User login

Scalp Wound Closures in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Staples vs Sutures

Limited data exist comparing staples and sutures for scalp closures during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). As a result, the closure method for these scalp wounds is based on surgeon preference without established consensus. The purpose of this study was to survey practicing Mohs surgeons on their scalp wound closure preferences as well as the clinical and economic variables that impact their decisions. Understanding practice habits can guide future trial design, with a goal of creating established criterion for MMS scalp wound closures.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed from April 2019 to June 2019 to fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons using an electronic mailing list from the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). The 10-question survey was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board and the executive committee of the ACMS. Surgeons were asked about their preferred method for scalp wound closure as well as clinical and economic variables that impacted those preferences. Respondents indicated their frequency of using deep sutures, epidermal sutures, and wound undermining on a sliding scale of 0% to 100%. Comparisons were made between practice habits, preferences, and surgeon demographics using t tests. Statistical significance was determined as P<.05.

Results

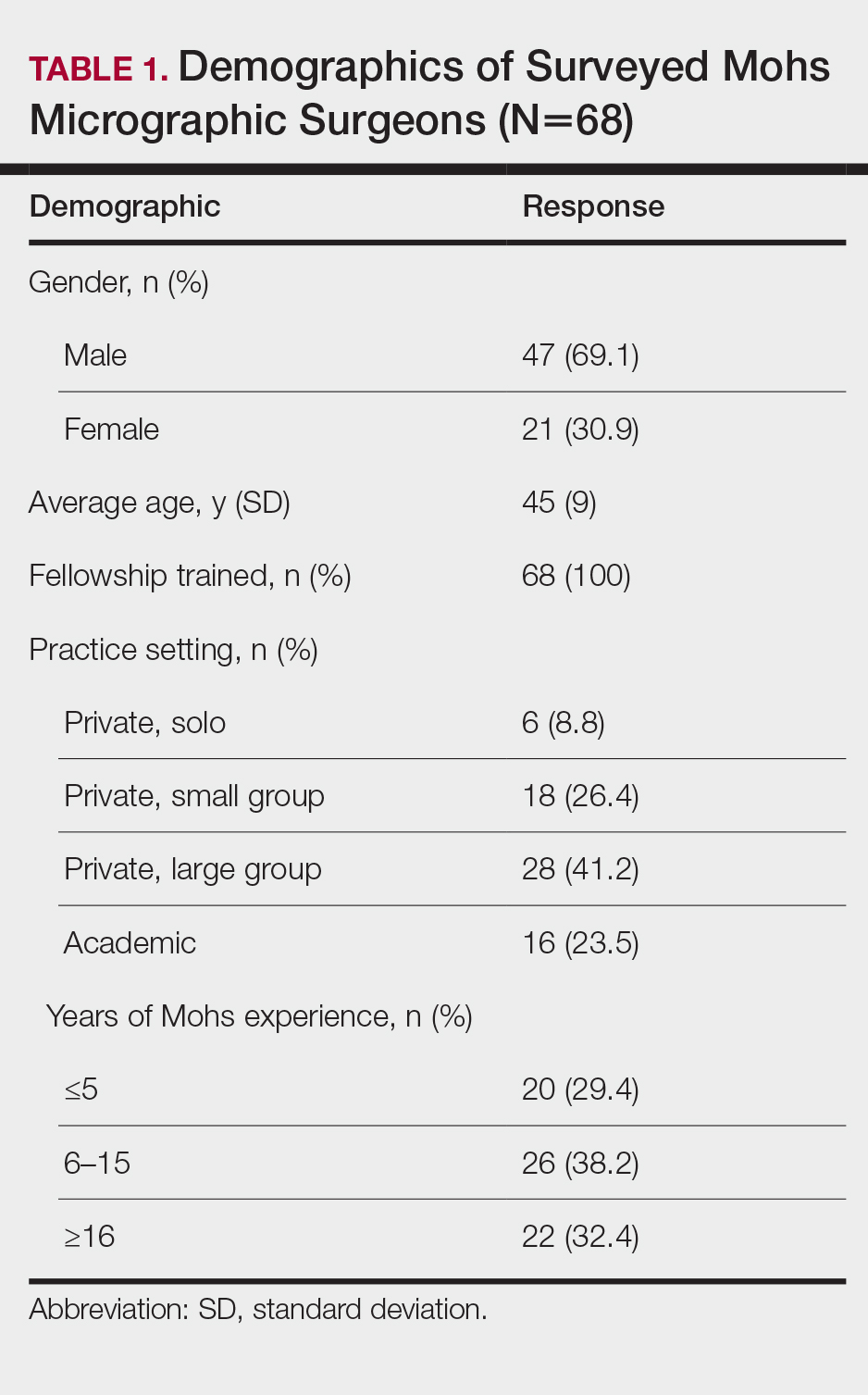

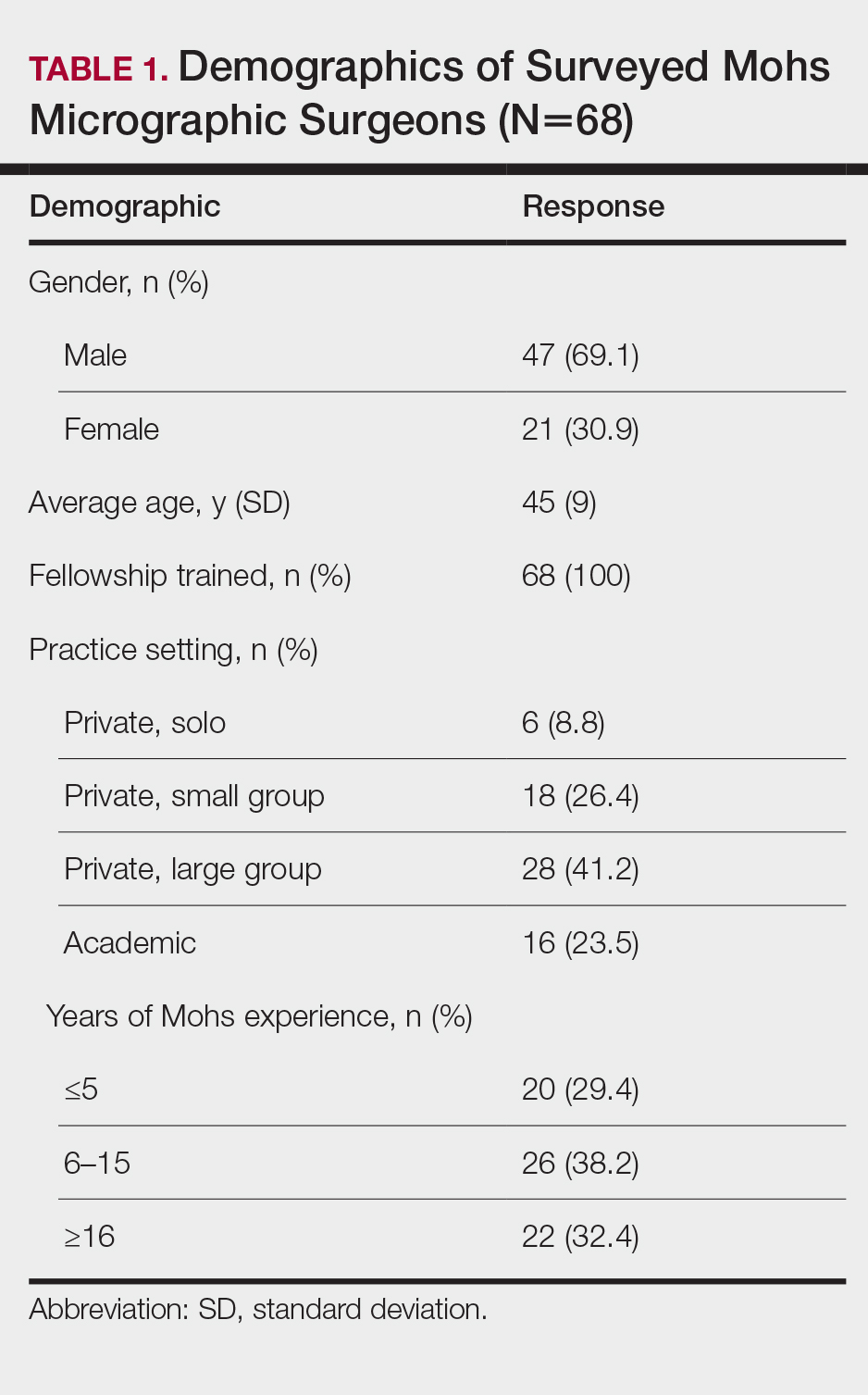

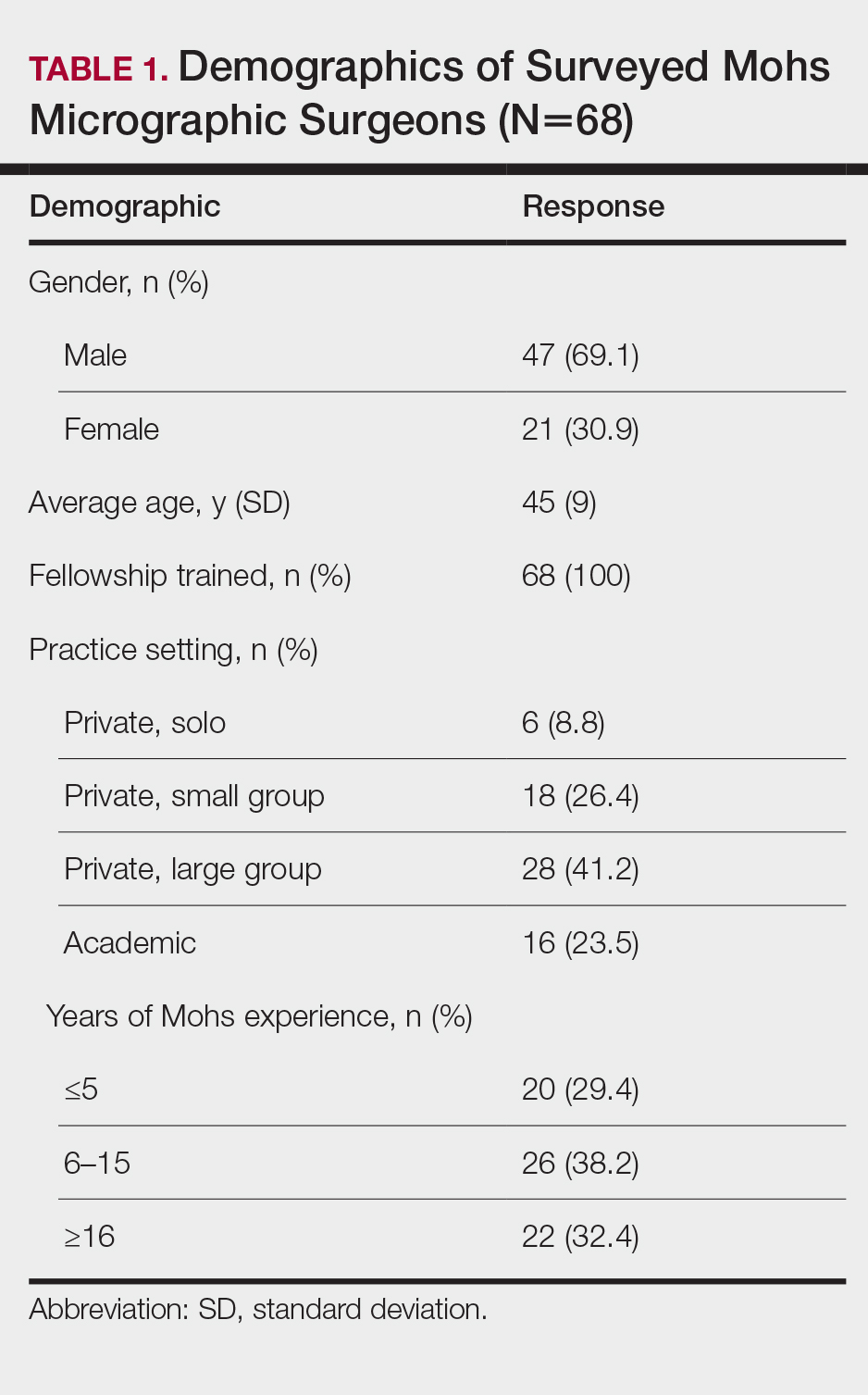

Sixty-eight ACMS fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons completed the survey. The average age of respondents was 45 years; 69.1% (n=47) of respondents were male, and 76.5% (n=52) practiced in a private setting (Table 1). Regardless of epidermal closure type, deep suture placement was used in an average (standard deviation [SD]) of 88.8% (19.5%) of cases overall, which did not statistically differ between years of Mohs experience or practice setting (Table 2). Wound undermining was performed in an average (SD) of 83.0% (24.3%) of cases overall and was more prevalent in private vs academic settings (87.6% [17.8%] vs 65.7% [35.0%]; P<.01). Epidermal sutures were used in an average (SD) of 27.1% (33.5%) of scalp wound cases overall. Surgeons with less experience (≤5 years) used them more frequently (average [SD], 42.7% [36.2%] of cases) than surgeons with more experience (≥16 years; average [SD], 18.8% [32.6%] of cases; P=.037). There was no significant difference between epidermal suture placement rates and practice setting (average [SD], 18.1% [28.1%] of cases for academic providers vs 30.0% [34.8%] of cases with private providers; P=.210).

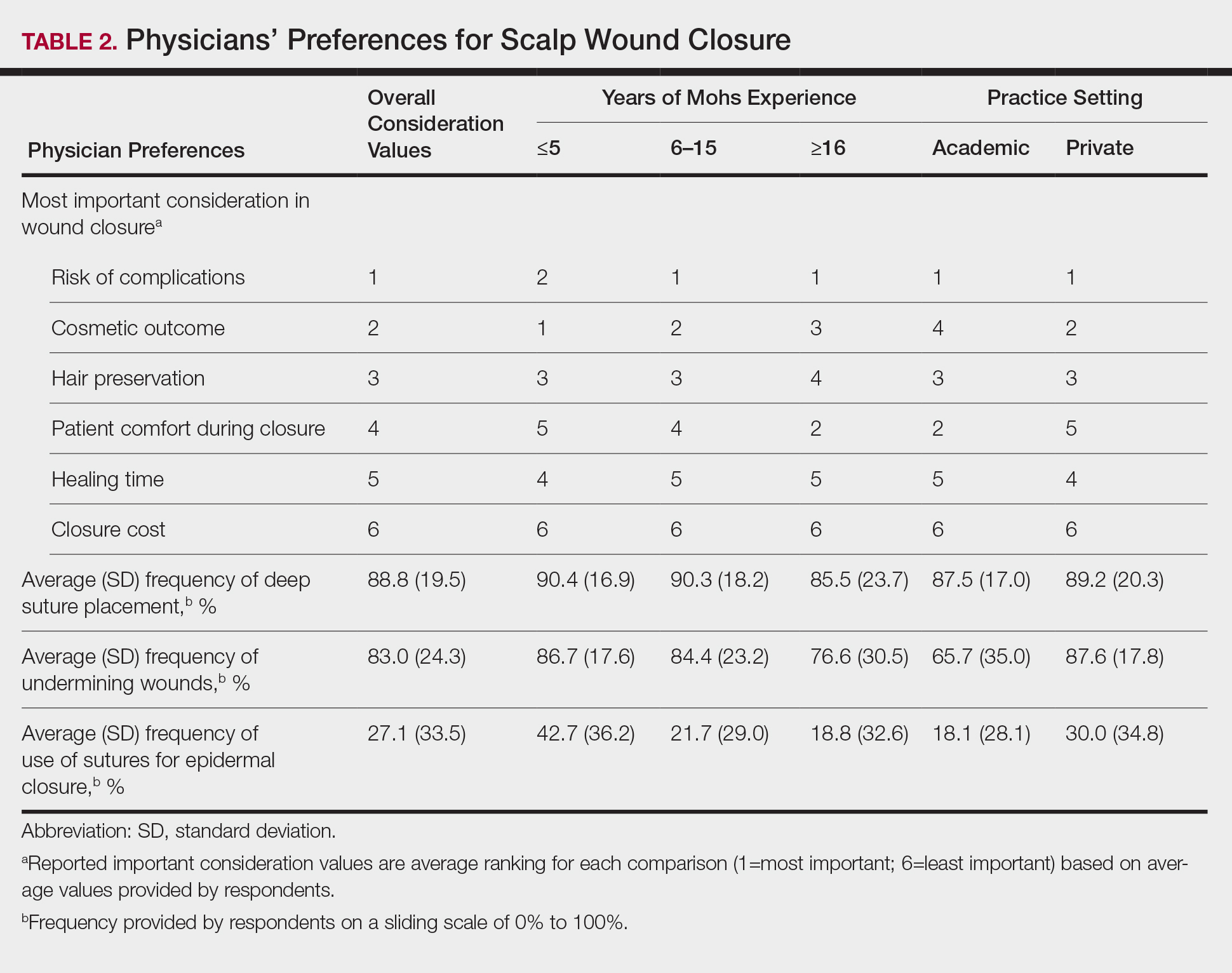

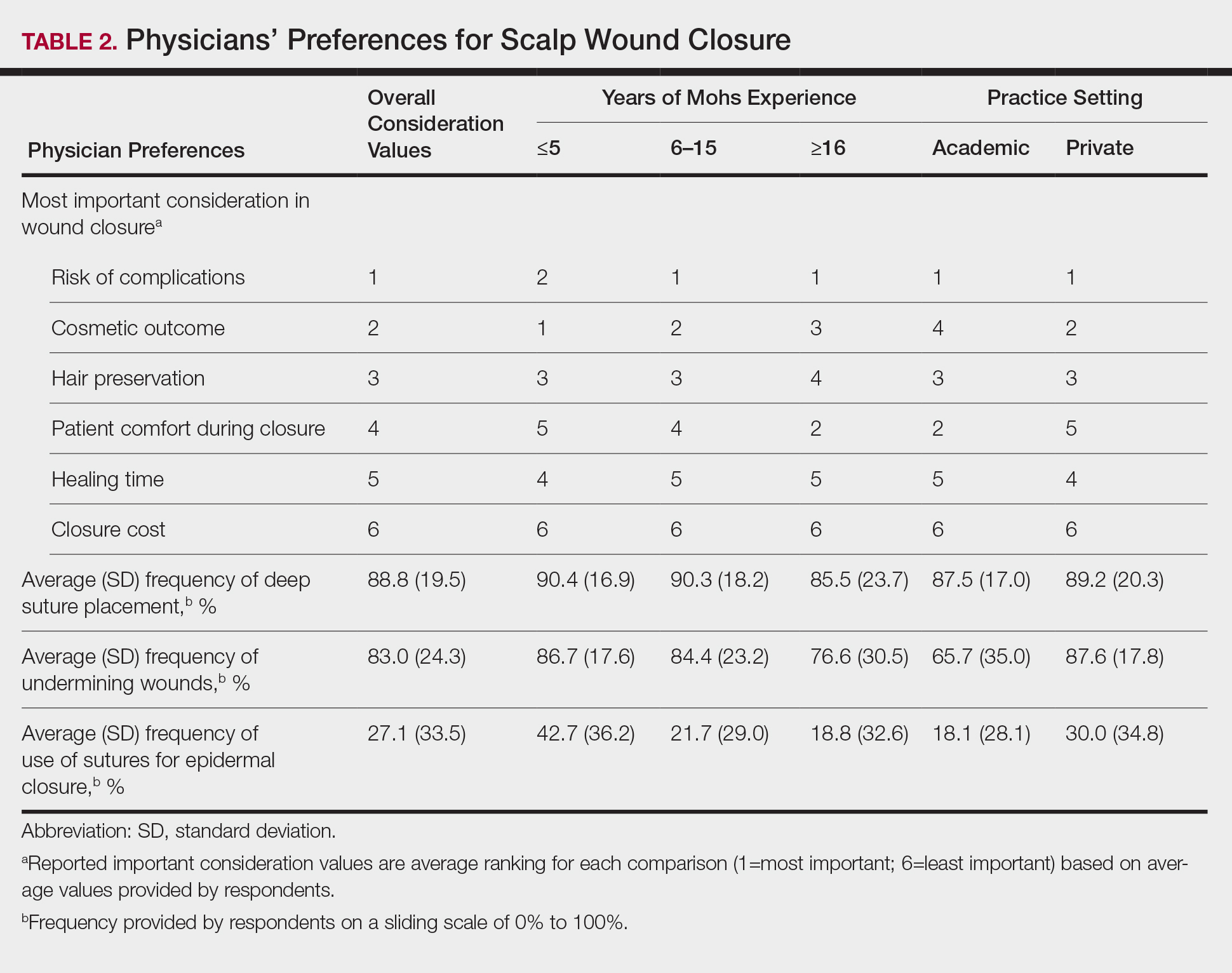

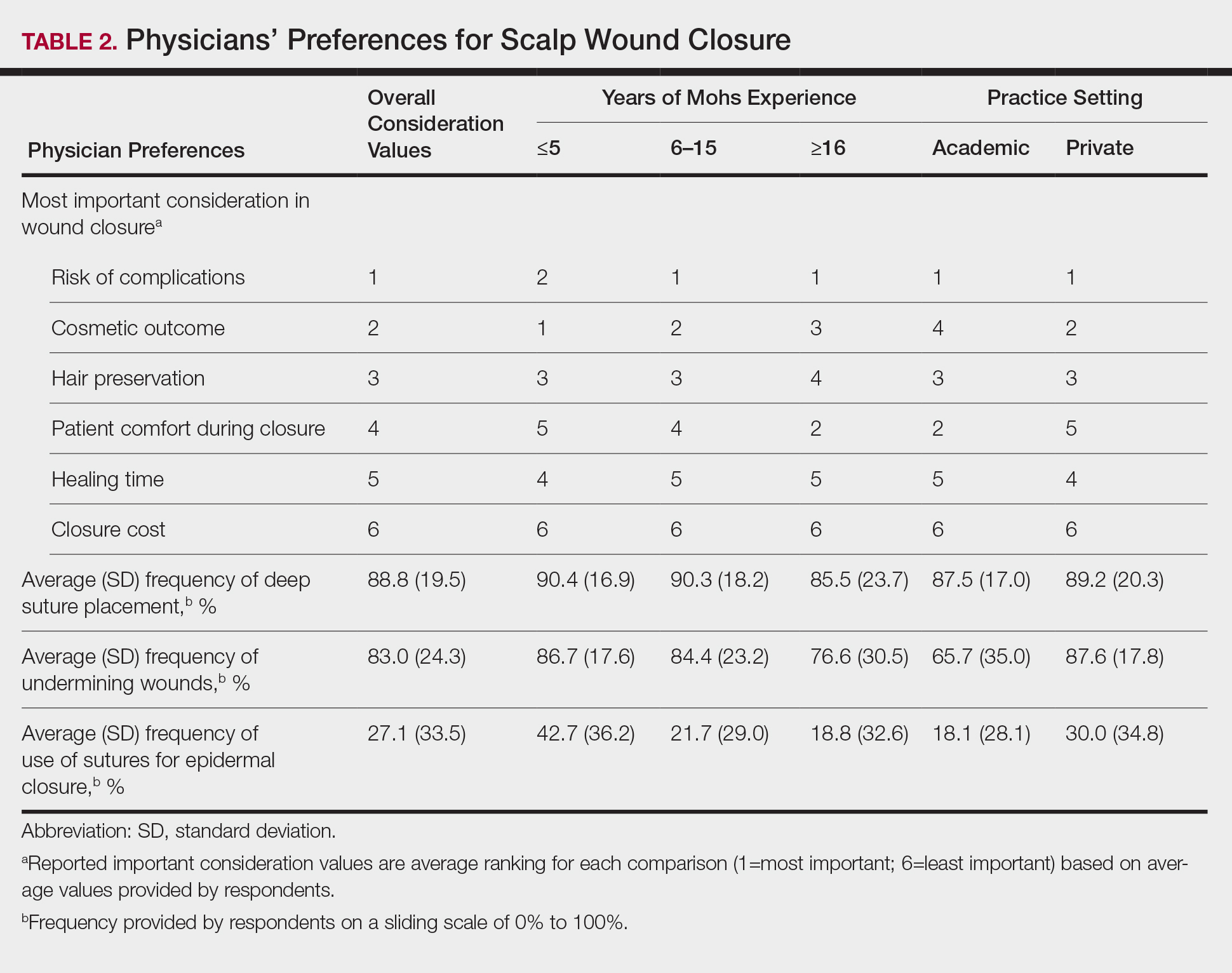

Clinical and economic factors that were most important during wound closure were ranked (beginning with most important) as the following: risk of complications, cosmetic outcome, hair preservation, patient comfort during closure, healing time, and closure cost. In all demographic cases, risk of complications was ranked 1 or 2 (1=most important; 6=least important) overall; cost was the least important factor overall (Table 2).

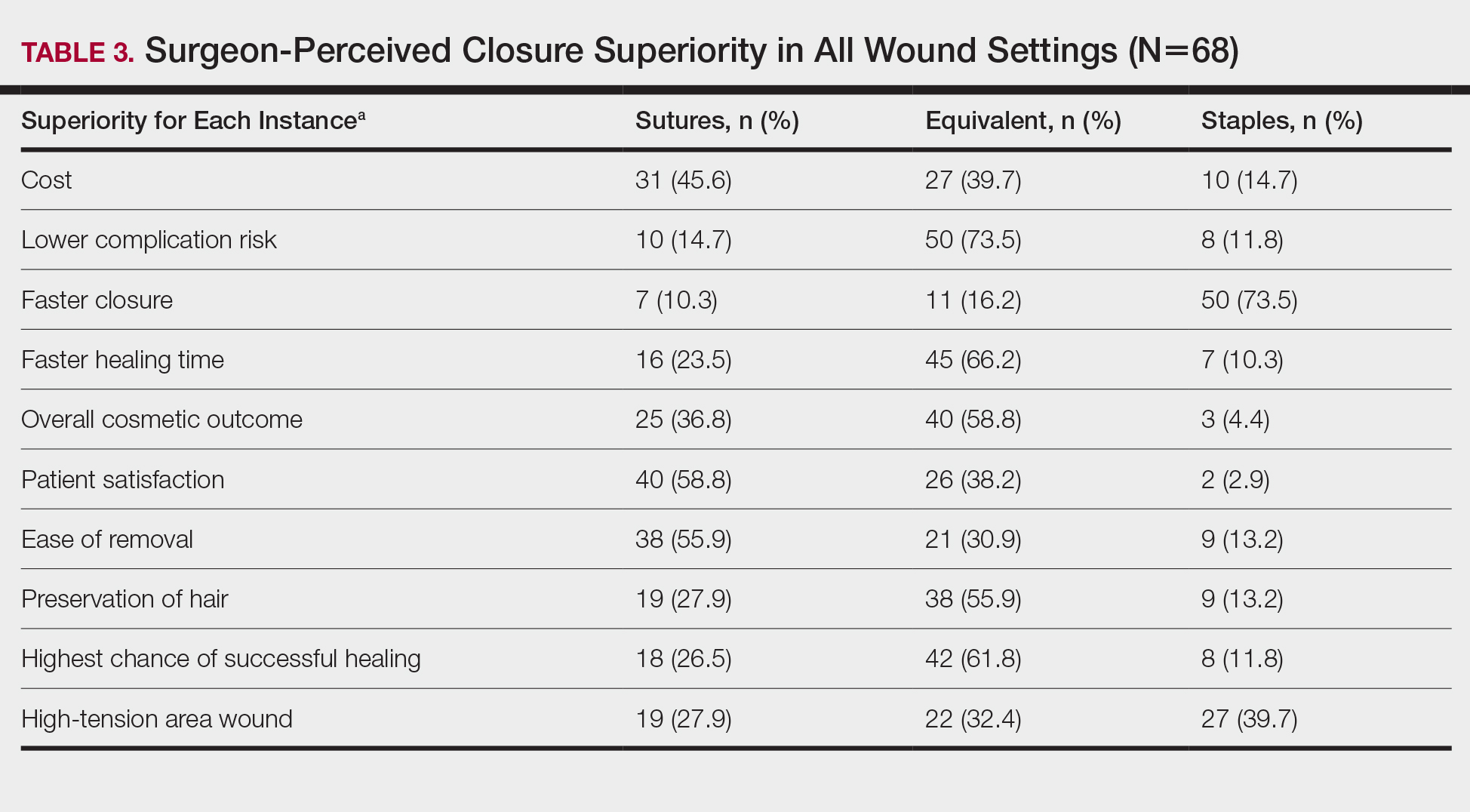

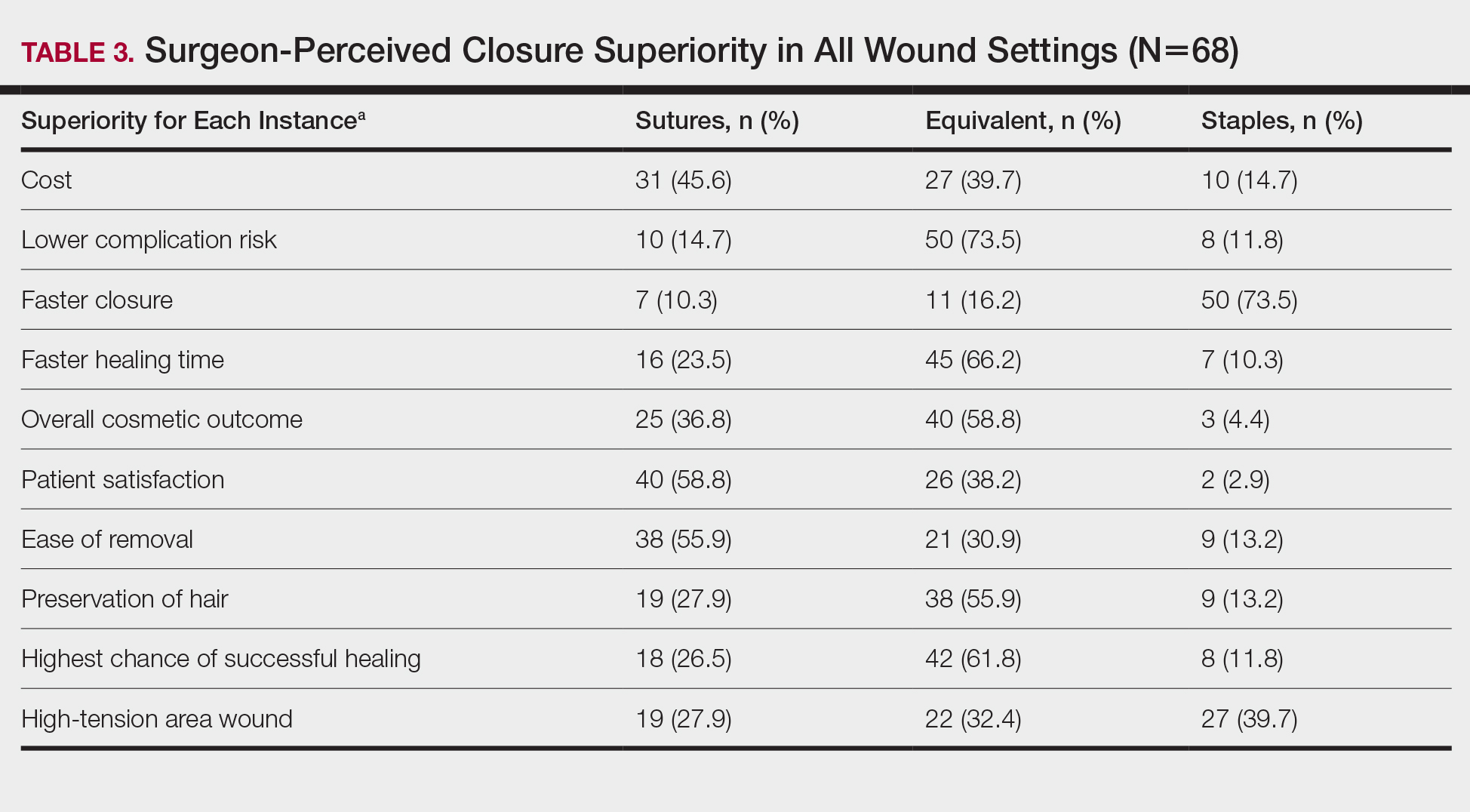

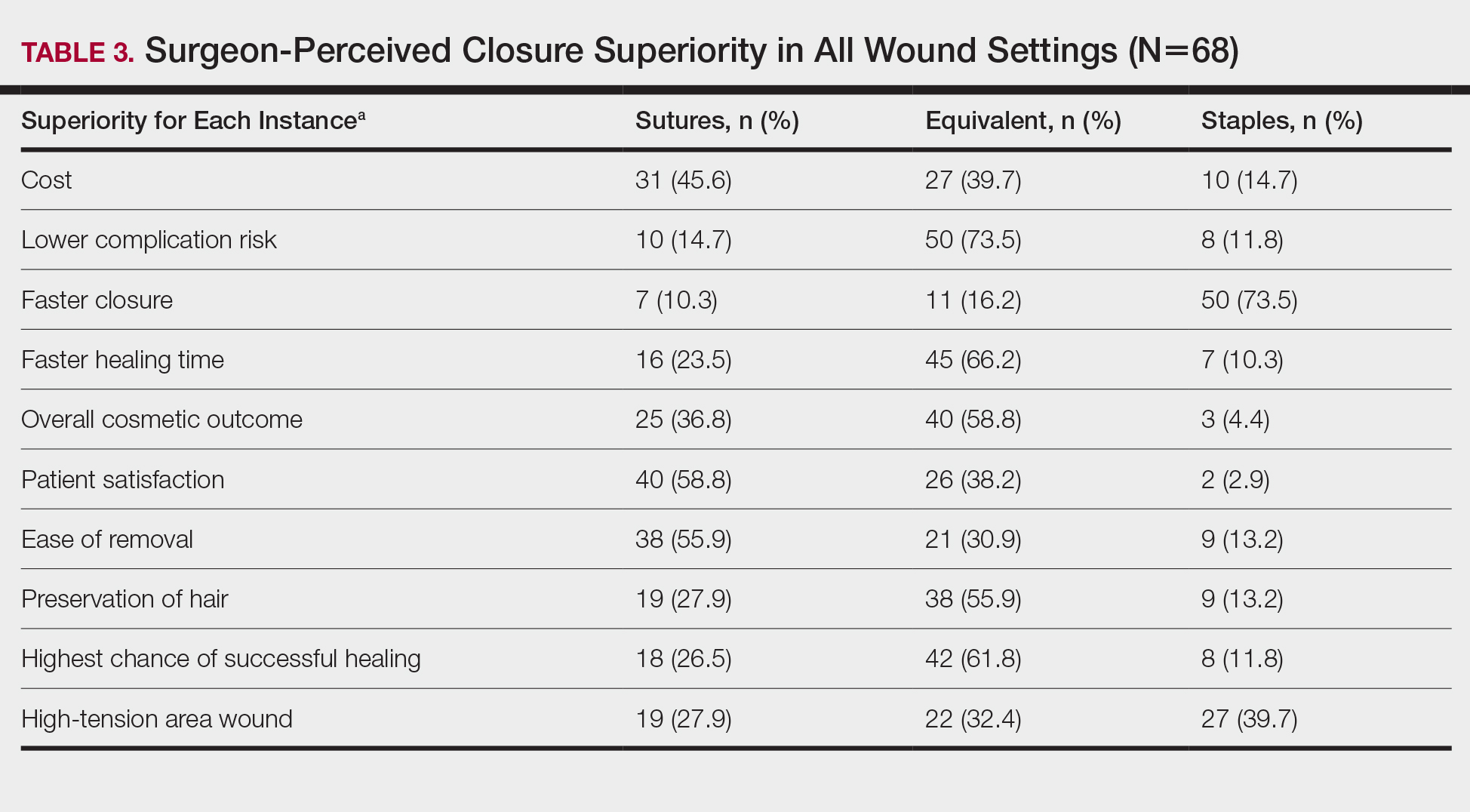

Surgeons perceived staples to be superior for speed of closure and for closing wounds in high-tension areas, whereas sutures were perceived as superior when considering cost of closure and ease of removal (Table 3). Successful healing rate, healing time, hair preservation, overall cosmetic outcome, and lower risk of complications were viewed as equivalent when comparing staples and sutures.

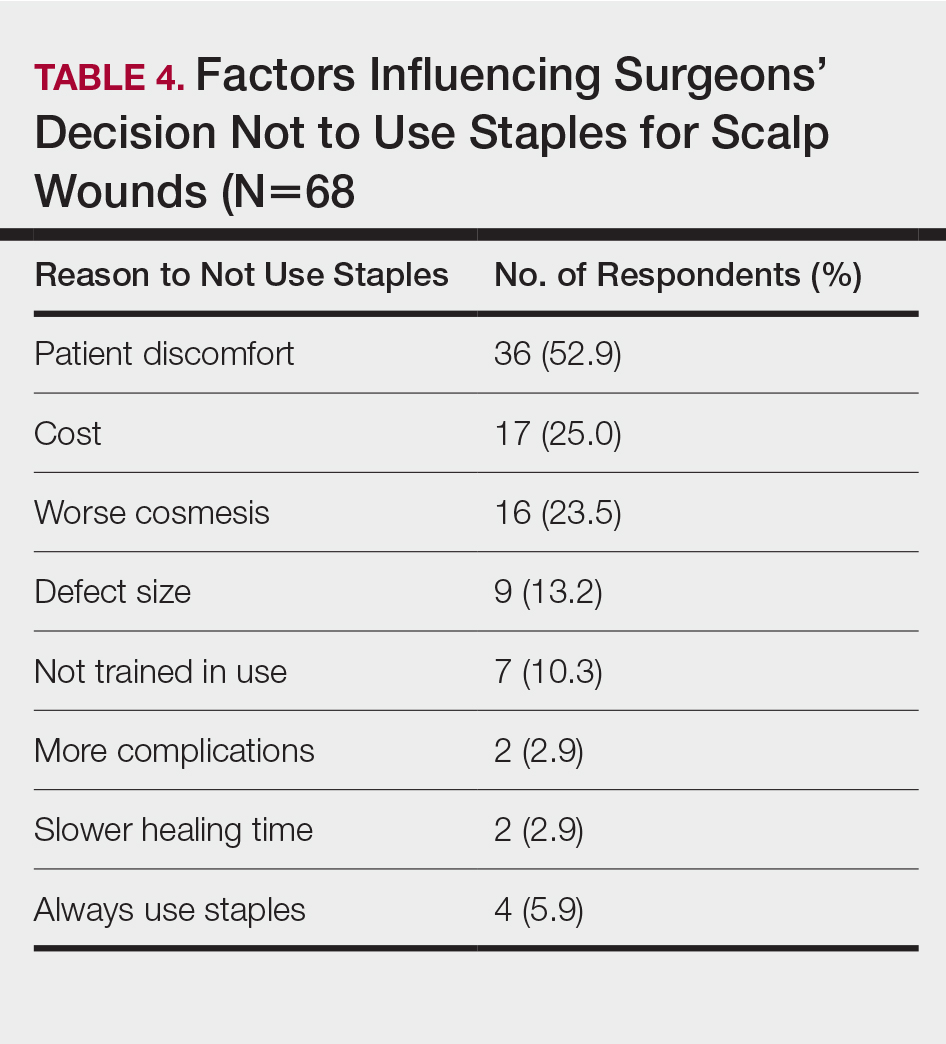

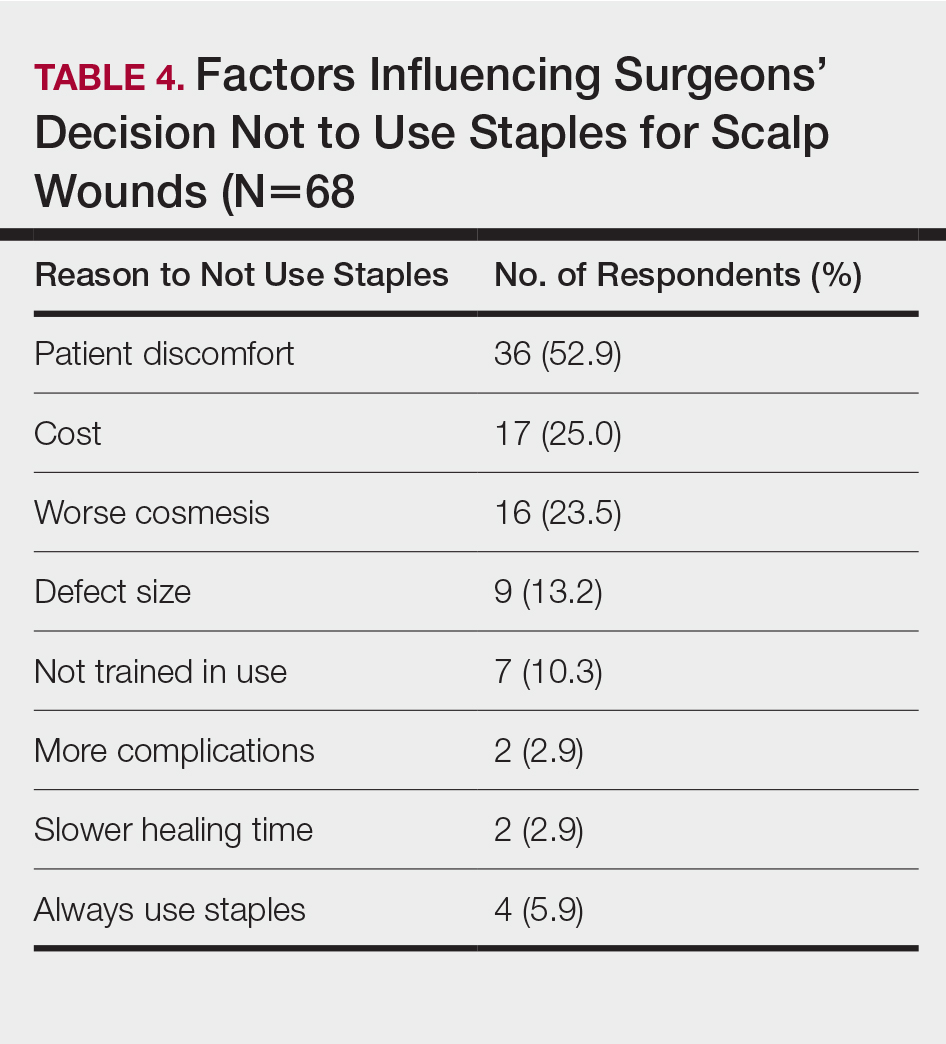

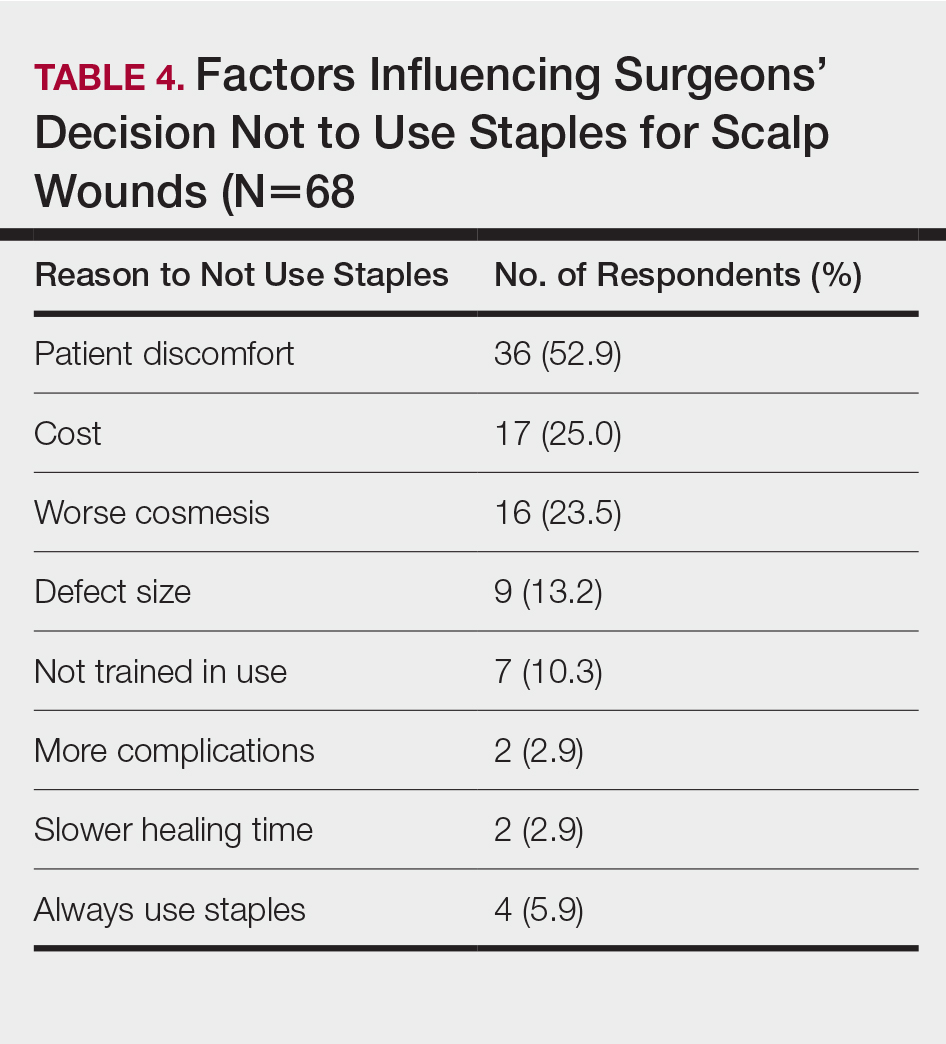

In cases in which surgeons did not use staples for closure, the most important factors for opting to not use them were patient discomfort (52.9% [n=36]), cost (25.0% [n=17]), and worse overall cosmetic outcome (23.5% [n=16])(Table 4). The most frequent locations outside of scalp wounds that physicians considered the use of staples for closure were the back (19.1% [n=13]), thigh (10.3% [n=7]), and shoulder (8.8% [n=6]).

Comment

Epidermal closure with sutures was reportedly used in an average of only 27.1% of scalp wound cases, with clinical factors such as cosmetic outcome, risk of complications, and closure time seen as either equivalent or inferior to staples. Our data suggest that surgeon closure perceptions generally are in agreement with established head and neck literature within different medical specialties that favor staple closures, particularly in high-tension areas.1 Interestingly, the most common reasons given for not using staples included patient discomfort, cost, and worse cosmetic outcomes, which are unsubstantiated with head and neck comparative studies.2-4

Although cost was the least important variable for determining closure type in our surveyed cohort, it is likely that the overall cost of closure is frequently underestimated. A higher material cost is noted with staples; however, the largest determinant of overall cost remains the surgeon’s time, which is reduced by factors of 10 or more when closing with staples.2,3 This difference—coupled with the unchanged cosmetic outcome and complication rates—makes staples more advantageous for high-tension scalp wounds.4 Moreover, the stapling technique is more reproducible than suturing, which requires more surgical skill and experience.

Limitations of this study include a lack of directly comparable data for staple and suture scalp wound closures. In addition, the small cohort of respondents in this preliminary study can serve to guide future studies.

Conclusion

Scalp wounds during MMS were most frequently closed using staples vs sutures, with the perception that these methods are equivalent in complication risk, cosmetic outcome, and overall patient satisfaction. These results agree with comparative literature for head and neck surgery and assist with establishing an epidemiologic baseline for future studies comparing their use during MMS.

- Ritchie AJ, Rocke LG. Staples versus sutures in the closure of scalp wounds: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Injury. 1989;20:217-218.

- Batra J, Bekal RK, Byadgi S, et al. Comparison of skin staples and standard sutures for closing incisions after head and neck cancer surgery: a double-blind, randomized and prospective study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016;15:243-250.

- Kanegaye JT, Vance CW, Chan L, et al. Comparison of skin stapling devices and standard sutures for pediatric scalp lacerations: a randomized study of cost and time benefits. J Pediatr. 1997;130:808-813.

- Khan ANGA, Dayan PS, Miller S, et al. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171-173.

Limited data exist comparing staples and sutures for scalp closures during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). As a result, the closure method for these scalp wounds is based on surgeon preference without established consensus. The purpose of this study was to survey practicing Mohs surgeons on their scalp wound closure preferences as well as the clinical and economic variables that impact their decisions. Understanding practice habits can guide future trial design, with a goal of creating established criterion for MMS scalp wound closures.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed from April 2019 to June 2019 to fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons using an electronic mailing list from the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). The 10-question survey was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board and the executive committee of the ACMS. Surgeons were asked about their preferred method for scalp wound closure as well as clinical and economic variables that impacted those preferences. Respondents indicated their frequency of using deep sutures, epidermal sutures, and wound undermining on a sliding scale of 0% to 100%. Comparisons were made between practice habits, preferences, and surgeon demographics using t tests. Statistical significance was determined as P<.05.

Results

Sixty-eight ACMS fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons completed the survey. The average age of respondents was 45 years; 69.1% (n=47) of respondents were male, and 76.5% (n=52) practiced in a private setting (Table 1). Regardless of epidermal closure type, deep suture placement was used in an average (standard deviation [SD]) of 88.8% (19.5%) of cases overall, which did not statistically differ between years of Mohs experience or practice setting (Table 2). Wound undermining was performed in an average (SD) of 83.0% (24.3%) of cases overall and was more prevalent in private vs academic settings (87.6% [17.8%] vs 65.7% [35.0%]; P<.01). Epidermal sutures were used in an average (SD) of 27.1% (33.5%) of scalp wound cases overall. Surgeons with less experience (≤5 years) used them more frequently (average [SD], 42.7% [36.2%] of cases) than surgeons with more experience (≥16 years; average [SD], 18.8% [32.6%] of cases; P=.037). There was no significant difference between epidermal suture placement rates and practice setting (average [SD], 18.1% [28.1%] of cases for academic providers vs 30.0% [34.8%] of cases with private providers; P=.210).

Clinical and economic factors that were most important during wound closure were ranked (beginning with most important) as the following: risk of complications, cosmetic outcome, hair preservation, patient comfort during closure, healing time, and closure cost. In all demographic cases, risk of complications was ranked 1 or 2 (1=most important; 6=least important) overall; cost was the least important factor overall (Table 2).

Surgeons perceived staples to be superior for speed of closure and for closing wounds in high-tension areas, whereas sutures were perceived as superior when considering cost of closure and ease of removal (Table 3). Successful healing rate, healing time, hair preservation, overall cosmetic outcome, and lower risk of complications were viewed as equivalent when comparing staples and sutures.

In cases in which surgeons did not use staples for closure, the most important factors for opting to not use them were patient discomfort (52.9% [n=36]), cost (25.0% [n=17]), and worse overall cosmetic outcome (23.5% [n=16])(Table 4). The most frequent locations outside of scalp wounds that physicians considered the use of staples for closure were the back (19.1% [n=13]), thigh (10.3% [n=7]), and shoulder (8.8% [n=6]).

Comment

Epidermal closure with sutures was reportedly used in an average of only 27.1% of scalp wound cases, with clinical factors such as cosmetic outcome, risk of complications, and closure time seen as either equivalent or inferior to staples. Our data suggest that surgeon closure perceptions generally are in agreement with established head and neck literature within different medical specialties that favor staple closures, particularly in high-tension areas.1 Interestingly, the most common reasons given for not using staples included patient discomfort, cost, and worse cosmetic outcomes, which are unsubstantiated with head and neck comparative studies.2-4

Although cost was the least important variable for determining closure type in our surveyed cohort, it is likely that the overall cost of closure is frequently underestimated. A higher material cost is noted with staples; however, the largest determinant of overall cost remains the surgeon’s time, which is reduced by factors of 10 or more when closing with staples.2,3 This difference—coupled with the unchanged cosmetic outcome and complication rates—makes staples more advantageous for high-tension scalp wounds.4 Moreover, the stapling technique is more reproducible than suturing, which requires more surgical skill and experience.

Limitations of this study include a lack of directly comparable data for staple and suture scalp wound closures. In addition, the small cohort of respondents in this preliminary study can serve to guide future studies.

Conclusion

Scalp wounds during MMS were most frequently closed using staples vs sutures, with the perception that these methods are equivalent in complication risk, cosmetic outcome, and overall patient satisfaction. These results agree with comparative literature for head and neck surgery and assist with establishing an epidemiologic baseline for future studies comparing their use during MMS.

Limited data exist comparing staples and sutures for scalp closures during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). As a result, the closure method for these scalp wounds is based on surgeon preference without established consensus. The purpose of this study was to survey practicing Mohs surgeons on their scalp wound closure preferences as well as the clinical and economic variables that impact their decisions. Understanding practice habits can guide future trial design, with a goal of creating established criterion for MMS scalp wound closures.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed from April 2019 to June 2019 to fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons using an electronic mailing list from the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). The 10-question survey was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board and the executive committee of the ACMS. Surgeons were asked about their preferred method for scalp wound closure as well as clinical and economic variables that impacted those preferences. Respondents indicated their frequency of using deep sutures, epidermal sutures, and wound undermining on a sliding scale of 0% to 100%. Comparisons were made between practice habits, preferences, and surgeon demographics using t tests. Statistical significance was determined as P<.05.

Results

Sixty-eight ACMS fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons completed the survey. The average age of respondents was 45 years; 69.1% (n=47) of respondents were male, and 76.5% (n=52) practiced in a private setting (Table 1). Regardless of epidermal closure type, deep suture placement was used in an average (standard deviation [SD]) of 88.8% (19.5%) of cases overall, which did not statistically differ between years of Mohs experience or practice setting (Table 2). Wound undermining was performed in an average (SD) of 83.0% (24.3%) of cases overall and was more prevalent in private vs academic settings (87.6% [17.8%] vs 65.7% [35.0%]; P<.01). Epidermal sutures were used in an average (SD) of 27.1% (33.5%) of scalp wound cases overall. Surgeons with less experience (≤5 years) used them more frequently (average [SD], 42.7% [36.2%] of cases) than surgeons with more experience (≥16 years; average [SD], 18.8% [32.6%] of cases; P=.037). There was no significant difference between epidermal suture placement rates and practice setting (average [SD], 18.1% [28.1%] of cases for academic providers vs 30.0% [34.8%] of cases with private providers; P=.210).

Clinical and economic factors that were most important during wound closure were ranked (beginning with most important) as the following: risk of complications, cosmetic outcome, hair preservation, patient comfort during closure, healing time, and closure cost. In all demographic cases, risk of complications was ranked 1 or 2 (1=most important; 6=least important) overall; cost was the least important factor overall (Table 2).

Surgeons perceived staples to be superior for speed of closure and for closing wounds in high-tension areas, whereas sutures were perceived as superior when considering cost of closure and ease of removal (Table 3). Successful healing rate, healing time, hair preservation, overall cosmetic outcome, and lower risk of complications were viewed as equivalent when comparing staples and sutures.

In cases in which surgeons did not use staples for closure, the most important factors for opting to not use them were patient discomfort (52.9% [n=36]), cost (25.0% [n=17]), and worse overall cosmetic outcome (23.5% [n=16])(Table 4). The most frequent locations outside of scalp wounds that physicians considered the use of staples for closure were the back (19.1% [n=13]), thigh (10.3% [n=7]), and shoulder (8.8% [n=6]).

Comment

Epidermal closure with sutures was reportedly used in an average of only 27.1% of scalp wound cases, with clinical factors such as cosmetic outcome, risk of complications, and closure time seen as either equivalent or inferior to staples. Our data suggest that surgeon closure perceptions generally are in agreement with established head and neck literature within different medical specialties that favor staple closures, particularly in high-tension areas.1 Interestingly, the most common reasons given for not using staples included patient discomfort, cost, and worse cosmetic outcomes, which are unsubstantiated with head and neck comparative studies.2-4

Although cost was the least important variable for determining closure type in our surveyed cohort, it is likely that the overall cost of closure is frequently underestimated. A higher material cost is noted with staples; however, the largest determinant of overall cost remains the surgeon’s time, which is reduced by factors of 10 or more when closing with staples.2,3 This difference—coupled with the unchanged cosmetic outcome and complication rates—makes staples more advantageous for high-tension scalp wounds.4 Moreover, the stapling technique is more reproducible than suturing, which requires more surgical skill and experience.

Limitations of this study include a lack of directly comparable data for staple and suture scalp wound closures. In addition, the small cohort of respondents in this preliminary study can serve to guide future studies.

Conclusion

Scalp wounds during MMS were most frequently closed using staples vs sutures, with the perception that these methods are equivalent in complication risk, cosmetic outcome, and overall patient satisfaction. These results agree with comparative literature for head and neck surgery and assist with establishing an epidemiologic baseline for future studies comparing their use during MMS.

- Ritchie AJ, Rocke LG. Staples versus sutures in the closure of scalp wounds: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Injury. 1989;20:217-218.

- Batra J, Bekal RK, Byadgi S, et al. Comparison of skin staples and standard sutures for closing incisions after head and neck cancer surgery: a double-blind, randomized and prospective study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016;15:243-250.

- Kanegaye JT, Vance CW, Chan L, et al. Comparison of skin stapling devices and standard sutures for pediatric scalp lacerations: a randomized study of cost and time benefits. J Pediatr. 1997;130:808-813.

- Khan ANGA, Dayan PS, Miller S, et al. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171-173.

- Ritchie AJ, Rocke LG. Staples versus sutures in the closure of scalp wounds: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Injury. 1989;20:217-218.

- Batra J, Bekal RK, Byadgi S, et al. Comparison of skin staples and standard sutures for closing incisions after head and neck cancer surgery: a double-blind, randomized and prospective study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016;15:243-250.

- Kanegaye JT, Vance CW, Chan L, et al. Comparison of skin stapling devices and standard sutures for pediatric scalp lacerations: a randomized study of cost and time benefits. J Pediatr. 1997;130:808-813.

- Khan ANGA, Dayan PS, Miller S, et al. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171-173.

Practice Points

- Scalp wounds present a unique challenge for closure during Mohs micrographic surgery due to the scalp's tendency to bleed, limited elasticity, and hair-bearing nature.

- Among fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons, scalp wounds were closed with staples more often than with epidermal sutures.

- Staples and sutures for scalp wounds were perceived to be equivalent in risk of complications, cosmetic outcome, and overall patient satisfaction.

- Compared to epidermal sutures, staples were perceived as advantageous in high-tension areas and for speed of closure.

Z-plasty for Correction of Standing Cutaneous Deformity

Practice Gap

Cutaneous head and neck reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery frequently presents the surgical dilemma of dog-ear formation during wound closure, often necessitating excision of additional tissue to correct the standing cone, which could pose the risk for an undesirable tension vector as well as encroachment upon additional cosmetic units or sensitive anatomic structures such as a free margin. A classic Z-plasty is a transposition flap (by definition, translocation of tissue laterally about a pivot point) that corrects a dog-ear deformity without skin excision by recruiting tissue from the axis of the standing cone and redistributing it along another.

The Technique

A classic Z-plasty is designed with 3 equal limb lengths (<1 cm each) at 60° angles, abutting the pedicle of the rotation or advancement flap. The limbs can extend away from the pedicle of the flap to minimize vascular compromise. In our patient, the theoretical standing cone was located at the lateral aspect of an O to L advancement flap (Figure 1). The 2 identical triangular flaps were elevated (Figure 2A), transposed around the pivot point (Figure 2B), and inset (Figure 3). The standing cone was corrected by redistribution of tissue without excision of additional tissue, resulting in a softer and thinner scar 2 weeks (Figure 4A) and 4 months (Figure 4B) postoperatively.

Practice Implications

This technique can be used to correct cones following primary wound repairs or flaps. The primary advantage of this technique for dog-ear correction is tissue sparing. Disadvantages include more complex surgical planning and longer scar length compared to excisional corrective techniques. Additionally, Z-plasty requires more time to execute compared to simpler techniques.1,2

- Frodel JL, Pawar SS, Wang TD. Z-Plasty. In: Baker SR, ed. Local Flaps in Facial Reconstruction. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2014:317-338.

- Hundeshagen G, Zapata-Sirvent R, Goverman J, et al. Tissue rearrangements: the power of the Z-plasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:805-812.

Practice Gap

Cutaneous head and neck reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery frequently presents the surgical dilemma of dog-ear formation during wound closure, often necessitating excision of additional tissue to correct the standing cone, which could pose the risk for an undesirable tension vector as well as encroachment upon additional cosmetic units or sensitive anatomic structures such as a free margin. A classic Z-plasty is a transposition flap (by definition, translocation of tissue laterally about a pivot point) that corrects a dog-ear deformity without skin excision by recruiting tissue from the axis of the standing cone and redistributing it along another.

The Technique

A classic Z-plasty is designed with 3 equal limb lengths (<1 cm each) at 60° angles, abutting the pedicle of the rotation or advancement flap. The limbs can extend away from the pedicle of the flap to minimize vascular compromise. In our patient, the theoretical standing cone was located at the lateral aspect of an O to L advancement flap (Figure 1). The 2 identical triangular flaps were elevated (Figure 2A), transposed around the pivot point (Figure 2B), and inset (Figure 3). The standing cone was corrected by redistribution of tissue without excision of additional tissue, resulting in a softer and thinner scar 2 weeks (Figure 4A) and 4 months (Figure 4B) postoperatively.

Practice Implications

This technique can be used to correct cones following primary wound repairs or flaps. The primary advantage of this technique for dog-ear correction is tissue sparing. Disadvantages include more complex surgical planning and longer scar length compared to excisional corrective techniques. Additionally, Z-plasty requires more time to execute compared to simpler techniques.1,2

Practice Gap

Cutaneous head and neck reconstruction following Mohs micrographic surgery frequently presents the surgical dilemma of dog-ear formation during wound closure, often necessitating excision of additional tissue to correct the standing cone, which could pose the risk for an undesirable tension vector as well as encroachment upon additional cosmetic units or sensitive anatomic structures such as a free margin. A classic Z-plasty is a transposition flap (by definition, translocation of tissue laterally about a pivot point) that corrects a dog-ear deformity without skin excision by recruiting tissue from the axis of the standing cone and redistributing it along another.

The Technique

A classic Z-plasty is designed with 3 equal limb lengths (<1 cm each) at 60° angles, abutting the pedicle of the rotation or advancement flap. The limbs can extend away from the pedicle of the flap to minimize vascular compromise. In our patient, the theoretical standing cone was located at the lateral aspect of an O to L advancement flap (Figure 1). The 2 identical triangular flaps were elevated (Figure 2A), transposed around the pivot point (Figure 2B), and inset (Figure 3). The standing cone was corrected by redistribution of tissue without excision of additional tissue, resulting in a softer and thinner scar 2 weeks (Figure 4A) and 4 months (Figure 4B) postoperatively.

Practice Implications

This technique can be used to correct cones following primary wound repairs or flaps. The primary advantage of this technique for dog-ear correction is tissue sparing. Disadvantages include more complex surgical planning and longer scar length compared to excisional corrective techniques. Additionally, Z-plasty requires more time to execute compared to simpler techniques.1,2

- Frodel JL, Pawar SS, Wang TD. Z-Plasty. In: Baker SR, ed. Local Flaps in Facial Reconstruction. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2014:317-338.

- Hundeshagen G, Zapata-Sirvent R, Goverman J, et al. Tissue rearrangements: the power of the Z-plasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:805-812.

- Frodel JL, Pawar SS, Wang TD. Z-Plasty. In: Baker SR, ed. Local Flaps in Facial Reconstruction. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2014:317-338.

- Hundeshagen G, Zapata-Sirvent R, Goverman J, et al. Tissue rearrangements: the power of the Z-plasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:805-812.

IV gentamicin improves epidermolysis bullosa

In a pilot study, , Michelle Hao said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Serial skin biopsies and immunofluorescent staining demonstrated the mechanism of benefit: The aminoglycoside promoted creation of new full-length functional collagen fibrils at the dermal-epidermal junction in affected patients, added Ms. Hao, a medical student at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Glycoside-mediated nonsense suppression therapy may provide a novel, low cost, and readily available treatment for RDEB [recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa] patients harboring nonsense mutations,” she declared.

RDEB is a rare, incurable, life-threatening genetic skin disease which manifests as severe skin fragility and widespread blistering. The disease is caused by mutations in a gene coding for collagen type VII alpha 1 (COL7A1), the building block for the anchoring fibrils responsible for dermal-epidermal adherence. Roughly 30% of COL7A1 mutations are nonsense mutations, which result in truncated, nonfunctional collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao and her senior coinvestigators have previously shown that aminoglycoside antibiotics can override nonsense mutations to produce full-length, functioning protein. Indeed, they demonstrated that topical gentamicin in particular induces formation of new collagen type VII and improves wound closure in RDEB patients with nonsense mutations. However, RDEB skin lesions are so widespread that topical therapy becomes impractical. This was the impetus for the phase 1/2 clinical trial of IV gentamicin.

The open-label study included four patients with RDEB with nonsense mutations. All participants received IV gentamicin at 7.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks. Two of the four patients then got additional twice-weekly infusions at the same dose for another 3 months. Skin biopsies were obtained from two prospectively monitored open erosive wound sites and two intact skin sites at baseline and 1 and 3 months after treatment.

The primary endpoint was evidence of new collagen type VII at the dermal-epidermal junction post treatment. At baseline, patients averaged only 2% of the amount present in normal skin. One month post treatment, all four patients showed significant gains in expression of functioning collagen type VII, with levels 30%-130% of what’s present in normal skin. This effect proved durable 3 months post treatment.

At the same visits when biopsies were obtained, participants were assessed regarding wound closure, disease activity as measured using the validated Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), and quality of life as reflected in Skindex-16 scores. All four patients showed improved wound closure at 1 and 3 months post treatment at the monitored sites, as well as better EBDASI and Skindex-16 Symptoms and Skindex-16 Emotion scores, Ms. Hao continued.

Safety assessments revealed no evidence of oto- or nephrotoxicity in the gentamicin-treated patients. And no one developed autoantibodies to collagen type VII in skin or sera in response to the aminoglycoside-induced creation of new collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao said preliminary analysis of the study data suggests that the more convenient schedule of twice-weekly IV gentamicin was as effective with regard to wound closure as daily infusion therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the EB Research Partnership, and the EB Research Foundation.

In a pilot study, , Michelle Hao said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Serial skin biopsies and immunofluorescent staining demonstrated the mechanism of benefit: The aminoglycoside promoted creation of new full-length functional collagen fibrils at the dermal-epidermal junction in affected patients, added Ms. Hao, a medical student at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Glycoside-mediated nonsense suppression therapy may provide a novel, low cost, and readily available treatment for RDEB [recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa] patients harboring nonsense mutations,” she declared.

RDEB is a rare, incurable, life-threatening genetic skin disease which manifests as severe skin fragility and widespread blistering. The disease is caused by mutations in a gene coding for collagen type VII alpha 1 (COL7A1), the building block for the anchoring fibrils responsible for dermal-epidermal adherence. Roughly 30% of COL7A1 mutations are nonsense mutations, which result in truncated, nonfunctional collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao and her senior coinvestigators have previously shown that aminoglycoside antibiotics can override nonsense mutations to produce full-length, functioning protein. Indeed, they demonstrated that topical gentamicin in particular induces formation of new collagen type VII and improves wound closure in RDEB patients with nonsense mutations. However, RDEB skin lesions are so widespread that topical therapy becomes impractical. This was the impetus for the phase 1/2 clinical trial of IV gentamicin.

The open-label study included four patients with RDEB with nonsense mutations. All participants received IV gentamicin at 7.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks. Two of the four patients then got additional twice-weekly infusions at the same dose for another 3 months. Skin biopsies were obtained from two prospectively monitored open erosive wound sites and two intact skin sites at baseline and 1 and 3 months after treatment.

The primary endpoint was evidence of new collagen type VII at the dermal-epidermal junction post treatment. At baseline, patients averaged only 2% of the amount present in normal skin. One month post treatment, all four patients showed significant gains in expression of functioning collagen type VII, with levels 30%-130% of what’s present in normal skin. This effect proved durable 3 months post treatment.

At the same visits when biopsies were obtained, participants were assessed regarding wound closure, disease activity as measured using the validated Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), and quality of life as reflected in Skindex-16 scores. All four patients showed improved wound closure at 1 and 3 months post treatment at the monitored sites, as well as better EBDASI and Skindex-16 Symptoms and Skindex-16 Emotion scores, Ms. Hao continued.

Safety assessments revealed no evidence of oto- or nephrotoxicity in the gentamicin-treated patients. And no one developed autoantibodies to collagen type VII in skin or sera in response to the aminoglycoside-induced creation of new collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao said preliminary analysis of the study data suggests that the more convenient schedule of twice-weekly IV gentamicin was as effective with regard to wound closure as daily infusion therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the EB Research Partnership, and the EB Research Foundation.

In a pilot study, , Michelle Hao said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Serial skin biopsies and immunofluorescent staining demonstrated the mechanism of benefit: The aminoglycoside promoted creation of new full-length functional collagen fibrils at the dermal-epidermal junction in affected patients, added Ms. Hao, a medical student at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Glycoside-mediated nonsense suppression therapy may provide a novel, low cost, and readily available treatment for RDEB [recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa] patients harboring nonsense mutations,” she declared.

RDEB is a rare, incurable, life-threatening genetic skin disease which manifests as severe skin fragility and widespread blistering. The disease is caused by mutations in a gene coding for collagen type VII alpha 1 (COL7A1), the building block for the anchoring fibrils responsible for dermal-epidermal adherence. Roughly 30% of COL7A1 mutations are nonsense mutations, which result in truncated, nonfunctional collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao and her senior coinvestigators have previously shown that aminoglycoside antibiotics can override nonsense mutations to produce full-length, functioning protein. Indeed, they demonstrated that topical gentamicin in particular induces formation of new collagen type VII and improves wound closure in RDEB patients with nonsense mutations. However, RDEB skin lesions are so widespread that topical therapy becomes impractical. This was the impetus for the phase 1/2 clinical trial of IV gentamicin.

The open-label study included four patients with RDEB with nonsense mutations. All participants received IV gentamicin at 7.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks. Two of the four patients then got additional twice-weekly infusions at the same dose for another 3 months. Skin biopsies were obtained from two prospectively monitored open erosive wound sites and two intact skin sites at baseline and 1 and 3 months after treatment.

The primary endpoint was evidence of new collagen type VII at the dermal-epidermal junction post treatment. At baseline, patients averaged only 2% of the amount present in normal skin. One month post treatment, all four patients showed significant gains in expression of functioning collagen type VII, with levels 30%-130% of what’s present in normal skin. This effect proved durable 3 months post treatment.

At the same visits when biopsies were obtained, participants were assessed regarding wound closure, disease activity as measured using the validated Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), and quality of life as reflected in Skindex-16 scores. All four patients showed improved wound closure at 1 and 3 months post treatment at the monitored sites, as well as better EBDASI and Skindex-16 Symptoms and Skindex-16 Emotion scores, Ms. Hao continued.

Safety assessments revealed no evidence of oto- or nephrotoxicity in the gentamicin-treated patients. And no one developed autoantibodies to collagen type VII in skin or sera in response to the aminoglycoside-induced creation of new collagen type VII.

Ms. Hao said preliminary analysis of the study data suggests that the more convenient schedule of twice-weekly IV gentamicin was as effective with regard to wound closure as daily infusion therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the EB Research Partnership, and the EB Research Foundation.

FROM AAD 2020

What’s Eating You? Megalopyge opercularis

Lepidoptera is the second largest order of the class Insecta and comprises approximately 160,000 species of butterflies and moths classified among approximately 124 families and subfamilies. Venomous properties have been identified in 12 of these families, posing a serious threat to human health. 1

The clinical manifestations from Lepidoptera envenomation can range from general systemic symptoms such as fever and abdominal distress; to more complex focal affections including hemorrhage, ophthalmologic lesions, and irritation of the respiratory tracts; to less severe reactions of the skin, which are the most common presentation.1

Terminology

Lepidopterism is the term used to address a clinical spectrum of systemic manifestations from direct contact with venomous butterflies or moths and/or their products.2 Conversely, erucism is a term used to describe localized cutaneous reactions after direct contact with toxins from caterpillars.

Lepidopterism is derived from the Greek roots lepis, meaning scale, and pteron, meaning wing. The term erucism stems from the Latin word eruca, which means larva.2

Ideally, lepidopterism should refer solely to reactions from butterflies and moths—adult forms of insects with scaly wings—while erucism should refer to reactions from contact with caterpillars—the larval form of butterflies and moths.

In common use, lepidopterism can describe any reaction from caterpillars, moths, or adult butterflies, as well as any case of Lepidoptera exposure with only systemic manifestations, regardless of cutaneous findings. Concurrently, erucism has been defined as either any reaction from caterpillars or any skin reaction from contact with caterpillars or moths.2

Because caterpillars are the larval form of butterflies and moths, caterpillar-associated skin reactions also have been conveniently denominated caterpillar dermatitis.1 Henceforth in this article, both terms erucism and caterpillar dermatitis are used interchangeably.

Caterpillar Envenomation

Caterpillars cause the vast majority of adverse events from lepidopteran exposures.2 Envenomation by caterpillars might stand as the world’s most common envenomation given the larvae proximity to humans.3 Although involvement of internal organs (eg, renal failure), cerebral hemorrhage, and joint lesions can occur, skin manifestations are more predominant with the majority of species. Initial localized pain, edema, and erythema usually are present at the site of direct contact and subsequently progress toward maculopapular to bullous lesions, erosions, petechiae, necrosis, and ulceration depending on the offending species.1,4

Megalopyge opercularis

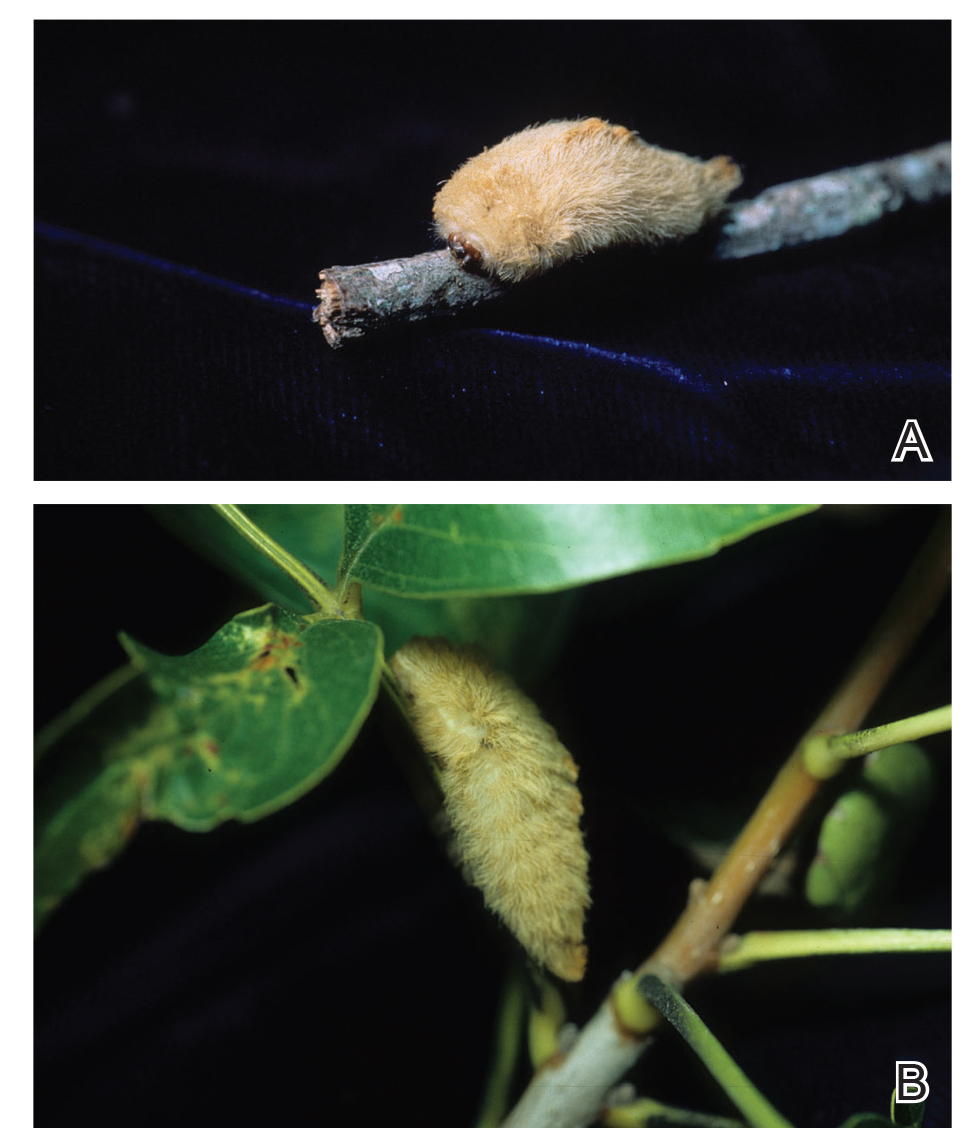

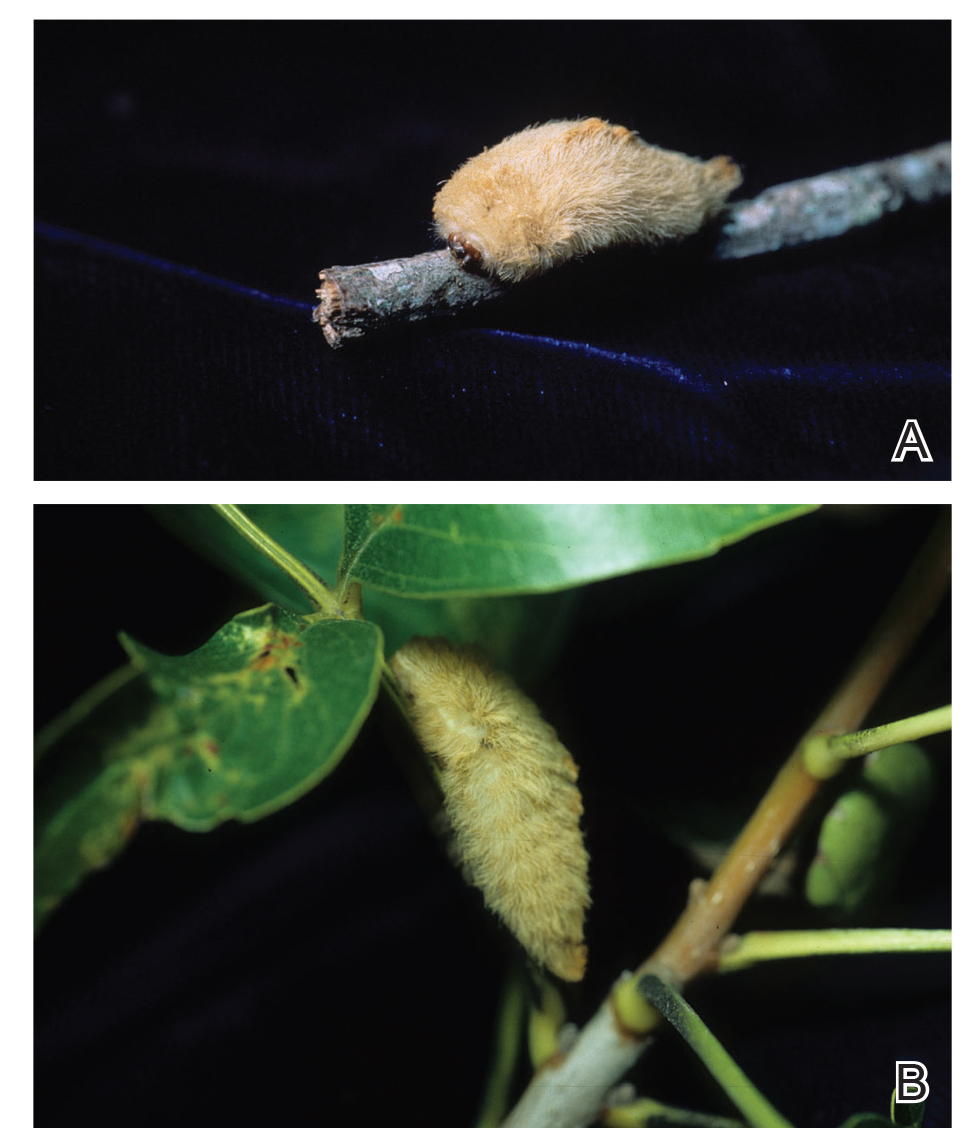

In the United States, more than 50 species of caterpillars have been identified as poisonous or venomous.5 Megalopyge opercularis (Figure 1), the larval form of the flannel moth, is an important cause of caterpillar-associated dermatitis in the southern United States.6,7 Megalopyge opercularis also is commonly known as the puss caterpillar, opossum bug, wooly slug, el perrito, tree asp, or Italian asp.6 This lepidopteran insect is mainly found in the southeastern and southcentral United States, with noted particular abundance in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida.6,8 The puss caterpillar has 2 generations per year; the first develops during the months of June to July, and the second develops from September to October, carrying seasonal health hazards.6,8

Megalopyge opercularis is tapered at the ends and can measure 2.5 to 3.5×1 cm at maturity. It is covered by silky, long-streaked, wavy hairs that may appear single colored or as a mix of colors—from white to gray to brown—forming a mid-dorsal crest.6 Beneath this furry coat, rows of short sharp spines are hidden. Upon contact with the human skin, these spines will break and discharge venom.1,6,8 Toxins contained within the hollow spines are thought to be produced by specialized basal cells, but there still is little knowledge about the dynamics and composition of the venom.1

Clinical Manifestations

The severity of the reaction depends on the caterpillar’s size and the extent of contact.1,4 Contact with M opercularis instantly presents with a throbbing or burning pain that may be followed by localized erythema and rash.1,6 A characteristic gridlike pattern of erythematous macules develops, reflecting each site of puncture from the insect’s spines (Figure 2).8,9 Skin lesions can progress from erythematous macules to hemorrhagic vesicles or pustules, usually self-resolving after a few days. The reaction also can present with radiating pain to regional lymph nodes and numbness of the affected area.1,6,8 Moreover, some patients may report urticaria and pruritus.9

Envenomation by a puss caterpillar also can present with systemic manifestations including fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, shocklike symptoms, and seizures.1,6,7 Anaphylactic reaction is rare but also can present.7 Uncommon cases have been reported with severe abdominal pain and muscle spasm mimicking acute appendicitis and latrodectism, respectively.7,9

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of M opercularis envenomation is made clinically based on the morphology of the skin lesions and a history of probable exposure. Coexistent leukocytosis is likely, but laboratory testing is not warranted, as it is both nonspecific and insensitive.9

Management/Treatment

The most commonly reported immediate approaches to treatment involve attempts to remove the spines from the skin with tape (stripping), application of ice packs over the affected area, oral antihistamines, topical and intralesional anesthetics, regional nerve block, and oral analgesics.6,9 There have been several cases detailing the successful use of parenteral calcium gluconate,5,7 and diazepam has been used to treat severe muscle spasms. Anaphylactic reactions should be managed in a controlled monitored setting with subcutaneous epinephrine.7 Despite their common use, some data suggest that ice packs and mid- to high-potency topical steroids are ineffective.9

Incidence

From 2001 to 2005, a mean average of 94,552 annual cases of animal bites and stings were reported to poison control centers in the United States, of which 2094 were linked to caterpillars in this 5-year period.10 There were 3484 M opercularis caterpillar stings reported to the Texas Poison Center Network from 2000 to 2016.5,6 Given their ability to sting throughout their life cycle, thousands of M opercularis caterpillar stings can occur each year.1,6 Existing literature on M opercularis caterpillar stings mainly involves case reports with affections of the skin and oral mucosa, self-reported envenomation, and case studies.5,6,8

Although multiple health concerns associated with caterpillar envenomation have been reported worldwide, the lack of official epidemiologic reports highly suggests that this problem remains underestimated. There also may be many unreported cases because certain reactions are mild or self-limited and can even go unnoticed.11 Nonetheless, there is an evident rise of cases reported in the United States. According to the 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers, there were 2815 case mentions from caterpillar envenomation.12

In 1921 and 1952, some public schools in Texas were temporarily closed due to outbreaks of puss caterpillar–associated dermatitis.8 Similar outbreaks also have been reported in South Carolina, Virginia, and Oklahoma.9 Emerging data suggest that plant oil products and the pesticide cypermethrin may be helpful in controlling local infestations of the puss caterpillar.8

- Villas-Boas IM, Bonfa G, Tambourgi DV. Venomous caterpillars: from inoculation apparatus to venom composition and envenomation. Toxicon. 2018;153:39-52.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1-10; quiz 11-12.

- Haddad Junior V, Amorim PC, Haddad Junior WT, et al. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:650-657.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.e1-331.e14; quiz 345.

- Pappano DA, Trout Fryxell R, Warren M. Oral mucosal envenomation of an infant by a puss caterpillar. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:424-426.

- Forrester MB. Megalopyge opercularis caterpillar stings reported to Texas poison centers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29:215-220.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:13-28; quiz 29-30.

- Eagleman DM. Envenomation by the asp caterpillar (Megalopyge opercularis). Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46:201-205.

- Greene SC, Carey JM. Puss caterpillar envenomation: erucism mimicking appendicitis in a young child [published online May 23, 2018]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001514.

- Langley RL. Animal bites and stings reported by United States Poison Control Centers, 2001-2005. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:7-14.

- Seldeslachts A, Peigneur S, Tytgat J. Caterpillar venom: a health hazard of the 21st century [published online May 30, 2020]. Biomedicines. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8060143.

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1220-1413.

Lepidoptera is the second largest order of the class Insecta and comprises approximately 160,000 species of butterflies and moths classified among approximately 124 families and subfamilies. Venomous properties have been identified in 12 of these families, posing a serious threat to human health. 1

The clinical manifestations from Lepidoptera envenomation can range from general systemic symptoms such as fever and abdominal distress; to more complex focal affections including hemorrhage, ophthalmologic lesions, and irritation of the respiratory tracts; to less severe reactions of the skin, which are the most common presentation.1

Terminology

Lepidopterism is the term used to address a clinical spectrum of systemic manifestations from direct contact with venomous butterflies or moths and/or their products.2 Conversely, erucism is a term used to describe localized cutaneous reactions after direct contact with toxins from caterpillars.

Lepidopterism is derived from the Greek roots lepis, meaning scale, and pteron, meaning wing. The term erucism stems from the Latin word eruca, which means larva.2

Ideally, lepidopterism should refer solely to reactions from butterflies and moths—adult forms of insects with scaly wings—while erucism should refer to reactions from contact with caterpillars—the larval form of butterflies and moths.

In common use, lepidopterism can describe any reaction from caterpillars, moths, or adult butterflies, as well as any case of Lepidoptera exposure with only systemic manifestations, regardless of cutaneous findings. Concurrently, erucism has been defined as either any reaction from caterpillars or any skin reaction from contact with caterpillars or moths.2

Because caterpillars are the larval form of butterflies and moths, caterpillar-associated skin reactions also have been conveniently denominated caterpillar dermatitis.1 Henceforth in this article, both terms erucism and caterpillar dermatitis are used interchangeably.

Caterpillar Envenomation

Caterpillars cause the vast majority of adverse events from lepidopteran exposures.2 Envenomation by caterpillars might stand as the world’s most common envenomation given the larvae proximity to humans.3 Although involvement of internal organs (eg, renal failure), cerebral hemorrhage, and joint lesions can occur, skin manifestations are more predominant with the majority of species. Initial localized pain, edema, and erythema usually are present at the site of direct contact and subsequently progress toward maculopapular to bullous lesions, erosions, petechiae, necrosis, and ulceration depending on the offending species.1,4

Megalopyge opercularis

In the United States, more than 50 species of caterpillars have been identified as poisonous or venomous.5 Megalopyge opercularis (Figure 1), the larval form of the flannel moth, is an important cause of caterpillar-associated dermatitis in the southern United States.6,7 Megalopyge opercularis also is commonly known as the puss caterpillar, opossum bug, wooly slug, el perrito, tree asp, or Italian asp.6 This lepidopteran insect is mainly found in the southeastern and southcentral United States, with noted particular abundance in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida.6,8 The puss caterpillar has 2 generations per year; the first develops during the months of June to July, and the second develops from September to October, carrying seasonal health hazards.6,8

Megalopyge opercularis is tapered at the ends and can measure 2.5 to 3.5×1 cm at maturity. It is covered by silky, long-streaked, wavy hairs that may appear single colored or as a mix of colors—from white to gray to brown—forming a mid-dorsal crest.6 Beneath this furry coat, rows of short sharp spines are hidden. Upon contact with the human skin, these spines will break and discharge venom.1,6,8 Toxins contained within the hollow spines are thought to be produced by specialized basal cells, but there still is little knowledge about the dynamics and composition of the venom.1

Clinical Manifestations

The severity of the reaction depends on the caterpillar’s size and the extent of contact.1,4 Contact with M opercularis instantly presents with a throbbing or burning pain that may be followed by localized erythema and rash.1,6 A characteristic gridlike pattern of erythematous macules develops, reflecting each site of puncture from the insect’s spines (Figure 2).8,9 Skin lesions can progress from erythematous macules to hemorrhagic vesicles or pustules, usually self-resolving after a few days. The reaction also can present with radiating pain to regional lymph nodes and numbness of the affected area.1,6,8 Moreover, some patients may report urticaria and pruritus.9

Envenomation by a puss caterpillar also can present with systemic manifestations including fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, shocklike symptoms, and seizures.1,6,7 Anaphylactic reaction is rare but also can present.7 Uncommon cases have been reported with severe abdominal pain and muscle spasm mimicking acute appendicitis and latrodectism, respectively.7,9

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of M opercularis envenomation is made clinically based on the morphology of the skin lesions and a history of probable exposure. Coexistent leukocytosis is likely, but laboratory testing is not warranted, as it is both nonspecific and insensitive.9

Management/Treatment

The most commonly reported immediate approaches to treatment involve attempts to remove the spines from the skin with tape (stripping), application of ice packs over the affected area, oral antihistamines, topical and intralesional anesthetics, regional nerve block, and oral analgesics.6,9 There have been several cases detailing the successful use of parenteral calcium gluconate,5,7 and diazepam has been used to treat severe muscle spasms. Anaphylactic reactions should be managed in a controlled monitored setting with subcutaneous epinephrine.7 Despite their common use, some data suggest that ice packs and mid- to high-potency topical steroids are ineffective.9

Incidence

From 2001 to 2005, a mean average of 94,552 annual cases of animal bites and stings were reported to poison control centers in the United States, of which 2094 were linked to caterpillars in this 5-year period.10 There were 3484 M opercularis caterpillar stings reported to the Texas Poison Center Network from 2000 to 2016.5,6 Given their ability to sting throughout their life cycle, thousands of M opercularis caterpillar stings can occur each year.1,6 Existing literature on M opercularis caterpillar stings mainly involves case reports with affections of the skin and oral mucosa, self-reported envenomation, and case studies.5,6,8

Although multiple health concerns associated with caterpillar envenomation have been reported worldwide, the lack of official epidemiologic reports highly suggests that this problem remains underestimated. There also may be many unreported cases because certain reactions are mild or self-limited and can even go unnoticed.11 Nonetheless, there is an evident rise of cases reported in the United States. According to the 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers, there were 2815 case mentions from caterpillar envenomation.12

In 1921 and 1952, some public schools in Texas were temporarily closed due to outbreaks of puss caterpillar–associated dermatitis.8 Similar outbreaks also have been reported in South Carolina, Virginia, and Oklahoma.9 Emerging data suggest that plant oil products and the pesticide cypermethrin may be helpful in controlling local infestations of the puss caterpillar.8

Lepidoptera is the second largest order of the class Insecta and comprises approximately 160,000 species of butterflies and moths classified among approximately 124 families and subfamilies. Venomous properties have been identified in 12 of these families, posing a serious threat to human health. 1

The clinical manifestations from Lepidoptera envenomation can range from general systemic symptoms such as fever and abdominal distress; to more complex focal affections including hemorrhage, ophthalmologic lesions, and irritation of the respiratory tracts; to less severe reactions of the skin, which are the most common presentation.1

Terminology

Lepidopterism is the term used to address a clinical spectrum of systemic manifestations from direct contact with venomous butterflies or moths and/or their products.2 Conversely, erucism is a term used to describe localized cutaneous reactions after direct contact with toxins from caterpillars.

Lepidopterism is derived from the Greek roots lepis, meaning scale, and pteron, meaning wing. The term erucism stems from the Latin word eruca, which means larva.2

Ideally, lepidopterism should refer solely to reactions from butterflies and moths—adult forms of insects with scaly wings—while erucism should refer to reactions from contact with caterpillars—the larval form of butterflies and moths.

In common use, lepidopterism can describe any reaction from caterpillars, moths, or adult butterflies, as well as any case of Lepidoptera exposure with only systemic manifestations, regardless of cutaneous findings. Concurrently, erucism has been defined as either any reaction from caterpillars or any skin reaction from contact with caterpillars or moths.2

Because caterpillars are the larval form of butterflies and moths, caterpillar-associated skin reactions also have been conveniently denominated caterpillar dermatitis.1 Henceforth in this article, both terms erucism and caterpillar dermatitis are used interchangeably.

Caterpillar Envenomation

Caterpillars cause the vast majority of adverse events from lepidopteran exposures.2 Envenomation by caterpillars might stand as the world’s most common envenomation given the larvae proximity to humans.3 Although involvement of internal organs (eg, renal failure), cerebral hemorrhage, and joint lesions can occur, skin manifestations are more predominant with the majority of species. Initial localized pain, edema, and erythema usually are present at the site of direct contact and subsequently progress toward maculopapular to bullous lesions, erosions, petechiae, necrosis, and ulceration depending on the offending species.1,4

Megalopyge opercularis

In the United States, more than 50 species of caterpillars have been identified as poisonous or venomous.5 Megalopyge opercularis (Figure 1), the larval form of the flannel moth, is an important cause of caterpillar-associated dermatitis in the southern United States.6,7 Megalopyge opercularis also is commonly known as the puss caterpillar, opossum bug, wooly slug, el perrito, tree asp, or Italian asp.6 This lepidopteran insect is mainly found in the southeastern and southcentral United States, with noted particular abundance in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida.6,8 The puss caterpillar has 2 generations per year; the first develops during the months of June to July, and the second develops from September to October, carrying seasonal health hazards.6,8

Megalopyge opercularis is tapered at the ends and can measure 2.5 to 3.5×1 cm at maturity. It is covered by silky, long-streaked, wavy hairs that may appear single colored or as a mix of colors—from white to gray to brown—forming a mid-dorsal crest.6 Beneath this furry coat, rows of short sharp spines are hidden. Upon contact with the human skin, these spines will break and discharge venom.1,6,8 Toxins contained within the hollow spines are thought to be produced by specialized basal cells, but there still is little knowledge about the dynamics and composition of the venom.1

Clinical Manifestations

The severity of the reaction depends on the caterpillar’s size and the extent of contact.1,4 Contact with M opercularis instantly presents with a throbbing or burning pain that may be followed by localized erythema and rash.1,6 A characteristic gridlike pattern of erythematous macules develops, reflecting each site of puncture from the insect’s spines (Figure 2).8,9 Skin lesions can progress from erythematous macules to hemorrhagic vesicles or pustules, usually self-resolving after a few days. The reaction also can present with radiating pain to regional lymph nodes and numbness of the affected area.1,6,8 Moreover, some patients may report urticaria and pruritus.9

Envenomation by a puss caterpillar also can present with systemic manifestations including fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, shocklike symptoms, and seizures.1,6,7 Anaphylactic reaction is rare but also can present.7 Uncommon cases have been reported with severe abdominal pain and muscle spasm mimicking acute appendicitis and latrodectism, respectively.7,9

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of M opercularis envenomation is made clinically based on the morphology of the skin lesions and a history of probable exposure. Coexistent leukocytosis is likely, but laboratory testing is not warranted, as it is both nonspecific and insensitive.9

Management/Treatment

The most commonly reported immediate approaches to treatment involve attempts to remove the spines from the skin with tape (stripping), application of ice packs over the affected area, oral antihistamines, topical and intralesional anesthetics, regional nerve block, and oral analgesics.6,9 There have been several cases detailing the successful use of parenteral calcium gluconate,5,7 and diazepam has been used to treat severe muscle spasms. Anaphylactic reactions should be managed in a controlled monitored setting with subcutaneous epinephrine.7 Despite their common use, some data suggest that ice packs and mid- to high-potency topical steroids are ineffective.9

Incidence

From 2001 to 2005, a mean average of 94,552 annual cases of animal bites and stings were reported to poison control centers in the United States, of which 2094 were linked to caterpillars in this 5-year period.10 There were 3484 M opercularis caterpillar stings reported to the Texas Poison Center Network from 2000 to 2016.5,6 Given their ability to sting throughout their life cycle, thousands of M opercularis caterpillar stings can occur each year.1,6 Existing literature on M opercularis caterpillar stings mainly involves case reports with affections of the skin and oral mucosa, self-reported envenomation, and case studies.5,6,8

Although multiple health concerns associated with caterpillar envenomation have been reported worldwide, the lack of official epidemiologic reports highly suggests that this problem remains underestimated. There also may be many unreported cases because certain reactions are mild or self-limited and can even go unnoticed.11 Nonetheless, there is an evident rise of cases reported in the United States. According to the 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers, there were 2815 case mentions from caterpillar envenomation.12

In 1921 and 1952, some public schools in Texas were temporarily closed due to outbreaks of puss caterpillar–associated dermatitis.8 Similar outbreaks also have been reported in South Carolina, Virginia, and Oklahoma.9 Emerging data suggest that plant oil products and the pesticide cypermethrin may be helpful in controlling local infestations of the puss caterpillar.8

- Villas-Boas IM, Bonfa G, Tambourgi DV. Venomous caterpillars: from inoculation apparatus to venom composition and envenomation. Toxicon. 2018;153:39-52.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1-10; quiz 11-12.

- Haddad Junior V, Amorim PC, Haddad Junior WT, et al. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:650-657.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.e1-331.e14; quiz 345.

- Pappano DA, Trout Fryxell R, Warren M. Oral mucosal envenomation of an infant by a puss caterpillar. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:424-426.

- Forrester MB. Megalopyge opercularis caterpillar stings reported to Texas poison centers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29:215-220.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:13-28; quiz 29-30.

- Eagleman DM. Envenomation by the asp caterpillar (Megalopyge opercularis). Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46:201-205.

- Greene SC, Carey JM. Puss caterpillar envenomation: erucism mimicking appendicitis in a young child [published online May 23, 2018]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001514.

- Langley RL. Animal bites and stings reported by United States Poison Control Centers, 2001-2005. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:7-14.

- Seldeslachts A, Peigneur S, Tytgat J. Caterpillar venom: a health hazard of the 21st century [published online May 30, 2020]. Biomedicines. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8060143.

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1220-1413.

- Villas-Boas IM, Bonfa G, Tambourgi DV. Venomous caterpillars: from inoculation apparatus to venom composition and envenomation. Toxicon. 2018;153:39-52.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1-10; quiz 11-12.

- Haddad Junior V, Amorim PC, Haddad Junior WT, et al. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:650-657.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.e1-331.e14; quiz 345.

- Pappano DA, Trout Fryxell R, Warren M. Oral mucosal envenomation of an infant by a puss caterpillar. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:424-426.

- Forrester MB. Megalopyge opercularis caterpillar stings reported to Texas poison centers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29:215-220.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:13-28; quiz 29-30.

- Eagleman DM. Envenomation by the asp caterpillar (Megalopyge opercularis). Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46:201-205.

- Greene SC, Carey JM. Puss caterpillar envenomation: erucism mimicking appendicitis in a young child [published online May 23, 2018]. Pediatr Emerg Care. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001514.

- Langley RL. Animal bites and stings reported by United States Poison Control Centers, 2001-2005. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:7-14.

- Seldeslachts A, Peigneur S, Tytgat J. Caterpillar venom: a health hazard of the 21st century [published online May 30, 2020]. Biomedicines. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8060143.

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1220-1413.

Practice Points

- Megalopyge opercularis is the most widely distributed caterpillar species in the Americas, and envenomation by it can occur year-round.

- Skin reactions to M opercularis stings can present as maculopapular dermatitis, eczematous eruptions, or urticarial reactions.

- During the initial presentation, patients experience intense throbbing pain, yet the severity of symptoms depends on the caterpillar’s size and the extent of contact.

- A history of caterpillar exposure helps with diagnosis, and treatment remains empiric.

Sericin, a versatile silk protein, has multiple potential roles in dermatology

Inexpensively obtained as a silk industry by-product, sericin is a glycoprotein found to confer various biologic effects.1 The globular protein sericin has also long been known to exhibit antityrosinase and immunomodulatory activities.2,3 This column focuses on the wide range of emerging and potential applications of sericin in cutaneous treatments.

Protection against solar radiation and photoaging

Studies in mice to evaluate the potential antioxidant and skin-protective effects of sericin by Zhaorigetu et al. in 2003 revealed that, by diminishing oxidative stress, cyclooxygenase-2 protein, and cell proliferation, sericin exerted a photoprotective effect against acute harm and tumor promotion elicited by UVB.4

Using mouse skin models, Dash et al. showed in 2008 that the silk protein sericin derived from the tropical tasar silkworm is a robust antioxidant and photoprotective agent, displaying a capacity to block UVB-induced apoptosis in irradiated (30 mJ/cm2 UVB) human keratinocytes and, as compared with the mulberry silkworm, yielding protection against oxidative stress.5,6

In 2015, Berardesca et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, split-face study over 8 weeks in 40 women (ages 40-70 years) to assess the antiaging effects of topically applied combination therapy including gold silk sericin, niacinamide, and signaline. The investigators observed significant improvements in stratum corneum hydration, barrier function, skin elasticity, and roughness as compared with skin treated with the control formulation. They concluded that this combination formulation featuring gold silk sericin warrants attention in the arsenal for ameliorating signs of aging female facial skin.7

A year earlier, Aramwit and Bang introduced a bacterial nanocellulose gel shown to effectively release silk sericin for facial treatment. Formulated at a pH of 4.5, the bioactive mask exhibited an ultrafine and pure fiber network structure. The authors noted that the gel was less adhesive than the commercially available paper mask, while the silk sericin product displayed greater moisture absorption capacity. In vitro cytotoxicity assessments also revealed that the product is safe for facial treatments.8

Cosmeceutical antioxidant for hyperpigmentation

In 2019, Kumar et al. demonstrated the inhibitory effect of topically applied silk sericin derived from Antheraea assamensis against UV-induced melanogenesis in mouse melanoma. They suggested that the formulation shows promise as a cosmeceutical antioxidant agent designed to address hyperpigmentation.3

The previous year, Aramwit et al. demonstrated using an in vitro model that urea-extracted sericin displays a capacity to inhibit melanogenesis by hindering tyrosinase activity, attenuating inflammation and allergic reactions, and reducing the expression of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor, a marker of melanogenesis regulation, in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2

Potential use as an adjunct psoriasis treatment

A combination of naringin (from Citrus maxima) and sericin (from Bombyx mori) was evaluated in 2019 by Deenonpoe et al. for the treatment of psoriasis. They isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 10 healthy subjects and 10 patients with psoriasis. The combination formulation was much more effective than either compound alone in significantly reducing mRNA expression and the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines in samples from psoriasis patients. The investigators concluded that the down-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines imparted by the naringin/sericin product points toward its possible clinical use as a complementary treatment for psoriasis and other inflammation-mediated conditions.9

Uremic pruritus and burn wounds

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 6-week study in 2012 conducted by Aramwit et al. assessed the use of sericin cream versus a cream base placebo in the treatment of uremic pruritus in 50 hemodialysis patients, 47 of whom completed the study. Significant differences in the creams were identified, with hydration vastly improved in patients using the sericin cream. Significant reductions in pruritus and dyspigmentation were also observed in the treatment group, with an overall quality of life improvement noted in relation to pain score.10

The ensuing year, Aramwit et al. showed that silk sericin promoted wound healing in vitro and, when added to silver sulfadiazine cream and evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, standard-controlled study, demonstrated clinical efficacy in healing burn wounds.11

Wound healing

An expanding body of research suggests the role of sericin in wound healing. In 2007, Aramwit et al. found that sericin, which boasts notable hydrophilic qualities, was effective as a wound-healing agent in rats. The tested sericin cream successfully reduced wound size and wound healing time was substantially shorter than in animals treated with control formula. Treatment for 15 days yielded complete healing, no ulceration, and higher collagen levels, as determined by histologic examination, in comparison with control.12 Other studies using sericin hydrogel as well as a sericin-based nanofibrous matrix with chitosan have demonstrated success in wound healing in mice.13,14

Human studies

In 2018, Napavichayanun et al. reported on the clinical efficacy and safety of bacterial cellulose wound dressings including silk sericin and PHMB as compared with Bactigras (an antiseptic dressing) as a control in split-thickness skin graft donor-site wound treatment. In this single-blinded, randomized, controlled study of 21 patients, pain scores were significantly lower and wound quality higher in the skin treated with the sericin product. The test formulation was protected against infection without inducing adverse effects.15

Previously, a silk sericin–releasing wound dressing introduced in 2014 was found to significantly diminish pain and promote more rapid healing in patients with split-thickness skin graft donor sites as compared with treatment with the Bactigras wound dressing.16

Sericin in tissue repair and as a drug delivery carrier

Sericin is associated with antioxidant and moisturizing properties as well as a mitogenic influence on mammalian cells, with a particular impact on keratinocytes and fibroblasts that render it useful in biomaterials designed for skin tissue repair.17

Wang et al. have cross-linked dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose with silk sericin derived from the B. mori cocoon to develop a film with impressive blood compatibility and cytocompatibility that shows potential for use as a wound dressing, artificial skin, and in tissue engineering.18

Similarly, Liang et al. have been successful in preparing a medical tissue glue incorporating a gelatin, sericin, and carboxymethyl chitosan blend solution, cross-linked with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide. The tissue glue has been found to offer notable biocompatibility and structural traits at low cost.19

Sericin protein also evinces potential as a biocompatible, bioviable carrier for drug delivery. Suktham et al. showed that resveratrol-loaded sericin nanoparticles robustly hindered growth of colorectal adenocarcinoma cells while cytotoxic to skin fibroblasts, suggesting the viability or potential of sericin nanoparticles as bionanocarriers in a drug delivery system.20 In addition, Tao et al. found silk sericin to be effective when blended with poly(vinyl alcohol) in a hydrogel with antibacterial properties as a drug delivery carrier with potential for use as wound dressing.21

Conclusion

Much more research is necessary, though, to explore how the antioxidant and moisturizing activities of the protein may be harnessed to confer skin-protective effects, especially against UV damage.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers,“The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. Lamboni L et al. Biotechnol Adv. 2015 Dec;33(8):1855-67.

2. Aramwit P et al. Biol Res. 2018 Nov 29;51(1):54.

3. Kumar JP, Mandal BB. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2019 Oct 9:18(10):2497-508.

4. Zhaorigetu S et al. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2003 Oct 15;71(1-3):11-7.

5. Dash R et al. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008 Apr;311(1-2):111-9.

6. Dash R et al. BMB Rep. 2008 Mar 31;41(3):236-41.

7. Berardesca E et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2015 Dec;37(6):606-12.

8. Aramwit P, Bang N. BMC Biotechnol. 2014 Dec 9;14:104.

9. Deenonpoe R et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019 Jul 10;19(1):168.

10. Aramwit P et al. BMC Nephrol. 2012 Sep 24;13:119.

11. Aramwit P et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013 Sep;305(7):585-94.

12. Aramwit P, Sangcakul A. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007 Oct;71(10):2473-7.

13. Qi C et al. Biomater Sci. 2018 Nov 1;6(11):2859-70.

14. Sapru S et al. Acta Biomater. 2018 Sep 15;78:137-50.

15. Napavichayanun S et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018 Dec;310(10):795-805.

16. Siritientong T et al. Pharm Res. 2014 Jan;31(1):104-16.

17. Lamboni L et al. Biotechnol Adv. 2015 Dec;33(8):1855-67.

18. Wang P et al. Carbohydr Polym. 2019 May 15;212:403-11.

19. Liang M et al. J Appl Biomater Funct Mater. 2018 Apr;16(2):97-106.

20. Suktham K et al. Int J Pharm. 2018 Feb 15;537(1-2):48-56.

21. Tao G et al. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019 Aug;101:341-51.

Inexpensively obtained as a silk industry by-product, sericin is a glycoprotein found to confer various biologic effects.1 The globular protein sericin has also long been known to exhibit antityrosinase and immunomodulatory activities.2,3 This column focuses on the wide range of emerging and potential applications of sericin in cutaneous treatments.

Protection against solar radiation and photoaging

Studies in mice to evaluate the potential antioxidant and skin-protective effects of sericin by Zhaorigetu et al. in 2003 revealed that, by diminishing oxidative stress, cyclooxygenase-2 protein, and cell proliferation, sericin exerted a photoprotective effect against acute harm and tumor promotion elicited by UVB.4

Using mouse skin models, Dash et al. showed in 2008 that the silk protein sericin derived from the tropical tasar silkworm is a robust antioxidant and photoprotective agent, displaying a capacity to block UVB-induced apoptosis in irradiated (30 mJ/cm2 UVB) human keratinocytes and, as compared with the mulberry silkworm, yielding protection against oxidative stress.5,6

In 2015, Berardesca et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, split-face study over 8 weeks in 40 women (ages 40-70 years) to assess the antiaging effects of topically applied combination therapy including gold silk sericin, niacinamide, and signaline. The investigators observed significant improvements in stratum corneum hydration, barrier function, skin elasticity, and roughness as compared with skin treated with the control formulation. They concluded that this combination formulation featuring gold silk sericin warrants attention in the arsenal for ameliorating signs of aging female facial skin.7

A year earlier, Aramwit and Bang introduced a bacterial nanocellulose gel shown to effectively release silk sericin for facial treatment. Formulated at a pH of 4.5, the bioactive mask exhibited an ultrafine and pure fiber network structure. The authors noted that the gel was less adhesive than the commercially available paper mask, while the silk sericin product displayed greater moisture absorption capacity. In vitro cytotoxicity assessments also revealed that the product is safe for facial treatments.8

Cosmeceutical antioxidant for hyperpigmentation