User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

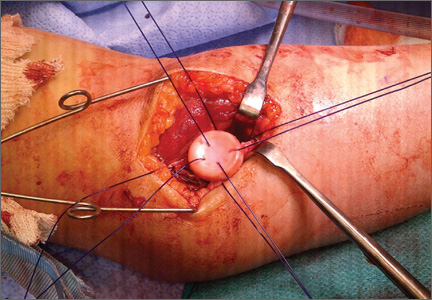

The Métaizeau Technique for Pediatric Radial Neck Fracture With Elbow Dislocation: Intraoperative Pitfalls and Associated Forearm Compartment Syndrome

Allograft Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Patients Younger Than 30 Years: A Matched-Pair Comparison of Bone– Patellar Tendon–Bone and Tibialis Anterior

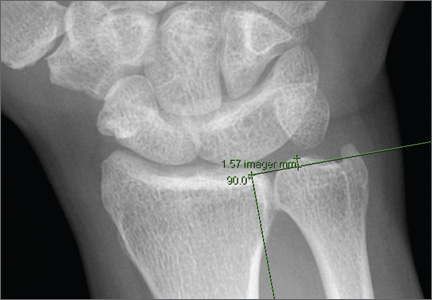

Compared With Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Radiographs Underestimate the Magnitude of Negative Ulnar Variance

Endoprosthetic Reconstruction After Resection of Musculoskeletal Tumors

Is It Safe to Place a Tibial Intramedullary Nail Through a Traumatic Knee Arthrotomy?

Use Online Coding Discussion Tools With Caution

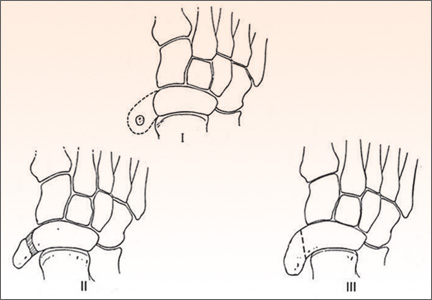

Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Accessory Navicular in Children and Adolescents

The Orthopedic Stepchild

Throughout antiquity, physicians and surgeons have concerned themselves with maladies of the foot and ankle. The literature is rife with articles describing management of clubfoot deformities and traumatic amputations of feet and legs. Authors have described tenotomies and manipulation for clubfeet as well as optimal techniques and levels for amputations to promote healing and functional outcomes. In progressive and aggressive surgical centers in Austria and Germany, techniques for correction of the deformities created by disease and trauma formed the basis for today’s reconstructive methodologies.

During my orthopedic residency in the 1960s, we managed pediatric versions of clubfoot, vertical talus, and neuromuscular conditions of the lower extremity (myelomeningocele, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy); adolescent bunions and pathologic flat feet; and, in adults, residual polio, arthritis, bunions, lesser toe deformities, ankle disorders, and trauma. Then along came the excitement of total joint arthroplasty, with its spectacular results, and the thrill in devoting careers to athletes and their myriad problems. Other interesting subspecialties emerged, and the orthopedic focus on a significant part of our heritage, the issues of foot and ankle, was lost for decades. Care for these problems was left to a small cadre of pediatric doctors, and soon-to-retire orthopedists who tended to view the field as

less demanding. Dynamic young practitioners showed little or no interest in caring for foot and ankle patients, and no progress was made in clinical care, research, and development of orthopedic technology and devices.

In the late 1960s, a small group of middle-aged and senior devotees of the specialty met in New York to form the American Orthopaedic Foot Society (AOFS), later to become the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS). The group’s goal was to renew interest in the foot and ankle specialty among orthopedic surgeons. As everyone knows, AOFAS has flourished and become one of the most progressive, innovative, and dynamic of all the orthopedic subspecialty

groups. In 1985, John Gartland, president of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, called together the leaders in the foot and ankle field to formulate a long-range plan to reclaim foot and ankle from the morass of substandard care

and to advance the subspecialty in every quarter. As AOFS (and later AOFAS) president, I was part of Gartland’s team. I recall we aimed to convince orthopedic chairs, the Residency Review Committee for Orthopaedic Surgery, and the Board

of Orthopaedic Surgery to increase training requirements, to develop foot and ankle educators, and to promote the area in training programs. Orthopedic educators developed fellowships (essentially nonexistent up until then) and organized and taught beginner and advanced continuing education courses at annual meetings and throughout the year.

There were other needs to be addressed. One was to educate nonorthopedic doctors to appreciate that foot and ankle problems had good nonoperative and surgical solutions, that there was an orthopedic subspecialty for these conditions, and that foot and ankle patients should be referred to its practitioners. Second, these patients’ public advocacy groups needed to know what knowledgeable orthopedists could provide and needed to be encouraged to seek care from these physicians rather than from less qualified providers and nonspecialists.

To an extraordinary degree, the goal of educating orthopedists has been achieved, and the field is now populated with young, energetic leaders, teachers, and practitioners. We have been less successful in educating potential referring physicians, the public, public advocacy groups, and third-party payers, including the US government. Progress has been made with private insurers and, as advisors, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and state government health committees.

Driven by emerging market opportunities, the orthopedic device industry has made unanticipated and enormous advances in the distal lower extremity realm. Small

companies have been founded, and larger companies have dedicated entire divisions to making fixation devices and prosthetic implants for every procedure involving the foot or the ankle. Biomedical engineers, metallurgists, orthopedic

consultant researchers, and well-funded projects have led the surge to develop the best foot and ankle technology. In addition, industry courses and scholarships for residents, fellows, teaching programs, and young physicians have been generating interest in these advances. Although it may be argued that entrepreneurship brings enormous bias, it must be conceded that interest in the foot and ankle field has increased tremendously. Outreach programs for foot and ankle care in the Third World have emerged as an additional humanitarian benefit of the expansion of the field.

From its strong start as a medical specialty to its fall into ignorance and neglect, the foot and ankle field, the unwanted stepchild of medicine and orthopedics, has made a dramatic recovery and has become a premier example of what medicine can achieve through focused effort. As leaders in orthopedic medicine in North America, we must also acknowledge the huge contributions made by a sterling array of international researchers, educators, and practitioners.

Some journals in the United States and other countries now concentrate solely on foot and ankle. Nevertheless, it is appropriate that The American Journal of Orthopedics and other general orthopedic surgery publications focus on foot and

ankle (and other specialties) in an annual issue. As each orthopedist tends mainly to his or her own area of interest, it is essential that we all stay current on the field as a whole. The basic science, innovations, and concepts of one specialty are often applicable to the entire field, and a casual notation of an idea from such a focused issue may have unimagined benefits for the readership and their patients. ◾

Throughout antiquity, physicians and surgeons have concerned themselves with maladies of the foot and ankle. The literature is rife with articles describing management of clubfoot deformities and traumatic amputations of feet and legs. Authors have described tenotomies and manipulation for clubfeet as well as optimal techniques and levels for amputations to promote healing and functional outcomes. In progressive and aggressive surgical centers in Austria and Germany, techniques for correction of the deformities created by disease and trauma formed the basis for today’s reconstructive methodologies.

During my orthopedic residency in the 1960s, we managed pediatric versions of clubfoot, vertical talus, and neuromuscular conditions of the lower extremity (myelomeningocele, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy); adolescent bunions and pathologic flat feet; and, in adults, residual polio, arthritis, bunions, lesser toe deformities, ankle disorders, and trauma. Then along came the excitement of total joint arthroplasty, with its spectacular results, and the thrill in devoting careers to athletes and their myriad problems. Other interesting subspecialties emerged, and the orthopedic focus on a significant part of our heritage, the issues of foot and ankle, was lost for decades. Care for these problems was left to a small cadre of pediatric doctors, and soon-to-retire orthopedists who tended to view the field as

less demanding. Dynamic young practitioners showed little or no interest in caring for foot and ankle patients, and no progress was made in clinical care, research, and development of orthopedic technology and devices.

In the late 1960s, a small group of middle-aged and senior devotees of the specialty met in New York to form the American Orthopaedic Foot Society (AOFS), later to become the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS). The group’s goal was to renew interest in the foot and ankle specialty among orthopedic surgeons. As everyone knows, AOFAS has flourished and become one of the most progressive, innovative, and dynamic of all the orthopedic subspecialty

groups. In 1985, John Gartland, president of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, called together the leaders in the foot and ankle field to formulate a long-range plan to reclaim foot and ankle from the morass of substandard care

and to advance the subspecialty in every quarter. As AOFS (and later AOFAS) president, I was part of Gartland’s team. I recall we aimed to convince orthopedic chairs, the Residency Review Committee for Orthopaedic Surgery, and the Board

of Orthopaedic Surgery to increase training requirements, to develop foot and ankle educators, and to promote the area in training programs. Orthopedic educators developed fellowships (essentially nonexistent up until then) and organized and taught beginner and advanced continuing education courses at annual meetings and throughout the year.

There were other needs to be addressed. One was to educate nonorthopedic doctors to appreciate that foot and ankle problems had good nonoperative and surgical solutions, that there was an orthopedic subspecialty for these conditions, and that foot and ankle patients should be referred to its practitioners. Second, these patients’ public advocacy groups needed to know what knowledgeable orthopedists could provide and needed to be encouraged to seek care from these physicians rather than from less qualified providers and nonspecialists.

To an extraordinary degree, the goal of educating orthopedists has been achieved, and the field is now populated with young, energetic leaders, teachers, and practitioners. We have been less successful in educating potential referring physicians, the public, public advocacy groups, and third-party payers, including the US government. Progress has been made with private insurers and, as advisors, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and state government health committees.

Driven by emerging market opportunities, the orthopedic device industry has made unanticipated and enormous advances in the distal lower extremity realm. Small

companies have been founded, and larger companies have dedicated entire divisions to making fixation devices and prosthetic implants for every procedure involving the foot or the ankle. Biomedical engineers, metallurgists, orthopedic

consultant researchers, and well-funded projects have led the surge to develop the best foot and ankle technology. In addition, industry courses and scholarships for residents, fellows, teaching programs, and young physicians have been generating interest in these advances. Although it may be argued that entrepreneurship brings enormous bias, it must be conceded that interest in the foot and ankle field has increased tremendously. Outreach programs for foot and ankle care in the Third World have emerged as an additional humanitarian benefit of the expansion of the field.

From its strong start as a medical specialty to its fall into ignorance and neglect, the foot and ankle field, the unwanted stepchild of medicine and orthopedics, has made a dramatic recovery and has become a premier example of what medicine can achieve through focused effort. As leaders in orthopedic medicine in North America, we must also acknowledge the huge contributions made by a sterling array of international researchers, educators, and practitioners.

Some journals in the United States and other countries now concentrate solely on foot and ankle. Nevertheless, it is appropriate that The American Journal of Orthopedics and other general orthopedic surgery publications focus on foot and

ankle (and other specialties) in an annual issue. As each orthopedist tends mainly to his or her own area of interest, it is essential that we all stay current on the field as a whole. The basic science, innovations, and concepts of one specialty are often applicable to the entire field, and a casual notation of an idea from such a focused issue may have unimagined benefits for the readership and their patients. ◾

Throughout antiquity, physicians and surgeons have concerned themselves with maladies of the foot and ankle. The literature is rife with articles describing management of clubfoot deformities and traumatic amputations of feet and legs. Authors have described tenotomies and manipulation for clubfeet as well as optimal techniques and levels for amputations to promote healing and functional outcomes. In progressive and aggressive surgical centers in Austria and Germany, techniques for correction of the deformities created by disease and trauma formed the basis for today’s reconstructive methodologies.

During my orthopedic residency in the 1960s, we managed pediatric versions of clubfoot, vertical talus, and neuromuscular conditions of the lower extremity (myelomeningocele, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy); adolescent bunions and pathologic flat feet; and, in adults, residual polio, arthritis, bunions, lesser toe deformities, ankle disorders, and trauma. Then along came the excitement of total joint arthroplasty, with its spectacular results, and the thrill in devoting careers to athletes and their myriad problems. Other interesting subspecialties emerged, and the orthopedic focus on a significant part of our heritage, the issues of foot and ankle, was lost for decades. Care for these problems was left to a small cadre of pediatric doctors, and soon-to-retire orthopedists who tended to view the field as

less demanding. Dynamic young practitioners showed little or no interest in caring for foot and ankle patients, and no progress was made in clinical care, research, and development of orthopedic technology and devices.

In the late 1960s, a small group of middle-aged and senior devotees of the specialty met in New York to form the American Orthopaedic Foot Society (AOFS), later to become the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS). The group’s goal was to renew interest in the foot and ankle specialty among orthopedic surgeons. As everyone knows, AOFAS has flourished and become one of the most progressive, innovative, and dynamic of all the orthopedic subspecialty

groups. In 1985, John Gartland, president of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, called together the leaders in the foot and ankle field to formulate a long-range plan to reclaim foot and ankle from the morass of substandard care

and to advance the subspecialty in every quarter. As AOFS (and later AOFAS) president, I was part of Gartland’s team. I recall we aimed to convince orthopedic chairs, the Residency Review Committee for Orthopaedic Surgery, and the Board

of Orthopaedic Surgery to increase training requirements, to develop foot and ankle educators, and to promote the area in training programs. Orthopedic educators developed fellowships (essentially nonexistent up until then) and organized and taught beginner and advanced continuing education courses at annual meetings and throughout the year.

There were other needs to be addressed. One was to educate nonorthopedic doctors to appreciate that foot and ankle problems had good nonoperative and surgical solutions, that there was an orthopedic subspecialty for these conditions, and that foot and ankle patients should be referred to its practitioners. Second, these patients’ public advocacy groups needed to know what knowledgeable orthopedists could provide and needed to be encouraged to seek care from these physicians rather than from less qualified providers and nonspecialists.

To an extraordinary degree, the goal of educating orthopedists has been achieved, and the field is now populated with young, energetic leaders, teachers, and practitioners. We have been less successful in educating potential referring physicians, the public, public advocacy groups, and third-party payers, including the US government. Progress has been made with private insurers and, as advisors, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and state government health committees.

Driven by emerging market opportunities, the orthopedic device industry has made unanticipated and enormous advances in the distal lower extremity realm. Small

companies have been founded, and larger companies have dedicated entire divisions to making fixation devices and prosthetic implants for every procedure involving the foot or the ankle. Biomedical engineers, metallurgists, orthopedic

consultant researchers, and well-funded projects have led the surge to develop the best foot and ankle technology. In addition, industry courses and scholarships for residents, fellows, teaching programs, and young physicians have been generating interest in these advances. Although it may be argued that entrepreneurship brings enormous bias, it must be conceded that interest in the foot and ankle field has increased tremendously. Outreach programs for foot and ankle care in the Third World have emerged as an additional humanitarian benefit of the expansion of the field.

From its strong start as a medical specialty to its fall into ignorance and neglect, the foot and ankle field, the unwanted stepchild of medicine and orthopedics, has made a dramatic recovery and has become a premier example of what medicine can achieve through focused effort. As leaders in orthopedic medicine in North America, we must also acknowledge the huge contributions made by a sterling array of international researchers, educators, and practitioners.

Some journals in the United States and other countries now concentrate solely on foot and ankle. Nevertheless, it is appropriate that The American Journal of Orthopedics and other general orthopedic surgery publications focus on foot and

ankle (and other specialties) in an annual issue. As each orthopedist tends mainly to his or her own area of interest, it is essential that we all stay current on the field as a whole. The basic science, innovations, and concepts of one specialty are often applicable to the entire field, and a casual notation of an idea from such a focused issue may have unimagined benefits for the readership and their patients. ◾

Discovery May Lead to New Drugs for Osteoporosis

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered what appears to be a potent stimulator of new bone growth. The finding could lead to new treatments for osteoporosis and other diseases that occur when the body doesn’t make enough bone.

“We have been looking for new ways to stimulate bone formation,” said principal investigator Fanxin Long, PhD. “The tools we already have are very good at slowing the breakdown of bone, but we need better ways to stimulate new bone growth.”

Studying mice, Dr. Long and colleagues focused on a pathway involved in bone formation. The so-called WNT proteins carry messages into cells and regulate embryonic and adult tissue in mammals, including humans. The WNT proteins enter cells from the outside and then can activate multiple pathways inside those cells.

Reporting in the January 30 issue of PLOS Genetics, Dr. Long and colleagues said that a specific member of the WNT family of proteins dramatically enhances bone formation, and it works through a mechanism that has not been well studied in bone before. It is called the mTOR pathway, and it interprets a cell’s surrounding environment, and nutritional and energy status.

“By analyzing that information, mTOR can determine whether a cell should go into a mode to make lots of stuff, like proteins or, in this case, new bone,” explained Dr. Long, a Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Washington University’s School of Medicine. “Bone formation is an energetically expensive process, so it makes sense that some regulator would tell a cell whether there is sufficient energy and material to manufacture new bone.”

Dr. Long and his colleagues studied mice that made either normal levels or an extra amount of WNT proteins. They found that a particular WNT protein, WNT7B, is a potent stimulator of bone formation in mice. Mice engineered to make additional WNT7B manufactured new bone at much higher rates than normal mice.

The researchers also found that the protein created more bone by greatly increasing the number of bone-manufacturing cells in the mice. Our bones are in a constant state of flux as the number of bone-making osteoblast cells fluctuates, while the number of bone-degrading osteoclast cells also adjusts.

The WNT7B protein had no effect on the total activity of osteoclasts but substantially increased the number of osteoblast cells. And it did so by stimulating the mTOR pathway.

“It’s still early, but our finding seems to point out that activating the mTOR pathway may be a good way to stimulate bone growth,” said Dr. Long, who is also a Professor of Medicine and of Developmental Biology. “This is a new twist because much of the current focus in mTOR-related drug development has been on compounds that inhibit the pathway to shut down cancer cells.”

Drugs that inhibit the mTOR pathway also are used to suppress the immune response in patients undergoing organ transplants.

“Many patients develop bone problems within a few months of receiving transplants because of the heavy doses of immunosuppressors they receive,” Dr. Long explained. “Scientists have not looked carefully at how drugs used to prevent organ rejection can have a detrimental effect on bone, but our study would suggest that if those drugs inhibit mTOR, they could disrupt bone formation.”

Next, Dr. Long plans to look more deeply at the mechanism through which the WNT proteins instruct bone cells to activate mTOR and stimulate bone growth. His goal is to learn what happens farther along in that pathway to create new bone. If more specific targets can be identified in the bone-formation process, drugs potentially could be developed to stimulate bone formation in people with osteoporosis without causing unwanted side effects.

Chen J, Tu X, Esen E, et al. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLOS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004145.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered what appears to be a potent stimulator of new bone growth. The finding could lead to new treatments for osteoporosis and other diseases that occur when the body doesn’t make enough bone.

“We have been looking for new ways to stimulate bone formation,” said principal investigator Fanxin Long, PhD. “The tools we already have are very good at slowing the breakdown of bone, but we need better ways to stimulate new bone growth.”

Studying mice, Dr. Long and colleagues focused on a pathway involved in bone formation. The so-called WNT proteins carry messages into cells and regulate embryonic and adult tissue in mammals, including humans. The WNT proteins enter cells from the outside and then can activate multiple pathways inside those cells.

Reporting in the January 30 issue of PLOS Genetics, Dr. Long and colleagues said that a specific member of the WNT family of proteins dramatically enhances bone formation, and it works through a mechanism that has not been well studied in bone before. It is called the mTOR pathway, and it interprets a cell’s surrounding environment, and nutritional and energy status.

“By analyzing that information, mTOR can determine whether a cell should go into a mode to make lots of stuff, like proteins or, in this case, new bone,” explained Dr. Long, a Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Washington University’s School of Medicine. “Bone formation is an energetically expensive process, so it makes sense that some regulator would tell a cell whether there is sufficient energy and material to manufacture new bone.”

Dr. Long and his colleagues studied mice that made either normal levels or an extra amount of WNT proteins. They found that a particular WNT protein, WNT7B, is a potent stimulator of bone formation in mice. Mice engineered to make additional WNT7B manufactured new bone at much higher rates than normal mice.

The researchers also found that the protein created more bone by greatly increasing the number of bone-manufacturing cells in the mice. Our bones are in a constant state of flux as the number of bone-making osteoblast cells fluctuates, while the number of bone-degrading osteoclast cells also adjusts.

The WNT7B protein had no effect on the total activity of osteoclasts but substantially increased the number of osteoblast cells. And it did so by stimulating the mTOR pathway.

“It’s still early, but our finding seems to point out that activating the mTOR pathway may be a good way to stimulate bone growth,” said Dr. Long, who is also a Professor of Medicine and of Developmental Biology. “This is a new twist because much of the current focus in mTOR-related drug development has been on compounds that inhibit the pathway to shut down cancer cells.”

Drugs that inhibit the mTOR pathway also are used to suppress the immune response in patients undergoing organ transplants.

“Many patients develop bone problems within a few months of receiving transplants because of the heavy doses of immunosuppressors they receive,” Dr. Long explained. “Scientists have not looked carefully at how drugs used to prevent organ rejection can have a detrimental effect on bone, but our study would suggest that if those drugs inhibit mTOR, they could disrupt bone formation.”

Next, Dr. Long plans to look more deeply at the mechanism through which the WNT proteins instruct bone cells to activate mTOR and stimulate bone growth. His goal is to learn what happens farther along in that pathway to create new bone. If more specific targets can be identified in the bone-formation process, drugs potentially could be developed to stimulate bone formation in people with osteoporosis without causing unwanted side effects.

Chen J, Tu X, Esen E, et al. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLOS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004145.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered what appears to be a potent stimulator of new bone growth. The finding could lead to new treatments for osteoporosis and other diseases that occur when the body doesn’t make enough bone.

“We have been looking for new ways to stimulate bone formation,” said principal investigator Fanxin Long, PhD. “The tools we already have are very good at slowing the breakdown of bone, but we need better ways to stimulate new bone growth.”

Studying mice, Dr. Long and colleagues focused on a pathway involved in bone formation. The so-called WNT proteins carry messages into cells and regulate embryonic and adult tissue in mammals, including humans. The WNT proteins enter cells from the outside and then can activate multiple pathways inside those cells.

Reporting in the January 30 issue of PLOS Genetics, Dr. Long and colleagues said that a specific member of the WNT family of proteins dramatically enhances bone formation, and it works through a mechanism that has not been well studied in bone before. It is called the mTOR pathway, and it interprets a cell’s surrounding environment, and nutritional and energy status.

“By analyzing that information, mTOR can determine whether a cell should go into a mode to make lots of stuff, like proteins or, in this case, new bone,” explained Dr. Long, a Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Washington University’s School of Medicine. “Bone formation is an energetically expensive process, so it makes sense that some regulator would tell a cell whether there is sufficient energy and material to manufacture new bone.”

Dr. Long and his colleagues studied mice that made either normal levels or an extra amount of WNT proteins. They found that a particular WNT protein, WNT7B, is a potent stimulator of bone formation in mice. Mice engineered to make additional WNT7B manufactured new bone at much higher rates than normal mice.

The researchers also found that the protein created more bone by greatly increasing the number of bone-manufacturing cells in the mice. Our bones are in a constant state of flux as the number of bone-making osteoblast cells fluctuates, while the number of bone-degrading osteoclast cells also adjusts.

The WNT7B protein had no effect on the total activity of osteoclasts but substantially increased the number of osteoblast cells. And it did so by stimulating the mTOR pathway.

“It’s still early, but our finding seems to point out that activating the mTOR pathway may be a good way to stimulate bone growth,” said Dr. Long, who is also a Professor of Medicine and of Developmental Biology. “This is a new twist because much of the current focus in mTOR-related drug development has been on compounds that inhibit the pathway to shut down cancer cells.”

Drugs that inhibit the mTOR pathway also are used to suppress the immune response in patients undergoing organ transplants.

“Many patients develop bone problems within a few months of receiving transplants because of the heavy doses of immunosuppressors they receive,” Dr. Long explained. “Scientists have not looked carefully at how drugs used to prevent organ rejection can have a detrimental effect on bone, but our study would suggest that if those drugs inhibit mTOR, they could disrupt bone formation.”

Next, Dr. Long plans to look more deeply at the mechanism through which the WNT proteins instruct bone cells to activate mTOR and stimulate bone growth. His goal is to learn what happens farther along in that pathway to create new bone. If more specific targets can be identified in the bone-formation process, drugs potentially could be developed to stimulate bone formation in people with osteoporosis without causing unwanted side effects.

Chen J, Tu X, Esen E, et al. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLOS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004145.

New Study Provides Guidance on Drug Holidays From Popular Osteoporosis Treatments

Doctors commonly recommend drug holidays from certain osteoporosis drugs because of the risks associated with these treatments. Yet little has been known about the ideal duration of the holidays and how best to manage patients during this time.

Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis have been shown to cause fractures in the thigh bones and tissue decay in the jawbone. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends a drug holiday from these treatments after 4 to 5 years of bone density stability if osteoporosis is moderate and after 10 years of stability if fracture risk is high.

However, new research from Loyola University researchers reveals that patients should resume treatment if they develop a fracture, have a decline in bone strength, or an early rise in signs indicative of increased fracture risk. The researchers also found that elderly patients and those with very low bone strength should be closely followed during a break from treatment. Their findings were published in the November/December 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 209 patients who started a drug holiday from bisphosphonates between 2005 and 2010. Eleven patients (5.2%) developed fractures and all patients had a significant increase in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase at 6 months. This level was more pronounced in patients who developed a fracture. While there was no significant change in the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, there was a statistically significant decline in the femoral neck bone mineral density.

“The results highlight groups who are at risk for fractures during drug holidays and recommendations on when to resume treatment,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, lead study investigator and Director of the Loyola University Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center. “These findings will help us continue to refine the current practice of drug holidays to better manage patients with osteoporosis.”

Chiha M, Myers LE, Ball CA, Sinacore JM, Camacno PM. Long-term follow-up of patients on drug holiday from bisphosphonates: real-world setting. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(6):989-994.

Doctors commonly recommend drug holidays from certain osteoporosis drugs because of the risks associated with these treatments. Yet little has been known about the ideal duration of the holidays and how best to manage patients during this time.

Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis have been shown to cause fractures in the thigh bones and tissue decay in the jawbone. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends a drug holiday from these treatments after 4 to 5 years of bone density stability if osteoporosis is moderate and after 10 years of stability if fracture risk is high.

However, new research from Loyola University researchers reveals that patients should resume treatment if they develop a fracture, have a decline in bone strength, or an early rise in signs indicative of increased fracture risk. The researchers also found that elderly patients and those with very low bone strength should be closely followed during a break from treatment. Their findings were published in the November/December 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 209 patients who started a drug holiday from bisphosphonates between 2005 and 2010. Eleven patients (5.2%) developed fractures and all patients had a significant increase in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase at 6 months. This level was more pronounced in patients who developed a fracture. While there was no significant change in the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, there was a statistically significant decline in the femoral neck bone mineral density.

“The results highlight groups who are at risk for fractures during drug holidays and recommendations on when to resume treatment,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, lead study investigator and Director of the Loyola University Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center. “These findings will help us continue to refine the current practice of drug holidays to better manage patients with osteoporosis.”

Chiha M, Myers LE, Ball CA, Sinacore JM, Camacno PM. Long-term follow-up of patients on drug holiday from bisphosphonates: real-world setting. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(6):989-994.

Doctors commonly recommend drug holidays from certain osteoporosis drugs because of the risks associated with these treatments. Yet little has been known about the ideal duration of the holidays and how best to manage patients during this time.

Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis have been shown to cause fractures in the thigh bones and tissue decay in the jawbone. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends a drug holiday from these treatments after 4 to 5 years of bone density stability if osteoporosis is moderate and after 10 years of stability if fracture risk is high.

However, new research from Loyola University researchers reveals that patients should resume treatment if they develop a fracture, have a decline in bone strength, or an early rise in signs indicative of increased fracture risk. The researchers also found that elderly patients and those with very low bone strength should be closely followed during a break from treatment. Their findings were published in the November/December 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 209 patients who started a drug holiday from bisphosphonates between 2005 and 2010. Eleven patients (5.2%) developed fractures and all patients had a significant increase in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase at 6 months. This level was more pronounced in patients who developed a fracture. While there was no significant change in the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, there was a statistically significant decline in the femoral neck bone mineral density.

“The results highlight groups who are at risk for fractures during drug holidays and recommendations on when to resume treatment,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, lead study investigator and Director of the Loyola University Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center. “These findings will help us continue to refine the current practice of drug holidays to better manage patients with osteoporosis.”

Chiha M, Myers LE, Ball CA, Sinacore JM, Camacno PM. Long-term follow-up of patients on drug holiday from bisphosphonates: real-world setting. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(6):989-994.