User login

Exercise may counteract genetics for gestational diabetes

Women giving birth for the first time have significantly higher odds of developing gestational diabetes if they have a high polygenic risk score (PRS) and low physical activity, new data suggest.

Researchers, led by Kymberleigh A. Pagel, PhD, with the department of computer science, Indiana University, Bloomington, concluded that physical activity early in pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of gestational diabetes and may help women who are at high risk because of genetic predisposition, age, family history of diabetes, and body mass index.

The researchers included 3,533 women in the analysis (average age, 28.6 years) which was a subcohort of a larger study. They found that physical activity’s association with lower gestational diabetes risk “was particularly significant in individuals who were genetically predisposed to diabetes through PRS or family history,” the authors wrote.

Women with high PRS and low level of physical activity had three times the odds of developing gestational diabetes (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.3-5.3).

Those with high PRS and moderate to high activity levels in early pregnancy (metabolic equivalents of task [METs] of at least 450) had gestational diabetes risk similar to that of the general population, according to the researchers.

The findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Maisa Feghali, MD, a maternal-fetal specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not part of the study, said in an interview she found the link of physical activity and compensation for high predisposition to gestational diabetes most interesting.

“That’s interesting because a lot of studies that have looked at prevention of gestational diabetes either through limited weight gain or through some form of counseling on physical activity have not really shown any benefit,” she noted. “It might just be it’s not just one size fits all and it may be that physical activity is mostly beneficial in those with a high predisposition.”

Research in this area is particularly important as 7% of pregnancies in the United States each year are affected by gestational diabetes and the risk for developing type 2 diabetes “has doubled in the past decade among patients with GD [gestational diabetes],” the authors wrote.

Researchers looked at risks for gestational diabetes in high-risk subgroups, including women who had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 or were at least 35 years old. In that group, women who were either in the in the top 25th percentile for PRS or had low physical activity (METs less than 450) had from 25% to 75% greater risk of developing gestational diabetes.

The findings are consistent with previous research and suggest exercise interventions may be important in improving pregnancy outcomes, the authors wrote.

Christina Han, MD, division director for maternal-fetal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, who was not part of the study, pointed out several limitations of the study, however.

One of the biggest limitations, she said, was that “they excluded two-thirds of the original study. Essentially, they took only Caucasian [White] patients, which is about one-third of the study.” Additionally, the cohort was made up of people who had never had babies.

“Lots of our gestational diabetes patients are not first-time moms, so this makes the generalizability of the study very limited,” Dr. Han said.

She added that none of the sites where the study was conducted were in the South or Northwest, which also adds questions about generalizability.

Dr. Feghali and Dr. Han reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women giving birth for the first time have significantly higher odds of developing gestational diabetes if they have a high polygenic risk score (PRS) and low physical activity, new data suggest.

Researchers, led by Kymberleigh A. Pagel, PhD, with the department of computer science, Indiana University, Bloomington, concluded that physical activity early in pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of gestational diabetes and may help women who are at high risk because of genetic predisposition, age, family history of diabetes, and body mass index.

The researchers included 3,533 women in the analysis (average age, 28.6 years) which was a subcohort of a larger study. They found that physical activity’s association with lower gestational diabetes risk “was particularly significant in individuals who were genetically predisposed to diabetes through PRS or family history,” the authors wrote.

Women with high PRS and low level of physical activity had three times the odds of developing gestational diabetes (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.3-5.3).

Those with high PRS and moderate to high activity levels in early pregnancy (metabolic equivalents of task [METs] of at least 450) had gestational diabetes risk similar to that of the general population, according to the researchers.

The findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Maisa Feghali, MD, a maternal-fetal specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not part of the study, said in an interview she found the link of physical activity and compensation for high predisposition to gestational diabetes most interesting.

“That’s interesting because a lot of studies that have looked at prevention of gestational diabetes either through limited weight gain or through some form of counseling on physical activity have not really shown any benefit,” she noted. “It might just be it’s not just one size fits all and it may be that physical activity is mostly beneficial in those with a high predisposition.”

Research in this area is particularly important as 7% of pregnancies in the United States each year are affected by gestational diabetes and the risk for developing type 2 diabetes “has doubled in the past decade among patients with GD [gestational diabetes],” the authors wrote.

Researchers looked at risks for gestational diabetes in high-risk subgroups, including women who had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 or were at least 35 years old. In that group, women who were either in the in the top 25th percentile for PRS or had low physical activity (METs less than 450) had from 25% to 75% greater risk of developing gestational diabetes.

The findings are consistent with previous research and suggest exercise interventions may be important in improving pregnancy outcomes, the authors wrote.

Christina Han, MD, division director for maternal-fetal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, who was not part of the study, pointed out several limitations of the study, however.

One of the biggest limitations, she said, was that “they excluded two-thirds of the original study. Essentially, they took only Caucasian [White] patients, which is about one-third of the study.” Additionally, the cohort was made up of people who had never had babies.

“Lots of our gestational diabetes patients are not first-time moms, so this makes the generalizability of the study very limited,” Dr. Han said.

She added that none of the sites where the study was conducted were in the South or Northwest, which also adds questions about generalizability.

Dr. Feghali and Dr. Han reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women giving birth for the first time have significantly higher odds of developing gestational diabetes if they have a high polygenic risk score (PRS) and low physical activity, new data suggest.

Researchers, led by Kymberleigh A. Pagel, PhD, with the department of computer science, Indiana University, Bloomington, concluded that physical activity early in pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of gestational diabetes and may help women who are at high risk because of genetic predisposition, age, family history of diabetes, and body mass index.

The researchers included 3,533 women in the analysis (average age, 28.6 years) which was a subcohort of a larger study. They found that physical activity’s association with lower gestational diabetes risk “was particularly significant in individuals who were genetically predisposed to diabetes through PRS or family history,” the authors wrote.

Women with high PRS and low level of physical activity had three times the odds of developing gestational diabetes (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.3-5.3).

Those with high PRS and moderate to high activity levels in early pregnancy (metabolic equivalents of task [METs] of at least 450) had gestational diabetes risk similar to that of the general population, according to the researchers.

The findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Maisa Feghali, MD, a maternal-fetal specialist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not part of the study, said in an interview she found the link of physical activity and compensation for high predisposition to gestational diabetes most interesting.

“That’s interesting because a lot of studies that have looked at prevention of gestational diabetes either through limited weight gain or through some form of counseling on physical activity have not really shown any benefit,” she noted. “It might just be it’s not just one size fits all and it may be that physical activity is mostly beneficial in those with a high predisposition.”

Research in this area is particularly important as 7% of pregnancies in the United States each year are affected by gestational diabetes and the risk for developing type 2 diabetes “has doubled in the past decade among patients with GD [gestational diabetes],” the authors wrote.

Researchers looked at risks for gestational diabetes in high-risk subgroups, including women who had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 or were at least 35 years old. In that group, women who were either in the in the top 25th percentile for PRS or had low physical activity (METs less than 450) had from 25% to 75% greater risk of developing gestational diabetes.

The findings are consistent with previous research and suggest exercise interventions may be important in improving pregnancy outcomes, the authors wrote.

Christina Han, MD, division director for maternal-fetal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, who was not part of the study, pointed out several limitations of the study, however.

One of the biggest limitations, she said, was that “they excluded two-thirds of the original study. Essentially, they took only Caucasian [White] patients, which is about one-third of the study.” Additionally, the cohort was made up of people who had never had babies.

“Lots of our gestational diabetes patients are not first-time moms, so this makes the generalizability of the study very limited,” Dr. Han said.

She added that none of the sites where the study was conducted were in the South or Northwest, which also adds questions about generalizability.

Dr. Feghali and Dr. Han reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Hormonal therapy a safe, long term option for older women with recalcitrant acne

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”

Such . In fact, 82% fail multiple courses of systemic antibiotics and 32% relapse after using isotretinoin, Dr. Murase, director of medical dermatology consultative services and patch testing at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In her clinical experience, hormonal therapy is a safe long-term option for recalcitrant acne in postmenarcheal females over the age of 14. “Although oral antibiotics are going to be superior to hormonal therapy in the first month or two, when you get to about six months, they have equivalent efficacy,” she said.

Telltale signs of acne associated with androgen excess include the development of nodulocystic papules along the jawline and small comedones over the forehead. Female patients with acne may request that labs be ordered to check their hormone levels, but that often is not necessary, according to Dr. Murase, who is also associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “There aren’t strict guidelines to indicate when you should perform hormonal testing, but warning signs that warrant further evaluation include hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, virilization, infertility, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and sudden onset of severe acne. The most common situation that warrants hormonal testing is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).”

When there is a strong suspicion for hyperandrogenism, essential labs include free and total testosterone. Free testosterone is commonly elevated in patients with PCOS and total testosterone levels over 200 ng/dL is suggestive of an ovarian tumor. Other essential labs include 17-hyydroxyprogesterone (values greater than 200 ng/dL indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S); levels over 8,000 mcg/dL indicate an adrenal tumor, while levels in the 4,000-8,000 mcg/dL range indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Helpful lab tests to consider include the ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone; a 3:1 ratio or greater is suggestive for PCOS. “Ordering a prolactin level can also help, especially if patients are describing issues with headaches, which could indicate a pituitary tumor,” Dr. Murase added. Measuring sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels can also be helpful. “If a patient has been on oral contraceptives for a long time, it increases their SHBG,” which, in older women, she said, “is inversely related to the development of type 2 diabetes.”

All labs for hyperandrogenism should be performed early in the morning on day 3 of the patient’s menstrual cycle. “If patients are on some kind of hormonal therapy, they need to be off of it for at least 6 weeks in order for you get a relevant test,” she said. Other relevant labs to consider include fasting glucose and lipids, cortisol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Oral contraceptives

Estrogen contained in oral contraceptives (OCs) provides the most benefit to acne patients. “It reduces sebum production, decreases free testosterone and DHEA-S by stimulating SHBG synthesis in the liver, inhibits 5-alpha-reductase, which decreases peripheral testosterone conversion, and it decreases the production of ovarian and adrenal androgens,” Dr. Murase explained. “On average, you can get about 40%-70% reduction of lesion count, which is pretty good.”

Progestins with low androgenetic activity are the most helpful for acne, including norgestimate, desogestrel, and drospirenone. FDA-approved OC options include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, EstroStep, Yaz, and Beyaz. None has data showing superior efficacy.

No Pap smear or pelvic exam is required when prescribing OCs, but the risk of clotting should be discussed with patients. According to Dr. Murase, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at baseline is about 1 per 10,000 woman-years, while the risk of DVT after 1 year on an OC is 3.4 per 10,000 years.

“This is a very mild increased risk that we’re talking about, but it is relevant in smokers, in those with hypertension, and in those who are diabetic,” she said. As for the risk of cancer associated with the use of OCs, a large collaborative study found a relative risk of 1.24 for developing breast cancer (not dose or duration related), but a risk reduction for endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancer.

The most common side effects associated with OCs are unscheduled bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and possible weight gain. Concomitant antibiotics can be used, with the exception of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin. “That’s the main antibiotic we have to worry about that could affect the efficacy of the birth control pill,” she said. “It accounts for about three-quarters of pregnancies on antibiotics.”

Tetracyclines do not appear to increase the rate of birth defects with incidental first-trimester exposure, and data are reassuring but “tetracycline should be stopped within the first trimester as soon as the patient discovers she is pregnant,” Dr. Murase said.

Contraindications for OCs include being pregnant or breastfeeding; history of stroke, venous thromboembolism, or MI; history of smoking and being over age 35; uncontrolled hypertension; migraines with focal symptoms/aura; current or past breast cancer; hypercholesterolemia; diabetes with end-organ damage or having diabetes over age 35; liver issues such as a tumor, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis; and a history of major surgery with prolonged immobilization.

Spironolactone

Another treatment option is spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks aldosterone at a dose of 25 mg/day. At doses of 50-100 mg/day, it blocks androgen. “It can be used in combination with an oral contraceptive, with the rates of efficacy reported to range between 33% and 85%,” Dr. Murase said.

Spironolactone can also reduce hirsutism, improve androgenetic alopecia, and lower blood pressure by about 5 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic. Dr. Murase usually checks blood pressure in patients, and “only if they’re really low I’ll talk about the potential for postural hypotension and the fact that you can get a little bit dizzy when going from a position of lying down to standing up.” Potassium levels should be checked at baseline and 4 weeks in patients older than age 46, in those with cardiac and/or renal disease, or in those on concomitant drospirenone or a third-generation progestin.

Spironolactone is classified as a pregnancy category D drug that could compromise the genital development of a male fetus. “So the onus is on us as providers to have the conversation with our patient,” she said. “If you’re putting a patient on spironolactone and they are of child-bearing age, you need to make sure that you’ve had the conversation with them about the fact that they should not get pregnant while on the medicine.”

Spironolactone also has a boxed warning citing the development of benign tumors in animal studies. That warning is based on studies in rats at doses of 10-150 mg/kg per day, “which is an extremely high dose and would never be given in humans,” said Dr. Murase, who has coauthored CME content regarding the safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation.

In humans, there has been no evidence of the development of benign tumors associated with spironolactone therapy, and “there has been a decreased risk of prostate cancer and no association with its use and the development of breast, ovarian, bladder, kidney, gastric, or esophageal cancer,” she said.

Dr. Murase noted that during pregnancy, first-line oral antibiotics include amoxicillin for acne rosacea and cefadroxil for acne vulgaris. Macrolides are a second-line choice because of an increase in atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis that have been reported with first-trimester exposure.

“Erythromycin is the preferred choice over azithromycin and clarithromycin because it has the most data, [but] erythromycin estolate has been associated with increased AST levels in the second trimester,” she said. “It occurs in about 10% of cases and is reversible. Erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not have this risk, and those are preferable.”

Dr. Murase disclosed that she has been a paid speaker of unbranded medical content for Regeneron and UCB. She is also a member of the advisory board for Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, UCB, and Genzyme/Sanofi.

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”

Such . In fact, 82% fail multiple courses of systemic antibiotics and 32% relapse after using isotretinoin, Dr. Murase, director of medical dermatology consultative services and patch testing at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In her clinical experience, hormonal therapy is a safe long-term option for recalcitrant acne in postmenarcheal females over the age of 14. “Although oral antibiotics are going to be superior to hormonal therapy in the first month or two, when you get to about six months, they have equivalent efficacy,” she said.

Telltale signs of acne associated with androgen excess include the development of nodulocystic papules along the jawline and small comedones over the forehead. Female patients with acne may request that labs be ordered to check their hormone levels, but that often is not necessary, according to Dr. Murase, who is also associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “There aren’t strict guidelines to indicate when you should perform hormonal testing, but warning signs that warrant further evaluation include hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, virilization, infertility, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and sudden onset of severe acne. The most common situation that warrants hormonal testing is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).”

When there is a strong suspicion for hyperandrogenism, essential labs include free and total testosterone. Free testosterone is commonly elevated in patients with PCOS and total testosterone levels over 200 ng/dL is suggestive of an ovarian tumor. Other essential labs include 17-hyydroxyprogesterone (values greater than 200 ng/dL indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S); levels over 8,000 mcg/dL indicate an adrenal tumor, while levels in the 4,000-8,000 mcg/dL range indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Helpful lab tests to consider include the ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone; a 3:1 ratio or greater is suggestive for PCOS. “Ordering a prolactin level can also help, especially if patients are describing issues with headaches, which could indicate a pituitary tumor,” Dr. Murase added. Measuring sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels can also be helpful. “If a patient has been on oral contraceptives for a long time, it increases their SHBG,” which, in older women, she said, “is inversely related to the development of type 2 diabetes.”

All labs for hyperandrogenism should be performed early in the morning on day 3 of the patient’s menstrual cycle. “If patients are on some kind of hormonal therapy, they need to be off of it for at least 6 weeks in order for you get a relevant test,” she said. Other relevant labs to consider include fasting glucose and lipids, cortisol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Oral contraceptives

Estrogen contained in oral contraceptives (OCs) provides the most benefit to acne patients. “It reduces sebum production, decreases free testosterone and DHEA-S by stimulating SHBG synthesis in the liver, inhibits 5-alpha-reductase, which decreases peripheral testosterone conversion, and it decreases the production of ovarian and adrenal androgens,” Dr. Murase explained. “On average, you can get about 40%-70% reduction of lesion count, which is pretty good.”

Progestins with low androgenetic activity are the most helpful for acne, including norgestimate, desogestrel, and drospirenone. FDA-approved OC options include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, EstroStep, Yaz, and Beyaz. None has data showing superior efficacy.

No Pap smear or pelvic exam is required when prescribing OCs, but the risk of clotting should be discussed with patients. According to Dr. Murase, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at baseline is about 1 per 10,000 woman-years, while the risk of DVT after 1 year on an OC is 3.4 per 10,000 years.

“This is a very mild increased risk that we’re talking about, but it is relevant in smokers, in those with hypertension, and in those who are diabetic,” she said. As for the risk of cancer associated with the use of OCs, a large collaborative study found a relative risk of 1.24 for developing breast cancer (not dose or duration related), but a risk reduction for endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancer.

The most common side effects associated with OCs are unscheduled bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and possible weight gain. Concomitant antibiotics can be used, with the exception of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin. “That’s the main antibiotic we have to worry about that could affect the efficacy of the birth control pill,” she said. “It accounts for about three-quarters of pregnancies on antibiotics.”

Tetracyclines do not appear to increase the rate of birth defects with incidental first-trimester exposure, and data are reassuring but “tetracycline should be stopped within the first trimester as soon as the patient discovers she is pregnant,” Dr. Murase said.

Contraindications for OCs include being pregnant or breastfeeding; history of stroke, venous thromboembolism, or MI; history of smoking and being over age 35; uncontrolled hypertension; migraines with focal symptoms/aura; current or past breast cancer; hypercholesterolemia; diabetes with end-organ damage or having diabetes over age 35; liver issues such as a tumor, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis; and a history of major surgery with prolonged immobilization.

Spironolactone

Another treatment option is spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks aldosterone at a dose of 25 mg/day. At doses of 50-100 mg/day, it blocks androgen. “It can be used in combination with an oral contraceptive, with the rates of efficacy reported to range between 33% and 85%,” Dr. Murase said.

Spironolactone can also reduce hirsutism, improve androgenetic alopecia, and lower blood pressure by about 5 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic. Dr. Murase usually checks blood pressure in patients, and “only if they’re really low I’ll talk about the potential for postural hypotension and the fact that you can get a little bit dizzy when going from a position of lying down to standing up.” Potassium levels should be checked at baseline and 4 weeks in patients older than age 46, in those with cardiac and/or renal disease, or in those on concomitant drospirenone or a third-generation progestin.

Spironolactone is classified as a pregnancy category D drug that could compromise the genital development of a male fetus. “So the onus is on us as providers to have the conversation with our patient,” she said. “If you’re putting a patient on spironolactone and they are of child-bearing age, you need to make sure that you’ve had the conversation with them about the fact that they should not get pregnant while on the medicine.”

Spironolactone also has a boxed warning citing the development of benign tumors in animal studies. That warning is based on studies in rats at doses of 10-150 mg/kg per day, “which is an extremely high dose and would never be given in humans,” said Dr. Murase, who has coauthored CME content regarding the safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation.

In humans, there has been no evidence of the development of benign tumors associated with spironolactone therapy, and “there has been a decreased risk of prostate cancer and no association with its use and the development of breast, ovarian, bladder, kidney, gastric, or esophageal cancer,” she said.

Dr. Murase noted that during pregnancy, first-line oral antibiotics include amoxicillin for acne rosacea and cefadroxil for acne vulgaris. Macrolides are a second-line choice because of an increase in atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis that have been reported with first-trimester exposure.

“Erythromycin is the preferred choice over azithromycin and clarithromycin because it has the most data, [but] erythromycin estolate has been associated with increased AST levels in the second trimester,” she said. “It occurs in about 10% of cases and is reversible. Erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not have this risk, and those are preferable.”

Dr. Murase disclosed that she has been a paid speaker of unbranded medical content for Regeneron and UCB. She is also a member of the advisory board for Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, UCB, and Genzyme/Sanofi.

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”

Such . In fact, 82% fail multiple courses of systemic antibiotics and 32% relapse after using isotretinoin, Dr. Murase, director of medical dermatology consultative services and patch testing at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In her clinical experience, hormonal therapy is a safe long-term option for recalcitrant acne in postmenarcheal females over the age of 14. “Although oral antibiotics are going to be superior to hormonal therapy in the first month or two, when you get to about six months, they have equivalent efficacy,” she said.

Telltale signs of acne associated with androgen excess include the development of nodulocystic papules along the jawline and small comedones over the forehead. Female patients with acne may request that labs be ordered to check their hormone levels, but that often is not necessary, according to Dr. Murase, who is also associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “There aren’t strict guidelines to indicate when you should perform hormonal testing, but warning signs that warrant further evaluation include hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, virilization, infertility, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and sudden onset of severe acne. The most common situation that warrants hormonal testing is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).”

When there is a strong suspicion for hyperandrogenism, essential labs include free and total testosterone. Free testosterone is commonly elevated in patients with PCOS and total testosterone levels over 200 ng/dL is suggestive of an ovarian tumor. Other essential labs include 17-hyydroxyprogesterone (values greater than 200 ng/dL indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S); levels over 8,000 mcg/dL indicate an adrenal tumor, while levels in the 4,000-8,000 mcg/dL range indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Helpful lab tests to consider include the ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone; a 3:1 ratio or greater is suggestive for PCOS. “Ordering a prolactin level can also help, especially if patients are describing issues with headaches, which could indicate a pituitary tumor,” Dr. Murase added. Measuring sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels can also be helpful. “If a patient has been on oral contraceptives for a long time, it increases their SHBG,” which, in older women, she said, “is inversely related to the development of type 2 diabetes.”

All labs for hyperandrogenism should be performed early in the morning on day 3 of the patient’s menstrual cycle. “If patients are on some kind of hormonal therapy, they need to be off of it for at least 6 weeks in order for you get a relevant test,” she said. Other relevant labs to consider include fasting glucose and lipids, cortisol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Oral contraceptives

Estrogen contained in oral contraceptives (OCs) provides the most benefit to acne patients. “It reduces sebum production, decreases free testosterone and DHEA-S by stimulating SHBG synthesis in the liver, inhibits 5-alpha-reductase, which decreases peripheral testosterone conversion, and it decreases the production of ovarian and adrenal androgens,” Dr. Murase explained. “On average, you can get about 40%-70% reduction of lesion count, which is pretty good.”

Progestins with low androgenetic activity are the most helpful for acne, including norgestimate, desogestrel, and drospirenone. FDA-approved OC options include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, EstroStep, Yaz, and Beyaz. None has data showing superior efficacy.

No Pap smear or pelvic exam is required when prescribing OCs, but the risk of clotting should be discussed with patients. According to Dr. Murase, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at baseline is about 1 per 10,000 woman-years, while the risk of DVT after 1 year on an OC is 3.4 per 10,000 years.

“This is a very mild increased risk that we’re talking about, but it is relevant in smokers, in those with hypertension, and in those who are diabetic,” she said. As for the risk of cancer associated with the use of OCs, a large collaborative study found a relative risk of 1.24 for developing breast cancer (not dose or duration related), but a risk reduction for endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancer.

The most common side effects associated with OCs are unscheduled bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and possible weight gain. Concomitant antibiotics can be used, with the exception of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin. “That’s the main antibiotic we have to worry about that could affect the efficacy of the birth control pill,” she said. “It accounts for about three-quarters of pregnancies on antibiotics.”

Tetracyclines do not appear to increase the rate of birth defects with incidental first-trimester exposure, and data are reassuring but “tetracycline should be stopped within the first trimester as soon as the patient discovers she is pregnant,” Dr. Murase said.

Contraindications for OCs include being pregnant or breastfeeding; history of stroke, venous thromboembolism, or MI; history of smoking and being over age 35; uncontrolled hypertension; migraines with focal symptoms/aura; current or past breast cancer; hypercholesterolemia; diabetes with end-organ damage or having diabetes over age 35; liver issues such as a tumor, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis; and a history of major surgery with prolonged immobilization.

Spironolactone

Another treatment option is spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks aldosterone at a dose of 25 mg/day. At doses of 50-100 mg/day, it blocks androgen. “It can be used in combination with an oral contraceptive, with the rates of efficacy reported to range between 33% and 85%,” Dr. Murase said.

Spironolactone can also reduce hirsutism, improve androgenetic alopecia, and lower blood pressure by about 5 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic. Dr. Murase usually checks blood pressure in patients, and “only if they’re really low I’ll talk about the potential for postural hypotension and the fact that you can get a little bit dizzy when going from a position of lying down to standing up.” Potassium levels should be checked at baseline and 4 weeks in patients older than age 46, in those with cardiac and/or renal disease, or in those on concomitant drospirenone or a third-generation progestin.

Spironolactone is classified as a pregnancy category D drug that could compromise the genital development of a male fetus. “So the onus is on us as providers to have the conversation with our patient,” she said. “If you’re putting a patient on spironolactone and they are of child-bearing age, you need to make sure that you’ve had the conversation with them about the fact that they should not get pregnant while on the medicine.”

Spironolactone also has a boxed warning citing the development of benign tumors in animal studies. That warning is based on studies in rats at doses of 10-150 mg/kg per day, “which is an extremely high dose and would never be given in humans,” said Dr. Murase, who has coauthored CME content regarding the safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation.

In humans, there has been no evidence of the development of benign tumors associated with spironolactone therapy, and “there has been a decreased risk of prostate cancer and no association with its use and the development of breast, ovarian, bladder, kidney, gastric, or esophageal cancer,” she said.

Dr. Murase noted that during pregnancy, first-line oral antibiotics include amoxicillin for acne rosacea and cefadroxil for acne vulgaris. Macrolides are a second-line choice because of an increase in atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis that have been reported with first-trimester exposure.

“Erythromycin is the preferred choice over azithromycin and clarithromycin because it has the most data, [but] erythromycin estolate has been associated with increased AST levels in the second trimester,” she said. “It occurs in about 10% of cases and is reversible. Erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not have this risk, and those are preferable.”

Dr. Murase disclosed that she has been a paid speaker of unbranded medical content for Regeneron and UCB. She is also a member of the advisory board for Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, UCB, and Genzyme/Sanofi.

AT PDA 2022

New ovulatory disorder classifications from FIGO replace 50-year-old system

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

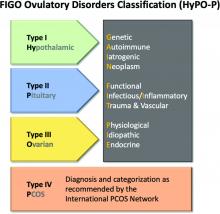

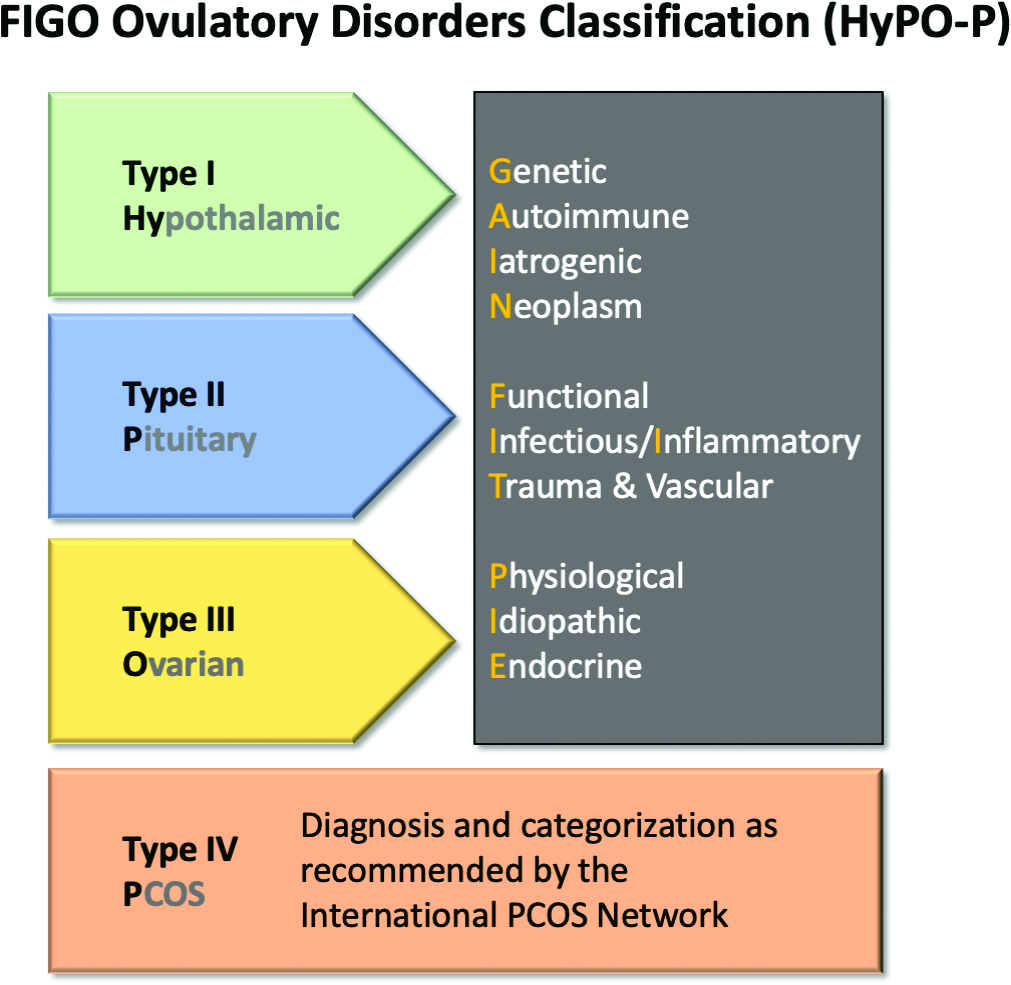

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS

Increased risk of dyspareunia following cesarean section

There is no evidence to support postulated associations between mode of delivery and subsequent maternal sexual enjoyment or frequency of intercourse, according to a new study from the University of Bristol (England). However, cesarean section was shown to be associated with a 74% increased risk of dyspareunia, and this was not necessarily due to abdominal scarring, the researchers said.

A team from the University of Bristol and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden used data from participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study also dubbed “Children of the 90s” and involving more than 14,000 women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992. The study has been following the health and development of the parents, their children, and now their grandchildren in detail ever since.

The new study, published in BJOG, aimed to assess whether cesarean section maintains sexual well-being compared with vaginal delivery, as has been suggested to occur because of the reduced risk of genital damage – less chance of tearing – and the maintenance of vaginal tone. There is some evidence that cesarean section is associated with an increased risk of sexual problems such as dyspareunia, but few studies have looked at the postbirth period long term.

Mode of delivery was abstracted from routine obstetric records and recorded as one of either spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD), cesarean section, assisted breech, breech extraction, forceps, or vacuum extraction. Women whose records showed “other” as mode of delivery or whose notes contained conflicting modes of delivery were excluded.

Self-reported questionnaires asking about general health and lifestyle and including questions relating to sexual enjoyment and frequency were collected at 33 months and at 5, 12, and 18 years postpartum. Women were asked if they enjoyed sexual intercourse, with possible responses of:

- Yes, very much.

- Yes, somewhat.

- No, not a lot.

- No, not at all.

- No sex at the moment.

Possible sexual frequency responses were:

- Not at all.

- Less than once a month.

- 1-3 times a month.

- About once a week.

- 2-4 times a week.

- 5 or more times a week.

First study to look at sexual frequency

The team noted that theirs is the first study investigating the association of mode of delivery with sexual frequency. “Although it may be less important for well-being than sexual enjoyment or sex-related pain, it is an important measure to observe alongside other sexual outcomes,” they said.

Separately, sex-related pain, in the vagina during sex or elsewhere after sex, was assessed once, at 11 years post partum.

The data showed that women who had a cesarean section (11% of the sample) tended to be older than those who had vaginal delivery, with a higher mean body mass index (24.2 versus 22.8 kg/m2), and were more likely to be nulliparous at the time of the index pregnancy (54% versus 44%).

There was no significant difference between cesarean section and vaginal delivery in terms of responses for sexual enjoyment or frequency at any time after childbirth, the authors said. Nor, in adjusted models, was there evidence of associations between the type of vaginal delivery and sexual enjoyment or frequency outcomes.

Pain during sex increased more than a decade after cesarean

However, while the majority of respondents reported no intercourse-related pain, those who delivered via cesarean were more likely than those who gave birth vaginally to report sex-related pain at 11 years post partum. This was specifically an elevated incidence of pain in the vagina during sex, with an odds ratio of 1.74 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08) in the adjusted model. This finding was consistent for emergency and elective cesarean section separately – both types were associated with increased dyspareunia, compared with vaginal delivery.

The dataset did not include measures of individual prenatal sex-related pain and, therefore, “it is unknown from this study whether Caesarean section causes sex-related pain, as suggested by the findings, or whether prenatal sex-related pain predicts both Caesarean section and postnatal sex-related pain,” the researchers said.

“Longitudinal data on sex-related pain need to be collected both before and after parturition,” they recommend, to clarify the direction of a possible effect between cesarean section and dyspareunia.

Cesarean does not protect against sexual dysfunction

Meanwhile, “For women considering a planned Caesarean section in an uncomplicated pregnancy, evidence suggesting that Caesarean section may not protect against sexual dysfunction may help inform their decision-making in the antenatal period.”

Lead author Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, said: “Rates of Caesarean section have been rising over the last 20 years due to many contributing factors and, importantly, it has been suggested that Caesarean section maintains sexual wellbeing compared with vaginal delivery. It is crucial that a whole range of maternal and foetal outcomes following Caesarean section are investigated, including sexual wellbeing, to appropriately inform decision-making both pre- and postnatally.

“This research provides expectant mothers, as well as women who have given birth, with really important information and demonstrates that there was no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via Caesarean section and those who delivered vaginally. It also suggests that Caesarean section may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought, where sex-related pain was higher among women who gave birth via Caesarean section more than 10 years postpartum.”

Asked to comment on the research, Dr. Leila Frodsham, consultant gynecologist and spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told this news organization: “Sexual pain disorders affect 7.5% of women of all ages, but there are peaks: during the start of sexual activity, if subfertility is an issue, after childbirth, and in the peri/menopause. It can be up to three times more prevalent at these peak times.

“Many women with sexual pain are worried when they consider starting a family and request a Caesarean birth to reduce risk of worsening their pain. However, this study has demonstrated that a Caesarean birth is associated with increased sexual pain longer term, which is very useful for helping women to plan their births.

“While more research about postpartum sexual wellbeing is needed, the findings of this study are reassuring to those who are pregnant as it found no difference in the enjoyment or frequency of sex in the years after a vaginal or a Caesarean birth.

“Most women in the U.K. recover well whether they have a vaginal or a Caesarean birth. Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

There is no evidence to support postulated associations between mode of delivery and subsequent maternal sexual enjoyment or frequency of intercourse, according to a new study from the University of Bristol (England). However, cesarean section was shown to be associated with a 74% increased risk of dyspareunia, and this was not necessarily due to abdominal scarring, the researchers said.

A team from the University of Bristol and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden used data from participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study also dubbed “Children of the 90s” and involving more than 14,000 women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992. The study has been following the health and development of the parents, their children, and now their grandchildren in detail ever since.

The new study, published in BJOG, aimed to assess whether cesarean section maintains sexual well-being compared with vaginal delivery, as has been suggested to occur because of the reduced risk of genital damage – less chance of tearing – and the maintenance of vaginal tone. There is some evidence that cesarean section is associated with an increased risk of sexual problems such as dyspareunia, but few studies have looked at the postbirth period long term.

Mode of delivery was abstracted from routine obstetric records and recorded as one of either spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD), cesarean section, assisted breech, breech extraction, forceps, or vacuum extraction. Women whose records showed “other” as mode of delivery or whose notes contained conflicting modes of delivery were excluded.

Self-reported questionnaires asking about general health and lifestyle and including questions relating to sexual enjoyment and frequency were collected at 33 months and at 5, 12, and 18 years postpartum. Women were asked if they enjoyed sexual intercourse, with possible responses of:

- Yes, very much.

- Yes, somewhat.

- No, not a lot.

- No, not at all.

- No sex at the moment.

Possible sexual frequency responses were:

- Not at all.

- Less than once a month.

- 1-3 times a month.

- About once a week.

- 2-4 times a week.

- 5 or more times a week.

First study to look at sexual frequency

The team noted that theirs is the first study investigating the association of mode of delivery with sexual frequency. “Although it may be less important for well-being than sexual enjoyment or sex-related pain, it is an important measure to observe alongside other sexual outcomes,” they said.

Separately, sex-related pain, in the vagina during sex or elsewhere after sex, was assessed once, at 11 years post partum.

The data showed that women who had a cesarean section (11% of the sample) tended to be older than those who had vaginal delivery, with a higher mean body mass index (24.2 versus 22.8 kg/m2), and were more likely to be nulliparous at the time of the index pregnancy (54% versus 44%).

There was no significant difference between cesarean section and vaginal delivery in terms of responses for sexual enjoyment or frequency at any time after childbirth, the authors said. Nor, in adjusted models, was there evidence of associations between the type of vaginal delivery and sexual enjoyment or frequency outcomes.

Pain during sex increased more than a decade after cesarean

However, while the majority of respondents reported no intercourse-related pain, those who delivered via cesarean were more likely than those who gave birth vaginally to report sex-related pain at 11 years post partum. This was specifically an elevated incidence of pain in the vagina during sex, with an odds ratio of 1.74 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08) in the adjusted model. This finding was consistent for emergency and elective cesarean section separately – both types were associated with increased dyspareunia, compared with vaginal delivery.

The dataset did not include measures of individual prenatal sex-related pain and, therefore, “it is unknown from this study whether Caesarean section causes sex-related pain, as suggested by the findings, or whether prenatal sex-related pain predicts both Caesarean section and postnatal sex-related pain,” the researchers said.

“Longitudinal data on sex-related pain need to be collected both before and after parturition,” they recommend, to clarify the direction of a possible effect between cesarean section and dyspareunia.

Cesarean does not protect against sexual dysfunction

Meanwhile, “For women considering a planned Caesarean section in an uncomplicated pregnancy, evidence suggesting that Caesarean section may not protect against sexual dysfunction may help inform their decision-making in the antenatal period.”

Lead author Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, said: “Rates of Caesarean section have been rising over the last 20 years due to many contributing factors and, importantly, it has been suggested that Caesarean section maintains sexual wellbeing compared with vaginal delivery. It is crucial that a whole range of maternal and foetal outcomes following Caesarean section are investigated, including sexual wellbeing, to appropriately inform decision-making both pre- and postnatally.

“This research provides expectant mothers, as well as women who have given birth, with really important information and demonstrates that there was no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via Caesarean section and those who delivered vaginally. It also suggests that Caesarean section may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought, where sex-related pain was higher among women who gave birth via Caesarean section more than 10 years postpartum.”

Asked to comment on the research, Dr. Leila Frodsham, consultant gynecologist and spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told this news organization: “Sexual pain disorders affect 7.5% of women of all ages, but there are peaks: during the start of sexual activity, if subfertility is an issue, after childbirth, and in the peri/menopause. It can be up to three times more prevalent at these peak times.

“Many women with sexual pain are worried when they consider starting a family and request a Caesarean birth to reduce risk of worsening their pain. However, this study has demonstrated that a Caesarean birth is associated with increased sexual pain longer term, which is very useful for helping women to plan their births.

“While more research about postpartum sexual wellbeing is needed, the findings of this study are reassuring to those who are pregnant as it found no difference in the enjoyment or frequency of sex in the years after a vaginal or a Caesarean birth.

“Most women in the U.K. recover well whether they have a vaginal or a Caesarean birth. Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

There is no evidence to support postulated associations between mode of delivery and subsequent maternal sexual enjoyment or frequency of intercourse, according to a new study from the University of Bristol (England). However, cesarean section was shown to be associated with a 74% increased risk of dyspareunia, and this was not necessarily due to abdominal scarring, the researchers said.

A team from the University of Bristol and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden used data from participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study also dubbed “Children of the 90s” and involving more than 14,000 women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992. The study has been following the health and development of the parents, their children, and now their grandchildren in detail ever since.

The new study, published in BJOG, aimed to assess whether cesarean section maintains sexual well-being compared with vaginal delivery, as has been suggested to occur because of the reduced risk of genital damage – less chance of tearing – and the maintenance of vaginal tone. There is some evidence that cesarean section is associated with an increased risk of sexual problems such as dyspareunia, but few studies have looked at the postbirth period long term.

Mode of delivery was abstracted from routine obstetric records and recorded as one of either spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD), cesarean section, assisted breech, breech extraction, forceps, or vacuum extraction. Women whose records showed “other” as mode of delivery or whose notes contained conflicting modes of delivery were excluded.

Self-reported questionnaires asking about general health and lifestyle and including questions relating to sexual enjoyment and frequency were collected at 33 months and at 5, 12, and 18 years postpartum. Women were asked if they enjoyed sexual intercourse, with possible responses of:

- Yes, very much.

- Yes, somewhat.

- No, not a lot.

- No, not at all.

- No sex at the moment.

Possible sexual frequency responses were:

- Not at all.

- Less than once a month.

- 1-3 times a month.

- About once a week.

- 2-4 times a week.

- 5 or more times a week.

First study to look at sexual frequency

The team noted that theirs is the first study investigating the association of mode of delivery with sexual frequency. “Although it may be less important for well-being than sexual enjoyment or sex-related pain, it is an important measure to observe alongside other sexual outcomes,” they said.

Separately, sex-related pain, in the vagina during sex or elsewhere after sex, was assessed once, at 11 years post partum.

The data showed that women who had a cesarean section (11% of the sample) tended to be older than those who had vaginal delivery, with a higher mean body mass index (24.2 versus 22.8 kg/m2), and were more likely to be nulliparous at the time of the index pregnancy (54% versus 44%).

There was no significant difference between cesarean section and vaginal delivery in terms of responses for sexual enjoyment or frequency at any time after childbirth, the authors said. Nor, in adjusted models, was there evidence of associations between the type of vaginal delivery and sexual enjoyment or frequency outcomes.

Pain during sex increased more than a decade after cesarean

However, while the majority of respondents reported no intercourse-related pain, those who delivered via cesarean were more likely than those who gave birth vaginally to report sex-related pain at 11 years post partum. This was specifically an elevated incidence of pain in the vagina during sex, with an odds ratio of 1.74 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08) in the adjusted model. This finding was consistent for emergency and elective cesarean section separately – both types were associated with increased dyspareunia, compared with vaginal delivery.

The dataset did not include measures of individual prenatal sex-related pain and, therefore, “it is unknown from this study whether Caesarean section causes sex-related pain, as suggested by the findings, or whether prenatal sex-related pain predicts both Caesarean section and postnatal sex-related pain,” the researchers said.

“Longitudinal data on sex-related pain need to be collected both before and after parturition,” they recommend, to clarify the direction of a possible effect between cesarean section and dyspareunia.

Cesarean does not protect against sexual dysfunction

Meanwhile, “For women considering a planned Caesarean section in an uncomplicated pregnancy, evidence suggesting that Caesarean section may not protect against sexual dysfunction may help inform their decision-making in the antenatal period.”

Lead author Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, said: “Rates of Caesarean section have been rising over the last 20 years due to many contributing factors and, importantly, it has been suggested that Caesarean section maintains sexual wellbeing compared with vaginal delivery. It is crucial that a whole range of maternal and foetal outcomes following Caesarean section are investigated, including sexual wellbeing, to appropriately inform decision-making both pre- and postnatally.

“This research provides expectant mothers, as well as women who have given birth, with really important information and demonstrates that there was no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via Caesarean section and those who delivered vaginally. It also suggests that Caesarean section may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought, where sex-related pain was higher among women who gave birth via Caesarean section more than 10 years postpartum.”

Asked to comment on the research, Dr. Leila Frodsham, consultant gynecologist and spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told this news organization: “Sexual pain disorders affect 7.5% of women of all ages, but there are peaks: during the start of sexual activity, if subfertility is an issue, after childbirth, and in the peri/menopause. It can be up to three times more prevalent at these peak times.

“Many women with sexual pain are worried when they consider starting a family and request a Caesarean birth to reduce risk of worsening their pain. However, this study has demonstrated that a Caesarean birth is associated with increased sexual pain longer term, which is very useful for helping women to plan their births.

“While more research about postpartum sexual wellbeing is needed, the findings of this study are reassuring to those who are pregnant as it found no difference in the enjoyment or frequency of sex in the years after a vaginal or a Caesarean birth.

“Most women in the U.K. recover well whether they have a vaginal or a Caesarean birth. Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences.”