal symptoms associated with menopause such as itching, burning, and dryness, as well as the emotional toll of symptoms and their effect on sexual activity.

- Change in VSQ score did not significantly differ between the treatment groups. The measure improved from 5.2 to 1.7 in the group that received estrogen, and from 5.8 to 2.5 in those who received HLA (P = .81).

- No treatment-related severe adverse events were reported.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women often need to decide between different therapies for genitourinary syndrome of menopause,” study author Benjamin Brucker, MD, of New York University said in an interview. “Now we can help counsel them about this formulation of HLA.”

SOURCE:

Poster P-1 was presented at the 2023 meeting of the Menopause Society, held Sept. 27-30 in Philadelphia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Bonafide Health, a company that sells supplements to treat menopause symptoms, including vaginal suppositories containing HLA.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause, 12 weeks of treatment with vaginal suppositories containing hyaluronic acid (HLA) reduces vulvovaginal symptoms, according to trial results presented at the annual Menopause Meeting. HLA may be a promising nonhormonal therapy for this condition, the researchers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators randomly assigned 49 women to receive treatment with a vaginal suppository containing 5 mg of HLA or standard-of-care treatment with vaginal estrogen cream (0.01%).

- The trial was conducted between September 2021 and August 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients in both treatment arms experienced improvements on the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), the study’s primary outcome.

- The VSQ assesses vulvovaginal symptoms associated with menopause such as itching, burning, and dryness, as well as the emotional toll of symptoms and their effect on sexual activity.

- Change in VSQ score did not significantly differ between the treatment groups. The measure improved from 5.2 to 1.7 in the group that received estrogen, and from 5.8 to 2.5 in those who received HLA (P = .81).

- No treatment-related severe adverse events were reported.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women often need to decide between different therapies for genitourinary syndrome of menopause,” study author Benjamin Brucker, MD, of New York University said in an interview. “Now we can help counsel them about this formulation of HLA.”

SOURCE:

Poster P-1 was presented at the 2023 meeting of the Menopause Society, held Sept. 27-30 in Philadelphia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Bonafide Health, a company that sells supplements to treat menopause symptoms, including vaginal suppositories containing HLA.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause, 12 weeks of treatment with vaginal suppositories containing hyaluronic acid (HLA) reduces vulvovaginal symptoms, according to trial results presented at the annual Menopause Meeting. HLA may be a promising nonhormonal therapy for this condition, the researchers said.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators randomly assigned 49 women to receive treatment with a vaginal suppository containing 5 mg of HLA or standard-of-care treatment with vaginal estrogen cream (0.01%).

- The trial was conducted between September 2021 and August 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients in both treatment arms experienced improvements on the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), the study’s primary outcome.

- The VSQ assesses vulvovaginal symptoms associated with menopause such as itching, burning, and dryness, as well as the emotional toll of symptoms and their effect on sexual activity.

- Change in VSQ score did not significantly differ between the treatment groups. The measure improved from 5.2 to 1.7 in the group that received estrogen, and from 5.8 to 2.5 in those who received HLA (P = .81).

- No treatment-related severe adverse events were reported.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women often need to decide between different therapies for genitourinary syndrome of menopause,” study author Benjamin Brucker, MD, of New York University said in an interview. “Now we can help counsel them about this formulation of HLA.”

SOURCE:

Poster P-1 was presented at the 2023 meeting of the Menopause Society, held Sept. 27-30 in Philadelphia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Bonafide Health, a company that sells supplements to treat menopause symptoms, including vaginal suppositories containing HLA.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Menopausal hormone therapy less prescribed for Black women

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a review of published studies presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly The North American Menopause Society).

“Gaps in treatment can be used to inform health care providers about menopausal HT prescribing disparities, with the goal of improving equitable and advanced patient care among disadvantaged populations,” wrote Danette Conklin, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a psychologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Sally MacPhedran, MD, an associate professor of reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and an ob.gyn at MetroHealth Medical Center, also in Cleveland; and their colleagues.

The researchers combed through PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and PsychInfo databases to identify all studies conducted in the United States since 1940 that contained data on patient demographics and prescribing patterns for hormone therapy to treat menopausal symptoms. In addition to excluding men, children, teens, trans men, and women who had contraindications for HT, the investigators excluded randomized clinical trials so that prescribing patterns would not be based on protocols or RCT participatory criteria.

The researchers identified 20 studies, ranging from 1973 through 2015, including 9 national studies and the others across different U.S. regions. They then analyzed differences in HT prescribing according to age, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance type, body mass index, and mental health, including alcohol or substance use.

Seven of the studies assessed HT use based on patient surveys, seven used medical or medication records showing an HT prescription, two studies used insurance claims to show an HT prescription, and one study surveyed patients about whether they received an HT prescription. Another four studies used surveys that asked patients whether they received HT counseling but did not indicate if the patients received a prescription.

Half of the studies showed racial disparities in HT prescribing. In all of them, Black women used or were prescribed or counseled on using HT less than white, Hispanic, or Asian women. White women had greater use, prescribing, or counseling than all other races/ethnicities except one study in which Hispanic women were prescribed vaginal estrogen more often than white women.

Six of the studies showed education disparities in which menopausal women with lower education levels used less HT or were prescribed or counseled on HT less than women with higher education.

Complex reasons

Monica Christmas, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago and director of the Menopause Program and the Center for Women’s Integrated Health, said the study’s findings were not surprising, but the reasons for the racial disparities are likely complex.

Implicit bias in providers is likely one contributing factor, with some providers not thinking of offering HT to certain patients or not expecting the patients to be interested in it. Providers may also hesitate to prescribe HT to patients with more comorbidities because of concerns about HT risks, so if Black patients have more comorbidities, that could play a role in how many are offered or counseled on HT, she said.

“Probably the biggest take home is that it is important to be asking all of our patients about their symptoms and being proactive about talking about it,” Dr. Christmas said in an interview.

At the same time, in her anecdotal experience at a previous institution, Dr. Christmas noticed that her Black patients were less receptive to using hormone therapy than her White patients even though her Black patients tended to exhibit or report greater or more severe symptoms. But there’s been a “paradigm shift” more recently, Dr. Christmas said. With awareness about menopause growing in the media and particularly on social media, and with greater awareness about racial disparities in menopausal symptoms and care – including that shown in Dr. Christmas’s work in the SWAN Study – Dr. Christmas has had more Black patients asking about HT and other treatments for their menopausal symptoms more recently.

“Just 10 years ago, I was trying to talk to people about hormones, and I’ve been giving them to people that need them for a long time, and I couldn’t,” Dr. Christmas said. “Now people are coming in, saying ‘no one’s ever talked to me about it’ or ‘I deserve this.’ It shows you the persuasion that social media and the Internet have on our thinking too, and I think that’s going to be interesting to look at, to see how that impacts people’s perception about wanting treatment.”

Dr. Conklin agreed that reasons for the disparities likely involve a combination of factors, including providers’ assumptions about different racial groups’ knowledge and receptiveness toward different treatments. One of the studies in their review also reported provider barriers to prescribing HT, which included lack of time, lack of adequate knowledge, and concern about risks to patients’ health.

“Medical providers tend to have less time with their patients compared to PhDs, and that time factor really makes a big difference in terms of what the focus is going to be in that [short] appointment,” Dr. Conklin said in an interview. “Perhaps from a provider point of view, they are prioritizing what they think is more important to their patient and not really listening deeply to what their patient is saying.”

Educating clinicians

Potentially supporting that possibility, Dr. Conklin and Dr. MacPhedran also had a poster at the conference that looked at prescribing of HT in both Black and White women with a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

“In a population with a high percentage of Black patients known to have more menopause symptoms, the data demonstrated a surprisingly low rate of documented menopause symptoms (11%) compared to prior reports of up to 80%,” the researchers reported. “This low rate may be related to patient reporting, physician inquiry, or physician documentation of menopause symptoms.” They further found that White women with menopause symptoms and one of those psychiatric diagnosis were 40% more likely to receive an HT prescription for menopausal symptoms than Black women with the same diagnoses and symptoms.

Dr. Conklin emphasized the importance of providers not overlooking women who have mental health disorders when it comes to treating menopausal symptoms, particularly since mental health conditions and menopausal symptoms can exacerbate each other.

“Their depression could worsen irritability, and anxiety can worsen during the transition, and it could be overlooked or thought of as another [psychiatric] episode,” Dr. Conklin said. Providers may need to “dig a little deeper,” especially if patients are reporting having hot flashes or brain fog.

A key way to help overcome the racial disparities – whether they result from systemic issues, implicit bias or assumptions, or patients’ own reticence – is education, Dr. Conklin said. She recommended that providers have educational material about menopause and treatments for menopausal symptoms in the waiting room and then ask patients about their symptoms and invite patients to ask questions.

Dr. MacPhedran added that education for clinicians is key as well.

“Now is a great time – menopause is hot, menopause is interesting, and it’s getting a little bit of a push in terms of research dollars,” Dr. MacPhedran said. “That will trickle down to more emphasis in medical education, whether that’s nurse practitioners, physicians, PAs, or midwives. Everybody needs more education on menopause so they can be more comfortable asking and answering these questions.”

Dr. Conklin said she would like to see expanded education on menopause for medical residents and in health psychology curricula as well.

Among the 13 studies that found disparities in prescribing patterns by age, seven studies showed that older women used or were prescribed or counseled on HT more often than younger women. Four studies found the opposite, with older women less likely to use or be prescribed or counseled about HT. One study had mixed results, and one study had expected prescribing patterns.

Five studies found income disparities and five studies found disparities by medical conditions in terms of HT use, prescribing, or counseling. Other disparities identified in smaller numbers of studies (four or fewer) included natural versus surgical menopause, insurance coverage, body mass index, geographic region, smoking and alcohol use.

The two biggest limitations of the research were its heterogeneity and the small number of studies included, which points to how scarce research on racial disparities in HT use really are, Dr. Conklin said.

The research did not use any external funding. The authors had no industry disclosures. Dr. Christmas has done an educational video for FertilityIQ.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a review of published studies presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly The North American Menopause Society).

“Gaps in treatment can be used to inform health care providers about menopausal HT prescribing disparities, with the goal of improving equitable and advanced patient care among disadvantaged populations,” wrote Danette Conklin, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a psychologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Sally MacPhedran, MD, an associate professor of reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and an ob.gyn at MetroHealth Medical Center, also in Cleveland; and their colleagues.

The researchers combed through PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and PsychInfo databases to identify all studies conducted in the United States since 1940 that contained data on patient demographics and prescribing patterns for hormone therapy to treat menopausal symptoms. In addition to excluding men, children, teens, trans men, and women who had contraindications for HT, the investigators excluded randomized clinical trials so that prescribing patterns would not be based on protocols or RCT participatory criteria.

The researchers identified 20 studies, ranging from 1973 through 2015, including 9 national studies and the others across different U.S. regions. They then analyzed differences in HT prescribing according to age, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance type, body mass index, and mental health, including alcohol or substance use.

Seven of the studies assessed HT use based on patient surveys, seven used medical or medication records showing an HT prescription, two studies used insurance claims to show an HT prescription, and one study surveyed patients about whether they received an HT prescription. Another four studies used surveys that asked patients whether they received HT counseling but did not indicate if the patients received a prescription.

Half of the studies showed racial disparities in HT prescribing. In all of them, Black women used or were prescribed or counseled on using HT less than white, Hispanic, or Asian women. White women had greater use, prescribing, or counseling than all other races/ethnicities except one study in which Hispanic women were prescribed vaginal estrogen more often than white women.

Six of the studies showed education disparities in which menopausal women with lower education levels used less HT or were prescribed or counseled on HT less than women with higher education.

Complex reasons

Monica Christmas, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago and director of the Menopause Program and the Center for Women’s Integrated Health, said the study’s findings were not surprising, but the reasons for the racial disparities are likely complex.

Implicit bias in providers is likely one contributing factor, with some providers not thinking of offering HT to certain patients or not expecting the patients to be interested in it. Providers may also hesitate to prescribe HT to patients with more comorbidities because of concerns about HT risks, so if Black patients have more comorbidities, that could play a role in how many are offered or counseled on HT, she said.

“Probably the biggest take home is that it is important to be asking all of our patients about their symptoms and being proactive about talking about it,” Dr. Christmas said in an interview.

At the same time, in her anecdotal experience at a previous institution, Dr. Christmas noticed that her Black patients were less receptive to using hormone therapy than her White patients even though her Black patients tended to exhibit or report greater or more severe symptoms. But there’s been a “paradigm shift” more recently, Dr. Christmas said. With awareness about menopause growing in the media and particularly on social media, and with greater awareness about racial disparities in menopausal symptoms and care – including that shown in Dr. Christmas’s work in the SWAN Study – Dr. Christmas has had more Black patients asking about HT and other treatments for their menopausal symptoms more recently.

“Just 10 years ago, I was trying to talk to people about hormones, and I’ve been giving them to people that need them for a long time, and I couldn’t,” Dr. Christmas said. “Now people are coming in, saying ‘no one’s ever talked to me about it’ or ‘I deserve this.’ It shows you the persuasion that social media and the Internet have on our thinking too, and I think that’s going to be interesting to look at, to see how that impacts people’s perception about wanting treatment.”

Dr. Conklin agreed that reasons for the disparities likely involve a combination of factors, including providers’ assumptions about different racial groups’ knowledge and receptiveness toward different treatments. One of the studies in their review also reported provider barriers to prescribing HT, which included lack of time, lack of adequate knowledge, and concern about risks to patients’ health.

“Medical providers tend to have less time with their patients compared to PhDs, and that time factor really makes a big difference in terms of what the focus is going to be in that [short] appointment,” Dr. Conklin said in an interview. “Perhaps from a provider point of view, they are prioritizing what they think is more important to their patient and not really listening deeply to what their patient is saying.”

Educating clinicians

Potentially supporting that possibility, Dr. Conklin and Dr. MacPhedran also had a poster at the conference that looked at prescribing of HT in both Black and White women with a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

“In a population with a high percentage of Black patients known to have more menopause symptoms, the data demonstrated a surprisingly low rate of documented menopause symptoms (11%) compared to prior reports of up to 80%,” the researchers reported. “This low rate may be related to patient reporting, physician inquiry, or physician documentation of menopause symptoms.” They further found that White women with menopause symptoms and one of those psychiatric diagnosis were 40% more likely to receive an HT prescription for menopausal symptoms than Black women with the same diagnoses and symptoms.

Dr. Conklin emphasized the importance of providers not overlooking women who have mental health disorders when it comes to treating menopausal symptoms, particularly since mental health conditions and menopausal symptoms can exacerbate each other.

“Their depression could worsen irritability, and anxiety can worsen during the transition, and it could be overlooked or thought of as another [psychiatric] episode,” Dr. Conklin said. Providers may need to “dig a little deeper,” especially if patients are reporting having hot flashes or brain fog.

A key way to help overcome the racial disparities – whether they result from systemic issues, implicit bias or assumptions, or patients’ own reticence – is education, Dr. Conklin said. She recommended that providers have educational material about menopause and treatments for menopausal symptoms in the waiting room and then ask patients about their symptoms and invite patients to ask questions.

Dr. MacPhedran added that education for clinicians is key as well.

“Now is a great time – menopause is hot, menopause is interesting, and it’s getting a little bit of a push in terms of research dollars,” Dr. MacPhedran said. “That will trickle down to more emphasis in medical education, whether that’s nurse practitioners, physicians, PAs, or midwives. Everybody needs more education on menopause so they can be more comfortable asking and answering these questions.”

Dr. Conklin said she would like to see expanded education on menopause for medical residents and in health psychology curricula as well.

Among the 13 studies that found disparities in prescribing patterns by age, seven studies showed that older women used or were prescribed or counseled on HT more often than younger women. Four studies found the opposite, with older women less likely to use or be prescribed or counseled about HT. One study had mixed results, and one study had expected prescribing patterns.

Five studies found income disparities and five studies found disparities by medical conditions in terms of HT use, prescribing, or counseling. Other disparities identified in smaller numbers of studies (four or fewer) included natural versus surgical menopause, insurance coverage, body mass index, geographic region, smoking and alcohol use.

The two biggest limitations of the research were its heterogeneity and the small number of studies included, which points to how scarce research on racial disparities in HT use really are, Dr. Conklin said.

The research did not use any external funding. The authors had no industry disclosures. Dr. Christmas has done an educational video for FertilityIQ.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a review of published studies presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly The North American Menopause Society).

“Gaps in treatment can be used to inform health care providers about menopausal HT prescribing disparities, with the goal of improving equitable and advanced patient care among disadvantaged populations,” wrote Danette Conklin, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a psychologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center; Sally MacPhedran, MD, an associate professor of reproductive biology at Case Western Reserve University and an ob.gyn at MetroHealth Medical Center, also in Cleveland; and their colleagues.

The researchers combed through PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and PsychInfo databases to identify all studies conducted in the United States since 1940 that contained data on patient demographics and prescribing patterns for hormone therapy to treat menopausal symptoms. In addition to excluding men, children, teens, trans men, and women who had contraindications for HT, the investigators excluded randomized clinical trials so that prescribing patterns would not be based on protocols or RCT participatory criteria.

The researchers identified 20 studies, ranging from 1973 through 2015, including 9 national studies and the others across different U.S. regions. They then analyzed differences in HT prescribing according to age, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance type, body mass index, and mental health, including alcohol or substance use.

Seven of the studies assessed HT use based on patient surveys, seven used medical or medication records showing an HT prescription, two studies used insurance claims to show an HT prescription, and one study surveyed patients about whether they received an HT prescription. Another four studies used surveys that asked patients whether they received HT counseling but did not indicate if the patients received a prescription.

Half of the studies showed racial disparities in HT prescribing. In all of them, Black women used or were prescribed or counseled on using HT less than white, Hispanic, or Asian women. White women had greater use, prescribing, or counseling than all other races/ethnicities except one study in which Hispanic women were prescribed vaginal estrogen more often than white women.

Six of the studies showed education disparities in which menopausal women with lower education levels used less HT or were prescribed or counseled on HT less than women with higher education.

Complex reasons

Monica Christmas, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago and director of the Menopause Program and the Center for Women’s Integrated Health, said the study’s findings were not surprising, but the reasons for the racial disparities are likely complex.

Implicit bias in providers is likely one contributing factor, with some providers not thinking of offering HT to certain patients or not expecting the patients to be interested in it. Providers may also hesitate to prescribe HT to patients with more comorbidities because of concerns about HT risks, so if Black patients have more comorbidities, that could play a role in how many are offered or counseled on HT, she said.

“Probably the biggest take home is that it is important to be asking all of our patients about their symptoms and being proactive about talking about it,” Dr. Christmas said in an interview.

At the same time, in her anecdotal experience at a previous institution, Dr. Christmas noticed that her Black patients were less receptive to using hormone therapy than her White patients even though her Black patients tended to exhibit or report greater or more severe symptoms. But there’s been a “paradigm shift” more recently, Dr. Christmas said. With awareness about menopause growing in the media and particularly on social media, and with greater awareness about racial disparities in menopausal symptoms and care – including that shown in Dr. Christmas’s work in the SWAN Study – Dr. Christmas has had more Black patients asking about HT and other treatments for their menopausal symptoms more recently.

“Just 10 years ago, I was trying to talk to people about hormones, and I’ve been giving them to people that need them for a long time, and I couldn’t,” Dr. Christmas said. “Now people are coming in, saying ‘no one’s ever talked to me about it’ or ‘I deserve this.’ It shows you the persuasion that social media and the Internet have on our thinking too, and I think that’s going to be interesting to look at, to see how that impacts people’s perception about wanting treatment.”

Dr. Conklin agreed that reasons for the disparities likely involve a combination of factors, including providers’ assumptions about different racial groups’ knowledge and receptiveness toward different treatments. One of the studies in their review also reported provider barriers to prescribing HT, which included lack of time, lack of adequate knowledge, and concern about risks to patients’ health.

“Medical providers tend to have less time with their patients compared to PhDs, and that time factor really makes a big difference in terms of what the focus is going to be in that [short] appointment,” Dr. Conklin said in an interview. “Perhaps from a provider point of view, they are prioritizing what they think is more important to their patient and not really listening deeply to what their patient is saying.”

Educating clinicians

Potentially supporting that possibility, Dr. Conklin and Dr. MacPhedran also had a poster at the conference that looked at prescribing of HT in both Black and White women with a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

“In a population with a high percentage of Black patients known to have more menopause symptoms, the data demonstrated a surprisingly low rate of documented menopause symptoms (11%) compared to prior reports of up to 80%,” the researchers reported. “This low rate may be related to patient reporting, physician inquiry, or physician documentation of menopause symptoms.” They further found that White women with menopause symptoms and one of those psychiatric diagnosis were 40% more likely to receive an HT prescription for menopausal symptoms than Black women with the same diagnoses and symptoms.

Dr. Conklin emphasized the importance of providers not overlooking women who have mental health disorders when it comes to treating menopausal symptoms, particularly since mental health conditions and menopausal symptoms can exacerbate each other.

“Their depression could worsen irritability, and anxiety can worsen during the transition, and it could be overlooked or thought of as another [psychiatric] episode,” Dr. Conklin said. Providers may need to “dig a little deeper,” especially if patients are reporting having hot flashes or brain fog.

A key way to help overcome the racial disparities – whether they result from systemic issues, implicit bias or assumptions, or patients’ own reticence – is education, Dr. Conklin said. She recommended that providers have educational material about menopause and treatments for menopausal symptoms in the waiting room and then ask patients about their symptoms and invite patients to ask questions.

Dr. MacPhedran added that education for clinicians is key as well.

“Now is a great time – menopause is hot, menopause is interesting, and it’s getting a little bit of a push in terms of research dollars,” Dr. MacPhedran said. “That will trickle down to more emphasis in medical education, whether that’s nurse practitioners, physicians, PAs, or midwives. Everybody needs more education on menopause so they can be more comfortable asking and answering these questions.”

Dr. Conklin said she would like to see expanded education on menopause for medical residents and in health psychology curricula as well.

Among the 13 studies that found disparities in prescribing patterns by age, seven studies showed that older women used or were prescribed or counseled on HT more often than younger women. Four studies found the opposite, with older women less likely to use or be prescribed or counseled about HT. One study had mixed results, and one study had expected prescribing patterns.

Five studies found income disparities and five studies found disparities by medical conditions in terms of HT use, prescribing, or counseling. Other disparities identified in smaller numbers of studies (four or fewer) included natural versus surgical menopause, insurance coverage, body mass index, geographic region, smoking and alcohol use.

The two biggest limitations of the research were its heterogeneity and the small number of studies included, which points to how scarce research on racial disparities in HT use really are, Dr. Conklin said.

The research did not use any external funding. The authors had no industry disclosures. Dr. Christmas has done an educational video for FertilityIQ.

AT NAMS 2023

This symptom signals UTI in 83% of cases

TOPLINE:

Dyspareunia is a major indicator of urinary tract infections, being present in 83% of cases.

METHODOLOGY:

- Dyspareunia is a common symptom of UTIs, especially in premenopausal women, but is rarely inquired about during patient evaluations, according to researchers from Florida Atlantic University.

- In 2010, the researchers found that among 3,000 of their female Latinx patients aged 17-72 years in South Florida, 80% of those with UTIs reported experiencing pain during sexual intercourse.

- Since then, they have studied an additional 2,500 patients from the same population.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among all 5,500 patients, 83% of those who had UTIs experienced dyspareunia.

- Eighty percent of women of reproductive age with dyspareunia had an undiagnosed UTI.

- During the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years, dyspareunia was more often associated with genitourinary syndrome than UTIs.

- Ninety-four percent of women with UTI-associated dyspareunia responded positively to antibiotics.

IN PRACTICE:

“We have found that this symptom is extremely important as part of the symptomatology of UTI [and is] frequently found along with the classical symptoms,” the researchers reported. “Why has something so clear, so frequently present, never been described? The answer is simple: Physicians and patients do not talk about sex, despite dyspareunia being more a clinical symptom than a sexual one. Medical schools and residency programs in all areas, especially in obstetrics and gynecology, urology, and psychiatry, have been neglecting the education of physicians-in-training in this important aspect of human health. In conclusion, this is [proof] of how medicine has sometimes been influenced by religion, culture, and social norms far away from science.”

SOURCE:

The data were presented at the 2023 meeting of the Menopause Society. The study was led by Alberto Dominguez-Bali, MD, from Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Fla.

LIMITATIONS:

The study authors reported no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Dyspareunia is a major indicator of urinary tract infections, being present in 83% of cases.

METHODOLOGY:

- Dyspareunia is a common symptom of UTIs, especially in premenopausal women, but is rarely inquired about during patient evaluations, according to researchers from Florida Atlantic University.

- In 2010, the researchers found that among 3,000 of their female Latinx patients aged 17-72 years in South Florida, 80% of those with UTIs reported experiencing pain during sexual intercourse.

- Since then, they have studied an additional 2,500 patients from the same population.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among all 5,500 patients, 83% of those who had UTIs experienced dyspareunia.

- Eighty percent of women of reproductive age with dyspareunia had an undiagnosed UTI.

- During the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years, dyspareunia was more often associated with genitourinary syndrome than UTIs.

- Ninety-four percent of women with UTI-associated dyspareunia responded positively to antibiotics.

IN PRACTICE:

“We have found that this symptom is extremely important as part of the symptomatology of UTI [and is] frequently found along with the classical symptoms,” the researchers reported. “Why has something so clear, so frequently present, never been described? The answer is simple: Physicians and patients do not talk about sex, despite dyspareunia being more a clinical symptom than a sexual one. Medical schools and residency programs in all areas, especially in obstetrics and gynecology, urology, and psychiatry, have been neglecting the education of physicians-in-training in this important aspect of human health. In conclusion, this is [proof] of how medicine has sometimes been influenced by religion, culture, and social norms far away from science.”

SOURCE:

The data were presented at the 2023 meeting of the Menopause Society. The study was led by Alberto Dominguez-Bali, MD, from Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Fla.

LIMITATIONS:

The study authors reported no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Dyspareunia is a major indicator of urinary tract infections, being present in 83% of cases.

METHODOLOGY:

- Dyspareunia is a common symptom of UTIs, especially in premenopausal women, but is rarely inquired about during patient evaluations, according to researchers from Florida Atlantic University.

- In 2010, the researchers found that among 3,000 of their female Latinx patients aged 17-72 years in South Florida, 80% of those with UTIs reported experiencing pain during sexual intercourse.

- Since then, they have studied an additional 2,500 patients from the same population.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among all 5,500 patients, 83% of those who had UTIs experienced dyspareunia.

- Eighty percent of women of reproductive age with dyspareunia had an undiagnosed UTI.

- During the perimenopausal and postmenopausal years, dyspareunia was more often associated with genitourinary syndrome than UTIs.

- Ninety-four percent of women with UTI-associated dyspareunia responded positively to antibiotics.

IN PRACTICE: